Abstract

Patient: Female, 36-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy

Symptoms: Asymptomatic

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Obstetrics and Gynecology

Objective: Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Background

Cesarean section uterine scar ectopic pregnancies (CSEP) are rare occurrences in which an embryo implants along uterine scar tissue from previous hysterotomies. These cases carry high morbidity and mortality, including risk of significant hemorrhage and uterine rupture. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine guidelines suggest either medical or surgical termination of these pregnancies; however, there are no current definitive recommendations for the management of these cases. Here, we present the case of a 36-year-old patient with a first-trimester CSEP who was managed with local intra-gestational methotrexate (MTX) and 6-month follow-up with beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) monitoring.

Case Report

We describe the case of a stable, asymptomatic 36-year-old patient with 2 previous low transverse cesarean sections, presenting in the early first trimester with a visualized CSEP on ultrasound. The patient was presented with medical and surgical options for management. After extensive counseling, she opted for a medical abortion with an intra-gestational MTX injection. She was monitored with serial quantitative β-hCG measurements for 6 months before complete resolution of the terminated pregnancy, an interval significantly longer than typically observed in similar cases. She did not require additional medication doses or surgical intervention.

Conclusions

After a prolonged surveillance, this patient safely reached undetectable β-hCG levels. There is great variability in the presentation, treatment, and long-term outcome of CSEPs, and management requires extensive provider-patient communication. Medical management with intra-gestational MTX, followed by close monitoring, is a viable option for treating stable, type 2 CSEP in patients who have access to reliable follow-up care.

Keywords: Gestational Age; Injections; Methotrexate; Perinatology; Pregnancy, Ectopic

Introduction

While implantation of a pregnancy within the uterine cavity is physiologically normal, implantation within the myometrial scar tissue created by a previous hysterotomy results in a unique form of ectopic pregnancy called a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) [1]. CSEPs are rare, occurring between 1 in 1800 to 1 in 2656 of pregnancies, and carry high morbidity and mortality rates [1,2]. These abnormal pregnancies are suspected when initial ultrasound demonstrates a low, anterior gestational sac [1]. Current recommendations for diagnosis include an additional trans-vaginal ultrasound with color Doppler imaging [1]. This diagnosis is additionally complicated by the difficulty in discerning the exact implantation location on ultrasound, and if viable, how the growing embryo will impact the structural integrity of the uterus [3].

Two categories of CSEPs have been described in the literature – endogenous and exogenous types – based on the position of the gestational sac [4]. Type 1, the endogenous type, grows into the uterine cavity with potential to reach viability; however, it carries the risk of placenta accreta spectrum and hemorrhage [4]. Type 2, the exogenous type, is even more dangerous, as the pregnancy grows outward through the uterus and towards the bladder and abdominal cavity, causing significant risk for scar rupture and subsequent intra-abdominal bleeding [2]. Because of these significant risks, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends against the continuation of a CSEP, endorsing surgical or medical management instead [1]. There is limited high-powered data; however, case reports and small studies suggest that resection, aspiration, or intra-gestational MTX are the preferred treatment modalities [1]. Jameel et al described a case of a 34-year-old woman with a history of 4 previous cesarean sections, with a type I CSEP, managed with intramuscular methotrexate followed by hysteroscopic intra-uterine suction, with only 2 weeks to complete resolution [5].

In ectopic pregnancies implanted outside the uterus, standard MTX management often involves systemic therapy, with intramuscular injections [6]. In these cases, the failure rate increases linearly with gestational age, such that those above 8 weeks of gestation are typically excluded from this form of treatment [5].

Here, we describe a case of first-trimester CSEP in a 36-year-old patient that was successfully and safely medically managed at 6 weeks 4 days gestational age with an intra-gestational MTX injection, followed by serial β-hCG monitoring.

Case Report

We present the case of a 36-year-old G3P2002 woman at 5 weeks 5 days of gestation with a history of 2 low transverse cesarean sections who was referred to our facility. Outside work-up included a quantitative β-hCG of 18 194 mIU/mL and trans-vaginal ultrasound demonstrating a gestational sac containing only a yolk sac without a fetal pole, with only a 2.7-mm overlying layer of myometrium (Figure 1). These findings were concerning for type 2 CSEP [4]. At this time, the patient was hemodynamically stable, with no abdominal rigidity, signs of hemorrhage, or change in mental status. Given her clinical status, she was presented with both surgical and medical abortive options. She opted for MTX injection with serial β-hCG monitoring. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, and a coagulation panel were collected before injection, and were determined to be within normal limits. We began medical management at 6 weeks 4 days of gestation. Initially, an attempt was made to inject MTX directly into the gestational sac under ultrasound guidance; however, the attempt was stopped due to patient discomfort. She was moved to the operating room under spinal anesthesia. Using trans-vaginal ultrasound guidance, a 20-gauge needle was passed through the cervix, and 1 cc of blood-tinged amniotic fluid was aspirated. Then, 50 mg of MTX in 2 mL solution was injected directly into the gestational sac.

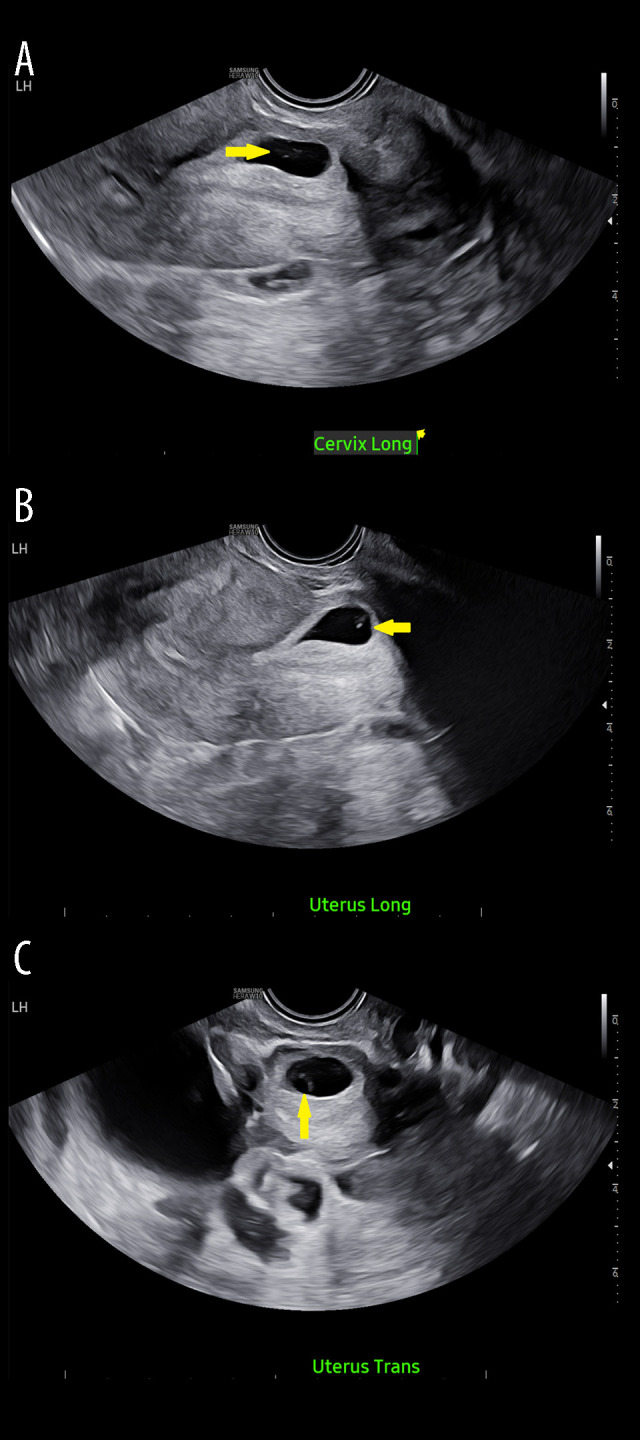

Figure 1.

Diagnostic trans-vaginal ultrasound at 6 weeks 3 days of gestation. (A) Cervix long view: yellow arrow indicating gestational sac without fetal pole. (B) Uterus long view: yellow arrow indicating gestational sac without fetal pole. (C) Uterus transverse view: yellow arrow indicating gestational sac without fetal pole.

The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged on postoperative day 2, with strict follow-up on days 4 and 7. Initially, her β-hCG showed a promising drop from 40 035.21 to 34 759.04 on postoperative day 2, with a rebound to 49 887 on postoperative day 4. This rise in β-hCG was assumed to be due to degradation of products of conception [7]. She was asymptomatic, meeting all post-procedure goals, and was cleared for discharge. Her care was transferred back to her primary OB/GYN, with the understanding that additional intramuscular doses of MTX ly would be required if there was less than a 15% drop in the postoperative β-hCG between day 4 and day 7 after MTX injection.

Her primary provider contacted us on day 7 to inform us that her β-hCG had dropped approximately 14% (49 887 down to 42 888), below the desired level of 15%. She continued to do well, and her comprehensive metabolic panel was within normal limits. She was opposed to surgical options unless necessary. This, in addition to her compliance and the adverse-effect profile of MTX, we ultimately decided to forgo additional treatment and continue to closely monitor β-hCG levels.

She underwent serial evaluation of β-hCG for over 5 months, with resolution occurring 161 days after her initial MTX injection (Table 1, Figure 2), at which point we determined that her medical abortion had been successful, and there was complete resolution of the pregnancy (Figure 3). The literature shows that a prolonged time to complete resolution is to be expected; however, this evidence is in a small pool with a substantially shorter time to resolution than our patient [8].

Table 1.

beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (β-HCG) vs time. Data points include serum quantitative β-hCG values (uMI/mL) collected before and after injection of intra-gestational methotrexate.

| Specimen collection date | Quantitative β-HCG |

|---|---|

| Pre-procedure (5 weeks, 5 days) | 18 194 |

| Pre-procedure (6 weeks, 3 days) | 40 035.21 |

| Procedure Day | ------------ |

| Post-op Day 2 | 34 759.04 |

| Post-op Day 4 | 49 887 |

| Post-op Day 7 | 42 888 |

| Post-op Day 13 | 7619 |

| Post-op Day 20 | 2814 |

| Post-op Day 27 | 997.1 |

| Post-op Day 34 | 493 |

| Post-op Day 43 | 220 |

| Post-op Day 49 | 147.7 |

| Post-op Day 59 | 91 |

| Post-op Day 71 | 105 |

| Post-op Day 73 | 108 |

| Post-op Day 76 | 95 |

| Post-op Day 101 | 69 |

| Post-op Day 135 | 18 |

| Post-op Day 161 | 3 |

Figure 2.

beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) vs time: quantitative serum β-hCG in uMI/mL before and after intra-gestational methotrexate, reflective of values in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Post-treatment trans-vaginal ultrasound: Trans-vaginal ultrasound image obtained from outside provider 27 days after the ultrasound-guided methotrexate injection into the gestational sac. An intra-gestational sac is not visualized on this ultrasound, indicating continued resolution of the cesarean section scar ectopic pregnancy.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that stable patients, who clearly understand the risks and benefits of CSEP management, with consistent and reliable follow-up, can be safely managed with intra-gestational MTX and serial β-hCG monitoring. CSEPs present unique challenges to obstetric teams, given their elusive diagnosis and lack of standardized treatment regimens [1]. A Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine consensus statement advises that these pregnancies be actively managed due to the high risk of associated morbidity, and patients should be counseled regarding medical or surgical management [1]. However, due to the rarity of CSEP, definite recommendations do not exist [1,2].

For hemodynamically unstable patients or those desiring definitive CSEP treatment, surgery is the preferred option [9]. Surgical management of CSEPs includes laparoscopic CSEP resection, trans-vaginal CSEP aspiration and resection, and curettage alone. Current recommendations from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine include laparoscopic resection or trans-vaginal aspiration due to the low adverse-effect profile, but curettage is not recommended because it carries a higher risk of hemorrhage and uterine perforation. Additionally, hysterectomy is another surgical option for CSEP and is considered particularly appropriate if the patient is diagnosed with CSEP in the second trimester or does not desire future fertility [1]. As with any surgery, these procedures carry the risk of infection, bleeding, damage to surrounding structures, and the possible loss of future fertility; however, the risk of infection is low enough that large trials do not recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics [10].

In hemodynamically stable patients, medical treatment can be the first-line therapy, with systemic or intra-gestational MTX injection [1]. This approach serves as a less invasive option, but requires close follow-up and may be associated with risks, including ectopic rupture, gastrointestinal problems, elevated liver function test results, and, rarely, nephrotoxicity [11]. Further risks of MTX injection include fetal anomalies if the woman conceives within 3 months after the injection, elevation of liver enzymes, and bone marrow suppression [11]. There is also evidence that conservative management of these cases may result in longer times to resolution, as seen in our case, or increased risk of re-intervention [12]. While our patient had resolution of β-hCG after 167 days, this is longer than the mean time seen in other cases of CSEP treated with intra-gestational methotrexate. A retrospective study by Rouvalis et al showed that 17 out of 19 patients with CSEP treated with intra-gestational MTX had resolution; out of the 17 patients, the mean time to complete resolution of β-hCG was 97.6±30 days (minimum: 42 days, maximum: 147 days) [13]. This timeline to resolution is further supported by Kim and Moon, who assessed the mean time to complete resolution in 26 patients who received intra-gestational MTX: 25 experienced resolution within 56.4 days, with a standard deviation of 21.6 days [14]. Our patient fits well into this demographic’s median maternal age and gestational age, although with more cesarean sections than their median [14]. Therefore, the possibility of longer time to β-hCG resolution, in contrast to the resolution seen within 1 week in Jameel et al, should be included in the counseling of patients [5]. Systemic MTX is typically avoided due to the higher risk of these complications and adverse effects.

Our case highlights the need for more specific guidelines in managing CSEPs, despite their rarity. Data suggest that a local MTX injection may be sufficient in resolving these pregnancies; however, our case demonstrates that even with initial improvement, longitudinal monitoring and repeat injection may be required months after the primary injection. Additionally, this form of treatment requires patients to be present for repeat laboratory monitoring and adhere to reliable contraception following MTX injection.

Conclusions

There are currently no definitive recommendations for management of CSEPs, beyond termination of pregnancy, given the risk to the patient. While our case demonstrates the success of CSEP medical management with close follow-up in a clinically stable patient, due to the absence of standardized guidelines or recommendations, treatment must be tailored to individual cases. In medical management with MTX, it is vital to ensure compliance with frequent blood monitoring of β-hCG levels, and to be prepared to repeat MTX injections or move to more invasive measures if necessary. Additionally, surgical management must always be considered in patients who are unstable, unable to have adequate follow-up, or fail medical management.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Department and Institution Where Work Was Done: This work was completed through the Department of Maternal Fetal Medicine at Wellstar Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, Georgia.

Patient Permission/Consent: Obtained.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity: All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: None declared

References

- 1.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Miller R Gyamfi-Bannerman C; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(3):B9–B20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glenn TL, Bembry J, Findley AD, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: Current management strategies. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(5):293–302. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riaz RM, Williams TR, Craig BM, Myers DT. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: Imaging features, current treatment options, and clinical outcomes. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(7):2589–99. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(6):592–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00300-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jameel K, Abdul Mannan GE, Niaz R, Hayat DE. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: A diagnostic and management challenge. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14463. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalil A, Saber A, Aljohani K, Khan M. The efficacy and success rate of methotrexate in the management of ectopic pregnancy. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26737. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashiach R, Kislev I, Gilboa D, et al. Significant increase in serum hCG levels following methotrexate therapy is associated with lower treatment success rates in ectopic pregnancy patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;231:188–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi M, Ohba T, Katabuchi H. Safety and efficacy of a single local methotrexate injection for cesarean scar pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(3):416–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt R, Saha A. Management of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: A retrospective study and literature review. Cureus. 2024;16(11):e74515. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lissauer D, Wilson A, Hewitt CA, et al. A randomized trial of prophylactic antibiotics for miscarriage surgery. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1012–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soysal S, Anık İlhan G, Vural M, Yıldızhan B. Severe methotrexate toxicity after treatment for ectopic pregnancy: A case report. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;13(4):221–23. doi: 10.4274/tjod.80457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verberkt C, Lemmers M, de Leeuw RA, et al. Effectiveness, complications, and reproductive outcomes after cesarean scar pregnancy management: A retrospective cohort study. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;3(1):100143. doi: 10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouvalis A, Vlastarakos P, Daskalakis G, et al. Caesarean scar pregnancy: Single dose of intrasac ultrasound-guided methotrexate injection seems to be a safe option for treatment. Ultrasound Int Open. 2023;9(1):E18–E25. doi: 10.1055/a-2137-8318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YR, Moon MJ. Ultrasound-guided local injection of methotrexate and systemic intramuscular methotrexate in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61(1):147–53. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]