Abstract

Mosquitoes and sand flies are the most important vectors of several human diseases. A comprehensive analysis of the diversity and composition of the microbiome in mosquitoes and sandflies is important. It emphasises shared traits and distinctive differences between these vector species. Recent findings have demonstrated that physiological, environmental and ecological factors influence the diversity of these microbial communities. A deeper understanding of the functional roles of specific microbial taxa, such as their ability to modulate host immune responses or directly interact with pathogens, reveals exciting opportunities for innovative vector management strategies. These strategies could leverage microbiome manipulation to disrupt the transmission of disease-causing agents. However, despite notable advancements, critical gaps remain in unravelling the precise mechanisms by which these microbiome compositions influence vector competence. Ultimately, this understanding can be leveraged to harness the potential of microbiome-based interventions in reducing the burden of vector-borne diseases. This review explores the intricate relationships between microbial communities and key vectors, highlighting how these interactions influence the dynamics of pathogen transmission.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Gut microbiome, Vector competence, Mosquito, Sandflies, Diversity, Microbiome

Background

More than 700,000 people die from vector-borne diseases (VBDs) each year, which account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases worldwide [1]. Vectors such as mosquitoes, sand flies and ticks transmit infectious pathogens (viruses, parasites and bacteria) between humans or from animals to humans, causing vector-borne diseases. Many of these vectors are blood-sucking insects that ingest pathogens from an infected host during a blood meal and later transmit them to new hosts. These diseases are more prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas, where they disproportionately affect economically disadvantaged populations [2].

The most important arthropod vectors are mosquitoes, which transmit various diseases that affect millions of people worldwide. Anopheles, Aedes and Culex are the three main genera of vector mosquitoes that transmit different vector-borne diseases. About 249 million people worldwide are affected by malaria-causing parasites that are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes [3]. Aedes mosquitoes primarily transmit arboviruses, such as dengue virus (DENV), Rift Valley fever virus (RVF), Zika virus (ZIKV), chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and yellow fever virus (YFV), predominantly affecting urban and peri-urban populations [4, 5]. Culex mosquitoes transmit pathogens, including West Nile virus (WNV) and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), are involved in the transmission of lymphatic filariasis, a disease that leads to lifelong morbidity and disability [6]. Another important group of insect vectors is the phlebotomine sandflies, which transmit diseases such as leishmaniasis, bartonellosis, sandfly fever, summer meningitis, vesicular stomatitis and Chandipura virus encephalitis [7–10]. The increasing prevalence of VBDs can be attributed to factors such as insufficient healthcare infrastructure in endemic regions, parasite resistance to drug therapies, vector resistance to insecticides and failures in vector surveillance and control [11–16].

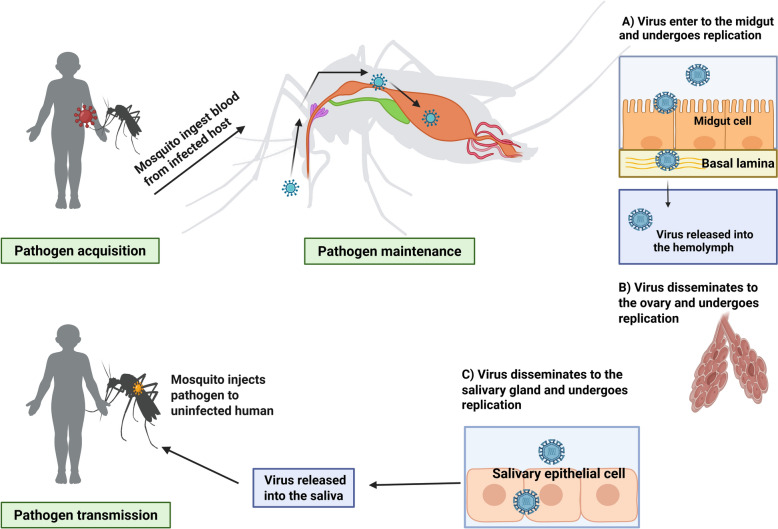

The microbiome is a community of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, protozoans and fungi, residing within and playing a significant role in shaping host biology, influencing processes such as nutrition, reproduction, metabolism, immunity and vector competence [17]. Vector competence refers to a vector’s ability to acquire, maintain and transmit a pathogen, such as a virus, bacterium or parasite, to hosts [18] (Fig. 1). By influencing pathogen survival and modulating immune responses, the microbiome plays a crucial role in determining and developing vector competence. It can either enhance or reduce a vector’s ability to transmit diseases [19]. This variation in vector competence arises through mechanisms such as immune response activation, competition for resources or the production of antiviral compounds [20]. For example, microorganisms can prime the immune system, enhancing the expression of immune-related genes and the production of antimicrobial peptides [21]. The microbiota also aids in nutrient absorption and energy production, thereby improving metabolic efficiency [22]. It also plays a role by competing with pathogens for resources and limiting their ability to establish infections [23]. Additionally, the microbiome can produce secondary metabolites responsible for inhibiting pathogen replication [21, 24]. Notably, Enterobacter ludwigii, Pseudomonas rhodesiae and Vagococcus salmoninarum isolated from Aedes albopictus have been shown to produce antiviral compounds capable of inhibiting La Crosse virus replication in vitro [25]. Furthermore, certain microbiota-derived molecules, such as prodigiosin, a red tripyrrole pigment synthesised by several bacterial species, including Serratia marcescens, have demonstrated inhibitory effects against Trypanosoma cruzi and Plasmodium species under in vitro conditions [26].

Fig. 1.

The replication, maintenance and transmission of infectious agents by the mosquito vector. Figure created with BioRender.com

The microbiome composition and acquisition in vector organisms are shaped by a combination of biotic and abiotic influences, including the genetic traits of both the host and the microbes, as well as environmental conditions [27–29]. Consequently, microbiome profiles can vary significantly between individuals, developmental stages, species and geographical regions [30, 31]. Climatic conditions directly influence the availability of microbes in the breeding habitats of insect vectors. A change in climatic conditions, such as temperature and humidity, may influence microbial diversity in the environment. Therefore, vector populations growing in different geographical areas may acquire variable compositions of microbiomes [30, 32, 33]. For example, a study conducted in China revealed significant variation in gut microbiota across eight regions in various mosquito species, including Ae. albopictus, Aedes galloisi, Culex pallidothorax, Culex pipiens, Culex gelidus and Armigeres subalbatus [34]. Similar regional differences were observed in the microbiomes of Culex tritaeniorhynchus and Culex orientalis in the Republic of Korea [35]. In another study, global variations in the microbiomes of Ae. albopictus and Aedes japonicus were reported in eight countries, including Europe, the USA and Japan [36]. Likewise, the composition of sand fly microbiomes was associated with different geographical regions in Iran and Tunisia [37, 38]. These variations likely contribute to phenotypic differences between the vector hosts [39].

Microbes located in critical tissues, such as the midgut or salivary glands, may directly interact with pathogens, influencing their survival, replication or transmission. Meanwhile, microbes in other tissues may exert indirect effects on the vector’s ability to transmit diseases (Tables 1, 2). It has been demonstrated that the insect midgut microbiome can influence susceptibility to dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) by inhibiting prohibitin on the midgut surface of mosquitoes [40]. Bacterial species such as Asaia spp., S. marcescens, Chromobacterium sp. Panama (Csp_P) and Enterobacter spp. in the mosquito midgut are associated with enhancing the immunity of vectors [41–43]. A reduced microbiome enhances Plasmodium oocysts in various anopheline mosquitoes [21, 44]. In sand flies, midgut bacteria have also been found to provide essential nutrients that facilitate Leishmania attachment to the gut wall [45]. Furthermore, microbes in the salivary gland can either inhibit or promote the colonisation of pathogens within these glands [46, 47].

Table 1.

Microbiome diversity in different tissues of mosquitoes

| Tissue (mosquitoes) | Microbiomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Midgut | Enhydrobacter, Aeromonas, Serratia, Ralstonia, Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Rubrobacter, Anaerococcus, Methylobacterium, Turicibacter, Elizabethkingia, Corynebacterium, Stenotrophomonas, Rhizobium, Sphingobacterium, Wolbachia, Chryseobacterium, Pectobacterium, Asaia, Gluconobacter, Staphylococcus, Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Proteus, Acinetobacter, Saccharomyces, Enterococcus, Kytococcus, Lactococcus, Kocuria, Alloiococcus, Sphingomonas, Acidovorax, Aquabacterium, Bosea, Flectobacillus, Hydrogenophaga, Isosphaera, Roseomonas, Sphingopyxis, Zoogloea, Delftia | [46, 50, 51, 57–65] |

| Salivary gland | Enhydrobacter, Aeromonas, Serratia, Ralstonia, Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Rubrobacter, Anaerococcus, Methylobacterium, Turicibacter, Elizabethkingia, Nitrospira, Corynebacterium, Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, Bacillus, Massilia, Delftia, Shigella, Cutibacterium, Atopococcus, Stenotrophomonas, Rhizobium, Sphingobacterium, Wolbachia, Chryseobacterium, Pectobacterium, Aeromonas, Enterobacter, Paracoccus, Enterococcus, Pantoea, Lysinibacillus, Brevibacterium, Klebsiella, Saccharomyces, Kocuria, Lactococcus, Escherichia, Burkholderia, Asaia, Sphingomonas, Cupriavidus | [46, 50, 51, 57, 58, 66] |

| Malpighian tubules |

Pseudomonas Wolbachia |

[67] [20] |

| Reproductive organs | Ochrobactrum, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Acinetobacter, Elizabethkingia, Asaia, Wolbachia, Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Geobacillus, Micrococcus, Kocuria, Streptococcus, Stenotrophomonas, Aerococcus, Serratia, Klebsiella, Pantoea, Microbacterium, Phytobacter, Spiroplasma | [50, 52, 53, 55, 68, 69] |

Table 2.

Microbiome diversity in different tissues of sand flies

| Tissue sand fly | Microbiomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gut | Enterobacter, Aeromonas, Erwinia, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Propionibacterium, Trabulsiella, Wolbachia, Asaia, Serratia, Stenotrophomonas, Enhydrobacter, Chryseobacterium, Edwardsiella, Microbacterium, Staphylococcus, Escherichia, Proteus, Klebsiella, Kluyvera, Leminorella, Pantoea, Providencia, Rahnella, Shigella, Tatumella, Yersinia, Kocuria, Streptococcus, Methylobacterium, Bacillus, Ochrobactrum, Cutibacterium, Spiroplasma, Propionibacterium, Diplorickettsia, Rickettsia, Rickettsiella | [37, 185, 190, 196, 198–204] |

| Salivary gland | Enterobacter, Spiroplasma, Ralstonia, Acinetobacter, Reyranella, Undibacterium, Bryobacter, Corynebacterium, Cutibacterium, Psychrobacter, Wolbachia | [200] |

| Ovary | Bradyrhizobium, Pseudomonas, Ochrobactrum | [197] |

Currently, controlling vectors is the main strategy for managing vector-borne diseases (VBDs). Understanding the complex relationships between insect vectors and their associated microorganisms is an important first step toward developing innovative approaches to reduce pathogen transmission and improve VBD control. This review focuses on how the microbiome affects vector biology and competence. It also explores new applications of microbiome research in creating effective strategies to combat VBDs.

Mosquito and microbiome: a complex interaction

The microbiome of mosquitoes exhibits significant variation across different tissues, including the midgut [48, 49], salivary glands [50–52], reproductive tracts [53–55] and cuticle surfaces [56]. This tissue-specific variation or tissue tropism reflects the distinct microenvironments and functional roles of each anatomical site within the mosquito host.

The gut microbiome

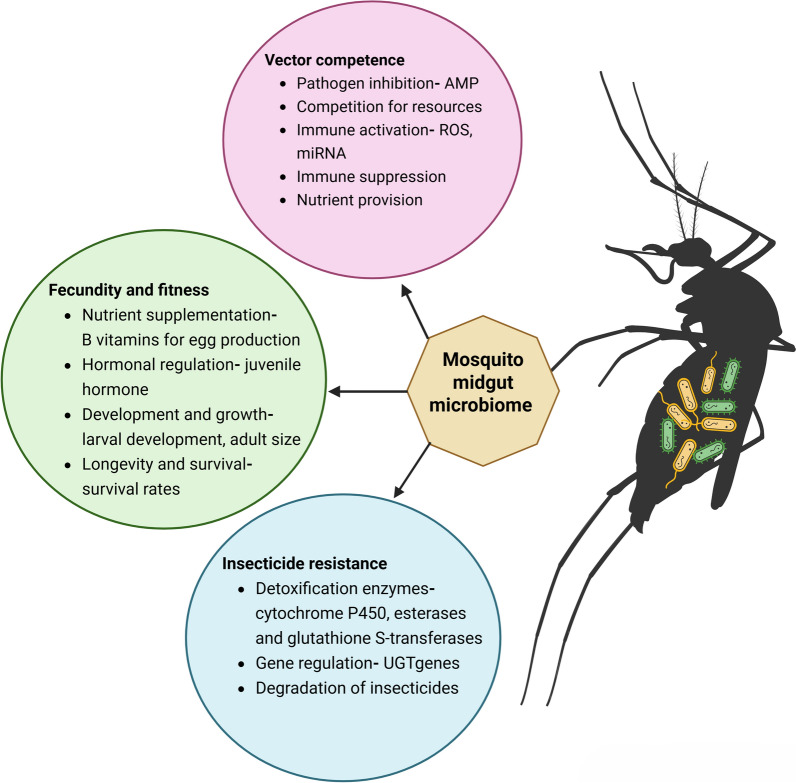

The gut microbiota, also known as the gut microbiome, includes bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses and parasites that reside in the digestive tracts of animals. These microorganisms play a crucial role in various functions, such as digesting food, producing vitamins, regulating the immune system, nutrient absorption, regulating water balance, expelling waste and behavioural modulation [70–73]. The roles of microbiomes in insect physiological processes have been studied. For example, microbes such as Elizabethkingia anophelis, Enterobacter spp. and Serratia spp. are involved in blood meal digestion [74, 75]. Other microbes, such as Wolbachia spp., S. marcescens, Chromobacterium sp. and Asaia spp. are involved in the immune system regulation [21, 76–79]. Escherichia coli in the mid-gut microbiome is known to be involved in riboflavin (vitamin B2) synthesis, facilitating energy metabolism, oxidative stress response, blood digestion and egg production in mosquitoes (Fig. 2) [80]. The presence of microbial communities within the digestive tracts of mosquitoes has been recognised for many years [81]. According to research conducted in the early 1900s, mosquitoes’ digestive tracts contain a community of extracellular microorganisms that form the gut microbiota in both larval and adult stages [82]. However, detailed investigations into the composition and functionality of these microbiota have emerged mainly over the past decade [83]. The diverse microbiome of mosquitoes may vary between species and developmental stages. Various breeding sites may have different compositions of microbes, which are acquired during the larval stage. However, adult mosquitoes can acquire different microbial communities through nectar, blood meals or by imbibing water from their breeding sites when they emerge [84–87]. For example, variations in microbiomes in different developmental stages have been seen in Anopheles gambiae, Ae. albopictus and Cx. pipiens [83, 84, 88].

Fig. 2.

The various roles of midgut microbiota in mosquito biology. Figure created with BioRender.com

The role of mosquito gut microbiota

In mosquitoes, functional investigations have mostly examined how gut microbiota affects vector competence. Additionally, research has provided valuable insights into nutrient acquisition, development, insecticide resistance and oviposition behaviour.

Mosquito fitness, oviposition and hatchability

The microbiome is essential for mosquito development and significantly influences host immune signalling pathways and lifespan. For example, the presence of bacteria such as E. coli in mosquito larvae appears to play a critical role in larval development into adulthood. These microorganisms may induce hypoxia within the larval gut by scavenging oxygen in the gut lumen, creating anoxic conditions. Research suggests that these anoxic conditions serve as developmental cues, facilitating the transition of larvae to the pupal stage [89]. Early research on mosquito larvae showed that increased mortality and delayed growth resulted from a decrease in microbial diversity of microorganisms in the aquatic environment [81, 90]. A study by Coon et al. [84] utilized surface sterilization techniques on mosquito eggs to generate axenic larvae of Ae. aegypti, Aedes atropalpus and An. gambiae; they were verified to be free of gut microbiota through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture-based methods. Interestingly, when given a diet that was sufficiently nutritious and germ-free, larvae of every species failed to moult and died at the first instar stage. However, axenic larvae’s growth into adulthood was fully restored when they were colonised by different individual members of the gut community or given normal gut microbiota [84]. Riboflavin, a vitamin B2, is produced naturally by microbiota in the midguts of mosquitoes. It is important for the development of larvae and adults. Recent research has shown that riboflavin mediates this association since axenic larvae can mature into adults when reared in environments that maintain this vitamin and have an anoxic midgut [91] (Fig. 2). These studies collectively highlight gut microbiota’s critical role in mosquito development.

The presence of bacteria also appears to influence egg hatching. Studies have shown that Aedes aegypti eggs with higher concentrations of bacteria (e.g., Enterobacter cloacae and Bacillus species) on their surfaces hatch more rapidly than those with lower bacterial loads [92]. Furthermore, experiments comparing bacterial-rich and germ-free environments reveal significant differences in egg-hatching rates [93]. This phenomenon may be attributed to bacterial production of signalling molecules such as carboxylic acids and methyl ester metabolites, which not only promote egg hatching but also act as oviposition attractants for Ae. aegypti [94]. Additionally, bacterial metabolic byproducts in the aquatic environment may create conditions that are conducive to egg hatching, thereby further enhancing reproductive success. According to the study, ovipositing females preferred rearing water from larvae infected with Ascogregarina taiwanensis or Candida near pseudoglaebosa rather than distilled water or rearing water from uninfected larvae [95].

Acquisition and digestion of food

Mosquitoes primarily obtain nutrients from plant nectar and blood meals. While males feed exclusively on nectar, females consume tryptophan in the nectar for energy and blood to support egg development [96, 97]. As holometabolous insects, mosquitoes undergo complete metamorphosis, with distinct larval and adult life stages separated by pupation [98]. During their aquatic larval stages, mosquitoes generally feed as detritivores before pupating. Adult gut microbiota consists of bacteria that were transferred from the larval stage and obtained through mating, sugar-eating and water consumption [99, 100]. The gut microbiota plays a vital role in larval development, with living bacteria activating signalling pathways involved in nutrient sensing. The gut microbiota in Ae. aegypti larvae promote development by providing essential nutrients such as riboflavin and inducing hypoxia-related signalling pathways, crucial for moulting and growth [80]. A study by Coon et al.[89] identified that bacterial respiration reduces gut oxygen levels, triggering hypoxia-inducible pathways that drive moulting and growth in mosquito larvae. The gut microbial diversity and composition can be influenced by the vector’s host-feeding preferences, which may affect the vector’s ability to acquire and transmit pathogens [101]. Antibiotic treatments using carbenicillin and tetracycline have been shown to significantly reduce the number of culturable gut bacteria in adult female Ae. aegypti. This reduction results in a statistically significant decrease in the ability to lay eggs and slight delays in the digestion of blood meals [74]. Gut microbes are also important in autogenous mosquitoes for nutrient acquisition, which can produce eggs without blood-feeding [85]. For instance, Enterobacteriaceae, a prominent bacterial family in Ae. albopictus metabolises fructose, a key sugar in nectar, to generate nutrients beneficial to the host [102].

These findings highlight the crucial role of gut microbiota in both digestion and reproductive processes in mosquitoes, suggesting potential avenues for further research into mosquito physiology and vector control strategies.

Insecticide resistance

The term ‘insecticide resistance’ refers to an insect’s ability to tolerate exposure to insecticides. Several biological mechanisms can lead to insecticide resistance, including metabolic, target-site and behavioural resistance [103]. Metabolic resistance involves the increased detoxification of the insecticide through increased production of metabolic enzymes in insects such as esterases, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) [104]. Previous research on insecticide resistance in mosquitoes has mostly concentrated on their genes. The connection between mosquitoes’ symbiotic bacteria and their insecticide resistance has garnered more attention in recent years. Gut microbes play a significant role in influencing insecticide resistance in mosquitoes by modulating the detoxification and metabolism of chemical compounds [105, 106]. These microorganisms can also produce enzymes such as esterases (GSTs) and cytochrome P450s, which are known to degrade or modify insecticides, thereby reducing their toxicity (Fig. 2) [107]

In Cx. pipiens pallens strains resistant to deltamethrin, Wolbachia was found to be more prevalent, indicating its role in enhancing resistance to this insecticide [108]. Likewise, Klebsiella pneumoniae enrichment was found by metagenomic sequencing of Anopheles albimanus strains resistant to fenitrothion [56, 109, 110]. Other microbes, including Bacillus cereus [111], Acidomonas sp. [112], Staphylococcus aureus [113], Pseudomonas fluorescens, E. cloacae [114] and Aspergillus niger [115] also exhibit high potential for breaking down deltamethrin. Additional research suggests that the use of fenitrothion significantly boosts Pseudomonas and Flavobacterium abundance [116, 117]. By breaking down fenitrothion into 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol, a substance with no insecticidal properties, these bacteria may further convert it into a carbon source and utilise it for development [118] (Fig. 3). According to Zhang et al., Pseudomonas is involved in the metabolism of pyrethroids and organophosphates [119]. The symbiotic bacteria can promote resistance to organophosphate insecticides by increasing the metabolic activity of An. stephensi in response to chemicals [120]. Interestingly, several bacterial species in the mosquito gut can directly metabolise insecticides, converting them into less harmful compounds, which are then further metabolised and excreted. These findings reveal a distinct correlation between midgut microbiota and insecticide resistance in mosquitoes, with potential implications for their vector competence.

Fig. 3.

This image illustrates how the microbiome detoxifies the insecticide and further metabolises it

Impact of microbiome in modulating vector competence

The term ‘vector competence’ describes a vector’s innate ability to acquire, maintain and transmit a pathogen, comprising several barriers and complex processes within the vector [121]. When mosquitoes feed on blood, they can ingest pathogens from host vertebrates. Components of the mosquito immune system are crucial for defence against arboviruses and Plasmodium parasites. The peritrophic matrix and midgut epithelium are two significant barriers that prevent the entry of different pathogenic microbes [122]. The microbial community associated with mosquito larvae has a significant effect on the adult mosquitoes immunological responses and vector competence. This can either enhance or inhibit their ability to transmit diseases.

Microbiota and arboviruses

Microbiota-arbovirus interactions appear to be a key factor in establishing arboviral infection and transmission [25, 123]. For example, when the An. gambiae microbiota was eliminated through antibiotic treatment, and the mosquitoes were less susceptible to O’nyong’nyong virus (ONNV) viral infection [124]. Conversely, Ae. aegypti became more susceptible to DENV infection when exposed to the mosquito-associated fungus Talaromyces sp. which suppresses the expression of digestive enzymes and trypsin activity in the mosquito gut [125]. Additionally, differences in microbiome composition have been noted between DENV-susceptible and DENV-resistant Ae. aegypti populations, including variations in bacterial genera such as Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas, with certain taxa potentially influencing susceptibility [126, 127].

In Culex mosquitoes, infection with WNV has been linked to an increase in bacterial diversity [128]. Similarly, CHIKV infection in Ae. albopictus reduces Wolbachia abundance and increases Enterobacteriaceae abundance. Instead, ZIKV infection changes the microbiome composition in Ae. aegypti [129, 130].

The study on Aedes mosquitoes demonstrated that higher titres of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) were seen after treating Ae. aegypti with antibiotics. It has been demonstrated that anti-microbial peptide (AMP) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) expression are decreased when gut bacteria are absent (Fig. 2) [78, 131]. For instance, Aedes mosquito larvae exposed to E. coli at sub-lethal levels produce important immune components such as nitric oxide and AMP, which improve defence against subsequent infections [132]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that infection with certain strains of Wolbachia can disrupt DENV and ZIKV infections in Ae. aegypti [133]. Enterobacter hormaechei B17 secretes sphingosine, a metabolite that blocks the virus and efficiently reduces ZIKV infection in cell cultures and Ae. aegypti [42]. Csp_P is a notable bacterium that has been shown to decrease DENV infection in Ae. aegypti by generating an amino-peptidase that breaks down the DENV envelope protein (Fig. 4) [41, 78]. Moreover, Csp_P produces the anti-parasitic protein rhomidepsin, which inhibits Plasmodium falciparum infection in An. gambiae [122].

Fig. 4.

The three primary ways of the microbiota influencing arboviruses. Figure created with BioRender.com

However, several gut bacteria make mosquitoes more susceptible to arboviruses. For instance, Serratia odorifera, which is present in mosquitoes’ guts, makes Ae. aegypti more susceptible to DENV or CHIKV infection [40, 134]. This effect is mediated by the bacterial polypeptide P40, which interacts with the protein prohibitin, a factor related to arboviral infection in mosquito cells [40, 135]. Similarly, by generating a protein known as SmEnhancin, which breaks down the mucin layer of the mosquito midgut epithelium and increases susceptibility to infection, a strain of S. marcescens increases DENV infection in Ae. aegypti [136, 137]. This protein plays a critical role in the interaction between the mosquito vector and the host it bites. It aids in modulating the host’s immune response, creating an environment conducive to pathogen survival and transmission [137]. By suppressing certain immune pathways in the host, SmEnhancin facilitates the establishment and replication of DENV within the host after a mosquito bite [137].

Mosquitoes with higher levels of SmEnhancin expression may exhibit an enhanced ability to transmit pathogens, as they are more effective at suppressing host defences. Conversely, variations in SmEnhancin production, whether due to genetic differences or environmental factors, could influence the mosquito’s efficiency as a vector [137].

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact molecular structure and pathways involved in SmEnhancin activity. Understanding how environmental and ecological factors influence SmEnhancin expression in mosquito populations could also provide insights into the varying transmission dynamics of mosquito-borne diseases across regions. These findings highlight the complex relationships between mosquito microbiota and arboviruses, revealing both protective and enhancing roles of microbial species in viral infection and transmission.

Insect-specific viruses (ISVs)

Insect-specific viruses (ISVs) are non-pathogenic to vertebrates due to their inability to replicate in mammalian cells; however, these viruses can suppress the replication of arboviruses in mosquitoes/sandflies [138–140]. These viruses share many similarities with established arboviruses and can be transmitted vertically [141]. They are classified within major viral families such as Flaviviridae, Bunyaviridae, Negeviruses, Togaviridae, Reoviridae, Mesoniviridae and Rhabdoviridae [142, 143]. Experimental studies have shown that the replication of DENV and ZIKV can be suppressed in both Ae. aegypti and C6/36 mosquito cell lines when co-infected with an ISV known as the cell-fusing agent virus (CFAV) [144]. Likewise, the Nhumirim virus (NHUV) can reduce the replication of WNV, JEV and Saint Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) in insect cell lines [145]. Furthermore, when mosquitoes were experimentally co-infected with NHUV and WNV, the dissemination rate of WNV was significantly reduced [146]. Prior infection with Eilat virus (EILV) reduces the virus titres of CHIKV, western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) in C7/10 cells [142, 147]. The difference in the relative abundance of ISV families in field-caught Ae. aegypti was between the DENV-infected and non-infected mosquitoes. Additionally, Phasi charoen-like phasivirus (PCLV) was observed frequently in DENV-infected mosquitoes [148].

Microbiota and plasmodium

Protozoa of the genus Plasmodium cause malaria. In total, four species are known to cause disease mainly in humans: P. falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae. Other Plasmodium species, such as Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium simium, primarily infect reptiles, birds and other mammals but can also infect humans. For example, human cases of P. knowlesi malaria have been reported in Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Myanmar and several other Southeast Asian countries [149]. Additionally, a human case of P. simium infection has been reported in Brazil [150]. The Plasmodium species is greatly influenced by the presence of a microbiome in the midgut. Studies have shown that reducing midgut bacterial populations through antibiotic treatment leads to an increased burden of oocysts and a higher prevalence of various human and rodent malaria parasites across different Anopheles species, the primary vectors of malaria [44, 151–154].

Recent research indicates that bacteria play a vital role in triggering a ‘priming’ immune response to Plasmodium in An. gambiae. For instance, during parasite invasion, bacteria-driven activation of a haemocyte differentiation factor promotes the transformation of haemocytes into granulocytes, as observed by Rodrigues et al. [155]. This increase in granulocytic haemocytes strengthens the mosquito’s defence against subsequent infections by Plasmodium or other pathogenic agents. The reintroduction of Gram-negative bacteria into mosquitoes has been found to reduce the intensity of Plasmodium infections in a dose-dependent manner [152, 156]. Bacteria commonly colonising Anopheles mosquitoes, such as Comamonas sp., Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Pantoea, Serratia, Enterobacter and Elizabethkingia, exhibit mosquito-independent inhibition of Plasmodium [21, 43, 78]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that infection with certain strains of Wolbachia can disrupt Plasmodium infections in An. stephensi [157]. Antibiotic elimination of the microbiota led to increased levels of tryptophan and its metabolites, including 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK), which damaged the peritrophic matrix and promoted Plasmodium berghei infection [158].

Several bacterial species also produce protective factors that act against various stages of the parasite’s lifecycle. Using bacteria-free culture supernatants, such as Csp_P and Serratia, has shown the ability to block Plasmodium asexual and sporogonic stages. These inhibitory effects are likely mediated by antimicrobial compounds or enzymes secreted by the bacteria, which directly interfere with parasite development.

Therefore, midgut bacteria play a critical role in modulating mosquito vector competence for malaria parasites. They may achieve this through immune signalling pathways or direct interactions with the parasites, thereby limiting the mosquito’s ability to transmit malaria.

Salivary gland microbiome

Salivary glands have an equally important function in the replication and transmission of pathogens as the midgut [159]. The salivary viral titre is an ideal indicator of vector competence [160]. However, sufficient viral replication within the salivary glands is essential before the virus can be transmitted through saliva to a new host [161]. Even salivary glands are an important dissemination site where arboviruses can replicate; they must cross the salivary gland infection and escape barriers for successful release into the saliva for further transmission [162]. Salivary gland microbiomes in insects can significantly influence their behaviour by interacting with the host’s physiology and neural pathways. Insects often rely on their microbiomes for essential functions such as digestion, immunity and even reproduction; however, emerging research shows that microorganisms in the salivary glands also affect behaviour. These microbiomes can influence insect feeding preferences, social behaviours and even their ability to transmit pathogens [22, 163]. Understanding these relationships is crucial, as it not only provides insight into insect physiology but also offers potential strategies for insect vector control or disease prevention.

The diversity of the microbiome in the salivary gland

The diverse range of microbiota that make up a mosquito’s salivary gland microbiome is crucial for both the mosquito’s function and its ability to transmit disease [51]. This microbiome can influence vector competence by interacting with pathogens, affecting their survival, replication and transmission [164]. The composition of the salivary gland microbiome varies among mosquito species, but commonly identified genera include Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and Serratia [165]. For instance, Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas are predominant in the salivary glands of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, which are key vectors for diseases such as dengue, Zika and chikungunya [46]. In Anopheles mosquitoes, bacteria such as S. marcescens have been shown to modulate the mosquito’s ability to transmit Plasmodium parasites [47]. Moreover, field studies on Anopheles darlingi indicate significant differences in the salivary gland microbiota between lab-reared and wild populations, with genera such as Wolbachia and Asaia playing a role in modulating mosquito–pathogen interactions [57].

The salivary gland microbiome is also implicated in physiological processes such as saliva production, which is vital for blood feeding and pathogen transmission. Mosquito saliva facilitates the replication and dissemination of viruses within vertebrate hosts. Recent research highlights that the saliva of anopheline mosquitoes harbours bacteria that are introduced into mammalian hosts during blood feeding. Surprisingly, a study has shown that P. berghei and certain bacteria can successfully colonize the tissues of mammalian hosts through mosquito saliva [47]. This dual colonization highlights the complexity of host, pathogen and microbiome interactions, which can potentially influence disease outcomes and shape pathogen evolution within vertebrate hosts.

Ovary microbiome

The ovaries are critical sites for virus replication, facilitating the vertical transmission of pathogens from the mother to oocytes [166]. Similarly, bacteria present in the ovaries can be transmitted vertically from one generation to the next [167]. The ovary microbiome in vector mosquitoes plays a vital role in their reproductive success, vector competence and overall physiology. The extracellular bacterium Asaia can vertically spread after colonising the Anopheles mosquito ovaries [168, 169]. Wolbachia, an intracellular bacterium, not only infects somatic tissues but also invades the germ cells in the ovaries reliably, enabling vertical transmission [167, 170, 171]. Serratia AS1, another extracellular bacterium, also persistently colonises Anopheles ovaries and is passed from females to their offspring. Notably, Serratia AS1 is also found in the accessory glands of male Anopheles mosquitoes, enabling its transmission through mating [68]. Although research on microbial sexual transmission in mosquitoes is limited, bacteria such as Asaia and Serratia have been identified in the reproductive organs of both Anopheles and other mosquito species, suggesting their potential role in venereal transmission during copulation [68, 172].

Research indicates that mosquito species such as Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus harbour distinct bacterial communities in their ovaries, which differ significantly from their gut microbiota [53]. Studies show that the ovary microbiota includes genera such as Serratia, Klebsiella, Wolbachia and Asaia, with species-specific variations. For instance, Wolbachia is prominent in Ae. albopictus but less so in Ae. aegypti, where Serratia and Enterobacter are more common [173–175]. These microbes are acquired from the environment and then selectively partitioned among different tissues, including ovaries, where they may influence mosquito fertility and the transmission of pathogens such as DENV and ZIKV [176].

Understanding the bacterial composition of mosquito ovaries is crucial for elucidating the role of these microbes in host–pathogen interactions. This knowledge can reveal whether ovary-associated bacteria influence susceptibility or vector capacity through mechanisms such as immune modulation, the production of bioactive molecules or the establishment of reproductive isolation, particularly by endosymbionts such as Wolbachia [177, 178].

Sand fly and microbiome

Sand flies are tiny insects that belong to the family Psychodidae [8]. They act as vectors for several diseases, most notably leishmaniasis, which is caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania [179]. Sand flies thrive in warm, humid environments and are mainly active during the evening and night-time [180]. Once the parasites enter the host, they invade and multiply within host cells, leading to different clinical manifestations, resulting in mucocutaneous, visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis [181].

In addition to leishmaniasis, sandflies can transmit other pathogens, including viruses (phleboviruses) and bacteria (Bartonella), causing sandfly fever and bartonellosis, respectively. The microbiomes of sand flies, particularly those in their gut, play a crucial role in influencing their vector competence [182]. Gut microbial communities can modulate the development of parasites such as Leishmania, either enhancing or inhibiting their growth, thereby affecting the sand fly’s ability to transmit pathogens [183, 184] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Overview of sand fly microbial community and pathogen association. Figure created with BioRender.com

The composition and diversity of the microbiome in sand flies

Similar to in other Diptera, the microbiota of the sand fly is a dynamic community that primarily originates from its environment. Its composition changes as it progresses through various developmental stages, profoundly influenced by the environments and food sources it encounters [185–187]. Sand fly eggs are typically laid in environments such as soil, animal burrows and decaying wood [188, 189], which are known for their rich microbial diversity. This highlights the significant relationship between the microbial communities present in the guts of sand flies and their natural breeding habitats [190].

Few studies have reported that genera such as Enterobacter and Acinetobacter are present in both the adult and larval stages of Pintomyia evansi, indicating that flies may acquire microbes from their surroundings through feeding or that certain bacteria can persist transstadially, being passed from larvae to adults [191, 192]. For obvious reasons, wild-caught sand flies exhibit greater gut bacterial diversity compared with their lab-reared counterparts, likely due to the restricted diet in laboratory settings [193, 194]. Based on a meta-analysis, the majority of bacteria found in Old World sand fly species are members of the phyla Proteobacteria and Firmicutes [192]. Additionally, bacteria of the Actinobacteria phylum were also reported. In Lutzomyia sp., bacteria belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria were abundant, followed by Firmicutes and Actinobacteria [192]. Methylobacterium, a dominant inhabitant of plant phyllospheres, is consistently present in the midgut of Pi. evansi, suggesting a plant-based diet. The presence of Methylobacterium in Pi. evansi was more prominent in engorged females, indicating potential interactions between plant-derived microbes, blood nutrients and the parasites transmitted during blood feeding [195]. Hassan et al. previously identified a diverse microbiome community within the midgut of Phlebotomus papatasi. This community includes bacteria such as Shigella sonnei, Alcaligenes faecalis, Serratia liquefaciens, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Bacillus thuringiensis and Listeria seeligeri [186]. The bacterium Ochrobactrum sp. was found in the midguts of P. duboscqi, a known vector of L. major in sub-Saharan Africa [185]. The composition and diversity of gut bacteria in sand flies are influenced by their feeding habits and infection status. Sucrose-fed Lu. longipalpis has the most diverse microbiome [196], but this diversity decreases with blood meals, most likely owing to the antimicrobial effects of blood. However, microbial diversity recovers after blood digestion. This pattern is also seen in Lu. intermedia, with gravid females showing similar microbial diversity to non-fed females [197]. Across all groups (sucrose-fed, blood-fed and infected), the genera Stenotrophomonas, Serratia, Pantoea and Erwinia are consistently present [197].

Role of the gut microbiome in sand flies

The gut microbiome plays a vital role in various physiological and ecological processes in sand flies, contributing to functions such as development, pathogen resistance, nutrient acquisition and oviposition [7, 187]. Research has shown that bacteria play a crucial role in the oviposition behaviour of sand flies. The oviposition preferences of Lu. longipalpis were assessed using both sterile and non-sterile rabbit faeces. The findings revealed that gravid females laid the majority of their eggs on the non-sterile substrate, demonstrating a strong attraction to rabbit faeces containing a live microbial community. This suggests that the presence of bacteria significantly influences the oviposition site selection of the sand fly [187]. Gut bacteria are essential for the proper development of sand fly larvae. In the study by Peterkova-Koci et al., larvae fed on sterile rabbit faeces showed delayed progression to adulthood and reduced survival compared with those given sterilised faeces supplemented with Rhizobium radiobacter or Bacillus species. Interestingly, R. radiobacter was more effective in facilitating larval development than Bacillus spp. suggesting that certain bacteria play a key role in providing essential nutrients, such as amino acids and vitamins [187].

Notably, L. mexicana-infected sand flies demonstrated that survival rates were high when challenged with S. marcescens compared with uninfected flies [205]. The persistence of neutrophils at bite sites, where they shield captured parasites and exacerbate disease, is a notable characteristic of Leishmania transmitted by vectors. Studies have shown that, alongside the Leishmania parasites, gut microbes from the sand fly are also introduced into the host’s skin. These microbes activate the inflammasome, rapidly releasing interleukin (IL)-1β, which sustains neutrophil infiltration. This suggests a shared mechanism of the microbiota that contributes to the severity of the infection [182]. These results suggest a potential mutualistic relationship, where Leishmania may protect the sand fly from bacterial infection or modulate the immune response, benefiting both the host and the parasite.

In female sand flies, Leishmania parasites and various bacterial species co-exist in the gut. Several studies hypothesise that the sand fly midgut bacteria can affect parasite development by lowering the intestinal pH and competing with the parasite for nutrients and adhesion sites in the vector’s gut (Fig. 6) [198]. Studies have shown that certain gut microbiota components can interfere with Leishmania development. For example, S. marcescens, has been reported to negatively affect L. infantum by producing prodigiosin, a compound that induces lysis of the parasite’s cell membrane (Fig. 6) [206, 207]. Supporting this, an in vivo study demonstrated that Lu. longipalpis fed on a microbial suspension containing Asaia sp., Pseudozyma sp. or Ochrobactrum intermedium exhibited reduced infection rates of L. mexicana in sand flies [205].

Fig. 6.

The role of sand fly midgut microbiota, particularly S. marcescens, in modulating the Leishmania parasite development. Figure created with BioRender.com

Interestingly, research by Hassan et al. showed that P. papatasi treated with antibiotics were more susceptible to L. major infection compared with untreated controls, indicating that gut symbionts contribute to resistance against Leishmania [186]. However, in contrast to these findings, emerging evidence suggests that the native gut microbiota may be crucial for Leishmania survival and development [196]. Disruption of this microbiota through antibiotic treatment has been shown to impair the parasite’s growth and hinder its differentiation into the infectious metacyclic form. This highlights the complex and potentially supportive role that the microbial community plays in the life cycle of Leishmania within its sand fly vector.

Gut bacteria might indirectly support Leishmania development by producing anti-fungal compounds that eliminate fungi from the gut. This is significant, as sand flies infected with fungi are less competent vectors than those with fungi-free guts [208] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The role of antifungal compounds produced by sand fly midgut microbiota in enhancing Leishmania development. Figure created with BioRender.com

Conclusions

The microbiome of mosquitoes and sand flies plays a crucial role in shaping their vector competence, thereby influencing the transmission dynamics of numerous vector-borne pathogens. These complex microbial communities, influenced by host genetics, environmental factors and pathogen exposure, interact intricately with their insect hosts and can influence their fitness, development and fecundity. The microbiome also contributes to insecticide resistance and helps regulate the immune response, thereby influencing disease transmission. Certain microbial taxa are known to interact directly with pathogens, facilitating conditions that enhance their survival and transmission. In other cases, the microbiome modulates host immune pathways, potentially promoting vector longevity. Targeting these complex microbe, host and pathogen interactions presents a promising and sustainable strategy for future vector control. Innovations in microbiome engineering, such as enhancing beneficial microbial communities to reduce vector competence or introducing genetically modified microbes to inhibit pathogen transmission, may offer eco-friendly alternatives to conventional chemical control methods. Future research should focus on unravelling the molecular mechanisms by which microbiomes influence vector competence. Longitudinal studies tracking microbiome composition across developmental stages, species and environmental contexts could provide valuable insights into the dynamic interplay between vectors and their microbial communities. Integrating microbiome research with cutting-edge fields such as genomics, immunology and ecological modelling will be crucial for translating these discoveries into effective vector control tools. Collaborative, interdisciplinary efforts will be essential to fully realise the potential of microbiome-based strategies for reducing the global burden of VBDs. A deeper understanding of microbial communities and their roles in the fitness and competence of the vector can be beneficial for controlling VBDs.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the ICMR-Vector Control Research Centre Director for providing encouragement, guidance and useful suggestions for planning and designing this review. All the authors have consented to the acknowledgement.

Abbreviations

- DENV

Dengue virus

- RVF

Rift Valley virus

- ZIKV

Zika virus

- CHIKV

Chikungunya virus

- YFV

Yellow fever virus

- WNV

West Nile virus

- JEV

Japanese encephalitis virus

- VBDs

Vector-borne diseases

- ONNV

O’nyong’nyong virus

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- AMP

Anti-microbial peptide

- Csp_P

Chromobacterium Sp. Panama

- GSTs

Glutathione-S-transferases

- CFAV

Cell-fusing agent virus

- NHUV

Nhumirim virus

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.A.N., R.S. and G.R. Validation: G.R., R.S. and M.K.M. Writing and original draft preparation: G.R. and M.K.M. Figures: G.R. Review and editing: R.S., S.A.N., M.R., N.B. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This activity did not receive any funding.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the main conclusions of this study are included in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rohit Sharma, Email: rohitah.sharma@gmail.com.

Shriram Ananganallur Nagarajan, Email: shriram.an@icmr.gov.in, Email: anshriram@gmail.com.

References

- 1.WHO. Global vector control response 2017–2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512978. Accessed 22 Jun 2025.

- 2.de Souza WM, Weaver SC. Effects of climate change and human activities on vector-borne diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024;22:476–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Malaria’s Impact Worldwide. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/php/impact/index.html. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 4.Ogunlade ST, Meehan MT, Adekunle AI, Rojas DP, Adegboye OA, McBryde ES. A review: Aedes-borne arboviral infections, controls and Wolbachia-based strategies. Vaccines. 2021;9:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Rift Valley fever. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rift-valley-fever. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 6.Madhav M, Blasdell KR, Trewin B, Paradkar PN, López-Denman AJ. Culex-transmitted diseases: mechanisms, impact, and future control strategies using Wolbachia. Viruses. 2024;16:1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telleria EL, Martins-da-Silva A, Tempone AJ, Traub-Csekö YM. Leishmania, microbiota and sand fly immunity. Parasitology. 2018;145:1336–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Medical Vet Entomology. 2013;27:123–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Depaquit J, Grandadam M, Fouque F, Andry PE, Peyrefitte C. Arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by Phlebotomine sandflies in Europe: a review. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt PN, Rodrigues FM. Chandipura: a new arbovirus isolated in India from patients with febrile illness. Indian J Med Res. 1967;55:1295–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M. Anopheles funestus resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargreaves K, Hunt RH, Brooke BD, Mthembu J, Weeto MM, Awolola TS, et al. Anopheles arabiensis and An. quadriannulatus resistance to DDT in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2003;17:417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1084–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar G, Baharia R, Singh K, Gupta SK, Joy S, Sharma A, et al. Addressing challenges in vector control: a review of current strategies and the imperative for novel tools in India’s combat against vector-borne diseases. BMJ Public Health. 2024;2: e000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hassan MM, Widaa SO, Osman OM, Numiary MSM, Ibrahim MA, Abushama HM. Insecticide resistance in the sand fly, Phlebotomus papatasi from Khartoum State, Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhiman RC, Yadav RS. Insecticide resistance in phlebotomine sandflies in Southeast Asia with emphasis on the Indian subcontinent. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;05:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Nair S. Dynamics of insect-microbiome interaction influence host and microbial symbiont. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wu VY, Chen B, Christofferson R, Ebel G, Fagre AC, Gallichotte EN, et al. A minimum data standard for vector competence experiments. Sci Data. 2022;9:634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Gao L, Aksoy S. Microbiota in disease-transmitting vectors. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:604–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jupatanakul N, Sim S, Dimopoulos G. The insect microbiome modulates vector competence for arboviruses. Viruses. 2014;6:4294–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Clayton AM, Sandiford SL, Souza-Neto JA, Mulenga M, et al. Natural microbe-mediated refractoriness to Plasmodium infection in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2011;332:855–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss B, Aksoy S. Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:514–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi Z, Khoo CCH, Dobson SL. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 2005;310:326–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennison NJ, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. The mosquito microbiota influences vector competence for human pathogens. Curr Opinion in Insect Sci. 2014;3:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce JD, Nogueira JR, Bales AA, Pittman KE, Anderson JR. Interactions between La Crosse virus and bacteria isolated from the digestive tract of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2011;48:389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azambuja P, Garcia ES, Ratcliffe NA. Gut microbiota and parasite transmission by insect vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:568–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegde S, Nilyanimit P, Kozlova E, Anderson ER, Narra HP, Sahni SK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene deletion of the ompA gene in symbiotic Cedecea neteri impairs biofilm formation and reduces gut colonization of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stathopoulos S, Neafsey DE, Lawniczak MKN, Muskavitch MAT, Christophides GK. Genetic dissection of Anopheles gambiae gut epithelial responses to Serratia marcescens. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onyango GM, Bialosuknia MS, Payne FA, Mathias N, Ciota TA, Kramer DL. Increase in temperature enriches heat tolerant taxa in Aedes aegypti midguts. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muturi EJ, Lagos-Kutz D, Dunlap C, Ramirez JL, Rooney AP, Hartman GL, et al. Mosquito microbiota cluster by host sampling location. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novakova E, Woodhams DC, Rodríguez-Ruano SM, Brucker RM, Leff JW, Maharaj A, et al. Mosquito microbiome dynamics, a background for prevalence and seasonality of West Nile virus. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kieran TJ, Arnold KMH, Thomas JC, Varian CP, Saldaña A, Calzada JE, et al. Regional biogeography of microbiota composition in the Chagas disease vector Rhodnius pallescens. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Díaz-Sánchez S, Hernández-Jarguín A, Torina A, Fernández de Mera IG, Estrada-Peña A, Villar M, et al. Biotic and abiotic factors shape the microbiota of wild-caught populations of the arbovirus vector Culicoides imicola. Insect Mol Bio. 2018;27:847–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang X, Wang Y, Li S, Sun X, Lu X, Rajaofera MJN, et al. Comparative analysis of the gut microbiota of adult mosquitoes from eight locations in Hainan. China Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:596750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J-H, Lee H-I, Kwon H-W. Geographical characteristics of Culex tritaeniorhynchus and Culex orientalis microbiomes in Korea. Insects. 2024;15:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otani S, Lucati F, Eberhardt R, Møller FD, Caner J, Bakran-Lebl K, et al. Mosquito-borne bacterial communities are shaped by their insect host species, geography and developmental stage. 2025.

- 37.Karimian F, Koosha M, Choubdar N, Oshaghi MA. Comparative analysis of the gut microbiota of sand fly vectors of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis (ZVL) in Iran; host-environment interplay shapes diversity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabbabi A, Mizushima D, Yamamoto DS, Zhioua E, Kato H. Comparative analysis of the microbiota of sand fly vectors of Leishmania major and L. tropica in a mixed focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in southeast Tunisia; ecotype shapes the bacterial community structure. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickson LB, Jiolle D, Minard G, Moltini-Conclois I, Volant S, Ghozlane A, et al. Carryover effects of larval exposure to different environmental bacteria drive adult trait variation in a mosquito vector. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1700585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apte-Deshpande A, Paingankar M, Gokhale MD, Deobagkar DN. Serratia odorifera a midgut inhabitant of Aedes aegypti mosquito enhances its susceptibility to dengue-2 virus. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saraiva RG, Fang J, Kang S, Angleró-Rodríguez YI, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Aminopeptidase secreted by Chromobacterium sp. Panama inhibits dengue virus infection by degrading the E protein. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun X, Wang Y, Yuan F, Zhang Y, Kang X, Sun J, et al. Gut symbiont-derived sphingosine modulates vector competence in Aedes mosquitoes. Nat Commun. 2024;15:8221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bahia AC, Dong Y, Blumberg BJ, Mlambo G, Tripathi A, BenMarzouk-Hidalgo OJ, et al. Exploring Anopheles gut bacteria for Plasmodium blocking activity. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2980–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noden BH, Vaughan JA, Pumpuni CB, Beier JC. Mosquito ingestion of antibodies against mosquito midgut microbiota improves conversion of ookinetes to oocysts for Plasmodium falciparum, but not P. yoelii. Parasitol Int. 2011;60:440–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Louradour I, Monteiro CC, Inbar E, Ghosh K, Merkhofer R, Lawyer P, et al. The midgut microbiota plays an essential role in sand fly vector competence for Leishmania major. Cell Microbiol. 2017;19:12755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Baral S, Gautam I, Singh A, Chaudhary R, Shrestha P, Tuladhar R. Microbiota diversity associated with midgut and salivary gland of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Tribhuvan Univer J Microbiol. 2023;10:105–15. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Accoti A, Damiani C, Nunzi E, Cappelli A, Iacomelli G, Monacchia G, et al. Anopheline mosquito saliva contains bacteria that are transferred to a mammalian host through blood feeding. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1157613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma E, Zhu Y, Liu Z, Wei T, Wang P, Cheng G. Interaction of viruses with the insect intestine. Annu Rev Virol. 2021;8:115–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strand MR. Composition and functional roles of the gut microbiota in mosquitoes. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018;28:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mancini MV, Damiani C, Accoti A, Tallarita M, Nunzi E, Cappelli A, et al. Estimating bacteria diversity in different organs of nine species of mosquito by next generation sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma P, Sharma S, Maurya RK, De Das T, Thomas T, Lata S, et al. Salivary glands harbor more diverse microbial communities than gut in Anopheles culicifacies. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tchioffo MT, Boissière A, Abate L, Nsango SE, Bayibéki AN, Awono-Ambéné PH, et al. Dynamics of bacterial community composition in the malaria mosquito’s Epithelia. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Díaz S, Camargo C, Avila FW. Characterization of the reproductive tract bacterial microbiota of virgin, mated, and blood-fed Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus females. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricci I, Damiani C, Scuppa P, Mosca M, Crotti E, Rossi P, et al. The yeast Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Pichia anomala) inhabits the midgut and reproductive system of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:911–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segata N, Baldini F, Pompon J, Garrett WS, Truong DT, Dabiré RK, et al. The reproductive tracts of two malaria vectors are populated by a core microbiome and by gender- and swarm-enriched microbial biomarkers. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dada N, Lol JC, Benedict AC, López F, Sheth M, Dzuris N, et al. Pyrethroid exposure alters internal and cuticle surface bacterial communities in Anopheles albimanus. ISME J. 2019;13:2447–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.dos Santos NAC, de Carvalho VR, Souza-Neto JA, Alonso DP, Ribolla PEM, Medeiros JF, et al. Bacterial microbiota from lab-reared and field-captured Anopheles darlingi midgut and salivary gland. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berhanu A, Abera A, Nega D, Mekasha S, Fentaw S, Assefa A, et al. Isolation and identification of microflora from the midgut and salivary glands of Anopheles species in malaria endemic areas of Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salgado JFM, Premkrishnan BNV, Oliveira EL, Vettath VK, Goh FG, Hou X, et al. The dynamics of the midgut microbiome in Aedes aegypti during digestion reveal putative symbionts. PNAS Nexus. 2024;3:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, Liu T, Wu Y, Zhong D, Zhou G, Su X, et al. Bacterial microbiota assemblage in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and its impacts on larval development. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2972–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gimonneau G, Tchioffo MT, Abate L, Boissière A, Awono-Ambéné PH, Nsango SE, et al. Composition of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae microbiota from larval to adult stages. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;28:715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilke ABB, Marrelli MT. Paratransgenesis: a promising new strategy for mosquito vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slatko BE, Luck AN, Dobson SL, Foster JM. Wolbachia endosymbionts and human disease control. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2014;195:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodgers FH, Gendrin M, Wyer CAS, Christophides GK. Microbiota-induced peritrophic matrix regulates midgut homeostasis and prevents systemic infection of malaria vector mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harrison RE, Yang X, Eum JH, Martinson VG, Dou X, Valzania L, et al. The mosquito Aedes aegypti requires a gut microbiota for normal fecundity, longevity and vector competence. Commun Biol. 2023;6:1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balaji S, Shekaran SG, Prabagaran SR. Cultivable bacterial communities associated with the salivary gland of Aedes aegypti. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2021;41:1203–11. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chavshin AR, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Yakhchali B, Zarenejad F, Terenius O. Malpighian tubules are important determinants of Pseudomonas transstadial transmission and longtime persistence in Anopheles stephensi. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang S, Dos-Santos ALA, Huang W, Liu KC, Oshaghi MA, Wei G, et al. Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria. Science. 2017;357:1399–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scolari F, Casiraghi M, Bonizzoni M. Aedes spp. and their microbiota: a review. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects – Diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Waters JL, Clark AG, Ley RE. Cross-species comparisons of host genetic associations with the microbiome. Science. 2016;352:532–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee W-J, Brey PT. How microbiomes influence metazoan development: insights from history and Drosophila modeling of gut-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:571–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Gaio AO, Gusmão DS, Santos AV, Berbert-Molina MA, Pimenta PFP, Lemos FJA. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (diptera: culicidae) (L.). Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen S, Bagdasarian M, Walker ED. Elizabethkingia anophelis: molecular manipulation and interactions with mosquito hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:2233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cappelli A, Damiani C, Mancini MV, Valzano M, Rossi P, Serrao A, et al. Asaia activates immune genes in mosquito eliciting an anti-plasmodium response: implications in malaria control. Front Genet. 2019;10:836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ramirez JL, Short SM, Bahia AC, Saraiva RG, Dong Y, Kang S, et al. Chromobacterium Csp_P reduces malaria and dengue infection in vector mosquitoes and has entomopathogenic and in vitro anti-pathogen activities. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bai L, Wang L, Vega-Rodríguez J, Wang G, Wang S. A Gut symbiotic bacterium Serratia marcescens renders mosquito resistance to Plasmodium infection through activation of mosquito immune responses. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y, Eum J-H, Harrison RE, Valzania L, Yang X, Johnson JA, et al. Riboflavin instability is a key factor underlying the requirement of a gut microbiota for mosquito development. Proceed Nat Acad Sci. 2021;118:e2101080118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hinman EH. A study of the food of mosquito larvae (Culicidae). Am J Epidemiol. 1930;12:238–70. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chao J, Wistreich G. Microbial isolations from the mid-gut of Culex tarsalis Coquillett. 1959.

- 83.Minard G, Mavingui P, Moro CV. Diversity and function of bacterial microbiota in the mosquito holobiont. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coon K, Vogel K, Brown M, Strand M. Mosquitoes rely on their gut microbiota for development. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2727–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coon KL, Brown MR, Strand MR. Gut bacteria differentially affect egg production in the anautogenous mosquito Aedes aegypti and facultatively autogenous mosquito Aedes atropalpus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindh JM, Borg-Karlson A-K, Faye I. Transstadial and horizontal transfer of bacteria within a colony of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) and oviposition response to bacteria-containing water. Acta Trop. 2008;107:242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scolari F, Sandionigi A, Carlassara M, Bruno A, Casiraghi M, Bonizzoni M. Exploring changes in the microbiota of Aedes albopictus: comparison among breeding site water, larvae, and adults. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:624170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang Y, Gilbreath TM, Kukutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coon KL, Valzania L, McKinney DA, Vogel KJ, Brown MR, Strand MR. Bacteria-mediated hypoxia functions as a signal for mosquito development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E5362–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rozeboom LE. The relation of bacteria and bacterial filtrates to the development of mosquito larvae. Am J Epidemiol. 1935;21:167–79. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Correa MA, Matusovsky B, Brackney DE, Steven B. Generation of axenic Aedes aegypti demonstrate live bacteria are not required for mosquito development. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gillett JD, Roman EA, Phillips V. Erratic hatching in Aedes eggs: a new interpretation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977;196:223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ponnusamy L, Böröczky K, Wesson DM, Schal C, Apperson CS. Bacteria stimulate hatching of yellow fever mosquito eggs. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ponnusamy L, Xu N, Nojima S, Wesson DM, Schal C, Apperson CS. Identification of bacteria and bacteria-associated chemical cues that mediate oviposition site preferences by Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reeves WK. Oviposition by Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to conspecific larvae infected with internal symbiotes. J Vector Ecol. 2004;29:159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barredo E, DeGennaro M. Not just from blood: mosquito nutrient acquisition from nectar sources. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:473–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Foster W. Mosquito sugar feeding and reproductive energetics. Annu Rev Entomol. 1995;40:443–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duneau D, Lazzaro B. Persistence of an extracellular systemic infection across metamorphosis in a holometabolous insect. Biol Lett. 2018;14:20170771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alfano N, Tagliapietra V, Rosso F, Manica M, Arnoldi D, Pindo M, et al. Changes in microbiota across developmental stages of Aedes koreicus, an invasive mosquito vector in Europe: indications for microbiota-based control strategies. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Galeano-Castañeda Y, Urrea-Aguirre P, Piedrahita S, Bascuñán P, Correa MM. Composition and structure of the culturable gut bacterial communities in Anopheles albimanus from Colombia. Lanz-Mendoza H, editor. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Muturi EJ, Dunlap C, Ramirez JL, Rooney AP, Kim C-H. Host blood-meal source has a strong impact on gut microbiota of Aedes aegypti. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2019;95:fiy213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guégan M, Van Tran V, Martin E, Minard G, Tran F-H, Fel B, et al. Who is eating fructose within the Aedes albopictus gut microbiota? Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:1193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu N, Zhu F, Xu Q, Pridgeon J, Gao X. Behavioral change, physiological modification, and metabolic detoxification: mechanisms of insecticide resistance. 2006;49:671–9.

- 104.Khan S, Uddin M, Rizwan M, Khan W, Farooq M, Shah AS, et al. Mechanism of insecticide resistance in insects/pests. Pol J Environ Stud. 2020;29:2023–30. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deng S, Tu L, Li L, Hu J, Li J, Tang J, et al. A symbiotic bacterium regulates the detoxification metabolism of deltamethrin in Aedes albopictus. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2025;212:106445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang H, Liu H, Peng H, Wang Y, Zhang C, Guo X, et al. A symbiotic gut bacterium enhances Aedes albopictus resistance to insecticide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bhatt P, Bhatt K, Huang Y, Lin Z, Chen S. Esterase is a powerful tool for the biodegradation of pyrethroid insecticides. Chemosphere. 2020;244:125507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berticat C, Rousset F, Raymond M, Berthomieu A, Weill M. High Wolbachia density in insecticide-resistant mosquitoes. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269:1413–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang Y-T, Shen R-X, Xing D, Zhao C-P, Gao H-T, Wu J-H, et al. Metagenome sequencing reveals the midgut microbiota makeup of culex pipiens quinquefasciatus and its possible relationship with insecticide resistance. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:625539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bharadwaj N, Sharma R, Subramanian M, Ragini G, Nagarajan SA, Rahi M. Omics approaches in understanding insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Hou Z, Wang X, Wang J, Lu Z, et al. Biodegradation potential of deltamethrin by the Bacillus cereus strain Y1 in both culture and contaminated soil. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2016;106:53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Paingankar M, Jain M, Deobagkar D. Biodegradation of allethrin, a pyrethroid insecticide, by an Acidomonas sp. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen S, Lai K, Li Y, Hu M, Zhang Y, Zeng Y. Biodegradation of deltamethrin and its hydrolysis product 3-phenoxybenzaldehyde by a newly isolated Streptomyces aureus strain HP-S-01. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hao X, Zhang X, Duan B, Huo S, Lin W, Xia X, et al. Screening and genome sequencing of deltamethrin-degrading bacterium ZJ6. Curr Microbiol. 2018;75:1468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liang WQ, Wang ZY, Li H, Wu PC, Hu JM, Luo N, et al. Purification and characterization of a novel pyrethroid hydrolase from Aspergillus niger ZD11. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:7415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Singh BK. Organophosphorus-degrading bacteria: ecology and industrial applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tago K, Yonezawa S, Ohkouchi T, Hashimoto M, Hayatsu M. Purification and characterization of fenitrothion hydrolase from Burkholderia sp. NF100. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;101:80–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kikuchi Y, Hayatsu M, Hosokawa T, Nagayama A, Tago K, Fukatsu T. Symbiont-mediated insecticide resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8618–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang Q, Li S, Ma C, Wu N, Li C, Yang X. Simultaneous biodegradation of bifenthrin and chlorpyrifos by Pseudomonas sp. CB2. J Environ Sci Health B. 2018;53:304–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Soltani A, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Enayati AA, Chavshin AR. The role of midgut symbiotic bacteria in resistance of Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) to organophosphate insecticides. Pathogens Global Health. 2017;111:289–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lewis J, Gallichotte EN, Randall J, Glass A, Foy BD, Ebel GD, et al. Intrinsic factors driving mosquito vector competence and viral evolution: a review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1330600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Saraiva RG, Huitt-Roehl CR, Tripathi A, Cheng Y-Q, Bosch J, Townsend CA, et al. Chromobacterium spp. mediate their anti-Plasmodium activity through secretion of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ramirez JL, Souza-Neto J, Torres Cosme R, Rovira J, Ortiz A, Pascale JM, et al. Reciprocal tripartite interactions between the Aedes aegypti midgut microbiota, innate immune system and dengue virus influences vector competence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carissimo G, Pondeville E, McFarlane M, Dietrich I, Mitri C, Bischoff E, et al. Antiviral immunity of Anopheles gambiae is highly compartmentalized, with distinct roles for RNA interference and gut microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Angleró-Rodríguez YI, Talyuli OA, Blumberg BJ, Kang S, Demby C, Shields A, et al. An Aedes aegypti-associated fungus increases susceptibility to dengue virus by modulating gut trypsin activity. Elife. 2017;6:e28844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Charan SS, Pawar KD, Severson DW, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Comparative analysis of midgut bacterial communities of Aedes aegypti mosquito strains varying in vector competence to dengue virus. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:2627–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Short SM, Mongodin EF, MacLeod HJ, Talyuli OAC, Dimopoulos G. Amino acid metabolic signaling influences Aedes aegypti midgut microbiome variability. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zink SD, Van Slyke GA, Palumbo MJ, Kramer LD, Ciota AT. Exposure to west nile virus increases bacterial diversity and immune gene expression in culex pipiens. Viruses. 2015;7:5619–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]