Abstract

GBA is the major risk gene for Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), two common α-synucleinopathies with cognitive deficits. Here we investigate the role of mutant GBA in cognitive decline by utilizing Gba (L444P) mutant, SNCA transgenic (tg), and Gba-SNCA double mutant mice. Notably, Gba mutant mice show cognitive decline but lack PD-like motor deficits or α-synuclein pathology. Conversely, SNCA tg mice display age-related motor deficits, without cognitive abnormalities. Gba-SNCA mice exhibit both cognitive decline and exacerbated motor deficits, accompanied by greater cortical phospho-α-synuclein pathology, especially in layer 5 neurons. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing of the cortex uncovered synaptic vesicle (SV) endocytosis pathway defects in excitatory neurons of Gba mutant and Gba-SNCA mice, via downregulation of genes regulating SV cycle and synapse assembly. Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy validate these findings. Our results indicate that Gba mutations, while exacerbating pre-existing α-synuclein aggregation and PD-like motor deficits, contribute to cognitive deficits through α-synuclein-independent mechanisms, involving dysfunction in SV endocytosis.

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, Dementia

GBA, a major gene for Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, is associated with increased risk of developing dementia. Here, we demonstrate that GBA mutations in mice contribute to cognitive deficits through α-synuclein-independent mechanisms that impact synaptic vesicle endocytosis.

Introduction

GBA is the major risk gene for Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)1–6, two late-onset neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by the neuronal accumulation of Lewy bodies composed of α-synuclein7. PD is classified as a movement disorder, although dementia affects around 50% of PD patients within 10 years after symptom onset7. DLB is a dementia, in which cognitive decline is generally the first and most predominant symptom7. Significantly, PD patients with GBA mutations exhibit greater and faster cognitive decline than idiopathic PD1,7–9. Cognitive dysfunction in both PD and DLB, which entails visuospatial, memory, and executive dysfunction, is strongly correlated with neocortical Lewy pathology7. However, the mechanisms through which GBA predisposes to cognitive dysfunction, as well as to developing α-synucleinopathies in general, are not well understood.

Homozygous or biallelic mutations in GBA cause the lysosomal storage disorder, Gaucher disease (GD)10,11. Two prevalent mutations, due to founder effects, are N370S (p.N409S) and L444P (p.L483P) (without and with the 39AA leader sequence)12,13. GD patients have a 20-fold increased risk of developing PD accompanied by exacerbated cognitive decline. Heterozygous carriers of GBA mutation are at 5-fold increased risk for developing both PD and cognitive dysfunction1,2,8,9,14–18. In the case of DLB, GBA and SNCA, the gene for α-synuclein, are top GWAS hits. Interestingly, GBA mutations confer an even higher risk of developing DLB4–6. GBA encodes glucocerebrosidase 1 (GCase1), a lysosomal hydrolase responsible for breaking down the bioactive lipid glucosylceramide (GlcCer) to glucose and ceramide. In the absence of GCase1, GlcCer and other glycosphingolipids accumulate. Interestingly, GCase1 deficiency and glycosphingolipid accumulation are also observed in post-mortem brains of patients with sporadic PD and in aging brains19–22. Glycosphingolipid accumulation correlates with a higher burden of α-synuclein or Lewy pathology in several brain areas20,22,23. These genetic, clinical, and epidemiological studies emphasize the importance of understanding mechanisms of GBA-linked cognitive dysfunction.

The prevailing hypothesis in the field is that GBA mutations lead to GCase1 deficiency, which, through a combination of lysosomal dysfunction and glycosphingolipid accumulation, trigger α-synuclein aggregation, resulting in Lewy body formation and consequently, disease associated phenotypes. We and others have shown that glycosphingolipids can directly interact with α-synuclein and promote aggregation in vitro24,25. Our long-lived mouse models of GD carrying the Gba N370S and L444P mutations exhibited reduced GCase1 activity and accumulation of glycosphingolipids in the liver, spleen, and brain26. As GD patients with the L444P mutation have pronounced cognitive deficits27, in this study, we conducted a thorough examination of Gba L444P mice, in conjunction with the well-established SNCA tg PD mice that overexpress mutant human α-synuclein, and their crossbreeds, i.e. Gba-SNCA mice. Based on our findings, we suggest that synaptic endocytosis dysfunction plays a role in cognitive deficits of GBA-linked PD and DLB.

Results

Gba mutation leads to cognitive dysfunction and exacerbates motor deficits in SNCA tg mice

To determine the relative contributions of GBA and SNCA in motor and cognitive domains, we performed behavioral analyses of wild-type (WT), Gba, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mouse sex-balanced cohorts. We conducted longitudinal evaluations of motor behavior every 3 months to establish the age of onset and progression of PD-like motor deficits compared to cognitive behavior deficits.

Motor deficits were phenotyped using four complementary assays: balance beam, grip strength, hind limb clasping, and open-field locomotion tests. In the balance beam test, number of runs completed in a minute and the average time per run were used to assess motor performance28 (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A, D, E). Gba mice consistently performed well on this task, comparable to WT mice, up to 12 months. In contrast, SNCA tg mice could perform this task at 3 months but began showing deficits at 6 months, which worsened by 12 months. Notably, Gba-SNCA mice demonstrated exacerbated balance beam deficits compared to SNCA tg mice, with significant deficits appearing as early as 6 months. By 9-12 months, Gba-SNCA mice were severely affected and unable to navigate the balance beam (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A, D, E). We noted similar deficits in grip strength. WT and Gba mice did not show deficits, while SNCA tg mice developed age-related decline in grip strength, which was exacerbated in Gba-SNCA mice (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1B, F, G). In hind limb clasping test, SNCA tg mice did not show clasping, similar to WT (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1H). Gba mice showed a trend towards increased clasping, whereas Gba-SNCA mice showed a significant increase across all ages, indicating a synthetic motor phenotype (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1H). In the open field, distance traveled was comparable among all groups across ages, except for Gba-SNCA mice (Fig. 1D). At 9 months, a significant loss in exploration/locomotion was noted in Gba-SNCA mice, which worsened at 12 months (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1I). No genotypes showed anxiety-like behavior, as evaluated by the time spent in the inner/outer circles of the open field (Supplementary Fig. 1C). There was no difference across the mice strains for body weight, however, Gba-SNCA mice stopped gaining weight after 6 months (Supplementary Fig. 1J). In summary, motor assessments demonstrate that Gba mutants do not exhibit any appreciable motor deficits. Nonetheless, Gba mutation significantly exacerbates existing age-related motor deficits in SNCA tg mice.

Fig. 1. Gba mutation worsens motor deficits in SNCA tg mice and independently leads to cognitive dysfunction.

WT, Gba, SNCA tg and Gba-SNCA mice cohorts were evaluated in four motor and two cognitive behavior tests in a longitudinal manner. A Balance beam behavior. B Grip strength of all four limbs. C Hind limb clasping behavior. D Open field locomotory behavior. E Fear conditioning test. F Novel object recognition. n = 9-12 mice for motor behavior and 6-19 for cognitive behavior, both sexes were used. For A–F, two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used. Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction was used for (E) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for (F). ‘*’ indicates p-value. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns not significant; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Next, we evaluated the impact of Gba and SNCA mutations on cognition by employing fear conditioning and novel object recognition (NOR) tests. To avoid confounds due to learning, we performed these on two separate sets of mice at 3 months and 12 months, prior to and after the onset of motor deficits in SNCA tg mice (Fig. 1A–D). For fear conditioning, mice were habituated to operant boxes and exposed to paired tone and shock stimuli on the training day, with freezing responses to the tone alone measured 24 hours later. We counted the number of freeze episodes after start of the tone and observed a conditioned fear response in WT and SNCA tg mice at both 3 and 12 months (Fig. 1E). However, Gba and Gba-SNCA mice did not show a significant response on the testing day, especially at 12 months. While this is suggestive of cognitive impairment, the results were confounded by the heightened freezing response shown by Gba and Gba-SNCA mice for aversive stimulus on the training day (Fig. 1E).

To substantiate the cognitive findings from fear conditioning, we performed a NOR test to assess recognition memory. Mice spend more time with the novel object when cognitively normal (Fig. 1F). Gba mice spent significantly less time with the novel object at 3 months and maintained this behavior at 12 months, suggesting an early cognitive impairment (Fig. 1F). As Gba mice do not have motor problems, these results reflect memory impairments. Interestingly, SNCA tg mice did not show deficits in the NOR test (Fig. 1F), whereas Gba-SNCA do, which was comparable to Gba mice (Fig. 1F). Thus, our cognitive behavior assays suggest that the Gba mutation alone can cause cognitive impairment, with the poor cognition in Gba-SNCA mice likely driven by Gba mutation.

Gba mutation exacerbates cortical α-synuclein pathology of SNCA tg mice

In Lewy body pathology, α-synuclein is phosphorylated at Ser129, forms aggregates, and accumulates in the soma, whereas under normal conditions, it is primarily localized to presynaptic termini. To investigate whether Gba-mediated cognitive deficits and accelerated motor deficits are associated with α-synuclein pathology, we performed immunohistochemistry on 3- and 12-month-old mice brains, staining for α-synuclein, pSer129α-syn, and the neuronal marker NeuN. We found that Gba mice did not exhibit increased α-synuclein levels in the soma, or accumulation of pathological pSer129α-syn in the cortex both at 3 and 12 months (Fig. 2A–C). Similar observations were made in the CA1 hippocampus and by Western blotting of whole brain homogenates (Supplementary Fig. 2C–J). These findings suggest that the Gba mutation alone is insufficient to cause widespread α-synuclein pathology at these ages.

Fig. 2. Gba mutation exacerbates α-synuclein pathology in the cortices of SNCA tg mice.

A Representative images of cortices of WT, Gba, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mice (12 months) immunostained for NeuN (red), α-synuclein (magenta) and pSer129-α-syn (green). Note increased α-synuclein levels (arrow) and pSer129-α-syn expression in the neuronal soma of Gba-SNCA double mutant when compared to SNCA tg mice. Scale = 150 µm. Inset scale = 15 µm. B Cortical α-synuclein expression at 3 and 12 months, normalized to respective WT average at each time point. C Cortical pSer129-α-syn expression at 3 and 12 months, normalized to respective WT average at each time point. D Percentage of cortical neurons positive for pSer129-α-syn at 3 and 12 months. E NeuN positive cortical neuronal number at 3 and 12 months. F Distribution of pSer129-α-syn expression intensity (Range of 0-255) in the cortical neurons at 3 months of age (WT: Mean = 0.35, 25% Percentile = 0.0024, 75% Percentile = 0.1252; Gba: Mean = 0.04, 25% Percentile = 0, 75% Percentile = 0.0058; SNCA tg: Mean = 13.05, 25% Percentile = 5.211, 75% Percentile = 18.534; Gba-SNCA: Mean = 23.781, 25% Percentile = 9.221, 75% Percentile = 33.972) and, G 12 months of age (WT: Mean = 1.28, 25% Percentile = 0.439, 75% Percentile = 1.731; Gba: Mean = 1.482, 25% Percentile = 0, 75% Percentile = 2.124; SNCA tg: Mean = 26.282, 25% Percentile = 12.357, 75% Percentile = 32.834; Gba-SNCA: Mean = 53.741, 25% Percentile = 32.233, 75% Percentile = 66.691). H Cortical layer specific expression of α-synuclein at 3 months of age, and I 12 months of age. J Cortical layer specific expression of pSer129 α-syn at 3 months of age, and K 12 months of age. n = 3-5, sex balanced. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistics. ‘*’ indicates p-value. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns not significant; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

In Gba-SNCA mice, where GCase1 deficiency coexists with a pre-existing α-synuclein pathology26, there is significantly increased cortical α-synuclein and pSer129α-syn levels, especially at 12 months of age when compared to SNCA tg (Fig. 2A–C). We also noted increased α-synuclein in the neuronal soma of Gba-SNCA mice as an independent measure of α-synuclein pathology (Fig. 2A, arrows, enlarged inserts). Interestingly, in CA1 hippocampus, the expression of α-synuclein and pSer129α-syn, and the somal increase of α-synuclein in Gba-SNCA mice were comparable to SNCA tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 2C–G). Thus, in contrast to the cortex, Gba mutation only nominally exacerbates pSer129α-syn pathology, mostly in synaptic layer of CA1 at 12 months (Supplementary Fig. 2G). This might be in part due to high expression of the human SNCA tg in the hippocampus26,29.

Next, we examined the intensity distribution of pSer129α-syn in cortical neurons as well as cortical layer specific α-synuclein and pSer129α-syn expression, at 3 and 12 months of age (Fig. 2A, F–I). Gba mice did not show pSer129α-syn pathology. Gba-SNCA mice had a higher intensity of pSer129α-syn pathology in cortical neurons at 3 months (median value of 20 vs 0 in WT and Gba, and 11 in SNCA tg mice), which further worsened at 12 months (Fig. 2F, G) (median value of 47 vs 1 in WT, 0.2 in Gba, and 20 in SNCA tg mice). As the percentage of neurons expressing pSer129α-syn in Gba-SNCA was comparable to SNCA tg mice (Fig. 2D), these data suggest that the burden of pSer129α-syn per neuron in Gba-SNCA mice was greater. We did not see cortical neuronal loss in any of the mice (Fig. 2A, E), indicating that the observed behavioral deficits are not due to gross neurodegeneration.

Layer-specific analysis of α-synuclein expression revealed that cortical layer 1, which is heavily innervated by neurites, showed higher expression of α-synuclein compared to other layers (Fig. 2H, I, 3 and 12 months). Conversely, cortical layers 5 and 6a, which predominantly consist of excitatory neurons, showed higher pathological pSer129α-syn expression in SNCA tg and Gba-SNCA mice (Fig. 2J, K, 3 and 12 months), which is more evident when pSer129α-syn expression was normalized to α-synuclein (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B, 3 and 12 months). Together, these results suggest that the Gba mutation did not independently cause α-synuclein pathology but worsened pre-existing α-synuclein pathology in the cortex of SNCA tg mice, preferentially in layers 5 and 6a. With our behavior experiments (Fig. 1), these observations suggest that the cognitive deficits in Gba mutants emerge independently of pSer129α-syn pathology.

Gba and SNCA driven cortical single nuclei gene expression changes

To understand cellular diversity and mechanisms for GBA-linked cognitive dysfunction, we performed single nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) on cortical tissue from mice of all four genotypes (n = 14; 3-4 mice/genotype). We chose to perform this analysis on 12-month-old mice, as Gba-SNCA mice show enhanced behavioral deficits and α-synuclein pathology, while lacking gross neurodegeneration in the cortex, allowing us to investigate disease-relevant mechanisms.

We dissected cortices and utilized our previous mouse brain nuclei isolation protocol30, followed by snRNA-seq on the 10X Chromium platform. We isolated 104,750 nuclei, that after cross-sample alignment and clustering exhibited a spatial UMAP grouping uncorrelated with individual samples or genotype (Fig. 3A–E and Supplementary Fig. 3A, B).

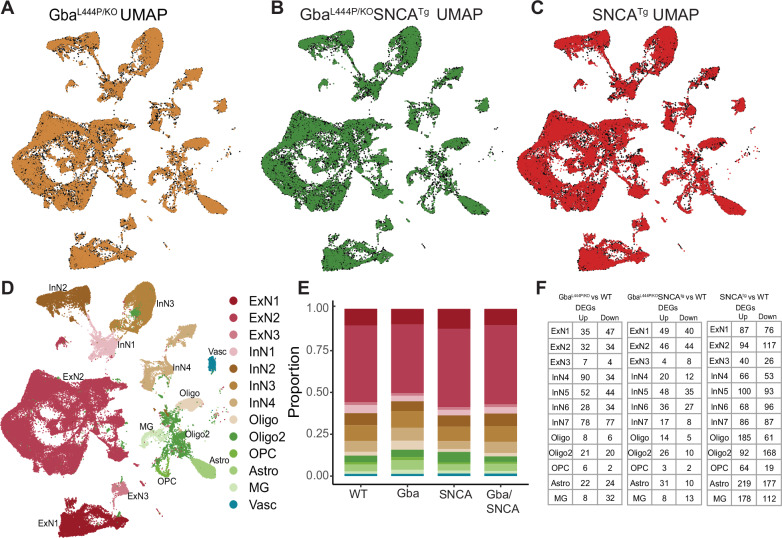

Fig. 3. Cell type distribution and differential gene expression in the cortex.

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) dimension reduction for A Gba (Amber), B Gba-SNCA (Green) and C SNCA tg (Red) overlayed over WT (Black) mouse cortical snRNAseq expression. D UMAP showing clusters of cortical cell types identified by expression signatures. In A–D, UMAP 1 is shown on the x-axis and UMAP 2 on the y-axis. E Proportions of the cell types in the cortices of wild type and transgenic mice. F The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) per cell type in Gba, Gba-SNCA, and SNCA mutant mice after correction for genome-wide comparisons and filtering out of genes with log2FC < 0.2. n = 4 for WT and Gba mice, and n = 3 for Gba-SNCA and SNCA tg mice.

The transcriptional signatures from 104,750 nuclei, segregated into 13 broad cortical cell type clusters (Fig. 3D, E), exhibiting specific expressions of established cell-type markers (Supplementary Fig. 2C). We identified three types of excitatory neurons (ExN: ExN1, ExN2, ExN3), four types of inhibitory neurons (InN: InN1, InN2, InN3, InN4), two types of oligodendrocytes (Oligo and Oligo2), oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC), astrocytes (Astro), and microglia (MG) (Fig. 3D). Vascular endothelial cells (Vasc) were also identified but were not further studied. The characteristic marker gene expression for each cell cluster is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3C–G. Expression in all ExNs is consistent with pyramidal neurons. In ExN1, differential expression was consistent with large layer 5 pyramidal neurons shown e.g. by Fezf2 expression. In the largest ExN subcluster, ExN2, differential expression was consistent with pyramidal neurons from several neocortical layers (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 3D–G). The InN subclusters collectively express several classical InN markers, such as Vip, Sst, Erbb4, while the subclusters InN1 and InN3 specifically contain layer 2/3 interneurons (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Typical marker signatures used for Oligo and Oligo2 (Mbp, Ptgds, Mal), suggests that Oligo2 also contains minor neuronal populations in addition to oligodendrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 3C). The OPC (Vcan, Epn2, Tnr), Astro (Aqp4, Prex2, Luzp2) and MG (Cd74, C1qa, Csf1r) markers are consistent with prior literature30,31. The relative proportions of major cell types were roughly similar between the four genotypes (Fig. 3E).

Next, we examined the expression of endogenous Gba, mouse Snca in WT brains and the expression of human transgenic SNCA (hSNCA) using Thy-1 in SNCA tg brains (Supplementary Fig. 3H–J). Snca is enriched in excitatory neuronal clusters, including ExN1, consistent with published literature (Supplementary Fig. 3H)32,33. This pattern was also true for hSNCA33–35, although hSNCA is also expressed in glial cell types in SNCA tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 3I). The high hSNCA expression in the predominantly layer 5-populated ExN1 cluster (Supplementary Fig. 3I) is consistent with the layer 5 specific increases of α-synuclein pathology demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2H and Supplementary Fig. 2A). In contrast, Gba is generally found at low levels in brain cells36–38 (Supplementary Fig. 3J).

Mutant Gba drives transcriptional downregulation of synaptic pathways in neurons

After correcting for genome-wide comparisons, we identified up- and down-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in all cell types in Gba, Gba-SNCA and SNCA tg mice cortices compared with WT (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Dataset 1–3). To gain insights into the cognitive deficits seen in Gba mice, we focused on DEGs in neuronal clusters, comparing Gba with WT (Supplementary Dataset 1). Strikingly, Gba mutant mice showed a general downregulation of many genes functioning at the synapse (Arc, Syp, Actb, Nrg1, Nlgn1, Grm7, Grip1, Ptprd, Il1rapl2, Gabra1, Cntn5, Lingo2, Erbb4, Nptn, Lrrtm4, Cntnap2, Lrfn5), suggestive of a synaptic dysregulation signature related to Gba. Ahi1, a gene important for cortical development and vesicle trafficking was upregulated in all neuronal classes in Gba mice.

To define the major pathways impacted, we performed unbiased gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis comparing Gba to WT (Fig. 4A, C). As shown by heatmaps depicting the top biological pathway changes, we found a consistent decrease in synaptic pathways in cortical ExNs of Gba mice driven by reduced expression of Syp, Actg1, Actb, Nlgn1, Grm8, Nrg1, Arc (Fig. 4A). ExN1 and ExN2 shared robust downregulation of genes involved in synaptic vesicle endocytosis (SVE), presynaptic endocytosis, vesicle-mediated transport in synapse, and postsynapse organization in Gba mice (Fig. 4A, highlighted, Supplementary Dataset 4). β-actin and γ-actin (Actb, Actg1) are both crucial for SVE by aiding formation of endocytic pits, and their downregulation therefore points to reduction in early steps of SVE. Additionally, in Gba mice, ExN1 and ExN2 showed downregulation of cellular pathways and genes involved in both pre- and postsynapse organization, and synaptic protein-containing complex localization (Fig. 4A, highlighted, Supplementary Dataset 4). In the smaller ExN3 cluster, DEGs were fewer and involved in lysosomal lumen acidification (Supplementary Dataset 4). In contrast, the significant upregulated pathways in ExN1 and ExN2 of Gba involve RNA splicing (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Dataset 4). Inhibitory neurons (InN1-4) in Gba mutant mice showed downregulation of multiple synapse-associated pathways, including genes involved in synapse organization, synapse membrane adhesion in InN1, synapse assembly in InN4, Wnt signaling in InN2, and axonogenesis (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Dataset 4). The upregulated pathways in InN1-4, similar to ExNs, are related to RNA splicing (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Dataset 4).

Fig. 4. Analysis of cellular pathways and synapse related gene expression in Gba and Gba-SNCA neurons shows similar deficits in synapse vesicle cycling.

Heatmap with the significantly down- and up-regulated gene ontology (GO) biological pathway alterations in 12 month old Gba- (A, C) and Gba-SNCA mice (B, D), for each neuronal cluster type, revealed by unbiased analysis of enrichment of genome-wide corrected DEGs. Analysis of significant DEGs that participate in synapse function, as annotated by SynGO, after correction for multiple comparisons and filtering out of genes with log2FC < 0.2 in excitatory (ExN1-3, E, G) and inhibitory (InN1-4, F, H) neurons. Cnet plots of differentially expressed synapse associated genes as annotated by SynGO, in I Gba-, and J Gba-SNCA mice cortices, after -correction for multiple comparisons. n = 4 for WT and Gba mice, and n = 3 for Gba-SNCA and SNCA tg mice.

Next, we compared DEGs in neuronal clusters in Gba-SNCA with WT (Supplementary Dataset 2). Consistent with our finding of a Gba-driven synapse effect, ExN clusters in Gba-SNCA mice show robust downregulation of synapse related genes (Supplementary Dataset 4). GO enrichment analysis comparing Gba-SNCA to WT revealed the top downregulated pathways in cortical ExN1 and ExN2 were SV cycle, vesicle-mediated transport in synapse, and SVE (driven by Actb, Actg1, Unc13a, Cacna1a, Calm1, Btbd9, Prkcg, Pacsin1 reductions Fig. 4B, highlighted). Although the individual DEGs between Gba and Gba-SNCA are not identical, the synaptic pathways being impacted are highly similar, suggestive of a common synaptic dysregulation signature related to Gba (Compare Fig. 4A with 4B). In Gba-SNCA InNs we see distinct pathways such as ubiquitin-protein transferase activator activity in InN1 and tRNA aminoacylation in InN2-4 being downregulated (Fig. 4B). The upregulated pathways in Gba-SNCA in ExNs are related to focal adhesion assembly and in InNs are diverse and include amyloid binding (Fig. 4D).

Next, we analyzed all neuronal DEGs through SynGO to define synaptic DEGs in Gba and Gba-SNCA mice. The SynGO analysis revealed more significant suppression of synaptic genes in ExN classes compared to InN classes in both genotypes (Fig. 4E–H). Salient synaptic genes downregulated in Gba ExN are Rab26, and Hspa8 (Fig. 4E). Rab26 regulates SVE and autophagy, while Hspa8 encodes Hsc70 which functions with auxilin to regulate both the initial and late-stages of clathrin mediated endocytosis, further indicating reduced SVE. Cnet plots revealed enrichment of converging and predominantly down-regulated synaptic genes and pathways in both Gba and Gba-SNCA mouse cortices (Fig. 4I, J), consistent with GO analyses (Compare Fig. 4A, B, with Fig. 4I, J).

To evaluate if the downregulation of synapse organization pathways leads to a decrease in excitatory synapse number, we performed electron microscopy on 12-month old cortex samples. Electron microscopy was chosen as it allows for accurate quantification of synapse numbers while avoiding problems of individual synaptic protein marker differences across genotypes. As seen in Fig. 5F, G, number of excitatory synapses in deep layers of cortex is indeed reduced in Gba mutant and Gba-SNCA mice compared to SNCA and WT mice.

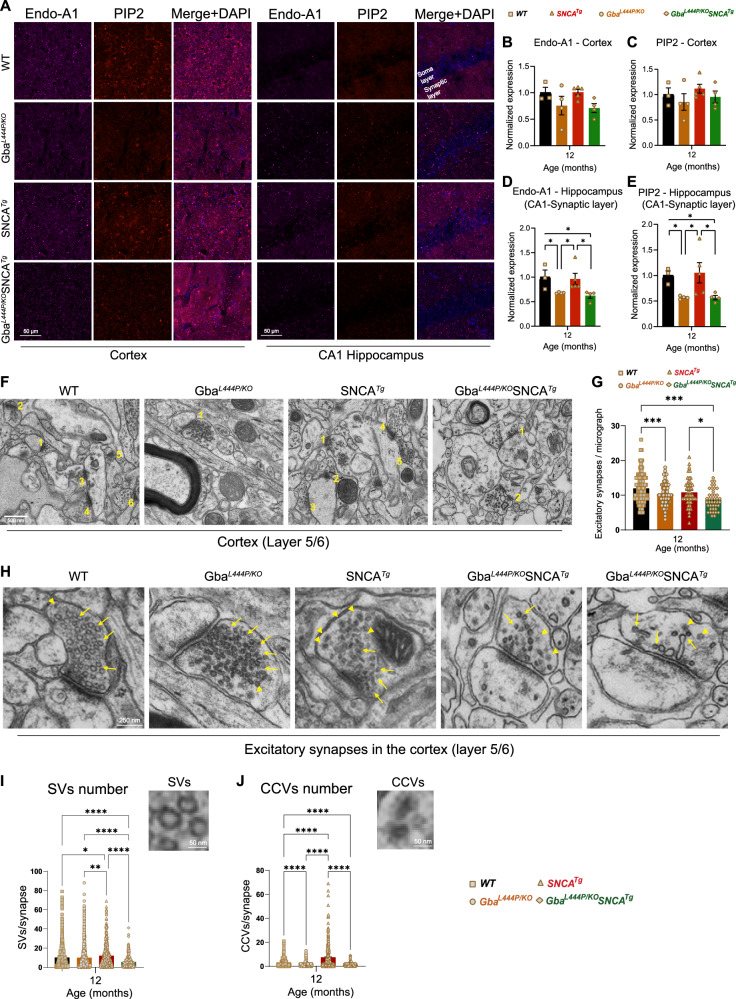

Fig. 5. Decreased expression of SVE markers and loss of synapses and SVs in Gba mutants.

A Representative images showing cortical and CA1 hippocampal expression of endophilin-A1 (Endo-A1) and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), two markers of synaptic vesicle endocytosis, in WT, Gba, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mice at 12 months of age. B Cortical Endo-A1 expression at 12 months, normalized to WT average. C Cortical PIP2 expression at 12 months, normalized to WT average. D Endo-A1 expression in the CA1 Hippocampal synaptic layer, normalized to WT average. E PIP2 expression in the CA1 hippocampal synaptic layer, normalized to WT average. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for (B–D). Scale = 50 µm. *p < 0.05. n = 4-5 brains/genotype. F Electron micrographs of cortical layer 5/6 number for excitatory synapses. G Quantitation of excitatory synapses in the cortical layer 5/6. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, Scale = 500 nm. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. H Electron micrographs of excitatory synapses in cortical layer 5/6 showing synaptic vesicles (SVs, arrows) and clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs, arrowheads) in WT, Gba mutant, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mice. Note SVs with variable shapes and sizes in Gba-SNCA synapse (v). Quantitation of SVs (I) and CCVs (J) in the excitatory synapses of the cortical layer 5/6. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, Scale = 250 nm, Scale for inset = 50 nm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistics. ‘*’ indicates p-value. ****p < 0.0001, N = 3 brains in WT and Gba mutant mice, and N = 2 brains in SNCA tg and Gba-SNCA mice, 23-25 micrographs, 150-300 synapses, per genotype.

To assess SVE changes at the protein level, we immunostained cortex and hippocampus sections for the SVE protein endophilin A1 (a risk allele for PD) and the endocytic lipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Conforming with the snRNA expression data, endophilin A1 and PIP2, showed a decreased trend in the cortex (Fig. 5A, Cortex, B, C). Interestingly, in the synaptic layer in CA1 of the hippocampus where endophilin A1 and PIP2 are enriched, we noted significantly reduced endophilin A1 and PIP2 expression in Gba and Gba-SNCA mice (Fig. 5A, CA1 hippocampus, D, E). Together, these observations corroborate our findings from snRNA-seq analysis of Gba-driven suppression of SVE genes and show these deficits are not limited to the cortex.

To determine whether these transcriptional and protein expression changes affect the SV cycle, we examined electron micrographs of excitatory synapses in the cortical layer 5/6 and quantified SVs and clathrin coated vesicles (CCVs), which serve as proxies for SV cycling and SVE (Fig. 5H–J). In the Gba mutant mice, the number of SVs was comparable to that in WT mice, however, a significant loss of CCVs was observed, potentially indicating a slowdown in clathrin-mediated SVE (Fig. 5H–J). In Gba-SNCA mice, there was a marked reduction in both SVs and CCVs (Fig. 5H–J), with several synapses showing SVs with variable shapes and sizes (Fig. 5H), indicating a severe disruption of SVE and SV recycling. Interestingly, the SNCA tg mice displayed a significant increase in CCVs (Fig. 5H–J), consistent with findings in other α-synuclein models39,40. Together, these findings reveal a distinct pattern of SVE disruption in Gba mutant mice, which is exacerbated in Gba-SNCA mice, with altered SV recycling potentially leading to cognitive dysfunction.

ExN1 cluster contains vulnerable layer 5 cortical neurons

As cortical layer 5 neurons exhibited the highest vulnerability in terms of α-synuclein pathology (Fig. 2A, H and Supplementary Fig. 2A–B), and transcriptional changes associated with SVE (Fig. 4A, B), we further investigated the ExN1 cluster which has high hSNCA transgene and Gba expression (Supplementary Fig. 3I, J). Upon subclustering, ExN1 was divided into six subclusters (Supplementary Fig. 4A–D), all of which contained cells expressing the layer 5 marker Fezf2 (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E). One subcluster, ExN1.1, was characterized by high expression of Arc (Supplementary Fig. 4D), which is downregulated in Gba mutant neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4F). Our analysis confirmed the greatest downregulation of synapse-associated genes in the ExN1 subclusters in both Gba and Gba-SNCA mice (Supplementary Fig. 4D, F–I). In contrast, non-synaptic DEGs were evenly up- and downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 4F, G). SV cycle pathways were consistently downregulated throughout ExN1, largely driven by the same genes identified in our non-targeted analysis (Fig. 4A, B). Additionally, Rab26, a key regulator of SVE and autophagy41, was downregulated in both Gba genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 4H, I). These findings suggest that layer 5 excitatory neurons are selectively vulnerable because of both high hSNCA and Gba expression and SV cycling deficits driven by Gba mutations. These mechanisms appear to act synergistically to exacerbate α-synuclein pathology in Gba-SNCA mice.

Modest glial transcriptional changes in Gba mutant and Gba-SNCA cortex

Compared to neuronal clusters, glial clusters in Gba and Gba-SNCA cortices exhibited fewer DEGs (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Dataset 1–3). In Gba cortex, MG showed altered gene expression patterns indicative of reduced synaptic remodeling. Notably, synapse pruning and regulation of SV clustering pathways were downregulated (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Dataset 4). Postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor diffusion trapping was upregulated (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Dataset 4). These changes reinforce synapse dysfunction as a central pathological mechanism in Gba mutant cortex. The down and upregulated pathways in astrocytes in Gba are related to cellular extravasation and morphology (Fig. 4A, C and Supplementary Dataset 4). There were fewer DEGs in OPCs and Oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A, C); therefore, clear pathway differences are harder to discern (Fig. 4A, C).

In Gba-SNCA, MG exhibit decreased endoplasmic reticulum stress response, while SNARE binding and aspects of phosphatidylinositol binding were upregulated (Fig. 4B, D and Supplementary Dataset 4). Gba-SNCA Astro exhibit decreased tRNA aminocylation and increased amyloid-beta binding (Fig. 4B, D). In Gba-SNCA OPCs, phosphatidylinositol binding was downregulated, while Oligodendrocytes showed modest pathway changes (Fig. 4B, D). Overall, in Gba mice, all glial cell types have muted responses, while Gba-SNCA mice had slight astrocytic activation. To confirm our analysis, we immunostained with the microglial marker Iba1, CD68 for activated microglia, and GFAP for astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 5). We did not observe any significant increase in Iba1 or CD68+ve microglial number, suggesting negligible microglial activation in Gba and Gba-SNCA cortex. We observed a trend towards increased GFAP levels in Gba-SNCA mice compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 5A–D). Together, these data suggest that glial responses are modest, consistent with snRNAseq data.

Cortical transcriptional changes indicate broad synapse dysregulation in SNCA cortex

SNCA tg mice showed the greatest number of DEGs compared to WT relative to Gba and Gba-SNCA mice (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Dataset 3). The neuronal clusters showed broad alterations of synapse related gene expression. In contrast to the Gba mouse lines, both up and down-regulated DEGs are involved in synapse assembly, regulation of synapse structure or activity, and postsynapse organization (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B and Supplementary Dataset 3). SynGO analysis of these DEGs revealed regulation of synapse structure and function as the main pathway impacted in SNCA tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 6C–E), particularly in glutaminergic synapses (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). Several of the synaptic genes downregulated in SNCA ExN, particularly in ExN1, take part in synaptic membrane adhesion (Ptprd, Lrfn5, Lrrc4c, Nlgn1, Nrg1). In contrast to downregulation in Gba mouse lines, SNCA mice have upregulation of genes that participate in the postsynaptic density (Dgkz. Hspa8, Dbn1) and modulate phosphatidylinositol activity (Dgkz, Dgkb) including PIP5KIA which synthesizes PIP2. The latter upregulation can influence SV cycling, possibly as a compensatory effect. As excitatory synapse number was not changed significantly in cortical regions of SNCA tg mice (Fig. 5F, G) compared to WT, these transcriptional changes only result in functional deficits. Consistent with the observed cortical α-synuclein pathology at this age (Fig. 2A, D), unfolded protein handling was upregulated, as were pathways involved in protein folding and refolding specifically in ExN1 and ExN2 clusters (Supplementary Fig. 6B and Supplementary Dataset 3). Additionally, regulation of protein ubiquitination was upregulated in all ExNs (Supplementary Fig. 6B and Supplementary Dataset 3). OPCs and oligodendrocytes show changes related to oligodendrocyte differentiation. MG showed down-regulation in immune receptor binding and up-regulation in cation channel activity (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B and Supplementary Dataset 3). In Astros, cell junction assembly was decreased, and ion channel activity was increased (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). However, we did not observe significant microgliosis or astrogliosis in SNCA tg mice cortices by immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 5). Despite SNCA transcriptional changes, Gba signatures are predominant in Gba-SNCA cortices.

Discussion

Surveys of PD and DLB patients and their caregivers highlight that maintaining cognitive abilities is a major unmet need42. The GBA gene is an ideal choice to investigate this non-motor symptom, because it is the most common risk gene for PD and DLB1–8, and GBA mutations are linked to cognitive deficits in both diseases8,18. Traditionally, GBA-associated cognitive deficits have been attributed to cortical Lewy pathology, particularly the aggregation of α-synuclein in cortical regions. However, our study challenges this long-held view by providing compelling evidence that cognitive dysfunction can occur independently of cortical α-synuclein pathology—marking a significant conceptual shift in our understanding of GBA-linked PD and DLB. This conclusion stems from a comprehensive, longitudinal behavioral and pathological analyses using a Gba-SNCA mouse model, alongside Gba mutant, SNCA tg, and WT controls. Mechanistic insights were further revealed through snRNA-seq of the cerebral cortex of all four genotypes, which uncovered the synaptic dysfunction in Gba mutations—most notably deficits in SVE. This dataset, a large-scale transcriptomic resource focused on Gba-mediated changes in brain, is publicly available via the NCBI (GEO, accession number: GSE283187) and offers a valuable platform for further exploration. Collectively, our findings not only redefine the role of cortical α-synuclein pathology in cognitive impairment of PD and DLB but also provide mechanistic insights with potential for therapeutic developments focused on synaptic mechanisms.

Cognitive dysfunction has been noted in several existing mice models of PD designed to study motor deficits, including those focused on α-synuclein pathology43–46. These models involve overexpression of hSNCA mutations or the use of pre-formed fibrils to induce α-synuclein aggregation47 and have been instrumental in elucidating the mechanisms of α-synuclein pathology and its impact on neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. However, they do not fully replicate the complex genetic and pathological features of human PD and DLB, importantly, the contribution of GBA. Additionally, most biallelic Gba mouse models are hampered by early lethality, precluding age-related studies, and hence investigated as heterozygotes47–49. Here, we build on our previous analyses of long-lived biallelic Gba mutant mice and Gba-SNCA26 and show that Gba-SNCA mice are an excellent model of GBA-linked PD and DLB. Gba-SNCA mice offer significant advancements as they exhibit worsened motor deficits compared to SNCA tg in an age-dependent manner as well as clear cognitive deficits, closely mirroring the human condition. This is further evidenced by exacerbation of cortical α-synuclein pathology in Gba-SNCA mice. Significantly, by comparing Gba, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mice, we were able to demonstrate that the Gba mutation alone can drive cognitive dysfunction. These data are congruent with recent studies using heterozygous L444P Gba mutant mice47,49. Notably, Gba-SNCA mice exhibited enhanced motor deficits, but cognitive deficits were on par with Gba mice, matching the similar synaptic pathway deficits in their neuronal populations as assessed by snRNAseq. In sum, Gba-SNCA mice capture the complexities of GBA-linked PD and DLB and serve as a good mouse model for these synucleinopathies.

It is important to note that most patients with GBA-associated PD and DLB carry only one allele with a GBA variant. However, our choice of the biallelic Gba mutant mouse model is motivated by the fact that biallelic GBA mutations gives an even higher risk of PD and DLB3,14,50. Foundational evidence for the association of GBA with PD arose from clinical observations of PD prevalence in patients with biallelic GBA mutations3,50. Individuals with biallelic mutations, i.e. GD patients, have a significantly higher risk of developing PD (4.7% by age 60) compared to heterozygous carriers (1.5%)1,14. Moreover, biallelic GBA mutations, particularly severe variants like L444P, are associated with an earlier age at onset and a greater burden of cognitive dysfunction14,51,52. While patients with GBA-associated PD do not develop severe cognitive deficits prior to motor symptoms, in GBA-associated DLB, cognitive impairment often precedes or coincides with motor manifestations4–6, as observed in our mouse models. This model thus provides a valuable platform to investigate shared and distinct pathogenic mechanisms between PD and DLB, including the relationship between GBA mutations and synaptic deficits.

A striking finding is that cognitive dysfunction occurs independent of or precede α-synuclein pathology in Gba mutants. pSer129α-syn is the gold standard to define Lewy bodies in both PD and DLB53–61. Yet, we did not detect any pSer129α-syn in Gba mutant brain nor did we observe increased α-synuclein levels in the soma, an independent measure of pathology62. This was most evident in the hippocampus, where the synaptic and cell body layers are demarcated. While α-synuclein pathology in cortical areas does lead to cognitive dysfunction in mice overexpressing mutant α-synuclein or those injected with PFFs46, our study specifically challenges the necessity of α-synuclein pathology in the development of cognitive deficits in GBA mutations. Although we observed modest (not-significant) increases in physiological α-synuclein within the synaptic layers of the cortex (18.2% at 3 months, 21.4% at 12 months, vs. WT in layer 1)—findings further supported by another recent study focused on the hippocampus49—this likely represents a compensatory effect in the absence of true phospho-α-synuclein pathology. Clinical support for this comes from children with neuronopathic forms of Gaucher disease, who show cognitive deficits but do not have neocortical α-synuclein pathology63,64. It would be interesting to explore whether aging Gba mice could initiate α-synucleinopathy or if other pathological forms of α-synuclein are involved. Moreover, our findings reveal a more pronounced excitatory synapse loss in cortical layer 5 of Gba mutant mice compared to SNCA transgenic mice, despite more synaptic transcriptomic alterations in the latter. This suggests that GBA mutations can drive synaptic dysfunction through mechanisms independent of α-synuclein—and potentially in a more severe manner. Such insights may help explain the higher incidence of cognitive impairment in PD patients with GBA mutations compared to sporadic cases.

In contrast to cognitive deficits, motor deficits are strongly related to α-synuclein pathology in Gba-SNCA mice. Notably, we observed significant α-synuclein pathology in cortical layers 5, similar to that seen in other PD mice models and human PD and DLB patients33,65. Our snRNA-seq data suggest that layer 5 ExNs are also vulnerable to Gba mediated synaptic dysfunction, which could contribute to an increased accumulation of α-synuclein pathology in cortical layer 5, and in turn, the severity of the motor deficits. Thus, Gba-SNCA mice also highlight specific cortical neuronal vulnerabilities, allowing for further investigations into cortical mechanisms of PD and DLB.

Our snRNAseq analysis showed clear evidence of specific synaptic changes. Many synaptic genes that function in SV cycle, SVE, synapse organization, synapse membrane adhesion, and synapse assembly were downregulated in neuronal clusters in the cortex of Gba as well as in Gba-SNCA mice, suggesting common synaptic dysfunction mechanisms linked to Gba. Because Gba mutant mice do not show α-synuclein pathology, this implies that synaptic dysfunction directly contributes to the observed cognitive deficits, rather than a consequence of disease pathology or neurodegeneration. In support of this tenant, we observed excitatory neuronal synapse loss in the cortex of Gba mutant and Gba-SNCA mice. In other dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease, synapse loss correlates tightly with cognitive decline66. Our findings suggest that this is likely true for GBA-linked PD and DLB, in line with available clinical studies67–69.

SVE was the major pathway downregulated in neurons in both Gba mutant and Gba-SNCA mice, supported by our immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy experiments. Three key genes driving this pathway are Hspa8, Actb, and Arc. Hspa8 (encoding Hsc70) contributes to synapse vesicle uncoating and functions with Dnajc6/PARK19, a familial PD gene70,71. Actb regulates SVE and the cytoskeleton. Arc is an activity regulated gene that regulates transcription of many synaptic and SVE genes72. Interestingly, both clinical and experimental data link SVE deficits to cognitive deficits. The levels of dynamin1, the endocytic GTPase, correlate with Lewy body dementia73. Patients with mutations in DNAJC6/PARK19 and Synj1/PARK20 which encode two key SVE proteins--auxilin and synaptojanin1—have cognitive deficits. Endocytic mutant mice show deficits in NOR and fear conditioning74,75, supporting the tenet that SVE deficits lead to cognitive dysfunction. We suggest that Arc could serve as an upstream regulator of the synaptic transcriptional changes seen in Gba and Gba-SNCA cortices.

Another contributor to the Gba-driven alteration of SV cycling is plasma membrane lipid composition changes. Importantly, we found CCVs to be reduced in synapses in deep cortical layers in Gba mutant neurons together with transcriptomic signatures of reduced SV generation and recycling. Our data also indicate that this reduction possibly occurs due to lipid composition changes caused by GCase deficiency. Emerging evidence indicates altered sphingolipid composition, such as in Gba mutants, may interfere with phosphoinositide biology at membranes76,77. This Gba-driven dysfunction could cause reduced SVE by disrupting early stages of SVE. In contrast, in SNCA tg CCVs were increased in our EM analysis. The transcriptomic data indicate that this may be related to inefficient uncoating of CCVs during later phases of SV recycling, making them accumulate. This would represent two related but different mechanisms of SV recycling dysfunction in Gba and SNCA mutations. Future research should address the topic of co-regulated lipids, and SVE in Gba mutants.

Regarding limitations of the study, while the Gba-SNCA mouse model effectively replicates characteristics of GBA-linked PD and DLB, its application in large-scale preclinical studies may be limited by the resource-intensive nature of the model, which requires multiple genetic lines, complex breeding strategies, and extensive genotyping to obtain viable Gba-SNCA double mutants. Our snRNAseq analysis highlights the critical role of synaptic dysfunction in GBA-linked cognitive decline, occurring independent of α-synuclein pathology. While the DEGs were highly significant and consistently changed, many genes in the Gba mutants did not exhibit large fold changes versus controls. This was expected, as studied genotypes model age-related risk, but individual DEGs will benefit from being validated. Furthermore, while transcriptional analysis and histology confirmed significant disruptions in SVE and synapse assembly in cortical excitatory neurons of both Gba and Gba-SNCA mice, the upstream regulators of these changes remain to be identified. Our comprehensive transcriptomic dataset provides a rich resource for further exploration, and we encourage the scientific community to leverage this data to elucidate GBA-linked disease mechanisms.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were executed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the approval of the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol number 11117). Mice were maintained in temperature and humidity controlled room on a 12-hour light-dark cycle with access to standard chow ad libitum. Gba mutant mice have been previously described in Mistry et al. (2010)78 and Taguchi et al. (2017)26. These mice have a copy of the Gba L444P mutant allele and a Gba KO allele, with Gba expression rescued in skin to prevent early lethality. SNCA tg mice overexpress the human α-synuclein A30P transgene (heterozygous), and have also been previously described29. Gba mutant mice were crossed to SNCA tg to obtain Gba-SNCA double mutant mice. Age and sex matched WT mice were used controls.

Behavior evaluation

WT, Gba, SNCA tg, and Gba-SNCA mice were examined for motor behavior longitudinally at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of age as described previously (n = 9-12 mice/genotype, sex-matched)28. The balance beam test assesses the ability to walk straight on a narrow beam from a brightly lit end towards a dark and safe box. Number of times a mouse could perform this behavior in a minute and the average time taken for each run were evaluated. The grip strength of all the limbs and the forelimbs was assessed by measuring the maximum force (g) exerted by the mouse in grasping specially designed pull bar assembly in tension mode, attached to a grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments, Ohio, USA). Mice, when picked up by the base of the tail and lowered to a surface, extend their limbs reflexively in anticipation of contact. Mice with certain neurological conditions display hind limb clasping instead of extension. Mice were tested on this maneuver for 30 secs and the hindlimb, forelimb, and trunk clasps were scored (0: no clasp; 1: one hind limb clasp; 2: both the hind limbs clasp; 3: Both the hind limbs clasping with at least one forelimb clasp; 4; Both the hind limbs clasp with trunk clasping). For evaluation of overall locomotory capabilities, mice were allowed to explore an open field arena for 5 minutes, which was videotaped to assess the distance travelled using Noldus Ethovision CT software.

To evaluate cognition, we employed fear conditioning and novel object recognition (NOR) tests. To avoid learning-induced confounding factors, we performed these tests on two separate sets of mice at 3 and 12 months. For fear conditioning test, we initially habituated mice in standard operant boxes for 2 minutes, followed by exposure to a 30-second neutral stimulus (a 80 dB tone), which ended with 2 seconds of an aversive stimulus (a 0.1 to 1.0 mA electric shock). This pairing associates the neutral stimulus with fear, leading the mice to exhibit fear responses, such as freezing, when exposed to the tone alone. We tested for freezing 24 hours later on the testing day. Cognitively normal mice will form a conditioned fear response, exhibiting increased freezing behavior on the testing day compared to the training day after exposure to the tone alone, indicating their ability to associate tone with the electric shock they received on the training day. We measure this conditioned fear response as the number of freeze counts after starting the tone for a total of 3 minutes. The NOR test was used to assess the recognition memory. First, mice were acclimatized to the novel object arena without any objects in it. After 24 hours, familiarization session was performed where mice were presented with two similar objects for 8 minutes. After 18-20 hours, one of the two objects was replaced by a novel object and mice were allowed to explore for 8 minutes. Mice being exploratory animals, spend more time with novel object when their cognition is normal, which we used as a measure of NOR test.

Immunohistochemistry

Equal number of male and female mice at 3 and 12 months of age (n = 3-6/genotype) were used for immunohistochemistry. Mice were anaesthetized using isoflurane inhalation and perfused intracardially with chilled 0.9% heparinized saline followed by chilled 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). The brains were post-fixed in the same buffer for ~48 hours and cryoprotected in increasing grades of buffered sucrose (15 and 30%, prepared in 0.1 M PB), at 4 °C, and stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Sagittal brain sectioning (30 μm thick) was performed using a cryostat (Leica CM1850, Germany), and the sections were collected on gelatinized slides, and stored at -20 °C until further use. For immunofluorescence staining, sections were incubated in 0.5% triton-X 100 (Tx) (15 mins), followed by incubation in 0.3 M glycine (20 mins). Blocking was performed using 3% goat serum (90 mins), followed by overnight incubation (4 °C) in the primary antibodies. Following day, sections were incubated in Alexa-conjugated secondaries for 3-4 hours, followed by coverslip mounting using an antifade mounting medium with (H-1000, Vectashield) or without (H-1200, Vectashield) DAPI. Coverslips were sealed using nail polish. 1X PBS with 0.1 % Tx was used as both washing and dilution buffer. Below is the list of antibodies used and their dilutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of antibodies used and their dilutions

| Antibody | Dilution | Manufacturer, RRID |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Anti-α-Synuclein | 1:500 | BD Biosciences (610786), AB_398107 |

| Guinea Pig Anti-NeuN | 1:500 | Sigma-Aldrich (ABN90P), AB_2341095 |

| Rabbit Anti-α-synuclein (phospho S129) | 1:800 | Abcam (ab51253), AB_869973 |

| Rabbit Anti-Iba1 | 1:300 | Wako Chemicals (019-19741), AB_839504 |

| Guinea Pig Anti-GFAP | 1:400 | Synaptic Systems (173004), AB_1064116 |

| Mouse Anti-CD68 | 1:400 | Invitrogen (MA1-80557), AB_929627 |

| Rabbit Anti-Endophilin 1 | 1:200 | Synaptic Systems (159002), AB_887757 |

| Mouse Anti-PIP2 | 1:200 | Invitrogen (MA3-500), AB_568690 |

Fluorescence slide scanner, confocal microscopy, and image analysis

Fluorescent images were acquired using a fluorescence slide scanner (VS200, Olympus) or confocal microscope (LSM 800, Zeiss) with a 40X objective using appropriate Z-depth. Images were then analyzed using FIJI software from National Institute of Health (NIH), blinded for genotype. Whole cortex was demarcated as per Paxinos and Franklin, 2008. After performing sum intensity projection, the expression intensity was measured on an 8-bit image as the mean gray value on a scale of 0–255, where ‘0’ refers to minimum fluorescence and ‘255’ refers to maximum fluorescence. Normalization was performed by dividing all expression values in each group by the average value of the WT group, allowing for direct comparison between groups while accounting for variability in baseline expression levels. For counting NeuN+ neurons, images were thresholded using the ‘otsu’ algorithm and the cells larger than 25 mm2 were counted using the ‘analyze particles” function28. A similar method was used to count Iba1+ve microglial cells, and CD68 +ve cells. GFAP+ astroglial cells were counted manually using the ‘cell counter’ function. Regions of interest (ROIs) obtained for individual NeuN+ were overlayed on pSer129α-syn staining to obtain numbers of neurons that were positive for pSer129α-syn. To analyze the cortical layer-specific expression of α-synuclein and pSer129α-syn, we initially determined the proportions of cortical layers (1 to 6b) in sagittal brain slice images obtained from the Allen Brain Atlas (https://mouse.brain-map.org/). This involved drawing perpendicular lines across cortical layers using FIJI software. Proportions were calculated across three different sample areas of the entire cortex. Intensity profiles for α-synuclein and pSer129α-syn expression across cortical layers were then generated by drawing perpendicular lines and utilizing the “RGB Profile Plot” function on FIJI for the corresponding sample areas. The resulting expression values, scaled from 0 to 255, were subsequently assigned to the proportions of layers 1 to 6b obtained from the Allen Brain Atlas.

Western blotting

Fresh brains were dissected from the mice after euthanasia by isoflurane inhalation and cervical dislocation and quickly homogenized to prepare protein samples. These samples were separated by electrophoresis on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels to resolve proteins by molecular weight. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature using 5% goat serum dissolved in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20). Blocked membranes were subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in the same blocking buffer. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-α-synuclein (BD Biosciences-610786, 1:1000 dilution), rabbit anti-pSer129-α-synuclein (Abcam- ab51253, 1:1000 dilution), and mouse anti-β-actin (GeneTex-GTX629630, 1:1000 dilution, used as a loading control). After incubation, membranes were thoroughly washed in TBST and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to infrared dyes (LI-COR IRDye Goat secondary antibodies), diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer. Membranes were then washed using TBST and imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey imaging system. Densitometry values were measured using ImageJ, and the signal intensities of α-synuclein and pSer129-α-synuclein were normalized to β-actin intensity, which served as a loading control.

Electron microscopy

Following isoflurane inhalation anesthesia, brains of 12-month-old mice (n = 2-3 per genotype) were fixed via intracardial perfusion with a solution of 2% PFA and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PB. This was followed by an overnight immersion in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% PFA28. The cortical layers 5 and 6 were then dissected and processed at the Yale Center for Cellular and Molecular Imaging’s Electron Microscopy Facility. Electron microscopy imaging was conducted using an FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTwin Electron Microscope, and the resulting micrographs were analyzed for excitatory asymmetric synapses, their synaptic vesicles and clathrin coated vesicles using FIJI software, with the analysis performed blind to genotype.

Nuclei isolation from cerebral cortex

Fresh cortical tissue were dissected from left hemisphere of 12 month old WT, Gba, SNCA tg and Gba-SNCA mice after euthanasia by isoflurane inhalation and cervical dislocation. Single nuclei were isolated as previously described with modifications30. All procedures were carried out on ice or at 4 oC. Briefly, fresh cortical tissue was homogenized in 8.4 ml of ice-cold nuclei homogenization buffer [2 M sucrose, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 25 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and ribonuclease (RNase) inhibitors freshly added (40U/ml)] using a Wheaton Dounce tissue grinder (10 strokes with the loose pestle and 10 strokes with the tight pestle). The homogenate was carefully transferred into a 15 ml ultracentrifuge tube on top of 5.6 ml of fresh nuclei homogenization buffer cushion and centrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 60 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of nuclei resuspension buffer [15 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, and RNase inhibitors freshly added (40U/ml)] and counted on a hemocytometer with Trypan Blue staining. The nuclei were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C with a swing bucket adaptor. They were subsequently resuspended at a concentration of 700 to 1200 nuclei/μl in the nuclei resuspension buffer for the next step of 10x Genomics Chromium loading and sequencing.

Droplet-based single nucleus RNA sequencing and data alignment

After quality control, we recovered a total of 104,750 nuclei, including 31,906 nuclei from WT, 28,568 from Gba mutant, 26,579 from SNCA tg, and 17,697 from Gba-SNCA cortices. The mean reads per nuclei was 34,312 and the median number of identified genes per nuclei was 2410 in all samples. The snRNA-seq libraries were prepared by the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kit v3.1 chemistry according to the manufacturer’s instructions (10x Genomics). The generated snRNA-seq libraries were sequenced using Illumina NovaSeq6000 S4 at a sequencing depth of 300 million reads per sample. For snRNA-seq of brain tissues, a custom pre-mRNA genome reference was generated with mouse genome reference (available from 10x Genomics) that included pre-mRNA sequences, and snRNA-seq data were aligned to this pre-mRNA reference to map both unspliced pre-mRNA and mature mRNA using CellRanger version 3.1.0. The raw data are available on NCBI GEO GSE283187.

Single-cell quality control, clustering, and cell type annotation

After quality control filtering by eliminating nuclei with less than 200 genes or more than 5% mitochondrial gene expression (poor quality nuclei) or more than 6,000 genes (potential doublets) per nucleus, we profiled 104,750 brain nuclei. Seurat (version 4.2.0) single cell analysis R package was used for processing the snRNA-seq data. The top 2000 most variable genes across all nuclei in each sample were identified, followed by the integration and expression scaling of all samples and dimensionality reduction using principal components analysis (PCA). Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) was then applied to visualize all cell clusters, and the classification and annotation of distinct cell types were based on known marker genes of each major brain cell type and the entire single nucleus gene expression matrix were investigated but were not used in downstream analyses.

Differential expression (DE) analysis

Differential expression analysis for snRNA-seq data was performed using MAST79 (i.e. the default generalized linear model test) in the function FindMarkers of the Seurat package (4.1.0) in R to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), adjusted for sex, batch, and read depth. MAST is a generalized linear model that treats cellular detection rate as a covariate. For all cells, the threshold for DEGs was set as the expression log2 fold change of Mutant/WT mice being greater than 0.2 and significantly changed (p < 0.05) after Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) -correction for multiple (genome-wide) comparisons, using default parameters, and adjusted for confounders. Adjustment for confounders was made for differences in sex, batch and read depth with MAST79 before inclusion of DEGs in downstream analyses.

Gene ontology (GO) pathway and targeted gene expression analysis

Gene-set and protein enrichment analysis was performed using the function enrichGO from the R package clusterProfiler in Bioconductor (3.14)80, with the DEGs that were significant after correction (see above) as input. Cnet plots were produced using the same package. The top three GO terms from biological process (BP) based on the lowest p-value were identified and plotted in a heatmap, without selection. Molecular function (MF) subontologies were shown instead of BP in a few cases ( < 8) where BP contained duplicates or triplicates of the same pathway, for illustrative purposes, with the same DEGs and ranking used for BP and MF subontologies. The background genes were set to be all the protein-coding genes for the mouse reference genome. Default values were used for all parameters. In GO pathway analysis DEGs were entered only if significant after genome-wide BH correction (for the total number of expressed genes), using Seurat default settings. In targeted analyses of genes of interest – i.e., genes known to function in the synapse as defined by the SynGO consortium (https://syngoportal.org), correction for multiple comparisons was done for the number of investigated genes. For the latter analysis, 1203 synaptic genes were found expressed in the dataset.

Statistics

For motor behavioral studies, two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used. For cognitive behavior assays, Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction was used for Fear Conditioning and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for Novel Object Recognition. For histochemistry experiments, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests was used.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Institute of Health (NIH-NINDS, 1RF1NS110354-01) R01 grant, Bell Research Initiative for Patients with Parkinson’s Disease, and Parkinson’s Foundation Research Center of Excellence (PF-RCE-1946) grant to S.S.C., US Department of Defense Early Investigator Research award (W81XWH-19-1-0264) to D.J.V., and in part by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF-020160) to S.S.C. and D.J.V. We thank the Yale Neuroscience Rodent Behavior Analysis facility and Yale Neuroscience Imaging Core supported by The Kavli Institute of Neuroscience for usage of their microscopes. We thank Betül Yücel for contributing to genotyping of SNCA tg mice.

Author contributions

D.J.V., D.B., and S.S.C. conceptualized the study. D.J.V. conducted behavioral experiments and analyzed the data, prepared samples for histology and Western blotting, and performed immunohistochemistry, imaging, and image analyses. D.B. prepared samples for snRNA-seq and analyzed the snRNA-seq data. R.C. analyzed behavioral data and performed immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, imaging, and image analyses. J.R. set up founder breeding colonies and conducted genotyping for Gba L444P/KO and Gba-SNCA mice. J.P. assisted with snRNA-seq data analysis. P.M. contributed to the initial conceptualization of the study and provided founder colonies of Gba L444P/KO mice. D.J.V., D.B., and S.S.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and contributed to the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Raw data for snRNA-seq analysis are available on NCBI repository with the accession number GEO GSE283187. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: D. J. Vidyadhara, David Bäckström.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-63444-9.

References

- 1.Bultron, G. et al. The risk of Parkinson’s disease in type 1 Gaucher disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis.33, 167–173 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidransky, E. et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med.361, 1651–1661 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aharon-Peretz, J., Rosenbaum, H. & Gershoni-Baruch, R. Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene and Parkinson’s disease in Ashkenazi Jews. N. Engl. J. Med.351, 1972–1977 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiner, T. et al. High frequency of GBA gene mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies among Ashkenazi Jews. JAMA Neurol.73, 1448–1453 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuang, D. et al. GBA mutations increase risk for Lewy body disease with and without Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology79, 1944–1950 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siebert, M., Sidransky, E. & Westbroek, W. Glucocerebrosidase is shaking up the synucleinopathies. Brain137, 1304–1322 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aarsland, D. et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.7, 47 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu, G. et al. Specifically neuropathic Gaucher’s mutations accelerate cognitive decline in Parkinson’s. Ann. Neurol.80, 674–685 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mata, I. F. et al. GBA Variants are associated with a distinct pattern of cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.31, 95–102 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji, S. et al. A mutation in the human glucocerebrosidase gene in neuronopathic Gaucher’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med.316, 570–575 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji, S. et al. Genetic heterogeneity in type 1 Gaucher disease: multiple genotypes in Ashkenazic and non-Ashkenazic individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA85, 2349–2352 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charrow, J. et al. The Gaucher registry: demographics and disease characteristics of 1698 patients with Gaucher disease. Arch. Intern. Med.160, 2835–2843 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabowski, G. A., Petsko, G. A. & Kolodny, E. H. Gaucher disease. in The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (eds Valle, D. L., Antonarakis, S., Ballabio, A., Beaudet, A. L. & Mitchell, G. A) (McGraw-Hill Education, 2019).

- 14.Alcalay, R. N. et al. Comparison of Parkinson risk in Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Gaucher disease and GBA heterozygotes. JAMA Neurol.71, 752–757 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brockmann, K. et al. GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease: reduced survival and more rapid progression in a prospective longitudinal study. Mov. Disord.30, 407–411 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winder-Rhodes, S. E. et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations influence the natural history of Parkinson’s disease in a community-based incident cohort. Brain136, 392–399 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeda, T. et al. Impact of glucocerebrosidase mutations on motor and nonmotor complications in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging36, 3306–3313 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szwedo, A. A. et al. GBA and APOE impact cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease: a 10-year population-based study. Mov. Disord.37, 1016–1027 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alcalay, R. N. et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson’s disease with and without GBA mutations. Brain138, 2648–2658 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha, E. M. et al. Progressive decline of glucocerebrosidase in aging and Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.2, 433–438 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hallett, P. J. et al. Glycosphingolipid levels and glucocerebrosidase activity are altered in normal aging of the mouse brain. Neurobiol. Aging67, 189–200 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson, G. S. & Leverenz, J. B. Profile of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol.20, 640–645 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gegg, M. E. et al. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in substantia nigra of parkinson disease brains. Ann. Neurol.72, 455–463 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zunke, F. et al. Reversible conformational conversion of α-synuclein into toxic assemblies by glucosylceramide. Neuron97, 92–107.e110 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzulli, J. R. et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell146, 37–52 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taguchi, Y. V. et al. Glucosylsphingosine promotes α-synuclein pathology in mutant GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci.37, 9617–9631 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straniero, L. et al. The SPID-GBA study: sex distribution, penetrance, incidence, and dementia in GBA-PD. Neurol. Genet.6, e523 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidyadhara, D. J. et al. Dopamine transporter and synaptic vesicle sorting defects underlie auxilin-associated Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep.42, 112231 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandra, S., Gallardo, G., Fernández-Chacón, R., Schlüter, O. M. & Südhof, T. C. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell123, 383–396 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, N. et al. Decoding transcriptomic signatures of cysteine string protein alpha-mediated synapse maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA121, e2320064121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, B. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of Parkinson’s disease Brains. bioRxiv10.1101/2022.02.14.480397 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Shwab, E. K. et al. Single-nucleus multi-omics of Parkinson’s disease reveals a glutamatergic neuronal subtype susceptible to gene dysregulation via alteration of transcriptional networks. Acta Neuropathol. Commun.12, 111 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goralski, T. M. et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals molecular dysfunction associated with cortical Lewy pathology. Nat. Commun.15, 2642 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geertsma, H. M. et al. A topographical atlas of α-synuclein dosage and cell type-specific expression in adult mouse brain and peripheral organs. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.10, 65 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taguchi, K., Watanabe, Y., Tsujimura, A. & Tanaka, M. Brain region-dependent differential expression of alpha-synuclein. J. Comp. Neurol.524, 1236–1258 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dopeso-Reyes, I. G. et al. Glucocerebrosidase expression patterns in the non-human primate brain. Brain Struct. Funct.223, 343–355 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrera Moro Chao, D. et al. Visualization of active glucocerebrosidase in rodent brain with high spatial resolution following in situ labeling with fluorescent activity based probes. PLoS ONE10, e0138107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boddupalli, C. S. et al. Neuroinflammation in neuronopathic Gaucher disease: role of microglia and NK cells, biomarkers, and response to substrate reduction therapy. Elife11, e79830 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Banks, S. M. L. et al. Hsc70 ameliorates the vesicle recycling defects caused by excess α-synuclein at synapses. eNeuro7, ENEURO.0448-19.2020 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Xu, J. et al. α-Synuclein mutation inhibits endocytosis at mammalian central nerve terminals. J. Neurosci.36, 4408–4414 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binotti, B. et al. The GTPase Rab26 links synaptic vesicles to the autophagy pathway. Elife4, e05597 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman, J. G. et al. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a report from a multidisciplinary symposium on unmet needs and future directions to maintain cognitive health. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.4, 19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng, X. et al. Impaired pre-synaptic plasticity and visual responses in auxilin-knockout mice. iScience26, 107842 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balleine, B. W. Animal models of action control and cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res.269, 227–255 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan, Y. et al. Experimental models of cognitive impairment for use in Parkinson’s disease research: the distance between reality and ideal. Front. Aging Neurosci.13, 745438 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Decourt, M., Jiménez-Urbieta, H., Benoit-Marand, M. & Fernagut, P. O. Neuropsychiatric and cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease and their modeling in rodents. Biomedicines9, 684 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Mahoney-Crane, C. L. et al. Neuronopathic GBA1L444P mutation accelerates glucosylsphingosine levels and formation of hippocampal alpha-synuclein inclusions. J. Neurosci.43, 501–521 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tayebi, N. et al. Glucocerebrosidase haploinsufficiency in A53T α-synuclein mice impacts disease onset and course. Mol. Genet Metab.122, 198–208 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lado, W. et al. Synaptic and cognitive impairment associated with L444P heterozygous glucocerebrosidase mutation. Brain148, 1621–1638 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Lwin, A., Orvisky, E., Goker-Alpan, O., LaMarca, M. E. & Sidransky, E. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in subjects with parkinsonism. Mol. Genet. Metab.81, 70–73 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gan-Or, Z., Giladi, N. & Orr-Urtreger, A. Differential phenotype in Parkinson’s disease patients with severe versus mild GBA mutations. Brain132, e125 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gan-Or, Z. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations between GBA mutations and Parkinson disease risk and onset. Neurology70, 2277–2283 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altay, M. F. et al. Development and validation of an expanded antibody toolset that captures alpha-synuclein pathological diversity in Lewy body diseases. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.9, 161 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson, J. P. et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem.281, 29739–29752 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker, D. G. et al. Changes in properties of serine 129 phosphorylated α-synuclein with progression of Lewy-type histopathology in human brains. Exp. Neurol.240, 190–204 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kellie, J. F. et al. Quantitative measurement of intact alpha-synuclein proteoforms from post-mortem control and Parkinson’s disease brain tissue by intact protein mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep.4, 5797 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fayyad, M. et al. Investigating the presence of doubly phosphorylated α-synuclein at tyrosine 125 and serine 129 in idiopathic Lewy body diseases. Brain Pathol.30, 831–843 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halliday, G., Hely, M., Reid, W. & Morris, J. The progression of pathology in longitudinally followed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol.115, 409–415 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gómez-Tortosa, E., Irizarry, M. C., Gómez-Isla, T. & Hyman, B. T. Clinical and neuropathological correlates of dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.920, 9–15 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lashuel, H. A. et al. Revisiting the specificity and ability of phospho-S129 antibodies to capture alpha-synuclein biochemical and pathological diversity. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.8, 136 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delic, V. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of phospho-Ser129 α-synuclein monoclonal antibodies. J. Comp. Neurol.526, 1978–1990 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Furderer, M. L. et al. A comparative biochemical and pathological evaluation of brain samples from knock-in murine models of Gaucher disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 1827 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Pastores, G. M. Neuropathic Gaucher disease. Wien. Med. Wochenschr.160, 605–608 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imbalzano, G. et al. Neurological symptoms in adults with Gaucher disease: a systematic review. J. Neurol.271, 3897–3907 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sah, S. et al. Cortical synaptic vulnerabilities revealed in a α-synuclein aggregation model of Parkinson’s disease. bioRxiv10.1101/2024.06.20.599774 (2024).