Abstract

Control of the intervals between proliferation and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells is coordinated by developmental regulators, comprised of both microRNAs (miRNAs) and proteins, termed heterochronic genes. The heterochronic factors, Lin28-RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and the miRNAs–Let-7, comprise a unique subset of evolutionarily conserved genes that regulate the developmental timing of metazoans, from worms to mammals. While there has been much investigation into the reciprocal negative feedback loop between LIN-28 and Let-7 during fetal development and cancer. Few have investigated how positive regulatory loops between the mammalian Lin28-RBPs, and mRNAs order spatiotemporal transitions of progenitors from specification to organogenesis. Screening for factors that activated luciferase reporters of the human LIN28A and LIN28B promoters, in combination with genetic mouse models, we demonstrate positive feedforward loops between key developmental transcription factors such as B-Catenin, Sox2, Sox9, and Lin28-RBPs. Furthermore, we demonstrate heterochronic regulation of morphogenesis is not only genetically modulated but also molecularly fine-tuned via position-dependent sequences in the 5′ and/or 3’ untranslated regions.

Highlights

-

•

LIN28A and LIN28B promoters are differentially regulated.

-

•

5′UTR regions of mRNAs have LIN28 consensus binding sites that are guanine rich compared to 3′UTR.

-

•

Lin28a and Lin28b are differentially regulated in the lung by Sox2, Sox9 and β-Catenin.

1. Introduction

Genetic changes that modulate the developmental timing of an organism–1) in relation to other organisms in the same genus, and/or −2) with regards to the cell fate of one tissue relative to other tissues in the same organism are classified as heterochrony [1,2]. The rate and timing of development is regulated by a subset of factors identified as heterochronic genes [1]. Originally discovered in C. elegans as one of the key axes that orchestrates the intervals of proliferation and the transition to differentiation [3], these gene regulatory networks consisted of the first miRNAs discovered – lin-4 followed by let-7; and DNA/RNA-binding proteins – hbl-1, lin-14 and lin-28 [1,4]. The temporally regulated feedback loop between the RNA-binding proteins (RBP) Lin28 and the miRNA let-7 is evolutionarily conserved in all metazoans. Loss of both Lin28 paralogs leads to early embryonic lethality in mice [5], and human GWAS studies associate SNP variations of LIN28 with the improper timing of puberty. During early to mid-gestation, Lin28 binds to the stem-loop of the let-7's, obstructing their processing and subsequent expression. At later stages of development, once expressed, let-7 binds the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the Lin28 mRNAs to suppress their translation [[6], [7], [8]]. Studies in worms showed that Lin-28 functions via two genetically distinct mechanisms. The first mechanism, via Lin-28 binding to the 3′UTR of hbl mRNA, leading to its enhanced translation at the L1-L2 transition, with the second mechanism occurring at the L2-L3 transition via suppression of the Let-7 miRNAs [9].

The Lin28 paralogs (Lin28A and Lin28B) were previously shown to be strict onco-fetal proteins whose expression, via a reciprocal regulatory relationship with the family of Let-7 miRNAs, are high throughout early development, off in adult tissues, and re-expressed in various tumors. Unlike many oncogenes, the amplification and mutation rates of LIN28 A/B are extremely low, which is suggestive of a transcriptional re-activation [10]. We and others have previously demonstrated expression of Lin28a and Lin28b throughout the whole murine embryo that persists in the cell lineages of all three germ layers until about E9.5, after which is restricted to certain tissues, such as the lung [11,12]. We have recently demonstrated that these mammalian paralogs are also heterochronic regulators of branching morphogenesis in the lung, kidney, and mammary glands, such that when they are knocked out in the lung epithelium, leads to perinatal lethality [11,13]. Similar to the two distinct RNA regulatory mechanisms found in worms, we observed the actions of Lin28a and Lin28b in the early embryonic lung were Let-7-independent, regulating the mRNA targets Etv5, Sox2, and importantly Sox9 [11]. Interestingly, transcriptional regulation of LIN28 has been investigated during induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming by the Yamanaka factors comprised of OCT4, KLF4, SOX2 and c-MYC (OSKM) [14,15], neurogenesis via SOX2 [16], and breast cancer stem cell maintenance by B-CATENIN [17]. However, these previous studies have all suggested increased expression of LIN28 is mainly to reduce the pro-differentiation effects of Let-7 [14,[16], [17], [18]].

Lung development begins with the patterning and differentiation of the definitive endoderm into the anterior foregut and posterior midgut organ domains [19]. The forkhead transcription factors, specifically Foxa2 and Foxa3, regulate the induction of foregut and midgut endodermal patterning [[20], [21], [22]]. Once the lung is specified, the first transcription factor that is expressed and regulates proper lung development is Nkx2-1 [23,24]. The developed lung epithelium becomes functionally divided into two divergent compartments: the bronchiolar conducting airways of the proximal lung and the alveolar gas exchange region of the distal lung. Sox2 and Sox9 have been shown to mark and control the two developmental waves of lung branching morphogenesis [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. Correct lung formation is contingent upon reciprocating paracrine and autocrine signaling of the endodermal-derived epithelium and the mesodermal-derived mesenchyme [29]. Several key signaling pathways together with multiple downstream transcriptional effectors, such as Wnt/B-Catenin and Fgf10/Etv5, Etv4, and Sox9, were found to cooperate in feedback and feedforward regulation, one example being B-Catenin upregulation of Sox9 expression during lung specification [30].

In our present study, we conducted a luciferase reporter screen for transcription factors that were able to transactivate the human LIN28A/LIN28B cis-regulatory elements. We found the pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, NANOG, MYC, along with factors that control multipotent progenitors (such as MYCN and B-CATENIN), hematopoiesis (such as MYB), endoderm differentiation (regulated by FOXA2 and FOXA3), mesoderm/neuromesodermal differentiation (via NOTCH and HOXB4), and epithelial lung development (via NKX2-1 and SOX9) were all able to differentially increase the expression and the luciferase activity of LIN28A and LIN28B. Previously, we demonstrated the ability of LIN28A protein to bind and regulate the stability and translation of Sox9, Etv5, and to a lesser extent Sox2 mRNAs [11]. In our current study, we found that several transcription factors able to regulate the human LIN28A/LIN28B enhancer/promoter elements in our reporter screen were also present in the polyribosome fractionation of brain-specific double knockout (dKO) and differentially expressed in lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b. Interestingly, we observed lung epithelial-specific knockout of B-Catenin, Sox2, and Sox9 at the onset of branching morphogenesis led to a significant decrease of Lin28a, and Lin28b.

2. Results

2.1. -2kb from the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the Lin28A and Lin28B genomic regulatory sequences more active than other putative sequences

Phylogenetic analysis suggests a gene duplication event in the ancestral invertebrate heterochronic gene, lin-28 (originally found in C. elegans), led to the appearance of the vertebrate paralogs, Lin28a and Lin28b [31,32]. Previous protein sequence alignments of Drosophila, Xenopus, Zebrafish, and mammals confirmed the presence of two unique RNA-binding domains: a cold shock domain (CSD), and two CCHC zinc-finger motifs not usually found together in animals however, found in the plant Lin28 homologue, PpCSP1 [[32], [33], [34]]. Vertebrate Lin28A proteins clustered together with strong bootstrap support, while Lin28B formed a separate clade that is slightly more divergent (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, early branching vertebrates – such as lamprey– appear to still have a single Lin28 that did not cluster with Lin28A nor was completely Lin28B-like. While protein sequences imply one level of conservation, the genomic regulatory sequences suggest another. Lin28A/B expression is important for the maternal oocyte-zygote transitions [[35], [36], [37]], germ layer specification/early embryonic development [5,17,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]], neuroectoderm differentiation, and more recently, kidney and lung branching morphogenesis [5,17,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]].

Fig. 1.

Comparison of protein and genomic regulatory sequences. A) Phylogenic analysis of Lin28A and Lin28B protein sequences using the bioinformatics tool https://www.genome.jp/en/gn_tools.html >Tree > phylogeny. B) Visualization of conserved genomic regulatory sequences for human LIN28A and LIN28B, in Chimp, Mouse, Xenopus, Zebrafish and Lamprey using UCSC genome browser (Perez et al., 2024). Assembly used was hg38 for LIN28A (chr1:26,406,455–26,417,607) RefSeq NM_024674.6 and LIN28B (chr6:104,950,183–104,964,925) RefSeq NM_001004317.4. Promoter denoted red; Proximal (Prox) enhancer sequences denoted orange; Distal (Dist) enhancer sequences denoted yellow. C) Schematic of genomic regulatory sequences identified from B). Fragments were cloned into the promoter-less Renilla luciferase construct – pGL4.79. The CMV- luciferase construct pGL4.50 was used to normalize. Constructs tested in human ovarian teratocarcinoma cell line PA-1, data representative three independent experiments.

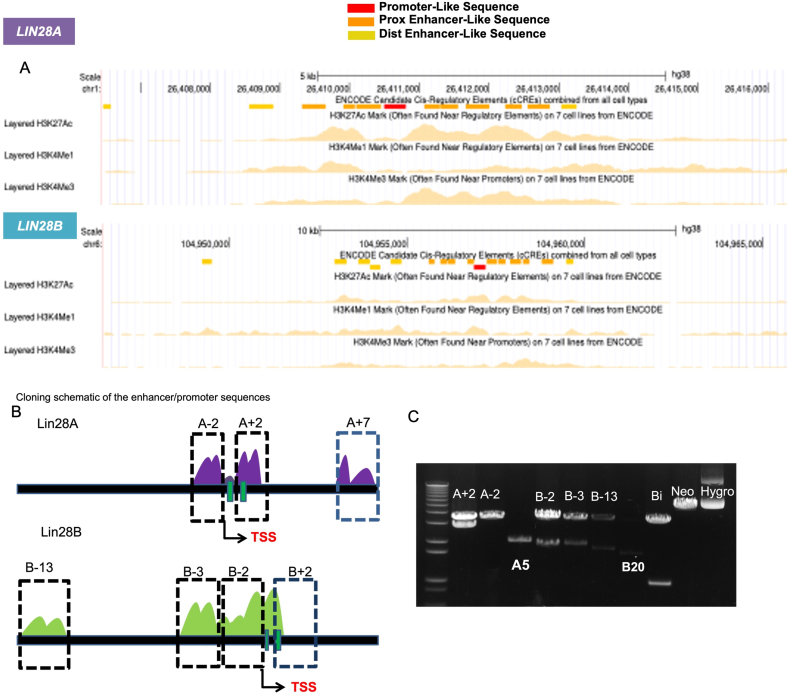

Given the multifaceted spatiotemporal expression and function of LIN28A and LIN28B, we sought to investigate the differential transcriptional regulation during key transition points throughout mammalian development. Publicly available chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) of the active histone marks in H1 human embryonic stem cells (hESC) [42] (Fig.S1A), armed us with the putative regulatory regions of LIN28A and LIN28B. We found several conserved genomic regulatory sequences for promoter regions (red), proximal (orange), and distal (yellow) enhancers of LIN28B maintained in human, chimp, mouse, frog and zebrafish, while the LIN28A promoter and enhancer regions preserved similarity in human, chimp, mouse and frog, but not zebrafish (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, only a single proximal enhancer region between exon 1 and exon 2 of Lin28A and Lin28B was conserved in lamprey and the other organisms. Next, we cloned these regulatory fragments of roughly 2 kb from H1 hESCs to determine the key regulatory sequences (promoter and enhancer elements) of LIN28A and LIN28B (Fig.S1B-S1C). Regulatory regions for Lin28A at (−2 to +2/2.5 kb), and LIN28B at (−2 to −13kb) were chosen based on previously described regulatory sequences [17,43]. Fragments were then subcloned into luciferase constructs and then tested for activity in the embryonal carcinoma cell line, PA-1 (Fig. 1C). Not surprisingly, the -2kb fragment from the transcription start site, which contained both promoter and proximal enhancer sequences of both LIN28A and LIN28B, was more enzymatically active than the enhancer sequences alone. However, we did observe the +2/2.5 kb fragment of LIN28A, which contained four proximal exonic enhancers, also had high luciferase activity (Fig. 1C).

2.2. Expression of LIN28A and LIN28B are differentially controlled by several master regulators of embryogenesis

Due to their capacity to maintain pluripotency states during early embryogenesis, the Yamanaka factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC (collectively known as OSKM) are necessary and sufficient for iPSC reprogramming [44]. These transcription factors have been shown, together and individually, to regulate expression of LIN28A and LIN28B during stem/pluripotency maintenance and throughout lineage specification and differentiation. Sox2 regulates Lin28a, and to a lesser extent Lin28b, expression during neurogenesis in neural precursors [16], while the oncogene MYC is capable of transcriptionally upregulating LIN28B during cancer initiation, and LIN28A can replace MYC during induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation [45,46].

We investigated whether transcription factors known to control germ layer transitions to organogenesis could regulate the promoter/enhancer regions of human LIN28A and LIN28B (Fig. 2A). We conducted an in vitro high-throughput expression and luciferase reporter screen in HEK293 cells stably expressing the -2kb regulatory fragment driving Renilla luciferase (Fig. S2A-S2B). As positive controls in our initial screen, we found the pluripotency factors OSKM and NANOG (Fig. S2A-S2B), were able to increase both the expression and luciferase activity of LIN28A, and to a somewhat lesser extent LIN28B, possibly due to basal LIN28B expression in HEK293 (Fig. S2A-S2B). We examined B-CATENIN and SOX9, as their pleiotropic role in disease and organogenesis of several organs/tissues are well known [26,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51]]. We additionally investigated FOXA2 and FOXA3 for their regulation of endodermal fates [20,21,52], NOTCH and HOXB4 that function during mesoderm/neuromesoderm differentiation [53], NKX2-1 as the first transcription factor required for lung specification [54], and MYB during hematopoiesis [55] (Fig. S2A-S2B). Like the pluripotent factors, there was an increase of both the expression and luciferase activity of LIN28A, and to a lesser extent LIN28B in the HEK293 cells.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional regulation of LIN28A and LIN28B by developmental transcription factors. A) Schematic of transcription factors that orchestrate germ layer formation and early embryonic lineage specification and differentiation. B) Top: Schematic of morphogen-induced lung/endoderm formation from iPSCs through initiation of lung progenitors in vitro. Bottom: Gene expression analysis of single cell RNA-sequencing of roughly 10,000 cells (close 1200 for each day) throughout morphogen-directed lung endoderm formation from iPSCs. Data from manuscript (Ori et al., 2023). C) Fold change in gene expression of LIN28A and LIN28B upon infection of embryonic lung fibroblast WI-38, with adenoviral constructs: GFP, FOXA2, NKX2-1, SOX2 and SOX9 for 48–72 h before lysing in Trizol. Dots on the graph representative of n = 2 independent experiments in quadruplicate. D) Schematic of development of endoderm differentiation. Transient transfection of txrn factors into HEK293 with construct stably expressing dual luciferase construct; firefly and Renilla luciferase. Validation of a subset of factors that regulated human LIN28A and LIN28B promoter/enhancer sequences during screening experiments in panels B) and C) during E) pluripotency and F) endoderm/lung development. G) progenitor specification. Graphs in E), F) and G) are representative of n = 2 independent validation experiments out of 3. P values for C) were determined using 2-way ANOVA of normal distribution. P values of significance: In the order of left to right for panel C: LIN28A – FOXA2- ∗0.024, NKX2-1- ∗0.035, SOX9- ∗0.021; LIN28B – NKX2-1- ∗0.021, ∗SOX9- 0.021 P values for graphs E), F) and G) were determined using 1-way ANOVA of normal distribution in E) and 1-way ANOVA of lognormal distribution for F) and G). P values of significance: In the order of left to right for each panel: E)∗ 0.0375, ∗∗ 0.0021; ∗ 0.0184, ∗0.0321 F)∗ 0.0434, ∗0.0325; ∗0.0191, ∗0.0477 G)∗∗0.0097,∗ 0.0112; ∗∗0.0021, ∗∗0.0078; ∗∗ 0.0036, ∗∗0.0079; ∗∗0.0072, ∗0.0160. Schematics A), B), D) were made using BioRender.

The promoter sequences of LIN28A and LIN28B, like many developmentally regulated genes, have been shown to display bivalent chromatin states, whereby histone marks of both activation and repression coincide on the same regulatory sequences [14]. During iPSC reprogramming of fibroblasts, protein expression of LIN28A and LIN28B have been described to be temporally separated, where expression of LIN28B is reactivated before LIN28A [14]. However, the fluctuations in LIN28A and LIN28B expression during germ layer formation, specifically the endoderm is currently unknown. Several studies have investigated directed differentiation of iPSC toward lung/endoderm lineages, using developmental biology as a roadmap [25,26,29,30,49,51,[56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63]]. The combined use of morphogens and pioneering transcription factors with the unique ability to remodel heterochromatin is critical for directed and iPSC reprogramming, thus we analyzed recently published data using this approach. We performed gene expression analysis of previously published single-cell RNA-sequencing of data from morphogen-directed lung/endoderm formation from iPSCs [64]. Interestingly, these data revealed that LIN28A expression, while high in the pluripotent stage, is low during the definitive endoderm phase and peaks during the foregut endoderm to lung progenitor transition (Fig. 2B). To examine the sufficiency of transcriptional activation by the developmental pioneer transcription factors FOXA2, NKX2-1, SOX2 and SOX9, we next turned to the primary embryonic lung fibroblast cell line, WI-38, which have no expression of LIN28A or LIN28B. FOXA2, NKX2-1, and SOX9 were found to be sufficient to initiate significant expression of LIN28A, while NKX2-1 and SOX9 were shown to be sufficient to induce significant LIN28B expression in embryonic lung fibroblasts (Fig. 2C). Similar to the expression profiling during morphogen-induced lung/endoderm reprograming in Fig. 2B, the expression of LIN28A peaked at the same time points SOX17 and FOXA2 are purportedly regulating definitive endoderm and B-CATENIN is regulating WNT-driven expansion of lung progenitors (Fig. 2B–D). Interestingly, the expression profile of LIN28B during lung/endoderm reprogramming mirrors the expression profile of SOX2 (Fig. 2B), although during the first three days of directed reprogramming SOX2 did not activate mRNA expression in primary lung fibroblast (Fig. 2C). These data presented thus far suggest that there is not only differential regulation of LIN28A and LIN28B by distinct transcription factors but also their regulation is central during developmental transitions (in the case of LIN28A) and/or for progenitor expansion (in the case of LIN28B).

We further validated our screen using the pluripotent factors and those factors whose role during lung organogenesis were similarly crucial for neuronal differentiation. Targeted luciferase reporter experiments validated previous screening data and confirmed differential activation of the promoter/enhancer regions of human LIN28A and LIN28B by SOX9, NKX2-1, FOXA2, FOXA3, NOTCH (ICD), MYB, MYCN and B-CATENIN (Fig. 2E–G). Congruent with the previously published reprogramming data and our sufficiency data, we found both LIN28A and LIN28B promoters significantly activated luciferase expression when bound to the pluripotent factors NANOG and MYC (Fig. 2E), the definitive endoderm factor FOXA2 (Fig. 2F), and the lung specification/progenitor regulators: NKX2-1, MYCN and B-CATENIN (Fig. 2G). Significant differential control of the LIN28A and LIN28B promoters were observed via MYB regulation of the LIN28A promoter and ICD of NOTCH which are both regulators of mesodermal/hematopoietic fates (Fig. 2G). Taken together, in addition to the known regulation of LIN28A and LIN28B promoter/enhancer activity via OSKM, we uncovered several key developmental transcription factors known for multipotent stem/progenitor cell maintenance into adulthood as well as germ layer formation/developmental transitions during organogenesis.

2.3. Delayed branching phenotypes of dKO Lin28a and Lin28b are not via previously reported master regulators of cell cycle

We recently demonstrated that dKO of Lin28a/b in the lung epithelium have let-7-independent defects during early lung branching due to loss of mRNA-binding to Etv5, Sox2, and more importantly Sox9 [11]. Thus, our next steps were two-fold; first, we sought to determine in vivo, if there was feedback/feedforward regulation between the Lin28 proteins and transcription factors from our initial screen. Our hypothesis: transcription factors upregulate Lin28a/b expression to enhance stabilization and translation of their own mRNAs to complete morphogenetic programs. Previous work from our group suggested Lin28a in the lung epithelium binds to and enhances the stability and translation of Sox9 mRNA. Second, we investigated whether canonical Lin28-RBP motifs overlapped with the conserved 3′UTR let-7-miRNA binding motifs of early developmental transcription factors important for lung/endoderm and neuronal differentiation. Using a Sox2eGFP reporter, we observed loss of Lin28a/b at the early onset of lung branching led to delayed lateral branching, which eventually led to decreased size and complexity of branches during later developmental time points (Fig. 3A–B). We recently reported decreased lung size of 50 % of the epithelium specific dKOs at later time points compared to no difference in size at early developmental times [11], recapitulated here with our Sox2eGFP reporter; dKO lungs, suggesting possible proliferation defects (Fig. 3A–B). Previous studies have implicated LIN28A control of cell cycle progression via both let-7-dependent and independent mechanisms involving the regulation of cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) [65]. Evaluation of cyclin and CDK expression in E12.5 dKO lungs led to the conclusion that mRNA-mediated branching defects were not via these general cell cycle regulators, as previously shown in other systems (Fig.S3A-S3B). However, we observed a significant decrease in mRNA expression of the proliferation marker, KI-67 at E12.5. suggesting proliferation defects could be partly responsible for size differences (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Loss of Lin28a/b in the developing lung leads to decreased mRNA expression of anterior endoderm/lung specification genes. Brightfield and fluorescent images of whole left lungs from wild type (WT) littermate or mutant (NKX2-1creER; Sox2GFP; Lin28a+/−;Lin28b+/− (dHetKO), Lin28a−/−;Lin28b+/− (aKO,bhet), or Lin28a−/−Lin28b−/− (dKO) removed at A) E12.5 and B) E15.5 from dams given tamoxifen at E10.5. Images were representative of three independent experiments. C) Graphs demonstrating Mki-67 and Pcna (regulator of DNA replication) gene expression from RNA-seq of the lung specific dKO of Lin28a/b (n = 3) and WT (n = 2). D) Fold change of mRNAs found during polyribosomal profiling in the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in brain (Herrlinger et al., 2019) compared to expression found in RNA-seq of the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in lung epithelium (Osborne et al., 2021). FKPM of genes involved in E) stem/pluripotency maintenance and F) endodermal differentiation from RNA-seq of the lung-specific Lin28a/b dKO (n = 3) and WT (n = 2). G) Sequence alignment of select mRNAs from E) and F) performed in Clustal Omega. Numbers on the right represent nucleotide positions in the mRNA sequence. Blue boxes highlight similarities in sequences in the N-Terminal and C-Terminal. Red adenines are to aid identification of G-rich sequences. H) QGRS scores (G-Scores) compared to total number of QGRS of previously identified direct targets of Lin28a/b and genes of interest FOXA2 and B-CATENIN. I) Predicted let-7 binding sites of known and putative Lin28-mRNA targets in TargetScan (Agarwal et al., 2015) https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/. Data values are means of±S.D. Scale bars for: A) are 0.5 mm; for B) 50um. Lungs for RNA-sequencing (DKO, n = 3, WT, n = 2) in C), F), and G) were isolated from two independent experiments. P values for all graphs were determined using 2-way ANOVA, P values of significance: In the order of left to right for each panel: C)∗ 0.0175 E)∗∗∗0.0006 F)∗0.0320,∗∗ 0.0090, ∗∗0.0053, ∗∗∗0.0006, ∗0.0283.

2.4. Comparative analysis of brain and lung double knockout of Lin28a and Lin28b

The use and re-use of morphogenetic signaling pathways and their downstream gene regulatory networks coordinate the spatiotemporal development of all complex organs/tissues. The progenitors of each epithelial lung compartment in the mouse are marked by Sox2+ cells in the developing proximal lung and Sox9+ cells at the multipotent distal tips [[25], [26], [27], [28],51,[66], [67], [68]]. Gene Ontology analysis from human embryonic distal (SOX9+/SOX2+) and proximal (SOX2+) lung progenitors interestingly indicate a neuronal signature enriched more in the SOX2+ proximal progenitors than the SOX9+/SOX2+ distal progenitors [50]. Given the known functions of the LIN28 proteins during neural development, neuronal differentiation, and recently during axonal regeneration in the adult mouse [16,[69], [70], [71]], we performed comparative analysis of mRNAs regulated by Lin28a/b in dKO lung and neuronal progenitors using our RNA-sequencing and previously published ribosomal profiling of the developing brain from identical developmental time points [72]. The mRNAs from signaling pathways including Notch, Wnt/B-Catenin, and Shh, together with their downstream transcriptional effectors were being actively translated in polyribosome fractions in the brain and differentially expressed in our lung samples (Fig. 3D). RNA-sequencing of lung-specific dKO revealed expression levels of known Lin28-mRNA targets such as the stem/pluripotent factor OCT4 (gene; Pou5f1) and the cell-cycle regulators Cyclin D2 (Ccnd2) and Cyclin B1 (Ccnb1) did not change as previously shown in other systems (Fig. 3E and S3A and S3B) [65]. Surprisingly, we observed repression of Ctnnb1 (B-Catenin) mRNA in the lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b (Fig. 3E), which was not previously described as a Lin28 or let-7-mRNA target.

Next, we selected transcription factors responsible for lung/endoderm differentiation for which we observed regulation of the LIN28A and LIN28B enhancer/promoter regions. Expression genes critical for anterior foregut endoderm/lung specification such as Foxa1, Foxa2, and Nkx2-1, were significantly decreased upon dKO of Lin28a/b, while genes important for posterior foregut endoderm/hindgut formation such as Foxa3, Pdx1, and Cdx2 were unchanged (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, expression of Gata6, shown to be important for endoderm fate specification of intestine, lung, and pancreatic formation, and Hhex1, important for liver formation were statistically increased [73,74](Fig. 3F). Multiple sequence alignments of known and potentially direct Lin28-mRNA targets revealed a curious observation. Two clusters formed, one at the 5′UTR N-terminus for those with relatively high guanine content and the other at the 3′UTR C-terminus with low to moderate guanine content (Fig. 3G). Intriguingly, the 3′UTR mRNA cluster also grouped with motifs within let-7 miRNA, motifs whose binding by Lin28a/b CSD and the two CCHC zinc-finger domains result in inhibition and ultimate degradation [8].

The ability of guanines to form 3D structures called G-quartets, which are composed of tetrad links stabilized via hydrogen bonds, has been associated with enhanced mRNA – stability, splicing, translation initiation and repression [75]. The bioinformatics tool, Quadruplex G-Rich Sequence (QGRS) mapper, was designed to predict these G-quartets 3D structures within mRNA sequences that are bound by RNA-binding proteins [75]. Utilizing QGRS mapper, we examined the presence of the canonical Lin28a RNA binding motif GGAGAU (conserved in both miRNA and mRNA), as well as G-rich quartet structures with the degenerate sequences AAGNNG, AAGNG(N), and (N)UGUG(N), where “N” could be any nucleotide [76,77]. High QGRS scores are sequences that are more likely to form a high number of stable G-quartets. Comparison of sequences from known LIN28-mRNA and -miRNA bound targets (Mirlet7A1, Pou5f1, and Hmga2) to those in our lung-specific dKO data set revealed moderate to high QGRS scores in Foxa2 and B-Catenin (Fig. 3H). Further analysis supported a differential in cluster formation whereby the 5′UTR/promoter regions of Pou5f1, Foxa2, and Ctnnb1 had higher QGRS scores and were not predicted targets of let-7 miRNA (Fig. 3H and I). However, Ccnd2 and Hmga2, which are known targets of both Lin28 and let-7, had higher QGRS scores in the 3′UTR regions that aligned with the let-7 miRNA motifs bound by Lin28a/b (Fig. 3H and I). Taken together, these data suggest a novel mechanism by which Lin28-RBP may differentiate between RNAs to be transcribed or marked for enhanced stability or degradation in embryonic tissue and developing organs, via binding to 3′UTR, 5′UTR, or both sequences. These data also suggest the positions of post-transcriptional sequences work together with transcriptional mechanisms to fine-tune developmental timing.

2.5. Lin28a/b regulates ex vivo neuronal differentiation

Loss of Lin28 paralogs in neural progenitor cells (NPC) was previously shown to cause significant defects in neurulation, which included reduced rates of proliferation, failure of neural tube closure, microcephaly, and precocious differentiation of glial lineages [5,71,72]. We used the neurosphere assay as our model of differentiation – where neural stem cells isolated from embryonic or adult brains form suspension spheroids, capable of limited self-renewal and multipotent differentiation (Fig. 4A) [78]. We were able to repeat previously described defects of Lin28 loss in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced neuronal differentiation at embryonic time points in vitro [79]. Lin28 dKO in vitro was monitored using adenoviral control and Cre Recombinase tagged with GFP followed by spontaneous differentiation (Fig. 4B). Loss of Lin28a/b post-neurosphere formation did not grossly affect cell number or the ability of neurospheres to differentiate (Fig. 4B and S4A). However, in the presence of BDNF-induced neuronal differentiation we observed decreased complexity measured by axonal projections and extensive branching (Fig. S4A-S4C) and significantly decreased BIII tubulin positivity (Fig. 4B–C and S4D-S4F). Taken together, this data further confirms the role of the Lin28 paralogs in specification and differentiation of neuronal lineages.

Fig. 4.

Loss of Lin28a/b in neural stem cells lead to decreased axonal projections and arborization A) Neurospheres were derived from embryonic cortical neural stem cells of wild type mice. Spheroids were allowed to spontaneously differentiate in differentiation media (without BDNF or EGF). Progenitors of neurons and glial that migrated away from spheroids were then fixed and stained for Tuj1/BIII tubulin (neuronal) and GFAP (glia). Neurospheres were derived from Lin28a/b conditional double KO (cDKO, Lin28afloxed and Lin28bfloxed) Post-natal Day 7 brains. B) After sphere formation ex vivo, cultures were treated with Cre-GFP or CMV-GFP for at least 24 h and then allowed to spontaneously differentiate C) with the addition of 100 ng/ml BDNF for 3 days, fixed, and stained for Tuj1/BIII tubulin (neuronal marker, red) and Dapi (blue). D) Quantification of panel C, using BIII tubulin positive cells. E) FKPM of mRNA targets of Lin28a/b previously found in neural precursor cells (Balzer et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2015) in our lung-specific RNA-seq of the Lin28a/b dKO (n = 3) and WT (n = 2). F) Fold change of mRNAs found during polyribosome profiling in the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in brain (Herrlinger et al., 2019) compared to expression found in RNA-seq of the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in lung epithelium (Osborne et al., 2021).) G) FKPM of Sox genes from RNA-seq of the lung-specific Lin28a/b dKO/WT (n = 3). H) Sequence alignment of select Sox mRNAs performed in Clustal Omega. Numbers on the right represent nucleotide positions in the mRNA sequence. Blue boxes highlight similarities in sequences in the N-Terminal and C-Terminal. Red adenines are to aid identification of G-rich sequences. I) Predicted let-7 binding sites of putative and known Lin28-mRNA targets in TargetScan (Agarwal et al., 2015) https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/. J) QGRS scores (G-Scores) compared to total number of QGRS of SOX2, SOX4, and SOX11 mRNAs. Data values are means of±S.D. Scale bars for: B) and C) are 50um. Lungs for RNA-sequencing were isolated from two independent experiments. P values for all graphs were determined using Paired t-test for D) and 2-way ANOVA for E) and H), P values of significance: In the order of left to right for each panel: D)∗∗0.0026 H)∗∗0.0034,∗0.0372, ∗0.0213, ∗ 0.0433.

Genes previously identified to be downstream mRNA targets of both Lin28a and let-7 in the developing brain include components of the Igf2-mTOR pathways such as Igf2, Igf2r1 and the Igf2 binding proteins, Imps1,2,3 and Hmga2 [71,80]. We examined the expression of these mRNAs in our lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b. Formerly, we observed loss of Lin28a/b led to decreased expression of Hmga2 11, however, as we also previously observed, this was not dependent on let-7 expression. Interestingly, we did not observe significant changes in any of these previously identified mRNAs in the lung-specific knockout (Fig. 4E). Given the cooperative feedback and feedforward regulation between the epithelial and mesenchymal pathways in the lung, we also investigated the expression of mesodermal lineage transcription factors, from our lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b. In our whole lung lysates, we observed no change in mesodermal-promoting lineage transcription factors (Fig.S5).

Sox proteins (specifically groups SoxB, SoxD, and SoxE) are well known for their regulatory functions during central and peripheral nervous system development [81], in addition to the established roles of Sox2 and Sox9 in the developing lung epithelium [25,51]. Since our previous data demonstrated Lin28-mRNA binding to Sox2 and Sox9 in the lung, we investigated the other Sox proteins, particularly those from the SoxC group (comprised of Sox4, Sox11, and Sox12), which are also shown to regulate neuronal differentiation [82]. Brain-specific and lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b showed several Sox mRNAs (including Sox2, Sox9 and the SoxC group) being actively translated in polyribosome fractions in the brain and differentially expressed in the lung samples (Fig. 4F). Subsequent analysis of the SoxC group in the lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b demonstrated that Sox11 and Sox12 mRNA expression levels significantly decreased while Sox4 increased (Fig. 4G). Sequence alignments of Sox2, Sox4, Sox9, and Sox11 mRNAs revealed 5′UTR N-terminal clusters with relatively moderate guanine content (Fig. 4H). Only the Sox11 3′UTR C-terminus had low guanine content that aligned with the known mRNA targets of Lin28a/b protein and let-7-miRNA, including Imps1/2 and Hmga2, though Sox11 itself is not a predicted target of let-7-miRNA (Fig. 4I). Finally, we found that unlike Foxa2 and B-Catenin mRNAs, Sox2, Sox4, and Sox11 (which are all intronless genes) had higher QGRS scores in the C-terminus/3′UTR regions, although none were predicted targets of the let-7-miRNA (Fig. 4I and J). Altogether, while 3′UTR regions had higher QGRS scores, 5′UTR regions of Sox2, Sox4, and Sox11 still had moderate scores. This suggests since the post-transcriptional regulation via Lin28-RBPs at the 3′UTR and 5′UTR regions are not in competition with 3′UTR let-7-miRNA binding sites, that there may be other secondary functions yet to be discovered that enables refinement of Lin28-mRNA binding and regulation (Fig. 4J).

2.6. Lin28a and Lin28b mRNA are involved in positive regulatory loops with B-catenin, Sox2 and Sox9 transcription factors in vivo

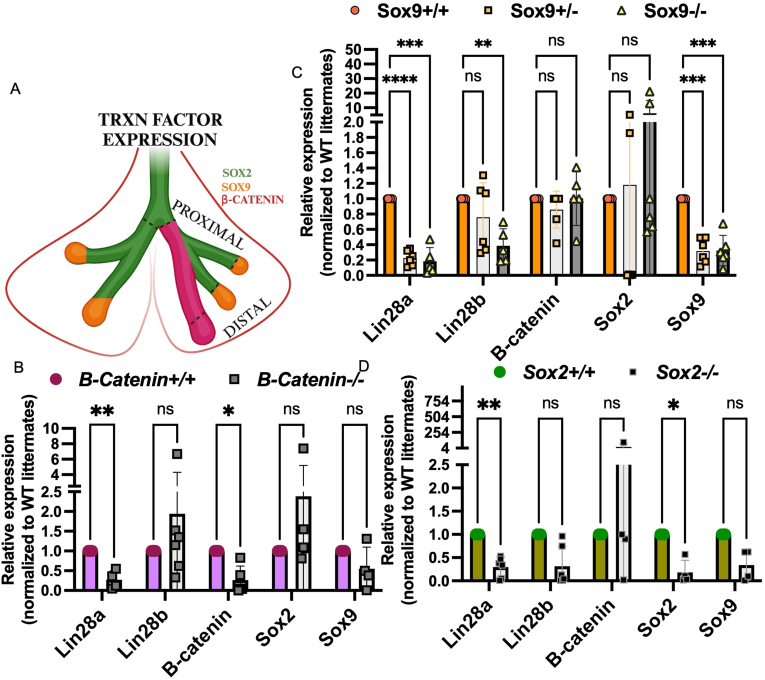

Previously, we observed that lung-specific dKO of Lin28a/b interrupted expression of Etv5, Sox2 and Sox9, and that Lin28a could bind directly to each of the mRNAs within the exonic regions [11]. Recently published data demonstrated that epithelial-specific knockout of B-Catenin led to decreased expression of Sox9 in distal tips, as well as branching defects [30]. Previously, we determined via gene set enrichment and gene ontology analysis that Wnt/B-catenin signaling was dysregulated in the Lin28a/b dKO lungs [11]. Considering we found B-Catenin was able to: 1) differentially regulate the LIN28A and LIN28B enhancer/promoter regions (Fig. 2G) and 2) dKO of Lin28a/b led to decreased Ctnnb1(B-Catenin) mRNA expression (Fig. 3E), we further investigated the presence of a feedforward regulatory loop between B-Catenin, Sox2, Sox9 and Lin28a/b mRNA in the lung epithelium in vivo. As formerly shown, Sox2/SOX2 marks the embryonic mouse and human proximal stalks, while Sox9/SOX9 and SOX2 marks the distal tip regions [50], however B-Catenin, like Nkx2-1 marks stalk and tips [16,30,62](Fig. 5A). Wnt/B-Catenin signaling is required for lung/foregut progenitor specification and for proper distal-proximal airway formation, as loss leads to proximalization of the lung via ectopic Sox2 expression [30,62]. Interestingly, loss of B-Catenin led to decreased expression of Lin28a but no change in the expression of Lin28b (Fig. 5B). Both heterozygous and homozygous loss of Sox9 led to a statistically significant decrease in the expression of Lin28a (Fig. 5C), and although homozygous loss of B-Catenin and Sox2 led to no significant change in Lin28b, homozygous loss of Sox9 led to considerable decrease in the expression of Lin28b (Fig. 5C). Taken together, our data suggests the heterochronic genes, Lin28a/b, control developmental transitions in early lung via enhanced mRNA stability and translation of key transcription factors that in turn transcriptionally upregulate Lin28a and Lin28b expression.

Fig. 5.

Developmental transcription factors whose mRNAs are regulated by Lin28 also regulate its expression in vivo. A) Schematic of the early developing lung, showing spatial expression of key transcription factors of the epithelium. Epithelial-specific knockout of B) B-catenin, C) Sox9, D) Sox2 driven by NKX2-1creER administered with tamoxifen at E10.5. Lungs were isolated between E11.5 and E12.5. RNA was extracted, qRT-PCR was performed for the following genes: Lin28a, Lin28b, Sox2, Sox9, and B-catenin. Data and error bars generated from Nkx2-1creER, B-cateninfl/fl n = 6 homozygous knockout and n = 4 Wild Type embryos fron 2 independent experiment; Nkx2-1creER; Sox9fl/fl n = 6 of heterozygous knockout, n = 6 homozygous knockout, n = 7, Wild Type embryos from 3 independent experiments; Nkx2-1creER; Sox2fl/fl n = 6 homozygous knockout n = 3 Wild Type embryos from 2 independent experiments. P values for the cKO of Sox2 and B-catenin graphs were determined using multiple t-tests; P values for cKo Sox9 were determined using 2-way ANOVA. P values of significance are in the order of left to right for each panel: B) ∗∗0.007, ∗0.045; C) ∗∗∗∗0.0001, ∗∗∗0.0009, ∗∗0.006∗∗∗0.0003, ∗∗∗0.0007 D) ∗∗0.00099, ∗0.003. Panel A made using BioRender.

3. Discussion

The evolution of multicellularity necessitated the emergence of tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells. These specialized cells, via their specification and subsequent differentiation, facilitate the exponential growth and maturation of the organism. Heterochronic pathways, such as the lin-28/let-7 axis, govern the timing and rate at which stem/progenitor cells stay in exponential growth phases, and when they exit to adapt different cell fates [3]. We and others have shown that during early organogenesis in mammalian embryos, let-7 miRNAs are not expressed until mid-gestation during the period when most stem/progenitor cells initiate differentiation [11,13,71]. During the early-to-mid gestational switch, Lin28 binds the stem-loop of the let-7's, obstructing their processing and subsequent expression until progenitors are ready to differentiate. During the mid-to-late gestational switch at the initiation of differentiation, let-7 in turn binds the 3′ UTRs of the Lin28 mRNAs to suppress their translation, allowing differentiation to proceed [[6], [7], [8]]. While there have been many investigations into the actions of the Lin28/let-7 axis during mammalian development, few have fully investigated the early actions of the Lin28 paralogs prior to let-7 expression [83]. One study of note demonstrated the actions of the Lin28 paralogs in obesity/diabetes-resistance were due to both let-7-independent and -dependent mechanisms [80]. Zhu et al. demonstrated that several mRNAs in the insulin/PI3K-mTOR signaling pathway could have their translation enhanced by Lin28a/LIN28B and be suppressed by the let-7 miRNAs. Our current study investigates the early transcriptional activation of Lin28a/b by the same factors we previously demonstrated to be direct mRNA targets [11]. Feedback/feedforward loops are critical during developmental transitions to ensure proper coordinated expansion and differentiation of tissue-specific progenitors. We have now shown that LIN28 expression is controlled during post-embryonic stages, particularly during lung/endoderm transitions in a transcriptional-posttranscriptional feedforward loop with several developmental transcription factors (Fig. 6). While we have compiled compelling data from our own work and others, further investigation into whether these interactions occur directly in vivo needs to be done.

Fig. 6.

(Top) Development Biphasic model of temporal gene regulatory loops whereby transcriptional upregulation of Lin28a/b by transcription factors feeds into enhanced mRNA stability and/or maintenance of these same transcription factors. (Bottom) During cancer initiation Lin28a/b are thought to be upregulated to suppress let-7 miRNAs, however whether additional mRNA feedbacks exist in other contexts remains to be determined. Figure made using BioRender.

Previously, we demonstrated that Lin28a could bind exonic regions of the mRNAs Sox2, Sox9, Etv5, Gli1, and Bmp4, in the lung, heart, brain, kidney, and liver [11]. The canonical Lin28a and Lin28b RNA binding motif GGAGAU is found to be conserved in both miRNA and mRNA, where the CSD preferentially binds “UGAU”, and the two CCHC zinc-finger domains have higher affinity for “GGAG” [84,85]. Recent studies indicate that the mass of RNAs bound by the LIN28 proteins in mammalian ESCs and human cancer cell lines are protein-coding mRNAs, not miRNAs [84]. However, while many human cancer cell lines have high expression of either LIN28A or LIN28B, many also have moderate to high levels of the let-7 miRNA family [86]. This complicated paradox is absent throughout early organogenesis, where we and others have demonstrated let-7 miRNAs are not fully expressed until mid-late gestation, at the onset of differentiation [9,11,13,16,71,87]. In addition to the spatiotemporal gene regulatory loops between LIN28 and downstream RNAs, we observed that in mRNAs specifically, there are 5′UTR and 3′UTR position-dependent post-transcriptional mechanisms that are used to fine tune developmental timing. A better understanding of the distinct mechanisms of how G-quartet 3D structures form at 5′UTRs compared to 3′UTRs in vivo could be harnessed to improve precision medicine during adult regeneration, particularly given the recently described actions of Lin28 in axonal regeneration [70].

4. Material and methods

4.1. Mouse models

All mouse experiments were conducted following the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Boston Children's Hospital and UT Southwestern Medical Center that is accredited by AAALAC. Generation of the Lin28 conditional double knockout [88] was as previously described [5,11,80]. The NKX2.1-creER (014552), Sox9 conditional KO mice (013106), Sox2 conditional KO (013093), Ctnnb1 conditional KO mice (004152) Sox2-GFP (017592), Tp53 conditional KO mice (008462) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CD1 mice were purchased from Charles River laboratories. Developmental mice used in the study were embryonic ages during E11.5-E15.5. Tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich, 579000) was diluted in corn oil to 20 mg/ml and administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.068 mg/g per mouse weight in grams and at E10.5–11. Wildtype littermate controls (without expression of Cre recombinase or with Cre alone) were used for all experiments.

4.2. Cell culture

Embryonal ovarian PA-1 teratocarcinoma cells (CRL-1572), normal embryonic WI-38 (CCL-75) lung fibroblast, and HEK293 cells (CRL-1573) purchased from ATCC were maintained in DMEM+10 %FBS at 37° and 5 %CO2. HEK293 Cells were transfected with all plasmid constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668019) and lysed using Passive Lysis buffer (Promega, E1941) for luciferase assay or TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026) for downstream mRNA analysis. WI-38 cells were infected with adenovirus purchased from Vector Biolabs see table S3.

4.3. qRT-PCR, RNA-sequencing and analysis

RNAs were isolated from lungs and cell lines using TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026). For mRNA analysis, cDNA was prepared from 2 μg RNA using miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen, 218160) for high throughput analysis and 5 μg RNA using iScript™ Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, 1725037). For qRT-PCR, primer oligos for Lin28a (forward- AGC TTG CAT TCC TTG GCA TGA TGG; reverse- AGG CGG TGG AGT TCA CCT TTA AGA) and Lin28b (forward-TTT GGC TGA GGA GGT AGA CTG CAT; reverse- ATG GAT CAG ATG TGG ACT GTG CGA) were synthesized by IDT. Primers for mRNAs [58]. The raw and analyzed RNA-seq data in detailed method is available through Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the ID GSE93571 as detailed in our previous manuscript [11]. Ribosomal profiling seq data set_ GEO under accession number GSE131536 from manuscript [72]. Single-cell RNA sequencing data was acquired from GEO: GSE167011 from manuscript [64].

4.4. Reporter assays

Human LIN28A and LIN28B regulatory elements (including promoter, distal and proximal enhancers) were cloned from H1 human embryonic stem cell genomic DNA (Wi-Cell). Regulatory elements were defined by using UCSC genome browser ID: hg38 [89] and ChIP-seq deposited on UCSC genome browser of active histone marks, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 [42]. LIN28A/LIN28B elements were cloned: 3 kb to +2.5 kb for A; and -3kb to +2 kb from the transcriptional start site [90]. Promoter and enhancer fragments of LIN28 A/B (A-2kb, A+2 kb, A+2.5 kb; B-2 kb, B-13kb and B+2 kb) were PCR subcloned into the 5′KPNI-3′XHOI sites of pGL4.79-neomycin-Renilla luciferase, while the pGL4.50 CMV-driven-hygromycin-Firefly luciferase was used as control. Stable HEK293 cell pools expressing pGL4.49/pGL4.50 HEK293, selected in neomycin and hygromycin respectively, were used to screen and validate transcription factors (Table S1) that activated Renilla luciferase and increased mRNA expression of LIN28A and Lin28B. Dual luciferase activity was monitored using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, E1910), and results were normalized to GFP and empty vector expressing control samples. High-throughput reporter screen in HEK293 cells was performed on the BioTek Synergy HTX Multimode Reader (Agilent) using dual reagent injector kinetic assay mode. Screen analysis was done using Gen5 software (Agilent). Validation of luciferase reporter activity in regulatory fragments in PA-1 and HEK293 cells was performed on the Centro LB 963 microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies GmbH & Co.KG) and analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 10.

4.5. Neurosphere assays

Embryonic Brains from Post-natal Day 7 and E12-E14.5 from CD1, Lin28a/b conditional KO pups were dissected and dissociated in DNase I (0.5 mg/ml) then re-suspended in HBSS/L15 media (1:1). For generation of neurospheres, cells were plated at a density of 10,000–100,000 cell/well in Costar® 6-well Clear Flat Bottom Ultra-Low Attachment Multiple Well plate (Corning, 3471). All cells were re-suspended in DMEM/F-12: Neurobasal™ Medium (5:3 mix; Gibco, 21103049), bFGF (20 ng/ml; R&D systems, 3139-FB), N-2 Supplement (1 %; Gibco, 17502048), B-27 Supplement (2 %; Gibco, 17504044), β-Mercaptoethanol (Gibco, 21985023), 50 μM final. Self-renewal media (same as initiation) with addition of: EGF 20 ng/ml (R&D systems, 2028-EG), chicken egg extract 10 %. Differentiation media: DMEM/F12: Neurobasal™ Medium (5:3 mix; GIBCO), FBS 5 %, bFGF (10 ng/ml), N-2 Supplement (1 %), B-27 Supplement (2 %), β-Mercaptoethanol, 50 μM final with or without BDNF 50–100 ng/ml (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-4554). Neurospheres grown for 2–3 days in differentiation media were then dissociated and additionally grown in BDNF 50–100 ng/ml for 3–5 days. Lin28a/b were knocked out post-neurosphere formation via adenoviral infection with Ad-Cre-GFP adenovirus (Vector Biolabs, 1700) or Ad-GFP adenovirus (Vector Biolabs, 1060).

4.6. Sequence alignment and QGRS mapper

RNA Sequence alignments and analysis of guanine (G)-rich (G-rich) regions predicted to be LIN28-mRNA/miRNA binding sites was performed using the FASTA/NCBI of human mRNA sequences below: NC_000009.12:94175957–94176036 Homo sapiens chromosome 9, GRCh38.p14 Primary Assembly (MIRLET7A1); NM_002701.6 Homo sapiens POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1), transcript variant 1, mRNA (OCT4); NM_024865.4 Homo sapiens Nanog homeobox (NANOG), transcript variant 1, mRNA; NM_003106.4 Homo sapiens SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2), mRNA; NM_003483.6 Homo sapiens high mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2), transcript variant 1, mRNA; NM_021784.5 Homo sapiens forkhead box A2 (FOXA2), transcript variant 1, mRNA; NM_001904.4 Homo sapiens catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1), transcript variant 1, mRNA (Beta-CATENIN); Z46629.1 Homo sapiens SOX9 mRNA; NM_003107.3 Homo sapiens SRY-box transcription factor 4 (SOX4), mRNA; NM_003108.4 Homo sapiens SRY-box transcription factor 11 (SOX11). Multiple sequence alignments were done using Clustal Omega: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo. Identification of novel compared to known G-rich motifs was done using the bioinformatics tool: http://bioinformatics.ramapo.edu/QGRS/to obtain G-scores. The G-rich motifs were identified using identification of G-tetrads in quadruplexes and then given a score based on the number of stable guanine-quadruplexes potentially formed.

4.7. Tissue preparation, immunostaining, and antibodies

Embryos were removed from timed pregnant mice that were anesthetized via the open-drop method of isoflurane exposure followed by cervical dislocation and/or ketamine/xylazine. Lungs were dissected and fixed in 10 % formalin overnight. For sectioned immunohistochemical staining, fixed lungs were moved to 70 % ethanol. The protocol for immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously published [91]. For immunofluorescent staining, fixed cells were incubated in blocking serum (PBS with 5 % normal donkey serum (Sigma Aldrich, D9663), and 0.5 % Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking serum at 4 °C overnight. The following day, the cells were washed with PBS three times at room temperature and then incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI diluted in blocking serum for 1 h at room temperature. Antibodies and reagents: Abcam; DAPI catalog no. D1306, Invitrogen; GFAP, catalog no. ab5804, lot 2388830, Millipore; BIII Tubulin/Tuj1, (clone 2G10) catalog no. MA1-118, Invitrogen.

Author contributions

J.K.O wrote the manuscript; M.F.O and S.F.L edited manuscript. J.K.O, I.T., M.F.O, E.S. S.B., C.G., B.K., R.G.R Performed experiments. E.L.R., help with bioinformatics analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

Children's Hospital of Boston has filed patent applications related to this work in the names of the: George Q. Daley, Alena V. Yermalovich, and J.K.O. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge George Q. Daley for mentorship and financial support via NIH R01GM107536. We would also like to thank, Patricia M. Sousa and Alena V. Yermalovich for assistance with maintenance of mouse colony and Areum Han for initial RNA-seq analysis of previous manuscript [11]; members of the Daley lab and Osborne lab, and Michael Reese for constructive reading of the manuscript. J.K.O. was supported as a post-doc by Burroughs Wellcome Fund, as a P.I. by the V Foundation V2021-028; CPRIT (Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas) start-up grant number, RR210016. S.F.L. was supported by Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Pre-doctoral Training Grant number, RP210041. B.K. was partially funded by CPRIT Post-doctoral Training Grant number, RP210041.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2025.102226.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

figs1.

UCSC genome browser-defined epigenetic marks of the LIN28A and LIN28B regulatory regions. A) Active histone marks, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 in H1 human embryonic stem cells (hESC)(Ernst et al. 2011) of putative regulatory sequences, determined via chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) in the UCSC genome browser (Perez et al. 2024). Assembly used was hg38 for LIN28A (chr1:26,406,455-26,417,607) RefSeq NM_024674.6 and LIN28B (chr6:104,950,183-104,964,925) RefSeq NM_001004317.4. Promoter denoted red; Proximal (Prox) enhancer sequences denoted orange; Distal (Dist) enhancer sequences denoted yellow. B) Cloning schematic of the regulatory sequences in panel A and Fig.1B. C) PCR-amplified DNA fragments of the LIN28A and LIN28B regulatory sequences corresponding to schematic drawn in panel B.

figs2.

Transcriptional regulation of LIN28A and LIN28B by developmental transcription factors. A) HEK293 were transiently transfected in 96-well format with the following factors: GFP (control), OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, NANOG, MYC, MYCN, SOX9, Intracellular cleaved NOTCH (ICN), B-CATENIN, HOXB4, HOXA9, NRSF/REST, FOXA2, FOXA3, and NKX2-1. RT-qPCR was conducted for human LIN28A and LIN28B (n=2 independent screening experiments in quadruplicate). B) Transient transfection of txrn factors into HEK293 with construct stably expressing dual luciferase construct; firefly and Renilla luciferase.

figs3.

FKPM gene expression values of Cyclins, Cyclin-dependent Kinases, and Wnt family members. Expression of genes found in RNA-seq of the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in lung epithelium A) Cyclin genes B)Cyclin-dependent Kinases C) Family of Wnt ligands [11].

figs4.

Characterization of the Lin28 double knockout in neural stem cells. A) Neurospheres were derived from Lin28a/b conditional KO (cKO, Lin28a and Lin28b floxed) E12 brains. After sphere formation ex vivo, cultures were treated with Cre-GFP or CMV-GFP then directed to differentiate with the addition of 100ng/ml BDNF for 5 days then fixed and stained for Tuj1/BIII tubulin (neuronal, pseudo-colored green) and GFAP (glia, red). Neurospheres derived from Lin28a floxed/ Lin28b floxed E12 whole brains expressing CMV-GFP control adenovirus or Cre-Recombinase adenovirus: B) BDNF-treated mechanically dissociated spheroids after 7 days in culture on TC-treated 96-well glass bottom plates with 50ng/mL of BDNF. C) Agarose gel of RT-PCR following Cre-adenoviral knockout of Lin28a and Lin28b. D) Quantification of Panel B. Scale bars =200um. E) Formed neurospheres treated with Cre-GFP or CMV-GFP for at least 24 hours and then allowed to differentiate with the addition of 100ng/ml BDNF for 3 days then fixed and stained for Tuj1/BIII tubulin (neuronal, red) . F) Quantification of Tuj1/BIII tubulin+ cells in Figs. 4C and 4D.

figs5.

FKPM gene expression values of genes that regulate mesodermal formation. Expression of genes found in RNA-seq of the Lin28a/b dKO/WT in lung [11].

Data availability

All data is publicly available.

References

- 1.Ambros V., Horvitz H.R. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–416. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNamara K.J. Heterochrony: the evolution of development. Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2012;5:203–218. doi: 10.1007/s12052-012-0420-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambros V. In: Heterochronic Genes. elegans C. II, nd, Riddle D.L., Blumenthal T., Meyer B.J., Priess J.R., editors. 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee R.C., Feinbaum R.L., Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinoda G., Shyh-Chang N., Soysa T.Y., Zhu H., Seligson M.T., Shah S.P., Abo-Sido N., Yabuuchi A., Hagan J.P., Gregory R.I., et al. Fetal deficiency of lin28 programs life-long aberrations in growth and glucose metabolism. Stem Cell. 2013;31:1563–1573. doi: 10.1002/stem.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piskounova E., Viswanathan S.R., Janas M., LaPierre R.J., Daley G.Q., Sliz P., Gregory R.I. Determinants of microRNA processing inhibition by the developmentally regulated RNA-Binding protein Lin28. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21310–21314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rybak A., Fuchs H., Smirnova L., Brandt C., Pohl E.E., Nitsch R., Wulczyn F.G. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viswanathan S.R., Daley G.Q., Gregory R.I. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vadla B., Kemper K., Alaimo J., Heine C., Moss E.G. lin-28 controls the succession of cell fate choices via two distinct activities. PLoS Genet. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan S.R., Powers J.T., Einhorn W., Hoshida Y., Ng T.L., Toffanin S., O'Sullivan M., Lu J., Phillips L.A., Lockhart V.L., et al. Lin28 promotes transformation and is associated with advanced human malignancies. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:843–848. doi: 10.1038/ng.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne J.K., Kinney M.A., Han A., Akinnola K.E., Yermalovich A.V., Vo L.T., Pearson D.S., Sousa P.M., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Tsanov K.M., et al. Lin28 paralogs regulate lung branching morphogenesis. Cell Rep. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang D.H., Moss E.G. Temporally regulated expression of Lin-28 in diverse tissues of the developing mouse. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2003;3:719–726. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yermalovich A.V., Osborne J.K., Sousa P., Han A., Kinney M.A., Chen M.J., Robinton D.A., Montie H., Pearson D.S., Wilson S.B., et al. Lin28 and let-7 regulate the timing of cessation of murine nephrogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:168. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08127-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cacchiarelli D., Trapnell C., Ziller M.J., Soumillon M., Cesana M., Karnik R., Donaghey J., Smith Z.D., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Zhang X., et al. Integrative analyses of human reprogramming reveal dynamic nature of induced pluripotency. Cell. 2015;162:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soufi A., Garcia M.F., Jaroszewicz A., Osman N., Pellegrini M., Zaret K.S. Pioneer transcription factors target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming. Cell. 2015;161:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimadamore F., Amador-Arjona A., Chen C., Huang C.T., Terskikh A.V. SOX2-LIN28/let-7 pathway regulates proliferation and neurogenesis in neural precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:E3017–E3026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220176110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai W.Y., Wei T.Z., Luo Q.C., Wu Q.W., Liu Q.F., Yang M., Ye G.D., Wu J.F., Chen Y.Y., Sun G.B., et al. The wnt-beta-catenin pathway represses let-7 microRNA expression through transactivation of Lin28 to augment breast cancer stem cell expansion. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:2877–2889. doi: 10.1242/jcs.123810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buganim Y., Faddah D.A., Cheng A.W., Itskovich E., Markoulaki S., Ganz K., Klemm S.L., van Oudenaarden A., Jaenisch R. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell. 2012;150:1209–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(!!! INVALID CITATION !!! 6,7).

- 20.Ang S.L., Wierda A., Wong D., Stevens K.A., Cascio S., Rossant J., Zaret K.S. The formation and maintenance of the definitive endoderm lineage in the mouse: involvement of HNF3/forkhead proteins. Development. 1993;119:1301–1315. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burtscher I., Lickert H. Foxa2 regulates polarity and epithelialization in the endoderm germ layer of the mouse embryo. Development. 2009;136:1029–1038. doi: 10.1242/dev.028415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monaghan A.P., Kaestner K.H., Grau E., Schutz G. Postimplantation expression patterns indicate a role for the mouse forkhead/HNF-3 alpha, beta and gamma genes in determination of the definitive endoderm, chordamesoderm and neuroectoderm. Development. 1993;119:567–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura S., Hara Y., Pineau T., Fernandez-Salguero P., Fox C.H., Ward J.M., Gonzalez F.J. The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain, and pituitary. Genes Dev. 1996;10:60–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minoo P., Su G., Drum H., Bringas P., Kimura S. Defects in tracheoesophageal and lung morphogenesis in Nkx2.1(-/-) mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 1999;209:60–71. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alanis D.M., Chang D.R., Akiyama H., Krasnow M.A., Chen J. Two nested developmental waves demarcate a compartment boundary in the mouse lung. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3923. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang D.R., Martinez Alanis D., Miller R.K., Ji H., Akiyama H., McCrea P.D., Chen J. Lung epithelial branching program antagonizes alveolar differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:18042–18051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311760110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gontan C., de Munck A., Vermeij M., Grosveld F., Tibboel D., Rottier R. Sox2 is important for two crucial processes in lung development: branching morphogenesis and epithelial cell differentiation. Dev. Biol. 2008;317:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tompkins D.H., Besnard V., Lange A.W., Wert S.E., Keiser A.R., Smith A.N., Lang R., Whitsett J.A. Sox2 is required for maintenance and differentiation of bronchiolar Clara, ciliated, and goblet cells. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herriges M., Morrisey E.E. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141:502–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostrin E.J., Little D.R., Gerner-Mauro K.N., Sumner E.A., Rios-Corzo R., Ambrosio E., Holt S.E., Forcioli-Conti N., Akiyama H., Hanash S.M., et al. beta-Catenin maintains lung epithelial progenitors after lung specification. Development. 2018;145 doi: 10.1242/dev.160788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y., Chen Y., Ito H., Watanabe A., Ge X., Kodama T., Aburatani H. Identification and characterization of lin-28 homolog B (LIN28B) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene. 2006;384:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouchi Y., Yamamoto J., Iwamoto T. The heterochronic genes lin-28a and lin-28b play an essential and evolutionarily conserved role in early zebrafish development. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li C., Sako Y., Imai A., Nishiyama T., Thompson K., Kubo M., Hiwatashi Y., Kabeya Y., Karlson D., Wu S.H., et al. A Lin28 homologue reprograms differentiated cells to stem cells in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moss E.G., Tang L. Conservation of the heterochronic regulator Lin-28, its developmental expression and microRNA complementary sites. Dev. Biol. 2003;258:432–442. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Z., Yu H., Zhao J., Tan T., Pan H., Zhu Y., Chen L., Zhang C., Zhang L., Lei A., et al. LIN28 coordinately promotes nucleolar/ribosomal functions and represses the 2C-like transcriptional program in pluripotent stem cells. Protein Cell. 2022;13:490–512. doi: 10.1007/s13238-021-00864-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogt E.J., Meglicki M., Hartung K.I., Borsuk E., Behr R. Importance of the pluripotency factor LIN28 in the mammalian nucleolus during early embryonic development. Development. 2012;139:4514–4523. doi: 10.1242/dev.083279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West J.A., Viswanathan S.R., Yabuuchi A., Cunniff K., Takeuchi A., Park I.H., Sero J.E., Zhu H., Perez-Atayde A., Frazier A.L., et al. A role for Lin28 in primordial germ-cell development and germ-cell malignancy. Nature. 2009;460:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature08210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faas L., Warrander F.C., Maguire R., Ramsbottom S.A., Quinn D., Genever P., Isaacs H.V. Lin28 proteins are required for germ layer specification in Xenopus. Development. 2013;140:976–986. doi: 10.1242/dev.089797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gundermann D.G., Martinez J., De Kervor G., Gonzalez-Pinto K., Larrain J., Faunes F. Overexpression of Lin28a delays Xenopus metamorphosis and down-regulates albumin independently of its translational regulation domain. Dev. Dyn. 2019;248:969–978. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shinoda G., De Soysa T.Y., Seligson M.T., Yabuuchi A., Fujiwara Y., Huang P.Y., Hagan J.P., Gregory R.I., Moss E.G., Daley G.Q. Lin28a regulates germ cell pool size and fertility. Stem Cell. 2013;31:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/stem.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Chandrasekaran S., Wu Z., Ficarro S.B., Yu C., Ross C.A., Cacchiarelli D., Xia Q., Seligson M., et al. LIN28 regulates stem cell metabolism and conversion to primed pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ernst J., Kheradpour P., Mikkelsen T.S., Shoresh N., Ward L.D., Epstein C.B., Zhang X., Wang L., Issner R., Coyne M., et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hovestadt V., Jones D.T., Picelli S., Wang W., Kool M., Northcott P.A., Sultan M., Stachurski K., Ryzhova M., Warnatz H.J., et al. Decoding the regulatory landscape of medulloblastoma using DNA methylation sequencing. Nature. 2014;510:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang T.C., Zeitels L.R., Hwang H.W., Chivukula R.R., Wentzel E.A., Dews M., Jung J., Gao P., Dang C.V., Beer M.A., et al. Lin-28B transactivation is necessary for Myc-mediated let-7 repression and proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:3384–3389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J., Vodyanik M.A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J.L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G.A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aggarwal S., Wang Z., Rincon Fernandez Pacheco D., Rinaldi A., Rajewski A., Callemeyn J., Van Loon E., Lamarthee B., Covarrubias A.E., Hou J., et al. SOX9 switch links regeneration to fibrosis at the single-cell level in mammalian kidneys. Science. 2024;383 doi: 10.1126/science.add6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balachandran S., Narendran A. The developmental origins of cancer: a review of the genes expressed in embryonic cells with implications for tumorigenesis. Genes. 2023;14 doi: 10.3390/genes14030604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Danopoulos S., Alonso I., Thornton M.E., Grubbs B.H., Bellusci S., Warburton D., Al Alam D. Human lung branching morphogenesis is orchestrated by the spatiotemporal distribution of ACTA2, SOX2, and SOX9. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018;314:L144–L149. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00379.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nikolic M.Z., Caritg O., Jeng Q., Johnson J.A., Sun D., Howell K.J., Brady J.L., Laresgoiti U., Allen G., Butler R., et al. Human embryonic lung epithelial tips are multipotent progenitors that can be expanded in vitro as long-term self-renewing organoids. eLife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.26575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rockich B.E., Hrycaj S.M., Shih H.P., Nagy M.S., Ferguson M.A., Kopp J.L., Sander M., Wellik D.M., Spence J.R. Sox9 plays multiple roles in the lung epithelium during branching morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:E4456–E4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311847110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheibner K., Schirge S., Burtscher I., Buttner M., Sterr M., Yang D., Bottcher A., Ansarullah, Irmler M., Beckers J., et al. Epithelial cell plasticity drives endoderm formation during gastrulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021;23:692–703. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooper F., Souilhol C., Haston S., Gray S., Boswell K., Gogolou A., Frith T.J.R., Stavish D., James B.M., Bose D., et al. Notch signalling influences cell fate decisions and HOX gene induction in axial progenitors. Development. 2024;151 doi: 10.1242/dev.202098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krude H., Schutz B., Biebermann H., von Moers A., Schnabel D., Neitzel H., Tonnies H., Weise D., Lafferty A., Schwarz S., et al. Choreoathetosis, hypothyroidism, and pulmonary alterations due to human NKX2-1 haploinsufficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;109:475–480. doi: 10.1172/JCI14341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soza-Ried C., Hess I., Netuschil N., Schorpp M., Boehm T. Essential role of c-myb in definitive hematopoiesis is evolutionarily conserved. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:17304–17308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004640107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goss A.M., Tian Y., Tsukiyama T., Cohen E.D., Zhou D., Lu M.M., Yamaguchi T.P., Morrisey E.E. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hawkins F., Kramer P., Jacob A., Driver I., Thomas D.C., McCauley K.B., Skvir N., Crane A.M., Kurmann A.A., Hollenberg A.N., et al. Prospective isolation of NKX2-1-expressing human lung progenitors derived from pluripotent stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2017;127:2277–2294. doi: 10.1172/JCI89950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herriges J.C., Verheyden J.M., Zhang Z., Sui P., Zhang Y., Anderson M.J., Swing D.A., Zhang Y., Lewandoski M., Sun X. FGF-Regulated ETV transcription factors control FGF-SHH feedback loop in lung branching. Dev. Cell. 2015;35:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacob A., Morley M., Hawkins F., McCauley K.B., Jean J.C., Heins H., Na C.L., Weaver T.E., Vedaie M., Hurley K., et al. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into functional lung alveolar epithelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:472–488 e410. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longmire T.A., Ikonomou L., Hawkins F., Christodoulou C., Cao Y., Jean J.C., Kwok L.W., Mou H., Rajagopal J., Shen S.S., et al. Efficient derivation of purified lung and thyroid progenitors from embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCauley K.B., Hawkins F., Serra M., Thomas D.C., Jacob A., Kotton D.N. Efficient derivation of functional human airway epithelium from pluripotent stem cells via temporal regulation of wnt signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:844–857 e846. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mucenski M.L., Wert S.E., Nation J.M., Loudy D.E., Huelsken J., Birchmeier W., Morrisey E.E., Whitsett J.A. beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40231–40238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong A.P., Shojaie S., Liang Q., Xia S., Di Paola M., Ahmadi S., Bilodeau C., Garner J., Post M., Duchesneau P., et al. Conversion of human and mouse fibroblasts into lung-like epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9027. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ori C., Ansari M., Angelidis I., Olmer R., Martin U., Theis F.J., Schiller H.B., Drukker M. Human pluripotent stem cell fate trajectories toward lung and hepatocyte progenitors. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li N., Zhong X., Lin X., Guo J., Zou L., Tanyi J.L., Shao Z., Liang S., Wang L.P., Hwang W.T., et al. Lin-28 homologue A (LIN28A) promotes cell cycle progression via regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), cyclin D1 (CCND1), and cell division cycle 25 homolog A (CDC25A) expression in cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:17386–17397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Que J., Luo X., Schwartz R.J., Hogan B.L. Multiple roles for Sox2 in the developing and adult mouse trachea. Development. 2009;136:1899–1907. doi: 10.1242/dev.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rawlins E.L., Clark C.P., Xue Y., Hogan B.L. The Id2+ distal tip lung epithelium contains individual multipotent embryonic progenitor cells. Development. 2009;136:3741–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.037317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y., Tian Y., Morley M.P., Lu M.M., Demayo F.J., Olson E.N., Morrisey E.E. Development and regeneration of Sox2+ endoderm progenitors are regulated by a Hdac1/2-Bmp4/Rb1 regulatory pathway. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nathan F.M., Ohtake Y., Wang S., Jiang X., Sami A., Guo H., Zhou F.Q., Li S. Upregulating Lin28a promotes axon regeneration in adult mice with optic nerve and spinal cord injury. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:1902–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang X.W., Li Q., Liu C.M., Hall P.A., Jiang J.J., Katchis C.D., Kang S., Dong B.C., Li S., Zhou F.Q. Lin28 signaling supports Mammalian PNS and CNS axon regeneration. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2540–2552 e2546. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang M., Yang S.L., Herrlinger S., Liang C., Dzieciatkowska M., Hansen K.C., Desai R., Nagy A., Niswander L., Moss E.G., Chen J.F. Lin28 promotes the proliferative capacity of neural progenitor cells in brain development. Development. 2015;142:1616–1627. doi: 10.1242/dev.120543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herrlinger S., Shao Q., Yang M., Chang Q., Liu Y., Pan X., Yin H., Xie L.W., Chen J.F. Lin28-mediated temporal promotion of protein synthesis is crucial for neural progenitor cell maintenance and brain development in mice. Development. 2019;146 doi: 10.1242/dev.173765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heslop J.A., Pournasr B., Liu J.T., Duncan S.A. GATA6 defines endoderm fate by controlling chromatin accessibility during differentiation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunter M.P., Wilson C.M., Jiang X., Cong R., Vasavada H., Kaestner K.H., Bogue C.W. The homeobox gene Hhex is essential for proper hepatoblast differentiation and bile duct morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2007;308:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kikin O., D'Antonio L., Bagga P.S. QGRS Mapper: a web-based server for predicting G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W676–W682. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O'Day E., Le M.T.N., Imai S., Tan S.M., Kirchner R., Arthanari H., Hofmann O., Wagner G., Lieberman J. An RNA-binding protein, Lin28, recognizes and remodels G-quartets in the MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNAs it regulates. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:17909–17922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.665521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilbert M.L., Huelga S.C., Kapeli K., Stark T.J., Liang T.Y., Chen S.X., Yan B.Y., Nathanson J.L., Hutt K.R., Lovci M.T., et al. LIN28 binds messenger RNAs at GGAGA motifs and regulates splicing factor abundance. Mol Cell. 2012;48:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gritti A., Parati E.A., Cova L., Frolichsthal P., Galli R., Wanke E., Faravelli L., Morassutti D.J., Roisen F., Nickel D.D., Vescovi A.L. Multipotential stem cells from the adult mouse brain proliferate and self-renew in response to basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1091–1100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01091.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Amen A.M., Ruiz-Garzon C.R., Shi J., Subramanian M., Pham D.L., Meffert M.K. A rapid induction mechanism for Lin28a in trophic responses. Mol Cell. 2017;65:490–503 e497. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]