Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the relationship between clinical and morphological parameters and gingival phenotype and to compare gingival phenotype across arch location.

Methods

Clinical measurements of gingival thickness (GT) keratinized gingival width (KGW) and papilla height (PH) were obtained of 50 individuals. In addition, dental stone models were measured for crown width (CW), crown length (CL) and gingival angle (GA). Data were analyzed using parametric and nonparametric tests, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Univariate analysis indicated that women were 4.1 times more likely to have thinner GT than men, whereas multivariate analysis found the likelihood to be 6.7 times higher. GT was thicker in the maxillary right posterior region than in other regions. A moderate positive correlation was found between GT and GA, and a weak positive correlation was found between GT and KGW. A weak negative correlation was found between GT and CL, with GT tending to decrease with increases in CL. No statistically significant correlation was found between GT and CW/CL. ROC analysis identified significant cut-off values for determining the gingival phenotype.

Conclusions

The current study found GT to vary with gender and dental-arch location. Furthermore, different crown morphologies were found to be associated with different periodontal soft-tissue characteristics.

Clinical Trial Registration: This study was registered in the Protocol Registration and Results System at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov with the registration number NCT06369493 on 2024-04-01.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06821-6.

Keywords: Gingiva, Gingival thickness, Gingival phenotype

Background

‘Biotype’, ‘morphotype’ and ‘phenotype’ are all terms that have been used to describe characteristics of periodontal tissue that exhibit individual-specific morphological changes [1], with the term ‘phenotype’ rather than ‘biotype’ suggested as preferable by the 2017 World Workshop on The Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions. Given the substantial influence that variations in osseous and gingival architecture have on the result of restorative therapy, identifying gingival phenotype can be of crucial significance in clinical practice [2]. Gingival phenotype not only influences the outcomes of restorative and periodontal therapies, root coverage procedures and the overall aesthetics of dentition, it also affects how periodontal tissues respond to physical, chemical, and bacterial insults [3]. For these reasons, understanding the prevalence of gingival phenotype in the general population as well as the relationship between gingival phenotype and other known clinical parameters is critical.

One commonly used metric for classifying gingival phenotype is ‘gingival thickness’ (GT). The World Workshop on Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions [1] has agreed on GT values of ≤ 1 mm and > 1 mm for classifying ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ phenotypes, in line with the recommendation of Kan et al. [4] The relationship between gingival phenotype and tooth shape and size has been studied both epidemiologically and therapeutically, with morphologic parameters including crown width (CW)/crown length (CL) [5, 6], keratinized gingival width (KGW) [7, 8], papilla height (PH) [3, 9, 10], bone thickness (BT) [11] and tooth position linked to GT. Several studies have also examined relationships between GT and gingival phenotype as well as age, gender and racial characteristics [6, 12–14]. However, the majority of studies examining gingival phenotype and related clinical parameters have been conducted in the maxillary anterior area, with only limited data available for the premolar and molar regions, where gingival recession and tooth loss are common. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the relationship and interaction between clinical and morphological parameters associated with gingival phenotype. The secondary objectives were to investigate the differences in gingival phenotype according to arch location, the effects of age and gender on gingival phenotype, and the cut-off values used in determining gingival phenotype.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study evaluated a total of in 50 patients (21 females, 29 males) applying to the Ondokuz Mayis University’s Periodontology Department for periodontal treatment between September 2022 and May 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and with the approval of the Ondokuz Mayis University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (OMUKAEK-Protocol No:2022/210). This study adhered to CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Participants were consecutively selected from patients who met the inclusion criteria. Using a previous study [14], stratifying participants according to thin and thick gingival phenotype according to GT measured at the maxillary right central incisor, it was found that statistical power was 80%, type 1 error rate was 0.05, and the minimum sample size was at least 42 people. To reduce the risk of possible data loss, 50 participants were initially included in the study and the final analysis was completed with 50 participants.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) non-smokers ≥ 18 years old, (b) gingival health on an intact periodontium according to the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions [1], (c) no history of systemic disease or consistent medication use, (d) no evidence of dental caries, crown shape alterations, or restorations affecting the occlusal edge in teeth, d) presence of complete permanent dentition from central incisors to first molars. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) pregnant or lactating women, previous or current orthodontic treatment or use of removable dentures or orthodontic devices, (b) a history of periodontitis or periodontal surgery involving teeth, (c) presence of abrasion or erosion in teeth, (d) gingival recession, (e) history of trauma affecting the position of the teeth,

Clinical measurements

All measurements were performed by a single experienced periodontist (SYB). Gingival health in the intact periodontium was determined by measuring the Loe & Silness plaque index [15], Silness & Loe gingival index [16], bleeding on probing index [17], and probing pocket depth in six regions of each tooth in the mouth. Participants who did not meet the gingival health criteria for an intact periodontium were excluded.

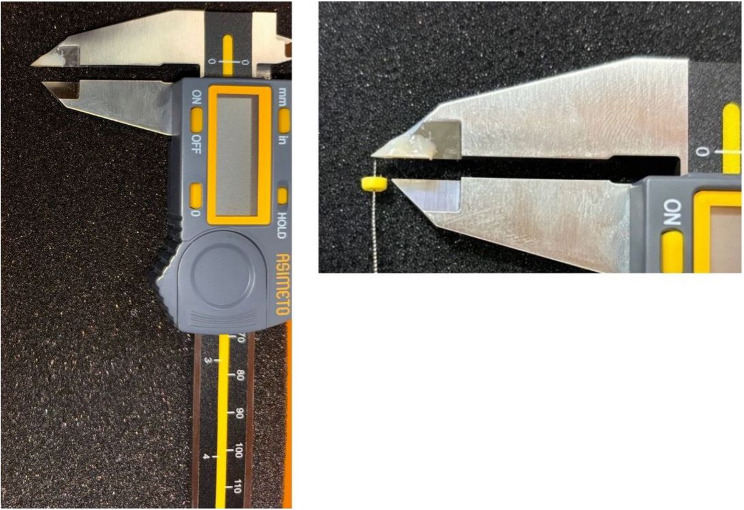

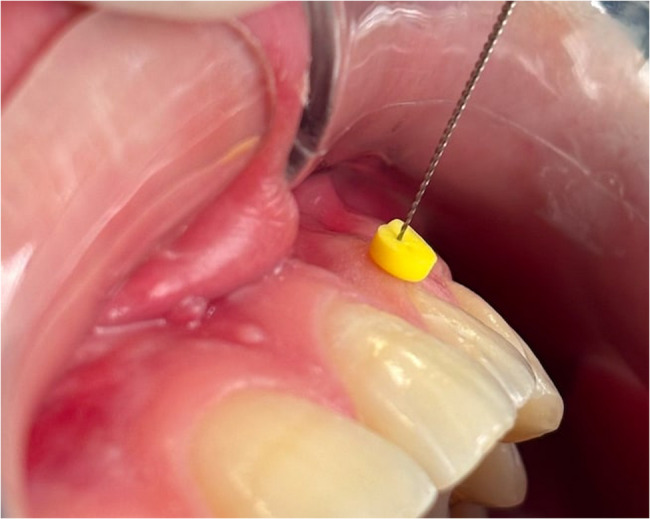

Xylocaine spray (10% lidocaine) was applied as an analgesic prior to transgingival measurement. GT was measured by transgingival probing with a 20-gauge endodontic file (20 K-files; Kerr, Brea, CA, USA) in the buccal region of the incisors, canines, premolars and first molars in both the maxilla and mandible after determining the point corresponding to the base of the gingival sulcus with a 0.4 mm diameter UNC probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois, USA). An endodontic file with a plastic stopper was inserted vertically into the gingiva until it reached the tooth or bone (Fig. 1). To prevent any undesirable movement of the plastic stopper, a new narrow hole was drilled to keep the file fixed in place and the file was kept fixed within the stopper, in accordance with the methodology of Kloukos et al. [18]. The distance between the stopper and the tip of the caliper was measured to an accuracy of 0.01 mm using a digital caliper (Asimeto, Hong Kong) (Fig. 2). To ensure measurement accuracy, the tips of the digital caliper were modified by lengthening them with composite filling. KGW was determined according to the functional method proposed by Olsson et al. [19] by measuring the distance between the mid-buccal position of the marginal gingiva and the mucogingival junction (rounding off to the nearest 0.5 mm).

Fig. 1.

Measurement of GT using a #20 endodontic file (20 K-file; Kerr, Brea, CA, USA) by the transgingival method

Fig. 2.

A Modified digital caliper (Asimeto, Hong Kong), measurement of the distance between the stopper and the caliper tip using a modified digital caliper

Model measurements

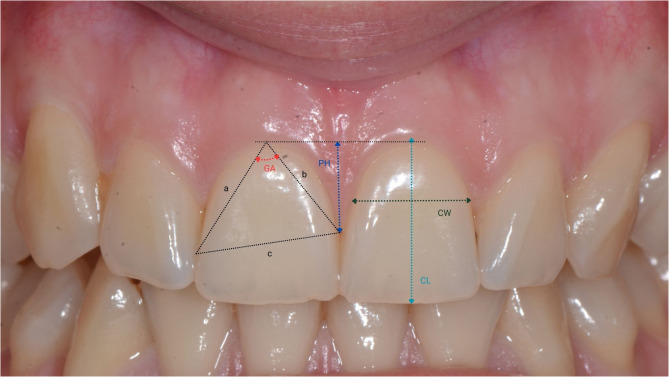

Study models were created by taking alginate impressions of the upper and lower jaws in a stock tray and casting them in Type 3 hard plaster (Durguix, Girona, Spain) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Casts were measured, and the following parameters (Fig. 3) were recorded:

Fig. 3.

Representation of reference points for measurements of Crown width (CW), Crown length, Papilla height (PH), Gingival angle (GA)

Crown length (CL): the distance between the gingival margin, or, if discernible, the cemento-enamel junction, and the incisal edge of the crown.

Crown width (CW): the distance between the approximal tooth surfaces at the borderline between the cervical (C) and middle (M) portions of the crown, identified after dividing the length of the crown into three equal sections (cervical, middle, incisal).

Papilla Height (PH) was determined by measuring the distance between the zenith of the adjacent teeth and the perpendicular line connecting to the apex of the papilla on the mesial aspect of each tooth.

Gingival Angle (GA): the angle between the two lines that connect the most apical portion of the gingival margin and the most coronal portions of the contact surface.

CL, CW, and PH were measured using a digital caliper (Asimeto, Hong Kong) according to the Olsson et al. [19], and GA was measured using a digital angle gauge (BTS, Ljubljana, Slovenia) with a measurement range of 0-999.9º and a precision of 0.3º. CW/CL ratios were also calculated and recorded for each tooth.

Intra-examiner repeatability

Intra-examiner reliability was assessed by repeating the GT measurements on 10 randomly selected patients after two weeks. Measurements were performed on a total of 60 teeth in the maxillary anterior region to ensure clinical accessibility and reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS (Version 23, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Spearman’s rho Correlation Coefficient was used to evaluate the correlations between GT and KGW, PH, CW, CL. Binary Logistic Regression Analysis was used to evaluate the effects of both categorical and continuous variables on GT. For this analysis, based on GT measurements of right maxillary incisors (taken from the point corresponding to the base of the gingival sulcus), participants were divided into two groups: ‘Thin’ (GT ≤ 1 mm) and ‘Thick’ (GT > 1 mm). Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to assess the effects of these variables on the likelihood of having a thin or thick gingival phenotype. ROC Analysis was performed to determine cut-off values for predicting gingival phenotype. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. ICC analysis was used to examine the agreement between quantitative variables (GT measurements). ICC values range between 0 and 1, and are designated as follows: <0.5 = poor reliability; 0.5–0.75 = moderate reliability, 0.75–0.9 = good reliability, > 0.9 = excellent reliability [20]. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations and median (minimum-maximum).

Results

This study examined 24 teeth (incisors, premolars and first molars) in 50 patients (21 females, 29 males; age range: 18–31; mean age 22.42 ± 2.87 years), for a total of 1,200 teeth. Mean measurements for clinical and morphometric parameters are presented in Table 1, and mean GT and KGW values are presented (by tooth group) in Table 2. Gingival phenotype (GP) was classified as ‘thick’ in 518 teeth (43.2%) and as ‘thin’ in 682 teeth (56.8%). Mean GT was found to be 0.95 ± 0.25 mm.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics (mean ± SD) of clinical and morphometric parameters (total, and by arch/location)

| Parameters | TOTAL (n = 1200) |

Maxilla Right Posterior (n = 150) |

Maxilla Anterior (n = 300) |

Maxilla Left Posterior (n = 150) |

Mand. Right Posterior (n = 150) |

Mand. Anterior (n = 300) |

Mand. Left Posterior (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT (mm) | 0.95 ± 0.25 | 1.08 ± 0.19 | 0.95 ± 0.22 | 1.11 ± 0.19 | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 0.75 ± 0.18 | 1.01 ± 0.24 |

| KGW (mm) | 5.36 ± 1.43 | 5.88 ± 1.32 | 6.29 ± 1.37 | 5.92 ± 1.15 | 4.67 ± 1.02 | 4.62 ± 1.2 | 4.59 ± 1.04 |

| PH (mm) | 3.92 ± 1.42 | 3.82 ± 0.66 | 3.82 ± 0.69 | 3.74 ± 0.74 | 4.26 ± 3.38 | 3.98 ± 0.81 | 3.85 ± 0.62 |

| CW (mm) | 6.72 ± 0.94 | 6.55 ± 1.6 | 6.71 ± 0.94 | 6.58 ± 1.7 | 7.18 ± 1.84 | 5.15 ± 0.99 | 7.19 ± 1.95 |

| CL (mm) | 7.74 ± 1.33 | 6.83 ± 0.92 | 8.73 ± 1.1 | 6.65 ± 0.97 | 7.11 ± 0.92 | 8.26 ± 1.25 | 7.31 ± 0.95 |

| CW/CL | 1.22 ± 6.09 | 0.99 ± 0.33 | 0.77 ± 0.11 | 1.02 ± 0.34 | 1.01 ± 0.36 | 0.71 ± 1.53 | 1.02 ± 0.36 |

| GA (°) | 78.54° ±17.18 | 87.6 ± 13.85 | 81.07 ± 7.62 | 86.11 ± 14.06 | 89.63 ± 14.88 | 58.81 ± 12.56 | 85.46 ± 14.93 |

GT gingival thickness, KGW keratinized gingival width, PH Papilla height, CW crown width, CL crown length, CW/CL crown width/ crown length, GA gingival angle, Mand mandibula

Table 2.

GT and KGW mean and standard deviation values for tooth groups

| Tooth Group (Mean ± SD) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 30 | 16–26 | 15–25 | 14–24 | 13–23 | 12–22 | 11–21 | 31–41 | 32–42 | 33–43 | 34–44 | 35–45 | 36–46 |

| GT (mm) | 1.18 ± 0.24 | 1.12 ± 0.2 | 0.97 ± 0.16 | 0.87 ± 0.19 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.23 | 0.74 ± 0.19 | 0.74 ± 0.18 | 0.76 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 1.02 ± 0.22 | 1.24 ± 0.17 |

| KGW (mm) | 6.32 ± 1.47 | 5.9 ± 1.31 | 5.44 ± 1.19 | 5.95 ± 1.46 | 6.7 ± 1.27 | 6.21 ± 1.25 | 4.75 ± 1.23 | 4.84 ± 1.22 | 4.27 ± 1.07 | 3.93 ± 0.84 | 4.68 ± 1.07 | 5.28 ± 0.9 |

GT Gingival thickness, KGW keratinized gingival width

GT and GA showed a moderate positive correlation, while GT and KGW showed a weak positive correlation, and GT and CL showed a weak negative correlation. (Table 3) There was no statistically significant correlation found between GT and CW/CL.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of clinical and morphological parameters

| KGW (mm) | PH (mm) | CW (mm) | CL (mm) | GA (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT (mm) | 0.431 | – 0.185 | 0.456 | – 0.398 | 0.637 |

| < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Spearman’s correlation analysis, *P < 0.001, r: Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient; KGW:Keratinized gingival width, PH Papilla height, CW Crown width, CL Crown length, GA Gingival angle

GT showed a tendency to decrease with increases in CL (OR = 1.179; OR = 1.204, p < 0.001). KGW was significantly higher in the ‘Thick’ group as compared to the ‘Thin’ group (OR = 0.762; OR = 0.767, p < 0.001). There was no significant relationship found between GT and CW/CL (p > 0.050) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of the interaction of variables related to GT

| GT | Univariate | Multiple | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thick (n = 672) |

Thin (n = 528) |

OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex - N (%) | ||||||

| Female | 170 (35.4) | 310 (64.6) | 4.199 (3.285–5.368) | < 0.001* | 6.702 (4.942–9.089) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 502 (69.7) | 218 (30.3) | Reference | |||

| Age | 21.96 ± 3.18 | 22.96 ± 2.16 | 1.137 (1.09–1.186) | < 0.001 | 1.216 (1.157–1.279) | < 0.001 |

| Arc location -N (%) | ||||||

| Max. R. P | 93 (62) | 57 (38) | Reference | |||

| Max. anterior | 111 (37) | 189 (63) | 1.00 (0.77–1.32) | 0.972 | 2.78 (1.85–4.16) | < 0.001 |

| Max. L. P | 94 (62.7) | 56 (37.3) | 0.30 (0.21–0.43) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.61–1.55) | 0.905 |

| Mand. R. P | 72 (48) | 78 (52) | 0.60 (0.42–0.84) | 0.003 | 1.77 (1.12–2.80) | 0.015 |

| Mand. anterior | 10 (3.3) | 290 (96.7) | 27.13 (14.25–51.65) | < 0.001 | 47.32 (23.23–96.38) | < 0.001 |

| Mand. L.P | 65 (43.3) | 85 (56.7) | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 0.091 | 2.13 (1.34–3.38) | 0.001 |

| KGW (mm) | 5.59 ± 1.5 | 5.06 ± 1.26 | 0.762 (0.7–0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.767 (0.692–0.851) | < 0.001 |

| PH (mm) | 3.95 ± 1.78 | 3.88 ± 0.74 | 0.962 (0.865–1.07) | 0.475 | 0.94 (0.783–1.129) | 0.508 |

| CW (mm) | 8.82 ± 42.9 | 9.6 ± 52.71 | 1 (0.998–1.003) | 0.780 | 1.002 (0.999–1.005) | 0.233 |

| CL (mm) | 7.61 ± 1.31 | 7.9 ± 1.34 | 1.179 (1.08–1.287) | < 0.001 | 1.204 (1.077–1.347) | 0.001 |

| CW/CL | 1.19 ± 5.16 | 1.26 ± 7.11 | 1.002 (0.983–1.021) | 0.861 | 1.013 (0.992–1.035) | 0.220 |

| GA (°) | 79.12 ± 16.84 | 77.82 ± 17.59 | 0.996 (0.989–1.002) | 0.197 | 1.003 (0.994–1.012) | 0.479 |

Binary logistic regression analysis, *: P < 0.001, OR Odds ratio, Cl Confidence interval, KGW Keratinized gingival width, PH Papil height, CW Crown width, CL Crown length, GA Gingival angle, Max Maxilla, Mand Mandible, R.P Right Posterior, L.P Left Posterior

Univariate analysis showed that women were 4.1 times more likely than men to have ‘thin’ GT (OR:4.199, p < 0.001), whereas multivariate analysis found the probability to be 6.7 times greater (OR:6.702, p < 0.001). Both univariate and multivariate statistical models found GT to decrease with increasing age (OR:1.137, OR: 1.216; p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Both univariate and multivariate analysis showed GT in the maxillary right posterior region to be significantly higher in comparison to the maxillary anterior (OR = 2.78; p < 0.001), mandibular anterior (OR = 47.32; p < 0.001) regions. No statistically significant differences were found between the maxillary and mandibular anterior regions or between the mandibular anterior and posterior regions (p > 0.050) (Table 4).

ROC analysis used to determine gingival phenotype found statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in KGW, PH, CW, CL, CW/CL, and GA° measurements between ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ gingival phenotypes. In full mouth analysis, the cut-off values for KGW, CL and CW/CL were determined as ≤ 5.0 mm, ≥ 8.55 mm, and ≤ 0.66, respectively. The AUC values were 0.604, 0.557 and 0.560, respectively. In the maxillary anterior region, the cut-off values were CW ≤ 6.98 mm (AUC = 0.618), CW/CL ≤ 0.79 (AUC = 0.604) and GA° ≤ 84.6° (AUC = 0.638). In the maxillary right posterior region, the cut-off value was determined as GAo ≤84.4° (AUC: 0.665), and in the mandibular anterior region, GA° ≤ 58.0° (AUC: 0.687). In the mandibular right posterior region, multiple parameters showed predictive ability: KGW ≤ 5.0 mm (AUC = 0.657), PH ≥ 6.0 mm (AUC = 0.353), CW ≤ 6.75 mm (AUC = 0.737), CL ≥ 10.31 mm (AUC = 0.228), CW/CL ≤ 1.0 (AUC = 0.825), and GA° ≤ 83.3° (AUC = 0.819). In the mandibular left posterior region, the cut-off value was determined as CL ≥ 6.35 mm (AUC: 0.250). Table 5 summarized only statistically significant results. (p ≤ 0.001).

Table 5.

Cut-off values of full mouth and site-specific clinical and morphometric parameters in the prediction of gingival phenotype

| Parameter | Region | Cut-off | AUC (95% CI) | P value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ACC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGW (mm) |

Full mouth Mand. R. P |

≤ 5.0 ≤ 5.0 |

0.604 (0.572–0.636) 0.657 (0.57–0.745) |

< 0.001* < 0.001* |

64.52 70.7 |

52.69 54.7 |

51.8 66.7 |

65.31 59.3 |

57.9 63.7 |

| PH (mm) | Mand. R. P | ≥ 6.0 | 0.353 (0.262–0.444) | 0.001 | 1.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 44.1 | 44.5 |

| CW (mm) |

Max. anterior Mand. R. P |

≤ 6.98 ≤ 6.75 |

0.618 (0.551–0.685) 0.737 (0.658–0.817) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

55.0 59.8 |

66.1 84.4 |

49.6 83.1 |

70.8 62.1 |

61.9 70.5 |

| CL (mm) |

Full mouth Mand. R. P Mand. L.P |

≥ 8.55 ≥ 10.31 ≥ 6.35 |

0.557 (0.524–0.59) 0.228 (0.149–0.306) 0.25 (0.153–0.347) |

0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 |

33.97 0.0 100.0 |

78.14 100.0 4.6 |

55.0 0.0 34.0 |

60 43.8 100.0 |

49.63 43.8 36.1 |

| CW/CL |

Full mouth Max. anterior Mand. R. P |

≤ 0.66 ≤ 0.79 ≤ 1.0 |

0.56 (0.527–0.593) 0.604 (0.536–0.671) 0.825 (0.759–0.891) |

< 0.001 0.003 < 0.001 |

31.56 55.9 63.4 |

81.11 63.9 90.6 |

56.8 48.4 89.7 |

60.04 70.5 65.9 |

59.26 60.9 75.3 |

| GA° |

Max. R. P Max. anterior Mand. R. P Mand. anterior |

≤ 84.4 ≤ 84.6 ≤ 83.3 ≤ 58.0 |

0.665 (0.574–0.755) 0.638 (0.572–0.705) 0.819 (0.751–0.886) 0.687 (0.572–0.802) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.001 |

69.1 47.7 82.9 85.2 |

62.5 77.0 70.3 47.2 |

78.3 55.8 78.2 14.0 |

50.8 70.9 76.3 96.9 |

66.9 66.0 77.4 50.7 |

ROC Analysis, *: P < 0.001, KGW Keratinized gingival width, PH Papil height, CW Crown width, CL Crown length, GA Gingival angle, Max Maxilla, Mand Mandible, R.P Right Posterior, L.P Left Posterior, PPV Positive predictive value, NPV Negative predictive value, ACU Area under curve, CI Confidence interval, ACC Accuracy value.

The Intraclass Correlation Test (ICC) performed to determine accuracy and reproducibility of measurement showed excellent agreement (ICC = 0.990; p < 0.001).

Discussion

Gingival phenotype plays a crucial role in modulating the response of periodontal tissues to physical, chemical, and bacterial challenges, thereby contributing to the maintenance of periodontal health [3]. The long-term success of dental implants [21], as well as the outcomes of orthodontic, restorative, and periodontal therapies, is closely associated with soft tissue behavior [1]. Gingival phenotype is defined by GT and KGW, two terms used to describe soft tissue morphology. Measurements of GT can be used to assess gingival phenotype in a consistent and reproducible manner. Furthermore, GT has been associated with morphologic parameters such as crown width (CW)/crown length (CL), keratinized gingival width (KGW), papilla height (PH), and tooth position.

In the present study, gingival phenotype was classified solely by GT, in line with the methodology adopted by most previous studies in the field. Although gingival phenotype was defined as a combination of GT and KGW in the 2017 World Workshop Report [1], the same consensus report provided a classification threshold only for GT. De Rouck et al. [22] identified GT as a simple, objective, and reproducible parameter for phenotype assessment in morphometric analysis of maxillary anterior teeth. Similarly, Fischer et al. [23] found that GT was more strongly associated with phenotype variation than KGW or PH.

This study found mean values of 0.91 ± 0.22 mm for GT and 5.36 ± 1.43 mm for KGW. Although the literature includes many examples of mean GT measurements, few studies [24, 25] include full-mouth measurements. Our findings were consistent with those of a 2005 study of 33 patients conducted by Müller et al. [25], which found a mean full-mouth GT of 0.93 ± 0.12 mm. In contrast, Lee et al. [24] reported a mean GT of 1.39 ± 52 mm and mean KGW of 5.10 ± 1.41 mm. The difference in findings may be due to differences in study populations, namely, participants in Lee et al.’s [24] study were Asian, whereas participants in our study were Caucasian (Turks).

In this study, the interaction of age and gender with gingival phenotype was investigated as a secondary objective. While our study identified the probability of GT being thin to increase with increasing age, the probability rate was low, and the clinical significance of this result seems negligible given that the age range of our study group was between 18 and 31. In order to confirm these results, studies with a wider age range and sample size are needed. Both multivariate and univariate analysis conducted in our study found a statistically significant relationship between gender and GT, which was thinner in females than in males. While this is in line with studies by Vandana et al. [26] and Fischer et al., [27] a best-evidence consensus review conducted by Kim et al. [28]concluded that age and gender have no bearing on gingival phenotype. The observed gender-based differences in GT may be attributed to variations in estrogen and androgen hormone levels between female and men. Sex hormones have been shown to influence collagen synthesis, connective tissue density, and vascularization, potentially contributing to the relatively thinner GT observed in females [29]. In addition, sociocultural factors, such as females more proactive oral health behaviors and differences in oral hygiene practices, may also have an indirect but not direct effect on GT [3]; however, the effects of these factors are generally insufficient to fully explain the gender difference.

Due to the importance of the maxillary anterior region in esthetic planning, as well as the ease of measurement, studies of GT have been conducted mainly in this region. However, it is not clear whether soft and hard tissue measurements of maxillary teeth can serve as a guide for those of mandibular teeth. Pascual et al. [30] measured GT in the maxillary and mandibular anterior regions using three-point transgingival probing and reported that maxillary and mandibular GT were similar at the crestal level. Our study found both mean GT and mean KGW to be higher in the maxillary anterior region (GT: 0.95 ± 0.2 mm, KGW: 6.29 ± 1.37 mm) than in the mandibular anterior region (GT: 0.75 ± 0.18 mm, KGW: 4.62 ± 1.2 mm), although the differences between the two regions were not statistically significant. Studies comparing GT and KGW by region have reported conflicting results. Kurien et al. [31] reported that there was no statistically significant difference between the maxillary and mandibular anterior regions. Shao et al. [32] reported thicker GT and wider KGW in the maxillary arch (1.21 ± 0.27 mm GT, 5.95 ± 1.41 mm KGW; and 0.85 ± 0.24 mm GT, 4.79 ± 1.19 mm KGW) in the mandible in the Chinese population. Kolte et al. [2] reported a thicker GT and narrower KGW in the mandible, and Lee et al. [24] reported a thicker GT but narrower KGW in the maxilla. A recent systematic review [28] study reported no significant differences between maxillary and mandibular GT.

When examined by region, our study found GT to be significantly thicker in the maxillary posterior region as compared to both the maxillary anterior and mandibular anterior regions. This is in line with previous studies such as Lee et al., [24] which reported GT to increase from anterior to posterior. However, as our study showed, not all teeth in the posterior region had a thick GT: first premolar teeth were found to have a thinner GT when compared to all other tooth types. Interestingly, this regional difference in GT was not detected in the univariate analysis but became apparent in the multivariate analysis. This discrepancy is likely due to the ability of the multivariate models to adjust for confounding factors such as gender, age, and tooth morphology. Multivariate analysis provided a more refined and independent estimate of the effect of region on GT by accounting for these interacting variables. This highlights the importance of using multivariate approaches when attempting to isolate the specific contribution of anatomic region to gingival phenotype.

Few studies compare measurements between mandibular and maxillary anterior regions [26, 30–33], and even fewer report on measurements for individual tooth types [24, 34–36]. In one of those rare studies, Lee et al. [24] found GT measurements to be thinnest for mandibular incisors (0.7 ± 0.15 mm), first premolars (0.83 ± 0.15 mm) and maxillary canines (0.87 ± 0.19 mm) and KGW measurements to be narrowest for mandibular premolars (3.93 ± 0.84 mm) and mandibular canines (4.27 ± 1.07 mm). [24]

Our study found significant, a weak positive correlation between GTand KGW. This is in line with numerous previous studies assessing a correlation between GT and KGW [8, 36–38]. A recent systematic review study by Vlachodimou et al. [7] suggested that KGW appears to be associated with gingival phenotype and GT, with thick phenotypes characterized by broader KGW; however, the authors stated that no definitive conclusions could be drawn due to the heterogeneity of studies reviewed, which used different techniques and threshold values in measuring and classifying GT. Further research is required to better determine the relationship between GT and KGW.

A number of previous studies have looked at the relationship between periodontal parameters and tooth shape using the ratio of CW/CL. Olson et al. [39] examined the crown width/crown length (CW/CL) ratio of maxillary incisors and classified them as either short and wide (mean CW/CL = 0.88) or long and narrow (mean CW/CL = 0.56) and concluded that tooth morphology and GT are related. Müller et al. [34] identified young men with short and wide teeth as having either normal GT and narrow KGW or thick GT and wide KGW. Collins et al. [14] reported that 71% of square crown forms were associated with thin gingival phenotype. Furthermore, assessing the connection between gingival morphotype and CL and width as well as tooth shape and PH, Fischer et al. [40] concluded that only CL, not CW, could be connected with distinct gingival morphotypes. [40] The negative correlation our study found between GT to and CL supports this conclusion.

While some studies [14, 41–43] have reported connections between CW/CL and GT, the results of regression analysis conducted in our study are consistent with earlier studies [5, 40, 44, 45] reporting no connection between CW/CL and GT. The heterogeneity in the literature may be linked to the difficulties in determining the best reference points for CL (e.g., due to incisor wear, gingivitis, and attachment loss) and CW (e.g., due to irregularities in gingival papillae) when taking crown measurements. According to Shao et al., [32] differences in outcomes could also be related to the difference in ‘clinical CL’ – which is measured from the incisal edge to the free gingival margin – and ‘anatomical CL’ – which is measured from the incisal edge to the CEJ. Moreover, errors in measurements made from diagnostic models related to shrinkage and distortion of alginate or hard plaster should not be overlooked. To obtain more accurate measurements, standard-scale diagnostic photos or three-dimensional scanning could be used.

In this study, ROC analysis provided a direct comparison between full-mouth and site-specific cut-off values for the classification of gingival phenotype. Although full-mouth cut-off values, such as KGW and CW/CL, showed limited diagnostic accuracy (AUC < 0.61; sensitivity: 33.9–64.5%, specificity: 52.7–81.1%), site-specific analysis (especially in the mandibular right posterior) provided higher accuracy. Olsson et al. [19] identified a mean CW/CL of 0.76 for the central incisors, whereas Chou et al. [6] identified a CW/CL of 0.79 for the thick gingival phenotype in Taiwanese. Our maxilla anterior CW/CL cut-off value (≤ 0.79) is consistent with these preliminary findings. Yin et al. [5] identified a cut-off value of 95.95° GA for the thick phenotype in the maxillary incisors. Our analysis determined GA values <84.6° to classify the thin phenotype. The observed lower GA values may be attributed to methodological differences. A cut-off value of 5 mm was defined for KGW, which was moderate in predictive ability observed in both full-mouth and mandibular right posterior analyses. Cortellini et al. [46] reported mean KGW values of 5.72 and 4.15 mm for thick and thin phenotypes, respectively, but did not provide a cut-off value. CL and PH showed statistically significant cut-off values in certain regions, but their AUC values remained below 0.60, indicating poor predictive ability. These cut-off values may provide valuable insights and contribute to the literature in clinical diagnosis, treatment planning and decision-making processes based on gingival phenotype. Furthermore, these site-specific data could potentially be integrated into digital planning systems to support the design of soft tissue–compatible crown morphology and the early prediction of soft tissue augmentation needs, thus guiding phenotype-based risk analysis prior to implant or restorative procedures.

In addition to CW, CL, CW/CL and KGW, this study also examined the normal range of PH and GA and their correlation with GT and other periodontal parameters. The PH and GT showed a significant weak negative correlation, The negative relationship we found between GT and PH is in line with Yingzi et al. [9], which reported short and thin papillae to be associated with a thick phenotype and long and thick papillae to be associated with a thin phenotype, but contrasts with Chow et al., [10] who reported a positive relationship between GT and PH.

Our study also found a moderate positive correlation between GA and GT. This is in line with Olsson et. al. [19], who reported teeth with thin GT to have a smaller GA angle and a more curved, gingival contour. This relationship has also been supported by more recent studies [5, 9, 47], although it conflicts with the findings from a study conducted in Saudi Arabia by AlQahtani et al. [12] Differences in study findings can be attributed to differences in racial, ethnic, and gender compositions of the study populations.

A number of limitations should be taken into consideration when assessing the findings of this study, namely, the limited age range of participants (18–31 years) and the possibility of measurement errors related to the use of plaster models.

Conclusion

The current study findings suggest that a better understanding of the gingival phenotype, including tooth and gingival parameters, site-specific variations, and patient-related factors such as age and gender, may help inform more personalized approaches to periodontal, restorative, and esthetic treatment planning.

Within the limitations of this study, GT was found to be thinner in females as compared to males. No relationship was found between GT and crown shape. GT exhibited positive correlations with KGW, GA, CW and negative correlations with CL and PH. PH demonstrated a positive correlation with CL and negative correlations with GT, KGW and GA. No correlation was found between GT and CW/CL. These findings support the hypothesis that people with thick phenotypes have more square and wider crown morphology, shorter PH, and wider KGW.

The different GTs in different arch locations found in this study confirm site-specific variations in phenotype, indicating that phenotype classification based on the maxillary anterior region alone may be insufficient for reliably determining GT in other areas. Furthermore, differences in study findings may be impacted by factors such as the heterogeneity of phenotype classifications, shifts in GT threshold values over time, and differences in measurement techniques. In order to validate our study results, larger studies with more diverse sample populations are needed.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- GT

Gingival thickness

- KGW

Keratinized gingival width

- PH

Papilla height

- CW

Crown width

- CL

Crown length

- CW/CL

Crown width/Crown length ratio

- GA

Gingival angle

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- OMUKAEK

Ondokuz Mayis University Clinical Research Ethics Committee

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- UNC

University of North Carolina Probe

- BT

Bone thickness

- OR

Odds Ratio

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- CI

Confidence Interval

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- ACC

Accuracy

- Mand

Mandibula

- Max

Maxilla

Author contributions

RG and ML contributed to the design and implementation of the research. SY contributed to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. ML conceived the original manuscript and supervised the project.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Sude Yildirim Bolat),upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jepsen S, Caton JG, Albandar JM, Bissada NF, Bouchard P, Cortellini P, et al. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 world workshop on the classification of periodontal and Peri-Implant diseases and conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S237–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolte R, Kolte A, Mahajan A. Assessment of gingival thickness with regards to age, gender and arch location. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18(4):478–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alhajj WA. Gingival phenotypes and their relation to age, gender and other risk factors. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kan JY, Morimoto T, Rungcharassaeng K, Roe P, Smith DH. Gingival biotype assessment in the esthetic zone: visual versus direct measurement. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2010;30(3):237–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin XJ, Wei BY, Ke XP, Zhang T, Jiang MY, Luo XY, et al. Correlation between clinical parameters of crown and gingival morphology of anterior teeth and periodontal biotypes. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou YH, Tsai CC, Wang JC, Ho YP, Ho KY, Tseng CC. New classification of crown forms and gingival characteristics in Taiwanese. Open Dent J. 2008;2:114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlachodimou E, Fragkioudakis I, Vouros I. Is there an association between the gingival phenotype and the width of keratinized gingiva?? A systematic review. Dent J (Basel). 2021;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Egreja AM, Kahn S, Barceleiro M, Bittencourt S. Relationship between the width of the zone of keratinized tissue and thickness of gingival tissue in the anterior maxilla. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2012;32(5):573–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yingzi X, Zhiqiang L, Peishuang W, Yimin Z, Shanqing G, Xueguan L, et al. Relationship of gingival phenotypes and faciolingual thickness, papilla height, and gingival angle in a Chinese population. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2021;41(1):127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow YC, Eber RM, Tsao YP, Shotwell JL, Wang HL. Factors associated with the appearance of gingival papillae. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(8):719–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu JH, Yeh CY, Chan HL, Tatarakis N, Leong DJ, Wang HL. Tissue biotype and its relation to the underlying bone morphology. J Periodontol. 2010;81(4):569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AlQahtani NA, Haralur SB, AlMaqbol M, AlMufarrij AJ, Al Dera AA, Al-Qarni M. Distribution of smile line, gingival angle and tooth shape among the Saudi Arabian subpopulation and their association with gingival biotype. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(Suppl 1):S53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer KR, Richter T, Kebschull M, Petersen N, Fickl S. On the relationship between gingival biotypes and gingival thickness in young Caucasians. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26(8):865–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins JR, Pannuti CM, Veras K, Ogando G, Brache M. Gingival phenotype and its relationship with different clinical parameters: a study in a Dominican adult sample. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(8):4967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Löe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):329–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25(4):229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloukos D, Koukos G, Doulis I, Sculean A, Stavropoulos A, Katsaros C. Gingival thickness assessment at the mandibular incisors with four methods: A cross-sectional study. J Periodontol. 2018;89(11):1300–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsson MLJ, Marinello CP. On the relationship between crown form and clinical features of the gingiva in adolescents. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20(1993):570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Avila-Ortiz G, Urban IA, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. Peri-implant soft tissue phenotype modification and its impact on peri-implant health: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2021;92(1):21–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Rouck T, Eghbali R, Collys K, De Bruyn H, Cosyn J. The gingival biotype revisited: transparency of the periodontal probe through the gingival margin as a method to discriminate thin from Thick gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(5):428–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer KR, Buchel J, Testori T, Rasperini G, Attin T, Schmidlin P. Gingival phenotype assessment methods and classifications revisited: a preclinical study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(9):5513–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee WZ, Ong MMA, Yeo AB. Gingival profiles in a select Asian cohort: A pilot study. J Investig Clin Dent. 2018;9(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Muller HP, Kononen E. Variance components of gingival thickness. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40(3):239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandana KL, Savitha B. Thickness of gingiva in association with age, gender and dental arch location. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(7):828–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer KR, Buchel J, Kauffmann F, Heumann C, Friedmann A, Schmidlin PR. Gingival phenotype distribution in young Caucasian women and men - An investigative study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022;8(1):374–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DM, Bassir SH, Nguyen TT. Effect of gingival phenotype on the maintenance of periodontal health: an American academy of periodontology best evidence review. J Periodontol. 2020;91(3):311–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mascarenhas P, Gapski R, Al-Shammari K, Wang HL. Influence of sex hormones on the periodontium. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(8):671–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pascual A, Barallat L, Santos A, Levi P Jr., Vicario M, Nart J, et al. Comparison of periodontal biotypes between maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth: A clinical and radiographic study. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2017;37(4):533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurien JT, Narayan V, Rm B, Thomas PAG. The influence of gingival biotypes on periodontal health: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary care center. IP Int J Periodontology Implantology. 2021;6(2):103–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao Y, Yin L, Gu J, Wang D, Lu W, Sun Y. Assessment of periodontal biotype in a young Chinese population using different measurement methods. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Rocca AP, Alemany AS, Levi P Jr., Juan MV, Molina JN, Weisgold AS. Anterior maxillary and mandibular biotype: relationship between gingival thickness and width with respect to underlying bone thickness. Implant Dent. 2012;21(6):507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller HPE, Thomas. Gingival phenotypes in young male adults. J Clin Periodontai. 1997;24(1997):65-7165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Müller HP, Eger T. Masticatory mucosa and periodontal phenotype: a review. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2002;22(2):172–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eger T, Müller HP, Heinecke A. Ultrasonic determination of gingival thickness. Subject variation and influence of tooth type and clinical features. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23(9):839–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer KR, Kunzlberger A, Donos N, Fickl S, Friedmann A. Gingival biotype revisited-novel classification and assessment tool. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(1):443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah R, Sowmya NK, Mehta DS. Prevalence of gingival biotype and its relationship to clinical parameters. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6(Suppl 1):S167–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsson M, Lindhe J. Periodontal characteristics in individuals with varying form of the upper central incisors. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18(1):78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer KR, Grill E, Jockel-Schneider Y, Bechtold M, Schlagenhauf U, Fickl S. On the relationship between gingival biotypes and supracrestal gingival height, crown form and papilla height. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25(8):894–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein JM, Lintel-Höping N, Hammächer C, Kasaj A, Tamm M, Hanisch O. The gingival biotype: measurement of soft and hard tissue dimensions—a radiographic morphometric study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(12):1132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stellini E, Comuzzi L, Mazzocco F, Parente N, Gobbato L. Relationships between different tooth shapes and patient’s periodontal phenotype. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48(5):657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chavda MR, Bhavsar N, Gaonkar R, Patki S, Nair S. GINGIVAL BIOTYPE- AN APPRAISAL IN THE ESTHETIC ZONE. Int J Sci Res. 2020:1–2.

- 44.Babayiğit O, Yarkaç FU, Atay ÜT, Şen DÖ, Öncü E. Evaluation of relationship between gingival phenotype and periodontal status. Pharmacophore. 2022;13(1):72–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peixoto A, Marques TM, Correia A. Gingival biotype characterization–a study in a Portuguese sample. Int J Esthet Dent. 2015;10(4):534–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortellini P, Bissada NF. Mucogingival conditions in the natural dentition: narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(S20):S190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joshi A, Suragimath G, Zope SA, Ashwinirani SR, Varma SA. Comparison of gingival biotype between different genders based on measurement of dentopapillary complex. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(9):ZC40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Sude Yildirim Bolat),upon reasonable request.