Abstract

Background

Sorghum, a diploid C4 cereal (2n = 2x = 20) with a 750 Mbp genome, is widely adaptable to tropical and temperate climates. As its center of origin and diversity, Ethiopia holds valuable genetic variation for improving yield and nutritional traits. This study aimed to identify and functionally characterize quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) linked to key agronomic and yield-related traits and their associated candidate genes.

Methods

Two hundred sixteen sorghum genotypes were evaluated over two seasons in northwestern Ethiopia using an alpha lattice design. Agronomic traits assessed included days to flowering, days to maturity, plant height, seed number per plant, seed yield, and thousand-seed weight. Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) generated 351,692 SNPs, with 50,165 high-quality markers retained. Candidate gene identification and functional characterization were carried out using a combination of bioinformatics tools and publicly available databases. Data normalization and analysis were conducted using META-R and SAS JMP. Linkage disequilibrium was assessed via TASSEL 5.0, and multi-locus genome-wide association study (ML-GWAS) identified significant QTNs (LOD ≥ 4.0) associated with phenotypic traits.

Result

This study investigates the genetic basis of key agronomic and yield related traits in sorghum by identifying QTNs associated with phenotypic variation. Descriptive statistics revealed notable variability in traits such as days to flowering (101 days), days to maturity (145.77 days), plant height (357.47 cm), seed number per plant (1808.92 count), seed yield (45.07 g), and thousand-seed weight (23.44 g). Correlation analysis showed strong relationships, particularly between days to flowering and maturity (r = 0.7058). ML-GWAS detected 176 QTNs across all 10 chromosomes, with 34 considered reliable Due to their consistent identification across multiple models. 117 candidate genes were mapped to these QTNs, associated with six major traits: 20 for flowering time, 16 for maturity, 16 for plant height, 17 for seed number per plant, 38 for seed yield, and 10 for seed weight. Key genes included Sobic.001G196700 (flowering time) and Sobic.005G176100 (stress responses). Two important regulatory genes, SbMADS1 and SbFT, were highlighted for their roles in flowering regulation. SbMADS1 influences days to flowering, while SbFT acts as a mobile signal integrating photoperiod cues. These genes are involved in starch and sucrose metabolism pathways, essential for energy storage and mobilization, thereby supporting improved growth and yield in sorghum.

Conclusion

This study highlights the complexity of trait inheritance shaped by diverse genetic factors and underscores the significance of major, stable, and unique QTNs for marker-assisted selection. Functional genome annotation revealed that candidate genes are involved in key biological processes and metabolic pathways, including starch and sucrose metabolism, secondary metabolism, and hormonal signaling.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12863-025-01350-1.

Keywords: Sorghum bicolor, Quantitative trait nucleotides, Genome-wide association study, Candidate genes, Metabolic pathways

Background

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench) is a vital cereal seed that serves as a staple food for millions of people in developing countries and is an important feedstock in livestock production [1]. Sorghum is a diploid C4 cereal with a chromosome number of 2n = 2x = 20 and a genomic size of 750 Mbp [2]. As an ancient seed, sorghum has broad adaptability and is cultivated extensively in tropical and temperate regions worldwide [3].

Ethiopia is recognized as a center of origin and diversity for sorghum, hosting a wealth of genetic variation for numerous traits [4]. This diverse germplasm offers valuable opportunities for gaining insights into the genetic architecture of key traits, which can enhance breeding programs for more efficient genetic improvement of sorghum and provide essential energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals in many households [5]. It is the 5th most significant cereal crop globally, following maize, rice, wheat, and barley [6].

Sorghum is crucial as a staple food for millions of people, especially in sub-Saharan Africa [7]. Sorghum is a particularly essential crop in Africa, second only to maize, as the staple seed for millions of people [8]. Owing to its drought tolerance, adaptability to diverse agroecological conditions, and high nutritional value, sorghum plays a critical role in food security and sustainable agriculture [9]. Sorghum is also prepared in various food products, such as porridge, bread, lactic and alcoholic beverages, and weaning meals [8]. Various biotic and abiotic factors challenge sorghum cultivation. Drought, heat stress, and soil salinity are significant abiotic constraints that impact yield and quality [10].

Yield is a polygenic trait shaped by various factors, including plant phenology, morphology, and physiological indices [11]. A thorough understanding of the genetic basis of these traits is crucial for effective manipulation, ultimately enhancing crop efficiency and resilience in the face of climate change [12]. Recent advancements in genomic technologies have facilitated multi-locus genome-wide association studies (ML-GWASs), enabling researchers to identify genetic variants associated with complex traits in sorghum [13]. GWAS leverages high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism markers across diverse sorghum germplasms to associate phenotypic data with genotypic information [14]. By analyzing multiple loci, researchers can uncover the genetic architecture of traits such as drought tolerance, disease resistance, and seed quality [10]. This approach has proven effective in understanding the polygenic nature of sorghum traits [15].

Over the past two decades, considerable efforts have focused on identifying genomic regions and quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with agronomic traits in sorghum through biparental linkage mapping [16]. However, this approach often yields low mapping resolution, limited allelic diversity, and population-specific QTLs, which impedes the practical application of biparental QTL findings in plant breeding [17].

The previous use of single-locus (SL-GWAS) methods has reduced genomic diversity in selected regions, limiting the ability to identify underlying loci for various traits in sorghum [18]. Additionally, SL-GWAS often struggles to detect the marginal effects of QTNs [19], making it challenging to identify multiple QTNs that effectively control complex traits in sorghum.

In genome-wide association studies (GWAS), single-locus models (SL-GWAS) test each SNP individually for trait associations but often overestimate SNP effects by neglecting background genetic variation and locus interactions [20, 21]. They are also prone to high false-positive rates due to insufficient control of population structure, kinship, and multiple testing [22], favoring common variants while overlooking rare ones and biasing results toward stronger signals. In contrast, multi-locus GWAS models evaluate multiple markers simultaneously, providing more accurate SNP effect estimates by considering the combined contribution of loci [23, 24]. ML-GWAS better controls confounding factors and improves the detection of rare or small-effect variants, preserving a broader representation of genetic diversity underlying complex traits.

To address these limitations, several multi-locus Genome-wide Association Study (ML-GWAS) methods have emerged as powerful tools for QTN detection and effect estimation, including mrMLM [25], FASTmrMLM [24], FASTmrEMMA [26], ISIS EM-BLASSO [27], pLARmEB [28], and pKWmEB [29]. These approaches have successfully revealed the genetic basis of important traits in various crop species, including maize [30], rice [31], and barley [32]. This study aimed to identify, map, and characterize QTNs linked to key agronomic and yield-associated traits in sorghum, assess the stability and uniqueness of these identified QTNs across diverse genetic backgrounds, and investigate candidate genes associated with them, emphasizing their gene ontology implications and metabolic pathways relevant to these traits.

Materials and methods

Plant genetic materials

A total of 202 diverse landraces and 14 improved varieties of 216 Ethiopian sorghum genotypes (Table S1) were found at the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute GenBank and the Melkassa Agricultural Research Center at the National Sorghum Improvement Center, respectively. The landraces were evaluated for key agronomic and yield-related traits in two cropping seasons from 2022/2023 to 2023/2024 and two environments, such as; Dangur (11.29218°N, 36.395667°E, Alt 1095 m.a.s.l.), and Pawi (11.316803°N, 36.4218°E, Alt. 1057 m.a.s.l.) Metekel zone in the northwestern regions of Ethiopia. The field trial was conducted via an alpha lattice arrangement with four blocks and two replications, and all the plant materials were planted at both sites over two years, with each plot net measuring 4.5 m², with an intra-row spacing of 0.75 m. Fertilizer was applied with the Ethiopian blanket recommendation of 100 kg/ha NPSZnB with 33 kg/ha UREA.

The phenotypic data were collected for traits such as days to flowering, days to maturity, plant height, number of seeds per plant, seed yield, and thousand-seed Weight. Specifically, days to flowering measure the time from planting until 50% of the plants in a plot begin to flower. days to maturity indicate the Duration from sowing until 95% of the plants reach harvest maturity. The plant height is the average height in meters from the ground to the top of the plant. The thousand-seed Weight is the Weight of one thousand randomly selected seeds, which are measured in grams, and the seed yield is recorded in g per plant and kg per hectare, also at 12.5% moisture content [33].

Phenotypic data analysis

Before phenotypic data analysis, we have used the Shapiro-Wilk statistics for normality and homogeneity test [34]. Correlation analysis, variance component estimation, and unrepresentative and missing data were imputed using SAS JMP V.5 [35]. The phenotypic traits were statistically evaluated using a Mixed Linear Model (MLM) framework in the asreml-R package [36]. The restricted maximum likelihood (REML) equation was structured as: y = Xτ + Zu + e, where y denotes the vector of observed trait measurements, τ corresponds to fixed effects (genotypes), X is the fixed-effect design matrix, u represents random effects (spatial components: columns and rows), Z is the random-effect design matrix, and e signifies the residual error vector.

Genetic variance components, including environmental variance (σ²e), genotypic variance (σ²₉), phenotypic variance (σ²ₚ), genotypic coefficient of variation (GCV), environmental coefficient of variation (ECV), phenotypic coefficient of variation (PCV), and broad-sense heritability (h²), were derived using the “variability” R package [37]. Genotypic variance (σ²₉) was computed as (MS₉ − MSₑ)/r, where MS₉ and MSₑ are the genotype and error mean squares, respectively, and r is the replicate count. Phenotypic variance (σ²ₚ) was calculated as the sum of genotypic and error variances  , with σ²ₑ equating to the error mean square (MSₑ). Broad-sense heritability (h²) was estimated using the formula:

, with σ²ₑ equating to the error mean square (MSₑ). Broad-sense heritability (h²) was estimated using the formula:

|

where n represents the number of replicates, following the methodology of [38]. Finally, best linear unbiased predictions (BLUPs)/best linear unbiased estimation (BLUEs) generated via the META-R package [39] were utilized as input for GWAS.

SNP genotyping

We conducted a GWAS using six multi-locus ML-GWAS models to identify major, stable, and unique quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) across the genome. LOD scores and R² values were calculated to evaluate the strength of the associations [40]. For this analysis, 216 Ethiopian sorghum landraces and improved varieties from the Purdue University sorghum repository https://purr.purdue.edu/publications/3189/1/ dataset were genotyped using the genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) method as described by [41]. The initial genotyping yielded 351,692 SNP markers, which were filtered by excluding those with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 5%, resulting in a final dataset of 50,165 high-quality SNPs.

LD analysis

Pairwise LD values, assessed through allele frequency correlations (r²) between each pair of SNPs, were estimated individually for each chromosome and across all ten chromosomes in TASSEL v.5 [42] utilizing a sliding window size of 50 bp [43]. The LD decay curve for each chromosome and the entire genome was filtered via a nonlinear regression model in R software [44, 45].

ML-GWAS analysis

ML-GWAS analyses were conducted via two environments’ field datasets: Dangure Village, 5, and Pawi Village. 7. The best linear unbiased estimation (BLUE) [46] of the genotypic values for six traits across the two environments and the combined dataset were estimated via the REML algorithm, as previously described [47]. Marker‒trait association analyses were performed via “mrMLMGUI” v4. 0.2 [25] ML-GWAS methods.

The kinship matrix (K), which estimates the level of relatedness among individuals, and population structure, were calculated internally using mrMLM.GUI R-package [25] ML-GWAS models. The principal component (PC) analysis was done using TASSEL 5 [43] on the 5 covariate groups. The population structure and kinship (K) matrices were incorporated into all the tested models to reduce the risk of false-positive associations and enhance the statistical power of the analysis. All parameters in the GWAS were set to default values, and we have incorporated population structure, kinship metrics, and principal components used for the analysis of the ML-GWAS. The critical threshold for significantly associated QTNs was established at the LOD value of ≥ 4.0 for all six multi-locus models, as detailed in prior studies [27]. The ML-GWAS analyses’ resulting (-log10 (P)) values were utilized to create Manhattan and QQ plots via the mrMLM. GUI package in R software [25].

Functional characterization of candidate genes

Candidate gene identification and genome-wide functional characterization were carried out using a combination of bioinformatics tools and publicly available databases. Initially, significant QTNs and associated genes were identified through six multi-locus GWAS models implemented in the mrMLM GUI R-software [25]. These significant loci were then used to mine candidate genes using ± LD (linkage disequilibrium) distance on the Sorghum QTLAtlas database [48] based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) thresholds. To explore colocalized QTLs, we employed the BioMaRt tool [49] and Ensembl Plants [50] along with the NCBI database. Functional annotation of the identified candidate genes was performed using QuickGO within the EMBL-EBI platform to determine their molecular functions, cellular components, and biological processes [51]. Additionally, comparative pathway analysis was conducted through Sorghumbase [52] and Phytozome database [53], which provided comprehensive insights into gene functions and metabolic pathways across a wide range of plant species, including Sorghum bicolor [54–56]. Colocalized QTN, QTL, and candidate gene mapping through the sorghum genome was done using MapChart v.2.32 [57].

Results

The mean days to flowering was 101, with a standard deviation of 12.29 days. The minimum and maximum values for days to flowering are 68.44 and 128.11 days, respectively (Table 1). This suggests a wide range of flowering times within the sorghum population. The mean days to maturity is 145.77, with a standard deviation of 8.24 days. The minimum and maximum values for days to maturity are 117.08 and 164.13 days, respectively. This finding indicates a similar range of maturity times as those observed for flowering (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of descriptive statistics

| Traits | df | Mean | Std Dev | Sum | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | 215 | 101.00 | 12.29 | 21815.80 | 68.44 | 128.11 |

| DM | 215 | 145.77 | 8.24 | 31486.80 | 117.08 | 164.13 |

| PH | 215 | 357.47 | 65.56 | 77213.30 | 144.48 | 464.28 |

| SNPP | 215 | 1808.92 | 240.47 | 390727.00 | 1374.06 | 2703.56 |

| GY | 215 | 45.07 | 8.72 | 9735.19 | 29.35 | 118.29 |

| TSW | 215 | 23.44 | 2.00 | 5062.16 | 17.47 | 29.66 |

DF days to flowering, DM days to maturity, PH plant height, SNPP number of seeds per plant, GY seed yield, TSW thousand-seed weight, N number of observations, df degrees of freedom, Min minimum, Max maximum

The mean plant height was 357.47 cm, with a standard deviation of 65.56 cm. The minimum and maximum plant heights were 144.48 and 464.28 cm, respectively. This suggests a diverse range of plant heights within the sorghum population. The mean number of seeds per panicle is 1808.92, with a standard deviation of 240.47. The minimum and maximum values for seeds per panicle are 1374.06 and 2703.56, respectively. This indicates a wide variation in the number of seeds produced by individual sorghum plants. The mean seed yield was 45.07 g, with a standard deviation of 8.72 g. The minimum and maximum seed yields are 29.35 and 118.29 g, respectively (Table 1). This suggests a substantial range of seed production among the sorghum genotypes. The mean thousand-seed Weight was 23.44 g, with a standard deviation of 2.00 g. The minimum and maximum thousand seed Weights were 17.47 and 29.66 g, respectively (Table 1). This finding indicates a relatively narrow range of variation in seed size within the sorghum population.

The scatterplots shown in Fig. 1 display varying degrees of correlation between the different traits, ranging from strong positive or negative relationships to more scattered, weaker associations. For example, the DF-DM plot demonstrated a strong positive correlation (r = 0.7058), suggesting that sorghum genotypes with longer days to flowering also tended to have longer days to maturity. The PH-GY plot shows a moderate negative correlation (r = −0.2172), indicating that taller sorghum plants may not necessarily produce higher seed yields. The SNPP-TSW plot exhibited a weak positive correlation (r = 0.0716), implying that the number of seeds per plant and the thousand-seed weight may not be closely linked in this sorghum population (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Correlation matrix of agronomic and yield-related traits in sorghum. Note: DF, days to flowering; DM, days to maturity; PH, plant height; SNPP, number of seeds per plant; GY, grain yield; TSW, thousand seeds weight

Analysis of variance for agronomic traits across environments

The analysis of variance revealed significant differences among sorghum genotypes and environments for most agronomic traits. Genotypic effects were highly significant (p < 0.001) for days to flowering (DF), days to maturity (DM), plant height (PH), and thousand-seed weight (TGW), indicating substantial genetic variability within the population for these traits and suggesting the potential for selection-based genetic improvement. However, genotypic effects were not significant for seed number per plant (SNPP) and grain yield (GY), implying that these traits may be more strongly influenced by environmental factors or may lack sufficient genetic variation within the tested genotypes. Environmental effects were highly significant (p < 0.001) for all traits, demonstrating that growing conditions across the three environments had a profound impact on trait expression. This reinforces the importance of multi-environment trials in evaluating genotype performance and stability. Traits like DF, DM, PH, and TGW showed both significant genotypic and environmental effects, suggesting they are influenced by both genetics and growing conditions, and can be effectively improved through selection. In contrast, the improvement of SNPP and GY may require more targeted environmental management or alternative breeding strategies due to their high environmental sensitivity and lack of strong genetic differentiation (Table S2).

Estimates of genetic parameters and selection potential for key agronomic traits in sorghum genotypes

The analysis of genetic parameters across six agronomic traits in sorghum genotypes revealed varying degrees of genetic control and selection potential. Days to flowering (DF) showed moderate heritability (50%) and relatively high genetic advance (GAM = 14.3%), indicating that selection for this trait could lead to substantial genetic gain. Days to maturity (DM) had low heritability (20%) and a low genetic advance, suggesting strong environmental influence and limited scope for genetic improvement through direct selection. Plant height (PH) exhibited moderate heritability (40%) and the highest GAM (20.3%) among traits with significant heritability, suggesting it is a good candidate for selection. Seeds per plant (SNPP) and grain yield (GY) showed negligible or negative genotypic variance and heritability (0% and 35%, respectively), with non-significant critical differences, implying a strong environmental effect and poor selection efficiency. Thousand-seed weight (TGW) displayed low heritability (10%) and modest GAM (6.3%), indicating limited improvement potential through selection. In general, DF and PH emerged as the most promising traits for genetic enhancement, while traits like SNPP, GY, and TGW may benefit more from improved agronomic practices or indirect selection strategies (Table S3).

Phylogenetic analysis reveals distinct genetic clusters

Phylogenetic tree for the evolutionary relationships between different groups or taxa within a species or genus of 216 sorghum landraces and improved varieties. In this case, the dendrogram depicts the phylogenetic relationships among sorghum genotypes or varieties. The dendrogram is circular, with the taxa or genotypes arranged around the circumference and the branches connecting them (Fig. 2). The branches’ length and relative positions indicate the genetic distances or evolutionary relationships between the different sorghum genotypes.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of sorghum landraces, improved cultivars and varieties, based on genetic relationships. Population grouping shows distinct cluster groups, such as Group I with orange color (52 genotypes), Group II green color (15 genotypes), Group III yellow color (93 genotypes), Group IV light blue color (23 genotypes), Group V blue color (32 genotypes), Group VI light green color (1 genotype)

In the phylogenetic tree analysis of 216 sorghum genotypes, the dendrogram appears to have multiple distinct clusters or groups of genotypes, which are likely to represent different subgroups or subpopulations within the sorghum species. By counting the number of clearly defined clusters or groups, we can identify approximately six clusters within this phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2).

ML-GWAS identified informative QTNs

To explore the genetic variants associated with our six agronomic and yield-associated traits, we performed ML-GWAS analysis via 50,165 high-quality SNP markers and BLUEs from two environments for two consecutive years. We have used six ML-GWAS methods, and 176 QTNs distributed on 10 chromosomes that are significantly associated with six agronomic and yield-related traits were identified based on the LOD score threshold value of ≥ 4. QTNs are significantly associated with the phenotype traits, and Manhattan and QQ plots of the ML-GWAS results are reported in (Fig S1) of the identified QTNs. Among the ML-GWAS methods, mrMLM resulted in the greatest number of significant QTNs identified (42), whereas FASTmrEMMA had the lowest number of QTNs (13).

The current QTN Linkage map revealed 117 genes distributed across 10 sorghum chromosomes (Fig. 3). Specifically, chromosome 1 contains 12 mapped genes, chromosome 2 has 16 genes, chromosome 3 features 20 genes, chromosome 4 has 11 genes, chromosome 5 includes 7 genes, chromosome 6 has 12 genes, chromosome 7 contains 4 genes, chromosome 8 features 7 genes, chromosome 9 has 14 genes, and chromosome 10 includes 13 genes. This QTN mapping encompasses six agronomic traits related to yield and yield-related characteristics in the sorghum genome. Notably, we identified 20 genes associated with days to flowering, 16 genes Linked to days to maturity, 16 genes associated with plant height, 17 genes associated with seed number per plant, 38 genes associated with seed yield, and 10 genes associated with thousand seed weight (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Genetic Linkage map for sorghum chromosomes 1-10 for agronomic and yield-related traits. The figure shows linkage groups and colocalization of mapped QTNs (see Table 4), highlighting new candidate genomic regions related to these traits. The color codes for the linkage map are as follows: black days to flowering; red days to maturity; green plant height; blue number of seeds per plant; yellow grain yield; and pink thousand-seed weigh

Putative candidate gene descriptions and functions of agronomic and yield-related traits associated with specific QTNs indicate a genetic basis for these phenotypic characteristics. For a flowering time, the gene Sobic.001G196700 on chromosome SBI-01 plays a crucial role, with a LOD score of 4.09 and an R² of 13.22, underscoring its significant impact on the trait. Concerning days to maturity, the genes Sobic.002G140900 and Sobic.005G176100 are linked to maturity and stress responses, respectively, with high LOD scores that suggest strong associations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) and candidate genes associated with key traits in sorghum

| Traits | QTNs | Chr | Candidate Genes | LOD | R² | Description | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | S1_1359747 | SBI-01 | Sobic.001G196700 | 4.09 | 13.22 | The gene involved in flowering time regulation | Regulates flowering time | [1] |

| S2_1162911 | SBI-02 | Sobic.002G183400 | 3.85 | 10.50 | Associated with floral development | Promotes floral organ formation | [2] | |

| DM | S2_54254801 | SBI-02 | Sobic.002G140900 | 4.16 | 2.68 | Regulates maturity traits in sorghum | Influences developmental timing | [3] |

| S5_14397024 | SBI-05 | Sobic.005G176100 | 4.30 | 5.75 | Associated with stress response mechanisms | Mediates stress tolerance | [4] | |

| PH | S3_63127731 | SBI-03 | Sobic.003G324400 | 4.06 | 4.63 | Plays a role in growth regulation | Regulates plant height | [5] |

| SNPP | S5_14397023 | SBI-05 | Sobic.005G176000 | 6.60 | 3.39 | Involved in seed development | Affects seed number | [6] |

| GY | S3_63127731 | SBI-03 | Sobic.003G324400 | 5.50 | 10.00 | Related to yield potential | Enhances grain yield | [3] |

| TSW | S4_51654024 | SBI-04 | Sobic.004G178300 | 4.38 | 3.10 | Influences seed weight regulation | Affects the weight of seeds | [2] |

References

1. Zhang, B. et al. (2023) Involvement of CONSTANS-like proteins in plant flowering and abiotic stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 16,585

2. Smith, E.S. and Nimchuk, Z.L. (2023) What a tangled web it weaves: auxin coordination of stem cell maintenance and flower production. J. Exp. Bot. 74, 6950–6963

3. Lee, Y.-J. et al. (2023) Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of the agronomic traits and phenolic content in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) genotypes. Agronomy 13, 1449

4. Browne, R.G. et al. (2021) Differential responses of anthers of stress tolerant and sensitive wheat cultivars to high temperature stress. Planta 254, 4

5. Kim, M. and Sung, K. (2023) Assessment of weather events impacts on forage production trend of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 65, 792

6. Johnson, K. (2023) Phenotyping Tools and Genetic Knowledge to Facilitate Breeding of Dhurrin Content and Cyanogenic Potential in SorghumColorado State University

The gene Sobic.003G324400 on SBI-03 regulates plant height, while both seed number and seed yield are connected to the same gene, highlighting its multifunctional role. The gene Sobic.004G178300 also influences thousand-seed weight, resulting in a moderate LOD score. The identified genes serve various functions, from flowering and maturity regulation to stress response and seed development. This highlights the complexity of traits influenced by multiple genetic factors. LOD measures the statistical significance of the associations between QTNs and traits. Higher LOD scores suggest stronger MTA associations. The R² represents the proportion of variance in the trait that the QTN explains. Values in the range of 2.68–13.22 indicate varying degrees of influence (Table 2).

Candidate gene description and functional analysis

Our findings align with previous research identifying genetic loci associated with sorghum flowering time and maturity traits. Studies [58] and [59] highlighted specific genes that regulate flowering time. Notably, the identification of Sobic.005G176100, which is linked to stress response mechanisms, may indicate a novel association underreported in the literature, reflecting an evolving understanding of stress-related traits. Furthermore, the overlap of genes associated with seed number and seed yield reinforces earlier findings that suggest a genetic connection between yield potential and reproductive traits.

Table 3 Provides QTNs associated with various traits, detailing their alleles, chromosomal positions, logarithm of odds (LOD) scores, and corresponding gene ontology (GO) analysis terms and KEGG pathways. Major QTNs: QTNs with significant LOD scores and R² values, indicating strong associations with traits; stable QTNs: QTNs consistently identified across multiple models and environments/studies; and unique QTNs: QTNs identified in this study but not reported in previous research.

Table 3.

Detailed description of major, stable, and unique QTNs. In this table, we have shown four major QTNs, four stable QTNs, and two unique QTNs

| Trait | QTN | Alleles | Chr | Position (bp) | LOD | R² (%) | Major QTNs | Stable QTNs | Unique QTNs | No of genes ± LD | GO Terms | KEGG Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | S1_73955151 | T/C | SBI-01 | 73,955,151 | 4.09–4.59 | 13.22–19.38 | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | GO:0007630 (flowering), GO:0009791 (fruit development) | KEGG: 40 (Plant hormone signaling) |

| DF | S2_6784036 | T/G | SBI-02 | 6,784,036 | 4.16–8.22 | 2.68–5.62 | No | Yes | Yes | 5 | GO:0010467 (gene expression), GO:0048574 (regulation of flowering) | KEGG: 44 (Plant‒pathogen interaction) |

| DM | S1_76529338 | A/G | SBI-01 | 76,529,338 | 4.45–9.13 | 5.14–19.59 | Yes | Yes | No | 5 | GO:0016042 (cellular response to stress), GO:0009651 (response to abiotic stimulus) | KEGG: 46 (Photorespiration) |

| PH | S1_67415907 | G/T | SBI-01 | 67,415,907 | 10.14 | 7.63 | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | GO:0009733 (response to auxin), GO:0010212 (plant height regulation) | KEGG: 53 (Plant hormone signal transduction) |

| GY | S10_60795709 | C/T | SBI-10 | 60,795,709 | 5.27–36.13 | 4.07–33.58 | Yes | Yes | No | 4 | GO:0009834 (grain filling), GO:0015960 (carbon compound metabolism) | KEGG: 12 (Starch and sucrose metabolism) |

Discussion

Linkage disequilibrium mapping, applications in GWAS and genomic analysis

Correlation heatmap of genetic variants (R² and P-values) highlights high-LD regions (red/orange blocks), revealing haplotype blocks with strongly correlated variants. The x- and y-axes denote genomic positions on chromosome 4 (Fig S2). Heatmap illustrating pairwise LD between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 4 of Sorghum bicolor. The upper triangle shows the LD values (R²), with color intensity ranging from white (R² = 0) to red (R² = 1.0), while the lower triangle indicates the statistical significance (P-values) of the LD, with green, blue, and white representing P-values < 0.0001, < 0.001, and > 0.01, respectively. SNP positions are denoted along the left axis, and haplotype block structures are indicated at the bottom (Fig S2). This visualization aids in identifying blocks of SNPs in strong LD, useful for association mapping and candidate gene identification.

Advancements in high-throughput genotyping and sequencing technologies have significantly enhanced the resolution and accuracy of linkage disequilibrium (LD) maps, offering deeper insights into the genetic architecture of complex traits [60]. These detailed LD maps, as illustrated in Fig. 3, are widely used in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to detect associations between genetic variants and phenotypic traits [61]. Understanding LD structure is essential for interpreting GWAS signals and optimizing follow-up experimental designs [62]. LD information also underpins genotype imputation techniques, which estimate untyped variants based on their correlation with nearby loci, thereby increasing the power and coverage of association analyses [63]. Computational advancements, including haplotype-based models and algorithms for identifying recombination hotspots, have further refined LD analyses [64]. In the LD plot (Fig. 3), strong LD is visualized along the diagonal in red, indicating regions where variants are commonly co-inherited, whereas areas shaded in blue or green suggest low LD and possible recombination hotspots, where variants segregate more independently. The color gradient reflects the pairwise R-squared (R²) values, ranging from 0 (no LD) to 1 (complete LD), providing a visual summary of genomic correlation patterns [62].

Identification of reliable QTNs associated with agronomic and yield-related traits

To ensure robust results, only QTNs detected by at least three ML-GWAS methods (mrMLM, FASTmrMLM, pLARmEB) across two independent analyses were retained. This stringent approach identified 34 reliable QTNs linked to six agronomic and yield-related traits (Fig S1). The Manhattan plot illustrates significant marker-trait associations (MTAs), and the QQ plot’s upper-tail deviation from the diagonal confirms true genetic associations. Among 36 total significant QTNs, 34 met the reliability threshold. Days to flowering (DF) and days to maturity (DM) each had six QTNs, predominantly on chromosome 2, with others on chromosomes 1, 3, 4, and 7. Plant height (PHT) mapped to four QTNs (chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 8), seeds per panicle (SNPP) to four (chromosomes 3, 9), and thousand-seed weight (TGW) to three (chromosomes 1, 2, 4). Seed yield (GY) displayed the highest complexity, with 13 QTNs distributed across seven chromosomes. Chromosome 2 emerged as a major locus for multiple traits, while the polygenic nature of GY underscores its intricate genetic basis in sorghum.

QTN mapping

QTN mapping is a genomic technique that identifies specific nucleotide variations that affect quantitative traits in organisms, particularly in crops and livestock [65]. These traits typically exhibit continuous variation, including plant height, yield, and disease resistance, and are influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors. Quantitative traits are assessed continuously and encompass various attributes, such as crop yield, plant stature, and fruit size. QTN mapping relies on genetic markers, such as SNPs, which are associated with specific traits and help trace the inheritance of these traits across generations [66]. This approach integrates observable phenotypic characteristics with genomic information to pinpoint markers linked to traits of interest. Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies have enabled rapid genotyping of large populations, thereby enhancing the identification of QTNs throughout the genome [67].

QTN mapping is vital for identifying and characterizing genomic regions associated with specific traits [68]. QTN provides insights into the genetic basis of complex traits by linking phenotypic variations to specific chromosomal regions [69]. QTN mapping, an extension of QTL mapping, focuses on pinpointing individual nucleotide polymorphisms contributing to phenotypic variation [70, 71]. Recent studies have identified major QTNs associated with critical traits such as seed yield, drought resistance, and disease resistance [72, 73].

Unique, stable, and major QTNs have been identified as essential agronomic traits in sorghum, including drought tolerance, seed quality, and plant height [13]. For example, the QTNs on chromosome 6 identified in this study have been linked to drought tolerance, providing a target for breeding efforts [71, 74]. These major QTNs often significantly affect phenotypic traits, making them valuable for marker-assisted selection [75, 76].

Identifying unique QTNs that significantly affect traits in specific environments can provide insights into the adaptability of sorghum to varying climatic conditions [3, 77]. reported that the discovery of unique and stable QTNs is crucial for developing new crop varieties that can thrive under fluctuating environmental conditions [48, 74, 78, 79]. The identification of stable and major QTNs contributes to the understanding of the genetic basis for key agronomic traits in sorghum, supporting previous findings that highlighted similar genetic loci associated with yield and stress tolerance [80].

Candidate gene identification and mapping for agronomic & yield related traits

Putative candidate gene mapping involves identifying genes likely to influence specific traits based on their known functions or associations with similar traits in other species [81, 82]. This approach has revealed several candidate genes linked to drought tolerance and disease resistance in sorghum [83, 84]. Recent studies have utilized comparative genomics and transcriptomics to increase the identification of candidate genes, leading to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying key traits [84, 85]. The functional annotations of candidate genes suggest potential pathways for targeted breeding efforts aimed at improving sorghum resilience and productivity (Table S4).

Table 4 shows the association between identified QTNs and candidate genes, along with their descriptions and functions. S1_73955151 colocalizes with SbMADS1, a MADS-box transcription factor that regulates flowering time and floral organ identity, influencing flowering development. S2_6784036 is associated with SbFT, the FLOWERING LOCUS T gene, which promotes flowering in response to photoperiod by integrating environmental signals. S1_76529338 links to SbDREB2, a dehydration-responsive element-binding protein that regulates stress-related gene expression under drought and salinity conditions. S1_67415907 is connected to SbGA2ox, which encodes a gibberellin 2-oxidase, playing a crucial role in plant growth and height regulation. S10_60795709 is related to SbAGL1, a gene from the AGAMOUS-LIKE family that is involved in fruit and seed development, impacting seed filling and reproductive structure development (Table 4).

Table 4.

Colocalization of Quantitative Trait Nucleotides (QTNs) with candidate genes associated with agronomic traits

| QTNs | Candidate Gene | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1_73955151 | SbMADS1 | A member of the MADS-box transcription factor family, involved in regulating flowering time and floral organ identity. | Influences the flowering time and the development of floral structures. |

| S2_6784036 | SbFT | The FLOWERING LOCUS T gene is a key regulator of flowering in response to photoperiod. | Promotes flowering, integrating environmental signals. |

| S1_76529338 | SbDREB2 | A dehydration-responsive element-binding protein involved in abiotic stress responses. | Regulates the expression of stress-related genes under drought and salinity. |

| S1_67415907 | SbGA2ox | A gene encoding a gibberellin 2-oxidase, which regulates gibberellin levels and plant height. | Involved in the control of plant growth and development, particularly height regulation. |

| S10_60795709 | SbAGL1 | A gene from the AGL (AGAMOUS-LIKE) family is involved in fruit and seed development. | Plays a role in grain filling and the development of reproductive structures. |

SbMADS1 Sorghum bicolor MADS-box gene-1, SbFT Sorghum bicolor flowering Locus-T gene, SbDREB2 Sorghum bicolor dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2, SbGA2ox Sorghum bicolor gibberellin 2-oxidase, and SbAGL1 Sorghum bicolor AGL (AGAMOUS-LIKE)-1

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of candidate genes

The functional characterization of candidate genes through Gene Ontology analysis provides insights into their biological roles [86, 87]. GO categories include biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components, which help define the involvement of these genes in various physiological and developmental processes [88, 89]. Candidate genes related to drought tolerance often participate in stress response mechanisms, such as the response to abiotic stimuli and the regulation of transcription [90]. Many candidate genes exhibit molecular functions such as protein kinase activity, transcription factor activity, and enzyme activity, which are crucial for signal transduction and metabolic regulation [91]. The cellular localization of candidate genes often involves components such as the nucleus, plasma membrane, and chloroplast, indicating their roles in cellular signaling and metabolic pathways [92].

SbMADS1 (S1_73955151) candidate genes

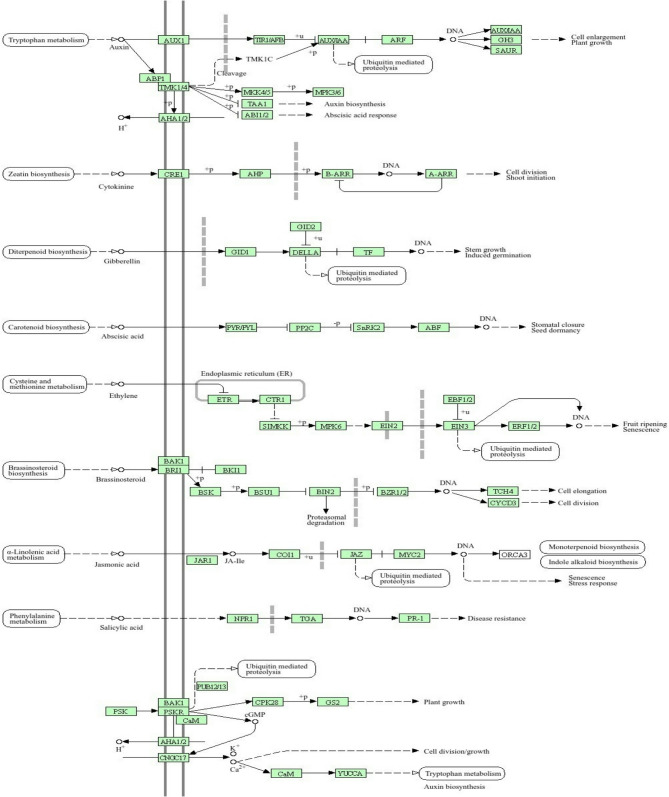

This gene is crucial for regulating flowering time by controlling the development of floral organs [93]. It is part of a relatively large family of MADS-box genes involved in various plant developmental processes (Table S4). This gene has potentially been found in sorghum SBI-01 (Table S4). As a transcription factor, SbMADS1 directly influences the expression of downstream genes that trigger flowering, making it essential for ensuring that flowering occurs under optimal environmental conditions. Figure 4 shows a graphical representation of the full annotation of the expressed gene ancestral chart GO:0007630 (flowering) and GO:0010467 (gene expression) in the EMBL-EBI database (Table S4). The gene SbMADS1 in (Fig. 4) is pivotal for plant hormonal signaling pathways, particularly in regulating flowering and developmental processes. It is integrated within a network of hormonal signals that influence key stages, including flowering initiation and maturation. SbMADS1 interacts with essential hormones such as auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins, mediating their effects on plant development.

Fig. 4.

Overview of plant hormone signal transduction pathways. The diagram illustrates the various plant hormone signal transduction pathways and their roles in regulating plant growth and development. The figure shows the expression of downstream genes critical for floral development and reproductive success, as indicated by activation or inhibition arrows

SbFT (S2_6784036) candidate genes

The FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene acts as a mobile signal that promotes flowering in response to long days. It is a key component of the flowering pathway that integrates photoperiodic signals. Here, a sorghum gene (SbFT) identified in this study, by promoting flowering, plays a vital role in determining the timing of reproduction, which is critical for the adaptation of sorghum to various environmental conditions (Table S4).

Furthermore, a schematic representation of the interactions between plant and pathogen factors (Fig. 5) highlights key signaling pathways and defense responses. Like animals, plants do not possess adaptive immunity; instead, they have developed a multilayered defense system against pathogens. The initial defense, known as PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), begins when cell-surface pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) detect pathogens (Fig. 5). This triggers the activation of the FLS2 and EFR receptors, which initiate the MAPK signaling pathway, leading to the expression of defense genes that produce antimicrobial compounds. An increase in the cytosolic Ca²⁺ concentration also plays a crucial role in generating reactive oxygen species and inducing localized programmed cell death, known as the hypersensitive response.

Fig. 5.

Plant-pathogen interaction and defense response mechanisms. This is a schematic representation of the interactions between plant and pathogen factors, highlighting significant signaling pathways and defense responses

The secondary defense mechanism is termed effector-triggered immunity [94]. Some pathogens can bypass PTI by directly injecting effector proteins into plant cells via specialized secretion systems. Additionally, they may exploit plant hormone signaling pathways, such as through the action of coronatine toxin, to evade immune responses. To counter this, many plants have evolved specific intracellular surveillance proteins, known as R proteins, which detect pathogen virulence factors. ETI is characterized by localized programmed cell death, effectively halting pathogen proliferation and leading to cultivar-specific resistance to disease (Fig. 5).

SbDREB2 (S1_76529338) candidate genes

Here, we identified a sorghum gene, SbDREB2 (S1_76529338), which is involved in the response of plants to abiotic stresses such as drought and high salinity (Fig. 6). It binds to DRE (dehydration-responsive element) in the promoter regions of stress-responsive genes (Table S4). This gene enhances a plant’s ability to withstand stressful conditions, making it essential for maintaining growth and yield under adverse environmental situations.

Fig. 6.

Overview of carbon metabolism pathways. The figure shows a detailed representation of the carbon metabolism pathways, illustrating the key processes and interactions involved in carbon fixation and utilization

The map in Fig. 6 provides an overview of central carbon metabolism, illustrating the number of carbon atoms in each compound, represented by circles. An asterisk denotes cofactors such as CoA, CoM, THF, or THMPT. The map highlights key carbon utilization pathways, including glycolysis (map00010), the pentose phosphate pathway (map00030), and the citrate cycle (map00020), as well as six recognized carbon fixation pathways (map00710 and map00720) and certain pathways related to methane metabolism (map00680) (Fig. 6). The six carbon fixation pathways are as follows: (1) the reductive pentose phosphate cycle (Calvin cycle) found in plants and cyanobacteria that carry out oxygenic photosynthesis; (2) the reductive citrate cycle in photosynthetic green sulfur bacteria and some chemolithoautotrophs; (3) the 3-hydroxy propionate bicycle in photosynthetic nonsulfur bacteria; (4) the hydroxypropionate‒hydroxybutyrate cycle; (5) the dicarboxylate-hydroxybutyrate cycle, both of which are variants of the 4-hydroxybutyrate pathways in Crenarchaeota; and (6) the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway in methanogenic bacteria [95, 96].

SbGA2ox (S1_67415907) candidate genes

The current study further identified a gene that encodes an enzyme that deactivates gibberellins, a group of plant hormones that promote growth (Fig. 7). The regulation of gibberellin levels plays a significant role in plant height and other growth processes. The regulation of gibberellin by SbGA2ox can affect various growth parameters, including stem elongation, which is crucial for optimizing plant architecture and improving yield (Table S4).

Fig. 7.

Plant hormone signaling pathways. This figure depicts a schematic representation of plant hormone signaling pathways, highlighting the molecular interactions and regulatory processes involved in plant growth and development. The diagram illustrates the interactions between SbAGL1 and key hormones such as auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, and abscisic acid, demonstrating how SbAGL1 integrates multiple signaling pathways

The SbAGL1 gene plays a crucial role in plant hormonal signaling and flowering regulation. It is situated within a network of hormonal signals that govern developmental processes, particularly flowering time and reproductive development. As a transcription factor, SbAGL1 influences the expression of downstream genes related to floral development and maturation, with the arrows in likely highlights feedback mechanisms that allow SbAGL1 activity to be modulated by environmental stimuli and internal hormonal levels, optimizing flowering timing for the plant’s growth conditions (Fig. 7).

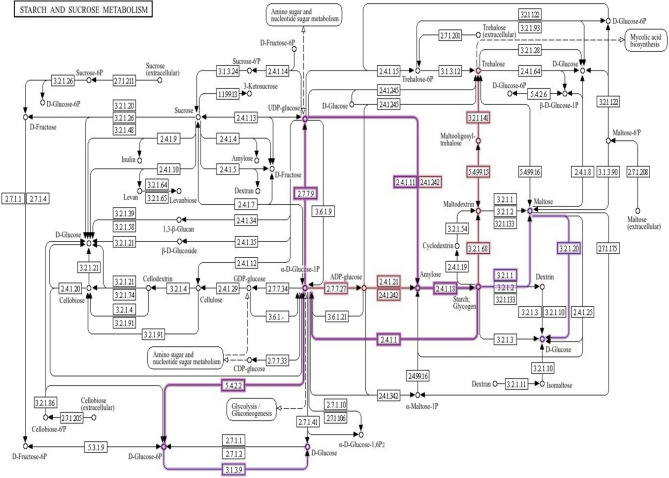

SbAGL1 (S10_60795709) candidate genes

Based on our identification, a sorghum gene SbAGL1 (S10_60795709), as part of the AGL family, regulates reproductive development, especially seed and fruit formation, involved in Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways (Fig. 8). SbAGL1 plays a critical role in seed-filling processes, which directly affect yield. It regulates the metabolic pathways necessary for the accumulation of starch and other carbohydrates in developing seeds (Table S4). It is associated with the conversion of glucose into starch and sucrose, involving key enzymatic reactions such as phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways. The figure shows a detailed overview of starch and sucrose metabolism pathways, illustrating the biochemical processes and enzyme interactions involved in carbohydrate metabolism and the biochemical pathways of starch and sucrose metabolism in sorghum. This diagram highlights regulatory points and interactions between pathways, highlighting the complexity of carbohydrate metabolism and its integration with overall plant physiology. Intermediates such as ADP-glucose and sucrose-6-phosphate are shown alongside their corresponding enzymes, labeled with their enzyme commission numbers. Color coding enhances clarity: black lines represent standard metabolic pathways, whereas purple lines indicate regulatory connections that influence these processes. The arrows illustrate the direction of metabolic flow, and the nodes mark branching points. The organized layout facilitates an understanding of the relationships among different metabolites, making it easier to track substrate transformations. This detailed diagram serves as a valuable resource for understanding the intricate network of starch and sucrose metabolism in sorghum, highlighting both its complexity and regulatory mechanisms

Gene ontology (GO) functional annotation

The candidate genes associated with the QTNs play vital roles in regulating flowering time, stress responses, plant height, and reproductive development. The involvement of these genes in crucial biological pathways underscores their potential utility in sorghum breeding programs aimed at improving yield and resilience to environmental stressors. The analysis of GO terms associated with the candidate genes helps to elucidate the biological roles of these genes in the context of agronomic traits (Table S4). The candidate genes associated with key biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components relevant to agronomic traits in sorghum are summarized in Table S4.

Metabolic pathway analysis

This study not only highlights candidate genes associated with agronomic and yield-associated traits in sorghum but also explores their roles in crucial metabolic pathways, including starch and sucrose metabolism, secondary metabolism, and hormonal signaling pathways (Fig. 6). Understanding the metabolic pathways associated with candidate genes is essential for elucidating their roles in sorghum physiology [97, 98]. Key pathways include starch and sucrose metabolism, which are critical for seed filling and overall yield [99]. Secondary metabolism pathways producing phenolic compounds and flavonoids contribute to disease resistance and stress tolerance [100, 101]. Hormonal signaling pathways and genes involved in abscisic acid signaling play crucial roles in drought response genes [102–105].

Starch and sucrose metabolism are vital for energy storage and mobilization in plants. Genes in these pathways regulate the conversion of carbohydrates, impacting growth and yield. Chromosome SBI-01 harbors the gene Sobic.001G196700 (Table 2), which is crucial for regulating flowering time and may also indirectly influence carbohydrate allocation during development. Additionally, Sobic.001G215700 (Table 2), a sucrose synthase gene identified in previous research, plays a significant role in sucrose metabolism [106]. Several genes are present in SBI-02, including Sobic.002G183400, which is associated with floral development and may affect sucrose availability for reproductive structures; Sobic.002G153000 (Table 2), a key gene in starch biosynthesis, has also been highlighted [107, 108].

Chromosome SBI-03 features Sobic.003G324400, which regulates plant height and may influence starch accumulation, alongside Sobic.003G156600, a starch branching enzyme vital for starch structure [109]. On SBI-04, Sobic.004G178300 influences seed weight but is not directly linked to starch metabolism; however, Sobic.004G159900, a sucrose phosphate synthase gene, plays a critical role in sucrose synthesis [58]. SBI-05 includes the Sobic.005G176100 gene, which is related to stress responses that can affect carbohydrate metabolism under stress conditions, whereas Sobic.005G168600 is involved in starch degradation [110, 111]. Chromosome SBI-06 contains genes relevant to starch and sucrose metabolism, such as Sobic.006G125600, which encodes a granule-bound starch synthase [58]. SBI-07 features Sobic.007G031000, which is linked to sucrose metabolism and energy allocation during growth [58]. On SBI-08, Sobic.008G042000 encodes a starch synthase that contributes to starch accumulation [58]. Chromosome SBI-09 includes Sobic.009G245000, which is associated with carbohydrate metabolism and influences plant growth and development [58, 112]. Finally chromosome SBI-10 contains Sobic.010G195300, which is involved in sucrose metabolism and affects the energy balance of plants [110, 111].

In general, this study did not incorporate Haploview analysis or apply marker-assisted selection (MAS/MAB) due to limited phenotypic field trials because of financial constraints. For improved efficiency in future research work, we recommend integrating genotype environment association analysis (GEAA) along with MAS or genomic selection (GS) to facilitate early, accurate identification of superior genotypes, thereby conserving both time and resources.

Conclusion

This study highlights the effectiveness of multi-locus GWAS methods in revealing the genetic basis of key traits in sorghum. By identifying and characterizing QTNs and associated candidate genes, this research provides insights into sorghum’s genetic architecture. These results emphasize the agronomic performance and genetic diversity of Ethiopian sorghum landraces and improved genotypes. The successful use of ML-GWAS models and the identification of high-quality SNP markers have deepened our understanding of critical traits, laying the groundwork for effective breeding programs that aim to increase sorghum productivity and resilience under varying environmental conditions. Data analysis, including L and ML-GWAS, offered insights into the genetic architecture of the studied traits. Employing multiple ML-GWAS methods and incorporating kinship and population structure minimized false positives and enhanced statistical power. The established LOD score threshold effectively identified significant QTNs, clarifying the genetic basis of agronomic traits. The identification of 117 genes associated with yield-related characteristics underscores the potential for these findings in breeding programs. The distribution of these genes across sorghum chromosomes illustrates the complexity of trait inheritance influenced by multiple genetic factors. This research enhances our understanding of quantitative traits in sorghum and sets the stage for future studies focused on improving productivity through targeted genetic enhancements. Understanding the roles of these genes in critical pathways such as starch and sucrose metabolism is vital for enhancing sorghum’s growth and yield. Starch and sucrose metabolism are crucial for energy storage and mobilization in plants, and genes involved in these pathways can significantly impact overall plant productivity.

Genes such as Sobic.001G196700, located on chromosome SBI-01, regulate flowering time and may influence carbohydrate allocation during development. Other genes, like Sobic.002G183400 and Sobic.003G324400, are associated with floral development and plant height, respectively, indicating their roles in determining yield potential. Overall, these findings reveal the intricate relationships between genetic diversity and agronomic traits in sorghum, providing a foundation for targeted breeding strategies. The functional characterization of candidate genes through Gene Ontology analysis highlights their roles in critical biological processes while exploring metabolic pathways and reveals connections between carbohydrate metabolism and traits such as flowering time and stress tolerance. This understanding supports the development of improved sorghum varieties that can thrive in diverse conditions, ultimately contributing to food security and agricultural sustainability.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Fig S1Genetic association (MTA), and GWAS analysis of agronomic and yield-related traits in sorghum.

Supplementary Material 2: Fig S2 Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Heatmap of SNPs on Chromosome 4 in Sorghum bicolor.

Supplementary Material 3: Table S1 Ethiopian Sorghum Landraces, Improved Varieties, and Improved-Landraces.

Supplementary Material 4: Table S2 Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for agronomic traits in 216 sorghum genotypes evaluated across three environments.

Supplementary Material 5: Table S3 Estimates of genetic parameters for six agronomic traits in sorghum genotypes.

Supplementary Material 6: Table S4Details of candidate genes implicated in key biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components related to agronomic traits in sorghum.

Acknowledgements

We thank Addis Ababa Science and Technology University for supporting this study. We also extend our gratitude to Dr Alemu Tirfesa and his sorghum research teams at MARC and to Dr Habte Nida at the Sorghum Research Division, Purdue University.

Authors’ contributions

AG collected the field agronomic and yield-related traits, prepared the dataset, conducted the data analysis, interpreted and visualized the results, prepared the draft manuscript and edited the final manuscript. HN provided the SNP markers dataset, reviewed the draft and final manuscript. AAW validated the data, supported with the data analysis, interpretation and visualization of the results and reviewed the draft and final manuscript, supervised and administrated the project. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding

No Funding.

Data availability

The SNP markers dataset was made available through the Purdue University Sorghum Research Repository https://purr.purdue.edu/publications/3189/1. And also can be seen from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31191590/ and https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33217211/. The supplementary dataset for our tested Ethiopian Sorghum Landraces, Improved Varieties, and Improved-Landraces is included in this submission.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ameen M, et al. Sorghum’s potential unleashed: A comprehensive exploration of bio-energy production strategies and innovations. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2024;27:101906. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paterson AH, et al. The sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457:551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyles RE, et al. Genetic and genomic resources of sorghum to connect genotype with phenotype in contrasting environments. Plant J. 2019;97:19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Wet JMJ. Domestication of African cereals. African Economic History. 1977;(3): 15-32.

- 5.Proietti I, et al. Exploiting nutritional value of staple foods in the world’s semi-arid areas: Risks, benefits, challenges and opportunities of sorghum. in Healthcare. 2015;3:172–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonapi VA, et al. Sorghum in the 21st century: food, fodder, feed, fuel for a rapidly changing world. Singapore: Springer;2020.

- 7.Cuevas HE, et al. Assessment of grain protein in tropical sorghum accessions from the NPGS germplasm collection. Agronomy. 2023;13:1330. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor JRN, Duodu KG. Traditional sorghum and millet food and beverage products and their technologies. In Sorghum and millets. Elsevier. 2019. (pp. 259–92). AACC International Press.

- 9.Chaturvedi P et al. Sorghum and Pearl millet as climate resilient crops for food and nutrition security. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022;13:851970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Prasad VBR, et al. Drought and high temperature stress in sorghum: physiological, genetic, and molecular insights and breeding approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadolska-Orczyk A, et al. Major genes determining yield-related traits in wheat and barley. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130:1081–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattivelli L, et al. Drought tolerance improvement in crop plants: an integrated view from breeding to genomics. F Crop Res. 2008;105:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsehaye Y et al. Multi-locus genome‐wide association study for grain yield and drought tolerance indices in sorghum accessions. Plant Genome. 2024;17(4):e20505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Bernardeli A, et al. Population genomics and molecular breeding of sorghum. In Population genomics: crop plants. Cham: Springer International Publishing;2022. pp. 289-340.

- 15.Lasky JR, et al. Genome-environment associations in sorghum landraces predict adaptive traits. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1400218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rama Reddy NR, et al. Detection and validation of stay-green QTL in post-rainy sorghum involving widely adapted cultivar, M35-1 and a popular stay-green genotype B35. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korte A, Farlow A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: a review. Plant Methods. 2013;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao J, et al. Genome-wide association study for nine plant architecture traits in sorghum. Plant Genome. 2016;9:plantgenome2015–06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S-B, et al. Improving power and accuracy of genome-wide association studies via a multi-locus mixed linear model methodology. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao K, et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat Commun. 2011;2:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, et al. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet. 2006;38:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang HM, et al. Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2010;42:348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang SB, et al. Improving power and accuracy of genome-wide association studies via a multi-locus mixed linear model methodology. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamba CL, Zhang Y-M. A fast mrMLM algorithm for multi-locus genome-wide association studies. biorxiv. 2018. 10.11010/341784.

- 25.Zhang Y-W, et al. MrMLM v4. 0.2: an R platform for multi-locus genome-wide association studies. Genomics Proteom Bioinforma. 2020;18:481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen Y, et al. The improved FASTmrEMMA and GCIM algorithms for genome-wide association and linkage studies in large mapping populations. Crop J. 2020;8:723–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamba CL, et al. Iterative sure independence screening EM-Bayesian LASSO algorithm for multi-locus genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, et al. pLARmEB: integration of least angle regression with empirical Bayes for multilocus genome-wide association studies. Heredity (Edinb). 2017;118:517–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren W-L, et al. pKWmEB: integration of Kruskal–Wallis test with empirical Bayes under polygenic background control for multi-locus genome-wide association study. Heredity (Edinb). 2018;120:208–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, et al. Multi-locus genome-wide association study reveals the genetic architecture of stalk lodging resistance-related traits in maize. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu S, et al. Genome-wide association studies of ionomic and agronomic traits in USDA mini core collection of rice and comparative analyses of different mapping methods. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu X, et al. Multi-locus genome-wide association studies for 14 main agronomic traits in barley. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desta BT et al. Effects of Seed Rate and Nitrogen Fertilizer Levels on grain quality and fertilizer Utilization Efficiency of Durum Wheat. In Proc. Crop. Improv. Manag. Res. Results 2020/21. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2023. pp. 171-187.

- 34.Dudley R. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normalityMIT Mathematics. 2023.

- 35.Jones B, Sall J. JMP statistical discovery software. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2011;3:188–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmour AR, et al. ASReml update. What’s new in release 3.00. VSN Int. Hemel Hempstead, UK. 2009.

- 37.Popat R et al. Package variability: Genetic Variability Analysis for Plant Breeding Research version 0.1.0. 2020.

- 38.Pariyar SR et al. Variation in root system architecture among the founder parents of two 8-way magic wheat populations for selection in breeding. Agronomy. 2021;11(12):2452.

- 39.Alvarado G, et al. META-R: A software to analyze data from multi-environment plant breeding trials. Crop J. 2020;8:745–56. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blangero J, et al. Robust LOD scores for variance component-based linkage analysis. Genet Epidemiol Off Publ Int Genet Epidemiol Soc. 2000;19:S8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elshire RJ, et al. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradbury PJ, et al. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2633–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glaubitz JC, et al. TASSEL-GBS: a high capacity genotyping by sequencing analysis pipeline. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das S, et al. DiscoverSL: an R package for multi-omic data driven prediction of synthetic lethality in cancers. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:701–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Remington DL, et al. Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiede T, et al. Predicting genetic variance in bi-parental breeding populations is more accurate when explicitly modeling the segregation of informative genomewide markers. Mol Breed. 2015;35:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wartha CA, Lorenz AJ. Genomic predictions of genetic variances and correlations among traits for breeding crosses in soybean. Heredity (Edinb). 2024;133:173–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mace E, et al. The sorghum QTL atlas: a powerful tool for trait dissection, comparative genomics and crop improvement. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:751–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smedley D, et al. BioMart - Biological queries made easy. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolser D, et al. Ensembl plants: integrating tools for visualizing, mining, and analyzing plant genomics data. In Plant Bioinformatics: Methods and Protocols. New york, NY: Springer New York. 2016. pp. 115-140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Binns D, et al. QuickGO: a web-based tool for gene ontology searching. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3045–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gladman N et al. SorghumBase: A Web-based Portal for Sorghum Genetic Information and Community Advancement. 2022;255. 10.1007/s00425-022-03821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Goodstein D et al. Phytozome comparative plant genomics portal. 2014.

- 54.Wang Y, et al. Genomic analyses provide comprehensive insights into the domestication of Bast fiber crop Ramie (Boehmeria nivea). Plant J. 2021;107:787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu R, et al. The 6xABRE synthetic promoter enables the Spatiotemporal analysis of ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1650–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodstein DM, et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1178–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voorrips R. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered. 2002;93:77–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, et al. The identification of a yield-related gene controlling multiple traits using GWAS in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L). Plants. 2023;12:1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith A, et al. The effects of heat stress on male reproduction and tillering in sorghum bicolor. Food Energy Secur. 2023;12:e510. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slatkin M. Linkage disequilibrium—understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:477–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Visscher PM, et al. 10 years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Getahun A, et al. Multi-locus genome-wide association mapping for major agronomic and yield-related traits in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench) landraces. BMC Genomics. 2025;26:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berisa T, Pickrell JK. Approximately independent linkage disequilibrium blocks in human populations. Bioinformatics. 2015;32:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ron M, Weller JI. From QTL to QTN identification in livestock–winning by points rather than knock-out: a review. Anim Genet. 2007;38:429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clemis VMM. Mapping and functional characterization of powdery mildew resistance genes in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). 2022.

- 67.Wondimu Z, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genomic loci influencing agronomic traits in Ethiopian sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) landraces. Mol Breed. 2023;43:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei X, et al. A quantitative genomics map of rice provides genetic insights and guides breeding. Nat Genet. 2021;53:243–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.JIANG B, et al. Advances in studies on identification methods and molecular biology of drought resistance in sorghum. Biotechnol Bull. 2021;37:260. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alam MM, et al. QTL analysis in multiple sorghum populations facilitates the dissection of the genetic and physiological control of tillering. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:2253–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu Q, et al. Quantitative trait locus mapping for important yield traits of a sorghum-sudangrass hybrid using a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism map. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1098605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar M, et al. GWAS and genomic prediction for pre-harvest sprouting tolerance involving sprouting score and two other related traits in spring wheat. Mol Breed. 2023;43:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sachdeva S, et al. New insights into QTNs and potential candidate genes governing rice yield via a multi-model genome-wide association study. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elias M et al. Multi-locus genome‐wide association study reveal genomic regions underlying root system architecture traits in Ethiopian sorghum germplasm. Plant Genome. 2024;17(2):e20436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Shi X, et al. Identification of QTNs and their candidate genes for boll number and boll weight in upland cotton. Genes (Basel). 2024;15:1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rockman MV. The QTN program and the alleles that matter for evolution: all that’s gold does not glitter. Evol (N Y). 2012;66:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choudhary M et al. QTLomics-based Genetic Dissection of Key Traits in Major Cereals: Challenges and Prospects. Omics and system biology approaches for delivering better cereals. 2024:71-110.

- 78.Li J, et al. Genome-wide association studies for five forage quality-related traits in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L). Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang L, et al. Identification of candidate forage yield genes in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) using integrated genome-wide association studies and RNA-seq. Front Plant Sci. 2022;12:788433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee YW, et al. Identifying the genes underlying quantitative traits: a rationale for the QTN programme. AoB Plants. 2014;6:plu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gupta PK, et al. Association mapping in crop plants: opportunities and challenges. Adv Genet. 2014;85:109–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wayne ML, McIntyre LM. Combining mapping and arraying: an approach to candidate gene identification. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:14903–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harris-Shultz KR, et al. Mapping QTLs and identification of genes associated with drought resistance in sorghum. Sorghum: Methods and Protocols. 2019:11-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Woldesemayat AA, et al. Cross-species multiple environmental stress responses: an integrated approach to identify candidate genes for multiple stress tolerance in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) and related model species. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0192678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo Y, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals key genes contributing to the differences in drought tolerance among three cultivars of Foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Plant Growth Regul. 2023;99:45–64. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mirdar Mansuri R, et al. Salt tolerance involved candidate genes in rice: an integrative meta-analysis approach. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Woldesemayat AA, et al. An integrated and comparative approach towards identification, characterization and functional annotation of candidate genes for drought tolerance in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). BMC Genet. 2017;18:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Galla G, et al. Computational annotation of genes differentially expressed along Olive fruit development. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salem MSZ. Biological networks: an introductory review. J Proteom Genomics Res. 2018;2:41–111. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Du L, et al. Transcriptome Analysis and QTL Mapping Identify Candidate Genes and Regulatory Mechanisms Related to Low-Temperature Germination Ability in Maize. Genes (Basel). 2023;14:1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuczyńska M, et al. More than just antioxidants: Redox-active components and mechanisms shaping redox signalling network. Antioxidants. 2022;11:2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sperschneider J, et al. LOCALIZER: subcellular localization prediction of both plant and effector proteins in the plant cell. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Greco R, et al. MADS box genes expressed in developing inflorescences of rice and sorghum. Mol Gen Genet MGG. 1997;253:615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roslan ND, et al. Flavonoid biosynthesis genes putatively identified in the aromatic plant polygonum minus via expressed sequences Tag (EST) analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:2692–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Canfield DE, et al. Carbon fixation and phototrophy. Advances in marine biology Elsevier. 2005;48:95–127. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ward LM, Shih PM. The evolution and productivity of carbon fixation pathways in response to changes in oxygen concentration over geological time. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;140:188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gelli M, et al. Validation of QTL mapping and transcriptome profiling for identification of candidate genes associated with nitrogen stress tolerance in sorghum. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]