Abstract

We report a case of a 36-year-old man who developed a lung hernia after a minimally invasive mitral valve repair. Lung hernias are uncommon. Most are acquired and may be classified as traumatic, spontaneous, pathologic, or postoperative. In theory, minimal-access surgical techniques should decrease the likelihood of herniation, in comparison with open thoracotomy. Our review of the literature revealed only 2 reports of this sequela in association with this surgical procedure. Repair was performed due to persistent symptoms, including pleurisy and dyspnea, and interference with the patient's daily activities. Surgical repair led to complete resolution of these problems. (Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29:203–5)

Key words: Case report; hernia/etiology; hernia/radiography; hernia/surgery; lung diseases/etiology; male; surgical mesh; ribs/surgery; surgical procedures, minimally invasive/adverse effects; thoracotomy/methods; thoracotomy/adverse effects

Lung hernia is an uncommon entity, with fewer than 300 cases reported in the world literature as of 1996. 1 Lung herniation as a sequela to thoracotomy is even rarer. 2 The limited-access surgical approach was developed to reduce the complications and cosmetic disadvantages of sternal incision. We found 2 reported cases of lung herniation after limited-access thoracotomy. 2,3

We report herein a case of lung herniation after limited-access mitral valve repair.

Case Report

In March 2001, a 36-year-old man presented at another institution with a complaint of easy fatigability and dyspnea on exertion. He had a history of mitral valve prolapse, severe mitral regurgitation, and enlarged left atrium. His echocardiographic findings showed a doubling (upon exercise) of estimated systolic pulmonary pressures from 30–35 mmHg to 60–65 mmHg. Mitral valve surgery was recommended, and he chose limited-access heart surgery. The procedure was performed uneventfully, and he was discharged 4 days later.

Soon after discharge, the patient experienced shortness of breath. Two weeks after surgery, he returned to the institution where the surgery had been performed and underwent thoracocentesis: 800 cc of pleural fluid was removed. This provided temporary improvement, but he soon returned with a sensation of “something popping out of my chest” when he coughed. He was not experiencing fever, chills, night sweats, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or hemoptysis. On clinical examination, his vital signs were all normal. Room-air pulse oximetry showed an oxygen saturation of 96%. Positive findings on clinical examination included decreased breath sounds and dullness to percussion about one third of the way up the right hemithorax. A nicely healed 14-cm scar was noted over the right breast, 1 inch below the nipple. Upon deep coughing, the right pectoral muscle and breast appeared to inflate; deflation occurred spontaneously. The exam was otherwise negative.

The patient was monitored clinically for a brief period but continued to complain of pain on both sides of his chest, which was pleuritic in character. He also felt his lung “popping” more frequently, even without Valsalva's maneuver or a cough.

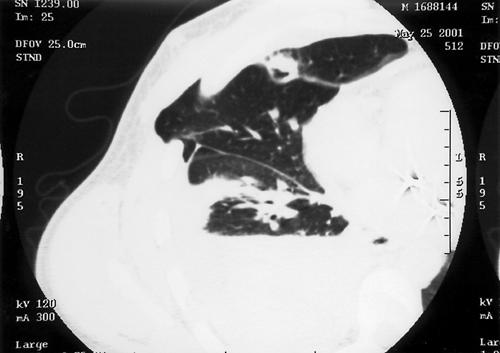

Six weeks postoperatively, the patient was referred to our center, and we performed computed tomography (CT) of the chest during Valsalva's maneuver. This study showed a right pleural effusion with loculation, 2 thick-walled cysts in the right middle lobe, and a definite pulmonary herniation (Fig. 1). Surgical repair was recommended.

Fig. 1 This computed-tomographic section of the chest performed during Valsalva's maneuver shows the hernia passing through the chest wall. Also note a traumatic cyst lying along the minor fissure. Right lower-lobe atelectasis and an effusion are also noted.

Operative repair of the hernia was performed. The patient was positioned in a 30° semilateral right decubitus position, with split-lung ventilation. The previous skin and pectoralis major muscle incision was opened and the defect in the chest wall was easily found and débrided. There was an identifiable hernial sac, which was resected. Adhesions in the chest were lysed and a 1,000-mL clear serous effusion was drained. The effusion was sterile on subsequent culture. A small wedge of middle lobe, containing the cystic lesions seen on the chest CT image, was excised.

The repair was performed using a double thickness of Marlex mesh (Bard; Cranston, RI). Approximately 24 sutures were passed through the edges of the defect and then through the mesh in such a fashion as to create a “drum-tight” barrier between the pleural space and the subpectoral space. To avoid intercostal bundle entrapment by taut suture material, sutures were passed through drill holes placed directly through the ribs. The muscular, subcutaneous, and cutaneous layers were then closed with absorbable sutures. The patient was extubated on the operating table and discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 3.

Discussion

Lung herniation is rare. Roland first described herniation of pulmonary tissue in 1499. 4 Maurer and Blades 5 established the definition of lung herniation in 1946 as “a protrusion of the pleural-covered lung beyond its normal boundaries through an abnormal opening in the thoracic enclosure.” 5 Morel-Lavalée 6 divided hernias of the lung according to site and cause. Eighty percent of hernias are acquired 7 and can be classified as traumatic, spontaneous, pathologic, or postsurgical. 3 Hernia does not pose a serious threat unless incarceration and strangulation of the pulmonary tissue occurs. Hemoptysis and pain at the site of the hernia herald these. 8 Post-thoracotomy lung herniation usually develops secondary to surgical resection of a chest-wall component without appropriate reconstruction. 9

In minimal-access thoracotomy, it is frequently the case that the intercostal incision is significantly longer than the skin incision. This appears to have been the case in our patient. It is imperative during closure to gain exposure of the separated ribs under the intact skin, in order to place accurate pericostal closure sutures. This is difficult when the incision is small, in comparison with that of a full thoracotomy.

In addition, it is important to limit the patient's activity during the period of chest-wall healing, regardless of the length of the skin incision. In our patient, early resumption of strenuous activity most likely facilitated the development of the lung hernia.

Minimally invasive limited-access mitral valve surgery can accelerate recovery and decrease pain, while maintaining overall surgical efficacy. Herniation may be missed on routine chest radiography. Valsalva's maneuver is often required to reveal the condition, as in our patient. Although a CT scan is not necessary to diagnose symptomatic lung hernia, 9 it better defines the dimensions of the hernia and the location and size of the defect. 10 Differential diagnosis of lung hernia includes subcutaneous emphysema, bronchopleural fistula, a gas-forming infection, and lipoma.

Treatment of symptomatic lung hernia is surgical and is determined by factors such as size, pain, recurrent chest infections, incarceration of tissue, and paradoxical respiration with poor ventilation. True hernias of the lung seldom heal spontaneously; therefore, surgical treatment is usually needed. 5

During the operation, identification of the hernial sac and defect is essential so that the lung can be freed from adhesions and reduced into the thoracic cavity. 9 Larger defects may require implantation of a rigid chest-wall substitute, such as a “sandwich” composed of methyl methacrylate between 2 layers of Marlex mesh. Soft-tissue coverage with skin grafts, muscle flaps, or omentum is necessary only if soft tissue has been lost.

In conclusion, postoperative lung herniation is rarely associated with minimally invasive thoracotomy and should be considered in the evaluation of any persistent postoperative pain and swelling after chest surgery.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Alan S. Multz, MD, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 270-05 76th Avenue, New Hyde Park, NY 11040

References

- 1.Brown WT, Hauser M, Keller FA. Hernia of the lung repaired by VATS: a case report. J Laparoendosc Surg 1996;6(6):427–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Deeik RK, Memon MA, Sugimoto JT. Lung herniation secondary to minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:1772–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.van den Brink WA, Meek JC, Boelhouwer RU. Herniation of the lung following video-assisted minithoracotomy. Surg Endosc 1995;9(6):706–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Roland. De pulmonibus sanaripot. In: Chavliac G, editor. Cyrurgia. Liber III (cap); p 144.

- 5.Maurer E, Blades B. Hernia of the lung. J Thorac Surg 1946;15:77–98. [PubMed]

- 6.Morel-Lavalee A. Hernies du poumon. Bull Mem Soc Chir Paris 1845;1:75–195.

- 7.Montgomery JG, Lutz H. Hernia of the lung. Ann Surg 1925;82:220–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Minai OA, Hammond G, Curtis A. Hernia of the lung: a case report and review of literature. Conn Med 1997;61(2):77–81. [PubMed]

- 9.Sonett JR, O'Shea MA, Caushaj PF, Kulkarni MG, Sandstrom SH. Hernia of the lung: case report and literature review. Ir J Med Sci 1994;163(9):410–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bhalla M, Leitman BS, Forcade C, Stern E, Naidich DP, McCauley DI. Lung hernia: radiographic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;154:51–3. [DOI] [PubMed]