Abstract

Background

The enteric nervous system (ENS), which arises from enteric neural crest cells (ENCCs), plays important roles in many aspects of gastrointestinal tract function, including motility, secretions, blood flow and hormone release. Defects in ENS development could lead to a broad range of disorders, including Hirschsprung’s disease (HSCR), which is characterized by missing nerve cells in the distal segment of the colon. Here, we identify EMB as an evolutionarily conserved regulator of ENS development.

Methods

We first examined EMB expression in human and mouse intestines using scRNA-seq data and immunofluorescence staining. To investigate its role in ENS development, we constructed Emb-knockout zebrafish and mouse models. To explore the underlying mechanisms, we focused on ENCCs and analyzed their proliferation and migration using migration assays in explant guts and organoid cultures. Finally, we assessed rare EMB variants in a cohort of HSCR patients.

Results

In zebrafish, loss of emb leads to a decrease number of enteric neurons and impaired intestinal transit ability. In mice, knockout of Emb causes HSCR-like phenotypes and defects. In vitro experiments, including explant mouse gut and organoid cultures, show that EMB is required for both the proliferation and migration of ENCCs. Mechanistically, EMB binds to and recruits the phosphatase complex PP2A to the cellular membrane to facilitate the activation of PI3K-AKT pathway, thereby promoting ENCCs development. Indeed, application of PI3K or AKT agonists partially restores the ENS developmental defects in zebrafish emb mutants. Furthermore, rare variants of EMB may potentially contribute to the pathology of HSCR in humans.

Conclusions

EMB is required for ENS development by regulating the proliferation and migration of the ENCCs. Mechanistically, EMB recruits PP2A to the cell membrane, reducing cytoplasmic dephosphorylation activity and promoting the activation of the PI3K signaling pathway.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13073-025-01538-1.

Keywords: EMB, Enteric nervous system, Neural crest cell, Hirschsprung’s Disease, PI3K pathway

Background

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is considered a little brain in the bowel, which plays pivotal roles in controlling intestinal functions including motility, secretions, blood flow and hormone release [1, 2]. The ENS is derived from enteric neural crest cells (ENCCs), which are primarily derived from the vagal neural tube with a smaller portion from the sacral neural tube [2, 3]. Upon arriving in the intestine, the ENCCs continue to migrate from the rostral to the caudal direction to colonize the entire intestine [4]. During migration, ENCCs exhibit robust concurrent proliferation [5]. Importantly, the two processes are reciprocally dependent on each other [6]. The colonized ENCCs in the intestine eventually differentiate into various types of neurons and glia to form the complex neural network of the ENS [7]. Therefore, the formation of a functional ENS represents remarkable coordination of developmental programs. Vagal and sacral-derived ENCCs must undergo precisely timed proliferation, extensive rostrocaudal migration, and differentiation into diverse neuronal and glial subtypes, while interacting with the developing gut microenvironment. Many genes involved in cell adhesion, cytoskeleton, signaling transduction and epigenetic regulation have been implicated in ENS development, such as RET, GDNF and SOX10 [8–10]. These findings lead to a comprehensive understanding of the molecular processes underlying ENS development, yet more players may remain to be identified, and the interdependent processes of proliferation and migration remain incompletely defined.

Malformation or dysfunction of the ENS leads to various types of intestinal disorders, including Hirschsprung’s disease (HSCR), which occurs in approximately 1/5,000 newborns [11–14]. HSCR is typically characterized by an uninnervated intestinal segment (aganglionosis), which leads to motility defects and enlarged colon [15, 16]. Defects in migration, proliferation, differentiation, or survival of the ENCCs have been associated with HSCR [17, 18]. Histologically, short-segment HSCR (S-HSCR), in which the aganglionic region extends up to the splenic flexure, occurs in about 80% of HSCR cases, long-segment HSCR (L-HSCR), in which aganglionosis extends beyond the splenic flexure, occurs in about 15% of cases and total colonic aganglionosis (TCA) occurs in 3%-7% of patients [1, 19]. Clinical manifestations of HSCR include constipation, delayed passage of meconium, abdominal distension, vomiting and even growth failure [20]. Inappropriate treatments may cause death mostly due to the complications of HSCR-associated enterocolitis or bowel perforation [1, 21, 22]. Genetic factors including common noncoding variants, rare coding variants, and copy-number variants are considered to be the major causes of HSCR [23, 24]. More than 20 genes have been associated with HSCR in previous studies, including RET [25], EDNRB [26], EDN3 [27], GDNF [28], PHOX2B [29, 30], ECE1 [30], SOX10 [31], ZEB2 [32], and NRG1 [33, 34], which are involved in various aspects of enteric nervous system development. However, the genetic architecture of HSCR is still not fully illustrated [35].

Embigin (EMB) encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein and belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily. It has been shown that EMB is involved in the metastasis and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [36] and the progression of prostate cancer [37], implicating EMB in promoting the proliferation and migration of various cancer cells. In the sebaceous gland, EMB functions as a fibronectin receptor and regulates cell adhesion and metabolism [38]. In the nervous system, EMB is found to promote the sprouting of motor nerve terminals at the neuromuscular junction in mice [39]. In various systems, EMB appears to be involved in processes related to cellular membrane dynamics. However, the molecular mechanisms by which EMB is participating in the above processes are still poorly understood. Moreover, it has been shown that EMB is highly expressed in the developing gut at embryonic days E8.5d and E13.5d in mice [40]. This expression profile, combined with its known functions in adhesion and migration, suggests its potential involvement in ENS development. Here, we identify EMB as a potential regulator of ENS development and characterized the molecular and cellular functions of EMB.

Methods

Laboratory animals and specimens

All protocols for human sample collection in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (approval numbers: 2020-S226 and 2021-S033). All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. Experiments involving zebrafish and mice were approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (Ethical approval number: HZAUMO-2017-048). The key techniques and animals used in this manuscript were summarized below.

Mouse husbandry and euthanasia

All mice used in this study were maintained under Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) conditions within a controlled environment facility. Standard husbandry conditions included a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 50-60%, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Animals had ad libitum access to standard laboratory rodent chow and water, and their health was monitored daily throughout the study period. Euthanasia was performed using ethically approved methods: mice were first rendered unconscious by carbon dioxide (CO₂) inhalation, followed by cervical dislocation to ensure death. All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with institutional policies and national regulations governing the ethical use of laboratory animals.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence of human and mouse colon

Colon tissues were obtained from children without gastrointestinal diseases due to traffic accidents. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded colon tissues were sectioned at 5 μm and baked at 60 °C for 24 h. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded ethanol (100%-70%), and subjected to antigen retrieval with citrate buffer (1 ×, G1202, Servicebio, China), followed by treatment with 3% H2O2 for 30 min. After rinsing, slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-EMB primary antibody (ab127692, Abcam, UK); nonimmune serum was used for negative controls. The following day, sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (GB23303, Servicebio, China) for 30 min, developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; GDP1061, Servicebio, China), and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (G1004 and G1001, Servicebio, China). Images were acquired using an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan), and DAB signals were quantified with ImageJ (ver.1.8.0).

For immunofluorescence in both human and mouse tissues, colon sections from E13.5d mouse embryos and the aforementioned pediatric samples were prepared. The primary antibodies used were EMB (ab127692, Abcam, UK) and Tuj1 (ab78078, Abcam, UK). The corresponding secondary antibody combinations included either Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647) (ab150075, Abcam, UK) with Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (ab150113, Abcam, UK), or Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (ab150077, Abcam, UK) with Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647) (ab150115, Abcam, UK), in order to visualize EMB expression in neurons.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets and analysis

In our exploration of the functional roles of EMB in gut and ENS development, we leveraged publicly available Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets to scrutinize the specificity of gene expression across different cell types. For humans, we re-analyzed the cell type-specific gene expression profiles within the human fetal ENS, accessing data through the website https://simmonslab.shinyapps.io/FetalAtlasDataPortal/ [41–43]. For mice, we scrutinized the previously published scRNA-seq data derived from embryonic ENS samples isolated from the small intestine of Wnt1Cre-R26RTomato mice at E15.5d, aiming to elucidate the cell type-specific patterns of EMB expression [44].

Zebrafish housing/breeding

The AB-strain zebrafish were maintained according to standard procedures. Embryos and larvae were raised in E3 medium at 28 ℃ in an illuminated incubator within a 14:10 light/dark cycle. 0.003% N-phenylthiourea was added to E3 medium to inhibit melanization. Maintenance of adult zebrafish was performed in a recirculating system at 28 °C.

Morpholino knockdown of emb and ret

Morpholino knockdown of emb and ret was carried out as previously described [45]. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides and mismatch mforpholino targeting the genes were designed and synthesized by Genetools. Sequences and dosages of all MOs were provided in the following:

(splice blocker) ret: 5’- GTCAATCATAAGTGTTAATGTCACAA-3’.

ret-mismatch: 5’- GTgAAaCAaAAcTGaTgATcTCtCAt-3’.

(translation blocker) emb: 5’- TCCTACTATACTGCACCTTTTCGGT-3’.

emb-mismatch: 5’- TCCaAgTAaAgTGCtGGaTTaCGgT-3’.

The maximum dose of each MO that produced no apparent malformations was selected for injection at the one-cell stage of zebrafish embryos. Embryos were injected with 5 ng MO, and knockdown efficiency was confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot, as detailed in the supplementary materials.

CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing in zebrafish

To generate emb knockout zebrafish, the sgRNA (GTTGTACTGGAGGACTGAGG) and Cas9 mRNA were injected into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos. The injected embryos were raised for 3 months and genotyped by dorsal fin clipping and Sanger sequencing of the target region [46]. F0 zebrafish with chimeric mutations were backcrossed and homozygous emb mutants were isolated by standard F3 screen procedures. Primers used for target region amplification: F: 5’- AGGAGGAGCTGAAAGCGAAC-3’; R: 5’- GCACACTAAAAAGTGAAGATGCG-3’. The identification of different genotypes (emb+/+, emb+/- and emb-/-) of zebrafish was carried out by Sanger sequencing [46]. The mutant was backcrossed with the wild type multiple times to eliminate potential off-target effects.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Zebrafish embryos were collected and processed for whole-mount ISH as previously described [47]. A 832-bp fragment of the crestin cDNA was amplified using the following primers:

Forward: 5’- GAGAAGCCCTCATCAGAGAGTTTG -3’,

Reverse: 5’- TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTTGCTTGTCAGGCAGAATCAGG -3’.

A T7 promoter was added to the reverse primer. The ISH probe was then generated by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining in zebrafish

Whole-mount immunofluorescent staining was performed using the anti-HuC/D antibody (A-21271, Invitrogen, USA) or anti-p-Histone H3 antibody (9701S, Cell Signaling Technology, USA). Embryos were fixed overnight in 4% PFA and rinsed three times with PBS. Following a 1 h block at room temperature in 2% goat serum and 2 mg/mL BSA (in PBS), samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After two 10 min washes in PBS, embryos were treated with secondary antibodies (Goat anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor™ 488, A-11001, Invitrogen; or Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor™ 555, A-21428, Invitrogen; 1:1000 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Confocal images were acquired using an LSM 800 microscope (Zeiss, Germany), and fluorescence intensity or labeled cell counts were quantified with ImageJ (v1.8.0).

Zebrafish intestinal transit assay

As reported previously [48], the tracer was prepared by combining 100 mg egg yolk, 150 μL fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (1.0 μm, F13081, Invitrogen, USA), and 50 μL deionized water. For 7-dpf zebrafish larvae, about 2 mg of tracer powder was added to each Petri dish in the morning. To minimize the potential damage caused by repeated anesthesia and imaging procedures in zebrafish, we anesthetized the larvae 1 h after feeding with the fluorescent tracer. Specifically, we added 900 μL of E3 medium and 100 μL of 0.2% tricaine (E10521, Sigma, USA) solution to each well of a 24-well plate, resulting in a final tricaine concentration of 200 mg/L. After anesthesia, the larvae were rinsed with E3 medium to remove residual tricaine, then embedded in low-melting-point agarose for immobilization. Once the larvae were properly positioned and the agarose had cooled and solidified, imaging was performed immediately. Zebrafish remained viable and immobilized in agarose, without the need for re-anesthesia during subsequent imaging at 3 h and 6 h using a fluorescent dissecting microscope (Axio Zoom.V16, Zeiss, Germany). Intestinal transit was scored by dividing the gut into four regions based on anatomical landmarks, with larvae grouped according to the anterior extent of the tracer [48–50]

RNA sequencing of the zebrafish larval intestine

For intestinal tissue isolation, 5 dpf zebrafish larvae were anesthetized in 200 mg/L tricaine (E10521, Sigma, USA) to achieve immobility. Under a dissection microscope, fine-tipped forceps were used to gently grasp the body wall posterior to the yolk sac. The visceral mass, containing the intestine and associated organs (including the pancreas, liver, and pancreatic-biliary ductal system), was carefully dissected away by posterior traction. The target intestinal tissue was then meticulously separated from co-isolated non-target tissues, with attached hepatobiliary structures (pancreas, liver), muscle fragments, skin, and debris being removed [51]. Purified intestinal tissue was subsequently collected for RNA extraction. The intestines of 60 embryos were pooled, and three biological replicates were prepared for each genotype. Total RNA extraction was performed using the TRIZol reagent (15596026CN, Invitrogen, USA). The RNA sequencing was then performed. DESeq2 (ver.1.34.0) was applied to perform differentially expressed gene analysis and a filter of |log2 (FoldChange)|> 1 & p.adj < 0.05 was applied. The Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways (KEGG) analyses were performed [52, 53]. Differential expression genes were shown in Additional file 1: Dataset S1.

PI3K/AKT agonist

PI3K agonist 740-Y-P (HY-P0175, MedChemExpress, USA) and AKT agonist SC79 (HY-18749, MedChemExpress, USA) were used to activate the PI3K signaling cascade. For zebrafish exposure, drug concentrations for 740-Y-P (5 μg/mL) and SC79 (1 μg/mL) were chosen as the maximal concentrations at which no obvious malformations or mortality were observed in zebrafish embryos after incubation. The embryos were then incubated with the presence of 740-Y-P or SC79 until 5 dpf. For N-2a cells, the agonists were added to the culture medium (740-Y-P, 30 μM and SC79, 0.4 μg/mL).

Generation of Emb knockout mice

CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing technology was used to generate Emb knockout alleles in C57BL/6 J strain. An sgRNA targeting exon 3 of Emb was co-injected with Cas9 mRNA into the zygotes, and a 13 bp deletion allele was isolated in the progenies. Mice were genotyped by Sanger sequencing [46]. Quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting of EMB (ab127692, Abcam, UK) were performed to validate the knockout efficiency.

Identification of different genotypes of Emb+/+, Emb+/- and Emb-/- mice

Female and male mice of the Emb+/- genotype were mated to obtain offspring, and tail clipping was performed. Digestion was carried out using the One Step Mouse Genotyping kit (PD101-01, Vazyme, China) to obtain the target DNA. DNA amplification was conducted using PCR. The PCR primers used were as follows,

Emb-F: 5’-GGA GAG TAA GGA AGGGAGCTAG-3’;

Emb-R: 5’-GGA TTTATG AGA ACCTTGGCA GC-3’.

The amplified DNA was subjected to Sanger sequencing. The sequencing primer sequence was Emb-F: TCCCAGCAACTAACTGCATGG. Biallelic peaks indicated a genotype of Emb+/-, a single peak without any locus deletion represented a genotype of Emb+/+, and a single peak with a locus deletion indicated a genotype of Emb-/-.

Immunofluorescence staining of embryonic mouse colon

Whole embryos at E12.5, E14.5, and E16.5 were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin and sectioned for staining. Immunofluorescence staining of the sections were performed as previously described to track the development of ENS by using Tuj1 (ab78078, Abcam, UK). Colons from neonatal mice at 1, 2, or 6 weeks of age were dissected, rolled, and processed through fixation, embedding, and sectioning. Antibody Tuj1 (ab78078, Abcam, UK) was used to label enteric neurons. Embryonic gut tissues were isolated from the hindgut of E13.5d mouse. At this developmental stage, ENCCs migrate between the cecal region and the distal end of the hindgut [17]. Following isolation, successive tissue sections were prepared. Successive tissue sections were stained using the Six-color multiple immunofluorescence Kit (RC0086-56RM, Recordbio Biological Technology, China), which operates on tyramide signal amplification (TSA) technology, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibody p75NTR (ab52987, Abcam, UK) and anti-NESTIN (ab81462, Abcam, UK) were employed for labeling ENCCs [17]; Antibody E-cadherin (20,874-1-AP, Proteintech, USA) and anti-CK18 (66,187-1-Ig, Proteintech, USA) were utilized for labeling intestinal epithelial cells [54]; Antibody LGR5 (30,007-1-AP, Proteintech, USA) was employed for labeling intestinal epithelial stem cells (ISCs) [55]; Antibody α-SMA (55,135-1-AP, Proteintech, USA) was used for labeling smooth muscle cells [21, 56].

RNA sequencing in dissociated ENCCs

E14.5d fetal guts were dissected out and the ENCCs were isolated [57]. Immediately after cell sorting, HNK1 (CD57) and p75NTR (CD271) double-positive ENCCs were lysed using the SMART-seq II protocol for RNA sequencing [17, 58, 59]. Differentially expressed genes were listed in Additional file 1: Dataset S2 with a filter of |log2 (FoldChange)|> 1 & p.adj < 0.05. The GO and the KEGG analyses were performed [52, 53].

BrdU assay of ENCCs

Newborn mice at the day 2 were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (B5002, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in the amount of 50 μg/g. After 2 h of incubation, 0.5 cm colon tissue (0.5 cm from the anus) was harvested, fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were prepared, and BrdU detection and immunofluorescence staining were then performed on cross-sections using an anti-BrdU antibody (66,241-1-lg, Proteintech, USA) and the secondary antibody CoraLite594-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse lgG(H + L) (SA00013-3, Proteintech, USA).

Culture of primary ENCCs

E14.5d fetal guts of wild type mice were dissected and digested in an enzyme mixture consisting of Dispase II (2 mg/mL, D4693, Sigma, USA), Collagenase IV (0.5 mg/mL, 40510ES60, Yeasen, China) and DNAse I (5 mg/mL, D4527-10KU, Sigma, USA) in DMEM/F-12, at 37 ℃ for 40 min with gentle mechanical trituration. Single-cell suspensions were then prepared by centrifugation and filtration through 350 μm strainer meshes. The suspensions were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with N2 (1%, 17,502,048, Gibco, USA), B27 (1%, 17,504,044, Gibco, USA), recombinant fibroblast growth factor-basic (bFGF, 10 ng/mL, 100-18B, PeproTech, USA), recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF, 10 ng/mL, AF-100-15, PeproTech, USA), 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μmol/L, 21,985,023, Gibco, USA), penicillin and streptomycin (1%, 15,140,122, Gibco, USA). The cells were seeded into culture flasks at a density of 5.0 × 106 cells/mL and then cultured for 7 days to allow the formation of floating multicellular aggregates. Then the neurospheres were collected and digested into single cells using trypsin (0.25%, G4002, Servicebio, China) at 37 ℃ for 3 min. The cultured ENCCs were validated by immunofluorescence staining using the following antibodies: p75NTR (ab52987, Abcam, UK), NESTIN (ab81462, Abcam, UK).

Generation of Emb knockout in cultured ENCCs

To knock out the Emb gene in cultured ENCCs, a Lenti-Cas9-sgRNA-EGFP lentivirus was designed and used to infect the neurospheres. The sgRNA (GCCATCATTTCTTCTCGAAC) was designed to target exon 2 of Emb.

Cell viability test

Gather suspended neurospheres and enzymatically disintegrate them into a single-cell suspension using 0.25% trypsin. Resuspend the cells in a serum-free culture medium and and count the cells of the cell population. Employ a 96-well plate to establish an experimental timeline comprising 6 distinct temporal intervals, specifically 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days. Each temporal point should be represented by 6 replicates, each well accommodating an approximately 2.5 × 103 cells. Prior to the experimental day, pretreat the plate by coating the plate for cell adhesion. Following cellular adhesion, introduce a serum-free culture medium supplemented with 10% CCK-8 solution. Include three blank wells as controls. Incubate the plate at a temperature of 37 °C for a duration of 3 h. At each time point, record the optical density at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax 190, MD, USA).

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was assessed using Millicell Hanging Cell Culture Inserts in a 24-well plate. A total of 200 μL of a single-cell suspension (1 × 105 cells/mL) in serum-free DMEM/F-12 was added to the upper chamber, while 600 μL DMEM/F-12 containing 10% fetal calf serum was placed in the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 48 h incubation, cells that migrated through the membrane and adhered to its lower surface were counted for comparison.

ENCC migration assay in explant guts

For the in vitro ENCC migration assay, E11.5d mouse guts from stomach to ileocecal junction were dissected and placed on a culture dish coated with 2.5% low melting agarose gel. Cutting end at the cecum was transferred to the 0.45 μm filter membrane (MCE, USA; Millipore, USA), and the proximal end was secured to the agarose bed with needles. The explant was maintained in culture with DMEM/F-12, 10% FBS, antibiotics and 100 ng/mL GDNF [60] (450-44-10UG, PeproTech, USA). After 48 h, the filter membranes were fixed with 4% PFA (50 min, 25 °C) and washed in PBS. Then the cultured explants together with the filter membrane were removed from the gel and blocked in PBS (1% of BSA; 0.15% glycine, and 0.1% triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 h at 25 ℃. Primary antibody incubation was performed at 4 ℃ overnight. Anti-Tuj1 (ab78078, Abcam, UK) and anti-Phox2b (ab183741, Abcam, UK) were applied and secondary antibody incubation with Goat anti-Mouse (ab150113, Abcam, UK), Donkey anti-Rabbit (ab150075, Abcam, UK) at for 2 h in 25 °C. After washing, explant with filter membrane were stained with anti-fade DAPI (0100-20, SouthernBiotech, USA).

Time lapse imaging of ENCC migration in vivo

For time lapse imaging, the Sox10-tdTomato+ mice were generated by crossing Sox10-iCreERT2 (The Jackson Laboratory, MGI:5,634,390) to Rosa26-tdTomato mice (The Jackson Laboratory, MGI:104,735) to visualize ENCCs [17, 61]. These mice were then crossed to the Emb knockouts. One day after administration of 4-hydroxytamoxifen in pregnant mice at E11.5d, the embryonic gut was dissected with surrounding tissues and screened for expression of fluorescent proteins using a stereo fluorescence microscope. The region of interest to be imaged was suspended across a ‘V’ cut in the 0.45 μm filter membrane (Millipore, USA) [62, 63]. The attached tissues were gently pressed into the filter and a steel ring was placed over the edges of the filter to prevent it from moving. The preparation was cultured in DMEM/F-12 containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a heated stage and imaged using an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM710, Germany). For time-lapse imaging, z-series images (15-40 partially overlapping slices) were obtained every 3-8 min for 10-18 h. The hardware was controlled by ZEN software (ver.2.3) and the data analyzed using Origin software (ver.2021b).

Cultivation of intestinal epithelial organoids (IEOs) and intestinal mesenchymal cells (IMCs)

Mice aged from E13.5d to E18.5d were prepared for the cultivation of IEOs and IMCs. The first 30% of the proximal portion of small intestine were isolated. The digestion solution for IEOs is Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (100-0485, STEMCELL, Canada); the culture medium for IEOs is prepared as follows: Advanced DMEM/F12 (12,634,010, Gibco, USA), Glutamax (1 × , 35,050,061, Gibco, USA), Hepes (0.01 M, 15,630,080, Gibco, USA), Pen/Strep (0.2 U/mL, 15,140,122, Gibco, USA), N2 supplement (1 × , 17,502,048, Gibco, USA), B27 supplement (1 × , 17,504,044, Gibco, USA), N-acetylcysteine (1.25 mM, 38,520-57-9, Sigma, USA), EGF (0.05 µg/mL, AF-100-15, PeproTech, USA), R-spondin1 (500 ng/mL, 315-32-20UG, Peprotech, USA) and Noggin (100 ng/mL, 250-38-20UG, Peprotech, USA). After digestion, resuspend the cells in Matrigel. Once the Matrigel has solidified, add the culture medium for IEOs. Subsequently, incubate the plate at 37 °C for cultivation in a cell incubator. Replace the culture medium for IEOs every 2 days and continue cultivation until day 6 for subsequent experiments [64].

To cultivate IMCs, the remaining 70% segment of small intestine and colon tissue was utilized. This tissue was placed in a dish with IMC digestion solution containing Dispase II (2 mg/mL, D4693, Sigma, USA), collagenase IV (0.5 mg/mL, 40510ES60, Yeasen, China), DNase I (5 mg/mL, D4527-10KU, Sigma, USA) and DMEM basic culture medium (8,122,483, Gibco, USA). Tissue was digested in a 37 °C incubator with gentle pipetting every 8 min, repeated 2-3 times. Subsequently, the obtained cells were resuspended in DMEM medium and cultured. After 24 h, non-adherent cells were removed, leaving behind adherent cells with a fibroblast-like appearance. Cultivation continued until day 6 [65].

Co-culture of fetal mouse IEOs, IMCs, and ENCCs

To prepare the induction medium, retinoic acid (302-79-4, 2 μM, MedChemExpress, USA) was added to the IEO culture medium [66]. Adherent IMCs were digested with 1 mL of trypsin for 2 min, and digestion was stopped by adding 1 mL of basal medium. Cells were then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 200 μL of induction medium at a final concentration of 10,000 cells. Neural spheres containing ENCCs were similarly processed: enzymatic dissociation, neutralization, centrifugation, and resuspension in 200 μL of induction medium, adjusted to 10,000 cells. For co-culture, approximately 30 fetal IEOs per well were used. After removing the supernatant, mixed IMC and ENCC suspensions were added and incubated with the organoids for 4 h. Whole mount staining was performed using anti-Tuj1 (ab78078, Abcam, UK) and Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated secondary antibody (A-11001, Invitrogen, USA) to assess ENCC integration into IEOs.

Immunofluorescence staining of IEOs and IMCs

Utilizing the Four-color multiple immunofluorescence Kit (RC0086-34RM, Recordbio Biological Technology, China), which operates on tyramide signal amplification (TSA) technology, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Collected the IEOs and IMCs. Immunofluorescent staining was performed using the anti-CD90 (84,180-1-RR, Proteintech, USA), anti-CD73(12,231-1-AP, Proteintech, USA) and anti-CD105 (84,807-4-RR, Proteintech, USA) to label IMCs, Antibody E-cadherin (20,874-1-AP, Proteintech, USA), anti-CK18 (66,187-1-Ig, Proteintech, USA) and anti-ZO-1 (66,452-1-Ig, Proteintech, USA) were used to label IEOs.

Transfection

Dilute the Lipofectamine™ 3000 (L3000015, Invitrogen, USA) and plasmid DNA in Opti-MEM Medium (51,985,034, Gibco, USA). Besides, mix them together gently and incubate at room temperature for 15 min. Add DNA-lipid complex to the cell culture flask (Corning) with 70-90% confluent. Extract protein after 24 h which would be cryopreserved at −80 ℃ for further research.

The lentiviral transduction experiments aimed at targeting RET and EMB utilized specific shRNA sequences: “CGAGGAAATGTACCGTCTGAT” for Ret and “TTTCCTTAAAGAGCTGTAATAT” for Emb. The experiments were conducted using N-2a cells as the cellular model.

IP-LC-MS/MS

Detection of the interacting protein of EMB was performed by immunoprecipitation coupled to tandem liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (IP-LC–MS/MS). N-2a cell line expressing Flag-EMB was constructed by transfection. The cells were added to 100 μL of lysis solution. The lysates were stored at −80℃ for further assays.

Resuspend the Dynabeads and transfer 50 μL to a tube. Place the tube on the magnet for magnetic separation and discard the supernatant. Add 200 μL diluted tag antibody (anti-Flag, ab205606, Abcam, UK) and incubate at room temperature for 10 min. After that, the supernatant was discarded and Dynabeads were washed with binding buffer. Then the protein lysates were mixed with the Dynabeads and incubated at 4 ℃ for 2 h. Wash the beads 3 times and add 20 μL elution buffer for 2 min incubation at room temperature. The supernatant was dissolved in 100 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and separated. Furthermore, 5 μL 200 mM DTT and 10 µL 200 mM iodoacetamide were added successively to the supernatant and incubated at room temperature for 1 h each. 0.1 µg/µL trypsin was added for overnight digestion at 37 ℃. 1 µL 100% Trifluoroacetic acid was mixed with the sample and 10,000 g 5 min centrifugation was followed. The supernatant was collected for 2 h vacuum centrifugation. 50 µL of 0.1% formic acid was added to the dried sample. Finally, the samples were submitted for LC–MS/MS.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Thirty microliters of Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (HY-K0202, MedChemExpress, USA) were gently washed using a magnetic stand for three times. The antibody was diluted to the appropriate concentration and 400 μL was added to the prepared beads. The tube was rotated at 4 ℃ overnight. Perform magnetic separation and wash for four times. Then, add protein samples and gently pipette to resuspend the beads. Incubate at 4 ℃ with rotation overnight. Separate the beads from the supernatant and wash magnetic beads five times. Add 50 μL SDS-PAGE loading buffer and incubate at 98 ℃ for 10 min. Perform magnetic separation and the final sample was used for Western blots. Synthetic plasmids were constructed based on the coding sequence (CDS) region of the EMB and RET genes, with HA and 3 × FLAG tags, respectively. HA-EMB and 3 × FLAG-RET plasmids were co-transfected into HEK 293 T cells, and total protein was collected after 48 h for Co-IP assay. Synthetic plasmids of human and murine EMB gene were constructed based on the coding sequence (CDS) region with 3 × FLAG tags. Meanwhile, synthetic plasmid of murine PPP2CA was also constructed with HA tags. The plasmids were co-transfected into HEK 293T or N-2a cells, respectively, and total protein was collected after 48 h for Co-IP assay.

Western blot

The relevant primary antibodies used are as follows: anti-EMB (ab127692, Abcam, UK), anti-RET (ab134100, Abcam, UK), anti-PI3K (13,666, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), anti-P-PI3K (4228, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), anti-PPP2CA (A6702, abclonal, USA), anti-p-PPP2CA (AP0927, abclonal, USA), ACTIN (66,009-1-Ig, Proteintech, USA), GAPDH (60,004-1-Ig, Proteintech, USA).

Phosphatase enzyme activity assay

Phosphatase reaction was conducted in 50 μL reactions at room temperature for 15 min. The phosphate substance was detected by malachite green dye as the optical density at 630 nm (Serine/Threonine Phosphatase Assay System, Promega).

Whole-mount staining of N-2a and 293T cells

Cells grown on coverslips (N-2a and 293T) were collected. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using anti-EMB (ab127692, Abcam, UK) and anti-PPP2CA (A6702, abclonal, USA) to examine the colocalization of EMB and PPP2CA. Colocalization was quantified using ImageJ software (ver.1.8.0) [67].

HSCR cohort and sample collection

Patients with HSCR and healthy controls were recruited from Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The discovery cohort consisted of 107 unrelated HSCR patients and 120 ethnically matched healthy controls without a personal or family history of HSCR or other congenital intestinal diseases. The replication cohort included an additional 107 unrelated HSCR patients, with population-level controls derived from the gnomAD East Asian (gnomAD-EAS) database (n = 8,624). For combined analyses, a total of 214 HSCR patients were compared against both the 120 local healthy controls and the gnomAD-EAS dataset. Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for HSCR, confirmed by postoperative pathological examination showing the absence of enteric ganglion cells; (2) no confirmed cases of HSCR in the patient’s direct or collateral relatives. Exclusion criteria included cases with incomplete or unclear clinical information. Clinical details, including sex, HSCR subtype, and associated congenital malformations, were systematically recorded (Additional file 1: Dataset S3) [49]. Sanger sequencing of all nine EMB exons was performed on cDNA extracted from peripheral blood in both the discovery and replication cohorts [46].

Identify rare variants of EMB in HSCR patients

For Sanger sequencing, primers targeting all nine exons of EMB were designed and are provided in Additional file 1: Dataset S4. We assessed the mutation sites in EMB by Chromas (ver.2.6.6) and filtered rare variants based on the following criteria: loss of function mutations or missense variants, with an allele frequency of < 0.01 in both the 1000 Genomes Project [68] and 120 control samples. For the replication cohort, we recruited additional 107 HSCR patients from Tongji hospital, and Sanger sequencing of all nine exons of EMB was performed again. The 8,744 individuals of gnomAD-EAS were used as controls [69]. According to the rare variants (Loss of function mutations or missense variants, allele frequency < 0.01, 1000 genome project [68] and 120 control samples) detected in the discovery and replication cohorts, a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was performed by SPSS (ver.26) to show the difference of rare variants of EMB between HSCR patients and controls. Sanger sequencing is considered the definitive method for SNP analysis in clinical molecular laboratories. Notably, whole exome sequencing (WES) data demonstrated a significant concordance rate of 99.97% with SNVs identified through Sanger sequencing [70]. Therefore, we conducted a correlation analysis between our Sanger sequencing results and data from gnomAD-EAS.

Statistics

All statistical data presented in bar graphs are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests in SPSS Statistics (ver. 26). For comparisons involving three or more groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests was conducted using the same software. Sample sizes (N) are indicated in the figure legends.

Results

Identification of EMB as a potential regulator of ENS development

We examined the expression pattern of EMB in the gut. We first analyzed scRNA-seq data in human post-conceptional week (pcw) 8-10 fetal intestine. EMB was expressed in ENCCs and different enteric neural cells (Additional file 2: Fig.S1 A and B) and epithelial cells (Additional file 2: Fig.S1 C and D), but hardly in mesenchymal cells (Additional file 2: Fig.S1 E and F). We confirmed that EMB protein was expressed in ENCCs and enteric neurons in human colon by H&E and immunofluorescence staining (Additional file 2: Fig.S1 G-N). Similarly, we showed that mouse EMB is expressed in ENCCs and enteric neurons using scRNA-seq data and immunofluorescence staining (Additional file 2: Fig.S2 A-F). To explore the potential function of EMB in ENS development, we first turned to zebrafish, a simple model system. We designed a translational blocking morpholino to knock down emb expression, used a morpholino targeting ret as a positive control, and employed mismatch morpholinos as negative controls (Additional file 2: Fig.S3 A-D). Upon emb or ret knockdown, the number of enteric neurons was significantly reduced, suggesting that Emb was required for the ENS development (Additional file 2: Fig.S3 E-J).

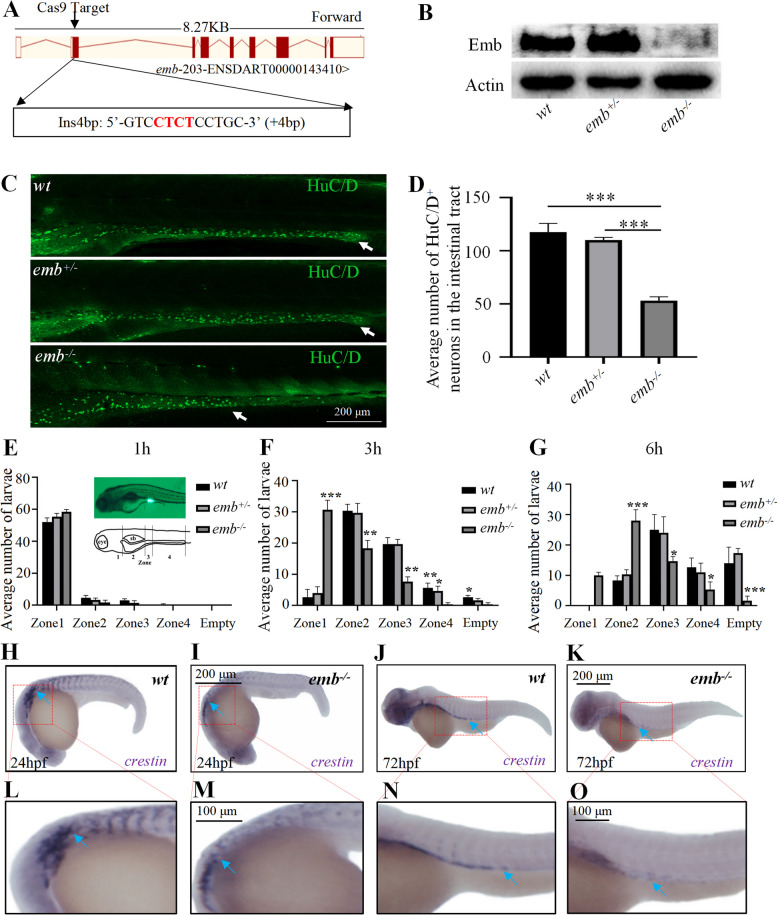

Emb is required for ENS development in zebrafish

To further validate the role of emb during zebrafish ENS development, we generated an emb knockout allele using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. A 4-bp insertion was induced in the second exon of emb, which caused a frame-shift in its mRNA and disruption of its protein translation (Fig. 1 A and B; Additional file 2: Fig.S3 K-M). Approximately 80% of emb-/- larvae died during development, and most of the death happened during 7–15 dpf, shortly after feeding, suggesting that the disrupted intestinal function might be responsible for the lethality (Additional file 2: Fig.S3 N). Indeed, upon emb knockout, the number of enteric neurons was significantly reduced, especially in the distal part of the intestinal tract (Fig. 1 C and D). Next, we performed a transit assay to examine the intestinal motility in emb mutants. The results showed that loss of emb led to significantly delayed clearance of the fluorescence indicator, indicating that emb is essential for zebrafish intestinal motility (Fig. 1 E-G; Additional file 2: Fig.S3 O). Since enteric neurons are derived from neural crest cells (NCCs), we then tracked the development of NCCs by examining crestin mRNA expression. The expression level of crestin was reduced in emb-/- embryos at both 24 h and 72 h (Fig. 1 H-O). Moreover, the migration of NCCs towards the posterior was significantly attenuated in emb-/- embryos, indicating emb is potentially required for both the proliferation and migration of the NCCs. In summary, emb is required for the development and function of the ENS in zebrafish.

Fig. 1.

Loss of emb causes ENS defects in zebrafish. A, Generation of targeted emb mutant in Zebrafish. A 4 bp insertion in Exon 2 was introduced through the CRISPR/Cas9 system. B, Expression of the Emb protein is disrupted in different genotypes determined by western blots. C, The enteric neurons at 5 dpf zebrafish larva of wild type (wt), heterozygous and homozygous emb mutants are labeled by HuC/D and white arrows point to the most posterior margin where the enteric neurons migrated to. D, Quantification of the numbers of HuC/D positive cells in the intestinal tract, ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 10 for each group. E-G, Quantification of the number of larvae in each group based on the anterior extent of tracer. “empty” means fluorescent tracers are completely evacuated in the intestine. Statistical significances compared to wt are labeled on top of each bar, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 60. H-K, Lateral view of in situ hybridization results of 24 hpf and 72 hpf larvae using crestin probe, blue arrows point to migrating neural crest cells. L-O, Locally enlarged images of the H–K images (Red dashed box)

Knockout of Emb causes HSCR-like phenotypes in mice

To determine whether EMB is required for ENS development across different species, we then examined its function in mice. Similarly, we generated Emb knockout mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. We isolated a knockout allele with a 13 bp deletion in exon 3, which led to mRNA decay and total abolishment of its protein expression (Fig. 2 A-D, Additional file 2: Fig.S4 A). We performed H&E staining of the ganglionic segments of colon at E17.5d and P1d, and observed no obvious morphological or structural defects in Emb mutants (Additional file 2: Fig.S4 B and C). However, in three mating scenarios, the numbers of Emb-/- newborns were all much less than expected according to Mendel’s laws (Fig. 2 E), indicating that ~ 70% of the Emb-/- embryos died during fetal development, in agreement with the observations in zebrafish. Strikingly, we observed that the distal colon of Emb-/- mice was enlarged, and that the colorectum was filled with dry stools when we opened up the abdomen and further dissected out the colorectum (Fig. 2 F and G). We then examined the migration and colonization of ENCCs at various stages (E12.5d, E14.5d, E16.5d, 1 week, 2 weeks and 6 weeks post birth), and found that the number of enteric neurons was significantly reduced and the length of the aganglionic segments was significantly longer in Emb-/- mice compared to wild type controls or heterozygous mutants (Fig. 2 H, Additional file 2: Fig.S5 A-G). Taken together, these data show that Emb is critical for the ENS development in mice.

Fig. 2.

Loss of Emb causes HSCR-like phenotypes in mice. A, Using CRISPR/Cas9 system, a 13-bp frameshift deletion in exon 3 of Emb was induced. B, Emb mRNA expression is diminished in Emb-/- mice determined by quantitative real-time PCR. C, The EMB protein expression levels in different genotypes were determined by Western blotting, and the expression levels were quantified in (D). E, The percentage of each genotype in three different crossing scenarios. ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 3. F, Abdominal anatomy of wild type, Emb+/- and Emb-/- mice. G, Isolated colorectal from the distal rectum to the ileocecal part, note the dry stool filled and dilated colon of the Emb-/- mice. H, Immunofluorescence staining of 6-week mouse colons; the entire colon is rolled into a donut-like shape along the longitudinal axis, and then embedded and processed into paraffin sections; the right panels are zoom-ins of the distal colon. Green, Tuj1; blue, DAPI. The red arrows indicate the enteric neurons farthest from the proximal colon, and the distance from the"red arrow"to the distal colon represents the aganglionic segment; PC, proximal colon; DC, distal colon; Quantification results are presented in Additional file 2: Fig.S5 G. I, Immunofluorescence staining of the cross sections of 2-day neonatal mouse colons. Red, Brdu; green, Tuj1; blue, DAPI. Quantification results are presented in Additional file 2: Fig.S5 H

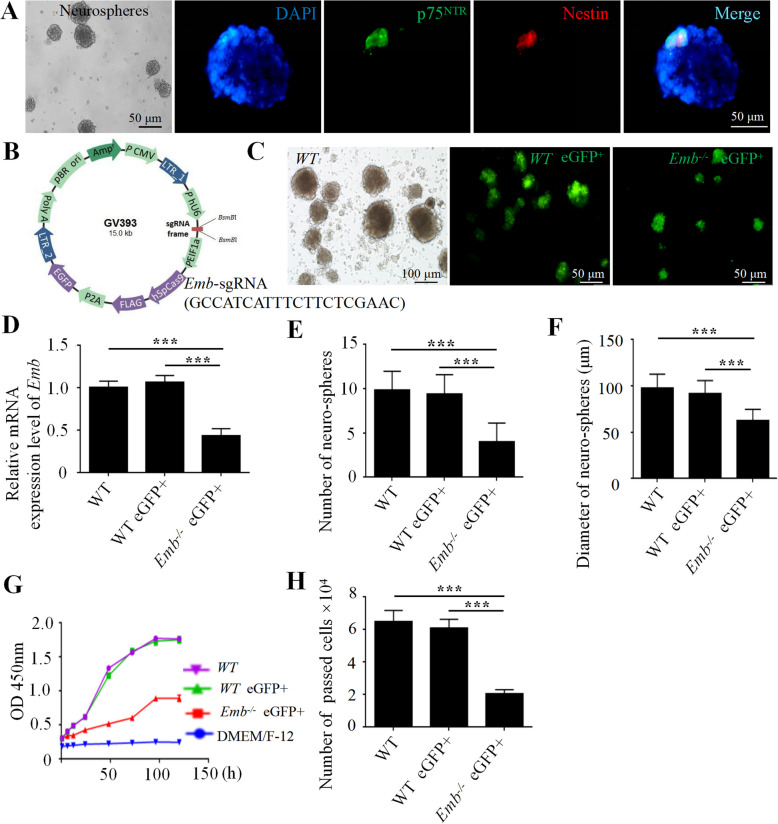

Emb is required for the proliferation and migration of the ENCCs

Since enteric neurons originated from ENCCs, we sought out to determine the function of Emb in the ENCCs. In 2-day neonatal mice, we noticed that the number of Brdu and Tuj1 double labeled cells was significantly reduced in Emb-/-, indicating that Emb is required for the proliferation of ENCCs (Fig. 2 I, Additional file 2: Fig.S5 H). Since we used full-body Emb knockout mice, we were unable to determine whether Emb functions in the ENCCs or in the colon environment. Therefore, we utilized an in vitro primary culture system to isolate ENCCs from E14.5 fetal guts (Fig. 3 A). In the cultured ENCCs, we used a lentiviral infection and CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing to generate Emb knockout line (Fig. 3 B-D). Compared to controls, Emb-/- ENCCs formed fewer neurospheres with reduced diameters (Fig. 3 E and F). The growth rate of dissociated Emb-/- ENCCs was significantly decreased as determined in the CCK8 assay, indicating defects in cell proliferation (Fig. 3 G). Moreover, these cells exhibited impaired migration abilities in the transwell assay (Fig. 3 H). These data indicate that Emb is required for both the proliferation and migration of ENCCs.

Fig. 3.

EMB is required for ENCC proliferation and migration in vitro. A, Isolated and cultured ENCCs identified by immunofluorescence double labeling of p75 (green) and Nestin (red), the nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). B, Schematic overview of the lentiviral construct used for Emb gene knockout in ENCCs. C, Lentivirus infection is confirmed by GFP fluorescence at day 6. D, Relative mRNA expression level of Emb in neurospheres. E, Numbers of the neurospheres are reduced upon knockout of Emb. F, Average diameter of the neurospheres is reduced upon knockout of Emb. G, Cell growth curve in the proliferation assay showing that loss of Emb affects ENCC proliferation. H, The migration ability, accessed by numbers of cells passed the matrix in the transwell assay, is affected by loss of Emb. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 6

We further examined the migration abilities of Emb-/- ENCCs in an explant mouse gut system, which closely reflected the properties of these cells in physiological conditions (Fig. 4 A). The density of ENCCs behind the leading ENCCs was not significantly affected (Fig. 4 B and C). In the explant of the proximal gut, fewer ENCCs migrated out of the gut of Emb-/- mice compared to controls, and both the average and maximal migration distance from the explant was significantly reduced (Fig. 4 D-G). Moreover, the marked aggregation of neural fibers arisen from Emb-/- ENCCs showed more random protrusions (Fig. 4 D). These data confirmed that Emb is required for the migration of ENCCs. Next, we generated transgenic mice with ENCCs labeled by genetically encoded tdTomato and performed time-lapse imaging to visualize the migration of ENCCs in cultured E12.5d hindgut tissue (Additional file 3: Movie S1 and Additional file 4: Movie S2). Most of the wild type ENCC trajectories were from rostral to caudal in controls, whereas oppositely directed trajectories were observed frequently in Emb-/- ENCCs (Fig. 4 H and I). Accordingly, the average net speed of Emb-/- ENCCs moving towards caudal was significantly reduced compared to wild type controls (Fig. 4 J). In summary, loss of Emb leads to disruption of both the proliferation and migration of ENCCs in mice.

Fig. 4.

Emb is required for the migration of the ENCCs in gut explant. A, Schematic illustrating the ENCC migration assay in mouse gut explants. B Using the transgenic mice with ENCCs labeled by genetically encoded tdTomato, and the ENCCs were marked by Sox10 (red) in E12.5d mice. C, Relative density of ENCCs behind the leading ENCCs, NS, non-significance, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 4. D, Representative images of the in vitro ENCC migration assay, ENCCs are labeled with P75NTR (red) and Sox10 (green). E, Quantification methods of the in vitro migration assay, the membranes were divided into five regions based on the distance from the margin of the explant and the numbers of Sox10 positive cells in each region were counted and quantified. F and G, Mean migration distance of Sox10+ cells and migration distance of the furthest migrating Sox10+ cell in different groups; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 3. H and I, Polar histograms representing the trajectories of the cells which were 150 μm from the most caudal cell at 40-min intervals in WT (H) and Emb-/- explants of E12.5d hindgut (I). The trajectories are determined by drawing a straight line from the position of cell to its position 40 min previously, with the 0 degree as the rostrocaudal axis of the gut (27 cells were examined). J, Quantification of the average net speed by measuring the distance between the location of the wave front at the beginning of the time lapse sequence and its location at the end of the sequence. ***, p < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s T test, N = 3

To determine whether EMB functions in ENCCs or in the intestinal environment in regulating ENCC migration, we used an organoid system. We cultured the IEOs and IMCs originated from both WT and Emb-/- mice and validated the cell types with immunofluorescence staining (Additional file 2: Fig.S6 A-D). We then co-cultured IEOs, the IMCs and the isolated ENCCs labeled by tdTomato. In the co-cultured system of wild type organoid and cells, the ENCCs were able to migrate into the IEOs after 4 h (Additional file 2: Fig.S6 E). We then substituted the IEOs, the IMCs or the ENCCs with Emb mutants, and examined the migration of the ENCCs. Loss of EMB in IEOs or IMCs did not affect the migration of wild type ENCCs (Additional file 2: Fig.S6 F and G). However, loss of EMB in ENCCs significantly attenuated their migration (Additional file 2: Fig.S6 H and I). These data indicate EMB functions in a cell-autonomous manner in regulating ENCC migration.

EMB functions through the PI3K pathway

To investigate the molecular mechanisms through which EMB regulates ENS development, we performed RNA-sequencing–based transcriptome analysis on the dissected gut of zebrafish larvae and the isolated ENCCs from E14.5d mouse fetal guts. We then performed enrichment analyses to identify genes and pathways that are significantly affected (Additional file 2: Fig.S7). We observed that several players in the PI3K signaling pathway, which has been previously associated with the proliferation and migration of ENCCs [71, 72], were down-regulated by loss of Emb in both zebrafish and mice. Considering the well-established role of PI3K-AKT signaling in ENS development, we hypothesized that EMB may function via the PI3K pathway in ENCCs. We subsequently tested this hypothesis in the Neuro-2a (N-2a) cells [73]. Knockout of Emb led to a significant reduction in both the p-PI3K and p-AKT levels, indicating that activation of the PI3K pathway is impaired (Additional file 2: Fig.S8 A and B). Knockout of Emb largely attenuated the migration ability of N-2a cells as determined by the transwell assay, which could be partially restored by the application of PI3K agonist 740-Y-P or AKT agonist SC79, suggesting that Emb regulates cell migration through PI3K pathway (Additional file 2: Fig.S8 C and D). Moreover, the two agonists were also able to rescue the proliferation defects caused by knockout of Emb (Additional file 2: Fig.S8 E). Since it has been reported that RET also functions through the PI3K pathway, we performed an epistatic experiment to determine whether there are interactions between EMB and RET. We designed shRNAs for both EMB and RET, and validated the knockdown efficiency by RT-qPCR and Western blots (Additional file 2: Fig.S9 A-I). We then examined the p-PI3K levels upon knockdown of EMB, RET or EMB and RET (Additional file 2: Fig.S9 J and K). The results show that EMB and RET regulate PI3K pathway independently. Moreover, we detected no obvious interaction between EMB and RET in a co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay (Additional file 2: Fig.S9 L-N).

We then examined whether EMB functions through PI3K pathway in vivo. We first determined that the 740-Y-P and SC79 could also activate the PI3K pathway in zebrafish larvae (Fig. 5 A-C). Similar to the results generated in cell cultures, both the p-PI3K and p-AKT levels were significantly reduced in emb-/- (Fig. 5 D-F). Furthermore, upregulation of PI3K pathway activity in emb mutants using 740-Y-P and SC79 was able not only to restore the corresponding protein phosphorylation levels but also to increase the numbers of enteric neurons in the distal intestinal tract (Fig. 5 G-J). Therefore, we concluded that EMB functions through the PI3K pathway in regulating ENS development.

Fig. 5.

Emb regulates ENS development through the activation of PI3K pathway in zebrafish. A-C, Validation of the efficiency of the PI3K/AKT agonists (740-Y-P and SC79) in wild type zebrafish. D, Western blots of total and phosphorylated PI3K and AKT of 5 dpf zebrafish larvae, before and after exposure of agonists, the protein levels are quantified in (E and F). Representative images of immunofluorescence staining to assess the number of enteric neurons (G, HuC/D) and the levels of cell proliferation (H, p-H3). In Figure G, the dashed box in the left panel marks the most distal enteric neurons positive for HuC/D; the right panel shows a magnified view of the boxed region. In Figure H, the dashed box in the left panel indicates a representative region with high PH3 expression; the right panel shows a magnified view of the boxed region. The quantification results are presented in I and J. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc, N = 10

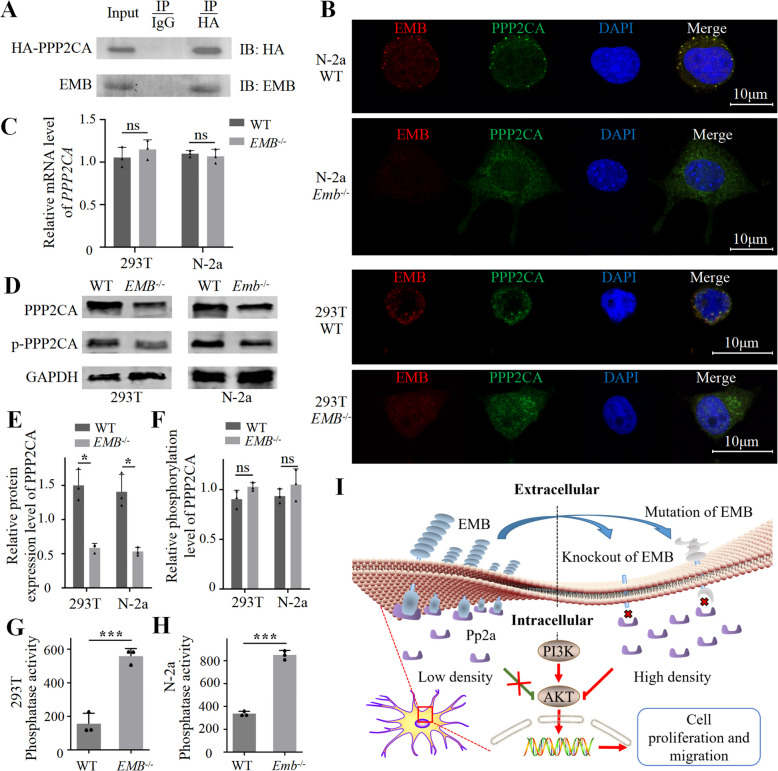

EMB positively regulates PI3K signaling by recruiting PP2A to the cell membrane

To reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying EMB function, we conducted IP-LC-MS/MS to identify the binding partners of EMB (Additional file 1: Dataset S5). We then scanned the target list for potential links to the PI3K pathway. We noticed that, PPP2CA, which is the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2 A (PP2A), potentially interact with EMB. We confirmed the interaction between EMB and PPP2CA by Co-IP (Fig. 6 A, Additional file 2: Fig.S10 A-E). Moreover, in the N-2a or 293 T cells, EMB and PPP2CA co-localized in the cell membrane (Fig. 6 B). Next, we examined whether knockout of EMB affects PPP2CA. The mRNA expression level of PPP2CA was not affected by the expression of EMB (Fig. 6 C and Additional file 2: Fig.S10 F-G). However, upon EMB loss, membrane-localized PPP2CA decreased, whereas intracellular PPP2CA increased (Fig. 6 B and Additional file 2: Fig.S10 H), which was verified by the result of western blots of membrane-associated protein (Fig. 6 D-F). The relative phosphorylated level of PPP2CA was not changed (Fig. 6 D-F). Finally, we performed the Serine/Threonine Phosphatase assay and observed that the phosphatase activity of PP2A enzymes was significantly increased in the cytoplasmic extracts of EMB-/- cells (Fig. 6 G-H). Combined with the observation that the levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT were reduced upon EMB knockout, we proposed that EMB could recruit PP2A complex to cell membrane to reduce its activity, and loss of EMB could cause release of PP2A to the cytoplasm and inactivation of PI3K signaling via decreasing the phosphorylation levels of PI3K and AKT (Fig. 6 I).

Fig. 6.

EMB activates PI3K pathway by recruiting PP2A to the cell membrane. A, Co-IP between EMB and PPP2CA in N-2a cells. B, Immunofluorescence staining of EMB (red) and PPP2CA (green) in WT or Emb-/- N-2a or 293 T cells. The yellow puncta indicate co-localization (C), Ppp2ca mRNA expression levels determined by RT-qPCR. D, Upon fractionation, western blots of total and phosphorylated membrane-associated Ppp2ca in 293 T or N-2a cells. E and F, Quantification of the protein levels in panel D. G and H, The Serine/threonine phosphatase activities of PP2A enzymes in the cytoplasmic fraction. ns, not significance; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. I, A working model of EMB function in PI3K signaling

Rare variants of EMB potentially contribute to HSCR in humans

In humans, defects in ENS development would cause various types of diseases including HSCR. To explore and identify whether variants in EMB participate in the pathology of HSCR, we performed Sanger sequencing of all the nine exon regions of EMB in two HSCR cohorts consisting of 214 patients (Additional file 5: Tables S1 and S2). In the discovery cohort, we identified only 6 rare variants (allele frequency < 0.01 in the 1000 Genomes Project [58] and our controls) in 8 patients, all of whom were diagnosed with S-HSCR. (Additional file 5: Table S3, Additional file 2: Fig.S11 A-I). In 120 controls, we only identified 1 rare variant of EMB (Additional file 2: Fig.S11 J). We then performed a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, showing rare variants of EMB were significantly enriched in HSCR patients (Table 1). The significant enrichment was confirmed by a replication cohort of another 107 HSCR patients with gnomAD-EAS data used as controls (Table 1, Additional file 2: Fig.S11 K-P). To assess whether these variants affect EMB function, we ectopically expressed the variant form of Emb in the Emb-/- N-2a cells and zebrafish, and then we examined the migration abilities of them. The results showed that 4 of the 6 variant forms of EMB (c.877 + 2 T > G, R238S, S93C, A12V) failed to rescue the migration deficits of Emb-/- cells and emb mutant zebrafish, suggesting that these variants disrupted EMB function (Additional file 2: Fig.S12 A-D). Collectively, these data implicate that some rare variants of EMB may contribute to the pathology of HSCR in humans.

Table 1.

The enrichment difference of rare EMB variants between HSCR patients and controls

| Casea | Controla | p-valueb | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery cohort | HSCR | Controls | ||

| Subjects | 107 | 120 | ||

| EMBc | 9 (7.48) | 1 (0.83) | 7.70 × 10-3 | 10.45 (1.43-460.80) |

| Replication cohort | HSCR | gnomAD-EAS | ||

| Subjects | 107 | 8624 | ||

| EMB | 6 (5.61) | 70 (0.81) | 9.27 × 10-3 | 3.52 (1.26-8.00) |

| Combined cohorts | HSCR | Controls and gnomAD-EAS | ||

| Subjects | 214 | 8744 | ||

| EMBc | 15 (6.54) | 71 (0.81) | 3.51 × 10-4 | 3.01 (1.26-5.18) |

Statistical analyses (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) were performed separately for the discovery cohort, the replication cohort, and the combined cohort

aThe numbers indicate alleles with rare exon mutations, and percentages in parentheses show the frequency of mutation carriers in the cohort; data are presented as n or n (%)

bRaw p-value from a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test comparing alleles between cases and controls

cDuring the discovery stage, one patient harbored two rare deleterious EMB mutations (so the allele count is 9, while 8 patients carried the mutation); in the combined dataset, the allele count is 15, with 14 patients carrying the mutation

Discussion

The ENS is crucial for proper intestinal function, and the disruption of ENS development or function leads to various disorders. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the ENS development have not been fully understood. Here, in an effort to screen for novel genes involved in ENS development, we identified EMB as a candidate. Since there were no previously established animal models for the determination of EMB function regarding ENS development in vivo, we generated knockout alleles of EMB in zebrafish, mice as well as in cultured cell systems. Data obtained from different models agree with each other, which showed that EMB plays evolutionarily conserved roles in regulating the proliferation and migration of ENCCs. Moreover, we observed an enrichment of rare variants in HSCR patients. Our study establishes EMB as an evolutionarily conserved, intrinsic regulator of ENS development, functioning cell-autonomously within ENCCs to govern their proliferation and directed migration.

Embigin plays a critical role in embryonic development. Talvi et al. reported that embigin is highly expressed in the developing gut at E8.5d and E13.5d, indicating its involvement in early gastrointestinal development [40]. Moreover, embigin deficiency results in delayed lung maturation and elevated neonatal mortality in mice, highlighting its importance in vital organ development and postnatal survival. In our study, we also observed that the genotype distribution of neonatal mice (EMB+/+, EMB+/-, EMB-/-) deviated from Mendelian inheritance, which is consistent with the findings reported by Talvi et al. [40].

It has been well established that the GDNF/RET signaling is critical for many aspects of the ENS development, including the proliferation, maturation, migration and survival of the ENCCs [8, 74]. In general, GDNF binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor RET, which in turn activates MAPK and PI3K signaling cascade. Activation of the PI3K leads to phosphorylation of AKT, which positively regulates various downstream targets involved in promoting proliferation, survival, and migration of ENCCs [75]. Therefore, we proposed that EMB may function through the PI3K pathway during ENS development when we observed that PI3K signaling was affected in Emb mutants in the transcriptome analyses. Indeed, knockout of Emb caused decrease of the phosphorylation levels of both PI3K and AKT, and application of PI3K signaling agonists could rescue the Emb knockout phenotypes to some extent. Hence, the EMB-PI3K cascade could at least partially explain the ENS development defects caused by knockout of EMB. Interestingly, EMB has been implicated to be involved in the metastasis and invasion of different types of cancers [36, 37], and the PI3K/AKT signaling has been linked to cancer cell metastasis in numerous studies, suggesting that EMB may also function via regulating PI3K/AKT signaling in cancer cells [76].

PP2A is an essential and ubiquitously expressed serine threonine phosphatase, which regulates many critical cellular processes by dephosphorylating its targets, including the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade [77]. Here, our results implicated that EMB is involved in regulating the interactions between PP2A and PI3K/AKT. We show that EMB binds to PPP2CA, the catalytic subunit of PP2A. Since EMB is a membrane protein, in the presence of EMB, most of the Ppp2ca are localized in the membrane, resulting in lower levels of cytoplasmic PP2A and high levels of PI3K/AKT phosphorylation. In the absence of EMB, PPP2CA relocates to the cytoplasm, promoting dephosphorylation of PI3K/AKT and inactivation of the signaling cascade. This working model could explain the down-regulation of PI3K signaling in Emb mutants. Moreover, the mechanistic insight into spatial regulation of PI3K/AKT via PP2A recruitment offers a potential target for modulating this critical pathway. On a different note, it has been shown that embigin forms a protein complex with MCT1 with extensive interactions to facilitate MCT1 localization to the plasma membrane and to alter its substrate-binding affinity [78]. Although in different contexts, it appears that a common theme of the molecular function of EMB is to recruit other proteins to the cellular membrane.

The identification of significantly enriched rare EMB variants in HSCR patients, particularly the functional impairment demonstrated for variants like c.877 + 2 T > G, R238S, S93C, and A12V in the rescue assays, provides compelling evidence that EMB is a susceptibility gene for HSCR. However, several aspects warrant careful consideration. The effect size appears modest, with variants found in a small subset of patients (primarily S-HSCR in the discovery cohort), and the near absence of variants in controls suggests low population frequency but not necessarily high penetrance. This pattern positions EMB rare variants likely as low-to-moderate penetrance risk factors within the complex polygenic landscape of HSCR, rather than highly penetrant Mendelian causes like RET. The restriction of identified variants to S-HSCR patients in the discovery cohort, while requiring validation in larger studies, might suggest EMB dysfunction predisposes to less extensive aganglionosis. Future investigations should explore potential oligogenic interactions between EMB variants and mutations in established HSCR genes (e.g., RET, EDNRB) and assess their impact in larger, diverse patient cohorts, including those with L-HSCR and TCA.

Conclusions

In summary, we show that EMB is involved in ENS development by regulating the proliferation and migration of ENCCs. Mechanistically, EMB recruits PP2A to the cell membrane, thereby reducing the dephosphorylation activity in the cytoplasm, promoting the activation of PI3K signaling pathway.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Datasets S1–S5. This file contains five datasets (S1–S5) with original data tables.

Additional file 2: Figs. S1–S12. This file contains all supplementary figures together with their corresponding figure legends.

Additional file 3: Movie S1. This file shows the migration of ENCCs in cultured E12.5d hindgut tissue of wild type mouse.

Additional file 4: Movie S2. The migration of ENCCs in cultured E12.5d hindgut tissue of Emb mutant mouse.

Additional file 5: Tables S1–S3. This file contains all supplementary tables and provides detailed datasets and extended statistical analyses that support the findings described in the main manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- dpf

Day post-fertilization

- ENCCs

Enteric neural crest cells

- ENS

Enteric nervous system

- HSCR

Hirschsprung’s disease

- IEOs

Intestinal epithelial organoids

- IMCs

Intestinal mesenchymal cells

- L-HSCR

Long-segment HSCR

- pcw

Post-conceptional week

- NCCs

Neural crest cells

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA-sequencing

- S-HSCR

Short-segment HSCR

- TCA

Total colonic aganglionosis

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. J.X.F., B.X. and F.C. designed research; Z.L., D.D.ZS., X.Y.M., H.Y.Y., J.X. and Y.J.C. performed research; J.W., X.S.Y., Z.J.L., J.Y.Y., X.Y.C., C.Z.F., L.Y.W., X.F.C., W.C.D. and K.W. analyzed data; Z.Z.L., J.F.T., L.Y., W.B.T., Y.M.L., X.W.J., H.X.R., M.Y., Q.Y., X.L., Z.L.X., D.M.W., C.L.J., D.H.Y., X.J.W., T.Q.Z., J.X.Y., L.X., J.W., Q.W., B.Y.Z., D.W., K.C., H.D.M., B.W., J.H.Z., C.Y.W. and W.J.Z. contributed tissue samples/transgenic mice/new reagents/analytic tools; J.X.F., B.X., F.C., Z.L., D.D.ZS., X.Y.M., H.Y.Y., J.X. and Y.J.C. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work is supported by funding from National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071685), Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81721005), Clinical Research Pilot Project of Tongji Hospital (2019YBKY026), Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2020BCB008 and 2023BCB095), Science, Technology Innovation Base Platform (2020DCD006) and Project of Shenzhen San Ming (SZSM201812055) and Joint Funds for the innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province(2023Y9159).

Data availability

The raw RNA-seq data of zebrafish larval intestines and dissociated mouse ENCCs have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject ID PRJNA1062169. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1062169/) [79]. The basic clinical information is provided in Additional File 1: Dataset S3, and the Sanger sequencing results of EMB mutations are shown in Fig. S11.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols involving human sample collection in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Ethical approval number: 2020-S226, 2021-S033). All relevant parts of the research were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. Experiments about zebrafish or mice were approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (Ethical approval number: HZAUMO-2017-048).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhi Li, Didi Zhuansun, Xinyao Meng, Heying Yang, Jun Xiao and Yingjian Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Feng Chen, Email: cfeng3000@163.com.

Bo Xiong, Email: bxiong@hust.edu.cn.

Jiexiong Feng, Email: 2002tj0515@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Heuckeroth RO. Hirschsprung disease - integrating basic science and clinical medicine to improve outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(3):152–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(5):286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang T, Hou Y, Wang X, Wang L, Yi C, Wang C, et al. Direct Interaction of Sox10 With Cadherin-19 Mediates Early Sacral Neural Crest Cell Migration: Implications for Enteric Nervous System Development Defects. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):179-92.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou B, Feng C, Sun S, Chen X, Zhuansun D, Wang D, et al. Identification of signaling pathways that specify a subset of migrating enteric neural crest cells at the wavefront in mouse embryos. Dev Cell. 2024;59(13):1689-706.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landman KA, Simpson MJ, Newgreen DF. Mathematical and experimental insights into the development of the enteric nervous system and Hirschsprung’s disease. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49(4):277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obermayr F, Hotta R, Enomoto H, Young HM. Development and developmental disorders of the enteric nervous system. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(1):43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lake JI, Heuckeroth RO. Enteric nervous system development: migration, differentiation, and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305(1):G1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez MP, Silos-Santiago I, Frisén J, He B, Lira SA, Barbacid M. Renal agenesis and the absence of enteric neurons in mice lacking GDNF. Nature. 1996;382(6586):70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuchardt A, D’Agati V, Larsson-Blomberg L, Costantini F, Pachnis V. Defects in the kidney and enteric nervous system of mice lacking the tyrosine kinase receptor Ret. Nature. 1994;367(6461):380–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondurand N, Sham MH. The role of SOX10 during enteric nervous system development. Dev Biol. 2013;382(1):330–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradnock TJ, Knight M, Kenny S, Nair M, Walker GM. Hirschsprung’s disease in the UK and Ireland: incidence and anomalies. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(8):722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taguchi T, Obata S, Ieiri S. Current status of Hirschsprung’s disease: based on a nationwide survey of Japan. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33(4):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JE, Vanover MA, Saadai P, Stark RA, Stephenson JT, Hirose S. Epidemiology of Hirschsprung disease in California from 1995 to 2013. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(12):1299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niesler B, Kuerten S, Demir IE, Schäfer KH. Disorders of the enteric nervous system - a holistic view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(6):393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Workman MJ, Mahe MM, Trisno S, Poling HM, Watson CL, Sundaram N, et al. Engineered human pluripotent-stem-cell-derived intestinal tissues with a functional enteric nervous system. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L, Lee HO, Jordan CS, Cantrell VA, Southard-Smith EM, Shin MK. Spatiotemporal regulation of endothelin receptor-B by SOX10 in neural crest-derived enteric neuron precursors. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):732–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagy N, Goldstein AM. Enteric nervous system development: a crest cell’s journey from neural tube to colon. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;66:94–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montalva L, Cheng LS, Kapur R, Langer JC, Berrebi D, Kyrklund K, et al. Hirschsprung disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1): 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahrami A, Joodi M, Moetamani-Ahmadi M, Maftouh M, Hassanian SM, Ferns GA, et al. Genetic Background of Hirschsprung Disease: A Bridge Between Basic Science and Clinical Application. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(1):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyrklund K, Sloots CEJ, de Blaauw I, Bjørnland K, Rolle U, Cavalieri D, et al. ERNICA guidelines for the management of rectosigmoid Hirschsprung’s disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Meng X, Zhang H, Feng C, Wang B, Li N, et al. Intestinal proinflammatory macrophages induce a phenotypic switch in interstitial cells of Cajal. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(12):6443–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosain A, Frykman PK, Cowles RA, Horton J, Levitt M, Rothstein DH, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33(5):517–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilghman JM, Ling AY, Turner TN, Sosa MX, Krumm N, Chatterjee S, et al. Molecular genetic anatomy and risk profile of Hirschsprung’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang CS, Li P, Lai FP, Fu AX, Lau ST, So MT, et al. Identification of Genes Associated With Hirschsprung Disease, Based on Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis, and Potential Effects on Enteric Nervous System Development. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1908-22.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romeo G, Ronchetto P, Luo Y, Barone V, Seri M, Ceccherini I, et al. Point mutations affecting the tyrosine kinase domain of the RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung’s disease. Nature. 1994;367(6461):377–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosoda K, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Baynash AG, Cheung JC, Giaid A, et al. Targeted and natural (piebald-lethal) mutations of endothelin-B receptor gene produce megacolon associated with spotted coat color in mice. Cell. 1994;79(7):1267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baynash AG, Hosoda K, Giaid A, Richardson JA, Emoto N, Hammer RE, et al. Interaction of endothelin-3 with endothelin-B receptor is essential for development of epidermal melanocytes and enteric neurons. Cell. 1994;79(7):1277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomon R, Attié T, Pelet A, Bidaud C, Eng C, Amiel J, et al. Germline mutations of the RET ligand GDNF are not sufficient to cause Hirschsprung disease. Nat Genet. 1996;14(3):345–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Barceló M, Sham MH, Lui VC, Chen BL, Ott J, Tam PK. Association study of PHOX2B as a candidate gene for Hirschsprung’s disease. Gut. 2003;52(4):563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofstra RM, Valdenaire O, Arch E, Osinga J, Kroes H, Löffler BM, et al. A loss-of-function mutation in the endothelin-converting enzyme 1 (ECE-1) associated with Hirschsprung disease, cardiac defects, and autonomic dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(1):304–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Southard-Smith EM, Kos L, Pavan WJ. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat Genet. 1998;18(1):60–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van de Putte T, Maruhashi M, Francis A, Nelles L, Kondoh H, Huylebroeck D, et al. Mice lacking ZFHX1B, the gene that codes for Smad-interacting protein-1, reveal a role for multiple neural crest cell defects in the etiology of Hirschsprung disease-mental retardation syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(2):465–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Barcelo MM, Tang CS, Ngan ES, Lui VC, Chen Y, So MT, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies NRG1 as a susceptibility locus for Hirschsprung’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(8):2694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gui H, Schriemer D, Cheng WW, Chauhan RK, Antiňolo G, Berrios C, et al. Whole exome sequencing coupled with unbiased functional analysis reveals new Hirschsprung disease genes. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tam PKH, Tang CSM, Garcia-Barceló M-M. Genetics of Hirschsprung’s Disease. In: Puri P, editor. Hirschsprung’s Disease and Allied Disorders. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 121–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung DE, Kim JM, Kim C, Song SY. Embigin is overexpressed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and regulates cell motility through epithelial to mesenchymal transition via the TGF-β pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55(5):633–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruma IMW, Kinoshita R, Tomonobu N, Inoue Y, Kondo E, Yamauchi A, et al. Embigin promotes prostate cancer progression by S100A4-dependent and-independent mechanisms. Cancers (Basel). 2018. 10.3390/cancers10070239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sipilä K, Rognoni E, Jokinen J, Tewary M, Vietri Rudan M, Talvi S, et al. Embigin is a fibronectin receptor that affects sebaceous gland differentiation and metabolism. Dev Cell. 2022;57(12):1453-65.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lain E, Carnejac S, Escher P, Wilson MC, Lømo T, Gajendran N, et al. A novel role for embigin to promote sprouting of motor nerve terminals at the neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8930–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talvi S, Jokinen J, Sipilä K, Rappu P, Zhang FP, Poutanen M, et al. Embigin deficiency leads to delayed embryonic lung development and high neonatal mortality in mice. iScience. 2024;27(2): 108914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]