Abstract

Introduction

Prolonged exposure to stress may lead to low mood, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and metabolic disorders. Ashwagandha, an established adaptogen, is known to combat stress. We studied the safety and efficacy of Ashwagandha formulation, Zenroot™ (ZEN), containing 1.5% total withanolides on stress, anxiety, mood, and sleep quality in human subjects with non-chronic mild to moderate stress.

Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled, clinical interventional study with supplementation duration of 84 days. Ninety subjects were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive 125 mg of ZEN or placebo. We measured stress using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) score as a primary endpoint. Various secondary endpoints included Mindfield eSense Skin Response (SCR) and Mindfield eSense PULSE Heart Rate Variability (HRV)–Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD), and standard deviation of normal NN interval (SDNN), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Profile of Mood States (POMS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), stress biomarkers of serum cortisol, and salivary alpha amylase (sAA) levels and safety parameters. The study assessments were performed on days 0, 14, 28, 56, and 84.

Results

All 90 randomized subjects completed the study. Mean ± standard error (SE) age of subjects in the ZEN group was 35.5 ± 1.3 years and in the placebo group was 34.5 ± 1.2 years. ZEN 125 mg showed significant (p < 0.05) improvements in PSS, BAI, and PSQI scores on days 28, 56, and 84; SCR on days 14, 28, and 84 and trend (p < 0.1) on day 56; HRV-RMSSD and SDNN on day 14; and POMS on days 56 and 84. No significant differences were observed between the two groups for serum cortisol and sAA. The study product was well tolerated without any safety concerns.

Conclusion

We observed significant reductions in both subjective and objective measures of stress with improvement in mood, sleep quality, and occasional anxiety symptoms. ZEN was well tolerated without any related adverse events. Future clinical studies are warranted to evaluate the effect of ZEN on chronically stressed adults.

Clinical Trial Registration Number: http://ctri.nic.in/Identifier:CTRI/2024/03/063786.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-025-03327-z.

Keywords: Stress, Anxiety, Mood, Ashwagandha, Zenroot™, Withanolides, Sleep quality

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Prolonged stress leads to serious health issues like depression, insomnia, and cardiac diseases. Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) is a natural adaptogen with proven stress-relief properties. Around 25–40% of the global population reports insomnia symptoms linked to stress and mood disturbances. |

| This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of Zenroot™ (ZEN), containing 1.5% total withanolides, in reducing stress, anxiety, mood disturbances, and sleep issues in individuals experiencing non-chronic mild to moderate stress. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| ZEN supplementation significantly reduced both subjective and objective measures of stress. Improvements were observed in mood, sleep quality, and anxiety symptoms. At a 125-mg dose, ZEN reduced perceived stress and alleviated related symptoms. |

| ZEN supplementation supported relaxation by balancing systemic stress responses toward parasympathetic activation and was well tolerated, with no reported adverse effects. |

Introduction

Mood, anxiety, stress, and insomnia are intricately connected and affects day-to-day life of adults [1]. Stress is faced by everyone from different sources such as jobs, friends, family, pollution, etc. Stress arises from physical and psychological overload and impacts the sleep/wake cycle with associated sleep disorders. Sleep is critical for healthy living and plays a vital role in cognitive function, emotional regulation, physical health, and quality of life [2]. Prolonged exposure to stress leads to conditions like depression, insomnia, high blood pressure, cardiac diseases, and metabolic disorders [3–5].

Insomnia is a health problem associated with difficulty in falling asleep, waking early, and disturbed and poor sleep quality. Poor-quality sleep may result in health conditions such as fatigue, irritability, and impaired concentration and focus. Cortisol secreted during stress through activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis also impacts physical and mental health. Anxiety and depression, which are associated with poor sleep or insomnia, are further exacerbated by stress [1, 6, 7]. About 25–40% of the world population reports insomnia symptoms attributed to stress and depressed moods [8].

Adaptogens are medicinal plants that normalize physiological processes of the body and help to adapt to changes during increased stress level by modulating cortisol and neurotransmitter systems. Ashwagandha, botanically known as Withania somnifera, is a well-known adaptogen in traditional medicine having anti-oxidant, anxiolytic, antidepressant, neuroprotective, and cognitive enhancing properties [9]. Ashwagandha contains steroidal lactones known as withanolides that include withanoside IV and V, withanolide A–D, withanone, and withaferin-A and are responsible for many of pharmacological activities of Ashwagandha [10]. Further, Ashwagandha extract also contains a series of alkaloids as well as flavonoids [11–18]. The United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) recognizes seven peaks for quantifying the total withanolides in Ashwagandha which are also attributed for its biological activity. ZEN is formulated to contain these seven peaks with total withanolide content up to 1.5%, as evaluated by HPLC analysis in compliance with the USP method.

Clinical studies have shown that Ashwagandha helps to reduce stress and negative consequences of stress. In addition, Ashwagandha promotes sleep, improves mood, and reduces anxiety [19]. The bioactive compounds from Ashwagandha, particularly withanolides (withanoside IV and V, withanolide A–D, withanone and withaferin-A), are believed to be responsible for their ability to balance, energize, rejuvenate, and revitalize the body [13, 20]. Research studies have shown that the withanolides target enzymes like kinases, growth factors, transcription factors, receptors, and structural proteins in the body to bring about the health benefits [21, 22].

In the current study we have used a novel Ashwagandha formulation—Zenroot™ (ZEN)—that contains 1.5% withanolides and has been formulated to improve bioavailability. In a double-blind, randomized, cross-over study conducted in 20 healthy volunteers, Zenroot™ at 125-mg dose showed 2.1- and 1.3-fold higher bioavailability compared to two different commercial products containing 5% withanolides at 600-mg and 10% withanolides at 500-mg doses, respectively (manuscript under publication). Here, we report the results of the safety and efficacy of ZEN to reduce stress and anxiety as well as to improve mood and sleep quality.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled, clinical interventional study with 84 days of investigational product administration. The study was initiated after obtaining written approval from an institutional ethics committee, Santhosh Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee, Bengaluru, India, on 21 February 2024 and completed on 28 November 2024. The study was carried out as per the requirements of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) ethical guidelines, International Council for Harmonization (ICH) ‘Guidance on Good Clinical Practice’ E6 (R2), and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2024/03/063786).

Voluntary informed consent was obtained from every participant before enrolling in the study. Subjects were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive ZEN or placebo. ZEN was given as a ~ 280-mg capsule containing 125 mg of Ashwagandha powder with total withanolides content of 1.5%, which is equivalent to 1.88 mg of total withanolides and 155 mg of microcrystalline cellulose (Batch # ASH/P1/03/85(C)) manufactured by OmniActive Health Technologies, India, following Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and complying with FSSAI regulations. The placebo capsule contained microcrystalline cellulose with a fill weight of ~ 280 mg. Scarlet red-colored capsules were used for both placebo and ZEN to maintain blinding. The randomization schedule was generated by a non-study assigned, independent expert ensuring the treatment balance using SAS® statistical software version 9.4. After randomization, subjects were instructed to consume one capsule every morning after breakfast at the same time every day for 84 days. The total duration of the clinical study was a maximum of 91 days including the screening period of 7 days.

Information about gender, age, body weight, height, BMI, vital signs, physical examination, medical history, concomitant medication history, history of substance abuse, presence of allergic problems and drug reactions, the factors causing stress (stressors), and the duration of the stress experience were obtained during the screening visit.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): This is a 10-item subjective questionnaire which is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress. The range of response scores are between 0 and 40 with lower scores indicating lower perceived stress and vice versa. Scores from 0 to 13 are considered low/mild stress, scores from 14 to 26 are considered as moderate stress, and scores of 27–40 are considered to be of high perceived stress. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 [23].

Mindfield eSense Skin Response: This is a small sensor to measure skin conductance using two electrodes and the microphone input of Apple iOS and Android devices. Skin conductance depends directly on the state of relaxation or stress, making it a commonly used and very precise stress indicator. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 [24].

Mindfield eSense PULSE–Heart Rate Variability: This is a small sensor to measure heart rate variability with a smartphone or tablet (Android or Apple iOS). Heartbeat is related to tension and relaxation and is a potential stress indicator. The eSense Pulse gives precise feedback about the current level of stress via graphs, video, and audio. The eSense Pulse uses a chest strap which performs a 1-channel ECG measurement. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 [25].

As a way of inducing stress, the participants were talked through their stressors, based on the information derived during the screening using a set of questions, and changes in the eSense objective parameters were correlated to the information derived. Mindfield eSense Skin Response and Mindfield eSense PULSE—Heart Rate Variability assessments were conducted twice on visit days for the duration of 5 min, where both the measurements were separated by a duration of 10 min and the average of the measurements was considered as the outcome of the assessment.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): This is a rating scale used to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms. BAI consists of 21 self-report items with a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 and raw scores ranging from 0 to 63. The items reflect symptoms of anxiety, including numbness or tingling, feeling hot, wobbliness in the legs, ability to relax, fear of the worst happening, dizziness or light-headedness, pounding or racing heart, unsteadiness, feeling terrified, feeling nervous, feeling of choking, hands trembling, feeling shaky, fear of losing control, difficulty breathing, fear of dying, feeling scared, indigestion or abdominal discomfort, faintness, face flushing, and sweating. The BAI scores are classified as minimal anxiety (0–7), mild anxiety (8–15), moderate anxiety (16–25), and severe anxiety (30–63). The BAI can be given to the same patient in subsequent sessions to track the progression or improvement of the anxiety. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 [26].

Profile of Mood States (POMS): This is a psychological rating scale used to assess transient, distinct mood states. POMS consists of 65 self-report items, and was designed to evaluate individuals within seven different mood domains: fatigue–inertia, anger–hostility, vigor–activity, confusion–bewilderment, depression–dejection, tension–anxiety, and friendliness. The scale has been recommended for evaluating affective changes over the course of brief treatment or assessment period. A five-point scale ranging from "not at all" to "extremely" is administered by experimenters to patients to assess their mood states. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 [27].

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): This is an effective instrument used to measure the quality and patterns of sleep during the past month. It differentiates “poor” from “good” sleep by measuring seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction over the last month. Scoring of the answers is based on a 0–3 scale, where 3 reflects the negative extreme on the Likert Scale. This was assessed at baseline, and on days 28, 56, and 84 [28].

Serum cortisol and salivary alpha amylase: Levels of serum cortisol were quantified from serum samples collected during baseline and days 56 and 84 by using ELISA kits. Further, alpha amylase levels were quantified from the salivary samples collected during baseline and on days 56 and 84 by using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

Subjects were enrolled in the study as per the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Subjects who met the following criteria were included in the study:

Stressed male or female adults aged between 18 and 55 years (both limits inclusive); BMI of 18.5–29.9 kg/m2 (both limits inclusive); mild to moderate stress as determined by a score ≥ 7 or ≤ 26 on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) of less than 3 months duration; those who agreed to maintain their regular eating patterns and degree of activity; willing to refrain from taking any medications or preparations for addressing stress or anxiety or mood (herbal, dietary supplements, homeopathic preparations, etc.) during the study; willing to abstain from alcohol consumption 24 h before testing days; abstain from the consumption of caffeine and caffeine-containing items 12 h preceding the test days; willing to abstain from strenuous physical activities 12 h before test days; agreed to maintain weight stability during the trial period; willing to provide written consent and able to comprehend and agree with the research's requirements, consume the study investigational product as advised, return for the needed treatment period visits, comply with therapy restrictions, and be able to finish the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Subjects who met the following criteria were excluded from the study:

Subjects having hypersensitivity or history of allergy to the study product; with severe and/or chronic stress based on a PSS score > 26; individuals with malignant cancer or terminal disease; individuals suffering from severe chronic disease or uncontrolled metabolic disorder, psychiatric disorders; those consuming medications like anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics, sleep medications; individuals with significant habitual caffeine intake (> 300 mg caffeine/day or ≥ 3 cups of caffeinated coffee/day) during the study duration; history of substance and/or alcohol misuse at the time of study; individuals who were pregnant, lactating, or intending to conceive during the trial participation period, or who had a positive urine pregnancy test prior to randomization; and who had received any experimental medicine or device within 3 months preceding trial participation.

Efficacy and Safety Parameters

The primary efficacy endpoint in the study was to evaluate stress using PSS. Secondary efficacy endpoints included objective measures of stress using Mindfield eSense Skin Response (SCR) and Mindfield eSense PULSE Heart Rate Variability (HRV)–Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD), and standard deviation of normal NN interval (SDNN), anxiety using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), mood using the Profile of Mood States (POMS), sleep quality using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and stress biomarkers–serum cortisol levels, and sAA.

Safety parameters included monitoring of adverse events, physical examination, vital signs measurements, and laboratory assessments.

Sample Size Calculations

The evidence from the previous placebo-controlled study conducted to evaluate the effects of Ashwagandha on stressed individuals reported a mean difference of reduction of 5.7 on the PSS. The true difference between test and placebo in terms of PSS was 5.7 (13.0 and 18.7 for test and placebo products, respectively, at end of the study), while the expected population standard deviation (SD) was assumed to be 4.8 and the margin of clinically meaningful improvement on PSS score was assumed to be 3.

To establish superiority of the test treatment over the placebo treatment at 80% power (i.e., 1−β = 0.8) at the 5% level of significance (i.e., α = 0.05) with equal allocation (i.e., k = 1), 40 subjects were to be enrolled into each treatment arm. Giving due consideration for drop-out and non-compliance of ≈ 15%, the sample size was calculated to be 45 subjects per group. Therefore, a total of 90 subjects were enrolled and equally randomized into the test and placebo treatments of the study.

Statistical Analysis

The conclusions pertaining to significance of treatment specific differences in endpoints were based on analysis of variance (ANOVA). The magnitude of relative differences of the outcome measure variable at a particular visit was calculated as difference between a visit-specific value and the baseline value of that variable. ANOVA was conducted for the respective visit-specific magnitude of differences from baseline between the treatments to evaluate the significance of the differences.

For all the outcome measure variables, the percentage change from its baseline observation was calculated at each subsequent visit of the study. The statistical analysis was conducted on SAS®, version 9.4. All the analyses were conducted at the significance level (p value) of 0.05.

Safety Analysis

Safety analyses were performed using hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis, the incidence of adverse events, physical examination, and vital signs measurements for all the randomized subjects who received at least one dose of the study supplement. Descriptive statistics [n (number of subjects), mean, standard deviation, standard error, median, minimum and maximum] for continuous safety variables and frequency, the percentage for categorical safety variables such as adverse events were summarized by treatment.

Results

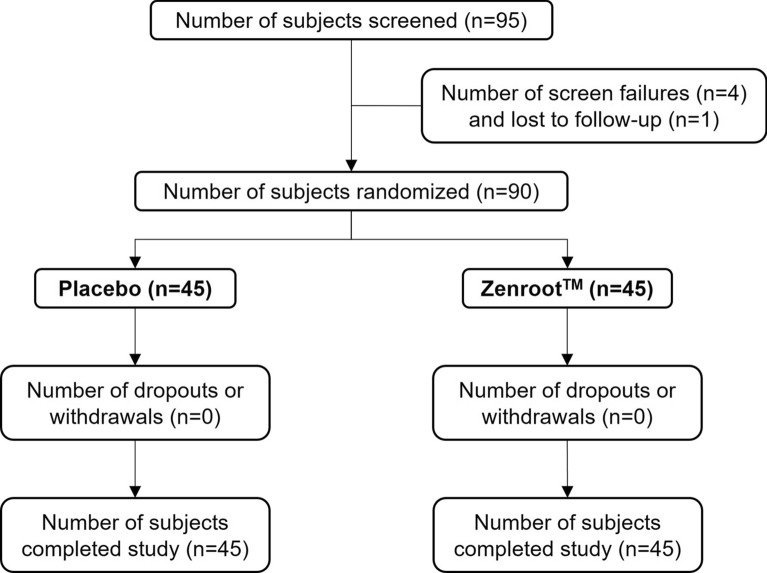

A total of 95 subjects were screened, of which 4 subjects were considered screen failures and 1 subject was lost to follow-up prior to randomization (Fig. 1). Of the 90 randomized subjects, 45 were allocated to the ZEN group and 45 to the placebo group. All the 90 subjects completed the study. The demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age (mean ± SE) of subjects in the placebo group was 34.50 ± 1.20 years and in the ZEN group was 35.50 ± 1.30 years. There were 22 (49%) male and 23 (51%) female participants in the placebo group and 22 (49%) male and 23 (51%) female participants in the ZEN group. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.53 ± 0.36 for the placebo group and 25.55 ± 0.40 for the ZEN group at the screening visit. The majority of the study subjects had family-related stressors followed by job-/work-related stressors, a combination of family and work, and finance-related stressors.

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for efficacy and safety of Zenroot™ in a randomized clinical interventional study in humans with stress, showing subject disposition including screening, randomization, withdrawals, and completion

Table 1.

Demographics of study participants placebo versus Zenroot™

| Demographic profile | Zenroot™ (N = 45) | Placebo (N = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) [mean ± SE] | 35.50 ± 1.30 | 34.50 ± 1.20 | |

| Male [n (%)] | 22 (49%) | 22 (49%) | |

| Female [n (%)] | 23 (51%) | 23 (51%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) [mean ± SE] | 25.55 ± 0.40 | 24.53 ± 0.36 |

Percentages are based on the number of subjects in the specified treatment

N number of subjects in the specified treatment, n number of subjects in the specified category, SE standard error

Efficacy

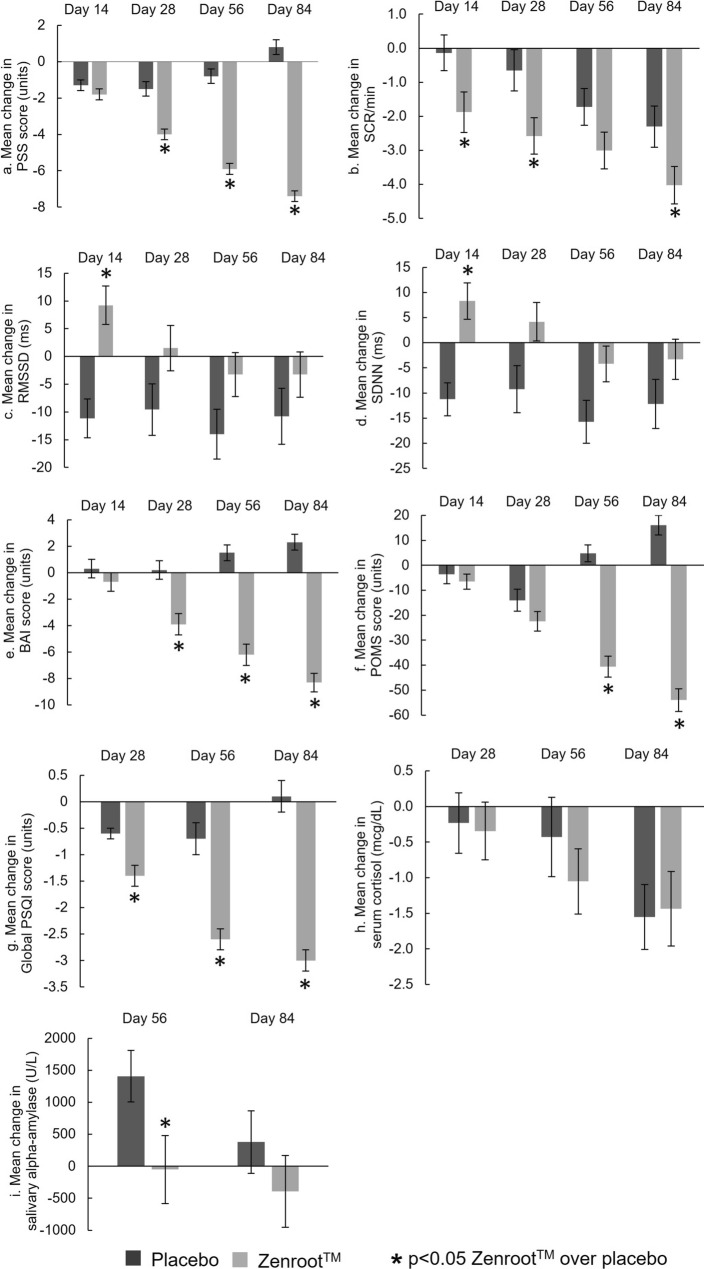

The efficacy analysis was performed for the 90 subjects who completed the study. The results are shown as graphs in Fig. 2(a–i), summarized as mean change ± SE.

Fig. 2.

Summary of efficacy endpoint results. Mean changes of placebo versus Zenroot™: a Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores in units; b Mindfield eSense Skin Response (SCR) per minute; c Mindfield eSense PULSE: root mean square successive difference (RMSSD) in milliseconds, d standard deviation of normal NN interval (SDNN) in milliseconds; e Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) scores in units; f profile of Mood States (POMS) scores in units; g global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores in units; and stress biomarkers: h serum cortisol levels (mcg/dL), and i salivary alpha-amylase (U/L). *p value < 0.05 Zenroot™ over placebo

Primary Efficacy Analyses

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in PSS score on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 compared to baseline. Similarly, the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in PSS score on days 14, 28, and 56, whereas a significant increase was noted on day 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in PSS score in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on days 28 (− 4.0 ± 0.3 for ZEN vs. − 1.5 ± 0.4 for placebo), 56 (− 5.9 ± 0.3 for ZEN vs. − 0.8 ± 0.4 for placebo) and 84 (− 7.4 ± 0.3 for ZEN vs. 0.8 ± 0.4 for placebo) (Table 2; Fig. 2a). No significant differences were observed between the groups on day 14.

Table 2.

Summary of efficacy endpoint results: mean (SE) values and mean change (SE) from baseline values of Zenroot™ versus placebo

| Sr. no | Measurement parameter | Mean (SE) values | Mean change (SE) from baseline values | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 56 | Day 84 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 56 | Day 84 | |||||||||||

| ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ZEN | Placebo | ||

| 1 | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

22.10 (0.30) |

22.20 (0.30) |

20.30 (0.30) |

20.80 (0.30) |

18.10 (0.30) |

20.60 (0.40) |

16.20 (0.30) |

21.30 (0.40) |

14.70 (0.30) |

22.90 (0.40) |

− 1.80 (0.30) |

− 1.30 (0.30) |

− 4.00 (0.30) |

− 1.50 (0.40) |

− 5.90 (0.30) |

− 0.80 (0.40) |

− 7.40 (0.30) |

0.80 (0.40) |

| p value | 0.9206 | 0.2886 | < .0001* | < .0001* | < .0001* | 0.2302 | < .0001* | < .0001* | < .0001* | ||||||||||

| 2 | Mindfield eSense Skin Response Assessment (SCR/min) |

9.28 (0.42) |

8.25 (0.38) |

7.33 (0.44) |

8.11 (0.44) |

6.73 (0.43) |

7.63 (0.41) |

6.21 (0.41) |

6.61 (0.42) |

5.30 (0.36) |

5.95 (0.48) |

− 1.88 (0.60) |

− 0.14 (0.52) |

− 2.58 (0.53) |

− 0.66 (0.61) |

− 3.01 (0.54) |

− 1.73 (0.54) |

− 4.02 (0.55) |

− 2.30 (0.61) |

| p value | 0.0708# | 0.2123 | 0.1385 | 0.4996 | 0.2785 | 0.0347* | 0.0209* | 0.0788# | 0.0336* | ||||||||||

| 3 | Mindfield eSense PULSE—Heart Rate Variability Assessment (RMSSD) |

36.07 (3.08) |

48.74 (3.31) |

45.23 (4.27) |

37.57 (2.81) |

37.57 (3.46) |

39.16 (3.40) |

32.80 (3.48) |

34.40 (3.31) |

32.81 (3.86) |

37.94 (3.79) |

9.22 (21.82) |

− 11.17 (3.49) |

1.50 (4.10) |

− 9.58 (4.66) |

− 3.27 (3.93) |

− 14.01 (4.49) |

− 3.26 (4.08) |

− 10.80 (5.05) |

| p value | 0.0064* | 0.1342 | 0.7410 | 0.7410 | 0.3456 | < .0001* | 0.0783# | 0.0756# | 0.2504 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Mindfield eSense PULSE—Heart Rate Variability Assessment (SDNN) |

53.47 (3.12) |

67.35 (3.59) |

62.12 (4.36) |

56.10 (2.92) |

57.65 (3.92) |

58.14 (3.59) |

49.27 (3.65) |

51.50 (3.43) |

50.16 (4.29) |

55.20 (3.85) |

8.29 (3.62) |

− 11.25 (3.30) |

4.18 (3.83) |

− 9.22 (4.68) |

− 4.20 (3.55) |

− 15.75 (4.28) |

− 3.31 (4.01) |

− 12.16 (4.87) |

| p value | 0.0046* | 0.2505 | 0.9206 | 0.6559 | 0.3828 | 0.0001* | 0.0298* | 0.0409* | 0.1653 | ||||||||||

| 5 | Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Score |

18.90 (0.80) |

18.20 (0.80) |

18.20 (0.80) |

18.50 (0.90) |

15.00 (0.60) |

18.40 (0.70) |

12.60 (0.60) |

19.70 (0.80) |

10.60 (0.60) |

20.60 (0.60) |

− 0.70 (0.70) |

0.30 (0.70) |

− 3.90 (0.80) |

0.20 (0.70) |

− 6.20 (0.80) |

1.50 (0.60) |

− 8.30 (0.70) |

2.30 (0.60) |

| p value | 0.5556 | 0.7649 | 0.0008* | < .0001* | < .0001* | 0.3106 | 0.0002* | < .0001* | < .0001* | ||||||||||

| 6 | Profile of Mood States (POMS) Score |

77.70 (5.60) |

76.70 (5.80) |

71.20 (4.50) |

73.10 (5.00) |

55.30 (3.10) |

62.80 (3.80) |

37.00 (3.00) |

81.50 (5.30) |

23.70 (3.60) |

92.80 (3.70) |

− 6.50 (3.00) |

− 3.60 (3.70) |

− 22.40 (3.90) |

− 14.00 (4.40) |

− 40.60 (4.20) |

4.80 (3.40) |

− 54.00 (4.60) |

16.10 (3.90) |

| p value | 0.9206 | 0.7780 | 0.1281 | < .0001* | < .0001* | 0.5501 | 0.1568 | < .0001* | < .0001* | ||||||||||

| 7 | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score |

7.10 (0.20) |

6.90 (0.20) |

– | – |

5.70 (0.20) |

6.30 (0.20) |

4.60 (0.20) |

6.20 (0.20) |

4.10 (0.20) |

7.00 (0.30) |

– | – |

− 1.40 (0.20) |

− 0.60 (0.10) |

− 2.60 (0.20) |

− 0.70 (0.30) |

− 3.00 (0.20) |

0.10 (0.30) |

| p value | 0.4563 | - | 0.0279* | < .0001* | < .0001* | – | 0.0006* | < .0001* | < .0001* | ||||||||||

| 8 | Serum Cortisol level (μg/dL) |

8.59 (0.46) |

8.33 (0.51) |

8.25 (0.46) |

7.91 (0.36) |

– | – |

7.75 (0.48) |

8.01 (0.55) |

7.22 (0.41) |

6.77 (0.41) |

-0.35 (0.41) |

-0.23 (0.43) |

– | – |

− 1.05 (0.46) |

− 0.43 (0.56) |

− 1.44 (0.52) |

− 1.55 (0.46) |

| p value | 0.6995 | 0.5671 | – | 0.7299 | 0.4407 | 0.8420 | – | 0.3921 | 0.8629 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Salivary alpha-amylase level (U/L) |

2291.70 (462.00) |

2037.60 (224.70) |

– | – | – | – |

2239.30 (349.50) |

3492.80 (394.80) |

1899.10 (351.60) |

2414.50 (416.60) |

– | – | – | – |

− 52.40 (531.70) |

1406.00 (401.40) |

− 392.70 (561.00) |

376.90 (489.00) |

| p value | 0.6184 | – | – | 0.0197* | 0.3481 | – | – | 0.0314* | 0.3016 | ||||||||||

*p < 0.05 Significance over placebo

#p > 0.05 but p < 0.1 Trend over placebo

Further, based on the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) evaluation for perceived stress scale score, 100% (n = 45) of the subjects treated in ZEN group achieved MCID whereas only 13.3% subjects in placebo group showed improvements that met MCID.

Secondary Efficacy Analyses

Mindfield eSense Skin Response (Skin Conductance Rate (SCR)/Min)

A statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in SCR/min was observed on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 in the ZEN group, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in SCR/min on days 56 and 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in SCR/min in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on days 14 (− 1.878 ± 0.596 for ZEN vs. − 0.138 ± 0.522 for placebo), 28 (− 2.580 ± 0.533 for ZEN vs. − 0.655 ± 0.605 for placebo), and 84 (− 4.024 ± 0.549 for ZEN vs. − 2.302 ± 0.605 for placebo), whereas a decreasing trend was observed at day 56 (p = 0.07875) (Table 2; Fig. 2b).

Mindfield eSense PULSE–HRV RMSSD

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in RMSSD on day 14 and no significant differences were observed on days 28, 56, and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease on days 14, 28, 56, and 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in RMSSD in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on day 14 (9.225 ± 3.451 for ZEN vs. − 11.174 ± 3.489 for placebo), whereas no significant differences were observed between the groups on days 28, 56, and 84 (Table 2; Fig. 2c).

Mindfield eSense PULSE–HRV SDNN

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in SDNN on day 14 and no significant differences were observed on days 28, 56, and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease on days 14, 56, and 84 and a trend at day 28 (p = 0.05562) compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in SDNN in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on day 14 (8.290 ± 3.621 for ZEN vs. -11.251 ± 3.301 for placebo), whereas no significant differences were observed between the groups on day 84 compared to baseline. Even though significance was observed between the groups on days 28 and 56, it was not attributed to the ZEN group due to the lack of significance from baseline (Table 2; Fig. 2d).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in BAI scores on days 28, 56, and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase on days 56 and 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in BAI score in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on days 28 (− 3.9 ± 0.8 for ZEN vs. 0.2 ± 0.7 for placebo), 56 (− 6.2 ± 0.8 for ZEN vs. 1.5 ± 0.6 for placebo), and 84 (− 8.3 ± 0.7 for ZEN vs. 2.3 ± 0.6 for placebo) (Table 2; Fig. 2e). No significant differences were observed between the groups on day 14.

Further, based on the MCID evaluation for the BAI score, 91.1% (n = 41) of the subjects treated in the ZEN group achieved MCID whereas only 6.67% (n = 3) subjects in the placebo group showed improvements that met MCID.

Profile of Mood States (POMS)

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in POMS–Total Mood Disturbance scores on days 14, 28, 56, and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease on day 28 and an increase on day 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in POMS–Total Mood Disturbance score in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on days 56 (− 40.6 ± 4.2 for ZEN vs. 4.8 ± 3.4 for placebo) and 84 (− 54.0 ± 4.6 for ZEN vs. 16.1 ± 3.9 for placebo) (Table 2; Fig. 2f). No significant differences were observed between the groups on days 14 and 28.

Further, based on the MCID evaluation for POMS–Total Mood Disturbance score, 84.4% (n = 38) of the subjects treated in the ZEN group achieved MCID whereas only 2.2% (n = 1) subjects in the placebo group showed improvements that met MCID.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in global PSQI score on days 28, 56, and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease on days 28 and 56 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in global PSQI score in the ZEN group compared to the placebo group on days 28 (− 1.4 ± 0.2 for ZEN vs. − 0.6 ± 0.1 for placebo), 56 (− 2.6 ± 0.2 for ZEN vs. -0.7 ± 0.3 for placebo), and 84 (− 3.0 ± 0.2 for ZEN vs. 0.1 ± 0.3 for placebo) (Table 2; Fig. 2g).

Further, based on the MCID evaluation for global PSQI score, 91.1% (n = 41)- of the subjects treated in the ZEN group achieved MCID whereas only 33.3% (n = 15) subjects in the placebo group showed improvements that met MCID.

Serum Cortisol

The ZEN group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in serum cortisol levels on days 56 and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease on day 84 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis showed no significant (p < 0.05) differences between the two groups on days 56 and 84 (Table 2; Fig. 2h).

Salivary Alpha-Amylase (sAA)

The ZEN group did not show any statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference in salivary alpha-amylase levels on days 56 and 84, whereas the placebo group showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase on day 56 compared to baseline.

The between-group analysis showed no significant (p < 0.05) differences between the groups on day 84 (Table 2; Fig. 2I). Even though significance was observed between the groups at day 56, it was not attributed to the ZEN group due to a lack of significance from baseline.

Safety

ZEN was well-tolerated throughout the study period without any safety concerns. The proportion of subjects who experienced at least one adverse event (AE) during the study was 33.3% for the ZEN group, and 20% for the placebo group. The most common AEs reported were pyrexia (6 subjects in the ZEN group, 4 subjects in the placebo group), followed by gastritis (3 subjects in the ZEN group and 1 subject in the placebo group). All the AEs were mild in severity except for two subjects: one each in the placebo group and the ZEN group had moderate AEs, i.e., pyrexia (1 subject in the placebo group) and cough and cold (1 subject in the ZEN group). All the AEs were unrelated to study products. No subjects discontinued treatment due to AEs and all the AEs were resolved (Supplementary Table 1).

The laboratory evaluations carried out to evaluate treatment-specific changes in hematology, renal function, and hepatic function were not different between the groups. There were no clinically conclusive abnormalities observed at the end of the study.

Discussion

Stress is a natural reaction of the body against emotional or physical challenges and, when induced for a prolonged time, may lead to behavioral or neuropsychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia [6]. Adaptogens like Ashwagandha are known to assist the body to manage stress and sleep disorders and are widely used in traditional medicine [29]. In the current study, we evaluated the clinical benefit of ZEN, a novel formulation of Ashwagandha with 1.5% withanolide content, on stress, anxiety, mood, and sleep. We observed significantly improved subjective parameters over placebo, such as reduced perceived stress, improved sleep quality and mood, and reduced anxiety. Mindfield galvanic skin response assessments indicated that ZEN reduced sympathetic stress response, improved basal stress tolerability to spontaneous triggers of physiological stress, and improved heart rate variability (SDNN and RMSSD) on day 14 compared to placebo. However, we did not observe significant differences in serum cortisol levels and sAA between the ZEN and placebo groups after 12 weeks of supplementation. Further, ZEN was found to be safe and well tolerated with no significant AEs reported throughout the study. In this study, a placebo was used to control the psychological effects on stress, anxiety, mood, and sleep. Serving as an effective control, the placebo helped to isolate and identify the true impact of the study product by accounting for the participants' psychological responses.

Withanolides, a class of steroidal lactones from Ashwagandha, are widely attributed to the biological properties of the plant extract. The USP recognizes seven peaks for quantifying the total withanolides in Ashwagandha which are also attributed its biological activity. Our Ashwagandha preparation had been formulated to contain all the seven peaks with a total withanolide content of 1.5%, as measured by the USP method of analysis. However, most of the published clinical studies on the health benefits of Ashwagandha have been generated with widely used commercial preparations that used a non-USP method of the analysis for withanolide content. Further, a comparative pharmacokinetic study conducted in healthy human volunteer indicated that ZEN at a comparatively lower dose of 125 mg achieved a higher plasma concentration of total withanolides compared to two widely used commercial preparations with declared withanolide contents of 5 and 10% and at a dose of 600 and 500 mg, respectively (manuscript under publication). The current study is an effort to further validate the improved bioavailability of ZEN through efficacy studies and to demonstrate health benefits as well as to establish safety in human subjects.

The PSS is a most widely used psychological tool for measuring the perception of personal stress, and we observed a statistically significant decrease in perceived stress from baseline for the ZEN group compared to placebo on days 28, 56, and 84 of supplementation which was our primary efficacy endpoint. Further, 100% of subjects in the ZEN group achieved MCID compared to 13.3% of subjects in the placebo group. The MCID is paramount, as it serves to ascertain whether a treatment effect, despite achieving statistical significance, possesses genuine clinical relevance for subjects [30, 31]. Reductions of PSS scores have been observed previously in response to Ashwagandha extract supplementation [9, 32, 33], with significant improvement in sleep quality and reduced serum cortisol levels. Ashwagandha root extract supplementation helped to reduce anxiety after 8 weeks of supplementation in adults with anxiety disorder [34] in one study, while another study showed no statistically significant differences with supplementation [35]. We observed a significant reduction in anxiety, as measured by BAI, associated with an improved sleep index measured by PSQI in our study subjects supplemented with ZEN. This was further supported by MCID being achieved by 91.1% subjects for BAI and PSQI scores in the ZEN group, respectively. Again, these results are consistent with reported studies where Ashwagandha root extract showed significant improvements in sleep latency, efficiency, sleep quality, and anxiety-related symptoms in subjects suffering from insomnia [36–38]. Further, ZEN also demonstrated a significant decrease in mood disturbances with supplementation compared to placebo, and was further supported by MCID seen in 84.4% of subjects.

Ashwagandha, being an adaptogenic herb, is used to combat stress and anxiety by regulating cortisol levels. Ashwagandha extract reduces serum cortisol levels possibly by modulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function [6, 33, 39]. We measured serum cortisol levels in our subjects as an objective measure of physiological stress. However, we observed no significant differences in serum cortisol levels between the placebo and ZEN groups throughout the study period. In our study, we recruited non-chronic healthy human subjects with mild to moderate stress, with serum cortisol levels within the normal range, and, hence, we have not been able to demonstrate the effect of Ashwagandha on serum cortisol levels. Considering the diurnal variations in serum cortisol levels, we tried to standardize the sample collection time in the morning between 8 and 10 am for all subject visits. However, variations in blood cortisol levels due to diet, exercise, and sleep schedules cannot be ruled out.

Similarly, we have not observed the effect of supplementation on sAA levels in our study, which is again an indicator of stress. Future clinical studies should focus on subject recruitment with serum cortisol and sAA levels above the normal range, which may help to demonstrate the effect of our Ashwagandha formulation on them.

Both pre-clinical experimental and human clinical studies have demonstrated benefits of Ashwagandha on anxiety, depression, and insomnia [6, 40–44]. Withanolides from Ashwagandha inhibit histamine, prostaglandins, and interleukin production [42, 45, 46]. Ashwagandha also reduces peripheral T-lymphocytes counts (CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ populations), IL-2, INF-γ, and polymorphonuclear leukocyte counts [47]. In rodents, Ashwagandha modulated stress-induced blood cell counts, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils [48, 49]. Ashwagandha extract is also known to induce anti-anxiety effects by modulating gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors [50, 51] and to reverse the activity of picrotoxin, a GABA antagonist. Further, Ashwagandha extract potentiates the activity of muscimol, a GABA agonist, and helps to reduce sleep latency, increased slow wave sleep, REM, and total sleep time in sleep-deprived male Wistar rats [52]. Decreased anti-oxidants leading to increased oxidative damage to the brain may contribute to anxiety disorders [53–55]. Ashwagandha showed increased catalase activity and reduced glutathione levels in the brain [56, 57]. Ashwagandha also reduced lipid peroxidation and increased anti-oxidant activity in the brain of a rat model of ischemic stroke [58], reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-6, NOX2, iNOS, COX2, and GFAP [59, 60], and modulated the NF-κB signaling pathway [61].

Most studies have reported that Ashwagandha exhibits no major side effects and is well tolerated. Commonly reported AEs of Ashwagandha were mild indigestion, mild nausea, and stomach pain. One study reported unusual symptoms including increased appetite, increased libido, and hallucinogenic effects with vertigo after 3 days of Ashwagandha intake [41]. Our results showed no safety concerns and ZEN was well tolerated.

The study's scope was limited to participants experiencing non-chronic, mild-to-moderate stress of less than 3 months' duration, all of whom presented with normal serum cortisol levels at baseline. Despite these limitations, ZEN demonstrated significant stress-reducing effects within this population, evidenced by both subjective assessments (using the PSS tool) and objective measurements (Mindfield eSense Skin Response and Mindfield eSense PULSE–Heart Rate Variability). Future research should explore the effects of ZEN in individuals with chronic stress, using a larger sample size.

Conclusion

The results of our study indicate that ZEN at a 125-mg dose reduced the subjective perception of stress and resulted in improvements of its associated impairments in sleep quality, severity of occasional anxiety symptoms, and mood state. In addition, ZEN supplementation also maintained the levels of systemic stress responses inclined towards the parasympathetic drive for relaxation. ZEN was well tolerated without any related adverse events.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Author Contributions

Abhijeet Morde, Manasvi Mahadevan, Kumarpillai Gopukumar, Ruchi Gupta, and Abhijith Phanindra were involved in designing the study. Manasvi Mahadevan, Kumarpillai Gopukumar, and Ruchi Gupta were responsible for conducting the study at the site, volunteer recruitment, study procedures, data collection, statistical analysis and study report. Arun Bhuvanendran was responsible for data collection and data management activities. Sahitya Sarvamangala Srinivas was responsible for overall project management and monitoring activities. Abhijeet Morde and Paras Patni were responsible for study co-monitoring. The manuscript was drafted by Manasvi Mahadevan, Kumarpillai Gopukumar, Ruchi Gupta, and Abhijith Phanindra and reviewed by Sahitya Sarvamangala Srinivas, Arun Bhuvanendran, Abhijeet Morde and Paras Patni. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees was supported by OmniActive Health Technologies Limited (Mumbai, India).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Manasvi Mahadevan, Kumarpillai Gopukumar are the clinical investigators at Bengaluru Neuro Center, Ruchi Gupta is a clinical investigator at Santosh hospital. Sahitya Sarvamangala Srinivas, Arun Bhuvanendran and Abhijith Phanindra are employees of Invitro Research Solutions Private Limited. Abhijeet Morde and Paras Patni are employees of OmniActive Health Technologies.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles originated from Helsinki Declaration and in strict compliance with the “New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules- 2019,” the Ministry of Health and the Government of India, at all stages of the trial for adherence to protocol. The study activities commenced after obtaining an approval from Santhosh Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee, Bengaluru, India, on the 21st February 2024. The EC was duly apprised of the progress and updates of the trial at regular intervals as per prescribed guidelines.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.de Zambotti M, Goldstone A, Colrain IM, Baker FC. Insomnia disorder in adolescence: diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanford LD, Suchecki D, Meerlo P. Stress, arousal, and sleep. In: Meerlo P, Benca RM, Abel T, editors. Sleep neuronal plasticity and brain function, vol. 25. Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg: Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. p. 379–410. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayada C, Ü T, Korkut Y. The relationship of stress and blood pressure effectors. Hippokratia. 2015;19(2):99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasperin D, Netuveli G, Dias-da-Costa JS, Pattussi MP. Effect of psychological stress on blood pressure increase: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(4):715–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herd JA. Cardiovascular response to stress. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(1):305–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speers AB, Cabey KA, Soumyanath A, Wright KM. Effects of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) on stress and the stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(9):1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spear LP. Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: implications for psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(1):87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honaker SM, Simon SL, Byars KC, Simmons DM, Williamson AA, Meltzer LJ. Advancing patient-centered care: an international survey of adolescent perspectives on insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2024;22(5):571–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandrasekhar K, Kapoor J, Anishetty S. A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(3):255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelwahed MT, Hegazy MA, Mohamed EH. Major biochemical constituents of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) extract: a review of chemical analysis. Rev Anal Chem. 2023;42(1):20220055. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta GL, Rana AC. Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha): a review. Pharmacogn Rev. 2007;1(1):129–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleem S, Muhammad G, Hussain MA, Altaf M, Bukhari SNA. Withania somnifera L.: insights into the phytochemical profile, therapeutic potential, clinical trials, and future prospective. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2020;23(12):1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul S, Chakraborty S, Anand U, Dey S, Nandy S, Ghorai M, et al. Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha): a comprehensive review on ethnopharmacology, pharmacotherapeutics, biomedicinal and toxicological aspects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;143: 112175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bharti VK, Malik JK, Gupta RC. Ashwagandha: multiple health benefits. In: Nutraceuticals. Elsevier; 2016. p. 717–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glotter E, Kirson I, Abraham A, Lavie D. Constituents of Withania somnifera Dun—XIII: the withanolides of chemotype III. Tetrahedron. 1973;29(10):1353–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirayama M, Gamoh K, Ikekawa N. Stereoselective synthesis of withafein A and 27-deoxywithaferin A1. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23(45):4725–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuda H, Murakami T, Kishi A, Yoshikawa M. Structures of withanosides I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII, new withanolide glycosides, from the roots of Indian Withania somnifera DUNAL. and inhibitory activity for tachyphylaxis to clonidine in isolated guinea-pig ileum. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9(6):1499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong X, Zhang H, Timmermann BN. Chlorinated withanolides from Withania somnifera. Phytochem Lett. 2011;4(4):411–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akhgarjand C, Asoudeh F, Bagheri A, Kalantar Z, Vahabi Z, Shab-bidar S, et al. Does ashwagandha supplementation have a beneficial effect on the management of anxiety and stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2022;36(11):4115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. Immune enhancing effects of WB365, a novel combination of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) and Maitake (Grifola frondosa) extracts. North Am J Med Sci. 2011;3(7):320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sari AN, Bhargava P, Dhanjal JK, Putri JF, Radhakrishnan N, Shefrin S, et al. Combination of withaferin-A and CAPE provides superior anticancer potency: bioinformatics and experimental evidence to their molecular targets and mechanism of action. Cancers. 2020;12(5):1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tewari D, Chander V, Dhyani A, Sahu S, Gupta P, Patni P, et al. Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal: phytochemistry, structure-activity relationship, and anticancer potential. Phytomedicine. 2022;98: 153949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris KM, Gaffey AE, Schwartz JE, Krantz DS, Burg MM. The perceived stress scale as a measure of stress: decomposing score variance in longitudinal behavioral medicine studies. Ann Behav Med. 2023;57(10):846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.eSense Skin Response—Mobile Biofeedback with your smartphone or tablet. [Internet]. Mindfield eSense. Available from: https://mindfield-esense.com/esense-skin-response. Accessed 24 Mar 2025.

- 25.eSense Pulse | HRV optimal biofeedback iPhone, Android smartphone. Heart rate variability at home [Internet]. Mindfield eSense. Available from: https://mindfield-esense.com/esense-pulse-hrv-en. Accessed Mar 24, 2025.

- 26.Leyfer OT, Ruberg JL, Woodruff-Borden J. Examination of the utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and its factors as a screener for anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(4):444–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahid A, Wilkinson K, Marcu S, Shapiro CM. Profile of mood states (POMS). In: Shahid A, Wilkinson K, Marcu S, Shapiro CM, editors. STOP, THAT and one hundred other sleep scales [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer, New York; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabowski WK, Karoń KA, Karoń ŁM, Zygmunt AE, Drapała G, Pedrycz E, et al. Unlocking better sleep and stress relief: the power of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) supplementation–a literature review. Qual Sport. 2024;26:54904–54904. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drachev SN, Stangvaltaite-Mouhat L, Bolstad NL, Johnsen JAK, Yushmanova TN, Trovik TA. Perceived stress and associated factors in Russian medical and dental students: a cross-sectional study in north-west Russia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15): 5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salve J, Pate S, Debnath K, Langade D. Adaptogenic and anxiolytic effects of ashwagandha root extract in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study. Cureus [Internet]. 2019;11(12). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6979308/. Accessed Dec 26, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Choudhary D, Bhattacharyya S, Joshi K. Body weight management in adults under chronic stress through treatment with ashwagandha root extract: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Evidence-Based Compl Alternative Med. 2017;22(1):96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khyati S, Anup B. A randomized double blind placebo controlled study of ashwagandha on generalized anxiety disorder. Int Ayurvedic Med J. 2013;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrade C, Aswath A, Chaturvedi SK, Srinivasa M, Raguram R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the anxiolytic efficacy ff an ethanolic extract of withania somnifera. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42(3):295–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langade D, Kanchi S, Salve J, Debnath K, Ambegaokar D. Efficacy and safety of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract in insomnia and anxiety: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Cureus [Internet]. 2019;11(9). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6827862/. Accessed Dec 28, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Langade D, Thakare V, Kanchi S, Kelgane S. Clinical evaluation of the pharmacological impact of ashwagandha root extract on sleep in healthy volunteers and insomnia patients: A double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;264: 113276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deshpande A, Irani N, Balkrishnan R, Benny IR. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract on sleep quality in healthy adults. Sleep Med. 2020;72:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abedon B, Auddy B, Hazra J, Mitra A, Ghosal S. A standardized Withania somnifera extract significantly reduces stress-related parameters in chronically stressed humans: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Jana. 2008;11:50–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pratte MA, Nanavati KB, Young V, Morley CP. An alternative treatment for anxiety: a systematic review of human trial results reported for the Ayurvedic herb ashwagandha (Withania somnifera). J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(12):901–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopresti AL, Smith SJ. Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) for the treatment and enhancement of mental and physical conditions: a systematic review of human trials. J Herb Med. 2021;28: 100434. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bashir A, Nabi M, Tabassum N, Afzal S, Ayoub M. An updated review on phytochemistry and molecular targets of Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha). Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1049334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welch J, Bashir H, Daniels S. The effectiveness of Withania somnifera supplementation on male sexual health: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Med Plants. 2023;11(4):34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikulska P, Malinowska M, Ignacyk M, Szustowski P, Nowak J, Pesta K, et al. Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)—current research on the health-promoting activities: a narrative review. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(4):1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma S. Role of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2023;19(2):158–65. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choudhary D, Bhattacharyya S, Bose S. Efficacy and safety of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal) root extract in improving memory and cognitive functions. J Diet Suppl. 2017;14(6):599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan B, Ahmad SF, Bani S, Kaul A, Suri KA, Satti NK, et al. Augmentation and proliferation of T lymphocytes and Th-1 cytokines by Withania somnifera in stressed mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(9):1394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anju A. Adaptogenic and anti-stress activity of Withania somnifera in stress induced mice. 2011. 10.5555/20113364201. Accessed Dec 26, 2024.

- 49.Puri S, Kumar B, Debnath J, Tiwari P, Salhan M, Kaur M, et al. Comparative pharmacological evaluation of adaptogenic activity of Holoptelea integrifolia and Withania somnifera. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2011;3(1):84–98. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mehta AK, Binkley P, Gandhi SS, Ticku MK. Pharmacological effects of Withania somnifera root extract on GABAA receptor complex. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:312–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonar VP, Fois B, Distinto S, Maccioni E, Meleddu R, Cottiglia F, et al. Ferulic Acid Esters and Withanolides: in Search of Withania somnifera GABAA Receptor Modulators. J Nat Prod. 2019;82(5):1250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar A, Kalonia H. Effect of Withania somnifera on sleep-wake cycle in sleep-disturbed rats: possible GABAergic mechanism. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70(6):806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cobley JN, Fiorello ML, Bailey DM. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2018;15:490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fedoce ADG, Ferreira F, Bota RG, Bonet-Costa V, Sun PY, Davies KJA. The role of oxidative stress in anxiety disorder: cause or consequence? Free Radic Res. 2018;52(7):737–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salim S, Chugh G, Asghar M. Inflammation in anxiety. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2012;88:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar A, Kalonia H. Protective effect of Withania somnifera Dunal on the behavioral and biochemical alterations in sleep-disturbed mice (Grid over water suspended method). 2007; Available from: https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/handle/123456789/5273. Accessed Dec 30, 2024. [PubMed]

- 57.Mohanty R, Das SK, Singh NR, Patri M. Withania somnifera leaf extract ameliorates benzo[a]pyrene-induced behavioral and neuromorphological alterations by improving brain antioxidant status in zebrafish ( Danio rerio ). Zebrafish. 2016;13(3):188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sood A, Kumar A, Dhawan DK, Sandhir R. Propensity of Withania somnifera to attenuate behavioural, biochemical, and histological alterations in experimental model of stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(7):1123–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaur T, Singh H, Mishra R, Manchanda S, Gupta M, Saini V, et al. Withania somnifera as a potential anxiolytic and immunomodulatory agent in acute sleep deprived female Wistar rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;427(1–2):91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gupta M, Kaur G. Withania somnifera as a potential anxiolytic and anti-inflammatory candidate against systemic lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. NeuroMolecular Med. 2018;20(3):343–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaur T, Kaur G. Withania somnifera as a potential candidate to ameliorate high fat diet-induced anxiety and neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1): 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.