Abstract

Introduction

Oral nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) are widely used in managing hepatitis B virus-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure (HBV-ACLF). Among first-line therapies, entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) are commonly prescribed. However, their comparative efficacy and safety remain unclear in HBV-ACLF.

Methods

We performed a systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science up to January 2025 for studies evaluating ETV, TDF, and TAF in HBV-ACLF. The data were analyzed using standardized mean differences (SMD), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA).

Results

Nine studies (five prospective, four retrospective) were included. TDF significantly improved 12-week survival compared to ETV (SMD = − 0.21; 95% CI − 0.36 to − 0.06), with no significant difference between TDF and TAF. For 12-week HBV-DNA clearance, TAF outperformed ETV (SMD = − 0.40; 95% CI − 0.77 to − 0.02), ranking highest in SUCRA (83.5%). TAF also showed superior virological suppression at 4 weeks (SUCRA: TAF 72.2% > ETV 49.1% > TDF 28.8%). TDF improved 12-week model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores more than ETV (SMD = 1.05; 95% CI 0.15–1.94). The drugs did not differ significantly in improving liver function at 4 weeks, as measured by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (TBIL) levels. Regarding renal function, ETV had a greater impact on the 4-week estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) than TAF (SMD = − 0.35; 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.18), and both TDF and ETV showed a more significant effect on the 4-week creatinine (cr) levels than TAF (TDF: SMD = 0.29; 95% CI 0.00–0.57; ETV: SMD = 0.30; 95% CI 0.09–0.51).

Conclusions

Overall, TDF and TAF provide superior survival and antiviral benefits over ETV in HBV-ACLF, with three drugs showing similar effects in improving liver function. Moreover, TAF demonstrated the most favorable profile in viral suppression and renal safety.

Keywords: Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Entecavir, Hepatitis B virus, Tenofovir alafenamide, Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Hepatitis B virus-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure (HBV-ACLF) has high short-term mortality, and optimizing antiviral therapy is critical to improving outcomes. |

| Although entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) are all recommended treatments, their comparative efficacy and safety in HBV-ACLF remain unclear. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This study compared the efficacy and safety of TAF, TDF, and ETV in HBV-ACLF patients using a network meta-analysis of nine cohort studies. TAF and TDF showed superior efficacy to ETV in improving survival and virological response; TAF had the highest probability of HBV-DNA clearance and the best renal safety profile. |

| All included studies were conducted in Asia–Pacific populations, where HBV-ACLF is most prevalent. While enhancing the relevance to high-burden regions, this may limit the generalizability of findings to other populations—a point discussed in the manuscript. These findings support the use of TAF as a potentially optimal treatment choice in HBV-ACLF, though more high-quality randomized controlled trials are warranted. |

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major global public health challenge. As one of the most prevalent infectious diseases, HBV has infected approximately one-third of the global population [1]. It is estimated that nearly 300 million people worldwide are living with chronic HBV infection, and more than one million deaths occur annually due to HBV-related diseases [2, 3]. In Asia, HBV infection is the leading cause of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), accounting for over 60% of cases, with mortality rates ranging from 50 to 90% [4]. Therefore, effective management and treatment of HBV-related ACLF is of significant clinical importance.

HBV-related ACLF is a clinical syndrome characterized by the rapid onset of widespread hepatocyte necrosis, severe jaundice, and coagulopathy in individuals with chronic HBV infection. It is often associated with severe complications such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. The pathogenesis is highly complex, and the short-term mortality rate is high [5]. Currently, liver transplantation is considered the most effective treatment for HBV-ACLF. However, limitations such as the scarcity of donor organs, high costs, postoperative complications, and immune rejection restrict its widespread clinical application [6, 7]. Meanwhile, several new alternative therapies, such as stem cell therapy and bioartificial liver devices, have shown promising therapeutic potential in preclinical and early clinical studies. However, their safety, efficacy, and long-term outcomes require further scientific validation [8–10]. Therefore, pharmacological treatment remains the primary approach for managing HBV-ACLF.

In the pharmacological treatment of HBV-ACLF, clinical guidelines recommend two classes of antiviral drugs: interferon-alpha and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) [11, 12]. NAs effectively inhibit HBV reverse transcriptase, reducing the viral load in the bloodstream, thereby decreasing secondary inflammation, promoting hepatocyte regeneration, and facilitating disease recovery [13, 14]. Consequently, entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) are the most commonly used first-line drugs [11, 15]. Although NAs have demonstrated good safety and tolerability, long-term use may still lead to adverse effects such as renal insufficiency and disturbances in bone calcium-phosphate metabolism [16–18]. Therefore, assessing the efficacy and safety of these drugs and selecting the most appropriate treatment regimen is crucial for the clinical management of HBV-ACLF.

Despite some inconsistencies in the available evidence, several studies have reported on the efficacy and safety of TAF, TDF, and ETV in treating HBV-ACLF. For instance, a 144-week study suggested that the efficacy and safety of these three drugs in treating HBV-ACLF were not significantly different [19]. However, many studies have only compared two of these drugs, and their conclusions have been varied. For example, a study by Li et al. [20] indicated that TAF was more effective than ETV in reducing HBV-DNA levels and ALT, as well as in improving survival rates and Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) scores. Conversely, a study by Peng et al. [21] pointed out that although TAF had superior renal safety compared to ETV, there was no significant difference in overall efficacy between the two. Furthermore, differing opinions have been reported regarding the comparison between TDF and ETV. Hossain et al. [22] suggested that TDF outperformed ETV in terms of efficacy, while Zhang et al. [23] found no significant differences between the two regarding efficacy and safety.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) can integrate data from multiple studies, providing a larger sample size and offering direct and indirect comparisons to draw overall conclusions, thus enabling a more accurate assessment of the efficacy and safety of drugs. Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and safety of TAF, TDF, and ETV in treating HBV-ACLF through the NMA.

Methods

Study Registration

The protocol has been registered with PROSPERO under protocol number CRD42025635787.

Search Strategy

Two authors (JL and YB) independently conducted a systematic search in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science, with a search period from the inception of each database up to January 2025. The search terms included all possible spellings of keywords such as “hepatitis B virus” “acute-on-chronic liver failure” “TAF” “TDF”, and “ETV”. The two authors first screened the articles based on their titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review to perform the final selection according to the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), retrospective or prospective cohort studies that provided complete baseline and outcome data; (2) Studies where participants met the ACLF diagnostic criteria defined by the Asia–Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL); (3) Participants aged between 18 and 65 years; (4) At least two treatment groups were included, with each group receiving either TAF, TDF, or ETV; (5) The study reported at least one efficacy-related outcome (e.g., survival rate; HBV-DNA levels; HBV-DNA clearance rate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TBIL, total bilirubin; MELD score, model for end-stage liver disease score) and one safety-related outcome (e.g., eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; cr, creatinine), with complete baseline and outcome data reported.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies that used only a single drug treatment with a placebo control group; (2) Studies involving combination therapies (e.g. interferon combined with nucleos(t)ide analogues, multiple nucleos(t)ide analogues combinations); (3) Duplicated publications or studies with missing data; (4) Chronic liver failure due to other causes, such as drug-induced liver injury, autoimmune liver diseases, alcoholic liver disease, genetic metabolic disorders, malignancies, or severe hematologic abnormalities.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study selection and data extraction were independently performed by two researchers (JL and YB). Any disagreements were resolved by consulting a third senior researcher (YX) for a final decision. All retrieved articles were imported into EndNote X9 software to remove duplicates. The two reviewers first screened titles and abstracts based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and eligible studies proceeded to the full-text review phase. All included studies underwent independent data extraction by the two reviewers. Data were extracted using a structured standard form, capturing the following information from eligible studies: general study characteristics (first author, study country, publication year), participant characteristics (sample size, participant age), follow-up duration, and primary and secondary outcome measures post-treatment (primary outcomes: 12-week survival rate; secondary outcomes: 4-week HBV-DNA levels, 12-week HBV-DNA clearance rate, 12-week MELD score, 4-week ALT levels, 4-week TBIL levels, 4-week eGFR, and 4-week serum creatinine). For studies where data were not directly provided, we used GetData Graph Digitizer (version 2.24) to extract data from graphs or contacted the corresponding authors via email to obtain the complete data. The entire screening process and data extraction were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (JL and YB) using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). The quality score was categorized as follows: 1–3 points indicating low quality, 4–6 points indicating moderate quality, and 7–9 points indicating high quality.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 18.0). To visually display the efficacy and safety differences between the drugs, an evidence network was constructed to represent the geometric shape of the network. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. If I2 ≤ 50%, no significant heterogeneity was assumed, and a fixed-effect model was applied for meta-analysis; if I2 > 50%, the sources of heterogeneity were further explored, and after excluding significant clinical heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used. The global and local inconsistency was assessed using loop-specific methods and node-splitting approaches [24]. For binary outcomes, risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as the measure of effect; for continuous outcomes, standardized mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs were used. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The cumulative probability ranking curve under the surface (SUCRA) value was calculated to rank the efficacy of different drugs, with a higher SUCRA value (ranging from 0 to 100%) indicating better therapeutic effect [25]. A funnel plot was used to assess potential publication bias.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Study Selection

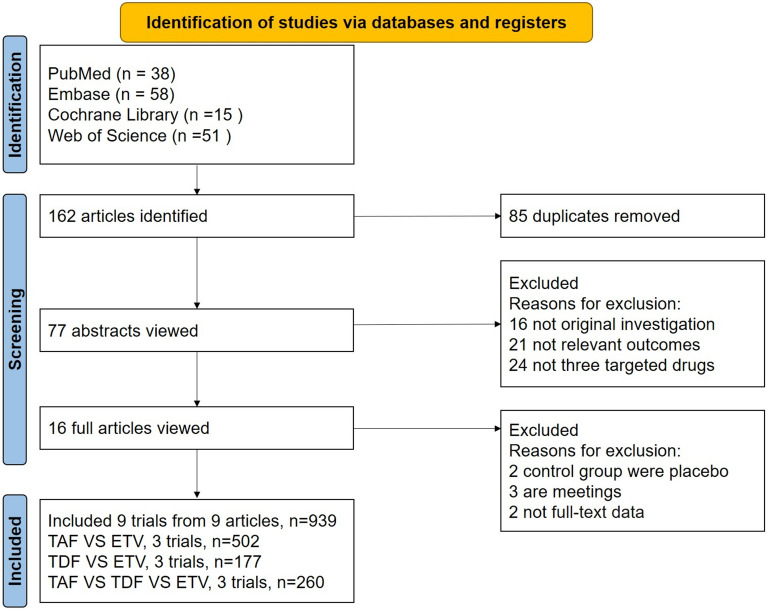

After the initial screening, a total of 162 articles were identified, of which 85 were duplicates. Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, nine studies were ultimately included in the analysis, involving 939 adult patients with HBV-ACLF treated with TAF, TDF, or ETV. The flowchart of the study selection and inclusion process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study identification, screening, and inclusion processes. ETV entecavir, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Study Characteristics

The nine studies [19–23, 26–29] included in the analysis comprised five prospective cohort studies and four retrospective cohort studies. Three of these studies compared all three drugs, while the remaining six compared any two of the three drugs. All included studies were conducted with patients from Asia, specifically China and Bangladesh. As a result, the findings may reflect a limited ethnic population. Nonetheless, these studies provide valuable clinical evidence for assessing the efficacy and safety of different nucleotide analogs in treating HBV-ACLF. The key characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the intervention groups in any of the studies. Notably, patient ages across treatment arms were generally similar and none of the studies reported significant age-related imbalance. Therefore, we believe that age was unlikely to be a confounding factor in the observed outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Studies | Year | Study design | Country | Intervention (TAF) (25 mg/day) | Intervention (TDF) (300 mg/day) | Intervention (ETV) (0.5 mg/day) | Follow-up time (weeks) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Age, mean (SD) | Sample size | Age, mean (SD) | Sample size | Age, mean (SD) | |||||

| Wan et al. | 2019 | Prospective cohort | China | 32 | 43.54 ± 11.13 | 35 | 50.72 ± 10.70 | 48 | ||

| Zhang et al. | 2020 | Retrospective cohort | China | 39 | 44.33 ± 15.87 | 39 | 45.97 ± 14.10 | 24 | ||

| Hossain et al. | 2021 | Prospective cohort | Bangladesh | 16 | 43.8 ± 13.1 | 16 | 44.2 ± 12.3 | 12 | ||

| Li et al. | 2021 | Prospective cohort | China | 10 | 40.56 ± 11.18 | 10 | 41.00 ± 12.64 | 20 | 39.72 ± 9.13 | 48 |

| Zhang et al. | 2021 | Prospective cohort | China | 23 | 42.83 ± 9.97 | 23 | 38.87 ± 7.95 | 42 | 43.90 ± 9.91 | 48 |

| Peng et al. | 2022 | Retrospective cohort | China | 80 | 45.50 ± 12.60 | 116 | 48.00 ± 12.70 | 12 | ||

| Peng et al. | 2023 | Retrospective cohort | China | 100 | 45.22 ± 12.13 | 100 | 48.11 ± 12.85 | 48 | ||

| Li et al. | 2024 | Retrospective cohort | China | 40 | 52.35 ± 6.58 | 66 | 53.70 ± 6.28 | 24 | ||

| Zhang et al. | 2024 | Prospective cohort | China | 44 | 44.56 ± 15.33 | 44 | 38.22 ± 9.04 | 44 | 39.78 ± 11.65 | 144 |

ETV entecavir, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, TAF tenofovir alafenamide, SD standard deviation

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two independent researchers assessed the quality of the included studies using the NOS. According to the quality analysis, the risk of bias for all included studies was considered acceptable. The specific results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality evaluation of the included cohort studies via the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)

| Studies | Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis controlled for confounders | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control for age and sex | Control for other confounding factors | |||||||||

| Wan et al. 2019 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

| Zhang et al. 2020 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

| Hossain et al. 2021 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 7 | ||

| Li et al. 2021 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

| Zhang et al. 2021 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

| Peng et al. 2022 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 7 | ||

| Peng et al. 2023 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

| Li et al. 2024 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 7 | ||

| Zhang et al. 2024 | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | ⁎ | 8 | |

Each asterisk (*) represents one point awarded for meeting the criteria in selection, comparability, and outcome/exposure domains. A maximum of 9 stars indicates the highest methodological quality

Network Meta-Analysis Results

Heterogeneity and Consistency

In the overall consistency analysis, the results indicated that, with the exception of the MELD score, there was good consistency across studies for the other outcome measures. Specifically, there was no significant heterogeneity for the following outcomes: 12-week survival rate (P = 0.313), 12-week HBV-DNA clearance rate (P = 0.845), 4-week HBV-DNA levels (P = 0.971), 4-week ALT levels (P = 0.272), 4-week TBIL levels (P = 0.315), 4-week eGFR levels (P = 0.429), and 4-week cr levels (P = 0.515). In contrast, the 12-week MELD score showed a P-value of 0.019, indicating some inconsistency for this specific outcome. In the local inconsistency check, no significant differences (P > 0.05) were found between the direct or indirect comparisons of studies for survival rate, HBV-DNA clearance rate, HBV-DNA levels, ALT levels, TBIL levels, eGFR levels, and cr levels, indicating that there was no local inconsistency between studies for these outcomes. However, in the MELD score analysis, no local inconsistency was observed between TDF and ETV comparisons, but significant inconsistency was noted between TAF and TDF (P = 0.002) as well as TAF and ETV (P = 0.01).

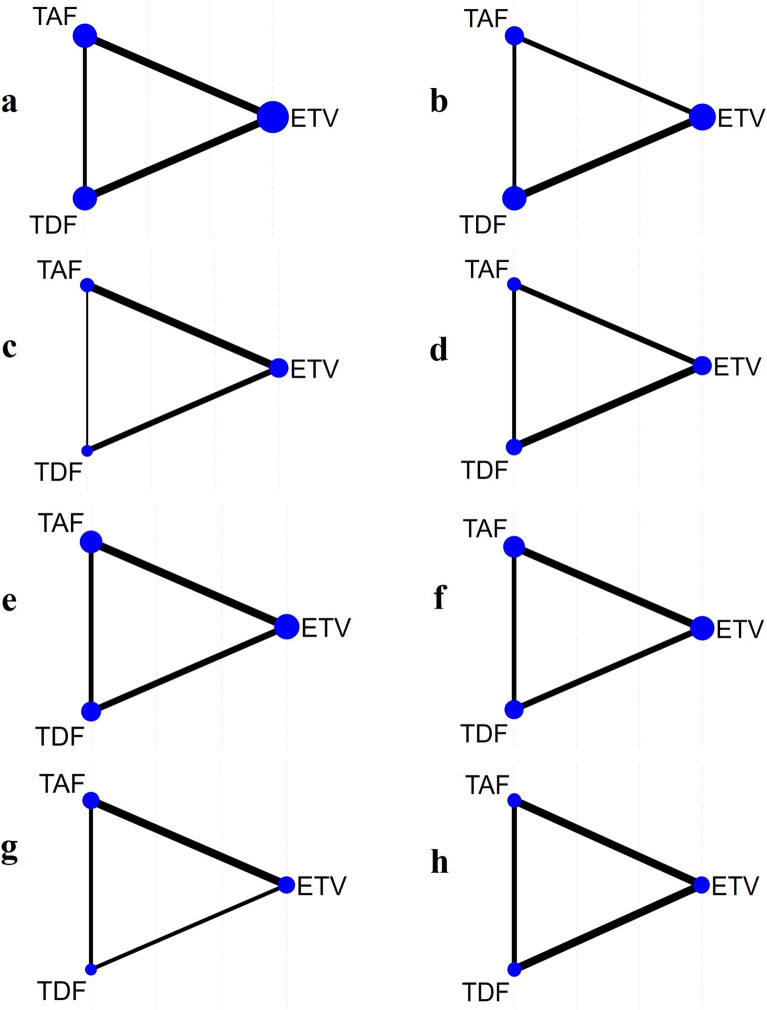

Network Structure and Geometry

In this network meta-analysis, we assessed multiple outcome measures following drug treatment, including survival rate, HBV-DNA levels, HBV-DNA clearance rate, MELD score, ALT, TBIL, eGFR, and cr levels. Figure 2 displays the network geometry of the studies, with TAF, TDF, and ETV represented as nodes. The lines connecting the nodes represent the comparisons between the drugs. The size of the blue nodes is proportional to the number of patients who received that specific drug treatment, and the width of the black lines reflects the number of studies used to compare the two drugs.

Fig. 2.

Geometry for the network meta-analysis. Figure parts a–h represent studies of a survival rate, b hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid clearance rate (HBV-DNA clearance rate), c hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid level (HBV-DNA level), d model for end-stage liver disease score (MELD score), e alanine aminotransferase (ALT), f total bilirubin (TBIL), g estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and h creatinine (cr). ETV entecavir, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Efficacy and Safety Outcomes

Survival Rate

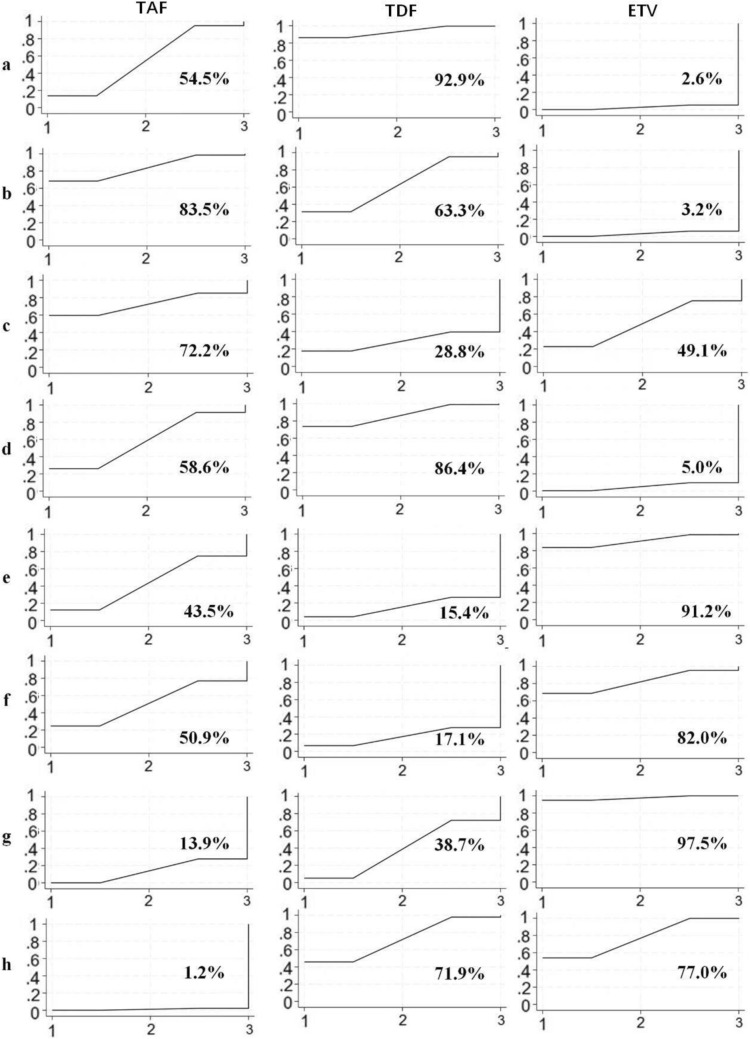

Based on the forest plot (Fig. 3a), no significant difference was found between ETV and TAF (SMD = 0.10; 95% CI − 0.09 to 0.29) or between TDF and TAF (SMD = − 0.11; 95% CI − 0.23 to 0.02). However, TDF was significantly superior to ETV, with a statistically significant difference (SMD = − 0.21; 95% CI − 0.36 to − 0.06). Consistently, the SUCRA (Fig. 4a) rankings further supported these findings, showing TDF (SUCRA 92.9%) ranked highest, followed by TAF (SUCRA 54.5%) and ETV (SUCRA 2.6%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of pairwise comparisons between two drugs. Figure parts a–h represent studies of a survival rate, b hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid clearance rate (HBV-DNA clearance rate), c hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid level (HBV-DNA level), d model for end-stage liver disease score (MELD score), e alanine aminotransferase (ALT), f total bilirubin (TBIL), g estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and h creatinine (cr). ETV entecavir, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Fig. 4.

Surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) analysis for the efficacy of tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and entecavir (ETV) across multiple outcome measures. Figure parts a–h represent studies of a survival rate, b hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid clearance rate (HBV-DNA clearance rate), c hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid level (HBV-DNA level), d model for end-stage liver disease score (MELD score), e alanine aminotransferase (ALT), f total bilirubin (TBIL), g estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and h creatinine (cr)

HBV-DNA Clearance Rate

Regarding HBV-DNA clearance rate, the forest plot (Fig. 3b) showed no significant difference between TDF and TAF (SMD = − 0.11; 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.31) or between ETV and TDF (SMD = − 0.29; 95% CI − 0.64 to 0.06), while ETV was significantly less effective than TAF, with a notable difference (SMD = − 0.40; 95% CI − 0.77 to − 0.02). The SUCRA analysis (Fig. 4b) showed that TAF was the most effective in clearing HBV-DNA (SUCRA 83.5%), followed by TDF (SUCRA 63.3%), and ETV was the least effective (SUCRA 3.2%).

HBV-DNA Levels

In terms of lowering HBV-DNA levels, no significant statistical differences were observed in pairwise comparisons between the three drugs (Fig. 3c). However, the SUCRA analysis (Fig. 4c) indicated that TAF was more effective than both ETV and TDF in reducing HBV-DNA levels, with the following ranking: TAF (SUCRA 72.2%) > ETV (SUCRA 49.1%) > TDF (SUCRA 28.8%).

MELD Score

For the MELD score, no significant difference was observed between ETV and TAF (SMD = 0.67; 95% CI − 0.31 to 1.65) or between TDF and TAF (SMD = − 0.38; 95% CI − 1.48 to 0.73). However, TDF was significantly superior to ETV, with a statistically significant difference (SMD = 1.05; 95% CI 0.15 to 1.94), as shown in Fig. 3d. Correspondingly, the SUCRA values suggested a higher probability of MELD score improvement with TDF (SUCRA 86.4%) than with ETV (SUCRA 5.0%) (Fig. 4d).

Liver Function Improvement

We extracted ALT and TBIL as indicators for liver function improvement. The forest plots (Fig. 3e and f) showed no statistically significant differences in pairwise comparisons between the three drugs for both markers. However, the SUCRA analysis (Fig. 4e and f) indicated that ETV performed the best in improving liver function, followed by TAF, and TDF showed the lowest probability of liver function improvement.

Renal Function Side Effects

To assess the side effects related to renal function decline, we extracted eGFR and cr as indicators. According to the SUCRA analysis (Fig. 4g and h), TAF had the lowest probability of eGFR decline and serum creatinine increase, while ETV had the highest probability of eGFR decline and cr increase. The analysis of eGFR (Fig. 3g) showed that ETV had a significantly greater impact on eGFR compared to TAF (SMD = − 0.35; 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.18), while no significant differences were observed between TDF and TAF or between ETV and TDF for eGFR (SMD = − 0.10; 95% CI − 0.40 to 0.21 and SMD = − 0.26; 95% CI − 0.56 to 0.04, respectively). Regarding serum creatinine (Fig. 3h), both TDF and ETV had a greater impact on cr increase compared to TAF (SMD = 0.29; 95% CI 0.00–0.57 for TDF; SMD = 0.30; 95% CI 0.09–0.51 for ETV), while no significant difference was observed between ETV and TDF regarding cr increase. In summary, TAF had the least renal side effects, indicating higher renal safety, while ETV had the most significant negative impact on renal function.

Publication Bias

The funnel plots for the efficacy and safety of the three drugs across different outcome measures are shown in Fig. 5. The funnel plots for survival rate, HBV-DNA clearance rate, MELD score, TBIL, and eGFR exhibited symmetry, indicating a well-distributed inclusion of studies. In contrast, the funnel plots for HBV-DNA levels, ALT, and cr displayed asymmetry, suggesting a higher likelihood of publication bias in the studies related to these outcome measures.

Fig. 5.

Funnel plots for efficacy and safety of three drugs across various outcome measures. A represents tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), B represents tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and C represents entecavir (ETV). HBV-DNA clearance rate hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid clearance rate, HBV-DNA level hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid level, MELD score model for end-stage liver disease score, ALT alanine aminotransferase, TBIL total bilirubin, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, cr creatinine

Discussion

HBV-ACLF is characterized by the occurrence of varying degrees of hepatocellular necrosis in patients with underlying chronic liver disease, with a high short-term mortality rate [30]. In Asia, most cases of ACLF are caused by reactivation of hepatitis B combined with underlying chronic liver disease. The primary pathogenic mechanism involves active HBV replication, triggering an excessive immune response that leads to massive hepatocyte necrosis or apoptosis within a short period [11]. Therefore, early antiviral therapy to rapidly reduce HBV-DNA load is considered crucial for treatment, and antiviral drugs should prioritize Nas that are both fast and potent, such as ETV, TDF, and TAF. This study represents the first NMA on HBV-ACLF, aiming to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TAF, TDF, and ETV in treating HBV-ACLF.

Nine studies were included in this NMA, involving 939 patients, with consistent and relatively homogeneous outcome data. Overall, the findings of this study suggest that both TAF and TDF demonstrate superior efficacy compared to ETV in improving survival, reducing and clearing HBV-DNA, and enhancing MELD scores in patients with HBV-ACLF. These findings underscore the importance of selecting the appropriate antiviral therapy for HBV-ACLF patients, particularly in the context of achieving a balance between efficacy and safety. The results also highlight the need for careful monitoring of renal function, especially in patients treated with ETV.

To date, research on the efficacy of TAF, TDF, and ETV in treating HBV-ACLF remains relatively limited. Zhang et al. [27], Li et al. [28], and Zhang et al. [19] consistently found that the three drugs showed similar efficacy in improving survival rates, suppressing and clearing HBV-DNA, and improving liver function. Our NMA results align with these previous findings, suggesting that these three drugs have comparable effects on liver function improvement. On the other hand, the study by Wan et al. [29] indicated that TDF rapidly suppressed the virus, improved liver function, and increased 48-week survival rates, outperforming ETV in treating HBV-ACLF within 2 weeks. Similarly, Hossain et al. [22] also found TDF to be more effective than ETV in improving survival rates. Conversely, Zhang et al. [23] and Wang et al. [31] argued that TDF and ETV showed similar treatment responses and clinical outcomes. Our meta-analysis supports the conclusion of Wan et al., showing that TDF outperforms ETV in improving survival rates and MELD scores in the early stages of treatment. In comparing the efficacy of TAF and ETV, Li et al. [20] and Peng et al. [26] found that TAF was superior to ETV in improving survival rates, virological response, and liver function in the early stages of treatment for HBV-ACLF patients. However, they noted that the differences between the two drugs were not significant in long-term treatment. On the other hand, Peng et al. [21] concluded that the efficacy of both drugs was comparable. Our findings also support the conclusion that TAF is superior to ETV in early antiviral treatment, aligning with the results of Li et al. and Peng et al. Overall, despite some ongoing debate regarding direct comparisons between TAF, TDF, and ETV in HBV-ACLF treatment, both existing studies and our analysis suggest that TAF and TDF are highly effective in improving liver function and survival rates, with TAF being superior to ETV in early antiviral treatment. These findings provide valuable insights for clinicians in selecting appropriate antiviral treatment options.

Renal insufficiency is a common and severe complication of HBV-ACLF [32], and the nephrotoxicity of treatment drugs is an important consideration in clinical decision-making. Many studies have shown that NAs can induce renal toxicity. These drugs are transported into proximal renal tubular cells, which are rich in mitochondria, via transporters on the basolateral membrane. The active uptake of NAs can lead to dose-dependent accumulation in the cells, causing sustained tubular damage and a subsequent decline in eGFR [33, 34]. Research has suggested that TAF has higher plasma stability than TDF, primarily because both are prodrugs of tenofovir (TFV). Similar to TDF, TAF is metabolized in the body to the active form, TFV-DP, and TFV is further metabolized within cells to tenofovir diphosphate. Studies have found that higher plasma concentrations of TFV are associated with more significant renal tubular damage. Compared to TDF, TAF has better absorption and is primarily excreted via feces, with less than 1% eliminated through the kidneys. Due to TAF’s higher bioavailability, when administered at 25 mg or lower doses, it can reduce systemic TFV exposure by over 90%, thus significantly decreasing renal toxicity [35–37].

In our study, TAF had a smaller impact on serum creatinine levels compared to ETV and TDF, and its effect on eGFR was also significantly lower than that of ETV, indicating better renal safety. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which suggest that TAF has advantages in protecting renal function [27, 38, 39]. Conversely, ETV exhibited the most significant adverse effect on kidney function, which aligns with other research findings [27, 39]. However, some studies suggest that TDF may have higher nephrotoxicity compared to ETV [6, 16]. Therefore, further investigation is needed to explore the specific mechanisms and clinical significance of the differences in renal toxicity between various NAs.

Limitations

This network meta-analysis has several limitations. First, only nine studies were included, all of which were either prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and there is a lack of support from RCTs. Second, all the studies included in this network meta-analysis were conducted in the Asia–Pacific region. Given the notable differences in the definitions and etiologies of ACLF between Eastern and Western populations (e.g., HBV predominance in Asia vs. alcohol/metabolic liver diseases in the West), the generalizability of the findings to non-Asian populations may be limited. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to broader contexts. Additionally, some data were extracted from figures in the articles, which could introduce potential inaccuracies. Finally, although our analysis focused on the treatment effects at 4 and 12 weeks, we did not perform a detailed comparison of the outcomes at different time points. As a result, a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of the efficacy and safety of these drugs across different treatment durations is still needed.

Conclusions

Through a network meta-analysis of studies evaluating the efficacy of three different nucleotide analogues in treating HBV-ACLF, this study concludes that both TAF and TDF showed superior efficacy in improving survival rates and virological response compared to ETV. All three agents had similar effects in enhancing liver function. Moreover, TAF exhibited the least adverse impact on renal function, thus demonstrating the highest renal safety among the treatments. However, the studies included in this analysis have certain limitations, particularly regarding sample size and study design. Therefore, future multicenter, large-scale clinical studies, especially randomized controlled trials, are needed to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination therapies, ultimately improving the quality of life for patients with HBV-ACLF.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, USA) for language editing and grammar refinement during manuscript preparation.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Acquisition and analysis of data: Jia Liu, Xuefeng Ma, and Yanzhen Bi. The drafting and writing of the manuscript: Jia Liu. The revision of the manuscript: Yongning Xin and Yanzhen Bi. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee were funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82202416), the China Hepatitis Prevention and Control Foundation Mu Xin Chronic Hepatitis B Research Fund (MX202409), the Beijing iGandan Foundation Clinical Research Project (iGandanF-1082024-LG002), the Qingdao Medical and Health Research Guidance Project (2023-WJZD173), the Qingdao Key Medical and Health Discipline Project.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jia Liu, Yanzhen Bi, Xuefeng Ma and Yongning Xin declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jia Liu and Yanzhen Bi contributed equally to this work and are considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Hsu YC, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(8):524–37. 10.1038/s41575-023-00760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization; 2024.

- 3.Burki T. WHO’s 2024 global hepatitis report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(6):e362–3. 10.1016/s1473-3099(24)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanam A, Kottilil S. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: pathophysiological mechanisms and management. Front Med Lausanne. 2021;8: 752875. 10.3389/fmed.2021.752875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu T, Li J, Shao L, et al. Development of diagnostic criteria and a prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut. 2018;67(12):2181–91. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li F, Wang T, Tang F, Liang J. Fatal acute-on-chronic liver failure following camrelizumab for hepatocellular carcinoma with HBsAg seroclearance: a case report and literature review. Front Med. 2023;10:1231597. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1231597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Abbas N, Rajoriya N, Elsharkawy AM, Chauhan A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in 2022: have novel treatment paradigms already arrived? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;16(7):639–52. 10.1080/17474124.2022.2097070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui K, Liu CH, Teng X, et al. Association between artificial liver support system and prognosis in hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Infect Drug Resist. 2025;18:113–26. 10.2147/idr.S500291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butt MF, Jalan R. Review article: Emerging and current management of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;58(8):774–94. 10.1111/apt.17659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikokiraki C, Psaraki A, Roubelakis MG. The potential clinical use of stem/progenitor cells and organoids in liver diseases. Cells. 2022. 10.3390/cells11091410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarin SK, Choudhury A, Sharma MK, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol Int. 2019;13(4):353–90. 10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar K, Jindal A, Gupta E, et al. Long-term HBsAg responses to Peg-interferon alpha-2b in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients developing clinical relapse after stopping long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2024;14(1): 101272. 10.1016/j.jceh.2023.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho AS, Chang J, Lee SD, et al. Nucleos(t)ide analogues potentially activate T lymphocytes through inducing interferon expression in hepatic cells and patients with chronic hepatitis B. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25286. 10.1038/s41598-024-76270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):461–91. 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu Z, Zhao Z, Ma X, Liu S, Xin Y. Renal and bone side effects of long-term use of entecavir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate in patients with hepatitis B: a network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):384. 10.1186/s12876-023-03027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong S, Shin HP, Kim HI. Real-world single-center comparison of the safety and efficacy of entecavir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and tenofovir alafenamide in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Intervirology. 2022;65(2):94–103. 10.1159/000519440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen MH, Wong G, Gane E, Kao JH, Dusheiko G. Hepatitis B virus: advances in prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020. 10.1128/cmr.00046-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Xu W, Deng Z, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tenofovir alafenamide, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and entecavir in treating hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: a 144-week data analysis. Liver Res. 2024;8(4):295–303. 10.1016/j.livres.2024.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Zhu R, Dong J, Gao Y, Yan J. Short-term efficacy of tenofovir alafenamide in acute-on-chronic liver failure: a single-center experience. Clin Pathol (Thousand Oaks, Ventura County, Calif). 2024;17:2632010x241265858. 10.1177/2632010x241265858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Peng W, Gu H, Jiang C, Liu J, Zhang J, Fu L. Comparison of tenofovir alafenamide and entecavir for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Zhong nan da xue xue bao Yi xue ban = J Cent South Univ Med Sci. 2022;47(2):194–201. 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2022.210578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hossain SMS, Mahtab MA, Das DC, et al. Comparative role of tenofovir versus entecavir for treating patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(7):2642–5. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2299_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang K, Lin S, Wang M, Huang J, Zhu Y. The risk of acute kidney injury in hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure with tenofovir treatment. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020:5728359. 10.1155/2020/5728359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shim S, Yoon BH, Shin IS, Bae JM. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using Stata. Epidemiol Health. 2017;39: e2017047. 10.4178/epih.e2017047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Resolve conflicting rankings of outcomes in network meta-analysis: partial ordering of treatments. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(4):526–36. 10.1002/jrsm.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng W, Gu H, Cheng D, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus entecavir for treating hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: real-world study. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1185492. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1185492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Xu W, Zhu X, et al. The 48-week safety and therapeutic effects of tenofovir alafenamide in HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: a prospective cohort study. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28(4):592–600. 10.1111/jvh.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Hu C, Chen Y, et al. Short-term and long-term safety and efficacy of tenofovir alafenamide, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and entecavir treatment of acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with hepatitis B. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):567. 10.1186/s12879-021-06237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wan YM, Li YH, Xu ZY, et al. Tenofovir versus entecavir for the treatment of acute-on-chronic liver failure due to reactivation of chronic hepatitis B with genotypes B and C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53(4):e171–7. 10.1097/mcg.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association; Severe Liver Disease and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure (2024 version). Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2025;33(1):18–33. 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20241206-00614. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang N, He S, Zheng Y, Wang L. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus entecavir in the treatment of acute-on-chronic liver failure with hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):388. 10.1186/s12876-023-03024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Yuan W, Zhang YY, Zhang ZG, Zou Y, Lu HZ, Qian ZP. Risk factors and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353(5):452–8. 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buti M, Riveiro-Barciela M, Esteban R. Long-term safety and efficacy of nucleo(t)side analogue therapy in hepatitis B. Liver Int: Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2018;38(Suppl 1):84–9. 10.1111/liv.13641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fung J, Seto WK, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Extrahepatic effects of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in chronic hepatitis B treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(3):428–34. 10.1111/jgh.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueaphongsukkit T, Gatechompol S, Avihingsanon A, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity: a case report and literature review. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):53. 10.1186/s12981-021-00380-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdul Basit S, Dawood A, Ryan J, Gish R. Tenofovir alafenamide for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(7):707–16. 10.1080/17512433.2017.1323633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Clercq E. Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) as the successor of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;119:1–7. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwal K, Brunetto M, Seto WK, et al. 96 weeks treatment of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):672–81. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buti M, Gane E, Seto WK, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(3):196–206. 10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.