Abstract

Background

Researchers across the United States often leverage community engagement (CE) as a strategy in interventions aiming to alter the retail food environment (RFE), especially in areas serving racially segregated neighborhoods with low incomes. However, little is known about the full breadth, intensity, and approaches used to engage communities in RFE intervention work.

Objective

The purpose of this scoping review is to identify what CE research approaches have been applied by researchers in the RFE intervention literature and how they vary by type of retail settings, phase of intervention, year of intervention, and key domains of equity.

Methods

Following the JBI (formerly known as Joanna Briggs Institute) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) extension for Scoping Review guidelines, any study published in academic journals and English that discussed activities or strategies for CE in RFEs, irrespective of the type of study, was included. PubMed, CINAHL, and ProQuest were searched for reports published from inception until August 2023. CE research strategies were extracted and classified following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) continuum of community engagement framework, including outreach (lowest CE), consult/involve, collaboration, and shared leadership (highest CE). CE research strategies were then examined for their variation across RFE setting, intervention phase, intervention year, and key equity domains related to healthy food retail (eg, affordability).

Results

A total of 98 RFE interventions reported in 104 reports were included in this review, and most were implemented in either supermarkets (21%), corner stores (20%), or multiple RFE settings (21%). All interventions employed CE research strategies of outreach (n = 98), whereas approximately half employed strategies of shared leadership (n = 52). Exploring CE research strategies by RFE settings and intervention phase, this review found stronger forms of CE in less traditional RFE settings, including mobile markets, and among interventions that used CE research strategies across all phases of the intervention study. RFE interventions that implemented the highest forms of CE research strategies (ie, shared leadership) were also those that addressed all key equity domains.

Conclusion

The findings of this review reveal that the form of CE in RFE interventions varied widely, with more domains of equity addressed when higher forms of CE were used. Insights from this review suggest that future research should prioritize assessing the effectiveness of shared leadership CE strategies on achieving and sustaining nutrition-related health equity outcomes for communities.

Keywords: Community engagement, Health equity, Food retail environment, Food retail interventions, Community inclusiveness

UNHEALTHY DIETS CONTRIBUTE TO THE DEVELOPment of multiple chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.1-3 These chronic disease conditions disproportionately burden certain communities and groups, including families with low incomes, communities of color, indigenous people, and racially segregated neighborhoods.4,5 Diet-related health disparities are partially attributable to social and structural barriers in the retail food environment (RFE),4 such as structural racism and economic inequality, which can impact the types of stores and products made available. The RFE is typically operationalized as the main place (eg, grocery store, corner store, farmers market) where people purchase their food within a community.6 The RFE is shaped by a complex network of physical, social, economic, cultural, and political factors that interact at the consumer, store, and community levels.7 These factors determine the accessibility, availability, and affordability of food in any community and influence consumers’ dietary choices and nutritional status, as well as other population health outcomes.8 Thus, for many interventions focused on community nutrition, the RFE serves as a key venue for implementing strategies.

Intervention research around addressing the RFE to promote population health has had an exponential growth in the past 2 decades. A variety of different strategies have been implemented, such as introducing healthy foods at existing stores, introducing new food stores, raising nutrition knowledge of consumers or community residents via product labels, and leveraging the 4 Ps of marketing (ie, product, price, place, and promotion) to promote healthy food availability and purchasing.9-12 An integral part of many of these interventions is to shape dietary behavior and promote better nutrition-related health outcomes of communities by attracting consumer9,11 and/or community engagement (CE).9,12 Directly engaging communities enables researchers to understand local contexts that can support more effective implementation and sustainability of intervention strategies.13 Such engagement is particularly critical for interventions focusing on historically and intentionally excluded communities, because evidence demonstrates that more relevant and effective interventions can be developed by forming supportive relationships, enhancing community capacity, and involving the community in decision-making.13 Hence, comprehensive and participatory approaches in RFE interventions are essential to reduce diet-related health inequities.

Meaningful CE that centers diversity, equity, inclusion, and ownership14 can be complex and challenging, but also very rewarding. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CE can be defined as a mechanism that involves people, partnerships, and coalitions who serve as catalysts for mobilizing community resources to influence systems toward improving the health and well-being of the community.14 Often guided by principles of the Community-Based Participatory Research model (CBPR), the emphasis of CE is a collaborative process that requires understanding the strengths of each partner and involving them in all aspects of the intervention or program.15 CE has the potential to transform the power dynamics between partners through the adoption of community inclusiveness in decision-making.16

CBPR has been widely implemented in public health interventions, including those focusing on the RFE.12 Although numerous individual publications on strategies to engage communities in RFE changes have been described,10-12,17 little is understood about the entire breadth, intensity, and methodological approaches used for CE in the RFE intervention literature and how well these studies address equity. Existing systematic or scoping reviews that focus on RFE interventions have explored the impact on diet and health,18,19 healthy food consumption,20 and obesity-related outcomes.21 Although these reviews help to summarize the wider RFE literature on effective approaches for health,18-21 most of these reviews do not focus on the specific CE research approaches used. In addition, only 1 prior review was identified that examined the use of CE strategies in RFE interventions,22 yet they only considered 1 CE research approach (eg, shared decision-making) and not the complete spectrum of potential strategies.

To fill these gaps, this scoping review aimed to identify what CE research approaches have been applied by researchers in RFE intervention literature. Specifically, this review examined the form and extent of CE in RFE interventions and how CE varied across RFE settings, intervention design phase (eg, planning, implementation), and intervention year. Furthermore, the review aimed to examine whether consideration of equity as defined by Kumanyika (2019)23 and Mui et al (2021)24 were included in the RFE intervention design; namely, if interventions increased healthy food availability and options, affordability, or accessibility for historically and intentionally excluded communities (eg, low-income, Indigenous).

METHODS

This scoping review was performed using guidance from the JBI scoping review25 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).26 An initial protocol was drafted and shared with all co-authors for feedback. The protocol was registered under Open Science Framework registration and is available at https://osf.io/q6jtz, and all authors agreed on iterative protocol development as needed.

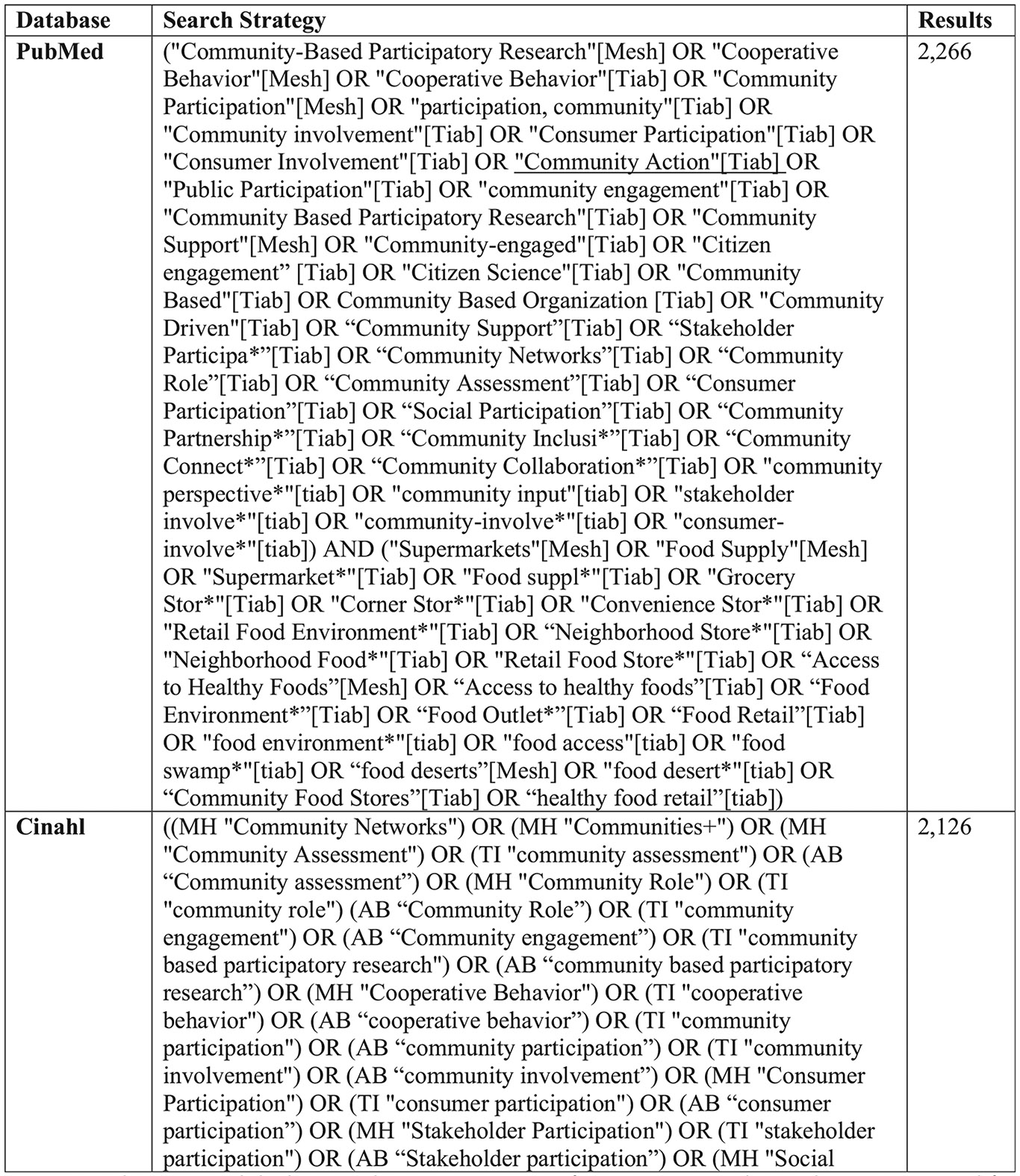

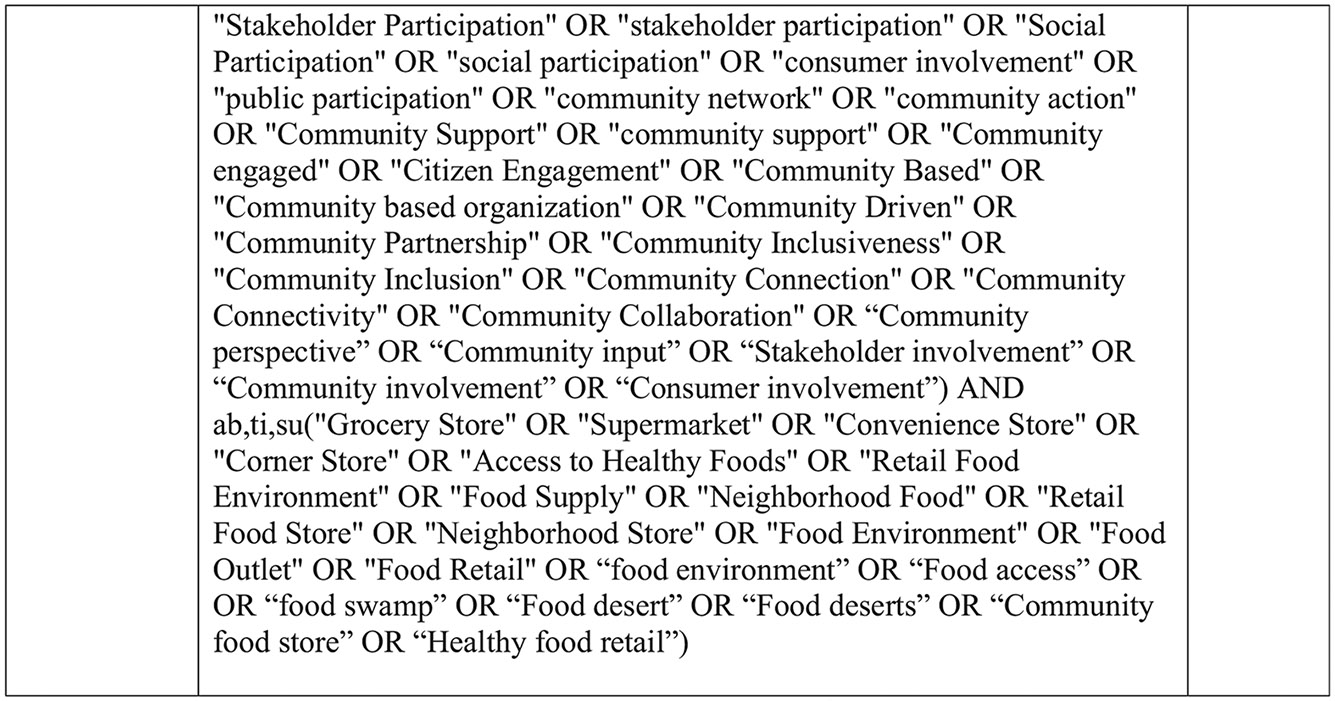

Search Strategy

The search strategy was created in collaboration with the University of Illinois College of Medicine Rockford’s research librarian, with test searches run in December 2022. The first database searches were executed on January 6, 2023, and they were rerun on August 18, 2023, to capture any new publication(s) since the first search. PubMed, CINAHL, as well as 5 databases in ProQuest (APA PsycInfo, PAIS Index, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, and Sociological Abstracts) were searched. The search included terms related to the concepts of “retail food environment (RFE)” and “community engagement (CE).” The search process was iterative, and additional terms were added as identified throughout the process to create the final search strategy (Supplementary Figure 1). The team also searched for additional citations of extracted reports.

Eligibility Criteria

Following the JBI recommendations,25 inclusion criteria were defined around context, concept, and population of interest. The context was retail food stores in the United States, given the unique, longstanding systematic injustices in neighborhood resource allocation, including food access, that historically marginalized communities in the United States continue to experience.27 A broad definition of retail food stores, including “any establishment where food is offered to the consumer and intended for off-premises consumption”28 was used. This encompassed a wide range of settings, such as supermarkets, grocery stores, corner stores, gas marts, dollar stores, ethnic grocers, community food stores, farmers markets, mobile markets, and restaurants. The concept was RFE interventions implementing environmental change strategies to promote healthy eating environments in communities (eg, increasing food outlets or adapting the environment of existing food outlets to offer healthy food). Any participant who was involved or participated in RFE interventions was our population of interest. The measured outcome was activities used to engage communities in any RFE intervention.

Following the inclusion/exclusion criteria, reports written in English were considered. While ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I and ProQuest Dissertations databases were searched, our final inclusion/exclusion criteria required reports to be published in academic journals. Any reports that discussed the activities or strategies to engage customers or communities in RFE interventions, regardless of the type of manuscript (such as protocol, formative research, evaluation, or program implementation), were included. Some researchers published intervention protocol papers, and others discussed their activities in an evaluation or formative research paper. The purpose was not to focus on the type of report or manuscript but to understand the intervention discussed in the report. Reports in which an RFE intervention was not conducted were excluded. Reports targeting non-RFE settings, such as childcare facilities, schools, hospitals, and worksite cafeterias, were also excluded unless there was an explicit collaboration between these settings and retail food stores to implement intervention activities.

Study Selection

Covidence, a web-based platform, was used to manage the review.29 All identified records fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria were uploaded to Covidence. Two co-authors independently screened the title and abstract. Two co-authors who did not participate in the title and abstract screening resolved the conflicts. Additionally, 3 authors performed the full-text screening with a minimum of 2 authors screening each article independently, and any reason for excluding the article was recorded. All disagreements throughout the process were resolved, and a consensus was achieved through discussions.

Data Extraction

A template was created, tested, and uploaded to Covidence29 to extract all relevant information. Data extracted from each article included authors, intervention year, population of focus (race and ethnicity, income), intervention site (urban/rural/mixed), CE activities, and the focus of the intervention (affordability, availability, accessibility). When the intervention year was not available, the publication year was used as the intervention year. Extraction was divided between 6 reviewers, with each reviewer extracting all relevant information for their assigned report. Extracted data was then verified by a second reviewer. When there was more than 1 publication/report from the same intervention (eg, both a protocol and intervention evaluation), relevant extracted information was merged in the extraction form, with the more detailed information maintained.

Activities to engage communities were extracted, and the CDC continuum of community engagement framework was followed to classify the level of CE in RFE interventions.14 Category levels included outreach, consult/involve, collaborate, and shared ownership/decision making (Figure 2 for definitions). The review also evaluated whether the focus of the interventions addressed key equity domains of healthy eating in food retail. The selection of equity domains was guided by the Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention framework by Kumanyika23 and by key dimensions of an equitable regional food system identified by Mui and colleagues (2021).24 Domains included increased healthy food availability at existing locations (eg, adding produce or additional varieties of low-sodium canned vegetables at existing establishments, and so forth); increased healthy food availability by adding new sites; increased affordability of healthy food items (eg, reducing prices for healthy food through incentives or vouchers); and increased accessibility of healthy options at food retail sites (eg, mobile produce markets or providing transportation). Information was also extracted about whether the intervention was intended to address RFEs in a historically and intentionally excluded community (eg, conducted in neighborhoods with low healthy food access or in retail settings that accept food assistance benefits) or population (eg, low-income, rural, Indigenous, or communities of color). Data regarding geography was extracted based on the authors’ description of the intervention location (urban/rural/mixed/not specified); when it was not identified but the city or county name was provided, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service 2023 (ERS) Rural-Urban Continuum30 codes were followed. If no specific location was mentioned in the report, it was categorized as “not specified.” A quality appraisal of included reports was not performed, given that the focus of this review was to identify the different CE research approaches used in RFE interventions, as opposed to how well the intervention was designed to measure an effect.

Figure 2.

Description of categories in the continuum of community engagement.

Data Synthesis

Extracted data were synthesized in narrative and tabular form, guided by the research questions. To measure the extent of CE, each study was assessed for CE research activities that met the four CDC CE categories of outreach, consult/involve, collaborate, and shared ownership/decision making (Fig 2) and assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 4, respectively, when such activities were present. Two reviewers independently reviewed the scores and provided a consensus. To compare CE score across types of RFE settings, intervention phase (ie, the intervention phase communities were engaged), and intervention year, a mean score with minimum and maximum (min/max) for each setting, phase, and year was calculated. As a result, even a study with shared decision-making in a single intervention phase, such as planning, would have received a score of 4. RFE settings were defined as either corner stores, supermarkets, farmers markets, mobile markets, restaurants, others, or multiple if the intervention targeted more than 1 type of setting. The intervention design phase was categorized based on when CE activities occurred, including planning, implementation, evaluation, or any combination of phases. The 4 key equity domains for healthy food retail and population of focus were also evaluated across CE scores. Equity domains were examined individually as well as whether “All” or “>1 domain” were addressed in the RFE intervention.

RESULTS

The literature search resulted in 13 619 references. After removing 8980 duplicates, the title and abstract screening were conducted on 4639 records against the inclusion criteria. A total of 310 full-text reports were subsequently assessed for eligibility, and of these, 104 reports or articles were included in the review. There were 9810,31-127 unique RFE studies/interventions (Fig 3) evaluated for their CE research strategies, after combining reports (n = 6)128-133 on the same interventions (Fig 4). Going forward, the 98 unique studies will be referred to as interventions in this manuscript.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of 98 studies included in the scoping review on community engaged research strategies in food retail interventions.

Figure 4.

Flow diagram of the literature search and screening results for the scoping review of community engagement in retail food environment interventions.26 aReasons for exclusion at the title and abstract screening step were not recorded.

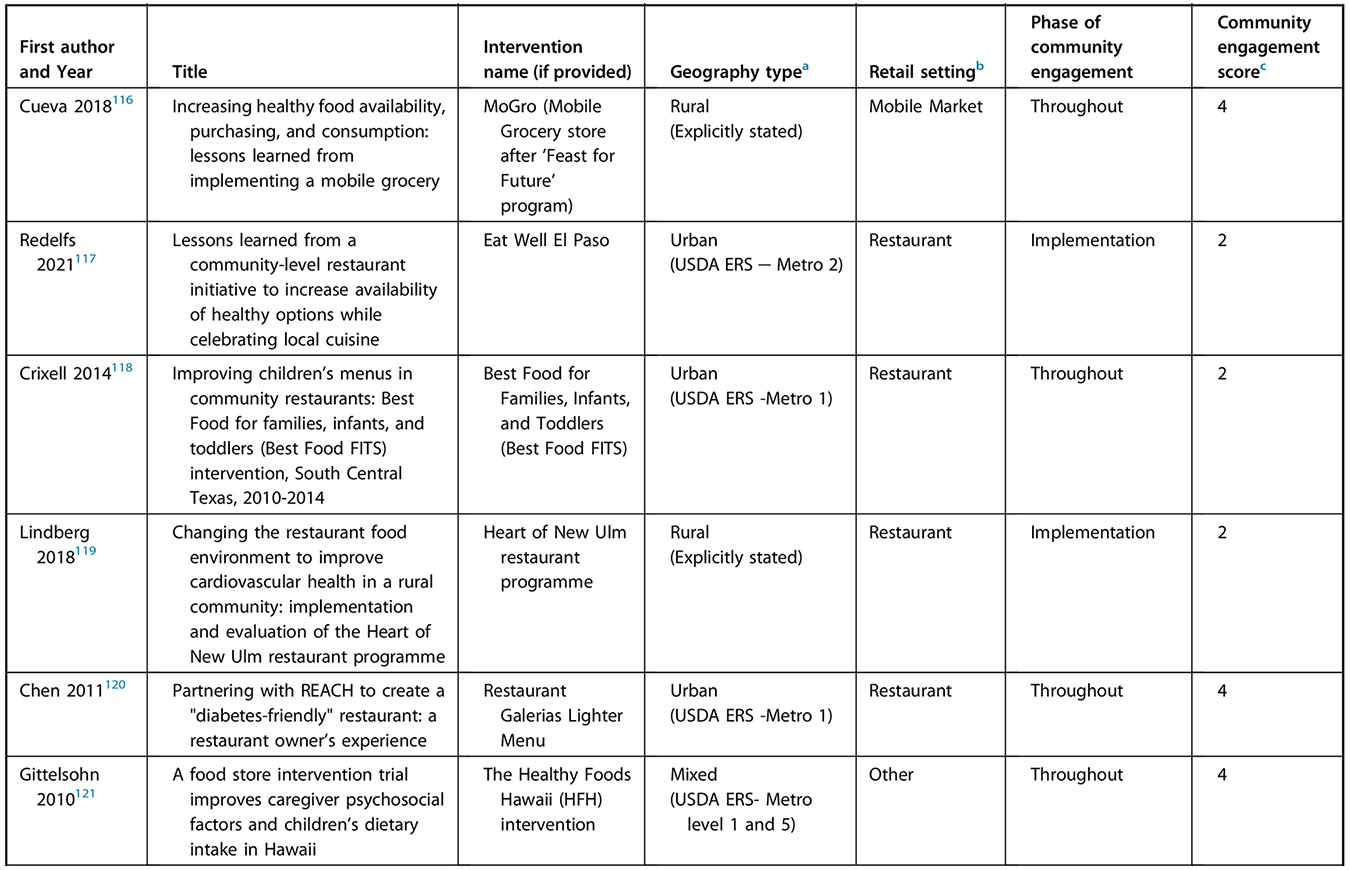

Description of Included Studies

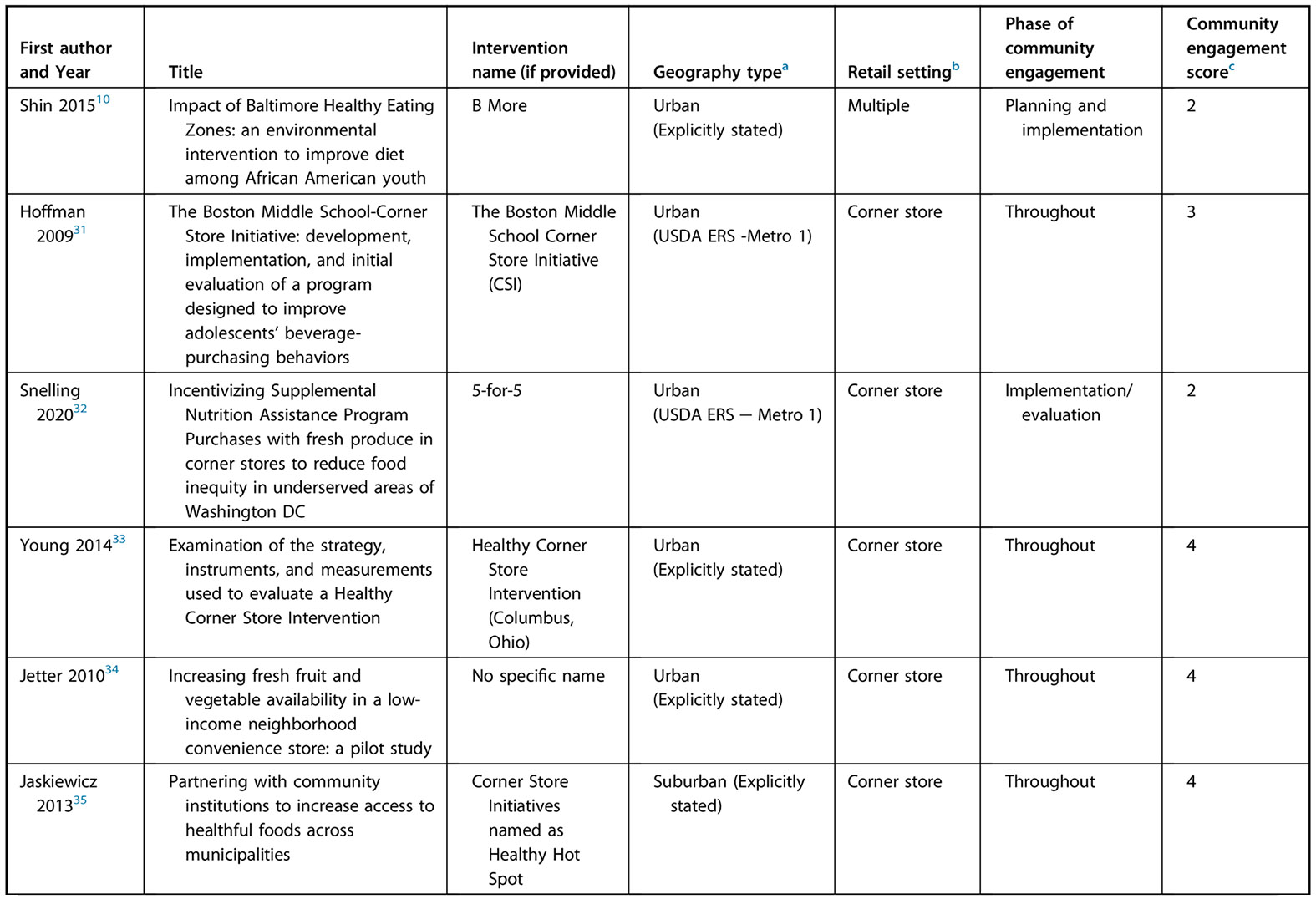

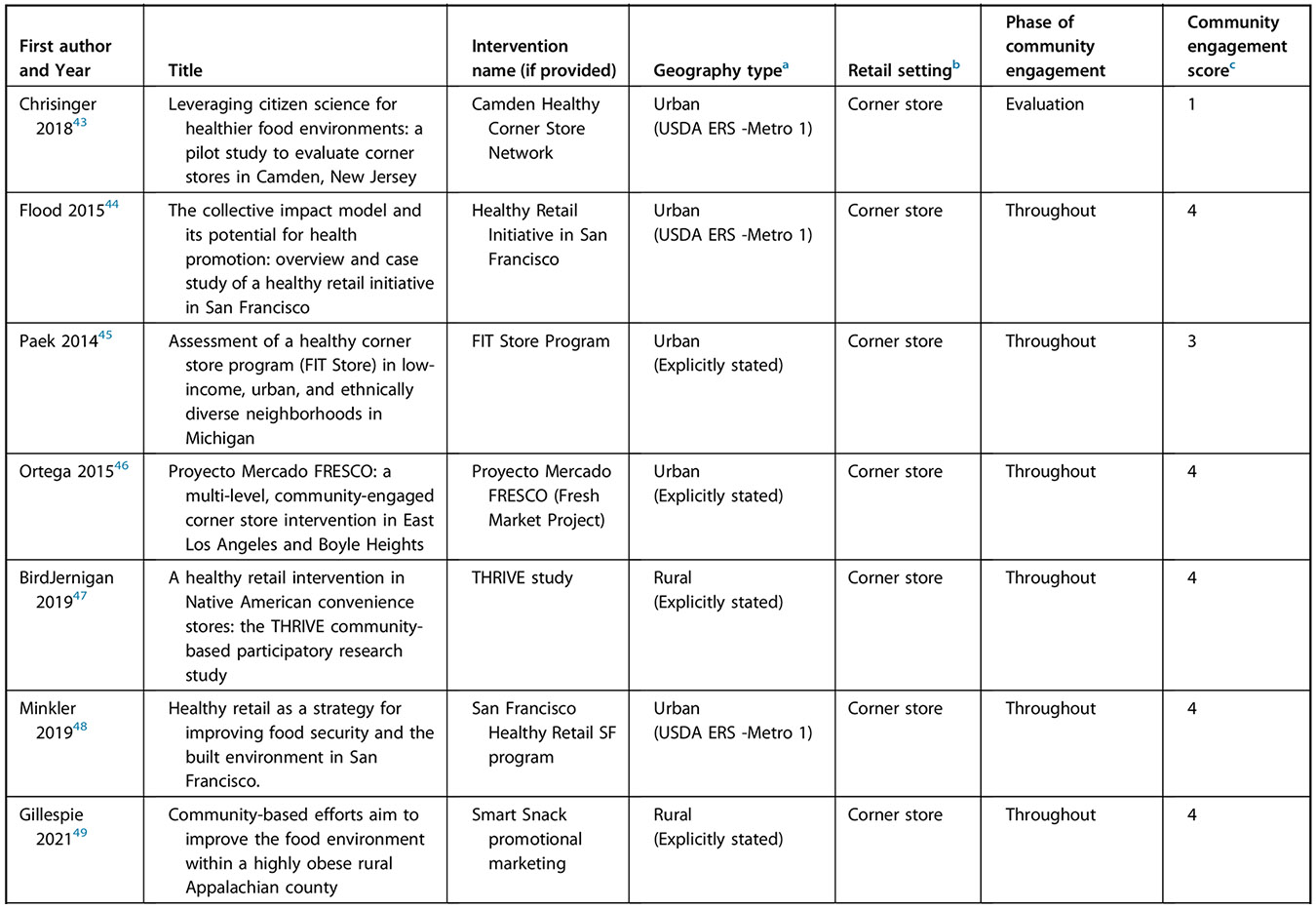

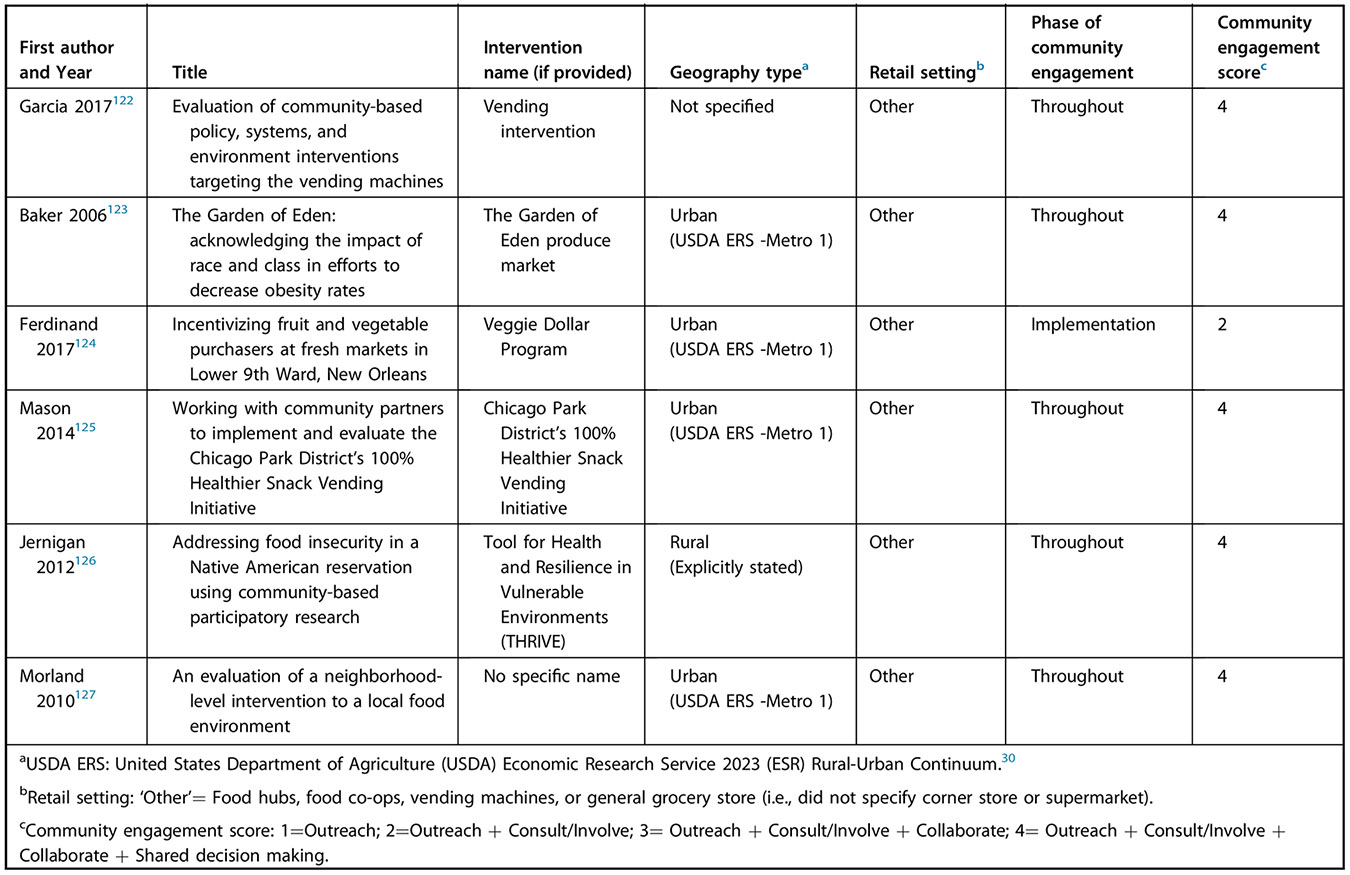

Most of the 98 interventions (Table 1) were conducted in corner stores (20%; n = 20),31-50 supermarkets (21%, n = 21),51-71 or multiple settings (21%, n = 21)10,72-91 such as different combinations of wholesalers, corner stores, community settings, carryout, worksites, and schools. The remaining interventions were conducted at farmers markets (15%, n = 15),92-106 mobile markets (10%, n = 10),107-116 restaurants (4%, n = 4),117-120 or another RFE setting (7%, n = 7), such as food hubs, food co-ops, vending machines, or general grocery store (ie, did not specify corner store or supermarket).121-127 Included interventions were conducted between 1989 and 2023, with nearly two-thirds (n = 62/98) conducted after 2010 (Table 1). Approximately 62% (n = 61)10,31-34,37-46,48,50,55-59,61-67,70-72,75,76,78,79,83,84,86,89,94-96,98,102,103,105,107-111,113,114,117,118,120,123-125,127 of interventions were conducted in urban settings, 22% (n = 22)47,49,51-54,60,73,74,77,85,87,90,91,97,101,104,106,112,116,119,126 in a “rural setting,” 8% (n = 7)36,69,82,88,92,93,121 “mixed,” 1% (n = 1)35 suburban, and 6% (n = 7)68,80,81,99,100,115,122 “did not specify” the geography type (Fig 3).

Table 1.

Community engagement (CE) variation across retail food environment setting, intervention phase, and intervention year among 98 studies included in the scoping review on community-engaged research strategies in food retail interventions

| N (98) | Mean CE score (min-max) |

CE Scorea % (n/N) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Retail food environment settings | ||||||

| Corner store | 2031-50 | 3.0 (1–4) | 20% (4/20) | 10% (2/20) | 25% (5/20) | 45% (9/20) |

| Farmers market | 1592-106 | 3.1 (1–4) | 7% (1/15) | 27% (4/15) | 13% (2/15) | 53% (8/15) |

| Mobile market | 10107-116 | 3.7 (3–4) | 0 | 0 | 30% (3/10) | 70% (7/10) |

| Multiple | 2110,72-91 | 3.6 (1–4) | 4% (1/21) | 10% (2/21) | 10% (2/21) | 76% (16/21) |

| Otherb | 7121-127 | 3.7 (2–4) | 0 | 14% (1/7) | 0 | 86% (6/7) |

| Restaurant | 4117-120 | 2.5 (2–4) | 0 | 75% (3/4) | 0 | 25% (1/4) |

| Supermarket | 2151-71 | 2.2 (1–4) | 33% (7/21) | 33% (7/21) | 10% (2/21) | 24% (5/21) |

| Intervention Phase of CE | ||||||

| Planning | 260,63 | 3.0 (2–4) | 0 | 50% (1/2) | 0 | 50% (1/2) |

| Planning and implementation | 510,42,55,62,110 | 2.8 (2–4) | 0 | 40% (2/5) | 40% (2/5) | 20% (1/5) |

| Implementation | 2337,39,41,54,57-59,61,65,67,68,70,78,82,86,91,92,106,108,113,117,119,124 | 2.0 (1–4) | 39% (9/23) | 35% (8/23) | 17% (4/23) | 9% (2/23) |

| Evaluation | 536,43,66,99,112 | 2.0 (1–3) | 40% (2/5) | 20% (1/5) | 40% (2/5) | 0 |

| Implementation and evaluation | 832,38,51,56,69,95,96,107 | 1.9 (1–4) | 25% (2/8) | 50% (4/8) | 12% (1/8) | 12% (1/8) |

| All phases | 5531,33-35,40,44-50,52,53,64,71-77,79-81,83-85,87-90,93,94,97,98,100-105,109,111,114-116,118,120-123,125-127 | 3.8 (2–4) | 0 | 6% (3/55) | 9% (5/55) | 85% (47/55) |

| Intervention Year | ||||||

| 1995 or earlier | 555,58,73,77,82 | 3.0 (1–4) | 20% (1/5) | 0 | 40% (2/5) | 40% (2/5) |

| 1996–2000 | 368,91,123 | 2.3 (1–4) | 33% (1/3) | 33% (1/3) | 0 | 33% (1/3) |

| 2001–2005 | 452,78,81,105 | 3.3 (1–4) | 25% (1/4) | 0 | 0 | 75% (3/4) |

| 2006–2010 | 2431,33,34,37-39,41,42,45,59,63-65,80,83,88,94-96,104,118,120,121,127 | 3.0 (1–4) | 17% (4/24) | 13% (3/24) | 21% (5/24) | 50% (12/24) |

| 2011–2015 | 3910,35,36,40,44,46,48,50,54,56,57,60-62,66,67,72,74,75,79,84,85,87,90,93,97,100,101,103,107,108,112-114,116,117,122,125,126 | 3.2 (1–4) | 5% (2/39) | 23% (9/39) | 18% (7/39) | 54% (21/39) |

| 2016–2020 | 2032,43,47,49,51,53,69,70,76,86,92,98,99,102,106,109,111,115,119,124 | 2.7 (1–4) | 20% (4/20) | 35% (7/20) | 5% (1/20) | 40% (8/20) |

| 2021 or later | 371,89,110 | 3.3 (2–4) | 0 | 33% (1/3) | 0 | 67% (2/3) |

Community engagement score: 1 = Outreach; 2 = Outreach + Consult/Involve; 3 = Outreach + Consult/Involve + Collaborate; 4 = Outreach + Consult/Involve + Collaborate + Shared decision-making.

Other’ = Food hubs, food co-ops, vending machines, or general grocery store (ie, did not specify corner store or supermarket).

RFE interventions included in this review focused on different historically and intentionally excluded populations. More than 90% of interventions (n = 89)10,32-54,56-67,69,71,72,74-85,87-90,92-117,119-121,123-127 explicitly focused on improving RFEs for low-income neighborhoods, communities of color, Indigenous populations, or areas with low access to grocery stores or healthy food. In the following section, the findings are summarized as (1) forms of CE, (2) variation in CE by type of RFE settings, intervention phase, and intervention year, and (3) equity considerations in RFE interventions by CE score.

Form of CE Research Activities in RFE Interventions

Following the CDC CE continuum framework,14 all included RFE interventions (n = 98)10,31-127 incorporated CE activities of outreach, 87% (n = 85)10,31-37,40,42,44-50,52-56,59,60,62-64,66,67,69,71-77,79-98,100-127 included activities of consultation or involvement, two-thirds included collaboration activities (n = 66),31,33-37,42,44-50,52-55,63,64,71-77,79-90,93,94,96,97,100-105,107-116,120-123,125-127 and approximately half demonstrated activities of shared decision-making and ownership (n = 52)33-35,44,46-50,52,54,63,64,71-73,75-77,79-81,83-90,93,94,100-105,107,109-111,114-116,120-123,125-127 (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Community engagement activities and level of involvement across retail food environment interventions among 98 studies included in the scoping review on community engaged research strategies in food retail interventions.

Outreach.

All interventions had some type of outreach, focusing on either store customers or the broader community to inform residents about the intervention. Thirteen interventions used only in store outreach activities to inform customers or store employees38,39,41,43,51,57,58,61,65,68,70,78,99 (Fig 5). The most common in-store outreach activities included store promotion of the intervention (eg, point of sale signs, shelf labels, or nutrition education messages) and incentives to purchase healthy food items. The remaining interventions (n = 85)10,31-37,40,42,44-50,52-56,59,60,62-64,66,67,69,71-77,79-98,100-127 had outreach activities to engage wider communities, which included sharing information through media, social media, newsletters, marketing or social marketing campaigns, and other promotional material for the study (eg, recipe card distribution, informational postcards at community sites, yard signs, and billboard signs) (Fig 5).

Consult/Involve.

Eighty-five10,31-37,40,42,44-50,52-56,59,60,62-64,66,67,69,71-77,79-98,100-127 interventions (87%) implemented CE research activities to consult or involve communities—where residents had the opportunity to provide feedback and the flow of information was bidirectional. Numerous strategies were used, including community group discussions, focus groups, interviews, listening sessions, feedback on intervention material, surveys, interactive education sessions, interactive demonstrations, taste tests in the community, formative research, and involving community residents through community organizations. For instance, Dannefer et al (2012)37 distributed consumer request cards among community organizations for residents to request specific healthy food to be carried in a store. Gans et al (2018)109 conducted focus groups and discussions with residents to inform intervention development in which residents provided their input regarding the location of the intervention, the content of promotional materials, the type of produce to be sold, and nutrition education topics.109

Collaboration.

Sixty-six interventions (67%)31,33-37,42,44-50,52-55,63,64,71-77,79-90,93,94,96,97,100-105,107-116,120-123,125-127 involved collaborative CE research activities with multilevel collaboration through different community organizations to build partnerships and trust in the community; however, the community’s role in final decision-making was not evident in the published description of the CE activities. Collaboration activities included building coalitions in the community, connecting farmers with retailers, having community members as advocates, and involving community organizations in intervention. For instance, Gittelsohn et al (2014)72 conducted an intervention called B’More Healthy Communities for Kids, which was a collaboration between wholesalers, recreation centers, corner stores, youth, and families. Youth delivered interactive nutrition sessions in the corner stores and were featured on program promotional materials.72 As another example, Baker et al (2006)123 involved the community through discussions around the intersections between faith and health and identified the need to create retail food infrastructure (eg, supermarket or community-run produce market) rather than just information on nutrition and physical activity to address obesity.

Shared Decision-Making/Shared Ownership.

At the highest level of community engagement, just over half of interventions (n = 52)33-35,44,46-50,52,54,63,64,71-73,75-77,79-81,83-90,93,94,100-105,107,109-111,114-116,120-123,125-127 included activities or strategies in which community residents, representatives, or community-based organizations were involved in a way that influenced decision-making regarding the intervention. Community residents engaged widely across interventions from youth, faith-based advocates, lay church members, business leaders, growers, grocers, academics, and community leaders, but all were part of the project decision-making. Some of the CE research activities included having community advisory boards, involving community residents as owners, store managers, or employees, and developing community advocacy groups to influence local RFE policy. For instance, Meister and Zapien (2005)81 trained members of community coalitions (also known as special action groups) to be policy advocates and develop a policy agenda for their communities. In this intervention, RFE was a part of the larger community initiative. Special action groups performed different activities, such as making presentations at the city council, participating in long-range planning committees, organizing an annual community forum, and cooking demonstrations at grocery stores to promote healthy food. As another example, Healthy Kids Healthy Communities was part of a national effort implementing policy, system, and environmental changes to address obesity.80 In this project, community residents from 49 cities across the United States were involved in assuming leadership roles and participating in the government decision-making process to promote the availability of affordable, healthy food at different venues, including RFE. In another study, called Tribal Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE), tribal leaders and local community residents played a critical role and participated in all aspects of intervention, from formative research to implementation in the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations. A partnership agreement was formed at the beginning of the intervention between academic researchers and tribal nations, and all aspects of the partnership were reviewed by tribal institutional review boards.47

Variation in CE by Type of RFE Setting, Intervention Phase, and Intervention Year

The CE score (range, 1–4) was used to compare the variation in the extent of CE research strategies across RFE setting, intervention phase, and year. Table 1 presents both the mean CE score (min/max) for each category and the proportion of studies across CE score. Exploring CE scores across RFE settings, the highest scores were observed for “mobile market” (mean = 3.7), “other” retail settings (mean = 3.7), and “multiple” settings (mean = 3.6). Settings with the lowest CE scores included supermarkets (mean = 2.2) and restaurants (mean = 2.5), with most interventions in these settings51,56-62,65-70,117-119 having a CE score of 2 or lower (supermarket = 14 of 21 studies; restaurants = 3 of 4 studies). These interventions were focused more on promotion of the intervention, affordability (incentive program), and the community role in program implementation and did not explicitly discuss community partnerships or their role in program decision-making. Although all settings had at least one example of an intervention incorporating shared leadership/ownership activities (ie, a CE score of 4), it was evident that interventions implemented in “mobile market,” “multiple,” and “other” settings were most consistently able to incorporate the highest levels of CE, as 70%,107,109-111,114-116 76%,72,73,75-77,79-81,83-90 and 86%121-123,125-127 of interventions, respectively, received a score of 4. Interventions in these diverse RFE settings used comprehensive approaches to make system-level changes, empower youth to be community advocates, promote nontraditional business models, and link farmers with traditional RFE; thus, they required community inclusiveness from multiple organizations and enabled shared decision-making in the process.

Examining the CE score by intervention phase (Table 1), the highest score occurred when communities were engaged throughout (mean = 3.8). A total of 5531,33-35,40,44-50,52,53,64,71-77,79-81,83-85,87-90,93,94,97,98,100-105,109,111,114-116,118,120-123,125-127, interventions integrated CE approaches throughout the process, with 85% (n = 47)33-35,44,46-50,52,64,71-73,75-77,79-81,83-85,87-90,93,94,100-105,109,111,115,116,120-123,125-127 demonstrating shared decision-making and ownership with the community. These interventions included CE activities in which community members, directly or through stakeholders representing community members, had the opportunity to take a lead in the project and guide the program design, implementation, and evaluation. In comparison, lower scores for CE were observed when communities were involved only in the implementation (mean = 2), evaluation (mean = 2), or both phases (mean = 1.9). Across these 36 interventions,32,36-39,41,43,51,54,56-59,61,65-70,78,82,86,91,92,95,96,99,106-108,112,113,117,119,124 communities were involved more to execute rather than decide program activities. Finally, examining CE activities across intervention years, there were no clear changes over time, with a persistent proportion of studies only implementing CE activities of outreach and consult/involve.

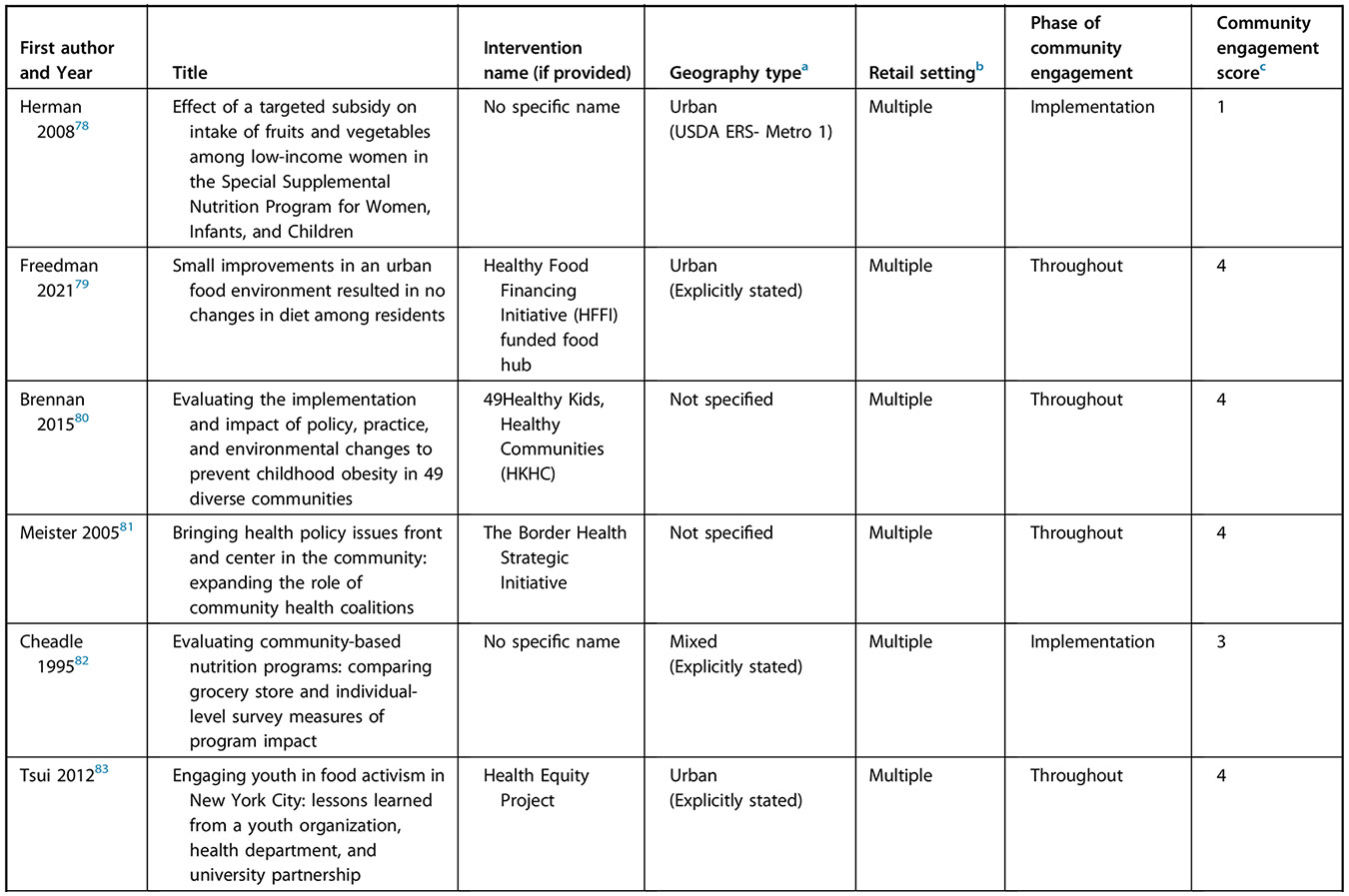

Considerations of Equity in the RFE Intervention

This review also examined whether interventions demonstrated various considerations for equity and how these varied across CE score (Table 2). Equity domains that were assessed included whether the RFE intervention involved trying to (1) increase the availability of healthy food at an existing store, (2) increase the availability of healthy food by introducing a new site, (3) increase the affordability of healthy food through financial support such as coupons, or (4) increase the accessibility of healthy food. Overall, interventions demonstrated a strong commitment to improving RFEs for historically and intentionally excluded communities, as 91% (n = 89) 10,32-54,56-67,69,71,72,74-85,87-90,92-117,119-121,123-127 of interventions had this explicit focus. Across the 4 domains of equity, interventions overall had a greater focus on increasing availability of healthy food at existing sites (74%)10,31-62,65,67-70,72-74,76-88,90-92,95,97-99,104,117-122,124-127 and improving its affordability (56%)32,33,35,37,38,40,43,44,46,48,53,56,59,61,64-69,71,76,78,79,86,87,92-111,113-116,119,123,124,126,127 rather than adding new community locations of stores selling healthy food (32%)48,63,64,66,71,75,76,79,87,93,94,96,100-105,107-116,123,126,127 or addressing concerns of healthy food accessibility (31%),48,50,64,66,67,76,87,93,94,96-98,100-105,107-116,123,125 such as improving transportation. Examining these domains across CE scores, it was observed that as CE research activities improved (ie, CE scores increased), interventions displayed a greater focus on addressing accessibility and making new sites available. In addition, although most interventions considered more than 1 equity domain (58%),32,33,35,37,38,40,43,44,46,48,50,53,56,59,61,64-69,71,76,78,79,86,87,92-105,107-116,119,123-127 only interventions that incorporated communities in shared decision-making and ownership addressed all 4 domains. One consistent way researchers involved communities in shared decision-making was by developing or engaging with an existing local food policy council (or board), which occurred in 276,104 of the 4 interventions48,76,87,104 that addressed all equity domains. For instance, Janda et al (2021)76 discussed working with the County Food Policy Board to promote geographic and economic access to healthy food through farm stands, mobile markets, corner stores, and subsidized prices.76

Table 2.

Equity considerations in interventions by community engagement (CE) score among 98 studies included in the scoping review on community-engaged research strategies in food retail interventions

| Score of CEb | Domains of Equitya | Historically and intentionally excluded communities considerations |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed availability of healthy food at existing sites |

Addressed availability of healthy food by adding new site |

Addressed affordability of healthy food |

Addressed accessibility of healthy food |

>1 domain of access considered |

All 4 domains considered |

||

| Overall (N=98) | 74% (72/98) | 32% (31/98) | 56% (55/98) | 31% (30/98) | 58% (57/98) | 4% (4/98) | 91% (89/98) |

| 1 (N=13) 38,39,41,43,51,57,58,61,65,68,70,78,99 | 100% (13/13) | 0 | 54% (7/13) | 0 | 54% (7/13) | 0 | 85% (11/13) |

| 2 (N=19) 10,32,40,56,59,60,62,66,67,69,91,92,95,98,106,117-119,124 | 90% (17/19) | 5% (1/19) | 68% (13/19) | 16% (3/19) | 63% (12/19) | 0 | 89% (17/19) |

| 3 (N=14) 31,36,37,42,45,53,55,74,82,96,97,108,112,113 | 71% (10/14) | 29% (4/14) | 43% (6/14) | 36% (5/14) | 50% (7/14) | 0 | 86% (12/14) |

| 4 (N=52) 33-35,44,46-50,52,54,63,64,71-73,75-77,79-81,83-90,93,94,100-105,107,109-111,114-116,120-123,125-127 | 62% (32/52) | 50% (26/52) | 56% (29/52) | 42% (22/52) | 60% (31/52) | 8% (4/52) | 94% (49/52) |

Equity domains were informed by Kumanyika’s ‘Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention’ framework23 and key dimensions of an equitable regional food system identified by Mui and colleagues (2021).24

Community Engagement Score: 1=Outreach; 2=Outreach + Consult/Involve; 3= Outreach + Consult/Involve + Collaborate; 4= Outreach + Consult/Involve + Collaborate + Shared decision making.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review examined the breadth and extent of CE in RFE interventions by exploring the range of strategies employed and how these varied across RFE settings, intervention phase, intervention year, and key equity domains for healthy food retail. The findings revealed that CE research strategies of outreach were used across all RFE interventions, whereas enabling communities to participate in decision-making (ie, the highest level of CE) occurred in only half. In addition, the strength of CE varied across RFE settings, intervention phase, and domains of equity. Interventions conducted in diverse RFE settings, such as “mobile markets,” “multiple,” and “other,” and interventions involving communities throughout the intervention design (ie, from design through evaluation) had the highest level of CE (ie, shared decision-making) based on CE activities described. Similarly, interventions addressing all 4 domains of equity were also those that employed the highest forms of CE. Surprisingly, there was very little change in the strength of CE research strategies used in RFE interventions over time.

The review also found that the phase and purpose of employing CE are critical regardless of the RFE setting. Any intervention (1) recognizing the importance of community ownership, (2) involving the community throughout the process from understanding their needs to program implementation, and (3) implementing comprehensive strategies rather than solely focusing on store promotion demonstrated the highest forms of CE. Such examples demonstrate that considering RFE as a part of a system (Policy, Systems, and Environmental [PSE] model-based interventions) rather than as a stand-alone determinant and ensuring community residents have the ability to influence decisions may be an important strategy for researchers to explore to develop more effective RFE interventions. These findings are consistent with the literature highlighting the importance of PSE change strategies to address complex health behaviors and to have a sustainable impact.134 PSE demands collaboration across sectors that are complex and labor-intensive.135 Partners might have variations of invested interests, and forming a common goal is critical. Once the partnership is established, researchers have emphasized additional challenges such as maintaining a partnership, shared roles and governance, transparency, and accountability.136 Such challenges may be especially salient when researchers work in the RFE, where it can be difficult to navigate the interests and desires of the retail partner with goals to engage community members authentically. Yet, even though some RFE settings appear to be more amenable to using stronger forms of CE research strategies than others, findings of this review also suggest that a significant portion of RFE interventions in the United States have been engaging in this important work and have been able to do so across all settings. Thus, even though supermarket- and restaurant-focused RFEs had lower CE scores on average, some intervention studies were still able to have high CE scores in these settings.52,54,63,64,71,120

Evaluating equity considerations, it was found that nearly all RFE interventions (91%), regardless of the degree of CE employed, explicitly focused on historically and intentionally excluded communities. However, the extent to which the domains of equity (availability at existing site, availability at new site, accessibility, and affordability) were addressed did vary by CE, with only those interventions using the highest forms of CE able to address all 4 domains. This suggests that although CE can take additional time and effort, and inherently, some nontraditional retail settings may be better partners for this work than others, greater CE can result in more comprehensive and equitable solutions for addressing RFEs. Moreover, it aligns with the principles of the Strategies to Repair Equity and Transform Community Health Initiative (STRETCH) framework that centers on system change to achieve health equity and support power-sharing in community partnerships through community-led approaches.137

Despite evidence that greater forms of CE are linked with greater attention to equity, this review also found that there has been little to no improvement in researchers implementing the highest levels of CE—shared decision-making and ownership—across RFE interventions over time. The importance of incorporating CE in interventions and working at more authentic levels that share power has gained increasing attention in public health after the launch of the first CBPR-focused research initiative at the National Institute of Health in 1995.138 This led us to believe that more RFE interventions would incorporate these strategies over time. However, this review found that the proportion of studies using this level of CE remained stagnant at approximately half. The idea of shared power in public health interventions is also being promoted under the term co-creation.139 However, Morales-Garzón et al (2023)140 found in their scoping review that studies discussing the “co-creation” methodology in equity-focused public health actions have a lack of community involvement in decision-making.140 The recommendations for researchers, organizations, funders, and systems to make CE a requirement for prevention programs are consistent across different health domains.141-143 Together, this suggests that more efforts are needed to deepen the knowledge and implementation of CE research strategies to attain shared ownership in public health interventions, including those within the RFE.

Strengths and Limitations

This review has several strengths and limitations. A key strength was using a broader definition of RFE that allowed authors to include less traditional retail settings, such as mobile markets, farmers markets, and vending machines, and compare the CE of these settings with traditional settings, such as supermarkets and grocery stores. In addition, this review performed an extensive database search led by a librarian and implemented the JBI25 and PRISMA-ScR26 guidelines to select studies and extract data. In terms of limitations, the authors did not include dissertation/thesis, gray, and non-peer-reviewed literature, which may have failed to provide a full synthesis of CE research strategies used in US RFE intervention research to date. Second, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were designed to review only RFE interventions in the United States, given the unique US context around historical and present-day racism and economic inequality, which continue to limit access to healthy food.27 Future reviews should consider examining CE research approaches across a wider range of countries and assess how these compare with the US-based results. Furthermore, examining regional differences within countries, such as rural vs urban, could be useful. Finally, some interventions may have had limited details about CE activities implemented, and even with our rigorous database search, additional publications with relevant CE information about an intervention may have been inadvertently missed. Because CE research strategies could only be assessed based on activities discussed in the published articles identified, in which authors are often forced to make difficult choices about what study details to include because of limited journal word counts, this may have resulted in some inaccurate CE scores. Furthermore, information on who from the community was engaged—members that could directly benefit from the intervention or a leader representing community interests—could not be extracted because that detail was typically not apparent in publications. Together, this implies that there may be a need for both dissemination standards to ensure CE research strategies are adequately described in future intervention publications144 and a shift in journal priorities toward publishing more CE-focused method papers.

CONCLUSION

Effective CE in RFE interventions is challenging but crucial. Documenting how and to what extent CE research strategies occurred is important to further understand what research gaps remain and explore the ways CE strategies could be leveraged for a more equitable intervention design. The findings of this review highlight that public health researchers who collaborated with communities throughout all phases of the project and aimed to address multiple domains of equity related to food retail were most likely to employ the highest levels of CE (ie, shared decision-making). As such, future RFE intervention research should assess whether shared leadership CE strategies—which strive to ensure community voice is incorporated in all decisions—are a more effective approach than other CE approaches in narrowing nutrition-related health equity outcomes for communities. Moreover, the limited information about CE research strategies described in some publications suggests that standardized dissemination procedures for intervention protocols could be beneficial to ensure a more complete and accurate understanding of the CE research activities employed.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1 is available at www.jandonline.org

Figure 1.

Search strategy and databases used in a scoping review of community-engaged research strategies in retail food environment interventions.

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Question:

What are the community engagement (CE) research strategies used in retail food environment (RFE) interventions, and do they vary by type of retail settings, phase of intervention, year of intervention, and key domains of equity?

Key Findings:

Across the 98 included RFE interventions, all forms of CE research strategies, including outreach, consult/involve, collaboration, and shared leadership, were identified, with outreach used in all interventions and shared leadership in half. The form of CE research strategy varied across intervention characteristics (eg, intervention phase), and interventions using stronger CE forms also addressed more domains of equity.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This project was supported by Healthy Eating Research (HER), a national program under the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Support was also provided to Winkler under grant number R00HL144824 (PI: M. Winkler) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of HER and the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319:1444–1472. 10.1001/jama.2018.0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hruby A, Manson JE, Qi L, et al. Determinants and consequences of obesity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1656–1662. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):790–797. 10.1056/NEJMoa010492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satia JA. Diet-related disparities: understanding the problem and accelerating solutions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(4):610–615. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107–1117. 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy food environments. Published online 2022. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/healthy-food-environments/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fhealthyplaces%2Fhealthtopics%2Fhealthyfood%2Fgeneral.htm

- 7.Winkler MR, Mui Y, Hunt SL, Laska MN, Gittelsohn J, Tracy M. Applications of complex systems models to improve retail food environments for population health: a scoping review. Adv Nutr. 2022;13(4):1028–1043. 10.1093/advances/nmab138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vonthron S, Perrin C, Soulard CT. Foodscape: a scoping review and a research agenda for food security-related studies. PLOS One. 2020;15(5):e0233218. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez-Donate AP, Riggall AJ, Meinen AM, et al. Evaluation of a pilot healthy eating intervention in restaurants and food stores of a rural community: a randomized community trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:136. 10.1186/s12889-015-1469-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin A, Surkan PJ, Coutinho AJ, et al. Impact of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: an environmental intervention to improve diet among African American youth. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(1 Suppl):97S–105S. 10.1177/1090198115571362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gittelsohn J, Dyckman W, Frick KD, et al. A pilot food store intervention in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Pac Health Dialog. 2007;14(2):43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gittelsohn J, Franceschini MCT, Rasooly IR, et al. Understanding the food environment in a low-income urban setting: implications for food store interventions. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2008;2(2-3):33–50. 10.1080/19320240801891438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):129. 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of Community Engagement. 1st ed. Published June 2011. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11699

- 15.Berge JM, Mendenhall TJ, Doherty WJ. Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) to target health disparities in families. Fam Relat. 2009;58(4):475–488. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00567.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodríguez ST, Tajo M, Washington S, Burrowes K. Changing Power Dynamics among Researchers, Local Governments, and Community Members. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/changing-power-dynamics-among-researchers-local-governments-and-community [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur R, Winkler MR, John S, et al. Forms of community engagement in neighborhood food retail: healthy community stores case study project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):6986. 10.3390/ijerph19126986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mah CL, Luongo G, Hasdell R, Taylor NGA, Lo BK. A systematic review of the effect of retail food environment interventions on diet and health with a focus on the enabling role of public policies. Curr Nutr Rep. 2019;8(4):411–428. 10.1007/s13668-019-00295-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luongo G, Skinner K, Phillipps B, Yu Z, Martin D, Mah CL. The retail food environment, store foods, and diet and health among indigenous populations: a scoping review. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(3):288–306. 10.1007/s13679-020-00399-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner G, Green R, Alae-Carew C, Dangour AD. The association of dimensions of fruit and vegetable access in the retail food environment with consumption: a systematic review. Glob Food Secur. 2021;29:100528. 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams J, Scarborough P, Matthews A, et al. A systematic review of the influence of the retail food environment around schools on obesity-related outcomes. Obes Rev. 2014;15(5):359–374. 10.1111/obr.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Brock J, Christian M, Allender S. Co-creation of healthier food retail environments: a systematic review to explore the type of stakeholders and their motivations and stage of engagement. Obes Rev. 2022;23(9):e13482. 10.1111/obr.13482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumanyika SK. A Framework for Increasing Equity Impact in Obesity Prevention. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1350–1357. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mui Y, Khojasteh M, Judelsohn A, et al. Planning for regional food equity. J Am Plann Assoc. 2021;87(3):354–369. 10.1080/01944363.2020.1845781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Accessed October 10, 2022. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaker Y, Grineski SE, Collins TW, Flores AB. Redlining, racism and food access in US urban cores. Agric Hum Values. 2023;40(1):101–112. 10.1007/s10460-022-10340-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CFR—Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 2023. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=1.327&SearchTerm=restaurant

- 29.Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Accessed December 12, 2022. Available at www.covidence.org

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Published online 2024. Accessed May 16, 2023. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/

- 31.Hoffman JA, Morris V, Cook J. The Boston middle school-corner store initiative: development, implementation, and initial evaluation of a program designed to improve adolescents’ beverage-purchasing behaviors. Psychol Sch. 2009;46(8):756–766. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snelling AM, Yamamoto JJ, Belazis LB, Seltzer GR, McClave RL, Watts E. Incentivizing supplemental nutrition assistance program purchases with fresh produce in corner stores to reduce food inequity in underserved areas of Washington DC. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young KA, Clark JK. Examination of the strategy, instruments, and measurements used to evaluate a healthy corner store intervention. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2014;9(4):449–470. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jetter KM, Cassady DL. Increasing fresh fruit and vegetable availability in a low-income neighborhood convenience store: a pilot study. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(5):694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaskiewicz L, Dombrowski RD, Drummond HM, Barnett GM, Mason M, Welter C. Partnering with community institutions to increase access to healthful foods across municipalities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E167–E167. 10.5888/pcd10.130011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitts SBJ, Bringolf KR, Lloyd CL, McGuirt JT, Lawton KK, Morgan J. Formative evaluation for a healthy corner store initiative in Pitt County, North Carolina: engaging stakeholders for a healthy corner store initiative, part 2. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E120–E120. 10.5888/pcd10.120319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dannefer R, Williams DA, Baronberg S, Silver L. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e27–e31. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith TM, Schram S, Tibbits M, Wang H, Balluff M. Healthy neighborhood stores: key recommendations for working with owners of small stores in communities of high need. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):395–398. 10.1016/j.jand.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleich SN, Herring BJ, Flagg DD, Gary-Webb TL. Reduction in purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages among low-income black adolescents after exposure to caloric information. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):329–335. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robles B, Barragan N, Smith B, Caldwell J, Shah D, Kuo T. Lessons learned from implementing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education Small Corner Store Project in Los Angeles County. Prev Med Rep. 2019;16:100997. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freedman MR, Connors R. Point-of-purchase nutrition information influences food-purchasing behaviors of college students: a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(8):1222–1226. 10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson C, Haushalter A, Buck T, Campbell D, Henderson T, Schlundt D. Development of a community-sensitive strategy to increase availability of fresh fruits and vegetables in Nashville’s urban food deserts, 2010-2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E125. 10.5888/pcd10.130008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chrisinger BW, Ramos A, Shaykis F, et al. Leveraging citizen science for healthier food environments: a pilot study to evaluate corner stores in Camden, New Jersey. Front Public Health. 2018;6:89. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flood J, Minkler M, Hennessey Lavery S, Estrada J, Falbe J. The collective impact model and its potential for health promotion: overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):654–668. 10.1177/1090198115577372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paek HJ, Oh HJ, Jung Y, et al. Assessment of a healthy corner store program (FIT Store) in low-income, urban, and ethnically diverse neighborhoods in Michigan. Fam Community Health. 2014;37(1):86–99. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortega AN, Albert SL, Sharif MZ, et al. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: a multi-level, community-engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. J Community Health. 2015;40(2):347–356. 10.1007/s10900-014-9941-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bird Jernigan VB, Salvatore AL, Williams M, et al. A healthy retail intervention in Native American convenience stores: the THRIVE Community-Based Participatory Research Study. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):132–139. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minkler M, Estrada J, Dyer S, Hennessey-Lavery S, Wakimoto P, Falbe J. Healthy retail as a strategy for improving food security and the built environment in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S2):S137–S140. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillespie R, DeWitt E, Norman-Burgdolf H, Dunnaway B, Gustafson A. Community-based efforts aim to improve the food environment within a highly obese rural Appalachian County. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2200. 10.3390/nu13072200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rollins L, Carey T, Proeller A, et al. Community-based participatory approach to increase African Americans’ access to healthy foods in Atlanta, GA. J Community Health. 2021;46(1):41–50. 10.1007/s10900-020-00840-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gustafson CR, Kent R, Prate MR Jr. Retail-based healthy food point-of-decision prompts (PDPs) increase healthy food choices in a rural, low-income, minority community. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hultine SA, Cooperband LR, Curry MP, Gasteyer S. Linking small farms to rural communities with local food: a case study of the local food project in Fairbury, Illinois. Community Dev J Community Dev Soc. 2007;38(3):61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gustafson A, Ng SW, Pitts SJ. The association between the “Plate It Up Kentucky” supermarket intervention and changes in grocery shopping practices among rural residents. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(5):865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCool BN, Lyford CP, Hensarling N, et al. Reducing cancer risk in rural communities through supermarket interventions. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(3):597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Light L, Tenney J, Portnoy B, et al. Eat for health: a nutrition and cancer control supermarket intervention. Public Health Rep. 1989;104(5):443–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Surkan PJ, Tabrizi MJ, Lee RM, Palmer AM, Frick KD. Eat right–live well! supermarket intervention impact on sales of healthy foods in a low-income neighborhood. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(2):112–121.e1. 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adjoian T, Dannefer R, Willingham C, Brathwaite C, Franklin S. Healthy checkout lines: a study in urban supermarkets. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):615–622.e1. 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lang JE, Mercer N, Tran D, Mosca L. Use of a supermarket shelf-labeling program to educate a predominantly minority community about foods that promote heart health. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(7):804–809. 10.1016/s0002-8223(00)00234-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gittelsohn J, Song H, Suratkar S, et al. An urban food store intervention positively affects food-related psychosocial variables and food behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(3):390–402. 10.1177/1090198109343886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gustafson CR, Prate MR. Healthy food labels tailored to a high-risk, minority population more effectively promote healthy choices than generic labels. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2272–2272. 10.3390/nu11102272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnston YA, McFadden M, Lamphere M, Buch K, Stark B, Salton JL. Working with grocers to reduce dietary sodium: lessons learned from the Broome County Sodium Reduction in Communities pilot project. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20:S54–S58. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a0b91a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foster GD, Karpyn A, Wojtanowski AC, et al. Placement and promotion strategies to increase sales of healthier products in supermarkets in low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1359–1368. 10.3945/ajcn.113.075572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cummins S, Flint E, Matthews SA. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):283–291. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lagisetty P, Flamm L, Rak S, Landgraf J, Heisler M, Forman J. A multistakeholder evaluation of the Baltimore City virtual supermarket program. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–9. 10.1186/s12889-017-4864-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Stites SD, et al. Impact of a rewards-based incentive program on promoting fruit and vegetable purchases. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):166–172. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yao M, Hillier A, Wall E, DiSantis KI. The impact of a non-profit market on food store choice and shopping experience: a community case study. Front Public Health. 2019;7:78. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller ER 3rd, Cooper LA, Carson KA, et al. A dietary intervention in urban African Americans: results of the “Five Plus Nuts and Beans” randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):87–95. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paine-Andrews A, Francisco VT, Fawcett SB, Johnston J, Coen S. Health marketing in the supermarket: using prompting, product sampling, and price reduction to increase customer purchases of lower-fat items. Health Mark Q. 1996;14(2):85–99. 10.1300/j026v14n02_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marcinkevage J, Auvinen A, Nambuthiri S. Washington State’s Fruit and Vegetable Prescription program: improving affordability of healthy foods for low-income patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E91. 10.5888/pcd16.180617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steen DL, Helsley RN, Bhatt DL, et al. Efficacy of supermarket and web-based interventions for improving dietary quality: a randomized, controlled trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(12):2530–2536. 10.1038/s41591-022-02077-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneider K, Castellanos DC, Felix F, Holcomb JA. Measuring the impact of a full service grocery store in a food desert. Int J Community Soc Dev. 2021;3(2):161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gittelsohn J, Anderson Steeves E, Mui Y, Kharmats AY, Hopkins LC, Dennis D. B’More healthy communities for kids: design of a multilevel intervention for obesity prevention for low-income African American children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14. n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Potter JD, Graves KL, Finnegan JR, et al. The Cancer and Diet Intervention Project: a community-based intervention to reduce nutrition-related risk of cancer. Health Educ Res. 1990;5(4):489–503. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Escaron AL, Martinez-Donate AP, Riggall AJ, et al. Developing and implementing “Waupaca Eating Smart”: a restaurant and supermarket intervention to promote healthy eating through changes in the food environment. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(2):265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Payán DD, Lewis LB, Illum J, Hawkins B, Sloane DC. United for health to improve urban food environments across five underserved communities: a cross-sector coalition approach. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Janda KM, Ranjit Nalini, Salvo D, et al. A multi-pronged evaluation of a healthy food access initiative in central Texas: study design, methods, and baseline findings of the FRESH-Austin evaluation study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Demark-Wahnefried W, Hoben KP, Hars V, Jennings J, Miller MW, Mcclelland JW. Utility of produce ratios to track fruit and vegetable consumption in a rural community, church-based 5 A Day intervention project. Nutr Cancer. 1999;33(2):213–213. 10.1207/s15327914nc330215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi AA, Jenks E. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):98–105. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Freedman DA, Bell BA, Clark J, et al. Small improvements in an urban food environment resulted in no changes in diet among residents. J Community Health. 2021;46(1):1–12. 10.1007/s10900-020-00805-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brennan LK, Kemner AL, Donaldson K, Brownson RC. Evaluating the implementation and impact of policy, practice, and environmental changes to prevent childhood obesity in 49 diverse communities. J Public Health Manag Pr. 2015;21(Suppl 3):S121–S134. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meister JS, Guernsey de Zapien J. Bringing health policy issues front and center in the community: expanding the role of community health coalitions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Diehr P, et al. Evaluating community-based nutrition programs: comparing grocery store and individual-level survey measures of program impact. Prev Med. 1995;24(1):71–79. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsui E, Bylander K, Cho M, Maybank A, Freudenberg N. Engaging youth in food activism in New York City: lessons learned from a youth organization, health department, and university partnership. J Urban Health. 2012;89(5):809–827. 10.1007/s11524-012-9684-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gudzune KA, Welsh C, Lane E, Chissell Z, Anderson Steeves E, Gittelsohn J. Increasing access to fresh produce by pairing urban farms with corner stores: a case study in a low-income urban setting. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2770–2774. 10.1017/S1368980015000051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cruz TH, Davis SM, FitzGerald CA, Canaca GF, Keane PC. Engagement, recruitment, and retention in a trans-community, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in rural American Indian and Hispanic children. J Prim Prev. 2014;35(3):135–149. 10.1007/s10935-014-0340-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gore R, Patel S, Choy C, et al. Influence of organizational and social contexts on the implementation of culturally adapted hypertension control programs in Asian American-serving grocery stores, restaurants, and faith-based community sites: a qualitative study. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(6):1525–1537. 10.1093/tbm/ibz106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sundberg MA, Warren AC, VanWassenhove-Paetzold J, et al. Implementation of the Navajo fruit and vegetable prescription programme to improve access to healthy foods in a rural food desert. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(12):2199–2210. 10.1017/S1368980019005068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fleischhacker S, Byrd RR, Ramachandran G, et al. Tools for healthy tribes: improving access to healthy foods in Indian country. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3 Suppl 2):S123–S129. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gangrade N, Botchwey N, Leak TM. Examining the feasibility of a youth advocacy program promoting healthy snacking in New York City: a mixed-methods process evaluation. Health Educ Res. 2023;38(4):306–319. 10.1093/her/cyad019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meendering JR, McCormack L, Moore L, Stluka S. Facilitating nutrition and physical activity-focused policy, systems, and environmental change in rural areas: a methodological approach using community wellness coalitions and cooperative extension. Health Promot Pract. 2023;24:68S–79S. 10.1177/15248399221144976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Booth-Butterfield S, Reger B. The message changes belief and the rest is theory: the “1% or less” milk campaign and reasoned action. Prev Med Int J Devoted Pract Theory. 2004;39(3):581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hecht AA, Misiaszek C, Headrick G, Brosius S, Crone A, Surkan PJ. Manager perspectives on implementation of a farmers’ market incentive program in Maryland. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(8):926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hossfeld L, Kelly EB, O’Donnell E, Waity J. Food sovereignty, food access, and the local food movement in southeastern North Carolina. Humanity Soc. 2017;41(4):446. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Freedman DA, Bell BA, Collins LV. The Veggie Project: a case study of a multi-component farmers’ market intervention. J Prim Prev. 2011;32(3-4):213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lindsay S, Lambert J, Penn T, et al. Monetary matched incentives to encourage the purchase of fresh fruits and vegetables at farmers markets in underserved communities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E188–E188. 10.5888/pcd10.130124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Evans AE, Jennings R, Smiley AW, et al. Introduction of farm stands in low-income communities increases fruit and vegetable among community residents. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1137–1143. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.DeWitt E, McGladrey M, Liu E, et al. A community-based marketing campaign at farmers markets to encourage fruit and vegetable purchases in rural counties with high rates of obesity, Kentucky, 2015-2016. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E72. 10.5888/pcd14.170010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Slagel N, Newman T, Sanville L, et al. A pilot fruit and vegetable prescription (FVRx) program improves local fruit and vegetable consumption, nutrition knowledge, and food purchasing practices. Health Promot Pr. 2023;24(1):62–69. 10.1177/15248399211018169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Savoie Roskos MR, Wengreen H, Gast J, LeBlanc H, Durward C. Understanding the experiences of low-income individuals receiving farmers’ market incentives in the United States: a qualitative study. Health Promot Pr. 2017;18(6):869–878. 10.1177/1524839917715438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kwon SC, Rideout C, Patel S, et al. Improving access to healthy foods for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders: lessons learned from the STRIVE Program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(2 Suppl):116–136. 10.1353/hpu.2015.0063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alia KA, Freedman DA, Brandt HM, Gibson-Haigler P, Friedman DB. A participatory model for evaluating a multilevel farmers’ market intervention. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(4):537–548. 10.1353/cpr.2015.0074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ball L, McCauley A, Paul T, Gruber K, Haldeman L, Dharod J. Evaluating the implementation of a farmers’ market targeting WIC FMNP participants. Health Promot Pr. 2018;19(6):946–956. 10.1177/1524839917743965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Woodruff RC, Coleman AM, Hermstad AK, et al. Increasing community access to fresh fruits and vegetables: a case study of the Farm Fresh Market Pilot Program in Cobb County, Georgia, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E36. 10.5888/pcd13.150442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dailey A, Davidson K, Gaskin K, et al. Responding to food insecurity and community crises through food policy council partnerships in a rural setting. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2022;16(2S):39–44. 10.1353/cpr.2022.0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cyzman D, Wierenga J, Sielawa J. Pioneering healthier communities, West Michigan: a community response to the food environment. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2S):146S–155S. 10.1177/1524839908331269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Franck KL, Jarvandi S, Johnson K, Elizer A, Middleton S, Sammons L. Working with rural producers to expand EBT in farmers’ markets: a case study in Hardeman County, Tennessee. Health Promot Pract. 2023;24:125S–127S. 10.1177/15248399221115707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leone LA, Haynes-Maslow L, Ammerman AS. Veggie Van Pilot Study: impact of a mobile produce market for underserved communities on fruit and vegetable access and intake. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gary-Webb TL, Bear TM, Mendez DD, Schiff MD, Keenan Ehrrin, Anthony F. Evaluation of a mobile farmer’s market aimed at increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in food deserts: a pilot study to determine evaluation feasibility. Health Equity. 2018;2(1):375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gans KM, Risica PM, Keita AD, et al. Multilevel approaches to increase fruit and vegetable intake in low-income housing communities: final results of the ‘Live Well, Viva Bien’ cluster-randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):80. https://proxy.cc.uic.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/2303279008?accountid=14552&bdid=27745&_bd=siDWJGdigHKcM14NZYIC%2FAW2sZg%3D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vermont LN, Kasprzak C, Lally A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a research-tested mobile produce market model designed to improve diet in under-resourced communities: rationale and design for the Veggie Van Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Horning ML, Alver B, Porter L, Lenarz-Coy S, Kamdar N. Food insecurity, food-related characteristics and behaviors, and fruit and vegetable intake in mobile market customers. Appetite. 2021;166:105466. https://proxy.cc.uic.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/2575507701?accountid=14552&bdid=27745&_bd=rAqIqJIOMoDL%2BZV1YmVkP7Zd7BY%3D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ramirez AS, Diaz Rios LK, Valdez Z, Estrada E, Ruiz A. Bringing produce to the people: implementing a social marketing food access intervention in rural food deserts. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(2):166–174.e1. 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hsiao Bi-sek, Sibeko L, Wicks K, Troy LM. Mobile produce market influences access to fruits and vegetables in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(7):1332–1344. 10.1017/S1368980017003755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tripicchio GL, Grady Smith J, Armstrong-Brown J, et al. Recruiting community partners for Veggie Van: strategies and lessons learned from a mobile market intervention in North Carolina, 2012-2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E36. 10.5888/pcd14.160475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Evans EW, Lyerly R, Gans KM, et al. Translating research-funded mobile produce market trials into sustained public health programs: food on the move. Public Health Rep. 2022;137(3):425–430. 10.1177/00333549211012409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cueva K, Lovato V, Nieto T, Neault N, Barlow A, Speakman K. Increasing healthy food availability, purchasing, and consumption: lessons learned from implementing a mobile grocery. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2018;12(1):65–72. 10.1353/cpr.2018.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Redelfs AH, Leos JD, Mata H, Ruiz SL, Whigham LD. Eat Well El Paso!: lessons learned from a community-level restaurant initiative to increase availability of healthy options while celebrating local cuisine. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(6):841–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]