Abstract

Objective

To assess whether continuous infusion of β-lactam antibiotics improves clinical outcomes compared to intermittent infusion in adult patients with sepsis or septic shock.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion. Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase. Risk of bias was assessed using the RoB 2.0 tool, and the certainty of evidence was evaluated using GRADE.

Results

Eleven studies involving 9,166 patients were analyzed, comparing continuous versus intermittent infusion of β-lactams in sepsis or septic shock. There was no significant difference in overall mortality (RR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–1.01) or ICU mortality (RR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–1.01). Continuous infusion was associated with lower hospital mortality (RR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.85–0.99), higher survival at the end of the study (RR 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07), and higher clinical cure rate (RR 1.42; 95% CI: 1.12–1.80). No significant differences were observed in the length of stay in the ICU (MD 0.75 days; 95% CI: -1.17 to 2.68) or hospital stay (MD -2.51 days; 95% CI: -10.13 to 5.12), or in the adverse events (RR 0.82; 95% CI: 0.60–1.12).

Conclusion

Continuous infusion of β-lactams could reduce hospital mortality and increase the clinical cure rate in critically ill patients, although its effect on overall mortality, hospital stay, and adverse events remains uncertain. PROSPERO number: CRD42024613938.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-025-11504-2.

Keywords: Sepsis, Beta lactam antibiotics, Continuous infusion, Intermittent infusion

Introduction

Sepsis is characterized by life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection [1]. Despite advances in early diagnosis and treatment, sepsis persists as a significant cause of mortality worldwide [2]. Failure to promptly initiate appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with increased mortality; in contrast, early administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics could reduce mortality from 40 to 50% to 10–20% [3].

Beta-lactams are one of the main types of antibiotics initially administered to patients with sepsis [4]. Beta-lactam antibiotics exert antibacterial activity by inhibiting bacterial cell wall integrity [5]. The standard practice for infusion of beta-lactam antibiotics is intermittent administration. However, beta-lactams exhibit antibacterial activity that depends on the length of time their concentration is maintained above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [6]. Therefore, maintaining stable plasma concentrations above the target MIC for a longer time would be crucial to ensure optimal dosing [7]. Based on this feature, continuous infusion of beta-lactams has emerged as an alternative to intermittent infusion.

Continuous administration of beta-lactams may present logistical and clinical challenges, particularly in settings with limited resources or staff training [8]. However, in institutions where nursing staff are experienced in both techniques, these challenges may be minimized. The implementation of continuous infusion thus depends on the healthcare context rather than being inherently complex [9].

Although several studies have explored the therapeutic benefits of continuous infusion of beta-lactam antibiotics in patients with sepsis, the findings have been heterogeneous and, in many cases, contradictory. To date, only a limited number of meta-analyses have attempted to synthesize the available evidence, highlighting the need for more robust and up-to-date evaluations to guide clinical practice [9].

Beta-lactam antibiotics are frequently used in the treatment of sepsis, and the continuous infusion modality has been the subject of increasing interest as an alternative to intermittent administration [10]. Several studies have suggested potential clinical benefits of continuous infusion, particularly in optimizing antimicrobial exposure [11]. However, its widespread implementation in clinical practice remains limited, due to factors such as the stability of drugs in solution, the need for additional resources for administration, and the fear of favoring the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [10]. Given the emergence of new large-scale trials and the continuing debate regarding optimal β-lactam administration in sepsis and septic shock, a comprehensive synthesis of the available evidence is warranted. This meta-analysis aims to clarify the impact of infusion strategies on key clinical outcomes and inform decision-making in diverse clinical settings.

Materials and methods

Searches

Databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and EMBASE were used. Searches were performed from inception until June 2025, including key phrases, MESH (PubMed), and Emtree thesauri (Scopus, Embase). Finally, a search strategy was applied to each database (Supplemental Table 1). “Sepsis”, “Continuous infusion”, “Intermittent infusion”, “β-lactams” were the primary search phrases. There were no limitations on language or date of publication.

The reference lists of included articles and previous systematic reviews were manually screened to identify additional eligible trials.

Eligibility criteria

All studies that met the following criteria were included in this study: Randomized controlled trials conducted in hospital settings that enrolled adult patients with sepsis or septic shock, and that evaluated continuous infusion compared to intermittent infusion of β-lactams, acknowledging the overlap in these populations and their potential contribution to heterogeneity. Continuous infusion was defined as constant intravenous administration over a 24-hour period. Intermittent infusion was defined as intravenous administration of β-lactam antibiotics over 30 to 60 min. Conference abstracts were excluded due to insufficient methodological details and outcome data. Also, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, case reports, series, and editor letters were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality was defined as the number of deaths from any cause during the study period. Survival at study completion was defined as the proportion of patients alive at the end of the predefined follow-up period. The secondary outcomes included the length of ICU stay, measured as the average number of days spent in the ICU, and the length of hospital stay, recorded as the average duration from admission to discharge. The incidence of adverse events was evaluated by documenting the occurrence rates of medical complications related to the intervention. Other secondary outcomes included the number of ICU survivors and hospital survivors, the clinical cure rate, which indicated the resolution of symptoms or illness, hospital mortality, and ICU mortality.

Data extraction

After the electronic searches, the results were compiled in a single library, and duplicates were eliminated. The first screening step was then performed, evaluating the titles and abstracts and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to each result reviewed through the Rayyan platform. This process was conducted as a peer review and independently by the authors of the review (DT, HG, ETA).

The studies included after this phase were searched and analyzed in full text, followed by a new screening process to justify the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this process, the eligible studies were included in the systematic review, and data extraction began. In case of disagreement, a fourth review author (JJB) was consulted.

Data were extracted from each study individually and in a blinded manner using a pre-prepared Excel spreadsheet format. For each analysis, data were extracted on the author, year of publication, country, type of study, number of participants per intervention arm, selection criteria, description of intervention and control, and primary and secondary outcomes.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias (RoB) was independently assessed using the RoB 2.0 tool. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (JJB). RoB per domain and study was described as low, with some concerns, or high for RCTs.

Data synthesis

Random-effects models with the inverse variance method were used for all meta-analyses of the effects of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion on primary and secondary outcomes. The Paule-Mandel method was used to calculate the between-study tau² variance.

The effect measure of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion on dichotomous outcomes was described with relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjustments for null events in one or both arms of the RCTs were made using the continuity correction method. The Hartung-Knapp method was applied for meta-analyses with more than five studies, as was the case in this review. Statistical heterogeneity of effects among RCTs was described by the I² statistic, with values representing low (< 30%), moderate (30–60%), and high (> 60%) levels of heterogeneity. For sensitivity analysis, fixed effects and the Mantel-Haenszel method were used. The metabin function of the R 3.5.1 meta library (www.r-project.org) was used. A funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to evaluate publication bias.

GRADE assessment

The GRADE methodology assessed the certainty of evidence and the degree of the recommended intervention regarding all outcomes (Supplemental Table 2). GRADE, based on domains such as risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias, evaluated some of the criteria. The certainty of the evidence was determined by outcome and described in the summary of results (SoF) tables, created using the online software GRADEpro GDT.

This study was a systematic review with meta-analysis. The reference elements for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA-2020) informed this review (Supplemental Table 3). PROSPERO number: CRD42024613938.

Results

Selection of studies

A total of 659 new records were identified from four databases. After the removal of 236 duplicates, 423 records were screened. Of these, 400 were excluded based on title and abstract. Twenty-three full-text reports were assessed for eligibility; twelve were excluded (10 due to wrong study design, one due to publication type, and one protocol). Five new studies were included, adding to the six previously included studies (n = 8695 participants). Therefore, the final review comprised 11 reports (n = 9166), which were included in both qualitative and quantitative syntheses [7–17] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow chart. Flow chart of selection of studies

Characteristics of included studies

The included articles were published between 2013 and 2024 and conducted in various countries, including the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Australia, New Zealand, China, Germany, Belgium, France, Malaysia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Croatia, Italy, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Egypt and Russia. The studies’ methodological design consisted of multicenter, randomized, double-blind trials and randomized open-label studies. A total of 179 centers were included, with 9166 participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author(s) | Year of publication | Country/Region | Study design | Number of centers | Duration of follow-up | Inclusion period | Financing | Total number of participants | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Mean age (SD) | Distribution by sex | Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardema | 2020 | Netherlands | Randomized controlled single-centre study | 1 | 4 days | November 2015 and June 2016. |

Tertiary referral hospital in the Netherlands |

59 |

Patients aged ≥ 18 years. Treatment with cefotaxime. Anticipated mechanical ventilation for > 48 h and ICU stay of > 72 h. |

Inability to acquire written informed consent. Contraindication for cefotaxime. Use of renal replacement therapy or extracorporeal life support. |

Continuous: Median age 67.5 years (3.90). Intermittent: Median age 64.12 years (9.51). |

39 were male (66%) and 20 were female (34%), p > 0.05 | Medical (28.8%), surgical (33.9%), trauma (6.8%), neurological (10.2%), and other (20.3%). |

| Abdul-Aziz | 2016 | Malaysia |

Prospective randomized clinical trial, two centers and open |

2 | 29 days | April 2013 to July 2013 | International Islamic University of Malaysia, Research Endowment Grant. | 140 | Adult, severe sepsis in previous 48 h, indication for cefepime, meropenem, or p/t < 24 h, expected ICU stay greater than 48 h. | Renal replacement therapy, impaired hepatic function, palliative treatment, inadequate central venous catheter access, death deemed imminent | Continuous 53.25 (6.06), intermittent 55.25 (7.79) | Male, n(%) Intervention 46 (66). Control 50 (71) | Charlson comorbidity index. Intervention: 3 (1–5). Control 4 (2–6) |

| Chytra | 2012 | Czech Republic |

A randomized open-label controlled trial |

1 | Not reported | September 2007 and May 2010 |

ICU of Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine at Charles University teaching hospital in Plzen. |

240 |

Suffered, at admission or during the ICU stay, from severe Infections and received meropenem with predicted duration of treatment for at least 4 days |

Age < 18 years, pregnancy, acute or chronic renal failure, immunodeficiency or immunosuppressive medication, neutropenia, and hypersensitivity or allergy to meropenem. | Continuous 44.9 (17.8), Intermittent 47.2 (16.3), p > 0.05 | Continuous male 78 (65.0%) and Intermittent 83 69.2%), p > 0.05 | Not reported |

| Dulhunty | 2012 | Australia and Hong Kong | prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial | 5 | 28 days | April 2010 - November 2011. | Intensive Care Foundation (2010), a Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Foundation (2011); and National Health and Medical Research Council Training Research Fellowships | 60 | Severe sepsis in the previous 48 h, initiation in < 24 h of ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin-tazobactam or meropenem. Previous ICU stay of more than 48 h. | < 18 years of age, drug allergy, palliative or supportive treatment only, ongoing renal replacement therapy, did not have a catheter with ⩾ 3 lumens, or had received study drug for > 24 h. | Continuous 54 (19), Intermittent 60 (19) | Continuous male 23 (76.7%) and Intermittent 19 (63.3%) | Not reported |

| Dulhunty | 2015 | Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind clinical trial | 25 | 90 days | July 2012 - April 2014 | National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia; Health Research Council, New Zealand | 432 | Adults with severe sepsis, use of β-lactams within the first 24 h | Allergy to β-lactams, pregnancy, under 18 years of age, previous antibiotic for more than 24 h. |

63.4 (5.2)continuous arm 63.7 (5.4) intermittent arm |

61.3% male in continuous arm, 61.4% in intermittent arm | Immunocompromised: 12.7% in continuous arm, 15.5% in intermittent arm |

| Dulhunty | 2024 |

Australia, Belgium, France, Malaysia, New Zealand, Sweden, and the United Kingdom |

Prospective, multicentre, open, phase III, randomised controlled trial (RCT) | 104 | 90 days | March 26 2018-January 11 2024 |

Dulhunty, Brett, De Waele, Finfer, McGuinness, Paterson, Peake, Rhodes, Roberts, Roger, Myburgh, Lipman |

7202 | Have a documented focus of infection or a strong suspicion of infection; stay in ICU; start administration of piperacillin-tazobactam or meropenem; administration of piperacillin-tazobactam or meropenem by intermittent infusion or continuous infusion. | Age < 18 years; having received a betalactam for > 24 h during the current infectious episode; suspected pregnancy; allergy to piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, or penicillin; need for renal replacement therapy; not compromising advanced Life support, including mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and vasopressor administration, for at least the next 48 h. Imminent and unavoidable death; prior enrollment in the BLING III study. | 59.3 (16.4) for continuous infusion and 59.6 (16.1) for intermittent infusion |

1190 (34.0) were female for continuous infusion, 1233 (34.9) were female for intermittent infusion 2308 (66.0) were male for continuous infusion and 2300 (65.1) for intermittent infusion |

Not reported |

| Hagel | 2022 | Germany | Controlled, randomized, multicenter and blind trial | 13 | 28 days | January 2017 to december 2020 |

The study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), 01EO1502” |

254 | Adult patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom therapy with piperacilin/tazobactam was initiated. Sepsis onset and start op p/t therapy ocurred no more than 24 h prior to randomization. | Contraindications to the study drug, impaired liver function, palliative care, pregnancy/lactation, participation in another clinical trial, and first measurement of piperacillin concentration not possible within 24 h. |

67.2 (13.9) conitnuos group and 65.3 (13.5)intermittent group |

-Continuos group, male 80 (63.5%) -Intermittent group male 92 (72.4%) |

Not reported |

| Khan | 2025 | South Africa | Prospective, single-center, open-labeled, randomized controlled trial | 1 | 90 days |

7 November 2020 to 6 November 2022, with follow-up until 3 February 2023 |

Tertiary academic hospital in South Africa. |

122 |

Adult patients (≥ 18 years) admitted to the ICU with sepsis (defined according to Sepsis-3 definition) and commenced on any of the 4 study beta-lactam antibiotics were eligible for inclusion. |

Receiving study antibiotics for more than 24 h at the time of screening, pregnant women, patients on renal replacement therapy or with known allergy to any of the study antibiotics. |

36.75 (36.75) conitnuos group and 31.75 (3.75)intermittent group |

-Continuous group, male 34 (58.6%) -Intermittent group male 41 (64%) |

Not reported |

| Monti | 2023 | Croatia, Italy, Kazakhstan, and Russia | Prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial | 26 | 28 days and 90 days | From June 5, 2018 to August 9, 2022 | FARM12MAEF from the AIFA (the Italian Medicines Agency) | 607 | 18 years or older, admitted to the ICU, required new antibiotic treatment with meropenem by clinician assessment, and had sepsis or septic shock. | Refusal of consent, prior treatment with carbapen antibiotics, very low probability of survival assessed by SAPS II and severe immunosuppression. | Continuous 65.5 (14), Intermittent 63.4 (15) | Continuous male 195 (36%) and Intermittent 209 (69%) | Diabetes: arm continuous 68 (23%), intermittent 83 (28%), Chronic kidney disease: continuous 57 (19%), intermittent 49 (16%), and Active cancer: continuous 27 (9%), intermittent 38 (13%) |

| Zhao | 2017 | Not available | Prospective, open, randomized controlled trial | 1 | Not reported | From June 2012 to December 2014 | The Clinical Research Special Foundation of Chinese Medical Association | 50 | All the patients who were diagnosed with severe sepsis or septic shock and were admitted to the ICU, received meropenem therapy, and provided informed consent were included in the study. Concomitant antimicrobial therapy was permitted. | Age < 18 years, pregnancy, acute or chronic renal failure with a glomerular filtration rate < 50 ml/min, immunodeficiency or taking immunosuppressant medication, allergy to meropenem, and previous application of meropenem in the past 2 weeks. | Continuous 68.0 (15.4), Intermittent 67.0 (12.2) | Continuous male 10 (40%) and Intermittent 11 (44.0%) | Not reported |

| Saad | 2023 | Benha, Egypt | Prospective randomized controlled trial | 1 | Not reported | From May 2022 to November 2022 | Benha University Hospitals | 60 | All the critically ill patients of both sexes, diagnosed with sepsis and admitted to the ICU, received meropenem therapy. Concomitant antimicrobial therapy was permitted. | Age < 18 years, pregnancy, acute or chronic renal failure with a glomerular filtration rate < 50 ml/min, immunodeficiency or taking immunosuppressant medication and allergy to meropenem, and previous application of meropenem in the past 2 weeks. | Continuous 54.4 (10.58), Intermittent 53.8 (10.67) | Continuous male 12 (40%) and Intermittent 13 (43.4%) | Not reported |

The follow-up duration was 28 and 90 days. The inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age, with a diagnosis or high suspicion of severe sepsis or septic shock, who started therapy with beta-lactams and were within the first 24 h of initiating the treatment regimen. The exclusion criteria were beta-lactam allergy, pregnancy, breastfeeding, prior use of antibiotics for more than 24 h, participation in another clinical trial, need for renal replacement therapy at the time of randomization, long-term corticosteroid therapy, receiving only palliative care or supportive treatment, impaired hepatic function, inadequate central venous catheter access, or death seemed imminent. There were no significant differences between the mean ages of the groups (p > 0.05). The main comorbidities identified in the participants were diabetes, chronic kidney disease, active cancer, and immunocompromised status. Regarding the baseline APACHE II score at baseline, significant differences were found between the means of the groups in the different studies (p < 0.05).

The beta-lactams used in the studies were Piperacillin–tazobactam, Ticarcillin–clavulanate, Cefotaxime, Cefepime, imipenem-cilastatin or Meropenem. Participants were randomized into the intervention group, which received continuous infusion of the drug, and the control group, which received the same drug intermittently. Concomitant therapies administered included glycopeptides, macrolides, aminoglycosides, quinolones, cephalosporins (third and fourth generation), nitroimidazoles, oxazolidinones, vancomycin, linezolid, tigecycline, rifampicin, colistin, and others (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of intervention and control of the studies included

| Author(s) | Year of publication | Type of intervention | Control group description | Drug name | Dosage | Treatment duration, days (sd) | Concomitant therapies | Clinical cure/definition | All-cause mortality/definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aardema | 2020 |

Continuous versus intermittent infusion of cefotaxime in critically ill patients |

Intermittent infusion of β-lactamics | cefotaxime |

Intermittent dosing (1 g every 6 h) or continuous dosing (4 g/24 h, after a loading dose of 1 g infused over 40 min) |

Continuous infusion 4.0 (0.61) Intermitent infusion 4.0 (0.61) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Abdul-Aziz | 2016 | Intervention: Continuuous (CI) Vs Control: Intermittent bolus (IB) beta-lactam | Intermittent bolus (IB) beta-lactam | Cefepime, meropenem, piperacilin/tazobactam | Cefepime 6 g, meropenem 3 g, p/t 18 g. | 6.5 (1.15) continuous, 6.5 (1.15) intermittent | 32 (47%) in both treatment arms. Azithromycin, Vancomycin, Metronidazole, Clindamycin, Aminoglycosides, Colistin, Other. | (1) resolution: complete disappearance of all signs and symptoms related to the infection; (2) improvement: marked or moderate reduction in the severity of the disease and/or the number of signs and symptoms related to the infection; or (3) failure: insufficient reduction in the signs and symptoms of the infection to be considered improvement, death, or undetermined for any reason. “Yes” for resolution and ‘No’ for all other outcomes (i.e., the sum of 2 and 3 above). | Number of deaths up to 30 days |

| Chytra | 2012 |

Continuous versus intermittent application of meropenem in critically ill patients |

Intermittent application of meropenem |

Meropenem |

The patients in the Infusion group received a loading dose of 2 g of meropenem in 20 ml of normal saline infused by central Line over 30 min followed immediately by continuous infusion of 4 g of meropenem over 24 h. |

9.0 (5.0 to 16.0) continuous, 7.0 (3.0 to 11.0) intermittent | Treatment was used in more than 50% of patients in both groups. It included oxacillin, ampicillin, piperacillin/tazobactam, gentamicin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, fluconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B. | A complete resolution of all acute signs and symptoms of infection, with no new signs or symptoms associated with the original infection | Not reported |

| Dulhunty | 2012 | Infusion and placebo boluses (intervention arm) vs. (2) placebo infusion and active boluses (control arm) | Intermittent infusion of β-lactamics | Piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, and ticarcillin-clavulanate | 16 mg/L for piperacillin and ticarcillin, and 2 mg/L for meropenem | 3.06 (1.2) intervention and4.5 (1.4) control | Not reported |

(1) Resolution: disappearance of all signs and symptoms related to the infection. (2) Improvement: marked or moderate reduction in the severity and/or number of signs and symptoms of the infection. (3) Failure: insufficient reduction in the signs and symptoms of the infection to be considered an improvement, including death or indeterminate (assessment not possible for any reason). Clinical cure: (1) Resolution: as indicated above. (2) All other findings (i.e., the sum of 2 and 3 above). |

Number of deaths up to 28 days |

| Dulhunty | 2015 | Continuous vs. intermittent infusion of β-lactams | Intermittent infusion of β-lactams | Piperacillin–tazobactam, Ticarcillin–clavulanate, Meropenem |

13.5 g (0.2) for piperacillin–tazobactam, 2.75 g (0.2) for meropenem, and 12.4 g for ticarcillin–clavulanate |

3.5 (1.2) in continuous arm, 3.8 (1.17) in intermittent arm | They were used in 36.3% of cases, including glycopeptides, macrolides, nitroimidazoles, aminoglycosides, and quinolones. | Complete resolution of all signs and symptoms related to the infection, or marked/moderate improvement in severity. | Number of deaths up to 90 days |

| Dulhunty | 2024 | Continuous vs. intermittent infusion of β-lactams | Infusión intermitente de β-lactámicos | piperacilinatazobactam o meropenem |

A defined daily dose of 14 g for piperacillin-tazobactam and 3 g for meropenem was used as a reference measure |

6.2 days (2.06) and 6.2 days (2.07) in the continuous and intermittent infusion groups, respectively | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, Vancomycin, Gentamicin, Metronidazole, Ceftriaxone, Amikacin, Amoxicillin/Ampicillin, Azithromycin, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Cefazolin, Ciprofloxacin, Flucloxacillin, Clarithromycin, Erythromycin, Clindamycin, Linezolid, Cefuroxime, Penicillin, Cefotaxime, Teicoplanin, Doxycycline, Ceftazidime, Cefepime, Levofloxacin, Tobramycin, Rifampicin, Amoxicillin/Ampicillin-sulbactam, Cephalexin, Cloxacillin, Lincomycin, Daptomycin, Spiramycin, Moxifloxacin, Polymyxin B, Aztreonam, Rifaximin, Imipenem-cilastatin, Temocillin, Ertapenem, Isoniazid, Phenoxymethylpenicillin, Tigecycline, Cefoperazone, Fidaxomicin, Ofloxacin, Pyrazinamide, Colistin, Chloramphenicol, Dicloxacillin, Ethambutol, Nitrofurantoin, other. | Clinical cure was defined as the completion of the β-lactam antibiotic treatment course (on or prior to Day 14) without recommencement of antibiotic therapy within 48 h of cessation. | Number of deaths up to 90 days |

| Hagel | 2022 | Continuous vs. intermittent infusion of β-lactams | Intermittent infusion of β-lactams | piperacilina/tazobactam | 10.3 ± 5.6 TDM group, 9.8 ± 2.5 no TDM group |

The maximum duration of intervention was 10 days. Mean duration of treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam (TDM 4.8 ± 3 days vs. no TDM 4.8 ± 2.8 days. Total duration of antibiotic therapy (TDM 6.8 ± 10 days vs. non-TDM 6.6 ± 8.7 |

Fuoroquinolone (28.1% of patients), followed by vancomycin (14.4%), macrolides (13.6%) and patients), followed by vancomycin (14.4%), macrolides (13.6%) and linezolid (10.8%) |

Clinical cure was described as resolution of signs and symptoms of infection 14 days after cessation of treatment. | Number of deaths up to 28 days |

| Khan | 2025 | Continuous versus intermittent bolus dosing of beta-lactam antibiotics | Intermittent infusion of β-lactams |

Amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem-cilastatin and meropenem. |

Median antibiotic duration, CI group, 7 days (IQR 5–8.5) vs. IB group, 6 days (IQR 4–8), p = 0.191 |

Vasopresor | Completion of antibiotics by day 14 without recommencement within 48 h. | Number of deaths up to 90 days | |

| Monti | 2023 | meropenem by continuous administration vs. meropenem by intermittent administration | Intermittent infusion of β-lactamics | Meropenem | A median overall dose of 24 g of meropenemin the continuous administration group and 21 g in the intermittent administration group | Median antibiotic duration (IQR): interventtion group 11(6–18), control group 11(6–17) | 74% received additional antibiotics, including glycopeptides, cephalosporins, oxazolidinones, lipopeptides, quinolones, tigecycline, aminoglycosides, macrolides, rifampicin, and others. | Not reported | Number of deaths up to 28 days |

| Zhao | 2017 | meropenem by continuous administration vs. meropenem by intermittent administration | Intermittent infusion of β-lactamics | Meropenem | In the continuous administration group, a loading dose of 0.5 g of meropenem in 100 ml of normal saline was administered intravenously, infused over 30 min, followed immediately by a continuous infusion of 3 g of meropenem over 24 h. Then, 0.5 g of meropenem was infused over 4 h in 50 ml of normal saline solution. Patients in the intermittent group received the first dose of 1.5 g of meropenem in 100 ml of normal saline solution infused over 30 min, followed by 1 g in 100 ml of normal saline solution infused. | 7.6 (12.3) intervention and 19.4 (5.5) control | Concomitant antimicrobial therapy was permitted. | Clinical success was defined as complete or partial resolution of temperature, clinical signs and symptoms of infection, and leukocytosis. | Not reported |

| Saad | 2023 | meropenem by continuous administration vs. meropenem by intermittent administration | Intermittent infusion of β-lactamics | Meropenem | Continuous group: a loading dose of 0.5 g of meropenem in 100 ml of normal saline solution over 30 min, followed by a continuous infusion of 3 g of meropenem over 24 h. Then, infusion of 0.5 g of meropenem over 4 h in 50 ml of saline solution. Intermittent group: patients in this group will receive the first dose of 1.5 g of meropenem in 100 ml of saline solution infused over 30 min, followed by 1 g in 100 ml of normal saline solution infused over 30 min every 8 h | 9.93 (5.33) intervention and 11.53 (2.69) control | Concomitant antimicrobial therapy was permitted. | Clinical success is defined as complete or partial resolution of temperature, clinical signs and symptoms of infection, and leukocytosis. | Was not defined |

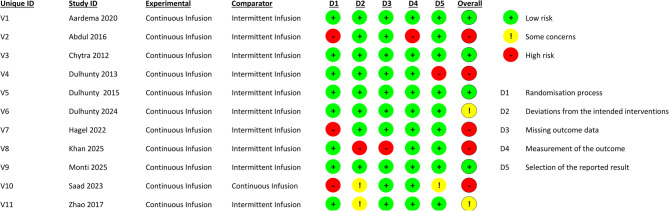

Risk of bias assessment

There were five studies with a high risk of bias, and two studies with some concerns. Three studies had a high risk of bias in the domain of the randomization process, one study in deviations from intended interventions, another in missing outcome data and measurement of the outcome, and one more in the selection of the reported results (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment

Effects of continuous infusion on outcomes

In terms of all-cause mortality, eight trials with a total of 8582 patients provided extractable data (Fig. 3A). The meta-analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in mortality between the continuous and intermittent infusion groups (Risk Ratio [RR] 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88 to 1.01; CoE Very low), with a prediction interval of 0.87 to 1.02. Notably, statistical heterogeneity was absent (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.64), which enhances the confidence in the consistency of the result across included studies. Most of the weight in the analysis was contributed by a large multicenter trial [8], yet its findings aligned with those of smaller studies. Despite the trend favoring continuous infusion, the effect estimate did not reach statistical significance, and the overall certainty of evidence was rated as very low due to concerns about risk of bias and imprecision.

Fig. 3.

Mortality according to comparison between continuous infusions versus intermittent infusions of β-Lactam antibiotics. (A) All-cause mortality. (B) Hospital mortality. (C) All-cause ICU mortality

Regarding the Hospital mortality (Fig. 3B), five randomized controlled trials including 7772 participants evaluated the effect of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion. The pooled risk ratio was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85 to 0.99; CoE Low), with a prediction interval of 0.82 to 1.02. No significant heterogeneity was observed between studies (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.7357), reinforcing the consistency of the finding and reinforcing the robustness of the finding.

For ICU mortality(Fig. 3C), data from eight randomized trials involving 8582 patients demonstrated no significant difference between infusion strategies. The pooled risk ratio was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.88 to 1.01; CoE Very low), with a prediction interval of 0.87 to 1.02. There was no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.6423), supporting the consistency of findings across studies. These results indicate that continuous infusion does not meaningfully improve ICU survival compared to intermittent infusion.

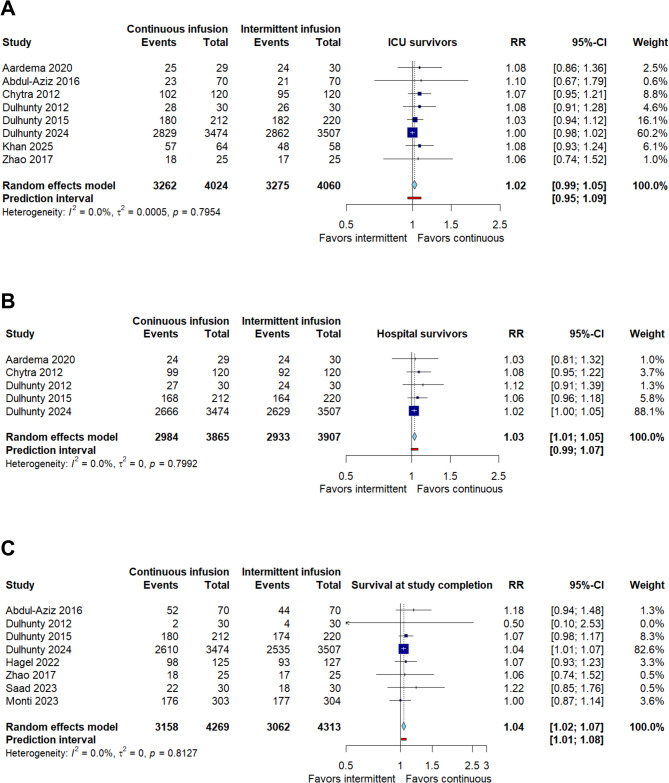

For ICU survival (Fig. 4A), data from eight randomized trials involving 8084 patients demonstrated no significant difference between infusion strategies. The pooled risk ratio was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.05; CoE Very low), with a prediction interval of 0.95 to 1.09. There was no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.79), supporting the consistency of findings across studies. These results indicate that continuous infusion does not meaningfully improve ICU survival compared to intermittent infusion.

Fig. 4.

Survival according to comparison between continuous infusions versus intermittent infusions of β-Lactam antibiotics. (A) ICU survival. (B) Hospital survival. (C) Survival at study completion

On the other hand, in the analysis of hospital survival (Fig. 4B), five studies including 7772 participants showed a significant benefit of continuous infusion compared to intermittent administration. The pooled risk ratio was 1.03 (95% CI: 1.01 to 1.07; CoE Low), with a prediction interval of 0.99 to 1.07. No significant heterogeneity was observed between studies (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.79), reinforcing the consistency of the finding and reinforcing robustness of the finding. Taken together, these results suggest that continuous infusion of β-lactam infusion could improve short-term survival in hospital settings.

Survival at study completion was assessed in eight randomized controlled trials comprising a total of 8582 patients (Fig. 4C). The pooled analysis demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in survival among patients receiving continuous β-lactam infusion compared to those treated with intermittent infusion, with a risk ratio (RR) of 1.04 (95% CI: 1.02 to 1.07; CoE Low). The prediction interval ranged from 1.01 to 1.08, indicating that the beneficial effect is likely to be observed across different clinical contexts. No statistical heterogeneity was detected (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.81), suggesting a high degree of consistency in the observed effect across studies. Notably, the largest contribution to the overall estimate came from a large multicenter trial [8], but the direction of effect was consistent across nearly all included trials. These findings provide low-certainty evidence, according to GRADE criteria, supporting the potential benefit of continuous infusion in improving short-term survival outcomes among patients with sepsis.

Regarding the duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay (Fig. 5A), ten randomized controlled trials, including 8928 participants, evaluated the effect of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion. The pooled analysis showed a non-significant mean difference of 0.75 days (95% CI: −1.17 to 2.68; CoE Very low), favoring neither intervention. The prediction interval ranged widely from − 5.42 to 6.92, suggesting considerable uncertainty in future study effects. Heterogeneity was notably high (I² = 97%, τ² = 6.7159, p < 0.001), indicating substantial inconsistency across studies. Such variability may reflect differences in patient severity, clinical practices, or antibiotic regimens. No statistically significant difference was observed in ICU length of stay between continuous and intermittent infusion, and the estimate remains imprecise due to high heterogeneity. Overall, the evidence remains very uncertain as to whether continuous infusion reduces ICU stay duration.

Fig. 5.

Clinical cure according to comparison between continuous infusions versus intermittent infusions of β-Lactam antibiotics. (A) Clinical cure. (B) Clinical cure subgroups by year

In terms of hospital length of stay (Fig. 5B), four studies encompassing 8,270 patients were included. The random-effects meta-analysis revealed a non-significant reduction in the length of hospital stay for patients receiving continuous infusion compared to those on intermittent infusion, with a pooled mean difference of −2.51 days (95% CI: −10.13 to 5.12; CoE Very low). The prediction interval extended from − 39.86 to 34.85 days, further emphasizing the imprecision of this estimate. Again, heterogeneity was extremely high (I² = 100%, τ² = 60.2334, p < 0.01), limiting the reliability of the pooled result. These findings suggest that any potential benefit of continuous infusion on hospital stay is highly uncertain and likely context-dependent.

In terms of clinical cure (Fig. 6A), nine randomized controlled trials involving a total of 8190 patients reported the number of patients who achieved resolution of infection symptoms. The pooled analysis favored continuous β-lactam infusion, with a risk ratio (RR) of 1.42 (95% CI: 1.12 to 1.80; CoE ow), although the confidence interval included the null value, indicating statistical non-significance. The prediction interval ranged from 0.72 to 2.80, reflecting considerable uncertainty regarding future effects. Heterogeneity was high(I² = 82.0%, τ² = 0.0750, p = < 0.0001), suggesting variability in treatment effects across studies. Several included trials demonstrated point estimates clearly favoring continuous infusion; however, variation in definitions of clinical cure, baseline severity, and antibiotic selection likely contributed to the inconsistency.

Fig. 6.

Effect of continuous infusion on secondary outcomes: a Clinical cure; b Adverse events

In respect to clinical cure, meta-regression (mixed-effects model, k = 9) explained 100% of the heterogeneity (R² = 100%), with no evidence of residual heterogeneity (tau² = 0; I² = 0%; p = 0.688). The overall test for moderators was significant (QM [6] = 42.75; p < 0.0001). Positive associations were observed with year of publication (p = 0.0002) and number of centers (p < 0.0001), while the proportion of men, APACHE score, and sample size were negatively associated with the effect (all with p < 0.01). Mean age showed no significant association (p = 0.09). These findings suggest that some study characteristics influence the observed effects on clinical cure (Supplementary material).

Subgroup clinical cure

Similarly, subgroup analysis by year of publication showed variation in the estimated effects of continuous infusion on clinical cure. Studies published after 2020 reported a statistically significant effect in favor of continuous infusion (RR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.22), with low heterogeneity (I² = 30.7%). In studies published between 2016 and 2020, the effect was larger (RR = 1.51; 95% CI 0.45 to 5.08), but accompanied by large uncertainty and no evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 0%). In contrast, studies prior to 2015 presented an RR of 1.64 (95% CI 0.55 to 4.86), with high heterogeneity (I² = 92.5%). The test for interaction between subgroups was statistically significant (Q = 11.21; gl = 2; p = 0.0037), indicating that the year of publication could be modifying the estimated effect. These findings could reflect changes in diagnostic criteria, methodological improvements, or greater standardization in the definition of clinical cure in more recent studies (Fig. 6B).

For adverse events, six studies, including 8619 patients provided extractable data. The pooled analysis yielded a non-significant reduction in adverse events for continuous infusion compared to intermittent administration, with a risk ratio of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.60 to 1.12; CoE Very low). The prediction interval extended from 0.52 to 1.29, suggesting wide variability in future expected effects. Importantly, no statistical heterogeneity was observed across studies (I² = 0%, τ² = 0, p = 0.8096), indicating consistent results. Despite some studies reporting fewer adverse events in the continuous group, the limited number of events and low event rates in some trials contributed to the imprecision of the overall effect estimate (Supplementary material).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 11 randomized controlled trials involving 9166 patients with sepsis and septic shock and provides comprehensive evidence on the effectiveness of continuous versus intermittent infusion of β-lactam antibiotics. The findings demonstrate that continuous infusion confers modest but statistically significant improvements in short-term survival outcomes, while the effects on mortality and other clinical endpoints remain inconclusive.

Regarding patient survival at study completion, a significant difference was found in favor of continuous infusion, demonstrating better survival at the end of the study. This finding is consistent with Zhao et al., who found a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (RR, 0.83; 95% CI: 0.72–0.97; n = 2130 patients) and clinical improvement (RR, 1.16; 95% CI: 1.03–1.31; n = 1410 patients) in the continuous infusion group compared to the intermittent infusion group [18]. However, this finding is not consistent across all reviewed studies, as in the study by Chen et al., who found no difference in patient survival based on the type of infusion (RR, −0.30, 95% CI −0.73-0.13; n = 764 patients) [19].

Specific results on survival in the hospital and ICU settings showed a different impact depending on the type of administration. In particular, continuous infusion was associated with a significant improvement in hospital survival, suggesting that maintaining stable plasma concentrations of β-lactams offers greater clinical benefits during hospitalization. This finding is especially relevant from a public health perspective, as survival to discharge is a key indicator of therapeutic success and quality of care for patients with sepsis and septic shock [19].

In contrast, both survival and mortality in the ICU showed no significant differences between the infusion strategies used, a finding consistent with previous studies that demonstrate the complexity of antimicrobial management in intensive care [20, 21]. This absence of effect may be explained by the complexity of the ICU environment, where multiple factors and clinical conditions influence patient evolution, attenuating the impact of the manner of antibiotic administration.

Furthermore, these discrepancies reflect the influence of additional variables such as total duration of treatment, type of drug, other concurrent medications such as vasopressors and antifungals, patient comorbidities, individual response to treatment, and specific characteristics of the hospital or intensive care unit [21]. This complex clinical context emphasizes the importance of implementing comprehensive and personalized treatments to optimize antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients, since the lack of visible differences does not imply that it is not necessary to continue developing strategies to improve outcomes [20, 21].

Concerning all-cause mortality, the results suggest that continuous infusion may be associated with a reduced risk of death compared to intermittent infusion, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. This finding is in line with the study conducted by Ishikawa et al., who found no differences between the groups (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.44–3.54; n = 344 patients), giving greater relevance to the clinical conditions of the participants in the progression of mortality [20]. Taccone et al. suggest that continuous drug administration may optimize the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of β-lactams, providing more adequate and stable plasma levels, reducing complications associated with changes in plasma concentrations, and improving patient outcomes [22]. However, uncertainty about the benefits of this strategy in reducing mortality persists in the literature.

In this regard, hospital mortality showed a statistically significant reduction and a protective effect associated with continuous infusion. However, Ishikawa et al. found no significant differences between groups (RR 1.25; 95% CI 0.44–3.54; n = 344 patients), attributing greater importance to the clinical conditions of the participants in the progression of mortality [20]. On the other hand, Taccone et al. suggest that continuous administration of β-lactams can optimize their pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, maintaining more adequate and stable plasma levels, which reduces complications arising from fluctuations in concentrations and improves clinical outcomes. Consequently, maintaining constant blood levels of β-lactams maximizes their bactericidal efficacy, favoring a better clinical response and decreasing mortality throughout hospitalization. Therefore, this benefit suggests that adjusting antimicrobial administration by continuous infusion could be key to improving the clinical course and medium-term prognosis in patients with sepsis and septic shock [22].

Regarding clinical cure, continuous infusion was superior to intermittent infusion with statistical significance, although substantial heterogeneity was observed. Meta-regression analysis fully explained this heterogeneity, identifying significant associations with year of publication and number of participating centers. Subgroup analysis revealed evolving treatment effects over time, with studies published after 2020 showing statistically significant benefits and reduced heterogeneity. This temporal difference likely reflects methodological improvements, standardization of cure definitions, and improved clinical protocols in more recent research.

This finding is consistent with the report by Abdul-Aziz et al., who, in twelve clinical trials, observed a significantly higher cure rate in the continuous infusion group compared to the intermittent dosing group of β-lactams (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.07–1.31; n = 8301 patients) [21]. Additionally, Williams et al. and Hagiya reported that continuous infusions have shown superiority in severe infections by maintaining effective antibiotic concentrations, which could theoretically improve clinical outcomes [23, 24].

The superiority of continuous infusion in terms of clinical cure highlights its usefulness in the management of severe infections, especially in critically ill patients. Maintaining constant antibiotic levels above the minimum inhibitory concentration can improve the effectiveness of treatment and contribute to decreasing bacterial resistance, a growing challenge in clinical practice.

However, given the diversity of patients and clinical conditions, it is essential to continue investigating continuous infusion to determine in which scenarios it is most beneficial. This research provides relevant evidence that can guide future recommendations, but it is still necessary to deepen its application to optimize care and clinical outcomes.

These findings are especially relevant, mainly because there were no significant differences between group means according to their APACHE scores, indicating that the severity level of the patients on admission was homogeneous. Allowing a more precise evaluation of the effect of continuous versus intermittent infusion, in which better results of continuous infusion were evidenced in the clinical response of patients.

Although most of the meta-analyses included in our review suggest that continuous infusion has certain advantages over intermittent infusion in terms of clinical efficacy and control of plasma concentrations, it is important to recognize that not all studies reached the same conclusions. As Sumi et al. and Roberts et al. point out, some meta-analyses found no significant differences between the two methods of administration [25, 26]. These findings suggest that the type of infusion may not be a determining factor in all populations or clinical conditions.

The disparity between the results of the different meta-analyses could be explained, at least in part, by relevant methodological variations. First, the number of included studies varied between meta-analyses, which directly influences the statistical power and precision of the estimates. Second, the inclusion of more recent studies, with more heterogeneous populations or with null results, could have substantially modified the conclusions of the overall analyses. This aspect, which was not always discussed in previous meta-analyses, deserves further attention.

Additionally, clinical factors such as disease severity, the presence of comorbidities, the specific type of antimicrobial used, and treatment adaptations according to the patient’s clinical status may introduce high variability in individual results [27]. However, these factors alone do not fully explain the discrepancies between meta-analyses, as the aggregate effect should, in principle, be controlled by systematic design and sensitivity analyses or meta-regressions. Therefore, it is also necessary to consider the quality of the primary studies, the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in each review, as well as the time at which the literature search was performed.

In our review, we have tried to integrate and contrast these aspects, and we emphasize that the differences in the results not only reflect clinical diversity but also methodological decisions that should be critically evaluated when interpreting the available literature.

Regarding adverse effects, the study found no significant differences in the incidence of these events and the infusion modality. In this regard, the safety profile was comparable between both strategies, with no statistically significant differences in the incidence of adverse events and no heterogeneity among the studies analyzed. This finding aligns with Zhao et al., who reported similar results (RR, 0.91; 95% CI: 0.64–1.29; n = 1,064 patients) [26]. Although adverse effects may occur due to high doses and the accumulation from continuous infusion, using β-lactams has proven very safe. This may explain the lack of significant differences observed [28].

However, it is essential to note that although adverse events appear to be lower with intermittent infusions, other studies have found that the incidence of these events can vary widely according to the type of patient, the type of drug and the clinical context [25, 28].

There were no significant differences in treatment duration between the two infusion methods, indicating that both techniques are equally valid in terms of efficiency and that other factors, such as the patient’s severity or the characteristics of the treatment, are likely to play a larger role in their duration. The result indicated that the continuous infusion strategy of β-lactams was not associated with a shorter duration of treatment compared to the intermittent infusion strategy. This finding is similar to that reported by Li et al.. (MD −0.39; 95% CI: −1.04–0.27; P = 0.24; n = 1,505 patients), who also found no differences in the total duration of treatment between continuous and intermittent infusions [29]. Chen et al. attributed this result to the complexity of each case and the environment in which the research is conducted [3].

The duration of stay in the ICU and hospital was also similar between the two groups, reinforcing that both methods are equally effective. Li et al. showed that the continuous infusion strategy did not shorten the duration of stay in the ICU (MD −0.01; 95% CI: −0.85-0.82; n = 1,582 patients), nor did it shorten the duration of stay in the hospital (MD 1.05; 95% CI: −0.65-2.76; n = 1,472 patients) [29]. On the other hand, Lokhandwala et al. demonstrated a reduction in ICU stays and overall hospitalization times; however, the difference was not significant [30].

This study has some limitations. First, there was high heterogeneity among the included studies, which may limit the generalization of the findings. Additionally, some studies did not adjust for confounding factors, such as patient severity or comorbidities, which may have biased the results. Finally, some studies had a small sample size, limiting the statistical power to detect significant differences. However, more extensive, experimental, multicentric studies must delve deeper into the findings.

Despite these limitations, strict selection criteria allowed for the inclusion of studies that compared the same intervention and used the same definitions in their outcomes. Additionally, the analysis provided significant findings that can be used in decision-making.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that continuous infusion of β-lactams reduces hospital mortality and increases survival both during hospitalization and at the end of the study. It also suggests an increase in the clinical cure rate, which could reflect a better response to treatment in critically ill patients. However, the evidence is very uncertain regarding its effect on all-cause mortality, survival in the intensive care unit, length of ICU and hospital stay, as well as on the occurrence of adverse events. Although continuous infusion may decrease ICU mortality and length of hospital stay, the available evidence is highly uncertain regarding its effectiveness on these outcomes.

Evidence suggests that continuous infusion of β-lactams may offer significant benefits in reducing hospital mortality and improving clinical cure. However, additional and higher-quality studies are required to confirm these findings and to assess with greater certainty their impact on other clinical outcomes and their safety profile.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B.; methodology D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B.; software, J.J.B.; validation, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B.; formal analysis, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B.; investigation, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B.; resources, J.J.B.; data curation, J.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B; writing—review and editing, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B; visualization, D.A.T, H.C.G., E.T.A., and J.J.B; supervision, J.J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Universidad Señor de Sipan–Vicerrectorado de investigacion.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Clinical trial

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

1/16/2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12879-025-12213-6

References

- 1.Hyun D, Seo J, Lee SY, et al. Continuous piperacillin-tazobactam infusion improves clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective, single-centre study. Antibiotics. 2022;11: 1508. 10.3390/antibiotics11111508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.I M-L RF. Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: results from a guideline-based performance improvement program. Crit Care Med. 2014;42. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000330.

- 3.Chen C-H, Chen Y-M, Chang Y-J, et al. Continuous versus intermittent infusions of antibiotics for the treatment of infectious diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98: e14632. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyun D-G, Seo J, Lee SY, et al. Continuous piperacillin-tazobactam infusion improves clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective, single-centre study. Antibiotics. 2022;11: 1508. 10.3390/antibiotics11111508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawaz S, Barton S, Nabhani-Gebara S. Comparing clinical outcomes of piperacillin-tazobactam administration and dosage strategies in critically ill adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:430. 10.1186/s12879-020-05149-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.H S, B F, B T, et al. Effect of therapeutic drug monitoring-based dose optimization of piperacillin/tazobactam on sepsis-related organ dysfunction in patients with sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48. 10.1007/s00134-021-06609-6.

- 7.Aardema H, Bult W, Van Hateren K, et al. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of cefotaxime in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial comparing plasma concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;dkz463. 10.1093/jac/dkz463.

- 8.Abdul-Aziz MH, Sulaiman H, Mat-Nor M-B, et al. Beta-lactam infusion in severe sepsis (BLISS): a prospective, two-centre, open-labelled randomised controlled trial of continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion in critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1535–45. 10.1007/s00134-015-4188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chytra I, Stepan M, Benes J, et al. Clinical and microbiological efficacy of continuous versus intermittent application of meropenem in critically ill patients: a randomized open-label controlled trial. Crit Care. 2012;16:R113. 10.1186/cc11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulhunty JM, Brett SJ, De Waele JJ, et al. Continuous vs intermittent β-lactam antibiotic infusions in critically ill patients with sepsis: the BLING III randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;332:629–37. 10.1001/jama.2024.9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulhunty JM, Roberts JA, Davis JS, et al. Continuous infusion of Beta-Lactam antibiotics in severe sepsis: A multicenter Double-Blind, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:236–44. 10.1093/cid/cis856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulhunty JM, Roberts JA, Davis JS, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of continuous versus intermittent β-lactam infusion in severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1298–305. 10.1164/rccm.201505-0857OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagel S, Bach F, Brenner T, et al. Effect of therapeutic drug monitoring-based dose optimization of piperacillin/tazobactam on sepsis-related organ dysfunction in patients with sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48:311–21. 10.1007/s00134-021-06609-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan AB, Abdul-Aziz MH, Hindle L, et al. Continuous versus intermittent bolus dosing of beta-lactam antibiotics in a South African multi-disciplinary intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. J Infect. 2025;90: 106487. 10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monti G, Bradic N, Marzaroli M, et al. Continuous vs intermittent meropenem administration in critically Ill patients with sepsis: The Mercy randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(2):141–151. 10.1001/jama.2023.10598.

- 16.Saad S, Aglan B, Shaboob E, et al. Continuous versus intermittent use of meropenem in septic critically ill patients: A randomized controlled trail. Benha Med J. 2023;0:0–0. 10.21608/bmfj.2023.247556.1949. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao HY, Gu J, Lyu J, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic efficacies of continuous versus intermittent administration of meropenem in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A prospective randomized pilot study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(10):1139–1145. 10.4103/0366-6999.205859.

- 18.Zhao Y, Zang B, Wang Q. Prolonged versus intermittent β-lactam infusion in sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14:30. 10.1186/s13613-024-01263-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen P, Chen F, Lei J, et al. Clinical outcomes of continuous vs intermittent meropenem infusion for the treatment of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2020;29:993–1000. 10.17219/acem/121934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishikawa K, Shibutani K, Kawai F, et al. Effectiveness of extended or continuous vs. bolus infusion of broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics for febrile neutropenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics. 2023;12:1024. 10.3390/antibiotics12061024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul-Aziz MH, Hammond NE, Brett SJ, et al. Prolonged vs intermittent infusions of β-lactam antibiotics in adults with sepsis or septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2024;332:638–48. 10.1001/jama.2024.9803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taccone FS, Laterre P-F, Dugernier T, et al. Insufficient β-lactam concentrations in the early phase of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care. 2010;14:R126. 10.1186/cc9091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams P, Cotta MO, Abdul-Aziz MH, et al. In Silico evaluation of a beta‐lactam dosing guideline among adults with serious infections. Pharmacotherapy. 2023;43:1121–30. 10.1002/phar.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagiya H. Detailed regimens for the prolonged β-lactam infusion therapy. J Infect Chemother. 2024;30:1324–6. 10.1016/j.jiac.2024.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumi CD, Heffernan AJ, Naicker S, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of intermittent versus extended and continuous infusions of piperacillin/tazobactam in a hollow-fibre infection model against Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;77:3026–34. 10.1093/jac/dkac273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Roberts MS, et al. First-dose and steady-state population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Piperacillin by continuous or intermittent dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:156–63. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrié C, Legeron R, Petit L, et al. Higher than standard dosing regimen are needed to achieve optimal antibiotic exposure in critically ill patients with augmented renal clearance receiving piperacillin-tazobactam administered by continuous infusion. J Crit Care. 2018;48:66–71. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passon SG, Schmidt AR, Wittmann M, et al. Evaluation of continuous ampicillin/sulbactam infusion in critically ill patients. Life Sci. 2023;320: 121567. 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Long Y, Wu G, et al. Prolonged vs intermittent intravenous infusion of β-lactam antibiotics for patients with sepsis: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13:121. 10.1186/s13613-023-01222-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lokhandwala A, Patel P, Isaak AK et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of prolonged infusion and intermittent infusion of meropenem in patients with sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus N D;15:e46990. 10.7759/cureus.46990

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.