Abstract

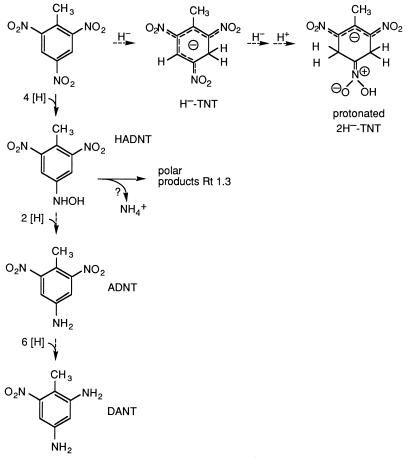

Because of its high electron deficiency, initial microbial transformations of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) are characterized by reductive rather than oxidation reactions. The reduction of the nitro groups seems to be the dominating mechanism, whereas hydrogenation of the aromatic ring, as described for picric acid, appears to be of minor importance. Thus, two bacterial strains enriched with TNT as a sole source of nitrogen under aerobic conditions, a gram-negative strain called TNT-8 and a gram-positive strain called TNT-32, carried out nitro-group reduction. In contrast, both a picric acid-utilizing Rhodococcus erythropolis strain, HL PM-1, and a 4-nitrotoluene-utilizing Mycobacterium sp. strain, HL 4-NT-1, possessed reductive enzyme systems, which catalyze ring hydrogenation, i.e., the addition of a hydride ion to the aromatic ring of TNT. The hydride-Meisenheimer complex thus formed (H−-TNT) was further converted to a yellow metabolite, which by electrospray mass and nuclear magnetic resonance spectral analyses was established as the protonated dihydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT (2H−-TNT). Formation of hydride complexes could not be identified with the TNT-enriched strains TNT-8 and TNT-32, or with Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−), for which such a mechanism has been proposed. Correspondingly, reductive denitration of TNT did not occur.

2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) is one of the most common explosives. Although synthesis reached its maximum during World War II, high concentrations of TNT and its congeners are still found in soil and groundwater at former manufacturing sites, indicating significant resistance to microbial metabolism (32). The strong electron-withdrawing character of the nitro group renders the π system of nitroarenes electron deficient with increasing number of nitro substituents; consequently, nitroarenes become less and less susceptible to electrophilic attack by oxygenases (32). Several reports deal with the oxidative degradation of mono- and dinitroarenes (34), whereas for the degradation of trinitroarenes, such as picric acid (2,4,6-trinitrophenol) or TNT, initial oxidative attack of the aromatic ring has not been described so far.

Several studies on fungal degradation of TNT have established a certain extent of mineralization, since 14CO2 was evolved from [14C]TNT (3, 22, 37). Unequivocal evidence for complete and productive degradation of TNT by bacteria is still lacking. Several reports deal with the bacterial conversion of TNT, mainly to 2-amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene and the isomeric 4-amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene (2- and 4-ADNT), under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (1, 6, 8, 21, 24–26); under aerobic conditions, these metabolites are regarded as dead-end products which are not further degraded.

A novel reductive-degradation mechanism by an aerobic organism has been reported for the utilization of picric acid by Rhodococcus erythropolis HL PM-1 (17). An orange-red hydride-Meisenheimer complex, formed by nucleophilic addition of a hydride ion in the 3 position of picric acid (32), transiently accumulated in the culture fluid. Subsequent elimination of nitrite from this complex, restoring the aromatic system, yielded 2,4-dinitrophenol. Formation of a hydride-Meisenheimer complex was confirmed for TNT cometabolism also: resting cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1, pregrown with 4-nitrotoluene, converted TNT by hydride addition at C-3 to the respective Meisenheimer complex (H−-TNT) (38). Duque et al. (6) suggested, by reason of analogy, that a corresponding mechanism operates in TNT degradation by Pseudomonas sp. clone A but did not present firm evidence. Reductive elimination of nitrite with subsequent rearomatization to dinitrotoluene—analogous to the mechanism found for picric acid—would represent an effective pathway for TNT breakdown as well, since 2,4-dinitrotoluene and 2,6-dinitrotoluene have been shown to be biodegradable (28, 35). Such reductive “denitration” of TNT was proposed for Pseudomonas sp. clone A (6). In the present study, the significance of this pathway was examined with Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) and two newly isolated strains, TNT-8 and TNT-32. The formation and fate of the H−-TNT complex with respect to the elimination of nitrite were examined with Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1 and R. erythropolis HL PM-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enrichment and isolation of bacterial strains with TNT.

Mixed samples of TNT-contaminated soil from a former manufacturing site at Hessisch-Lichtenau, Germany, and activated sludge from a sewage plant in Stuttgart-Büsnau, Germany, were used as inocula. Cultivations were carried out in 100 ml of nitrogen-free mineral medium (18) supplemented with a saturated TNT solution (overall concentration, 1 or 2 mM) as the nitrogen source and a mixture of glucose, fructose, succinate, and acetate (3 mM each) as the carbon source. When the turbidity of the culture had increased significantly, and high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis showed a substantial decrease in TNT concentration, a 10-ml aliquot of the suspension was transferred into 100 ml of fresh medium. For isolation of pure cultures, samples of the enrichment cultures were plated on solid mineral media with TNT and the carbon source mixture given above; additionally, 0.2% nutrient broth (NB) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) was added. The strains thus isolated were tested for their ability to utilize TNT as a nitrogen source by monitoring of growth and TNT conversion in batch culture. The gram-negative strain TNT-8 and the gram-positive strain TNT-32, classified by suspending cells in KOH (9), were used in further studies.

Other organisms.

Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1, isolated with 4-nitrotoluene as the sole nitrogen source (36), was shown to cometabolically reduce TNT to ADNTs and the hydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT (38). R. erythropolis HL PM-1 is a 2,4-dinitrophenol-utilizing strain which by spontaneous mutation has acquired the ability to utilize picric acid (17). Pseudomonas sp. clone A is a derivative of Pseudomonas sp. strain C1S1, which was isolated with TNT as the sole source of nitrogen. 2,4-Dinitrotoluene, 2,6-dinitrotoluene, and 2-nitrotoluene were reported as alternative nitrogen sources (6). Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) is a spontaneous mutant of C1S1 which has lost the ability to grow with 2-nitrotoluene (30).

Culture conditions and measurement of growth.

Strains were cultivated in fluted Erlenmeyer flasks in mineral medium (18) containing succinate (10 mM) as the carbon source and containing 0.5 mM 4-nitrotoluene (for Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1), picric acid (for R. erythropolis HL PM-1), or TNT (for strains TNT-8 and TNT-32) as the nitrogen source. Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) was grown with fructose (10 mM) as the carbon source and TNT (0.5 mM) as the nitrogen source. The cultures were incubated at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm; growth was monitored photometrically by measuring the turbidity at 546 nm (spectrophotometer model DU-50; Beckman Instruments, Munich, Germany). In cases of colored metabolites or substrates, the culture fluid was centrifuged and the cell-free supernatant was used as a reference. Solid media were prepared by adding 1.5% (wt/vol) agar (no. 1; Oxoid Ltd., London, United Kingdom) to the mineral medium, supplemented with 10 mM succinate as the carbon source and 0.5 mM picric acid (for R. erythropolis HL PM-1) or 0.3 mM TNT [for strains TNT-8 and TNT-32 and for Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−)] as the nitrogen source. TNT-containing agar plates were supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) NB; in our experience this reduces the accumulation of brown polymerization products. For cultivation of Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1, 4-nitrotoluene was supplied through the gas phase in a desiccator containing crystals of 4-nitrotoluene.

Resting-cell experiments.

Cells were grown in mineral medium with the corresponding nitroarene (0.5 mM) or ammonia (2 mM) as the nitrogen source and succinate or fructose as the carbon source (see above). Fully induced cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1 and R. erythropolis HL PM-1 were obtained by adding the respective nitroarene substrate (final concentration, 0.5 mM) during the exponential-growth period, 2 h before the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cells were suspended in phosphate buffer (50 mM; pH 7.4) and incubated with H−-TNT or a mixture of 2-hydroxylamino-4,6-dinitrotoluene and 4-hydroxylamino-2,6-dinitrotoluene (2- and 4-HADNT) at 30°C on a water bath shaker. For turnover experiments with TNT, the substrate was incubated in phosphate buffer prior to the addition of cells. Upon the addition of the cells to the TNT solution, the TNT concentration was reduced rapidly, indicating initial adsorption of TNT on the cell surfaces. Desorption of TNT could be demonstrated when the cells were resuspended in phosphate buffer. Turnover of the substrate was monitored by HPLC. Experiments under anaerobic conditions were performed in serum bottles closed with gas-tight rubber septa in an argon atmosphere.

Preparation of cell extracts.

Cells of the individual bacterial strains (see above) were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 3 to 5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and disrupted by using a French pressure cell (Amicon, Silver Spring, Md.). Cell debris and membrane-bound proteins were removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 35 min at 4°C (L8-70 ultracentrifuge; Beckman Instruments Inc., Irvine, Calif.). The protein content of the crude extracts was determined as described by Bradford (2).

Analytical methods.

The nitrite ion concentration in the culture fluid was determined photometrically by the method of Griess-Ilosvay as modified by Shinn (23), or alternatively by ion chromatography. The system incorporated a conductivity detector with suppressor technique, an IonPac AS4A column (4 by 250 mm), and an AG4A precolumn (4 by 50 mm), each filled with 15-μm latex particles (diameter, 180 nm), with alkanol quaternary ammonium as functional groups (Dionex, Idstein, Germany), and was run with 1.8 mM Na2CO3–1.7 mM NaHCO3 as mobile phase at a flow rate of 2 ml/min.

Ammonium ion concentrations were estimated photometrically by the Berthelot method as modified by Parsons et al. (29).

Concentrations of TNT, of the isomeric HADNTs (2- and 4-HADNT) and ADNTs (2- and 4-ADNT), and of H−-TNT were quantified by ion pair HPLC as described previously (38). 2- and 4-HADNT, as well as 2- and 4-ADNT, were not separated under these conditions and thus were each quantified as the sum of both isomers.

Flow injection mass spectra were obtained on a Trio 2000 mass spectrometer (MS) (Fison Instruments, Altrincham, United Kingdom) by negative-mode electrospray ionization (ESI−), with a needle voltage of −2.8 kV and a source temperature of 150°C. The sample was dissolved in acetonitrile and injected into the flow system; the acetonitrile/water/formic acid ratio was 850:150:1 (vol/vol/vol), and the flow rate was 0.1 ml/min.

Liquid chromatography (LC)-ESI mass spectra were obtained on an HP1090 LC system with a diode array detector, coupled directly to a Platform II mass spectrometer (Micromass UK Ltd., Altrincham, United Kingdom): LC column Capital octyldecyl silane (inside diameter, 150 by 4.6 mm), mobile phase acetonitrile:water:PicA (175:325:10), isocratic at 1 ml/min (split to 200 μl/min before entering the MS source). The MS was scanned from m/z 40 to 500 in 1 s and was calibrated with NaI-CsI injected separately. A 25-V cone voltage was used throughout the analyses. For working with nonvolatile buffers and ion pair reagents, the platform was fitted with an X-flow counterelectrode. MS and diode array data were acquired simultaneously and evaluated with MassLynx NT software.

1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of the yellow metabolite were obtained with an ARX 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany) at nominal frequencies of 500.13 and 125.77 MHz, respectively. The samples were dissolved in D2O (99.9% d).

Isolation and characterization of the yellow metabolite.

Resting cells of R. erythropolis HL PM-1 were used to accumulate the yellow metabolite during conversion of H−-TNT. These cells were obtained by growth in mineral medium (3× 1,000 ml in 3-liter fluted Erlenmeyer flasks) with picric acid (0.5 mM) as the nitrogen source and succinate (10 mM) as the carbon source. Cells were harvested, washed twice, resuspended in distilled water instead of buffer (optical density [OD] at 546 nm, 4 to 5), and incubated at 30°C with the H−-TNT tetramethylammonium salt (0.5 mM), obtained by chemical synthesis (see below). During conversion of the H−-TNT complex, the culture fluid turned from dark red to orange yellow. When HPLC analysis showed complete transformation of the H−-TNT complex, cells were removed by centrifugation and filtration, and the cell-free culture fluid was extracted with ethyl acetate to remove by-products, such as TNT, 2- and 4-HADNT, and 2- and 4-ADNT. The ethyl acetate extract was discarded, residual ethyl acetate in the yellow-water phase was removed by evaporation under reduced pressure, and the aqueous phase, containing the yellow metabolite as a tetramethylammonium salt, was concentrated and subjected to ultrafiltration (with a 5-kDa filter) to remove high-molecular-mass components. The solution was then shock frozen and lyophilized, yielding a red powder which could be stored under argon at −20°C for several weeks without decomposition. The tetramethylammonium salt of the yellow metabolite was employed directly for ESI-MS and NMR analysis. In order to eliminate the very intensive tetramethylammonium signal, especially in the 1H NMR spectra, an aliquot of the tetramethylammonium salt was converted to the sodium salt with a Dowex MSC-1 ion-exchange resin (20/50 mesh; particle size, 0.9 to 0.3 mm; Serva, Heidelberg, Germany).

Chemicals.

Highly pure TNT was generously supplied by T. Rosendorfer (MBB Deutsche Aeorospace, Schrobenhausen, Germany). The hydride-Meisenheimer complex was synthesized chemically from TNT according to the method of Kaplan and Siedle (15) as described previously (38). A mixture of 2- and 4-HADNT was prepared enzymatically from TNT as described by Michels and Gottschalk (22) and was separated in part by thin-layer chromatography (22) in order to obtain standards. 2,4-Dihydroxylamino-6-nitrotoluene was kindly supplied by P. Fiorella (Armstrong Laboratory, Tyndall Air Force Base, Fla.).

RESULTS

Growth of bacterial strains enriched with TNT as a nitrogen source.

In order to clarify whether reductive elimination of nitrite via formation of a hydride-Meisenheimer complex has a key function in TNT metabolism, two newly isolated strains, TNT-8 and TNT-32, and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) were studied in greater detail. When strain TNT-8 pregrown with NB was inoculated into mineral medium with TNT as the sole nitrogen source and succinate as the sole carbon and energy source, TNT disappeared completely within 3 days, with a concomitant increase in cell density (ΔOD at 546 nm, 1.8). After two transfers into fresh medium, growth as well as TNT consumption slowed down; for the second growth cycle, a ΔOD at 546 nm of 0.35 was observed within 4 days; for the third growth cycle, a ΔOD of 0.3 was observed within 6 days. The higher increase in cell density during the first growth cycle obviously resulted from a carryover of nitrogen from NB, as shown in a control experiment (first transfer, ΔOD = 1.6; second transfer, ΔOD = 0.1; third transfer, ΔOD = 0.05). Furthermore, upon prolonged cultivation with TNT, the culture fluid turned a characteristic dark yellow to brownish red. The same phenomenon was observed with strain TNT-32 and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) when they were grown with TNT as the sole nitrogen source. While NB-pregrown cells of Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−), inoculated in mineral medium with TNT as the sole nitrogen source, showed good growth and fast consumption of TNT, both growth and TNT conversion were retarded during successive subcultivation. At the same time, increasing agglomeration of the cells was observed. Whereas strain TNT-8 and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) could be subcultivated with TNT as the sole nitrogen source, growth at the expense of TNT by strain TNT-32 could not be accomplished during long-term subcultivation.

In order to test whether growth was inhibited by TNT or its metabolites, cells were inoculated in mineral medium containing ammonia (2 mM) as a nitrogen source and succinate or fructose as a carbon and energy source (10 mM each), and cultures with and without added TNT (0.5 mM) were compared. Whereas growth curves of the gram-positive strain TNT-32 and of Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) were not affected by TNT, pronounced inhibition of the gram-negative strain TNT-8 was noticed at ≥0.1 mM concentrations of TNT.

Initial metabolites of TNT with TNT-enriched strains.

Resting cells of strains TNT-8 and TNT-32, subcultivated with TNT and succinate after growth with NB, showed no turnover activity. Highly active cells were obtained, however, when strains TNT-8 and TNT-32 were grown with ammonia and succinate and TNT was added 3 to 4 h before harvesting. Interestingly, a nonspecific release of ammonia was observed upon incubation of these cells in pure buffer, i.e., without any substrate. Thus, it cannot be decided whether ammonia is also eliminated during the breakdown of TNT. A comparable release of previously accumulated ammonia has likewise been reported for a Pseudomonas putida strain (40).

Release of nitrite through ring hydrogenation and rearomatization of an intermediate hydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT, as described for picric acid (17), was never observed in significant amounts with resting cells of TNT-8, TNT-32, or Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−). Likewise, dinitro- and nitrotoluenes could not be identified as denitration products upon incubation of growing or resting cells of strain TNT-32 or Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) with TNT. Only trace amounts of H−-TNT had been detected in a culture of strain TNT-8 growing with TNT as the sole nitrogen source (38). During incubation of the H−-TNT complex with resting cells or cell extracts of TNT-8, TNT-32, or Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−), neither dinitrotoluenes nor nitrotoluenes were formed and the amount of nitrite detected by HPLC was negligible.

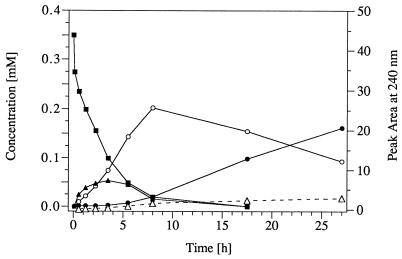

During conversion of TNT by resting cells of strain TNT-32, three major metabolites successively appeared in the culture fluid (Fig. 1). A single HPLC peak, observed first, was due to an unresolved mixture of isomeric HADNTs. By comparison of the chromatographic properties and UV-visible (UV/VIS) absorption spectra with those of authentic material, the metabolites were identified as 2- and 4-HADNT. The isomeric HADNTs were further reduced by strain TNT-32 to the corresponding ADNTs (2- and 4-ADNT), which under aerobic conditions underwent even further reduction to 2,4-diamino-6-nitrotoluene (2,4-DANT). Accumulation of nitrite in the culture fluid was negligible. After 27 h, 0.35 mM TNT had been converted into 0.1 mM 2- and 4-ADNT and 0.16 mM 2,4-DANT.

FIG. 1.

Conversion of TNT by resting cells of strain TNT-32. Cells were obtained by growth in mineral medium with ammonia (2 mM) and succinate (10 mM) prior to addition of TNT (0.5 mM). The cells were harvested, washed, resuspended in phosphate buffer (OD at 546 nm, 6.8), and incubated at 30°C with 0.35 mM TNT on a water bath shaker. Concentrations of TNT (▪), isomeric HADNTs (▴), ADNTs (○), and 2,4-diamino-6-nitrotoluene (•), as well as the peak area of the not-yet-identified metabolite(s) Rt 1.3 (▵), were determined by HPLC.

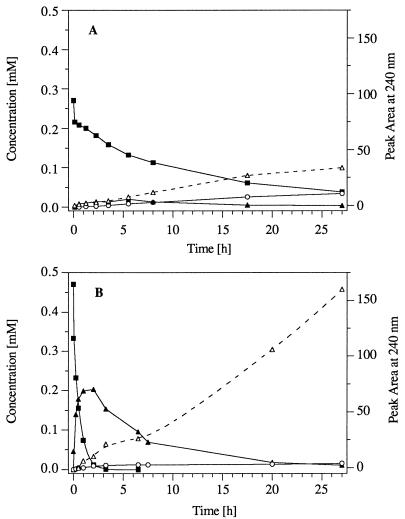

Resting cells of strain TNT-8 and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) likewise converted TNT to the 2- and 4-HADNT mixture. In contrast to strain TNT-32, these strains accumulated only minor amounts of the isomeric ADNTs (Fig. 2). Rather, a new elution peak at Rt 1.3 min (λmax, 263 nm [HPLC analysis]) revealed formation of an unknown metabolite(s). Within 27 h, strain TNT-8 converted 0.24 mM TNT to only 0.025 mM 2- and 4-ADNT (10%); the major percentage of the substrate seemed to be diverted into the alternate metabolic route. This was even more pronounced with resting cells of Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−): while 0.47 mM TNT was rapidly reduced to a mixture of 2- and 4-HADNT (Σ ≤ 0.2 mM), only 0.01 mM 2- and 4-ADNT were accumulated after complete conversion of the HADNTs. This again indicates that the bulk of TNT is converted to the polar product(s) Rt 1.3. No other metabolites could be detected by HPLC in significant amounts in the culture fluids for both strains.

FIG. 2.

Conversion of TNT by resting cells of strain TNT-8 (A) and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) (B). Resting cells were obtained by growth in mineral medium containing succinate or fructose (10 mM each) and ammonia (2 mM) prior to the addition of TNT (0.5 mM). Cells were harvested, washed, resuspended in phosphate buffer (OD at 546 nm, 5 or 5.2, respectively), and incubated at 30°C with 0.27 and 0.47 mM TNT, respectively, on a water bath shaker. Concentrations of TNT (▪), the isomeric HADNTs (▴), and ADNTs (○), as well as the peak area of the not-yet-identified metabolite(s) Rt 1.3 (▵), were determined by HPLC.

When strain TNT-8 or Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) was incubated with a mixture of authentic 2- and 4-HADNT, these substrates were likewise converted to the Rt 1.3 product(s). The UV maximum at 263 nm indicated that the structure was still aromatic. By comparing chromatographic and UV spectral characteristics with those of authentic material, 2,4-dihydroxylamino-6-nitrotoluene was excluded as a possible structure for the polar metabolite (7). 2- and 4-ADNT were detected only in minor amounts, as in the turnover experiments with TNT, accounting for 10% of the 2- and 4-HADNT turned over by strain TNT-8 and for 5% of that turned over by Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) (39). The product Rt 1.3 was also formed under anaerobic conditions by both strains, indicating that its formation occurred without the contribution of oxygen.

Formation of hydride complexes of TNT.

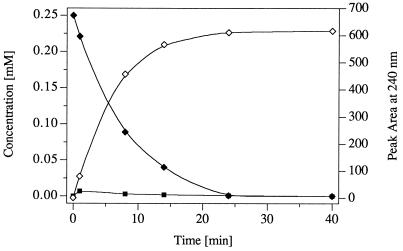

R. erythropolis HL PM-1 utilizes picric acid (2,4,6-trinitrophenol) as a nitrogen source via a reductive mechanism: a hydride ion is added to the aromatic nucleus, and the resulting hydride-Meisenheimer complex of picric acid is then converted to 2,4-dinitrophenol, with concomitant release of nitrite (17). In contrast, TNT was not denitrated reductively and did not serve as a growth substrate for R. erythropolis HL PM-1. Rapid development of a yellow color in the culture fluid, however, clearly indicated transformation of TNT. As analyzed by HPLC, picric acid-grown cells converted TNT, by nitro-group reduction, to products such as 2- and 4-HADNT (12%) and 2- and 4-ADNT (2%). An additional prominent metabolite was characterized by a deep yellow color (λmax, 267 and 445 nm). Uninduced cells converted TNT only after a lag phase. A transiently accumulating red metabolite was identified as the hydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT (H−-TNT) by comparison of its chromatographic properties and the UV/VIS spectrum with those of an authentic compound (λmax, 255, 477, and 578 nm) (15, 38). When synthetic H−-TNT served as a substrate for induced cells of R. erythropolis HL PM-1, it was converted into the yellow metabolite within 25 min (Fig. 3). Only 3% of the H−-TNT complex spontaneously rearomatized to TNT; thus, only trace amounts of the respective reduction products, 2- and 4-ADNT and 2- and 4-HADNT, were generated (<0.4% each). This indicates that conversion of TNT into the yellow metabolite by induced cells of R. erythropolis HL PM-1 was so fast that the intermediate H−-TNT was not released into the culture fluid.

FIG. 3.

Turnover of the hydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT (H−-TNT) by resting cells of R. erythropolis HL PM-1. Resting cells were obtained by growth in mineral medium with picric acid (0.5 mM) and succinate (10 mM). The cells were harvested, washed, resuspended in phosphate buffer (OD at 546 nm, 10), and incubated with the H−-TNT complex (0.25 mM) at 30°C on a water bath shaker. H−-TNT (⧫) was rapidly converted to a yellow product, Rt 3.3 (◊), so that spontaneous decomposition to TNT (▪) was negligible.

Conversion of the H−-TNT complex was also studied with resting cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1. This 4-nitrotoluene-degrading strain likewise did not grow with TNT as a nitrogen source but unequivocally formed H−-TNT from TNT, in addition to 4-ADNT and other metabolites previously designated Rt 6.7 and Rt 3.3 according to the respective retention times in HPLC analysis (38). The product Rt 6.7 was identified as 4-HADNT by comparison with an enzymatically synthesized sample. Product Rt 3.3 had the same UV/VIS spectrum as the yellow metabolite formed by cells of R. erythropolis HL PM-1 from either TNT or H−-TNT (see above). Actually, when 4-nitrotoluene-grown cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain HL 4-NT-1 were incubated with H−-TNT, the same yellow product, Rt 3.3, was formed as the predominant metabolite (39). As observed with R. erythropolis HL PM-1, only traces of TNT, 4-HADNT, and 4-ADNT were detected (about 1% each).

Isolation and preliminary characterization of the yellow metabolite.

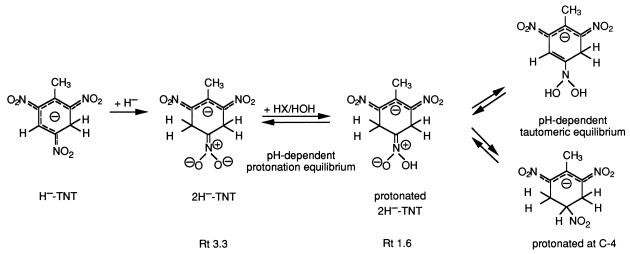

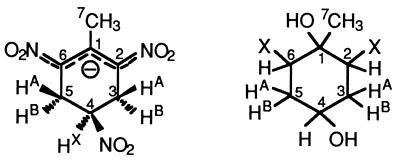

Because of its ionic structure, the yellow metabolite could not be extracted with organic solvents. A new method with buffer-free conditions had to be developed for its production, isolation, and purification (see Materials and Methods). HPLC analysis of the red powder obtained upon lyophilization showed an additional peak at Rt 1.6, which gave a slightly different UV/VIS absorption spectrum (λmax, 230, 268, and 430 nm) than the original metabolite (Rt 3.3; λmax, 267 and 445 nm). The same peak had already been observed in chromatograms of the aqueous reaction mixture. The ratio of the two peaks displayed a clear pH dependence; the corresponding structures must be prototropic forms of the same metabolite (Fig. 4, tautomeric equilibrium). The protonated form (Rt 1.6) dominated under acid conditions (pH ≤6), whereas the deprotonated yellow metabolite (Rt 3.3) prevailed at pHs of ≥8.

FIG. 4.

Formation of a protonated dihydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT from H−-TNT.

Structural characterization of the yellow metabolite.

The first MS analysis (flow injection with ESI−-MS) had shown three prominent signals at 46, 183, and 230 Da which could be assigned, respectively, as nitrite ion, molecular anion (e.g., the hydride-Meisenheimer complex of dinitrotoluene), and the corresponding HNO2 adduct. When, however, a solution of the yellow metabolite was subjected to coupled HPLC–ESI−-MS, i.e., after chromatographic separation, these three signals once again dominated the mass spectrum; hence, they must arise directly from the yellow metabolite. The signal at m/z 230 in fact corresponds to the molecular anion [M·]− of a protonated dihydride-Meisenheimer complex of TNT (2H−-TNT). This ion then eliminates either nitrite or nitric acid, giving rise to the negative fragment ions at m/z 46 [NO2]− and m/z 183 [M-HNO2]−, respectively. With this structure for the yellow metabolite, it becomes clear why only trace amounts of nitrite could be found in the supernatant even after complete conversion of H−-TNT to the yellow metabolite. Rather than eliminating a nitrite ion, the H−-TNT complex undergoes a second hydride attack followed by protonation of the resulting dihydride-Meisenheimer complex (2H−-TNT), as shown in Fig. 4.

The proposed structure for the yellow metabolite, that of a tetrabutylammonium salt, of the dihydride-Meisenheimer complex protonated at C-4 was established (Fig. 4) unequivocally by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. The integrity of the sample, subjected to the individual NMR techniques, was verified in each case by HPLC analysis directly before the respective measurements. The 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, D2O, 293 K) shows a heptuplet at 5.219 ppm and two doublets of doublets at δ 3.566 and 3.178 ppm (Table 1). This resonance pattern can be analyzed, in a straightforward manner, as an (AB)2X five-spin system. The resonances at δ 3.566 and 3.178 ppm are assigned to the double set of diastereotopic methylene protons HA and HB at C-3 and -5, i.e., at those positions where hydride has been added. The large numerical value for the geminal coupling constant 2J (HA, HB) of −17.6 Hz clearly proves the bisected orientation of the >CHAHB fragment with respect to the plane of the O2N—C6—C1—C2—NO2 π system (14). Almost identical vicinal coupling constants are derived from the methylene subspectrum between HA and HB on one side and the HX proton on the other side (4.7 and 4.9 Hz) (Table 1); the HX resonance thus appears as a genuine heptuplet (a separation in the spectrum corresponding to an apparent coupling constant [Japp] equal to 4.7 Hz). Both this splitting and the resonance position at δ 5.219 ppm are in good agreement with the proposed structure [e.g., 2-nitropropane: δ (2H) 4.44 ppm] (14). Finally, a methyl singlet (δ 2.461 ppm, 3H) shows that the TNT CH3 group is still present in the metabolite as analyzed here. Both the resonance position and the lack of 3J splitting definitely prove that the CH3 group is bound to an sp2 carbon, i.e., that hydride addition is exclusively in the 3,5 position, and hence prove the structure given in Table 1. The 13C NMR spectrum of the yellow salt shows the expected 1:1:1 triplet for the N(CH3)4 cation (δ = 57.88 ppm), arising from coupling with the I = 1 nuclear spin of 14N, a CH2 and CH3 resonance (δ = 33.24 and 20.91 ppm; relative intensity, 2:1), and also two signals for quaternary sp2 carbon atoms (δ = 142.57 and 133.16 ppm, also with a 2:1 relative intensity). The assignments as CH3, CH2, and =C carbon have been verified with a 13C, 1H correlation spectrum with distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT).

TABLE 1.

1H and 13C NMR data for the yellow product

| Parameter | Proposed structure and data for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Yellow metabolitea | Hydrolysis product | |

|

||

| X = NO2 or OH (or other tautomeric forms) | ||

| δ (1H) (ppm)b | ||

| 3,5-HA | 3.566 | 3.657 |

| 3,5-HB | 3.178 | 3.561 |

| 4-HX | 5.219 | 3.784 |

| 1-CH3 | 2.461 | 2.473 |

| J (Hz) | ||

| HA, HB | (−) 17.6 | (−) 11.7 |

| HA, HX | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| HB, HX | 4.9 | 6.6 |

| HA/HB, CH3 | 1.0 | |

| δ (13C) (ppm) | ||

| C-7 | 20.91 | 20.38 |

| C-3,5 | 33.24 | 32.22 |

| C-2,6 | 133.16 | |

| C-1 | 142.57 | |

The sample was dissolved in D2O for measurement. Under these conditions, i.e., without any buffer, the yellow metabolite is protonated at C-4.

1H chemical shifts are converted to the TMS scale with δ(H2O) equal to 4.82 ppm.

Even the first 1H NMR traces, however, taken immediately upon the dissolving of the sample in D2O, show the presence of a second structure. In the course of 24 h, the respective signals more or less replace all resonances of the primary yellow metabolite. The new product again comprises a CH3 resonance (δ = 2.473 ppm, i.e., slightly less shielded than in the primary product), as well as a  substructure. This new five-spin system is characterized, however, by a geminal coupling with a drastically reduced numerical value (−11.7 instead of −17.6 Hz) and a different set of 3J (HA, HX) and 3J (HB, HX) coupling constants (Table 1). The connectivities within this five-proton subset have been proven independently, as for the primary metabolite, by an H,H correlation (COSY) spectrum. A tentative proposal for the structure of the decomposition product would be that of a hydrolysis product (Table 1). With the time required for 13C NMR measurements, the signals for the decomposition product dominate the spectrum (Table 1); they clearly prove, however, that the

substructure. This new five-spin system is characterized, however, by a geminal coupling with a drastically reduced numerical value (−11.7 instead of −17.6 Hz) and a different set of 3J (HA, HX) and 3J (HB, HX) coupling constants (Table 1). The connectivities within this five-proton subset have been proven independently, as for the primary metabolite, by an H,H correlation (COSY) spectrum. A tentative proposal for the structure of the decomposition product would be that of a hydrolysis product (Table 1). With the time required for 13C NMR measurements, the signals for the decomposition product dominate the spectrum (Table 1); they clearly prove, however, that the  subsystem is still intact in this structure also.

subsystem is still intact in this structure also.

DISCUSSION

Enrichment under nitrogen-limiting conditions may facilitate the selection of bacteria that release nitrite or ammonia by partial degradation of polynitroaromatic substrates such as picric acid or TNT. The initial formation of a hydride-Meisenheimer complex and subsequent elimination of nitrite, as observed with the picric acid-utilizing R. erythropolis HL PM-1, could not be demonstrated for the TNT-enriched bacteria investigated here. This is in contrast to what has been published by Duque et al. (6). Neither their Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) nor any of our own TNT-enriched isolates generated H−-TNT. Correspondingly, cells grown in the presence of TNT could not denitrate or convert the H−-TNT complex. Instead of the proposed dinitrotoluenes as products of reductive denitration, only metabolites of TNT with one or two nitro groups reduced were identified as dead-end products. According to Duque et al. (6) and Haïdour and Ramos (11), Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) should also denitrate 2,4-dinitrotoluene and accumulate 2-nitrotoluene. Resting cells of Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) exhibited only very low activities with 2,4-dinitrotoluene, and the corresponding hydroxylaminonitrotoluenes and aminonitrotoluenes were the only detectable metabolites. Therefore, from the present data, hydride addition and subsequent nitrite elimination, i.e., reductive denitration, could not be identified as a key reaction in TNT-enriched bacteria.

Growth of strains TNT-8 and TNT-32 and of Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) was attenuated with each transfer into fresh medium. This would argue against productive utilization of TNT as a nitrogen source by these strains. Restricted growth with TNT could also be due, however, to the formation of dead-end metabolites which accumulate in the course of TNT transformation. Part of these metabolites, obviously, are subject to facile chemical oxidation; the respective oxidation products are retained by the cells, which take on the characteristic red-brown coloration. This misrouting is even more evident during cultivation of these organisms on TNT-containing agar plates. Particularly, colonies of strain TNT-8 turn dark brown upon prolonged incubation. HADNTs have been identified as inhibitory species during TNT reduction by Phanerochaete chrysosporium (3, 22) and by the bacterial strains investigated here. The development of the characteristic coloration in growing cultures of TNT-metabolizing strains had also been observed by other authors (1, 8, 26). They concluded that reactive intermediates of TNT catabolism polymerize to dark, insoluble macromolecules which were reported to be associated with the lipid and protein fractions of microorganisms (4). Products of reductive biotransformation of TNT or 2,4-dinitrotoluene were found to react with sugars to form glucuronides and with carboxylic acids to form amides (5, 20). HADNT, for instance, formed covalently bonded protein adducts when [14C]TNT was incubated with rat liver microsomes and NADPH (19). Formation of these protein adducts depended on the oxygen content of the atmosphere. Nitrosoaminodinitrotoluenes, as the first intermediates of HADNT oxidation, react smoothly with proteins and thus could inhibit growth of TNT-metabolizing strains. The inhibitory potential, i.e., toxicity, of TNT itself seems to be of minor importance; rather, the diverse metabolic misroutings of TNT observed in this study and the toxic effects of metabolites which are incorporated into the cells seem to be the major barriers to the utilization of TNT.

Although the data from the TNT-enriched organisms TNT-8 and TNT-32 rule out the mechanism of reductive elimination of nitrite, it remains obscure at which metabolic stage and in which form assimilable nitrogen is made available to the bacterial cells. In recent years, a considerable number of reports have been published on the role of hydroxylamino derivatives as key intermediates for the elimination of ammonia from nitroaromatic compounds (10, 12, 27, 31, 33, 36). Release of ammonia from such hydroxylamino intermediates has not yet been reported for TNT metabolism. HADNTs are transformed not only into the corresponding ADNTs but also into, e.g., 2,4-dihydroxylamino-6-nitrotoluene (7, 16). Recently, it has been observed that this metabolite is enzymatically converted to 2-amino-5-hydroxy-4-hydroxylamino-6-nitrotoluene by a Clostridium sp. strain (13). Hence, HADNTs and the yet unidentified highly polar metabolites described above may play an important role in the productive breakdown of TNT (Fig. 5). Therefore, the possibility exists that the TNT-enriched strain TNT-8 and Pseudomonas sp. clone A (2NT−) may utilize TNT as a nitrogen source via reductive metabolism of the nitro groups.

FIG. 5.

Initial reductive reactions in the aerobic metabolism of TNT. Dashed arrows indicate dead-end routes.

Since nitrite release from the H−-picric acid complex has been well established (17, 32), we have now tested whether this mechanism also operates with TNT in R. erythropolis HL PM-1 and Mycobacterium sp. HL 4-NT-1. These organisms cannot utilize TNT as a nitrogen source but do form the H−-TNT (described here for the first time as the C-4 protonated form) complex. This complex, however, is further reduced to a yellow metabolite which has been identified by its spectroscopic data as the protonated 3,5-dihydride complex of TNT (2H−-TNT) (Fig. 5). Unlike the H−-picric acid complex, the corresponding TNT complex undergoes neither nitrite elimination nor rearomatization to 2,4- or 2,6-dinitrotoluene under physiological conditions. Successive transfer of two hydride ions instead of only one is observed also with picric acid (17). This route of dihydride complex formation is unproductive for the catabolism of both TNT and picric acid. The productive degradation of picric acid is characterized by the fact that reduction of nitro groups, which in the case of TNT gives rise to extensive metabolic misrouting, does not occur with picric acid in R. erythropolis HL PM-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge J. Rebell and T. Schlöffel for the NMR, F. Streit and M. Schiebel for the ESI−, and A. J. Hudson (Micromass UK Ltd.) for the LC-ESI− measurements. J. L. Ramos generously supplied a mutant of strain Pseudomonas sp. clone A. Finally, we are very grateful to C. M. Vogel for her support in facilitating this research project as well as C. Vorbeck’s stay at the Armstrong Laboratory on Tyndall AFB.

This work was sponsored by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Air Force Systems Command USAF, under grant AFOSR-91-0237.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boopathy R, Manning J, Montemagno C, Kulpa C. Metabolism of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by a Pseudomonas consortium under aerobic conditions. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bumpus J A, Tatarko M. Biodegradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by Phanerochaete chrysosporium: identification of initial degradation products and the discovery of a TNT metabolite that inhibits lignin peroxidase. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter D F, McCormick N G, Cornell J H, Kaplan A M. Microbial transformation of 14C-labeled 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene in an activated-sludge system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:949–954. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.5.949-954.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Channon H J, Mills G T, Williams R T. The metabolism of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (α-T.N.T.) Biochem J. 1944;38:70–85. doi: 10.1042/bj0380070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duque E, Haïdour A, Godoy F, Ramos J L. Construction of a Pseudomonas hybrid strain that mineralizes 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2278–2283. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2278-2283.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorella P D, Spain J C. Transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes JS 52/45. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2007–2015. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.2007-2015.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funk S B, Roberts D J, Crawford D L, Crawford R L. Initial-phase optimization for bioremediation of munition compound-contaminated soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2171–2177. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2171-2177.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregersen T. Rapid method for distinction of Gram-negative from Gram-positive bacteria. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1978;5:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groenewegen P E J, De Bont J A M. Degradation of 4-nitrobenzoate via 4-hydroxylaminobenzoate and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate in Comamonas acidovorans. Arch Microbiol. 1992;158:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haïdour A, Ramos J L. Identification of products resulting from the biological reduction of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, 2,4-dinitrotoluene, and 2,6-dinitrotoluene by Pseudomonas sp. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:2365–2370. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haigler B E, Spain J C. Biodegradation of 4-nitrotoluene by Pseudomonas sp. strain 4NT. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2239–2243. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2239-2243.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes, J. (Rice University). Personal communication.

- 14.Jackmann L M, Sternhell S. Applications of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in organic chemistry. 1969. p. 164. , 273–275. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan L A, Siedle A R. Studies in boron hydrides. IV. Stable hydride Meisenheimer adducts. J Org Chem. 1971;36:937–939. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan T A, Bhadra R, Hughes J. Anaerobic transformation of 2,4,6-TNT and related nitroaromatic compounds by Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;18:198–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenke H, Knackmuss H-J. Initial hydrogenation during catabolism of picric acid by Rhodococcus erythropolis HL 24-2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2933–2937. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2933-2937.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenke H, Pieper D H, Bruhn C, Knackmuss H-J. Degradation of 2,4-dinitrophenol by two Rhodococcus erythropolis strains, HL 24-1 and HL 24-2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2928–2932. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2928-2932.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung K H, Yao M, Stearns R, Chiu S-H L. Mechanism of bioactivation and covalent binding of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. Chem Biol Interact. 1995;97:37–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)03606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormick N G, Cornell J H, Kaplan A M. Identification of biotransformation products from 2,4-dinitrotoluene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:945–948. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.5.945-948.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick N G, Feeherry F E, Levinson H S. Microbial transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and other nitroaromatic compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;31:949–958. doi: 10.1128/aem.31.6.949-958.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michels J, Gottschalk G. Inhibition of the lignin peroxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium by hydroxylamino-dinitrotoluene, an early intermediate in the degradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:187–194. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.187-194.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery H A C. The determination of nitrite in water. Analyst. 1961;86:414–416. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naumova R P, Amerkhanova N N, Shaikhutdinov V A. Study of the first stage of the conversion of trinitrotoluene under the action of Pseudomonas denitrificans. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol. 1979;15:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naumova R P, Selivanovskaya S Y, Cherepneva I E. Conversion of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene under conditions of oxygen and nitrate respiration of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 1989;24:409–413. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumeier W, Haas R, von Löw E. Mikrobieller Abbau von Nitroaromaten aus einer ehemaligen Sprengstoffproduktion. Forum Städte-Hyg. 1989;40:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishino S F, Spain J C. Degradation of nitrobenzene by a Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2520–2525. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2520-2525.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishino S F, Spain J C. Abstracts of the 96th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1996. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Degradation of 2,6-dinitrotoluene by bacteria, abstr. Q-380; p. 452. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons T R, Maita Y, Lalli C M. A manual of chemical and biological methods for seawater analysis. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1984. pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos, J. L. (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Estación Experimental del Zaidín, Granada, Spain). Personal communication.

- 31.Rhys-Williams W, Taylor S C, Williams P A. A novel pathway for the catabolism of 4-nitrotoluene by Pseudomonas. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1967–1972. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rieger P-G, Knackmuss H-J. Basic knowledge and perspectives on biodegradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and related nitroaromatic compounds in contaminated soil. In: Spain J C, editor. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenzle A, Lenke H, Fischer P, Williams P A, Knackmuss H-J. Catabolism of 3-nitrophenol by Ralstonia eutropha JMP 134. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1421–1427. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1421-1427.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spain J C. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:523–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spanggord R J, Spain J C, Nishino S F, Mortelmans K E. Biodegradation of 2,4-dinitrotoluene by a Pseudomonas sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3200–3205. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3200-3205.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiess, T., F. Desiere, P. Fischer, J. C. Spain, H.-J. Knackmuss, and H. Lenke. A novel degradative pathway of 4-nitrotoluene by a Mycobacterium sp. strain. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Stahl J D, Aust S D. Metabolism and detoxification of TNT by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:477–482. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vorbeck C, Lenke H, Fischer P, Knackmuss H-J. Identification of a hydride-Meisenheimer complex as a metabolite of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by a Mycobacterium strain. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:932–934. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.932-934.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vorbeck C. Untersuchungen zur Rolle reduktiver Initialreaktionen im aeroben mikrobiellen Metabolismus von 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluol (TNT). Ph.D. dissertation. Stuttgart, Germany: Universität Stuttgart; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeyer J, Kearney P C. Degradation of o-nitrophenol and m-nitrophenol by a Pseudomonas putida. J Agric Food Chem. 1984;32:238–242. [Google Scholar]