Abstract

Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) serve critical roles in insect communication and desiccation resistance and are increasingly recognized as valuable taxonomic characters. This study investigates inter- and intraspecific variation in CHC profiles across ten Isophya species representing three distinct species groups (zernovi, rectipennis, and staneki), focusing on how these profiles vary by species identity, sex, and mating status. A total of 829 individuals (411 females, 418 males) were sampled and analyzed via GC–MS to quantify CHC composition. Multivariate analyses revealed strong effects of species and sex, as well as significant species × sex × mating status interactions. In both males and females, species in the zernovi group displayed tightly clustered CHC profiles, whereas members of the rectipennis group exhibited broader within-group dispersion, with I. rectipennis forming a distinct cluster. I. staneki was clearly differentiated from all other taxa. CHCs were categorized into six structural classes, with n-alkanes being the most dominant across all taxa. Linear mixed-effects models confirmed that CHC class composition was significantly affected by sex and mating status, particularly for alkenes and methyl-branched alkanes. Notably, nonvirgin individuals showed greater CHC variability, suggesting reproductive condition influences chemical expression. While the study remains descriptive, these findings highlight the potential utility of CHCs in taxonomic resolution, sexual communication, and ecological adaptation in Isophya. The integrative use of CHC data, in combination with morphological and acoustic traits, provides a promising framework for understanding species boundaries and evolutionary divergence in Orthoptera.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-17544-7.

Keywords: Cuticular hydrocarbons, Chemical ecology, Sex, Mating status, Isophya, Orthoptera

Subject terms: Chemical ecology, Evolution

Introduction

Habitat differentiation and niche partitioning significantly contribute to the evolutionary divergence of chemical signals and speciation in insects. The diversification of these signals across populations and species is particularly pronounced in environments with varying climatic or habitat conditions1,2. Insects have developed intricate cuticular chemistry, which is primarily composed of hydrophobic hydrocarbons of different chain lengths (cuticular hydrocarbons, or CHCs), enabling them to thrive in terrestrial environments3. Insects communicate via chemical signals, which can include CHCs or volatile compounds4. Cuticular hydrocarbons are perceived through direct contact or short-range proximity4–6. Male Chorthippus grasshoppers use CHCs to recognize potential mates and touch the body and antennae of females with their antennae before mating7.

In addition to their role in communication, insect CHCs provide essential protection against microbial infections, environmental stress, and desiccation by covering the entire body surface with multiple layers of compounds3,8. These compounds exhibit intra- and interspecific variation and sexual dimorphism, allowing them to be modulated on the basis of environmental conditions9–13.

CHCs, comprising a complex blend of unsaturated hydrocarbons, methyl-branched alkanes, and n-alkanes secreted from arthropod cuticles, also play a vital role in biochemical taxonomy, particularly among social insects11,14–16. Researchers have documented them across various other insect groups, such as grasshoppers Chorthippus sp.,17–20, field crickets Gryllus spp.,21, ants22–24, various Hymenoptera taxa25, and fruit flies Drosophila sp.14,26–29. Despite their widespread occurrence, CHC profiles are challenging for evolutionary biologists because of the striking diversity in composition, even among closely related species12,16,21. This complexity in CHC profiles is a fascinating area of study, demonstrating the intricate roles of CHCs in ecological adaptation and species recognition, underscoring their evolutionary importance across insect taxa.

The reasons for the diversity of CHC profiles in insects remain largely unknown, and the understanding of the selection pressures shaping these profiles is limited. Given the multifunctional nature of CHCs, they may not only mediate interactions within species (e.g., social insects) but also contribute to a species’ ecological niche, encompassing both abiotic factors and biotic interactions. As a result, CHCs may play a role in niche partitioning, especially among closely related species. For example, Schwander et al.30 indicated that changes in CHC profiles can drive speciation, with directional selection on the basis of mate choice influencing divergence processes. Additionally, Rajpurohit et al.28 highlighted that CHCs play a crucial role in desiccation resistance, which may impose selection pressures on these profiles. Furthermore, the interaction between insect pheromones and plant defenses, as discussed by Bittner et al.31, may further complicate our understanding of CHC diversity dynamics.

Studies on various insect species, including the Argentine ant32, the Navel Orangeworm33, and the Western honey bee34, highlight the adaptability and variation of CHC profiles in response to environmental conditions, genetic factors, and social roles. Despite this variability, CHCs also maintain conserved functions, such as colony recognition and communication, often balancing the need for environmental adaptation with maintaining uniform chemical signatures across populations. These findings underscore the multifaceted roles of CHCs and their potential as biomarkers for ecological and pest management applications, offering promising solutions for practical challenges in the field.

In line with the evolutionary importance of CHCs, the species belonging to the genus Isophya (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) provide a valuable case study to investigate the evolutionary and ecological reasons for the differentiation of these hydrocarbons among species, especially in regions where researchers have observed high levels of endemism. Under these conditions, a species is unique to a defined geographic location, such as Anatolia or the Balkans. Orthopterists have reported 90 species of the genus Isophya worldwide35, with 44 found in Anatolia, where an average of 77% are local endemics12,36,37. Owing to their short wings, Isophya species have limited mobility, and their adult lifespan, which lasts for several months, is confined to a small area38. The overall body morphology of Isophya species is similar, and the taxonomic characteristics used for identification are limited, making distinguishing between species with apparent morphological differences challenging. However, in males, the pronotal structure, wings, sound-producing organs, and cerci present relatively distinct features across many species.

In contrast, females possess fewer taxonomically functional structures compared to males. Given these taxonomic difficulties, male calling song characteristics—both temporal and structural—and molecular studies have been frequently employed to differentiate between Isophya species36,39–45. However, complete concordance between morphology, bioacoustic, and molecular findings is rare among species or species groups42,43.

The differentiation and specialization of CHCs among insect species are key components of species-specific communication and behavioral isolation15,16,18,46. CHC profiles vary significantly across species, comprising a unique blend of hydrocarbons that differ in chain length, saturation, and methyl branching14,18,47,48. This chemical diversity suggests that CHC composition evolves through regulatory and genetic modifications, potentially driven by mutations in biosynthetic pathway genes or gene duplications8,18. Sexual dimorphism in CHC profiles, though not always pronounced, significantly influences sexual selection, mediating differential courtship responses and affecting mating outcomes between sexes11,21,27,49. It mediates differential courtship responses and affects mating outcomes between sexes.

The objectives of this study are to focus on several key aspects of CHC variation in Isophya species. First, it aims to investigate how CHC profiles differ between species within two selected Isophya species groups, providing insights into interspecific variation. Second, it analyzes CHC differences at the species group level to uncover differentiation patterns or similarities within and between these groups. Additionally, this study explored sex-based variation in CHC profiles, particularly potential sexual dimorphism in chemical composition. Finally, we explore how mating status is associated with variation in the composition and abundance of CHCs. While our data are descriptive, the observed patterns may inform future studies on the potential roles of these hydrocarbons in reproductive behavior and chemical communication in Isophya. Overall, this study provides a comparative framework to investigate how CHCs vary across species, sex, and mating status—factors potentially linked to species recognition and sexual selection.

Materials and methods

The plump bush crickets

Species of the Isophya genus are plump, short-winged bush crickets (see Supplementary Fig. S1) that inhabit high-altitude grasslands with dense green herbaceous vegetation. Isophya species often inhabit areas mixed with Juniperus communis and Astragalus spp., as well as forest interiors and edges, where they commonly occur on nettles and blackberries12,36. Owing to their restricted movement ability, individuals primarily stay within small, localized areas, making them an ideal model for studying chemical communication, reproductive behaviors, and habitat-specific adaptations.

This study was conducted on several species belonging to the I. zernovi species group, which is distributed in the Eastern Black Sea region and Northeast Anatolia, and the I. rectipennis species group, which is found in the Central and Western Black Sea regions as well as the northern areas of Central Anatolia. These species are considered distinct species groups on the basis of their morphological and molecular differences36,43. A photographic collage presents representative individuals of selected Isophya species from various sampling localities (Supp. Figure 1), highlighting morphological diversity across the zernovi and rectipennis species groups, as well as evident sexual dimorphism between males and females. Additionally, I. staneki, a member of the I. straubei group, exhibited significant morphological distinctions from the other two species groups (including differences in the fastigium, pronotum, male wing, and cercus morphology)36 and was included in the analyses. I. staneki was included to assess the positioning of the CHC profile patterns of the two main species groups.

Field studies

We collected specimens from the I. zernovi group, including I. autumnalis, I. karadenizensis, I. zernovi, and I. bicarinata, from various localities in Turkey (Fig. 1). Data for I. autumnalis came from Gümüşhane Province, where field studies and published research had previously expanded its known distribution. The variation in CHC profiles among the subpopulations of I. autumnalis has been extensively studied and published, providing insights into the chemical diversity within this species12. Additionally, we collected I. karadenizensis from Trabzon, I. zernovi from Erzurum and Artvin, and I. bicarinate from Bayburt provinces. Moreover, specimens from the I. rectipennis species group, including I. rectipennis (Anatolian population of I. rectipennis), I. stenocauda, I. nervosa, I. obenbergeri, and I. ilkazi, were collected from regions such as Bolu, Çorum, Kastamonu, and Çankırı, with detailed fieldwork revealing additional localities and extending known altitudinal distributions for several of these species (Fig. 1). The limited number of I. staneki individuals studied is due to the endemic distribution of the species within a restricted area (Kastamonu Province) and its low population density.

Fig. 1.

Sampling localities of Isophya species analyzed in this study. The figure displays the visited sites where species were identified, with sampling conducted primarily in locations with the highest population densities. The map was created in QGIS (version 3.36.3; https://qgis.org) using publicly available SRTM elevation data, and all layers, symbology, and annotations were manually edited by the authors.

Maintenance of the bush-crickets

For each species, excluding I. staneki, 100 final-instar nymphs of both males and females were collected. The collected specimens were transferred to the laboratory under healthy conditions and were immediately placed in cages for further study. Nymphs were housed separately in species-specific cages, with males and females also kept in distinct 40 × 40 × 30 cm cages and inspected daily. Upon maturation, the nymphs were separated by sex and transferred to smaller 20 × 20 × 25 cm cages, with ten individuals allocated to each cage. We took great care to ensure the proper development of the species, cleaned the cages daily using a brush and alcohol, and maintained a hygienic environment. On the basis of the localities where the samples were collected and previous laboratory experience12,50,51, the bush crickets were fed local vegetation, such as blackberry thorns, nettles, and other plants and flowers. Additionally, their diet was supplemented with lettuce and carrots daily. To preserve the freshness of the collected plants, they were placed in small water-filled containers inside the cages, which functioned like small vases.

Mating experiment

To investigate the effect of mating status (virgin vs. nonvirgin) on the cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles, we applied a standardized mating protocol for each species50,52. Males and females that matured under laboratory conditions were randomly assigned to either virgin or mated groups. Individuals in the virgin group were separated by sex immediately after emergence and housed in same-sex cages (10 individuals per cage) under identical feeding and environmental conditions. These individuals were kept unmated until the end of the experiment and ranged in age from 6 to 8 days. In the mated group, only virgin males and females aged 8 days were used, as individuals below this age are typically less willing to mate52. Mating trials were conducted in cages with a 1:1 sex ratio (e.g., 10 males and 10 females per species). To distinguish individuals, males and females were marked using small labels attached to their hind femurs. All mating pairs were given the opportunity to copulate over a period of 1 to 4 days. After mating, males and females were housed separately in individual cages under the same rearing conditions. To minimize age-related variation, individuals from both groups were preserved when all matings had been completed. The final mean age of both virgin and mated individuals was 13 days. All individuals were stored separately in Eppendorf tubes at − 80 °C until chemical analysis.

CHC extraction and analysis

To establish the CHC profiles of the samples, we utilized methodologies previously employed in Orthoptera research2,12,17,27,53–55. CHC data were collected via a Shimadzu GCMS QP2010 Ultra gas chromatograph‒mass spectrometer (GC‒MS). The samples frozen at − 80 °C were carefully placed in a desiccator for 45 min to reach room temperature and eliminate excess moisture. Each sample was placed entirely in a separate conical glass centrifuge tube, and 4 ml of hexane containing 10 ppm pentadecane (the internal standard) was added. After allowing the solution to sit in hexane for 30 s and vortex for 5 min, the upper layer was extracted via disposable glass pipettes and transferred to the GC/MS for analysis. For the CHC profiles of the bush-crickets, 1 µl of each sample was injected for split-mode (10:1) analysis via a Stabilwax column (Restek/Rtx-5) with a diameter of 30 m and 0.25 mm under helium gas. The analysis commenced at 150 °C for 1 min, followed by a temperature ramp to 250 °C at 15 °C per minute. The temperature was then increased to 320 °C at 3 °C per minute and held for 5 min. The extract was separated based on temperature differences within the column. Component transfer to the GC/MS instrument was performed at 250 °C. Hexane was added daily for analysis to avoid contamination. The peak numbers were coded according to retention times for data analysis. We determined the identities of the primary hydrocarbons by consulting GC/MS libraries (NIST-17 and Willey libraries) and other published sources. Fragmentation profiles were acquired and analyzed via MS and MSD ChemStation software.

The dataset we compiled is comprehensive, containing 829 individuals, 411 identified as female and 418 identified as male, belonging to ten species. With respect to the species group distribution, the rectipennis species group represented by 434 individuals, the zernovi species group represented by 385 individuals, and the I. staneki group represented by 10 individuals. The data are categorized into six groups on the basis of species and sex. The rectipennis species group included 218 females and 216 males. The other species group is zernovi, consisting of 188 females and 197 males. A total of 10 I. staneki Maran, 1958 individuals (5 males and five females) from the Ilgaz Mountains were included in the analysis as representatives of a distinct group (I. straubei species group), which is markedly different from the zernovi and rectipennis species groups36,37. In the rectipennis species group, there are 187 nonvirgin individuals and 247 virgin individuals. In I. staneki, which is represented by a limited number of individuals, the group includes 10 virgin individuals. The analysis of the zernovi species group included 192 nonvirgin individuals and 193 virgin individuals.

Statistical analyses

To investigate inter- and intra-specific variation in cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles, raw GC–MS data were processed to construct individual-by-compound matrices. Peak areas (excluding the internal standard, pentadecane) were normalized to control for extraction variation. Compounds consistently absent or near-zero across samples were excluded. Only CHCs detected in ≥ 10 individuals overall and ≥ 5 per sex were retained, resulting in 21 CHCs for males and 18 for females. A subset of n₃ common CHCs was used to construct a shared PCA space. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed separately for males and females, as well as globally across all individuals using the shared CHCs. Data were log-transformed, mean-centered, and scaled to unit variance. Individual metadata (species, species group, sex, mating status) were linked via sample ID. To visualize clustering patterns and between-group variation, 95% confidence ellipses were overlaid using ggplot256.

Separate one-way ANOVAs were conducted for PC1–PC5 using Species, Sex, and Mating Status (MS) as predictors, including all two- and three-way interactions. When significant three-way interactions (Species × Sex × MS) were detected, pairwise comparisons among species were performed within each Sex × MS group using the emmeans package57, with Holm correction applied to control for family-wise error. To assess within-group variability, the betadisper() function from the vegan package58 was applied to Euclidean distances of PC1–PC5 scores, and differences among species, sexes, and mating status were tested using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD, providing an objective measure of intraspecific CHC heterogeneity. For chemical class-level analyses, CHCs were categorized into six structural classes—n-alkanes, monomethyl- and dimethyl-branched alkanes, alkenes, alkadienes, and unknowns—and their relative abundances (%) were calculated per individual. To examine the effects of sex and mating status on CHC class composition, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were fitted using the lmer() function from the lme4 package59, with sex and MS as fixed effects and species as a random effect; pairwise comparisons were conducted using emmeans with Holm correction. All statistical analyses were performed in RStudio using the packages ggplot2, dplyr, tidyr. A map illustrating the locations where the studied Isophya species were encountered was generated using QGIS, and samples were collected from the most densely populated areas.

All statistical analyses were performed in RStudio60 with ggplot256 used for data visualization and dplyr61 and tidyr62 for data manipulation and tidying. A map showing the locations where the studied Isophya species were encountered was generated using QGIS software63 (version 3.36.3; https://qgis.org) based on Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) elevation data. The samples were collected from the most densely populated areas.

Results

CHC diversity and classification

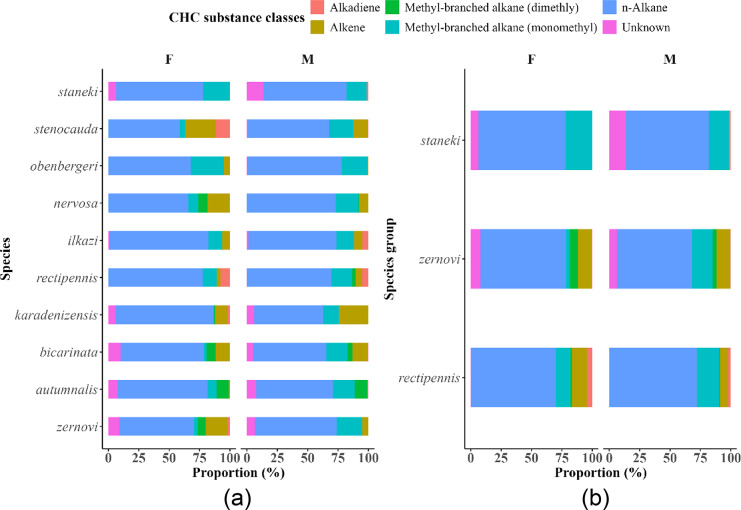

Analysis of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles across Isophya species revealed considerable variation in both the number and composition of CHC classes (Supplementary Table S1). In total, 78 CHC compounds were classified into six structural categories: n-alkanes, methyl-branched alkanes (monomethyl), methyl-branched alkanes (dimethyl), alkenes, alkadienes, and unknowns. The number of CHC classes detected per individual varied across species, with most species exhibiting contributions from five or all six classes. Exceptions included I. staneki, which showed CHCs belonging to only four major classes (n-alkane, monomethyl-branched alkane, alkadiene, and unknown), and I. obenbergeri, where dimethyl-branched alkanes were absent. Quantitatively, n-alkanes were the most dominant CHC class across all species, sexes, and reproductive states, contributing an average of 5–8% to the total CHC profile per individual. Methyl-branched alkanes (monomethyl) also consistently contributed to the profiles of all species, though their relative abundance varied more widely (ranging from ~ 2% to over 16% in I. nervosa females). Alkenes and dimethyl-branched alkanes exhibited species- and sex-specific variability. For example, I. bicarinata females showed elevated alkene contributions (~ 15%), while dimethyl-branched alkanes were most abundant in I. zernovi and I. autumnalis. Alkadienes were the least frequently observed and were generally present in low abundance (typically < 3%) or absent in many female samples. Sex-specific comparisons revealed that males tended to exhibit slightly higher levels of monomethyl-branched alkanes and alkenes in several species (e.g., I. nervosa, I. zernovi), while virgin and nonvirgin individuals differed only marginally in overall CHC class distribution (See Supp.Table 1).

Linear mixed-effects models based on Supp. Table 1 confirmed the class-specific effects of sex and mating status on CHC composition. Alkene proportions were significantly influenced by both sex (F = 8.34, p = 0.004) and mating status (F = 6.45, p = 0.012), while n-alkanes (F = 6.23, p = 0.015) and dimethyl-branched alkanes (F = 5.96, p = 0.018) were significantly higher in females. Monomethyl-branched alkanes were also affected by mating status (F = 9.27, p = 0.003), with a marginal effect of sex (F = 2.88, p = 0.091). No significant sex × mating status interaction was observed in any CHC class, suggesting additive but independent influences.

On average, n-alkanes dominated the CHC profiles across all species, sexes, and mating statuses, contributing between 5 and 8% per individual (Table 1; Figs. 2, 3 and 4). For example, n-alkanes constituted 69.7% of the CHC profile in I. rectipennis females and 71.6% in males, while I. staneki males and females exhibited 68.0% and 71.7%, respectively. Similarly, I. zernovi males showed a notably higher proportion of monomethyl-branched alkanes (17.2%) compared to females (3.29%). These values highlight both species- and sex-specific biases in CHC expression. Methyl-branched alkanes (monomethyl) were consistently present, but with wider interspecific and sex-specific variation—for instance, contributing over 16% in I. nervosa females but as low as ~ 2% in I. stenocauda males. Alkenes showed pronounced species-level differences, with I. bicarinata females exhibiting elevated values (~ 15%), while dimethyl-branched alkanes were especially abundant in I. autumnalis and I. zernovi (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) substance classes and their proportions (%) among males (M) and females (F) of three Isophya species groups (I. rectipennis, I. zernovi, and I. staneki). The CHC classes identified include alkadienes, alkenes, methyl-branched alkanes (dimethyl and monomethyl), n-alkanes, and unknown compounds.

| Species group | CHC substances classes | Sex | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rectipennis | Alkadiene | F | 4.43 |

| rectipennis | Alkadiene | M | 2.13 |

| rectipennis | Alkene | F | 12.1 |

| rectipennis | Alkene | M | 6.78 |

| rectipennis | Methyl-branched alkane (dimethly) | F | 1.44 |

| rectipennis | Methyl-branched alkane (dimethly) | M | 0.612 |

| rectipennis | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | F | 12.1 |

| rectipennis | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | M | 18.4 |

| rectipennis | Unknown | F | 0.186 |

| rectipennis | Unknown | M | 0.437 |

| rectipennis | n-Alkane | F | 69.7 |

| rectipennis | n-Alkane | M | 71.6 |

| zernovi | Alkadiene | F | 1.05 |

| zernovi | Alkadiene | M | 0.369 |

| zernovi | Alkene | F | 10.6 |

| zernovi | Alkene | M | 11.3 |

| zernovi | Methyl-branched alkane (dimethly) | F | 6.51 |

| zernovi | Methyl-branched alkane (dimethly) | M | 3.26 |

| zernovi | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | F | 3.29 |

| zernovi | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | M | 17.2 |

| zernovi | Unknown | F | 8.2 |

| zernovi | Unknown | M | 6.16 |

| zernovi | n-Alkane | F | 70.3 |

| zernovi | n-Alkane | M | 61.7 |

| staneki | Alkadiene | M | 1.54 |

| staneki | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | F | 21.9 |

| staneki | Methyl-branched alkane (monomethy) | M | 16.5 |

| staneki | Unknown | F | 6.36 |

| staneki | Unknown | M | 14 |

| staneki | n-Alkane | F | 71.7 |

| staneki | n-Alkane | M | 68 |

The table highlights the variation in CHC profiles between sexes within each species group, which can indicate potential differences in physiological roles, ecological interactions, or mating signals.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) substance classes in different Isophya species and three species groups. This figure illustrates the relative proportions of CHC substance classes across male and female individuals within Isophya species and species groups. Figure A represents the proportional distribution of CHC classes in individual Isophya species, while Figure B shows the CHC composition in grouped species categories. Each bar segment indicates the proportion of a specific CHC class, highlighting differences in CHC profiles between sexes within each species and group. The CHC classes include alkanes, alkenes, methyl-branched alkanes (dimethyl and monomethyl), unknown compounds, and n-alkanes, providing insights into the chemical diversity and potential ecological or physiological adaptations of Isophya species.

Fig. 3.

Proportions of cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) in unmated (V) and mated (NV) individuals belonging to the Isophya zernovi and Isophya rectipennis species groups. The bars represent different classes of CHCs, with each class indicated by a distinct color in the legend. The percentages within the bars indicate the relative contribution of each CHC class to the total composition.

Fig. 4.

Heatmap of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles across different Isophya species groups and sexes. The x-axis represents individual CHC compounds, whereas the y–axis represents species groups separated by sex. The color gradient indicates the relative percentage of each compound, with darker shades representing higher relative abundances. Species and sex designations include zernovi, rectipennis, and staneki, denoted by “M” (male) and “F” (female). This visualization highlights the variation in CHC composition across species and sexes, providing insight into potential chemotaxonomic differences.

CHC substance class composition varied between virgin and non-virgin individuals (Fig. 3). In virgin individuals (V), n-alkanes constituted the largest proportion of CHC profiles (70%), followed by alkenes (11%), monomethyl-branched alkanes (8%), and dimethyl-branched alkanes (4%). In contrast, non-virgin individuals (N) showed a slightly lower proportion of n-alkanes (67%) and alkenes (9%), but a notably higher proportion of monomethyl-branched alkanes (18%), suggesting a potential enrichment of methyl-branched hydrocarbons after mating. Alkadienes were similarly rare in both groups (3% in virgins, 1% in non-virgins), while the proportion of unknown CHCs remained low and comparable (4% in virgins, 3% in non-virgins). These findings indicate that mating status is associated with subtle shifts in the CHC class composition, particularly in the abundance of methyl-branched compounds.

Representative GC–MS chromatograms illustrating CHC peak profiles of male and female individuals from I. zernovi, I. rectipennis, and I. staneki, each representing one of three species groups, are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2. To further explore sex- and species-specific differences in cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) composition, we visualized the relative percentage of individual CHC compounds across males and females of I. zernovi, I. rectipennis, and I. staneki using a heatmap (Fig. 4). The plot highlights striking inter- and intraspecific variation in CHC profiles, with noticeable differences in both compound richness and relative abundance patterns between sexes and species groups. In general, I. rectipennis males exhibited a broader distribution of CHC compounds with relatively higher within-group heterogeneity compared to I. staneki and I. zernovi. Conversely, I. staneki males showed a more restricted set of CHC compounds, consistent with their lower dispersion in multivariate space. Female profiles also reflected species-specific differentiation, with I. zernovi females displaying a greater number of abundant CHCs relative to the other two species. Several CHCs, such as C31:1, 2-methyltriacontane, and unknown-1, were detected across most groups but differed in relative intensity, suggesting shared yet differentially regulated components. In contrast, some compounds (e.g., C29:2, C27:1) were either absent or present in very low proportions in certain sex–species combinations, indicating possible group-specific roles in signaling or structural functions.

Principal component analysis (PCA), MANOVA and univariate ANOVAs

MANOVA revealed significant multivariate effects of Species, Sex, and Mating Status on CHC profiles (all p < 0.001). Subsequent univariate ANOVAs showed that Species significantly influenced all five principal components (e.g., PC1: F = 20.25, p < 0.001), while Sex had a particularly strong effect on PC1 (F = 695.52, p < 0.001) and PC4 (F = 21.95, p < 0.001). Mating status significantly affected PC1 (F = 13.87, p < 0.001), PC2 (F = 10.22, p = 0.001), and PC5 (F = 5.78, p = 0.016). Interaction terms were also significant, including the three-way interaction (Species × Sex × Mating Status) across PCs (e.g., PC1: F = 7.44, p < 0.001). Univariate ANOVAs were performed on the first five principal components (PC1–PC5) using Species, Sex, and Mating Status (MS) as predictors, including all two-way and three-way interactions. The results are presented in Table 2. The main effects of Species and Sex were statistically significant for all five PCs, except for the effect of Sex on PC5 (p = 0.892). The main effect of Mating Status was significant for PC3 and PC5. Significant two-way interactions were detected for Species × Sex, Species × MS, and Sex × MS in multiple PCs. The three-way interaction (Species × Sex × MS) was significant for PC1 to PC5.

Table 2.

Results of univariate ANOVAs for principal components (PC1–PC5).

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p |

| Species | 916.370 | < 0.001 | 997.580 | < 0.001 | 483.090 | < 0.001 | 106.630 | < 0.001 | 148.370 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 1422.410 | < 0.001 | 187.460 | < 0.001 | 202.910 | < 0.001 | 1333.630 | < 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.892 |

| MS | 0.980 | 0.322 | 1.470 | 0.226 | 14.350 | < 0.001 | 0.760 | 0.383 | 59.830 | < 0.001 |

| Species:Sex | 60.770 | < 0.001 | 17.260 | < 0.001 | 56.180 | < 0.001 | 92.830 | < 0.001 | 42.600 | < 0.001 |

| Species:MS | 4.490 | < 0.001 | 4.090 | < 0.001 | 4.440 | < 0.001 | 7.840 | < 0.001 | 11.680 | < 0.001 |

| Sex:MS | 3.460 | 0.063 | 7.240 | 0.007 | 4.650 | 0.031 | 0.170 | 0.684 | 8.600 | 0.003 |

| Species:Sex:MS | 4.840 | < 0.001 | 3.060 | 0.002 | 2.840 | 0.004 | 5.530 | < 0.001 | 11.790 | < 0.001 |

Each PC was analyzed using a three-way ANOVA with Species, Sex, and Mating Status (MS) as fixed factors. F-values and associated p values are presented for main effects and their interactions. Significant three-way interactions (Species × Sex × MS) indicate that species differences vary depending on both sex and mating status.

Significant values are in bold

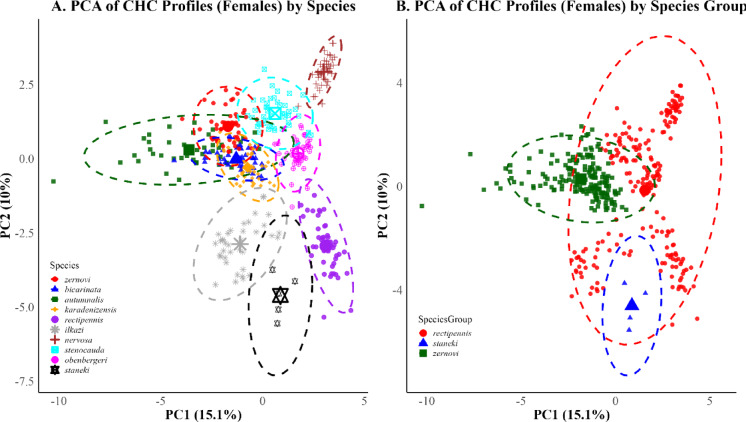

PCA plots for PC1 and PC2 illustrate the overall distribution of CHC profiles by sex and mating status. In males (Fig. 5), clustering patterns were apparent both at the species and species group levels. In females (Fig. 6), similar groupings emerged, although with greater overlap. However, no significant effects of these factors were detected on the first two principal components (two-way ANOVA: all p > 0.1). However, ANOVA results on the first five principal components revealed significant effects of mating status on PC3 and PC5 (Table 2), indicating that variation related to reproductive condition is captured in the subtler axes of CHC variation rather than in the primary components.

Fig. 5.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles in male Isophya individuals. (A) PCA plot showing clustering by species. Members of the zernovi group (except I. bicarinata) exhibit high overlap and tight clustering, whereas species in the rectipennis group display broader dispersion, with I. rectipennis forming a clearly separated cluster. I. staneki is positioned distinctly from both groups. (B) PCA plot showing clustering by species group. The zernovi group forms a compact cluster with minimal dispersion, while the rectipennis group is more broadly distributed. The staneki remains clearly separated. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 6.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profiles in female Isophya individuals. (A) PCA plot showing clustering by species. As in males, zernovi group species display tight clustering within a narrow CHC space, whereas rectipennis group species are more broadly dispersed. I. staneki appears clearly separated from both groups. (B) PCA plot showing clustering by species group. The zernovi group again forms a compact cluster, while the rectipennis group is spread across a wider area in PC space. The staneki is distinctly positioned apart from the others. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals.

To identify which principal components (PCs) contributed to the significant multivariate effects, separate ANOVAs were conducted on PC1–PC5 using Species, Sex, and Mating Status (MS) as predictors, including all interaction terms. For PCs with a significant three-way interaction (Species × Sex × MS), pairwise comparisons among species were performed within each combination of Sex and MS using the emmeans() function with Holm correction (Supp. Table 2). These comparisons revealed significant differences among species across several sex-by-mating status combinations and principal components.

CHC compounds contributing to principal components

The top five CHC contributors for each of the first five principal components (PC1–PC5), along with their absolute loading values and compound classes, are listed in Supp. Table 3. For PC1, the strongest contributors included n-alkanes such as Heptacosane and Pentacosane, as well as methyl-branched alkanes like 2-methyloctacosane and 2-methylhexacosane. PC2 was mainly driven by C38:1 (alkene), C34:CH3 (methyl-branched alkane), and C35:2 (alkadiene). PC3 featured prominent contributions from methyl-branched alkanes (C26:CH3, C28:CH3) and n-alkanes (Hentriacontane, Triacontane). PC4 was characterized by high contributions from n-alkanes including Nanocosan, Triacontane, and Tetratriacontane, while PC5 was influenced by both alkenes (C31:1) and branched alkanes (C30:(CH3)2, C34:CH3).

Intraspecific dispersion and betadisper results

To address potential subjectivity in interpreting visual separation and overlap among species in PCA plots, we employed statistical testing of within-group variability using the betadisper function from the vegan package, based on Bray–Curtis distances. This analysis quantifies group-wise dispersion (i.e., the average distance of samples to their group centroid), allowing for objective comparison of intraspecific variation across species.

The results revealed a significant difference in dispersion among species (ANOVA: F = 59.65, p < 0.001), confirming that species vary in the extent of individual variability in CHC profiles (Figs. 5A, 6A). I. staneki exhibited significantly broader dispersion than several other species, such as I. autumnalis (difference = − 0.127, p < 0.001), I. bicarinata (− 0.186, p < 0.001), and I. karadenizensis (− 0.243, p < 0.001), supporting the earlier visual impression of broader within-species spread (see Supp. Table 3for full pairwise comparisons). Conversely, species such as I. stenocauda and I. ilkazi displayed narrower dispersions, which were not significantly different from one another (p = 1.000). I. rectipennis exhibited significantly broader multivariate dispersion compared to most other species—such as I. autumnalis (− 0.057, p < 0.001), I. bicarinata (− 0.116, p < 0.001), I. karadenizensis (− 0.173, p < 0.001), I. ilkazi (− 0.065, p < 0.001), I. stenocauda (− 0.060, p < 0.001), and I. zernovi (− 0.082, p < 0.001)—but its dispersion was not significantly different from that of I. staneki, I. nervosa, or I. obenbergeri.

Although the initial PCA interpretation mentioned apparent overlap and separation, we now clarify that our statistical analysis formally supports variation in dispersion and thus justifies the differential clustering patterns observed. Additionally, while the number of individuals per species was not equal, we note that betadisper is relatively robust to modest sample size differences, and caution was taken in interpreting clusters with low n.

We also tested group dispersions for sex and mating status. No significant difference in dispersion was found between males and females (F = 2.41, p = 0.121), indicating comparable within-sex variability in CHC expression. However, mating status had a significant effect (F = 7.61, p = 0.006), with nonvirgin individuals exhibiting significantly greater dispersion compared to virgins (Tukey’s HSD: diff = 0.0139, adjusted p = 0.0059), suggesting increased variability in CHC profiles post-mating. This pattern is visually supported in the PCA plot (Supp. Figure 3), where nonvirgin individuals of both sexes appear more dispersed compared to virgins, although there is no distinct separation along the first two principal components.

In addition to species-level comparisons, we assessed multivariate dispersion across species groups. In males, species groups differed significantly in within-group dispersion (ANOVA: F = 20.96, p < 0.001), with the rectipennis group displaying broader dispersion than both the staneki (p < 0.001) and zernovi (p < 0.001) groups (Fig. 5B). The staneki group was also significantly more dispersed than the zernovi group (p = 0.001), supporting the visual impression of a tight zernovi group cluster. A similar pattern emerged in females (ANOVA: F = 10.78, p < 0.001), with significantly higher dispersion in the rectipennis group compared to staneki (p < 0.001), while no significant difference was detected between rectipennis and zernovi (p = 0.97) (Fig. 6B). However, the zernovi group again clustered more tightly than the staneki group (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study revealed significant variability in CHC profiles across Isophya species, with certain CHC classes predominating and others remaining at low levels. These results indicate that CHC composition differs according to species identity and sex, potentially reflecting underlying ecological or physiological differences. While such patterns may align with adaptive explanations, our study does not directly test functional hypotheses. Therefore, any interpretations regarding ecological or reproductive roles should be considered preliminary and warrant further investigation.

CHC diversity and species-specific patterns

The remarkable diversity of CHCs serves critical biological functions, such as communication and desiccation resistance, underscoring their importance in the evolutionary success of insects21,64–66. In the genus Isophya, 78 unique CHC compounds were identified and classified into six distinct types, including n-alkanes, species67. This dominance of n-alkanes is consistent with their known role in waterproofing and environmental adaptation, as observed in other Orthopteran taxa, such as Pamphagus elephas, where n-alkanes constitute more than 72% of CHCs in both sexes68. The variation in CHC profiles reflects both environmental adaptation and evolutionary pressures that shape these chemical signatures69. Notably, I. bicarinata and I. staneki exhibited distinct CHC diversity, with 36 and 17 CHC types, respectively. These species-specific chemical profiles may correspond to differences in ecological niches or reproductive contexts, although functional roles were not directly tested.

Such CHC richness is comparable to that reported in the butterfly Bicyclus anynana, where 103 distinct compounds were identified across body parts, sexes, and ages70. However, unlike B. anynana, which was analyzed by dissecting body parts, our study was based on whole-body CHC extracts, and thus does not capture potential intra-individual spatial variation. In contrast, the zaprochiline tettigoniid Kawanaphila nartee exhibited only 23 compounds, without clear class differentiation49. This variation manifested in compound types; for instance, dimethyl-branched alkanes were enriched in some species, such as I. zernovi, but absent in others, like I. obenbergeri. In K. nartee, sexual dimorphism was limited to chain length differences, with females having longer-chain CHCs. For example, CHC class distributions differed notably between species and sexes: I. staneki females exhibited notably high proportions of monomethyl-branched alkanes, while I. rectipennis and I. zernovi females were characterized by higher n-alkane percentages and moderate alkene content. In males, CHC class proportions were more evenly distributed across species, though I. staneki males had higher levels of uncharacterized CHCs grouped under the “Unknown” category. This trend emphasizes the central role of n-alkanes in Isophya CHC profiles, suggesting their functional relevance across taxa and contexts.

These patterns are not unique to Isophya. Similar CHC class-specific variation has been observed across diverse insect taxa. In Lepidoptera, for instance, Heuskin et al.70 demonstrated that specific cuticular compounds varied according to sex, body part, and age, thereby contributing to chemical discrimination. Likewise, in Macrolophus plant bug species, Gemeno et al.71 found that CHC profiles provided reliable cues for species and sex identification, even under dietary variation. Furthermore, sexual dimorphism in CHC composition has been described in Coleoptera (e.g., Monochamus scutellatus), where hydrocarbon profiles vary with sex and feeding status72. However, since diet or feeding status was not assessed in our study, we cannot determine whether similar physiological influences contribute to CHC variation in Isophya.

The complexity and specificity of Isophya CHC profiles are comparable to the findings in the grasshopper genera, Pamphagus and Chorthippus, where methyl-branch positions and chain lengths significantly influence species and sex differentiation18,68,73. For example, Chorthippus biguttulus and C. mollis separate into species and sexes based on methyl-branched hydrocarbons, with PCA revealing differentiation across principal components18.

In Isophya, notable differences in CHC composition are observed among species groups (zernovi, rectipennis, and staneki). Certain hydrocarbons, such as C27:1 and C33, show notable variations in abundance. Nakano et al.4 underscored the importance of these findings. These authors reported that the migratory locusts Schistocerca gregaria and Locusta migratoria exhibit highly distinct CHC profiles, with certain hydrocarbons being particularly dominant in each species. Moreover, the CHC profiles of Schistocerca and Locusta, as described in their study, were chemically more complex, encompassing a diverse range of hydrocarbons, including methyl-branched alkanes and alkenes. This relative chemical simplicity may reflect ecological differences, as Isophya species exhibit fewer dominant CHCs compared to other genera, such as acridid grasshoppers Chorthippus and Pamphagus. Further functional studies are necessary to clarify the ecological significance of these patterns.

Our findings are consistent with and enriched by insights from studies on other Orthopteran taxa, such as Pamphagus elephas68, Gryllus firmus, and G. pennsylvanicus21. In P. elephas, sex-specific CHC variation was observed, with females producing higher levels of trimethylalkanes, suggesting potential reproductive roles for CHCs. Similarly, our results revealed both sexual dimorphism and interspecific divergence in CHC profiles across Isophya species. In males, members of the zernovi group (excluding I. bicarinata) showed high overlap and tight clustering, whereas rectipennis group species displayed broader dispersion, with I. rectipennis being clearly separated. I. stenocauda, I. ilkazi, and I. obenbergeri formed partially overlapping but distinguishable clusters, and despite I. obenbergeri being treated as a subspecies of I. stenocauda, its CHC profile showed signs of divergence. In females, the zernovi group again exhibited tight clustering, while rectipennis group members were more dispersed. Notably, I. staneki was clearly separated from all others in both sexes. These patterns suggest that CHC profiles capture both sex-based and species-level differences, with potential links to reproductive isolation and chemical signaling. However, further functional studies are needed to clarify whether CHCs directly mediate mate recognition or speciation processes in Isophya. Supporting the taxonomic utility of CHCs, studies on Gryllotalpa mole crickets demonstrated that quantitative CHC differences enabled separation of G. tali and G. marismortui despite qualitative similarity, and that CHCs, when combined with acoustic and chromosomal traits, contributed to robust species delimitation74,75. Similarly, our findings reinforce the integrative value of CHC profiles for resolving species boundaries in closely related taxa and cryptic species complexes.

CHC class distribution and dominance of n-alkanes

Across all the species, n-alkanes were the most abundant CHC class in both sexes, ranging from 56.90% in I. karadenizensis males to 81.24% in I. ilkazi females. This pattern aligns with previous observations suggesting that n-alkanes can form a strong hydrophobic barrier on the cuticle, which helps regulate moisture and prevent desiccation under variable humidity conditions32,67,76. Most of the studied Isophya species inhabit the Black Sea region of Turkey, where rainfall and humidity are relatively high, and the green vegetation cover is denser than in other areas. Furthermore, in comparison with species in Acrididae and Pamphagidae, Isophya species possess visibly softer and thinner cuticles. This anatomical characteristic may be associated with their habitat preferences, as suggested by Khemaissia et al.77 who noted that cuticle thickness could correlate with moisture tolerance. While this observation may help contextualize the high proportion of n-alkanes in Isophya CHC profiles, direct testing of such physiological-environmental associations was beyond the scope of the present study.

Research on Drosophila species has further elucidated the adaptive significance of CHCs. For example, studies have shown that longer-chain hydrocarbons are associated with increased desiccation resistance, a trait that has evolved in response to environmental pressures28,78,79. In D. suzukii, seasonal changes in temperature and photoperiod have been linked to alterations in CHC profiles, affecting mating success and indicating a dynamic response to environmental conditions80. This adaptability is truly remarkable, as it allows insects to optimize their CHC profiles according to their specific habitats, thus increasing their survival and reproductive success28,79. These findings suggest that CHCs may exhibit some plasticity in response to environmental variation. For example, in the rectipennis group, n-alkane levels exceeded 70% in both sexes. In contrast, species in the zernovi group exhibited more variation, with some species, such as I. bicarinata and I. autumnalis, having notably higher alkene levels (up to 16%). These interspecific and intersexual differences suggest that ecological constraints may shape the relative composition of CHC classes in a lineage-specific manner.

While our study does not directly test functional responses, the observed differences in CHC profiles between sexes and species in Isophya may be influenced by ecological or physiological factors. In line with Drosophila studies, these patterns raise the possibility that CHC composition in Isophya varies with habitat characteristics; however, this hypothesis requires further experimental investigation to confirm any adaptive significance.

The CHC profiles also exhibit variability in other classes. Alkenes and, to a lesser extent, dimethyl-branched alkanes are more prominent in species inhabiting wetter climates, such as I. stenocauda and I. karadenizensis. Although the functional roles of these compounds were not examined in this study, previous work has suggested that alkenes may contribute to desiccation resistance. While this function is typically associated with arid environments, it has been proposed that maintaining cuticular integrity and preventing excess water exchange may also be advantageous in humid habitats, where fluctuating microclimatic conditions can influence water balance. The “Unknown” category also shows noticeable variability across species, with I. stenocauda and I. staneki exhibiting higher proportions than the other studied species. While the role of these unknown compounds remains unclear, they may contribute to microbial resistance or complement water-balance regulation under variable moisture regimes67. These variations in other CHC classes, as well as sex-specific and species-specific patterns, highlight the influence of environmental, physiological, and selective pressures.

In our PCA analyses, the primary contributors to PC1–PC5 included long-chain n-alkanes (e.g., Heptacosane, Pentacosane), methyl-branched alkanes (e.g., 2-methyloctacosane, C28:CH3, C34:CH3), and alkenes (e.g., C31:1, C38:1), indicating that interspecific and sex-based differences in CHC profiles are shaped by variation in hydrocarbon chain length and branching patterns. While we did not directly investigate their functional roles, similar patterns have been observed in Drosophila, where variation in chain-elongated and branched CHCs contributes to sex-specific signaling and mating outcomes, for example, Luo et al.81 demonstrated that male-biased long-chain alkenes such as 9-pentacosene and 9-heptacosene reduce female attractiveness when artificially applied, highlighting the behavioral impact of chain-elongated hydrocarbons. In parallel, Dembeck et al.82 identified extensive natural genetic variation in D. melanogaster CHC profiles, driven by genes involved in fatty acid metabolism and elongation, including previously uncharacterized loci that modulate chain length and composition. Together, these patterns were particularly pronounced in males of I. staneki, which exhibited elevated levels of long-chain CHCs and unclassified compounds, suggesting that similar evolutionary forces (e.g., sexual selection, ecological adaptation) may underlie hydrocarbon profile divergence in Isophya. Although we did not assess behavioral effects directly, our findings support the hypothesis that both genetic and environmental factors shape involved in sexual communication.

Sex-based and mating status-dependent differences in CHC profiles

The multivariate analysis of Isophya CHC profiles revealed significant effects of species, sex, mating status, and their interactions. Species identity had the strongest overall effect across PCs. This finding is consistent with the literature that emphasizes the role of CHCs in species recognition and sexual selection among insects55,83. A significant species-by-sex interaction suggests that CHC profiles vary between males and females in a species-specific manner. While such patterns may be consistent with sex-specific chemical signaling, the current study does not directly assess behavioral outcomes. Notably, sex had a strong effect on PC1, indicating pronounced sexual dimorphism in CHC profiles within Isophya species. This finding is consistent with previous studies on Teleogryllus oceanicus, where males and females exhibited distinct CHC compositions, likely shaped by sexual selection84.

Mating status (MS) contributed to CHC variation, although its overall influence was more restricted compared to the dominant effects of species and sex. Rather than producing a uniform shift across all chemical axes, the influence of mating status appeared selectively expressed in specific components of multivariate variation. Moreover, significant interactions between species, sex, and mating status indicate that a combination of sexual dimorphism, reproductive condition, and species-specific factors may influence the expression of CHCs. This observation parallels findings in sagebrush grig Cyphoderris strepitans and the stingless bee Melipona scutellaris, where CHC profiles vary with mating history55,85.

Moreover, our findings align with those of a study on D. melanogaster, where mating status altered CHC profiles through three potential mechanisms, including the transfer of cuticular and seminal hydrocarbons from males during copulation26,86. These transferred compounds reduce the female’s attractiveness and modulate her receptivity to future matings. Notably, however, the experimental design in our study differs in an important aspect: in Isophya, males transfer a spermatophore consisting of an ampulla and a protein-rich spermatophylax, which females typically consume after copulation50,87. In our experimental setup, the consumption of the spermatophylax was prevented to control for nutritional or post-copulatory chemical influences. This distinction may have limited the degree or nature of CHC modulation observed in our study compared to systems like Drosophila, where ejaculate-associated compounds are fully transferred and retained.

Likewise, studies on other Diptera, such as Dasineura oleae, have described comparable shifts in CHC composition associated with mating status9. The significant species:sex:mating status interaction suggests that CHC expression is modulated not only by sexual dimorphism and mating history but also by species-specific factors. This pattern is consistent with the dual role of CHCs proposed in previous work10,64. While our findings are consistent with such patterns, we emphasize that our data are descriptive, and no functional or mechanistic interpretations can be inferred without additional experimental validation.

Additionally, studies on the meadow grasshopper species Chorthippus biguttulus and C. mollis have indicated that CHC profiles differ significantly between sexes, with PC2 explaining a substantial portion of the variation between males and females18. The observation that PC2 also significantly separated the sexes in our Isophya dataset supports the generality of CHC-based sexual dimorphism across Orthoptera. Furthermore, the significant species:sex interaction in our results mirrors findings in Chorthippus, where CHC divergence is species- and sex-dependent. The parallel between our findings and those in Chorthippus, particularly the significant species-by-sex interaction, suggests that sex-related variation in CHC composition may be a broader phenomenon among Orthoptera. However, further research is needed to confirm this in Isophya. In summary, our PCA results demonstrate that CHC composition in Isophya is significantly influenced by species identity, sex, and mating status.

Alkenes and alkadienes, though less dominant, show interesting patterns related to sex differences. In species such as I. stenocauda, females have exceptionally high proportions of alkenes and alkadienes, whereas males present significantly lower percentages. These unsaturated hydrocarbons, due to their higher permeability to water vapor, have been proposed to play roles beyond moisture retention, possibly in chemical signaling or mate recognition10. Although this study does not directly test these roles, the observed sex-based differences in alkene and alkadiene abundance may be consistent with such functions, as reported in other insect taxa67. Methyl-branched alkanes, particularly monomethyl-branched alkanes, are prominent in several species, with males often having higher levels than females. For example, I. zernovi males presented 20.89% monomethyl-branched alkanes, whereas females presented 2.87% monomethyl-branched alkanes. This dimorphism suggests that methyl-branched hydrocarbons could function in intersexual communication, potentially as pheromonal signals88. The presence of these compounds in relatively humid environments may therefore support dual functions—enhancing mating behavior through distinct scent profiles, while also providing a protective barrier that stabilizes cuticular permeability10.

Sexual dimorphism and post-mating effects were also more structurally diverse in Isophya. For example, dimethyl-branched alkanes were notably enriched in I. staneki females, while nonvirgin individuals across several groups showed increased monomethyl-branched alkanes. These findings underscore that CHC expression in Isophya is not only modulated by mating history but also strongly influenced by phylogenetic lineage and habitat-specific factors—each species group occupying ecologically distinct zones that may drive CHC divergence through selection. However, their specific functions remain to be tested in Isophya. Similar sex-specific differences in CHC abundance have been reported in White-spotted Sawyer Monochamus scutellatus, where both sexes possess the same hydrocarbon compounds. Yet, their relative proportions differ significantly—particularly in monoenes and methyl-branched alkanes72. Moreover, the quantity of CHCs increases markedly in maturation-fed females compared to unfed ones, suggesting that physiological states such as nutritional status can modulate CHC expression. These results reinforce the idea that CHC profiles are shaped not only by sex and species but also by ecological and physiological conditions. CHC composition, shaped by species identity, sex, and mating status, appears to serve dual functions in sexual selection and ecological adaptation, as also proposed in prior studies across Orthoptera and Diptera.

In addition to differences in CHC class composition across species and sexes, we also found notable variation in within-group CHC dispersion. Our betadisper analysis revealed that particular species, such as I. staneki and I. rectipennis, exhibited significantly broader intraspecific dispersion compared to others like I. autumnalis, I. stenocauda, or I. ilkazi. This elevated variability may reflect greater ecological plasticity or developmental heterogeneity in CHC expression. Notably, the rectipennis species group also displayed higher within-group dispersion compared to other species groups in both sexes, reinforcing the idea that lineage-specific traits and habitat heterogeneity may shape CHC variability. These findings are consistent with89, who highlighted that environmental factors, such as diet, microclimate, and humidity, as well as life stage and physiological state, can significantly modulate CHC expression and increase within-species variation in insects. Conversely, the tightly clustered CHC profiles in species like I. zernovi may indicate more canalized or environmentally constrained hydrocarbon expression. Furthermore, mating status significantly influenced CHC dispersion: nonvirgin individuals showed greater within-group variability than virgins, suggesting that post-mating physiological or chemical changes contribute to increased individual heterogeneity. These results highlight that, beyond categorical differences, CHC profiles also vary in the extent of individual-level variability—a feature that may play a role in fine-tuning mate choice or signaling robustness in natural populations. Overall, while these results suggest intriguing patterns, further experimental studies are needed to clarify whether these CHC classes contribute to mating behavior, chemical communication, or environmental adaptation.

Evolutionary and ecological implications

The dominance of n-alkanes across Isophya species suggests a conserved role in desiccation resistance. At the same time, the diversity of methyl-branched alkanes and alkenes may reflect evolutionary divergence in chemical signaling. These findings highlight the ecological relevance of CHCs in species differentiation and adaptation among Orthoptera. As in other insects, Isophya CHCs form a hydrophobic cuticular barrier critical for water retention, especially in variable environments. The relative abundance of long-chain and branched hydrocarbons in Isophya aligns with patterns seen in montane and arid-adapted insects, where such compounds enhance moisture retention. These results support previous findings emphasizing the dual role of CHCs in both adaptation and communication.

Isophya species typically inhabit humid regions, such as the Black Sea and the Balkan highlands. However, some populations, such as I. sikorai and I. savignyi from the arid regions, emerge during rainy seasons, suggesting plasticity in CHC expression in response to seasonal moisture—a phenomenon also observed in other insects like rice planthoppers. Distinct CHC compositions among species likely reflect habitat associations. For example, I. karadenizensis shows high n-alkane content, which may contribute to regulating cuticular permeability in humid areas rather than strictly conserving water as in xeric conditions. Conversely, I. stenocauda females exhibit elevated alkenes, possibly indicating a balance between desiccation and signaling, while I. rectipennis females have notable levels of alkadienes that may serve habitat- or mating-related functions.

Species group-level CHC patterns support the role of ecological differentiation: staneki group in montane steppe, zernovi in humid forest edges, and rectipennis in transitional zones. These associations may drive selection on cuticular chemistry. Additionally, as observed by9 in the gall midge Dasineura oleae, some CHC components may originate from ecological exposure or dietary uptake during development.

The greatest CHC diversity in I. bicarinata and the lowest in I. staneki reflect broader trends, and suggesting that ecological factors influence chemical variation. The consistent dominance of n-alkanes across species—over 60% in most cases—mirrors findings in other grasshoppers (e.g., Chorthippus) and may represent an adaptive trait for desiccation resistance. In sum, our research revealed that Isophya CHC profiles are shaped by a combination of species identity, habitat conditions, and potentially seasonal environmental factors. While patterns suggest ecological plasticity, further research is needed to determine the adaptive significance of these patterns.

Conclusion

This study highlights the ecological and evolutionary relevance of cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) in Isophya species, revealing significant interspecific variation, sexual dimorphism, and mating status-dependent differences in CHC profiles. The dominance of n-alkanes and the species-specific distribution of methyl-branched alkanes and alkenes suggest adaptive roles in desiccation resistance and chemical communication. While most Isophya species inhabit humid environments, some populations in arid regions exhibit CHC traits potentially shaped by seasonal moisture availability, indicating ecological plasticity. Distinct CHC compositions across species and species groups appear linked to habitat differences, reflecting selection pressures on cuticular chemistry. However, these functional interpretations remain speculative without validation through behavioral or physiological studies. Notably, the univoltine life cycle of Isophya reduces the likelihood of strong seasonal effects on CHC expression, though dietary influences across habitats remain an open question.

In conclusion, the variation in CHCs in Isophya offers valuable insights into the chemical diversification of Orthoptera. However, these functional interpretations remain speculative and require validation through behavioral or physiological studies. Notably, the univoltine life cycle of bushcrickets, such as the genera Isophya and Poecilimon, reduces the likelihood of strong seasonal effects on CHC expression. However, dietary influences across habitats remain an open question.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hülya ÖZDEMİR and Ebru Kıran ÖZDEMİR for their help during the lab process. We would also like to thank B. Gökçen MAZI, Hüseyin UZUNÖMEROĞLU and İlhan İRENDE from Ordu University, Central Research Laboratory for their help and patience during the GC-MS studies.

Author contributions

H. S. conceived and coordinated the study, conducted the fieldwork, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. E. B. conducted the CHC laboratory procedures and assisted in the CHC analyses. E. A. participated in some fieldwork and contributed to the CHC analyses in the laboratory.

Funding

The funding was provided by Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu (No. 117Z068).

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All Isophya species used in the study were collected from the field with the permission of the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks. We properly fed all bush crickets without cruelty during their transportation from the field to the laboratory until GC–MS analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steiger, S. & Stökl, J. The role of sexual selection in the evolution of chemical signals in insects. Insects5, 423–438 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas, M. L., Gray, B. & Simmons, L. W. Male crickets alter the relative expression of cuticular hydrocarbons when exposed to different acoustic environments. Anim. Behav.82, 49–53 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard, R. W. & Blomquist, G. J. Ecological, behavioral, and biochemical aspects of insect hydrocarbons. Annu. Rev. Entomol.50, 371–393 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano, M., Morgan-Richards, M., Trewick, S. A. & Clavijo-McCormick, A. Chemical ecology and olfaction in short-horned grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae). J. Chem. Ecol.48, 121–140 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ely, S. O. et al. Mate location mechanism and phase-related mate preferences in solitarius desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. J. Chem. Ecol.32, 1057–1069 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finck, J. & Ronacher, B. Components of reproductive isolation between the closely related grasshopper species Chorthippus biguttulus and C. mollis. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.71, 70 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finck, J., Kuntze, J. & Ronacher, B. Chemical cues from females trigger male courtship behaviour in grasshoppers. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol.202, 337–345 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomquist, G. J. & Bagneres, A. G. Insect Hydrocarbons: Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemical Ecology (Cambridge University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caselli, A., Favaro, R., Petacchi, R., Valicenti, M. & Angeli, S. The cuticular hydrocarbons of Dasineura oleae show differences between sex, adult age and mating status. J. Chem. Ecol.10.1007/s10886-023-01428-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, H. & Carroll, S. B. Wax, sex and the origin of species: Dual roles of insect cuticular hydrocarbons in adaptation and mating. BioEssays37, 822–830 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennings, J. H., Etges, W. J., Schmitt, T. & Hoikkala, A. Cuticular hydrocarbons of Drosophila montana: Geographic variation, sexual dimorphism and potential roles as pheromones. J. Insect Physiol.61, 16–24 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Özdemir, E. K., Sevgili, H. & Bağdatlı, E. Diversity in body size, bioacoustic traits, and cuticular hydrocarbon profiles in Isophya autumnalis populations. JOR33, 233–248 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menzel, F., Schmitt, T. & Blaimer, B. B. The evolution of a complex trait: cuticular hydrocarbons in ants evolve independent from phylogenetic constraints. J. Evol. Biol.30, 1372–1385 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard, R. W., Jackson, L. L., Banse, H. & Blows, M. W. Cuticular hydrocarbons of Drosophila birchii and D. serrata: Identification and role in mate choice in D. serrata. J. Chem. Ecol.29, 961–976 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore, H. E., Hall, M. J. R., Drijfhout, F. P., Cody, R. B. & Whitmore, D. Cuticular hydrocarbons for identifying Sarcophagidae (Diptera). Sci. Rep.11, 7732 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kather, R. & Martin, S. J. Cuticular hydrocarbon profiles as a taxonomic tool: Advantages, limitations and technical aspects. Physiol. Entomol.37, 25–32 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neems, R. M. & Butlin, R. K. Variation in cuticular hydrocarbons across a hybrid zone in the grasshopper Chorthippus parallelus. Proc. Biol. Sci.257, 135–140 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finck, J., Berdan, E. L., Mayer, F., Ronacher, B. & Geiselhardt, S. Divergence of cuticular hydrocarbons in two sympatric grasshopper species and the evolution of fatty acid synthases and elongases across insects. Sci. Rep.6, 33695 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman, R. F., Espelie, K. E. & Peck, S. B. Cuticular hydrocarbons of grasshoppers from the Galapagos Islands. Ecuador. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.28, 579–588 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman, R. F., Espelie, K. E. & Sword, G. A. Use of cuticular lipids in grasshopper taxonomy: A study of variation in Schistocerca shoshone (Thomas). Biochem. Syst. Ecol.23, 383–398 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heggeseth, B., Sim, D., Partida, L. & Maroja, L. S. Influence of female cuticular hydrocarbon (CHC) profile on male courtship behavior in two hybridizing field crickets Gryllus firmus and Gryllus pennsylvanicus. BMC Evol. Biol.20, 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronchetti, F., Schmitt, T., Romano, M. & Polidori, C. Cuticular hydrocarbon profiles in velvet ants (Hymenoptera: Mutillidae) are highly complex and do not chemically mimic their hosts. Chemoecology33, 29–43 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whyte, B. A. et al. The role of body size and cuticular hydrocarbons in the desiccation resistance of invasive Argentine ants (Linepithema humile). J. Exp. Biol.226, 245578 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berville, L. et al. Differentiation of the ant genus Tapinoma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Mediterranean Basin by species-specific cuticular hydrocarbon profiles. Myrmecol. News18, 77–92 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kather, R. & Martin, S. J. Evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons in the Hymenoptera: A meta-analysis. J. Chem. Ecol.41, 871–883 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everaerts, C., Farine, J.-P., Cobb, M. & Ferveur, J.-F. Drosophila cuticular hydrocarbons revisited: Mating status alters cuticular profiles. PLoS ONE5, e9607 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veltsos, P., Wicker-Thomas, C., Butlin, R. K., Hoikkala, A. & Ritchie, M. G. Sexual selection on song and cuticular hydrocarbons in two distinct populations of Drosophila montana. Ecol. Evol.2, 80–94 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajpurohit, S. et al. Adaptive dynamics of cuticular hydrocarbons in Drosophila. J. Evol. Biol.30, 66–80 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis, J. S., Pearcy, M. J., Yew, J. Y. & Moyle, L. C. A shift to shorter cuticular hydrocarbons accompanies sexual isolation among Drosophila americana group populations. Evol. Lett.5, 521–540 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwander, T. et al. Hydrocarbon divergence and reproductive isolation in Timema stick insects. BMC Evol. Biol.13, 151 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bittner, N., Hundacker, J., Achotegui-Castells, A., Anderbrant, O. & Hilker, M. Defense of Scots pine against sawfly eggs (Diprion pini) is primed by exposure to sawfly sex pheromones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 24668–24675 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buellesbach, J. et al. Desiccation resistance and micro-climate adaptation: Cuticular hydrocarbon signatures of different Argentine Ant supercolonies across California. J. Chem. Ecol.44, 1101–1114 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngumbi, E. N., Hanks, L. M., Suarez, A. V., Millar, J. G. & Berenbaum, M. R. Factors associated with variation in cuticular hydrocarbon profiles in the Navel Orangeworm, Amyelois transitella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Chem. Ecol.46, 40–47 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-León, D. S. et al. Deciphering the variation in cuticular hydrocarbon profiles of six European honey bee subspecies. BioRxiv10.1101/2024.07.05.601031 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cigliano, M. M., Braun, H., Eades, D. C. & Otte, D. Orthoptera Species File. Version 5.0/5.0. http://orthoptera.speciesfile.org/HomePage/Orthoptera/HomePage.aspx (2023).

- 36.Sevgili, H. A revision of Turkish species of Isophya Brunner von Wattenwyl (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Phaneropterinae) (Hacettepe University, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heller, K.-G. Bioakustik der europäischen Laubheuschrecken 358–358 (J. Margraf, 1988).

- 38.Nuhlíčková, S., Svetlík, J., Kaňuch, P., Krištín, A. & Jarčuška, B. Movement patterns of the endemic flightless bush-cricket Isophya beybienkoi. J. Insect Conserv.10.1007/s10841-023-00529-0 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhantiev, R., Korsunovskaya, O. & Benediktov, A. Acoustic signals of the bush-crickets Isophya (Orthoptera: Phaneropteridae) from Eastern Europe, Caucasus and adjacent territories. Eur. J. Entomol.114, 301–311 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sevgili, H., Çiplak, B., Heller, K. G. & Demirsoy, A. Morphology, bioacoustics and phylogeography of the Isophya major group (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Phaneropterinae): A species complex occurring in Anatolia and Cyprus. Eur. J. Entomol.103, 657–671 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orci, K. M., Nagy, B., Szövényi, G., Rácz, I. A. & Varga, Z. A comparative study on the song and morphology of Isophya stysi and Isophya modestior (Orthoptera, Tettigoniidae). Zoologischer Anzeiger–J. Comp. Zool.244, 31–42 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grzywacz-Gibała, B., Chobanov, D. P. & Warchałowska-Śliwa, E. Preliminary phylogenetic analysis of the genus Isophya (Orthoptera: Phaneropteridae) based on molecular data. Zootaxa2621, 27–44 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chobanov, D. P., Kaya, S., Grzywacz, B., Warchałowska-Śliwa, E. & Çıplak, B. The Anatolio-Balkan phylogeographic fault: A snapshot from the genus Isophya (Orthoptera, Tettigoniidae). Zool. Scr.46, 165–179 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sevgili, H. Bioacoustics and morphology of a new bush-cricket species of the genus Isophya (Orthoptera: Phaneropterinae) from Turkey. Zootaxa4514, 451–472 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sevgili, H. Isophya sonora, a new bush-cricket species from Eastern Black Sea region of Turkey (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae; Phaneropterinae). Zootaxa4860, zootaxa.4860.2.9 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Martin, S. J., Helanterä, H. & Drijfhout, F. P. Evolution of species–specific cuticular hydrocarbon patterns in Formica ants. Biol. J. Lin. Soc.95, 131–140 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blomquist, G. J. & Ginzel, M. D. Chemical ecology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of insect hydrocarbons. Annu. Rev. Entomol.66, 45–60 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dos Santos, A. B. & Nascimento do, F. S. Cuticular hydrocarbons of orchid bees males: Interspecific and chemotaxonomy variation. PLoS ONE10, e0145070 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hare, R. M., Larsdotter-Mellström, H. & Simmons, L. W. Sexual dimorphism in cuticular hydrocarbons and their potential use in mating in a bushcricket with dynamic sex roles. Anim. Behav.187, 245–252 (2022). [Google Scholar]