Abstract

A redox-neutral Fe-electrocatalytic deoxygenative Giese reaction is reported. Hydroxyl groups are among the most abundant functional groups, and thus, the development of efficient reactions for their conversion has significant importance in medicinal and process chemistry. Here, we present a redox-neutral Giese reaction via anodic oxidation to generate phosphonium ions in combination with a cathodic reduction to yield low-valent Fe-catalysts. This reaction represents a promising example of a redox-neutral reaction using an Fe-catalyst and electrochemistry. The results obtained in this study will facilitate the exploration of a wide range of novel reactions employing this redox cycle in the future.

Subject terms: Reaction mechanisms, Electrocatalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Hydroxyl groups are among the most abundant functional groups, and thus, the development of efficient reactions for their conversion has significant importance in medicinal and process chemistry. Here, we present a redox-neutral Giese reaction via anodic oxidation to generate phosphonium ions in combination with a cathodic reduction to yield low-valent Fe-catalysts.

Introduction

The development of efficient transformations of abundant functional groups, such as the hydroxyl group, constitutes a central topic in contemporary synthetic organic chemistry. For example, among the numerous C‒C-bond-formation reactions, the indispensable transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are generally the most reliable1–3, but typically require the use of halogenated substrates and a two-step process involving a halogenation step and the formation of the C‒C bond. In this context, several efficient C‒C-bond-formation reactions based on the conversion of the hydroxyl group have recently been reported (Fig. 1A)4–6. In 2018 and 2022, Suga and Ukaji reported direct conversion reactions of alcohols using titanium reagents7,8. These reactions are applicable to primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols and are particularly useful for the transformation of aliphatic alcohols. In 2020, Wang and Shu reported the first C‒O bond cleavage of tertiary alcohols using Cp*TiCl3 as a catalyst9. Moreover, the development of sustainable chemical reactions that diminish waste using photoredox chemistry10–13 and electrochemistry14–33 has recently gained momentum. In 2021, Li et al. reported a nickel-catalyzed dehydroxylative cross-coupling reaction based on electrochemistry34. This reaction is an excellent way to directly form C(sp2)‒C(sp3) bonds from primary and secondary alcohols. From 2021 to 2023, MacMillan et al. reported direct alcohol-conversion reactions using NHCs, photoredox, and nickel or iron catalysts35–40. This reaction is suitable for primary to tertiary alcohols.

Fig. 1. Evolution of deoxygenative C-C bond formation from traditional approaches to redox-neutral Fe-electrocatalytic deoxygenative Giese reaction: context, concept, and optimization.

A Overview of existing strategies for deoxygenative C–C bond formation from alcohol. B Concept of the Fe-electrocatalytic deoxygenative Giese reaction. C Optimization of the reaction conditions.

Nickel catalysts have been exploited intensively recently due to their abundance and low toxicity. Nickel is a relatively electropositive late transition metal and readily facilitates oxidative addition, which allows the use of cross-couplings between less-reactive reactants34–40. However, due to the highly reactive nature of low-valent nickel species, controlling their reactivity can prove challenging. Furthermore, nickel-catalyzed reactions sometimes require the use of a glove box, which can be a limitation for the development of practical applications.

As with nickel catalysis, the development of iron-based catalysis has been very active in this field41–59. Iron is the most abundant transition metal, minimally toxic, and has the potential for unique and complementary modes of reactivity. Additionally, compared to nickel catalysis, iron catalysis is easier to handle, which enables more practical applications. Despite these virtues, reports of C-C bond formation reactions using iron are limited compared to other transition metals like palladium, copper, nickel, and cobalt. Moreover, many C-C bond formation reactions using Fe-catalysts require strong nucleophiles such as Grignard reagents, which presents challenges in terms of functional group compatibility41–59. Regarding electrocatalytic reactions, only oxidative reactions have been reported so far, which is a current limitation16. In this context, we report here the direct formation of C–C bonds using a redox-neutral Fe-electrocatalytic deoxygenative Giese reaction.

Results

First, an Fe-catalyzed redox-neutral Giese-type reaction was investigated using 4-phenyl-2-butanol (1) and 4-tert-butylstyrene (2) as the substrates (Fig. 1C). The most challenging aspect of this reaction is that the halogenation of the alcohol at the anode and the reduction of the Fe-catalyst at the cathode must proceed at appropriate reaction rates and potentials. Hundreds of combinations of metal catalyst, ligand, base, phosphine, halogen source, electrolyte, electrode, and current values were investigated to optimize the present redox-neutral Giese-type reaction. To determine the optimal conditions for alcohol halogenation at the anode in the present reaction, the conditions from the Ni-catalyzed paired electrolysis approach pioneered by Li et al. were used in the initial attempt34. Detailed investigations revealed that the best results were obtained using FeCl2 (15 mol%), IPr·HCl (L1) (15 mol%), PPh3 (4 eq.), TBAB (4 eq.), DIPEA (4 eq.), and nBu4NBF4 (0.5 eq.) in DMA60,61. In terms of the electrochemical conditions, a current of 6 mA (0.2 mmol scale, constant current) was effective at room temperature in an undivided cell, and the redox-neutral Giese reaction of secondary alcohol 1 and styrene derivative 2 was found to proceed with 60% isolated yield using carbon plates as the anode and Ni foams as the cathode.

Direct control experiments revealed that the desired product (3) was not obtained in the absence of an electric current or Fe-catalyst (entries 1–2). Moreover, the yield was significantly reduced to 10% when a sacrificial Zn electrode was used as the anode instead of a carbon plate (entry 3). Based on these results, it can be concluded that the oxidation at the anode is necessary for this reaction. When a higher constant current (9 mA) was employed, the yield was dropped to 41% (entry 4). It may be attributed to the discrepancies in reaction rates of each subprocess due to the higher current. Similarly, decreased catalyst loading (10 mol%) gave the inferior yield (entries 5). Different Fe-catalysts were also investigated. When Fe(acac)2 was applied, the reaction proceeded, albeit in only 34% yield (entry 6). This was attributed to the fact that Fe(acac)2 has two acac ligands coordinated to Fe, making it very unfavorable for other ligands to coordinate. When FeCl3 was used, the yield decreased to 37% (entry 7), probably because FeCl3 is more hygroscopic than FeCl2; the small amount of water in the reaction system may be the cause of the low yield. Another set of control experiments was performed to investigate the ligand effect of this reaction. Only a 20% yield of 3 was obtained under ligand-free conditions (entry 8). Then, a range of alternative ligands (L2–L7) were screened, but these proved to be ineffective for this reaction (entries 9–14). Several other NHC ligands with varying steric and electronic properties were also examined, but all gave inferior results (see Supplementary information, Figure S16). There appears to be a trend indicating that the use of electron-rich and bulky ligands correlates with increased yields62. In case of the bipyridine ligand, substituent adjacent to the nitrogen atom seems to have an adverse effect on the catalytic activity.

It is worth noting here that the presence of the electrolyte nBu4NBF4 (0.5 eq.) in this reaction promoted a higher yield (entry 15). Next, the halogen source, which also plays a dual role as the electrolyte, was investigated. The yield decreased when TBAI or NaI was used (entries 16–17). This is probably due to the high reactivity of the alkyl iodide generated in the reaction system, which may cause side reactions such as reduction and elimination. Furthermore, the reaction did not proceed when PPh3 was omitted (entry 18). To study the solvent effect, NMP, which is frequently employed inelectrochemical reactions, was tested, but caused the yield to drop to 16% (entry 19). Finally, when the reaction was performed in air, the yield fell below 5% (entry 20).

Based on the above screening results, it was demonstrated that an Fe-catalyst is effective for this electrochemical deoxygenative Giese reaction. To elucidate why the iron catalyst was so effective, attempts were made to perform this reaction using other metals (Ni, Co, Cu, Ti, etc.). The results showed that metal catalysts other than iron (Ni, Co, Cu, Ti) were not effective for this reaction (see Supplementary information, Figure S14). This ineffectiveness is attributed to the formation of byproducts such as the reduced form of alcohol 1 and dimers when non-iron metal catalysts were used. Furthermore, inspired by the reaction conditions reported by Li et al.34 in 2021 for an electrochemical nickel-catalyzed dehydroxylative cross-coupling reaction, the deoxygenative Giese reaction of alcohol 1 was attempted using a Ni-catalyst. However, despite screening various ligands and conditions, the reaction did not proceed with the Ni-catalyst, and the desired compound was scarcely obtained (see Supplementary information, Figure S15). One reason is the difficulty in controlling the process, as low-valent Ni-catalysts generally accelerate the oxidative addition process. Indeed, the byproducts when using Ni-catalysts in this reaction included the reduced, halogenated, and elimination products of alcohol 1, while the desired compound was present only in trace amounts (see Supplementary information, Figure S15). Considering the redox potential of the nickel complex, the reduction of nickel in this electrochemical system is indeed feasible. Consequently, the suboptimal results can be attributed to this excessive reactivity of the Ni-complex.

With the optimal conditions in hand, we investigated the substrate scope. First, we screened different Michael acceptors using 1 as the alcohol and found that a variety of styrene derivatives were applicable as substrates (Fig. 2A). Substrates with alkyl groups such as tBu and Me on the aromatic ring easily provided the desired compounds (3, 4). When styrene was used, the reaction furnished the desired compound (5) in 72% isolated yield. A gram-scale experiment revealed that this reaction can provide 5 in 75% isolated yield. The electrochemical deoxygenative Giese reaction also proceeded using styrene derivatives with electron-withdrawing groups such as fluorine and chlorine. Good yields of the desired products were obtained using fluorine-substituted styrenes (6, 7), while a slight decrease in yield was observed for styrene derivatives with chlorine substituents (8–10). When the reaction was attempted using styrene derivatives substituted with bromine and iodine, dehalogenation was observed, and the desired products were not obtained. The reaction proceeded also for styrene derivatives with different electron-withdrawing ester groups (11–12). The reaction was also applicable to other styrene derivatives, such as 1-vinyl naphthalene, 2-vinyl naphthalene, and 4-vinyl biphenyl (13–15). When the disubstituted olefin 1,1-diphenylethylene and α-methylstyrene were used (16–17), the desired products were obtained. As the functional-group transformation of heterocyclic compounds is particularly important in medicinal chemistry, we applied this reaction to obtain heterocyclic compounds, and the electrochemical deoxygenative Giese reaction was found to proceed for pyridine, thiazole, thiophene, and other heterocycles (18–21). Interestingly, the reaction also proceeded for ferrocene and provided the corresponding product (22) in 23% isolated yield.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of Fe-electrocatalyzed deoxygenative Giese reaction: reactivity across styrene and acrylate derivatives.

A Scope of styrene derivatives. B Scope of acrylate derivatives. aIsolated yields. bFeCl2 (15 mol%), IPr·HCl (15 mol%), PPh3 (4 eq.), TBAB (4 eq.), and DIPEA (4 eq.) were used. cTBAI (4 eq.) was used instead of TBAB. dFeCl2 (20 mol%), IPr·HCl (20 mol%), PPh3 (6 eq.), TBAB (4 eq.), and DIPEA (2 eq.) were used.

Next, acrylate derivatives and other Michael acceptors were investigated (Fig. 2B). The results showed that various acrylate derivatives, including methyl methacrylate, can be applied in this reaction (23–29). To confirm the applicability of different functional groups, this reaction was also tested using Michael acceptors with amino groups and found to be applicable to substrates such as 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate and 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (30, 31). Furthermore, the reaction proceeded well with various acrylate derivatives, including cyclic and acyclic acrylates (32–37). The electrochemical deoxygenative Giese reaction also works well for amides such as 38. A further investigation of different Michael acceptors revealed that the reaction also proceeds well using diethyl vinyl phosphonate (39), which is of great significance for diversity synthesis.

Various primary alcohols were investigated using either tert-butyl methacrylate (40) or styrene (41) as the Michael acceptor (Fig. 3A). The reaction proceeded well with primary alcohols irrespective of the presence of various electron-donating and -withdrawing groups on the aromatic ring (42–52; 62–64). The deoxygenative Giese reaction also proceeded well with alcohols that contain heterocycles such as pyridine rings and with other aliphatic primary alcohols (53–59). The reaction was also effective using primary alcohols derived from important pharmaceuticals such as ibuprofen and naproxen (60, 61).

Fig. 3. Substrate scope of Fe-electrocatalyzed deoxygenative Giese reaction: reactivity across 1° alcohols and 2° alchohols.a,b.

A Scope of 1° alcohols. B Scope of 2° alcohols. aIsolated yields. bFeCl2 (15 mol%), IPr·HCl (15 mol%), PPh3 (4 eq.), TBAB (4 eq.), and DIPEA (4 eq.) were used for 40. FeCl2 (20 mol%), IPr·HCl (20 mol%), PPh3 (6 eq.), TBAB (4 eq.), and DIPEA (2 eq.) were used for 41.

The reaction was also applicable to a wide range of different secondary alcohols (Fig. 3B). When 2-hydroxyindan was used in this reaction, the target product (65) was obtained in 50% isolated yield. On the other hand, 1-hydroxyindan and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthol, which have an alcohol at the benzoic position, gave the target compounds in lower yield (66, 67). The deoxygenative Giese reaction also proceeded with substrates such as cyclohexanol, cycloheptanol, and cyclooctanol (68–70). A further investigation of the substrate scope for this reaction demonstrated that the desired compounds could also be obtained by coupling secondary alcohols with styrene (41) (71–74).

In addition, the reaction was also applicable to steroidal skeletons, which have a variety of biological activities and are important in drug development (75, 76). It is worth noting that 75 can be synthesized on the gram scale. Finally, we confirmed the applicability of the present reaction to a wide range of heterocyclic compounds (77–83); such compounds are extremely important building blocks in medicinal chemistry. These results indicate that this reaction can introduce a broad variety of Michael acceptors to a variety of primary and secondary alcohols (Figs. 2 and 3). For the low-yield compounds in Figs. 2 and 3, mainly debrominated (reduced) compounds were observed as by-products. This is because the Appel reaction at the anode electrode proceeds without problems, but the compounds with slow C-C bond formation by the Giese reaction are gradually reduced by the cathodic reduction. In addition, some compounds containing heteroatoms such as nitrogen and sulfur are easily oxidized, and it is presumed that anodic competition with Shono oxidation-type reactions has resulted in lower reaction yields.

Then, mechanistic studies were carried out to elucidate the underlying reaction mechanism (Fig. 4A). First, cyclopropylmethanol (84) and 4-vinyltoluene (85) were reacted using the standard conditions for this reaction, which furnished the radical ring-opening product 86. The Giese reaction of the chiral compound 87 with 41 afforded racemic compound 77. These experimental results suggest that this reaction follows a radical reaction mechanism.

Fig. 4. Mechanistic studies and application to the gram-scale diversification.

A Mechanistic studies. B Control experiments. C Proposed reaction mechanism. D Application to gram-scale synthesis and diversification.

At the same time, control experiments were performed using (3-bromobutyl)benzene (88), a putative intermediate of this reaction (Fig. 4B). First, we attempted the reaction between 88 and 4-tert-butylstyrene (2) under the standard conditions, except that no electrodes or current was used and Zn dust (10 eq.) or Mn dust (10 eq.) was applied as a chemical reductant. However, the desired compound (3) was not obtained using Mn and Zn dust. The starting material 88 were completely recovered and no side reactions such as dehalogenation or elimination were observed. We also attempted this reaction under the standard conditions with a (+)C plate / (–)Ni foam, but no current flowed (0 mA) and the desired compound (3) was not obtained. Based on these results and the aforementioned control experiments (Fig. 1C, entry 1), it can be concluded that the application of electrochemistry is essential for this reaction. A further control experiment was performed to investigate the effect of FeCl2 on this reaction (Fig. 4B, bottom). Here, sacrificial anodes ((+)Zn plates) were used instead of (+)C plates under the standard reaction conditions, and 3 was isolated in 19% yield in the absence of FeCl2 and IPr·HCl. However, the yield was improved (61% isolated yield) under these conditions when FeCl2 and IPr·HCl were used. These experimental results indicate that FeCl2 and IPr·HCl are crucial in this reaction system.

In their entirety, the mechanistic studies and control experiments, allow proposing a feasible reaction mechanism, which is shown in Fig. 4C. First, as reported by Li et al.34, X- (X = Br or I) is oxidized to Br2 or I2 at the anode. Subsequently, the resulting Br2 or I2 reacts with PPh3, and the Appel reaction proceeds in the presence of the alcohol substrate. The alcohol substrate is then converted to the Mitsunobu intermediate 89, which gives the alkyl halide 90. The resulting alkyl halide 90 undergoes halogen-atom transfer (XAT) through the Fe-complex to form radical intermediate 91. 91 reacts readily with the Michael acceptor to form 92, which is then derivatized by single-electron transfer (SET) to give the desired product (93; path A). The Fe(II) species produced after XAT and SET are expected to be converted to Fe(I) by cathodic reduction and used in the next catalytic cycle. The transformation of 92 to 93 may also be mediated by a hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) mechanism (path B) in addition to the SET mechanism (path A). The potential hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) process can be explained as follows. The HBr generated through the Appel reaction, which proceeds via anodic oxidation, is captured by DIPEA. Consequently, the resulting HBr salt of DIPEA serves as a proficient hydrogen atom source. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the potential HAT process from intermediate 92 is mediated by an excess of DIPEA or its HBr salt present in the reaction system.

To demonstrate the utility of this reaction, a gram-scale synthesis and diversification study were conducted using lithocholic acid methyl ester (94), which contains the RelyvrioTM scaffold (Fig. 4D)63. As expected, the reaction proceeded well at the 10-mmol scale (3.9 g of 94), and the target compound 95 was successfully obtained in 60% yield (dr = 1:1; 2.9 g). Further attempts were made to diversify 94 at the 0.4 mmol scale. We found that various Michael acceptors could be introduced into 94 in a single step (96–105). This diversification method could be applied to various bioactive and medically important compounds with hydroxyl groups.

For a better understanding of the unprecedented XAT process catalyzed by the iron complex, a mechanistic investigation was conducted. Initially, the use of the stoichiometric amount of the Fe(II)-IPr complex was examined without electrolysis. However, even upon adding one equivalent of the Fe(II)-IPr complex, the desired reaction did not proceed, and the alkyl halide was quantitatively recovered (see Supplementary information, Figure S17). This observation suggests that the catalytic cycle in this reaction does not involve Fe(II)/ Fe(III). Then, DFT calculations on the XAT process mediated by Fe(II)/ Fe(III) were performed. However, the energy of the product state is significantly higher than that of the initial state. Additionally, the activation energy was nearly comparable with the product state energy. These results also indicates that the XAT process involving Fe(II)/ Fe(III) catalytic cycle is energetically unfavourable.

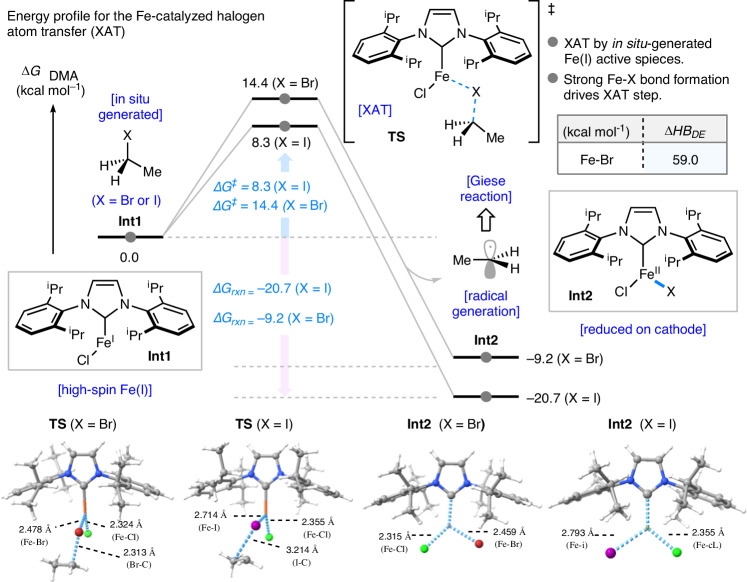

Subsequent DFT calculations were conducted to investigate the halogen atom transfer (XAT) process mediated by the Fe(I)/Fe(II) catalytic cycle (Fig. 5). In the DFT calculations, the high-spin state of iron was assumed based on the study by Nakamura and co-workers64,65. Ethyl bromide (EtBr) and ethyl iodide (EtI) were employed as substrates, with separate calculations performed for each. The XAT process is initiated by the in-situ generated Fe(I) species, Int-1. The computed activation barriers for the halogen atom transfer transition states (TS) are 14.4 kcal/mol for EtBr and 8.3 kcal/mol for EtI, respectively, relative to Int-1 as the ground state. This transformation is highly exergonic, with reaction free energies exceeding 10 kcal/mol, and leads to the formation of an ethyl radical and the Fe(II) species, Int-2. Computational results revealed that, in both EtBr and EtI cases, the rate-determining step is the process leading to the transition state of XAT. Comparison of the two substrates showed that the pathway involving EtI proceeds through a more thermodynamically stable transition state, rendering it a more favorable process.

Fig. 5. Energy profile for the Fe-catalyzed halogen atom transfer.

Schematic representation of XAT transition state, computed at the SMD(DMA)-(U)B3LYP-D3BJ/BS1 level of theory. Energies (kcal mol–1) and bond lengths (Å) are provided in the insert.

Furthermore, Nakamura and coworkers have reported a similar mechanistic investigation of the Fe-catalyzed halogen atom transfer, involving DFT calculations64,65. These studies suggested that the XAT process is more likely to be mediated by Fe(I)/ Fe(II) catalytic cycle, rather than Fe(II)/ Fe(III) cycle, based on a comparative analysis of calculation results. These experimental and computational results, along with reported studies64,65, indicate that the XAT process in this reaction is likely mediated by the Fe(I)/ Fe(II) catalytic cycle.

Further detailed experiments were then conducted to investigate the mechanism of this reaction (Fig. 6). Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed to investigate the electrochemical properties of various chemical species. (Fig. 6A) The redox potentials of the FeCl2·IPr complex have already been reported66. The CV spectrum of the FeCl2·IPr complex, synthesized in the same way as that used in the reaction, was measured (Fig. 6A). As a result, it was revealed that the reduction potential of FeCl2·IPr complex was within the redox potential range of our reaction system. Considering the electrode potentials (cathode: −1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl, anode: +1.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl), the FeCl2·IPr complex can be electrochemically reduced in the reaction system. It supports the Fe-catalyst regeneration process in the catalytic cycle (Fig. 4C). Additionally, an oxidation peak was observed at Eox = +0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl, which is similar to the oxidation peak of DIPEA. Stoichiometric amounts of DIPEA were used to synthesize FeCl2·IPr complex. The observed peak is presumed to be attributed to the residual DIPEA.

Fig. 6. Further mechanistic studies and 1H NMR reaction monitoring.

A Cyclic voltammetry. B limitation of the substrates. C NMR trace.

An irreversible oxidation peak was observed for TBAB at Eox = +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl. This result supports the proposed mechanism (Fig. 4C) in which the anodic oxidation of TBAB generates reactive species through the reaction of Br2 and triphenylphosphine. Triphenylphosphine exhibited an irreversible oxidation peak (Eox = +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl). It can undergo anodic oxidation and be consumed in the system. An excess amount of triphenylphosphine is essential in this reaction, presumably due to competing anodic oxidation.

Similarly, 4-tBu-styrene displayed an irreversible oxidation peak at Eox = +1.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl. DIPEA showed an irreversible oxidation peak at Eox = +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl, suggesting DIPEA can be oxidized in the reaction system. The resulting DIPEA radical cation may mediate the HAT process, as shown in Fig. 4C. This mechanism is speculated to compete with the single electron transfer process mediated by the Fe-catalyst. On the other hand, 4-phenylbutan-2-ol (1) was confirmed to be stable in the reaction system, as no significant redox peak was observed. In other words, the activation of the alcohol through the Appel reaction is speculated to be essential in this reaction.

The control experiments of this reaction to tertiary alcohols were performed (Fig. 6B)66. When the optimal conditions (Fig. 1C) were applied to 2-methyl-4-phenyl-2-butanol (106) and adamantan-1-ol (107), only the starting materials were recovered, and the desired products were not observed. The limitation suggested here is consistent with that reported by Li et al.34.

The reaction using 4-phenylbutan-2-ol (1) and styrene (41) was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 6C). After two hours, a significant amount of the starting material 1 remained, and the ratio of starting material 1 to the desired product 5 was 94:6 (determined by 1H NMR). After six hours, the reaction had partially proceeded, and the desired product 5 was observed at a ratio of 52:48. Ten hours after, the starting material 1 was consumed, and the desired product 5 was observed at a ratio of 15:85. After 20 hours, the starting material 1 had completely disappeared, giving the desired product 5 in 72% yield. Noteworthy, the brominated compound 88 was not observed in any 1H NMR spectra. This observation suggests that the brominated compound 88 promptly underwent the XAT process mediated by Fe-catalyst and was converted to compound 5. As a control experiment, the reaction was conducted using normal DMA instead of dehydrating DMA, and the yield dropped to 33%. This is assumed to be due to the decomposition of Mitsunobu intermediate 89 by water present in the reaction system during the Appel reaction.

Discussion

The redox-neutral Fe-electrocatalytic deoxygenative Giese reaction reported herein represents a powerful approach for the one-step installation of Michael acceptors into both primary and secondary alcohols. The key feature of this reaction is that it allows the use of readily available commercial reagents to effortlessly form C‒C bonds from alcohols at ambient temperature without the use of scarce metals or highly toxic reagents. In addition, an unprecedented cathodic reduction of the Fe-complex has been realized, which effectively promotes this Giese reaction. Coupled with the Appel reaction via anodic oxidation, this redox-neutral Giese reaction is characterized by high levels of efficiency for small-molecule diversification. This methodology represents a pioneering investigation into the fusion of Fe-catalysis and electrochemistry in the field of redox-neutral reactions. Further exploration of a broad range of innovative reactions using this redox cycle promises significant potential. Moreover, this approach is expected to lead to further advances in the field of medicinal chemistry.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this work was provided by a grant from the RGC of the Hong Kong SAR, China (ECS, HKUST 26302024), and start-up funds from HKUST (Project No. R9820) to H.N. The computation was partly performed using Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (Projects: 23-IMS-C119, 24-IMS-C114, and 25-IMS-C115 Y.N.).

Author contributions

L.Y., S.Li., H.O., H.N. conducted the experiments. H.N. conceptualized and designed the catalytic strategy. Y.N. conducted the computational study. The manuscript was prepared by H.N. with the feedback of all other authors. L.Y., S.Li., H.O. prepared the supplementary information under the guidance of H.N. For the mechanistic study, Y.M. and Q.C. contributed to the cyclic voltammetry. K.Y. contributed to the design of the mechanistic study.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The authors declare that all experimental and computational data generated in this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, NMR, and DFT-optimized structure coordinates, are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Longhui Yu, Shangzhao Li, Hiroshige Ogawa.

Contributor Information

Yuuya Nagata, Email: NAGATA.Yuuya@nims.go.jp.

Hugh Nakamura, Email: hnakamura@ust.hk.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-63515-x.

References

- 1.Tsuji, J. Palladium Reagents and Catalysts: New Perspectives for the 21st Century 2nd ed. (Wiley, New York, 2004).

- 2.Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis (University Science Books, New York, 2009).

- 3.Gladysz, J. A. Introduction to frontiers in transition metal catalyzed reactions (and a brief adieu). Chem. Rev.111, 1167–1169 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villo, P., Shatskiy, A., Kärkäs, M. D. & Lundberg, H. Electrosynthetic C‒O Bond Activation in Alcohols and Alcohol Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202211952 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang, Y., Xu, J., Pan, Y. & Wang, Y. Recent advances in electrochemical deoxygenation reactions of organic compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem.21, 1121–1133 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anwar, K., Merkens, K., Aguilar Troyano, F. J. & Gómez-Suárez, A. Radical deoxyfunctionalisation strategies. Eur. J. Org. Chem.2022, e202200330 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suga, T., Shimazu, S. & Ukaji, Y. Low-Valent titanium-mediated radical conjugate addition using benzyl alcohols as benzyl radical sources. Org. Lett.20, 5389–5392 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suga, T., Takahashi, Y., Miki, C. & Ukaji, Y. Direct and unified access to carbon radicals from aliphatic alcohols by cost-efficient titanium-mediated homolytic C-OH bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202112533 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shu, X.-H. et al. Radical dehydroxylative alkylation of tertiary alcohols by Ti catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 16787–16794 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, J., Lv, X. & Jiang, Z. Visible-light-mediated photocatalytic deracemization. Chem. Eur. J.29, e202204029 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin, Y., Zhao, X., Qiao, B. & Jiang, Z. Cooperative photoredox and chiral hydrogen-bonding catalysis. Org. Chem. Front.7, 1283–1296 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beil, S. B., Chen, T. Q., Intermaggio, N. E. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Carboxylic acids as adaptive functional groups in metallaphotoredox catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res.55, 3481–3494 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macmillan, D. W. C. et al. Chem. Rev.122, 1485–1542 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiti, D. et al. Non-directed Pd-catalysed electrooxidative olefination of arenes. Chem. Sci.13, 9432–9439 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu, Y., Scheremetjew, A. & Ackermann, L. Electro-oxidative C‒C alkenylation by rhodium(III) catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 2731–2738 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei, R., Sauermann, N., Oliveira, J. C. A. & Ackermann, L. Electroremovable traceless hydrazides for cobalt-catalyzed electro-oxidative C‒H/N‒H activation with internal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 7913–7921 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundberg, H. et al. Electroreductive desulfurative transformations with thioethers as alkyl radical precursors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202304272 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, S. et al. Electrochemically driven cross-electrophile coupling of alkyl halides. Nature604, 292–297 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mei, T.-S. et al. Electrochemistry-enabled Ir-catalyzed vinylic C‒H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 18970–18976 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mei, T.-S. et al. TEMPO-Enabled Electrochemical Enantioselective Oxidative Coupling of Secondary Acyclic Amines with Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc.143, 15599–15605 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong, P., Xu, H.-H., Song, J. & Xu, H.-C. Electrochemical difluoromethylarylation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 2460–2464 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, S. et al. Anodically Coupled Electrolysis for the Heterodifunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 2438–2441 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, H.-C. et al. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis enables site- and enantioselective cyanation of benzylic C–H bonds. Nat. Catal.5, 943–951 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baran, P. S. et al. Ni-electrocatalytic Csp3–Csp3 doubly decarboxylative coupling. Nature606, 313–318 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan, M., Kawamata, Y. & Baran, P. S. Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev.117, 13230–13319 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baran, P. S. et al. A Survival Guide for the “Electro-curious. Acc. Chem. Res.53, 72–83 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hupp, J. T. et al. Charge transport in zirconium-based metal–organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res.53, 1187–1195 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moeller, K. D. Using physical organic chemistry to shape the course of electrochemical reactions. Chem. Rev.118, 4817–4833 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little, R. D. A perspective on organic electrochemistry. J. Org. Chem.85, 13375–13390 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little, R. D. et al. Versatile tools for understanding electrosynthetic mechanisms. Chem. Rev.122, 3292–3335 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little, R. D. & Moeller, K. D. Introduction: Electrochemistry: Technology, synthesis, energy, and materials. Chem. Rev.118, 4483–4484 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wirtanen, T., Prenzel, T., Tessonnier, J.-P. & Waldvogel, S. R. Cathodic corrosion of metal electrodes-how to prevent it in electroorganic synthesis. Chem. Rev.121, 10241–10270 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, Y., Li, P., Wang, Y. & Qiu, Y. Electroreductive Cross-Electrophile Coupling (eXEC) Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202306679 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Li, C. et al. Electrochemically Enabled, Nickel-Catalyzed Dehydroxylative Cross-Coupling of Alcohols with Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc.143, 3536–3543 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyon, W. L. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Expedient Access to Underexplored Chemical Space: Deoxygenative C(sp3)‒C(sp3) Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 7736–7742 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gould, C. A., Pace, A. L. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Rapid and Modular Access to Quaternary Carbons from Tertiary Alcohols via Bimolecular Homolytic Substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 16330–16336 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, J. Z., Sakai, H. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Alcohols as Alkylating Agents: Photoredox-Catalyzed Conjugate Alkylation via in Situ Deoxygenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202207150 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Intermaggio, N. E., Millet, A., Davis, D. L. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Deoxytrifluoromethylation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 11961–11968 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai, H. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Nontraditional Fragment Couplings of Alcohols and Carboxylic Acids: C(sp3)‒C(sp3) Cross-Coupling via Radical Sorting. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 6185–6192 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong, Z. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative arylation of alcohols. Nature598, 451–456 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shang, R., Ilies, L. & Nakamura, E. Iron-Catalyzed Directed C(sp2)‒H and C(sp3)‒H Functionalization with Trimethylaluminum. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 7660–7663 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shang, R., Ilies, L. & Nakamura, E. Iron-Catalyzed Ortho C‒H Methylation of Aromatics Bearing a Simple Carbonyl Group with Methylaluminum and Tridentate Phosphine Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 10132–10135 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doba, T., Matsubara, T., Ilies, L., Shang, R. & Nakamura, E. Homocoupling-free iron-catalysed twofold C–H activation/cross-couplings of aromatics via transient connection of reactants. Nat. Cat.2, 400–406 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norinder, J., Matsumoto, A., Yoshikai, N. & Nakamura, E. Iron-catalyzed direct arylation through directed C‒H bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 5858–5859 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshikai, N., Matsumoto, A., Norinder, J. & Nakamura, E. Iron-catalyzed chemoselective ortho arylation of aryl imines by directed C-H bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 2925–2928 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshikai, N., Mieczkowski, A., Matsumoto, A., Ilies, L. & Nakamura, E. Iron-catalyzed C‒C bond formation at alpha-position of aliphatic amines via C‒H bond activation through 1,5-hydrogen transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 5568–5569 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazzacano, T. J. & Mankad, N. P. Base metal catalysts for photochemical C‒H borylation that utilize metal-metal cooperativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 17258–17261 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ackermann, L. et al. Iron-Catalyzed C‒H Activation with Propargyl Acetates: Mechanistic Insights into Iron(II) by Experiment, Kinetics, Mössbauer Spectroscopy, and Computation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 12874–12878 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mo, J., Müller, T., Oliveira, J. C. A. & Ackermann, L. 1,4-Iron Migration for Expedient Allene Annulations through Iron-Catalyzed C‒H/N‒H/C‒O/C‒H Functionalizations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 7719–7723 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu, C., Stangier, M., Oliveira, J. C. A., Massignan, L. & Ackermann, L. Iron-Electrocatalyzed C‒H Arylations: Mechanistic Insights into Oxidation-Induced Reductive Elimination for Ferraelectrocatalysis. Chem. Eur. J.25, 16382–16389 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green, S. A., Vásquez-Céspedes, S. & Shenvi, R. A. Iron-nickel dual-catalysis: A new engine for olefin functionalization and the formation of Quaternary centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 11317–11324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shenvi, R. A. et al. Iron-Catalyzed Hydrobenzylation: Stereoselective Synthesis of (-)-Eugenial C. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 15714–15720 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mako, T. L. & Byers, J. A. Recent advances in iron-catalysed cross coupling reactions and their mechanistic underpinning. Inorg. Chem. Front.3, 766–790 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheiper, B., Bonnekessel, M., Krause, H. & Fürstner, A. Selective iron-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of grignard reagents with enol triflates, acid chlorides, and dichloroarenes. J. Org. Chem.69, 3943–3949 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fürstner, A., Leitner, A., Méndez, M. & Krause, H. Iron-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.124, 13856–13863 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong, X., Yang, Z.-P., Del Angel Aguilar, C. E. & Fu, G. C. Iron-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Electrophiles with Olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202306663 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin, M., Adak, L. & Nakamura, M. Iron-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Coupling Reactions of α-Chloroesters with Aryl Grignard Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 7128–7134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kessler, S. N. & Bäckvall, J.-E. Iron-catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Propargyl Carboxylates and Grignard Reagents: Synthesis of Substituted Allenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.55, 3734–3738 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaik, S. Iron opens up to high activity. Nat. Chem.2, 347–349 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liang, Q. & Song, D. Iron N-heterocyclic carbene complexes in homogeneous catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev.49, 1209–1232 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kühn, F. E. et al. Chemistry of iron N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: syntheses, structures, reactivities, and catalytic applications. Chem. Rev.114, 5215–5272 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones, G. O., Liu, P., Houk, K. N. & Buchwald, S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 6205–6213 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aschenbrenner, D. S. New drug approved for ALS. Am. J. Nurs.123, 22–23 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma, A. K. et al. DFT and AFIR Study on the Mechanism and the Origin of Enantioselectivity in Iron-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.139, 16117–16125 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma, A. K. & Nakamura, M. A DFT study on FeI/FeII/FeIII mechanism of the cross-coupling between haloalkane and aryl grignard reagent catalyzed by iron-SciOPP complexes. Molecules25, 3612 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Przyojski, J. A., Arman, H. D. & Tonzetich, Z. J. Complexes of Iron(II) and Iron(III) Containing Aryl-Substituted N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Organometallics31, 3264–3271 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all experimental and computational data generated in this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, NMR, and DFT-optimized structure coordinates, are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.