Abstract

Background

Melanoma is a highly lethal cancer with a poor prognosis. T-cells and melanoma cells play crucial role in shaping the tumor microenvironment, yet their role and impact on prognosis in melanoma is still unclear.

Methods

We analyzed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data for melanoma (GSE200218 and GSE215121) from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and gene expression data from GSE65904 and TCGA-Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (SKCM). We correlated cells with survival outcomes to identify cell subpopulations linked to melanoma prognosis using Scissor. Based on 108 prognostic genes, melanoma patients were stratified into two subgroups. A novel prognostic risk score (PRS) model was constructed using differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from these subgroups.

Results

Our analysis revealed specific T-cell and melanoma subpopulations influencing melanoma prognosis, validated in an independent cohort. Notably, our study was the first to identify MITF + T-cell and M2-cell sub-populations associated with melanoma prognosis. Using 108 prognostic gene markers, we stratified TCGA-SKCM patients into two groups with distinct clinical outcomes, immune cell scores, and carcinogenic profiles. Additionally, we employed 72 machine-learning algorithm combinations to develop a consensus prognosis model based on 174 DEGs from the two prognosis-related subgroups. Ultimately, we created a novel PRS model using 11 genes, which demonstrated accurate prognostic predictive ability in the GSE65904 validation cohort.

Conclusions

This study identified MITF + T-cells and M2-cells as key factors in melanoma prognosis and developed a novel PRS model for accurate prediction. These findings could help guide clinical decision-making for melanoma patients.

Keywords: Tumor immune microenvironment, Prognosis, Melanoma, T-cells, Melanoma cells

Introduction

Melanoma, a malignant skin cancer arising from melanocytes, is characterized by its early metastasis, aggressive behavior, and poor prognosis [1, 2]. Melanocytes are cells that produce the melanin pigment and are found mostly in the skin but also occur in the eyes, ears, leptomeninges, gastrointestinal tract, and oral, genital, and sinonasal mucous membranes [3]. Despite representing a mere 4% of all skin cancers, CM accounts for up to 75% of skin cancer-related deaths [4]. The incidence of melanoma is approximately 25 new cases per 100,000 population in Europe, 30 cases per 100,000 population in the USA, and 60 cases per 100,000 population in Australia and New Zealand [5]. Incidence rates are rising, particularly in White populations.

The traditional treatment of melanoma mainly includes surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Surgical intervention combined with immunotherapy and targeted therapies has significantly improved the survival rate of patients with melanoma [3]. Despite the continuous progress in treatment, a significant proportion of melanoma patient’s prognosis remains unfavorable due to the highly heterogeneous nature of melanom [6]. To this end, elucidating the complex molecular mechanisms of melanoma and developing novel and more precise prognostic tools for melanoma is crucial.

Tumor, stromal and immune cells coexist in a complex ecology called the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [7]. The interaction between immune cells and tumor cells in TIME not only affects the prognosis of tumor patients but may also change the response of tumor patients to immunotherapy [8, 9]. Emerging evidences have reported that TIME plays a key role in the progression and prognosis of melanoma, and is involved in tumor invasion, immune escape, and treatment resistance [10, 11]. Therefore, revealing the TIME landscape in melanoma holds great promise for enhancing the prognosis and developing treatment strategies for melanoma.

TIME profoundly affects T-cell function, which plays a pivotal role in antitumor immune response [12–14]. The infiltration status and phenotypic heterogeneity of T-cells in solid tumor tissues can also directly affect the prognosis of cancer patients and their response to immunotherapy [15–17]. Thus, a more comprehensive understanding of T-cell subpopulations and their functions may help improve the prognosis of patients with malignant tumors. The heterogeneity of melanoma cells may make the progression of melanoma metastasis difficult to control [18]. Nevertheless, the molecular characteristic of melanoma cells subpopulations and their relationship with melanoma prognosis remain of melanoma remain poorly understood.

The utilization of single-cell sequencing data has expedited the comprehension of melanoma. In melanoma, scRNA-Seq has emerged as a pivotal tool for identifying rare cell subpopulations, deciphering immune evasion mechanisms, and uncovering transcriptional programs driving therapeutic resistance. Studies by Tirosh et al. and Veatch et al. utilized scRNA-Seq to map the immunosuppressive landscape of melanoma, revealing critical roles of CD4 + T cell subsets and stromal interactions in disease progression [19, 20]. Furthermore, scRNA-Seq enables the discovery of therapy-responsive cell states, as demonstrated by Huuhtanen et al., who analyzed single-cell data from melanoma patients receiving combined anti-LAG-3 and anti-PD-1 therapy to investigate the drug’s effects at the cellular level [21]. Hanhan Shi et al. integrated single-cell melanoma data with clinical experiments and discovered new therapeutic approaches [22]. These insights underscore the necessity of integrating scRNA-Seq to unravel spatially and temporally resolved molecular mechanisms, ultimately guiding precision oncology strategies.

Inspired by these studies, we attempted to illustrate the prognostic T and melanoma cell subpopulations and to develop a prognostic risk score (PRS) model to predict the prognosis of melanoma based on these subpopulations-related genes. Thus, we utilized scRNA-seq to identify specific T and melanoma subpopulations that impact prognosis in melanoma patients, which was also verified in the validation dataset. We stratified patients into two subtypes based on prognosis-related genes and constructed a new PRS model using the subtype-specific differentially expressed genes, which was also verified in the validation dataset. This study may provide a new perspective for predicting the prognosis of patients with melanoma.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Single-cell RNA sequencing profiles were sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), encompassing 17 melanoma brain metastasis samples and 10 treatment-naïve extracranial metastasis samples from dataset GSE200218, as well as dataset GSE215121, which includes 4 cutaneous samples used for prognostic analysis. The single-cell data were also quality-controlled to remove genes that were expressed in cells with a number of genes lower than 3 and cells with gene expression higher than 7,000, as well as cells with mitochondrial gene expression higher than 15%.Transcriptomic data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), covering transcriptomic and clinical information from 469 melanoma patients. Additionally, to validate the predictive performance of the model, transcriptomic and clinical data from 215 melanoma samples in dataset GSE65904 were also collected from GEO.

scRNA-seq data analysis

The analysis of scRNA-seq data was carried out using the Seurat package (v4.4.0). For cell clustering, the “FindClusters” and “FindNeighbors” functions were applied with parameters set to dim = 30 and resolution = 0.8. Dimensionality reduction was performed using the “RunUMAP” function in Seurat. Cell annotation and subtype visualization were based on the expression patterns of specific marker genes for various T-cell types. Batch effect correction was handled through Seurat’s rpca during sample integration with dims = 1:30. Additionally, a secondary clustering phase was performed with dim = 20 and resolution = 0.5, focusing on T and melanoma cells to assess the diversity of these cell subpopulations.

To gain a better understanding of how T- and melanoma cell subpopulations correlate with the prognosis of the patients, we used Scissor (v2.0.0, alpha = 0.05) to link single-cell data with survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-Seq sample. Based on the survival data, we identified T- and melanoma cells correlation with with prognosis in the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets.

Identification of the specific gene markers

The “Seurat” R package’s “FindAllMarkers” function (with parameters logfc.threshold = 0.7 and only.pos = TRUE) was employed to identify signature hallmark genes (SHGs) in both survival-positive and survival-negative cells. For the subsequent molecular subtype analysis of melanoma, we used the 108 genes that were common to both the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets. The “FindAllMarkers” function was also used to screen the SHGS respectively for the MITF + T and M2 cells.

Additionally, we identified 1883 and 613 shared SHGS between the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets for MITF + T cells and M2 cells, respectively. The clusterProfiler (4.6.2) R package was utilized to perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses for these 1883 and 613 SHGS. To identify markers, MITF + T and M2 cell markers were further filtered based on the criteria of pct.2 ≥ 0.05 and avg_log2FC ≥ 2, resulting in the identification of 11 markers for MITF + T cells and 19 markers for M2 cells. Subsequently, these markers were combined to quantify the relative abundance of MITF + T and M2 cells using the ssGSEA algorithm in the TCGA-SKCM bulk sample. To assess the prognostic impact of these two subpopulations, overall survival (OS) curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method in the R survival package (v3.5-7).

Constructing consensus clustering based on 108 prognostic genes

The FactoMineR (2.9) R package uses the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) algorithm to perform the principal component analysis (PCA). Using 108 shared genes, consensus clustering was carried out on the TCGA-SKCM dataset using the ConsensusClusterPlus (1.62.0) R package(Clustering algorithm: k-means). We selected an optimum k value in consideration for stability and clustering performance. A suitable k = 2 was chosen based on consensus CDF and delta area. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were obtained between two subtypes using “limma” R package, with |logFC|>=1 and adj.P.Val < 0.05. For assessment of the clinical performance of the two subtypes, we examined the differences in patient prognosis as well as other clinical characteristics, such as ESTIMATE score, immune score, stromal score and tumor immune cell infiltrations.

Development and validation of PRS model

Univariate Cox analysis was conducted on the DEGs using the coxph function from the survival package, that led to identification of 174 prognosis-related genes (p-value < 0.01). To develop a consensus prognostic risk score (PRS) model, we integrated 8 classical algorithms (random forest i.e. RFS, LASSO COX, GBM, ridge regression, CoxBoost, Stepback Cox, Stepboth Cox, and elastic network i.e. Enet) into a combinations of 72 different machine-learning algorithms, where Enet is divided into 3 classifiers according to the α-index. The TCGA-SKCM dataset was randomly divided into training and testing cohort, with GSE65904 serving as an additional testing cohort. We further calculated the mean AUC and C-index for each algorithm across the two testing cohorts, and selected the best consensus PRS model based on these average.

To assess the predictive value of the PRS model, melanoma patients were divided into high-PRS and low-PRS groups based on the median risk score. Receivers operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and the area under curve (AUC) was calculated using the R package pROC (v1.18.5). Using Kaplan-Meier curves, we generated the survfit function from survival (v3.5.8) package. KM curves were to evaluate overall survival differences between high- and low-PRS groups. The GSE65904 datasets was employed to validate the stability of the PRS model. For clinical applicability, a nomogram was developed using ‘nomogram’ function from the “rms” package to predict survival probability. Calibration curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were then applied to confirm whether the nomogram could serve as an optimal model for clinical decision-making.

Tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) infiltration analysis

We used ESTIMATE (http://www.mdanderson.org) to calculate stromal and immune scores. Additionally, the relative infiltration of immune cell types was analyzed using TIMER (http://timer.comp-genomics.org). Differences in tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) infiltration were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The ggplot2 package was utilized to visualize the TIME infiltration across different groups.

Results

Identification of cell subgroups by single-cell analysis

We obtained 139,073 cells derived from 17 melanoma brain metastases samples and 10 treatment-naïve extracranial metastases using scRNA-seq data of GSE200218. The screened cells were clustered into 36 clusters and annotated 9 cell types, including NK/T-cells, B cells, dendritic/macrophages, epithelial cells, fibroblast, T-cells, endothelial cells, melanoma cells, pDCs and plasma cells (Fig. 1A–C). Based on our observations, cells from different samples were integrated in both GSE200218 and GSE215121, indicating that there were no marked batch effects among different samples during clustering (Fig. 1D, H). Additionally, the scRNA-seq data from GSE215121 was analyzed to identify 28 clusters, which were classified into 8 distinct cell types: NK/T-cells, B cells, Fibroblast T-cells, Macrophages, Endothelial cells, Melanoma cells, pDCs, and plasma cells (Fig. 1E–G). The presence of various cell types suggested that melanoma progression is influenced by a complex tumor microenvironment. Given the importance of T-cells and melanoma cells in immune response, this study further investigated the molecular characteristics and prognostic significance of these cells in melanoma.

Fig. 1.

Identification of cell types by single-cell analysis. A UMAP plot colored by 36 clusters of cells in GSE200218. B The annotation of each cluster based on marker analysis in GSE200218. C Annotated 9 cell types in GSE200218. D UMAP diagram of 27 samples in GSE200218. E UMAP plot colored by 28 clusters of cells in GSE215121. F The annotation of each cluster based on marker analysis in GSE215121. G Annotated 8 cell types in GSE215121. H UMAP diagram of 11 samples in GSE215121

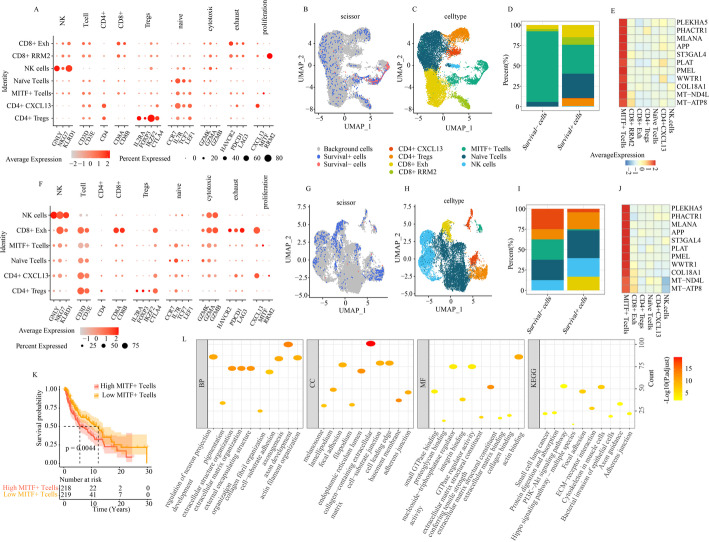

Identification of T-cell subpopulations from single-cell analysis

Next, we analyzed 15,537 NK/T-cells scRNA-seq data from GSE200218. Based on T-cell marker genes, these T-cells were clustered into seven subtypes: CD8 + Exh, CD8 + RRM2, CD4 + CXCL13, NK cells, CD4 + Tregs, Naïve T-cells and MITF + T-cells (Fig. 2A, C). Interestingly, we identified a previously unreported population of MITF + T-cell populations, with upregulated expression of MITF (Fig. 2A). MITF has been recognized as a key melanocyte regulator in melanoma, and is linked to overall survival in melanoma patients [19, 23, 24]. To further elucidate the relationship between T-cell subtypes and patient prognosis, we utilized scissor to map single-cell data to survival data via the TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-Seq dataset. Our analysis revealed 522 cells associated with favorable prognosis (survival + cells), and 104 cells associated with poor prognosis (survival- cells) (Fig. 2B). Also, we observed significant differences in the distribution of the seven cell types between survival + cells and survival- cells. In particular, MITF + T subpopulation had significant proportion in survival- cells compared with survival + cells (Figure 2D). We also found that 11 markers of MITF + T-cell subpopulation including PLEKHA5, PHACTR1, MLANA, APP, ST3GAL4, PLAT, PMEL, WWTR1, COL18A1, MT − ND4L and MT-ATP8 (Fig. 2E). Of these, seven markers - PHACTR1, MLANA, APP, ST3GAL4, PLAT, PMEL and WWTR1 were found to be correlated with tumor prognosis [25–31]. These findings suggest that MITF + T-cells were negatively correlated to prognosis of SKCM patients.

Fig. 2.

Identification of T cell subpopulations from single-cell analysis. A The annotation of each cluster of T cell subpopulations based on marker analysis in GSE200218. B The scissor employed to correspond single-cell data of GSE200218 to survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-seq sample. C Annotated 7 T cell subpopulations in GSE200218. D The proportion of different T cell subpopulations in survival + cells and survival- cells based on the GSE200218. E Heatmap of specific makers of MITF + T subpopulation in GSE200218. F The annotation of each cluster of T cell subpopulations based on marker analysis in GSE215121. G The scissor employed to correspond single-cell data of GSE215121 to survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-seq sample. H Annotated 7 T cell subpopulations in GSE215121. I The proportion of different T cell subpopulations in survival + cells and survival- cells based on the GSE215121. J Heatmap of makers of MITF + T subpopulation in GSE215121. K Survival analysis between high MITF + T cells and low MITF + T cells in TCGA-SKCM. L Functional enrichment analysis of SHGs of MITF + T cell populations shared by the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets

To confirm the findings, we conducted a validation analysis using scRNA-seq data derived from GSE215121 dataset. Upon clustering, T-cells were segregated into into six cell types: NK cells, CD8 + Exh, CD4 + CXCL13, MITF + T-cells, naïve T-cells, and CD4 + Tregs. We also carried out survival analysis (Fig. 2F, H). Consistent with the results of GSE200218, we discovered that significant differences in the distribution of the six cell types between survival + and survival- cells, with a higher proportion of MITF + T-cells in survival- cells compared to survival + cells (Fig. 2G, I). Interestingly, all 11 markers were highly expressed in the MITF + T-cell populations in GSE215121 as well upon compared with CD8 + Exh, CD4 + Tregs, naïve T-cells, CD4 + CXCL13, and NK cells (Fig. 2J). To further validate the negative correlation between MITF + T-cells and prognosis in SKCM patients, we assessed the abundance of MITF + T-cell subpopulations in TCGA-SKCM based on these 11 markers. The samples were then divided into high and low MITF + T-cell groups. Survival analysis revealed that patients with a higher abundance of MITF + T-cells had a significantly worse prognosis compared to those with lower levels (Fig. 2K). Based on these findings, we concluded that the MITF + T-cell subpopulation is strongly associated with the prognosis of melanoma patients.

Based on these findings, we proposed that the MITF + T-cell subpopulation could play a critical role in melanoma patients. To explore this further, we identified 1,883 shared signature hallmark genes (SHGs) of MITF + T-cells from both the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were primarily involved in several important biological processes, including axon development, organization of the extracellular structure and matrix, endoplasmic reticulum lumen, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix structural components, actin binding, focal adhesion, ECM-receptor interaction, and cytoskeletal functions in muscle cells (Fig. 2L).

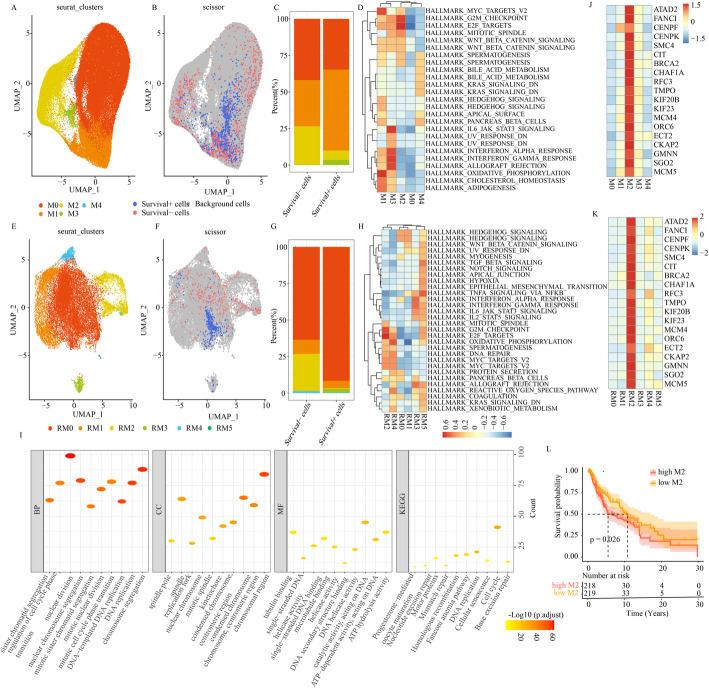

Identification of melanoma cell subpopulations by single-cell analysis

Prior investigations also reported that melanoma cells critically regulated melanoma progression of melanoma metastasis [19]. Based on scRNA-seq data derived from GSE200218, we identified 95,450 Melanoma cells and sub-classified them into five clusters, namely M0, M1, M2, M3, M4, which revealed the prevalence of heterogeneity among melanoma cells (Fig. 3A). To better elucidate the relation between melanoma subpopulations with patients prognosis, we employed scissor to correlate single-cell data with survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-Seq sample. The data revealed 920 survival + cells and 787 survival- cells (Fig. 3B). In our analysis, M2 macrophages had significantly higher proportion in survival- cells than survival + cells, while M1 were more abundant in survival + cells than survival- cells (Fig. 3C). Additionally, GSVA analysis of the five clusters revealed that M2 were primarily enriched in cell cycle-related function, including G2M checkpoint and E2F targets (Fig. 3D). To validated these findings we analyzed scRNA-seq data derived from GSE215121 (Fig. 3E), and observed consistent result i.e. a subpopulation (RM2) related to cell cycle was significantly more prevalent in survival- cells compared with survival + cells (Fig. 3F, G). The GSVA results of six clusters also indicated that RM2 was significantly associated with cell cycle-related function, including G2M checkpoint and E2F targets (Fig. 3H). However, we could not identify a subpopulation in GSE215121 dataset that matched the functional profile of M1, suggesting heterogeneity among melanoma cells.

Fig. 3.

Identification of melanoma cell subpopulations by single-cell analysis. A Annotated 5 melanoma cell subpopulations in GSE200218. B The scissor employed to correspond single-cell data of GSE200218 to survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-seq sample. C The proportion of different melanoma cell subpopulations in survival + cells and survival- cells based on the GSE200218. D GSVA results of 5 clusters in GSE200218. E Annotated 6 melanoma cell subpopulations in GSE215121. F The scissor employed to correspond single-cell data of GSE215121 to survival data via TCGA-SKCM bulk RNA-seq sample. G The proportion of different melanoma cell subpopulations in survival + cells and survival- cells based on the GSE215121. H GSVA results of 6 clusters in GSE215121. I Functional enrichment analysis of highly expressed genes of M2 shared by the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets. J Heatmap of makers of M2 in GSE200218. K Heatmap of makers of M2 in GSE215121. L Survival analysis between high M2 cells and low M2 cells in TCGA-SKCM

To further investigate the function of M2 subpopulations, we identified 19 markers in M2 subpopulations including ATAD2, FANCI, CENPF, CENPK, SMC4, CIT, BRCA2, CHAF1A, RFC3, TMPO, KIF20B, KIF23, MCM4, ORC6, ECT2, CKAP2, GMNN, SGO2, and MCM5 (Fig. 3J). Among these, 14 genes—CENPF, CENPK, SMC4, CHAF1A, RFC3, TMPO, KIF20B, KIF23, MCM4, ORC6, ECT2, CKAP2, GMNN and MCM5 are involved in cell cycle regulation. Based on this, we we hypothesized that M2 subpopulations may influence melanoma cells proliferation by modulating these cell cycle-related genes, thereby affecting patient prognosis. Interestingly, these 19 markers were also significantly upregulated in the RM2 subpopulation in the GSE215121 (Fig. 3K), further suggesting that this subpopulation we obtained mimics M2 cells identified in the GSE215121 dataset.

We identified 613 signature hallmark genes (SHGs) shared between the M2 (GSE200218) and RM2 (GSE215121) subpopulations. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that these 613 genes were primarily involved in cell cycle-related biological processes such as nuclear division, nuclear chromosome segregation, DNA replication, chromosome segregation and chromosomal region (Fig. 3I). To further verify if M2 subpopulation negatively correlated with prognosis in SKCM patients, we evaluated abundance of M2 subpopulation in TCGA-SKCM dataset using 19 markers. Survival analysis showed that a higher M2 subpopulation was significantly correlated with poor prognosis than with low M2 subpopulation (Fig. 3L). These findings suggest that the M2 subpopulation plays a key role in modulating the outcome in melanoma patients.

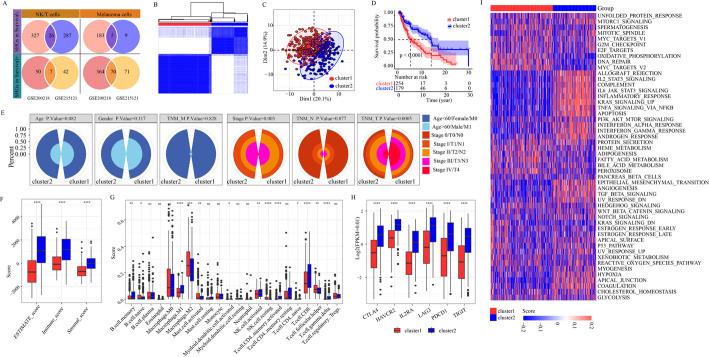

Establishment of two subcategories based on prognostic genes

In this study, we employed single-cell and TCGA analysis to evaluate the infiltration status of T-cell and melanoma subpopulations in melanoma patients. Our findings confirmed the presence of MITF + T and M2 subpopulations, both of which are linked to the prognosis, using single-cell data supported by phenotypic guidance from bulk data. These results may contribute to the development of targeted cell therapies and the identification of reliable prognostic markers. Additionally, we identified 77 and 31 SHGs from the survival + and survival- cells, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Establishment of 2 subcategories based on prognostic genes. Venn diagram of the SHGs in survival + and survival- cells shared by the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets. B The consensus matrix heatmap of K = 2. C Optimal clustering of melanoma patients into two subgroups. D Survival analysis for two clusters based on 108 SHGs. E Clinical information of the two clusters. F ESTIMATE score, Immune score and Stromal score between the two clusters. G Differential analysis of immune cell types between the two clusters. H The expression of 6 immune checkpoint genes between the two clusters. I GSVA analysis of two clusters

We performed molecular subtype analysis using 108 SHGs, which resulted in the optimal clustering of melanoma patients into two subgroups: 276 cases in cluster 1, and 191 cases in cluster 2 (Fig. 4B). Principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed the presence of these two distinct subtypes (Fig. 4C). The prognostic evaluation revealed significant differences in patient outcomes in these clusters (Fig. 4D), and found that patient in cluster 2 experienced better prognosis. Additionally, a comparison of clinical information between the two clusters showed differences in stage and TNM T-stage, but no significant differences were observed in age, gender, TNM - M and N stage (Fig. 4E). Further analysis revealed significant difference in the ESTIMATE, immune and stromal scores between the two clusters, with cluster 2 exhibiting higher immune cell and stromal cell scores (Fig. 4F). These higher scores were associated with better prognostic outcome in cluster 2. Using the CIBERSORT algorithm, we assessed the infiltration of 22 immune cell types in the cluster 1 and cluster 2. We revealed that NK activated cells, CD8 + T-cells, CD4 + memory activated T-cells and M1 Macrophages had the higher abundance in cluster 2, while M2 macrophages had the higher abundance in cluster 1 (Fig. 4G). These results suggest distinct TIME infiltration characteristics between the two clusters. Moreover, the expression of six immune checkpoint genes between the cluster 2 was evaluated, all of them were significantly upregulated in the cluster 2 (Fig. 4H). These differences in TIME scores and immune checkpoint expression suggest that diverse TIME profile play a key role in segregating the two clusters. Finally, GSVA analysis using 50 SHGs indicating significant differences in the carcinogenic profiles of the two clusters, further highlighting the involvement of the 108 SHGs in regulating TIME in melanoma patients. GSVA analysis showed that cluster 1 was significantly enriched in key biological events such as oxidative phosphorylation, DNA repair, and MYC targets, while the clusters 2 exhibited significant enrichment in the immune reaction, namely IL2, STAT5 signaling, IL6, JAK-STAT3 signaling, inflammatory response, K-RAS signaling and activation of TNF-a signaling via NF-kB (Fig. 4I).

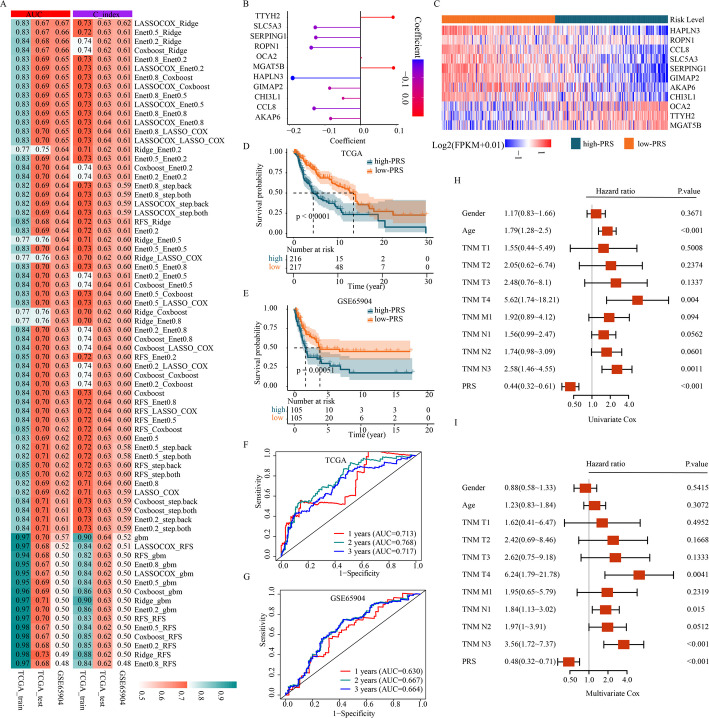

Construction and validation of eleven gene’s signature

To develop a more pragmatic PRS model for clinical applications, we identified 540 DEGs between the two distinct subtypes. Among these, 174 genes were found to be significantly correlated with OS in the TCGA cohort (p < 0.01). To develop a consensus prognosis model, we combined 8 classical algorithms-random forest (RFS), LASSO COX, GBM, ridge regression, CoxBoost, Stepback Cox, Stepboth Cox, and elastic network (Enet)-into 72 different machine-learning algorithm combinations. The TCGA-SKCM dataset was randomly split into training and testing cohorts, with GSE65904 used as an additional testing cohort. Based on the average AUC and C-index across the three cohorts, the PRS model built using the LASSO COX and Ridge algorithms was selected as the optimal consensus model (Fig. 5A). This model was constructed using 11 markers: HAPLN3, ROPN1, CCL8, SLC5A3, SERPING1, GIMAP2, AKAP6, CHI3L1, OCA2, TTYH2, and MGAT5B (Fig. 5B, C). Each patient’s PRS was calculated based on gene expression levels weighted by the corresponding regression coefficients. Using the median PRS as a threshold, patients were categorized into high- and low-PRS groups. The survival analysis showed a significant difference in outcomes between these groups, with the high-PRS group exhibiting worse prognosis in the TCGA-SKCM cohort (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5D). This result was further validated in the GSE65904 cohort (p = 0.00051) (Fig. 5E). To further assess the model’s performance, we performed a time-dependent ROC analysis in both the TCGA and GSE65904 cohorts. In the TCGA cohort, the AUC values for predicting 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS were 0.713, 0.768, and 0.717, respectively (Fig. 5F). Similarly, in the GSE65940 cohort, the corresponding AUCs were 0.630, 0.667, and 0.664 (Fig. 5G). Univariate and Multivariate Cox Forest analysis revealed that the PRS, along with TNM T- and N-stage, risk scores, were independent predictors of OS compared to other clinical factors (Fig. 5H, I).

Fig. 5.

Construction and validation of 11 gene signature. A total of 72 different models were built by machine learning and their AUCs and C-indexes were tested in each set. B Coefficients of the 11 genes included in the signature. C Heatmap of the 11 genes between the high- and low-PRS groups. D Survival analysis of melanoma patients with high-and low-PRS groups in TCGA-SKCM. E Survival analysis of melanoma patients with high- and low- PRS groups in GSE65904. F ROC curves to predict 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rate in TCGA-SKCM. G ROC curves to predict 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rate in GSE65904. H Forest plot based on univariate Cox Forest analysis. I Forest plot based on multivariate Cox Forest analysis

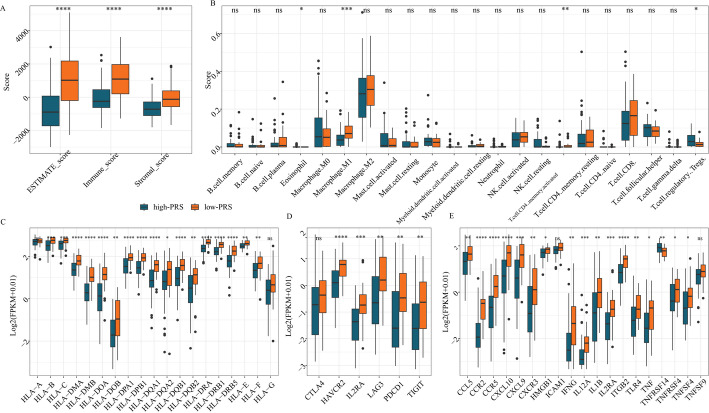

The ESTIMATE, immune, and stromal scores showed significant differences between the high- and low- PRS groups (Fig. 6A). Additionally, the CIBERSORT algorithm was used to assess the proportions of 22 tumor-infiltrating immune cells between these two groups. Notably, the infiltration levels of eosinophils, M1 macrophages, activated CD4 memory T-cells, and regulatory T-cells (Tregs) varied significantly between the high- and low- PRS groups (Fig. 6B). The expression levels of 19 HLA genes, 6 immune checkpoint genes, and 19 immune-related genes were compared between the groups (Fig. 6C–E). Except for HLA-A, HLA-G, CTLA4, TNFSF9, and ICAM1, the expression of the remaining genes showed significant differences between the high- and low- PRS groups.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of immune characteristics between groups with high-PRS and low-PRS groups. ESTIMATE score, Immune score and Stromal score between high-and low-PRS groups. B Quantification of different immune cell infiltration level between high-and low-PRS groups. C The expression of HLA genes between high- and low-PRS groups. D The expression of immune checkpoint genes between high- and low-PRS groups. E The expression of immune genes between high- nd low-PRS groups

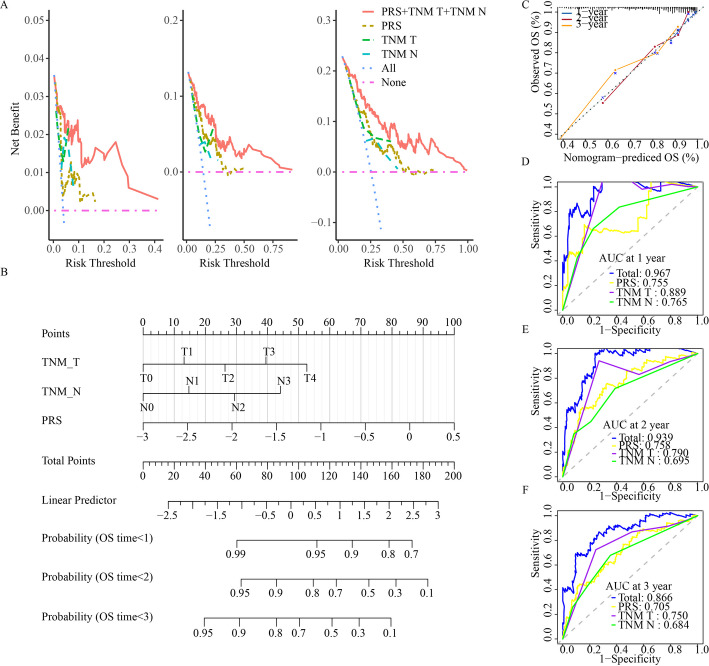

Based on decision curve assessment, the combination of three independent prognostic factors significantly improved overall clinical benefit compared to the clinicopathological alone in the TCGA-SKCM cohort (Fig. 7A). We then developed a nomogram incorporating the three identified prognostic factors to predict the 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates of SKCM patients (Fig. 7B). Each patient was assigned a total score by summing the points from individual prognostic factors, with higher total scores indicating a poorer prognosis. The calibration plot for the nomogram showed strong alignment between the predicted and actual outcomes (Fig. 7C). To further assess the model’s performance, we conducted a time-dependent ROC analysis. The AUC values for the nomogram at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year overall survival (OS) were 0.967, 0.939, and 0.866, respectively, demonstrating that the nomogram outperformed individual factors (Fig. 7D–F). These results suggest that the nomogram offers high accuracy in predicting SKCM patient prognosis.

Fig. 7.

Construction of the nomogram. A Decision curves to reveal the potential clinical application valuation of the nomogram. B Nomogram for predicting 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year survival rate of melanoma patients. C The calibration curves for 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival. D ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting the probability of 1-year survival. E ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting the probability of 2-year survival. F ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting the probability of 3-year survival

Discussion

Melanoma is a complex and aggressive tumor characterized by highly diverse genetic patterns and a poor prognosis. As new treatment methods for melanoma continue to emerge, there is an urgent need to develop an effective and reliable approach for monitoring its prognosis. Recently, studies have documented the relevance of immune cell subpopulations and associated genes with the prognosis of various cancers, including melanoma [13, 14, 18]. We know that multi-omics techniques such as genomics, transcriptomics, miRNAomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have transformed the understanding of various diseases, including diabetes, stroke, and cancer [32]. In this study, we investigated the latest insights on the roles of T-cell and melanoma cell subpopulations, and their associated genes in melanoma, with an aim to improve our understanding and prognostic management of this complex disease through the integration of multi-omics analysis. In addition, this study demonstrated the heterogeneity of TIME in different subtypes and risk groups of melanoma based on T and melanoma cell subpopulations, which might help reveal the immunological and biological mechanisms of poor prognosis.

TIME has a crucial impact on tumor immunotherapy, which in turn affects the survival of cancer patients [17]. TIME significantly influences T-cell activity and function, with T-cells also being recognized for their critical role in immune surveillance and tumor elimination [33, 34]. Recent studies have shown that the presence and activation of T-cells acts as a potential prognostic indicator in a variety of malignant tumors [35]. As the anti-tumor immunity of T-cells has rarely been studied in melanoma, it is important to investigate the relationship between T-cell subpopulations and T-cell related genes in the prognosis of melanoma. Therefore, we annotated T-cell subpopulations based on melanoma GSE200218 datasets and found a previously unreported melanocyte master regulator (MITF)+ (positive) T-cell subpopulation that affects prognosis in melanoma patients, which was also verified in GSE215121 datasets. Subsequently, we identified 11 markers in MITF + T subpopulations, including PLEKHA5, PHACTR1, MLANA, APP, ST3GAL4, PLAT, PMEL, WWTR1, COL18A1, MTND4L and MTATP8. Among these, PHACTR1, MLANA, APP, ST3GAL4, PLAT, PMEL and WWTR1, have been found to be associated with tumor prognosis. Additionally, we also evaluated the MITF + T-cell subpopulations in TCGA samples based on these 11 markers and found that the abundance of MITF + T-cell populations was significantly correlated with the survival of melanoma patients. Studies have also reported the importance of the MITF in melanoma. MITF, as the target of melanoma amplification, is widely expressed in metastatic malignant melanoma and is associated with overall survival in patients with melanoma. The results reported in previous studies were in concordance with the results of our study, which further illustrates the reliability of the results of this study. Given the above, we conclude that MITF + T-cell population is closely related to the prognosis of patients with melanoma, and will continue to explore the effect of MITF + T-cell populations on the prognosis of patients with melanoma. In light of these findings, we conclude that the MITF + T cell population is strongly associated with the prognosis of melanoma patients. However, this study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Primarily, we did not perform additional validation to confirm the presence of MITF + T cells within our clinical specimens. This specific cellular subpopulation, while theoretically implicated in our proposed mechanism, requires direct histological evidence for definitive confirmation. To address this gap, our future investigations will incorporate comprehensive co-staining experiments on tumor tissue sections, which will enable simultaneous visualization of MITF expression and T cell markers. Such spatial resolution analysis will be crucial for validating our current findings and further elucidating the biological significance of these immune cell subsets in tumor microenvironment. Additionally, further investigation will be pursued to explore the role of MITF + T cells on the patient outcomes.

Smalley et al. reported that single-cell sequencing analysis showed that melanoma cell populations account for a large proportion of brain metastasis samples derived from melanoma patients. They also found that melanoma cell populations are the most diverse, with cells from individual melanoma patients forming distinct clusters, whereas other cell subtypes from different patients tend to cluster together [36]. The heterogeneity of melanoma cell populations may contribute to the progression of melanoma to metastatic phase making it more difficult to treat and control [18]. To the best of our knowledge, only a handful of studies have explored the role of melanoma cell populations and their related genes in the melanoma prognosis. Thus, identifying prognostic cell subpopulations from a new perspective of melanoma cell populations is of great significance for improving the survival outcome of melanoma patients. In our study, we annotated melanoma cell subpopulations based on melanoma GSE200218 datasets and found a previously unreported M2 cell subpopulation that affects prognosis in melanoma patients, which was also verified in GSE215121 datasets. The GSVA results showed that these M2 cell subpopulations were mainly enriched in cell cycle-related functions including G2/M checkpoints and E2F targets. Moreover, nineteen markers were identified in the M2 subpopulation. Among these, CENPF, CENPK, SMC4, CHAF1A, RFC3, TMPO, KIF20B, KIF23, MCM4, ORC6, ECT2, CKAP2, GMNN, and MCM5 have been reported to play important roles in cell cycle regulation. Furthermore, we evaluated the abundance of M2 cell subpopulations in TCGA samples based on 19 markers, and found that the abundance of M2 cell subpopulations was significantly associated with survival of the melanoma patients. Moreover, functional enrichment analysis showed that these genes of M2 cell subpopulations were mainly enriched in biological events associated with the cell cycle, including nuclear division, and nuclear chromosome segregation, DNA-templated DNA replication, DNA replication, chromosome segregation and chromosomal region. Based on these findings, we speculated that M2 cell subpopulations might be involved in the prognosis of melanoma patients via regulation of the cell cycle progression.

Given the limited research on the antitumor immune effects related to T-cells and melanoma subpopulations, our study is the first attempt to identify specific T-cell and melanoma subpopulations that can serve as predictors of melanoma prognosis. We first obtained 108 specific highly expressed genes related to prognosis of T and melanoma cell populations from the GSE215121 and GSE200218 datasets. Subsequently, 276 melanoma patients were divided into two subgroups based on these genes. The results showed significant differences in the prognosis between the two subgroups of melanoma patients. Furthermore, tumor immune cell infiltration, ESTIMATE score, immune score, stromal score, immune checkpoint genes, and GSVA analysis were significantly different between the two subgroups of melanoma patients. There were significantly different in terms of prognosis and immunity between the two subgroups, indicating that the melanoma molecular subtype was successfully constructed. To develop a reasonable as well as convenient scoring model for clinical applications, a combination of 72 machine-learning algorithm used to construct a melanoma risk prediction model using DEGs in the above two melanoma subgroups. A total of 11 genes were identified to construct PRS model, including HAPLN3, ROPN1, CCL8, SLC5A3, SERPING1, GIMAP2, AKAP6, CHI3L1, OCA2, TTYH2 and MGAT5B. Using the median prognostic risk score (PRS) as a threshold, we classified melanoma patients into high- and low- PRS groups with different clinical outcome, immune cell score and oncogenic profiles. In addition, This PRS model demonstrated accurate prognostic predictive capability in the GSE65904 validation cohort. Ultimately, we developed a nomogram to estimate survival probability, which showed exceptional accuracy in predicting the prognosis of SKCM patients. Our findings indicate that the PRS model can reliably predict melanoma patient survival, with distinct clinical outcomes, immune cell scores, and carcinogenic profiles observed between the high- and low-PRS groups. The successful development of this PRS model offers a novel approach for improving melanoma patient prognosis.

To our knowledge, nine out of the eleven genes used to develop the PRS model have been linked to melanoma progression. For example, hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 3 (HAPLN3) is known for its role in tumor progression and has recently been suggested as a new biomarker for melanoma prognosis and immune status [37, 38]. Recent studies have shown that HAPLN3 may be used as a new biomarker to guide the prognosis and immune status of melanoma patients [39, 40]. Ropporin-1 (ROPN1), a cancer-associated antigen, is commonly expressed in melanoma and triggers significant humoral immune responses [41]. Additionally, numerous studies have highlighted that CCL8 expression is associated with immune cell infiltration and serves as a marker for poor melanoma prognosis [42]. The expression of serine protease inhibitor family G1 (SERPING1) gene has been reported to be elevated and its abnormal expression was correlated with the immune re-induction response of melanoma. Although serum chitinase-3-like-1 protein (CHI3L1) may be used for melanoma diagnosis but in combination with other markers, as alone it’s assessment is not good due to no correlation between CHI3L1 and clinicopathological parameters in melanoma [43]. CHI3L1, a new type of Th1/CTL response regulator, is used as a therapeutic target to improve the anti-tumor immunity in general [44, 45]. Lastly, oculocutaneous albinism type 2 (OCA2) is a recognized melanoma susceptibility gene, with its mutations potentially contributing to susceptibility in non-pigmented or low-melanoma cases [46, 47]. Among these, SLC5A3, GIMAP2, AKAP6, TTYH2, and MGAT5B have not been previously associated with melanoma. Information on the role of these genes in cancers is scarce. For instance, SLC5A3 is known to be upregulated in cervical cancer, and its expression level correlates with both survival rates and progression-free intervals in cervical cancer [48]. SLC5A3 retains inositol content and activates Akt-mTOR pathway to regulate proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells [49]. GIMAP2 is identified as an immune-related gene linked to better prognosis in sarcomas. Additionally, reducing GIMAP2 levels notably affects the growth, migration, and invasion capabilities of low-grade glioma cells [50, 51]. Polymorphism in the kinase-anchored protein 6 (AKAP6) gene has been reported to be closely linked with glioma susceptibility and prognosis [52]. Genetic variations in KAP6 may have transcriptional regulatory roles and are associated with an increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer [53]. Twenty family member 2 (TTYH2) has been reported to be upregulated in osteosarcoma, where it plays a role in regulating the invasion and migration of osteosarcoma cells [54]. TTYH2 has been found to significantly influence tumor cells by modulating LRRC8A-independent volume-regulated anion channels [55]. As a glycogen-related gene, MGAT5B is aberrantly expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is linked to its metastasis [56]. Therefore, additional research is needed to thoroughly explore the biological functions of SLC5A3, GIMAP2, AKAP6, TTYH2, and MGAT5B. Overall, this study provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms of melanoma and suggests potential therapeutic strategies for managing malignant tumors.

Despite the promising results, our study has some limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, since our research relied on publicly available databases, it is not yet clear how our findings apply to larger clinical patient samples. This preliminary confirmation of reliability at the clinical level does not fully establish the model’s practical value in clinical settings. Secondly, we did not conduct experimental studies to validate the functions of T and melanoma cell subpopulations and related genes. Specifically, co-staining experiments would be essential to directly demonstrate the coexistence of melanoma and T cell markers within the same cell population. In addition, spatial transcriptomics technologies, such as the 10X Genomics Xenium platform, could further clarify the spatial distribution and co-expression patterns of MITF and immune markers (e.g., CD8A) in melanoma tissues. Due to current technical and resource limitations, we were unable to incorporate such analyses into the present study. Nevertheless, we highlight these approaches as important directions for future work to strengthen and validate our findings.

In summary, we identified specific T and melanoma cell subpopulations that influence melanoma prognosis and developed a new PRS model using 11 genes for predicting patient outcomes. These cell subpopulations and related genes offer valuable insights into melanoma prognosis and can aid in clinical decision-making. This study introduces a novel risk model for melanoma prognosis and sheds light on the disease’s heterogeneity and its interaction with the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME).

Conclusions

Melanoma, a deadly cancer with a poor prognosis, involves T-cells and melanoma cells in shaping the tumor microenvironment, though their impact on the prognosis remains unclear. Using scRNA-seq and gene expression data from GEO and TCGA databases, this study identified key cell subpopulations associated with patient outcomes. The Prognostic Risk Score (PRS) model, constructed using subtype-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs), achieved the highest predictive accuracy and validated in multiple cohorts. The model was constructed from 11 marker genes linked to melanoma progression. The PRS model stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes (p < 0.0001), offering valuable insights for improving clinical decision-making in melanoma care. Notably, MITF + T-cells and M2 cells were identified as key prognostic factors. Further clinical trials and experimental researches are necessary to confirm the predictive value of our PRS model.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants and staff who help us in the process of this study.

Abbreviations

- CM

Cutaneous melanoma

- DALYs

Disability-adjusted life-years

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- GSVA

Gene Set Variation Analysis

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- HAPLN3

Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 3

- OS

Overall survival

- PRS

Prognostic risk score

- ROPN1

Ropporin-1

- SHGs

Signature hallmark genes

- SKCM

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TIME

Tumor immune microenvironment

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

Author contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.Z., C.S., F.G., and G.Y.; methodology, C.S. and L.M.M.; software, L.M.M.; formal analysis, H.W.Z., and C.S.; investigation, J.L., W.L., and S.Z.; data curation, J.L., W.L., and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W.Z., and C.S.; writing—review and editing, F.G., and G.Y.; funding acquisition, H.W.Z. and G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang, grant number [2023C03101] and the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission, grant number [2025KY938].

Data availability

In this study, all datasets were obtained from publicly available databases. We utilized The Cancer Genome Atlas Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (TCGA-SKCM) dataset and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets (GSE200218, GSE215121, and GSE65904). The TCGA-SKCM dataset was downloaded from the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). GEO datasets are publicly available and can be accessed through the GEO repository by searching the respective accession numbers. The download links are provided below. Additional details are also provided in the main text. GSE200218: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200218). GSE215121: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE215121). GSE65904: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE65904). TCGA-SKCM: (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-SKCM).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huiwen Zheng and Chen Shen contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Ding Y, Zhao Z, Cai H, Zhou Y, Chen H, Bai Y, et al. Single-cell sequencing analysis related to sphingolipid metabolism guides immunotherapy and prognosis of skin cutaneous melanoma. Front Immunol. 2023. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1304466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Zhang C, He J, Lai G, Li W, Zeng H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of single cell and bulk RNA sequencing reveals the heterogeneity of melanoma tumor microenvironment and predicts the response of immunotherapy. Inflamm Res. 2024;73:1393–409. 10.1007/s00011-024-01905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM, Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2023;402:485–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, Massi D, Scolyer RA. The 2018 world health organization classification of cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal melanoma: detailed analysis of 9 distinct subtypes defined by their evolutionary pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:500–22. 10.5858/arpa.2019-0561-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis LE, Shalin SC, Tackett AJ. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20:1366–79. 10.1080/15384047.2019.1640032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Joshua AM, Li Y, O’Meara CH, Morris MJ, Khachigian LM. Targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and small molecules and peptidomimetics as emerging immunoregulatory agents for melanoma. Cancer Lett. 2024;586:216633. 10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Wang Y, Hu Q, Liu Y, Qi X, Tang Z, Hu H, Lin N, Zeng S, Yu L. Unveiling tumor immune evasion mechanisms: abnormal expression of transporters on immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1225948. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1225948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adegoke NA, Gide TN, Mao Y, Quek C, Patrick E, Carlino MS, Lo SN, Menzies AM, da Pires I, Vergara IA, et al. Classification of the tumor immune microenvironment and associations with outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with immunotherapies. J Immunother Cancer. 2023. 10.1136/jitc-2023-007144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barras D, Ghisoni E, Chiffelle J, Orcurto A, Dagher J, Fahr N, et al. Response to tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte adoptive therapy is associated with preexisting CD8(+) T-myeloid cell networks in melanoma. Sci Immunol. 2024;9(92):eadg7995. 10.1126/sciimmunol.adg7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng H, Wang M, Zhang S, Hu D, Yang Q, Chen M, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Dai J, Liou YC. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis reveals NUSAP1 is a novel predictive biomarker for prognosis and immunotherapy response. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:4689–708. 10.7150/ijbs.80017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong Y, Chen Z, Yang F, Wei J, Huang J, Long X. Prediction of immunotherapy responsiveness in melanoma through single-cell sequencing-based characterization of the tumor immune microenvironment. Transl Oncol. 2024;43:101910. 10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X, Wang J. Regulatory t cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:116. 10.1186/s12943-020-01234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Zhou X, Xie Y, Wu J, Li T, Yu T, et al. Establishment of a seven-gene signature associated with CD8(+) T cells through the utilization of both single-cell and bulk RNA-sequencing techniques in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms241813729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Y, Dong Y, Sun Q, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Li X, et al. Integrative analysis of single-cell and bulk RNA-sequencing data revealed T cell marker genes based molecular sub-types and a prognostic signature in lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2024. 10.1038/s41598-023-50787-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng L, Qin S, Si W, Wang A, Xing B, Gao R, et al. Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Science. 2021;374:abe6474. 10.1126/science.abe6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhang C, Hou M, Liu Y. Integration of single-cell RNA sequencing and bulk RNA transcriptome sequencing reveals a heterogeneous immune landscape and pivotal cell subpopulations associated with colorectal cancer prognosis. Front Immunol. 2023. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1184167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao Y, Yu D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;221:107753. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan Q, Liu C, Liu C, Liu W, Wang X, Wang Z. Discovery and validation of a metastasis-related prognostic and diagnostic biomarker for melanoma based on single cell and gene expression datasets. Front Oncol. 2020. 10.3389/fonc.2020.585980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tirosh I, Izar B, Prakadan SM, Wadsworth MH, Treacy D, Trombetta JJ, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–96. 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veatch JR, Lee SM, Shasha C, Singhi N, Szeto JL, Moshiri AS, Kim TS, Smythe K, Kong P, Fitzgibbon M, et al. Neoantigen-specific CD4(+) T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation States and correlate with CD8(+) T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:393–e409399. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huuhtanen J, Kasanen H, Peltola K, Lönnberg T, Glumoff V, Brück O, et al. Single-cell characterization of anti-LAG-3 and anti-PD-1 combination treatment in patients with melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2023. 10.1172/jci164809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi H, Tian H, Zhu T, Liao Q, Liu C, Yuan P, et al. Single-cell sequencing depicts tumor architecture and empowers clinical decision in metastatic conjunctival melanoma. Cell Discov. 2024. 10.1038/s41421-024-00683-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durante MA, Rodriguez DA, Kurtenbach S, Kuznetsov JN, Sanchez MI, Decatur CL, Snyder H, Feun LG, Livingstone AS, Harbour JW. Single-cell analysis reveals new evolutionary complexity in uveal melanoma. Nat Commun. 2020;11:496. 10.1038/s41467-019-14256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, Getz G, Berger AJ, Ramaswamy S, Beroukhim R, Milner DA, Granter SR, Du J, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–22. 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zang L, Song Y, Tian Y, Hu N. PHACTR1 promotes the mobility of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by inducing F-actin formation. Heliyon. 2023;9:e20461. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigues-Junior DM, Tan SS, Lim SK, de Souza Viana L, Carvalho AL, Vettore AL, et al. High expression of MLANA in the plasma of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as a predictor of tumor progression. Head Neck. 2019;41:1199–205. 10.1002/hed.25510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Sun HC, Cao C, Hu JD, Qian J, Jiang T, et al. Identification and validation of a novel signature based on cell-cell communication in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by integrated analysis of single-cell transcriptome and bulk RNA-sequencing. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1136729. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1136729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng W, Zhang H, Huo Y, Zhang L, Sa L, Shan L, Wang T. The role of ST3GAL4 in glioma malignancy, macrophage infiltration, and prognostic outcomes. Heliyon. 2024;10:e29829. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Xue D, Zhu X, Geng R, Bao X, Chen X, Xia T. Low expression of PLAT in breast cancer infers poor prognosis and high immune infiltrating level. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:10213–24. 10.2147/ijgm.S341959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Chen K, Liu H, Jing C, Zhang X, Qu C, et al. PMEL as a prognostic biomarker and negatively associated with immune infiltration in skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM). J Immunother. 2021;44:214–23. 10.1097/cji.0000000000000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei J, Wang L, Zhu J, Sun A, Yu G, Chen M, et al. The hippo signaling effector WWTR1 is a metastatic biomarker of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:74. 10.1186/s12935-019-0796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma J, Balakrishnan L, Kaushik S, Kashyap MK, Editorial. Multi-Omics approaches to study signaling pathways. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:829. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi X, Dong A, Jia X, Zheng G, Wang N, Wang Y, Yang C, Lu J, Yang Y. Integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk RNA-sequencing identifies a signature based on T-cell marker genes to predict prognosis and therapeutic response in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:992990. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.992990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong J, Pan R, Gao M, Mo Y, Peng X, Liang G, Chen Z, Du J, Huang Z. Identification and validation of a T cell marker gene-based signature to predict prognosis and immunotherapy response in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13:21357. 10.1038/s41598-023-48930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng H, Li Y, Zhao Y, Jiang A. Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing identifies T cell marker genes score to predict the prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2023;13:3684. 10.1038/s41598-023-30972-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smalley I, Chen Z, Phadke M, Li J, Yu X, Wyatt C, et al. Single-cell characterization of the immune microenvironment of melanoma brain and leptomeningeal metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:4109–25. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-21-1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding Y, Xiong S, Chen X, Pan Q, Fan J, Guo J. HAPLN3 inhibits apoptosis and promotes EMT of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via ERK and Bcl-2 signal pathways. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:79–90. 10.1007/s00432-022-04421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang MY, Huang M, Wang CY, Tang XY, Wang JG, Yang YD, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals MFGE8-HAPLN3 fusion as a novel biomarker in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:682021. 10.3389/fonc.2021.682021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Lei S, Luo X, Jiang C, Li Z. The value of cuproptosis-related differential genes in guiding prognosis and immune status in patients with skin cutaneous melanoma. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1129544. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1129544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Y, Han D, Duan H, Rao Q, Qian Y, Chen Q, et al. Identification of pyroptosis-relevant signature in tumor immune microenvironment and prognosis in skin cutaneous melanoma using network analysis. Stem Cells Int. 2023;2023:3827999. 10.1155/2023/3827999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Da Duarte G, Woods J, Quigley K, Deceneux LT, Tutuka C, Witkowski C, Ostrouska T, Hudson S, Tsao C, Pasam SC. Ropporin-1 and 1B are widely expressed in human melanoma and evoke strong humoral immune responses. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13081805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang P, Chen W, Xu H, Yang J, Jiang J, Jiang Y, Xu G. Correlation of CCL8 expression with immune cell infiltration of skin cutaneous melanoma: potential as a prognostic indicator and therapeutic pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:635. 10.1186/s12935-021-02350-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berciano-Guerrero MA, Lavado-Valenzuela R, Moya A, delaCruz-Merino L, Toscano F, Valdivia J, et al. Genes involved in immune reinduction may constitute biomarkers of response for metastatic melanoma patients treated with targeted therapy. Biomedicines. 2022. 10.3390/biomedicines10020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erturk K, Tas F, Serilmez M, Bilgin E, Yasasever V. Clinical signifıcance of serum Ykl-40 (chitinase-3-like-1 protein) as a biomarker in melanoma: an analysis of 112 Turkish patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2017;18:1383–7. 10.22034/apjcp.2017.18.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Choi JM. Chitinase 3-like-1, a novel regulator of Th1/CTL responses, as a therapeutic target for increasing anti-tumor immunity. BMB Rep. 2018;51:207–8. 10.5483/bmbrep.2018.51.5.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang S, Lu J, Zhou X, Wang Y, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, Cormier JN, Wargo J, Sui D, Amos CI, et al. Functional annotation of melanoma risk loci identifies novel susceptibility genes. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:452–7. 10.1093/carcin/bgz173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rayner JE, Duffy DL, Smit DJ, Jagirdar K, Lee KJ, De’Ambrosis B, Smithers BM, McMeniman EK, McInerney-Leo AM, Schaider H, et al. Germline and somatic albinism variants in amelanotic/hypomelanotic melanoma: increased carriage of TYR and OCA2 variants. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0238529. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li L, Shen FR, Cheng Q, Sun J, Li H, Sun HT, et al. Slc5a3 is important for cervical cancer cell growth. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2787–802. 10.7150/ijbs.84570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui Z, Mu C, Wu Z, Pan S, Cheng Z, Zhang ZQ, et al. The sodium/myo-inositol co-transporter SLC5A3 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell growth. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:569. 10.1038/s41419-022-05017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H, Song Y, Deng C, Xu Y, Xu H, Zhu X, Song G, Tang Q, Lu J, Wang J. Comprehensive analysis of immune infiltration and gene expression for predicting survival in patients with sarcomas. Aging. 2020;13:2168–83. 10.18632/aging.202229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang W, Yu H, Lei Q, Pu C, Guo Y, Lin L. Identification and clinical validation of diverse cell-death patterns-associated prognostic features among low-grade gliomas. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11874. 10.1038/s41598-024-62869-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M, Zhao Y, Zhao J, Huang T, Wu Y. Impact of AKAP6 polymorphisms on glioma susceptibility and prognosis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:296. 10.1186/s12883-019-1504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Earp M, Tyrer JP, Winham SJ, Lin HY, Chornokur G, Dennis J, et al. Variants in genes encoding small GTPases and association with epithelial ovarian cancer susceptibility. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197561. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moon DK, Bae YJ, Jeong GR, Cho CH, Hwang SC. Upregulated TTYH2 expression is critical for the invasion and migration of U2OS human osteosarcoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516:521–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bae Y, Kim A, Cho CH, Kim D, Jung HG, Kim SS, et al. TTYH1 and TTYH2 serve as LRRC8A-independent volume-regulated anion channels in cancer cells. Cells. 2019. 10.3390/cells8060562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu T, Zhang S, Chen J, Jiang K, Zhang Q, Guo K, Liu Y. The transcriptional profiling of glycogenes associated with hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107941. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

In this study, all datasets were obtained from publicly available databases. We utilized The Cancer Genome Atlas Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (TCGA-SKCM) dataset and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets (GSE200218, GSE215121, and GSE65904). The TCGA-SKCM dataset was downloaded from the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). GEO datasets are publicly available and can be accessed through the GEO repository by searching the respective accession numbers. The download links are provided below. Additional details are also provided in the main text. GSE200218: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200218). GSE215121: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE215121). GSE65904: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE65904). TCGA-SKCM: (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-SKCM).