Abstract

Introduction

Splenic artery embolisation (SAE) is a well-established treatment for high-grade splenic laceration due to blunt trauma in haemodynamically stable patients supported by major societal guidelines. However, guidelines support splenectomy in unstable patients, and there are limited data assessing the efficacy and role of SAE in this cohort. This study aimed to analyse the efficacy of splenic artery embolisation for unstable trauma patients in preventing mortality.

Methods

A single-centre retrospective case–control study was performed covering a 13.5-year period. Patients with splenic laceration due to blunt trauma who underwent splenic artery embolisation or splenectomy were identified and analysed. Haemodynamically unstable patients, as defined by a shock index of ≥ 1.0 or systolic blood pressure of < 90 mmHg, who underwent SAE versus upfront splenectomy were compared as specific cohorts. The primary outcomes were all-cause 30-day mortality and splenic salvage rates.

Results

A total of 126 haemodynamically unstable patients underwent SAE for blunt trauma, and eight haemodynamically unstable patients underwent upfront splenectomy. Among unstable patients who underwent SAE, splenic salvage was achieved in 98%, with 4% mortality at 30 days. Comparing unstable patients who underwent SAE versus upfront splenectomy, there was no significant difference in mortality at 30 days (p = 0.34).

Conclusion

Splenic artery embolisation is a safe and efficacious treatment in unstable patients with splenic laceration due to blunt trauma, with no significant difference in mortality compared to upfront splenectomy, supporting SAE as a primary treatment standard in this patient cohort.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Splenic artery embolisation, Trauma, Splenic laceration, Interventional radiology

Introduction

Splenic artery embolisation (SAE) is an established evidence-based treatment in the management of haemodynamically stable patients with acute splenic injury following blunt trauma [1–3]. By preserving the spleen, SAE mitigates the risks associated with splenectomy [4, 5]. Splenic artery embolisation has also been shown to reduce the total length of stay and associated hospital costs, when compared to surgical intervention [6–9]. The spleen plays an important role in blood cell turnover and immune function, and splenectomy is known to increase susceptibility to infections with encapsulated bacteria [10–13]. Multiple studies have investigated splenic function following SAE, with the majority confirming that the long-term immune function of the spleen is preserved [19–23].

Current guidelines recommend non-operative management in haemodynamically stable patients [4, 16, 27]. However, the application of SAE in haemodynamically unstable patients is less-studied and guidelines advocate for splenectomy, based mostly on consensus opinion [28]. Data on outcomes of SAE in unstable patients are scarce, with few studies published to date [14, 15, 27, 29].

This study aimed to analyse the outcomes of SAE in haemodynamically unstable patients following traumatic splenic injury, including all-cause 30-day mortality, splenic salvage and complications. We hypothesised that SAE is an effective treatment strategy and has a similar mortality compared with upfront splenectomy.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

Local ethical approval was granted (576/23), and this study is reported according to the STROBE checklist.

Data Identification and Collection

Patients aged 16 years and over between 15 March 2010 and 6 October 2023 who underwent SAE and/or splenectomy were identified using procedure codes in the Radiology Information System (RIS) and electronic medical record (EMR). Demographics, mechanism of injury, splenic injury grade, as defined by the American Associated of Surgery of Trauma (AAST), blood transfusion volumes and injury severity scores (ISS) were collected from the EMR [30]. Procedural details, including embolic material, location of embolisation and technical success, were recorded.

Definitions

Paired heart rate and blood pressure readings were used to calculate the highest shock index (SI) prior to intervention. Patients with an SI ≥ 1.0 or systolic blood pressure of < 90 mmHg were classified as haemodynamically unstable, which is similar to the previous studies of unstable trauma cohorts [14]. Local institutional practice is for the majority of stable or unstable patients with high grade (AAST grade 3, 4 or 5) to undergo SAE or splenectomy.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The total pool of SAE patients (n = 341) overlaps with a previous publication (n = 232), which did not differentiate between haemodynamically stable and unstable patients [31]. Patients were excluded if they received SAE or splenectomy for a non-traumatic indication or if there were missing data about haemodynamic status, procedural success or mortality. Patients were only included in the final cohorts if haemodynamically unstable prior to intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the all-cause 30-day mortality while secondary outcome was the rate of splenic salvage following SAE. Complications were defined according to the CIRSE classification system [32].

Statistics

Median values were calculated for non-parametric data including time to embolisation, length of procedure and length of stay, and were compared using the rank-sum test. A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

SAE Cohort

A total of 412 patients who underwent splenic artery embolisation (SAE) were identified. After applying exclusion criteria, the final cohort was 126 haemodynamically unstable patients who underwent SAE as primary management of traumatic splenic laceration. The mean age was 42 years with a male predominance (70%) (Table 1). There was one case of penetrating trauma, with all other cases due to blunt trauma.

Table 1.

Splenic Artery Embolisation (SAE) and Upfront Splenectomy Demographics and Outcomes

| Patient characteristics | SAE (n = 126) | Upfront Splenectomy (n = 8) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 42 (18) | 44 (20) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 89 (70) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Female | 37 (30) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | |||

| MVA | 69 (55) | 4 (50) | |

| Fall | 31 (25) | 2 (25) | |

| Other blunt trauma | 25 (20) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Penetrating injury | 1 (0.8) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Injury Severity Score (ISS, median) | 28 | 24 | |

| Blood Products | |||

| Packed Red Blood Cells (median units) | 4 | 4 | |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma (median units) | 3 | 2 | |

| Pooled Platelets (median units) | 1 | 1 | |

| AAST splenic injury grade, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 3 (2.4) | 0 | |

| 3 | 29 (23) | 0 | |

| 4 | 74 (59) | 2 (25) | |

| 5 | 20 (16) | 6 (75) | |

| Time to operation (median, minutes) | 219 | 132 | 0.09 |

| Length of operation (median, minutes) | 60 | 142 | 0.01 |

| Technical success (n, %) | 122 (97) | 8 (100) | 0.41 |

| Patient outcome | |||

| Splenectomy (n, %) | 4 (2) | N/A | N/A |

| Alive at 30 days (n, %) | 121 (96) | 8 (100) | 0.34 |

| Length of stay (median days, IQR) | 11 (5–19) | 8 (7–9) | 0.37 |

Upfront Splenectomy Cohort

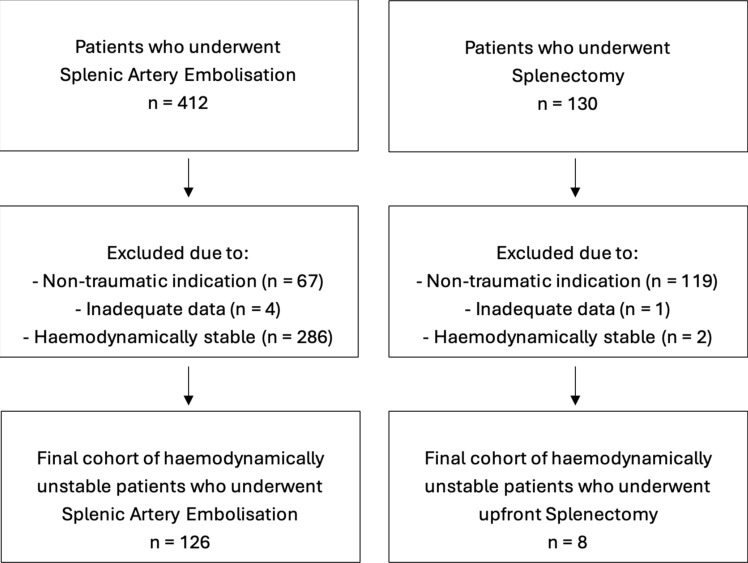

A total of 130 patients who underwent splenectomy were identified (Fig. 1). After applying exclusion criteria, the final cohort was eight haemodynamically unstable patients who underwent upfront splenectomy as primary management of traumatic splenic laceration. The mean age was 44 years, and all had high-grade splenic injuries of AAST grade 4–5 (Table 1). There was one case of penetrating trauma, with all other cases due to blunt trauma (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design flowchart

Procedural Details

The median time to intervention in the unstable SAE group was 219 min, longer than that in upfront splenectomy group (132 min) (p = 0.08) (Table 2), but largely offset by the significantly shorter procedure time for SAE (60 min) compared to splenectomy (142 min) (p = 0.01). In unstable patients who underwent SAE, contrast extravasation was seen in 58% (73/126), and petechial haemorrhage or pseudoaneurysm was seen in 80% (101/127) at the time of angiography. Most SAE procedures were performed with coils deployed proximal to the splenic hilum, with technical success achieved in 97%, defined as stasis or near-stasis of flow in the embolised splenic artery. There were no significant procedural complications with SAE, noting that the appearance of infarct on CT alone was not considered a true complication (Table 3).

Table 2.

SAE procedure details (n = 126)

| Procedure characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Time to embolisation (median, minutes) | 218 |

| Length of procedure (median, minutes) | 60 |

| Type of embolisation, n (%) | |

| Proximal | 91 (72) |

| Distal | 18 (14) |

| Proximal and distal | 17 (13) |

| Embolic agent, n (%) | |

| Coils (only) | 110 (87) |

| Coils + gelatin sponge | 8 (6.3) |

| Vascular plug (only) | 6 (4.7) |

| Gelatin sponge (only) | 2 (1.6) |

Table 3.

Splenectomy post-SAE (n = 4)

| Patient number | Age | Gender | AAST injury grade | Location of embolisation | Type of embolic used | Reason for splenectomy | Days to splenectomy | Mortality at 30 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | F | 4 | Distal | Coils | Increasing abdominal pain | 1 | Yes |

| 2 | 48 | F | 5 | Proximal | Coils | Re-bleed | 4 | No |

| 3 | 32 | M | 5 | Proximal | Coils | Re-bleed | 4 | No |

| 4 | 37 | F | 4 | Proximal | Plug | Persistent pseudoaneurysm | 10 | No |

Clinical Outcomes

The overall splenic salvage rate was 98%, and 30-day mortality was 4% (Tables 1 and 4). Four patients (2%) underwent splenectomy after SAE. Causes of mortality included severe traumatic brain injury, sepsis secondary to hospital-acquired pneumonia and ischaemic bowel unrelated to SAE. Comparing the unstable patients who underwent SAE versus upfront splenectomy, there was no significant difference in the all-cause 30-day survival rate (96 versus 100%; p = 0.34) (Table 1). Overall length of hospital stay was slightly longer for SAE than splenectomy (median of 11 versus 8 days), which may reflect the higher median ISS score in the SAE cohort (28 versus 24).

Discussion

Despite its established role in stable patients, the application of SAE in haemodynamically unstable patients remains less studied and consensus-based guidelines advocate for splenectomy [28]. Our study demonstrated high rates of technical success and splenic salvage, with comparable 30-day survival to upfront splenectomy. The splenectomy rate of 2% in our study was lower than 29% of Guinto et al. and 12% of Zoppo et al. in unstable cohorts [14, 15]. These differences may be due to factors including smaller sample sizes and differences in resuscitation and IR practices within the multidisciplinary trauma team. The mortality rate in our unstable SAE cohort was low (2%) and consistent with Zoppo et al. [14], who demonstrated no significant difference in 30-day survival rates comparing stable and unstable cohorts. The study by Zoppo et al. did not, however, have a comparison with upfront splenectomy.

Our local institution primarily utilises embolisation as the first-line treatment for AAST grade 3–5 splenic injuries on CT, regardless of angiographic findings at time of DSA, with upfront splenectomy typically reserved for those patients who are already planned for laparotomy for other indications. Embolisation is typically performed by deploying coils proximal to the splenic hilum. Patients are monitored after SAE clinically, then discharged and followed up in the IR outpatient clinic after at least 6 weeks with testing of Howell–Jolly bodies. The IR unit is staffed by seven specialists (5.5 effective full-time) who provide 24 h on-call services.

Our study has limitations to acknowledge, including the single-centre retrospective design that may lack some items of clinical data and have limited broad applicability between centres. The measurements used to indicate haemodynamic instability, namely systolic blood pressure and shock index, are imperfect and may not account for transient responders or permissive hypotension. There was also variation in procedure technique, including embolisation agents and location.

Conclusion

This study showed that SAE in haemodynamically unstable patients resulted in a high rate of splenic salvage and low mortality, with no significant difference in mortality compared to a small cohort of unstable patients who underwent upfront splenectomy, supporting SAE as a primary treatment standard in this patient cohort.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alfred Health, Victorian Health Libraries Consortium (VHLC). This research was not supported by any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clements W, Moriarty HK, Koukounaras J. Splenic artery embolisation in trauma: it is time to stand alone as its own treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:1720–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements W, Fitzgerald M, Chennapragada SM, Mathew J, Groombridge C, Ban EJ, et al. A systematic review assessing incorporation of prophylactic splenic artery embolisation (pSAE) into trauma guidelines for the management of high-grade splenic injury. CVIR Endovasc. 2023;6:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, Duane TM, Wilson SP, Haney S, O’Neill PJ, Evans HL, et al. Trauma center variation in splenic artery embolization and spleen salvage: a multicenter analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habash M, Ceballos D, Gunn AJ. Splenic artery embolization for patients with high-grade splenic trauma: indications, techniques, and clinical outcomes. Semin Interv Radiol. 2021;38:105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong Y-C, Wu C-H, Wang L-J, Chen H-W, Lin B-C, Hsu Y-P, et al. Distal embolization versus combined embolization techniques for blunt splenic injuries: comparison of the efficacy and complications. Nat Lib Med. 2017;8(56):95596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yip H, Skelley A, Morphett L, Mathew J, Clements W. The cost to perform splenic artery embolisation following blunt trauma: analysis from a level 1 Australian trauma centre. Injury. 2021;52:243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiolfi A, Inaba K, Strumwasser A, Matsushima K, Grabo D, Benjamin E, et al. Splenic artery embolization versus splenectomy: Analysis for early in-hospital infectious complications and outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarborough JE, Ingraham AM, Liepert AE, Jung HS, O’Rourke AP, Agarwal SK. Nonoperative management is as effective as immediate splenectomy for adult patients with high-grade blunt splenic injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl WL, Ahrns KS, Chen S, Hemmila MR, Rowe SA, Arbabi S. Blunt splenic injury: operation versus angiographic embolization. Surgery. 2004;136:891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones B, Elbakri A, Murrills C, Patil P, Scollay J. Splenic artery embolisation for blunt splenic trauma: 10 years of practice at a trauma centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2024;106:283–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slater SJ, Lukies M, Kavnoudias H, Zia A, Lee R, Bosco JJ, et al. Immune function and the role of vaccination after splenic artery embolization for blunt splenic injury. Injury. 2022;53:112–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruhnke H, Jehs B, Schwarz F, Haerting M, Rippel K, Wudy R, et al. Non-operative management of blunt splenic trauma: the role of splenic artery embolization depending on the severity of parenchymal injury. Eur J Radiol. 2021;137: 109578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinwar PD. Overwhelming post splenectomy infection syndrome—review study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1314–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoppo C, Valero DA, Murugan VA, Pavidapha A, Flahive J, Newbury A, et al. Splenic artery embolization for unstable patients with splenic injury: a retrospective cohort study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guinto R, Greenberg P, Ahmed N. Emergency management of blunt splenic injury in hypotensive patients: total splenectomy versus splenic angioembolization. Am Surg. 2020;86(6):690–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu PP, Lee WC, Cheng YF, Hsieh PM, Hsieh YM, Tan BL, et al. Use of splenic artery embolization as an adjunct to nonsurgical management of blunt splenic injury. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2004;56:768–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil MS, Goodin SZ, Findeiss LK. Update: splenic artery embolization in blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Interv Radiol. 2020;37:097–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olthof DC, Van Der Vlies CH, Goslings JC. Evidence-based management and controversies in blunt splenic trauma. Curr Trauma Rep. 2017;3:32–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skattum J, Titze TL, Dormagen JB, Aaberge IS, Bechensteen AG, Gaarder PI, et al. Preserved splenic function after angioembolisation of high grade injury. Injury. 2012;43:62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakae H, Shimazu T, Miyauchi H, Morozumi J, Ohta S, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Does splenic preservation treatment (embolization, splenorrhaphy, and partial splenectomy) improve immunologic function and long-term prognosis after splenic injury? J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2009;67:557–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bessoud B, Duchosal MA, Siegrist C-A, Schlegel S, Doenz F, Calmes J-M, et al. Proximal splenic artery embolization for blunt splenic injury: clinical, immunologic, and ultrasound-doppler follow-up. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2007;62:1481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra AK, Carter RF, Lebman DA, Carter DS, Riaz OJ, Aboutanos MB, et al. Preservation of splenic immunocompetence after splenic artery angioembolization for blunt splenic injury. J Trauma Injury, Infect Crit Care. 2010;69:1126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukies M, Zia A, Kavnoudias H, Bosco JJ, Narita C, Lee R, et al. Immune function after splenic artery embolization for blunt trauma: long-term assessment of CD27+ IgM B-cell levels. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2022;33:505–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clements W, Koukounaras J, Joseph T. Reply to “damage control interventional radiology (dcir): evolving value of interventional radiology in trauma.” Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:1759–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clements W, Bolger M, Varma DK. Immediate angiography after major trauma: establishing feasibility through systems, governance, and infrastructure. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2024;47:481–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clements W, Dunne T, Clare S, Lukies M, Fitzgerald M, Mathew J, et al. A retrospective observational study assessing mortality after pelvic trauma embolisation. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2024;68:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong RA, Macallister A, Walton B, Thompson J. Successful non-operative management of haemodynamically unstable traumatic splenic injuries: 4-year case series in a UK major trauma centre. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45:933–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, et al. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao C, Kuo L, Wu Y, Liao C, Cheng C, Wang S, et al. Unstable hemodynamics is not always predictive of failed nonoperative management in blunt splenic injury. World J Surg. 2020;44:2985–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozar RA, Crandall M, Shanmuganathan K, Zarzaur BL, Coburn M, Cribari C, et al. Organ injury scaling 2018 update: spleen, liver, and kidney. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85:1119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clements W, Joseph T, Koukounaras J, et al. SPLEnic salvage and complications after splenic artery EmbolizatioN for blunt abdomINal trauma: the SPLEEN-IN study. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:92. 10.1186/s42155-020-00185-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filippiadis DK, Binkert C, Pellerin O, Hoffmann RT, Krajina A, Pereira PL. Cirse quality assurance document and standards for classification of complications: the Cirse classification system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cinquantini F, Simonini E, Di Saverio S, Cecchelli C, Kwan SH, Ponti F, et al. Non-surgical management of blunt splenic trauma: a comparative analysis of non-operative management and splenic artery embolization—experience from a European trauma center. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:1324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]