Abstract

The demyelinating process in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection in mice requires virus persistence in the central nervous system. Using recombinant TMEV assembled between the virulent GDVII and less virulent BeAn virus cDNAs, we now provide additional evidence supporting the localization of a persistence determinant to the leader P1 (capsid) sequences. Further, recombinant viruses in which BeAn sequences progressively replaced those of GDVII within the capsid starting at the leader NH2 terminus suggest that a conformational determinant requiring homologous sequences in both the VP2 puff and VP1 loop regions, which are in close contact on the virion surface, might underlie persistence.

Recombinant Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses (TMEV) constructed by exchanging corresponding genomic regions between the virulent GDVII and less virulent BeAn or DA virus cDNAs have been used to map a determinant for virus persistence to the leader P1 sequences encoding the leader and capsid proteins (2, 4, 12, 18). However, reports regarding whether this determinant can be contributed only by the less virulent TMEV or whether highly virulent strains also contribute are conflicting (4, 18). Direct assessment of GDVII virus persistence is difficult because infected animals do not survive the acute period, even at low inoculation doses, e.g., 1 50% lethal dose (LD50) (8). Use of recombinant viruses for finer-scale mapping of pathogenetic determinants within the TMEV capsid where there is extremely tight packing of amino acids in protomers is needed but may be problematic, especially considering the large number of amino acids that differ between the parents. The recombinant nature of such constructs tends to result in nonviable or growth-compromised viruses (16, 19). We now provide further evidence supporting the localization of a persistence determinant to the capsid as suggested by McAllister et al. (12) and the existence of a conformational determinant within the capsid requiring homologous sequences in both the VP2 puff and VP1 loop regions, which are in close contact on the virion surface (5, 9, 10).

The leader P1 (capsid) region is responsible for persistence.

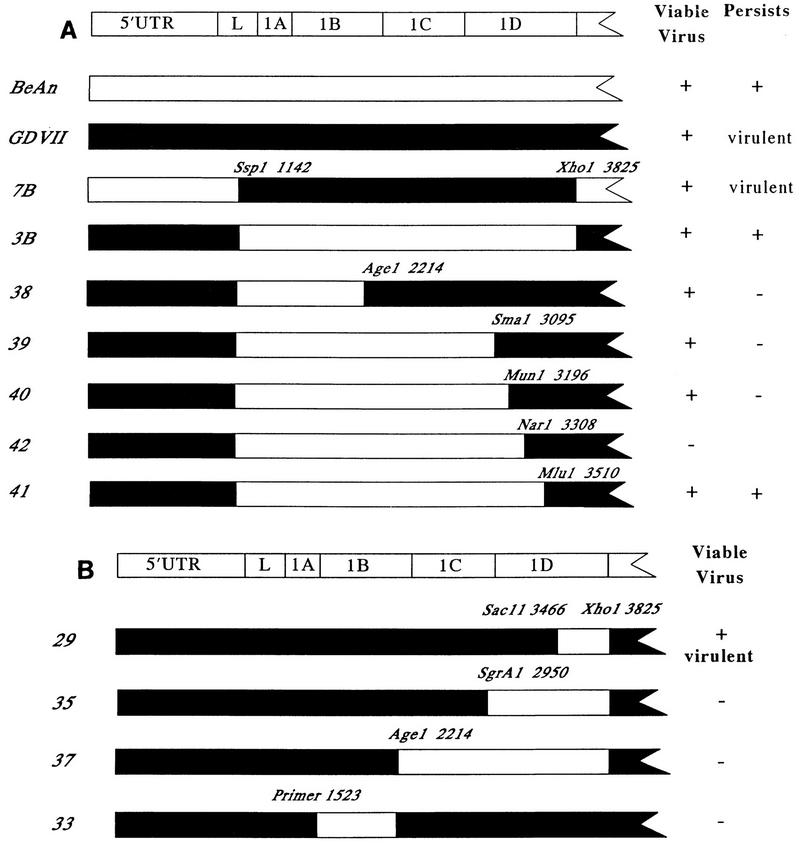

Eleven TMEV recombinants were assembled to map the central nervous system (CNS) persistence phenotype (Fig. 1). In recombinant 7B, the leader capsid genes of BeAn virus were replaced with those of GDVII by using restriction endonuclease sites SspI (within the NH2 terminus of the leader gene) and XhoI (at the 1D/2A dipeptide cleavage site). Recombinant 3B, which was constructed with the same restriction endonuclease sites, replaced the leader capsid genes of GDVII with those of BeAn virus. Recombinant 7B was neurovirulent, and no mice survived intracerebral (i.c.) doses of 103 PFU or more (LD50, ≤103 PFU). By contrast, recombinant 3B produced no deaths at an i.c. dose of 106 PFU (LD50, ≥106 PFU), and SJL mice inoculated with 3B developed virus persistence in the CNS and demyelination. This result supports a more precise localization of a TMEV persistence determinant to the leader P1 (capsid) sequences than earlier studies (12).

FIG. 1.

The genome structures of parental and recombinant TMEV. The organization of the TMEV RNA genome, showing the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), leader protein, and capsid proteins, is depicted at the top. Filled bars, the highly virulent GDVII virus sequences; open bars, the less virulent BeAn virus sequences. Recombinant cDNA clones were assembled in pGEM-4 downstream of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter by exchanging equivalent sequences from full-length parental clones (2, 16). Leader P1 (capsid) exchanges were in subgenomic clones with the restriction endonucleases shown here. Subgenomic constructs were assembled into full-length clones by using the unique XhoI site at 1D/2A and the ScaI site in pGEM-4. An XhoI site, which was absent in wild-type GDVII, was introduced by a T-to-C mutation by site-directed mutagenesis as described elsewhere (16). Recombinant 33 was made by PCR amplification and splicing by overlap extension to yield BeAn sequences between nucleotides 1523 and 2219 (6). The 10% difference in the nucleotide sequences of the two parental viruses enabled confirmation of the origin of all exchanged genomic parts by cleavage of cDNA clones with restriction endonucleases. In addition, the capsid sequences across splice sites in the recombinants and the 2376 BeAn nucleotides between the SspI and MluI sites in recombinant 41 were verified by PCR amplification and dideoxynucleotide sequencing of RNA isolated from viral stocks. (A) Parental viruses, recombinant viruses in which the GDVII and BeAn leader capsid regions were exchanged, and recombinant viruses that progressively replaced GDVII with BeAn sequences within the capsid starting at the SspI restriction endonuclease site in the NH2 terminus of the leader; (B) TMEV recombinants that progressively replaced GDVII with BeAn sequences within the capsid starting at the XhoI restriction endonuclease site at the 1D/2A cleavage site.

Intracapsid exchanges reveal a minimal BeAn persistence determinant.

To more finely map the persistence phenotype, additional BeAn leader P1 (capsid) exchanges were assembled on a GDVII background, with BeAn sequences progressively replacing those of GDVII capsid genes starting at SspI in the 5′ end of the leader (Fig. 1A). We hoped that a persistent recombinant would be obtained when the minimal BeAn determinant(s) of persistence was included. Recombinants 38, 39, 40, and 41 produced progeny virus upon transfection of BHK-21 cells and replicated in the mouse CNS (Table 1). Only CNS virus growth in mice inoculated with recombinant 40 was severely compromised, since these animals had virus titers that were >180-fold lower than those of BeAn virus-inoculated mice. Recombinant 42 was not viable upon transfection and could not be used for mapping. A complementary series of constructs was also generated in which BeAn sequences progressively replaced their GDVII counterparts starting at the XhoI site at the 3′ end of the capsid, e.g., recombinants 29, 35, 37, and 33 (Fig. 1B). However, all but one construct, recombinant 29, which was as neurovirulent as GDVII (data not shown), were nonviable and were not informative for mapping.

TABLE 1.

Acute virus titers in brains of mice inoculated i.c. with parental or recombinant TMEV

| Parental or recombinant virus | Titer fora:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | |

| GDVII | 4.5 × 106 (2) | |

| BeAn | 9.3 × 104 (3) | |

| 7B | 2.3 × 107 (2) | |

| 3B | 1.9 × 105 (3) | |

| 38 | 7.6 × 105 (4) | |

| 39 | 4.7 × 103 (2) | 5.0 × 104 (4) |

| 40 | 5.0 × 102 (3) | 8.2 × 101 (2) |

| 41 | 1.7 × 105 (3) | |

Mice were inoculated with 106 PFU of virus in the right cerebral hemisphere. Values are mean virus titers per gram of brain in mice killed on day 6 p.i. Numbers of mice are in parentheses.

In vitro growth characteristics of recombinant viruses.

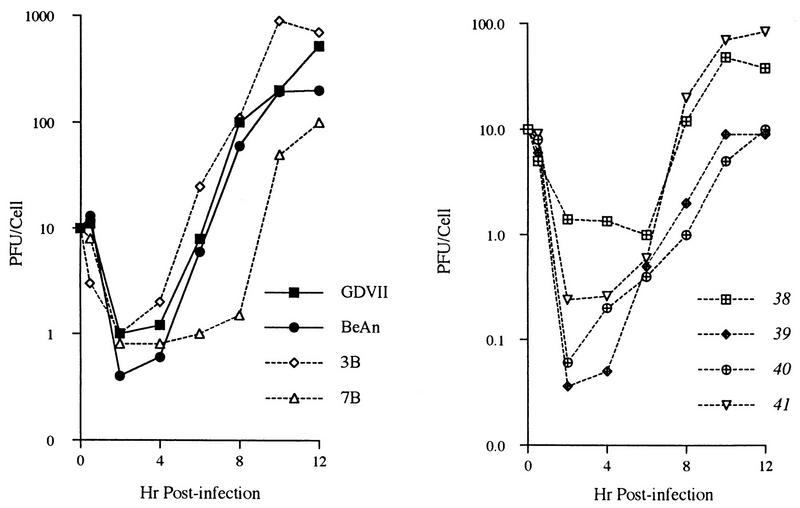

The progeny derived from the six recombinant constructs yielding viable viruses were assessed for plaque size, virus RNA replication, and growth kinetics. Recombinant 7B produced large plaques (>3-mm diameter), whereas 3B produced small plaques (<1-mm diameter). The four recombinants in which BeAn leader P1 (capsid) sequences progressively replaced those of GDVII on a GDVII background all produced smaller plaques, e.g., similar to those of BeAn virus. Recombinants 38 and 40 produced plaques that were slightly larger and much smaller, respectively, than those of the other two recombinants. Viral RNA replication (not shown) and one-step virus growth kinetics for recombinants 7B and 3B more closely paralleled those of the parent that contributed the nonstructural genes, e.g., the 3D RNA polymerase (Fig. 2A). Single-step growth kinetics for recombinants 38 and 41 were similar to that of BeAn, with final virus yields of 70 to 90 PFU/cell, whereas recombinants 39 and 41 were growth delayed, with final yields of 10 PFU/cell (Fig. 2B). This suggests that recombinants 39 and 40 are defective in RNA replication or virion assembly, as demonstrated for other GDVII-BeAn capsid recombinants (16).

FIG. 2.

One-step growth kinetics of GDVII and BeAn parental viruses and recombinant viruses in which the GDVII and BeAn leader-capsid regions were exchanged (A) and TMEV recombinants that progressively replaced GDVII with BeAn sequences within the capsid starting at the SspI site at the NH2 terminus of the leader protein (B). BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 and incubated at 33°C until the indicated times, when virus lysates were prepared.

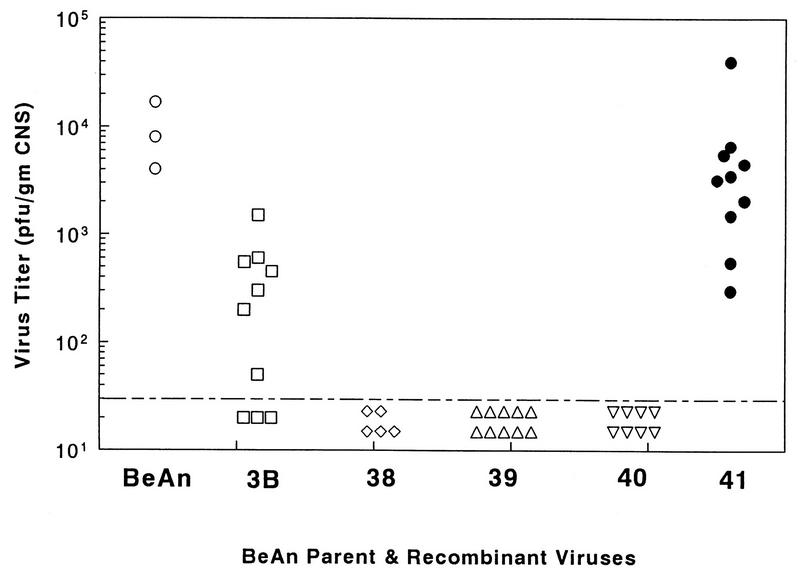

The minimal BeAn determinant for CNS persistence requires replacement of the entire capsid, excluding the carboxyl half of VP1 (1D).

Additional SJL mice were inoculated i.c. with parental BeAn, and the recombinant viruses and monitored to days 60 to 90 postinfection (p.i.) (Table 2; Fig. 3). Of 14 mice inoculated with recombinant 3B, 13 (92%) developed signs of chronic demyelinating disease, e.g., a waddling, spastic gait, tremors, and neurogenic bladders, and 3 of 3 mice examined had extensive inflammatory demyelinating lesions throughout the spinal cord. Infectious virus was detected in the CNS in 9 of 10 mice inoculated with 3B. None of the mice inoculated with recombinants 38 or 39 developed demyelinating disease or virus persistence and demyelinating lesions; however, rare mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates were seen in the spinal cord white matter. While 1 of 19 mice inoculated with the recombinant 40 developed demyelinating disease, none of 8 mice had evidence of virus persistence and only 1 of 10 had demyelinating lesions. The one clinically affected recombinant 40-inoculated mouse had extensive demyelinating lesions; spinal cord tissue from this paraformaldehyde-perfused animal was not available for virus assay. Considering the low acute CNS virus titers in recombinant 40-inoculated mice, it remains unclear why this single animal developed CNS persistence and demyelination.

TABLE 2.

Virus persistence and demyelination after i.c. inoculation of recombinant TMEV

| Parental or recombinant virus | No. of mice with the following results/total no. of mice:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute mortality | Chronic disease | Demyelinating pathology | Virus persistence | |

| BeAn | 0/4 | 4/4 | 3/3 | |

| 3B | 0/9 | 9/9 | 3/3 | 5/5 |

| 0/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | ||

| 38 | 7/10 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/1 |

| 3/4 | 0/1 | 0/1 | ||

| 1/5a | 0/4 | 0/4 | ||

| 39 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/2 | 0/5 |

| 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | ||

| 40 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 1/4 | |

| 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/2 | 0/3 | |

| 0/5b | 0/5 | 0/5 | ||

| 0/4b | 0/4 | 0/4 | ||

| 41 | 0/10 | 8/10 | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| 0/5 | 3/5 | 5/5 | ||

Tenfold lower dose resulted in less acute mortality.

DBA/2 mice were inoculated i.c. (all other infections were in SJL mice).

FIG. 3.

Virus titers in spinal cord homogenates from individual mice killed at approximately 90 days after i.c. inoculation with BeAn or recombinant viruses. The minimum detectable virus level of the assay is 50 PFU (dashed line).

In contrast, 11 of 15 (70%) recombinant 41-inoculated mice developed demyelinating disease, 4 of 4 mice examined had spinal cord demyelination, and 10 of 10 developed CNS persistence (Table 2; Fig. 3). The inflammation and demyelination in recombinant 41-inoculated mice were indistinguishable from those observed for parental BeAn virus-inoculated mice. Therefore, the minimal BeAn determinant for CNS persistence appears to require almost the entire replacement of the capsid, excluding the carboxyl half of VP1.

Finer mapping of the TMEV persistence phenotype by assembling recombinants in which GDVII was progressively replaced with BeAn starting in the leader showed that persistence was restored only when BeAn extended from the leader to approximately halfway through VP1 (169 of 276 VP1 residues replaced in recombinant 41). When BeAn sequences extended only into the NH2 terminus (30 of 276 VP1 residues replaced in recombinant 39) or one-fourth of the way through VP1 (65 of 276 VP1 residues replaced in recombinant 40), virus persistence was not observed. There are at least two interpretations of this result. First, one or more of the nine BeAn VP1 residues that are different in GDVII between the MunI and MluI restriction endonuclease sites might be required for virus persistence. Although the use of recombinants between virulent and attenuated parental viruses has served to map major pathogenic determinants in other picornaviruses to a single structural amino acid (1a, 3, 15, 17), there are relatively greater amino acid differences between GDVII and BeAn in the capsid (a total of 40 residue differences [14]), arguing against the possibility that a single residue underlies TMEV persistence. Nonetheless, we are currently testing this hypothesis by mutating these GDVII residues to their BeAn counterparts in the GDVII parent. Recombinants 29, 37, and 33, which progressively replaced the GDVII capsid with BeAn starting at the 1D/2A cleavage site and intended to resolve this issue, were either neurovirulent or nonviable. Similar GDVII-DA constructs replacing GDVII with DA sequences in VP1 have also been nonviable (1). A second possibility is that since BeAn sequences in the nonpersisting recombinants 39 and 40 ended upstream of the VP1 loops, whereas in the persisting recombinant 41 BeAn nucleotides extended through the VP1 loops, BeAn persistence depends on a conformational determinant that requires homologous sequences in the VP2 puff and VP1 loops, which closely interact on the virion surface (5, 9, 10).

The idea of a conformational determinant that may involve these surface loops is supported by recent observations on the persistence of another TMEV recombinant, GD1B-2C/DAFL3. This GDVII-DA recombinant virus, which is partially neurovirulent, persists in the CNS and produces demyelination (4, 18). GD1B-2C/DAFL3 contains GDVII sequences in the carboxyl half of VP2 (amino acids 152 to 267) and in VP3 and VP1 on a DA virus background and was constructed by using the NcoI site between the sequences encoding VP2 puff A and puff B. As a result, GD1B-2C/DAFL3 has a hybrid VP2 puff, with puff A containing DA sequences and puff B containing GDVII sequences. Recently, the GDVII NcoI-AatII or 1B-2C fragment was assembled into parental DA cDNAs constructed in different laboratories (11, 13). It was shown that VP2 residue 141 on the tip of puff A was a Lys in one construct and an Asn in the other (7). GD1B-2C/DAFL3 persisted only when DA VP2 141 was a Lys (7), highlighting the location of this residue within the VP2 puff. The fact that progeny derived from the DA parental clones persisted with either Lys or Asn in this position suggests that mutations in residue 141 in the recombinant affect the conformation of downstream GDVII sequences. Most likely, because of its proximity to VP2 puff B, mutation of residue 141 changes the conformation of VP2 puff B and, indirectly, that of the VP1 loops.

Our recombinant 38, in which BeAn sequences in the capsid were replaced by GDVII in the carboxyl terminus of VP2 (amino acids 237 to 267) and in VP3 and VP1, is similar to GD1B-2C/DAFL3, except that the NH2-terminal 24 amino acids of the leader protein are from GDVII and that the VP2 puff and downstream VP2 nucleotides are entirely BeAn. Recombinant 38 is also partially neurovirulent, but surviving mice do not develop persistent CNS infections. The reason for the difference in virus persistence between GD1B-2C/DAFL3 and recombinant 38 is not readily evident, since the 24 NH2-terminal, less-virulent residues in the leader protein are not required for persistence of GDVII-BeAn recombinant 3B (this study) or GDVII-DA recombinant R2 (12). However, changes in the region of the VP2 puff may affect the conformation of its other parts or that of neighboring structures, particularly VP1 loop 2, which interacts with VP2 puff B (5, 9, 10). For example, in BeAn, the carboxyl group of VP2 puff B Asp 170 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Arg 172 and the side chain of VP1 loop 2 Trp 95 (9). The latter is probably mediated by a water molecule. Similar VP2 puff B and VP1 loop 2 interactions are found in the GDVII and DA structures (5, 10). These surface loop interactions might well be altered in the recombinant viruses, yet general structural changes due to the recombinant nature of the constructs cannot be predicted from the parental structures. Such general structural changes may also affect a putative conformational determinant. However, perhaps the most persuasive argument for the involvement of a conformational determinant of the VP2 puff and VP1 loops in persistence is the fact that both GD1B-2C/DAFL3, which contains mostly GDVII capsid sequences, and recombinant 41, which contains mostly BeAn capsid sequences, cause CNS persistence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristi Jensen and Alastair Lynn-Macrae for technical assistance.

This research was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants NS 21913 and NS 23349 from the National Institutes of Health and The Leiper Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brahic, M. Personal communication.

- 1a.Caggana M, Chan P, Ramsingh A. Identification of a single amino acid residue in the capsid protein VP1 of coxsackievirus B4 that determines the virulent phenotype. J Virol. 1993;67:4797–4803. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4797-4803.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calenoff M A, Faaberg K S, Lipton H L. Genomic regions of neurovirulence and attenuation in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:978–982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filman D J, Syed R, Chow M, Macadam A J, Minor P D, Hogle J M. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 1989;8:1567–1579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu J, Rodriguez M, Roos R P. Strains from both Theiler’s virus subgroups encode a determinant for demyelination. J Virol. 1990;64:6345–6348. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6345-6348.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant R A, Filman D J, Fujinami R S, Icenogle J P, Hogle J M. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler’s virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2061–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton R M, Ho S N, Pullen J K, Hunt H D, Cai Z, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 1993;217:270–279. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarousse N, Grant R A, Hogle J M, Zhang L, Senkowski A, Roos R P, Michiels T, Brahic M, McAllister A. A single amino acid change determines persistence of a chimeric Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1994;68:3364–3368. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3364-3368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton H L. Persistent Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection in mice depends on plaque size. J Gen Virol. 1980;46:169–177. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-46-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo M, Cunheng H, Toth K S, Zhang C X, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (BeAn strain) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2409–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo M, Toth K S, Zhou L, Pritchard A, Lipton H L. The structure of a highly virulent Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (GDVII) and implications for determinants of viral persistence. Virology. 1995;220:246–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAllister A, Tangy F, Aubert C, Brahic M. Molecular cloning of the complete genome of Theiler’s virus, strain DA, and production of infectious transcripts. Microb Pathog. 1989;7:381–388. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAllister A, Tangy F, Aubert C, Brahic M. Genetic mapping of the ability of Theiler’s virus to persist and demyelinate. J Virol. 1990;64:4252–4257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4252-4257.1990. . (Erratum, 67:2427, 1993.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohara Y, Stein S, Fu J, Stillman L, Klaman L, Roos R P. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. Virology. 1988;164:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pevear D C, Borkowski J, Calenoff M, Oh C K, Ostrowski B, Lipton H L. Insights into Theiler’s virus neurovirulence based on a genomic comparison of the neurovirulent GDVII and less virulent BeAn strains. Virology. 1988;165:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pevear D C, Oh C K, Cunningham L L, Calenoff M, Jubelt M. Localization of genomic regions specific for the attenuated mouse-adapted poliovirus type 2 strain W-2. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:43–52. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchard A E, Jensen K, Lipton H L. Assembly of Theiler’s virus recombinants used in mapping determinants of neurovirulence. J Virol. 1993;67:3901–3907. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3901-3907.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren R B, Moss E G, Racaniello V R. Identification of two determinants that attenuate vaccine-related type 2 poliovirus. J Virol. 1991;65:1377–1382. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1377-1382.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez M, Roos R P. Pathogenesis of early and late disease in mice infected with Theiler’s virus, using intratypic recombinant GDVII/DA viruses. J Virol. 1992;66:217–225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.217-225.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Senkowski A, Shim B, Roos R P. Chimera cDNA studies of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus neurovirulence. J Virol. 1993;65:4404–4408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4404-4408.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]