Abstract

Nineteen Streptococcus suis type 2 isolates were evaluated for their virulence in pigs and mice. Of these, seven were determined to be highly virulent in pigs on the basis of clinical sign scores and gross pathology and histopathology results. Clinical sign scores correlated with gross pathology and histopathology scores at P equal to 0.004 and P equal to 0.009, respectively. The virulence of highly virulent isolates in pigs compared somewhat with virulence in mice, but the correlation was not significant. No correlation of virulence was noted among the moderately virulent and avirulent isolates in pigs and mice. Chromosomal DNAs from all S. suis isolates were evaluated by PstI, PvuII, EcoRI, and HaeIII restriction enzyme digestion followed by hybridization with a digoxigenin-11-dUTP-labeled cDNA probe transcribed from 16S and 23S rRNAs from Escherichia coli. The hybridization patterns (ribotypes) varied depending upon the enzyme used, but a significant number of isolates determined to be highly virulent in pigs had unique hybridization patterns compared with those of the moderately virulent and avirulent isolates (P = 0.002). In addition, hemolysin activity showed a high correlation to virulence (P = 0.00008) and ribotype (P = 0.002).

Streptococcus suis type 2 is an important pathogen of swine. It causes septicemia, arthritis, meningitis, encephalitis, and endocarditis and has been associated with pneumonia (29). S. suis type 2 is the serotype most often associated with disease in swine; however, not all type 2 isolates cause disease (34). Carrier rates have been shown to be as high as 100% (23).

Thiol-activated hemolysins have been implicated as major virulence factors for several bacteria (1, 9, 26). Hemolysins of S. suis type 2 with molecular masses of 54 and 62 kDa have recently been identified and characterized (8, 13, 17). Although S. suis hemolysin belongs to the thiol-activated family of toxins (16), the actual involvement of hemolysin in the virulence of this organism is unknown. In vitro hemolysin activity has been shown by a high percentage of S. suis strains collected from diseased pigs (18). Additional virulence factors of S. suis include a muramidase-release protein (MRP) and an extracellular protein factor (EF), which have been shown to be necessary for the full expression of virulence (35). Other virulence factors of S. suis such as capsule, fimbriae, and adhesins are not well characterized (12, 19, 27).

Several molecular biology-based methods have been used to characterize S. suis isolates. Twenty-three serotypes of S. suis (types 1 to 22 and type 1/2) were analyzed by determining the restriction fragment length of chromosomal DNA (21, 22). This method revealed the existence of genetic heterogeneity among fingerprints of serologically identical S. suis isolates. The use of patterns obtained by restriction enzyme digestion analysis followed by hybridization with rRNA (ribotyping) or DNA probes also has shown heterogeneity within and between S. suis serotypes (2, 15, 24, 32). Beaudoin et al. (2) also used ribotyping to investigate different types of infections to determine if different strains were associated with different types of infection and showed that most S. suis type 2 strains isolated from pigs with porcine septicemia were grouped within a single ribotyping profile. An association between ribotype and production of the virulence factors MRP and EF also has been shown in S. suis serotypes 1 and 2 (32). The purpose of this study was to determine if there are characteristics which could be used as indicators of the virulence of S. suis type 2 isolates in pigs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The 19 isolates of S. suis serotype 2 used in this study are listed in Table 1. Stock cultures were maintained on glass beads in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at −70°C. For animal inoculation studies, the isolates were grown on sheep blood agar plates (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) and a single colony was subcultured into Todd-Hewitt broth with 0.6% yeast extract (Difco) and incubated for 6 to 7 h at 37°C in 6% CO2. Cultures were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min, and the bacteria were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline to an optical density at 560 nm of 1.1. The cells were further concentrated fivefold, with the resulting suspension containing 1010 CFU per ml. Inocula were quantitated by a standard plate counting technique to confirm the challenge doses.

TABLE 1.

Virulence of 19 S. suis type 2 isolates in pigs and mice

| Strain | Source | Mouse virulence scoresa | Mouse virulence ratingsb | Pig virulence scoresa | Pig virulence ratingb | Hemolysin units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAH4 | Kansasc | 0.95 | AV | 1.1 | MV | 0 |

| 1933 | Kansas | 0.88 | AV | 2.5 | HV | 40 |

| AAH6 | Kansas | 0.95 | AV | 1.2 | MV | 0 |

| 94-1389 | Kansas | 1.25 | MV | 0.7 | MV | 0 |

| 95-7220 | Kansas | 1.08 | MV | 1.0 | MV | 0 |

| AAH5 | Kansas | 2.19 | MV | 1.5 | HV | 0 |

| 95-308 | Kansas | 2.34 | MV | 0.7 | MV | 0 |

| 95-16426 | Kansas | 2.53 | HV | 0.9 | MV | 0 |

| 5955A | Kansas | 2.80 | HV | 0.7 | MV | 0 |

| 95-16753 | Kansas | 3.0 | HV | 2.6 | HV | 90 |

| 89-3977B | Kansas | 3.0 | HV | 2.6 | HV | 150 |

| 95-8506 | Kansas | 2.5 | HV | 2.1 | HV | 30 |

| 95-13626 | Kansas | 2.7 | HV | 0.2 | AV | 0 |

| D930 | Englandd | 2.15 | MV | 1.6 | HV | 30 |

| DH5 | Minnesotae | 2.90 | HV | 2.8 | HV | 0 |

| 0891 | Canadaf | 2.45 | MV | 0.8 | MV | 0 |

| 94-623 | Canada | 1.54 | MV | 0.9 | MV | 0 |

| 89-999 | Canada | 2.7 | HV | 0.9 | MV | 0 |

| 89-1591 | Canada | 2.8 | HV | 0.6 | AV | 0 |

Clinical sign scores were determined by averaging the clinical sign scores per day per animal.

HV, highly virulent; MV, moderately virulent; AV, avirulent.

M. M. Chengappa, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University, Manhattan, provided all Kansas strains listed here.

E. D. Erickson, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

C. Pijoan, Department of Clinical and Population Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, St. Paul, Minn.

R. Higgins and M. Gottschalk, Université de Montréal, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec, Canada, provided all Canada strains listed here.

Hemolysin assay.

Hemolysin assays were carried out for each isolate as described previously (8). Briefly, colonies were harvested from tryptic soy agar (Difco) plates with cold RPMI 1640 (RPMI; GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, N.Y.), and the optical density at 560 nm was adjusted to 1.6. The suspension was incubated aerobically for 1 h at 40°C, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size nylon filter (Micron Separations Inc., Westboro, Mass.). Supernatants were kept on ice, and assays for hemolysin activity were conducted immediately.

One hundred-microliter aliquots of the hemolysin supernatants were added in triplicate to round-bottom, 96-well microtiter plates. One hundred microliters of 1% sheep erythrocytes was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h in 6% CO2. Unlysed erythrocytes were removed by centrifugation at 100 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a flat-bottom, 96-well microtiter plate for spectrophotometric analysis at A410. One hemolytic unit was defined as the highest dilution of supernatant that resulted in 50% hemolysis of 1 ml of 1% sheep erythrocytes.

Mice.

Seven-week-old BALB/c mice were used in this study. Groups of six mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of bacterial strain containing 10 times the 50% lethal dose determined for strain 89-3977B by a procedure described by Reed and Muench (30). Strain 89-3977B, a strain highly virulent for pigs, is the standard challenge strain used in our laboratory. Mice were observed daily for 7 days for morbidity and mortality. Clinical sign scores were assigned by using the following system: 3, death; 2, very sick, unable to move; 1, moderately sick; and 0, clinically normal. Mean clinical sign scores per isolate per day were used to determine virulence. Heart blood was taken for culture at the time of death to confirm infection.

Pigs.

Seventy-six high-health-status (20) barrows (maternal line, Newsham hybrids; age, 44 ± 1 days) were obtained from a closed herd initially populated with cesarean-derived pigs. No clinical signs of infectious disease were observed in the herd of origin 30 days prior to or 30 days following initiation of the experiment. Pigs were allotted by initial weight to 1 of 19 solid-sided polyethylene pens.

On day 1, blood was collected intravenously and rectal temperatures were taken. Each pig was then injected intravenously with 1 ml of a logarithmic-phase culture of the appropriate S. suis isolate containing approximately 1010 CFU as described above. Rectal temperatures and clinical signs based on lameness, depression, and central nervous system (CNS) disorders were recorded daily following inoculation. Each clinical sign was given a numerical score, as follows: 4, death; 3, severe signs of infection (recumbent and unable to stand); 2, moderate signs of infection (moderate lameness and/or CNS disorders; recumbent and reluctant to stand if provoked); 1, mild clinical signs of infection (slight lameness and/or CNS disorders; easily provoked to rise if recumbent); and 0, clinically normal. Blood was collected every other day postinoculation for leukocyte and fibrinogen analysis. One week after inoculation, the pigs were euthanized by electrocution for necropsy.

Tissues (brain, joint, lung, and heart) were collected for bacterial culture and histopathology. For histopathology, tissues were assigned scores of 0 for no tissue reaction, 1 for moderate tissue reaction, and 2 for severe tissue reaction. More specifically, histological lesions were graded on the basis of the degree of cellular infiltration, presence of fibrin, necrosis, and the level of inflammation present in that particular tissue.

Gross lesions were examined for severity of infection including meningitis, pneumonia, pleuritis, pericarditis, peritonitis, and synovitis. Scores indicating the type of lesion were given as follows: 0, no visible lesion; 1, minimal to mild lesion; and 2, moderate to severe lesion. Lesions were scored on the basis of an abnormal color and/or viscosity of fluid, swelling and/or organ discoloration, and the presence of fibrin in each respective organ.

Isolation of chromosomal DNA.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated as described previously (24). The DNA preparations were stored at 4°C until needed.

Restriction endonuclease digestion.

The DNA was digested for 4 to 5 h with four different restriction endonucleases (PstI, PvuII, HaeIII, and EcoRI) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Promega). The 20-μl digestion mixture consisted of DNA (3 μg), buffer (10×), enzyme (10 U), and water. Following restriction digestion, reactions were stopped by heating the solutions for 10 min at 65°C and then cooling for 5 min on ice.

Electrophoresis.

The digested fragments were separated in a horizontal gel containing 1% (wt/vol) agarose. Electrophoresis was done at room temperature at 40 V for 18 h. Digoxigenin-labeled DNA molecular weight marker II (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) was used as the molecular weight standard.

Southern blotting.

The gels were depurinated in 250 ml of 0.25 M HCl for 9 min and then rinsed three times in distilled water. The fragments were denatured by incubation in 250 ml of 0.5 M NaOH and 1.5 M NaCl for 30 min and were then neutralized in 250 ml of 0.5 M Tris-HCl with 1.5 M NaCl for at least 30 min. Fragments were transferred overnight to a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) by the method of Southern (33), UV cross-linked (GS Gene Linker; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.), and stored at 4°C until needed.

Probe preparation.

A nonradioactive labeling system (Genius System; Boehringer Mannheim) was used by incorporating digoxigenin-11-dUTP into first-strand cDNA. The cDNA was transcribed from a mixture of 16S and 23S rRNAs from Escherichia coli MRE600 by random priming with reverse transcriptase as described previously (5, 11). The labeling reaction mixture contained 38 μg of 16S and 23S rRNAs from E. coli in 194 μl of water, 40 μl of digoxigenin DNA labeling mixture, 50 μl of a random hexanucleotide, 50 μl (10,000 U) of reverse transcriptase, 100 μl of buffer supplied with the reverse transcriptase, and 6 μl of RNase inhibitor. The labeled probe was then purified as suggested by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim) and stored at −20°C until it was used.

Hybridization.

Prehybridization and hybridization were performed as specified by the manufacturer (Genius System; Boehringer Mannheim).

Statistical analysis.

Probability of dependence was determined by chi-square analysis and the Fisher exact two-tailed test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The virulence of the S. suis isolates was determined by taking the average clinical sign score per day per animal (Table 1). In pigs, seven of the isolates were rated highly virulent, 10 were moderately virulent, and 2 were avirulent. Of the 19 isolates tested in mice, 3 were avirulent, 7 were moderately virulent, and 9 were rated highly virulent. Correlation between S. suis virulence in mice and pigs was not statistically significant, although some agreement occurred among highly virulent isolates. Of the seven isolates that were highly virulent in pigs, four were highly virulent in mice, two were moderately virulent in mice, and one was avirulent in mice. A similar trend was seen among the moderately virulent isolates; however, both of the isolates that were avirulent in pigs were highly virulent in mice.

S. suis strains were isolated from all pigs at necropsy, most often from the brain (55 of the 76 pigs in the study), followed by the lung (33 of 76), joint (16 of 76), and heart (9 of 76). No significant correlation occurred among the numbers of S. suis strains isolated, the organ from which they were isolated, or the severity of disease in pigs (data not shown). However, isolation from the joint was most commonly associated with severe clinical signs. Eleven of the 16 pigs from which S. suis was isolated from the joint were infected with highly virulent isolates.

Clinical pathology data, including leukocyte counts and fibrinogen concentration, were evaluated. The average fibrinogen concentration increased postinoculation in all groups. Average postinoculation fibrinogen levels in groups receiving highly virulent isolates was 60% higher than the day 0 baseline average. The average for groups receiving the moderately virulent isolates increased 10%, and that for groups receiving the avirulent isolates increased an average of 1%. Leukocyte counts also increased, but the increases did not correlate with the severity of disease.

Gross pathology and histopathology ratings were based on the presence of meningitis, pneumonia or pleuritis, pericarditis, and arthritis. Isolates were rated as producing high, moderate, or low lesion scores. The gross pathology (P = 0.004) and histopathology (P = 0.009) scores for the pigs correlated with isolate virulence, on the basis of clinical sign scores, only for the animals receiving highly virulent isolates. No significant correlation occurred between virulence and pathology for animals receiving moderately or avirulent isolates.

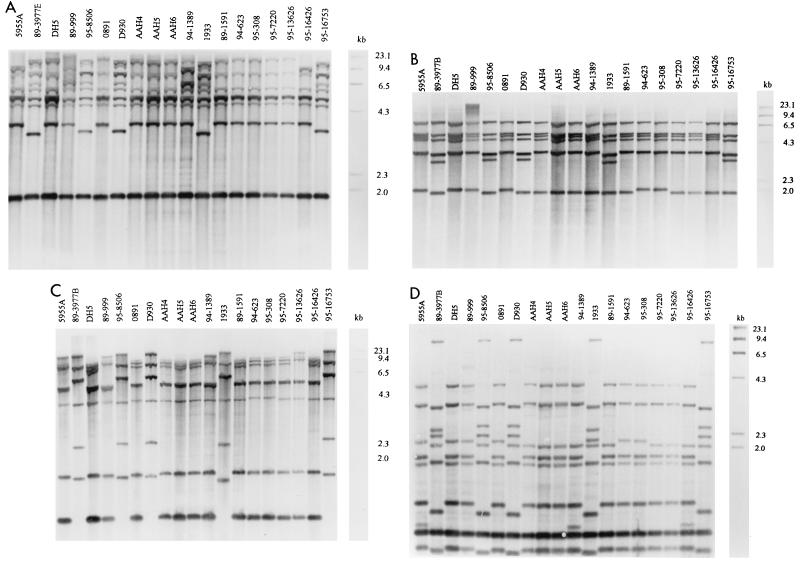

Ribotypes varied depending on the restriction enzyme used (Table 2). The PstI and PvuII digestions resulted in six and three distinct hybridization profiles, respectively (Fig. 1A and B). A significant majority of the virulent isolates fell within a single group (ribotype B) when their DNAs were cut with either enzyme (P = 0.002). The major differences between ribotype B and the remaining ribotypes in the PvuII digestion were the appearance of a fragment at ca. 3.5 kb and the loss of a fragment between 4.3 and 6.5 kb (Fig. 1B). The strains of ribotype B in the PstI digestion varied from strains of the other ribotypes mainly in a migration difference in a 3.6-kb band, which appeared at 3.9 kb in strains of the remaining ribotypes, and the presence of double versus a single fragment between 5.3 and 6.5 kb (Fig. 1A). HaeIII differentiated the isolates into 6 hybridization groups, and EcoRI resulted in further differentiation of the isolates into 10 different ribotypes. In both the HaeIII and EcoRI digestions, a significant number of the virulent isolates remained within unique groupings (P = 0.002). EcoRI and HaeIII digestions further differentiated the isolates that had been grouped together in ribotype B by PstI and PvuII digestions into three groups (ribotypes B, C, and D; Table 2). Only slight variations in fragment migrations are seen among these groups; however, prominent differences occurred between these and the remaining ribotypes. Groups B, C, and D all contained an extra fragment at ca. 2.8 kb and were missing the bottom fragment in the EcoRI digest (Fig. 1C). In the HaeIII digest, groups B, C, and D demonstrated an extra fragment at ca. 8.7 kb, were missing the fragment at 4.0 kb, and had extra fragments at ca. 2.2 and 2.5 kb. Additional differences in fragments of less than 2.0 kb were also obvious (Fig. 1D).

TABLE 2.

Classification of 19 S. suis type 2 isolates by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA hybridization

| Strain | Ribotype by digestion with the following enzymea:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PvuII | PstI | EcoRI | HaeIII | |

| 5955A | A | A | A | A |

| DH5b | A | C | A | E |

| 0891 | A | E | A | G |

| 94-623 | A | E | A | G |

| 89-999 | A | D | A | F |

| 95-308 | A | E | A | G |

| 89-3977Bb | B | B | B | B |

| 95-16753b | B | B | C | B |

| 95-8506b | B | B | C | D |

| 1933b | B | B | D | C |

| D930b | B | B | C | D |

| 95-16426 | C | A | F | E |

| AAH4 | C | E | E | G |

| 95-7220 | C | E | E | I |

| 89-1591 | C | E | E | I |

| 95-13626 | C | E | E | J |

| AAH6 | C | C | E | G |

| AAH5b | C | C | E | G |

| 94-1389 | C | F | F | J |

The letters under each restriction enzyme designate digestion patterns. Isolates with the same letters have the same digestion patterns.

Isolates highly virulent in pigs.

FIG. 1.

Hybridization patterns of digoxigenin-labeled cDNA probe with Southern-blotted restriction fragments of DNAs from 19 S. suis type 2 isolates. PstI (A), PvuII (B), EcoRI (C), and HaeIII (D) were the restriction enzymes used. The molecular weight marker (in kilobases) is digoxigenin-labeled DNA molecular weight marker II.

Hemolysin activity was detected in 5 of the 19 isolates (Table 1). All of the isolates positive for hemolysin activity also were rated highly virulent in pigs on the basis of clinical sign scores. Two of the highly virulent isolates did not secrete detectable hemolysin. Correlation between hemolysin production and virulence, on the basis of clinical sign scores, was significant at P equal to 0.0002. The hemolysin production and virulence correlation, on the basis of gross pathology (P = 0.08) and histopathology (P = 0.03) scores, was also significant for the isolates producing high pathology scores.

DISCUSSION

S. suis type 2 is a major cause of disease in pigs. However, the presence of S. suis in pigs is not a good indicator of disease. Even when carrier rates approach 100%, the prevalence of disease is generally no greater than 5% (6). Even after isolation and biochemical and serological characterization, it is still not clear whether an isolate is pathogenic (37). This study was designed to determine if certain parameters can be used to differentiate between virulent and avirulent S. suis type 2 isolates.

Mice have been used as a model for S. suis disease in pigs (3, 28, 39), and results generally indicate that virulence in mice is dose dependent. Recently, Vecht and associates (37) reported that the murine model is not compatible with the pig model for studying S. suis infections. In this study, no significant correlation in virulence between pigs and mice was seen; however, isolates that were highly virulent in pigs were often highly virulent in mice. Of the seven isolates that were highly virulent in pigs, four were highly virulent in mice, two were moderately virulent in mice, and one produced no visible signs of disease in mice. The virulence of moderately virulent and avirulent isolates showed no agreement between species. This is in disagreement with the results of other investigators who have shown that disease conditions in mice were similar to those observed in pigs (3). Inocula were standardized for all isolates to ensure that differences in virulence were not due to dose. Previous studies have often based virulence in pigs on information gathered when the strain was initially isolated, and subsequent studies have not taken into consideration possible changes in virulence as a result of storage and continued subculture. In this study, isolate virulence in both pigs and mice was based on data collected during this study and may explain differences between these and other results.

Clinical pathology results, although indicating the presence of active infections, also did not generate data that could be used to predict virulence. Both leukocyte counts and fibrinogen concentrations were elevated, and group averages postinoculation differed in a group-specific manner, but differences at any one collection were not sufficiently distinct among the groups to be indicators of virulence.

Isolation of S. suis at necropsy in conjunction with gross pathology and histopathology analyses is the benchmark for the diagnosis of S. suis infection. For pigs receiving highly virulent S. suis isolates, there was significant correlation between pathology and severity of clinical signs (P = 0.004). Isolation of S. suis alone was the least accurate predictor of severity of disease. Isolation from the brain, heart, and lungs indicated the ability of the isolates to invade but did not indicate the disease-causing potential of the strains.

DNA fingerprinting shows genomic differences between strains of the same species and has been used to show differences in strains within the same serotype of S. suis (21). Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of S. suis has been shown to be an effective tool for examining the natural history of S. suis disease (2). However, large numbers of DNA bands make comparisons difficult and unreliable (24). Ribotyping has been used to study a number of bacterial pathogens (4, 7, 11, 25, 38). One advantage of using this procedure with bacteria is the presence of evolutionarily highly conserved sequences, which can provide valuable taxonomic, diagnostic, and epidemiological information (14). Ribotyping has been used to show that some Listeria monocytogenes strains from a single environment may be more apt than others to cause disease (38). Okwumabua et al. (24) showed that S. suis virulence could be determined by ribotyping, and pathogenic strains of S. suis types 1 and 2 have also been recognized by a unique ribotyping profile (32).

The restriction endonucleases PvuII, PstI, EcoRI, and HaeIII all digested S. suis DNA in this study. As reported previously (2, 22, 24), a high degree of genomic heterogeneity occurs among S. suis type 2 isolates. In this study, striking differences in ribotype patterns are immediately apparent between the highly virulent and the avirulent and moderately virulent isolates. Much heterogeneity in ribotyping patterns is seen among moderately and avirulent isolates. Hybridization of both the PstI- and PvuII-digested fragments with the cDNA probe resulted in a single, unique hybridization profile for a majority of the virulent isolates. Five of the seven highly virulent isolates fell within this group (ribotype B). Digestion with EcoRI and HaeIII further differentiated the isolates from group B into three subgroups, and although the same isolates remained within these three unique subgroups, variation within the subgroups indicated differences between the isolates. The presence of unique hybridization patterns among highly virulent isolates remained, regardless of which enzyme was used. Beaudoin and associates (2) also showed homogeneity among isolates causing septicemia by restriction endonuclease patterns. In this study, all isolates with the unique restriction analysis profiles were isolated from pigs with clinical cases of infection at the Kansas State University Diagnostic Laboratory and were received from various geographical locations in Kansas from 1989 to 1995. This supports the previous suggestion of a clonal association with virulence (2). Two isolates that had been characterized as highly virulent by clinical sign scores did not fall within the unique ribotype groups. One isolate (isolate DH5) was recovered from the brain of a pig with meningitis in Minnesota (22), but in a subsequent challenge study, it did not produce disease (10). In this study, the DH5 isolate was the most virulent isolate tested on the basis of morbidity and mortality. The difference in virulence between the two studies may have been due to the route of inoculation (intravenous versus intranasal in the original challenge) or due to changes in virulence due to storage, subculture, or pig passage. The intravenous inoculation of S. suis type 2 has been shown to result in a higher incidence of disease in pigs when compared to that from the intranasal route of inoculation (5).

The virulence factors of S. suis are not well defined. Virulent S. suis type 2 isolates possess a MRP and EF that are both necessary for full expression of virulence by type 2 isolates (31, 35, 36). The DH5 isolate presents a unique MRP* EF− phenotype in which an MRP-like protein is produced (10). The fact that the DH5 isolate was recovered from a pig with meningitis and did not have the MRP+ EF+ phenotype suggests that other virulence factors are involved.

S. suis isolates also produce a thiol-activated hemolysin (8, 16), which has been implicated as a virulence factor in a number of bacteria (1, 9, 26); however, its role as a virulence factor in S. suis infection is not known. The in vitro production of hemolysin by S. suis strains isolated from diseased pigs suggests a correlation with disease (18), and protection studies with pigs (16) and mice (17) indicate that it is involved in protection. Although all 19 S. suis isolates exhibited α-hemolysis on sheep blood agar plates, quantitatable hemolysin activity was detected by the hemolysin assay in only 5 of the 19 S. suis type 2 isolates in this study. Interestingly, these five isolates are the same five isolates that fell within the unique ribotype groups, and all were rated highly virulent. This suggests that the amount of hemolysin produced, rather than the presence or absence of visible hemolysis on blood agar plates, may be an important virulence marker. Further study needs to be done with purified hemolysin to determine its exact role in the pathogenesis of disease. This and other studies indicate that it is an important virulence factor and is involved in protection against S. suis infections (16–18). While the use of a hemolysin assay in the diagnosis of S. suis is probably not feasible, work on the development of a hemolysin-containing vaccine needs to be done.

This study also indicates that ribotype patterns and hemolysin production can be used to identify highly virulent S. suis type 2 isolates. In spite of heterogeneity among S. suis isolates, homogeneity among the virulent isolates suggests that ribotyping may be useful in the diagnosis of highly virulent S. suis type 2 infections and in studying the epidemiology of S. suis type 2 disease.

Footnotes

Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station contribution no. 97-413-J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson B R, van Epps D F. Suppression of chemotactic activity of human neutrophils by streptolysin O. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:353–359. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaudoin M, Harel J, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Frenette M. Molecular analysis of isolates of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 by restriction-endonuclease-digested DNA separated on SDS-PAGE and by hybridization with rDNA probe. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2639–2645. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaudoin M, Higgins R, Harel J, Gottschalk M. Studies on a murine model for evaluation of virulence of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90011-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg H M, Keihlbauch J A, Wachsmuth I K. Molecular epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infections: use of chromosomal DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2368–2374. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2368-2374.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifton-Hadley F A. Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clifton-Hadley F A. The epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and control of Streptococcus suis type 2 infection. In: McKean J D, editor. Proceedings of the American Association of Swine Practitioners. Minn: American Association of Swine Practitioners; 1986. pp. 471–491. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colding H, Bangsborg J, Fiehn J, Bennekov T, Bruun B. Ribotyping for differentiating Flavobacterium meningosepticum isolates from clinical and environmental sources. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:501–505. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.501-505.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feder I, Chengappa M M, Fenwick B, Rider M, Staats J. Partial characterization of Streptococcus suis type 2 hemolysin. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1256–1260. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1256-1260.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaillard J L, Berchee P, Sansonetti P. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986;52:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galina L, Pijoan C, Sitjar M, Christianson W T, Rossow K, Collins J E. Interaction between Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in specific pathogen-free piglets. Vet Rec. 1994;134:60–64. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.3.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerner-Smith P. Ribotyping of Acinetobacter calcoaceiticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2680–2685. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2680-2685.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottschalk M G, Lebrun A, Jacques M, Higgins R. Hemagglutination properties of Streptococcus suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2156–2158. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2156-2158.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschalk M G, Lacouture S, Dubreuil J D. Characterization of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 haemolysin. Microbiology. 1995;141:189–195. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimont F, Grimont P A D. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene restriction patterns as potential taxonomic tools. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1986;137B:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harel J, Higgins R, Gottschalk M, Bigras-Poulin M. Genomic relatedness among reference strains of different Streptococcus suis serotypes. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:259–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs A A, van den Berg A J, Loeffen P L. Protection of experimentally infected pigs by suilysin, the thiol-activated haemolysin of Streptococcus suis. Vet Rec. 1996;139:225–228. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.10.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs A A C, Loeffen P L W, van den Berg J G, Storm P K. Identification, purification, and characterization of a thiol-activated hemolysin (suilysin) of Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1742–1748. doi: 10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00034458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs A A C, van den Berg A J G, Baars J C, Nielsen B, Johannsen L W. Production of suilysin, the thiol-activated haemolysin of Streptococcus suis, by field isolates from diseased pigs. Vet Rec. 1995;137:295–296. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.12.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacques M, Gottschalk J, Foiry B, Higgins R. Ultrastructural study of surface components of Streptococcus suis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2833–2838. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2833-2838.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madec F, Kobisch M, Leforban Y. An attempt at measuring health in nucleus and multiplier pig farms. Livest Prod Sci. 1993;34:281. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(93)90113-V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogollon J D, Pijoan C, Murtaugh M P, Kaplan E L, Collins J E, Cleary P P. Characterization of prototype and clinically defined strains of Streptococcus suis by genome fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2462–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2462-2466.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mogollon J D, Pijoan C, Murtaugh M P, Collins J E, Cleary P P. Identification of epidemic strains of Streptococcus suis by genomic fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:782–787. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.4.782-787.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mwaniki C G, Robertson I D, Trott D J, Atyeo R F, Lee B J, Hampson D J. Clonal analysis and virulence of Australian isolates of Streptococcus suis type 2. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:321–334. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005175x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okwumabua O, Staats J, Chengappa M M. Detection of genomic heterogeneity in Streptococcus suis isolates by DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms of rRNA genes (ribotyping) J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:968–972. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.968-972.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okwumabua O, Tan Z, Staats J, Oberst R D, Chengappa M M. Ribotyping to differentiate Fusobacterium necrophorum subsp. necrophorum and F. necrophorum subsp. funduliforme isolated from bovine ruminal contents and liver abscesses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:469–472. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.469-472.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paton J C, Ferrante A. Inhibition of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte respiratory burst, bactericidal activity, and migration by pneumolysin. Infect Immun. 1983;42:1212–1216. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1212-1216.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quessy S, Dubreuil J D, Caya M, Letourneau R, Higgins R. Increase in capsular material thickness following in vivo growth of virulent Streptococcus suis serotype 2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quessy S, Dubreuil J D, Caya M, Higgins R. Discrimination of virulent and avirulent Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 isolates from different geographical origins. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1975–1979. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1975-1979.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reams R Y, Glickman L T, Harrington D D, Thacker H L, Bowersock T L. Streptococcus suis infection in swine: a retrospective study of 256 cases. Part II. Clinical signs, gross and microscopic lesions, and coexisting microorganisms. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6:326–334. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith H E, Reek F H, Vecht U, Gielkens A L J, Smits M A. Repeats in an extracellular protein of weakly pathogenic strains of Streptococcus suis type 2 are absent in pathogenic strains. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3318–3326. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3318-3326.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith H E, Rijnburger M, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Wisselink H J, Vecht U, Smits M A. Virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and highly virulent strains of Streptococcus suis serotype 1 can be recognized by a unique ribotype profile. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1049–1053. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1049-1053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vecht U, Arends J P, van der Molen E J, van Leengoed L A M G. Differences in virulence between two strains of Streptococcus suis type II after experimentally induced infection of newborn germ-free pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:1037–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vecht U, Wisselink H J, Jellema M L, Smith H E. Identification of two proteins associated with virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3156–3162. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3156-3162.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vecht U, Wisselink H J, van Dijk J E, Smith H E. Virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2 strains in newborn germfree pigs depends on phenotype. Infect Immun. 1992;60:550–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.550-556.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vecht U, Wisselink H J, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Smith H E. Characterization of virulence of the Streptococcus suis serotype 2 reference strain Henrichsen S 735 in newborn gnotobiotic pigs. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:125–136. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiedmann M, Bruce J L, Knorr R, Bodis M, Cole E M, McDowell C I, McDonough P L, Blatt C A. Ribotype diversity of Listeria monocytogenes strains associated with outbreaks of listeriosis in ruminants. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1086–1090. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1086-1090.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams A E, Blakemore W F, Alexander T J L. A murine model of Streptococcus suis type 2 meningitis in pigs. Res Vet Sci. 1988;45:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]