Abstract

Background

Occupational exposure to inhalable aerosols and airborne particles in the food production industry is associated with an increased risk of respiratory diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This study aims to investigate the inflammatory potential of inhalable aerosols collected from various food production environments and work tasks by assessing the concentrations of cytokines using an in vitro assay.

Methods

The inflammatory response, as measured by the production of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12, was determined using human macrophages derived from THP-1 monocytic cells. These cells were exposed to inhalable aerosol samples from 12 dry powder food processing plants. Cytokine concentrations were quantified using a Luminex assay.

Results

This study identified statistically significant variations in in vitro cytokine responses across different production types and work tasks, emphasizing the diverse inflammatory potential of workplace aerosols. Furthermore, a dose-dependent relationship was observed for TNF-α, IL-8, IL-2, and IL-1β, suggesting that aerosol mass plays a role in immune activation. After normalizing cytokine concentrations to aerosol mass, variations in the intrinsic potential of aerosols were observed, indicating that aerosols generated during dry powder food production have differing capacities to induce an inflammatory response.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the inflammatory potential of inhalable aerosols collected from various food production environments can be assessed by measuring cytokine concentrations using an in vitro assay. Although cytokine concentrations were generally low, weighing and mixing food ingredients, and environments like coffee, spice, and powdered consumer product production, and bakeries exhibited elevated concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, potentially indicating a higher risk for workers in these settings.

Keywords: in vitro model, macrophage-like cells, occupational exposure, personal sampling

What’s Important About This Paper?

This study presents a detailed investigation of the inflammatory responses elicited by occupational aerosols using a macrophage-like THP-1 cell model. By measuring the concentrations of 8 selected cytokines, the study provides a comprehensive analysis of the bioactivity of inhalable aerosols encountered in powder food manufacturing environments and insights into the potential health risks associated with occupational exposure to inhalable aerosols in the food industry.

Introduction

The food industry presents a significant occupational health challenge due to the diversity in food production processes and the release of aerosols and airborne particles during various processing stages. Estimates suggest that 10% to 25% of occupational asthma and rhinitis cases are directly attributable to workplace exposure to these food-related airborne particles (Kogevinas et al. 2007). These aerosols often comprise a complex mixture of inflammatory agents, including proteins, endotoxins, and microbial byproducts, which pose substantial respiratory hazards to workers (Tsai and Liu 2009; van der Walt et al. 2013; Baatjies et al. 2015).

Inhalation of these agents can elicit an inflammatory response in the respiratory tract, primarily mediated by innate immune cells such as macrophages. These cells recognize inhaled substances through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors, which activate downstream signaling pathways (Abbas 2021). Activation of transcription factors like nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and inflammasome pathways leads to the secretion of key inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and IL-8 (Abbas 2021). Chronic exposure to such inflammatory aerosols can result in sustained activation of these pathways, contributing to the development of occupational respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and occupational asthma (Tarlo and Malo 2013; Dumas et al. 2019).

In vitro testing of complex samples using appropriate cell cultures can offer valuable insights into biological responses triggered by co-exposure to multiple stressors present in bioaerosol mixtures. The THP-1 cell line, derived from human monocytic leukemia, serves as a widely used model for studying macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Differentiated THP-1 cells are capable of recognizing and responding to inflammatory stimuli, enabling the investigation of cytokine secretion and inflammasome activation under controlled experimental conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated that lipopolysaccharides (LPS), a major component of gram-negative bacterial endotoxins, activate inflammatory pathways in THP-1 cells, with responses further intensified by co-exposure to other inflammatory agents (Lim et al. 2017). Similarly, exposure to fungal species has been shown to induce TNF-α and IL-1β secretion in waste sorting environments (Viegas et al. 2020a). Other studies have shown how organic dust from different occupational environments leads to distinct expression profiles of cytokines like TNF-α and IL-8 in swine feed industry, poultry feed industry, slaughterhouse, and poultry production (Viegas et al. 2017b).

The aim of this study was to investigate the inflammatory response of inhalable aerosols collected from different food production environments and work tasks, focusing on their ability to trigger cytokine secretion in THP-1 cells. By measuring selected cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12, the relationship between the inhalable aerosols in different occupational settings and the occurrence of inflammatory responses was investigated.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was conducted between February 2022 and May 2023, encompassing 12 different food processing plants. The selected facilities included a variety of powder food processing operations such as baking, powdered consumer product production, coffee production, confectionery and chocolate production, chips, nuts, and snacks production, spice production, and sweet spread (eg chocolate) production. A total of 146 workers (101 males and 45 females) from various work tasks were recruited for participation. Work tasks with potential aerosol exposure were identified and chosen in collaboration with the occupational safety and health management/manager at each production facility.

Sampling procedure

Participants voluntarily wore personal sampling equipment during their regular 8-h work shifts. The sampling durations varied between 120 and 510 min, with an average sampling time of 431 min.

Inhalable aerosols were collected using a GSP inhalable aerosol sampler (GSA Messgerätebau, Ratingen, Germany), which was equipped with a 37-mm diameter polyvinyl chloride (PVC) filter with a 5 µm pore size. The sampler was connected to a Casella APEX 2 Pro air sampling pump, operating at an air flow rate of 3.5 L/min.

Each participant carried a backpack containing one GSP sampler attached to the left shoulder strap and positioned within their breathing zone. The air sampling volumes were determined by measuring air flow rates before and after shift using a Bios Defender 510-M primary air flow meter (Bios International Corp., New York, United States).

Gravimetrical determination

The particulate mass on each filter was determined using gravimetric analysis, following the method previously described by Darbakk et al. (2024). The mass limit of detection (LOD) was defined as 3 times the SD of 6 unused filters, which was calculated to be 0.024 mg per filter. This is equivalent to 0.02 mg/m3 for a sampling duration of 431 min at an airflow rate of 3.5 L/min.

Endotoxins in air determination

Endotoxins in air were sampled on a 25 mm glass fiber filters (GF/A, Whatman, United Kingdom) with 1.6 µm pore size mounted in PAS-6 filter cassette using a GSA SG5200 air sampling pump (GSA Messgerätebau GmbH) at an air flow rate of 2.0 L/min. Exposed filters were transferred to pyrogen-free glass tubes and extracted in 5 mL endotoxin-free water with 0.05% Tween 20 by orbital shaking for 1 h. Subsequently, the suspensions were centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 15 min, 2 mL of the suspension was transferred to new pyrogen-free glass tubes, and the centrifugation step was repeated. One milliliter of the final suspension was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. Prior to the application of the limulus amebocyte (LAL) kinetic-QCL assay (Loza Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) as recommended by the manufacturer, the sample material was diluted 20 times. Each sample, along with the blank and controls spiked at (50 EU/mL), were analyzed simultaneously. Endotoxin concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically (BioTek Instruments Inc., Vermont, United States) in reference to a 5-point standard curve ranging from 0.005 to 50 EU/mL. The LOD was 0.5 EU/filter for samples that were diluted 20 times. This corresponds to 0.5 EU/m3 at a sampling time of 480 min and an airflow rate of 2.0 L/min.

Filter extraction

Filters were extracted in 3 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were roughly vortexed and sonicated for 5 min, followed by orbital shaking at 500 rpm for 1 h and centrifugation at 4850 ×g for 10 min. The filter extract samples were stored at −20 °C prior to further analysis.

In vitro experiments

Maintenance of cell cultures.

THP-1 cells purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia, United States) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco; Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Pen–Strep, product no. 15070063, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged every 2 to 3 d at a density of 3 to 5 × 105 cells/mL.

Differentiation and exposure of THP-1 cells.

To induce differentiation into macrophage-like cells, approximately 800 000 THP-1 cells/mL were seeded in 75 cm2 culture flasks and treated with 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 72 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Following differentiation, non-adherent cells were removed, and the adherent macrophage-like THP-1 cells were gently washed with medium, followed by 24-h rest period in PMA-free medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After rest, differentiated cells were seeded into 48-well plates at approximately 200 000 cells/well, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were then exposed to filter extracts in duplicates for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After exposure, cell supernatant was harvested, and duplicates were pooled and aliquoted. Aliquots that were not used immediately were stored at −80 °C for further analyses.

Measure of cytokines in THP-1 cells exposed to filter extract by multiplex LUMINEX assay.

The concentrations of biomarkers in cell supernatant from exposed THP-1 cells were analyzed using a multiplex human magnetic Luminex assay (R&D Systems Inc., Minnesota, United States) with the following analytes included in the assay: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12 (p70). Cell supernatant samples were diluted 1:2 with the Calibrator Diluent RD6-52 provided in the kit, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each sample was run as duplicates. Analysis was performed using a Luminex® xMAP INTELLIFLEX single reporter analyzer (R&D Systems Inc.). The concentrations of analytes were quantified using a 7-point standard reference curve. Positive and negative controls, as well as blank samples, were included in each experiment.

The LOD for each analyte, including IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12(p70), and TNF-α, was defined as 3 times the SD of 6 unexposed THP-1 differentiated cell samples responses for the respective analyte in the Luminex assay. The LOD’s in pg/mL were as follows: IL-1β (1.5), IL-2 (2.0), IL-4 (29.3), IL-6 (2.1), IL-8 (2.1), IL-10 (5.2), IL-12 (p70) (20.3), and TNF-α (1.3).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using version 4.2.3 of R/RStudio (R Core Team 2023), with the rstatix, lmer, and ggplot2 packages (Wickham 2016; Kuznetsova et al. 2017; Kassambara 2023). The normality of inhalable aerosol and cytokine data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro et al. 2007). Since the assumption of normality was not met, the data were log-transformed prior to analysis.

The non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to perform statistical comparisons of cytokine concentrations between production types and work tasks (Rey and Neuhäuser 2011). For analytes below the LOD, values were imputed with random values between 0.001 and LOD prior to conducting generalized linear mixed-effects model analyses. Additionally, cytokine concentrations were normalized to aerosol mass (mg) to evaluate the effect of the aerosol in relation to the amount that was present on the respective filter.

Generalized linear mixed-effects models were employed to evaluate the impact of production environments and work tasks on cytokine concentrations, both normalized and not normalized for inhalable aerosol mass. Repeated measurements per participant were included as random effects to account for within-subject variability.

The effects of production type and work tasks on non-normalized cytokine concentrations were assessed using the following models:

To evaluate the inflammatory potential of aerosols independent of mass, cytokine concentrations were normalized for inhalable aerosol mass. The following models were used:

Results

Personal exposure measurements

In total, 206 personal full-shift samples were collected in the 12 different food production plants. Due to sampling errors, 12 samples were discarded, resulting in 194 valid samples.

Table 1 summarizes the median, minimum, and maximum concentrations of inhalable aerosols across various food production types. The median inhalable aerosol concentration for bakery products was 1.2 mg/m3, ranging from 0.1 to 11 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 6.0 mg/m3). In the cake and baking ingredients category, the inhalable aerosol median was 1.6 mg/m3, with a range of 0.1 to 5.1 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 3.0 mg/m3). The median inhalable aerosol concentration for coffee production was lower at 0.4 mg/m3, with concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 4.4 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 2.4 mg/m3). Confectionery and chocolate production had a median inhalable aerosol concentration of 0.9 mg/m3, ranging from 0.1 to 8.6 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 2.8 mg/m3). Powder consumer products had a median inhalable aerosol concentration of 1.3 mg/m3, ranging from 0.1 to 27 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 7.4). For snacks, nuts, and chips, inhalable aerosol concentrations were among the lowest, with a median of 0.2 mg/m3 (range: 0.1 to 0.7 mg/m3, 90th percentile: 0.6 mg/m3). In the spice production environment, the median inhalable aerosol concentration was relatively high at 3.1 mg/m3, ranging from 0.5 to 10 mg/m3 (90th percentile: 7.5 mg/m3). Finally, sweet spread production showed the highest median inhalable aerosol concentration at 6.2 mg/m3 (range: 1.2 to 9.4 mg/m3, 90th percentile: 9.0 mg/m3).

Table 1.

Summary of concentrations of inhalable aerosol across different production types, including medians, minimum, maximum, and 90th percentiles.

| Production type | Inhalable aerosol (mg/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | Min | Max | P90 | |

| Bakery products | 55 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 11 | 6.0 |

| Cake and baking ingredients | 9 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 5.1 | 3.0 |

| Coffee | 8 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 2.4 |

| Confectionery and chocolate | 35 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 8.6 | 2.8 |

| Powder consumer products | 60 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 27 | 7.4 |

| Snacks, nuts and chips | 10 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Spice | 13 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 10 | 7.5 |

| Sweet spread | 4 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 9.4 | 9.0 |

Endotoxin concentrations across production types and workstations: results from random stationary measurements

Random stationary measurements of endotoxin concentrations, expressed in EU/m3, showed variations across different production types and workstations (Supplementary Table S1). It is important to emphasize that these results are based on a limited number of random measurements and therefore only provide an indication of endotoxin presence in these work environments.

The lowest endotoxin concentration was observed in bakery production, specifically at the weighing and mixing station, where a concentration of 1.7 EU/m3 was measured. In contrast, the snacks, nuts, and chips production line, near the weighing station for seasoning, exhibited a wider range of concentrations with a median of 64 EU/m3, ranging from 5.7 to 121 EU/m3. Confectionery and chocolate production showed low endotoxin concentration of 6.0 EU/m3 at the production line. In powder consumer products, endotoxin concentrations varied significantly between workstations. The residual component station recorded the highest concentration, at 180 EU/m3, while the blending machine room showed a lower concentration of 22 EU/m3. The discharge of final products had the lowest concentration in this sector, at 2.1 EU/m3. In cake and baking ingredient production, particularly at the weighing and mixing station, the median concentration was 51 EU/m3, with a range of 2.2 to 99 EU/m3. In sweet spread production, measured at the powder ingredient filling station, endotoxin concentrations were more consistent, with a median of 18 EU/m3 (range: 15 to 21 EU/m3). Furthermore, one random measurement at a coffee bean delivery workstation showed a notably higher endotoxin concentration of 840 EU/m3.

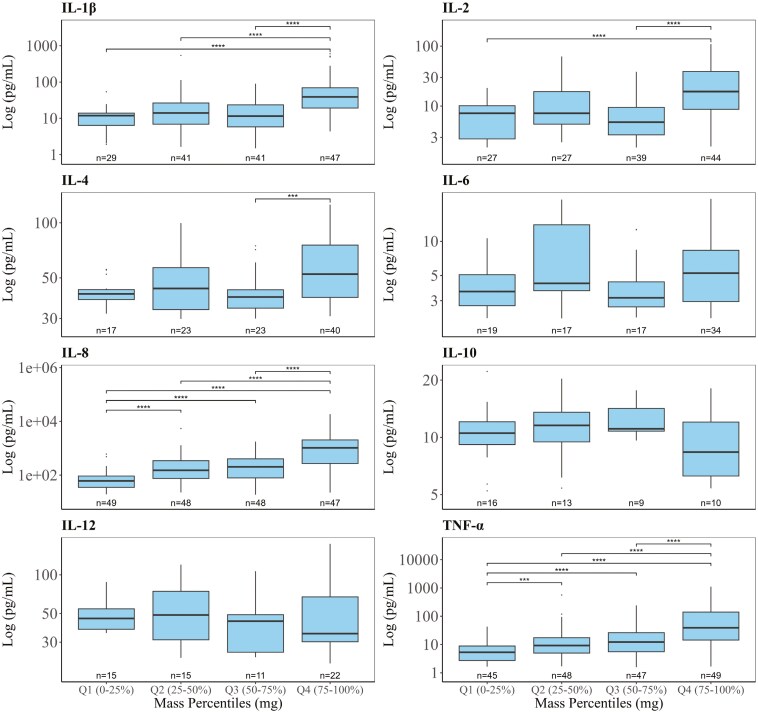

Distribution of cytokine concentration across mass quartiles

The PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were exposed to filter extracts from the personal inhalable aerosol samples collected during food production to investigate if the collected inhalable aerosols induced an inflammatory response. In the inflammatory response analysis, the proportion of samples below the LOD was as follows: TNF-α (3%), IL-1β (19%), IL-2 (30%), IL-8 (1%), IL-4 (47%), IL-6 (55%), IL-10 (75%), and IL-12 (68%).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of cytokine concentrations across quartiles of inhalable aerosol mass (mg). Cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, and TNF-α) above their respective LODs are displayed in panels, grouped into quartiles Q1 to Q4. The results revealed variations in cytokine concentrations across aerosol mass quartiles, providing insight into potential dose-dependent inflammatory effects. The cytokine concentrations generally increased across quartiles, with significant trends observed for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-2. These cytokines demonstrated a dose-dependent increase, with higher aerosol mass associated with higher cytokine concentrations in the differentiated THP-1 cells. Notably, IL-8 showed the most pronounced increases in concentration, with significant differences across all quartiles (P < 0.0001). IL-4 showed only a significant increase in concentration between Q3 and Q4, while IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12 displayed less consistent trends, suggesting they were less strongly influenced by the aerosol mass.

Fig. 1.

Dose–response relationship of log-transformed cytokine concentrations (log-transformed pg/mL) across inhalable aerosol mass (mg) percentiles. Inhalable aerosol mass is categorized into 4 quartiles. Q1 represents the lowest 0–25th percentile, Q2 the 25–50th percentile, Q3 the 50–75th percentile, and Q4 the highest 75–100th percentile. Each panel represents a different cytokine (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, and TNF-α). Boxplots show the median and interquartile range of cytokine concentrations within each mass percentile, with black dots representing potential outliers. Wilcox statistical significance is denoted by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Comparative analysis of production environments and work tasks

To evaluate potential differences in induced inflammatory responses across various production environments and work tasks, the results from the in vitro experiments were first grouped according to the production environment. Figure 2 shows the log-transformed concentrations of the inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α across different food productions, including bakery products, coffee, powder consumer products, spices, cake and baking ingredients, confectionery and chocolate, snacks, nuts and chips, and sweet spread. Figure 2 presents only cytokines above their respective LODs. Notably, bakery products and coffee consistently showed higher cytokine concentrations compared to other production environments. For IL-1β, bakery products, spices, and powder consumer production showed significantly higher concentrations compared to snacks, nuts and chips, and confectionery and chocolate production. IL-4, IL-6, and IL-2 were also significantly higher in bakery products compared to confectionery and chocolate production. IL-8 and TNF-α exhibited the most pronounced differences, with bakery products, powder consumer products, and spices showing statistically significant higher concentrations than other production environments.

Fig. 2.

Log-transformed cytokine concentrations (IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) across different food production environments, including bakery products, coffee, powder consumer products, spices, cake and baking ingredients, confectionery and chocolate, snacks, nuts and chips, and sweet spreads. Wilcox statistical significance is denoted by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

To further explore if there were any differences in the induced inflammatory response, the results were regrouped according to specific work tasks within these food production environments. Figure 3 shows the log-transformed concentrations of cytokines across different work tasks, including baking and cooking, grinding and milling, material handling, production line operations, and weighing and mixing. Weighing and mixing had significantly higher IL-1β concentrations compared to production line operations and material handling. Figure 3 presents only cytokines above their respective LODs. IL-4, IL-2, and IL-6 concentrations were significantly higher in weighing and mixing compared to production line operations. IL-8 concentrations were significantly elevated in weighing and mixing compared to other tasks, such as material handling and production line operations. TNF-α concentrations were highest in weighing and mixing, with significant differences observed compared to material handling and production line operations. These findings indicate that weighing and mixing are associated with elevated cytokine concentrations, demonstrating potential differences in inflammatory responses across work tasks.

Fig. 3.

Log-transformed cytokine concentrations (IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) across different work tasks, including baking and cooking, grinding and milling, material handling, production line operations, and weighing and mixing. Wilcox significant differences between work tasks are denoted by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Generalized linear mixed-effect analyses

Analysis of the impact of production types on cytokine concentrations.

Air samples induced varying inflammatory responses in the differentiated THP-1 cells across diverse food production environments. A mixed-effects analysis was performed to investigate the impact of production type on these responses. Table 2 presents the effect of production type on log-transformed cytokine concentrations, with bakery production as the reference category. Before accounting for aerosol mass, several cytokines showed significantly lower concentrations in confectionery and chocolate, snacks, nuts, and chips, and powder consumer products compared to bakery production. For example, TNF-α concentrations were lower in these environments, with similar reductions observed for IL-1β, IL-8, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-4. These results suggest that bakery production generally elicited higher cytokine responses compared to other production types when the raw data were considered. Random-effects analyses revealed moderate participant-level variability, with fixed effects explaining a moderate proportion of the variance (Marginal R2) and combined fixed and random effects explaining substantially more (Conditional R2).

Table 2.

Generalized linear mixed-effect model analysis of the impact of production type (reference: bakery production) on log-transformed cytokine concentrations (pg/mL) of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-2, and IL-12. Coefficients and P-values are presented for each predictor, with significant associations highlighted in bold. Random intercepts were included to account for variability between participants.

| Predictors | TNF-α | IL-1β | IL-8 | IL-2 | IL-6 | IL-4 | IL-10 | IL-12 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | |

| Intercept | 3.295 | <0.001 | 2.916 | <0.001 | 5.793 | <0.001 | 1.951 | <0.001 | 0.798 | <0.001 | 3.221 | <0.001 | 0.562 | 0.003 | 2.786 | <0.001 |

| Production type (ref. “bakery products”) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cake and baking ingredients | −0.307 | 0.547 | −0.549 | 0.399 | −0.116 | 0.826 | −0.178 | 0.755 | −0.001 | 0.999 | −0.382 | 0.353 | 0.658 | 0.193 | −0.180 | 0.675 |

| Coffee | −0.253 | 0.629 | −0.811 | 0.229 | −0.263 | 0.629 | −0.061 | 0.918 | 0.052 | 0.912 | 0.109 | 0.798 | −0.048 | 0.927 | 0.025 | 0.956 |

| Confectionery and chocolate | −2.122 | <0.001 | −2.160 | <0.001 | −2.013 | <0.001 | −1.225 | <0.001 | −0.597 | 0.028 | −0.529 | 0.032 | 0.559 | 0.066 | −0.082 | 0.751 |

| Powder consumer products | −0.860 | 0.001 | −0.714 | 0.034 | −0.653 | 0.017 | −0.541 | 0.067 | −0.144 | 0.537 | −0.080 | 0.704 | 0.560 | 0.033 | −0.161 | 0.472 |

| Snacks, nuts, and chips | −1.696 | <0.001 | −1.893 | 0.002 | −1.673 | 0.001 | −1.138 | 0.031 | −0.779 | 0.065 | −0.535 | 0.157 | 0.502 | 0.283 | −0.296 | 0.472 |

| Spice | −0.045 | 0.932 | 0.391 | 0.541 | 0.711 | 0.181 | −0.475 | 0.382 | −0.229 | 0.579 | 0.323 | 0.417 | 0.570 | 0.234 | −0.314 | 0.394 |

| Sweet spread | −0.378 | 0.628 | −0.560 | 0.566 | −0.312 | 0.695 | −0.474 | 0.575 | −1.133 | 0.087 | −0.400 | 0.514 | −0.235 | 0.753 | −1.895 | 0.002 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.94 | 2.03 | 1.18 | 1.78 | 1.28 | 0.87 | 1.43 | 1.42 | ||||||||

| τ00 identifier | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.19 | |||||||||

| N identifiers | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | ||||||||

| Observations | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.274/0.578 | 0.195/0.415 | 0.266/0.521 | 0.085/0.267 | 0.052/0.165 | 0.051/0.276 | 0.043/0.220 | 0.050/NA | ||||||||

To address potential bias caused by differences in aerosol mass across production environments, cytokine concentrations were normalized to aerosol mass on the respective filter. This adjustment accounts for the fact that some production environments, such as bakery production, were associated with relatively higher aerosol exposure compared with other production environments. Normalizing the data allowed for a more direct comparison of the biological response relative to the amount of aerosol present, as presented in Supplementary Table S2.

When the data were normalized for aerosol mass, the observed patterns shifted significantly. For example, coffee production, which had lower total aerosol exposure, showed significantly higher cytokine responses per unit of aerosol compared to bakery production, with increased normalized concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12. Similarly, snacks, nuts, and chips production also demonstrated higher normalized concentrations of IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12. In contrast, confectionery and chocolate production and sweet spread production, which initially showed lower cytokine concentrations, exhibited even greater reductions in normalized cytokine concentrations, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, relative to bakery production. Normalization to aerosol mass emphasizes the relative potency of the aerosols from each environment, highlighting environments like coffee production and snacks production as having stronger biological effects per unit mass, even if their total cytokine concentrations were lower in the non-normalized data. Conversely, environments with larger aerosol masses but weaker responses, such as confectionery and chocolate and sweet spread production, showed reduced cytokine responses after normalization.

Analysis of the impact of work tasks on cytokine concentrations.

Air samples induced varying cytokine responses in the differentiated THP-1 cells across different work tasks. A mixed-effects analysis was conducted to assess the impact of specific work tasks on these responses. Table 3 summarizes the results of the linear mixed-effects regression analysis, which evaluated the effect of work tasks on log-transformed cytokine concentrations, with baking and cooking as the reference category.

Table 3.

Generalized linear mixed-effect model analysis of the impact of work tasks (reference: baking and cooking) on log-transformed cytokine (pg/mL) of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-2, and IL-12. Coefficients and P-values are presented for each predictor, with significant associations highlighted in bold. Random intercepts were included to account for variability between participants.

| Predictors | TNF-α | IL-1β | IL-8 | IL-2 | IL-6 | IL-4 | IL-10 | IL-12 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | Estimates | P | |

| Intercept | 3.117 | <0.001 | 2.995 | <0.001 | 5.920 | <0.001 | 1.487 | 0.004 | 0.779 | 0.011 | 3.358 | <0.001 | 0.607 | 0.192 | 2.904 | <0.001 |

| Work task (ref. “baking and cooking”) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cleaning | 0.155 | 0.888 | 0.122 | 0.928 | 0.189 | 0.862 | 0.911 | 0.457 | −0.103 | 0.884 | 0.347 | 0.694 | −0.201 | 0.859 | 0.083 | 0.931 |

| Delivery | 2.157 | 0.027 | 1.992 | 0.115 | 1.879 | 0.055 | 2.107 | 0.070 | 1.519 | 0.026 | 0.864 | 0.293 | 1.292 | 0.215 | 0.346 | 0.720 |

| Grinding and milling | −0.249 | 0.717 | −0.979 | 0.285 | −0.459 | 0.512 | −0.194 | 0.818 | −0.020 | 0.967 | −0.642 | 0.282 | −0.107 | 0.887 | −0.531 | 0.446 |

| Material handling | −0.607 | 0.203 | −0.845 | 0.173 | −0.815 | 0.090 | −0.135 | 0.812 | 0.001 | 0.997 | −0.203 | 0.614 | 0.833 | 0.104 | −0.383 | 0.415 |

| Packing | −2.314 | 0.002 | −1.907 | 0.052 | −2.042 | 0.007 | −0.785 | 0.381 | −0.737 | 0.161 | −1.089 | 0.088 | 0.358 | 0.657 | −0.394 | 0.598 |

| Production line operations | −1.479 | 0.001 | −1.956 | 0.001 | −1.850 | <0.001 | −0.540 | 0.326 | −0.296 | 0.358 | −0.642 | 0.100 | 0.334 | 0.499 | −0.366 | 0.424 |

| Storage | −0.876 | 0.267 | −0.728 | 0.467 | −1.312 | 0.097 | −0.557 | 0.543 | −0.451 | 0.398 | −0.657 | 0.315 | 0.735 | 0.377 | −0.318 | 0.671 |

| Weighing and mixing | 0.237 | 0.603 | 0.182 | 0.761 | 0.273 | 0.553 | 0.590 | 0.284 | 0.171 | 0.596 | 0.007 | 0.987 | −0.038 | 0.938 | −0.110 | 0.811 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.97 | 2.10 | 1.06 | 1.82 | 0.66 | 0.87 | 1.36 | 1.48 | ||||||||

| τ00 identifier | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.21 | |||||||||

| N identifiers | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 | ||||||||

| Observations | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.299/0.549 | 0.261/0.388 | 0.367/0.560 | 0.118/0.248 | 0.096/0.186 | 0.094/0.265 | 0.067/0.266 | 0.016/NA | ||||||||

Compared to baking and cooking, packing and production line operations consistently showed significantly lower concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8. Specifically, packing was associated with significantly lower concentrations of TNF-α (P = 0.001) and IL-8 (P = 0.007). Similarly, production line operations showed significantly lower concentrations of TNF-α (P = 0.001), IL-1β (P = 0.001), and IL-8 (P < 0.001). In contrast, delivery was the only task linked to significantly higher cytokine concentrations than baking and cooking. Delivery showed significantly higher concentrations of TNF-α (P = 0.027) and IL-6 (P = 0.026). There were also trends toward higher concentrations of IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-2 in delivery tasks, although these did not reach statistical significance. Other work tasks, including weighing and mixing, storage, material handling, and cleaning, did not show significant differences in cytokine concentrations relative to baking and cooking. Random-effects analysis revealed intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) ranging from 0.10 to 0.36. This suggests that individual differences moderately contributed to the observed variability in cytokine responses across work tasks.

Variations in inflammatory cytokine responses across departments in a food production facility

Since there were indications of differences in the induced inflammatory response in the differentiated THP-1 cell line across production environments and work tasks, it was of interest to investigate whether such differences could also be observed within a single food production facility. The powder consumer product production facility was chosen due to the relatively large number of samples (n = 60). The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines were analyzed to explore differences across departments (A, B, and C) and seasons (summer and autumn, data not shown). Statistically significant differences were observed for IL-1β between department A and B, for IL-4 between A and C, and for IL-8 between A and B and A and C. Seasonal differences were also identified, with significant differences during summer for IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β between A and B, as well as for IL-4 between A and C. Once the data were adjusted for aerosol mass, further distinctions became noticeable (Supplementary Fig. S1). Notable differences were found for IL-10 and IL-4 between groups A and B and B and C, along with IL-6 between A and B and IL-12 between B and C. Meanwhile, the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, and IL-8 transitioned from being the highest in department B to being elevated in departments A and C, although these changes were not statistically significant.

Discussion

The present study investigated the inflammatory response induced in vitro by extracts from personal inhalable aerosol samples collected from different workplaces (bakery production, cake and baking ingredients production, coffee production, confectionery and chocolate production, snacks, nuts, and chips production, spice production, and sweet spread production) and work tasks (material handling, weighing and mixing, grindings and milling, production line operations, and baking and cooking), where workers are exposed to inhalable aerosols.

Macrophages were chosen for the in vitro assessment because they are known to be responsible for first-line protection and for triggering the inflammatory response via secretion of signaling molecules (Abbas 2021). Monocytic THP-1 cells, a well-established model for studying macrophage function, have been widely used to investigate the inflammatory potential of various agents (Daigneault et al. 2010; Chanput et al. 2014; Viegas et al. 2017b). Numerous studies have utilized the THP-1 model to evaluate the inflammatory and immunomodulatory potential of food-derived compounds. For example, food-grade titanium dioxide (E171), commonly used in confectionery and baked goods, was shown to significantly increase TNF-α and IL-6 secretion and impair THP-1 macrophage differentiation, indicating a proinflammatory effect at physiologically relevant doses (Zagal-Salinas et al. 2024). Similarly, β-glucans derived from oat, barley, and shiitake were reported to mildly upregulate inflammation-related gene expression (eg IL-1β, IL-8, IL-10, NF-κB) in THP-1 macrophages, with their immunomodulatory activity influenced by molecular structure and composition (Chanput et al. 2012). Additional studies have shown that curcumin and piperine found in spices modulate mTORC1 signaling, leading to reduced cytokine production and polarization toward an anti-inflammatory M0 phenotype (Kaur and Moreau 2021), while flaxseed-derived linusorbs effectively suppressed LPS-induced proinflammatory mediators through NF-κB pathway inhibition (Zou et al. 2020). These studies have investigated the inflammatory responses in THP-1 cells caused by specific food ingredients or components. However, in the present study, we utilized this cell model to examine the impact of aerosols collected from occupational settings in various powder food industry environments on the production of selected inflammatory cytokines.

A mass-based dose-dependent increase in inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1β, IL-8, IL-2, and TNF-α) was observed in THP-1 macrophage-like cells exposed to aerosols from various workplaces and tasks (Fig. 1). This suggests that higher aerosol concentrations elicit stronger immune responses. However, cytokines such as IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12 displayed more variable expression patterns across different production environments (Fig. 2; Table 2) and work tasks (Fig. 3; Table 3). Specifically, aerosol samples from bakeries, coffee, spice, and powder consumer product production demonstrated significantly higher concentrations of inflammatory cytokines compared to samples from confectionery and chocolate, and snacks, nuts, and chips manufacturing. This suggests that aerosols in certain food production environments may harbor bioactive components capable of eliciting stronger immune responses.

Furthermore, work tasks involving weighing, mixing, and baking resulted in elevated inflammatory cytokine concentrations compared to those associated with grinding, milling, and production line operations. When the cytokine concentrations were normalized to aerosol mass, a notable difference in the intrinsic inflammatory potential of aerosols from different production environments was observed. For instance, coffee production, despite having lower relative aerosol exposure, exhibited significantly higher cytokine responses per unit of aerosol mass compared to bakery production. This normalization to aerosol mass emphasizes the relative potency of aerosols, indicating that environments such as coffee and snacks production might have pronounced biological effects, even when total cytokine concentrations appear lower in non-normalized data.

Moreover, significant variations in cytokine concentrations were observed even within the same production facility, indicating that aerosols are not uniform across different departments. As an example, different departments within a factory that produced powder consumer products displayed considerable differences in the measured concentrations of IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α in the in vitro experiments (Fig. 4). These discrepancies might be due to task-specific exposures and the unique aerosol compositions associated with different work processes. Notably, when normalized for aerosol mass, Departments A and C exhibited a greater potential to induce inflammation compared to Department B, suggesting that certain aerosol components may pose a higher risk than others, even within the same facility (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given the variability in aerosol-induced inflammatory responses, conducting task-specific and department-specific risk assessments is warranted. Tailored safety measures, such as localized ventilation systems, task-specific personal protective equipment, and modifications of the work processes, could mitigate exposure risks for workers in the food industry.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of log-transformed inflammatory cytokine concentrations (pg/mL) in differentiated THP-1 cells exposed to air samples from departments A, B, and C within a powder consumer product production facility. Wilcox significant differences in mean cytokine concentrations are indicated by asterisk (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.05, and *P < 0.05). The sample sizes (n) for each department are shown below each plot.

Aerosols present in the food processing industry can comprise a mixture of inorganic and organic components sourced from both animal and plant origins (Kennedy et al. 1998). These aerosols could include microbial bioactive substances such as LPS, peptidoglycans, β-glucans, fungal antigens, and proteins that may have either irritant or allergenic effects. Prior research has indicated that organic dust present in bakeries, alongside coffee and spice manufacturing, can harbor endotoxins, fungi, and mycotoxins (Sakwari et al. 2013; Viegas et al. 2017a; Viegas et al. 2020b), where the endotoxin in bakery flour has been associated with respiratory issues due to inflammatory or irritant processes (Cho et al. 2011; Olivieri et al. 2013). Although stationary air sampling confirmed the presence of endotoxins in specific areas, these measurements were random and may not fully represent daily variations in exposure or reflect individual workers’ personal exposure concentrations.

Elevated concentrations of cytokines across different production environments, departments, and work tasks indicate potential risks of inflammation and respiratory diseases due to aerosol exposure. Increases in IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, and IL-4, observed during material mixing (Fig. 3; Table 3), in Department B of powder consumer production (Fig. 4), and in spice production (Fig. 2; Table 2), might indicate acute inflammation, neutrophil recruitment, bronchial hyperreactivity, and potential tissue damage (Akdis et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2016). Specifically, IL-6 and TNF-α might indicate acute inflammatory responses, IL-1β and IL-8 may reflect inflammasome-driven neutrophilic inflammation, IL-4 may be associated with allergic reactions, while IL-2 might signal adaptive immune activation, potentially increasing the risk of airway remodeling and fibrosis. In both coffee production (Fig. 2; Table 2) and Department C of powder consumer production (Fig. 4), increased concentrations of IL-6 and IL-12 might indicate acute inflammatory responses and a Th1-skewed immune activation, potentially posing risks of tissue damage, fibrosis, and chronic respiratory diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis and allergic asthma (Akdis et al. 2016). Additionally, coffee production is associated with elevated IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12, demonstrating a combination of allergic reactions, attempts at inflammation resolution, and an increased risk of long-term tissue damage. Despite IL-10’s anti-inflammatory role, its concurrent elevation alongside proinflammatory cytokines might indicate inadequate inflammation control, potentially increasing the likelihood of chronic respiratory disorders. This cytokine profile across production environments, work tasks, and departments indicates that aerosol exposure in these settings might contribute to both acute and chronic inflammation, increasing the risk of long-term respiratory health issues among workers.

While this study provides important insights into the inflammatory responses induced by airborne particulates from various powder food industry production environments and work tasks, there are some limitations that should be considered. First, the use of a single cell line, THP-1 macrophage-like cells, may not fully capture the complexity of the in vivo inflammatory response. Future studies should consider the use of primary human macrophages or a combination of different cell types to better represent the physiological conditions. In particular, the inclusion of lung epithelial cell lines, either alone or in co-culture with macrophages, would enhance the physiological relevance of the model and provide a more comprehensive assessment of aerosol-induced inflammatory responses. Additionally, the current study focused on the measurement of a limited set of cytokines. Expanding the analysis to include a broader panel of inflammatory mediators, chemokines, and signaling molecules could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, the proportion of values below the LOD should be considered when interpreting results for several of the cytokines. This may introduce bias or reduce the reliability of findings, particularly for cytokines with a high percentage of undetectable values (IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12). Furthermore, the study did not investigate the specific chemical composition and physical characteristics of the airborne particulates in the personal samples. In addition, the use of PBS for extracting aerosol particulates may have limited the solubilization of hydrophobic compounds, some of which could possess proinflammatory or biologically active properties. This could have led to an underestimation of the overall inflammatory potential. Future studies could explore the use of alternative or complementary extraction methods, such as organic or mixed-solvent systems, to capture a broader range of aerosol constituents. The random stationary measurements of endotoxin might not fully represent the personal samples and workers exposure to endotoxin. Future research should explore the relationship between the characteristics of the airborne particles and their inflammatory potential, which could inform the development of more targeted control measures. Lastly, this study assessed only a single exposure scenario, which may have overlooked potential dose–response effects. Variability in aerosol particle mass across samples could have influenced results, as higher aerosol mass might overwhelm the cellular system, potentially skewing the observed responses. Despite these limitations, the present study provides valuable insights into the potential health risks associated with exposure to aerosols in the powder food industry.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that the inflammatory potential of inhalable aerosols collected from various food production environments can be assessed by measuring cytokine concentrations using an in vitro assay. This assay revealed statistically significant differences in cytokine responses across production types, departments and work tasks, demonstrating the variability in the inflammatory potential of workplace aerosols. Additionally, a dose-dependent increase with aerosol mass was observed for 4 of the selected cytokines, indicating that the aerosol mass influenced immune activation.

The results, normalized for mass, indicate that aerosols from different workplaces may exhibit varying reactivity, suggesting that the composition of inhalable aerosol samples is not uniform. This underscores the potential benefits of identifying specific bioactive components in aerosols within the powder food industry. Further investigation of aerosol components, such as endotoxins, fungi, mycotoxins, or allergens, and conducting longitudinal studies of the immune responses in exposed workers would provide deeper insights.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Annals of Work Exposures and Health online.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants and manufacturing facilities for their ongoing cooperation and for enabling the successful execution of this research. We also appreciate Øyvind Skare at STAMI for assisting us with the statistical analysis.

Contributor Information

Christine Darbakk, National Institute of Occupational Health, Gydas vei 8, Majorstuen, 0363 Oslo, Norway; Department of Community Medicine and Global Health, Institute of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Kirkeveien 166, 0450 Oslo, Norway.

Raymond Olsen, National Institute of Occupational Health, Gydas vei 8, Majorstuen, 0363 Oslo, Norway.

Solveig Krapf, National Institute of Occupational Health, Gydas vei 8, Majorstuen, 0363 Oslo, Norway.

Pål Graff, National Institute of Occupational Health, Gydas vei 8, Majorstuen, 0363 Oslo, Norway.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute of Occupational Health (STAMI), Norway.

Conflict of interest

The authors affirm that there is no conflict of interest concerning the material presented in this Article. All opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- Abbas AK. 2021. Cellular and molecular immunology. 10th ed. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Akdis M, et al. 2016. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor β, and TNF-α: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 138:984–1010. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baatjies R, Meijster T, Heederik D, Jeebhay MF.. 2015. Exposure-response relationships for inhalant wheat allergen exposure and asthma. Occup Environ Med. 72:200–207. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/oemed-2013-101853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanput W, Mes JJ, Wichers HJ.. 2014. THP-1 cell line: an in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int Immunopharmacol. 23:37–45. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanput W, et al. 2012. β-Glucans are involved in immune-modulation of THP-1 macrophages. Mol Nutr Food Res. 56:822–833. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mnfr.201100715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, et al. 2011. Effect of Toll-like receptor 4 gene polymorphisms on work-related respiratory symptoms and sensitization to wheat flour in bakery workers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 107:57–64. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.anai.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault M, et al. 2010. The identification of markers of macrophage differentiation in PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS One. 5:e8668. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0008668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbakk C, Graff P, Olsen R.. 2024. Assessment of occupational exposure to inhalable aerosols in an instant powdered food manufacturing plant in Norway. Safety Health Work. 15:360–367. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.shaw.2024.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas O, et al. 2019. Association of occupational exposure to disinfectants with incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US female nurses. JAMA Network Open. 2:e1913563. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A. 2023. rstatix: pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Moreau R.. 2021. Curcumin steers THP-1 cells under LPS and mTORC1 challenges toward phenotypically resting, low cytokine-producing macrophages. J Nutr Biochem. 88:108553. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2020.108553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, et al. 1998. Respiratory health hazards in agriculture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 158:S1–S76. https://doi.org/ 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_1.rccm1585s1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogevinas M, et al. 2007. Exposure to substances in the workplace and new-onset asthma: an international prospective population-based study (ECRHS-II). Lancet. 370:336–341. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61164-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB.. 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw. 82:1–26. https://doi.org/ 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K-Y, Ito K, Maneechotesuwan K.. 2016. Inflammation to pulmonary diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2016:7401245. https://doi.org/ 10.1155/2016/7401245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S-G, Kim J-K, Suk K, Lee W-H.. 2017. Crosstalk between signals initiated from TLR4 and cell surface BAFF results in synergistic induction of proinflammatory mediators in THP-1 cells. Sci Rep. 7:45826. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep45826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri M, et al. 2013. Wheat IgE profiling and wheat IgE levels in bakers with allergic occupational phenotypes. Occup Environ Med. 70:617–622. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/oemed-2012-101112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2023. R: a language and environment for statistical computing version 4.2.3. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rey D, Neuhäuser M.. 2011. Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. In: Lovric M, editor. International encyclopedia of statistical science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 1658–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Sakwari G, et al. 2013. Personal exposure to dust and endotoxin in Robusta and Arabica coffee processing factories in Tanzania. Ann Occup Hyg. 57:173–183. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/annhyg/mes064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SS, et al. 2007. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52:591–611. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlo SM, Malo J-L; Fourth Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace Participants. 2013. An Official American Thoracic Society Proceedings: work-related asthma and airway diseases. Presentations and discussion from the Fourth Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace. Ann Am Thoracic Soc. 10:S17–S24. https://doi.org/ 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-119ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M-Y, Liu H-M.. 2009. Exposure to culturable airborne bioaerosols during noodle manufacturing in central Taiwan. Sci Total Environ. 407:1536–1546. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt A, Singh T, Baatjies R, Lopata AL, Jeebhay MF.. 2013. Work-related allergic respiratory disease and asthma in spice mill workers is associated with inhalant chili pepper and garlic exposures. Occup Environ Med. 70:446–452. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/oemed-2012-101163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas C, et al. 2017a. Fungal contamination in green coffee beans samples: a public health concern. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 80:719–728. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15287394.2017.1286927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas S, et al. 2017b. Cytotoxic and inflammatory potential of air samples from occupational settings with exposure to organic dust. Toxics. 5:8. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/toxics5010008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas C, et al. 2020a. The effects of waste sorting in environmental microbiome, THP-1 cell viability and inflammatory responses. Environ Res. 185:109450. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas C, et al. 2020b. Occupational exposures to organic dust in Irish bakeries and a pizzeria restaurant. Microorganisms. 8:118. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/microorganisms8010118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org [Google Scholar]

- Zagal-Salinas AA, et al. 2024. Food grade titanium dioxide (E171) interferes with monocyte-macrophage cell differentiation and their phagocytic capacity. Food Chem Toxicol. 192:114912. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fct.2024.114912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X-G, et al. 2020. Flaxseed orbitides, linusorbs, inhibit LPS-induced THP-1 macrophage inflammation. RSC Adv. 10:22622–22630. https://doi.org/ 10.1039/c9ra09058d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.