Abstract

Background

It is important to engage family caregivers strategically and earlier in the Advance Care Planning (ACP) process. However, there is a lack of supportive information and education for family members on ACP. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a nurse-led motivational interviewing ACP intervention for family caregivers of older adults in nursing homes.

Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with a post-trial qualitative study (N = 50). Fifty family caregivers of nursing home residents in Hong Kong, China, were first recruited to the intervention group and then the control group in a 1:1 ratio. The intervention was a 3-session, nurse-led program with a motivational interviewing approach to improving their knowledge and understanding of ACP. The control group had no intervention. We evaluated feasibility outcomes with the logistics data and a semi-structured post-intervention qualitative interview and evaluated preliminary efficacy outcomes using the stages of change scale, the ACP readiness measurement, and a measurement of family caregivers’ quality of life before and after the intervention.

Results

The participation rate was 56%, and the overall attendance rate of the intervention group was up to 100%. Compared to the control group, the intervention group had significant increases in ACP knowledge, confidence, and stages of change for ACP activity score, except communication skills. Family members recognized their need for ACP information to be prepared as caregivers, and many reported the intervention improved their knowledge and attitude towards ACP and had a stronger desire to sign advance directives.

Conclusions

A nurse-led motivational interviewing intervention is feasible and effective for improving ACP readiness of family caregivers. Nurses play a vital role in preparing the family caregivers for end-of-life care decision-making for their loved ones. Our data inform future ACP interventions for family caregivers of older adults living in nursing homes.

Trial registration

This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the following registration number NCT05901506 on June 13th, 2023.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03853-9.

Keywords: Advance care planning; Motivational interview; Family caregivers; Geriatric care, older adults

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is an overarching process of proactive communication regarding end-of-life care among physicians, older adults with anticipated deterioration, and family caregivers and often involves the creation of a written document specifying personal wishes, a designated family member for future consultation, and preferences for personal care and life-sustaining treatments [1]. A systematic review and meta-analysis study of 56 studies demonstrated that ACP intervention significantly increased the likelihood of discussions regarding end-of-life preferences between patients and healthcare professionals and completion of advance directives compared with usual care [2]. A meta-analysis including 9 randomized controlled trials on ACP specifically among older adults living in nursing homes (n = 2905) indicated that ACP was effective in increasing discussion and documentation of end-of-life care preferences (SMD 2.27; 95% CI = 1.92, 2.69) [1].

Older adults living in the nursing homes rely on family caregivers for both physical care and emotional support. Family caregivers play a vital role in medical decision-making and the ACP communication process. Around 8.5% of older adults in Hong Kong live in nursing homes, and they are characterized by frailty and multiple comorbidities [2]. The 1-year mortality rate is 17.2% in nursing homes [3]. Most East Asian countries are influenced by Confucian-inspired family-centric beliefs, and family values and familial determination are often prioritized over patient autonomy and self-determination [4]. Thus, it is important to engage family caregivers strategically and earlier in the ACP process to equip them with knowledge and understanding of ACP and prepare them for the initial ACP discussion with older adults in a respectful way.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an effective counseling method for strengthening individuals’ internal motivation and resolving ambivalence toward behavioral change using such communication tools as open-ended questions, affirmation, double-sided reflective listening, and querying extremes [5]. The American Nephrology Nurse Association also recommends MI as an effective approach for engaging older adults on dialysis in ACP conversations [6]. A recent meta-analysis [7] also supported the effectiveness of MI-based ACP interventions for improving documentation rates of advance directive (OR: 2.79, 95% CI 1.89, 4.00) and power of attorney (OR: 3.56, 95% CI 2.35, 5.31) completion among English- and Spanish-speaking older adults [8].

Guided by the Dyadic Illness Management Theory [9], we hypothesize strengthening education and information support for family members of older adults can boost the family members’ readiness for supporting the ACP of older adults. This feasibility study aimed to explore the feasibility and acceptability of a nurse-led MI-ACP intervention for family caregivers of older adults in nursing homes in Hong Kong, to identify improvements for further rigorous testing in a larger-scale randomized controlled trial, and to conduct a preliminary assessment of its effectiveness. The research question of the study is what is the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a nurse-led MI-ACP intervention on the family caregivers’ ACP readiness?

Methods

Design

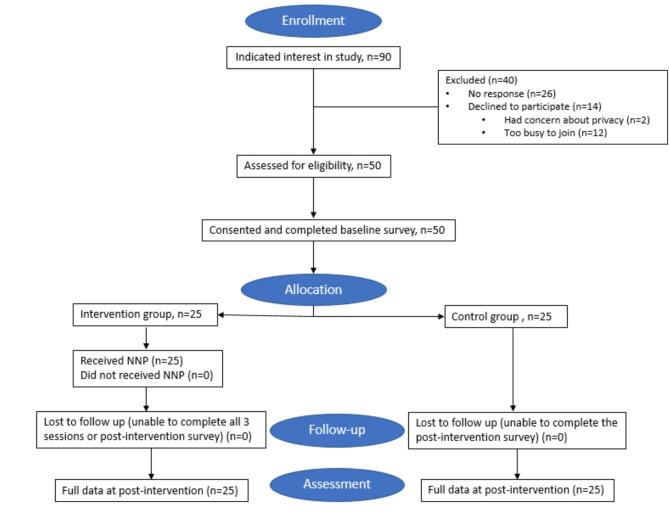

The study utilized a quasi-experimental design, including a non-randomized controlled pilot study and post-intervention qualitative study. The embedded qualitative study was utilized to explore the acceptability of the intervention. Due to the pilot nature of the study, there was no sample size calculation; we used convenience sampling to recruit over a six-month period. Figure 1 illustrates the study design flowchart. We followed the guideline of the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs [10]. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the following registration number: NCT05901506.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participants: recruitment, allocation, follow-up, and assessment. Note. ACP = advance care planning

Setting

Participants were recruited from five nursing homes and were first allocated to the intervention and then to the control group in a 1:1 ratio. The family caregivers in the intervention group received the MI-ACP intervention. The control group had usual care.

Participants

Family caregivers were included if they were [1] aged 18 or above; [2] identified by a resident aged above 65 years old in the nursing home as a family caregiver; and [3] able to read and write in Chinese. Family caregivers were excluded if they had: [1] moderate to severe cognitive impairment; [2] severe hearing impairment, defined as being unable to participate in a telephone conversation; [3] a primary language other than Cantonese or Mandarin; [4] no access to a telephone; [5] couldn’t read or write in Chinese; or [6] residents had a completed advance medical directive in the record.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (UW 22–586) on September 6th, 2022. All the study files were stored in the cloud storage service provided by the University of Hong Kong. The personal data of participants were anonymized using a study identification number. The study survey did not collect any identifiable information. Throughout the intervention delivery, the research nurse received guidance to refrain from documenting identifiable information in the intervention checklist.

Study procedure

Convenience sampling was used to recruit eligible family caregivers from the participating nursing homes. If interested, an information package encompassing an information sheet on the procedure would be sent to the person in charge. The research assistant identified and approached the nurse managers in nursing homes, who then introduced the study to the residents and their family caregivers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Family caregivers who expressed their interest gave the nurse manager permission to pass their contact information to our research assistant. Our research assistant contacted the prospective family caregivers to obtain their informed consent before completing the baseline questionnaire. Participants in the intervention group were all invited to share about their experiences in a semi-structured qualitative interview. Enrollment was ceased until data saturation was achieved.

Train the trainer

Training for research nurses followed a training curriculum adopted from the My Way program, an MI-based ACP training guideline developed by the American Nephrology Nurses Association [6]. The research nurses received training on ACP and MI using educational materials, lectures, and role-play simulation workshops. The curriculum included ACP training (8 h) by an experienced palliative care nurse specialist, the face-to-face MI training (20 h) by a certified MI trainer, and the intervention fidelity training (12 h).

The MI-ACP intervention (Table 1)

Table 1.

Motivational interviewing advance care planning intervention (MI-ACP intervention)

| Session One: Preparatory session | |

|---|---|

|

Setting: Telephone call Length: 10–15 min Materials: ACP educational pamphlet | |

| Steps and Motivational Interviewing (MI) Strategies | |

| 1.1 |

Welcome the family caregivers (5 MIN) • Introduce yourself • Value the family member’s individual views • Confidentiality statement • Answer questions |

| 1.2 |

Introduce the study and the concept of advance care planning (ACP) Inform: Introduce the 2019 ACP initiative from the HA and describe ACP in lay terms Listen: Allow time to share and offer reflective statements |

| 1.3 |

Value assessment Ask: Explore family caregivers’ previous experience with ACP. Elicit his or her own ideas and thoughts by asking exploratory questions and allow plenty of time to think and answer. Listen: Allow for the family member to tell his or her story without interruption. Offer reflective statements. Inform: If appropriate. Ask for permission to provide information and use examples of others |

| Session Two: Motivation session | |

|

Setting: Telephone call Length: 30–45 min Materials: ACP educational pamphlet & an advance medical directive form (AMD) | |

| 2.1 |

Assess readiness and knowledge on AMD Ask: Explore understanding of AMD Listen: Allow time to process by offering silence, if appropriate. Listen for statements such as “I want” and “I wish” and “I need.” Inform: With permission, offer information about AMD |

| 2.2 |

Elicit motivation, and explore barriers to ACP communication Ask: Explore motivation and identify communication barriers Listen: Allow the family member time to reflect on internal motivation Inform: with permission, offer tips to facilitate ACP communication with families (reiterate the positive impact of AMD; prepare the questions before the conversations; start with stories of other families or TV shows, and plan for multiple sessions) |

| 2.3 |

Facilitate discussion of treatment options in AMD Ask: Explore the family member’s readiness to discuss contents of AMD and respond, and roll with resistance Inform: Use pictorial handout to explain CPR, tube feeding, artificial respiration et al. Listen: Listen for change language, allow time to process |

| 2.4 |

Facilitate discussion on healthcare delegate Ask: assess family members’ thoughts/belief on healthcare agent Inform: provide information on why and how to establish healthcare agent Listen: allow time to process and respond with reflective and empathetic statements |

| Session Three: Planning session | |

|

Setting: Telephone call Length: 30–45 min Materials: ACP educational pamphlet | |

| 3.1 |

Review progress, resolve ambivalence and offer information on AD documentation Ask: Any questions or actions made since last meeting Listen: Go at the family member’s own pace. Use this meeting time to address what profess has been made and connect the family members to necessary resources and complete necessary paperwork in the office Inform: Provide websites on the AMD documentation process (Example of an AMD form and requirement of two witnesses) |

| 3.2 | Practice working on a draft AD |

| 3.3 |

Make up a step-by-step plan Ask: If the family member has any additional questions and if his or her loved one has a plan to complete his or her AMD Listen: Allow the family member time to process and respond, and offer reflective and empathetic statements Inform: With permission, possible opportunities to document AMD |

The team developed the intervention based on a review of existing literature [7]. Family caregiver participants received three counselling sessions: [1] preparatory session [2], motivation session, and [3] planning session. The preparatory session took 10–15 min, and the following two sessions were at weeks 2 and 3, with 30–45 min, respectively. The sessions were delivered via telephone. Telephone was selected as the most suitable approach, as family members were concerned about time and privacy with face-to-face meetings or had less familiarity with Zoom. Before each session of the MI-ACP, the research nurse first assessed the family caregivers’ readiness to engage in ACP based on the Stage-of-Change algorithm comprising the precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, or discussion stage. The maintenance stage is commonly measured six months after the discussion stage, and the discussion referred to active ACP discussion between the family members and their loved ones [11]; thus, it was not evaluated in this study. After the readiness-based ACP goals were established, the stage-matched MI counseling would be customized for each participant.

The preparatory session

The first session aimed to engage family caregivers and allow them to explore their personal values and feelings with ACP. This session was designed to support participants in managing their emotions related to ACP. The nurse first introduced the concept of ACP with a pictorial educational booklet [11] sent via WhatsApp to enhance readability [12], which was a 19-page infographic on ACP, advance directives, and Do-Not-Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation published by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority for patient and family member education. Then, she elicited and clarified family caregivers’ understanding of ACP and current engagement in ACP. Client-centered counselling skills, including open-ended questions, reflections, affirmations, and summaries, were used to facilitate the session.

The motivation session

The nurse explored family caregivers’ motivation to engage in ACP for their loved ones and provided customized information on end-of-life planning. Based on the recommended practice of MI, healthcare professionals should use information given only after assessing the individual’s knowledge and experience by asking and listening [13]. In MI, a more structured information exchange design is called Elicit, Provide, Elicit. In the evoking process, the nurse focused on eliciting family caregivers’ motivation to discuss end-of-life care with their loved ones, then by using specific MI strategies: [1] importance ruler [2], confidence ruler [3], develop discrepancy, and [4] envision, etc., to evoke seven types of change talk: desire, ability, reasons, need, commitment, activation, and taking steps.

The planning session

The nurse first helped to resolve family caregivers’ ambivalence and barriers in conducting ACP and explore some solutions. Next, the nurse worked with the family caregivers to form goals and came up with a step-by-step action plan for communicating ACP with health providers for their loved ones.

Outcomes & measures

Feasibility outcomes

The recruitment rate was calculated using logistics data. Intervention fidelity was evaluated by the nurses who completed a pre-designed fidelity checklist. Individual semi-structured interviews were held after the 3-week intervention with family caregivers in the intervention group regarding their experience of receiving the intervention.

Baseline characteristics

This was assessed by a survey on demographics, disease information, previous ACP-related experience, social support, and mental and physical health status at baseline.

Family caregivers’ readiness for ACP

This was measured in both groups before and after the intervention by a research assistant using the researcher-developed family caregivers’ ACP engagement survey (FACP-10), which consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The Traditional Chinese version of the FACP-10 was used in the study, and the English version of the measurement can be found in the Supplementary Materials A. The survey assessed family caregivers’ self-reported levels of ACP knowledge, readiness to discuss ACP with a loved one, self-efficacy in initiating ACP conversations with a loved one and barriers to such initiation, and emotional perceptions of and attitudes toward ACP, as well as whether they had the necessary communication tools for ACP conversations. A higher score indicates a higher readiness for ACP. We developed the instrument based on the key domains reported in the Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey [14] and the constructs identified in a systematic review of family caregivers’ roles in ACP [14, 15]. The FACP-10 demonstrated good internal consistency both prior to intervention (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) and after intervention (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Stages of change for ACP

The stage of change for ACP was using a single inquiry by the nurse before and after the intervention regarding stages of change based on the Transtheoretical Model, which is the widely accepted method for describing an individual’s readiness for ACP [16]. The Traditional Chinese version of the Stages of change for ACP was used in the study, and the English version of the measurement can be found in the Supplementary Materials B. Family caregivers who had never thought about ACP were in the pre-contemplation stage. Family caregivers who were willing to discuss end-of-life care were in the contemplation stage. Those who were ready to talk about end-of-life planning were in the preparation stage. Those who are actively taking the action to discuss ACP with their loved ones are in the discussion stage.

Family caregivers’ quality of life

As an individual’s caregiving capacity significantly impacts their quality of life [17], we assume quality of life as a potential confounder in the analysis and measure it at the baseline and the follow-up by research teams using a researcher-developed family caregivers’ quality of life questionnaire, which consists of six items in physical and psychological health and overall quality of life domains. All items are scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 10, with higher responses implying a higher quality of life. The pre- and post-intervention Cronbach’s alpha was 0.60 and 0.67 for the total scale and 0.88 and 0.91 for the subscale, respectively. The test-retest reliability was also examined at a 3-week interval with data reported by the control group and had a Pearson correlation of r = .78, p < .001, indicating sufficient reliability.

Post-trial interview

The interview was conducted by research assistants following an established interview guideline including 13 questions and an interview checklist to explore participants’ experiences with the MI-ACP intervention. Participants were asked to reflect on the following key aspects: motivation to participate, their understanding of ACP before joining the study, challenges of initiating ACP discussion with their loved ones, overall intervention design/delivery (content, timing, and format), strategies to improve the MI-ACP, and impact of the study on their ACP. To enhance validity and trustworthiness, the interview data were reviewed by checking if they corroborate with another data source (the MI-ACP intervention checklist collected by the research nurse) of the same participant.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ characteristics, study outcomes, and attrition rates. At baseline and post-intervention, descriptive statistics like means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges were presented for each outcome measurement. Scores of the continuous clinical outcomes were calculated, and normality checks were performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Two-way repeated‐measures ANOVA was conducted to detect changes from baseline to post-intervention, followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction. The Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical outcomes (stages of change). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. NVivo 12 was used to manage qualitative data (QSR International Pty Ltd, Burlington, MA). Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis with an inductive approach was adopted for data analysis [18].

Results

We screened and approached 90 participants for the study during the recruitment period (2022.12.1–2023.5.30), and all of them met the eligibility criteria, among whom 50 family caregivers agreed to participate. There was no adverse event related to participants’ emotion or ethical concern. The reasons some caregivers declined to participate were listed in the recruitment flowchart (Fig. 1).

Demographic characteristics

Table 2 showed the sociodemographic characteristics. Overall, half of the family caregivers were between the ages of 25 and 45; the majority (66.0%) were female and had a college education or above (90.0%). Most (72.0%) caregivers were children of the nursing home residents and currently working (84.0%).

Table 2.

Participants characteristics (N = 50)

| Variables | Intervention group (n = 25) | Control group (n = 25) | All (N = 50) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.272 | |||

| < 25 years old | 1 (4.0) | 5 (20.0) | 6 (12.0) | |

| 25 ~ 45 years old | 14 (56.0) | 11 (44.0) | 25 (50.0) | |

| 46 ~ 65 years old | 10 (40.0) | 9 (36.0) | 19 (38.0) | |

| > 65 years old | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gender | 1.000 | |||

| Male | 8 (32.0) | 9 (36.0) | 17 (34.0) | |

| Female | 17 (68.0) | 16 (64.0) | 33 (66.0) | |

| Education level | 1.000 | |||

| Primary | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | 5 (10.0) | |

| College or higher | 22 (88.0) | 23 (92.0) | 45 (90.0) | |

| Religion | 0.874 | |||

| None | 18 (72.0) | 15 (60.0) | 33 (66.0) | |

| Buddhism | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Christian | 4 (16.0) | 5 (20.0) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Catholic | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | |

| Traditional Folk Customs / Worship the Immortals | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.232 | |||

| Never married | 14 (56.0) | 19 (76.0) | 33 (66.0) | |

| Married or in a relationship | 11 (44.0) | 6 (24.0) | 17 (34.0) | |

| Divorced or separated | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Working status | 0.216 | |||

| Currently working | 19 (76.0) | 23 (92.0) | 42 (84.0) | |

| Unemployed, looking for a job | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | |

| Retired | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Student | 3 (12.0) | 0 | 3 (6.0) | |

| Other | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Monthly income | 0.925 | |||

| ≤ 15,000 Hong Kong Dollar | 3 (12.0) | 3 (12.0) | 6 (12.0) | |

| 15,000 ~ 25,000 Hong Kong Dollar | 9 (36.0) | 7 (28.0) | 16 (32.0) | |

| 25,000 ~ 40,000 Hong Kong Dollar | 5 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) | 10 (20.0) | |

| > 40,000 Hong Kong Dollar | 8 (32.0) | 10 (40.0) | 18 (36.0) | |

| Relationship with the older adult resident | 0.459 | |||

| Parent-Child | 17 (68.0) | 19 (76.0) | 36 (72.0) | |

| Grandparent – Grandchild | 6 (24.0) | 3 (12.0) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Spouse relationship | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | |

| In-law relationship | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | |

| Other | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (4.0) | |

| Accident &Emergency visit of the older adult resident in the past year | ||||

| No | 15 (60.0) | 17 (68.0) | 32 (64.0) | 0.769 |

| Yes | 10 (40.0) | 8 (32.0) | 18 (36.0) | |

|

Times (mean ± SD) once/11, twice/5, 3 times/1, 5 times/1 |

1.40 ± 0.70 | 1.88 ± 1.36 | 1.61 ± 1.04 | 0.350 |

p: level of significance, using Chi-Squared / Fisher’s exact test

Feasibility of enrollment

Of the 90 caregivers approached to participate, all were eligible (100% eligibility rate), and 50 agreed to participate in the study (56% participation rate). 25 caregivers were assigned to the control group, and 25 to the MI-ACP intervention. All 50 participants (100%) completed the pre- and post-intervention assessments, and all 25 intervention group participants received and completed all three sessions, resulting in a 100% overall attendance rate.

Fidelity of intervention

After every session with the participants, all research nurses completed the fidelity checklists (100%). A total of 25 fidelity checklists were completed, and all items on each checklist were reported as completed, indicating 100% compliance with the intervention protocol.

Family caregivers’ readiness for ACP

As shown in Table 3, the total score of the FACP-10 increased by 1.440 points from pre-intervention to post-intervention in the MI-ACP group compared with decreasing by 0.810 points in the control, while none of these changes were statistically significant. No significant difference was observed in the control group at both data collection timepoints. Notably, there was significant improvement of the intervention group in ACP knowledge, confidence, and readiness to engage in ACP, but not in communication skills compared to the control group.

Table 3.

Two-way repeated ANOVA for comparison of readiness for ACP scores at the two-time points between the intervention group and control group (N = 50)

| Intervention (n = 25) | Control (n = 25) | Between-group difference in change from baseline | Two-way repeated measures ANOVA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean Difference (Post-Pre) | P value | Mean ± SD | Mean Difference (Post-Pre) | P value | Mean Difference (I-C) | P value | Time p value | Group p value | Group × Time p value | |

| 1. I know what is ACP and what ACP involves. | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.40 ± 0.96 | - | - | 3.14 ± 1.11 | - | - | 0.257 | 0.403 | |||

| Post- | 4.40 ± 0.65 | 1.000 | < 0.001 | 3.10 ± 1.00 | -0.048 | 0.843 | 1.305 | < 0.001 | |||

| 2. I think having conversations on ACP with my loved one will have a positive impact. | 0.619 | 0.179 | 0.129 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.76 ± 1.05 | - | - | 3.62 ± 0.97 | - | - | 0.141 | 0.642 | |||

| Post- | 4.04 ± 0.89 | 0.280 | 0.137 | 3.48 ± 1.03 | -0.143 | 0.483 | 0.564 | 0.053 | |||

| 3. I think having conversations on ACP with my loved one will help me to take care of him/her. | 0.355 | 0.080 | 0.936 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 4.40 ± 0.65 | - | - | 4.10 ± 0.70 | - | - | 0.305 | 0.132 | |||

| Post- | 4.32 ± 0.75 | -0.080 | 0.531 | 4.00 ± 0.55 | -0.095 | 0.494 | 0.320 | 0.111 | |||

| 4. I think having conversations on ACP with my loved one will help him/her receive the care align with his/her wishes. | 0.546 | 0.069 | 0.805 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 4.32 ± 0.56 | - | - | 4.05 ± 0.59 | - | - | 0.272 | 0.115 | |||

| Post- | 4.28 ± 0.84 | -0.040 | 0.791 | 3.95 ± 0.59 | -0.095 | 0.564 | 0.328 | 0.141 | |||

| 5. I am emotionally ready to talk with my loved one on the topic of ACP. | 0.213 | < 0.001 | 0.325 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.72 ± 0.74 | - | - | 2.95 ± 1.20 | - | - | 0.768 | 0.011 | |||

| Post- | 4.12 ± 0.97 | 0.400 | 0.102 | 3.00 ± 1.18 | 0.048 | 0.856 | 1.120 | < 0.001 | |||

| 6. I do not feel comfortable of bringing up the ACP conversations with my loved one (reverse coded). | 0.638 | 0.076 | 0.638 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.80 ± 0.91 | - | - | 3.24 ± 1.14 | - | - | 0.562 | 0.070 | |||

| Post- | 3.64 ± 1.22 | -0.160 | 0.367 | 3.24 ± 0.94 | < 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.402 | 0.225 | |||

| 7. I am confident in initiating the conversations on ACP with my loved one. | 0.688 | < 0.001 | 0.688 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.88 ± 0.88 | - | - | 3.10 ± 0.89 | - | - | 0.785 | 0.004 | |||

| Post- | 3.88 ± 0.88 | < 0.001 | 1.000 | 3.00 ± 0.89 | -0.095 | 0.586 | 0.880 | 0.002 | |||

| 8. I have the communication skills to address the difficulty I might come across in the conversations on ACP with my loved one. | 1.000 | 0.032 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 3.64 ± 0.70 | - | - | 3.14 ± 1.06 | - | - | 0.497 | 0.064 | |||

| Post- | 3.64 ± 0.76 | < 0.001 | 1.000 | 3.14 ± 1.01 | < 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.497 | 0.064 | |||

| 9. I have concerns of talking about ACP with my loved one (reverse coded). | 0.943 | 0.594 | 0.414 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 2.96 ± 1.10 | - | - | 3.00 ± 1.10 | - | - | -0.040 | 0.903 | |||

| Post- | 3.12 ± 1.20 | 0.160 | 0.580 | 2.81 ± 1.03 | -0.190 | 0.546 | -0.310 | 0.357 | |||

| 10. I think I am the right person to discuss ACP with my loved one. | 0.238 | 0.209 | 0.787 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 4.08 ± 0.70 | - | - | 3.86 ± 0.91 | - | - | 0.223 | 0.354 | |||

| Post- | 3.96 ± 0.84 | -0.120 | 0.498 | 3.67 ± 0.80 | -0.190 | 0.325 | 0.293 | 0.234 | |||

| Total scores | 0.699 | 0.004 | 0.172 | ||||||||

| Pre- | 37.96 ± 5.20 | - | - | 34.19 ± 6.51 | - | - | 3.770 | 0.034 | |||

| Post- | 39.40 ± 6.67 | 1.440 | 0.195 | 33.38 ± 5.95 | -0.810 | 0.501 | 6.019 | 0.003 | |||

Note. Pre-: preintervention; Post-: postintervention

Family caregivers’ stages of change

As shown in Table 4, a Fisher’s exact test was adopted to compare the differences in the number of family caregivers in each stage before and after the intervention. There was a significant difference in the number of family caregivers in each stage at the two time points (χ2 = 19.741, p < .001).

Table 4.

Change in stage of readiness to engage in ACP (n = 25)

| Stage of Change (n, %) | Fisher’s exact test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- and Post-Test | PC | CON | PRE | DISCUSS | PLAN SET-UP | χ2 | P |

| Pre-intervention stage (n = 25) | 11 (44.0%) |

11 (44.0%) |

2 (8.0%) |

1 (4.0%) |

0 | 19.741 | < 0.001 |

| Post-intervention stage (n = 25) | 0 | 11 (44.0%) |

6 (24.0%) |

8 (32.0%) |

0 | ||

| Changes |

-11 (-44.0%) |

0 |

+ 4 (+ 16.0%) |

+ 7 (+ 28.0%) |

0 | ||

Note. PC = precontemplation stage, CON = contemplation stage, PRE = preparation stage, DISCUSS = discussion stage, PLAN SET-UP = plan set-up stage

Family caregivers’ quality of life

There was no significant difference in physical (p = .520) or psychological (p = .152) quality of life between the groups at two evaluation timepoints.

Qualitative findings

As shown in Table 5, three themes and seven subthemes emerged across ten family caregivers [19]. Thematic analysis revealed that most family caregivers were motivated to participate in the study to learn about ACP to help their family, were satisfied with the intervention design, and were shifting to a more positive attitude on ACP. In addition, participants recommended that the intervention could benefit more people if it were provided in fewer sessions and included more content on communication skills.

Table 5.

Summary of Post-Intervention qualitative interviews

| Themes | Subthemes | Representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation for Participation | Access to ACP information | ‘I learned about the study from nurses (4 participants) /social workers (6 participants) in nursing homes.’ |

| Purposes of Participation |

‘I want to have more information so that can take care of mom’ (Participant 1). ‘My mother was the most influential because of her health condition’ (Participant 2). ‘The reason why I participated is that I have an older relative who is persistently decline in physical function’ (Participant 3). ‘My participation is because of my family and I think that it is useful in future’ (Participant 4). |

|

| Perception of ACP | Knowledge Acquisition | ‘I knew a little bit before joining the study like what is end-of-life briefly, … after the counselling, I have more idea on end-of-life care and will start to think about it in the future’ (Participant 10). |

| Attitude Shift |

‘I Had a calm attitude as everyone has to experience it before the counselling, and after the counselling, where feasible, I will arrange instructions in advance so that future generations can follow our wishes’ (Participant 6). ‘I had no idea about ACP, and just would follow the preferences from deceased family members before the counselling. But after the counselling, I become positive toward this topic’ (Participant 8). ‘after the counselling, I have learned to reflect that whether some medical measures or treatments are suitable for the patient’ (Participant 9). |

|

| Behavior Change |

‘I would consider advance directives, but the laws of Hong Kong may not guarantee the feasibility of an advance directive scheme’ (Participant 5). ‘(The counselling) makes me want to sign an advance directive because if I sign it, I think that the elderly will feel better’ (Participant 10). |

|

| Experience with the MI-ACP intervention | Potential barriers to the MI-ACP |

‘The study was a little bit complicated, … can reduce the numbers of interviews as too many times’ (Participant 1). ‘The difficulty in this study was that the cognitive ability of my mom became worse during the study. … (before the study) there can be a brief introduction, so that we can more easily understand’ (Participant 3). ‘The difficulty in this study was the discussion with my mom’ (Participant 7). ‘(the intervention) can also be provided for family members as we don’t know how to communicate’ (Participant 10). |

| Potential facilitators to the MI-ACP |

‘All the contents of the conversation with the nurse are useful as the information can help to alert family members and myself’ (Participant 3). ‘This study provides leaflet information, which is suitable and easy to understand for participants who without medical background’ (Participant 9). |

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the feasibility of integrating MI and the Stages of Change framework in ACP facilitators, i.e., family caregivers. The study revealed that the MI-ACP intervention enhances family caregivers’ preparedness for facilitating ACP through two major pathways: [1] increasing ACP knowledge and [2] building the cognitive and emotional competency for ACP, such as confidence and readiness. Both pathways were supported by the quantitative data of family members’ changes in ACP readiness, knowledge, and confidence before and after receiving the MI-ACP intervention and their qualitative feedback. Our finding of empowering family members’ readiness for conducting ACP with their loved ones aligns with the foundational theoretical framework of dyadic illness management, which posits that enhancing the capabilities of one individual within the dyad will likely contribute to improved appraisal and collaborative management of health-related challenges [9].

This study highlights the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the MI-ACP intervention for family caregivers. Family caregivers’ role as an ACP facilitator has been acknowledged in the literature [20]; however, there is no intervention or guideline specifically on how to engage family caregivers. Our findings reinforce the existing knowledge that the family-centered ACP approach was more effective than usual care on completion of advance directives and health delegates [20, 21]. Our findings also underline the effectiveness of structured end-of-life discussion in combination with pictorial educational handouts in moving people toward a more positive attitude to engage in discussion and express emotions, which was also reported by Lautrette et al. [22]. Future ACP interventions targeting family caregivers should adopt a structured approach with pictorial pamphlets [23] or interactive educational technologies such as augmented reality or virtual reality [23] to support their decision-making.

In our qualitative interviews, we identified that misunderstanding of ACP is an impediment to ACP engagement. Some participants frequently associated ACP with final decisions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation, power of attorney, and/or living wills and felt that the ACP conversation was unnecessary at an early stage. This finding echoes a previous study that implemented standardized conversations about ACP with participants [25] and identified knowledge as both a facilitator and a barrier to ACP engagement. This phenomenon is also prevalent among the Asian population shaped by Confucianism, who tend to avoid talking about end-of-life planning with their parents, who have higher authority in a family, as it is considered as not giving enough respect and care. The dilemma faced by numerous Asian family caregivers is that raising the ACP conversations may lead to concerns of being perceived as unfilial by their parents. Conversely, if these conversations are not pursued, there may be no other opportunities to know their parents’ EOL preferences, particularly since Asian parents often refrain from discussing death with their children. It is essential to empower family caregivers in ACP to address this dilemma. A systematic review revealed that patients’ willingness to participate in ACP was impeded by their limited knowledge of ACP [24]; thus, enhancing individuals’ awareness regarding ACP is of significant importance.

Our findings of no significant change in family caregivers’ quality of life are consistent with a similar study [25], where those who had received an ACP intervention reported no change in quality of life. The reason for the small decrease in the quality-of-life scores of the intervention group may be that our intervention prompted family caregivers to carefully consider the older adult’s end-of-life care plan, which in part raised their concerns about their own health as well. Furthermore, improving quality of life may require elements not included in this ACP intervention, like content on self-care management.

We found that the stage of change algorithm was more sensitive in capturing the change of family caregivers’ readiness for ACP than the FACP-10 measurement. This finding broadly supports the work of other studies using stages of readiness for ACP [20]. A possible explanation for this is that most participants had never heard of ACP before joining the study, and following the three-week intervention period, they moved from contemplation to the active APC discussion stage. However, the FACP-10 measurement specifically targeted the technical skills and capacities demonstrated by individuals when conducting ACP with healthcare practitioners. This finding further underscores the urgent need to raise ACP awareness and initiate conversations on end-of-life care preferences at an early stage. Future research should choose the ACP outcome assessment according to the preparedness of the specific groups being studied.

The study has great implications for enhancing nurses’ role as ACP facilitators on practice and policy levels. First, nurses should know that ACP should be organized in multiple encounters to allow rapport-building and shifts in perception. Another implication is that early family involvement in their loved ones’ ACP is necessary to strengthen the caregivers’ knowledge, awareness, and sense of urgency around end-of-life decision-making. Before acting as an ACP facilitator, nurses should also be equipped with communication skills, such as using motivational interviewing skills as an icebreaker for sensitive topics like death and dying. Furthermore, future policy should emphasize the role of nurses as ACP facilitators and coordinators by integrating ACP training in nursing curricula and practice guidelines as a standard component of routine nursing care, given the increasing demand on ACP services in an aging population.

Limitations

Several limitations of the study must be acknowledged. The small sample size and short follow-up time point of the program limit our ability to evaluate the long-term impact of the MI-ACP intervention on the completion of advance medical directives or living wills. Secondly, the intervention group’s knowledge on ACP was higher at baseline than the control group, though not significantly different. We believe this limitation was compensated for by comparing the score change pre- and post-intervention, which significantly increased in the intervention group while decreasing in the control group. Thirdly, due to limited resources, instead of the gold standard of randomized controlled trials, our quasi-experimental design included a control group collected after the intervention group. The lack of randomization could cause environmental factors to impact the changes in the ACP outcomes, which were not controlled or collected for analysis. Fourthly, the intervention group’s knowledge on ACP was higher at baseline than the control group, though not significantly different. We believe this limitation was compensated for by comparing the score change pre- and post-intervention, which significantly increased in the intervention group while decreasing in the control group. Lastly, the qualitative analysis is prone to research subjectivity, which might limit the overall generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the effects of a nurse-led MI-ACP intervention in the family caregivers of nursing home residents in Hong Kong and showed satisfactory feasibility and preliminary effectiveness to help family caregivers initiate challenging conversations with the older adults. Our results indicate that family caregivers are willing to participate in this intervention and that the intervention has the potential to enhance caregivers’ readiness for ACP. Future large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the advantages of the MI-ACP intervention.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude for the diligent efforts of our research staff on the team (Elly, Ella, Jasmine and Jialing), as well as the support from study participants and the residential care homes.

Abbreviations

- ACP

Advance care planning

- MI

Motivational interviewing

- FACP

Family caregivers’ ACP engagement survey

Author contributions

T.W. and C.L. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. T.W. did the data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. T.W. and M.H. wrote the original manuscript. M.H. and C.L. provided expert support on the study and intervention design. N.T. supported the intervention development and training. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was founded by the Professor Chia-Chin Lin’s Endowment Professorship Fund in Nursing from the Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Charity Foundation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 22–586) and has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05901506). All participants provided informed consent. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants in the study.

Competing interests

The authors, TW, MH, and CL, declare no conflict of interest. While, the author, NT, acknowledges a possible conflict of interest as he received an honorarium (HKD19,900) for offering motivational interviewing training and intervention protocol review for the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ng AYM, Takemura N, Xu X, Smith R, Kwok JY, Cheung DST, et al. The effects of advance care planning intervention on nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;132:104276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luk JK. End-of-life services for older people in residential care homes in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2018;24(1):63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang MS, Lou WV, Kong ST. The provision of End-of-Life care in residential care homes for the elderly (RCHEs) as a feasible option to living and dying well for an ageing population (Policy no. 1). Hong Kong: Faculty of Social Sciences & Sau Po Centre on Ageing, University of Hong Kong; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng SY, Lin CP, Chan HY, Martina D, Mori M, Kim SH, et al. Advance care planning in Asian culture. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50(9):976–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1983;11(2):147–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson E, Aldous A, Lupu D. Make your wishes about you (MY WAY): using motivational interviewing to foster advance care planning for patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Nurs J. 2018;45(5):411–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tongyao W, Mu-Hsing H, Xinyi X, Hye Ri C, Chia-Chin L. Motivational interviewing to enhance advance care planing in older adults: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023:spcare–2023.

- 8.Izumi S. Advance care planning: the nurse’s role. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(6):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons KS, Lee CS. The theory of dyadic illness management. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):8–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics Committee. Advance Care Planning (ACP)? Advance Directives (AD)? Do-Not-Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR)? Patients and families should know more! 2019 [cited 2025 July 17th ]. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/psrm/Public_education2.pdf

- 12.Wang T, Voss JG. Effectiveness of pictographs in improving patient education outcomes: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2021;36(1):9–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rollnick S, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. 4th ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2023. p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, Howard M, Fassbender K, Robinson CA, et al. Measuring advance care planning: optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):669–81. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silies KT, Kopke S, Schnakenberg R. Informal caregivers and advance care planning: systematic review with qualitative meta-synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tan M, Ding J, Johnson CE, Cook A, Huang C, Xiao L, et al. Stages of readiness for advance care planning: systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates and associated factors. Int J Nurs Stud. 2024;151:104678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu S, Ding S, Wu S, Ma J, Shi Y. Correlations between caregiver competence, burden and health-related quality of life among Chinese family caregivers of elderly adults with disabilities: a cross-sectional study using structural equations analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2):e067296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canny AA-OX, Mason BA-O, Stephen JA-O, Hopkins SA-O, Wall L, Christie AA-O, et al. Advance care planning in primary care for patients with Gastrointestinal cancer: feasibility randomised trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72:e571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Wang T, Cheung DST, Chau PH, Ho MH, Han Y et al. Dyadic advance care planning: systematic review of patient-caregiver interventions and effects. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Liu X, Ho M-H, Wang T, Cheung DST, Lin C-C. Effectiveness of dyadic advance care planning: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;67(6):e869–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Fau - Megarbane B, Megarbane B, Fau - Joly LM et al. Joly Lm Fau - Chevret S, Chevret S Fau - Adrie C, Adrie C Fau - Barnoud D,. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.van der Kruk SR, Zielinski R, MacDougall H, Hughes-Barton D, Gunn KM. Virtual reality as a patient education tool in healthcare: A scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):1928–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martina D, Geerse OP, Lin C-P, Kristanti MS, Bramer WM, Mori M, et al. Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning: A mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework. Palliat Med. 2021;35(10):1776–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang ST, Chen JS, Wen FH, Chou WC, Chang JW, Hsieh CH, et al. Advance care planning improves psychological symptoms but not quality of life and preferred End-of-Life care of patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.