Highlights

-

•

Bone invasion occurs in ∼5–11 % of extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (STS).

-

•

MRI accurately detects bone invasion; no universal radiologic criteria exist.

-

•

Osseous invasion predicts significantly poorer overall survival.

-

•

En-bloc resection ensures oncologic control but causes notable morbidity.

-

•

Selective bone-sparing techniques provide comparable control and better function.

Keywords: Soft-tissue sarcoma, Osseous invasion, Extremity sarcoma, Bone-sparing surgery, Limb salvage, Multidisciplinary management, Musculoskeletal oncology

Abstract

Background

Osseous invasion in extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) occurs in approximately 5–11% of cases and is associated with larger tumor size, higher histologic grade, deeper location, and increased risk of metastasis. Despite its relative rarity, bone invasion is a critical prognostic factor, presenting unique diagnostic and surgical challenges.

Purpose

This review aimed to synthesize current evidence on the prevalence, diagnostic imaging, surgical management, and prognostic impact of osseous invasion in extremity STS and to offer evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice.

Methods

A comprehensive narrative review was conducted using structured searches of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library, focusing on studies reporting original data on extremity STS with bone involvement. The key outcomes included diagnostic accuracy, surgical margins, functional recovery, and survival rates.

Results

Bone invasion significantly predicted poorer overall and disease-free survival, with 5-year survival rates of 27–40% compared to 60–70% in non-invasive cases. MRI remains the imaging modality of choice, although standardized radiological criteria for bone invasion are lacking. En-bloc resection provides reliable local control but carries substantial morbidity. Emerging bone-sparing techniques, such as subperiosteal and hemicortical resections, have demonstrated comparable oncologic outcomes with superior functional results in selected patients.

Conclusions

Bone invasion in extremity STS represents a high-risk tumor subset that warrants individualized multidisciplinary management. While wide resection remains the standard treatment in cases with medullary involvement, selected patients may benefit from function-preserving approaches without compromising oncologic safety. Future research should focus on standardizing the diagnostic criteria, validating conservative surgical strategies, and refining multimodal treatment protocols to optimize outcomes.

1. Introduction

Soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) of the extremities are uncommon mesenchymal malignancies that can invade adjacent bones [1]. Clinically, osseous invasion is suspected when patients present with new focal bone pain or tenderness near a known soft tissue mass [2]. Pathological confirmation of true bone invasion occurs when tumor cells infiltrate the medullary cavity or trabecular bone [3,4]. Radiologically, bone invasion is generally identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by the disruption of the characteristic low-signal cortical bone line on T1-weighted images and abnormal intramedullary signal intensity contiguous with the soft tissue tumor [5,6].

Although it is clinically intuitive that bone involvement could indicate worse outcomes, the precise prevalence, standardized diagnostic criteria, and prognostic significance of osseous invasion in extremity STS remain controversial. Some studies have reported that bone-invasive tumors do not exhibit significantly higher local recurrence rates than non-invasive cases, provided they are adequately resected with clear surgical margins [[7], [8], [9]]. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated a statistically significant association between bone invasion and more aggressive tumor biology, leading to significantly poorer survival rates [[10], [11], [12]]. These conflicting findings highlight the clinical challenges in managing bone-invasive STS, and underscore the need for more precise definitions and consensus.

In this narrative review, we critically evaluated existing literature on extremity STS with bone invasion. Specifically, we examined (A) the reported prevalence of bone involvement and definitions used in clinical, radiologic, and pathologic settings; (B) diagnostic imaging methods emphasizing MRI sequences and the utility of contrast enhancement; (C) histologic subtypes most frequently associated with bone invasion and their common anatomical locations; and (D) surgical management approaches, including wide (segmental) resection versus bone-sparing strategies, margin considerations, and the role of adjuvant therapies. We further highlight key controversies, such as the oncologic safety of subperiosteal resections and acceptable margin status, and identify gaps in the literature that require further research. This comprehensive overview aims to provide an updated critical perspective to guide clinical decision making and inform future studies addressing this challenging clinical scenario.

2. Methods

We conducted a comprehensive narrative review to synthesize current evidence on osseous invasion in extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (STS). A structured search of PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase, and Cochrane Library was performed for articles published between January 1990 and December 2024. The search strategy combined MeSH terms and free-text keywords, including: “soft tissue sarcoma,” “bone invasion,” “osseous invasion,” “extremity,” “MRI,” “imaging,” “resection,” “limb salvage,” “survival,” and “recurrence.” We also reviewed reference lists of eligible studies and relevant conference proceedings from major orthopedic oncology societies to identify additional sources.

Studies were included if they reported original data on five or more patients with extremity STS and documented osseous involvement, diagnostic imaging features, surgical treatment, or clinical outcomes. Only articles published in English were included in the analysis. We excluded case reports with fewer than five patients, studies restricted to trunk or retroperitoneal sarcomas, pediatric-only cohorts, primary bone sarcomas, and narrative or systematic reviews lacking original data. While our methodology aimed to ensure a broad synthesis, we acknowledge the limitations inherent to narrative reviews, including the potential for selection bias, variability in study quality, and lack of standardized definitions for bone invasion across studies.

2.1. Prevalence and definitions of bone involvement in STS

Osseous invasion is an uncommon but clinically significant feature of soft tissue sarcomas in the extremities. Across various series, the reported prevalence of bone involvement in unselected patient populations ranges from 5 to 11 % [7]. In a large retrospective cohort of 874 patients with extremity STS, histologically confirmed bone invasion was observed in 5.5 % of cases [13], whereas another institutional analysis identified a prevalence of 11.1 % in 370 patients [10]. Bone-invasive STS tends to display more aggressive clinical characteristics, including larger tumor size, deeper anatomical location, and higher histologic grade, and is more frequently associated with synchronous metastases at the time of presentation [14,15].

However, the definition of “bone involvement” remains inconsistent across the clinical, radiologic, and pathologic domains. Clinically, persistent bone pain or focal tenderness overlying a soft tissue mass may raise suspicion of cortical invasion [16]. On MRI, key features of bone invasion include disruption of the normally hypointense cortical line on T1-weighted sequences, abnormal high signal intensity within the medullary marrow on T2-weighted or STIR sequences, and marrow enhancement after contrast administration [5,17]. Although some studies consider any cortical erosion or medullary signal abnormality as diagnostic, others require confirmation by all three imaging criteria. Notably, Elias et al. demonstrated that the combination of cortical breach, marrow signal change, and contrast enhancement yields a sensitivity and specificity approaching 100 % and 93 %, respectively, for detecting osseous invasion [5].

Pathologically, the gold standard definition of bone invasion requires histological confirmation of tumor cells infiltrating the cancellous bone or medullary cavity [18]. Tumors that merely abut bone or cause cortical scalloping without breaching the medulla may be described as “cortical abutment” or “periosteal involvement,” terms that carry less clear surgical implications. This terminological heterogeneity poses challenges for both diagnostic consistency and treatment planning [19,20]. For most surgeons, true osseous invasion, particularly medullary involvement, warrants formal bone resection to ensure negative margins [21].

To standardize terminology in this review, we used the following working definitions: cortical abutment: loss of the soft-tissue interface without cortical penetration, periosteal involvement: tumor confined to or perforating the periosteum, cortical invasion: contiguous breach of the cortex, and medullary invasion: tumor signal/enhancement within the marrow cavity [5,22]. These patterns reflect direct, contiguous extension from the soft-tissue primary tumor and are distinct from bone metastasis, which denotes hematogenous, non-contiguous skeletal seeding with histology-specific distributions [23]. MRI is preferred for suspected direct invasion. Concordant findings of cortical breach on T1, marrow hyperintensity on T2/STIR, and medullary enhancement provide high diagnostic performance, whereas histopathology remains the reference standard [5]. When contiguous invasion occurs in the extremities, the femur is most frequently affected, followed by the tibia and humerus [24,25]. In contrast, bone metastases at presentation are uncommon, but enriched in selected histotypes: alveolar soft-part sarcoma, myxoid and dedifferentiated liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma [24,26]. Given its distinct biology, staging, and treatment pathways, bone metastasis was not the subject of this study. The remainder of our review focuses on direct osseous invasion in extremity STS cases.

2.2. Clinical significance of bone invasion

The presence of bone invasion has substantial prognostic implications. Several studies have consistently shown that bone-invasive STS are associated with worse systemic outcomes. Specifically, the five-year overall survival rate for patients with bone invasion ranges from 27 % to 40 %, in contrast to 60–70 % for those without such involvement [13]. Multivariate analyses confirm that bone invasion is an independent predictor of both overall and disease-free survival [27,28].

Interestingly, some studies suggest that when adequately resected with negative margins, local recurrence rates for bone-invasive STS may not differ significantly from those of non-invasive tumors [20]. This observation implies that the poor prognosis associated with bone invasion is primarily driven by aggressive tumor biology, such as increased metastatic potential, rather than by inherent challenges in achieving local control [10]. As such, the presence of osseous involvement should prompt comprehensive systemic staging and consideration of intensified multimodal therapy, even in the absence of radiographically evident metastasis [29].

2.3. Histologic and anatomical patterns of bone invasion

Both tumor histology and anatomical site influence the likelihood of bone invasion in STS. High-grade histologic subtypes are particularly prone to osseous infiltration. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), formerly termed malignant fibrous histiocytoma, is the most common histotype associated with bone invasion, comprising approximately one-third of such cases [29]. Synovial sarcoma and leiomyosarcoma, each accounting for approximately 12–13 %, also demonstrate notable bone tropism, often due to their periarticular or vascular origins [10,30]. Less frequently, osseous invasion is observed in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) and high-grade liposarcomas [15]. In contrast, low-grade sarcomas, such as well-differentiated liposarcoma or low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, rarely demonstrate bone invasion due to their more indolent biology [19,31].

Anatomical proximity plays a similarly critical role. Tumors arising in regions with minimal soft tissue buffering, such as the foot, ankle, or anterior tibia, are disproportionately more likely to invade adjacent bone. For example, in one comparative study, 29.2 % of bone-invasive STS were located in the foot or ankle, compared to only 7.9 % of non-invasive tumors in these areas. Conversely, regions with greater soft tissue padding (e.g., gluteal or posterior thigh compartments) exhibit a lower frequency of osseous involvement [13,32].

Among long bones, the femur is most commonly affected (approximately 60 % of bone-invasive cases), followed by the tibia (18 %) and humerus (13 %) [15,20,32]. These distributions likely reflect both the frequency of sarcomas in these locations and their exposure to large, high-grade tumors. Pelvic bone invasion occurs less frequently, likely due to the deeper and more protected anatomical position of pelvic soft tissue tumors [17]. Sarcomas involving the upper extremity distal to the humerus are least likely to show bone invasion, correlating with smaller tumor sizes and less aggressive subtypes in these regions [19].

Understanding these histologic and anatomical predispositions is essential for early detection, accurate imaging interpretation, and surgical planning. High-risk zones, such as the plantar foot or anterior tibia, warrant particular vigilance and early use of advanced MRI protocols to detect subtle cortical or medullary changes [33]. In contrast, sarcomas located in more padded areas may initially spare adjacent bone, allowing for more conservative resections [34]. This nuanced understanding enables the development of tailored management strategies that optimize oncologic control while minimizing unnecessary morbidity.

2.4. Diagnostic imaging of osseous invasion

Imaging, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), plays an indispensable role in the preoperative assessment of soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) and is the cornerstone for evaluating suspected bone invasion [5]. MRI offers superior soft tissue contrast, spatial resolution, and multiplanar capability, enabling detailed evaluation of tumor extent, cortical disruption, marrow signal alteration, and peritumoral involvement [35]. Accurate differentiation between true osseous invasion and a mere bone abutment is critical for surgical decision-making, particularly when weighing the need for en bloc bone resection versus bone-sparing strategies [22,36].

2.5. MRI findings suggestive of bone invasion

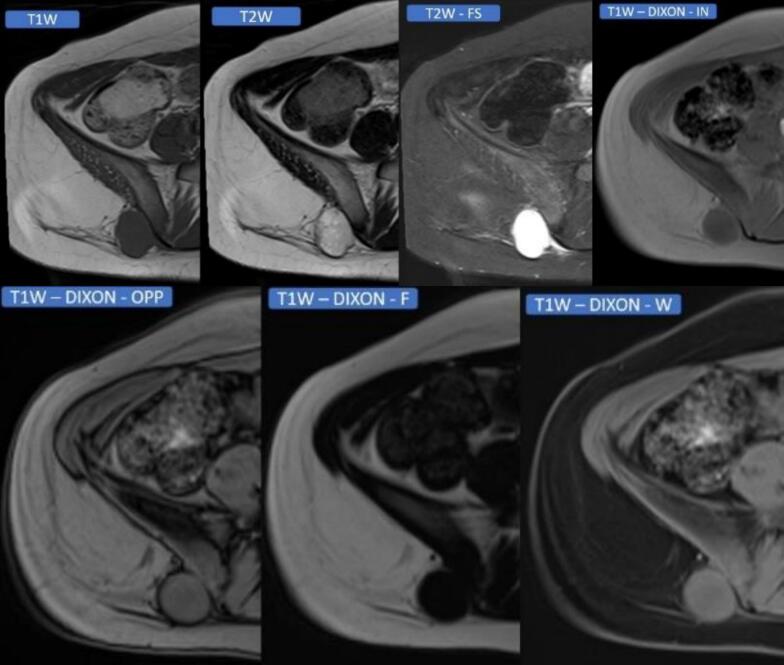

Conventional MRI sequences remain the first-line approach for local staging. In non-fat-suppressed T1-weighted images, the cortical bone appears as a continuous hypointense line [37]. Disruption or irregularity of this low-signal line, predominantly when contiguous with an adjacent mass, raises concern for cortical breach. Replacement of the normal high T1 marrow signal by intermediate or heterogeneous intensity, particularly when contiguous with the soft tissue tumor, is highly suggestive of medullary invasion [Fig. 1] [5,38].

Fig. 1.

Preoperative Axial MRI Sequences in a 15-Year-Old Female with High-Grade Myxoid Liposarcoma Adjacent to the Right Iliac Bone. T1-weighted (T1W), T2-weighted (T2W), T2-weighted fat-suppressed (T2W-FS), T1W DIXON in-phase (IN), T1W DIXON opposed-phase (OPP), T1W DIXON fat-only (F), T1W DIXON water-only (W) The mass demonstrates characteristic hyperintense T2 signal with incomplete fat suppression, consistent with myxoid liposarcoma. Critical absence of bone marrow signal abnormality on conventional sequences and advanced chemical shift imaging argued against osseous invasion. However, direct tumor abutment against the posterolateral iliac cortex prompted intraoperative concern for cortical compromise. Due to the patient's skeletal immaturity, the multidisciplinary tumor board recommended primary en bloc resection without neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Pathology following right posterior iliac hemicortical resection revealed focal transcortical invasion with microscopic medullary involvement (pT2b). Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) was delivered to the resection bed. The patient remains disease-free without evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis at 24-month surveillance.

T2-weighted or STIR sequences typically show marrow hyperintensity in areas invaded by the tumor. However, reactive bone marrow edema due to tumor proximity can also appear hyperintense, representing a diagnostic challenge [39]. Hence, STIR is highly sensitive but lacks specificity [40].

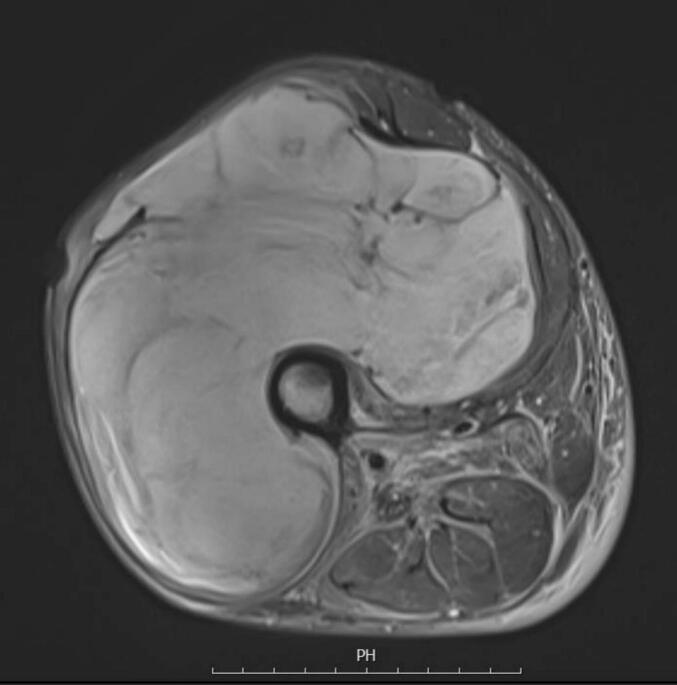

Contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences enhance diagnostic accuracy by distinguishing tumor infiltration (which typically enhances) from reactive changes (which may not). Medullary enhancement after gadolinium injection is strongly associated with true tumor invasion into the bone [Fig. 2] [41,42].

Fig. 2.

Preoperative MRI of a 42-Year-Old Male with High-Grade Myxoid Liposarcoma Demonstrating Circumferential Osseous Encasement The tumor exhibits > 270° circumferential encasement of the femoral diaphysis with critical absence of bone marrow edema, cortical disruption, or periosteal reaction on all sequences, arguing against radiologic osseous invasion. Intraoperative assessment confirmed no tumor adherence to cortical bone. The multidisciplinary tumor board recommended neoadjuvant radiotherapy followed by en bloc resection with negative margins. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered due to primary tumor size > 15 cm (pT3), high small round cell component (≥5%), and elevated metastatic risk profile. The patient remains free of local recurrence or distant metastasis at 15-month follow-up.

Several studies have demonstrated that combining these three MRI parameters, cortical disruption on T1, marrow hyperintensity on T2/STIR, and contrast enhancement on post-contrast T1, offers the highest diagnostic yield. In one surgical-pathology–correlated series, this combination provided sensitivity and specificity of 100 % and 93 %, respectively, for detecting osseous invasion [Fig. 3] [5,17].

Fig. 3.

Oncologic Management of Proximal Radius Involvement in Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma (UPS). A 29-year-old male with left anterior elbow UPS underwent neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Post-treatment imaging demonstrated progressive osseous involvement of the proximal radius. The patient subsequently received en bloc proximal radius resection with negative margins (R0).

2.6. Differentiating bone abutment vs. Invasion

Discriminating true osseous invasion from simple cortical abutment remains challenging. Tumors may displace, scallop, or thin the cortex without breaching it, and these subtle findings should be interpreted cautiously, particularly at sites prone to partial volume and motion artifacts (e.g., fibula, scapula) [43]. High-resolution MRI is the primary tool for adjudicating equivocal interfaces, with assessment focused on the continuity of the cortical low-signal line and any marrow signal/enhancement that is clearly contiguous with the soft tissue mass [44,45]. CT complements MRI by depicting fine cortical erosions/fenestrations and characterizing matrix mineralization that can refine the differential diagnosis (e.g., pointing toward a primary bone sarcoma with osteoid/chondroid matrix) [46]. In practice, CT is valuable when MRI findings at the bone–tumor interface are borderline; however, it is less sensitive to medullary invasion and should be read in conjunction with MRI and clinical context [47,48].

Another pitfall arises in assessing lesions post-neoadjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy or radiotherapy may induce inflammatory or fibrotic changes that obscure imaging features or mimic invasion. Edema and reactive sclerosis may be misinterpreted as tumor progression or invasion [[49], [50], [51]]. Therefore, imaging must be interpreted in the context of pre-treatment baseline scans and with multidisciplinary correlation.

2.7. Role of advanced imaging and quantitative MRI

Advanced MRI techniques such as diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) have emerged as promising adjuncts in evaluating osseous involvement.

DWI provides information on tissue cellularity. Tumor invasion into the marrow is associated with reduced apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, reflecting higher cell density. However, variability in methodology and artifacts from hemorrhage or necrosis can limit reliability. Low ADC values in contiguous marrow may support invasion; however, current evidence lacks consistency across large, homogeneous cohorts [44,52].

DCE-MRI, through pharmacokinetic modeling, assesses perfusion and capillary permeability. Parameters such as Ktrans and Kep have been shown to correlate with tumor grade and vascularity. High Ktrans values in the adjacent bone marrow may indicate neovascularization associated with tumor infiltration. Nonetheless, routine integration into diagnostic protocols awaits further validation [52,53].

Accurate imaging assessment of bone invasion has direct implications for both prognosis and surgical planning. Osseous involvement is associated with worse overall survival and higher-grade histology. Identification of bone invasion often necessitates en-bloc resection to achieve negative margins. Conversely, if imaging confidently excludes medullary involvement, bone-sparing approaches such as subperiosteal or hemicortical resection may be feasible, preserving limb function without compromising oncologic safety.

2.8. Recommendations for imaging protocols

A standardized MRI protocol for assessing bone invasion in soft tissue sarcomas (STS) should include axial and coronal T1-weighted images without fat suppression, as well as T2-weighted or STIR sequences to evaluate edema and marrow involvement. Additionally, fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequences following gadolinium administration are essential. Optional sequences such as diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) may be considered, particularly in equivocal or high-risk cases. Radiologic reports should clearly describe cortical integrity, the presence or absence of marrow signal changes, and the enhancement characteristics of the affected area. The use of structured reporting templates is recommended to enhance consistency and support surgical teams in planning appropriate resection strategies [Table 1] [[54], [55], [56]].

Table 1.

MRI findings for Diagnosing Osseous Invasion.

| MRI Feature | Description | Diagnostic Value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical breach [5] | Disruption of low-signal cortex on T1-weighted images | Suggestive of cortical invasion | High | Moderate |

| Marrow signal change [5,33] | High STIR/T2 signal and low T1 in adjacent marrow | Suggests medullary involvement | Moderate | Low |

| Gadolinium enhancement [5,17] | Enhancement of bone marrow following contrast injection | Supports true invasion | High | High |

2.9. Surgical management and reconstruction in bone-invasive STS

Wide excision with negative (R0) margins remains the surgical standard for STS with osseous involvement. Operative strategy spans composite en-bloc bone resection to limb-sparing, bone-preserving techniques, tailored to tumor extent, anatomic site, histologic grade, and expected function. In selected patients, conservative approaches are oncologically acceptable when margin control is meticulous [16,20,34]. For tumors with extensive cortical contact (≥ two-thirds circumference), intraoperative assessment of tumor mobility is pivotal [13,28]: a mobile tumor generally permits subperiosteal resection, with the intact periosteum functioning as an anatomic barrier [9]. Where tumors abut critical structures (bone or neurovascular bundles), planned close margins may be an acceptable compromise when paired with appropriate adjuvant therapy [57].

Surgical planning was performed using a multimodal pathway. Patients at a high risk of close/positive margins or major functional loss with upfront surgery may benefit from neoadjuvant therapy to reduce target volumes and clarify planes around bone and neurovascular structures, with decisions made in a specialist sarcoma MDT [58]. Preoperative radiotherapy is most commonly employed, and systemic therapy is considered for chemosensitive histology or in clinical trials [59]. After neoadjuvant treatment, the operative objective remains R0 (or planned close), with acceptable morbidity. When medullary invasion is excluded and the tumor is mobile along the cortex, bone-sparing resection is preferred; proven cortical/medullary invasion or fixation to the bone favors composite en bloc resection [16].

2.10. Segmental vs. Bone-Sparing (hemicortical resection)

When periosteal involvement or simple cortical abutment is present, that is, no cortical breach or medullary signal change on MRI, a bone-sparing approach is appropriate. Subperiosteal resection along the periosteal sleeve provides oncologic adequacy. Some authors have also cauterized the exposed cortex to reduce microscopic periosteal seeding [10,27]. Adjuvant radiotherapy may be used selectively after a multidisciplinary review (e.g., planned close margins, adverse histology, and complex planes) [58].

Conversely, cortical destruction with or without medullary invasion favors composite en bloc bone resection (partial hemicortical or segmental), with reconstruction tailored to the defect size, site, and expected load. If preoperative findings are equivocal, intraoperative assessment of cortical integrity and tumor mobility along the cortex should guide the choice; a truly mobile tumor without medullary involvement supports bone-sparing resection, whereas fixation to the bone or credible concern for medullary spread argues for a composite approach [19]. Notably, in tumors with cortical contact but no medullary invasion, composite bone resection does not improve local control or survival versus subperiosteal excision but worsens postoperative function; therefore, bone resection should be reserved for confirmed invasion rather than prophylactically [54].

Segmental (en bloc) resection remains the traditional strategy when imaging or intraoperative findings confirm a cortical or medullary invasion. It achieves high local control, with R0 margins in > 90 % of cases; however, morbidity is substantial, infection rates up to 30 %, prosthetic complications, and prolonged rehabilitation, with moderate functional outcomes (typical MSTS 60–75 %) [10,21,46].

Hemicortical resection, in which only a portion of the cortex is removed, represents a middle ground for select low-grade or focally aggressive tumors. This method facilitates structural preservation and joint integrity, with reconstructive strategies typically involving cement augmentation or cortical allografts. Although the evidence remains limited to smaller series, early results suggest favorable oncologic and functional outcomes [60,61].

In contrast, subperiosteal resection, preserving the bone by dissecting the tumor of the cortical surface, is gaining traction for cases without cortical breach on MRI. This technique has demonstrated low rates of microscopic bone invasion (6 %) and local recurrence (16 %), comparable to more extensive procedures, with functional outcomes often superior due to joint and bone preservation. Successful implementation requires surgical precision, intraoperative frozen section analysis, and execution in high-volume, specialized centers [16,20].

Margin Status and Oncologic Considerations Achieving negative margins is the principal determinant of local control and long-term survival in bone-invasive STS. R1 resections, especially in high-grade tumors, significantly elevate recurrence risk. While re-excision or adjuvant radiation can be considered in certain low-grade cases, complete resection of the involved periosteum or cortex remains the gold standard [16,62].

Recent data indicate that MRI-based assessment of periosteal involvement aligns well with histopathology. When the periosteum appears radiologically uninvolved and is confirmed intraoperatively, it may be safely preserved [5,20]. In borderline cases, a wider resection should be pursued following intraoperative frozen section guidance and multidisciplinary discussion [22,63].

2.11. Reconstruction and functional recovery

Reconstructive decisions after bone resection are dictated by the size and anatomical site of the defect. For extensive diaphyseal or periarticular resections, endoprosthetic replacement is commonly utilized, offering immediate skeletal stability and early ambulation. MSTS scores in such patients typically range between 70–80 %, although mechanical complications, loosening, and infection are ongoing concerns [15,21].

In contrast, when bone integrity is preserved via subperiosteal or hemicortical resection, reconstruction may be unnecessary or limited to cementation or allograft filling [64]. These conservative approaches facilitate faster recovery, higher MSTS scores (often 80–90 %), and reduced long-term complication rates. Importantly, patients undergoing joint-preserving procedures tend to resume preoperative functional levels more rapidly, particularly when neuromuscular units remain intact [16,65].

Functional recovery is influenced by a confluence of factors, including age, baseline fitness, the extent of neurovascular dissection, and adjuvant therapies [19]. Segmental resections followed by prosthetic reconstruction typically restore independent ambulation within 3–6 months, although high-demand activities may be permanently limited [16]. Conversely, bone-sparing surgeries can yield near-normal function within weeks to a few months [27]. Long-term functional success is strongly correlated with preserved joint mechanics, reduced surgical morbidity, and avoidance of extensive soft tissue damage [Table 2] [21].

Table 2.

Summary of Key Studies on Bone Invasion in Soft-Tissue Sarcomas.

| Study | N | Site | MRI Features Used | Surgery Type | 5-year Survival | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferguson et al.[13] | 874 | Extremities | T1 + contrast | Segmental | 40 % | Large retrospective cohort |

| Elias et al.[5] | 60 | Extremities | T1 + T2 + CE | Various | Not reported | Imaging-path correlation study |

| García-Ortega et al.[10] | 370 | Extremities | T1, STIR, contrast | Segmental | 27–40 % | Confirmed prognostic role of bone invasion |

| Yan et al.[14] | 92 | Lower limb | T1 + STIR | Endoprosthetic | 35 % | Focused on juxta-articular involvement |

| Lin et al.[20] | 86 | Mixed | T1 only | Periosteal margin-based | Not reported | Defined periosteal-safe margins |

2.12. Controversies and future directions

Clinical Significance and Prognostic Impact Osseous invasion in extremity soft tissue sarcomas (STS) represents a biologically aggressive phenotype with significant implications for treatment planning and prognosis. Although bone involvement is observed in approximately 5–11 % of extremity STS cases, its presence is associated with larger tumor size, deeper tissue location, higher histological grade, and an increased metastatic risk [10,13]. Several studies, including large institutional cohorts, confirm that bone invasion independently predicts worse overall and disease-free survival, with five-year survival rates ranging from 27 % to 40 %, compared to 60 % to 70 % in patients without bone involvement [10]. Importantly, this poor prognosis appears to reflect systemic disease progression more than compromised local control, as local recurrence rates may remain similar between bone-invasive and non-invasive tumors when managed with appropriate surgical strategies [13,16]. Moreover, data from advanced/metastatic cohorts suggest that bone metastases carry an independently adverse prognosis, reinforcing the hypothesis that osseous involvement, whether local invasion or distant spread, reflects underlying tumor aggressiveness [24].

Diagnostic Challenges and Solutions: Identifying true bone invasion preoperatively is critical for surgical planning, but it remains diagnostically challenging due to the lack of standardized criteria. Clinical symptoms, such as focal bony pain or cortical tenderness, may suggest cortical involvement; however, radiological imaging, particularly MRI, plays a central role. Key MRI indicators include cortical disruption on T1-weighted images, marrow signal changes on STIR or T2 sequences, and contrast enhancement within bone [5,36]. However, the specificity and sensitivity of these findings vary, and radiographic interpretations can differ across centers. In particular, interobserver variability in MRI interpretation remains a significant issue, and the sensitivity for detecting medullary involvement is reduced when contrast-enhanced sequences are not utilized [19,51]. Periosteal reactions or abutments are often misinterpreted as cortical invasion on imaging. As highlighted by a recent series, the true cortical breach must be differentiated from periosteal adherence, as the latter may not necessitate en bloc resection (Periosteal margin) [27]. Histopathologic confirmation of tumor cells within cancellous bone remains the gold standard but is typically unavailable preoperatively. In practice, the combination of imaging findings and intraoperative assessment, sometimes supported by frozen section analysis, guides the extent of bone resection.

The surgical approach to osseous-invasive STS must strike a balance between oncologic control and functional preservation. Historically, en bloc bone resection has been the standard approach when cortical or medullary invasion is confirmed, resulting in high rates of R0 resection. However, this approach carries significant morbidity, including infection, prosthetic complications, and prolonged rehabilitation, and functional outcomes are often moderate [29]. Emerging evidence supports the selective use of bone-sparing techniques such as subperiosteal or hemicortical resections in cases with no medullary involvement. These techniques offer superior functional outcomes, particularly in preserving joint mechanics and mobility, without compromising local control in carefully selected patients [16,22]. Achieving negative margins remains paramount, and the choice of resection must be guided by a multidisciplinary review and tailored to tumor behavior, anatomical constraints, and patient expectations. Interestingly, some recent data suggest that bone resections may be more extensive than necessary, particularly when cortical contact is misinterpreted as medullary invasion. In such cases, bone-sparing procedures may offer oncologic equivalence with superior functional preservation [16].

Despite advances, several questions remain unanswered. Consensus is lacking on the definition of bone invasion, optimal MRI criteria, and the threshold for bone resection. A recent systematic review of imaging protocols found marked inconsistencies in how osseous invasion is defined and diagnosed across institutions, reinforcing the need for consensus guidelines to improve comparability and clinical decision-making [45]. Prospective, multicenter studies are needed to validate radiological criteria and assess the outcomes of conservative surgical approaches across histological subtypes. Biomarkers predictive of bone invasion or metastatic potential could further refine risk stratification. Technological advancements in imaging and intraoperative navigation may enhance the accuracy of defining tumor extent. Additionally, optimizing multimodal strategies, including the timing and role of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, requires further investigation, especially in patients with borderline resectable tumors.

This review is limited by the narrative design, which may introduce selection bias and restrict reproducibility. Included studies exhibit significant heterogeneity in definitions, imaging protocols, surgical techniques, and outcome measures. Moreover, many data are drawn from retrospective cohorts at high-volume centers, which may limit their generalizability. The lack of standardized criteria for defining osseous invasion across studies poses a particular challenge in synthesizing evidence. Nonetheless, this review provides a structured appraisal of current knowledge and highlights critical gaps for future research.

In summary, bone invasion in extremity STS is not a uniform entity, it spans a range of clinical, biological, and radiologic manifestations. Its presence signals a need for heightened vigilance, more nuanced imaging interpretation, and careful surgical planning. While radical resections may not always be necessary, they should not be abandoned prematurely in the absence of high-quality evidence. Balancing oncologic rigor with functional preservation requires individualized, multidisciplinary care informed by both current evidence and emerging insights.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, osseous invasion in extremity STS is a rare but clinically significant manifestation that necessitates a thoughtful, multidisciplinary approach. It often signals aggressive tumor biology and thus requires comprehensive management, including surgery, systemic therapy, and, when appropriate, radiation. Fortunately, with contemporary imaging and surgical innovations, limb-sparing strategies are frequently feasible without compromising oncologic results. Moving forward, key challenges include standardizing definitions, such as MRI criteria for bone resection, and establishing evidence-based guidelines for surgical margins and adjuvant therapy. Prospective multicenter research is crucial for resolving these uncertainties and refining care strategies. Until such data become available, individualized treatment planning guided by multidisciplinary collaboration remains the cornerstone of care. The ultimate goal is to achieve oncologic control while preserving function and quality of life, even in this high-risk subset of patients with sarcoma.

Research location

Joint Reconstruction Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran and Bone and Joint Reconstruction Research Center, Department of Orthopedics, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Ethical approval

The Tehran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee confirmed that ethical approval was not required for this review.

Funding declaration

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its supplementary materials. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Seyyed Saeed Khabiri: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Khalil Kargar Shooroki: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology. Sadegh Saberi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. Hamed Naghizadeh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Informed Consent

The authors affirmed that all imaging modalities (including X-rays and MRIs) presented in this article were used with informed consent from the patient. All identifying information was eliminated to ensure complete anonymity.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.von Mehren M., Kane J.M., Agulnik M., et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2022;20(7):815–833. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renn A., Adejolu M., Messiou C., et al. Overview of malignant soft-tissue sarcomas of the limbs. Clin. Radiol. 2021;76(12) doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2021.08.011. 940. e1-940. e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenblatt M., Remotti F. Diagnostic Challenges. Springer; Frozen Section Pathology: 2021. Frozen Sections in Bone and Soft Tissue Pathology; pp. 333–382. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya S, Bhattacharya A. Pre-Operative Evaluation of Soft Tissue Sarcoma. In: Abdul Hamid G, ed. Soft Tissue Sarcoma and Leiomyoma - Diagnosis, Management, and New Perspectives. IntechOpen; 2024.

- 5.Elias D.A., White L.M., Simpson D.J., et al. Osseous invasion by soft-tissue sarcoma: assessment with MR imaging. Radiology. 2003;229(1):145–152. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albano D., Cazzato R.L., Sconfienza L.M. Springer; 2023. Bone and Soft Tissues. Multimodality Imaging and intervention in Oncology; pp. 383–417. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panicek D.M., Go S.D., Healey J.H., Leung D.H., Brennan M.F., Lewis J.J. Soft-tissue sarcoma involving bone or neurovascular structures: MR imaging prognostic factors. Radiology. 1997;205(3):871–875. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter B.K., Hwang P.F., Forsberg J.A., et al. Impact of margin status and local recurrence on soft-tissue sarcoma outcomes. JBJS. 2013;95(20):e151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittenberg S., Paraskevaidis M., Jarosch A., et al. Surgical margins in soft tissue sarcoma management and corresponding local and systemic recurrence rates: a retrospective study covering 11 years and 169 patients in a single institution. Life. 2022;12(11):1694. doi: 10.3390/life12111694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Ortega D.Y., Álvarez-Cano A., Clara-Altamirano M.A., et al. Bone invasion in soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities: an underappreciated prognostic factor. Bone invasion in soft tissue sarcomas. Surg. Oncol. 2022;40 doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2021.101692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeller J., Kiefer J., Braig D., et al. Efficacy and safety of microsurgery in interdisciplinary treatment of sarcoma affecting the bone. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:1300. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanathan R.C., A’Hern R., Fisher C., Meirion J.T.T. Prognostic index for extremity soft tissue sarcomas with isolated local recurrence. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2001;8:278–289. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0278-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson P.C., Griffin A.M., O'Sullivan B., et al. Bone invasion in extremity soft-tissue sarcoma: impact on disease outcomes. Cancer. 2006;106(12):2692–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantidakis G., Litière S., Gelderblom H., et al. Prognostic significance of bone metastasis in soft tissue sarcoma patients receiving palliative systemic therapy: an explorative, retrospective pooled analysis of the EORTC-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (STBSG) database. Sarcoma. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/5815875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan T.-Q., Zhou W.-H., Guo W., et al. Endoprosthetic reconstruction for large extremity soft-tissue sarcoma with juxta-articular bone involvement: functional and survival outcome. J. Surg. Res. 2014;187(1):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu H., Wang K., Shi C., et al. Does composite bone resection for soft-tissue sarcoma with cortical contact result in better local control and survival compared to sub-periosteal dissection?: a comparative retrospective cohort study. Bone Joint Open. 2025;6(2):215–226. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.62.BJO-2024-0057.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eissa O., Tabashy R., Shoman S., Nadji M. Accuracy of MR imaging in diagnosis of bone invasion by soft tissue sarcomas: experience at NCI, Cairo Egypt. European Congress of Radiology-ECR. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher S.M., Joodi R., Madhuranthakam A.J., Öz O.K., Sharma R., Chhabra A. Current utilities of imaging in grading musculoskeletal soft tissue sarcomas. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016;85(7):1336–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel N.M., Streitbürger A., Hardes J., et al. Indications and clinical outcomes in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma attached to the bone receiving tumorendoprosthetic replacement after tumor resection. Arch. Orthopaedic Trauma Surg. 2025;145(1):179. doi: 10.1007/s00402-024-05735-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin P.P., Pino E.D., Normand A.N., et al. Periosteal margin in soft‐tissue sarcoma. Cancer: Interdisciplinary Int. J. Am. Cancer Soc. 2007;109(3):598–602. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowell P.D., Nevin J.L., Novak R., Tsoi K.M., Ferguson P.C., Wunder J.S. In: Orthopedic Surgical Oncology for Bone Tumors : A Case Study Atlas. Özger H., Sim F.H., Puri A., Eralp L., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2022. Prosthetic Reconstruction for Soft Tissue Sarcomas with Bone Involvement; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merino-Rueda L.R., Barrientos-Ruiz I., Bernabeu-Taboada D., et al. Radiological and histopathological assessment of bone infiltration in soft tissue sarcomas. Eur. J. Orthopaedic Surg. Traumatol. 2022;32(4):631–639. doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-03018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincenzi B., Frezza A.M., Schiavon G., et al. Bone metastases in soft tissue sarcoma: a survey of natural history, prognostic value and treatment options. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2013;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Younis M., Summers S., Pretell-Mazzini J. Bone metastasis in extremity soft tissue sarcomas: risk factors and survival analysis using the SEER registry. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2022;106(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s12306-020-00673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretell-Mazzini J., Seldon C.S., D'Amato G., Subhawong T.K. Musculoskeletal metastasis from soft-tissue sarcomas: a review of the literature. JAAOS-J. Am. Acad. Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2022;30(11):493–503. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshikawa H., Ueda T., Mori S., et al. Skeletal metastases from soft-tissue sarcomas: incidence, patterns, and radiological features. J. Bone Joint Surg. British Vol. 1997;79(4):548–552. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b4.7372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung Y.-G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Soft Tissue Tumors: Changes Challenges and Strategies. Springer; 2025. Soft Tissue Sarcoma with Osseous Invasion; pp. 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsukushi S., Nishida Y., Urakawa H., Kozawa E., Ishiguro N. Prognostic significance of histological invasion in high grade soft tissue sarcomas. Springerplus. 2014;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura T., Sakai T., Tsukushi S., et al. Clinical outcome in patients with high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma receiving prosthetic replacement after tumor resection of the lower extremities: tokai musculoskeletal oncology consortium study. Vivo. 2023;37(6):2642–2647. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel D.B., Matcuk G.R., Jr Imaging of soft tissue sarcomas. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2018;7(4):35. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.07.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Indap S., Dasgupta M., Chakrabarti N., Agarwal A. Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (Evans tumour) of the arm. Indian J. Plastic Surg.: Off. Publ. Assoc. Plastic Surgeons India. 2014;47(2):259–262. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.138973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toğral G., Güngör B.Ş. Management of suspected cases of soft tissue sarcoma, bone invasion: 16 Case Study. Acta Oncol Tur. 2019;52:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaya M., Wada T., Nagoya S., et al. MRI and histological evaluation of the infiltrative growth pattern of myxofibrosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:1085–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donnell P.W., Griffin A.M., Eward W.C., et al. The effect of the setting of a positive surgical margin in soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Genet. 2014;120(18):2866–2875. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scalas G., Parmeggiani A., Martella C., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft tissue sarcoma: features related to prognosis. Eur. J. Orthopaedic Surg. 2021;31(8):1567–1575. doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-03003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crombé A., Marcellin P.-J., Buy X., et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas: assessment of MRI features correlating with histologic grade and patient outcome. Radiology. 2019;291(3):710–721. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Igrec J., Fuchsjäger M.H. Imaging of bone sarcomas and soft-tissue sarcomas. Georg Thieme Verlag KG. 2021:1171–1182. doi: 10.1055/a-1401-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aparisi Gómez M.P., Righi A., Errani C., et al. Inflammation and infiltration: can the radiologist draw a line? MRI versus CT to accurately assess medullary involvement in parosteal osteosarcoma. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 2020;35(1_suppl):31–36. doi: 10.1177/1724600819900516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto T., Hitora T., Marui T., et al. Reimplantation of autoclaved or irradiated cortical bones invaded by soft tissue sarcomas. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(6B):3685–3690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodden J., Neumann J., Rasper M., et al. Diagnosis of joint invasion in patients with malignant bone tumors: value and reproducibility of direct and indirect signs on MR imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2022;32(7):4738–4748. doi: 10.1007/s00330-022-08586-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subhawong T.K., Jacobs M.A., Fayad L.M. Insights into quantitative diffusion-weighted MRI for musculoskeletal tumor imaging. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014;203(3):560–572. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shamsuddeen R. Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences (India); 2018. Assessment of the Role of Different MRI Sequences and Contrast in determining Tumor Margins in Musculoskeletal Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C., Lin J., Men Y., Yang W., Mi F., Li L. Does medullary versus cortical invasion of the mandible affect prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma? J. Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2017;75(2):403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahlawat S., Fritz J., Morris C.D., Fayad L.M. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers in musculoskeletal soft tissue tumors: review of conventional features and focus on nonmorphologic imaging. J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2019;50(1):11–27. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pennington Z., Ahmed A.K., Cottrill E., Westbroek E.M., Goodwin M.L., Sciubba D.M. Systematic review on the utility of magnetic resonance imaging for operative management and follow-up for primary sarcoma—lessons from extremity sarcomas. Ann. Trans. Med. 2019;7(10):225. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.01.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serban B., Cretu B., Cursaru A., Nitipir C., Orlov-Slavu C., Cirstoiu C. Local recurrence management of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. EFORT Open Rev. 2023;8(8):606–614. doi: 10.1530/EOR-23-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aga P., Singh R., Parihar A., Parashari U. Imaging spectrum in soft tissue sarcomas. J. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;2:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s13193-011-0095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Group ESESNW. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25:iii102-iii112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Hwang S., Lefkowitz R., Landa J., et al. Local changes in bone marrow at MRI after treatment of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0560-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vijayakumar G., Jones C.M., Supple S., Meyer J., Blank A.T. Radiation osteitis: incidence and clinical impact in the setting of radiation treatment for soft tissue sarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2023;52(9):1747–1754. doi: 10.1007/s00256-023-04338-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X., Jacobs M.A., Fayad L. Therapeutic response in musculoskeletal soft tissue sarcomas: evaluation by MRI. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(6):750–763. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crombé A., Matcuk G.R., Fadli D., et al. Role of imaging in initial prognostication of locally advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Acad. Radiol. 2023;30(2):322–340. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ledoux P., Kind M., Le Loarer F., et al. Abnormal vascularization of soft-tissue sarcomas on conventional MRI: diagnostic and prognostic values. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019;117:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miwa S., Otsuka T. Practical use of imaging technique for management of bone and soft tissue tumors. J. Orthop. Sci. 2017;22(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riley G.M., Steffner R., Kwong S., Chin A., Boutin R.D. MRI of soft-tissue tumors: what to include in the report. J. Radio. Graph. 2024;44(6) doi: 10.1148/rg.230086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bloem JL, Vriens D, Krol AD, et al. Therapy-related imaging findings in patients with sarcoma. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.; 2020:676-691. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Öztürk R. Indication and surgical approach for reconstruction with endoprosthesis in bone-associated soft tissue sarcomas: appropriate case management is vital. World J. Clin. Cases. 2024;12(12):2004. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i12.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qu G., Tian Z., Wang J., Yang C., Niu X., Yao W. Preoperative sequential chemotherapy and hypofractionated radiotherapy combined with comprehensive surgical resection for high-risk soft tissue sarcomas: a retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2024;14 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1423151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salerno K.E., Alektiar K.M., Baldini E.H., et al. Radiation therapy for treatment of soft tissue sarcoma in adults: executive summary of an ASTRO clinical practice guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2021;11(5):339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Savvidou O.D., Goumenos S., Trikoupis I., et al. Oncological and functional outcomes after hemicortical resection and biological reconstruction using allograft for parosteal osteosarcoma of the distal femur. Sarcoma. 2022;2022(1) doi: 10.1155/2022/5153924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakamura T., Fujiwara T., Tsuda Y., et al. The clinical outcomes of hemicortical extracorporeal irradiated autologous bone graft after tumor resection of bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(10):5605–5610. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kainhofer V., Smolle M., Szkandera J., et al. The width of resection margins influences local recurrence in soft tissue sarcoma patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;42(6):899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Endo M., Lin P.P. Surgical margins in the management of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2018;7(4):37. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.08.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bus M., Bramer J., Schaap G., et al. Hemicortical resection and inlay allograft reconstruction for primary bone tumors: a retrospective evaluation in the Netherlands and review of the literature. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2015;97(9):738–750. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ogato S. Complications of bone and soft tissue sarcoma patients following limb salvage and amputation procedures. Spark Repository. 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its supplementary materials. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.