Abstract

Introduction

Bladder cancer is a common malignancy in the United States and while the majority are non-muscle invasive at diagnosis, those with muscle-invasive and locally advanced disease can be challenging to manage. In addition, the prognosis is poorer in this group with high rates of recurrence following treatment. Clinical trials and advances in systemic therapy have helped to improve outcomes for these patients.

Materials/methods

Articles were chosen for inclusion based on expert knowledge of the literature and PubMed literature searches for the relevant areas, with a focus on clinical trials. Appropriate articles were selected for inclusion by reviewing article titles, abstracts and full texts.

Results

The standard of care for treatment of muscle invasive bladder cancer involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy. The NIAGARA trial recently changed the standard of care to include immunotherapy both in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. Multiple clinical trials have assessed the potential benefit of adjuvant immunotherapy in patients with high-risk disease after radical cystectomy, leading to the approval of nivolumab in this setting. Improvements in staging and surveillance of these patients are necessary. The use of circulating tumor DNA and advances in imaging have also shown promise in prognostication and detection and monitoring of recurrence.

Conclusions

Locally advanced bladder cancer is a challenging condition to manage, and while advances have been made in systemic therapy and biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA, further investigation is needed to continue to improve outcomes for this group of patients.

Keywords: Locally advanced bladder cancer, Urothelial cancer, Urinary bladder neoplasms

Introduction

Bladder cancer is a prevalent malignancy in the United States (US) with over 83,000 new cases diagnosed in 2024 [1]. While roughly 75% of new cases represent non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), the remainder are either muscle invasive (T2, MIBC) or metastatic at presentation [2]. Some patients with high risk NMIBC, particularly those with features such as HGT1 disease, variant histology, hydronephrosis and lymphovascular invasion, are at significant risk of progression, upstaging and occult lymph node metastases at radical cystectomy (RC) [3].

Management of MIBC can be challenging and prognosis is highly dependent on pathologic T and N stage [4]. Locally invasive disease, defined as tumors invading the perivesical soft tissue (T3), adjacent organs such as the prostate, uterus, vagina or the abdominal wall or pelvic side walls (T4), or lymph node positive disease (N+), have demonstrably poorer prognosis than those with organ confined (T2) disease, with post-cystectomy recurrence rates ranging from 20 to 30% in those with T2 disease to as high as 70% in those with N + disease [5, 6]. Determination of locally advanced disease is usually made with imaging, exam under anesthesia and pathology at transurethral resection (TUR). Cross-sectional imaging can identify perivesical involvement/inflammation, direct extension to other organs or lymphadenopathy. Exam under anesthesia involves a bimanual exam after TUR of the tumor and has been shown in various studies to offer important clinical staging information and concordance with pathologic stage [7, 8]. Pathology at TUR, particularly if prostatic urethral disease is present, also helps to delineate a patient’s stage. For example, prostatic ductal involvement would represent pTis disease, prostatic stromal involvement separate from the bladder tumor would represent pT2 disease and direct extension into the prostatic stroma from the bladder tumor would represent pT4 disease. These different disease states also portend different prognoses [9, 10].

The gold standard of treatment of MIBC (including T3/T4 disease) remains neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by RC. While recent advances in systemic therapy have shown promise, prognosis overall remains poor, calling for continued efforts to improve outcomes in these patients. In this review, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the management of T3 and T4 bladder cancer, including future directions.

Materials/methods

A narrative (non-systematic) review was performed. Articles were chosen for inclusion based on expert knowledge of the literature and PubMed literature searches for the relevant areas, with a focus on recent clinical trials. Pertinent search terms included “locally advanced”, “bladder cancer”, “urothelial carcinoma”, “T3”, “T4”, “radical cystectomy”, “variant histology”, “neoadjuvant”, “adjuvant”, “chemotherapy”, including specific medication names such as “gemcitabine”, “cisplatin”, and “enfortumab”, “immunotherapy”, including specific medication names such as “atezolizumab”, “nivolumab”, and “pembrolizumab.” These terms were also searched in combination with terms related to the specific topics to follow. Specific clinical trial names were searched as well. Appropriate articles were selected for inclusion by reviewing article titles, abstracts and full texts.

Results

Neoadjuvant therapy

The recommendation for the use of NAC in MIBC is based on two large phase 3 randomized clinical trials that showed significant rates of pathologic downstaging and survival benefits of 5–6% for those who received NAC compared to those who did not [11–13]. In fact, those with T3/T4 disease appeared to benefit the most from NAC [11]. Both gemcitabine and cisplatin (gem/cis, generally 4 cycles) and dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (ddMVAC, generally 6 cycles) have been studied and both are considered acceptable regimens. The SWOG1314 randomized trial that compared 4 cycles of ddMVAC with 4 cycles of gem/cis found no difference in pathologic complete response (pCR) or downstaging [14]. The prospective VESPER trial compared the two in the perioperative setting (both neoadjuvant and adjuvant) and included patients with pure urothelial carcinoma and either cT2-4aN0M0 disease (neoadjuvant group) or pTanyN1-2M0 disease (adjuvant group). The authors found no differences in 5-year overall survival (OS) in the cohort as a whole but did find improved 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) and 5-year OS rates in the neoadjuvant subgroup for those who received ddMVAC. However, ddMVAC does confer additional doses of platinum and potentially increased risks of adverse events [15, 16]. It is important to note that only about 16% of the cohort had T3 or T4 disease making it difficult to draw conclusions about which regimen is superior in this group. A large retrospective study looked specifically at this group and found a significantly higher rate of pCR with ddMVAC (28%) compared to gem/cis (14.6%) as well as higher OS with ddMVAC [17].

A patient’s candidacy for cisplatin-based NAC is generally dependent on their functional status, medical comorbidities and baseline renal function, with a glomerular filtration rate of 60 mL/min usually representing the lower limit for eligibility [18]. However, alternative thresholds are increasingly being used, particularly in larger trials. While it is estimated that ~ 60–70% of patients with MIBC are eligible for NAC, only about 20% receive it, for various reasons, including older age or comorbidities [19]. Thus, there is a need for additional therapies in the neoadjuvant setting and improvement in utilization for those who are candidates.

Enfortumab vedotin (EV) is an antibody-drug conjugate targeting Nectin-4, which is highly expressed in urothelial carcinoma. EV, either as single-agent therapy or in combination with the immunotherapeutic PD-1 inhibitor, pembrolizumab, has shown promise in phase 3 trials in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer with significant improvements in OS and PFS [20, 21].

These promising studies have since led to the investigation of these agents in the neoadjuvant setting. For example, the EV-103 phase 1b/2 clinic trial enrolled cisplatin-ineligible patients with cT2-T4aN0M0 disease, over 30% of whom had T3-T4 disease. Patients received neoadjuvant EV followed by RC. The pCR rate was 36.4%, the pathologic downstaging rate was 50% and the event-free survival (EFS) rates was 62% at 2 years [22]. The KEYNOTE-905/EV-303 study (NCT03924895) is a phase 3 trial assessing perioperative (“sandwich” treatment) pembrolizumab alone or in combination with EV in pts with MIBC (T2-T4aN0M0 or T1-T4aN1M0) who are ineligible for or decline cisplatin-based therapy. The primary endpoints of this trial are pCR and EFS [23]. The KEYNOTE-B15/EV-304 study (NCT04700124) is another phase 3 trial assessing combination EV/pembrolizumab (“sandwich” treatment) versus chemotherapy in cisplatin-eligible patients with MIBC (T2-T4aN0M0 or T1-T4aN1M0). The primary endpoints of this trial are also pCR and EFS [24]. These trials all included patients with ≥ 50% urothelial histology, thus allowing for some level of variant histology, an important point as those with variant histology have been historically excluded from trials in this arena.

The NIAGARA phase 3 randomized trial assigned patients to either neoadjuvant gem/cis plus durvalumab followed by RC and then adjuvant durvalumab (“sandwich” treatment) or gem/cis followed by RC. 60% in both arms were >T2N0, a unique strength of this study. Those who received the durvalumab combination therapy, regardless of baseline tumor stage, had significantly improved EFS and OS but with a stronger effect noted in the >T2N0 group [25]. These findings led to the very recent approval of this combination regimen for MIBC by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This trial excluded those with pure variant or small-cell histology but allowed those with urothelial carcinoma with squamous or glandular differentiation. The latter group made up ~ 14–17% of the overall cohort and responded similarly to those with pure urothelial carcinoma.

Neoadjuvant therapy in variant histology can pose an additional challenge given the general underrepresentation of these histologies in many trials and lack of robust evidence. However, a recent review sought to organize the existing evidence in this space. For example, for pure squamous cell carcinoma, epirubicin or combination paclitaxel, carboplatin, and gemcitabine should be considered. In adenocarcinoma, NAC appears to confer favorable oncologic outcomes with some studies having assessed traditional urothelial carcinoma regimens and others 5-fluorouracil-based regimens. In sarcomatoid variants, upfront RC is recommended given the general lack of efficacy of systemic therapy [26]. The benefit of NAC in micropapillary disease remains controversial. One study found no difference in OS, RFS, or CSS in those who received cisplatin-based NAC compared to those who did not [27]. Other studies have shown modest response rates to immunotherapy or EV [28].

Other studies have assessed patients deemed to be unresectable with locally advanced or metastatic disease. The CheckMate 901 study was a phase 3 trial which assessed patients with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Patients were randomized to receive either nivolumab plus gem/cis followed by nivolumab or gem/cis alone. Those in the nivolumab combination group experienced significantly better outcomes (OS, PFS and overall objective and complete response rates) [29]. The JAVELIN 100 trial was another randomized phase 3 clinical trial including patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who did not have disease progression with first-line chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive best supportive care with or without maintenance avelumab. OS and PFS were significantly improved in those who received maintenance avelumab [30]. While none of the patients in these studies went on to RC, these findings mark an important shift in the treatment paradigm of this patient population.

Despite these advances, management of locally advanced and/or clinically N + disease continues to pose a significant challenge for providers. While some may view these patients as metastatic and treat them with definitive systemic therapy, others may opt for neoadjuvant therapy followed by consolidative treatment (either RC or radiation). Typically, those with lymphadenopathy above the level of the pelvis will receive definitive systemic therapy but where exactly this anatomic line is drawn can be a gray area and up to the discretion of the treating provider. In addition, what determines whether a locally advanced bladder cancer is “resectable” is also often in the eye of the beholder and there may be variation across providers.

Radical cystectomy

Radical cystectomy involves removal of the bladder, prostate and seminal vesicles in men and the bladder and possibly the adjacent reproductive organs (anterior vaginal wall, uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries) in women. While there has been a shift towards reproductive organ-sparing procedures in select female patients given the benefits in sexual and urinary function in those with orthotopic diversion [31], this is not always feasible in locally advanced disease. However, one study found that patients with pathologic locally advanced disease (pT3, pT4 and N + at RC) who underwent reproductive organ-sparing surgery had similar oncologic outcomes (RFS, CSS, OS) to those who did not have organ-sparing procedures [32].

Another point of ongoing discourse is the comparison between open RC (ORC) and robotic-assisted RC (RARC). The robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer (RAZOR) trial found comparable 2-year PFS rates between the two approaches [33]. Another study utilizing the National Cancer Database found that that although mortality appeared higher in ORC compared to RARC, there were no statistically significant differences after adjusting for demographics and pathological tumor characteristics [34]. A large randomized clinical trial from the United Kingdom found no difference in oncologic outcomes between the two approaches but less thromboembolic and wound complications and improved number of days alive and out of the hospital in the RARC group [35].

The American Urological Association guidelines state that urethrectomy (immediate or delayed) should be performed in men if there is high grade cancer present at the urethral margin and in women if they are not undergoing orthotopic diversion to reduce the likelihood of a positive margin or recurrence [2]. However, this practice is variable, and the utility is not entirely clear. While some studies have found decreased local recurrence rates and improved survival in those who undergo prophylactic urethrectomy [36], others have not noted a survival benefit [37]. Interestingly, there is also evidence that urethral recurrence rates are lower in those with orthotopic neobladders compared to non-orthotopic diversions [38]. Thus, this practice is generally left to the discretion of the treating provider.

A pelvic LND is another critical facet of RC. This offers important staging information and confers a therapeutic benefit as well. At a minimum, the external and internal iliac and obturator lymph nodes should be removed and at least 10–15 lymph nodes should be removed for the LND to be considered sufficient [39]. A prospective, randomized trial assessed whether standard or extended LND (removal of deep obturator, common iliac, presacral, paracaval, interaortocaval, and para-aortic nodes) impacted outcomes in patients with T1 or T2-T4aM0 disease. Outcomes including RFS, CSS, and OS were not different between the two with some speculation that including those with T1 disease may have contributed to this finding. However, there were increased rates of lymphoceles in the extended group [40]. A subsequent larger prospective randomized trial, SWOG S1011, similarly sought to understand whether standard or extended LND improved OS and disease free-survival (DFS) in patients with localized MIBC (T2-T4a, N0-2). The authors found no difference between the two approaches in terms of oncologic outcomes but did identify higher complication rates in the extended LND group [41].

An area of ongoing research and controversy relates to whether the bladder can be preserved in patients with a clinical CR after neoadjuvant therapy. Several trials are underway to further explore this in combination with genetic testing and immunotherapy. However, existing evidence has shown unacceptably high rates of development of metastatic disease in those who underwent surveillance after a clinical CR and an increased mortality risk with delayed RC. Therefore, RC remains the standard of care [42].

Chemoradiation

An acceptable alternative to RC for patients with localized MIBC is chemoradiation (chemoRT), also known as trimodal therapy. This involves maximal TUR of the bladder tumor with chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy. Ideal candidates for chemoRT generally have localized disease, adequate bladder function, solitary tumors < 7 cm, no or only unilateral hydronephrosis, and minimal or no CIS [43]. While traditionally this option was reserved for patients medically unfit for or refusing RC, a recent, large, retrospective matched-cohort study of over 700 patients with cT2-T4N0M0 disease who were eligible for RC or chemoRT showed similar oncologic outcomes between the two groups [44]. While patients with T3-4 disease comprised a relatively small portion of the overall cohort in this study (and this group remains underrepresented in the literature in general), studies have aimed to assess how these patients fare with chemoRT. One study found that those who underwent chemoRT had significantly higher mortality rates at 5 years and increased risk of metastases compared to those who underwent RC[45]. However, another study that included 30 patients with T3-4 or N + disease who were not candidates for RC and were treated with systemic therapy (chemotherapy or immunotherapy) and definitive radiation found that this may be a reasonable alternative to RC. 40% of patients in this study had some component of variant histology. OS rates at 1- and 2-years were 73% and 61%, respectively; with better survival in the chemotherapy group compared to the immunotherapy group. 1-year PFS was similar between the two groups. Both hydronephrosis and variant histology were significant predictors of worse OS. 40% of the patients experienced some type of recurrence, the majority of which were distant metastases. 33% of the cohort was alive and disease-free at the last follow up [46]. Lastly, a large retrospective study assessed chemoRT in patients with variant histology (including 76% with squamous and/or glandular differentiation and 24% with other histologies) compared to pure urothelial carcinoma. The authors found no significant difference in CR, OS, CSS, or salvage cystectomy rates between the two groups. Of note, the presence of variant histology was not associated with CSS on multivariable analysis [47]. While there is a paucity of data in this space and additional research is needed, these results are encouraging for this group.

Adjuvant therapy

Despite the progress made in the neoadjuvant space, some patients will still have aggressive pathology at RC and recurrence rates can be up to 50% within two years following RC [4, 48, 49]. There are also patients who cannot or do not receive any neoadjuvant therapy for a variety of reasons. Those with variant histology may be over-represented in these scenarios given propensity for upstaging, occult lymph node metastases and limited neoadjuvant therapy options [3, 26, 50], highlighting the need for advances in adjuvant therapies across the spectrum of MIBC.

While most patients who were not candidates for cisplatin-based chemotherapy pre-RC are not candidates post-RC, there is still a role for adjuvant chemotherapy in select patients. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy conferred a significant benefit in various oncologic outcomes including OS, RFS, and metastasis-free survival [51].

Adjuvant immunotherapy has also been an area of great research interest. For instance, the IMvigor010 trial was a randomized phase 3 trial assessing adjuvant atezolizumab versus observation in patients with high-risk disease at RC: ypT2-4a or ypN + disease if the patient had received NAC or pT3-4a or pN + disease if the patient had not received NAC. There was no difference in the primary endpoint of DFS between the two groups, but this was the first completed trial which explored the role of immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting [48]. The CheckMate 274 randomized phase 3 trial assessed the use of adjuvant nivolumab versus placebo in the same patient population and found significantly improved DFS in the nivolumab group [52], noted in both the intention-to-treat population and among patients with a PD-L1 expression level of 1% or more. This led to its approval by the US FDA in August 2021 for patients regardless of PD-L1 status, but in Europe it is only approved for those with PD-L1 expression levels of 1% or more.

Lastly, the AMBASSADOR randomized phase 3 trial assessed the use of adjuvant pembrolizumab in the same patient population (although this trial also allowed variant histology and microscopically positive surgical margins). The authors found significantly improved DFS (but not OS on preliminary analysis) in the pembrolizumab group (regardless of PD-L1 status), although the frequency of adverse events with this medication was significantly higher than that with nivolumab in the CheckMate 274 trial [53].

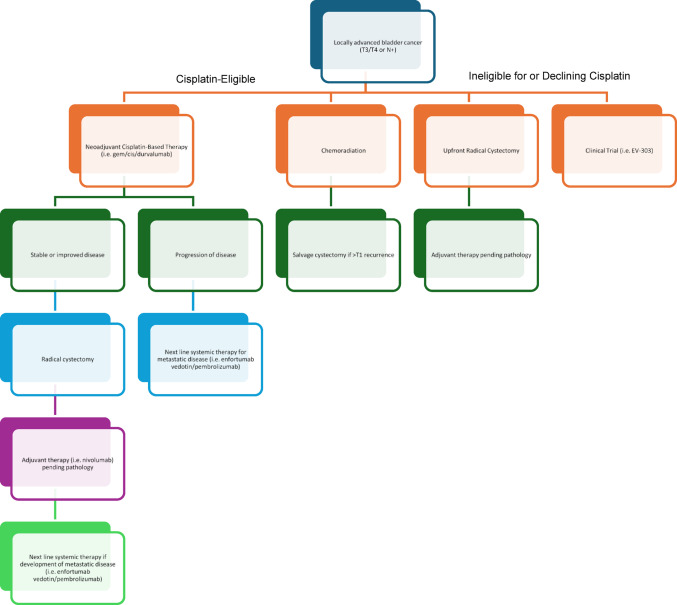

The noteworthy clinical trials in the neoadjuvant, surgical and adjuvant settings are summarized in Table 1. A generalized algorithm for the treatment of patients with locally advanced disease is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Pivotal clinical trials in clinical stage T3/T4 bladder cancer

| Trial name, publication year | Trial ID | Design | Population/eligibility | Intervention | Primary endpoint | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||||||

| Javelin 100, 2024 | NCT02603432 | Phase 3 | Unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma | Neoadjuvant GC without vs. with adjuvant avelumab |

OS PFS (Median 19 months follow-up) |

OS time: sig A/GC: 21.4 months GC: 14.3 months PFS time: sig A/GC: 3.7 months GC: 2.0 months |

| Niagara, 2024 | NCT03732677 | Phase 3 | cT2-T4aN0-1M0 | Perioperative (“Sandwich”) durvalumab plus GC vs. GC alone | EFS |

2-yr EFS: sig D/GC: 67.8% GC: 59.8% 2-yr OS: sig D/GC: 82.2% GC: 75.2% |

| Keynote-869/EV-103, 2024 | NCT03288545 | Phase 1b/2 | cT2-T4aN0M0 | Neoadjuvant EV | pCR |

pCR: 36.4% pDS: 50% 2-yr EFS: 62% |

| Vesper, 2021, 2024 | NCT01812369 | Phase 3 |

cT2-4aN0M0 (neoadjuvant) and pTanyN1-2M0 (adjuvant) |

ddMVAC vs. GC perioperative chemotherapy | 3-yr PFS |

3-yr PFS in whole cohort: not sig dd-MVAC (64%) GC (56%) 5-yr OS in NAC: sig dd-MVAC (66%) GC (57%) 3-yr PFS in NAC: sig dd-MVAC (66%) GC (56%) |

| Checkmate 901, 2023 | NCT03036098 | Phase 3 | Unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma | Neoadjuvant GC without vs. with adjuvant nivolumab |

OS PFS (Median 33.6 months follow-up) |

OS time: sig N/GC: 21.7 months GC: 18.9 months PFS time: sig N/GC: 7.9 months GC: 7.6 months |

| SWOG1314, 2021 | NCT02177695 | Phase 2 | cT2-T4a N0 M0 | ddMVAC vs. GC neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Predictive value of COXEN score for pCR or pDS |

pCR: not sig ddMVAC (28%) GC (30%) pDS: not sig ddMVAC (47%) GC (40%) |

| Radical cystectomy | ||||||

| SWOG S1011, 2024 | NCT01224665 | Phase 3 | cT2-T4N0-2M0 | Standard vs. Extend LND |

DFS OS |

5-yr DFS: not sig Extended: 56% Standard: 60% 5-yr OS: not sig Extended: 59% Standard: 63% |

| Extended vs. limited lnd in bc patients undergoing RC, 2019 | NCT01215071 |

Phase 3 (superiority design ~ 15%) |

HGT1 or cT2-T4aM0 | Limited vs. Extend LND |

RFS CSS OS |

5-yr RFS: not sig Extended: 65% Limited: 59% 5-yr CSS: not sig Extended: 76% Limited: 65% 5-yr OS: not sig Extended: 59% Limited: 50% |

| RAZOR, 2018 | NCT01157676 |

Phase 3 (non-inferiority design ~ 15%) |

cT1-T4N0-1M0 or refractory CIS | Robot-assisted vs. open radical cystectomy | PFS |

2-yr EFS: sig RARC: 72.3% ORC: 71.6% |

| Trial to compare robotically assisted radical cystectomy with open radical cystectomy, 2022 | NCT03049410 | Phase 3 | Non-metastatic, node status ≤ N1, undergoing radical cystectomy | Robot-assisted with intracorporeal diversion vs. open radical cystectomy | Number of days alive and out of the hospital within 90 days of surgery |

Number of days: sig RARC: 82 days ORC: 80 days Note: no differences in RFS or OS between approaches |

| Adjuvant Therapy | ||||||

| Ambassador, 2024 | NCT03244384 | Phase 3 |

>ypT2/ypN+/margin + or >pT3/pN+/margin + |

Adjuvant pembrolizumab vs. observation |

DFS OS (Median 44.8 months follow-up) |

DFS time: sig Pembrolizumab: 29.6 months Observation: 14.2 months |

| Checkmate 274, 2021 | NCT02632409 | Phase 3 |

ypT2-4a/ypN+ or pT3-4a/pN+ |

Adjuvant nivolumab vs. placebo |

DFS (Median 20.9 months follow-up) |

DFS time: sig Nivolumab: 20.8 months Placebo: 10.8 months |

| IMvigor010, 2020 | NCT02450331 | Phase 3 |

ypT2-4a/ypN+ or pT3-4a/pN+ |

Adjuvant Atezolizumab vs. observation |

DFS (Median 21.9 months follow-up) |

DFS time: not sig Atezolizumab: 19.4 months Observation: 16.6 months |

| Trials in progress | ||||||

| Keynote-905/EV-303 | NCT03924895 | Phase 3 |

cT2-T4aN0M0 or cT1-T4aN1M0 |

Perioperative (“Sandwich”) pembrolizumab vs. EVP |

EFS | - |

| Keynote-B15/EV-304 | NCT04700124 | Phase 3 |

cT2-T4aN0M0 or cT1-T4aN1M0 |

EVP vs. cisplatin -based neoadjuvant chemotherapy | EFS | - |

| IMvigor011 | NCT04660344 | Phase 3 |

(y)pT2-4aN0M0 or (y)pT0-4aN + M0 |

Adjuvant atezolizumab vs. placebo in ctDNA + patients | DFS | -† |

| SWOG 2427/BRIGHT | NCT07061964 | Phase 2 | cT0-1 without multifocal CIS following NAC | RT + pembrolizumab | BI-EFS | - |

† Primary unpublished results from IMvigor011 have shown a statistically significant and clinically meaningful increase in DFS and OS for ctDNA-positive patients treated with atezolizumab[65].

A/GC: Avelumab/Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, CSS: Cancer Specific Survival, ctDNA: circulating tumor DNA, DFS: Disease Free Survival, D/GC: Durvalumab/Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, ddMVAC: dose-dense methotrexate/vinblastine/doxorubicin/cisplatin, EFS: Event Free Survival, EV: Enfortumab vedotin, EVP: Enfortumab vedotin/Pembrolizumab/GC: Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, NAC: Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, N/GC: Nivolumab/Gemcitabine/Cisplatin, ORC: Open Radical Cystectomy, OS: Overall Survival, pCR: pathologic complete response, pDS: pathologic downstaging, PFS: Progression Free Survival, RARC: Robot-assisted Radical Cystectomy, RFS: Recurrence Free Surivival, RT: Radiotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Treatment algorithm for locally advanced urothelial bladder cancer

Future directions

Advances in other areas, such as biomarkers, have great potential to change and improve how these patients are managed. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), which has been used in various tumor types, has shown significant promise in bladder cancer. Dead tumor cells release DNA into the bloodstream which can be detected and utilized as a biomarker. ctDNA has been shown to be associated with disease burden and can predict progression and recurrence, often before traditional methods (i.e., imaging and routine lab work) detect recurrence. A recent meta-analysis highlighted the strengths of ctDNA in patients with MIBC. For example, ctDNA-positive state was significantly associated with poorer OS (HR 4.51), PFS (HR 4.5), and RFS (HR 6.56). In addition, clearance of ctDNA after treatment was a predictor of very favorable RFS (HR 0.24) [54]. In fact, although the previously discussed IMvigor010 trial was a negative trial, exploratory data showed that atezolizumab reduced the risk of death by roughly 40% in patients who were ctDNA positive after RC. This prompted the development of the prospective IMvigor011 trial to validate these findings. IMvigor011 is a phase 3, randomized, double-blinded study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant atezolizumab compared with placebo in patients with MIBC who are ctDNA positive and are at high risk of recurrence following RC[55]. Thus, this test has the potential to help understand the prognosis on a more detailed level and to help target the “window” of minimal residual disease.

Another point to consider in future clinical trials is the potential role of Nectin-4 as a surrogate marker for treatment response to EV. A recent study on tissue specimens from patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma revealed that 26% of the cohort had Nectin-4 amplifications. Notably, 96% of these patients showed an objective response to EV (82% partial and 14% complete), compared to only 32% (29% partial and 3% complete) in patients without Nectin-4 amplification [56].

Improved imaging modalities are also needed as conventional imaging can be imperfect for staging, particularly in identifying N + disease. Previous studies have reported that up to 25% of patients with pathologic N + disease did not have abnormal lymphadenopathy on pre-RC imaging [57]. Conventional fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has been shown to be better at detecting metastatic lesions compared to conventional imaging [58] and other radiotracers have also been evaluated. For example, a study assessing an early experience with 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET, a novel fibroblast activation protein (FAP) binder, found that it was highly sensitive in patients with localized and metastatic disease. It was also found to be effective in identifying metastatic lesions across a variety of anatomic sites, including subcentimeter lymph nodes that would not have raised suspicion on conventional imaging. In 3 patients, 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET helped to identify false-positive findings on conventional FDG PET and false-negative findings on conventional cross-sectional imaging [59]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also shown promise in bladder cancer, although more so in helping to distinguish non-muscle invasive from muscle-invasive tumors [60]. The VI-RADS system has been developed for standardized reporting of MRI findings in bladder cancer [61].

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, locally advanced bladder cancer can be challenging to accurately stage and manage, with high rates of recurrence and overall poor prognosis. The gold standard remains NAC followed by RC, however multiple ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the utility of immunotherapy or other chemotherapy agents in the neoadjuvant setting. Some patients will also require adjuvant therapy, either with chemotherapy or immunotherapy and multiple trials have been completed in this space. In addition, several trials are also investigating combinations of treatments such as the addition of immunotherapy to chemoRT [62] and bladder preservation with immuno-RT in those with MIBC and a clinical CR after neoadjuvant therapy (SWOG 2427/BRIGHT trial). However, because accurate staging remains difficult in these patients (both initially and after neoadjuvant therapy), bladder preservation in those with a clinical CR after neoadjuvant therapy is not currently recommended due to high rates of metastases and increased mortality risk in those delaying RC [42].

Several innovations allowing for more personalized approaches to the management of these patients, including biomarkers such as ctDNA and advances in imaging, have been developed with the goal of improving staging accuracy and offering important prognostic information. Similarly, genome sequencing in variant histology may also help to guide treatment decisions in this understudied group, especially as targeted therapies continue to be developed [63]. However, it is important to note their limitations including potential discordance in tumor molecular profiles between the primary site and metastases [64].

In conclusion, significant work remains to improve oncologic outcomes in patients with locally advanced bladder cancer and this will likely include personalized approaches including novel biomarkers and clinical trials.

Author contributions

DE wrote main manuscript text and made all edits. SD provided supervision, reviewed the manuscript and provided edits. MZ and CD reviewed the manuscript and provided edits.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A (2024) Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 74(1):12–49. 10.3322/caac.21820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holzbeierlein J, Bixler BR, Buckley DI et al (2017) Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/SUO guideline (2017; amended 2020, 2024. The Journal of urology 212(1):3–10. 10.1097/JU.0000000000003981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daneshmand S (2013) Determining the role of cystectomy for high-grade T1 urothelial carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 40(2):233–247. 10.1016/j.ucl.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R et al (2001) Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol 19(3):666–675. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karakiewicz PI, Shariat SF, Palapattu GS et al (2006) Nomogram for predicting disease recurrence after radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol 176(4):1354–1362. 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postoperative Nomogram Predicting Risk of Recurrence After Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer (2006) JCO 24(24):3967–3972. 10.1200/jco.2005.05.3884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozanski AT, Benson CR, McCoy JA et al (2015) Is exam under anesthesia still necessary for the staging of bladder cancer in the era of modern imaging? Bladder Cancer 1(1):91–96. 10.3233/BLC-150006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czech AK, Gronostaj K, Fronczek J (2023) Diagnostic accuracy of bimanual palpation in bladder cancer patients undergoing cystectomy: a prospective study. Urol Oncol 41(9):390.e27-390.e33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen SS, Lerner SP, Muezzinoglu B, Truong LD, Amiel G, Wheeler TM (2006) Prostatic involvement by transitional cell carcinoma in patients with bladder cancer and its prognostic significance. Hum Pathol 37(6):726–734. 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner SP, Colen J, Shen S (2008) Prostatic biology, histologic patterns and clinical consequences of transitional cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol 18(5):508–512. 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32830b86f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM et al (2003) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 349(9):859–866. 10.1056/nejmoa022148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Collaboration of Trialists on behalf of the Medical Research Council Advanced Bladder Cancer Working Party (now the National Cancer Research Institute Bladder Cancer Clinical Studies Group), the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Group, the Australian Bladder Cancer Study Group, the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (2011) Finnbladder, Norwegian bladder cancer study Group, and club urologico Espanol de Tratamiento Oncologic. International phase III trial assessing neoadjuvant Cisplatin, Methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for Muscle-Invasive bladder cancer: Long-Term results of the BA06 30894 trial. JCO 29(16):2171–2177. 10.1200/jco.2010.32.3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neoadjuvant cisplatin (1999) methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a randomised controlled trial. International collaboration of trialists. Lancet 354(9178):533–540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaig TW, Tangen CM, Daneshmand S et al (2021) A randomized phase II study of coexpression extrapolation (COXEN) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for bladder cancer (SWOG S1314; NCT02177695). Clin Cancer Res 27(9):2435–2441. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfister C, Gravis G, Flechon A (2024) Perioperative dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (VESPER): survival endpoints at 5 years in an open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 25(2):255–264. 10.1016/s1470-2045(23)00587-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfister C, Gravis G, Fléchon A et al (2022) Dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin or gemcitabine and cisplatin as perioperative chemotherapy for patients with nonmetastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of the GETUG-AFU V05 VESPER trial. J Clin Oncol 40(18):2013–2022. 10.1200/JCO.21.02051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zargar H, Shah JB, van Rhijn BW et al (2018) Neoadjuvant dose dense MVAC versus gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with cT3-4aN0M0 bladder cancer treated with radical cystectomy. J Urol 199(6):1452–1458. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stormoen DR, Joensen UN, Daugaard G et al (2024) Glomerular filtration rate measurement during platinum treatment for urothelial carcinoma: optimal methods for clinical practice. Int J Clin Oncol 29(3):309–317. 10.1007/s10147-023-02454-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho FL, Zeymo A, Egan J et al (2020) Determinants of neoadjuvant chemotherapy use in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Investig Clin Urol 61(4):390–396. 10.4111/icu.2020.61.4.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powles T, Rosenberg JE, Sonpavde GP et al (2021) Enfortumab vedotin in previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384(12):1125–1135. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powles T, Valderrama BP, Gupta S et al (2024) Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab in untreated advanced urothelial cancer. N Engl J Med 390(10):875–888. 10.1056/NEJMoa2312117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Donnell PH, Hoimes CJ, Rosenberg JE et al (2024) Study EV-103: neoadjuvant treatment with enfortumab Vedotin monotherapy in cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC)—2-year event-free survival and safety data for cohort H. JCO 42(16suppl):4564–4564. 10.1200/jco.2024.42.16_suppl.4564 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Necchi A, Bedke J, Galsky MD et al (2023) Phase 3 KEYNOTE-905/EV-303: perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) or pembro + enfortumab Vedotin (EV) for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). JCO 41(6suppl):TPS585–TPS585. 10.1200/jco.2023.41.6_suppl.tps585 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoimes CJ, Loriot Y, Bedke J et al (2023) Perioperative enfortumab vedotin (EV) plus pembrolizumab (pembro) versus chemotherapy in cisplatin-eligible patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC): phase 3 KEYNOTE-B15/EV-304. JCO 41(6suppl):TPS588–TPS588. 10.1200/jco.2023.41.6_suppl.tps588 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powles T, Catto JWF, Galsky MD et al (2024) Perioperative durvalumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 391(19):1773–1786. 10.1056/nejmoa2408154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daneshmand S, Nazemi A (2020) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in variant histology bladder cancer: current evidence. Eur Urol Focus 6(4):639–641. 10.1016/j.euf.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooke I, Abou Heidar N, Mahmood AW et al (2024) The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with variant histology muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing robotic cystectomy: data from the international robotic cystectomy consortium. Urol Oncol 42(4):117. .e17-117.e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon WA, Seo HK, Song G, Lee MK, Park WS (2025) Advances in therapy for urothelial and non-urothelial subtype histologies of advanced bladder cancer: from etiology to current development. Biomedicines 13(1):86. 10.3390/biomedicines13010086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Heijden MS, Sonpavde G, Powles T et al (2023) Nivolumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin in advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 389(19):1778–1789. 10.1056/NEJMoa2309863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powles T, Park SH, Voog E et al (2020) Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 383(13):1218–1230. 10.1056/nejmoa2002788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You C, Cheng L, Fang Q et al (2024) Comparative evaluation of reproductive organ-preserving versus standard radical cystectomy in female: a meta-analysis and systematic review of perioperative, oncological, and functional outcomes. Surg Endosc 38(9):5041–5052. 10.1007/s00464-024-11074-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SH, Wang S, Metcalf MR et al (2022) Safety and efficacy of reproductive organ-sparing radical cystectomy in women with variant histology and advanced stage. Clin Genitourin Cancer 20(1):60–68. 10.1016/j.clgc.2021.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parekh DJ, Reis IM, Castle EP (2018) Robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer (RAZOR): an open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 391(10139):2525–2536. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30996-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy AG, Sparks AD, Darwish C, Whalen MJ (2021) Oncologic outcomes for robotic vs. open radical cystectomy among locally advanced and node-positive patients: analysis of the National Cancer Database. Clin Genitourin Cancer 19(6):547–553. 10.1016/j.clgc.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catto JWF, Khetrapal P, Ricciardi F et al (2022) Effect of robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion vs open radical cystectomy on 90-day morbidity and mortality among patients with bladder cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 327(21):2092–2103. 10.1001/jama.2022.7393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakozaki K, Kikuchi E, Ogihara K et al (2021) Significance of prophylactic urethrectomy at the time of radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 51(2):287–295. 10.1093/jjco/hyaa168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelles JL, Konety BR, Saigal C, Pace J, Lai J (2008) Urologic diseases in America Project. Urethrectomy following cystectomy for bladder cancer in men: practice patterns and impact on survival. J Urol 180(5):1933–1936 discussion 1936–1937. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J, Lee CU, Chung JH et al (2024) Impact of urinary diversion type on urethral recurrence following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: propensity score matched and weighted analyses of retrospective cohort. Int J Surg 110(2):700–708. 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunocilla E, Pernetti R, Schiavina R et al (2013) The number of nodes removed as well as the template of the dissection is independently correlated to cancer-specific survival after radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int Urol Nephrol 45(3):711–719. 10.1007/s11255-013-0461-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gschwend JE, Heck MM, Lehmann J (2019) Extended versus limited lymph node dissection in bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy: survival results from a prospective, randomized trial. Eur Urol 75(4):604–611. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerner SP, Tangen C, Svatek RS et al (2024) Standard or extended lymphadenectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 391(13):1206–1216. 10.1056/NEJMoa2401497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zahir M, Doshi C, Escobar D, Daneshmand S (2025) Bladder preservation: an overview of novel prospects and limitations. Int J Urol iju70022. 10.1111/iju.70022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta S, Hensley PJ, Li R et al (2025) Bladder preservation strategies in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: recommendations from the International Bladder Cancer Group. European urology. 10.1016/j.eururo.2025.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlotta AR, Ballas LK, Niemierko A et al (2023) Radical cystectomy versus trimodality therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a multi-institutional propensity score matched and weighted analysis. Lancet Oncol 24(6):669–681. 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00170-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackey JD, Atieh K (2024) Chemoradiation versus cystectomy for locally advanced bladder cancer: a global, propensity-matched retrospective cohort study. JCO 42(16suppl):e16603. 10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.e16603 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carriere P, Alhalabi O, Gao J et al (2024) Bladder-preserving radiation therapy for patients with locally advanced and node-positive bladder cancer. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 49:100866. 10.1016/j.ctro.2024.100866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krasnow RE, Drumm M, Roberts HJ et al (2017) Clinical outcomes of patients with histologic variants of urothelial cancer treated with trimodality bladder-sparing therapy. Eur Urol 72(1):54–60. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellmunt J, Hussain M, Gschwend JE et al (2021) Adjuvant atezolizumab versus observation in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor010): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 22(4):525–537. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00004-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yafi FA, Aprikian AG, Chin JL et al (2011) Contemporary outcomes of 2287 patients with bladder cancer who were treated with radical cystectomy: a Canadian multicentre experience. BJU Int 108(4):539–545. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matulay JT, Narayan VM, Kamat AM (2019) Clinical and genomic considerations for variant histology in bladder cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 21(3):23. 10.1007/s11912-019-0772-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Advanced Bladder Cancer (ABC) Meta-analysis Collaborators Group (2022) Adjuvant chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Eur Urol 81(1):50–61. 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bajorin DF, Witjes JA, Gschwend JE et al (2021) Adjuvant nivolumab versus placebo in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384(22):2102–2114. 10.1056/NEJMoa2034442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apolo AB, Ballman KV, Sonpavde G et al (2025) Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus observation in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 392(1):45–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa2401726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao X, Qi W, Li J et al (2025) Prognostic and predictive role of circulating tumor DNA detection in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 25(1):75. 10.1186/s12935-025-03707-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson-Spence F, Toms C, O’Mahony LF et al (2023) IMvigor011: a study of adjuvant atezolizumab in patients with high-risk MIBC who are ctDNA + post-surgery. Future Oncol 19(7):509–515. 10.2217/fon-2022-0868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klümper N, Tran NK, Zschäbitz S et al (2024) Nectin4 amplification is frequent in solid tumors and predicts enfortumab Vedotin response in metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol 42(20):2446–2455. 10.1200/JCO.23.01983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rais-Bahrami S, Pietryga JA, Nix JW (2016) Contemporary role of advanced imaging for bladder cancer staging. Urologic Oncology: Seminars Original Investigations 34(3):124–133. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Civelek AC, Niglio SA, Malayeri AA et al (2021) Clinical value of 18FDG PET/MRI in muscle-invasive, locally advanced, and metastatic bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 39(11):787. .e17-787.e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koshkin VS, Kumar V, Kline B et al (2024) Initial experience with 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET imaging in patients with urothelial cancer. J Nucl Med 65(2):199–205. 10.2967/jnumed.123.266390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eusebi L, Masino F, Gifuni R et al (2023) Role of multiparametric-MRI in bladder cancer. Curr Radiol Rep 11(5):69–80. 10.1007/s40134-023-00412-5 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panebianco V, Narumi Y, Altun E et al (2018) Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for bladder cancer: development of VI-RADS (Vesical imaging-Reporting and data System). Eur Urol 74(3):294–306. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Hattum JW, de Ruiter BM, Oddens JR, Hulshof MCCM, de Reijke TM, Bins AD (2021) Bladder-sparing chemoradiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibition for locally advanced urothelial bladder cancer-a review. Cancers (Basel) 14(1):38. 10.3390/cancers14010038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chu CE, Chen Z, Whiting K et al (2025) Clinical outcomes, genomic heterogeneity, and therapeutic considerations across histologic subtypes of urothelial carcinoma. European Urology. 10.1016/j.eururo.2025.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clinton TN, Chen Z, Wise H (2022) Genomic heterogeneity as a barrier to precision oncology in urothelial cancer. Cell Rep 41(12):111859. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.IMvigor011 Bladder Cancer Trial Achieves Positive Results, with Signatera™ Strongly Predicting Adjuvant Immunotherapy Benefit. Natera, Inc. https://www.natera.com/company/news/imvigor011-bladder-cancer-trial-achieves-positive-results-with-signatera-strongly-predicting-adjuvant-immunotherapy-benefit/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.