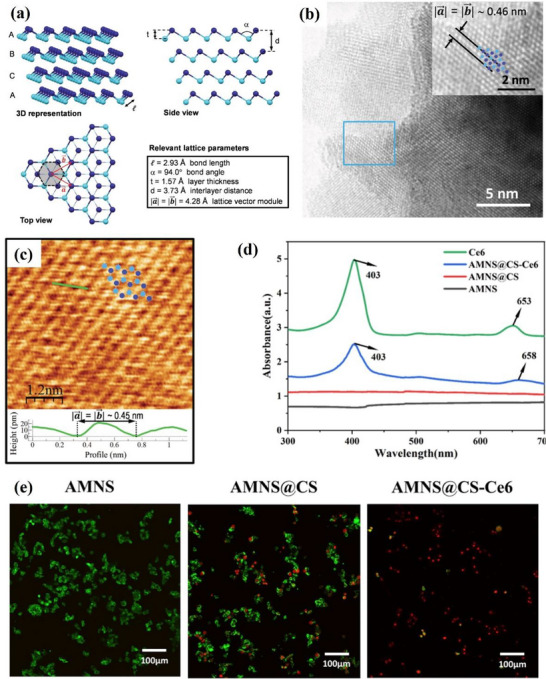

Abstract

Xenes, a class of mono‐elemental two‐dimensional (2D) materials, have emerged as promising candidate materials for next‐generation electronic and energy devices due to their unique structural and electronic properties. This review first systematically categorizes the eighteen experimentally realized Xenes into Group III–VI and other group categories, summarizing their synthesis routes, ranging from top‐down exfoliation to bottom‐up methods. Based on density functional theory (DFT), this paper focuses on theoretical predictions of stable phases and substrate interactions, which guide experimental preparation. Second, functional applications of Xenes in electronics, optoelectronics, catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine are also reviewed. The impact of atomic configurations on synthesis difficulty, environmental stability, and scalability across different element groups is also discussed. Finally, emerging strategies such as encapsulation, heterostructure design, and machine learning‐guided growth are evaluated to overcome inherent limitations. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of synthesis principles, structure‐property relationships, and stabilization strategies, offering insights into future scalable and robust Xene development directions.

Keywords: Xenes, 2D materials, bottom‐up method, top‐down method, machine learning‐assisted synthesis

This review summarizes the recent advances in mono‐elemental 2D materials, or Xenes, including their synthesis strategies, theoretical guidance, and stability challenges. It highlights emerging approaches such as deep learning‐assisted design with encapsulation techniques and heterostructure for scalable production and practical applications in electronics, energy, and biomedicine.

1. Introduction

Xenes, a family of monoelemental two‐dimensional (2D) materials composed of elements such as boron,[ 1 ] silicon,[ 2 ] phosphorus,[ 3 ] and bismuth,[ 4 ] have emerged as promising candidates for next‐generation electronic, optoelectronic, and energy‐related applications. These materials exhibit a variety of atomic arrangements, including planar, curved, and wrinkled geometric structures, and possess unique physicochemical properties such as high carrier mobility, strong spin‐orbit coupling (SOC), and tunable bandgaps.[ 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] The atomic thinness and surface‐dominated nature of Xenes further enhance their potential in fields including catalysis, energy storage, sensing, and nanoelectronics.

While early 2D material research was centered around graphene due to its extraordinary electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties, certain intrinsic limitations have gradually become apparent. The absence of a bandgap renders graphene semi‐metallic, hindering its use in applications that require digital switching, such as field‐effect transistors (FETs).[ 11 , 12 , 13 ] Furthermore, the weak SOC of graphene prevents significant bandgap opening via topological mechanisms, limiting its applicability in spintronics and quantum devices.[ 14 ] In energy storage, although graphene offers a high theoretical capacity as a lithium‐ion battery anode (up to 744 mAh g−1),[ 15 ] performance enhancements often rely on complex modifications such as heteroatom doping or nanoparticle hybridization, which compromise scalability and structural simplicity.[ 16 ] These challenges have motivated increasing attention toward Xenes, which retain the dimensional advantages of graphene while offering broader tunability via elemental composition and structural symmetry. For example, borophene and silicene exhibit high theoretical lithium‐ion storage capacity and strong adsorption behavior,[ 15 , 17 ] while bismuthene demonstrates an intrinsically opened bandgap suitable for optoelectronic and topological applications.[ 4 ] The diversity of Xene materials enables geometry‐ and element‐specific tuning of band structures, chemical activity, and interfacial interactions.

Despite these attractive features, the synthesis of Xenes remains a significant challenge. In contrast to van der Waals (vdWs) layered materials, many Xenes do not have stable bulk counterparts and cannot be derived via conventional exfoliation techniques.[ 4 , 5 ] Their experimental realization often requires finely tuned growth environments, substrate templating, and kinetic control to stabilize the 2D phase.[ 6 , 7 , 8 ] Moreover, issues such as ambient instability, substrate dependence, and low yield hinder their scalable production and device integration. Overcoming these bottlenecks requires a comprehensive understanding of synthesis mechanisms and stabilization strategies.[ 10 ] Over the past decade, both top‐down (e.g., chemical exfoliation, plasma etching) and bottom‐up (e.g., molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), chemical vapor deposition) approaches have been developed to fabricate Xenes,[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] each offering unique advantages and limitations in crystallinity control, material throughput, and platform compatibility. At the same time, advances in heterostructure engineering, encapsulation, and machine learning‐guided synthesis have opened new avenues for improving material stability and predicting optimal growth conditions.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] The interdisciplinary nature of Xene research, which encompasses surface science, solid‐state physics, computational modeling, and synthetic chemistry, further highlights the necessity of conducting a comprehensive study on their synthesis and stabilization.

Given the aforementioned progress, a systematic understanding of Xene synthesis strategies and stability enhancement methods is crucial for guiding their scalable preparation and practical integration. This paper reviews the latest advances in Xene synthesis, including the classification of top‐down and bottom‐up approaches and their mechanistic foundations. Representative Xenes are further discussed based on elemental families, with a focus on specific synthesis protocols, structural features, and key application areas. Particular attention is given to current challenges such as the difficulty of exploring synthetic pathways, stability issues in practical applications, and emerging solutions, including heterostructure design, encapsulation techniques, and data‐driven synthesis optimization. By systematically comparing the synthetic routes and stabilization strategies of multiple Xene families, this review has constructed a comprehensive framework, which is expected to stimulate more rational design ideas and provide assistance for the development process of practical applications of Xene‐based materials.

2. Synthesis Strategies of Xenes: From Graphene‐Inspired Approaches to Tailored Innovations

The synthesis of Xenes has evolved from graphene‐inspired methods to highly tailored strategies that address the unique structural and chemical demands of various elemental 2D materials. Early breakthroughs in graphene fabrication, such as mechanical exfoliation, liquid‐phase exfoliation (LPE), chemical oxidation‐reduction, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) as shown in Figure 1 , have established the conceptual framework for isolating atomically thin layers and understanding substrate effects.[ 12 , 21 , 22 , 23 ] However, due to the distinct atomic configurations, buckled geometries, and chemical sensitivities of Xenes, these conventional methods have required substantial adaptations and innovation.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Graphene synthesis methods.

The emerging synthesis techniques for Xenes fall broadly into two categories: top‐down and bottom‐up methods. While both categories build upon the legacy of graphene, they have been significantly extended and refined to meet the specific requirements of individual Xene systems.

2.1. Top‐Down Method: Controlled Exfoliation and Chemical Transformation

Top‐down strategies aim to derive monoelemental 2D nanosheets by disassembling bulk or layered precursors through mechanical, chemical, or electrochemical means. While these approaches were originally developed for graphene, such as mechanical exfoliation, chemical oxidation‐reduction, and LPE.[ 12 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] These methods have been significantly refined and diversified for Xenes to accommodate their diverse bonding structures and reactivity.

In the context of Xenes, top‐down methods no longer rely solely on vdWs interlayer separation, as is the case for graphene. Instead, they increasingly involve chemically guided transformations and selective etching routes. For instance, black phosphorus can be exfoliated into phosphorene through solvent‐assisted sonication under inert conditions to avoid oxidation.[ 1 ] Tellurene nanosheets have been manually exfoliated and subsequently stabilized in isopropanol (IPA) or N‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone (NMP), demonstrating improved dispersion and size uniformity.[ 4 ] Moreover, layered precursors such as Zintl‐phase compounds and BiTeI‐type structures have enabled electrochemical or chemical transformations to access bismuthene,[ 4 ] stanene,[ 27 ] and tellurene[ 28 ] derivatives. Under certain circumstances, intercalation‐assisted exfoliation is employed to weaken interlayer interactions before shear or sonication exfoliation, which improves both yield and crystallinity.

These innovative routes go beyond the trial‐and‐error exfoliation of graphene and introduce strategies tailored to the intrinsic chemistry of each Xenes system. By refining precursor chemistry, exfoliation environments, and post‐processing techniques, these methods significantly improve the thickness control, lateral size, oxidation resistance, and monodispersity of the resulting nanosheets. Therefore, this concept was initially proposed by the process of graphene exfoliation, and was further developed at the chemical level based on the “top‐down” design philosophy.

2.2. Bottom‐Up Method: Epitaxial Precision and Substrate Engineering

Bottom‐up methods construct Xenes atom‐by‐atom or molecule‐by‐molecule, offering precise control over phase, thickness, and crystallographic orientation. These methods originate from techniques used in graphene growth, particularly CVD and epitaxial growth. However, these methods have undergone extensive improvements and optimizations to meet the more complex requirements of Xenes synthesis.

Complementing vacuum‐based techniques, vdWs epitaxy has emerged as a powerful approach. For example, in the case of tellurene, chemical inert layered substrates such as mica can prevent unnecessary hybridization reactions and facilitate the formation of high‐quality crystal structures.[ 29 ] Moreover, solution‐based bottom‐up strategies such as solvothermal synthesis have enabled the production of large‐area few‐layer tellurene sheets under milder conditions, with lateral sizes exceeding 100 µm and excellent structural integrity.[ 30 ] Physical vapor transport methods have also been employed for ultrathin bismuthene and tellurene growth using controlled temperature gradients in sealed systems.[ 4 ] Furthermore, polymorphic Xenes such as borophene have benefited from phase‐selective deposition, where fine‐tuning the substrate lattice, deposition temperature, and post‐annealing profiles can yield distinct β12, χ3, or striped phases, each with different electronic and mechanical properties.[ 1 ] When these advanced deposition techniques are combined, they surpass the bottom‐up technical performance of graphene and enable the meticulous design of functional polymorphism, anisotropic properties, and integrable forms.

3. Xenes: Synthesis, Properties, and Potential Applications

Inspired by the discovery and synthesis of graphene, the concept of Xenes is proposed and subsequently realized experimentally. Many of the fabrication techniques developed for Xenes have been adapted from the graphene synthesis method. These fabrication methods can mainly be divided into the following two categories: top‐down method (e.g., mechanical exfoliation and LPE) and bottom‐up method (e.g., physical vapor deposition (PVD), CVD, and epitaxial growth). Unlike graphene which currently exists as monolayer nanosheets, most 2D‐Xenes are thermodynamically unstable at freestanding, prone to collapse or reconstitution into three‐dimensional structures, and require a suitable substrate to provide physical support in order to maintain their structural integrity.[ 31 , 32 ] At present, eighteen types of Xenes have been successfully synthesized, and the research on them is gradually deepening. Figure 2 shows the timeline of all the Xenes that have been experimentally synthesized so far. The concept of 2D allotrope silicon was first proposed in 1994,[ 33 ] and this material was later named “silicene” in analogy to graphene in a subsequent study.[ 34 ] The boron, an element adjacent to carbon in the periodic table, was proposed by Mannix et al. to prepare atomically thin borophene.[ 1 ] In addition, the group VIA element selenium, which exists in theory, has also been successfully synthesized by the PVD method, and large 2D selenium nanosheets have been obtained.[ 35 ]

Figure 2.

Timeline for the success of Xenes experimental synthesis.

Xenes exhibit numerous commendable characteristics. First, Xenes have the same 2D nanostructure as graphene, which gives them a large specific surface area. The large surface area also leaves their surface atoms exposed, giving them better atomic utilization. In addition, Xenes possess excellent photoelectric performance, including tunable bandgaps and high carrier mobility. These characteristics enable the broad‐spectrum light absorption to cover the ultraviolet and infrared regions, thereby generating superior light collection efficiency. Due to these characteristics, Xenes have great prospects in the field of photocatalysis, where efficient solar energy conversion is indispensable.[ 36 ] At the same time, due to their single chemical composition, Xenes are easier to be regulated and applied to defect engineering and other fields.[ 37 ] A variety of Xenes have only been synthesized in recent years, so there are few literatures that review their current research status. This article will review the Xenes that have been successfully synthesized, including their preparation methods, properties, and potential applications. In this review, these Xenes will be discussed based on the differences in the groups of elements in their periodic tables.

3.1. Group IIIA

In group IIIA, the 2D forms of four elements have been successfully prepared, including borophene, gallenene, indenene, and thallene. A preliminary introduction to their synthesis methods and morphology is statistically presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Xenes of Group IIIA elements.

| Xenes | Precursor | Synthetic method | Morphological characteristics | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borophene | Pure boron | MBE on Ag (111) | Anisotropic striped phases, with periodicity in a direction of 0.51 nm and b direction of 0.29 nm | [1] |

| Pure boron | MBE on Al (111) | Hexagonal lattice structure, planar and non‐wrinkled surface | [48] | |

| Pure boron | MBE on Ir (111) | Hexagonal lattice arrangement with (6 × 2) superstructure, rotational domain | [49] | |

| NaBH4 |

CVD, H2 as carrier gas |

With thicknesses of 3.4 nm, large coverage area | [50] | |

| Boron powder | LPE with sonochemical | Single or multi‐layer structure, lateral dimension achieves 1.2 microns | [54] | |

| Boron powder | Electrochemical exfoliation | Anisotropic crystal structure, good stability, with dimensions ranging from 400 to 600 nm | [55] | |

| Gallenene | Ga | Solid‐melt exfoliation (Si/SiO2) | Dynamic and stable metallic properties | [9] |

| Ga | MBE on GaN (0001) | Bialyer gallenene film, hexagonal structure with a thickness of 0.552 nm | [56] | |

| Indenene | In | MBE on SiC (0001) | Triangular lattice structure, honeycomb connectivity | [57] |

| Thallene | Tl | MBE on Si (111) | √3 × √3‐R30° superstructure with honeycomb geometry, planar surface | [58] |

| Tl | MBE like epitaxial on NiSi2/Si(111) | Non‐buckled structure, high‐crystallinity monolayer film | [59] |

3.1.1. Borophene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

As the first element of Group IIIA, and adjacent to carbon in the periodic table of elements, boron is a promising candidate for 2D materials. However, since boron has only three valence electrons, it cannot form a stable honeycomb structure like carbon in graphene. As early as 1997, theoretical calculations of the geometry of boron clusters were reported. Based on ab initio quantum‐chemical methods, the Aufbau principle was proposed to construct highly stable triangular lattice boron species structures.[ 38 ] Subsequent studies have also confirmed that boron clusters have planar or quasi‐planar structures.[ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] The theoretical study of 2D boron sheets has been carried out, and several structures have been predicted, such as α‐sheets,[ 43 , 44 ] β‐sheets,[ 45 ] and χ‐sheets.[ 46 ] Through experimental characterization, Liu et al. provided preliminary evidence of the production of layered structure of boron nanotubes in 2010.[ 47 ] However, 2D boron sheets (borophene) were not experimentally obtained until 2015. Mannix and his colleagues obtained atomic‐scale borophene by MBE method under ultra‐high vacuum (UHV) conditions using a solid boron atom source of 99.9999% purity as a precursor and Ag (111) as a substrate. The simulated structure of borophene on Ag (111) substrate is shown in Figure 3a,b.[ 1 ] This structure is consistent with the borophene structure of earlier theoretical studies. The scanning tunneling microscope (STM) topography image of the sample (Figure 3c) shows borophene with obvious anisotropic striped phases. Specifically, the periodicity in the a direction is 0.51 nm and that in the b direction is 0.29 nm. The atomic structure of the boron sheet in the simulated STM rectangular lattice and parallel fringe mode (Figure 3d), verified that the experimental synthetic material was borophene.[ 1 ] In 2018, the researchers successfully prepared borophene on the surface of Al (111) following the previously proposed method.[ 48 ] This borophene existed in the form of a planer hexagonal lattice structure with the lattice constant of 2.9 Å. In the following year, the epitaxial growth of borophene on an Ir (111) substrate was also reported, and its lattice structure was characterized by a hexagonal lattice arrangement with (6 × 2) superstructure and rotational domains (Figure 3e).[ 49 ] The author compared the molecular model optimized via DFT with the high‐resolution STM (HR‐STM) images, as shown in Figure 3f. The strong agreement between simulation and experimental results provides direct evidence supporting the atomic configuration of the synthesized borophene.[ 49 ] Further, CVD has been successfully applied. The method used sodium borohydride (NaBH4) powder as a boron source and quartz as a substrate. The researcher used hydrogen as the carrier gas, and the reaction was taken under 490 °C and 650 °C respectively for half an hour to produce borophene.[ 50 ] The synthesized borophene film has a thickness of 3.4 nm and a large coverage area on the substrate.

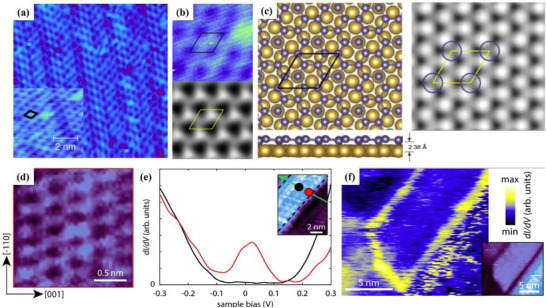

Figure 3.

Borophene: from atomic structure to device applications. a) Top and b) side views of simulated borophene on Ag(111), with the unit cell marked in green. c) STM image showing the striped‐phase atomic structure; inset highlights the rectangular lattice with lattice vectors. d) Simulated STM image of empty states overlaid with atomic positions; unit cell indicated in green. Reproduced with permission.[ 1 ] Copyright 2015, American Association for the Advancement of Science AAAS. e) Simulated hexagonal lattice of χ6‐borophene with (6 × 2) superstructure and visible rotational domains. f) Left: Simulated tunneling current isosurface of the χ6 structure; Right: Corresponding region from experimental STM imaging; Center: Proposed atomic model superimposed to illustrate agreement between simulated and observed lattice features. Reproduced with permission.[ 49 ] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society publications. g) Top and side views of the deformation charge density of B/G; h) Adsorption energies and charge transfer of Li in the interlayers of B/G, bilayer graphene, and bilayer borophene as a function of interlayer distance. Reproduced with permission.[ 51 ] Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. i) Step diagram of hydrogen adsorption Gibbs free energy (ΔG H*) for the χ3/TM@WS2 heterojunction; j) Volcano plot of HER overpotential for χ3/TM@WS2 heterojunctions as a function of ΔGH*. Reproduced with permission.[ 52 ] Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society. j) Device schematic of the sensor structure; k) Sensing response transients of borophene to varying concentrations of NO2. Reproduced with permission.[ 53 ] Copyright 2021, Springer Nature.

Synthesis—Top‐Down Method

With further study of borophene, other synthesis methods have been reported. Since boron does not exist in a layered structure, such methods often require the application of additional steps. In 2019, Ranjan et al. innovatively proposed a top‐down freestanding borophene synthesis method based on the principle of LPE combined with sonochemical.[ 54 ] Freestanding borophene sheets were synthesized via sonochemical exfoliation of boron powder in polar solvents such as acetone. The borophene synthesized by this method has a thickness ranging from single layer to multiple layers, and the transverse dimension can reach 1.2 microns. Inspired by the method of synthesizing graphene, a method based on electrochemical exfoliation has also been proposed by Chowdhury et al. .[ 55 ] This method took advantage of the characteristic that the electrical conductivity of boron changes with the change of temperature. Boron, which had similar electrical conductivity to metal under high temperature,[ 60 ] was used as the cathode, and platinum was used as the anode. The boron sheets were collected in the electrolyte solution (ionic liquid, aqueous inorganic salt, etc.). Then, the collected boron sheets were transferred to acetone, and after ultrasonic and centrifugal treatment, the supernatant was collected and dried to obtain borophene. The product exhibits anisotropic crystal structure and good stability, with a size range of 400 to 600 nm.

Properties and Potential Applications of Borophene—Energy Storage

The high theoretical capacity, rapid ion diffusion, and low energy barrier of borophene make it have great application potential in energy storage fields such as batteries and hydrogen storage. For example, lithium ion batteries (LiBs), with the high energy efficiency and environmentally friendly sustainability, has become the current energy storage choice for mobile electronic devices and electric vehicles.[ 61 ] As a typical representative of 2D materials, graphene has achieved great success in LiBs[ 62 ] because of its superior electrical conductivity and large specific surface area.[ 63 , 64 ] However, its high diffusion barrier (≈0.3 eV) leads to the problem of slow charging and discharging of the battery.[ 8 ] The emergence of borophene is expected to provide important conditions for breakthroughs in LiBs. Borophene has an excellent adsorption effect on lithium ions. Both Zhao et al.[ 65 ] and Yang et al.[ 62 ] simulated the adsorption and diffusion behavior of lithium ions on the surface of borophene based on the DFT calculations. The diffusion barrier of Li simulated by Yang et al. on borophene on the flat can be as low as 0.007 eV, which can be negligible. Zhao's group simulated a fully lithiated borophene (a boron combined with 0.75 lithium) with a theoretical capacity of 1860 mAh g−1, which is much larger than graphene (744 mAh g−1).[ 15 ] Borophene showed potential as an anode material for LiBs with a low diffusion energy barrier of 3 meV and a strong adsorption energy of 2.92 eV.[ 62 , 66 ] Research on the Li modification of borophene[ 65 ] has led to more exploration. Er et al. found that the hydrogen storage capacity of borophene is significantly improved after the absorption of alkali metal elements such as Li, Na, and K.[ 67 ] The hydrogen storage capacity of borophene after Li‐decoration can reach 10.7 wt% molecular hydrogen with the average energy of 0.15 eV/H2. The results indicate that alkaline metal‐modified borophene has excellent application prospects for hydrogen storage. One study also used few‐layer borophene as the electrode material in supercapacitors. This capacitor exhibits a wide potential window of 3.0 V and a power density of up to 478.5 W kg−1. After 6,000 cycles, it still retained 88.7% of its initial capacitance, indicating excellent cycling stability.[ 68 ] At the same time, the construction of 2D–2D heterostructures such as borophene/graphene (B/G) has proven effective in enhancing the structural stability of borophene while retaining its remarkable electrochemical properties. As shown in Figure 3g, pronounced interfacial charge redistribution occurs, with electrons transferring from graphene to borophene, forming a stable vdWs interface without disrupting the intrinsic metallicity.[ 51 ] Moreover, Figure 3h demonstrates that lithium atoms preferentially adsorb in the interlayer region, with a minimum adsorption energy of −2.959 eV at a spacing of 4 Å and maximum charge transfer around 4.5 Å. These findings not only highlight the tunability of interlayer interactions in heterostructures, but also underscore the synergistic effect of combining two 2D materials, resulting in enhanced Li binding and charge transport performance.[ 51 ] Borophene shows great promise in energy storage field due to its ultralow ion diffusion barriers, high theoretical capacities, and strong adsorption energies. Its metallic conductivity and flexible structure enable rapid charge transport and interfacial tunability, especially in heterostructures like B/G composites. Compared to graphene, borophene offers faster kinetics and higher storage capacity. However, challenges such as environmental instability, synthesis scalability, and mechanical fragility hinder its practical deployment. Addressing these through surface engineering and composite design is key to realizing its application potential.

Properties and Potential Applications of Borophene—Catalytic Field

In the catalytic field, the high surface‐to‐volume ratio and electronic tunability of borophene render it a promising candidate for hydrogen evolution reactions (HER). DFT calculations have revealed that both α‐ and β12‐phase borophene possess nearly ideal hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH*) close to zero, particularly at low‐coordination sites around hexagonal holes, achieving ΔGH* ≈ 0.00 – 0.04 eV, comparable to or surpassing that of Pt.[ 69 ] Although borophene synthesized via MBE adheres strongly to metallic substrates, computational studies indicate that Ag(111) not only stabilizes the boron lattice but can also modulate its electronic states to preserve or even improve HER activity, while substrates like Cu(111) cause excessive electron transfer and performance deterioration. To further optimize HER performance and overcome borophene's intrinsic air instability and limited H‐trapping capability due to its inert basal plane, Yang et al. proposed a vdWs heterojunction structure by integrating χ3‐type borophene with 2H‐WS2.[ 52 ] This heterojunction exhibited excellent catalytic performance with ΔGH* values as low as −0.022 eV (H4 site) and −0.053 eV (H1 site) as shown in Figure 3i, benefiting from enhanced charge redistribution and metallic behavior near the Fermi level induced by interlayer coupling. Remarkably, upon doping noble metal atoms (Pt or Pd) into either the borophene or WS2 layer, the system demonstrated further reduction of ΔGH* to near‐zero (0.005 eV for Pt@WS2 configuration), placing the system near the top of the HER volcano plot (Figure 3j). These heterostructures not only improve catalytic kinetics but also enhance structural stability by anchoring reactive borophene onto more chemically inert substrates. The high surface area of borophene 2D nanostructure also enables it to have a large number of active sites. For example, borophene can be used as a catalyst in HER with near‐zero free energy.[ 69 ] Considering that the borophene synthesized by the MBE method is difficult to separate from the substrate, the catalytic performance of borophene/Ag (111) in the HER is also calculated. The results show that the substrate has no negative effect on the catalytic effect.

Properties and Potential Applications of Borophene—Gas Sensors

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of borophene in gas sensors, owing to its high carrier mobility.[ 54 ] A borophene‐based NO2 sensor was successfully fabricated, demonstrating outstanding performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and response dynamics at room temperature. As schematically illustrated in Figure 3k, the sensor architecture consists of ultrathin borophene sheets deposited on a quartz substrate with interdigital Cr/Au electrodes, enabling reliable electrical readout upon gas exposure. The use of high‐quality α‐phase borophene with well‐defined lattice structures ensures effective charge transfer and robust surface activity essential for gas adsorption. Notably, the sensor exhibits an exceptionally low detection limit of 0.2 ppm, outperforming conventional 2D material‐based sensors such as those using graphene, MoS2, or phosphorene under the same room temperature conditions. As shown in Figure 3l, the borophene sensor exhibits a rapid, concentration‐dependent electrical response toward NO2 in the range of 0.2–100 ppm, with a response time of ∼30 s and recovery time of ∼200 s.[ 53 ] The use of 2D semiconductor materials (MoS2, WS2) are the substrate of the β1‐borophene sheet has improved the thermal stability and enhanced the gas sensing performance.[ 45 ] Even under significant bending angles (0°, 45°, and 90°), the device sustains nearly unchanged signal intensity when exposed to 2 ppm NO2, demonstrating its mechanical resilience and functional stability. Compared with common graphene, MoS2, or reduced graphene oxide sheets sensors, borophene‐based sensors have broad prospects for higher sensitivity and faster reaction rates.[ 70 ] Borophene shows great promise for gas sensing due to its high carrier mobility, active surface, and flexibility. It achieves ultra‐low NO2 detection limits with fast response at room temperature, outperforming graphene and MoS2‐based sensors. Its performance remains stable under mechanical deformation. However, challenges such as environmental instability, oxidation, and scalable fabrication limit practical use. Structural engineering and encapsulation are needed to enable reliable, flexible sensing applications.

3.1.2. Gallenene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

Gallium is in the IIIA group of the fourth period in the periodic table of elements. Interestingly, while most other 2D materials, such as graphene, are linked by vdWs forces between adjacent layers.[ 71 ] Gallium is a quasi‐layered material that connects adjacent 2D planes through covalent bonds.[ 72 ] Compared with other 2D materials, the covalent interaction in gallenene helps enhance its thermal stability, but this also makes gallenene difficult to obtain through direct top‐down exfoliation. The 2D gallium film was prepared by Zhang et al.[ 56 ] in 2015. They used a gallium source with a purity of up to 99.995% to obtain Ga films on an Al2O3 substrate by epitaxial growth method by metal‐organic CVD. GaN with a thickness of 3 microns was deposited on Al2O3 for the growth of Ga films, and there was a 25 nm AlN buffer layer between the substrate and Al2O3. Bilayer gallium films were obtained by this method. The morphology of the atomic plane Ga film is shown in Figure 4a. The bilayer Ga atomic film has a hexagonal structure (Figure 4b), with a thickness of approximately 0.552 nm.

Figure 4.

Atomic configurations and phonon characteristics of Gallenene. a) Topographic image of bilayer gallium film; b) Top and profile structure diagram of Ga/GaN, where Z is the average separations between each layer; Reproduced with permission.[ 56 ] Copyright 2015, APS. c) Diamond flat punch surface image (i–iii is void change, iv is a monolayer of Ga); d) Schematic diagram of two gallenene structures where the top one is Ga (010) and bottom one is Ga (100). Reproduced with permission.[ 9 ] Copyright 2018, American Association for the Advancement of Science. Phonon dispersion, phonon DOS, Eliashberg function α2F(ω), and electron–phonon coupling strength λ(ω) of e) Ga (100) and f) Ga (010). Reproduced with permission.[ 73 ] Copyright 2021, IOP Publishing. g) Phonon dispersion of w‐gallenene. Reproduced with permission.[ 74 ] Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Synthesis—Top‐Down Method

However, the top‐down approach has been explored as the research deepens. The monolayer and few‐layer Ga films are exfoliated from the molten Ga solid surface in 2018.[ 9 ] This method takes advantage of the fact that the high thermal vibration of metals leads to a decrease in their strength at temperatures near the melting point. At the interface between the solid metal substrate and the liquid metal, temperature differences can induce heterogeneous nucleation, leading to the growth of solid crystalline layers on top of the liquid metal. Due to the difference in strength, the force required to separate the solid crystals from the surface will be greatly reduced. The method exploits this feature and names it the ‘solid‐melt exfoliation technique’. Specifically, this group placed liquid Ga (50 °C) onto a Si/SiO2 substrate and cooled it to room temperature (30 °C) under UHV conditions. Strain is applied with a diamond flat punch to form a void, and a monolayer of Ga is finally separated (Figure 4c). The stress required to separate the Ga monolayer is 1.5 MPa. Interestingly, the report also successfully found the predicted lattice orientations of two different gallenene films. As shown in Figure 4d, a quasi‐2D multilayer structure is formed by exfoliation along the direction of α‐Ga (010). In contrast, the single layer of gallium atoms obtained by exfoliation along the direction of α‐Ga (100) forms a honeycomb structure after relaxation.

Properties and Potential Applications Of Gallenene

Although the number of studies on the properties of gallenene is limited till nowadays, the unique physical properties of gallenene make it an exciting 2D material. 2D gallenene represents metallic properties. Gallenene obtained by solid‐melt exfoliation has two distinct lattice planes: Ga (100) and Ga (010). Gallenene materials in both structures have excellent electrical conductivity, very high electrical conductivity, and even 2D superconductivity.[ 9 ] The stable structure of gallenene enables it to be transferred to any substrate in principle, while maintaining its structure and electronic properties while minimizing the electronic property deviation caused by hybridization. For instance, Ga (100) has good structural stability on metal (Al, Ag, and Ni) and ceramic (GaN) substrates and retains excellent electronic properties. The study of the structure of two gallenene by DFT calculations shows that the phonon band structure of their relaxed structure only has a biaxial tensile strain of 5% and 2%, respectively.[ 73 ] Their strain‐stabilized phonon dispersions show no imaginary frequencies (Figure 4e,f), verifying their robustness for substrate integration. The Fermi surface forming principle of Ga (100) and Ga (010) is different, resulting in their different density of states at the Fermi level (Ga (100) is 0.91 eV and Ga (010) is 0.43 eV per atom). Moreover, the coupling of low‐energy phonon modes in both gallenene structures is extraordinarily strong, especially in Ga‐010. The electron‐phonon coupling of both two structures is sufficient to induce superconductivity. Another study showed that gallenene with hydrogen addition (known as “gallenane”) has stronger electron‐phonon coupling.[ 74 ] In particular, the hydrogenation both one‐sided and two‐sided suppresses dynamical instabilities and significantly increases in‐plane stiffness and work function. As shown in Figure 4g, the phonon band structure of one‐sided hydrogenated w‐gallenene becomes fully stable without external strain, indicating the effectiveness of hydrogenation in reinforcing lattice dynamics. The stability of gallenene under high strain, easy of transferring from substrates and superconducting properties make gallenene a promising cornerstone for advancing the fundamental discipline of nano mechanics in the future.

3.1.3. Indenene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

Indenene is a new member of the 2D material family. Early theoretical research on indenene used the lattice structure of 2D materials with honeycomb lattice.[ 75 ] Bulk indium possesses a body‐centered tetragonal structure rather than a vdWs layered structure. However, certain atomic planes in the unit cell mimic the geometry of buckled indenene, suggesting that epitaxial techniques may yield monolayer indenene. Bauernfeind et al. considered that In may be arranged in a triangular lattice when deposited on a substrate with a hexagonal structure.[ 57 ] They successfully realized the triangular lattice structure of monolayer indium on the surface of SiC (0001). The substrate used is 4H‐SiC (0001), prepared by hydrogen atmosphere dry etching process in which hydrogen atoms are introduced to SiC. The substrate that has undergone the above steps has an atomically flat and ordered surface to promote the epitaxial growth of indium. After thermal desorption of surface‐saturated hydrogen from the substrate, ultra‐high purity indium (99.9999%) was used as the evaporation source. The indium atoms preferentially bonded to sites other than the silicon atoms on the substrate, resulting in the successful formation of a monolayer structure, as shown in Figure 5a,b. The triangular lattice of indenene has been confirmed, and the side view of the structure model of indenene (Figure 5c) and the STM height profile (Figure 5d) have been reported, which is conducive to the further exploration of the electronic structure and topological properties of indenene.

Figure 5.

Structural and band characteristics of freestanding indenene. a) STM image showing the triangular lattice of indenene and the (1×1) unit cell with distinct A and B sites; b) The film edge between the freestanding indenene monolayer and the uncovered SiC substrate; c) Side view of the structural model highlighting the In–Si bond at the interface; d) STM height profiles along the red and orange lines in (a), revealing lattice constant and A/B asymmetry; gray curve from bare SiC confirms matching lattice periodicity; e) Angle‐Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES) spectra overlaid with DFT‐calculated bands (red) along high‐symmetry directions. The faint features near the Fermi level are artifacts from He–I satellite lines. Inset: zoomed‐in view at the K‐point showing a clear band gap between upper and lower Dirac cones; f) Energy distribution curve (EDC) peak positions near the K‐point, marked in orange, extracted from fits at selected momentum values; g) EDC at the K‐point (red) with fitted peaks (orange dashed lines) and total fit (blue), resolving VB‐1, VB, and CB states. Reproduced under the terms of the CC‐BY license.[ 57 ] Copyright 2021, Maximilian Bauernfeind et al.

Properties and Potential Applications of Indenene—Electronic Devices

The exploration of the synthesis of indenene has revealed that the topological properties of indenene can be tuned by adjusting synthesis conditions, which sparked the interests of researchers in the prospect of indenene as a 2D quantum spin Hall (QSH) insulator material. The angle‐resolved photoelectron spectroscopy and DFT calculated energy band structure show that in the presence of SOC, a band gap with a size of E = 70 meV exists. As shown in Figure 5e, this gap occurs between the spin‐split Dirac‐like bands centered at the K/K′ points, which are clearly resolved in both the DFT‐calculated red curves and the experimentally observed ARPES spectra. Notably, the experimental data confirm that the upper and lower Dirac cones do not connect continuously, forming a true energy gap rather than a semi‐metallic touching point. Furthermore, Figure 5f presents a detailed energy distribution curve (EDC) peak fitting near the K‐point, where the orange markers indicate experimentally extracted band positions. These peaks precisely follow the Dirac‐like dispersion and clearly resolve the conduction and valence band edges, enabling accurate determination of the gap size. The presence of bandgap allows further topological features of indenene to be observed.[ 57 ] According to DFT calculations, it is found that its topology can be changed by the relative strength of inversion‐symmetry breaking (ISB) and SOC. Due to the presence of SiC substrate, the smaller the bond length d of indium and Si as shown in Figure 5c, the stronger the effect of ISB on the indenene layer. The calculated equilibrium bond distance of In/SiC (d = 2.68 Å) is very consistent with the one obtained by X‐ray standing wave (d = 2.67 ± 0.04 Å). This alignment supports the substrate‐induced inversion symmetry breaking observed in the STM height asymmetry (Figure 5d), which directly lifts the A/B sublattice degeneracy and contributes to the band inversion. Furthermore, the EDC fitting at the K‐point (Figure 5g) reveals three distinct peaks, with a minimum direct band gap of ≈125 meV further validating the SOC‐induced topological band structure. The congruence between the theoretical and experimental bond lengths substantiates the presence of ISB and SOC resulting from Si–In bonding, which in turn leads to the emergence of additional electronic states at the interface, thereby inducing the formation of topological edge states. This confirms the non‐trivial topological nature of indene as a material.[ 57 ] However, indenene is inherently unstable and can only be studied under UHV conditions, such as STM and X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), limiting the exploration of its properties. A very recent study has proposed a solution to overcome the shortcomings of the inherent instability of indenene. In topological physics, intercalation is usually used to adjust the energy gap induced by SOC of graphene materials.[ 76 ] Schmitt et al. reversed the roles of the intercalation material and graphene, where graphene is used as the intercalation to protect indenene and make it a stable QSH insulator.[ 77 ] The In/SiC material with a graphene‐protected thin layer was characterized under non‐UHV conditions and showed excellent performance. Although the conductivity of graphene may interfere with edge transmission measurements, it has undoubtedly succeeded in protecting the indenene‐based QSH insulator material, providing a solution for the manufacture of QSH insulator devices. Indenene exhibits a tunable SOC‐induced band gap and nontrivial topological features confirmed by DFT and ARPES. Graphene intercalation enables stabilization under ambient conditions. However, current studies remain at the fundamental level, with no practical device integration yet achieved. Further efforts are needed for scalable synthesis and edge‐state transport validation.

3.1.4. Thallene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

Bulk thallium crystallizes in a hexagonal structure with metallic bonding, lacking the vdWs layered character required for exfoliation. Therefore, the synthesis of thallene requires a bottom‐up approach. Gruznev et al. followed the synthesis process of other Xenes and fabricated thallene by epitaxial growth in 2020.[ 58 ] NiSi2/Si (111) was selected as the substrate due to its unique compatibility with thallium atoms. This substrate provides a stable template, promoting the crystallization of Tl atoms into a honeycomb lattice. Specifically, the interaction between the Tl atom and the NiSi2 layer is crucial for stabilizing the thallium structure. The substrate has the ability to induce the ordered structure of Tl atoms, thereby forming the desired planar honeycomb lattice. DFT calculations also prove that the existence of NiSi2 layers is energy‐beneficial for the formation of thallene. As a more recent advance in thallene synthesis, Mihalyuk et al. further improved the quality and functionality of thallene monolayers by introducing an interfacial Sn layer between thallium and the NiSi2/Si(111) substrate.[ 59 ] The Sn decoration effectively decouples thallene electronically from the substrate, enabling the formation of large‐scale, flat honeycomb thallene with minimal substrate‐induced perturbation. This interface engineering strategy not only stabilizes thallene growth but also introduces promising spintronic functionalities, making it a compelling candidate for future 2D‐Xene–based devices.

Properties and Potential Applications of Thallene—Electronic Devices

There are few reports on the properties and potential applications of thallene. However, a recent study explored the properties of hydrogenated thallene. Since the QSH effect of graphene was reported,[ 14 ] many graphene‐like 2D materials have also been found to possess this effect. As a topological trivial extension semiconductor material, the QSH effect of thallene can be realized by large biaxial strain.[ 78 ] Gruznev et al. reported that the structure of monolayer thallene is a flat 2D honeycomb lattice structure without buckling.[ 58 ] Building on this work, Liu et al. established the molecular model of hydrogenated thallene (Tl2H and Tl2H2) and performed DFT calculations.[ 78 ] Due to the bonding of different hydrogen atoms, the lateral geometry of these two forms of thallene shows low curvature (Figure 6a) and plane (Figure 6b) structures. The optimal lattice constants of Tl2H and Tl2H2 are 5.24 Å and 5.28 Å, respectively, as shown in Figure 6c,d. The calculated formation energies of the two types of thallene hydrides are ‐1.60 eV and ‐2.23 eV, respectively, which indicates that the reaction between thallene and hydrogen molecules is an exothermic reaction, and the feasibility of functional synthesis of this material is proved. The QSH states of the two thallene remain stable at 5% strain and have topological nontrivial band gaps much higher than those of most QSH insulators. The foundation for the creation of topological electrical devices operating at ambient temperature is believed to come from thallene materials. DFT calculations confirm the feasible synthesis and structural stability of thallene. Compared to other QSH materials, thallene offers promising band topology without buckling. However, current findings remain theoretical, and experimental realization and device integration have yet to be achieved.

Figure 6.

Atomic structures and energetic profiles of Thallene. The top and side views of the structure of a) Monolayer Tl2H and b) Monolayer Tl2H2. The green balls represent Tl, and the white balls represent H atoms, respectively; c,d) The total energy of monolayer Tl2H and Tl2H2 structures varies with the lattice constants. Reproduced under the terms of the CC‐BY license.[ 78 ] Copyright 2023, Xiaojuan Liu et al.

3.2. Group IVA

Belonging to group IVA, carbon, silicon, germanium, tin, and lead share a valence configuration of ns2np2, enabling the formation of four covalent bonds.[ 31 , 32 ] Although carbon can easily form a planar sp2 hybridized graphene lattice, other common IVA elements can also exist in a 2D hexagonal structure under restricted conditions, although they usually exhibit slight buckling to stabilize their 2D configuration. Table 2 summarizes the synthesis and morphology of the four Xenes (silicene, germanene, stanene, plumbene) in group IVA.

Table 2.

Xenes of Group IVA elements.

| Xenes | Precursor | Synthetic method | Morphological characteristics | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicene | Si | MBE on Ag (111) | Hexagonal honeycomb structure, with a height of approximately 0.1 nm | [79] |

| Silicon film | PLD in Argon atmosphere | Hexagonal lattice, novel rectangular lattice structure (lattice distance 0.23 nm) | [80] | |

| CaSi2 | Wet‐chemical exfoliation | An accordion‐like microstructure, each layer with a thickness of ≈0.6 nm | [81] | |

| CaSi2 | Vacuum–Nitrogen Assisted topotactical deintercalation | Multilayer stacked flakes, lateral size from 2–3 µm to ≈100 µm | [82] | |

| Germanene | Ge | MBE on Au (111) | Clear hexagonal honeycomb structure, smooth surface | [83] |

| Ge | MBE on Pt (111) | Hexagonal honeycomb structure with folded configuration (0.6 Å) | [84] | |

| GeCa2 | Mechanical exfoliation | Smooth surface, uniform thickness, and layered structure | [85] | |

| Stanene | Sn |

MBE on Bi2Te3 (111) |

Buckling hexagonal honeycomb lattice with wrinkles (approximately 0.1 nm) with a random height modulation (0.06 nm) | [86] |

| Li5Sn2 | LPE | Height of 4 nm and transverse dimension of several micrometers, lattice spacing of 0.29 nm | [27] | |

| Plumbene | Pb | MBE on Pd (111) | Hexagonal lattice structure, unit cell size is ≈0.48 nm, flat structure | [87] |

3.2.1. Silicene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

As a Group IVA element like carbon, silicon has been considered for the possibility of having a 2D structure for decades. As early as 1994, Takeda and Shiraishi proposed a theoretically stable wavy aromatic configuration in which silicon can form.[ 33 ] In 2007, Guzman‐Verri et al. further investigated this theory and named the 2D nanostructure of silicon as silicene.[ 31 ] However, silicon contains sp3 hybridization of strong covalent bonds, and there is no allotrope of silicon in nature, as graphite for graphene. It is not easy to fabricate silicene by mechanical exfoliation methods, like the way of graphene synthesis.[ 12 ] Therefore, the epitaxial growth method was used in experiments to synthesize silicene. In 2010, synthetic silicon nanoribbons were reported.[ 2 ] Nonetheless, the fabrication approach of silicene based on MBE was reported in 2012 Ag (111) was used as a substrate, which was cleaned by Ar+ sputtering and annealed at 530 °C. Then, silicene was fabricated by depositing directly heated silicon crystal as the precursor on the substrate surface between 220 and 260 °C under UHV.[ 79 ] The DFT simulation results calculated by Vogt et al. are shown in Figure 7a, including both the side and top views of the silicene structure. Figure 7b compares the simulated silicene structure with the experimental STM image, and the two structures are consistent.[ 79 ] The silicene film presents a honeycomb structure, and the thickness is approximately 0.1 nm obtained by measuring the edge of the film.

Figure 7.

From atomic structure to device integration: synthesis and strain engineering of silicene‐based materials. a) Atomic structure of silicene on Ag(111): top view, side view, and highlighted hexagonal unit cell (white circle); b) Left: Simulated silicene structure STM image; Right: Experiment observed STM image for silicene structure. Reproduced with permission.[ 79 ] Copyright 2012, American Physical Society. c) Schematic illustration of CaSi2 deintercalation into silicene via conventional and VANS methods. Reproduced under the terms of the CC‐BY license.[ 82 ] Copyright 2024, Erika Kozma et al. d) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process for silicene‐based bendable membranes, including epitaxial growth, encapsulation, mechanical delamination, and transfer onto flexible substrates; e) Schematic of the three‐point bending setup used to apply uniaxial strain to bendable silicene membranes; f) Raman peak positions of monolayer and multilayer silicene membranes under applied strain; g) Raman shift of monolayer (left) and multilayer (right) silicene–stanene heterostructures as a function of applied strain. Reproduced under the terms of the CC‐BY license.[ 92 ] Copyright 2023, Christian Martella et al.

Unlike graphene, the honeycomb lattice structure of silicene exhibits a curved arrangement due to its sp3/sp2‐like hybridization, which is also consistent with earlier theoretical studies.[ 31 , 33 ] The success of the experiment of epitaxial growth to synthesize silicene has aroused greater interest, and subsequent substrates such as Ir (111),[ 88 ] MoS2,[ 89 ] and Pb (111)[ 90 ] have also been reported. Interestingly, silicon atoms grow on the same substrate to form different structures, such as herringbone structure and graphene‐like honeycomb crystal structure on the surface of Ru (001). This difference can be attributed to the coverage of silicon atoms. The herringbone structure is more favorable in terms of energy, resulting in low atomic coverage. As the atomic coverage increases, new silicon atoms attach to the elbow of the existing herringbone structure to form a hexagon, which gradually develops into a honeycomb structure.[ 91 ] A novel method of synthesizing silicene by pulsed laser deposition (PLD) method has been proposed in recent years. The report uses a high‐energy pulsed laser beam (wavelength 1064 nm) directed at the surface of a silicon wafer to heat the silicon to a molten or vaporized state rapidly.[ 80 ] The molten or vaporized silicon was then transported in the form of plasma to the surface of an amorphous carbon substrate, which was eventually deposited and formed as a film of amorphous silicon. Then, according to the nanoscale characteristics of electron de Broglie waves, silicene crystals were generated by electron beam irradiation (with a density of 0.5 nA nm−2). Through TEM characterization, silicene crystals have two structures: one is a hexagonal lattice, and the other is a newly discovered rectangular lattice (with a lattice distance of 0.23 nm). Theoretical calculations show that rectangular lattice silicene exhibits lower energy than hexagonal lattice during the optimization process and shows better dynamic stability.[ 80 ]

Synthesis—Top‐Down Method

However, the difficulty of silicene transfer from the substrate due to epitaxial growth limits further research. A top‐down approach was reported recently. This report suggested a method to synthesis silicene by wet‐chemical exfoliation.[ 81 ] Bulk silicon adopts a diamond cubic lattice with strong covalent sp3 bonding, thus lacking the weak interlayer forces required for exfoliation. Consequently, silicene synthesis in this work relies on topochemical deintercalation from layered Zintl‐phase CaSi2 rather than direct exfoliation from elemental silicon. The silicon layer is diffused from the outside to the inside by the oxidation of I2 to obtain multilayer silicon nanosheets. Through thermal expansion, nitrogen cooling, and gasification, monolayer silicene can be exfoliated. The obtained multilayer silicene nanosheets have a structure similar to that of an accordion and the thickness of each layer is 0.6 nm. Similarly, another method for large‐scale preparation of silicene based on liquid oxidation and CaSi2 exfoliation has also been proposed.[ 93 ] Building upon these top‐down strategies, Kozma et al. introduced a Vacuum–Nitrogen Assisted (VANS) deintercalation method, which enables the rapid production of multilayer hydrogen‐terminated silicene nanosheets under ambient conditions as shown in Figure 7c.[ 82 ] This method alternates vacuum and nitrogen purging to accelerate the removal of hydrogen gas generated during the reaction with hydrochloric acid, thereby significantly enhancing the deintercalation kinetics. Compared to previous methods that require days of low‐temperature processing, the VANS method completes the synthesis within minutes and yields high‐quality silicene with minimal oxygen contamination and reduced defect density. Such an approach offers improved scalability and compatibility with flexible or solution‐processed electronics, positioning VANS‐derived silicene as a promising candidate for future device‐level integration.

Properties and Potential Applications of Silicene—Energy Storage

The research on the application of silicon‐based materials in the field of energy storage, particularly in LiBs, has a long history. However due to the significant volume expansion and contraction of silicon during the charge‐discharge cycle, the development of this field is challenging.[ 94 ] Similar to Group IIIA borophene, silicene has been explored for energy storage because of its excellent ability to bind lithium atoms and its ultra‐high theoretical capacity.[ 95 ] The low diffusion barrier (0.2 eV) of silicene is also a competitive advantage for its applications in LiBs.[ 96 ] Binary system studies of silicon and lithium propose that each silicon atom can hold 4.4 lithium atoms, reaching a specific insertion capacity of 4200 mAh g−1.[ 17 ] The 2D layered structure of silicene can also buffer the volume change. Liu et al. carried out DFT calculations of silicenes they synthesized to explore the maximum Li adsorption numbers (0.5 and 0.43, respectively) of monolayer and bilayer silicenes, and the capacities were calculated as 954 and 715 mAh g−1, respectively. The electrochemical performance of LiBs using silicene as anode material was also evaluated by cyclic voltammetry. After 100 cycles, silicene still retains 76% of its original reversible capacity, demonstrating cycling stability. Additionally, silicene has excellent electrochemical performance even at an extremely high current density (5 A g−1) and maintained stable capacity (312 and 596 mAh g−1, respectively) after 1800 cycles.[ 93 ] Another report also obtained the same theoretical capacity in LiBs of single and bilayer silicene anodes and calculated the volume change of their physicochemical processes to 13% and 24%, respectively.[ 97 ] Silicene has also been found to have potential applications in supercapacitors. Quantum capacitance refers to the amount of charge stored per unit mass of a material and is an important parameter for evaluating the performance of supercapacitors. An ab initio molecular dynamics study based on non‐equilibrium Green's function combined with DFT was used to calculate the quantum capacitance of graphene, silicene and carbon nanomaterials. The results showed that, in terms of weight capacitance, silicene double‐layer capacitors had the highest specific capacitance (electrostatic potential energy (EP) of 2.59 µF cm−2), followed by graphene (EP of 2.35 µF cm−2) and carbon nanotubes (EP of 1.36 µF cm−2).[ 98 ] Guo et al. for the first time assembled silicene into a high‐voltage symmetric supercapacitor with a voltage window of 0–3 V, a maximum specific capacitance of 0.41 mF cm−2, an energy density of up to 1.22 mJ cm−2, and a capacitor retention rate of up to 96.6% after 10 000 cycles, demonstrating the excellent electrochemical performance of silicene for supercapacitor applications.[ 99 ] Silicene offers high theoretical capacity and low Li diffusion barriers, supporting its potential in LiBs and supercapacitors. Its 2D structure mitigates volume expansion, while both theoretical and experimental results show stable cycling and excellent rate performance. Notably, silicene exhibits superior quantum capacitance compared to graphene. Despite these advantages, practical deployment is still hindered by synthetic and structural stability challenges.

Electronic Devices

Silicene has been predicted to have the QSH effect in previous studies.[ 100 ] As a QSH‐based quantum mechanical switch, a topological insulator field‐effect transistor can be controlled via topological phase transitions, enabling on and off switching based on the presence or absence of topological edge states.[ 13 ] These states, including non‐trivial and trivial ballistic QSH modes, can determine the topological phase of the material. Compared with traditional solid‐state dielectrics (breakdown field is 0.7 eV nm−1), the critical field required for silicene is only 0.05 eV nm−1 to undergo a topological phase transition.[ 6 ] In addition, materials with stronger SOC will lead to a higher operating temperature, making the critical electric field relatively high. The intermediate SOC possessed by silicene (1.55 meV)[ 100 ] makes it a better candidate for topological insulator field‐effect transistors. To realize topological insulator field‐effect transistors (TI‐FETs) based on silicene, both scalable membrane fabrication and strain‐responsiveness are essential. Martella et al. reported a complete transfer process to obtain bendable silicene and silicene–stanene heterostructure membranes from Ag(111)/mica substrates by using mechanical delamination and flexible substrate attachment as shown in Figure 7d.[ 92 ] These membranes were subjected to uniaxial strain using a custom‐built three‐point bending apparatus (Figure 7e), allowing in situ Raman measurements under controlled deformation. The Raman spectra of multilayer silicene–stanene heterostructures displayed a clear redshift with increasing strain (Figure 7f), with a peak shift rate reaching −7.7 cm−1 per percentage (Figure 7g). Silicene's QSH effect and low critical field enable topological phase switching, offering promise for TI‐FETs. Its moderate SOC supports potential room‐temperature operation. Recent advances in flexible membrane fabrication and strain‐controlled Raman tuning demonstrate its structural responsiveness. Nonetheless, scalable synthesis and robust edge‐state retention remain key challenges for device integration.

Biomedical Fields

Silicene and its derivatives have also shown interesting performance in the biomedicine field. Lin et al. proposed the application of the silene‐based materials they synthesized in oncology medicine.[ 81 ] In their study, the degradation performance of silicene was investigated and compared with other inorganic nano agents, and it was found that silicene has unique absorption properties and excellent photothermal conversion efficiency in the near‐infrared (NIR) region, making it a strong candidate for photothermal cancer therapy. Silicene nanosheets modified by bovine serum albumin are biocompatible and can induce apoptosis of breast cancer cells in mouse experiments under near‐infrared laser irradiation. Another study obtained silicene @ Pt composite nanosheets by in‐situ generation and growth. The surface was modified with organic soy phospholipids (SP) to improve biocompatibility. The synthesized silicene @ Pt‐SP exhibits near‐infrared light absorption in the ultraviolet visible spectrum.[ 101 ] In order to further explore its photothermal conversion performance, an 808 nm laser with different power densities was irradiated, and the photothermal conversion efficiency of silicene @ Pt‐SP (30.1%) was calculated to be higher than that of Cu9S5 (25.7%) and bismuth sulfide nanorods (28.1%).[ 101 ] Silicene and its composites exhibit strong NIR absorption and high photothermal conversion efficiency, showing promise for cancer therapy. Modified with proteins or phospholipids, they demonstrate good biocompatibility and tumor ablation effects in vivo. Notably, silicene @ Pt‐SP achieves 30.1% conversion efficiency, surpassing other nanomaterials. However, practical biomedical translation requires further assessment of safety, degradation, and delivery.

3.2.2. Germanene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

Germanene was predicted to have the same buckled honeycomb lattice structure as silicene in 2009.[ 32 ] Laboratory synthesis of germanene was initially attempted using the MBE method on the surface of Ag (111). However, due to the strong interaction between germanene and the Ag (111) surface, complex interactions occur between Ge atoms and Ag surface atoms, which may even form surface alloys or induce significant lattice distortions.[ 83 ] Dávila et al. selected Au (111) substrate, which was also a noble metal, and successfully obtained germanene by the MBE method. The method used in this experiment is similar to the steps they reported for the synthesis of silicene,[ 79 ] and a similar growth process resulted in a √3 × √3 reconstructed germanene layer on a √7 × √7 Au (111) supercell.[ 83 ] The STM image of germanene obtained at a growth temperature of 200 °C is shown in Figure 8a. Germanene exhibits a clear and nearly flat honeycomb structure. The simulated STM image of germane is shown in Figure 8b, and the simulation results confirm the reliability of the molecular structure of the synthesized germanene.[ 83 ] The researchers also reported the atomic structure of germanene on the surface of Au (111), as shown in Figure 8c. In the same year, another research group successfully synthesized germanene on a Pt (111) surface using the MBE method.[ 84 ] It is worth noting that the annealing process in the range of 600–750 K was used here to prevent the formation of Ge‐Pt surface alloy during synthesis. Through low‐energy electron diffraction and STM observations, germanene has a hexagonal honeycomb structure and an undulation of ≈0.6 Å. Combined with the DFT calculation results, the formation of germanene nanomaterials was confirmed. More substrates, for example, Al, hexagonal aluminum nitride (AlN), Cu, and beyond have been used for epitaxial growth synthesis of germanene, expanding the possibility for this controlled synthesis and integration into functional devices.[ 102 , 103 , 104 ]

Figure 8.

Atomic imaging and electronic structure of Germanene for topological applications. a) STM image of germanene honeycomb superstructure, the inset is part of close‐up STM image, black represents the unit cell of germanene; b) Comparison of experimental STM (top) and simulated STM (bottom) images of germanene; c) Left: Top and side view of germanene structure on Au (111) surface; Right: Simulated STM image of germanene on Au (111) surface. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence.[ 83 ] Copyright 2014, IOP Publishing Ltd. d) STM image revealing the honeycomb lattice of germanene with zigzag edges; e) dI/dV spectra showing edge‐localized conductance peaks within the topological gap; f) Spatial map of the edge state, confirming continuous conduction along the ribbon boundary. Reproduced under the terms of the CC‐BY‐NC‐ND.[ 105 ] Copyright 2025, Dennis J. Klaassen et al.

Synthesis—Top‐Down Method

Although large pieces of germanium crystallize in a diamond cubic structure and cannot be exfoliated directly, the Zintl‐phase CaGe2 has layered and wrinkled Ge− sheets, which are separated by Ca2⁺ ions. This makes top‐down methods possible. One work utilized this structural feature of Zintl‐phase CaGe2. First, high‐purity Ge and Ca were reacted in a vacuum through high‐temperature reactions to prepare CaGe2. A chemical displacement reaction was then carried out between hydrochloric acid and CaGe2 to replace calcium atoms with hydrogen atoms, generating germanane (hydrogenated germanene). Then, through the mechanical exfoliation method, germanane was exfoliated from the bulk crystal into thin sheets. Finally, these thin sheets were subjected to thermal annealing treatment in an argon atmosphere to remove hydrogen atoms and thereby transform into germanene.[ 85 ] The thickness of the germane sheets after annealing was uniformly reduced by approximately 40%. This is consistent with the interlayer spacing of germanene (≈3.2 Å) and that of germanane (5.5 Å). Meanwhile, the thickness of the entire thin sheet varies uniformly, and the surface of the thin sheet is smooth, which further supports the annealing process and retains the 2D structure and preeminent crystallinity of the germanene sheet.

Properties and Potential Applications of Germanene—Energy Storage

The 2D properties of germanene make it as promising as silicene in the field of energy storage.[ 95 ] Germanene has been shown to have a hexagonal structure[ 79 ] and strongly layered properties (with a repeat period of 3.2 Å) that make it have a large specific surface area. The property of a large surface area allows a high concentration of Na+ to be inserted into germanene.[ 106 ] Liu et al. also measured that germane nanosheets had an initial discharge capacity of 695 mAh g−1 at a current density of 0.1 A g−1, outperforming other germanium‐based materials such as GeH (490 mAh g−1) and Ge particles (296 mAh g−1). In terms of initial Coulomb efficiency, germanene also showed superior performance at 60.8%, compared to 48.8% for GeH and 49.6% for Ge particles. At the same time, the 2D ultra‐thin nanostructure of germanene can effectively promote the transport of electrons and ions, shorten the diffusion path of Na+, and accelerate the absorption of Na+.[ 107 ] Germanene shows promising potential for sodium‐ion storage due to its high surface area and Na⁺ mobility, with initial electrochemical validation; however, practical integration remains limited by stability, synthesis scalability, and long‐term performance assessments.

Properties and Potential Applications of Germanene—Electronic Devices

Germanene nanoribbons offer a unique platform for next‐generation topological quantum devices owing to their intrinsic SOC and robust edge states. Their potential is rooted in their atomically precise structure and symmetry, as revealed by high‐resolution scanning tunneling microscopy.[ 105 ] Figure 8d presents an atomic‐resolution STM image showing the low‐buckled honeycomb lattice of a germanene nanoribbon with zigzag edge termination, a structural motif known to support topologically protected edge modes. Functionally, these edge states manifest as prominent conductance features in local tunneling spectra. As demonstrated in Figure 8e, a clear peak in the differential conductance (dI/dV) spectrum appears at ≈30 meV when the STM tip probes the nanoribbon edge, confirming the existence of a localized state within the bulk bandgap. And its bulk region remains in an insulated state, which is exactly as expected based on the characteristics of topological insulators. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of these states as visualized in Figure 8f, reveals a continuous signal running along the nanoribbon edges, indicative of 1D topological channels with dissipationless transport characteristics. Such properties position germanene nanoribbons as highly attractive candidates for ultra‐compact quantum circuits, where arrays of parallel edge channels can be harnessed to build high‐density quantum interconnects. It is worth noting that when the bandwidth is reduced to approximately 2.6 nm or less, the system undergoes a dimensional transformation: one‐dimensional edge states disappear, and zero‐dimensional end states with symmetry protection are generated.[ 105 ] Conceptually, this is similar to the Majorana zero mode. Germanene nanoribbons feature strong SOC and support tunable topological states, enabling dissipationless edge transport and potential use in quantum devices.

Recent studies reveal that twisted bilayer germanene can host electrically tunable quantum valley Hall states, thanks to its sizable spin–orbit coupling and intrinsic bandgap.[ 108 ] When the applied electric field exceeds a critical threshold, bandgap inversion occurs in AB/BA domains, giving rise to a triangular network of topologically protected 1D channels. This controllable valley‐protected transport lays the groundwork for a novel type of robust and low‐dissipation quantum valley Hall transistor. Germanene integrates tunable topological states into both edge‐confined and moiré‐modulated transport scenarios, offering versatile platforms for quantum circuitry. Its strong spin‐orbit coupling property enables the formation of stable and lossless channels, and it also has the ability to be controlled by an electric field. This is more advantageous than graphene without a band gap. Nonetheless, ambient instability, nanoscale twist control, and integration challenges constrain practical deployment. However, experimental verifications such as atomic‐level resolution edge patterns and field‐induced band inversion have further confirmed the technical feasibility of this technology. These findings collectively indicate that germanene is expected to be an ideal material for manufacturing compact, low‐power, and topologically protected quantum devices.

Properties and Potential Applications of Germanene—Biomedical Fields

Germanene also has good biocompatibility and light absorption capacity in the NIR region. A hydrogel functionalized composite based on germanene was used by Feng et al. to explore its potential applications in drug delivery.[ 109 ] Doxorubicin was loaded in germanene‐hydrogel to test the drug release behavior. Upon NIR radiation, the drug was successfully released triggered by the localized temperature rise resulting from the strong NIR absorbance of germanene, and antibacterial effects were also observed.

3.2.3. Stanene

Synthesis—Bottom‐Up Method

The first experimental synthesis of stanene, another Xenes in group IVA, was achieved using the MBE method. In this experiment, MBE method successfully grew stanene films on Bi2Te3 (111) substrates. High‐purity tin (99.999%) was deposited onto the Bi2Te3 (111) substrate at a rate of ≈0.4 monolayers per minute at room temperature.[ 86 ] The top and side views of the stanene lattice are shown in Figure 9a. Its surface matches the step and platform structure of the substrate and has a hexagonal honeycomb lattice structure as shown in Figure 9b. The hexagonal honeycomb structure of Stanene is bulking, and the height difference between the top and bottom Sn atoms is usually about 0.1 nm. Due to the compressive stress within the substrate and stanene film planes, as well as the presence of hydrogen adsorption during the growth process, stanene has a random height modulation of approximately 0.06nm. More substrates, such as InSb (111),[ 110 ] Ag (111),[ 111 ] Cu (111),[ 112 ] and PbTe (111),[ 113 ] were successfully used to grow stanene in further studies, providing a research basis for its further research and fabrication.

Figure 9.

Structural characterization and electrocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of Stanene. a) Lattice structure of stanene. Top view (upper) and side view (lower) where red shows the top Sn atoms and blue shows the bottom Sn atoms; b) STM image of stanine (top) and height line profile (bottom); Reproduced with permission.[ 86 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. c) TEM image of stanene; d) HR‐TEM image of stanene. Reproduced with permission.[ 27 ] Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry publication. e) Charging current density differences (ΔJ) versus scan rates for Sn nanosheets of varying thicknesses, used to calculate their electrochemical surface areas (ECSA); f) Faradaic efficiency (F.E.) for formate production as a function of applied potential for Sn nanosheets with different thicknesses; g) Long‐term CO2RR at −0.93 V reveals stable F.E. for HCOO− and H2 on stanine; Reproduced with permission.[ 114 ] Copyright 2025, John Wiley and Sons.

Synthesis—Top‐Down Method

Sn crystallizes in a body‐centered tetragonal structure at room temperature, forming a three‐dimensional metallic network that lacks any vdWs layered character. This prevents Sn from being directly exfoliated into 2D materials via top‐down methods. A method combining LPE with dealloying successfully synthesized stanine.[ 27 ] Ma et al. utilized a layered Li5Sn2 alloy synthesized by melting lithium and β‐Sn at 600 °C under argon. The alloy contains biatomic Sn layers separated by lithium, which can be selectively removed in aqueous solution, enabling the release of few‐layer stanene nanosheets via ultrasonic stripping. Figure 9c,d shows the transmission electron microscope (TEM) image and high‐resolution TEM (HR‐TEM) image of stanene obtained in the experiment.[ 27 ] The thickness of stanene is ≈4 nm, and its transverse dimensions are at the micrometer level. Stanene nanosheets have a lattice width of ≈0.29 nm, corresponding to the (200) lattice plane of the bulk tin.

Properties and Potential Applications of Stanene—Energy Storage

Although the theoretical capacitance of stanene (226 mAh g−1) is not as high as other group IVA Xenes like silicene, Mortazavi et al. conducted DFT calculations and found that the activation energy for Li diffusion in stanene is only 0.1 eV,[ 95 ] while that in silicene is 0.2 eV.[ 96 ] They also found that the existence of hollow sites in the hexagonal lattice of stanene makes the adsorption of Li stable and almost constant. Another study on the application of stanene in sodium‐ion batteries highlighted the significance of the hollow sites within stanene. The findings demonstrate that defects associated with these hollow sites can notably lower the activation energy of stanene after hydrogen passivation, thereby enhancing its Na+ storage capacity. This defective stanene can have a capacity of up to 272 mAh g−1.[ 115 ] Due to the limitations in the experimental synthesis of stanene, most related research to date has relied on the DFT calculations. However, the controlled synthesis of defective stanene has emerged as a promising direction for future energy storage applications.

Properties and Potential Applications of Stanene—Topological Insulators

Topological insulator materials have attracted much attention because of their unique electronic properties. In particular, the spin alignment of conductive electrons on the surface has attracted widespread attention in material science and condensed matter physics. The feasibility of low‐energy operation of non‐dissipative conductive edge states on the surface has also garnered considerable interest in these fields.[ 116 ] Earlier studies have shown that heavier elements are thought to have a stronger SOC effect.[ 100 , 117 ] The large mass of Sn atoms makes it represent a stronger SOC effect than materials such as graphene in group IVA. Hence, stanene is considered a good topological insulator. Theoretical studies based on first‐principal calculations have announced that the band gap of pure stanene is 0.1 eV, and after chemical functionalization (e.g., ─F, ─Cl, ─Br, ─I, and ─OH), the bandgap can be increased to 0.3 eV.[ 117 ] By changing the chemical functional groups, the topological properties of materials can be changed. Such modification can regulate the Fermi velocity of the edge state, and even the topological phase of the material can be qualitatively changed. External strains (such as compression or tension) can also regulate the band inversion and QSH state, which makes it possible to regulate QSH insulators experimentally. Through functionalization and strain engineering, stanene's topological characteristics can be precisely modulated, enabling bandgap opening and control over QSH states. While these strategies highlight its potential for room‐temperature applications, translating such tunability into robust, scalable devices remains an open challenge.

Properties and Potential Applications of Stanene—Catalytic Field