Abstract

Γδ T cells are non-conventional T cells that are not MHC restricted and have T cell receptors (TCRs) that are stimulated by phosphoantigens, stress-induced proteins, lipids, and other antigens. These cells are prognostic across cancer types in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) but have not been well studied in endometrial cancer, which has a rising incidence and mortality rate. Endometrial cancer patients have variable responses to checkpoint inhibitors which are related to the molecular subtype of their cancer. As such, there is a pressing need to understand the immune microenvironment in endometrial cancer. This study addresses this gap in knowledge by investigating γδ T cell repertoires and transcriptomes in this disease site. γδ T cell repertoires were obtained for 543 endometrial cancer patients within the TCGA and from 5 endometrial cancer patients in the single cell dataset SRP349751 using TRUST4. GLIPH2 was used to identify TCRs predicted to bind the same antigen. Transcriptomes were investigated in the single cell dataset. DNA Polymerase Epsilon Exonuclease (POLE) and Microsatellite Instability High (MSI-H) endometrial cancer subtypes had the most γδ T cell infiltration. Vδ1 and Vδ3 γδ T cell infiltration was prognostic independent of stage and molecular subtype. GLIPH2 analysis revealed TCRδ motifs for TDK, YTD, and GEL were public across all four molecular subtypes and were present in the single cell data set. Vδ1 γδ T cell transcriptomes were associated with cytotoxicity and recent TCR stimulation. These data support further investigation of immunotherapies targeting γδ T cells in endometrial cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-025-04177-y.

Key Words: Endometrial Cancer, Immunology, Immune Microenvironment, Lymphocyte, Non Conventional T cells

Introduction

Γδ T cells are non-conventional T cells that react to antigens independent of MHC complexes. These cells are one of the strongest predictors of improved prognosis across all cancer types within The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [1, 2]. γδ T cell receptors (TCRs) recognize a diverse array of antigens including phosphoantigens, lipids, butyrophilins, stress-induced antigens such as MHC class I chain-related protein A, and nucleic acids [3]. However, many antigens for γδ TCRs remain undefined [3]. These cells are often categorized based on the variable chain gene utilized by the δ portion of their TCR with Vδ1 and Vδ3 subtypes being associated with tissue residence and adaptive antigen responses; while the Vδ2 subtype is associated with being primarily in circulation and restricted to recognizing phosphoantigens [4–6]. Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets are actively being investigated for adoptive cellular therapies in cancer [7]. However, the characteristics and repertoires of γδ T cells have not been explored in endometrial cancer which limits the ability to develop γδ T cell immunotherapies in this disease site.

Endometrial cancer arises from the glands of the uterus [8]. It is the fourth most common cancer in women, the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women, has a rising incidence, and has rising mortality rates [9, 10]. These cancers are risk-stratified by pathologic risk factors, such as stage and histology, as well as molecular risk factors [8]. There are four main molecular risk groups: DNA Polymerase Epsilon Exonuclease (POLE), which has an excellent prognosis, Microsatellite Instability High (MSI-H), which has an intermediate prognosis, Copy Number Low (CN-L), which has an intermediate prognosis, and Copy Number-High (CN-H), which has a poor prognosis [11]. The CN-H and CN-L subtypes make up over 50% of new diagnoses [8, 11]. These subgroups are predictive of response to checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 in clinical trials with MSI-H and POLE patients having the best responses, while CN-L and CN-H have minimal or no response to checkpoint inhibitors [12–16].

Studies examining the immune microenvironment of endometrial cancer molecular subtypes have consistently demonstrated MSI-H and POLE tumors are immune hot with increased numbers of infiltrating lymphocytes [17, 18]. On the other hand, most CN-L and CN-H mutated tumors are immune cold with few lymphocytes and increased numbers of tumor associated macrophages [17–21]. These studies have relied on identifying immune infiltration with immunohistochemistry or bulk deconvolution which fails to capture the heterogeneity of immune cell populations [17–20]. To date, there are a limited number of single cells RNAseq studies in endometrial cancer, and these have not focused on the immune microenvironment [22–25]. Therefore, there is a significant gap in knowledge in regard to understanding the immune microenvironment in endometrial cancer especially as it relates to rare cell populations, such as γδ T cells.

In the present study, we analyzed endometrial cancer γδ T cell repertoires by utilizing the algorithms TRUST4 to generate de novo assembly of complementary determining region 3 (CDR3) sequences for γδ T cells, and then applying grouping of lymphocyte interactions by paratope hotspots (GLIPH) to bulk RNAseq and single cell data [26, 27]. Additionally, we utilize the single cell RNAseq data to further define γδ T cell transcriptomes in endometrial cancer. We demonstrate differences in γδ T cell infiltration by molecular subtype, the presence of public GLIPH amino acid sequences across patients, the protective nature of Vδ1 γδ T cells, and γδ T cells transcriptomes reflect recent T cell receptor stimulation and cytotoxicity.

Results

γδ T cell repertoire and Gliph motifs in endometrial cancer

We accessed post-processed γδ T cell repertoire data including CDR3 length, VDJ utilization, total reads, and diversity estimation generated from applying TRUST4 to bulk RNAseq data from endometrial cancer patients within the TCGA (n = 543) [26, 28]. The demographic, pathologic, and molecular subtype data for these patients is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The γδ T cell repertoire data are publicly available at https://gdt.moffitt.org/ [28], and the demographic and pathologic data are available from https://www.cbioportal.org/ [29]. Of 543 patients, 69 (13%) had at least one detected δ chain, 169 (31%) had a detected γ chain (Fig. 1A). Of these, 35 (6%) patients had one or more δ and γ chains detected by TRUST4. The sparsity of δ and γ chains was expected given the rarity of γδ T cells, and the utilization of bulk RNA-seq. This has been discussed elsewhere [28, 30]. We started by analyzing TRDV gene utilization because this is often used to discriminate γδ T cell subtypes [31]. This demonstrated 68% of detected δ chains utilized TRDV1*01, followed by TRDV2*01 (14%), and then TRDV3*01 (13%) (Fig. 1B). γ chains utilized TRGV10*02 (20%), followed by TRGV2*01 (19%), TRGV09*01 (16%), TRGV8*01 (9%), TRGV3*01 (9%), and TRGV4*01 (8%) (Fig. 1C). We applied GLIPH2 to generate T cell receptor clusters for δ and γ chains, respectively. GLIPH aims to group similar TCR sequences that may bind the same antigen based on their underlying CDR3 amino acid sequences [27].

Fig. 1.

Overall Υδ T cell repertoire for patients in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). A Unique patients with one or more detected δ or Υ chains, respectively. B TCR δ chain variable gene usage. C TCR Υ chain variable gene usage. D The presence TCR δ GLIPH motifs in patients with at least one TCR δ chain. E The presence TCR Υ GLIPH motifs in patients with at least one TCR Υ chain. F Pairing between TCR δ GLIPH motifs and TRDV genes. G Pairing between TCR Υ GLIPH motifs and TRGV genes

GLIPH2 identified 29 TCRδ chain CDR3 amino acid motifs. Of these, TDK, YTD, YTDK, GEL, YWG, GEP, GTDK, and WGI showed the largest cluster sizes (Supplementary Table 2). Because certain four-letter motifs contained various three letter motifs, for example YTDK and GTDK are explained by TDK, we only present the simplified three letter motifs. All uncondensed GLIPH motifs are in Supplementary Table 2. Therefore, rather than having TDK, YTDK, and GTDK, patients having these motifs were condensed into a single group TDK. The motifs TDK, YTD, GEL, GEP, and YWG were present in 51%, 28%, 16%, 10% and 10% of patients with a detected δ chain, respectively (Fig. 1D). GLIPH2 identified 72 expanded amino acid motifs in γ chains. Of these, YYK, WDG, NYY, NYYK, WEV, GYK, HYY, HYYK, WDRP, WDP, and WDGP had the largest cluster sizes (Supplementary Table 3). Again, we condensed all GLIPH motifs to be described by their shortest unique amino acid sequence with the raw GLIPH data presented in Supplementary Table 3. Of the 169 patients with at least one γ chain sequence, YYK, WDG, NYY, WEV, and GYK were present in 45%, 24%, 19%, 11%, and 10% of patients, respectively (Fig. 1E). The majority of δ chain motifs paired with a single TRDV gene; however, certain motifs such as TDK and YTD paired with TRDV1*01, TRDV2*01, and TRDV3*01 (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, γ chain motifs tended to be much more promiscuous in their gene utilization with only 4 motifs, WEV, KKI, ELGK, and GKK, pairing exclusively with the TRGV9*01 gene (Fig. 1G). Given the highly variable prognosis and immune composition of endometrial cancer molecular subtypes, we were next interested in assessing the γδ T cell repertoire and GLIPH2 motifs in endometrial cancer molecular subtypes [11, 17, 18].

γδ T cell repertoire and motifs in endometrial cancer molecular subtypes

TCGA endometrial cancer molecular subtype information was obtained from Cbioportal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) and merged into the γδ T cell dataset from Yu et al. (https://gdt.moffitt.org/) to investigate γδ T cell repertoire and GLIPH2 motifs across endometrial cancer molecular subtypes [28, 29]. When analyzing the presence of at least one or more TCR δ or γ chains detected by TRUST4, 55% of POLE patients, 45% of Microsatellite Instability High patients (MSI-H), 32% of Copy Number Low (CN-L) patients, and 29% of Copy Number High (CN-H) patients had at least one γ or δ TCR (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). We confirmed this trend by performing gene set enrichment analysis of the bulk RNAseq data using individual of γ and δ genes in the four molecular subtypes. This analysis confirmed that the CN-H subtype had the lowest enrichment for γ and δ genes with increasing enrichment of γ and δ genes in the CN-L, MSI-H, and POLE subtypes (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Despite the differences in γδ T cell presence, there was no statistical difference in TRDV gene utilization, TRGV gene utilization, or CDR3 length in the molecular subtypes (Fig. 2B–E). When examining GLIPH2 amino acid motifs for δ and γ TCRs, three δ amino acid motifs (TDK, YTD, and GEL) (Fig. 2F) and twelve γ amino acid motifs (YYK, WDG, NYY, WEV, GYK, HYY, WDRP, DYK, GWF, RYK, WDRL, and AYK) were present in all four molecular subtypes (Fig. 2G). Because γδ T cell infiltration was most prominent in the POLE molecular subtype and γδ T cell repertoires were similar across molecular subtypes, we hypothesized that γδ T cell infiltration could be an independent prognostic marker in endometrial cancer.

Fig. 2.

Υδ T cell repertoire compared across endometrial cancer molecular subtypes: POLE, MSI-H (Microsatellite Instability High), CN-Low (Copy Number), and CN-H. A Percent of patients with a Υ or δ delta chain in each molecular subtype. B Histogram of the TCRδ CDR3 lengths by molecular subtype. C Histogram of the TCRΥ CDR3 lengths by molecular subtype. D TRDV gene utilization in individual molecular subtypes. E TRGV gene utilization in individual molecular subtypes. F Chord diagram of TRD GLIPH motifs and their association with each molecular subtype G Chord diagram of TRG GLIPH motifs and their association with each molecular subtype

γδ T cells and survival in endometrial cancer

We began by examining survival differences between patients with detected δ TCRs who had at least one detected TRDV1 or TRDV3 δ chain (n = 55) versus patients without a TRDV1 or TRDV3 δ chain (n = 488). The characteristics of these two patient populations is summarized in Table 1. Patients with a detected TRDV1, TRDV2, or TRDV3 gene were considered as having a Vδ1, Vδ2, or Vδ3 γδ T cell present as the TRDV gene utilization is often used to categorize human γδ T cells 33. We elected to focus on patients who had a Vδ1 or Vδ3 subtype present because these subtypes are associated with tissue residence and adaptive antigen responses [4–6]. This showed that patients with at least one TRDV1 or TRDV3 δ chain present had an improved prognosis (5-year progression free survival [PFS]: 82%, hazard ratio [HR]: ref) compared to those without a TRDV1 or TRDV3 δ chain (5-year PFS: 44%, HR: 0.42, 95% 0.1.05–5.41, plogrank < 0.03) (Fig. 3A). The n for patients without a detected TRDV1 or TRDV3 on survival analysis adds up to 487 because one of these patients did not have survival information. On multivariate analysis including age, grade, histology, stage, and molecular subtype, the presence Vδ1 or Vδ3 γδ T cells remained an independent predictor of improved prognosis (0.35, 95% CI 0.14–0.86, p = 0.02).

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics who did and did not have a detected TRDV1 or TRDV3 δ chain present

| Characteristic | TRDV1 or TRDV3 Present (n = 55) | TRDV1 or TRDV3 Absent(n = 488) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (SD) | 62.04 (9.82) | 64.21 (11.24) |

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid | 43 (78.2) | 364 (74.6) |

| Mixed serous and endometrioid | 1 (1.8) | 21 (4.3) |

| Serous | 11 (20.0) | 103 (21.1) |

| Grade | ||

| G1 | 9 (16.4) | 89 (18.2) |

| G2 | 9 (16.4) | 111 (22.7) |

| G3 | 37 (67.3) | 288 (59.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) |

| Stage | ||

| Stage I | 36 (65.5) | 303 (62.1) |

| Stage II | 3 (5.5) | 42 (8.6) |

| Stage III | 12 (21.8) | 110 (22.5) |

| Stage IV | 4 (7.3) | 21 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.5) |

| Subtype | ||

| UCEC_CN_HIGH | 14 (25.5) | 148 (30.3) |

| UCEC_CN_LOW | 11 (20.0) | 135 (27.7) |

| UCEC_MSI | 20 (36.4) | 128 (26.2) |

| UCEC_POLE | 8 (14.5) | 41 (8.4) |

| Unknown | 2 (3.6) | 36 (7.4) |

| TRDV gene | ||

| TRDV1 | 49 (89.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| TRDV2 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) |

| TRDV3 | 6 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown TRDV gene | 0 (0) | 7 (1.4) |

| Not detected | 0 (0.0) | 473 (97.4) |

Patients were categorized as unknown TRDV gene if TRUST4 determined a δ chain was present but did not report the TRDV gene

Fig. 3.

Survival analysis focused on patients who had a TCRδ chain detected (n = 69) and how GLIPH2 motif in combination with gene utilization impacts survival in this group of patients (A) Patients with either Vδ1 or Vδ3 Υδ T cell infiltration had better prognosis compared to those who Vδ2 chains detected (HR = 6.25, 95% CI 2.07–18.9, p < 0.001). The n for patients without a detected TRDV1 or TRDV3 on survival analysis adds up to 487 because one of these patients did not have survival information. B Presence of a TCRδ chain with the GEL amino acid motif as detected by GLIPH2 was predictive of no recurrences at 5 years. GEL was only paired with TRDV1. C Presence of a TCRδ chain with the YWG amino acid motif as predicted by GLIPH2 was predictive of no recurrences at 5 years. YWG was only paired with TRDV1. D The TDK TCRδ chain motif was not associated with improved survival, but this motif was associated with TRDV1, TRDV2, and TRDV3 utilization. E Survival in patients with TDK motif and TRDV1 utilization (F) Survival in patients with TDK motif and TRDV2 utilization. G Survival in patients with TDK motif and TRDV3 utilization

There was no interaction between There was no clear trend in TRGV gene usage and prognosis, including among TRGV genes known to preferentially pair with TRDV1 such as TRGV2*01 and TRGV4*01 (Supplementary Table 4). Based on our data indicating that δ GLIPH2 motifs tended to pair with specific TRDV genes while γ GLIPH2 motifs tended to pair with multiple TRGV genes (Fig. 1B and C), we suspected that a combination of antigen specificity approximated by GLIPH2 motif, and associated gene utilization would better elucidate patient survival.

Among the GLIPH2 TCRδ motifs, survival was heterogenous with motifs such as GEL and YWG being associated with no recurrences at 5 years, while YTD and TDK did not confer improved prognosis despite being the most prevalent across patients (Fig. 3B–E). Survival of all GLIPH2 TCRδ motifs is in Supplementary Table 5. However, when considering GLIPH2 motifs in combination with gene utilization, motifs utilizing TRDV1 or TRDV3 were associated with long term survival, while motifs, such as TDK, that were associated with TRDV1, TRDV2, and TRDV3 utilization (Fig. 1C), only conferred improved survival when detected in patients with TRDV1 or TRDV3 (Fig. 3F–H). This trend was ubiquitous across all motifs with 14 of 20 motifs utilizing TRDV1 or TRDV3 being associated with no recurrences at 5 years, whereas 7 out of 8 motifs utilizing TRDV2 had one or more recurrences at 5 years (Supplementary Fig. 2). The survival data for all GLIPH2 TCRδ motifs by TRDV gene utilization is in Supplementary Table 5. We then examined survival associated with TCRγ GLIPH2 motifs. None of the TCRγ GLIPH2 motifs was associated with improved prognosis (Supplementary Table 6). The TCRγ GLIPH2 motifs DGPG (HR 8.61, 95% CI 2.62–28.31, p < 0.001) and WDRR (HR 5.09, 95% CI 1.56–16.7, p = 0.007) were associated with worse prognosis. When examining prognostic differences in individual motifs based on TRGV gene utilization prognosis was highly variable. For example, YYK, the most prevalent GLIPH2 motif in the TCGA dataset, trended toward an improved prognosis when utilizing TRGV2*01 (HR 0.38, p = 0.18) but trended toward a worse prognosis when associated with TRGV4*02 utilization (HR 2.85, p = 0.30). All survival data for TCRγ GLIPH2 motif pairings are shown in Supplementary Table 7. Given that multiple δ and γ TCR GLIPH2 motifs were public across molecular subtypes and the prognostic impact of Vδ1/δ3 γδ T cells, we hypothesized that γδ T cell subtypes may differ between normal endometrium, atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH), the precursor to endometrioid endometrial cancer, and endometrial cancer. We further hypothesized that Vδ1 and Vδ3 γδ T cell transcriptomes may exhibit anti-cancer-related gene expression patterns such as cytotoxicity.

Endometrial cancer is associated with changes in γδ T cell subtypes

To test our hypothesis that γδ T cell subtypes differ during the stages of endometrial cancer development and that certain γδ T cells may have protective transcriptomes, we accessed the SRP349751 dataset [22] which contained single cell data from normal endometrium (n = 5), AEH (n = 5), and endometrioid endometrial cancer (n = 5) using the sratoolkit [32]. In this dataset, three of the endometrial cancer cases were classified as no specific molecular subtype which is associated with the CN-L TCGA subtype, and two were classified as dMMR, which is associated with the MSI-H subtype [22]. Cellranger version 8.0.1 was used to generate bam files which were analyzed using TRUST4 to produce the γδ T cell repertoires. The CDR3 sequences for γ and δ TCRs were input into GLIPH2 to generate amino acid motifs. Using cell barcodes, the single cell expression data, γδ T cell repertoire data from TRUST4, and TCR amino acid motifs from GLIPH2 were linked into a single dataset (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

A Experimental schema of how the Υδ T cell repertoire data from single cell data. B Boxplot of the percentage of Υδ T cells using TRDV1, TRDV2, or TRDV3. TRDV1 was exclusive to atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) and endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC). TRDV1 did appear in normal endometrium (Normal). C Boxplot of the percentage of Υδ T cells using each TRGV in Normal, AEH, and EEC. TRGV9*01 made up a significant portion of Υδ T cell TRGV utilization in EEC followed by TRGV5*01, TRGV4*02, andTRGV10*02. D Box plot of the proportion of each phenotype based on the presence of the TCRδ amino acid motifs as determined by GLIPH2.GEL and WGI only appeared in patients with EEC or AEH. While TDK was found in Normal, AEH, and EEC. E Box plot of the proportion of each phenotype based on the presence of the TCRΥ amino acid motifs as determined by GLIPH2 also showed variable presence of different motifs in Normal, AEH, and EEC

We first examined γδ T cell TRDV and TRGV utilization in normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer. TRDV gene utilization showed significant differences in normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer (pFisher’s Exact Test = 0.006). γδ T cells utilizing TRDV1*01 were only present in AEH and endometrial cancer, suggesting that TRDV1 expressing γδ T cells may be enriched in endometrial cancer. TRDV2*01 gene utilization was seen in normal, AEH, and endometrial cancer. γδ T cells utilizing TRDV3*01 gene decreased when going from normal endometrium to endometrial cancer (Fig. 4B). TRGV gene utilization analysis also showed significant differences across normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer with TRGV2*01, TRGV2*03, TRGV3*01, TRGV4*01, TRGV4*02, TRGV5*01, and TRGV8*01 being most prominent in endometrial cancer (pFisher’s Exact Test = 0.0015). TRGV9*01 had the highest utilization in atypical endometrial hyperplasia (Fig. 4C). Overall, the data from endometrial cancer cases in the single cell data set closely mirrored our findings from the TCGA which demonstrated that in endometrial cancer cases TRDV1*01 was the most prevalent TRDV gene and that TRGV9*01, TRGV2*01, and TRGV10*02 are the most utilized by TRGV genes by γδ T cells in endometrial cancer. We next explored δ and γ amino acid motifs based on GLIPH2.

GLIPH2 identified 14 individual TCRδ amino acid motifs of which 5 (TDK, GEL, WGI, and SDK) overlapped with the TCGA TCRδ GLIPH2 amino acid motifs (Supp Table 8). In accordance with our prior data from the TCGA, TDK and SDK were associated with utilization TRDV2*01 whereas GEL and WGI only utilized TRDV*01 (Supp Fig. 3). The presence of these motifs varied significantly in normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer with GEL and WGI only present in the setting of AEH or endometrial cancer, whereas TDK motifs were present in normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer (pFisher’s Exact Test = 0.004) (Fig. 4D). When evaluating TCRγ amino acid motifs, GLIPH2 identified 132 motifs of which 30 (YYK, YYY, WEV, WDG, WDV, WDW, WDF, VYK, RYK, PYK, NYY, NYK, HYK, HYY, KKI, GYK, GWF, GKK, FYY, EYK, DYK, DWI, AYK, WDRR, WDRS, WDRL, WDRP, SSDW, ELGK, and DGPG) overlapped with the TCGA TCRγ amino acid motifs (Supp Table 9). The TCRγ amino acid motifs also showed significant heterogeneity between normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer with motifs such as YYK, YYY, and WDG having an increased presence among endometrial cancer patients (pFisher’s Exact Test < 0.001) (Fig. 4E). Based on the increased presence of Vδ1 γδ T cells in endometrial cancer compared to normal endometrial tissue, the public nature of GLIPH2 motifs associated with Vδ1 γδ T cells in the TCGA and the single cell dataset, and the association of Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells with an improved prognosis in endometrial cancer patients within the TCGA, we next tested our hypothesis that the transcriptomes of Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells may exhibit anti-cancer related gene expression patterns.

Tissue resident γδ T cells show signs of antigen engagement and cytotoxic profiles

Of the 963 cells with a detected TCRγ and/or TCRδ chains only 24 were paired within the same cell. Therefore, we used known canonical TRGV and TRDV associations to classify individual γδ T cells as being Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells. This methodological assumption relied on the underlying knowledge that generally Vδ1/Vδ3 δ chains pair with γ chains utilizing TRGV2*01, TRGV2*03, TRGV3*02, TRGV4*01, TRGV4*02, TRGV5*01, and TRGV8*01 [33]. We confirmed these canonical associations were accurate in cells that had both a δ and γ chain by plotting a heatmap of TRDV vs TRGV utilization. In cells with both a TCRγ and TCRδ, Vδ1 and Vδ3 paired almost exclusively with TRGV2, TRGV3, TRGV4, TRGV5, and TRGV8. On the other hand, Vδ2 paired almost exclusively paired with TRGV9 (Supp Fig. 4). As such, we analyzed the differences in the transcriptomes between the groups termed Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells.

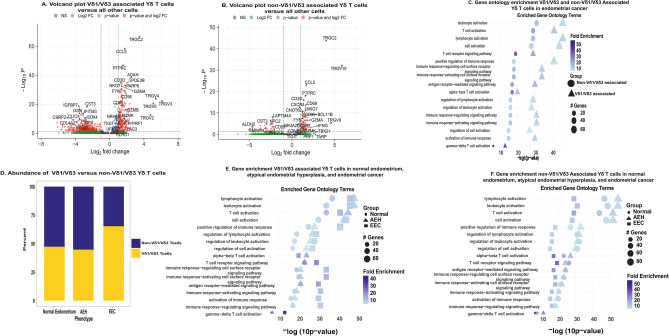

Differential gene expression (DEG) analysis in endometrial cancer demonstrated that the Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells overexpressed TRGV2, TRGV3, and TRGV4 while non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells overexpressed TRGV9 and TRGV10 consistent with our prespecified grouping (Fig. 5A and B). Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells also overexpressed genes related to recent antigen stimulation and TCR activation (CD69, FYN, NR4A2, and DUSP2). These cells had upregulation of the RNA transcripts for the checkpoint molecules CD96, LAG3, KLRC1, and TIGIT but did not have upregulation of the RNA transcripts for the checkpoints PDCD1 (PD-1) or CTLA4 (Supp Table 10). Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells were cytotoxic expressing GZMA, GZMB, GZMK, NKG7, PRF1, and IFNG (Fig. 5A). Non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells also had upregulation of genes associated with antigen stimulation including CD69, FYN, NR4A2, and DUSP2. While these cells also expressed the checkpoint molecule CD96, they did not have overexpression of TIGIT, LAG3, or KLRC1 which were overexpressed in the Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells. The non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells were also negative for PDCD1 and CTLA4 (Supp Table 11). Non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells did overexpress some cytotoxic related genes including GZMA, NKG7, and IFNG. They did not overexpress GZMB, GZMK, or PRF1 (Fig. 5B). All DEGs for Vδ1/Vδ3 and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells are in Supp Tables 10 and 11, respectively. Based on the DEGs, we performed gene ontology enrichment analysis for all significant (padjusted < 0 0.05) positive DEGs in Vδ1/Vδ3 and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells. This showed that both groups had highly significant upregulation of leukocyte activation, T cell activation, antigen-receptor mediated signaling, γδ T cell activation, and multiple other activation pathways. These pathways were more significantly upregulated in the Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells compared to the non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells (Fig. 5C). The Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells also had increased significance of activation and antigen stimulation pathways in endometrial cancer compared to normal endometrium (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Transcriptome and pathway analysis of Vδ1/Vδ3 and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated Υδ T cells. A Volcano plot of under and over expressed genes in Vδ1/Vδ3-associated Υδ T cells. Consistent with their known phenotype they overexpressed TRGC2, TRGV2, TRGV3, TRGV4, and TRGV5. These cells overexpressed multiple genes associated it cytotoxicity including GZMA, GZMB, and PRF1. B Volcano plot of under and over expressed genes in non-Vδ1/Vδ3-associated Υδ T cells. Consistent with their phenotype they overexpressed TRGC2, TRGV9, and TRGV10. These cells lacked significant expression of certain cytotoxic genes such as PRF1 or lower had lower expression of certain cytotoxic genes such as GZMB. C Stacked bar plot of the proportion of all Υδ T cells which were either Vδ1/Vδ3 or non-Vδ1/Vδ3 Υδ T cells in normal endometrium, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrioid endometrial cancer. Vδ1/Vδ3 made up an increased proportion of Υδ T cells in endometrial cancer. D Gene ontology enrichment of Vδ1/Vδ3 and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated Υδ T cells consistently demonstrated increased significance of activated pathways in the Vδ1/Vδ3 associated Υδ T cells. E Gene ontology enrichment analysis in Vδ1/Vδ3 associated Vδ1/Vδ3 Υδ T cells in normal endometrium, atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH), and endometroid endometrial cancer (EEC) showed consistent increase in their activation pathways when going from normal endometrium to EEC. F Gene ontology enrichment analysis in non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated cells in normal endometrium, AEH, and EEC showed the opposite. These cells showed an increased significance of activation in normal endometrium and lower cytotoxicity in EEC

We next investigated DEGs in Vδ1/Vδ3 associated and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells, respectively, in normal endometrium and AEH. Both groups showed multiple DEGs in normal endometrium and AEH which mirrored the findings for both γδ T cell subsets in endometrial cancer (Supp Tables 12 and 13, respectively). We used these differentially expressed genes in normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer to perform gene ontology pathway analysis in Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells and non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells in the three endometrial phenotypes. Thus, providing an understanding of how γδ T cell gene expression changes during the development of endometrial cancer. This demonstrated that Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells had increasing significance of T cell activation, T cell receptor signaling, immune response activating signaling pathway, γδ T cell activation, among others when going from normal endometrium, AEH (precancer), and then endometrial cancer (Fig. 5E). On the other hand, non-Vδ1/Vδ3 associated γδ T cells in cancer had decreasing significance of T cell activation, T cell receptor signaling, immune response activating signaling pathway, and γδ T cell activation when going from normal endometrium to endometrial cancer (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

While γδ T cells are one of the strongest predictors of improved prognosis across all TCGA cancer types, they have not been characterized in endometrial cancer [1, 2]. The present study sheds light on the importance of this cell type in endometrial cancer through demonstrating there is variation in γδ T cell infiltration across molecular subtypes, identifying there are multiple public δ and γ chain GLIPH motifs in endometrial cancer patients across multiple datasets, finding an association between increased infiltration of Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells and improved prognosis independent of underlying molecular subtype or stage, and discovering Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells in endometrial cancer have cytotoxic transcriptomes consistent with recent activation. Furthermore, Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells made up a larger proportion of γδ T cells in endometrial cancer and had up regulation of pathways related to recent activation and antigen stimulation. Additionally, we identified multiple immune checkpoints overexpressed in the Vδ1/Vδ3 subtype that maybe targeted in future translational studies. Overall, these results demonstrate γδ T cells are an important part of the endometrial cancer immune microenvironment that maybe exploited as an innovative target in this disease site [34–37].

Our study corroborates Yu et al. work [28] that overall, there was low γδ T infiltration in endometrial cancer with less than 50% of patients having a single δ or γ chain. This detection was variable across molecular subtypes with over 50% of POLE patients, who have the best prognosis, having at least 1 δ or γ chain detected while the CN-H subtype, with the worst prognosis, only 29% of patients had a detected δ or γ chain. This data is supported by analyses of bulk RNAseq data from the TCGA with CIBERSORT which indicated there were differences in γδ T cell infiltration across endometrial cancer molecular subtypes [18]. An unexpected finding from our study was that the majority of detected γ chains utilized TRGV10. TRGV10 is a pseudogene in humans that produces a non-functional TCRγ. Yu et al. and others have also observed TRGV10 to be increased in various cancer types [28, 38, 39]. Therefore, we included it in all our analysis. The reason for increased TRGV10 in our study and others is unclear but γδ T cell rearrangement is altered in the thymus with age and may be contributing to this phenomena which deserves future investigation [33, 40].

Survival analyses demonstrated significantly improved progression-free survival independent of molecular subtype or stage in patients with infiltration of Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells. However, in the TCGA dataset, only 13% of patients had a detected δ chain which makes it difficult to interpret the generalizability of their prognostic value in a larger population. Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells have been associated with improved prognosis in ovarian, renal, non-small cell lung, and triple negative breast carcinomas [34–37]. Furthermore, in a prior endometrial cancer study, bulk tumor TRDV1 gene expression was associated with improved survival [25]. This suggests, even in “immune cold” molecular subtypes, γδ T cells may retain functional relevance. This is further supported by our data demonstrating γδ T cell repertoires were remarkably similar across molecular subtypes, and that several GLIPH2 amino acid motifs were public to all molecular subtypes. This suggests potential shared antigen recognition in γδ T cells and should be investigated in future studies.

In the single cell dataset of normal endometrium, AEH, and endometrial cancer, we found multiple GLIPH2 TCRδ and TCRγ motifs which were also present in TCGA endometrial cancer patients. The TDK, GEL, and WGI GLIPH2 TCRδ motifs detected in our study have also been detected in colon cancer patients [41]. This further supports that certain γδ T cell TCRs may recognize antigens that are associated with cancer. In line with this finding, Vδ1 and Vδ3 γδ T cell subtypes had increasing cytotoxicity, T cell stimulation, and overall activation when comparing between normal endometrium, precancer of the endometrium, and endometrial cancer. While there were few γδ T cells in the single cell data set, their transcriptomes were similar to previous reports in other cancers [25, 35]. This included the expression of cytotoxic markers and genes such as CRTAM, AOAH, and CCL5 which are important in cancer recognition, lipid metabolism, and immune cell recruitment [25, 35]. However, the non-Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cell subtypes showed decreased cytotoxicity in our study. This could have been because the non-Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cell group included γδ T cells that had TCRγ chains which were produced by TRGV10 and thus non-functional. This further highlights the need for understanding selective pressures on γδ T cell rearrangement as well as the need to confirm our findings via enriching for γδ T cells. Interestingly, The Vδ1 and Vδ3 γδ T cells in our study also overexpressed RNA transcripts associated with the immune checkpoints for CD96, LAG3, and TIGIT. All three of these checkpoints are actively being investigated in clinical trials [42–44]. As such, these could be explored in translational studies testing blockade of these checkpoints in γδ T cells.

Our study has several limitations. First, utilizing T cell receptor deconvolution algorithms, such as TRUST4 and MIXCR, with bulk RNAseq data is known to have decreased detection of both γδ and αβ T cells [26, 30, 45]. As such, our data likely underrepresent the diversity and number of γδ T cells in endometrial cancer. Additionally, these computational methods may be biased to under-detect certain γ and δ chains. As such, this means that patients who had a detected Vδ1 γδ T cells based on the presence of a TRDV1 utilizing δ chain may have also had had a Vδ2 γδ T cell also present but the lack of sequencing depth made this cell undetectable. This highlights the need for further studies enriching for γδ T cell populations in endometrial cancer to better define their contribution to endometrial cancer biology and prognosis across endometrial cancer molecular subtypes. Despite this limitation, our findings were supported from a biological perspective by prior studies performing γδ T cell repertoire profiling in cancer [28, 35, 41]. Second, the identified GLIPH2 motifs require functional validation to prove that they indeed react to an endometrial cancer related antigen [27]. Third, the single cell set dataset was not enriched for γδ T cells and had only five patients with normal endometrium, five with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and five with endometrial cancer [22]. This meant we had to rely on canonical variable gene associations of γ and δ chains which do not always hold true. Additionally, we were unable to study the difference in γδ T cell transcriptomes in endometrial cancer molecular subtypes. Lastly, we only used gene expression data to infer functional states. Future work will focus on including protein level data in combination with multiplex immunofluorescence assays for γδ T cell subtypes and function. It is well known that gene expression does not always correlate with protein expression or function [46]. As such, this data needs confirmation at the protein level.

In summary, our findings identify Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells as prognostic markers in endometrial cancer and that these cells have cytotoxic profiles. Furthermore, the importance of these cells was demonstrated in two independent data sets. Interestingly, these γδ T cells overexpress genes for several checkpoint inhibitors which are actively being investigated in clinical trials representing a potential translational opportunity. Future directions include validating the presented findings through flow cytometry, single cell analysis, and T cell receptor profiling enriched for γδ T cells.

Methods

Ethics statement

This dataset used anonymized, publicly available data and was exempt from IRB review. This study conducted all research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Belmont Report.

Study population and data acquisition

All data in this study were derived from two datasets: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), located at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ [11] and SRP349751 (NCBI Sequencing Read Archive (SRA) database archive number: SRP349751) [22]. All data from the TCGA and SRP349751 were accessed and downloaded in compliance with data use policies. Endometrial cancer patients were in the TCGA were downloaded from the UCEC subset (n = 543). Demographic, pathologic, and molecular subtype data for the TCGA patients was obtained from downloaded from Cbioportal at https://www.cbioportal.org/ [29]. This information is summarized in Supp Table 1. Survival data for TCGA patients were obtained from Liu et al.’s publication: “An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics” [47]. The γδ T cell repertoire for endometrial cancer patients was downloaded from Yu et al. work at https://gdt.moffitt.org/ [28]. Using the sample ID for each specimen the data were integrated into a single dataset for analysis. The raw fastq files for dataset SRP349751 were downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra] using the sratoolkit [22, 32]. Sample phenotype annotations for SRP349751 were obtained directly from Ren et al. publication [22]. The two cohorts were analyzed independently without randomization or blinding.

γδ T cell repertoire analysis

In the TCGA, we analyzed CDR3 length, V-gene usage, and applied GLIPH2 to decipher local motifs for CDR3 sequences δ and γ chains, respectively. We employed GLIPH2 via the TurboGliph R package and following the associated vignette [27]. The δ and γ chain input files included the associated CDR3 sequence, V, and J gene as specified by GLIPH2 (http://50.255.35.37:8080/). Parameters included min_seq_length = 2, local_method = fisher, boost_local_significance = TRUE, global_method = fisher, clustering_mehtod = GLIPH2.0, scoring_method = GLIPH2.0, and n_cores = 4. HLA data were not included because γδ T cells are not MHC restricted. Our utilization of GLIPH was based on prior work which described GLIPH for γδ TCR analysis {Stary, 2024 #55}. The repertoire data for SRP349751 dataset was generated using TRUST4 [26]. Patients with a detected TRDV1, TRDV2, or TRDV3 gene were considered as having a Vδ1, Vδ2, or Vδ3 γδ T cell present as the TRDV gene utilization is often used to categorize human γδ T cells {Wu, 2017 #87}{Gray, 2024 #5}. We did not include clonal expansion data secondary to the low count numbers in the TCGA and SRP349751 datasets. These data were visualized using a combination of ggplot2, chord diagrams via the circlize package (RRID:SCR_002141), and heatmaps via the ComplexHeatmap package (RRID:SCR_017270) [48–50]. Version numbers are included in the Supplementary Document: Supp_R_environment.

SRP349751 single cell dataset analysis

The raw fastq files for dataset SRP349751 were downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra] using the sratoolkit [32]. The raw fastq files were analyzed using cellranger v8.0.1 to generate the associated bam files. The cellranger outputs were inspected for quality control using the associated “web summary” file for each file. All samples passed quality control. The bam files were then analyzed using TRUST4 [26]. The output from TRUST4 was combined into a singular file which was filtered to contain only cells exclusively expressing γ and/or δ chains. The TRUST4 outputs were analyzed using the same pipeline described in the γδ T Cell Repertoire Analysis section of the methods. Transcriptomic data was analyzed using the Seurat package (RRID:SCR_016341) [51] using our already established bioinformatics pipelines [52–54]. In brief, after inspecting the “web summaries” for quality control, the associated “flitered_feature_bc_matrix” RNA expression files for each patient were combined into a single Seurat object. We started with a total of 143,193 cells. Mitochondrial gene expression, RNA count, and RNA feature data were visually inspected to determine cut offs to remove low quality cells. Cells were removed if they had mitochondrial gene expression greater than 10%, greater than 10,000 RNA features (genes), or more than 125,000 RNA molecules (nCount_RNA). Cells were removed if they had RNA features (genes) less than 500 or less than 1000 RNA molecules. Doublets were removed using the Doublet Finder package in R [55]. After initial cell filtering and removing doublets, there were a total of 104,864 cells. Batch effects were removed between patients using the IntegrateLayers function in Seurat [51]. This resulted in the final Seurat object for γδ T cell transcriptomic analysis.

Once completed, the cell barcodes of the γδ T cells identified from TRUST4, were used to annotate which cells in the Seurat object would be considered γδ T cells. This resulted in a total of 963 cells being classified as γδ T cells. Only 24 cells had paired γδ chains. Therefore, we classified γδ T cells as being Vδ1/Vδ3 or non-Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cells based on canonical TRDV and TRGV associations [33]. This was based on assuming canonical associations of Vδ1/Vδ3 γδ T cell δ chains with γ chains utilizing TRGV2*01, TRGV2*03, TRGV3*02, TRGV4*01, TRGV4*02, TRGV5*01, and TRGV8*01 [33]. We confirmed that this assumption was accurate in cells that had both a δ and γ chain (Supp Fig. 4). Differential gene expression was calculated using MAST in the Seurat package in R, with an average log fold change threshold of 0.1, a minimum percent threshold of 0.1, and no minimum threshold of cells comparing between the Vδ1/Vδ3 or non-Vδ1/Vδ3 groups vs all other cells, respectively. The same technique was used to compare differential gene expression in the respective Vδ1/Vδ3 or non-Vδ1/Vδ3 groups between endometrial cancer and normal endometrium, endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and then normal endometrium and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Significance was based on a Bonferroni adjusted p value of 0.05 [51]. This portion of the analysis was completed in a Linux computing environment using the High-Performance Computing Cluster at Augusta University.

TCGA gene set enrichment analysis

Delta and gamma gene enrichment was calculated by using TCGAbiolinks [56] to download the gene expression data for the endometrial cancer patients in the TCGA. We then modeled gene expression as a function of tumor purity to obtain the residual values of gene expression which would approximate how non-tumor tissue contributed to gene expression. We obtained the tumor purity estimates for individual TCGA patient samples from Aran et al. [57]. Gene set enrichment was conducted using the GSVA package in R [58] using TRDV, TRDD, and TRDJ genes to estimate delta gene enrichment. For gamma gene enrichment, we used TRGV and TRGJ genes, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.1 [59]. Detailed info on all packages, including version numbers, are included in the Supplementary R environment file (Supp_R_environment). Categorical data was analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test as indicated based on sample size. All continuous data was analyzed with non-parametric tests. Survival data was analyzed using Kaplan Mier curves and cox proportional hazards via the survival and survminer packages in R. Significance of survival data was determined using log rank p values for univariate analysis. For multivariate cox proportional hazards analysis, p values were based on the likelihood-ratio test. A priori power analyses were not performed as this work was exploratory.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Augusta University High Performance Computing Services (AUHPCS) for providing computational resources contributing to the results presented in this publication/report.

Author contributions

DM—wrote manuscript, data analysis, figure preparation, idea conception, project administration, writing code AS—concept development, manuscript editing, project administration, NJ—concpet development, data analysis AA—data analysis, statistical analysis, writing code BO—manuscript editing, concept development RM—project administration MJ—manuscript editing, project administration RH—manuscript editing, project administration BR—concept development, manuscript editing, project administration SG—project administration CH—concept development, manuscript editing, project administration KL—concept development, manuscript editing, project administration, data analysis All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript are currently publicly available. The TCGA γδ T cell repertoire data are available at https://gdt.moffitt.org/. The single cell transcriptome data are available from SRP349751: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRP349751.

Code availability

All code to analyze the data was developed from existing R packages. Code is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morath A, Schamel WW (2020) αβ and γδ T cell receptors: similar but different. J Leukoc Biol 107(6):1045–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gentles AJ et al (2015) The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med 21(8):938–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deseke M, Prinz I (2020) Ligand recognition by the γδ TCR and discrimination between homeostasis and stress conditions. Cell Mol Immunol 17(9):914–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey MS et al (2017) Clonal selection in the human Vδ1 T cell repertoire indicates γδ TCR-dependent adaptive immune surveillance. Nat Commun 8(1):14760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitard V et al (2008) Long-term expansion of effector/memory Vδ2− γδ T cells is a specific blood signature of CMV infection. Blood 112(4):1317–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravens S et al (2017) Human γδ T cells are quickly reconstituted after stem-cell transplantation and show adaptive clonal expansion in response to viral infection. Nat Immunol 18(4):393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jhita N, Raikar SS (2022) Allogeneic gamma delta T cells as adoptive cellular therapy for hematologic malignancies. Explor Immunol 2(3):334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu KH, Broaddus RR (2020) Endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med 383(21):2053–2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel RL et al (2025) Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 75(1):10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullins MA, Cote ML (2019) Beyond obesity: the rising incidence and mortality rates of uterine corpus cancer. J Clin Oncol 37(22):1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine DA (2013) Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 497(7447):67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makker V et al (2022) Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for advanced endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med 386(5):437–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirza MR et al (2023) Dostarlimab for primary advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med 388(23):2145–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eskander RN et al (2023) Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med 388(23):2159–2170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garmezy B et al (2022) Clinical and molecular characterization of POLE mutations as predictive biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced cancers. JCO Precis Oncol 6:e2100267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Gorp T et al (2024) ENGOT-en11/GOG-3053/KEYNOTE-B21: a randomised, double-blind, phase III study of pembrolizumab or placebo plus adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed, high-risk endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol 35(11):968–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talhouk A et al (2019) Molecular subtype not immune response drives outcomes in endometrial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 25(8):2537–2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dessources K et al (2023) Impact of immune infiltration signatures on prognosis in endometrial carcinoma is dependent on the underlying molecular subtype. Gynecol Oncol 171:15–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howitt BE et al (2015) Association of polymerase e–mutated and microsatellite-instable endometrial cancers with neoantigen load, number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and expression of PD-1 and PD-L1. JAMA Oncol 1(9):1319–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning-Geist BL et al (2022) Microsatellite instability–high endometrial cancers with MLH1 promoter hypermethylation have distinct molecular and clinical profiles. Clin Cancer Res 28(19):4302–4311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly MG et al (2015) Type 2 endometrial cancer is associated with a high density of tumor-associated macrophages in the stromal compartment. Reprod Sci 22(8):948–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren X et al (2022) Single-cell transcriptomic analysis highlights origin and pathological process of human endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Nat Commun 13(1):6300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren F et al (2024) Single-cell transcriptome profiles the heterogeneity of tumor cells and microenvironments for different pathological endometrial cancer and identifies specific sensitive drugs. Cell Death Dis 15(8):571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regner MJ et al (2021) A multi-omic single-cell landscape of human gynecologic malignancies. Mol Cell 81(23):4924-4941.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harmon C et al (2023) γδ T cell dichotomy with opposing cytotoxic and wound healing functions in human solid tumors. Nat Cancer 4(8):1122–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song L et al (2021) TRUST4: immune repertoire reconstruction from bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Methods 18(6):627–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H et al (2020) Analyzing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis immune response by T-cell receptor clustering with GLIPH2 and genome-wide antigen screening. Nat Biotechnol 38(10):1194–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu X et al (2024) Pan-cancer γδ TCR analysis uncovers clonotype diversity and prognostic potential. Cell Rep Med. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerami E et al (2012) The cbio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2(5):401–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menda Dabran L, Zilberberg A, Efroni S (2025) RNA-seq based T cell repertoire extraction compared with TCR-seq. Oxf Open Immunol 6(1):iqaf001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y et al (2023) γδ T cells: origin and fate, subsets, diseases and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8(1):434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leinonen R, Sugawara H, Shumway M, I.N.S.D. Collaboration (2010) The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res 39(suppl_1):D19–D21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray JI et al (2024) Human γδ T cells in diverse tissues exhibit site-specific maturation dynamics across the life span. Sci Immunol 9(96):eadn3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foord E et al (2021) Characterization of ascites-and tumor-infiltrating γδ T cells reveals distinct repertoires and a beneficial role in ovarian cancer. Sci Transl Med 13(577):eabb0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rancan C et al (2023) Exhausted intratumoral Vδ2− γδ T cells in human kidney cancer retain effector function. Nat Immunol 24(4):612–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y et al (2022) A local human Vδ1 T cell population is associated with survival in nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Nat Cancer 3(6):696–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y et al (2019) An innate-like Vδ1+ γδ T cell compartment in the human breast is associated with remission in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 11(513):eaax9364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etherington MS et al (2024) Tyrosine kinase inhibition activates intratumoral Γδ T cells in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Immunol Res 12(1):107–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frieling JS et al (2023) γδ-Enriched CAR-T cell therapy for bone metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Adv 9(18):eadf0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong N, Raulet DH (2007) Development and selection of γδ T cells. Immunol Rev 215(1):15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stary V et al (2024) Dysfunctional tumor-infiltrating Vδ1+ T lymphocytes in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 15(1):6949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamid O, Baxter D, Easton R, Siu L (2021) 488 phase 1 trial of first-in-class anti-CD96 monoclonal antibody inhibitor, GSK6097608, monotherapy and combination with anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody, dostarlimab, in advanced solid tumors. BMJ Specialist Journals, London [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chocarro L et al (2022) Clinical landscape of LAG-3-targeted therapy. Immuno-Oncol Technol 14:100079 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chavanton A et al (2024) LAG-3: recent developments in combinational therapies in cancer. Cancer Sci 115(8):2494–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng K et al (2023) Rigorous benchmarking of T-cell receptor repertoire profiling methods for cancer RNA sequencing. Brief Bioinform 24(4):bbad220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R (2016) On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 165(3):535–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J et al (2018) An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell 173(2):400-416.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ (2019) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Taylor & Francis, New York [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu Z et al (2014) " Circlize" implements and enhances circular visualization in R

- 50.Gu Z (2022) Complex heatmap visualization. Imeta 1(3):e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hao Y et al (2024) Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat Biotechnol 42(2):293–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iqneibi S et al (2023) Single cell transcriptomics reveals recent CD8T cell receptor signaling in patients with coronary artery disease. Front Immunol 14:1239148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khan A et al (2024) Bimodal single cell RNA sequencing reveals changes in CD4+ T cell transcriptomes with age. J Immunol 212(1_Supplement):0600_4979-0600_4979 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vallejo J et al (2022) Combined protein and transcript single-cell RNA sequencing in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BMC Biol 20(1):193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGinnis CS, Murrow LM, Gartner ZJ (2019) DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst 8(4):329-337.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colaprico A et al (2016) TCGAbiolinks: an R/bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res 44(8):e71–e71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aran D, Sirota M, Butte AJ (2015) Systematic pan-cancer analysis of tumour purity. Nat Commun 6(1):8971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J (2013) GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform 14:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 59.R Core Team, R. (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this manuscript are currently publicly available. The TCGA γδ T cell repertoire data are available at https://gdt.moffitt.org/. The single cell transcriptome data are available from SRP349751: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRP349751.

All code to analyze the data was developed from existing R packages. Code is available upon request from the corresponding author.