Abstract

Background

Epinephelus corallicola, also known as the coral grouper, is an economically valuable grouper species widely distributed in Southeast Asia. However, its genomic information and phylogenetic status remain unclear. Furthermore, despite substantial genomic resources accumulated for Eupercaria, integrated analyses of phylogenetic relationships and genome evolution based on these resources remain scarce.

Results

In this study, we generated high-quality haplotype-solved genomes of E. corallicola, with total lengths of 1.086 Gb and 1.083 Gb for the two haplotypes, and contig N50 values of 44.94 Mb and 43.86 Mb, respectively. Phylogenomic analyses placed the Perciformes at the basal position of the Eupercaria, with an estimated divergence time of 88.55 Mya. And the phylogenetic topology supported the previous proposal to elevate Epinephelinae to the family level as Epinephelidae, distinct from Serranidae. Ancestral karyotype evolution analyses based on chromosomal genomes of 33 species revealed that E. corallicola serves as a representative model for the 24 ancestral linkage groups (ALGs) of Eupercaria, enabling the tracing of ancient chromosomal evolution across lineages. Within the Epinephelidae, the whole-genome average nucleotide identity (ANI) among species ranged from 84.16% to 96.97%. Gene family expansion and contraction analyses revealed 285 significantly expanded and 618 contracted gene families. Notably, the expanded gene families were significantly enriched in immune-related genes, including MHCIIα, MHCIIβ, and RFX5, which may contribute to the adaptive evolution of E. corallicola.

Conclusions

Our results provide important genomic resources for Epinephelidae, advancing aquaculture and selective breeding programs for groupers, while offering new insights into the phylogeny and ancestral chromosomal karyotype evolution of Eupercaria.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11996-x.

Keywords: Epinephelus corallicola, Eupercaria, Phylogeny, Ancestral karyotype evolution

Introduction

Grouper (Epinephelidae, Perciformes, Eupercaria) represents a highly diverse and ecologically significant fish group comprising over 160 species across 16 genera [1]. These species are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical marine waters [2], predominantly inhabiting rocky and coral reef systems where they serve as apex predators. Most groupers exhibit protogynous hermaphroditism, a sexual dimorphism pattern where individuals mature first as females before undergoing sex change to males [3]. Due to their favorable taste and high nutritional value, groupers are among the most commercially valuable species in Asian countries, for instance, China, Japan and Indonesia. Just in China, the fishing production of groupers was 113,218 tons in 2023 (China Fishery Statistical Yearbook 2024). The high demand for groupers has made them one of the most intensively fished species in certain regions [4]. Despite reductions in fishing effort enforced through management actions, several grouper species have been overfished (FAO 2024) and whose populations are declining and facing extinction (IUCN). Developing large-scale sustainable grouper farming can not only alleviate the pressures of biodiversity conservation but also generate significant economic value [5].

Nowadays, the grouper aquaculture industry is expanding rapidly, with main species such as the kelp grouper (Epinephelus moara) [6], brown-marbled grouper (E. fuscoguttatus), giant grouper (E. lanceolatus) [5]. Hybrid breeding has been widely adopted to enhance production yields, exemplified by the highly successful crossbreeding of E. fuscoguttatus ♀ × E. lanceolatus ♂ [7]. However, grouper hybrid breeding still lacks theoretical guidance, leading to a degree of randomness in hybrid combination selection. Additionally, diversifying cultured species is critical for the sustainable development of grouper aquaculture. E. corallicola, the coral grouper, is an economically valuable species, but it primarily relies on wild capture. Due to its high market value, this species may have the potential to become an important cultured species or a parent for hybrid groupers. However, its phylogenetic classification information and genomic data remain scarce.

Genomic resources are not only vital for revealing adaptive evolution [8] and phylogenetic relationships [9], but also form the cornerstone of molecular breeding [10, 11]. Although substantial genomic data have accumulated for Eupercaria, integrated analyses of phylogenetic relationships and genome evolution based on these resources remain scarce. These available resources present an opportunity to investigate both the phylogenetic position of Epinephelidae within Perciformes and evolutionary dynamics across the orders of Eupercaria. Here, we generated haplotype-resolved reference genomes for E. corallicola and integrated multi-species genomic resources for phylogenomic inference and karyotype evolution analyses. Our results not only provide important genomic resources for Epinephelidae, but also offer new insights into the genomic evolution of Eupercaria.

Methods

Sampling and sequencing

An adult individual of E. corallicola (provided Sanya Agricultural Investment Marine Industry Co., Ltd.) was euthanized using 250 mg/L of tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, Sigma, USA). The tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C for preservation. The total DNA was extracted from muscle using the MagAttract® HMW DNA Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and integrity of the total DNA were assessed using a Qubit 3.0 and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. The 15 kb SMRTbell library was constructed with Sequel Sequencing Kit 3.0 (PacBio, USA) and sequenced on the PacBio Revio platform. The Hi-C library of muscle was constructed following the standard protocol with 4-cutter restriction enzyme MboI and sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform.

Total RNA was isolated from 9 tissues (including brain, gonad, gill, gut, heart, kidney, liver, skin, and spleen) using TRIzol method. The quantity and integrity (RIN > 7.0) of total RNA were assessed using NanoDrop and Agilent 2100, respectively. The mRNAs with polyA tails were enriched using Oligo (dT) Magnetic beads and subsequently reverse-transcribed into double-stranded cDNA. The paired-end 150 bp mRNA sequencing libraries were constructed using VAHTS Universal V10 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and sequenced on DNBSEQ-T7 platform.

Genome assembly

Fastp v0.23.2 was used to perform quality filtering on raw reads of Hi-C data with parameter ‘-l 80’ [12]. The hifiasm v0.20.0-r639 was used to assemble the haplotype-resolved assemblies using HiFi reads and clean reads of Hi-C data with parameter ‘-s 0.50 -D 6 -N 105’ [13]. The redundant haplotigs and overlaps of each assembly were removed using purge_dups v1.2.5 [14]. To anchor the contigs to chromosomes, clean reads of Hi-C data were Mapped onto each assembly according to the Juicer pipeline, with MboI as the enzyme site. Chromosome scaffolding was carried out using 3D-DNA v180114 with the parameter ‘-r 0’, and the Juicebox v1.11.08 was used to manually review and corrected the assembly errors [15]. To improve genome continuity, TGS GapCloser v1.2.1 (https://github.com/BGI-Qingdao/TGS-GapCloser) was used for gap closing with parameters ‘–min_idy 0.05’ using PacBio HiFi reads. The program TeloExplorer of quarTeT was used for telomere identification within the genome assemblies [16]. The quality values (QV) of the genome assemblies were assessed using Merqury v1.3.

Genome annotation

RepeatModeler v2.0.5 was used to construct a de novo transposable element library for E. corallicola [17]. Additionally, LTRfinder v1.0.7 [18] and LTR_retriever v3.0.1 [19] were employed to build the LTR retrotransposon library. CD-HIT v4.8.1 was then used to remove redundancy from the combined libraries. Subsequently, the non-redundant library was utilized for repeat annotation and soft-masking of the genome using RepeatMasker v4.1.7.

The gene annotation process was performed using the BRAKER v3.0.8 pipeline [20] with repeat-masked genome assembly, employing an integrated multi-evidence strategy that incorporates: homology-based prediction, transcriptome-guided prediction and ab initio gene prediction [21]. The clean reads of RNA-Seq data were mapping to the reference genome with HISAT2 v2.2.1 with default parameters, and the sorted BAM files generated by SAMtools v1.9 [22] were used as transcriptomic evidence. The homologous protein datasets were derived from annotation files of Danio rerio (GCF_000002035.6), Epinephelus lanceolatus (GCF_005281545.1) and Centropristis striata (GCF_030273125.1). The de novo assembly of RNA-Seq data was conducted using Trinity v2.14.0, and the resulting assembly was used to update the gene features with PASApipeline v2.5.3. The assembly and annotation completeness were measured by Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v5.8.2 against actinopterygii_odb10 (2024–01-08). The mitogenome of E. corallicola was assembled using MitoHiFi [23], and the annotation of the mitogenome was performed with MitoFinder and MITOS2 [24, 25]. Functional annotation for the predicted protein-coding genes was conducted using EggNOG Mapper with EggNOG database [26].

Phylogenetic analyses

The phylogenetic analyses included order-level taxonomic groups within Eupercaria and the family-level taxonomic groups within Perciformes that have annotated genome data available in NCBI (Table S1). Additionally, Lateolabrax maculatus and E. lanceolatus underwent re-annotation due to inconsistencies between their original annotations (deposited on FigShare) and the current genome assembly versions.

Single-copy orthologous genes were identified with OrthoFinder v2.5.2 [27]. Sequences of each ortholog were aligned using MAFFT with the parameters ‘–maxiterate 1000 –globalpair’ [28]. Poorly aligned regions were removed using Gblocks v0.91b with parameters ‘-t = p -b5 = n’. FASconCAT-G v1.05 was used to concatenate the processed sequence alignments into a super-matrix and generated the partition region. Then, the best-fit substitution models were selected via ModelTest-NG v0.1.7 under the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with the -T raxml parameter enabled [29]. The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny was reconstructed using RAxML-NG v1.1.0 with 1000 bootstrap replicates for branch support estimation [30]. Anabantiformes (Anabantaria) + Pleuronectiformes (Carangaria) were designated as the outgroup [31–33]. The divergence time estimation was inferred using the program MCMCtree of PAML v4.9 J [34]. The Markov chain was run for 200 million generations, with sampling every 500 generations and a burn-in of the initial 25% of the samples. The MCMC results were checked using Tracer v.1.7.2 with ESS over 200.

The phylogenetic tree was calibrated using five nodes: (1) The root node divergence between Pleuronectiformes (outgroups) and Perciformes was constrained to have occurred 100–130 Mya, with a 95% confidence interval, based on molecular clock analyses from TimeTree (https://timetree.org/) [35]. (2) The crown group of Perciformes according to the fossil records was estimated to emerge between 61.6–72 Mya [36, 37], with a 95% soft boundary set for this time range [32]. (3) The Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA) of Channa argus & Anabas testudineus was constrained with a minimum age constraint of 41.3 Mya and a 95% soft upper boundary at 82.2 Mya [38], according to †Eochanna chorlakkiensis GSP-UM 781 [39]. (4) The MRCA of the clade comprising Pleuronectidae and Paralichthyidae was constrained with a minimum age of 29.62 Mya and a 95% soft upper boundary at 35.3 Mya, based on †Oligopleuronectes germanicus from the Frauenweiler fossil site, Germany [32, 40]. (5) The MRCA of Gasterosteus aculeatus & Pungitius pungitius was constrained with a minimum age of 13.1 Mya and a 95% soft upper boundary at 39.39 Mya, based on the †Gasterosteus cf. wheatlandi, LACM 150177 (https://fishtreeoflife.org/fossils/).

Genome evolution analyses

The longest protein isoforms from genome annotations were utilized for the identification of orthologues between species. Reciprocal BLAST was performed using the NCBI BLASTP v2.15 tool, and top hits were retained using an e-value cutoff of < 1e-10. The genome of E. corallicola (hap1) was used to represent the ancestral linkage groups (ALGs) of Eupercaria. The Karyotype Evolution Comparative Analysis was visualized with RIdeogram and the scripts from https://bitbucket.org/viemet/public/src/master/CLG/scripts. To avoid inconsistencies in genomic chromosome nomenclature, the chromosomes of all genomes were renamed based on their length in the analyses. Links between chromosomes with fewer than eight shared orthologs are trimmed from ribbon plots for clarity; all genes are shown in bar plots [41].

The whole-genome average nucleotide identity (ANI) of genome between species was analyzed with FastANI v1.34 [42]. Gene family expansion and contraction were analyzed using CAFE5 based on the results from OrthoFinder and Phylogenetic analyses [43]. Functional enrichment analysis was performed on expanded gene families. KEGG and GO enrichment analysis was conducted using clusterProfiler [44]

Results and discussion

Genome assembly

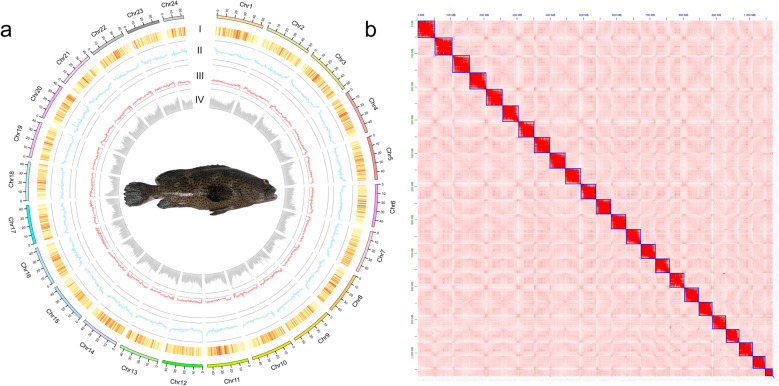

A total of 98.46 Gb (approximately 90.8 × coverage) of PacBio HiFi reads (N50 = 16,155 bp) and 158.24 Gb (approximately 145.8 × coverage) of Hi-C data were generated. Using these data, we produced two haplotype-resolved genome assemblies for E. corallicola, with total lengths of 1.086 Gb and 1.083 Gb, and contig N50 values of 44.94 Mb and 43.86 Mb (Table 1), respectively. Through Hi-C scaffolding, 85 contigs of hap1 and 82 contigs of hap2 were all anchored into 24 pseudochromosomes for both assemblies, with anchoring rates of 98.51% and 99.09% for the respective haplotypes (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). The scaffold N50 values of the assemblies were 45.24 Mb and 46.20 Mb for hap1 and hap2, respectively, with 19 and 21 telomeres detected in each (Table S2). The telomere sequence motif of E. corallicola was 'TTAGGG', which is consistent with that of the congeneric species E. lanceolatus, as well as the closely related species Cephalopholis sonnerati [45, 46]. And the Chr12 of hap1 was assembled as a telomere-to-telomere sequence without gaps. Both genome assemblies recovered 99.3% of the orthologs of actinopterygii_odb10 (hap1: Single-copy (S) 98.85%, Duplicated (D) 0.44%; hap2: S = 98.87%, D = 0.41%), with around 0.6% fragmented (F) and around 0.1% missing (M). These scores align with the T2T genomes of two groupers (E. lanceolatus and C. sonnerati), both at 99.3% (Table S3) [45, 46]. In addition, we Mapped the HiFi reads on the assemblies including the mitogenome, both of the assemblies achieved an alignment rate of 99.98%. The quality values (QV) of the genome assemblies were 68.92 for Hap1 and 69.54 for Hap2, which are higher than those of E. lanceolatus (59.24) and C. sonnerati (51.80). These results indicate a high degree of continuity and completeness in the genome assembly of E. corallicola.

Table 1.

Statistics for genome assemblies and annotations of E. corallicola

| Type | Hap1 | Hap2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly statistics | Assembled genome size (Gb) | 1.086 | 1.083 |

| Number of scaffolds | 79 | 67 | |

| Scaffold N50 (Mb) | 45.24 | 46.20 | |

| Number of contigs | 85 | 82 | |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 44.94 | 43.86 | |

| Number of chromosomes | 24 | 24 | |

| Anchoring rate | 98.51 | 99.09 | |

| BUSCO completeness (%) | 99.29 | 99.29 | |

| Single copy | 98.85 | 98.87 | |

| Duplicated | 0.44 | 0.41 | |

| Fragmented | 0.60 | 0.58 | |

| Missing | 0.11 | 0.14 | |

| Annotation statistics | Number of genes | 24,229 | 24,091 |

| BUSCO completeness (%) | 98.08 | 97.83 | |

| Single copy | 96.73 | 96.51 | |

| Duplicated | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

| Fragmented | 0.80 | 0.91 | |

| Missing | 1.13 | 1.26 |

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal features of the E. corallicola genome hap1. a Distribution of genomic features. I: Density of genes; II: GC content; III: Density of DNA elements; IV: Density of TE elements. b Hi-C interaction heatmap of 24 chromosomes of hap1 assembly, ordered numerically (Chr1-Chr24)

Gene annotation

The total lengths of the transposable elements (TE) sequences in hap1 and hap2 was 451.39 Mb and 451.83 Mb, accounting for 41.55% and 41.70% of the total assembly length, respectively (Table S4). Within these TE sequences, DNA transposons constituted the highest proportion of the genome, at 15.30% and 15.34%, respectively, followed by unclassified TEs, which Make up 12.97% and 13.01% of the genome, respectively. The length of all types of TEs in hap1 and hap2 was highly similar.

Integrated annotation strategies (de novo, transcriptome-guided, and homology-based) predicted 24,229 and 24,091 protein-coding genes in hap1 and hap2, respectively (Table 1). BUSCO assessment revealed high completeness for both assemblies: hap1 achieved 98.08% coverage (S: 96.73%; D: 1.35%; F: 0.80%; M: 1.13%), while hap2 showed comparable results with 97.83% (S: 96.51%; D: 1.32%; F: 0.91%; M: 1.26%). These scores closely matched the BUSCO of the genome assemblies. Gene functional annotation of hap1 revealed 22,792 functionally annotated genes, including 16,253 with GO terms, 16,186 with KEGG terms, and 21,979 with Pfam terms; while hap2 revealed 22,724 functionally annotated genes, including 16,250 with GO terms, 16,139 with KEGG terms, and 21,924 with Pfam terms.

Phylogenetic analysis

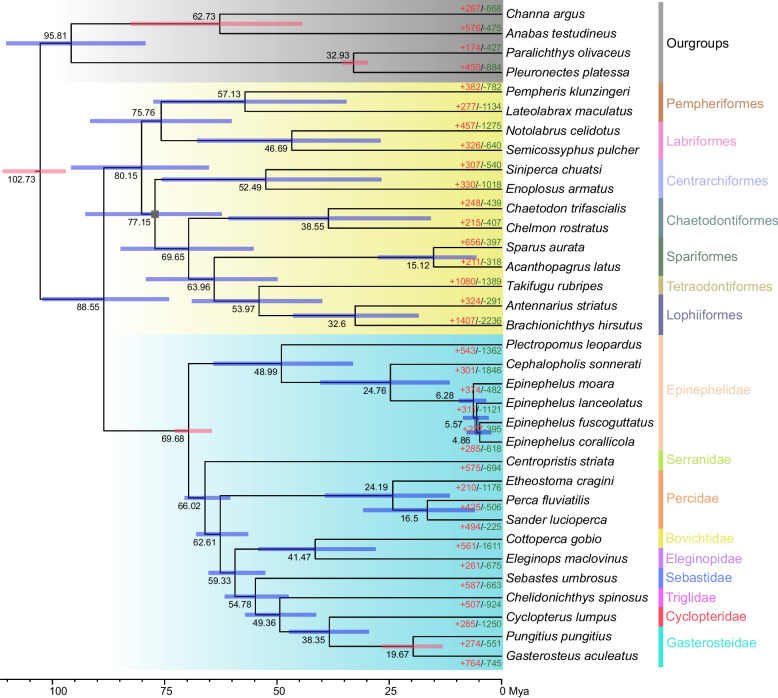

We identified a total of 5,100 single-copy orthologous genes across the studied species. After removing non-conserved regions using Gblocks and filtering out shorter sequences, 5,068 single-copy orthologous genes (comprising 2,242,862 amino acids) were retained for phylogenetic tree reconstruction. The best-fit substitution model was determined to be JTT + I + G4. All the nodes of the phylogenetic tree showed 100% bootstrap support, except for the position of Centrarchiformes (Fig. 2). The Order Perciformes was positioned at the base of Eupercaria, with the divergence time between Perciformes and other clades estimated at 88.55 Mya. This estimate exhibited strong consistency with recent phylogenetic analyses of six independent UCE loci datasets, which yielded divergence time estimates ranging from 86.27 to 93.73 Ma [32]. The Pempheriformes and Labriformes formed a clade (A), while another clade (B) was composed of Chaetodontiformes in a nested relationship with Spariformes and the combined grouping of Tetraodontiformes and Lophiiformes. The position of Centrarchiformes was not confidently resolved (91% bootstrap), however, its closer relationship to Clade B is consistent with a previous study [33].

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree and divergence time estimates of Eupercaria. Blue shaded area: Order Perciformes; Yellow shaded area: Other order of Eupercaria; Red bar: Calibration node (divergence times based on fossil/molecular clock data). Gray box: Node support value of 91%. Red/green text: Number of expanded/contracted gene families

Within the Order Perciformes, the family Epinephelidae also occupied a basal position. Epinephelidae have long been classified as Epinephelinae under the family Serranidae [5]. However, accumulating research indicates that Epinephelinae does not belong to Serranidae, and the Epinephelinae was proposed to be elevated to the family level as Epinephelidae [47]. This classification is strongly supported by the phylogenetic trees reconstructed in our study based on whole-genome datasets. The internal topology of Epinephelidae revealed a clade structured as Plectropomus + (Cephalopholis + Epinephelus), with divergence times estimated as follows: Plectropomus split from the Cephalopholis + Epinephelus Lineage at 48.99 Mya, Cephalopholis and Epinephelus diverged at 24.76 Mya. Within the genus Epinephelus, E. corallicola formed a sister relationship with E. fuscoguttatus, which subsequently clustered with E. lanceolatus. Our topology within Epinephelus was inconsistent with previous phylogenetic results based on mitochondrial data, which suggested the relationship ((E. fuscoguttatus + E. lanceolatus) + E. moara) + E. corallicola [48]. The mitochondrial-based phylogeny exhibited lower nodal support at critical nodes, in sharp contrast to the robustness observed in our analysis. The results highlight the importance of employing genomic datasets in phylogenetic reconstruction studies.

Ancestral karyotype evolution

The ancestral karyotype evolutionary analysis encompassed 29 species of Eupercaria and 4 outgroup species. Among these, 24 species of Perciformes and 2 outgroup species exhibited conserved chromosomal karyotypes compared to E. corallicola, indicating that E. corallicola may represent the ALGs of Eupercaria (Fig. S2 and S3). The ALGs of Eupercaria comprised 24 chromosomal linkage groups (Fig. 3a). End-to-end fusions were only observed in Gasterosteidae (Perciformes) and Takifugu rubripes (Tetraodontiformes). In Cyclopterus lumpus (Cyclopteridae, Perciformes), chromosomal fusion involving segments from ALG9 and ALG11 was identified, resulting in a new chromosome that increased the total chromosome count compared to ALGs.

Fig. 3.

Genome evolution. a Ancestral karyotype evolution of Eupercaria; b ANI of six species of Epinephelidae; c KEGG enrichment of expanded gene families of E. corallicola

The chromosomal segment translocation from ALG14 to ALG24 was shared by both species (Chelmon rostratus and Sparus aurata) within the Order Spariformes (Fig. 3a and Fig. S2-S3). Moreover, the chromosomal segment translocations from ALG1 to ALG10 and from ALG11 to ALG17 were both shared by species (Antennarius striatus and Brachionichthys hirsutus) within the Order Lophiiformes. In Lophiiformes, the genes involved in the segment translocation include N-MYC and TGFB2, which are associated with the Cell Cycle pathway. N-MYC plays a critical role in vertebrate organogenesis during embryonic and early larval development [49, 50]. Moreover, N-MYC has been implicated as a major causative factor in Feingold syndrome and megalencephaly-polydactyly syndrome, which are typically associated with digital anomalies (e.g., syndactyly), craniofacial bone anomalies, and visceral developmental abnormalities [51]. The chromosomal segment translocation may contribute to the morphological variations of Lophiiformes species [52]. Sander lucioperca (Percidae, Perciformes) exhibited abundant segment translocations. It should be noted that abundant segment translocations of this species may require further validation to avoid genome assembly artifacts.

Comparative genomic analyses

The whole-genome ANI between species serves as an important indicator for assessing genetic divergence between species [53]. Among groupers, the ANI values between P. leopardus and the Cephalopholis + Epinephelus clade ranged from 84.16% to 84.55%, while ANI values between C. sonnerati and Epinephelus spp. fell between 89.15% and 89.44% (Fig. 3b). Within the Epinephelus genus, pairwise ANI values among the four species clustered tightly within a narrow range of 96.32% to 96.97%. Notably, the ANI values between Epinephelus species did not strictly align with their phylogenetic divergence order, which may be due to the relatively close divergence times among these species and/or differences in mutation rates among species [54].

Gene family expansion and contraction are critical mechanisms for species adaptation to environmental challenges. In E. corallicola, we identified 285 significantly expanded gene families and 618 contracted gene families (Fig. 2). Functional enrichment analysis of expanded gene families revealed that these genes were significantly enriched in GO terms related to positive regulation of cytokine production and positive regulation of lymphocyte migration biological processes (Fig. S4). KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that the expanded gene families were significantly enriched in Intestinal immune network for IgA production, Lectin and Antigen processing and presentation pathways (Fig. 3c). The results indicated that the significantly expanded genes were predominantly associated with immune-related functions. The expansion of genes within the intestinal immune network for IgA production pathway may enable this species to produce abundant non-inflammatory IgA antibodies, thereby regulating host-microbe interactions to facilitate adaptation to highly diverse coral reef habitats [55]. Interestingly, we also found that MHCIIα, MHCIIβ, and RFX5 (a key transcriptional regulator of MHCII gene expression in the immune system) were all significantly expanded [56]. Given the pivotal role of MHCII in exogenous antigen presentation, the expansion of these gene families may enhance resistance to bacterial and parasitic infections [57], which could make E. corallicola a promising candidate for grouper aquaculture species or hybrid parent with high disease resistance.

Conclusion

In this study, we generated high-quality haplotype-solved genomes of E. corallicola. Phylogenomic analyses placed the Perciformes at the basal position of the Eupercaria, with an estimated divergence time of 88.55 Mya. And the phylogenetic topology supported the previous proposal to elevate Epinephelinae to the family level as Epinephelidae, distinct from Serranidae. Based on chromosomal genomes of 33 species, we revealed that E. corallicola serves as a representative model for the 24 ALGs of Eupercaria, enabling the tracing of ancient chromosomal evolution across Lineages. Within the Epinephelidae, the ANI among species ranged from 84.16% to 96.97%. Gene family expansion and contraction analyses highlighted significant expansions in immune-related genes, including MHCIIα, MHCIIβ, and RFX5, which may contribute to adaptive evolution of E. corallicola. Our results not only provide important genomic resources for Epinephelidae but also offer new insights into the genomic evolution of Eupercaria.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the High-Performance Biological Supercomputing Center at Ocean University of China for this research.

Abbreviations

- ALGs

Ancestral linkage groups ALGs

- ANI

Average nucleotide identity ANI

- MRCA

Most recent common ancestor

Authors’ contributions

B.Z., H.J., and W.B. conceived and designed the experiments. J.C. and H.C. collected the samples. H.C., L.M., T.H. and Z.D. collected the data. Z.B., J.Y., Y.Y., L.M., T.H. and Z.D performed data analysis. Z.B., J.C., J.Y., Y.Y. and H.C. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key R&D Project of Hainan Province (ZDYF2025SXLH003) and the Project of Sanya Yazhouwan Science and Technology City Management Foundation (SKJC-2023–01-004).

Data availability

The raw data and the genome assemblies of *E. corallicola* have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). BioSample: SAMN47759687, BioProject: PRJNA1245589, PRJNA1245630 and PRJNA1245631. The mitogenome accessions number: PV555488. The annotation files, as well as the reannotation files, are available on FigShare (https://figshare.com/projects/Genome_assembly_of_Epinephelus_corallicola/243638).

Declarations

Ethics and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China (Project Identification Code: 20240810A1). The animal sources were obtained with permission from Sanya Agricultural Investment Marine Industry Co., Ltd., located in Sanya, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Baojun Zhao and Chaofan Jin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bo Wang, Email: wb@ouc.edu.cn.

Jingjie Hu, Email: hujingjie@ouc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ma KY, Craig MT, Choat JH, van Herwerden L. The historical biogeography of groupers: clade diversification patterns and processes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;100:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tapilatu RF, Tururaja TS. Sipriyadi, Kusuma AB: Molecular Phylogeny Reconstruction of Grouper (Serranidae: Epinephelinae) at Northern Part of Bird’s Head Seascape - Papua Inferred from COI Gene. Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2021;24(5):181–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandari RK, Komuro H, Nakamura S, Higa M, Nakamura M. Gonadal restructuring and correlative steroid hormone profiles during natural sex change in protogynous honeycomb grouper (Epinephelus merra). Zoolog Sci. 2003;20(11):1399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das SK, Xiang TW, Noor NM, De M, Mazumder SK, Goutham-Bharathi MP. Temperature physiology in grouper (Epinephelinae: Serranidae) aquaculture: a brief review. Aquac Rep. 2021. 10.1016/j.aqrep.2021.100682. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimmer MA, Glamuzina B. A review of grouper (family Serranidae: subfamily Epinephelinae) aquaculture from a sustainability science perspective. Rev Aquac. 2017;11(1):58–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Q, Gao H, Xu H, Lin H, Chen S. A chromosomal-scale reference genome of the kelp grouper Epinephelus moara. Mar Biotechnol. 2020;23(1):12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nankervis L, Cobcroft JM, Nguyen NV, Rimmer MA. Advances in practical feed formulation and adoption for hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus♂) aquaculture. Rev Aquacult. 2021;14(1):288–307. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia T, Gao X, Zhang L, Zhou S, Zhang Z, Ding J, Sun G, Yang X, Zhang H. Chromosome-level genome provides insights into evolution and diving adaptability in the vulnerable common pochard (Aythya ferina). BMC Genomics. 2024. 10.1186/s12864-024-10846-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Baeza JA, Chen C, Gonzalez MT, González VL, Greve C, Kocot KM, Arbizu PM, Moles J, Schell T, et al. A genome-based phylogeny for Mollusca is concordant with fossils and morphology. Science. 2025;387(6737):1001–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng Q, Zhao B, Wang H, Wang M, Teng M, Hu J, Bao Z, Wang Y. Aquaculture molecular breeding platform (AMBP): a comprehensive web server for genotype imputation and genetic analysis in aquaculture. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W66-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen LK, Thompson NF, Abernathy JW, Ahmed RO, Ali A, Al-Tobasei R, Beck BH, Calla B, Delomas TA, Dunham RA, et al. Advancing genetic improvement in the omics era: status and priorities for United States aquaculture. BMC Genomics. 2025;26(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):i884–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H, Jarvis ED, Fedrigo O, Koepfli K-P, Urban L, Gemmell NJ, Li H. Haplotype-resolved assembly of diploid genomes without parental data. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(9):1332–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan D, McCarthy SA, Wood J, Howe K, Wang Y, Durbin R, Valencia A. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(9):2896–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durand NC, Shamim MS, Machol I, Rao SSP, Huntley MH, Lander ES, Aiden EL. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3(1):95–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y, Ye C, Li X, Chen Q, Wu Y, Zhang F, Pan R, Zhang S, Chen S, Wang X, et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Hortic Res. 2023. 10.1093/hr/uhad127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C, Smit AF. Repeatmodeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Z, Wang H. Ltr_finder: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W265-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou S, Jiang N. Ltr_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(2):1410–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabriel L, Brůna T, Hoff KJ, Ebel M, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M, Stanke M. BRAKER3: fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Res. 2024;34(5):769–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I, Hayes A, Waack S, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W435-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience. 2021. 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uliano-Silva M, Ferreira JGRN, Krasheninnikova K, Blaxter M, Mieszkowska N, Hall N, Holland P, Durbin R, Richards T, Kersey P, et al. Mitohifi: a python pipeline for mitochondrial genome assembly from PacBio high fidelity reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2023. 10.1186/s12859-023-05385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allio R, Schomaker-Bastos A, Romiguier J, Prosdocimi F, Nabholz B, Delsuc F. Mitofinder: efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2020;20(4):892–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernt M, Donath A, Juhling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, Putz J, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69(2):313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Heller D, Hernandez-Plaza A, Forslund SK, Cook H, Mende DR, Letunic I, Rattei T, Jensen LJ, et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D309–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emms DM, Kelly S. Orthofinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, Flouri T. Modeltest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37(1):291–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(21):4453–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanciangco MD, Carpenter KE, Betancur-R R. Phylogenetic placement of enigmatic percomorph families (Teleostei: Percomorphaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;94:565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghezelayagh A, Harrington RC, Burress ED, Campbell MA, Buckner JC, Chakrabarty P, Glass JR, McCraney WT, Unmack PJ, Thacker CE, et al. Prolonged morphological expansion of spiny-rayed fishes following the end-Cretaceous. Nat Ecol Evol. 2022;6(8):1211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes LC, Ortí G, Huang Y, Sun Y, Baldwin CC, Thompson AW, Arcila D, Betancur-R R, Li C, Becker L, et al. Comprehensive phylogeny of ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) based on transcriptomic and genomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(24):6249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13(5):555–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Suleski M, Craig JM, Kasprowicz AE, Sanderford M, Li M, Stecher G, Hedges SB. TimeTree 5: an expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol Biol Evol. 2022. 10.1093/molbev/msac174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarzhans WW, Carnevale G, Stringer GL. The diversity of teleost fishes during the terminal Cretaceous and the consequences of the K/Pg boundary extinction event. Neth J Geosci. 2024. 10.1017/njg.2024.1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarzhans WW, Jagt JWM. Silicified otoliths from the Maastrichtian type area (Netherlands, Belgium) document early gadiform and perciform fishes during the Late Cretaceous, prior to the K/Pg boundary extinction event. Cretaceous Res. 2021;127(104921):1–26. 10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104921.

- 38.Hughes LC, Nash CM, White WT, Westneat MW, Matschiner M. Concordance and discordance in the phylogenomics of the wrasses and parrotfishes (Teleostei: Labridae). Syst Biol. 2023;72(3):530–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roe L. Phylogenetic and ecological significance of Channidae (Osteichthyes Teleostei) from the early Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat, Pakistan. Contrib Mus Paleontol Univ Mich. 1991;28(5):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrington RC, Faircloth BC, Eytan RI, Smith WL, Near TJ, Alfaro ME, Friedman M. Phylogenomic analysis of carangimorph fishes reveals flatfish asymmetry arose in a blink of the evolutionary eye. BMC Evol Biol. 2016. 10.1186/s12862-016-0786-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewin TD, Liao IJ-Y, Luo Y-J, Corbett-Detig R. Annelid comparative genomics and the evolution of massive lineage-specific genome rearrangement in bilaterians. Mol Biol Evol. 2024;41(9):msae172. 10.1093/molbev/msae172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018. 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(10):1269–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z, Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu S, Liu Y, Li M, Ge Q, Wang C, Song Y, Zhou B, Chen S. Gap-free telomere-to-telomere haplotype assembly of the tomato hind (Cephalopholis sonnerati). Sci Data. 2024. 10.1038/s41597-024-04093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Q, Liu X, Song Y, Li M, Fan G, Chen S. Telomere-to-telomere gapless genome assembly of the giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus). Sci Data. 2024. 10.1038/s41597-024-04219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith WL, Craig MT, Quattro JM. Casting the percomorph net widely: the importance of broad taxonomic sampling in the search for the placement of serranid and percid fishes. Copeia. 2007;2007(1):35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang C, Ye P, Liu M, Zhang Y, Feng H, Liu J, Zhou H, Wang J, Chen X. Comparative analysis of four complete mitochondrial genomes of Epinephelidae (Perciformes). Genes. 2022. 10.3390/genes13040660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loeb-Hennard C, Kremmer E, Bally-Cuif L. Prominent transcription of zebrafish N-myc (nmyc1) in tectal and retinal growth zones during embryonic and early larval development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5(3):341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koo B-K, Li Y-F, Cheng T, Zhang Y-J, Fu X-X, Mo J, Zhao G-Q, Xue M-G, Zhuo D-H, Xing Y-Y. et al. Mycn regulates intestinal development through ribosomal biogenesis in a zebrafish model of Feingold syndrome 1. PLOS Biology. 2022;20(11):e3001856. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Nishio Y, Kato K, Oishi H, Takahashi Y, Saitoh S. MYCN in human development and diseases. Front Oncol. 2024. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1417607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickson BV, Pierce SE. How (and why) fins turn into limbs: insights from anglerfish. Earth Environ Sci Trans R Soc Edinb. 2018;109(1–2):87–103. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortimiglia C, Alonso-Del-Real J, Belloso Daza MV, Querol A, Iacono G, Cocconcelli PS. Evaluating the genome-based average nucleotide identity calculation for identification of twelve yeast species. J Fungi. 2024. 10.3390/jof10090646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergeron LA, Besenbacher S, Zheng J, Li P, Bertelsen MF, Quintard B, Hoffman JI, Li Z, St. Leger J, Shao C, et al. Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates. Nature. 2023;615(7951):285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutzeit C, Magri G, Cerutti A. Intestinal IgA production and its role in host-microbe interaction. Immunol Rev. 2014;260(1):76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reith W, Mach B. The bare lymphocyte syndrome and the regulation of MHC expression. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19(1):331–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eizaguirre C, Lenz TL, Kalbe M, Milinski M. Rapid and adaptive evolution of MHC genes under parasite selection in experimental vertebrate populations. Nat Commun. 2012. 10.1038/ncomms1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data and the genome assemblies of *E. corallicola* have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). BioSample: SAMN47759687, BioProject: PRJNA1245589, PRJNA1245630 and PRJNA1245631. The mitogenome accessions number: PV555488. The annotation files, as well as the reannotation files, are available on FigShare (https://figshare.com/projects/Genome_assembly_of_Epinephelus_corallicola/243638).