Abstract

The high readmission rate of bipolar disorder (BD) has imposed a heavy burden on the country and patients. Current studies mainly examine readmission influence factors but neglect risk prediction models. This study aims to develop a prediction model requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions (RUPR) within 1 year of BD. We screened the third people’s hospital of tianshui inpatients between January 1, 2021 and November 10, 2023 via hospital records and phone follow-ups, collecting required participant data. Based on their demographic and scale score, multiple variable logistic regression analysis was used to develop a nomogram-based prediction model. The study included 448 cases with 153 events. The analysis results show that group comparison revealed a significant difference in gender distribution, age stratification, comorbid chronic somatic diseases (CSD), partnered status (PS), social support rating scale (SSRS) scores, insight and treatment attitude questionnaire (ITAQ) scores, modified overt aggression scale (MOAS) scores. The result of multiple variable logistic regression analysis indicates that male gender and comorbid CSD increased readmission risk; Age > 60 years decreased risk; Higher MOAS scores, lower SSRS scores and ITAQ scores were significantly associated with elevated readmission risk. Model evaluation demonstrated that area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.85(95% CI 0.81–0.89) ; Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2 = 6.15, P = 0.63) indicates a good fit. This prediction model helps identify high-risk cases and simplifies BD management.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Readmission, Prediction model

Subject terms: Diseases, Risk factors

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe lifelong psychiatric condition afflicting 1–2% of the global population, characterized by recurrent depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes with high relapse rates and significant functional impairment1,2. Symptomatic relapse not only drives unplanned readmissions but also contributes to elevated suicide risks, occupational impairment, and reduced quality of life3,4. In Taiwan province of China, BD reached a 47.6% readmission rate within 1 year, aligning with global trends where reported failure rates of 39–52% per year during various maintenance treatments in bipolar disorder patients5,6, imposing profound fiscal and healthcare system burden and strain.

Chinese research demonstrates deinstitutionalization approaches do not lower readmission rates in schizophrenia cases, showing increasing rates in China and globally7. This pattern likely also occurs in Chinese BD patients, requiring urgent identification of preventable risks for unplanned readmissions. Research links BD readmissions to higher suicide risks, disability, job loss, and poorer life quality. Current studies mainly examine readmission influence factors but neglect risk prediction models8.

To address this gap, this study utilized retrospective clinical records of BD patients to pinpoint readmission risk factors and develop a clinically implementable prediction model for requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions (RUPR) within 1 year after discharge, aiming to identify key risk factors to establish a high recurrence period evidence-based evidence for early intervention in high-risk individuals.

Materials and methods

Research subjects

We screened the third people’s hospital of tianshui all BD inpatients between January 1, 2021 and November 10, 2023 via hospital records and phone follow-ups, collecting required baseline data.

Inclusion criteria: ICD-10 bipolar disorder diagnosis; Hospital admission at any age. Exclusion criteria: Patients with missing any non-scale data; Substance use disorders (excluding tobacco) or psychotic comorbidities; Major organ severe diseases (cardiac/cerebral/renal); Insufficient records (e.g., homeless populations); Involving judicial criminal cases. Protocol-specific exclusions: Elective readmission after non-clinical discharge; Length of stay (LOS) ≤ 72 h (emergency observation).

Chinese studies report 47% annual readmission rates in BD patients5. Sample size.

With parameters: readmission probability (P = 47%), α = 0.05 (two-sided), δ = 0.05, initial calculation yielded n = 383, with 5–10% attrition adjustment, target enrollment became 402–423, final analytical sample met requirements (n = 448).

Research tools and methods

Requiring unplanned psychiatric readmission definitions

BD patients achieving symptom remission may face relapse-related readmissions within 1 year post-discharge. These unplanned readmissions require matching primary diagnoses to index admissions, demonstrating temporal unpredictability that distinguishes them from scheduled returns or administrative discharges.

Variable definitions

Variable definitions followed previous studies9,10: Partnered Status (PS) : Marital status without spouse at admission (unmarried, divorced, widowed, or separated); Minder: Unpaid responsible caregivers (spouses, parents, children, siblings, relatives); Chronic Somatic Diseases (CSD): Diagnosed and treated medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia).

Scale scoring method

We retrieved discharge scale scores directly from electronic medical records (EMR). For missing scale data, two authors collected separately scores through (averaging of discordant ratings): Structured reviewing documented clinical conditions in the EMR and standardized telephone assessments with patients.

Statistical methods

Data analysis were performed using R version 4.3.3, along with Zstats 1.0 (www.zstats.net). Non-normally distributed continuous variables were described using medians (interquartile ranges) and analyzed with Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies (percentages) and assessed via Pearson χ2 tests. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analyses were included in multiple variable logistic regression analysis to develop a nomogram-based prediction model. Multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIF, > 2.5 indicated significant collinearity). Model performance was validated by: Discriminative ability: Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC); Goodness-of-fit: Hosmer–Lemeshow (H-L) test; Consistency: Calibration plots; Clinical utility: Decision curve analysis (DCA).

Results

Comparison of baseline characteristics

Among 448 patients within one-year post-discharge, 153 (34.2%) required relapse-related readmissions. Demographic analysis revealed: Male predominance (74.5%, n = 114); Working-age prevalence (84.3% aged 20–60 years); Low comorbidity burden (68.0% without chronic conditions); High unpartnered rate (51.6%). Baseline comparisons demonstrated statistically significant intergroup differences (P < 0.05) in: Gender distribution, Age stratification, comorbid CSD, PS, Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) scores, Insight and Treatment Attitude Questionnaire (ITAQ) scores, Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| Variables | Sort | Total (n = 448) | NNR group (n = 295) | NR group (n = 153) | Statistic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | ||||||

| Gender, n(%) | χ2 = 12.37 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 164 (36.61) | 125 (42.37) | 39 (25.49) | |||

| Male | 284 (63.39) | 170 (57.63) | 114 (74.51) | |||

| Age, n(%) | χ2 = 7.89 | 0.048 | ||||

| Age ≤ 20 | 25 (5.58) | 13 (4.41) | 12 (7.84) | |||

| 20 < age ≤ 40 | 204 (45.54) | 125 (42.37) | 79 (51.63) | |||

| 40 < age ≤ 60 | 169 (37.72) | 119 (40.34) | 50 (32.68) | |||

| 60 < age | 50 (11.16) | 38 (12.88) | 12 (7.84) | |||

| Chronic somatic diseases, {CSD, n(%)} | χ2 = 5.30 | 0.021 | ||||

| No | 334 (74.55) | 230 (77.97) | 104 (67.97) | |||

| Yes | 114 (25.45) | 65 (22.03) | 49 (32.03) | |||

| Educational background, {EB, n(%)} | χ2 = 0.04 | 0.846 | ||||

| HSB | 349 (77.90) | 229 (77.63) | 120 (78.43) | |||

| CA | 99 (22.10) | 66 (22.37) | 33 (21.57) | |||

| Partnered status, {PS, n(%)} | χ2 = 23.35 | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 163 (36.38) | 84 (28.47) | 79 (51.63) | |||

| Yes | 285 (63.62) | 211 (71.53) | 74 (48.37) | |||

| Minder, n(%) | χ2 = 0.00 | 0.959 | ||||

| SIF | 422 (94.20) | 278 (94.24) | 144 (94.12) | |||

| Other | 26 (5.80) | 17 (5.76) | 9 (5.88) | |||

| Family history, {FH, n(%)} | χ2 = 1.05 | 0.305 | ||||

| No | 338 (75.45) | 227 (76.95) | 111 (72.55) | |||

| Yes | 110 (24.55) | 68 (23.05) | 42 (27.45) | |||

| Scale | ||||||

| Social support rating scale, {SSRS, M (Q1, Q3)} | Z = − 6.20 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 35.00 (30.00, 39.00) | 36.00 (33.00, 40.00) | 32.00 (28.00, 36.00) | ||||

| Insight and treatment attitudes questionnaires, {ITAQ, M (Q1, Q3)} | Z = − 8.02 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 10.00 (7.75, 12.00) | 11.00 (9.00, 12.00) | 8.00 (5.00, 11.00) | ||||

| Modified overt aggression scale,{MOAS, M (Q1, Q3)} | Z = − 3.02 | 0.003 | ||||

| 4.00 (2.00, 6.00) | 4.00 (1.00, 5.00) | 5.00 (2.00, 7.00) | ||||

| Barratt impulsiveness scale, {BIS, M (Q1, Q3)} | Z = − 1.21 | 0.226 | ||||

| 46.70 (33.30, 55.00) | 46.70 (33.30, 54.20) | 47.50 (33.30, 56.70) | ||||

Z: Mann-Whitney test, χ2: Chi-square test, M Median, Q1 1st Quartile, Q3 3st Quartile.

NR need for readmission; NNR no need for readmission; CSD chronic somatic diseases; EB educational background; PS partnered status; HSB high school or below; CA college or above; SIF spouse or immediate family; FH family history; SSRS social support rating scale; ITAQ insight and treatment attitudes questionnaires; MOAS modified overt aggression scale; BIS barratt impulsiveness scale.

Significant values are in bold.

Multiple variable logistic regression analysis and prediction models development

Multicollinearity analysis revealed VIF ranging 1.150–1.541 (all < 2.5), indicating no significant collinearity. All variables with significant differences (gender, age, CSD, PS, SSRS, ITAQ, MOAS) were included in backward elimination multiple variable logistic regression analysis. Key findings: Increased readmission risk: Male gender, comorbid CSD; Decreased risk: Age > 60 years; Higher MOAS scores, lower SSRS scores, and lower ITAQ scores were significantly associated with elevated readmission risk. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Multiple variable logistic regression analysis results.

| Variables | Sort | Multiple variable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | OR (95%CI) | ||

| Intercept | 3.81 | < 0.001 | 45.04 (7.91–256.55) | |

| Gender | Female | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Male | 1.60 | < 0.001 | 4.98 (2.65–9.35) | |

| Age | Age ≤ 20 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 20 < Age ≤ 40 | − 0.40 | 0.462 | 0.67 (0.23–1.95) | |

| 40 < Age ≤ 60 | − 0.72 | 0.238 | 0.49 (0.15–1.61) | |

| 60 < Age | − 1.72 | 0.022 | 0.18 (0.04–0.78) | |

| CSD | No | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Yes | 0.73 | 0.018 | 2.08 (1.14–3.82) | |

| PS | No | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Yes | − 0.54 | 0.079 | 0.58 (0.32–1.06) | |

| SSRS | − 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | |

| ITAQ | − 0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | |

| MOAS | 0.15 | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.07–1.27) | |

NR Need for readmission; NNR no need for readmission; CSD chronic somatic diseases; PS partnered status; SSRS social support rating scale; ITAQ insight and treatment attitudes questionnaires; MOAS modified overt aggression scale.

Significant values are in bold.

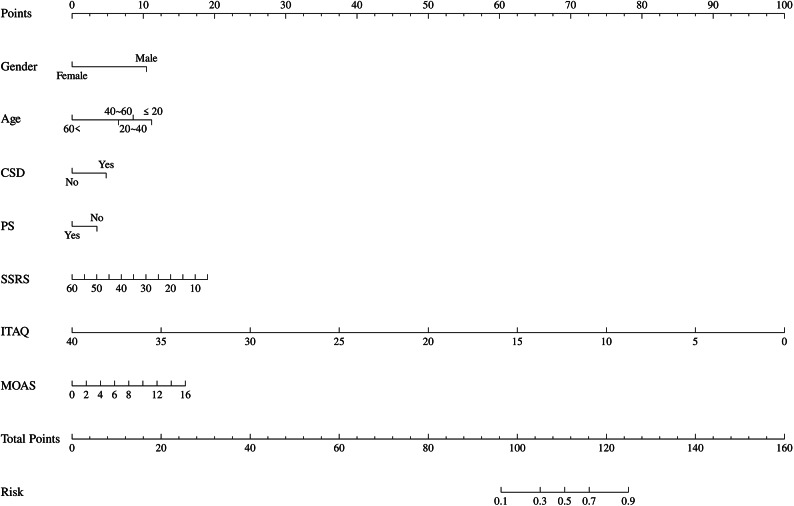

The nomogram prediction model incorporated these predictors, with total scores corresponding to individualized readmission probabilities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Nomogram prediction model of requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions (RUPR) within 1 year with all predictors.

Performance evaluation and clinical application of prediction models

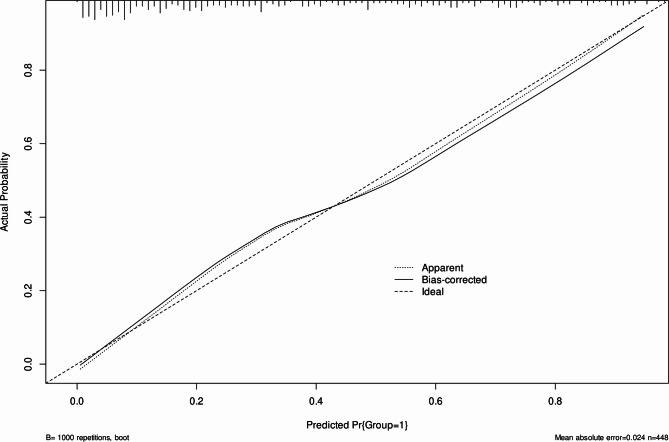

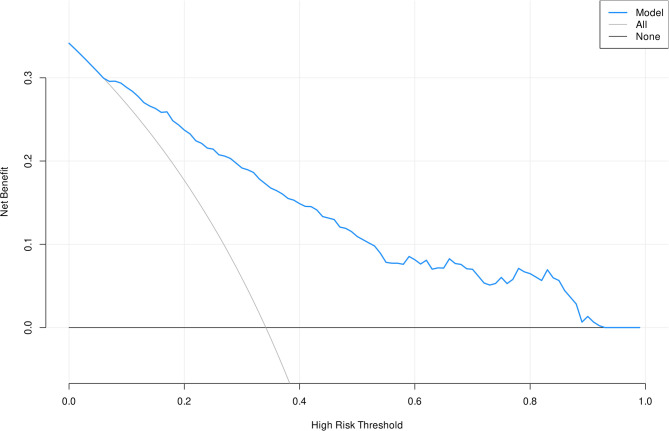

The nomogram prediction model demonstrated strong performance in assessing 1-year readmission risk: AUC = 0.85 (95% CI 0.81–0.89) indicates better discrimination via receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (Fig. 2); H-L test (χ2 = 6.15, P = 0.63) indicates a good fit and calibration plots confirmed excellent model consistency (Fig. 3); DCA revealed superior clinical utility (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for the discrimination of the model.

Fig. 3.

Calibration curves for the predicting probability of requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions (RUPR) within 1 year.

Fig. 4.

Decision curve analysis (DCA) for the requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions (RUPR) within 1 year nomogram.

Discussion

Despite substantial advancements in contemporary psychiatric management, relapse-driven readmissions persist at concerning rates across mental disorders, particularly in BD4. This phenomenon stems from multifactorial determinants including inherent disease complexity, insufficient community-based support, and suboptimal treatment adherence rooted in impaired illness insight. Our predictive model identified six independent risk predictors for RUPR within 1 year in BD: male gender, CSD, younger age, elevated MOAS scores, and reduced SSRS scores and ITAQ scores.

Existing literature demonstrates conflicting evidence regarding gender-specific relapse risks in bipolar disorder: Male predominance in 30-day, 1-year, and 2-year post-discharge11–13; Female dominated in Suominen, K’s study14; Null association identified in some studies15,16. Clinical observations suggest potential mediators including poorer medication adherence and more bad living behaviors in male patients, may be the reasons for RUPR within 1 year17,18. Nevertheless, these gender-specific mechanisms require empirical validation through prospective cohort studies.

Only those over 60 years of age had significant statistical significance in the multiple variable logistic regression analysis, aligning with previous studies12,19. This age-specific resilience may stem from enhanced illness acceptance and optimized disease management engagement among older adults, potentially mediated by cultural narratives normalizing late-life mental health challenges while stigmatizing early-onset cases. While some studies report elevated recurrence rates with advancing age20, others identify peak vulnerability at 42–53 years21. This persisting contradictory in the literature necessitates targeted investigation through large-scale prospective cohorts.

Psychosomatic multimorbidity constitutes a central challenge in contemporary psychiatric practice, with epidemiological evidence demonstrating that concurrent CSD and mental disorders represent the predominant clinical profile rather than exceptional cases22,23. Our analysis demonstrated that comorbid CSD significantly elevate psychiatric readmission risks in BD. Previous studies have shown that mental and CSD can influence each other, leading to higher recurrence and hospitalization rates for both24–28. Overall, current research generally agrees that CSD increase the risk of psychiatric relapse and readmission.

Our analysis examined associations between standardized scale scores SSRS, ITAQ, MOAS, BIS and RUPR within 1 year. Results revealed no significant association for BIS scores, whereas SSRS, ITAQ, and MOAS demonstrated robust predictive capacity for readmission risk. Lower SSRS scores indicating diminished social support, were significantly associated with elevated RUPR within 1 year, consistent with prior evidence29. Insight plays a crucial role in the management of mental illnesses. A higher ITAQ score indicates better self-awareness, which facilitates post-discharge disease management. Our study found that a decrease in ITAQ scores was associated with an increased risk of rehospitalization. However, we did not identify any studies specifically examining the relationship between insight and rehospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder (BD). Therefore, our findings are not yet supported by existing literature. The higher the MOAS score, the more severe the aggressive behavior. This study indicates that an increase in the MOAS score is associated with a higher risk of rehospitalization. This may be related to the decline in the support system for BD patients who exhibit aggressive behavior30. Impulsivity and aggression represent two distinct concepts, with impulsivity as a stable personality characteristics. Consistent with prior evidence, impulsivity measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) demonstrated limited predictive capacity for suicide risk in BD31. Our subjective guess no significant association between BIS scores and critical outcomes including: Suicide attempts, Relapse frequency, Emergency readmissions.

Limitations

While the total sample and event rate met statistical power requirements, the single-center recruitment strategy limits generalizability to regional BD populations with distinct sociocultural. Importantly, the model did not account for BD subtype variations or psychotherapy modalities, both critical sources of clinical heterogeneity. These omissions limit the model’s applicability to specific BD subtypes or settings with specialized psychotherapies. Future validation should stratify by BD subtype and document psychotherapy exposure. Despite the prediction model demonstrated robust internal validity with excellent calibration, discriminative accuracy, and clinical utility, its generalizability remains uncertain due to the absence of external validation across diverse healthcare systems. To maintain model parsimony (< 10 predictors), clinically significant variables were excluded, but possibly introducing bias by neglecting their impact on post-discharge management. Future studies should incorporate key clinical factors to enhance validity. Although we documented prevalent comorbidities, the study did not examine how specific comorbidity patterns modify RUPR within 1 year after discharge. Targeted investigation of comorbidity clusters is warranted in subsequent research. The statistical analysis was conducted on the Zstats 1.0 platform, which is a one-stop statistical analysis platform built based on the R language. However, the criteria for removing variables using the backward method was not specified.

Conclusions

Male patients, comorbid CSD, younger age, higher MOAS scores, and lower SSRS and ITAQ scores increase BD patients RUPR risk within 1 year after discharge. This nomogram prediction model helps identify high-risk cases and simplifies BD management, however, subsequent implementations necessitate subtype-stratified validation and psychotherapy regimen adjustments.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BD

Bipolar disorder

- RUPR

Requiring unplanned psychiatric readmissions

- PS

Partnered status

- CSD

Chronic somatic diseases

- VIF

Variance inflation factors

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- H-L

Hosmer–Lemeshow

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

- SSRS

Social support rating scale

- ITAQ

Insight and treatment attitude questionnaire

- MOAS

Modified overt aggression scale

- BIS

Barratt impulsiveness scale

Author contributions

X.L. Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing-Original manuscript. Xy.W. Methodology, Formal analysis. Bz.C. Investigation, Formal analysis. Ym.S. Data curation. Rh.P. Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The data contains patient privacy information and cannot be shared publicly due to ethics committee restrictions. However, relevant data can be viewed at our hospital under the supervision of the corresponding author (Run-hui Pang).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study followed Declaration of Helsinki principles with ethics approval from the third people’s hospital of tianshui. Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study design.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Merikangas, K. R. et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 68 (3), 241–251 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolitch, K. et al. Fire and darkness: on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder. Med. Clin. North. Am.107 (1), 31–60 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimenez-Palomo, A. et al. Clinical, sociodemographic and environmental predicting factors for relapse in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 360, 276–296 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tondo, L., Vazquez, G. H. & Baldessarini, R. J. Depression and mania in bipolar disorder. Curr. Neuropharmacol.15 (3), 353–358 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang, C. H. et al. One-year post-hospital medical costs and relapse rates of bipolar disorder patients in taiwan: A population-based study. Bipolar Disord. 12 (8), 859–865 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tohen, M. et al. The McLean-Harvard First-Episode mania study: Prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 160 (12), 2099–2107 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong, Q. et al. Disease burden of schizophrenia patients visiting a Chinese regional mental health centre. J. Comp. Eff. Res.9 (7), 469–481 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters, A. T. et al. The burden of repeated mood episodes in bipolar I disorder: Results from the National epidemiological survey on alcohol and related Conditions. J. Nerv. Ment Dis.204 (2), 87–94 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou, M. R. et al. Gender differences among long-stay inpatients with schizophrenia in china: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon9 (5), e15719 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong, S. et al. A clinical risk prediction tool for identifying the risk of violent offending in severe mental illness: A retrospective case-control study. J. Psychiatr Res.163, 172–179 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgcomb, J. et al. High-Risk phenotypes of early psychiatric readmission in bipolar disorder with comorbid medical Illness. Psychosomatics60 (6), 563–573 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton, J. E. et al. Predictors of psychiatric readmission among patients with bipolar disorder at an academic safety-net hospital. Aust N Z. J. Psychiatry. 50 (6), 584–593 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, C. et al. A 2-year follow-up study of discharged psychiatric patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res.218 (1–2), 75–78 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suominen, K. et al. Gender differences in bipolar disorder type I and II. Acta Psychiatr Scand.120 (6), 464–473 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geraili-Afra, Z. et al. Comparison of efficiency GEE and QIF methods for predicting factors affecting on bipolar I disorder under complete-case in a longitudinal studies. Acta Inf. Med.26 (2), 111–114 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demmo, C. et al. Neurocognitive functioning, clinical course and functional outcome in first-treatment bipolar I disorder patients with and without clinical relapse: A 1-year follow-up study. Bipolar Disord. 20 (3), 228–237 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Dios, C. et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorders in Spain (PREBIS study data). J. Affect. Disord. 141 (2–3), 406–414 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degenhardt, E. K. et al. Predictors of relapse or recurrence in bipolar I disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 136 (3), 733–739 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson, G. A. et al. Early determinants of four-year clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder with psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 14 (1), 19–30 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieta, E. et al. Clinical management and burden of bipolar disorder: results from a multinational longitudinal study (WAVE-bd). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol.16 (8), 1719–1732 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Hagan, M. et al. Predictors of rehospitalization in a naturalistic cohort of patients with bipolar affective disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol.32 (3), 115–120 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler, R. C. et al. The US National comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr Res.13 (2), 69–92 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler, R. C. & Merikangas, K. R. The National comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr Res.13 (2), 60–68 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felker, B., Yazel, J. J. & Short, D. Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: A review. Psychiatr Serv.47 (12), 1356–1363 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacovides, A. & Siamouli, M. Comorbid mental and somatic disorders: An epidemiological perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 21 (4), 417–421 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egede, L. E. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 29 (5), 409–416 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuyen, J. et al. Comorbidity was associated with neurologic and psychiatric diseases: A general practice-based controlled study. J. Clin. Epidemiol.59 (12), 1274–1284 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andres, E. et al. Psychiatric morbidity as a risk factor for hospital readmission for acute myocardial infarction: An 8-year follow-up study in Spain. Int. J. Psychiatry Med.44 (1), 63–75 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shokrgozar, S. et al. Evaluation of patient social support, caregiver burden, and their relationship with the course of the disease in patients with bipolar disorder. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 68 (8), 1815–1823 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, C. E. et al. Compulsory admission is associated with an increased risk of readmission in patients with schizophrenia: A 7-year, population-based, retrospective cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.54 (2), 243–253 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zakowicz, P. et al. Impulsivity as a risk factor for suicide in bipolar disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 706933 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data contains patient privacy information and cannot be shared publicly due to ethics committee restrictions. However, relevant data can be viewed at our hospital under the supervision of the corresponding author (Run-hui Pang).