Abstract

Background

Paris polyphylla (P. polyphylla), a medicinal herb valued in traditional Chinese medicine, struggles with slow growth rate and long maturation periods, hindering sustainable cultivation and commercial production—especially for polyphyllins, its key bioactive compounds. Although plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have shown potential in enhancing crop productivity and secondary metabolite accumulation, their application in slow-growing medicinal plants like P. polyphylla remains underexplored.

Results

In this study, 25 strains with inorganic phosphorus-dissolving, potassium-solubilizing and nitrogen-fixing abilities were isolated from the rhizosphere soil of P. polyphylla, mainly belonging to Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Rhizobium. Among them, the strain Pseudomonas palleroniana P6 exhibited the best growth-promoting effect on grass. The whole genome analysis demonstrated that P. palleroniana P6 could promote forage growth by secreting phosphatases, organic acids, and producing substances like IAA and siderophore. Field experiments were carried out to further validate the impact of P. palleroniana P6 on the growth of P. polyphylla. The results revealed that P. palleroniana P6 remarkably enhanced the biomass of P. polyphylla root and the content of polyphyllin I, II, and VII, and significantly increased the soil available potassium content. The transcriptome results indicated that the application of P. palleroniana P6 considerably increased the expression of genes related to the plant hormone signal transduction pathway involved in growth regulation, cholesterol synthesis, terpenoid backbone synthesis and the energy metabolism pathway associated with polyphyllins synthesis in P. polyphylla.

Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the growth-promoting effects and secondary metabolic regulation mechanisms of the bacterial inoculant P. palleroniana P6 on the endangered medicinal plant P. polyphylla. The findings highlight the potential of P. palleroniana P6 in promoting plant growth and enhancing polyphenol accumulation in P. polyphylla, providing valuable insights for the application of microbial inoculants in enhancing the growth and bioactive compound production of perennial medicinal plants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07168-4.

Keywords: Paris polyphylla, Pseudomonas palleroniana P6, Plant growth-promoting, Polyphyllins accumulation

Introduction

Paris polyphylla (P. polyphylla) is a key component in over 80 traditional Chinese medicines, including Yunnan Baiyao, ZhongLouJieDuDing and LouLianJiaoNang [1, 2]. Its therapeutic efficacy stems from polyphyllins with hemostasis, analgesia, antibacterial, and antitumor activitie [3]. Among over 50 identified polyphyllins, types I, II, VI, and VII exhibit the most potent pharmacological profiles [4, 5]. For instance, polyphyllin I inhibits non-small cell lung cancer growth by inducing autophagy to activate AMPK activated protein kinase [6], while polyphyllin II suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation via AKT/NF-κB pathway inactivation [7, 8]. Li et al. further demonstrated that polyphyllin VII triggers STAT3-dependent apoptosis in HepG2 and Huh7 cells, effectively blocking liver cancer progression [9].

Despite an annual demand of approximately 1500 tons, wild P. polyphylla resource yields are insufficient to meet market needs [10, 11]. Artificial cultivation is hindered by long growth cycles and poor environmental adaptability. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB), known for enhancing plant resilience and nutrient acquisition, offer a sustainable solution [12, 13]. Previous studies have confirmed that PGPB possess multifunctional capabilities, including phosphorus solubilization, potassium mobilization, and nitrogen fixation, while also secreting phytohormones (e.g., indoleacetic acid, gibberellins) and siderophores to promote plant growth [14]. These attributes underscore their pivotal role in agricultural production and ecosystem sustainability [15, 16].

Recent studies have attempted PGPB to address the prolonged growth cycles of P. polyphylla. Phosphorus and potassium are critical nutrients for it growth, and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria application has been shown to improve soil nutrient structure while significantly enhancing root biomass and polyphyllins content [17]. For instance, Li et al. isolated three organic phosphorus-degrading bacteria strains (Bacillus mycoides, B. wiedmannii, and B. protolyticus) from the rhizosphere soil of P. polyphylla. Individual or combined inoculation of these strains enhanced rhizome biomass by 134.6% and total steroidal saponins by 132.6%, with polyphyllin I, II, VII, H, and diosgenin exhibited the most marked increases (87.8% − 245.7%) [17]. Similarly, co-inoculation of Paenibacillus amylolyticus and Bacillus polymyxa (potassium-mobilizing bacteria) significantly improved soil available potassium levels and elevated pseudodiosgenin and diosgenin H content in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, thereby boosting its medicinal quality [18].

Notably, P. polyphylla selectively enriches PGPB (e.g., Pseudomonas, Rhizobia, and Agrobacterium) in the roots from the rhizosphere and bulk soil with time, suggesting active microbial recruitment [19, 20]. Building on this, we isolated inorganic phosphorus-dissolving, potassium-solubilizing, and nitrogen-fixing strains from rhizosphere samples. Strain Pseudomonas. palleroniana P6, identified via grass growth experiments, auxin (IAA) production assays, and genomic analysis, demonstrated superior growth-promoting potential. Field experiments were conducted to assess its effects on soil physicochemical properties, root quality, and polyphyllins accumulation, complemented by transcriptomics to elucidate regulatory on the growth and metabolism mechanisms. The study provides actionable insights for optimizing microbial inoculants in P. polyphylla cultivation.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and processing

According to previous laboratory findings that plant growth-promoting bacterial (PGPB) are significantly enriched in the rhizosphere and bulk soil of P. polyphylla during its second growth year [19], bulk and rhizosphere soil samples were collected to isolate bacterial strains with inorganic phosphorus dissolution, potassium solubilization, and nitrogen fixation capabilities. Samples were performed in a 3 m × 3 m quadrat in Jiudingshan, Dali City, Yunnan Province (25°20′24″N, 100°29′18″E). Fifteen P. polyphylla plants of similar size and were randomly selected from each quadrat using a five-point sampling method. Bulk soil (5 cm away from roots, 5–15 cm depth) and rhizosphere soil (collected by vortexing roots in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, followed by centrifugation at 9000 ×g) were processed. Samples (1 g) were diluted in sterile double-distilled water (10−4, 10−5, and 10−6), plated on Inorganic phosphorus medium, Dissolved potassium medium, and Ashby’s nitrogen-free medium, and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. Colonies were purified via subculture.

Functional verification of PGPB strains

Single bacteria colony diameters on selective medium were measured after 7-day inoculated (30 °C) to assess growth rates. Strains were classified as: “-” (no growth), “+” (< 2 cm), “++” (2–4 cm), or “+++” (> 4 cm). Pseudomonas sp. P6 and N5 (highest phosphorus solubilization, potassium solubilization, and nitrogen fixation efficiencies) were selected for pot experiments. Nursery Soil (Jiudingshan, Dali) were sieved (2 mm), homogenized, and aliquoted (n = 30). Bacterial suspensions (1 × 10⁹ CFU/mL in PBS) were applied as: T1 (treated with 15 mL of Pseudomonas sp. P6), T2 (treated with 15 mL of Pseudomonas sp. N5), and CK (treated with 15 mL of sterile water), with 10 replicates each. After pre-incubation (25 °C, 60% RH, 1 month), five grass seeds were sown per pot under 10 h light/14 h dark cycle (1000 lx). Root length, root number, and plant height were recorded at day 15. According to the growth of the grass, further use a modified protocol to quantify the optimal strain’s ability to synthesize IAA [21]. 100 µL of Pseudomonas sp. P6 bacterial solution was inoculated into 10 ml of King’s B broth with and without 0.4% L-tryptophan, respectively. The control was to add an equal amount of sterile water to King’s medium containing 0.4% L-tryptophan and without L-tryptophan. Biological triplicates were performed. Then place it in a shaker and incubate at 30 ℃ and 170 rpm for 5 days. Cell-free supernatant (200 µL) was mixed with 200 µL Salkowski reagent (0.5 M FeCl₃ in 35% HClO₄). After 30 min dark incubation, IAA concentration was quantified by measuring absorbance at 530 nm, with higher absorbance values corresponding to greater IAA production. The growth of grass and the production of IAA by Pseudomonas sp. P6 were both statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA (SPSS v27).

DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing

Bacterial strains with highest capabilities were selected for DNA extraction using the OMEGA bacterial genome DNA extraction kit (OMEGA Biotek, USA). The 16S rDNA gene were amplified by PCR (25 µL reaction volume: 12.5 µL 2× Taq Mix, 1.0 µL template DNA, 1.0 µL each of primers 27 F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R (5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’), 9.5 µL ddH₂O) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C (5 min); 30 cycles of 94 °C (1 min), 60 °C (1 min), 72 °C (1 min); final extension at 72 °C (5 min). PCR products were verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis [22] and sequenced by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Sequences were aligned via NCBI BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA XI [23].

Whole genome sequencing was conducted at Majorbio (Shanghai, China) using Illumina Hiseq (8–10 kb) and PacBio platforms (~ 400 bp) platforms. To ensure sufficient assembly, the sequencing depth met the requirements. Sequencing depth ensured sufficient assembly, and data quality was assessed. Clean data were obtained by removing poly-N and low-quality reads from raw data. Assembly was performed using Canu and SPAdes to generate plasmid and chromosome sequences [24]. Coding sequences were predicted by Glimmer, GeneMarkS, and Prodigal [25]. Genome islands, prophages, and CRISPR-Cas were identified with IslandViewer, PHAST, and Minced, respectively [26]. Taxonomic classification utilized ANI (average-nucleotide identity) and TNA (tetra-nucleotide analysis) analyses (JSpecies, https://jspecies.ribohost.com) [27]. Functional annotation was performed using databases such as KEGG, NR, SwissProt, Pfam, GO, and COG [28]. Carbohydrate-active enzymes and Secondary metabolic synthesis gene clusters were annotated via the carbohydrate activity enzyme database (CAZy) [29, 30] and antisSMASH [31], respectively.

Field experiments

Base description and field experiment design

The field experiment was conducted at a P. polyphylla cultivation base in Nantangtian Village, Dali City, Yunnan Province (25°31′8″N, 100°20′34″E), under a humid subtropical climate (mean annual temperature: 15.1 ℃, precipitation: 1078.9 mm, sunshine: 2228.1 h). P. polyphylla were grown in greenhouses with semi-humid humus soil under uniform irrigation and fertilization (base fertilizer applied pre- -planting, no supplemental fertilization). Seeds from genetically homogeneous maternal plants were sown in October 2019, yielding uniform growth. Twelve (1 m × 1 m) quadrats were established, with six quadrats randomly treated with bacterial agents (OP), and the remaining six quadrats with an equal amount of water (OC).

Bacterial agent preparation and application

Pseudomonas sp. P6 was initially cultured in Nutrient Broth (30 ℃, 180 rpm, 12 h) as a seed culture. The culture was then scaled to 6 L (24 h, 170 rpm), achieving a bacterial concentration > 1 × 10⁹ CFU/mL. Cells were centrifuged (10,000 ×g, 10 min), washed thrice with sterile water, freeze-dried (−55 ℃), and stored (−20 ℃). According to the phenological pattern of P. polyphylla (seedlings typically emerge in mid-March), freeze-dried inoculant was reactivated on February 8, 2022 (one month pre-emergence), resuspended in 6 L water, distributed into six 20 L volumes, and sprayed twice daily (08:00 and 14:00) via agro-atomizer.

Sample collection and property

Soil (2 kg per quadrat, 3–15 cm deep) were collected via five-point sampling on February 7 (pre-treatment) and November 7, 2022 (9-month post-treatment). Samples were labeled OP1 - OP6 (treatment) and OC1–OC6 (control) pre-application, labeling to FP1 - FP6 and FC1 - FC6 post-application. Five roots of P. polyphylla were collected from each quadrat. A part analyzed for biomass and polyphyllins content (HPLC). The other surface-sterilized (75% ethanol, 2 min), rinsed five times with sterile water, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C for transcriptomics and metabolomics.

Determination of soil physical and chemical characteristics

Studies have shown that PGPBs are crucial for nutrient uptake, soil improvement, and plant growth [32]. The physical and chemical properties of soils form the four groups were analyzed. The soil samples were dried at 60 ℃ and passed through a 0.22 mm sieve. Soil pH was measured by a pH meter (PHSJ-4 A, Leici, Shanghai, China) [33]. Total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), water-soluble nitrogen (WSN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), total potassium (TK), and available potassium (AK) were determined according to national standard testing methods [19]. Soil physical and chemical characteristics data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test for multiple comparisons, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (SPSS v27).

Determination of growth characteristics of P. polyphylla

The fresh weight (FW) of five P. polyphylla root tubers per quadrat were recorded. Roots were dried at 60 °C to a constant weight for dry weight (DW) determination, ground to pass through a 40-mesh sieve, and subjected to Soxhlet extraction (ethanol, 80 °C, 30 min) following the Chinese Pharmacopeia (2015). The extract was filtered, adjusted to 25 mL with ethanol, and analyzed via HPLC (Shimadzu LC-20AD; C18 column: 217 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; mobile phase: acetonitrile/H₂O gradient; flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; detection wavelength: 203 nm). Polyphyllins quantification were performed using standard curves and LC-MS/TOF-MS fragment analysis. Biomass and polyphyllins content of P. polyphylla were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test for multiple comparisons, with statistical significance set at p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively (SPSS v27).

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

P. polyphylla root tissues (n = 6 per group: FP (P. palleroniana P6-treated) and FC (control)) were homogenized with liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using the OMEGA Plant RNA Kit. The concentration and purity of the proposed RNA were detected using Nanodrop2000. RNA integrity was verified (RIN > 8.0) via Agilent 2100. Oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads were used to isolate mRNA from total RNA through A-T base pairing with polyA tails. mRNA was randomly fragmented by incubation with fragmentation buffer. Fragments of ~ 300 bp were selected using magnetic bead-based size selection. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from fragmented mRNA using reverse transcriptase. Second-strand cDNA was generated to form stable double-stranded DNA. Adapters were ligated to the cDNA fragments. The final library was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Majorbio, Shanghai). Raw reads were filtered using Fastp (v0.23.2) to remove adapters, low-quality bases (Q < 20), and reads with > 10% N content. Clean reads were aligned to the P. polyphylla reference transcriptome using HISAT2 (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml). Transcript assembly and quantification were performed with StringTie (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/). Gene expression levels were normalized to FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DESeq2 (v1.24.0) with thresholds of |log₂FC| >1 and adjusted p < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). The ggplot2 package in R (v4.2.2) was used to generate volcano plots. Functional annotation of DEGs was performed via alignment against NR (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), eggnog (http://eggnogdb.embl.de), SwissProt (http://www.uniprot.org/), PFAM (http://pfam.xfam.org/), GO (http://www.geneontology.org), and KEGG (www.genome.jp/kegg) databases [34].

Results

Isolation and identification of PGPB

A total of 25 functional bacteria strains were isolated and screened using three unique selective media. Among them, twelve strains exhibited inorganic phosphorus-dissolving ability and were named P1 to P12; seven strains showed potassium-solubilizing ability and were named K1 to K7; six strains had nitrogen-fixing abilities and were named N1 to N6. The 16 S rRNA gene sequences of each strain were analyzed using the NCBI database, and phylogenetic relationships were determined using MEGA XI software (Fig. S1). The phylogenetic tree revealed that the seven strains (P6, P10, P11, K5, K6, N4, and N5) with different functions belong to Pseudomonas, while the five strains (P5, P7, K1, K2, and N1) were classified under Bacillus. The 16 S rRNA gene sequences of all strains have been uploaded to in GenBank (Accession: PV682596-PV682620).

Both Pseudomonas and Bacillus included strains capable of inorganic phosphorus-dissolving, potassium-solubilizing, and nitrogen-fixing suggesting that some isolates might possess multiple functions simultaneously. To verify this, all strains were inoculated onto inorganic phosphorus medium, dissolved potassium medium, and Ashby’s nitrogen-free medium. Colony size and solubilization halos (for phosphorus or potassium) were observed on each medium. The results showed that, except for K7 (Delftia acidovorans), all the other potassium-solubilizing strains also exhibited inorganic phosphorus-dissolving ability. Among the six strains screened on Ashby’s nitrogen-free medium, two Pseudomonas strains (N4 and N5) demonstrated all three functions (inorganic phosphorus-dissolving, potassium-solubilizing, and nitrogen-fixing), while the remaining strains only had nitrogen-fixing function. Notably, Pseudomonas N5 grew faster on Ashby’s nitrogen-free medium than Pseudomonas N4. Pseudomonas P6 exhibited the fastest growth on both inorganic phosphorus and dissolved potassium medium but lacked nitrogen-fixing function (Table 1). Pseudomonas N5 and P6 were identified as the most promising multifunctional strains for potential applications.

Table 1.

The growth of the strains on different medium

| Strain number | Nitrogen-fixing | Inorganic phosphorus-dissolving | Potassium-solubilizing |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | ++ | - | - |

| N2 | + | - | - |

| N3 | ++ | - | - |

| N4 | + | + | + |

| N5 | +++ | + | + |

| N6 | ++ | - | - |

| K1 | - | + | ++ |

| K2 | - | + | ++ |

| K3 | - | + | + |

| K4 | - | + | + |

| K5 | - | ++ | ++ |

| K6 | - | + | + |

| K7 | - | - | + |

| P1 | - | + | - |

| P2 | - | + | + |

| P3 | - | + | - |

| P4 | - | ++ | - |

| P5 | - | ++ | ++ |

| P6 | - | +++ | +++ |

| P7 | - | ++ | + |

| P8 | - | + | - |

| P9 | - | + | - |

| P10 | - | ++ | ++ |

| P11 | - | ++ | ++ |

| P12 | - | + | - |

“-” indicates no growth

“+” indicates a diameter < 2 cm

“++” indicates a diameter between 2 and 4 cm, and

“+++” indicates a diameter > 4 cmundefined

Screening of optimal PGPB - Pseudomonas sp. P6

The plant growth-promoting effects of two bacterial strains (Pseudomonas sp. N5 and P6) were evaluated using herbage seeds. After 15 days of germination, differences in growth parameters were observed between the treatment and control groups. The average plant height of the control group was 12.32 cm, while the N5- and P6-treated groups reached 13.16 cm and 14.36 cm, respectively, representing increases of 6.82% and 16.56%. The average root length of the control group was 4.72 cm, whereas the N5 and P6 groups exhibited root lengths of 7.53 cm (+ 59.53%) and 6.75 cm (+ 43.01%), respectively. The average number of roots per plant in the control group was 1.17 roots, while the P6-treated group showed a 44.44% increase (1.69 roots). In contrast, N5-treated group resulted in only a marginal increase (1.22 roots, + 4.10%) (Table 2; Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that Pseudomonas sp. P6 enhanced plant height, root length and number of roots per plant. whereas Pseudomonas sp. N5 primarily promoted root length with limited effects on other growth parameters. Thus, P6 exhibits superior potential for growth-promoting applications. Furthermore, the Salkowski reagent test confirmed IAA production by strain P6. The P6-inoculated culture medium turned red, while the uninoculated control and sterile water remained unchanged. Absorbance measurements (OD530) further verified higher IAA levels in the P6-treated medium compared to the control (Table 3). Comparing the two groups inoculated with Pseudomonas sp. P6, it was found that the higher content of IAA detected in the group supplemented with L-tryptophan. This may be due to L-tryptophan being an important precursor for IAA synthesis, and its addition is beneficial for IAA synthesis. The results indicate that strain P6 has the ability to synthesize the growth-promoting substance IAA.

Table 2.

Statistics on the growth of herbage (n = 10)

| Treatment | Average plant height | Average root length | Average number of roots per plant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value/cm | growth rate/% | Value/cm | growth rate/% | Value/cm | growth rate/% | |

| Control group | 12.32 ± 0.68 | - | 4.72 ± 0.93 | - | 1.17 ± 0.06 | - |

| P6 | 14.36 ± 0.48 | 16.56 | 6.75 ± 1.51 | 43.01 | 1.69 ± 0.25 | 44.44 |

| N5 | 13.16 ± 0.35 | 6.82 | 7.53 ± 0.65 | 59.53 | 1.22 ± 0.18 | 4.10 |

Fig. 1.

Effects of inoculant on herbage (n = 10). a The growth status of herbage on the 1 st, 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 14th, and 15th days after germination. b T1: Treated with P6 bacterial agent; T2: Treated with N5 bacterial agent; CK: Treated with sterile water

Table 3.

Absorbance of culture solution after color reaction (n = 3)

| Group | OD530 |

|---|---|

| Sterile water | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| King’s B broth without added L-tryptophan | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| King’s B broth supplemented with L-tryptophan | 0.08 ± 0.00 |

| King’s B broth without added L-tryptophan and inoculated with P6 | 0.46 ± 0.04 |

| King’s B broth supplemented with L-tryptophan and inoculated with P6 | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

Genomic assembly, prediction and functional gene annotation statistics

Following rigorous quality filtering, high-quality genome sequencing data and assembly results were obtained (Tables S1 and S2). The assembled genome of Pseudomonas sp. P6 was 6,558,226 bp, comprising both circular chromosome sequences (5,620,052 bp) and plasmid sequences (938,174 bp). The GC content of the chromosome sequence was 60.45%, and that of the plasmid was 59.88%. A total of 5753 and 818 protein-coding genes on the chromosome and plasmid of strain P6, respectively. Eight housekeeping genes, three prophages, eight genomic islands, and two CRISPR genes were annotated on the chromosome, with no corresponding genes predicted on the plasmid. The complete genome sequence of the assembled P6 has been uploaded to the NCBI database under project number PRJNA955924. The 16 s rRNA sequence similarity between strain P6 and Pseudomonas palleroniana strain MAB3 was 100%. The average nucleotide identity (ANI) and tetra nucleotide analysis (TNA) results of P6 and Pseudomonas palleroniana strain MAB3 were 98.68% and 99.96%, respectively, indicating that P6 was Pseudomonas palleroniana. Thus, it was named Pseudomonas palleroniana P6 (P. palleroniana P6).

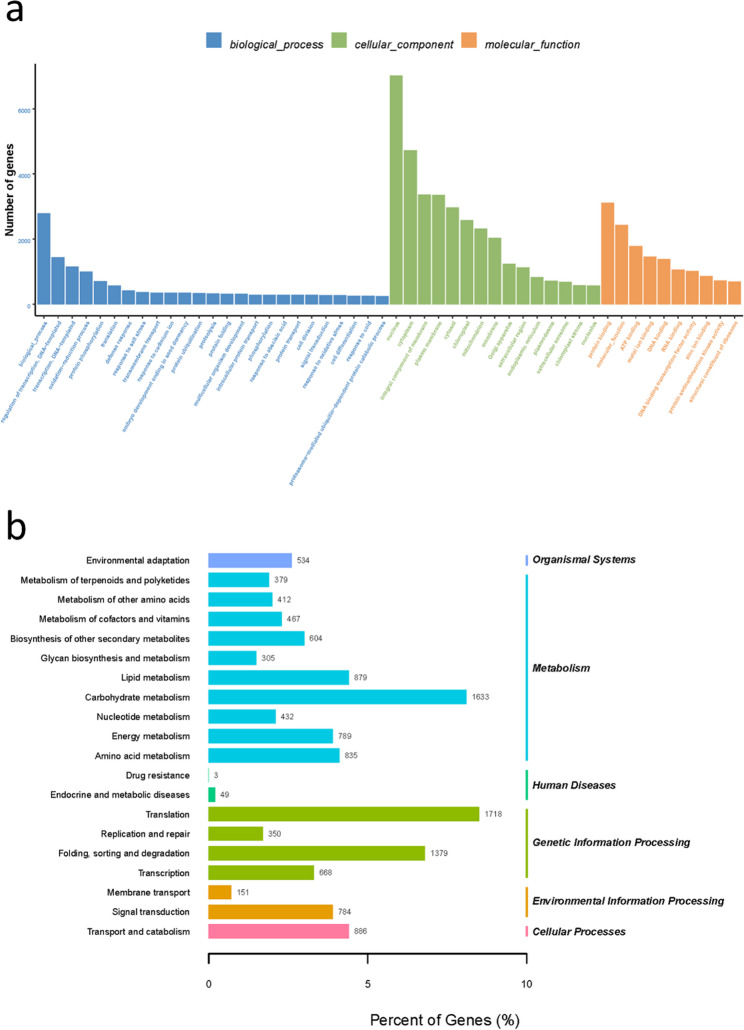

Annotation statistics revealed in Table S3. The annotation rate of strain P6 in the NR database reaches 99.65%. Functional annotations in Pfam, SwissProt, and COG databases all account for over 75%. The proportion of annotated genes in the KEGG database was only 58.04%. Gene annotation effectively displays the functional information of strains. GO annotations show that the most annotated genes were integral components of the membrane, plasma membrane, cytoplasm, DNA binding, and ATP binding, all of which belong to the categories of cellular components and molecular functions (Fig. 2a). The annotation circle diagram of the whole genome COG was depicted in Fig. S2.

Fig. 2.

(a) GO annotation of Pseudomonas sp. P6 genome. (b) Siderophore synthesis gene cluster in P. palleroniana P6 genome

Metabolic pathways related to growth promotion of P. palleroniana P6

Microbial dissolution of phosphorus in soil was primarily achieved through the production of organic acids, inorganic acids, H2S, extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), and some indirect effects. There has been limited genetic research on phosphate dissolution. Only a few genes have been identified to control the role of phosphate dissolution, mainly non-specific acid phosphatase (acid phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase), phytase, and carbon phosphorus (C-P) lyase [35]. In the genome of P6, genes encoding phosphatase containing: phoB, phoD, and phoU, as well as genes indirectly promoting phosphorus dissolution such as eno, gcd, ppc, and pqq series (B, C, D, and E), have been annotated (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genes associated with phosphorus solubilization annotated in P. palleroniana P6

| Genes | Gene function | Gene position |

|---|---|---|

| eno [44] | Encoding enolase | 1,460,519~1,459,230− |

| gcd [35] | Encoding glucose dehydrogenase | 1,254,114~1,251,697− |

| phoB [70] | Encoding alkaline phosphatase B | 5,497,217~5,497,906+ |

| phoD [71] | Encoding alkaline phosphatase D | 958,992~60,533+, 2,313,315~2,314,889+ |

| phoU [72] | Encoding phosphorus transporter protein | 5,502,932~5,502,171− |

| ppc [67] | Encoding phosphopentose carboxylase | 1,401,697~1,404,324+, 4,568,486~4,565,799− |

| pqqB [73] | Encoding pyrroloquinoline quinine | 224,894~225,805*+ |

| pqqC [74] | Encoding pyrroloquinoline quinine | 225,926~226,663*+ |

| pqqD [75] | Encoding pyrroloquinoline quinine | 226,660~226,935*+ |

| pqqE [76] | Encoding pyrroloquinoline quinine | 226,928~228,058*+ |

The “*” behind the gene position indicates that the gene is on the plasmid

The gene position column is from start to end, where start < end represents the sense strand (marked with “+”), and start > end represents the antisense strand (marked with “−”)

The analysis of secondary metabolite synthesis gene clusters (Fig. 2b) reveals a siderophores synthesis gene cluster totaling 11,929 bp in length in the genome of P6, located on the chromosome from 4,778,667 to 4,790,596, including genes such as purM (AIR synthesis), purN (formyltransferase), sbnD (MFS transporter), and mazG (nucleoside triphosphate pyrolase). Similarly, genome analysis (Table 5) also uncovers the presence of genes involved in IAA biosynthesis in P6. The trp (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G) and spe (A and C) genes in the IAA biosynthesis pathway have been found in both chromosome and plasmid DNA [36], forming a complete pathway for tryptophan and IAA synthesis.

Table 5.

Genes involved in indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) synthesis

| Pathway | Gene ID | Name | Location | Annotation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAA synthesis | gene0064 | speA | 761,414~763,327+ | Arginine decarboxylase |

| gene0848 | speC | 968,517~967,354− | Proline decarboxylase | |

| gene 0048 | trpA | 53,792~52,983− | Tryptophan synthase | |

| gene 0049 | trpB | 55,033~53,792− | Tryptophan synthase | |

| gene 0232 | trpG | 281,056~280,472− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 0233 | trpE | 282,456~281,053− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 3961 | trpF | 4,493,353~4,492,721− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 0166 | trpC | 174,215~173,379*− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 0167 | trpD | 175,261~174,212*− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 0168 | trpG | 175,864~175,271*− | Indolegate synthase | |

| gene 0170 | trpE | 179,823~178,342*− | Indolepyruvate synthetase | |

| gene 2760 | aldA | 3,156,441~3,157,865+ | Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 3794 | aldB | 4,317,662~4,316,142− | Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 0035 | aldB | 33,861~35,381*+ | Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 1886 | aldH | 2,071,370~2,072,956+ | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 1958 | aldH | 2,147,151~2,148,728+ | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 2327 | aldH | 2,653,725~2,655,305+ | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 3215 | aldH | 3,661,588~3,663,159+ | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| gene 0101 | amiD | 103,048~103,824+ | Acyltransferases | |

| gene 1390 | amiE | 1,567,156~1,568,598+ | N-acetylated amide synthetase | |

| gene 2491 | amiE | 2,836,505~2,837,539+ | N-acetylated amide synthetase | |

| gene 3290 | amiE | 3,746,372~3,748,078+ | N-acetylated amide synthetase | |

| gene 3500 | amiE | 3,882,562~3,984,076+ | N-acetylated amide synthetase | |

| gene 4542 | amiE | 5,127,932~5,126,415− | N-acetylated amide synthetase | |

| gene 0543 | miaA | 639,908~640,879+ | Isoprenoyl CoA synthase | |

| gene 0834 | miaB | 933,738~935,066*+ | 5-Methylisoprenoic acid carboxylase | |

| gene 3318 | miaE | 3,777,366~3,776,764− | N6-acetyllysine transferase |

The “*” behind the gene position indicates that the gene is on the plasmid

The gene location column is from start to end, where start < end represents the sense strand (marked with “+”), and start > end represents the antisense strand (marked with “−”)

Field experiments

Effect of P. palleroniana P6 on soil physicochemical properties

Soil physicochemical parameters before and after application of P. palleroniana P6 were presented in Table 6 (p < 0.05). Significant pH changes were observed during both sampling periods. In control group without bacterial agents, pH decreased from 6.10 (OC) to 5.83 (FC). For treatment group, pH dropped from 6.14 (OP) to 5.50 (FP), which was 0.33 pH units lower than control group. Available phosphorus (AP) in FP group did not show a significant decrease, whereas AP in FC group decreased from 0.17 g/kg to 0.14 g/kg. Available potassium (AK) in FP groups increased from 0.24 g/kg to 0.26 g/kg, while AK in FC groups significantly decreased from 0.24 g/kg to 0.20 g/kg. With the growth of P. polyphylla, pH, total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), water-soluble nitrogen (WSN), total phosphorus (TP), total potassium (TK), AP, and AK content all significantly decreased. However, AP and AK in FP group treated with bacterial agents didn’t exhibit a downward trend, and even AK significantly increased. Compared to FC group without bacterial agents, FP group treated with P. palleroniana P6 significantly reduced soil pH and increased AK.

Table 6.

Soil physicochemical propertie

| Items | OC | OP | FC | FP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (H2O) | 6.10 ± 0.09a | 6.14 ± 0.02a | 5.83 ± 0.16b | 5.50 ± 0.12c |

| TOC (g/kg) | 73.90 ± 2.17a | 74.71 ± 2.35a | 69.46 ± 1.05b | 69.74 ± 1.72b |

| TN (g/kg) | 2.79 ± 0.19a | 2.72 ± 0.17a | 2.40 ± 0.29b | 2.39 ± 0.16b |

| WSN (g/kg) | 0.28 ± 0.02a | 0.28 ± 0.01a | 0.21 ± 0.00b | 0.21 ± 0.01b |

| TP (g/kg) | 0.75 ± 0.04a | 0.74 ± 0.03a | 0.71 ± 0.03b | 0.70 ± 0.03b |

| AP (g/kg) | 0.17 ± 0.00a | 0.17 ± 0.01a | 0.14 ± 0.02b | 0.17 ± 0.02a |

| TK (g/kg) | 12.74 ± 0.24a | 12.51 ± 0.36a | 11.58 ± 0.86b | 11.39 ± 0.63b |

| AK (g/kg) | 0.24 ± 0.00b | 0.24 ± 0.01b | 0.20 ± 0.01c | 0.26 ± 0.02a |

Different letters within the same line show significant differences (n = 30, P < 0.05)

Effect of P. palleroniana P6 on biomass and polyphyllins content of P. polyphylla root

Dry and fresh weights of 60 root tubers from both the treatment group (FP) and the control group (FC) were measured (Fig. 3). P. palleroniana P6 application significantly increased fresh and dry weights of P. polyphylla roots (p < 0.001). Average fresh weight in FC group’s tubers was 2.06 g, while average fresh weight in FP group’s tubers reached 2.54 g, marking an average increase of 0.48 g (23.30%) per tuber. Average dry weight of tubers in FC group was 0.76 g, while average dry weight of tubers in FP group reached 0.93 g, with an average growth rate of 22.37% per tuber.

Fig. 3.

Fresh (FW) (a) and dry weight (DW) (b) of P. polyphylla root (n = 30, ***indicates p < 0.001)

Polyphyllins content in P. polyphylla’s roots were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Fig. S3, Table 7). In November, the highest content was polyphyllin II, followed by polyphyllin VII and I. Polyphyllin VI and diosgenin content was very low. The average content of polyphyllin II, VII, and I in the treatment group (FP) reached 30.38 mg/g, 4.89 mg/g, and 4.46 mg/g, respectively, while the average content of polyphyllin II, VII and I in the control group (FC) was 26.63 mg/g, 2.94 mg/g, and 3.41 mg/g, respectively. P. palleroniana P6 application significantly increased the content of polyphyllin II, VII, and I in P. polyphylla by 14.08%, 66.33%, and 30.79%, respectively (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the treatment and control groups in the lower content of polyphyllin VI and diosgenin from P. polyphylla.

Table 7.

Polyphyllins content in the roots of P. polyphylla

| Polyphyllins | FP (mg/g) | FC (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| II | 30.38 ± 1.93a | 26.63 ± 1.42b |

| VII | 4.89 ± 0.46a | 2.94 ± 0.39b |

| I | 4.46 ± 0.21a | 3.41 ± 0.64b |

| VI | 0.02 ± 0.01a | 0.02 ± 0.01a |

| N | 0.01 ± 0.01a | 0.02 ± 0.01a |

VII, VI, II, I and N represent polyphyllin VII, VI, II, I and diosgenin, respectively

Different letters indicate a significant difference determined by the Turkey test (n = 30, p < 0.05)

Effect of P. palleroniana P6 on the transcriptome of P. polyphylla

Following quality control and filtering, a total of 79.95 Gb of high-quality RNA sequences were obtained, with an average GC content of 51.33%. The average Q20 and Q30 reached 97.89% and 93.58%, respectively (Table S4). The raw transcriptome data of Paris polyphylla root has been uploaded to NCBI database under project number PRJNA1266360. De novo assembly using Trinity yielded 168,489 transcriptome sequences, which were clustered into 65,257 unigenes using Corset. Functional annotation was performed by comparing unigene clustering with six major databases: NR, eggNOG, SwissProt PFAM, GO, and KEGG (Table S5). A total of 32,017 unigenes were annotated in the six major databases, accounting for only 49.06%. All unigenes had the highest degree of annotation in the eggNOG database, reaching 45.96%, while the annotation ratio in the KEGG database was only 30.93%. Over 50% of unigenes (33,240) have not been annotated with precise functionality, which may indicate inherent limitations in the functional characteristics of a large number of single genes.

The classification results of GO function, as shown in Fig. 4a, indicated that 40.47% of unigenes were annotated into 15 cellular components, 10 molecular functions, and 25 biological processes, with over 4000 unigenes annotated into cellular components (nucleus and chloroplast). The functional classification results of KEGG, as shown in Fig. 4b, indicate that 20,184 unigenes were annotated into six major categories and 20 subcategories. Among them, genes belonging to metabolism and genetic information processing have the highest number, with 379 unigenes annotated in metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides.

Fig. 4.

Functional annotation and classification of unigenes. a GO classification, b KEGG classification

The transcriptional differences of genes in the roots of P. polyphylla between the FP and FC groups were shown in Fig. 5. The horizontal axis represents the logarithm of the multiple changes in gene expression differences between the two groups of samples, and the vertical axis represents the logarithm of the statistical test values for gene expression differences. The higher the value, the more significant the expression difference. Each point in the graph represents a specific gene, with a corrected threshold of p < 0.05. Red represents significantly upregulated genes, green represents significantly downregulated genes, and gray dots represent non significantly differentially expressed genes. Compared with the FC group, the FP group had a total of 521 differentially expressed genes, including 371 upregulated genes and 150 downregulated genes.

Fig. 5.

DEGs filtering. Differential expression was analyzed using DESeq2, with |log₂FC| >1 and adjusted p < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). a Histogram of DEGs, b Volcano plot of DEGs. Red dots represent significantly up-regulated unigenes, green dots represent significantly down-regulated unigenes, and gray dots unigenes with no significant difference

By analyzing the upregulated GO enrichment entries and KEGG enrichment pathways, we further investigated which genes in P. polyphylla’s roots were significantly affected by the application of P. palleroniana P6. The top 20 GO functions and KEGG metabolic pathways with the highest upregulation of expression between the FP and FC groups were plotted according to the enrichment analysis results (Fig. 6). The GO functional enrichment analysis results showed that differentially expressed genes significantly upregulated functions related to cholesterol synthesis and metabolism, such as reverse cholesterol transport (GO: 0043691), Cholesterol homeostasis (GO: 0042632), cholesterol binding (GO: 0015485), cholesterol biosynthetic process (GO: 0006695), and positive regulation of cholesterol esterification (GO: 0010873)”. Cholesterol has been proven to be an important precursor for the synthesis of various steroid saponins, including polyphyllins from P. polyphylla [37, 38]. Positive regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity (GO:0051006), lipoprotein metabolic process (GO: 0042157), high-density lipoprotein particle assembly (GO: 0034380) and high-density lipoprotein particle (GO: 0034364), among other functions related to lipoprotein assembly and metabolism, were also significantly upregulated in the FP group. Although there were no functions such as high-density lipoprotein particle in plants. Through annotations from other databases, it was found that they were annotated as apolipoprotein in SwissProt and eggNOG. In addition, functions such as triglyceride homeostasis (GO: 0070328), triglyceride catabolic process (GO: 0019433) and flavonoid biosynthetic process (GO: 0009813) showed a significant enrichment trend in the FP group.

Fig. 6.

(a) The enriched GO terms of up-regulated DEGs; (b) The enriched KEGG pathways of up-regulated DEGs. The rich factor represents the ratio of the number of differentially expressed genes to the total annotated genes in the pathway, and the larger the enrichment factor, the higher the enrichment degree

The KEGG metabolic pathway enrichment analysis results showed that terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (ko00900), phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940), plant-pathogen interaction (ko04626), plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075), pentose phosphate pathway (ko00030), oxidative phosphorylation (ko00190), histidine metabolism (ko00340), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ko00010), flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (ko00944), beta-alanine metabolism (ko00440), arginine and proline metabolism (ko00330), and circadian rhythm plant (ko04712) were significantly upregulated in the FP group. Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis is an important component of the plant terpenoid compound synthesis pathway (saponins synthesis pathway). The pathways of pentose phosphate pathway (ko00030), oxidative phosphorylation (ko00190) and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ko00010) were the main sources of energy for organisms. The enrichment of these pathways indicates P. palleroniana P6 application makes the growth and metabolism of P. polyphylla more active. The genes of oxidosqualene cyclase (SQE), squalene monooxygenase (SQLE), and cycloartenol synthase (CAS) in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathway, and the genes of auxin-responsive protein in plant hormone signal transduction pathway were further analyzed (Table S6). Among the DEGs involved in steroidal saponin biosynthesis, such as SQE, SQLE, and CAS, only one gene was downregulated, while six genes were upregulated. The fold-change magnitude (log₂FC) of the key DEGs, SQLE (Squalene monooxygenase) and CAS (exportin-2 isoform X1, CASQ1), both exceeded 0.9000. There are seven DEGs of auxin-responsive protein, accounting for 23.3% of the total number of genes annotated in the transcriptome. Among them, six genes showed upregulated differential expression, with the fold-change magnitude (log₂FC) of auxin transport protein BIG reached a maximum of 1.0022.

Discussion

The exploration of the growth promoting ability of P. palleroniana P6

Microorganisms capable of dissolving inorganic phosphorus, solubilizing potassium, and fixing nitrogen were identified, which mainly belong to the genera Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Rhizobium, and Delftia. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the Pseudomonas and Bacillus species possess the ability to dissolve inorganic phosphorus, solubilize potassium, fix nitrogen, and to some extent promote growth. For example, Yadav et al. reported that certain Pseudomonas and Bacillus can fix nitrogen, dissolve inorganic phosphorus, solubilize potassium, and promote the growth of Amaranthus hypochondrius L. and Hordeum vulgare L [39, 40]. Guo et al. identified over ten Bacillus strains with similar capabilities, among which a tri-strain consortium significantly promoted Kiwifruit growth [41]. Jorquera et al. confirmed that Bacillus and Leifsonia have nitrogenase genes and strong nitrogen-fixing efficiency [42]. Comparative analysis of dissolution zones and colony diameters on selective media revealed that most inorganic phosphorus-dissolving strains also possess potassium-solubilizing capabilities. Notably, Pseudomonas sp. N4 and Pseudomonas sp. N5 exhibited all three functions simultaneously, but Pseudomonas sp. N5 had a higher nitrogen-fixing efficiency than Pseudomonas sp. N4. Furthermore, Pseudomonas sp. P6 showed superior growth rates in inorganic phosphorus and dissolved potassium medium, suggesting higher phosphorus-dissolving and potassium-solubilizing efficiencies. The growth promotion experiments of Pseudomonas sp. P6 and Pseudomonas sp. N5 showed that they can both promote herbage growth. Pseudomonas sp. P6 had a positive effect on plant height and root length and increased the number of roots per plantlet. The impact of Pseudomonas sp. N5 on herbage root length was better than that of Pseudomonas sp. P6, yet its promotion of plant height and number of roots per herbage was less significant. Thus, Pseudomonas sp. P6 was selected for whole genome analysis to elucidate its growth promoting mechanism.

Many genes related to the phosphorus-dissolving function of microorganisms have been annotated in the P. palleroniana P6 genome, such as genes phoB, phoD, and phoU encoding acidic phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase, which can directly hydrolyze organic phosphorus in soil [43]. The gcd and eno genes can mediate the production of acidic substances by microorganisms, thereby reducing soil pH and promoting the dissolution of soil phosphate [44]. The genes encoding pyrroloquinoline quinine (pqq series) were located on the P. palleroniana P6 plasmid. The encoded pyrroloquinoline quinine was a small redox active molecule and a cofactor of glucose dehydrogenase, which can catalyze the conversion of glucose to gluconic acid. Gluconic acid was the main organic acid produced by phosphorus-dissolving bacteria and can be used to dissolve inorganic phosphorus in soil [45]. However, research generally suggests that organic and inorganic acids produced by microorganisms can lower soil pH and chelate potassium ions, thereby promoting the release and solubility of soil potassium ions [46]. Therefore, the dissolution of K-feldspar (K2O·Al2O3·6SiO2) by P. palleroniana P6 should be attributed to the action of the generated organic acids. Previous studies have shown that IAA can promote plant root the growth and biomass accumulation [47], and siderophores produced by microorganisms are considered important factors in promoting bacterial growth in plants [48, 49]. The completion pathways of tryptophan synthesis and IAA synthesis were annotated in the genome of P. palleroniana P6. The color reaction and absorbance changes in the culture medium of P. palleroniana P6 also confirmed that it can synthesize IAA. This one of the reasons why the root system of herbage grows vigorously and has a higher number of roots after the application of P. palleroniana P6 bacterial agent.

The effects of P. palleroniana P6 on the root system of P. polyphylla

After nine months of P. polyphylla cultivation with microbial agent application, soil nutrient content and pH value were altered. Soil pH decreased markedly, with a greater reduction observed in the FP group compared to the FC group. The roles of rhizosphere microorganisms and root exudates during the planting process of P. polyphylla are the key reasons for the decrease in soil pH [50]. Meanwhile, P. Palleroniana P6 can synthesize organic acids through the eno, gcd, and pqq series genes, which also be the main reason for the greater decrease in soil pH in the FP group. Soil nutrient levels (excluding AK and AP) declined in both FP and OP groups relative to untreated controls (FC and OC). The growth of P. polyphylla, microbial metabolism, and nutrient loss are usually the main reasons for the changes in soil nutrients before and after planting [51]. In the FP group, the content of AP and AK did not decrease, and even the content of AK increased. This may be due to the potassium solubilizing effect of applying P. palleroniana P6, which increases the content of AK. However, P6, which originally had the ability to dissolve phosphorus, only maintained AP at the initial level here. This may be because P6 does not have nitrogen fixation function, while phosphorus solubilizers are limited by carbon and nitrogen sources in the soil environment [52].

Nutrients availability and adequatly (N, P, K) is crucial for plants growth and secondary metabolites synthesis [53]. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilization is well-documented to enhance P. polyphylla growth and root biomass accumulation [54]. In this study, P. palleroniana P6 application significantly increased P. polyphylla fresh and dry weights, driven by elevated soil AK, IAA, and siderophore levels. The substances such as IAA and siderophores produced by P. palleroniana P6 can also promote the growth and development of P. polyphylla roots [55, 56]. Upregulation of the expression of the “auxin receptor protein” gene in the KEGG pathway (ko04075) was found in the roots of P. polyphylla in the FP group, and all the upregulated DEGs were “auxin transport protein BIG”. BIG is a large membrane-associated protein gene required for normal auxin transport, participating in regulating polar auxin transport [57]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, BIG is crucial for various developmental and physiological processes, such as regulating light-shadow responses, circadian rhythms, gibberellin status, and root and shoot development [58]. The upregulation of auxin transport genes in P. polyphylla roots induced by P. palleroniana P6 application may facilitate the transport of growth hormones produced by P. palleroniana P6 into P. polyphylla, thereby promoting root growth and development. Comprehensive analyses of field and laboratory treatment results show that P. palleroniana P6 can promote plant growth through phosphorus and potassium solubilization, as well as production of IAA and siderophores.

Soil nutrient content is the key factor affecting the polyphyllins content and growth of P. polyphylla, especially elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium [59]. The increase of AK in the soil by P. palleroniana P6 application also increases the polyphyllins content in the roots of P. polyphylla [38]. Shu et al. identified Pseudomonas and Bacillus as dominant endophytic bacteria in the roots of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, which showed significant positive correlations with polyphyllin I, II, and VII content, respectively, suggesting their potential as candidate strains for bioactive compound production [20]. Zhao et al. demonstrated that inoculation with three potassium-solubilizing bacteria (KSB) (Bacillus thuringiensis, B. polymyxa, and Paenibacillus amylolyticus) can effectively increase the content of Pseudo-protodiosgenin and diosgenin H [18]. These findings are consistent with Li et al.‘s study, which revealed that phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (B. mycoides, B. wiedmannii, and B. proteolyticus) promoted polyphyllins accumulation (including pseudoprotodioscin, polyphyllin VII, II, and I) by improving soil nutrient structure [17]. In our study, inoculation with P. palleroniana P6 significantly enhanced the content of major polyphyllins components (polyphyllin II, VII, and I) in P. polyphylla roots, with polyphyllin VII showing the most pronounced increase of 66.33%. Numerous studies have confirmed that endophytic bacteria can increase polyphyllins production in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis by regulating the expression of related biosynthetic genes [60, 61]. Notably, Bacillus cereus LgD2 was found to promote polyphyllins accumulation by regulating key downstream genes in biosynthetic pathways [60]. Perhaps this phenomenon also exists in P. polyphylla after the application of P. palleroniana P6.

The gene enrichment analysis of the transcriptome GO upregulation in the FP group showed that the application of the bacterial agent promoted the expression of genes related to cholesterol synthesis and metabolism in the roots of P. polyphylla. Cholesterol is one of the important precursors in the biosynthesis pathway of P. polyphylla polyphyllins, and its synthesis and metabolism were essential biochemical reactions in the biosynthesis pathway of polyphyllins [62]. The biosynthetic pathway begins with the condensation of two molecules of isopentenyl diphosphate and one molecule of diphosphate (FPP, C15). Two FPP molecules are catalyzed by squalene synthase (SQS) to produce the linear C30 molecule, squalene, which is further catalyzed by squalene epoxidase to form 2,3-oxidosqualene. Then, 2,3-oxidosqualene is cyclized by a cycloartenol synthase (CAS) to form cycloartenol, which is then modified by a series of oxidation and reduction reactions to form cholesterol [62]. The cholesterol backbone is further modified by successive oxygenation with cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases (P450s) to form sapogenins [63]. Upregulation of the SQE and SQLE gene enhances the production of 2,3-oxidized squalene, which is an important precursor of polyphyllins and can promote its synthesis to a certain extent. Polyphyllin I and VII have the highest correlation with upstream genes containing relatively abundant sterol synthesis, and these genes are likely to play a key role in the biosynthesis of polyphyllins [64]. The upregulation of the CAS gene is closely related to the increase of polyphyllin I and VII [62]. The application of P. palleroniana P6 may promote polyphyllins synthesis by upregulating SQE, SQLE, and CAS genes in the terpenoid backbone biosynthesis. The conversion of squalene to 2,3-oxidosqualene (squalene epoxide) catalyzed by squalene monooxygenase/cyclooxygenase requires a large amount of NADPH and ATP [64]. The application of P. palleroniana P6 upregulates energy metabolism (glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation) related genes in the roots of P. polyphylla, suggesting that it enhances metabolic activity and energy expenditure.

The effective use of eco-friendly PGPR can reliably promote plant growth and host immune regulation. PGPR protect plants from pathogen invasion through the following mechanisms: (i) intercellular and interkingdom communication, (ii) quorum quenching of pathogen signaling molecules, (iii) production of antibacterial secondary metabolites, (iv) activation of plant stress-resistance related gene expression, and (v) immunomodulation of the host’s systemic immune response by (a) systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and/or by (b) induced systemic resistance (ISR) [65]. The induction of beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere that promote plant growth belongs to ISR, which triggers plant activation through various mechanisms similar to vaccination, leading to a physiological condition that enables plants to activate defense responses in local and systemic tissues. It protects uninfected or unexposed parts, thereby enhancing resistance to subsequent pathogen attacks [66]. Polyphyllins, as a common plant defense compound, are used to resist the invasion of pathogens such as fungi [67]. After receiving signals of pathogen infection, plants secrete antibacterial compounds that kill pathogen cells [68]. Inoculation with PGPB P6 is highly likely to activate ISR in P. polyphylla roots. This shares some signaling components with the pathways activated during pathogenic attacks, leading to upregulated expression of “plant-pathogen interaction” genes in roots. This stimulates the defense system in P. polyphylla roots and triggering the synthesis of more polyphyllins in respond to the mutualistic relationship established with the plant.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully isolated multiple strains with the abilities of phosphorus dissolution, potassium solubilization, and nitrogen fixation through screening. The herbage seedling experiment demonstrated that Pseudomonas sp. P6 exhibited the most pronounced growth-promoting effect. Genomic analysis revealed that P. palleroniana P6 possesses the ability to dissolve phosphorus and potassium, synthesize IAA, and produce siderophores. Field experiment found that P. palleroniana P6 application significantly reduced soil pH, potentially increasing nutrient content (available potassium), IAA levels, and the amount of siderophores, thereby stimulating the growth and polyphyllins synthesis of P. polyphylla. Additionally, the enrichment of genes associated with plant hormone signal transduction and saponins synthesis pathways in the transcriptome further confirms the impact of P. palleroniana P6 on the growth and polyphyllins synthesis of P. polyphylla. P. palleroniana P6 shows promise as an excellent microbial agent that enhances soil fertility, promotes the growth and polyphyllins accumulation of P. polyphylla, without significantly altering the original soil microbial community [69]. Consequently, P. palleroniana P6 holds broad application prospects in the P. polyphylla cultivation industry.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Xueduan Liu conceived and supervised the project. Yili Liang, Shaodong Fu, Xinhong Wu, and Shihui Li designed this study. Shaodong Fu and Shihui Li performed the most of experiments. Xinhong Wu, Yan Deng, Luhua Jiang and Zhenchun Duan assisted with performance of the experiment. Xinhong Wu visualized the analysis and wrote the manuscript. Yili Liang, Shaodong Fu, and Yiran Li revised the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570113).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository under GnenBank (Accession numbers: PV682596-PV682620) and BioProject (Accession numbers: PRJNA955924 and PRJNA1266360).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shaodong Fu, Email: fsd1032725536@gmail.com.

Yili Liang, Email: liangyili6@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Xu Jie Q, Wei N, Chang Xiang C, et al. Seeing the light: shifting from wild rhizomes to extraction of active ingredients from above-ground parts of Paris polyphylla var. Yunnanensis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;224:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phurailatpam AK, Choudhury A, Yatung T, et al. A review on the importance of two edicinal plants of North East India: Paris polyphylla Smith and Kaempheria parviflora Wall. ex Baker. Annals of Phytomedicine: An International Journal. 2022;11(2):214–23.

- 3.Yu GD, Yan LZ, Ji Z, et al. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, and Pharmacological properties of Paris L. (Liliaceae): a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;278:114293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian XL, Liu JZ, Jiang LJ, et al. Efficient extraction and optimization procedures of polyphyllins from Paris polyphylla var chinensis by deep eutectic solvent coupled with ultrasonic-assisted extraction. Microchem J. 2024;196:109692.

- 5.Luo H, Xu Y, Sun DY, et al. Assessment of the inhibition risk of Paris saponins, bioactive compounds from Paris polyphylla, on CYP and UGT enzymes via cocktail inhibition assays. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2020.104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YZ, Si Y, Xiang YC, et al. Polyphyllin I activates AMPK to suppress the growth of non-small-cell lung cancer via induction of autophagy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020;687: 108285. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Pang DJ, Yang CC, Li C, et al. Polyphyllin II inhibits liver cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion through downregulated Cofilin activity and the AKT/NF-κB pathway. Biol Open. 2023;12(1):059765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JI, Lee HM, Park JH et al. Improvement of glucose metabolism by Pennogenin 3-O-β-Chacotrioside via activation of IRS/PI3K/Akt signaling and mitochondrial respiration in insulin-resistant hepatocytes. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2025; 69(9):e70010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Xu LH, Chen ZQ, Wang YB, et al. Polyphyllin VII as a potential drug for targeting stemness in hepatocellular cancer via STAT3 signaling. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2023;23(4):325–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kumar V, Sharma R, Sharma P et al. Developmental stage significantly affects in vitro propagation practices: a case study in Paris polyphylla smith, an important endangered medicinal plant of Himalayas. J Plant Growth Regul. 2025;44:3635–59.

- 11.Kunwar RM, Adhikari YP, Sharma HP, et al. Distribution, use, trade and conservation of Paris polyphylla sm. in Nepal. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2020. 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01081. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa S, Kabir S, Shabbir U, et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in sustainable agriculture: from theoretical to pragmatic approach. Symbiosis. 2019;78(2):115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CQ, Pei J, Li H, et al. Mechanisms on salt tolerant of Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 and its growth-promoting effects on maize seedlings under saline conditions. Microbiol Res. 2024. 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negi S, Daughton B, Carr CK, et al. Effect of plant growth-promoting molecules on improving biomass productivity in DISCOVR production strains. Algal Res. 2024;77: 103364.

- 15.Khalil A, Bramucci AR, Focardi A, et al. Widespread production of plant growth-promoting hormones among marine bacteria and their impacts on the growth of a marine diatom. Microbiome. 2024. 10.1186/s40168-024-01899-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur R, Soni R, Dhar H, et al. Enhancing saffron (Crocus sativus L.) growth in the Kashmir Valley with resilient and widely effective plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) under field conditions. Ind Crop Prod. 2024. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119475. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li ZW, Wang YH, Liu C, et al. Effects of organophosphate-degrading bacteria on the plant biomass, active medicinal components, and soil phosphorus levels of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Plants. 2023. 10.3390/plants12030631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao SX, Deng QS, Jiang CY et al. Inoculation with potassium solubilizing bacteria and its effect on the medicinal characteristics of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Agriculture-Basel. 2023; 13(1):21.

- 19.Fu SD, Deng Y, Zou K, et al. Dynamic variation of Paris polyphylla root-associated Microbiome assembly with planting years. Planta. 2023;257(3):04074–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu Q, Ruan L, Wu Y, et al. Diversity of endophytic bacteria in Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis and their correlation with polyphyllin content. BMC Microbiol. 2025. 10.1186/s12866-025-03814-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahid I, Han J, Hardie D, et al. Profiling of antimicrobial metabolites of plant growth promoting Pseudomonas spp. isolated from different plant hosts. 3 Biotech. 2021. 10.1007/s13205-020-02585-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Zou K, Fu SD, et al. Flavonoid synthesis by Deinococcus sp. 43 isolated from the Ginkgo rhizosphere. Microorganisms. 2023;11(7):1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wu XH, Zou K, Liu XD, et al. The novel distribution of intracellular and extracellular flavonoids produced by Aspergillus sp. Gbtc 2, an endophytic fungus from Ginkgo Biloba root. Front Microbiol. 2022;13: 972294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Neubert K, Zuchantke E, Leidenfrost RM, et al. Testing assembly strategies of Francisella tularensis genomes to infer an evolutionary conservation analysis of genomic structures. BMC Genomics. 2021. 10.1186/s12864-021-08115-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang KY, Gao YZ, Du MZ, et al. Vgas: a viral genome annotation system. Front Microbiol. 2019. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montaña S, Vilacoba E, Fernandez JS, et al. Genomic analysis of two Acinetobacter baumannii strains belonging to two different sequence types (ST172 and ST25). J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;23:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Richter M, Rosselló Móra R, Glöckner FO, et al. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(6):929–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, Zhang J, Liu XY, et al. De novo RNA-seq and annotation of sesquiterpenoid and ecdysteroid biosynthesis genes and MicroRNAs in a spider mite Eotetranychus kankitus. J Econ Entomol. 2021;114(6):2543–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Santos Pereira C, Sousa J, Costa, aMA, et al. Functional and sequence-based metagenomics to uncover carbohydrate-degrading enzymes from composting samples. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023;107(17):5379–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H, Owen D, Juge N. Structure and function of microbial ?-L-fucosidases: a mini review. Essays Biochem. 2023;67(3):399–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Blin K, Shaw S, Medema MH, et al. The antismash database version 4: additional genomes and bgcs, new sequence-based searches and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023. 10.1093/nar/gkad984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Backer R, Rokem JS, Ilangumaran G, et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front Plant Sci. 2018. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang T, Zheng BQ, Wang MG, et al. Spatial distribution, occurrence form, availability and ecological risk assessment of arsenic in soils of riparian zones on the Tibetan Plateau. Gondwana Res. 2024;130:131–9.

- 34.Xu P, Mi Q, Zhang X, et al. Dissection of transcriptome and metabolome insights into the polyphyllin biosynthesis in Paris. BMC Plant Biol. 2025. 10.1186/s12870-025-06219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasul M, Yasmin S, Suleman M, et al. Glucose dehydrogenase gene containing phosphobacteria for biofortification of phosphorus with growth promotion of rice. Microbiol Res. 2019;223:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Zhong J, Liu H, et al. Complete genome sequence of the drought resistance-promoting endophyte Klebsiella sp LTGPAF-6F. J Biotechnol. 2017;246:36–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Mohammadi M, Mashayekh T, Rashidi Monfared S, et al. New insights into Diosgenin biosynthesis pathway and its regulation in Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Phytochem Anal. 2020;31(2):229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin X, Liu J, Kou CX, et al. Deciphering the network of cholesterol biosynthesis in Paris polyphylla laid a base for efficient diosgenin production in plant chassis. Metab Eng. 2023;76:232–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Negi R, Kaur T, Devi R, et al. Assessment of nitrogen-fixing endophytic and mineral solubilizing rhizospheric bacteria as multifunctional microbial consortium for growth promotion of wheat and wild wheat relative Aegilops kotschyi. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Devi R, Kaur T, Kour D, et al. Microbial consortium of mineral solubilizing and nitrogen fixing bacteria for plant growth promotion of Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondrius L). Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2022;43: 102404.

- 41.Shen H, He XH, Liu YQ, et al. A complex inoculant of N2-fixing, P- and K-solubilizing bacteria from a purple soil improves the growth of Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) plantlets. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:00841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Rilling JI, Acuna JJ, Sadowsky MJ, et al. Putative nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with the rhizosphere and root endosphere of wheat plants grown in an Andisol from Southern Chile. Front Microbiol. 2018. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodríguez H, Fraga R, Gonzalez T, et al. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria. Plant Soil. 2006;287(1–2):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu CJ, Mou L, Yi JL, et al. The Eno gene of Burkholderia cenocepacia strain 71 – 2 is involved in phosphate solubilization. Curr Microbiol. 2019;76(4):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Li Y, Zhang JQ, Gong ZL, et al. Gcd gene diversity of quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase in the sediment of Sancha lake and its response to the environment. IJERPH. 2019;16(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Etesami H, Emami S, Alikhani HA. Potassium solubilizing bacteria (KSB): mechanisms, promotion of plant growth, and future prospects - a review. J Plant Growth Regul. 2017;17(4):897–911. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wojcikowska B, Belaidi S, Robert HS. Game of thrones among AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs-over 30 years of MONOPTEROS research. J Exp Bot. 2023;74(22):6904–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhang L, Hu Yl C, Yf et al. Cadmium-tolerant Bacillus cereus 2–7 alleviates the phytotoxicity of cadmium exposure in banana plantlets. Sci Total Environ. 2023;903:166645. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Song Q, Deng X, Song R, et al. Three plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria regulate the soil microbial community and promote the growth of maize seedlings. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(12):7418–34.

- 50.Wang C, Wang JF, Niu XL, et al. Phosphorus addition modifies the bacterial community structure in rhizosphere of Achnatherum inebrians by influencing the soil properties and modulates the Epichloe gansuensis-mediated root exudate profiles. Plant Soil. 2023;491(1–2):543–60.

- 51.Wu YY, Li Y, Niu LH, et al. Nutrient status of integrated rice-crayfish system impacts the microbial nitrogen-transformation processes in paddy fields and rice yields. Sci Total Environ. 2022. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reyes I, Bernier L, Simard RR, et al. Effect of nitrogen source on the solubilization of different inorganic phosphates by an isolate of Penicillium rugulosum and two UV-induced mutants. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28(3):281–90.

- 53.Hu TS, Wang FQ, Wang DM, et al. The characters of root-derived fungi from Gentiana scabra bunge and the relations with their habitats. Plant Soil. 2023;486(1–2):391–408.

- 54.Lv J, Liu S, Hu C, et al. Saponin content in medicinal plants in response to application of organic and inorganic fertilizers: a meta-analysis. Front Plant Sci. 2025. 10.3389/fpls.2025.1535170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo J, Zhou JJ, Zhang JZ. Aux/IAA gene family in plants: molecular structure, regulation, and function. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. 10.3390/ijms19010259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang YH, Wang Q, Di P, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the Aux/IAA gene family in Panax ginseng: evidence for the role of PgIAA02 in lateral root development. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. 10.3390/ijms25063470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamaguchi N, Komeda Y. The role of CORYMBOSA1/BIG and auxin in the growth of Arabidopsis pedicel and internode. Plant Sci. 2013;209:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Modrego A, Pasternak T, Omary M, et al. Mapping of the classical mutation rosette highlights a role for calcium in wound-induced rooting. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023;64(2):152–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.He J, Lu Q, Wu C, et al. Response of soil and plant nutrients to planting years in precious ancient Camellia tetracocca plantations. Agronomy. 2023;13(3): 914.

- 60.Zhang Q, Chang S, Yang Y et al. Endophyte-inoculated rhizomes of Paris polyphylla improve polyphyllin biosynthesis and yield: a transcriptomic analysis of the underlying mechanism. Front Microbiol 2023;14:1261140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Chen Y, Yu D, Huo J, et al. Studies on biotransformation mechanism of Fusarium sp. C39 to enhance saponin content of Paridis rhizoma. Front Microbiol. 2022. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.992318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hua X, Song W, Wang KZ, et al. Effective prediction of biosynthetic pathway genes involved in bioactive polyphyllins in Paris polyphylla. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1): 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song W, Zhang C, Wu J, et al. Characterization of three Paris polyphylla glycosyltransferases from different UGT families for steroid functionalization. ACS Synth Biol. 2022;11(4):1669–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Kumar S, Kalra S, Singh B, et al. RNA-seq mediated root transcriptome analysis of Chlorophytum borivilianum for identification of genes involved in saponin biosynthesis. Funct Integr Genomic. 2015;16(1):37–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Pearlin H, Lazarus S, Easwaran N. Molecular insights into PGPR fluorescent Pseudomonads complex mediated intercellular and interkingdom signal transduction mechanisms in promoting plant’s immunity. Res Microbiol. 2024;175(7):104218. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Aranega Bou P, de la Leyva O, Finiti M. I Priming of plant resistance by natural compounds. Hexanoic acid as a model. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Xing P, Zhao Y, Guan D, et al. Effects of Bradyrhizobium co-inoculated with Bacillus and Paenibacillus on the structure and functional genes of soybean rhizobacteria community. Genes. 2022. 10.3390/genes13111922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang SY, Li C, Si JP, et al. Action mechanisms of effectors in plant-pathogen interaction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. 10.3390/ijms23126758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fu S. Studies on the Microbiome of Paris polyphylla and its promotion of polyphyllin-transforming and P.polyphylla growth (D). Hunan: Central South University; 2023.

- 70.McRose DL, Newman DK. Redox-active antibiotics enhance phosphorus bioavailability. Science. 2021;371(6533):1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Fraser TD, Lynch DH, Gaiero J, et al. Quantification of bacterial non-specific acid (phoC) and alkaline (phoD) phosphatase genes in bulk and rhizosphere soil from organically managed soybean fields. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;111:48–56.

- 72.You M, Fang SM, MacDonald J et al. Isolation and characterization of Burkholderia cenocepacia CR318, a phosphate solubilizing bacterium promoting corn growth. Microbiol Res. 2020;233:126395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Sharma SB, Sayyed RZ, Trivedi MH, et al. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. Springerplus. 2013. 10.1186/2193-1801-2-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Bhanja E, Das R, Begum Y et al. Study of pyrroloquinoline quinine from phosphate-solubilizing microbes responsible for plant growth: in Silico approach. Front Agron. 2021;3:667339.

- 75.Mercedes Luduena L, Soledad Anzuay M, Guillermo Angelini J, et al. Role of bacterial pyrroloquinoline quinone in phosphate solubilizing ability and in plant growth promotion on strain Serratia sp S119. Symbiosis. 2017;72(1):31–43.

- 76.Rodríguez H, Gonzalez T, Selman G. Expression of a mineral phosphate solubilizing gene from Erwinia herbicola in two rhizobacterial strains. J Biotechnol. 2000;84(2):155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository under GnenBank (Accession numbers: PV682596-PV682620) and BioProject (Accession numbers: PRJNA955924 and PRJNA1266360).