Abstract

The period from childhood to early adulthood is critically susceptible to the onset of mental disorders (MDs), substance use disorders (SUDs), and self-harm, with significant implications for public health policy. Understanding these trends over time and across different regions is essential for effective intervention and resource allocation. This study utilizes data from GBD 2021, focusing on youths aged 10–24 years globally. Data span from 1990 to 2021, providing a longitudinal perspective on trends and are stratified by age groups, gender, geographic regions, and Socio-demographic Index (SDI). The results showed that in 2021, the global standardized prevalence of MDs among youths reached 14,778 per 100,000, marking a 6.8%(4.7–9.0) increase from 1990. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders exhibited the highest prevalence. The prevalence of SUDs decreased by 20.3%(17.4–22.9) since 1990, while self-harm rates decreased by 35%(33.6–38.3). The highest burden was observed in the 20–24 age group, with notable gender disparities: females had higher rates of anxiety and depressive disorders, whereas males were more affected by SUDs and conduct disorders. Geographical and socio-economic variations were pronounced, with high SDI regions exhibiting the most significant prevalence of most MDs and SUDs. The study highlights a significant rise in the burden of MDs among global youth over three decades, exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. It underscores the need for targeted mental health interventions and resource allocation to address the escalating mental health needs of young populations.

Subject terms: Psychiatric disorders, Depression, Addiction

Background

Globally, mental disorders (MDs), substance use disorders (SUDs) and self-harm among youths (ages 10–24) have escalated markedly and now constitute a significant public health concern [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies MDs and SUDs as leading contributors to morbidity and mortality in this population [2]. Alarming trends such as increased rates of suicide and self-mutilation [3] underscore the severe impact on the psychological well-being and quality of life of affected individuals while also imposing a considerable burden on families and societal structures [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the mental health of young people worldwide, contributing to social isolation, disruptions in education, increased family stress, and heightened anxiety regarding health and the future [5]. Research indicates that young people are particularly vulnerable to elevated rates of depression and anxiety during and after periods of enforced isolation [6]. While online learning facilitated academic continuity, it also introduced greater academic pressure and distractions [7]. Furthermore, financial hardship and escalating family conflict exacerbated the emotional and psychological strain on young people [8]. As a result, these factors have notably increased the risk of MDs, SUDs, and self-harm behaviors in this population [9, 10].

Despite the critical importance of addressing these mental health issues, resource allocation remains inadequate and disproportionate to their severity. Notably, many low- and middle-income countries experience a severe shortages of mental health resources, highlighting substantial global disparities [11]. Therefore, systematic research is imperative to delineate the epidemiological trends of these conditions, providing a robust scientific foundation for policymakers.

Consequently, this study aims to harness data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 to systematically assess the prevalence and burden of MDs, SUDs, and self-harm among youths from 1990 to 2021. Analyzing variations across age, gender, countries, and Socio-demographic Indexs (SDIs) for health reveals critical trends, thereby furnished a scientific basis for formulating effective intervention measures. This study presents two key innovations. First, it is, to our knowledge, the first study to systematically analyze the global trends and disease burden of MDs, SUDs, and self-harm from 1990 to 2021, using the most recent GBD data. Second, it assesses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s mental health.

Methods

Data sources

The GBD study annually estimates the prevalence, incidence, and mortality of 369 diseases and injuries, providing vital data for stakeholders to inform resource allocation decisions [12]. This study leverages GBD 2021, data accessible via the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). These estimates derive from a systematic collection of published and unpublished literature, survey microdata, health records, registries, and disease surveillance systems; all catalogued at http://ghdx.healthdata.org.

Study subjects

The cohort comprises individuals aged 10–24 globally from 1990 to 2021. Data were stratified by age groups (10–14, 15–19, and 20–24 years), gender, geographic location, and the SDI to elucidate mental health disparities across various demographics.

GBD cause hierarchy

In the GBD 2021, causes of diseases, injuries, and deaths are organized into three primary levels—Infectious Diseases, Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition; Non-Communicable Diseases; Injuries—comprising 22 secondary, 174 tertiary, and 301 quaternary causes [3]. This study focuses on secondary causes such as MDs — encompassing anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, conduct disorder, autism spectrum disorders (ASD), bipolar disorder, eating disorders, schizophrenia, Idiopathic developmental intellectual disability (IDID), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other MDs — and SUDs, including alcohol use disorders and drug use disorders, as well as self-harm. The definitions of diseases are provided in eTable 1.

GBD indicators

This analysis utilizes two primary indicators: prevalence and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). Prevalence estimates were generated using DisMod-MR 2.1, a Bayesian meta-regression tool that integrates diverse epidemiological data to produce internally consistent estimates across different demographics and over time. DALYs, combining years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs), serve as a comprehensive measure of disease impact. YLLs are calculated by subtracting the actual age at death from the expected life span, while YLDs are computed by multiplying the prevalence of a condition by its disability weight.

Socio-demographic index (SDI)

SDI, a composite metric, assesses a region’s socio-economic status based on income, education, and fertility rates. In brief, it is the geometric mean of three 0-to-1 indicators: the total fertility rate for females under 25 years of age (TFU25), the average level of education for individuals aged 15 and above (EDU15 + ), and per capita lag-distributed income (LDI) [13]. It is categorized into five levels for analysis: low (0–0.45), lower-middle (0.45–0.61), middle (0.61–0.69), upper-middle (0.69–0.81), and high (0.81–1).

Data standardization and quality control

Data sources include surveys, disease registries, hospital claims, and vital statistics, which are systematically identified, extracted, and adjusted for biases using standardized tools like DisMod-MR 2.1 and MR-BRT. Standardization involves mapping diagnoses to GBD-defined categories using ICD codes and adjusting for systematic biases, such as variations in case definitions and reporting methods. Crosswalking techniques, including meta-regressions, are applied to align non-standard data with GBD reference definitions, thus enabling the inclusion of a broader range of data sources. Missing data and inconsistent reporting are addressed using spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR), which interpolates and smooths data across age, sex, region, and time dimensions. This approach ensures robust estimates even in regions with sparse or incomplete data. Quality control measures, such as outlier detection via the median absolute deviation (MAD) method, further enhance data reliability. The methodology prioritizes transparency, adhering to GATHER guidelines, and incorporates uncertainty intervals for all estimates, reflecting variations in data quality and availability [13].

Data processing and analysis

To examine the burden of MDs among youths from 1990 to 2021, we conducted a detailed descriptive analysis using GBD data. Age-standardized prevalence rates and DALYs per 100,000 population were compared across different age groups, genders, regions, countries, and SDIs. Age-standardized rates per 100,000 population were derived using the age-standardized rate formula: , where represents the age-specific rate in the ith age group, represents the population weight in the same age group among the GBD standard population, and N is the number of age groups. Temporal trends were assessed by calculating the Percentage Change (PC) over specified intervals, with positive PCs indicating an upward trend and negative PCs a downward trend. Uncertainty intervals (UIs) for prevalence and DALYs were derived from 1000 ordered bootstrap samples at the 25th and 975th percentiles, accounting for variability in data collection, diagnostic criteria, and reporting standards across different contexts. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2). Custom computer code was used to generate the core results presented in this paper. The code will be made available for access by interested researchers.

Results

Global trends in MDs, SUDs, and self-harm from 1990 to 2021

In 2021, the standardized prevalence of 10 MDs among global youth reached 14,778.109 per 100,000, reflecting a 6.8% (4.7–9.0) increase from 1990. Anxiety disorders exhibited the highest prevalence at 4,976.610, whereas schizophrenia recorded the lowest at 105.694. Depressive disorders and eating disorders experienced the most significant increases in prevalence, at 22.5% (18.3–26.5) and 17.2% (14.6–19.4), respectively; conversely, ADHD and IDID saw notable declines of 12.4% (10.2–14.7) and 11.0% (8.3–13.9), respectively. SUDs in 2021 stood at 1,573.968 per 100,000, a decrease of 20.3% (17.4–22.9) from 1990, with alcohol use disorders reducing by 26.4% (23.8–28.9) and drug use disorders by 15.5% (11.5–19.6). The standardized prevalence of self-harm was 45.136 per 100,000, a 35.8% (33.6–38.3) reduction from 1990 (Table 1). The trends in DALYs for MDs, SUDs, and self-harm from 1990 to 2021 paralleled those of prevalence (Table 1). The trends in the prevalence of MDs, SUDs, and self-harm across 21 global regions from 1990 to 2021 are shown in eTable 2.

Table 1.

Global Prevalence of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Among Individuals Aged 10–24 Years (1990–2021): Counts, Rates, and Percentage Change.

| Counts(95% Uncertainty Intervals) | Rates per 100,000 population(95% Uncertainty Intervals) | Change % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2019 | 2021 | 1990 | 2019 | 2021 | 1990–2021 | 2019–2021 | ||

| Mental disorders | Prevalence | 214198244(190359408–240526816) | 250010208(222660354–279186130) | 278977301(248614347–312808723) | 13844.304(12303.526–15546.003) | 13446.162(11975.220–15015.315) | 14778.109(13169.709–16570.242) | 0.067(0.047–0.090) | 0.099(0.084–0.115) |

| DALYs | 26113164(19267147–34431761) | 31515839(23152522–41716825) | 36315577(26593541–48108407) | 1687.776(1245.296–2225.433) | 1694.999(1245.199–2243.633) | 1923.725(1408.725–2548.420) | 0.140(0.116–0.164) | 0.135(0.113–0.156) | |

| Anxiety disorders | Prevalence | 63753648(49650308–80523297) | 74673492(57491286–95108863) | 93947157(71898222–120279391) | 4120.598(3209.055–5204.473) | 4016.124(3092.022–5115.188) | 4976.610(3808.624–6371.493) | 0.208(0.177–0.239) | 0.239(0.213–0.267) |

| DALYs | 7822522(4925459–11445029) | 9178143(5755309–13470744) | 11523716(7273258–16910890) | 505.594(318.348–739.728) | 493.623(309.535–724.490) | 610.439(385.282–895.811) | 0.207(0.175–0.239) | 0.237(0.212–0.265) | |

| Depressive disorders | Prevalence | 38476683(30133092–48956768) | 46544779(36287968–59278479) | 57488802(44127193–73889612) | 2486.869(1947.596–3164.229) | 2503.292(1951.656–3188.142) | 3045.322(2337.525–3914.113) | 0.225(0.183–0.265) | 0.217(0.184–0.246) |

| DALYs | 7025089(4512560–10171661) | 8448036(5419921–12165594) | 10718195(6792136–15633301) | 454.054(291.661–657.426) | 454.356(291.497–654.295) | 567.769(359.796–828.134) | 0.250(0.205–0.293) | 0.250(0.220–0.277) | |

| Conduct disorder | Prevalence | 26622503(18911225–34750424) | 33034647(23253343–43110698) | 33715702(23734579–44002151) | 1720.696(1222.292–2246.029) | 1776.684(1250.622–2318.599) | 1786.003(1257.279–2330.901) | 0.038(0.023–0.056) | 0.005(0.005–0.006) |

| DALYs | 3233927(1732328–5150628) | 4024334(2135652–6456560) | 4103154(2184552–6580924) | 209.019(111.966–332.901) | 216.439(114.861–347.250) | 217.354(115.721–348.608) | 0.040(0.022–0.059) | 0.040(0.022–0.059) | |

| ASD | Prevalence | 12481409(10505872–14756851) | 15424274(12967762–18204582) | 15691230(13233173–18413815) | 806.713(679.027–953.782) | 829.555(697.438–979.087) | 831.203(700.994–975.425) | 0.030(0.017–0.042) | 0.002(−0.004–0.008) |

| DALYs | 2376477(1621019–3344886) | 2944562(1994698–4163447) | 2991043(2019795–4209367) | 153.599(104.772–216.190) | 158.366(107.280–223.920) | 158.443(106.993–222.980) | 0.032(0.015–0.046) | 0.000(−0.010–0.011) | |

| Bipolar disorder | Prevalence | 6148854(4644731–8261936) | 7720414(5773485–10465889) | 7813742(5841649–10599682) | 397.420(300.204–533.995) | 415.223(310.512–562.881) | 413.913(309.446–561.491) | 0.042(0.019–0.058) | −0.003(−0.005−0.002) |

| DALYs | 1366382(869316–2097702) | 1721574(1094871–2645345) | 1736702(1101172–2677441) | 88.314(56.187–135.581) | 92.590(58.885–142.273) | 91.997(58.332–141.831) | 0.042(0.016–0.063) | −0.006(−0.019–0.005) | |

| Eating disorders | Prevalence | 4713373(3294181–6768624) | 6664036(4599221–9652296) | 6741277(4636006–9778158) | 304.640(212.913–437.477) | 358.408(247.357–519.124) | 357.102(245.581–517.973) | 0.172(0.146–0.194) | −0.004(−0.011–0.002) |

| DALYs | 1010749(571351–1632307) | 1430820(808760–2312021) | 1444296(814254–2321363) | 65.328(36.928–105.501) | 76.953(43.497–124.346) | 76.508(43.133–122.968) | 0.171(0.139–0.197) | −0.006(−0.018–0.007) | |

| Schizophrenia | Prevalence | 1709490(1170273–2351733) | 1985802(1334553–2769696) | 1995272(1334429–2784503) | 110.490(75.638–152.000) | 106.801(71.776–148.961) | 105.694(70.688–147.502) | −0.043(−0.077−0.019) | −0.010(−0.018−0.002) |

| DALYs | 1143103(730617–1679703) | 1331673(838284–1974793) | 1332728(838712–1995578) | 73.882(47.222–108.565) | 71.621(45.085–106.209) | 70.598(44.429–105.711) | −0.044(−0.083−0.013) | −0.014(−0.037–0.008) | |

| IDID | Prevalence | 27420552(15133319–39000975) | 29501962(16589510–41963360) | 29776106(16796598–42344383) | 1772.276(978.114–2520.755) | 1586.688(892.225–2256.892) | 1577.313(889.757–2243.085) | −0.110(−0.139−0.083) | −0.006(−0.039–0.019) |

| DALYs | 1095743(509618–1884258) | 1253112(590408–2126017) | 1269634(594421–2153292) | 70.821(32.938–121.786) | 67.395(31.754–114.342) | 67.256(31.488–114.065) | −0.050(−0.103–0.026) | −0.002(−0.016–0.011) | |

| ADHD | Prevalence | 38398506(26610746–53946735) | 40370124(28024990–56888363) | 41030400(28462267–57975717) | 2481.816(1719.936–3486.747) | 2171.204(1507.253–3059.596) | 2173.481(1507.716–3071.115) | −0.124(−0.147−0.102) | 0.001(−0.019–0.020) |

| DALYs | 469027(247085–776226) | 493697(259985–804767) | 501444(262431–823453) | 30.315(15.970–50.170) | 26.552(13.983–43.282) | 26.563(13.902–43.620) | −0.124(−0.148−0.100) | 0.000(−0.020–0.021) | |

| Other mental disorders | Prevalence | 7420259(4761991–10564923) | 8957487(5755879–12796460) | 9043148(5810282–12923225) | 479.595(307.782–682.844) | 481.756(309.565–688.225) | 479.038(307.785–684.575) | −0.001(−0.009–0.006) | −0.006(−0.006−0.005) |

| DALYs | 570144(324392–905832) | 689889(392486–1089663) | 694665(397814–1103398) | 36.850(20.967–58.547) | 37.104(21.109–58.605) | 36.798(21.073–58.450) | −0.001(−0.021−0.018) | −0.008(−0.027–0.009) | |

| Substance disorders | Prevalence | 30545746(24749033–37248396) | 30220611(24572914–37083487) | 29712950(24098991–36282082) | 1974.267(1599.608–2407.481) | 1625.339(1321.592–1994.441) | 1573.968(1276.582–1921.951) | −0.203(−0.229−0.174) | −0.032(−0.042−0.024) |

| DALYs | 4352041(3279245–5572923) | 4360694(3328222–5599740) | 4374873(3335624–5594578) | 281.286(211.948–360.195) | 234.529(179.000–301.168) | 231.748(176.696–296.358) | −0.176(−0.212−0.138) | −0.012(−0.025−0.000) | |

| Drug use disorders | Prevalence | 17048990(13527566–21452332) | 17833228(13963397–22593767) | 17574530(13801512–22159225) | 1101.930(874.329–1386.532) | 959.115(750.986–1215.148) | 930.966(731.100–1173.828) | −0.155(−0.196−0.115) | −0.029(−0.044−0.017) |

| DALYs | 2672126(1995510–3340082) | 2878475(2185471–3578624) | 2926335(2213193–3648328) | 172.708(128.976–215.880) | 154.811(117.540–192.467) | 155.015(117.238–193.261) | −0.102(−0.162−0.047) | 0.001(−0.014–0.017) | |

| Alcohol use disorders | Prevalence | 13860356(9769621–19563880) | 12701577(9106580–17782905) | 12449446(8887512–17568278) | 895.838(631.441–1264.475) | 683.122(489.774–956.408) | 659.478(470.793–930.635) | −0.264(−0.289−0.238) | −0.035(−0.045−0.025) |

| DALYs | 1679915(1122113–2541918) | 1482218(975613–2236278) | 1448538(951992–2169098) | 108.578(72.526–164.292) | 79.717(52.471–120.273) | 76.733(50.429–114.902) | −0.293(−0.325−0.265) | −0.037(−0.053−0.023) | |

| Self-harm | Prevalence | 1088491(852835–1417569) | 843805(656394–1082598) | 852056(663212–1098517) | 70.353(55.121–91.622) | 45.382(35.302–58.225) | 45.136(35.132–58.191) | −0.358(−0.383−0.336) | −0.005(−0.015–0.006) |

| DALYs | 10707013(8786816–11478055) | 8007493(7434934–8568333) | 7995473(7371428–8650637) | 692.028(567.919–741.863) | 430.663(399.869–460.826) | 423.540(390.483–458.245) | −0.388(−0.443−0.264) | −0.017(−0.061–0.028) | |

ASD Autism spectrum disorders, IDID Idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, ADHD Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

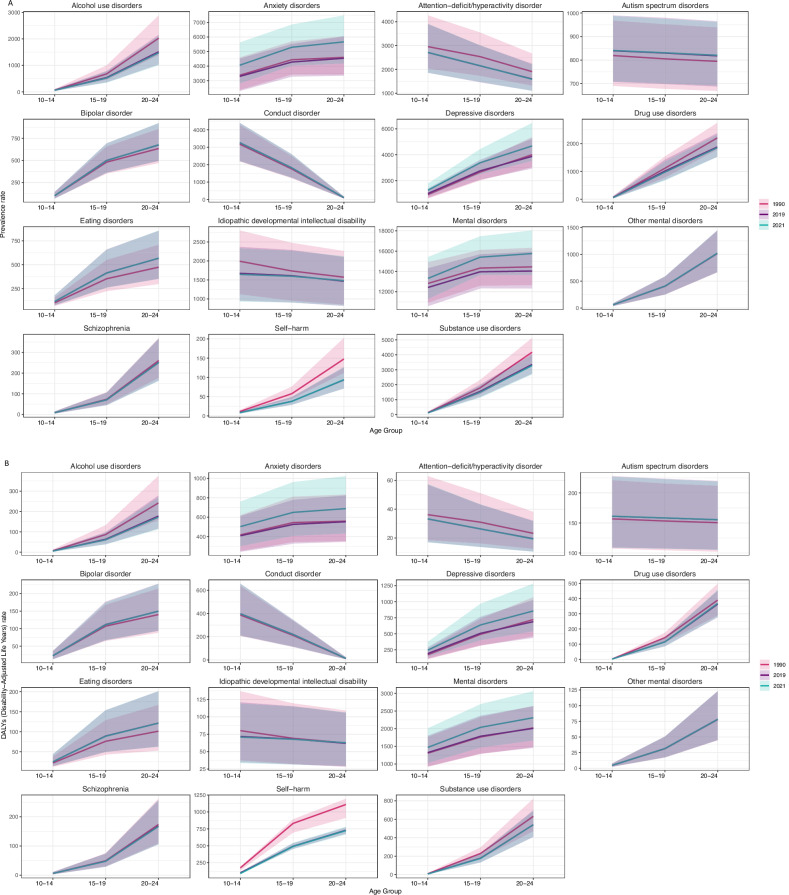

Prevalence and DALYs by age group

The prevalence of disorders varied significantly among age groups in 2021. The 20–24 age group exhibited the highest prevalence rates for anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, other MDs, alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, and self-harm. Conversely, conduct disorders and ADHD were most prevalent in the 10–14 age group. ASD and IDID showed minimal variation across age groups (Fig. 1A, eTable 3). DALYs demonstrated similar patterns to prevalence rates (Fig. 1B, eTable 3).

Fig. 1. Global prevalence and DALYs of mental disorders, substance use disorders, and self-harm among youths in 2021.

A Prevalence, B DALYs, DALYs, disability adjusted life years.

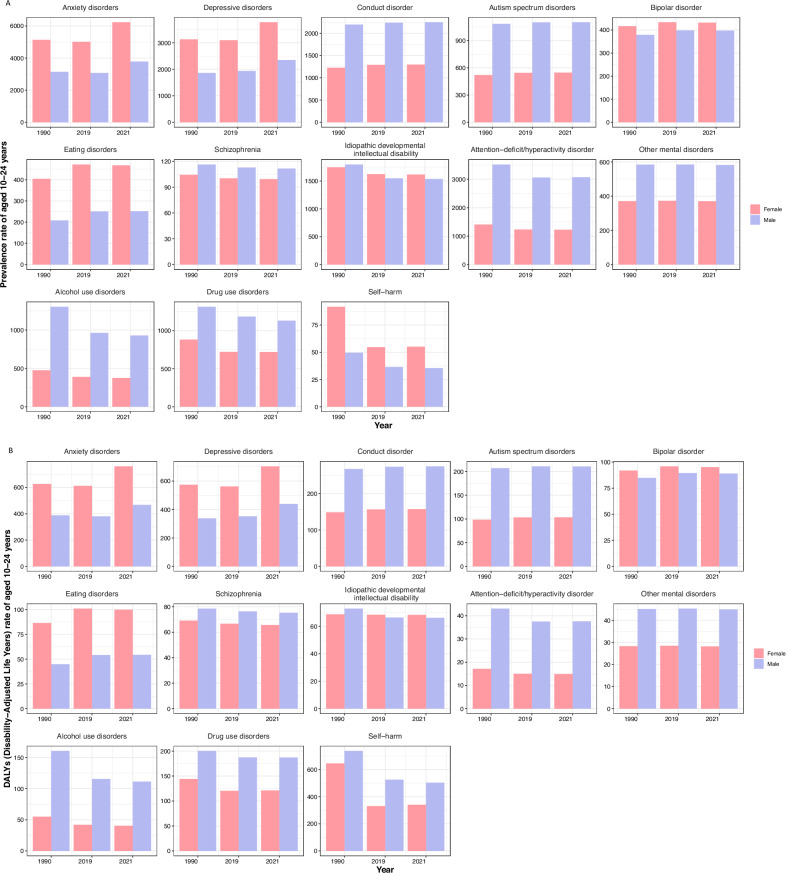

Impact of gender differences on prevalence and DALYs

Gender disparities in prevalence were marked in 2021. Females significantly outnumbered males in the prevalence of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and eating disorders. Males, however, exhibited higher prevalences of conduct disorders, ASD, ADHD, other MDs, alcohol use disorders, and drug use disorders. The discrepancies for bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, and developmental disorders were less pronounced. Notably, while the prevalence of self-harm was higher among females, this gap has significantly narrowed over the past three decades, attributed to declining rates among women (Fig. 2A, eTable 4). DALYs generally mirrored these prevalence trends, though males recorded higher DALYs from self-harm (Fig. 2B, eTable 4).

Fig. 2. Global prevalence and DALYs of mental disorders, substance use disorders, and self-harm among youths divided in gender (1990–2021).

A Prevalence, B DALYs, DALYs, disability adjusted life years.

Distribution of MDs, SUDs, and self-harm across global regions and countries

In 2021, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, ADHD, and conduct disorders were the most prevalent MDs across 21 global regions, ranking among the top four, whereas eating disorders and schizophrenia had lower prevalences, ranking 11th-12th. Significant regional disparities were observed in the prevalence of IDID, drug use disorders, and alcohol use disorders. IDID ranked highest in prevalence in South Asia, while drug use disorders were ranked 3rd and 4th in high-income regions of North America, Western Europe, and Australasia. Alcohol use disorders held the fifth rank in high-income North America, Central Latin America, and Central Asia (Fig. 3A, eTable 5). The DALYs rankings across these regions paralleled the prevalence trends, with anxiety disorders and depressive disorders yielding the highest DALYs. Conduct disorders and self-harm ranked 3rd and 4th in DALYs, respectively, while schizophrenia and other MDs showed the lowest DALYs. Notably, in high-income North America, drug use disorders contributed significantly to disability, with similar high DALYs observed in Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and Australasia. In South Asia, DALYs from developmental disorders were substantially higher than in other regions (Fig. 3B, eTable 3). Prevalence and DALYs for MDs, SUDs, and self-harm across 204 countries globally are detailed in Fig. 4A–F, eTable 6.

Fig. 3. Ranking of global prevalence and DALYs of mental disorders, substance use disorders, and self-harm among youths in 2021.

A Prevalence, B DALYs, DALYs, disability adjusted life years.

Fig. 4. Global prevalence and DALYs of mental disorders, substance use disorders, and self-harm among youths across 204 countries in 2021.

A Prevalence of mental disorders, B prevalence of substance use disorders, C prevalence of self-harm, D DALYs of mental disorders, E DALYs of substance use disorders, F DALYs of self-harm, DALYs, disability adjusted life years.

SDI-related differences

In regions with high SDI, the prevalence rates for anxiety disorders, ASD, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, eating disorders, other MDs, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorders, and drug use disorders were highest. ADHD and self-harm showed the highest prevalence in upper-middle and high SDI regions. Conduct disorders were most prevalent in low SDI regions, while developmental disorders were predominantly seen in lower-middle SDI regions (Fig. 5A, eTable 7). Differences in DALY across SDI regions were closely aligned with the prevalence of disparities (Fig. 5B, eTable 7).

Fig. 5. Global prevalence and DALYs of mental disorders, substance use disorders, and self-harm among youths divided in SDI (1990–2021).

A Prevalence, B DALYs, DALYs, disability adjusted life years.

Discussion

This study revealed that from 1990 to 2021, the standardized global prevalence of MDs increased by 6.8%, while DALYs rose by 14%. Despite heightened global attention and interventions targeting mental health, the overall burden of mental illness continued to escalate significantly. Over the past three decades, the prevalence of SUDs has notably decreased, a trend potentially influenced by various factors such as demographic shifts, cultural and lifestyle changes, social dynamics, and the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, which altered access to substances and reduced high-risk social behaviors [14]. Additionally, changes in policy, public awareness, and healthcare accessibility may have contributed to these trends [15]. The significant decline in self-harm rates among global youth could be attributed to the establishment of suicide prevention clinics, increased levels of social spending, and strengthened welfare systems [16–18].

Anxiety and depressive disorders remained the most prevalent mental health concerns, showing the highest growth rates in both prevalence and DALYs over the study period. These trends may have been associated with the high-pressure environments of modern society, the pervasive influence of social media, diminished face-to-face social interactions, economic uncertainties, and an accelerated pace of life [19, 20]. Consistent with previous findings [21], our research indicated a decline in the prevalence of anxiety disorders among adolescents from 1990 to 2019. However, during the COVID-19 period (2019–2021), there was a significant increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders [22], driven by pandemic-related fears of illness, medical shortages, social isolation, reduced physical activity, and increased screen time [23–27]. Additionally, the prevalence of eating disorders has risen substantially over the past 30 years, correlated with the adverse impact of social media on body satisfaction and eating behaviors among youths [28–30]. In interventions targeting anxiety, depression, and eating disorders among youth, first, a stage-based stepped-care approach should be adopted to ensure more personalized interventions. These interventions should be tailored according to the severity and needs of the youth’s mental disorders. This method allows for precise stratification and ensures that the intervention strategy aligns with individual symptoms, thereby enhancing effectiveness and optimizing resource allocation [31]. Second, digital mental health literacy (DMHL) interventions have proven to be highly effective in improving young people’s understanding of mental disorders and their self-regulation abilities. Internet-based intervention programs, such as online mental health education and self-help tools, can help young people identify and cope with emotional challenges like anxiety and depression [32]. Lastly, considering the negative impact of social media on youth mental health, particularly its distortion of body image and its role in triggering eating disorders, future interventions should focus on reducing social media’s harmful influence on youth body image. This should include promoting regulatory policies for online platforms and enhancing media literacy and critical thinking skills among youth, which could reduce the risks of anxiety and eating disorders [33]. In response to the rising prevalence of anxiety and depression induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to develop scientifically sound and effective intervention strategies. These strategies should optimize the use of limited resources while taking into account local socio-cultural contexts and the specific needs of vulnerable populations, with a particular emphasis on inclusivity, stigma reduction, and the protection of human rights [34]. Key measures include enhancing public health communication to help individuals understand the mental health impacts of the pandemic and adopt evidence-based management strategies. Establishing clear pathways for assessment and access to mental health services is also critical to ensuring service availability and accessibility [35]. Furthermore, a combination of service modalities—such as digital platforms, telehealth, and face-to-face consultations—should be employed to effectively address diverse individual needs [36].

The study also elucidated trends in specific mental health challenges across various age groups. The prevalence of most MDs, including anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, as well as self-harm, showed a significant increase during the ages of 20 to 24. This age group represents a critical transitional period from adolescence to adulthood, characterized by multiple pressures related to academics, work-life balance, and interpersonal relationships [37, 38]. Significant physiological and neurodevelopmental changes from adolescence to early adulthood influence emotional regulation and coping mechanisms [39]. Furthermore, studies indicated that adolescents exhibited stronger emotional reactivity during emotional regulation tasks, often activating brain regions associated with emotional processing, such as the amygdala, fusiform gyrus, and thalamus. In comparison to adults, adolescents tended to rely more on automatic emotional responses when confronted with emotional stimuli, and engage less with cognitive control regions involved in emotion regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex. This neurodevelopmental difference may increase adolescents’ vulnerability to emotional stress, thereby elevating their risk for developing emotional disorders [40]. The prevalence of SUDs significantly increased in the 20–24 age group. This may be a result of the continuation of early adolescent behavioral dysregulation, such as aggressive behavior, law-breaking, and sensation-seeking [41]. The prevalence of self-harm markedly increased in the 20–24 age group, a period characterized by academic pressure, career development challenges, and complex interpersonal dynamics. Additionally, biological factors, such as hormonal fluctuations and ongoing neurodevelopmental immaturity, further compromise the coping capacity of individuals in this age bracket. Notably, self-harm and suicidal behaviors display a high degree of social contagion within this population [42]. Exposure to such behaviors, whether through friends, family, or social media, significantly increases the risk of imitation [43].

Gender differences were markedly evident in the prevalence and DALYs of MDs. Studies indicated that women exhibited higher rates of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and eating disorders, whereas men were more affected by neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD, conduct disorders, and SUDs, including alcohol and drug use disorders. Several factors contribute to these gender differences [44]. Biologically, women may be more vulnerable to mood and anxiety disorders due to the effects of sex hormones. Environmentally, prenatal and postnatal exposures might differentially impact genders. Genetic factors, particularly variations in sex chromosomes, contribute to disparities in MD prevalence between genders, with mutations on the X chromosome linked to conditions like Fragile X syndrome. Additionally, sociocultural influences may affect symptom reporting and utilization of medical services between genders; societal expectations can lead to underreporting of symptoms like depression in men, thereby influencing diagnoses and treatment outcomes [45]. The higher prevalence and greater disease burden of SUDs in males may be attributed to several factors [46, 47]. First, males tend to initiate substance use at an earlier age and exhibit more severe and frequent patterns of abuse during adolescence. Second, biological differences, such as variations in hormone levels and neurotransmitter responses, make males more susceptible to the addictive effects of substances. Third, social and cultural pressures encourage risk-taking behaviors and greater stress among males, which further heighten their vulnerability to substance use. Finally, males are less likely to seek help when confronted with substance use problems, exacerbating the overall disease burden. These combined factors contribute to the increased risk and severity of SUDs in males. Notably, while the prevalence of self-harm was higher among women [48], DALYs resulting from self-harm were more significant among men, possibly due to men employing more lethal methods of self-harm, such as hanging, jumping from heights, and using weapons [49].

The study further revealed that the prevalence and DALYs for MDs were significantly higher in high SDI regions compared to lower-income regions, especially concerning disorders such as anxiety, ASD, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorders, and drug use disorders. In high SDI regions, such as high-income North America, Western Europe, and Australasia, robust healthcare systems and increased health awareness facilitate the diagnosing and reporting of MDs. Additionally, factors such as occupational stress, academic pressure, and societal expectations prevalent in these regions may contribute substantially to the high incidence of MDs [50–53]. Conversely, IDID manifested predominantly in lower SDI regions, like South Asia, underscoring the intrinsic link between developmental levels and socio-economic conditions [54]. Research indicated that approximately one-third of children under five in low- and middle-income countries did not achieve expected cognitive developmental milestones, with physical illness, malnutrition, poverty, and a scarcity of medical and educational resources serving as pivotal risk factors for developmental disorders [55]. Moreover, conduct disorders were more prevalent in low SDI regions, including some sub-Saharan African countries. These disorders are closely associated with health deprivations linked to poverty and the challenges faced by children and adolescents in adapting to high-pressure environments [56, 57]. Additional factors, such as suboptimal mental and physical health levels of parents during the prenatal and perinatal periods, adverse family dynamics, and hazardous living conditions, may further escalate the risk of conduct disorders [58]. The burden of SUDs was higher in high-income countries, consistent with previous research [59]. This may be attributed to the greater availability and accessibility of substances in these countries. Additionally, the socio-cultural environment in high-income nations often emphasizes individual freedom and consumerism, which may encourage more widespread engagement in substance use behaviors. Globally, the Inuit population in Greenland reported the highest rates of self-harm, consistent with prior studies [60]. These studies highlight persistently elevated suicide rates among Greenlandic Inuits, with young males aged 20–24 being particularly affected. Suicide incidences peak during spring and summer, possibly due to the influence of polar daylight. Furthermore, rapid modernization and social transitions have disrupted traditional Inuit lifestyles, collectively exacerbating the risks of self-harm and suicide.

This study found that the global prevalence of MDs increased steadily between 1990 and 2021. In contrast, the trends for SUDs showed notable regional variations. Specifically, the prevalence of alcohol use disorders significantly decreased in Eastern Europe, East Asia, and high-income North America, while drug use disorders decreased notably in East Asia and Australia. These declines may be attributed to public health interventions, social-cultural changes, and improvements in health awareness. However, in high-income North America, North Africa and the Middle East, and South America, the prevalence of drug use disorders significantly increased. This trend may be influenced by local socio-economic factors, cultural backgrounds, and the societal acceptance of substance use. Although there is a high comorbidity between MDs and SUDs, the contrasting trends observed in these two disorders worldwide may reflect the diverse mechanisms and socio-cultural differences in how these conditions are addressed across regions.

Limitations

Although this study provides comprehensive insights through a systematic analysis of the prevalence and burden of mental health issues among global youth from 1990 to 2021, several limitations may impact the interpretation and applicability of the results. Firstly, the study relies on data from the GBD study. While GBD data is extensive and systematically collected, reporting standards and methods for mental disorders vary across countries and regions. The diversity and quality of data sources may differ, particularly in some low- and middle-income countries where mental disorder data may be incomplete or inaccurate, potentially affecting the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the findings. Secondly, changes in the diagnostic criteria and classifications of mental disorders during the study period, such as updates to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD), could influence mental disorder diagnoses, thus impacting prevalence and DALY reporting. These changes make data from different periods not entirely comparable, affecting the analysis of long-term trends.

Additionally, the complexity of regional differences might lead to some subtle but significant factors being inadequately considered. Cultural, socio-economic, healthcare accessibility and policy differences across regions vary, and these disparities might not be fully captured and reflected in some cases. Mental disorder reporting might be influenced by sociocultural factors, medical resource accessibility, and public awareness, leading to underreporting in some regions. In contrast, higher-income countries might have relatively higher reporting rates due to better medical resources and public awareness. These reporting biases could lead to inaccuracies in the data. Despite using standardized methods for data analysis, some methodological limitations still exist. For example, data standardization processes and the selection of statistical models might affect the accuracy and reliability of results. In integrating cross-national and cross-regional data, some data processing methods might lead to the loss or distortion of information.

Conclusion

This study underscores a significant escalation in the burden of MDs among global youth from 1990 to 2021, with anxiety and depressive disorders continuing to exhibit the highest prevalence and DALYs over the past 30 years, particularly during the COVID-19 period. Conversely, the prevalence of SUDs and self-harm has significantly declined. There are marked differences in prevalence and DALYs across different ages, genders, countries, and SDI regions. These findings affirm that mental health remains a paramount health challenge of the 21st century and underscore the necessity for countries to develop and implement evidence-based prevention measures and provide accessible mental health treatment services for youth.

Supplementary information

The Definitions of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm.

Trends in the Prevalence of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 21 Global Regions from 1990 to 2021.

Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by Age Group, 1990-2021.

Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by Gender, 1990-2021.

Ranking of Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 21 Regions, 2021.

Prevalence and DALYs Attributable to Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 204 Countries, 2021.

Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by SDI Regions, 1990-2021.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the exceptional contributions made by the collaborators of GBD 2021.

Author contributions

Gang Wang and Jin-jie Xu conceived and designed the study. Jin-xin Zheng and Mei-ti Wang were responsible for study methodology. Jin-xin Zheng and Mei-ti Wang were responsible for formal analysis and data visualization. Jin-jie Xu, Lu-yu Ding, Cong-cong Sun and Yu Qiao wrote the original draft and edited the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibilityfor the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis as well as the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

The project is supported by funding from Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (PX2024068), Shanghai Postdoctoral Fund (KJ3-0308-00-0005), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YG2025QNA47), and Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University (Grant No. 23, 2024).

Data availability

All the data can be obtained from the Global Burden of Disease official website (https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in this study does not include confidential or personally identifiable information, and the institutional review board has granted an exemption for this study. Informed consent was not needed as the study did not involve patient-specific data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jin-jie Xu, Lu-yu Ding, Cong-cong Sun, Yu Qiao.

Contributor Information

Jin-jie Xu, Email: sjmedical_xjj@mail.ccmu.edu.cn.

Mei-ti Wang, Email: 15216651601@163.com.

Jin-xin Zheng, Email: jamesjin63@163.com.

Gang Wang, Email: gangwangdoc@ccmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-025-03533-x.

References

- 1.Armocida B, Monasta L, Sawyer S, Bustreo F, Segafredo G, Castelpietra G, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases among adolescents aged 10–24 years in the EU, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:367–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, Armocida B, Beghi M, Iburg KM, et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;16:100341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sciences NAo, Children Bo, Youth, Mental CoFH, Children BDA, Youth. Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. 2019.

- 5.Zolopa C, Burack JA, O’Connor RM, Corran C, Lai J, Bomfim E, et al. Changes in youth mental health, psychological wellbeing, and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2022;7:161–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1218–1239.e1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang MT, Scanlon CL, Del Toro J, Qin X. Adolescent psychological adjustment and social supports during pandemic-onset remote learning: A national multi-wave daily-diary study. Dev Psychopathol. 2023;35:2533–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argabright ST, Tran KT, Visoki E, DiDomenico GE, Moore TM, Barzilay R. COVID-19-related financial strain and adolescent mental health. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;16:100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dedoncker J, Vanderhasselt MA, Ottaviani C, Slavich GM. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: the importance of the vagus nerve for biopsychosocial resilience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;125:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steardo L Jr., Steardo L, Verkhratsky A. Psychiatric face of COVID-19. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woelbert E, Lundell-Smith K, White R, Kemmer D. Accounting for mental health research funding: developing a quantitative baseline of global investments. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, Boerma JT, Collins GS, Ezzati M, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. 2016;388:e19–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2133–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collier J Alcohol and Drugs. 2014.

- 15.Johnson K, Pinchuk I, Melgar MIE, Agwogie MO, Salazar Silva F. The global movement towards a public health approach to substance use disorders. Ann Med. 2022;54:1797–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steeg S, Carr MJ, Mok PLH, Pedersen CB, Antonsen S, Ashcroft DM, et al. Temporal trends in incidence of hospital-treated self-harm among adolescents in Denmark: national register-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaess M, Schnyder N, Michel C, Brunner R, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, et al. Twelve-month service use, suicidality and mental health problems of European adolescents after a school-based screening for current suicidality. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naghavi M, Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm C. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ. 2019;364:l94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jane Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twenge JM. Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;32:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Yang F, Huang N, Zhang S, Guo J. Thirty-year trends of anxiety disorders among adolescents based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Gen Psychiatr. 2024;37:e101288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madigan S, Eirich R, Pador P, McArthur BA, Neville RD. Assessment of changes in child and adolescent screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:1188–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McArthur BA, Racine N, McDonald S, Tough S, Madigan S. Child and family factors associated with child mental health and well-being during COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32:223–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neville RD, Lakes KD, Hopkins WG, Tarantino G, Draper CE, Beck R, et al. Global changes in child and adolescent physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:886–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penninx B, Benros ME, Klein RS, Vinkers CH. How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects. Nat Med. 2022;28:2027–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Klein DN, Hajcak G, Nelson BD. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2022;52:3222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanco-Gandia MC, Montagud-Romero S, Rodriguez-Arias M. Binge eating and psychostimulant addiction. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11:517–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzeo SE, Weinstock M, Vashro TN, Henning T, Derrigo K. Mitigating harms of social media for adolescent body image and eating disorders: a review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:2587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dias I, Hernâni-Eusébio J, Silva R. “How many likes?”: The use of social media, body image insatisfaction and disordered eating. European Psychiatry. 2021;64:S698–S698. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf RT, Puggaard LB, Pedersen MMA, Pagsberg AK, Silverman WK, Correll CU, et al. Systematic identification and stratification of help-seeking school-aged youth with mental health problems: a novel approach to stage-based stepped-care. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:781–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeo G, Reich SM, Liaw NA, Chia EYM. The effect of digital mental health literacy interventions on mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e51268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harriger JA, Evans JA, Thompson JK, Tylka TL. The dangers of the rabbit hole: Reflections on social media as a portal into a distorted world of edited bodies and eating disorder risk and the role of algorithms. Body Image. 2022;41:292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kola L, Kohrt BA, Hanlon C, Naslund JA, Sikander S, Balaji M, et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:535–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Jones N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:813–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maulik PK, Thornicroft G, Saxena S. Roadmap to strengthen global mental health systems to tackle the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luthar SS, Kumar NL, Zillmer N. High-achieving schools connote risks for adolescents: problems documented, processes implicated, and directions for interventions. Am Psychol. 2020;75:983–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machů V, Arends I, Almansa J, Veldman K, Bültmann U. Young adults’ work-family life courses and mental health trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood: a TRAILS study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;59:2227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leibenluft E, Barch DM. Adolescent brain development and psychopathology: introduction to the special issue. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pozzi E, Vijayakumar N, Rakesh D, Whittle S. Neural correlates of emotion regulation in adolescents and emerging adults: a meta-analytic study. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Defoe IN, Khurana A, Betancourt LM, Hurt H, Romer D. Cascades from early adolescent impulsivity to late adolescent antisocial personality disorder and alcohol use disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2022;71:579–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pirkis J, Bantjes J, Gould M, Niederkrotenthaler T, Robinson J, Sinyor M, et al. Public health measures related to the transmissibility of suicide. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:e807–e815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bilello D, Townsend E, Broome MR, Armstrong G, Burnett Heyes S. Friendships and peer relationships and self-harm ideation and behaviour among young people: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11:633–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merikangas AK, Almasy L. Using the tools of genetic epidemiology to understand sex differences in neuropsychiatric disorders. Genes Brain Behav. 2020;19:e12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi P, Yang A, Zhao Q, Chen Z, Ren X, Dai Q. A hypothesis of gender differences in self-reporting symptom of depression: implications to solve under-diagnosis and under-treatment of depression in males. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:589687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhn C. Emergence of sex differences in the development of substance use and abuse during adolescence. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;153:55–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Sugarman DE, Greenfield SF. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li ZZ, Chen YP, Zang XC, Zheng D, Lang XE, Zhou YJ, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the relationship between BMI and recent suicidal attempts in first-episode drug-naive patients with major depressive disorder. Mil Med Res. 2024;11:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mergl R, Koburger N, Heinrichs K, Székely A, Tóth MD, Coyne J, et al. What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? an epidemiological analysis in four European Countries. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao L, Liu J, Yang J, Wang X. Longitudinal relationships among cybervictimization, peer pressure, and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perlis RH, Green J, Simonson M, Ognyanova K, Santillana M, Lin J, et al. Association between social media use and self-reported symptoms of depression in US Adults. JAMA network open. 2021;4:e2136113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee J, Lim JE, Cho SH, Won E, Jeong HG, Lee MS, et al. Association between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms in female workers: An exploration of potential moderators. Journal of psychiatric research. 2022;151:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casement MD, Shaw DS, Sitnick SL, Musselman SC, Forbes EE. Life stress in adolescence predicts early adult reward-related brain function and alcohol dependence. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015;10:416–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu C, Black MM, Richter LM. Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: an estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e916–e922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCoy DC, Peet ED, Ezzati M, Danaei G, Black MM, Sudfeld CR, et al. Early childhood developmental status in low- and middle-income countries: national, regional, and global prevalence estimates using predictive modeling. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fairchild G, Hawes DJ, Frick PJ, Copeland WE, Odgers CL, Franke B, et al. Conduct disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaw DS, Shelleby EC. Early-starting conduct problems: intersection of conduct problems and poverty. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:503–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Risk factors for conduct disorder and oppositional/defiant disorder: evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Degenhardt L, Bharat C, Glantz MD, Sampson NA, Scott K, Lim CCW, et al. The epidemiology of drug use disorders cross-nationally: findings from the WHO’s World Mental Health Surveys. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;71:103–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seidler IK, Tolstrup JS, Bjerregaard P, Crawford A, Larsen CVL. Time trends and geographical patterns in suicide among Greenland Inuit. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Definitions of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm.

Trends in the Prevalence of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 21 Global Regions from 1990 to 2021.

Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by Age Group, 1990-2021.

Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by Gender, 1990-2021.

Ranking of Global Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 21 Regions, 2021.

Prevalence and DALYs Attributable to Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm Across 204 Countries, 2021.

Prevalence and DALYs of Mental Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, and Self-Harm by SDI Regions, 1990-2021.

Data Availability Statement

All the data can be obtained from the Global Burden of Disease official website (https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd).