ABSTRACT

Background

Gut‐directed hypnotherapy is effective for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and a few studies have reported long‐lasting therapeutic effects following intervention. No previous studies have evaluated the long‐term effects of nurse‐administered hypnotherapy.

Aims

We aimed to investigate the long‐term effects of nurse‐administered gut‐directed hypnotherapy for IBS and identify factors associated with symptom improvement. Furthermore, we aimed to compare treatment effects between individual and group hypnotherapy.

Methods

A 2‐year follow‐up study including 289 patients with IBS who had completed a 12‐week hypnotherapy program (individually or in groups) was conducted. Data were collected at baseline, and at 6‐month‐, 1‐year‐ and 2‐year follow‐ups. Irritable bowel syndrome and extracolonic symptom severity (IBS‐SSS), gastrointestinal‐specific anxiety (VSI), and anxiety and depressive symptoms (HADS) were assessed. Patients reporting a reduction ≥ 50 points (IBS‐SSS) were classified as treatment responders.

Results

The 2‐year follow‐up was completed by 207 patients. The proportion of responders at post‐treatment was 64.3%, 62.8% at the 6‐month follow‐up, 64.7% at the 1‐year follow‐up, and 61.8% at the 2‐year follow‐up. The severity of IBS symptoms, extracolonic and psychological symptoms were all reduced post‐treatment, and this effect lasted over the 2‐year follow‐up period (p < 0.001). Younger age, individual hypnotherapy, and severe irritable bowel syndrome symptoms at baseline predicted a better response to treatment (R 2 = 0.16).

Conclusions

Nurse‐administered gut‐directed hypnotherapy is an effective treatment for IBS with long‐lasting symptom improvements. Younger age, severe irritable bowel syndrome symptoms, and individual treatment might be important factors associated with effectiveness (ClinicalTrials.gov study protocol IDs: NCT06167018, NCT03432078).

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov study protocol IDs: NCT06167018, NCT03432078

Keywords: extracolonic symptom, gut‐brain axis, hypnotherapy, irritable bowel syndrome, nurse, psychological treatment

1.

Summary.

-

Summarise the established knowledge on this subject

-

◦

Gut‐directed hypnotherapy is an effective and safe treatment that improves IBS symptoms, psychological distress, and quality of life.

-

◦

A previous study showed that when combining nurse‐led hypnotherapy and group sessions, treatment availability is improved without losing significant treatment effects.

-

◦

A few previous studies report long lasting effects of gut‐directed hypnotherapy, but there is a need for further evaluation.

-

◦

-

What are the significant and new findings of this study

-

◦

This study investigated the long‐term effects of nurse‐led gut‐directed hypnotherapy delivered either individually or in groups. Treatment was based on the North Carolina protocol; patients received either 8 or 12 sessions.

-

◦

The results show that the majority of patients stayed symptom improved after treatment up to 2 years regardless of therapy format or whether the longer or shorter course was used.

-

◦

Participants who received hypnotherapy in an individual format reported slightly better long‐term effects compared with those who received group hypnotherapy.

-

◦

A greater IBS symptom burden at baseline and younger age were associated with a better treatment response, suggesting that this treatment could be beneficial early in the course of the disorder.

-

◦

2. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder with an estimated global prevalence of 4% and a female predominance [1]. It is defined as a disorder of gut‐brain interaction (DGBI), formerly known as functional gastrointestinal disorder, and is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain in association with altered bowel habits such as constipation, diarrhea, or both [2]. Although the pathophysiology of IBS is only partially understood and probably varies among individuals, research supports the view that bidirectional gut‐brain interactions influenced by both physiological and psychological factors play a major role [3, 4]. The prevalence [5] as well as the severity [6, 7] of anxiety and depression is higher in IBS patients than in healthy individuals [8]. Overall, IBS patients tend to have a lower QOL than patients with other chronic conditions [9].

The treatment of IBS focuses on relieving symptoms and optimizing QOL. The recommended therapeutic options include explanation and reassurance, pharmacological treatment options targeting the predominant symptoms, dietary advice, and brain‐gut behavioral therapies [10]. A large proportion of patients with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms need pharmacological treatment. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of drug therapy is not optimal, and many patients continue to suffer from IBS symptoms despite the use of medications. For these patients, a combination of therapeutic interventions including brain‐gut behavioral therapies can be effective [11].

Gut‐directed hypnotherapy for IBS was demonstrated to be effective by the Manchester group in the 1980s [12]. Since then, a few long‐term follow‐up studies reporting therapeutic effects lasting several years after the end of treatment have been published [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Although gut‐directed hypnotherapy is considered safe and effective for treating IBS [18], it is not widely available and therefore not accessible to all patients. Conventionally, gut‐directed hypnotherapy has been provided at highly specialized research centers by psychologists or psychotherapists. The development of standardized protocols [19] has enabled other healthcare professionals to administer the treatment and a few studies on nurse‐led gut‐directed hypnotherapy have reported positive results [20, 21, 22]. This alternative can potentially increase the availability and cost‐effectiveness of the treatment. Also, gut‐directed hypnotherapy has traditionally been provided on an individual basis, but there are now results supporting group hypnotherapy as a non‐inferior alternative [17, 23, 24, 25].

Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate the long‐term effects of nurse‐administered gut‐directed hypnotherapy. Our main focus was to evaluate the improvement of IBS symptoms, but we also investigated the effects on extracolonic symptoms, GI‐specific anxiety, and psychological distress. Furthermore, we compared individual versus group‐administered hypnotherapy, and 8 versus 12 sessions of individual hypnotherapy, and explored which factors were associated with changes in treatment outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Recruitment and Study Participants

Patients with IBS symptoms refractory to standard medical treatment were consecutively recruited between September 2005 and August 2019 at a combined clinical and research gastroenterology outpatient clinic specialized in DGBI at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. Two cohorts of patients were included in the follow‐up study: patients who received hypnotherapy as part of their clinical treatment and were monitored within a clinical audit between 2005 and 2019, and patients who received hypnotherapy in a randomized controlled trial at the same location between 2011 and 2016, comparing individual and group hypnotherapy [24]. All patients had been referred to the unit by general practitioners or gastroenterologists. Recruitment to hypnotherapy was made by two gastroenterologists (MS and HT) who also confirmed the IBS diagnosis with a detailed medical history and, when necessary, additional investigations. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1. Signed written informed consent |

| 2. Age ≥ 18 years |

| 3. IBS according to the Rome II, III, or IV criteria (depending on which criteria were used during the time of inclusion) |

| 4. Basic knowledge of Swedish and ability to comply with the study procedure |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1. Other diseases that could affect gastrointestinal symptoms |

| 2. Severe psychiatric disease (e.g., severe depression or psychosis) |

| 3. Pregnancy or trying to become pregnant during the treatment period |

| 4. Recent or ongoing life crisis such as the loss of a close family member or divorce |

| 5. Ongoing participation in another clinical trial |

| 6. Previous experience of gut‐directed hypnotherapy |

| 7. Changes in medical treatment of relevance for IBS symptoms during the last month (3 months for patients included in the RCT) |

All participants signed a written informed consent before the study inclusion. The study was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (diary numbers 686‐11 and 636‐12).

3.2. Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy

All participants underwent a 12‐week gut‐directed nurse‐administered hypnotherapy program but the number of hypnotherapy sessions and the treatment modality (i.e., individual or group hypnotherapy) differed during different time points, from 2005 to 2011, every patient received 12 sessions of individual hypnotherapy. In 2011, the number of sessions was reduced from 12 to 8 for feasibility. Since the results from our randomized controlled trial (performed between 2011 and 2016) showed that group‐administered hypnotherapy had comparable positive outcomes to individual therapy [24], from then on all the following patients were treated with group hypnotherapy. Treatment was based on the North Carolina Hypnotherapy Protocol consisting of 7 sessions [19]; but, as indicated above, for the first clinical patients who received 12 sessions, 5 extra sessions were added. One of the extra sessions was later used in the final 8‐session program. Each hypnotherapy session normally lasted 30–40 min. Patients also received an audio file with a hypnotic exercise which they were instructed to use daily throughout the treatment period.

For more details about the treatment, please see Supporting Information S2.

3.3. Assessment

Demographic (age, sex) and clinical (IBS subtype based on the predominant bowel habit) information were collected at baseline before treatment initiation. Participants were also assessed for primary and secondary outcomes (see below) at baseline, directly after the last session (post‐treatment), at 6‐month follow‐up, 1‐year follow‐up, and 2‐year follow‐up via self‐report questionnaires in paper form.

3.3.1. Questionnaires and Outcome Measures

The IBS severity scoring system (IBS‐SSS) [26, 27], the visceral sensitivity index (VSI) [28, 29], and the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) [30] questionnaires were used (for details, see Supporting Information S2). The primary endpoint was the change in IBS symptom severity (IBS‐SSS) over a 2‐year period in relation to baseline values. The proportion of responders to the intervention at each time point was assessed. A responder was defined as a participant who had a reduction of IBS‐SSS ≥ 50 relative to baseline [26].

Secondary endpoints were changes in extracolonic symptom severity (IBS‐SSS), GI‐specific anxiety (VSI), depressive symptoms (HADS), and general anxiety (HADS) over a 2‐year period, relative to baseline.

3.4. Data Analyses and Statistics

Per‐protocol analyses were performed to evaluate the long‐term effects of nurse‐administered gut‐directed hypnotherapy. The principle of the last observation carried forward was used for missing data at the 6‐month and 1‐year follow‐up time points. Participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires were considered study completers and those who did not were labeled as study non‐completers.

Subgroups with differences in the hypnotherapy protocol (individual vs. group, and 8 vs. 12 sessions) were compared to each other to investigate if there were differences in treatment response between the groups. Correlations between changes in the different types of symptoms and demographic (age, sex) and clinical (IBS subtype, severity, usage of audio file) data were analyzed as secondary outcomes.

3.4.1. Effectiveness of Treatment

Because no significant deviations from normality were identified, the change in symptoms over time was analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA. T‐tests and chi‐squared tests comparing baseline levels and post‐treatment responses of completers and non‐completers of the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires were conducted. For the t‐tests reported in Supporting Information S1: Tables 2 and 3, Hedge's g was interpreted in the traditional way (0.2 = small effect size, 0.5 = medium effect size, 0.8 = large effect size) [31].

3.4.2. Sub‐Group Analyses and Predictors of Change

We conducted mixed between‐within‐subjects ANOVA to compare treatment response in participants who had received individual versus group‐administered hypnotherapy and those who had 8 versus 12 sessions of individual therapy, respectively. Only participants who had completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires were included in the analyses. Pearson and point‐biserial correlation, and chi‐square tests were performed to investigate associations between baseline questionnaire data and changes in primary and secondary outcomes. Multiple linear regression was used for all baseline data regardless of whether these were bivariately associated with the outcome variable or not to further assess the ability of demographic and clinical baseline data to predict improvement in IBS symptoms at the 2‐year follow‐up. The reason for including all the variables in the regression analysis was the practical nature of this study and the importance of finding factors that can be relevant in a clinical context rather than only investigating their influence on treatment response independently.

Quantitative normally distributed data are presented as means with standard deviation. Categorical data are presented as proportions (percentages). Two‐tailed p values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with the IBM SPSS Statistics program, version 29.0.0.0.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

Out of the 368 patients who were assessed for eligibility, 289 completed the gut‐directed hypnotherapy program (i.e., missed no more than one session of their program). The 79 patients who were excluded from the study were so mainly because they did not complete the treatment but also because of other factors including medical or social reasons (e.g., moved away or was later diagnosed with another GI disease explaining the symptoms). A total of 207 participants completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires. Of these, 83 patients had been included in the RCT, and the other 124 patients received hypnotherapy as a part of their clinical management. The last observation carried forward technique was used for 17 to 28 patients at each time point for the different questionnaires. The flowchart for the study is presented in Figure 1. The demographic and clinical data for the participants were similar at each time point, as shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart demonstrating the number of participants who completed the IBS‐SSS questionnaires at every specific time point of the study and in which format they received the intervention. Study completer = completed the 2‐year follow‐up IBS‐SSS questionnaire; Study non‐completer = did not complete the 2‐year follow‐up IBS‐SSS questionnaire.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and clinical data for participants who completed the IBS‐SSS questionnaires at each time point from baseline to 2‐year follow‐up.

| Baseline | Post‐treatment | 6‐month follow‐up | 1‐year follow‐up | 2‐year follow‐up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 289 | 289 | 230 | 223 | 207 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.8 (13.2) | 40.8 (13.2) | 41.0 (13.2) | 42.3 (13.3) | 43.1 (13.5) |

| Age, range | 20–74 | 20–74 | 20–74 | 20–74 | 20–74 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 75 (26.0%) | 75 (26.0%) | 65 (28.3%) | 56 (25.1%) | 51 (24.6%) |

| Female | 214 (74.0%) | 214 (74.0%) | 165 (71.7%) | 167 (74.9%) | 156 (75.4%) |

| IBS subtype, n (%) | |||||

| IBS‐C | 67 (23.2%) | 67 (23.2%) | 53 (23%) | 50 (22.4%) | 52 (25.1%) |

| IBS‐D | 125 (43.3%) | 125 (43.3%) | 100 (43.5%) | 100 (44.8%) | 86 (41.5%) |

| IBS‐M | 97 (31.1%) | 97 (31.1%) | 77 (33.5%) | 73 (32.7%) | 69 (33.3%) |

Abbreviations: IBS‐C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS‐D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; IBS‐M, irritable bowel syndrome with mixed bowel habits.

4.2. IBS Symptoms

Improvement compared to baseline scores in overall IBS symptom severity was seen at all time points after treatment for the participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up (Table 3 and Figure 2). The reduction of symptoms was seen in all the five dimensions assessed by the IBS‐SSS questionnaire (i.e., abdominal pain severity and frequency, bloating severity, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and daily life interference from bowel symptoms) at all measured time points following hypnotherapy (p < 0.001 for all) (Supporting Information S1: Table 1 and Figure 2). There were no significant differences in baseline data or post‐treatment response between completers and non‐completers of the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires (Supporting Information S1: Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 3.

One‐way repeated measures ANOVA comparing outcomes in IBS symptom severity, extracolonic symptom severity, GI‐specific anxiety, depressive symptoms, and anxiety across time in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires.

| Baseline | Post‐treatment | 6‐month follow‐up | 1‐year follow‐up | 2‐year follow‐up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F | df (hypothesis, error) | p | Wilks' lambda | Partial eta squared | |

| IBS symptom severity | 306 (85) | 224 (108) | 220 (110) | 222 (107) | 227 (107) | 64.10 | 4, 203 | < 0.001 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| Extracolonic symptom severity | 190 (84) | 138 (88) | 141 (88) | 142 (90) | 147 (89) | 42.99 | 4, 203 | < 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| GI‐specific anxiety | 43.7 (15.3) | 33.4 (16.2) | 32.0 (16.5) | 31.3 (16.9) | 30.7 (16.7) | 53.04 | 4, 198 | < 0.001 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Depressive symptoms | 5.7 (3.9) | 4.7 (3.9) | 4.8 (3.9) | 4.4 (4.0) | 4.2 (3.6) | 12.61 | 4, 195 | < 0.001 | 0.80 | 0.21 |

| Anxiety | 9.2 (4.7) | 7.5 (4.0) | 7.6 (4.2) | 6.9 (4.2) | 7.2 (4.2) | 20.03 | 4, 195 | < 0.001 | 0.71 | 0.29 |

Note: IBS symptom severity = IBS‐SSS; Extracolonic symptom severity = IBS‐SSS extracolonic symptoms questionnaire; GI‐specific anxiety = VSI; Depressive symptoms = HADS, depression domain; Anxiety = HADS, anxiety domain. Bold values indicate statistically significant values.

FIGURE 2.

Repeated measures ANOVA's illustrating the change in IBS‐SSS severity score and dimensions (mean, SD) (a) IBS symptom severity, (b) Pain intensity, (c) Pain frequency, (d) Bloating severity, (e) Bowel habit dissatisfaction, (f) Daily life interference, from baseline to 2‐year follow‐up in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up IBS‐SSS questionnaire. ***p < 0.001.

A total of 133 patients (64.3%) were identified as responders at the end of the last session (post‐treatment). The responder rate was very similar at all follow‐up time points (range 61.8%–64.7%). Out of all study participants, 88 (42.5%) were classified as responders at all time points (Table 4). At follow‐up, the proportion of patients with severe IBS symptoms according to IBS‐SSS was reduced and more patients reported mild symptoms while some were in remission (Figure 3 and Supporting Information S1: Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Treatment response (IBS‐SSS) at all time points in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaire (n = 207).

| Responder | No change | Worsened | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n, (%) | n, (%) | n, (%) | |

| Post‐treatment | 133 (64.3%) | 62 (30%) | 12 (5.8%) |

| 6‐month follow‐up | 130 (62.8%) | 68 (32.9%) | 9 (4.3%) |

| 1‐year follow‐up | 134 (64.7%) | 59 (28.5%) | 14 (6.8%) |

| 2‐year follow‐up | 128 (61.8%) | 66 (31.9) | 13 (6.3%) |

| Continuous responder | 88 (42.5%) |

Note: Responder = participants with a reduction of ≥ 50 p in IBS‐SSS; No change = participants with less than ± 50 p change in IBS‐SSS; Worsened = participants with an increase ≥ 50 p in IBS‐SSS; Continuous responder = responder at all assessed time points.

FIGURE 3.

Proportions of IBS symptom severity levels at all time points in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires (n = 207).

4.3. Extracolonic and Psychological Symptoms

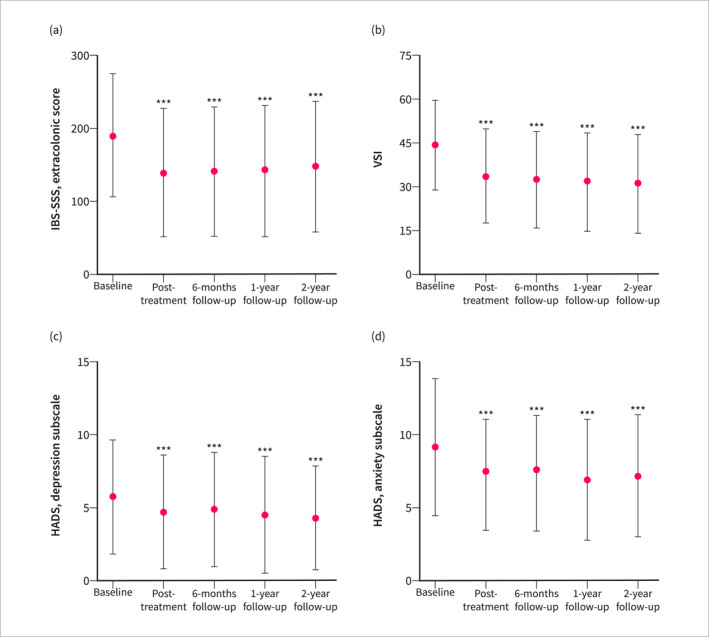

Extracolonic symptoms, GI‐specific anxiety, depressive symptoms, and anxiety also showed long‐lasting improvements in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up questionnaires. One‐way repeated measures ANOVAs showed sustained reductions in the severity of all extracolonic and psychological factors (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 3 and Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Repeated measures ANOVAs illustrating the change (mean, SD) in (a) Extracolonic symptom severity (n = 207), (b) GI‐specific anxiety (n = 202), (c) Depressive symptoms (n = 199), and (d) Anxiety (n = 199), from baseline to 2‐year follow‐up in participants who completed the 2‐year follow‐up IBS‐SSS questionnaires. IBS symptom severity = IBS‐SSS; Extracolonic symptom severity = IBS‐SSS, extracolonic symptoms; GI‐specific anxiety = VSI; Depressive symptoms = HADS, depression domain; Anxiety = HADS, anxiety domain. ***p < 0.001.

4.4. Comparisons Between Treatment Modalities

Mixed between‐within‐subjects ANOVAs comparing participants who received individual versus group‐administered hypnotherapy showed a small but statistically significant difference between the groups in the amount of change in IBS symptom severity (Wilks´ Lambda = 0.954, F (4, 202) = 2.429, p = 0.049, multivariate partial eta squared = 0.046) (Supporting Information S1: Table 5 and Figure 1). The percentage of responders tended to be larger for individual hypnotherapy at all time points compared with group‐administered hypnotherapy, and the proportion of patients who were continuous responders (i.e., responder at all time points) was higher for the patients who received individual hypnotherapy (Supporting Information S1: Table 6).

There were no differences between the participants who had received 8 versus 12 sessions of individual therapy regarding treatment effect on IBS symptoms, extracolonic symptoms, or psychological symptoms (Supporting Information S1: Table 7 and Figure 2).

4.5. Factors Associated With Change in Treatment Outcomes

Table 5 shows bivariate correlations between improvement at the 2‐year follow‐up and demographic and clinical data at baseline. The baseline IBS‐SSS score demonstrated a small positive correlation with the change in IBS symptoms (r = 0.25, p < 0.001), suggesting that more severe IBS symptoms at baseline were associated with a greater reduction in IBS symptom severity at the 2‐year follow‐up. Similar patterns were seen for extracolonic symptoms, GI‐specific anxiety, depressive symptoms, and anxiety. Age showed a small negative correlation with the change in IBS symptoms, extracolonic symptoms, and GI‐specific anxiety, indicating that younger age was associated with a greater reduction in symptom severity. Sex had a small negative association with depressive symptoms at the 2‐year follow‐up, suggesting that male patients showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms. Continuous usage of the audio file after treatment completion did not correlate with changes in symptom severity at the 2‐year follow‐up relative to baseline.

TABLE 5.

Correlations between improvement of symptoms at 2‐year follow‐up, audio tape usage after treatment, and demographic and clinical baseline data.

| Baseline | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Delivery (group, individual) | 8 or 12 sessions | Audio use after treatment | IBS symptoms | Extra‐colonic symptoms | GI‐specific anxiety | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety | IBS subgroup | |

| Change in symptoms | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | r, p | χ2 (df), p |

| IBS symptoms | −0.14, p = 0.05 | 0.10, p = 0.150 | 0.13, p = 0.071 | −0.01, p = 0.894 | 0.09, p = 0.208 | 0.25, p < 0.001 | 0.04, p = 0.577 | 0.05, p = 0.464 | −0.05, p = 0.485 | 0.05, p = 0.473 | 292.93 (312), p = 0.774 |

| Extracolonic symptoms | −0.17, p = 0.013 | 0.01, p = 0.847 | 0.03, p = 0.632 | −0.03, p = 0.626 | 0.02, p = 0.782 | 0.06, p = 0.375 | 0.27, p < 0.001 | 0.03, p = 0.630 | 0.05, p = 0.465 | 0.11, p = 0.108 | 325.83 (326), p = 0.492 |

| GI‐specific anxiety | −0.23, p = 0.001 | 0.08, p = 0.282 | 0.07, p = 0.298 | −0.04, p = 0.549 | 0.04, p = 0.584 | 0.06, p = 0.415 | 0.03, p = 0.626 | 0.33, p < 0.001 | −0.05, p = 0.437 | 0.19, p = 0.006 | 102.89 (116), p = 0.803 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.04, p = 0.549 | −0.21, p = 0.002 | 0.05, p = 0.487 | 0.03, p = 0.701 | 0.02, p = 0.746 | 0.08, p = 0.240 | 0.01, p = 0.937 | 0.08, p = 0.274 | 0.52, p < 0.001 | 0.21, p = 0.003 | 26.56 (36), p = 0.875 |

| Anxiety | −0.09, p = 0.212 | −0.09, p = 0.209 | 0.05, p = 0.528 | −0.02, p = 0.830 | 0.07, p = 0.327 | 0.11, p = 0.115 | 0.06, p = 0.372 | 0.19, p = 0.007 | 0.23, p = 0.001 | 0.54, p < 0.001 | 34.54 (42), p = 0.786 |

Note: IBS symptoms = IBS‐SSS; Extracolonic symptoms = IBS‐SSS extracolonic symptoms; GI‐specific anxiety = VSI; Depressive symptoms = HADS, depression domain; Anxiety = HADS, anxiety domain. Variable coding: sex (male = 0, female = 1); delivery (group = 0, individual = 1); number of sessions (8 sessions = 0, 12 sessions = 1); use of audios (no = 0, yes = 1). Bold values indicate statistically significant values.

Multiple linear regression was used to assess independent predictors of change in IBS symptom severity at the 2‐year follow‐up relative to baseline (Table 6). Younger age, receiving individual rather than group treatment, and reporting more severe IBS symptoms at baseline were independent and additive predictors of better response to treatment, together explaining 15.5% of the variance (R 2 = 0.155) in IBS severity at 2‐year follow‐up.

TABLE 6.

Multiple linear regression analysis for improvement in IBS symptom severity at 2‐year follow‐up relative to baseline.

| Variable | B | Beta | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −1.23 | −0.18 | 0.013 | −2.19 to −0.27 |

| Sex (male: 0, female: 1) | 17.82 | 0.09 | 0.225 | −11.04 to 46.68 |

| Delivery (group: 0, individual: 1) | 29.47 | 0.17 | 0.046 | 0.57 to 58.37 |

| Number of sessions (8 sessions: 0, 12 sessions: 1) | −29.19 | −0.14 | 0.095 | −63.45 to 5.07 |

| Audio use after treatment (no: 0, yes: 1) | 21.10 | 0.11 | 0.123 | −5.74 to 47.94 |

| Baseline | ||||

| IBS Symptoms | 0.37 | 0.36 | < 0.001 | 0.19 to 0.54 |

| Extracolonic symptoms | −0.15 | −0.15 | 0.08 | −0.33 to 0.02 |

| GI‐specific anxiety | −0.80 | −0.14 | 0.105 | −1.76 to 0.17 |

| Depressive symptoms | −2.81 | −0.12 | 0.137 | −6.52 to 0.90 |

| Anxiety | 2.08 | 0.11 | 0.212 | −1.20 to 5.37 |

Note: B: unstandardized coefficients, Beta: standardized coefficients, R 2 = 0.155. Bold values indicate statistically significant values.

5. Discussion

This follow‐up study aimed to investigate the long‐term efficacy of nurse‐administered gut‐directed hypnotherapy and to identify possible predictors of response to treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first long‐term follow‐up study to evaluate gut‐directed hypnotherapy administered by nurses. Compared with the original RCT [24], we see a similar proportion of responders in this follow‐up study, and this is stable at all timepoints. The sustained reduction in IBS symptom severity throughout the 2‐year follow‐up period supports the idea that gut‐directed hypnotherapy can have long‐lasting therapeutic effects in IBS for the majority of treated patients. Even though normal fluctuations regarding symptom burden often occur over time, a 5‐year follow‐up study on changes in IBS features found that IBS patients with a high mean gastrointestinal symptom severity respond poorly on average to standard treatment and tend to remain symptomatic over time [32]. This further strengthens the assumption that the long‐term symptom improvement seen in our patients with moderate to severe IBS symptoms is an actual effect of gut‐directed hypnotherapy. In addition, the treatment also reduced extracolonic symptoms, GI‐specific anxiety, and psychological distress. These results indicate that gut‐directed hypnotherapy can target a variety of symptoms observed in IBS patients and offers broad therapeutic benefits.

A statistically significant difference was found in the reduction of IBS symptom severity between individual and group‐administered hypnotherapy in favor of individually administered hypnotherapy. The rate of continuous responders was significantly higher in the cohort receiving individual therapy, but no significant difference was seen in the proportion of responders when only comparing the individual follow‐up time points. The delivery format was also not associated with improvement of IBS symptoms at the 2‐year follow‐up in the bivariate association and only contributed with a small effect on the prediction of this outcome in the regression analysis. These results differ somewhat compared to our original RCT, which specifically compared the efficacy of individual versus group hypnotherapy and found no differences [24]. The additional time perspective in this follow‐up study suggests that hypnotherapy has better long‐term outcomes in IBS when administered individually. Although the same hypnotherapy script was used during treatment, the individual treatment form could perhaps enable more room for personalized discussions with the therapist, as well as a stronger therapeutic alliance, which could have an impact on treatment effect. However, it is important to note that, overall, the findings in this study are not sufficient to recommend one delivery form over the other. Regarding the number of sessions, our study provided distinct conclusions. No difference was found between 8 and 12 sessions for any of the treatment outcomes. Fewer sessions could thus reduce treatment costs and enhance treatment feasibility, with the same effect on outcomes. Another recent report has come to similar conclusions, where 6 sessions were non‐inferior to 12 [33].

Concerning predictors of a positive response to treatment, two additional factors were found: age and baseline IBS symptom severity. Being younger was associated with a positive change in treatment outcomes regarding IBS symptoms, extracolonic symptoms, and GI‐specific anxiety. This is an interesting finding, given that most studies have not found any association between age and response to gut‐directed hypnotherapy in IBS [17, 25, 34]. Nevertheless, in line with our results, older age has been reported as a possible predictor of poorer efficacy of gut‐directed hypnotherapy in IBS in one study [16]. Studies of gut‐directed hypnotherapy in children and adolescents with DGBI have reported promising results, superior to many reports of hypnotherapy for adults [35, 36]. This evidence may relate to our finding, as younger adults may be more susceptible to hypnotherapy and benefit to a greater extent from this treatment than older adults due to the same mechanisms. Unhelpful IBS‐related cognitions and behaviors may not be as established in younger individuals compared with those who might have suffered from treatment‐refractory IBS for a longer time. However, contrasting evidence has also indicated that adults in the general population within the age range of 29–40 had lower hypnotic suggestibility than adults in the age range of 40 and above [37]. The underlying mechanisms explaining why differences in age groups regarding response to gut‐directed hypnotherapy remain unclear and should be explored further.

The most significant factor associated with IBS severity improvement was the baseline IBS severity score. Patients reporting more severe IBS symptoms prior to hypnotherapy showed a better treatment response, which implies that hypnotherapy may be more efficacious for patients with a higher symptom burden. Similar tendencies have been reported in other studies, such as a greater treatment response for secondary care patients compared to patients in primary care [23], better treatment response for patients with higher baseline IBS symptom burden [25], and a greater improvement in abdominal pain for patients with a high baseline IBS severity [34].

Some limitations of our study need to be considered. First, we did not include a control group. The efficacy of gut‐directed hypnotherapy, however, is already well‐established, and our aim was to evaluate any lasting changes after treatment rather than comparing the effect with another condition. Another limitation of our study was that most of the participants were not randomly assigned to group‐ or individual hypnotherapy but were simply allocated to the treatment form that was used in the clinical services during the time of treatment initiation. However, based on the existing evidence regarding treatment delivery, we do not believe that this had any major effect on the treatment outcome, and the number of patients who received individual or group hypnotherapy was similar for both treatment modalities. A third limitation is that this was a single‐center study, and the treatment was provided only by two nurses. This can influence the reproducibility of the findings outside of this setting. Lastly, we used the principle of Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) for missing data at the 6‐month and 1‐year follow‐up time points. Although this method has limitations, we used it for its simplicity and because of its wide use in clinical studies, which enables comparison with previous results.

Our study also presents several strengths. One is the use of standardized treatment protocols [19], which ensured treatment fidelity, the only difference being the number of sessions and the administration form. The relatively long follow‐up time is another strength and further confirms the long‐term effects of gut‐directed hypnotherapy.

In conclusion, this study confirms previous findings on the long‐term efficacy of gut‐directed hypnotherapy [13, 15, 17, 25]. Even though 40 years have passed since the first report on the efficacy of gut‐directed hypnotherapy for IBS was published, access to treatment is still problematic. Evaluating the long‐term effects of the treatment administered in formats that would support wider availability and greater cost‐effectiveness, such as group treatment and hypnotherapy administered by a nurse, is therefore of great importance. The tendency for a better effect in younger patients implies that gut‐directed hypnotherapy may have even better efficacy when used at an earlier stage in the course of the disorder and should not only be used as a last resort treatment when everything else has failed.

Author Contributions

Jenny Lövdahl: study concept and design, administration of the hypnotherapy treatment, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtained funding. Michaela Blomqvist‐Storm: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript. Olafur S. Palsson: author of the hypnotherapy protocol, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Gisela Ringström: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Hans Törnblom: study concept and design, referred patients to the study, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Magnus Simrén: study concept and design, referred patients to the study, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision, obtained funding. Inês A. Trindade: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. All authors have approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (diary numbers 686‐11 and 636‐12).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

Supporting Information S2

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pia Agerforz, a registered nurse who worked at the gastrointestinal outpatient clinic where the hypnotherapy treatment and research were performed. By initiating the hypnotherapy treatment at the unit, translating the gut‐directed hypnotherapy script to Swedish, and administering hypnotherapy to the first 63 patients, she has contributed substantially to the work included in this paper.

Funding: This study was funded by the Healthcare Committee, Region Västra Götaland (Grants VGFOUREG 855971 and VGFOUREG 930214), the Swedish Research Council (Grants 2018‐02566 and 2021‐00947), the ALF‐ agreement (Grants ALFGBG‐726561, ALFGBG‐965173, ALFGBG‐722331 and ALFGBG‐983998) and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Gothenburg.

Jenny Lövdahl and Michaela Blomqvist‐Storm shared first authorship.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Sperber A. D., Bangdiwala S. I., Drossman D. A., et al., “Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study,” Gastroenterology 160, no. 1 (2021): 99–114.e113, 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mearin F., Lacy B. E., Chang L., et al., “Bowel Disorders,” Gastroenterology 150, no. 6 (2016): 1393–1407.e5, 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drossman D. A. and Hasler W. L., “Rome IV‐Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut‐Brain Interaction,” Gastroenterology 150, no. 6 (2016): 1257–1261, 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ford A. C., Sperber A. D., Corsetti M., and Camilleri M., “Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Lancet. 396, no. 10263 (2020): 1675–1688, 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zamani M., Alizadeh‐Tabari S., and Zamani V., “Systematic Review With Meta‐Analysis: The Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 50, no. 2 (2019): 132–143, 10.1111/apt.15325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee C., Doo E., Choi J. M., et al., “The Increased Level of Depression and Anxiety in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 23, no. 3 (2017): 349–362, 10.5056/jnm16220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fond G., Loundou A., Hamdani N., et al., “Anxiety and Depression Comorbidities in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 264, no. 8 (2014): 651–660, 10.1007/s00406-014-0502-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ringstrom G., Abrahamsson H., Strid H., and Simren M., “Why Do Subjects With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Seek Health Care for Their Symptoms?,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 42, no. 10 (2007): 1194–1203, 10.1080/00365520701320455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frank L., Kleinman L., Rentz A., Ciesla G., Kim J. J., and Zacker C., “Health‐Related Quality of Life Associated With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Comparison With Other Chronic Diseases,” Clinical Therapeutics 24, no. 4 (2002): 675–689 Discussion 674, 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lacy B. E., Pimentel M., Brenner D. M., et al., “ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 116, no. 1 (2021): 17–44, 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simren M., Tornblom H., Palsson O. S., and Whitehead W. E., “Management of the Multiple Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2, no. 2 (2017): 112–122, 10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whorwell P. J., Prior A., and Faragher E. B., “Controlled Trial of Hypnotherapy in the Treatment of Severe Refractory Irritable‐Bowel Syndrome,” Lancet. 2, no. 8414 (1984): 1232–1234, 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gonsalkorale W. M., Miller V., Afzal A., and Whorwell P. J., “Long Term Benefits of Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Gut 52, no. 11 (2003): 1623–1629, 10.1136/gut.52.11.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindfors P., Unge P., Arvidsson P., et al., “Effects of Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy on IBS in Different Clinical Settings‐Results From Two Randomized, Controlled Trials,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 107, no. 2 (2012): 276–285, 10.1038/ajg.2011.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindfors P., Unge P., Nyhlin H., et al., “Long‐Term Effects of Hypnotherapy in Patients With Refractory Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 47, no. 4 (2012): 414–420, 10.3109/00365521.2012.658858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller V., Carruthers H. R., Morris J., Hasan S. S., Archbold S., and Whorwell P. J., “Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Audit of One Thousand Adult Patients,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 41, no. 9 (2015): 844–855, 10.1111/apt.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moser G., Tragner S., Gajowniczek E. E., et al., “Long‐Term Success of GUT‐Directed Group Hypnosis for Patients With Refractory Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 108, no. 4 (2013): 602–609, 10.1038/ajg.2013.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schaefert R., Klose P., Moser G., and Hauser W., “Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Hypnosis in Adult Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Psychosomatic Medicine 76, no. 5 (2014): 389–398, 10.1097/psy.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Palsson O. S., “Standardized Hypnosis Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The North Carolina Protocol,” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 54, no. 1 (2006): 51–64, 10.1080/00207140500322933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bremner H., “Nurse‐Led Hypnotherapy: An Innovative Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 19, no. 3 (2013): 147–152, 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lovdahl J., Ringstrom G., Agerforz P., Tornblom H., and Simren M., “Nurse‐Administered, Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy in IBS: Efficacy and Factors Predicting a Positive Response,” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 58, no. 1 (2015): 100–114, 10.1080/00029157.2015.1030492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith G. D., “Effect of Nurse‐Led Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy Upon Health‐Related Quality of Life in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 15, no. 6 (2006): 678–684, 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flik C. E., Laan W., Zuithoff N. P. A., et al., “Efficacy of Individual and Group Hypnotherapy in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IMAGINE): A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial,” Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 4, no. 1 (2019): 20–31, 10.1016/s2468-1253(18)30310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lovdahl J., Tornblom H., Ringstrom G., Palsson O. S., and Simren M., “Randomised Clinical Trial: Individual Versus Group Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 55, no. 12 (2022): 1501–1511, 10.1111/apt.16934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerson C. D., Gerson J., and Gerson M. J., “Group Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Long‐Term Follow‐Up,” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 61, no. 1 (2013): 38–54, 10.1080/00207144.2012.700620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Francis C. Y., Morris J., and Whorwell P. J., “The Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System: A Simple Method of Monitoring Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Its Progress,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 11, no. 2 (1997): 395–402, 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonsalkorale W. M., Houghton L. A., and Whorwell P. J., “Hypnotherapy in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Large‐Scale Audit of a Clinical Service With Examination of Factors Influencing Responsiveness,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 97, no. 4 (2002): 954–961, 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Labus J. S., Bolus R., Chang L., et al., “The Visceral Sensitivity Index: Development and Validation of a Gastrointestinal Symptom‐Specific Anxiety Scale,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 20, no. 1 (2004): 89–97, 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Labus J. S., Mayer E. A., Chang L., Bolus R., and Naliboff B. D., “The Central Role of Gastrointestinal‐Specific Anxiety in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Further Validation of the Visceral Sensitivity Index,” Psychosomatic Medicine 69, no. 1 (2007): 89–98, 10.1097/psy.0b013e31802e2f24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zigmond A. S. and Snaith R. P., “The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 67, no. 6 (1983): 361–370, 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohen J. and ProQuest , Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. (L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clevers E., Tack J., Tornblom H., et al., “Development of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Features Over a 5‐Year Period,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16, no. 8 (2018): 1244–1251.e1241, 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hasan S. S., Whorwell P. J., Miller V., Morris J., and Vasant D. H., “Six vs 12 Sessions of Gut‐Focused Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Trial,” Gastroenterology 160, no. 7 (2021): 2605–2607.e2603, 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Devenney J., Hasan S. S., Morris J., Whorwell P. J., and Vasant D. H., “Clinical Trial: Predictive Factors for Response to Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy for Refractory Irritable Bowel Syndrome, a Post Hoc Analysis,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 59, no. 2 (2023): 269–277, 10.1111/apt.17790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vasant D. H., Hasan S. S., Cruickshanks P., and Whorwell P. J., “Gut‐Focused Hypnotherapy for Children and Adolescents With Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Frontline Gastroenterology 12, no. 7 (2021): 570–577, 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vlieger A. M., Rutten J. M., Govers A. M., Frankenhuis C., and Benninga M. A., “Long‐Term Follow‐Up of Gut‐Directed Hypnotherapy vs. Standard Care in Children With Functional Abdominal Pain or Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 107, no. 4 (2012): 627–631, 10.1038/ajg.2011.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Page R. A. and Green J. P., “An Update on Age, Hypnotic Suggestibility, and Gender: A Brief Report,” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 49, no. 4 (2007): 283–287, 10.1080/00029157.2007.10524505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1

Supporting Information S2

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.