Abstract

We developed fluorescent mono- and multivalent opsonophagocytic assays (fOPA and fmOPA, respectively) specific for seven Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F). Bacterial survival was quantitated with alamar blue, a fluorescent metabolic indicator. Both fOPA and fmOPA allow for determination of viability endpoints for up to seven serotypes with high levels of agreement to the reference method. The fmOPA eliminates colony counting, reduces serum volume, and produces results in 1 day.

Polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines have been developed against disease-causing Streptococcus pneumoniae or pneumococcal (Pnc) serotypes (16) and have been shown to be effective in reducing disease and carriage of the vaccine serotypes in diverse populations (1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 17). Opsonophagocytic assays (OPAs) are used to measure the functional antibody activity of anti-polysaccharide Pnc antibodies. The presence of functional antibodies appears to correlate with vaccine-induced protection (9, 10). Recently, the reference viability OPA (18) was evaluated in a multilaboratory study (19) and proved to be a useful tool for vaccine evaluation (7). However, the reference assay requires colony counting, large quantities of sera, and evaluation of one serotype at a time. To improve on the single-serotype OPA, antibiotic resistance markers have been used for selection of serotypes in multivalent OPA formats (2, 12).

In this study, we developed a rapid OPA that uses bacterial cell viability as an endpoint for the measurement of functional pneumococcal antibodies. We compared killing OPA titers obtained by two different viability endpoints (fluorometric versus colony counting) in a single-serotype and multivalent format. We evaluated the fluorescent OPAs using a panel of quality control sera (19). A set of 12 paired reference sera (pre- and postvaccination) from adult volunteers immunized with a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine were collected, aliquoted, and lyophilized at the Oxford Blood Transfusion Service, Oxford, United Kingdom.

All Pnc strains used in the single-serotype or monovalent fluorescent OPA (fOPA) were as previously described (18). The strains used in the fluorescent multivalent OPA (fmOPA) were as described by Bogaert et al. (2) except for Pnc serotype 14 (optochin resistant, donated by M. Nahm, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL), and Pnc serotype 19F (DS1235-99, penicillin resistant at 0.5 μg/ml), a clinical isolate from the Streptococcal Reference Laboratory, CDC, Atlanta, GA. Pnc serotypes were confirmed by Quellung reaction using type-specific antiserum. Antibiotic resistance was confirmed for the fmOPA strains. All strains were at least 90% opaque except for the rifampin-resistant 18C strain (50% opaque).

The reference OPA used was performed as published previously (18). This single-serotype OPA has a colony counting endpoint, and it was used for comparison to develop and standardize the fOPA and fmOPA. The reference OPA used HL-60 cells differentiated into polymorphonuclear leukocytes for 5 days with an effector-to-target cell ratio of 400:1 (6, 18). OPA titers were determined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution with ≥50% killing of the bacterial load. Rabbit complement was purchased from PelFreez (Brown Deer, WI). The bacterial load was 1,000 CFU per well. The reference preparation was purified immunoglobulin G (Bayer, Elkhart, IN).

The single-serotype fOPA followed exactly the same format and used the same reagents and target strains as the reference OPA (18). Modifications include the following. After the 45-minute incubation period for opsonophagocytosis, the microtiter plate was centrifuged for 5 min at 600 × g to differentially pellet HL-60 cells, while leaving the bacteria in suspension. Using a robotic liquid handler (Precision 2000; Biotek, Winooski, VT) programmed to avoid disturbing the HL-60 cell pellet, 20 μl from each well of the plate was replica plated onto a daughter plate containing 40 μl per well of alamar blue buffer. The alamar blue buffer consisted of 25% Todd-Hewitt broth containing 0.5% yeast extract (THYE), 65% opsonophagocytosis buffer (Hanks balanced salt solution with 0.1% gelatin), and 10% alamar blue indicator (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH). The daughter plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 5 to 6 h until the complement control wells read ≥20,000 fluorescent units (FU) in a fluorometer at 530/590 nm for excitation/emission wavelengths (BioTek model FL600; gain, 75). The metabolic activity of the bacteria changed the alamar blue to a lavender color. OPA titers were determined as the reciprocal of the dilution with ≤50% of the mean fluorescence detected in the complement control wells in the absence of serum antibodies but with all other assay components present.

The format of the fmOPA was similar to that of the fOPA, but the fmOPA used a mixture of seven Pnc strains, each with a different antibiotic resistance marker. The multivalent assay required additional modifications, such as an effector/target cell ratio of 11:1, 8 × 105 differentiated HL-60 cells per well, additional complement source (20 μl per well), and additional opsonophagocytosis buffer (140 μl per well) to be added to a mother plate to generate seven daughter plates. Each strain was diluted in OPA buffer, and all seven strains were mixed to yield a final suspension containing approximately 10,000 bacteria per strain in a 20-μl volume for a total bacterial suspension of 70,000 bacteria in each well. Lower numbers of bacteria per strain in the mother plate did not affect the titer (1,000 to 10,000); however, it resulted in longer incubation periods for the daughter plates (up to 8 h) to obtain similar fluorescent signals. Each daughter plate contained a different antibiotic at half the MIC for each given strain. OPA titers were determined as described above for the fOPA.

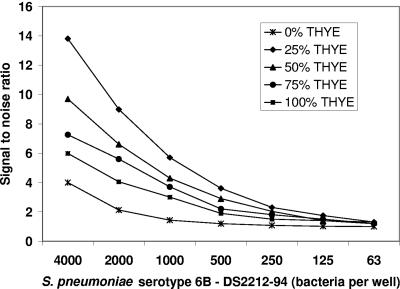

Figure 1 gives the signal-to-noise ratios obtained with five different reaction mixtures containing various THYE concentrations and a constant alamar blue concentration (10%) at various inocula of bacteria. A 10% concentration of alamar blue in the reaction mixture yielded a final concentration of 6.5% to measure metabolic activity by the bacterial inoculum.

FIG. 1.

Signal-to-noise ratios for five alamar blue reaction mixtures with various bacterial inocula. Signal was defined as mean fluorescence in the presence of bacteria. Noise was defined as the mean fluorescence of the reagent blanks in the absence of bacteria for each corresponding buffer condition. The total incubation period was 4 h. Reaction mixtures contained various concentrations of THYE and a constant concentration (10%) of alamar blue. The mixtures were tested with several concentrations of S. pneumoniae serotype 6B, reference strain DS2212-94 (63 to 4,000 CFU in a 20-μl well volume). At 4,000 CFU, the signal ranged from 82,358 FU with 25% THYE to 93,714 FU for 100% THYE. The blanks ranged from 5,966 FU with 25% THYE to 15,660 FU with 100% THYE. Thus, the optimized formulation (greatest signal-to-noise ratio) was obtained with 25% THYE.

To evaluate the fluorescent assay, discontinuous titers from the fOPA were compared to titers from the in-house reference OPA, with both assays using the same target strains. Table 1 shows the cumulative percentages of OPA titers within 1, 2, and 3 twofold dilutions per serotype. The majority of fOPA titers were within 1 dilution (50 to 95.8%), and almost all were within 3 dilutions (95.8 to 100%) of the reference OPA titers for all serotypes. To evaluate the fmOPA, titers were compared to the in-house reference OPA titers, which used different target strains. Serotypes 4, 9V, 19F, and 23F had high agreement (≥92% matched within 3 twofold dilutions). Agreement was lower (≤3 dilutions) for serotypes 6B, 14, and 18C, with 75%, 79.2%, and 83.3%, respectively. In addition, the fmOPA titers were compared to the published median values from a multilaboratory study where five laboratories tested the same sera using the reference OPA method (19). OPA titers that were more than 3 twofold dilutions apart from this median titer were repeated, and the median values of all repeats were used for further analysis. Cumulative percentages are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Cumulative percent agreement in titer among three OPA methods (reference, fOPA, and fmOPA)

| Serotype | % Agreement in titer between methods or r valuea

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference vs fOPA

|

Reference vs fmOPA

|

Reference multilaboratory vs fmOPA

|

||||||||||

| % ≤ 1 | % ≤ 2 | % ≤ 3 | r value | % ≤ 1 | % ≤ 2 | % ≤ 3 | r value | % ≤ 1 | % ≤ 2 | % ≤ 3 | r value | |

| 4 | 70.8 | 83.3 | 100 | 0.89 | 66.6 | 87.5 | 95.8 | 0.87 | 91.7 | 100 | 100 | 0.97 |

| 6B | 79.2 | 95.8 | 100 | 0.94 | 58.3 | 66.6 | 75 | 0.71 | 75 | 95.8 | 100 | 0.85 |

| 9V | 70.8 | 83.3 | 95.8 | 0.84 | 58.3 | 70.8 | 91.7 | 0.66 | 75 | 83.3 | 91.7 | 0.76 |

| 14 | 66.7 | 87.5 | 95.8 | 0.92 | 41.2 | 66.6 | 79.2 | 0.85 | 45.8 | 66.7 | 83.3 | 0.84 |

| 18C | 50 | 79.2 | 95.8 | 0.79 | 62.5 | 79.2 | 83.3 | 0.75 | 58.3 | 75 | 87.5 | 0.88 |

| 19F | 54.2 | 87.5 | 95.8 | 0.91 | 62.5 | 83.3 | 91.7 | 0.76 | 62.5 | 75 | 91.7 | 0.78 |

| 23F | 95.8 | 100 | 100 | 0.98 | 79.2 | 91.6 | 100 | 0.92 | 62.5 | 87.5 | 95.8 | 0.87 |

% ≤ 1, % ≤ 2, or % ≤ 3, within 1, 2, or 3 dilutions of the single-serotype reference OPA titers or the reference multilaboratory median titers (19). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA comparing the set of four OPA titers (reference OPA titers, reference multilaboratory OPA titers, fOPA titers, and fmOPA titers) showed no significant differences in the titers obtained for six of the seven serotypes (P ≥ 0.09) except for serotype 9V (P = 0.009). A significant difference (P = 0.036) was found only by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test comparison of fmOPA titers with reference OPA titers but not between fmOPA titers and multilaboratory titers for serotype 9V.

Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks showed no statistically significant differences among the four sets of titers (reference OPA, reference multilaboratory OPA, fOPA, and fmOPA) for serotypes 4, 6B, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F (P ≥ 0.09). Only serotype 9V showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.036) by the ANOVA comparison described above and by Mann-Whitney rank sum analysis of fmOPA titers and in-house reference OPA titers. ANOVA among reference OPA, reference multilaboratory OPA, and fOPA titers for serotype 9V showed no statistically significant difference (P = 0.138), nor did the Mann-Whitney rank sum test comparing fmOPA titers to reference multilaboratory OPA titers (P = 0.256).

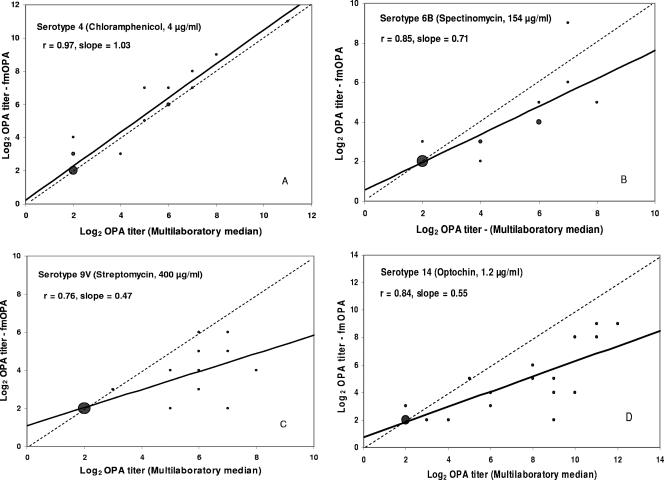

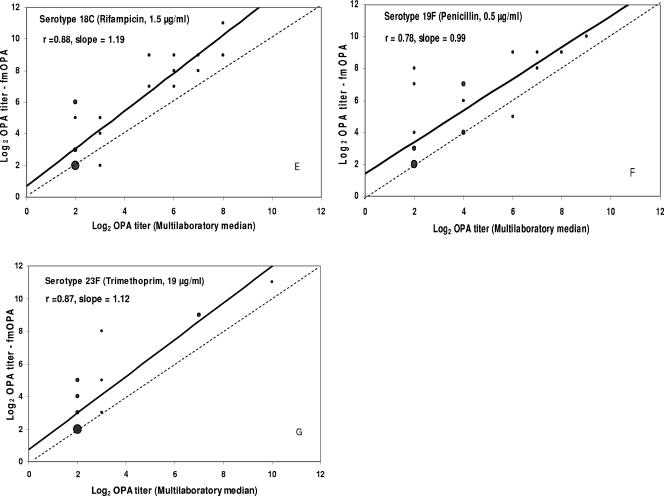

The logarithmically transformed titers (base 2) were plotted in identity graphs for regression analysis using Microsoft Excel, version 2002 (Fig. 2). Comparison of reference OPA with fOPA titers yielded r values ranging from 0.79 to 0.98 (Table 1), and slopes were between 0.71 and 1.0. When fmOPA titers were compared to in-house reference OPA titers, the r values ranged from 0.66 to 0.92 and the slopes from 0.37 to 0.78. Finally, comparison of the fmOPA titers to the median values from the multilaboratory study gave r values ranging from 0.76 to 0.97 and slopes from 0.47 to 1.19.

FIG. 2.

Identity graphs comparing fmOPA titers to the reference multilaboratory OPA titers (19) for seven serotypes as shown in panels A to G. The solid line is the linear regression; the broken line is the line of identity. The size of the data point represents the number of serum samples that are at that coordinate (n = 24).

We have developed an OPA method that gives advantages over previously described methods (2, 12, 14, 18) by combining seven serotypes into a single, semiautomated, 1-day assay that yields titers comparable to those obtained using the single-serotype reference colony counting viability OPA. However, this methodology requires a fluorometer and a liquid handler to facilitate replica plating between mother and daughter plates.

Our alamar blue fOPA yielded a signal-to-noise ratio of 6:1 under optimal buffer conditions (Fig. 1), which is an improvement over the chromogenic indicator OPA developed for two Pnc serotypes by Lin et al. (13) with similar numbers of bacteria. The alamar blue indicator has been successfully incorporated into serum bactericidal activity assays for Haemophilus influenzae type b and Neisseria meningitidis to achieve fluorometric readouts of viability without affecting titer determination (15, 20).

Our fmOPA yielded high agreement (Table 1) with median titers from a previously reported multilaboratory study (19). Although different bacterial strains were used by the methods, the titers were largely conserved. Titers for all serotypes agreed within 3 dilutions (twofold) for at least 75% of the sera. The multilaboratory evaluation of the reference OPA resulted in 80% or greater interlaboratory agreement in OPA titers for the serotypes evaluated (19). Advantages of the fmOPA are semiautomation of a single-day assay, elimination of colony counting, multivalent capacity, and ease in data analysis. In addition, the amount of sera required for testing of seven serotypes is reduced by 86%, and throughput is greatly enhanced in comparison to the reference viability assay.

Comparison of the fmOPA to the reference multilaboratory OPA yielded better agreement than to the in-house reference OPA. Since the multilaboratory titers were the median values from several laboratories, they account better for the equivocal titers given by some sera. The lack of agreement in titer for selected sera may be due to limiting complement concentrations or to individual serum antibody avidities. Increasing the amount of complement in the assay improved the titers for some trouble sera, particularly in serotype 14, but compromised the performance of other serotypes (data not shown). In addition, three trouble sera had low avidity for serotype 9V or 14 (33 to 53% reduction in antibody concentration with 0.5 M thiocyanate elution). It has been suggested that sera with high titers (above 512) be retested at an initial dilution higher than 1:8 (7). This would be a practical approach to confirm the linearity of high-titer sera, as well as ensuring a complement excess in the multivalent reaction mixture.

The antibiotic resistance strain for serotype 6B used in the multivalent assay (fmOPA) exhibited significantly lower growth rates compared to all other strains in the panel. We have identified a replacement strain for serotype 6B with erythromycin resistance for selection. Quality assurance is needed when using antibiotic-resistant Pnc strains. Growth, maintenance, and storage of master and working bacterial stocks must be controlled for strain stability in terms of growth rate, opacity, and antibiotic resistance marker.

In summary, the fmOPA allows for the simultaneous determination of a viability endpoint for seven Pnc serotypes in one mother plate setup, thereby reducing the serum volume required for testing. Our analysis showed high agreement of the fmOPA with the reference viability method: at least 75% of titers matched within 3 dilutions for all serotypes. The assay eliminates colony counting, produces results in a single day, and can be a useful tool for pneumococcal vaccine evaluation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Moon Nahm (University of Alabama, Birmingham) and Peter Hermans (Erasmus Sophia Medical Center, The Netherlands) for providing the Pnc strains used in this study.

We thank the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) for providing funding for Kathryn Bieging and Gowrisankar Rajam through the Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory Fellowship program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black, S. B., H. R. Shinefield, S. Ling, J. Hansen, B. Fireman, D. Spring, J. Noyes, E. Lewis, P. Ray, J. Lee, and J. Hackell. 2002. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than five years of age for prevention of pneumonia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 21:810-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogaert, D., M. Sluijter, R. de Groot, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2004. Multiplex opsonophagocytosis assay (MOPA): a useful tool for the monitoring of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine 22:4014-4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capeding, M. Z. R., T. Puumalainen, C. P. Gepanayao, H. Käyhty, M. G. Lucero, and H. Nohynek. 10. August 2003, posting date. Safety and immunogenicity of three doses of an eleven-valent diphtheria toxoid and tetanus protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine in Filipino infants. BMC Infect. Dis. 3:17. [Online.] http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/3/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutts, F. T., S. M. A. Zaman, G. Enwere, S. Jaffar, O. S. Levine, J. B. Okoko, C. Oluwalana, A. Vaughan, S. K. Obaro, A. Leach, K. P. McAdam, E. Biney, M. Saaka, U. Onwuchekwa, F. Yallop, N. F. Pierce, B. M. Greenwood, and R. A. Adegbola. 2005. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 365:1139-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flannery, B., S. Schrang, N. M. Bennett, R. Lynfield, L. H. Harrison, A. Reingold, P. R. Cieslak, J. Hadler, M. M. Farley, R. R. Facklam, E. R. Zell, and C. G. Whitney. 2004. Impact of childhood vaccination on racial disparities in invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. JAMA 291:2197-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleck, R. A., S. Romero-Steiner, and M. H. Nahm. 2005. Use of HL-60 cell line to measure opsonic capacity of pneumococcal antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu, B. T., X. Yu, T. R. Jones, C. Kirch, S. Harris, S. W. Hildreth, D. V. Madore, and S. A. Quataert. 2004. Approach to validating an opsonophagocytic assay for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:287-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huebner, R. E., N. Mbelle, B. Forrest, D. V. Madore, and K. Klugman. 2004. Long-term antibody levels and booster responses in South African children immunized with nonavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine 22:2696-2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jódar, L., J. Butler, G. Carlone, R. Dagan, D. Goldblatt, H. Käyhty, K. Klugman, B. Plikaytis, G. Siber, R. Kohberger, I. Chang, and T. Cherian. 2003. Serological criteria for evaluations and licensure of new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine formulations for use in infants. Vaccine 21:3265-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, S. E., L. Rubin, S. Romero-Steiner, J. K. Dykes, L. B. Pais, A. Rizvi, E. Ades, and G. M. Carlone. 1999. Correlation of opsonophagocytosis and passive protection assays using human anticapsular antibodies in an infant mouse model of bacteremia for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 180:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilpi, T., H. Åhman, J. Jokinen, K. S. Lankinen, A. Palmu, H. Savolainen, M. Grönholm, M. Leinonen, T. Hovi, J. Eskola, H. Käyhty, N. Bohidar, J. C. Sadoff, and P. H. Mäkelä. 2003. Protective efficacy of a second pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal acute otitis media in infants and children: randomized, controlled trial of a 7-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide-meningococcal outer membrane protein complex conjugate vaccine in 1666 children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1155-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, K. H., J. U. Yu, and M. H. Nahm. 2003. Efficiency of a pneumococcal opsonophagocytic killing assay improved by multiplexing and by coloring colonies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:616-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, J. S., M. K. Park, and M. H. Nahm. 2001. Chromogenic assay measuring opsonophagocytic killing capacities of antipneumococcal antisera. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:528-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez, J. E., S. Romero-Steiner, T. Pilishivili, S. Barnard, J. Schinsky, D. Goldblatt, and G. Carlone. 1999. A flow cytometric opsonophagocytic assay for measurement of functional antibodies elicited after vaccination with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:581-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mountzouros, K. T., and A. P. Howell. 2000. Detection of complement-mediated antibody-dependent bactericidal activity in a fluorescence-based serum bactericidal assay for group B Neisseria meningitidis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2878-2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulholland, K. 1999. Strategies for the control of pneumococcal diseases. Vaccine 17:S79-S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obaro, S., and R. Adegbola. 2002. The pneumococcus: carriage, disease and conjugate vaccines. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:98-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Steiner, S., D. Libutti, L. B. Pais, J. Dykes, P. Anderson, J. C. Whitin, H. L. Keyserling, and G. M. Carlone. 1997. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:415-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Steiner, S., C. Frasch, N. Concepcion, D. Goldblatt, H. Käyhty, M. Väkeväinen, C. Laferriere, D. Wauters, M. H. Nahm, M. F. Schinsky, B. D. Plikaytis, and G. M. Carlone. 2003. Multilaboratory evaluation of a viability assay for measurement of opsonophagocytic antibodies specific to the capsular polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:1019-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero-Steiner, S., W. Spear, N. Brown, P. Holder, T. Hennessy, P. Gomez de Leon, and G. Carlone. 2004. Measurement of serum bactericidal activity specific for Haemophilus influenzae type b by using a chromogenic and fluorescent metabolic indicator. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 11:89-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]