Abstract

Background

Mental fatigue (MF) is a psychobiological state that impairs physical and cognitive performance, particularly in endurance and resistance tasks. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has emerged as a promising noninvasive neuromodulation technique to mitigate MF and increase exercise capacity. However, evidence remains inconsistent due to methodological heterogeneity in stimulation parameters, fatigue induction protocols, and outcome assessments. This research aims to systematically review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effects of active versus sham tDCS on reducing MF and improving physical performance, such as time to exhaustion and muscular endurance, in healthy, physically active adults, including athletes.

Methods

This protocol follows the PRISMA-P guidelines and is registered with PROSPERO (CRD4202541050229). Eligible studies will include RCTs (parallel or crossover) comparing active tDCS (any validated protocol) with sham stimulation in adults ≥ 18 years of age without neurological, psychiatric, or cardiovascular conditions. Searches will be conducted in PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Primary outcomes are time to exhaustion and number of repetitions to failure; secondary outcomes include MF scores. Two independent reviewers will select studies, extract data, and assess risk of bias using Cochrane RoB 2.0. Metaanalyses will be performed where possible, with subgroup, sensitivity, and metaregression analyses as appropriate.

Discussion

This review will synthesize the available evidence on the efficacy of tDCS on MF and physical performance in healthy adults. The results aim to inform the design of future research and support the standardization of tDCS protocols in sport and exercise science.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD420251050229

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13643-025-02916-x.

Background

Sports performance has been extensively investigated through experimental clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews to enhance physical and cognitive capabilities and improve outcomes in competitive settings [1–3]. Among the various factors that influence athletic performance, mental fatigue (MF) stands out. MF is a transient state of reduced cognitive and executive functioning resulting from prolonged and intense mental effort [4, 5]. This condition manifests through subjective symptoms of tiredness, decreased motivation, and difficulty concentrating, assessed by self-report instruments, such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) for mental fatigue, and by performance changes in attention and information-processing tasks [4–6]. MF is associated with increased ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), decreased time to exhaustion in endurance tasks, and reduced total work volume in muscular resistance tasks, typically measured by fewer repetitions until failure [5, 7–9].

Multiple factors may trigger MF, such as high work demands, information overload, prolonged concentration, physical exercise, and repetitive tasks, all of which lead to sensations of tiredness, decreased motivation, and heightened distractibility—ultimately impairing executive control and decision-making [10–12]. In the sports domain, the impact of MF varies depending on task intensity: it tends to be more pronounced in endurance activity at low- and moderate-intensity and less evident in short duration at high intensity [13–16].

Given the cognitive and motor impairments induced by MF, there is increasing interest in techniques capable of modulating brain activity, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) [3, 17, 18]. tDCS delivers low-intensity electrical currents through scalp-mounted electrodes, promoting membrane depolarization with anodal stimulation and hyperpolarization with cathodal stimulation [17–20]. Anodal stimulation protocols targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the primary motor cortex (M1) have shown reductions in RPE and improvements in endurance and muscular performance by extending time to failure [21–23].

However, the literature presents mixed results. For instance, Holgado et al. [24] found no significant performance enhancement in trained cyclists receiving tDCS over the DLPFC, while Penna et al. [25] reported no ergogenic effect in master swimmers. These findings suggest that variables such as stimulation site, current intensity, and participant characteristics may influence the technique’s efficacy [24, 25]

Despite promising findings, such as increased training volume [23] and prolonged time to exhaustion [21], the heterogeneity of tDCS protocols complicates cross-study comparisons and evidence consolidation [3]. This variability includes key parameters such as current intensity [18], stimulation duration [17, 26], electrode montage and placement [3, 27], and outcome selection [17]. Similarly, other investigations have failed to demonstrate consistent benefits of tDCS in endurance tasks or resistance-based protocols [24, 25, 28, 29]. These findings suggest that stimulation site, current density, individual training level, and prior exposure to tDCS may modulate its efficacy.

The diversity of tDCS protocols (intensity, duration, and montage) and mental fatigue induction methods, along with inconsistent results, precludes the definition of optimal parameters for reliable modulation. Although previous reviews have assessed the effects of tDCS on physical performance or examined factors related to MF separately, no systematic review has concurrently evaluated tDCS, MF, and physical performance in healthy adults, including athletes. In light of these considerations, this protocol aims to systematically review randomized controlled trials comparing active versus sham tDCS in reducing MF and improving time to exhaustion and repetitions to failure in healthy adults.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This protocol was developed according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [30] and registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251050229).

Eligibility criteria

Only randomized controlled trials (parallel or cross-over designs) comparing active tDCS, conducted according to validated protocols targeting any brain region, with sham stimulation, will be included. Participants must be physically active adults (recreational or athletes), aged ≥ 18 years, with no neurological, psychiatric, or cardiovascular conditions that could interfere with performance. Studies must report time to exhaustion during endurance tests and number of repetitions to failure in muscular resistance tests as primary outcomes, as well as secondary outcomes related to mental fatigue (MF), assessed by validated scales (e.g., VAS). Only studies published in English will be considered, as the language restriction aims to ensure high quality in data extraction and interpretation, minimizing translation bias [31]. Although all researchers involved in data extraction are Brazilian, they are proficient in reading and writing in English, ensuring the reliability of the process. No date restrictions will be applied. Exclusion criteria will encompass non-randomized studies, studies with clinical populations, interventions without active tDCS or standardized MF induction protocols, investigations that do not report MF and physical performance outcomes, and duplicates or publications with incomplete protocols. The eligibility criteria are detailed below using the PICOS framework:

Population (P): Physically active adults (recreational or athletes), aged ≥ 18 years, with no neurological, psychiatric, or cardiovascular conditions

Intervention (I): Active tDCS, applied according to validated protocols targeting any brain region

Comparator (C): Sham tDCS, with electrodes placed but no current delivered, according to the protocol by Gandiga et al. [32]

Outcomes (O): Primary — increased time to exhaustion (endurance) and greater number of muscular strength repetitions to failure

Secondary: Reduction in mental fatigue (VAS score or equivalent scale)

Study design (S): Randomized controlled trials (parallel or crossover)

Information sources

The literature search will be conducted exclusively in peer-reviewed journals indexed in the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov. All databases will be searched from inception to the date of the final search (anticipated for November 2025). The date of each search, the specific search strategy, and the number of retrieved records will be meticulously documented in a structured Excel spreadsheet.

Search strategies

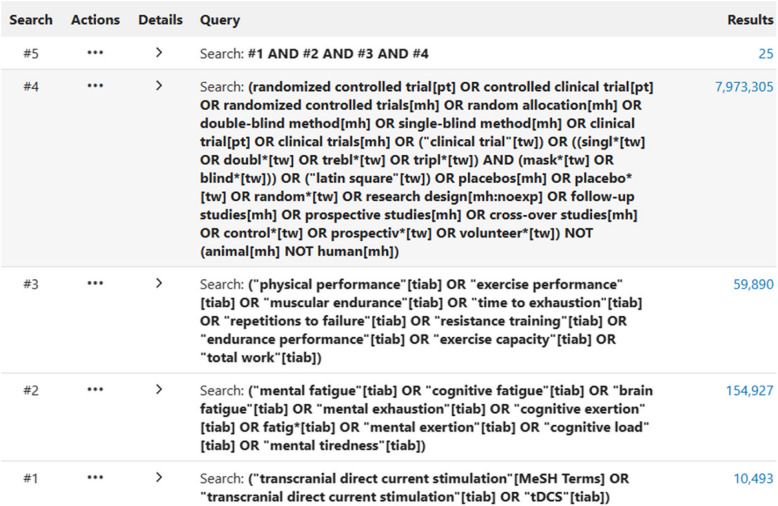

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed using four conceptual blocks: (1) transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), (2) mental fatigue and cognitive exertion, (3) physical performance outcomes, and (4) a validated filter for randomized controlled trials. The full strategy is detailed below. The final PubMed search was executed on June 11, 2025, yielding 25 records. Equivalent adaptations will be implemented in Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The full PubMed strategy is available in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Full PubMed search strategy

The full search strategy for all databases is available in S1 File.

Study selection

All records will be imported into Rayyan software (Rayyan Systems Inc., USA) [33], where duplicates will be automatically removed. Two independent reviewers will screen titles and abstracts. Studies marked as “include” or “uncertain” will advance to full-text evaluation, also conducted independently. Disagreements will be resolved through consensus or, if needed, by a third reviewer. The final manuscript will illustrate the selection process using the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [34].

Data extraction

Two reviewers will independently extract data regarding study identification (author, year, country, clinical trial registration), population characteristics (age, sex, physical activity level), MF induction protocol, tDCS parameters (intensity, duration, montage, polarity), sham details, physical performance outcomes (time to exhaustion and repetitions to failure), and MF scores, as well as statistical estimates (means, standard deviations, effect sizes, confidence intervals, p-values). Discrepancies will be discussed and, if necessary, resolved by a third reviewer. All decisions will be documented in a structured Excel spreadsheet.

Data items

A structured spreadsheet will be developed for data extraction, containing predefined fields for all relevant study characteristics and outcomes. Two independent reviewers will extract the data in duplicate, and discrepancies will be resolved through discussion or, if necessary, adjudicated by a third reviewer. The following information will be collected: study design (parallel/crossover), sample size (total and by group), randomization and blinding methods, type of cognitive task used to induce MF, MF measurement tools, technical parameters of tDCS, characteristics of the sham protocol, and all predefined primary and secondary outcomes. When data are not available in the text or tables, authors will be contacted. If necessary, numeric data will be extracted from figures using WebPlotDigitizer, a validated graphical extraction tool. For transparency, the data extraction file will document all extracted values, software version, and parameters (e.g., axis calibration, resolution settings).

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk of bias will be assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool (Sterne et al.) [35] at the level of each primary outcome (time to exhaustion and repetitions to failure) and the secondary outcome (MF). Two independent reviewers will judge five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting. A pilot assessment of 5 to 10 studies will be conducted to calibrate the criteria. Disagreements will be resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer. Results will be summarized in tables.

Data synthesis

When at least three homogeneous studies are available for an outcome, a meta-analysis using a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) will be performed. Mean differences will be calculated for time to exhaustion and standardized effect sizes for repetitions to failure. Heterogeneity will be assessed using Cochran’s Q and the I2 statistic. If heterogeneity is high (I2 > 75%) or the number of studies is insufficient, a narrative synthesis will be adopted, grouping findings according to MF protocol characteristics, tDCS parameters, and participants’ activity levels. Pre-specified subgroup analyses (athletes vs. nonathletes; anodal vs. cathodal stimulation) and sensitivity analyses (excluding studies with high risk of bias) will be conducted. An exploratory meta-regression will be performed if ≥ 10 comparable studies are available.

Certainty of evidence

The strength of the body of evidence for the primary outcomes will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. This evaluation will consider five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Two reviewers will independently apply the GRADE criteria, and disagreements will be resolved by consensus or adjudicated by a third reviewer. A summary of findings (SoF) table will be developed to present each primary outcome’s GRADE ratings and key outcome data.

Discussion

This protocol establishes a rigorous and transparent methodology for conducting a systematic review of tDCS in physically active adults, emphasizing enhancing physical performance and reducing mental fatigue. By prioritizing primary outcomes, precisely time to exhaustion and the number of repetitions to failure, and restricting inclusion to randomized controlled trials, we aim to maximize comparability between studies and the validity of the findings. The resulting synthesis is expected to support the standardization of tDCS protocols in sports and exercise settings.

However, certain limitations inherent to the study design must be acknowledged. The decision to include only studies published in English may exclude relevant evidence available in other languages, and the variability in tDCS technical parameters (such as intensity, duration, and electrode montage), as well as in mental fatigue induction protocols, may introduce heterogeneity that limits the feasibility of conducting meta-analyses. To mitigate these issues, we will implement sensitivity analyses, subgroup analyses, and exploratory meta-regression, in addition to carefully assessing the risk of bias and the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach. The findings of this review may provide a foundation for developing standardized, evidence-based tDCS protocols to enhance physical performance and mitigate mental fatigue in athletic populations. This could directly support coaches, clinicians, and sports scientists in implementing safe and effective brain stimulation strategies to optimize performance in training and competition environments. Ethical approval from a Research Ethics Committee is not required as this literature review is based on previously published studies. In this way, we aim to address the identified methodological gap and foster collaboration and transparency in future research on tDCS, mental fatigue, and physical performance.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: S1 File. Full Search Strategy for All Databases.

Supplementary Material 2: S2 File. PRISMA-P Checklist.

Supplementary Material 3: S3 File. Data Extraction Form.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Faculty of Physical Education and Dance (FEFD) of the Federal University of Goiás and IF Goiano for their support.

Abbreviations

- DLPFC

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- MF

Mental fatigue

- M1

Primary motor cortex

- PRISMA-P

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RoB 2.0

Risk of bias 2.0 tool

- RPE

Rating of perceived exertion

- tDCS

Transcranial direct current stimulation

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. Therefore, all authors conceptualized the project, drafted the protocol, registered it, contributed to its development, and critically read and gave final comments.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brasil (CAPES) — Finance Code 001.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during this study will constitute the resulting systematic review article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not required for a systematic review of publicly available literature.

Consent for publication

This study uses secondary (published) data; as such, consent will not be required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Matias Noll, Email: matias.noll@ifgoiano.edu.br.

Gustavo De Conti Teixeira Costa, Email: conti02@ufg.br.

References

- 1.Jaberzadeh S, Zoghi M. Transcranial direct current stimulation enhances exercise performance: a mini review of the underlying mechanisms. Front Neuroergon. 2022;3. 10.3389/fnrgo.2022.841911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lattari E, Andrade ML, Filho AS, et al. Can transcranial direct current stimulation improve muscle power in individuals with advanced weight-training experience? J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(12):3381–7. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado S, Jansen P, Almeida V, Veldema J. Is tDCS an adjunct ergogenic resource for improving muscular strength and endurance performance? A systematic review Front Psychol. 2019;10:1127. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boksem MAS, Tops M. Mental fatigue: costs and benefits. Brain Res Rev. 2008;59(1):125–39. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcora SM, Staiano W, Manning V. Mental fatigue impairs physical performance in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:857–64. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91324.2008.-Mental. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badin OO, Smith MR, Conte D, Coutts AJ. Mental fatigue: Impairment of technical performance in small-sided soccer games. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(8):1100–5. 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lima-Junior D, Fortes LS, Ferreira MEC, et al. Effects of smartphone use before resistance exercise on inhibitory control, heart rate variability, and countermovement jump. Applied Neuropsychology:Adult. 2021;31(1):48–55. 10.1080/23279095.2021.1990927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MR, Coutts AJ, Merlini M, Deprez D, Lenoir M, Marcora SM. Mental fatigue impairs soccer-specific physical and technical performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(2):267–76. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Queiros VS de, Dantas M, Fortes L de S, et al. Mental fatigue reduces training volume in resistance exercise: a cross-over and randomized study. Percept Mot Skills. 2021;128(1):409–423. 10.1177/0031512520958935 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Barker LM, Nussbaum MA. Fatigue, performance and the work environment: a survey of registered nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(6):1370–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Linden D, Massar SAA, Schellekens AFA, Ellenbroek BA, Verkes RJ. Disrupted sensorimotor gating due to mental fatigue: preliminary evidence. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;62(1):168–74. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boksem MAS, Meijman TF, Lorist MM. Effects of mental fatigue on attention: an ERP study. Cogn Brain Res. 2005;25(1):107–16. 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alix-Fages C, Cano H, Baz-Valle E, Balsalobre-Fernández C. Effects of mental fatigue induced by stroop task and by social media use on resistance training performance, movement velocity, perceived exertion, and repetitions in reserve: a randomized and double-blind crossover trial. Motor Control. 2023;27(3):645-649 10.1123/mc.2022-0129 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Alix-Fages C, Baz-Valle E, González-Cano H, Jiménez-Martínez P, Balsalobre-Fernández C. Mental fatigue from smartphone use or stroop task does not affect bench press force–velocity profile, one-repetition maximum, or vertical jump performance. Mot Control. 2023;27(3):631–44. 10.1123/mc.2022-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortes LS, de Lima-Júnior D, Fonseca FS, Albuquerque MR, Ferreira MEC. Effect of mental fatigue on mean propulsive velocity, countermovement jump, and 100-m and 200-m dash performance in male college sprinters. Applied Neuropsychology:Adult. 2024;31(3):264–73. 10.1080/23279095.2021.2020791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staiano W, Bonet LRS, Romagnoli M, Ring C. Mental fatigue: the cost of cognitive loading on weight lifting, resistance training, and cycling performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2023;18(5):465–73. 10.1123/ijspp.2022-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angius L, Hopker J, Mauger AR. The ergogenic effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on exercise performance. Front Physiol. 2017;8:90. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stagg CJ, Nitsche MA. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(1):37–53. 10.1177/1073858410386614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colzato LS, Nitsche MA, Kibele A. Noninvasive brain stimulation and neural entrainment enhance athletic performance—a review. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement. 2017;1(1):73–9. 10.1007/s41465-016-0003-2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527(3):633–9. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angius L, Santarnecchi E, Pascual-Leone A, Marcora SM. Transcranial direct current stimulation over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex improves inhibitory control and endurance performance in healthy individuals. Neuroscience. 2019;419:34–45. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieira LAF, Lattari E, de Jesus Abreu MA, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) improves back-squat performance in intermediate resistance-training men. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2020;93(1):210–8. 10.1080/02701367.2020.1815638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattari E, Rosa Filho BJ, Fonseca Junior SJ, et al. Effects on volume load and ratings of perceived exertion in individuals’ advanced weight training after transcranial direct current stimulation. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(1):89–96. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holgado D, Zandonai T, Ciria LF, Zabala M, Hopker J, Sanabria D. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the left prefrontal cortex does not affect time-trial self-paced cycling performance: evidence from oscillatory brain activity and power output. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):1–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penna EM, Filho E, Campos BT, et al. No effects of mental fatigue and cerebral stimulation on physical performance of master swimmers. Front Psychol. 2021;12:101554. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.656499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etemadi M, Amiri E, Tadibi V, Grospretre S, Valipour Dehnou V, Machado DG da S. Anodal tDCS over the left DLPFC but not M1 increases muscle activity and improves psychophysiological responses, cognitive function, and endurance performance in normobaric hypoxia: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurosci. 2023;24(1):25. 10.1186/s12868-023-00794-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Nasseri P, Nitsche MA, Ekhtiari H. A framework for categorizing electrode montages in transcranial direct current stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:54. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okano AH, Fontes EB, Montenegro RA, et al. Brain stimulation modulates the autonomic nervous system, rating of perceived exertion and performance during maximal exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(18):1213–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrne R, Flood A. The influence of transcranial direct current stimulation on pain affect and endurance exercise. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;45. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101554. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jüni P, Holenstein F, Sterne JAC, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):115–23. 10.1093/ije/31.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gandiga PC, Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS): a tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(4):845–50. 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. The BMJ. 2019;366:14898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: S1 File. Full Search Strategy for All Databases.

Supplementary Material 2: S2 File. PRISMA-P Checklist.

Supplementary Material 3: S3 File. Data Extraction Form.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study will constitute the resulting systematic review article.