Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy has revolutionized the treatment of hematological malignancies but faces significant challenges in solid tumor therapy. The tumor microenvironment (TME) of solid tumors, including the dense extracellular matrix (ECM) and immunosuppressive factors, creates physical and biochemical barriers that hinder CAR-T cell infiltration, function, and persistence. Despite advances in CAR-T cell engineering, overcoming these TME barriers remains a major obstacle. The ECM in solid tumors restricts CAR-T cell penetration and limits their antitumor efficacy. Recent studies have explored ECM modulation as a strategy to enhance CAR-T therapy. Nattokinase (NKase), a natural fibrinolytic enzyme, has shown potential in degrading ECM components, promoting TME remodeling, and improving therapeutic responses. In this study, we evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of NKase in combination with MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells for solid tumors. We hypothesize that NKase will reduce tumor fibrosis by degrading ECM components, facilitating CAR-T cell infiltration and enhancing their cytotoxic activity. In vitro and in vivo experiments will assess the effects of NKase on CAR-T cell infiltration, activation, memory phenotype maintenance, and antitumor activity. This study aims to optimize CAR-T therapy for solid tumors and supports the clinical potential of NKase as an adjunctive therapeutic agent.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-025-04167-0.

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy, Solid tumors, Tumor microenvironment (TME), Extracellular matrix (ECM), Nattokinase (NKase), Mesothelin (MSLN), Tumor fibrosis, Immune infiltration, Antitumor activity, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy has revolutionized the treatment of hematological malignancies [1–3], demonstrating remarkable success in the clinical setting [4, 5]. However, its application in the treatment of solid tumors remains a significant challenge [6–8]. The efficacy of CAR-T cells in solid tumors is limited by various factors [8, 9], including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) [10, 11], inadequate infiltration of CAR-T cells into tumor tissue, and the mechanisms of immune escape employed by tumors [12]. Solid tumors are characterized by a dense extracellular matrix (ECM) [13–15] and a hostile immunosuppressive microenvironment [16–18], both of which create physical and biochemical barriers that hinder CAR-T cell infiltration [19, 20], function, and persistence, thereby restricting therapeutic effectiveness [20, 21].

Although substantial progress has been made in improving CAR-T cell functionality, particularly in enhancing their antitumor activity [22], overcoming the barriers imposed by the TME remains a major challenge [23, 24]. The ECM in solid tumors plays a crucial role as a physical barrier [25], impeding CAR-T cell penetration into the tumor core [26, 27]. Recent studies have begun to focus on modulating the tumor ECM as a potential strategy to improve the efficacy of immunotherapies, including CAR-T therapy [28, 29].

The ECM of solid tumors is a complex network composed of various components [30, 31], mainly including structural proteins (such as collagen and elastin) [32], adhesion glycoproteins (such as fibronectin and laminin) [33], proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans (such as hyaluronic acid and versican) [34], ECM-modifying enzymes [35], and growth factors bound to the matrix [36, 37]. These components not only provide structural support for tumor cells but also regulate cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and signal transduction, promoting tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [38, 39]. At the same time, the dense and stiff nature of tumor ECM also hinders drug penetration and the entry of immune cells, thereby leading to drug resistance and immune escape [40, 41]. Nattokinase (NKase), a natural fibrinolytic enzyme derived from Bacillus subtilis during the fermentation of soybeans (a process used to make natto), has garnered attention due to its ability to degrade ECM components, promote remodeling of the TME, and enhance the overall therapeutic response [42].

In prior studies, our research team successfully developed CAR-T cells targeting mesothelin (MSLN) [43], which demonstrated promising therapeutic effects in MSLN-positive tumor models, such as ovarian cancer. Building on this success, we hypothesize that combining NKase with MSLN CAR-T cells can improve tumor cell infiltration and enhance CAR-T cell-mediated antitumor effects. Specifically, we propose that NKase, through its ability to degrade fibrin and other ECM components within the tumor microenvironment, may reduce tumor fibrosis and facilitate CAR-T cell penetration into the tumor, thereby amplifying their cytotoxic activity.

The aim of this study is to investigate the impact of NKase on the therapeutic efficacy of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells in solid tumors. Specifically, we aim to assess how NKase influences CAR-T cell infiltration, activation, exhaustion, memory phenotype maintenance, and antitumor activity. Through both in vitro and in vivo experiments, this study will explore how NKase-induced remodeling of the tumor microenvironment enhances CAR-T cell function, offering new strategies to optimize CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors.

Materials and methods

Cells and culture conditions

HEK293 (human embryonic kidney), OVCAR3 (ovarian cancer), and HCC1806 (breast squamous carcinoma) lines were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM, RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). PBMCs from healthy donors (TPCS#PB025C, Miles-bio, Shanghai) were isolated using Lymphoprep (Stemcell, Canada), and T cells were purified by negative selection with the EasySep™ human T Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell, Canada). On day 0, T cells were activated with antihuman CD3 and CD28 beads (Miltenyi, Germany) and cultured in X-VIVO medium (Ronsa, Switzerland) supplemented with recombinant IL-2 (300 IU/mL) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). CAR-T cells were infected with lentivirus, and the cell phenotype and positive rate were assessed after 48 h.

Lentivirus production

Lentivirus for CAR-T cells was produced by co-transfecting HEK293T cells (ATCC) with lentiviral and packaging plasmids (pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-Rev, pMD2.G). Supernatants were collected 48 and 72 h post-transfection, concentrated by ultracentrifugation, and stored at − 80 °C.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a Beckman Coulter machine, and data were analyzed using software CytExpert. The cells were stained at room temperature for 25 min, washed twice with PBS, and then tested on the machine. The detailed information of the antibodies is listed in Table S1.

CCK-8 cell viability assay

HCC1806, OVCAR3 tumor cell lines and MSLN CAR-T cells were, respectively, seeded at 2E4 cells per well in 96-well plates. NKase was purchased from Shaanxi Zerang Biology (Catalog No.1147; 20,000 FU/g). NKase solutions of gradient concentrations of 0, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 FU/100 μl were prepared using the corresponding culture media for HCC1806, OVCAR3 tumor cell lines, and MSLN CAR-T cells to treat the cells for 24 h. After treatment, 20 μl of CCK-8 reagent (CCK-8 kit purchased from Beyotime, Catalog No. C0038) was added to each well and incubated in the incubator for 2–3 h before detection on a microplate reader.

CAR-T cytotoxicity assay

Short-term Killing: CAR-T cells were co-cultured with luciferase-expressing OVCAR3, HCC1806 cells at E/T ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 for 8 h. After incubation, luminescence was measured, and cytotoxicity was calculated as [(background luminescence—sample luminescence)/background luminescence] × 100%.

Long-term killing: Tumor cells and CAR-T cells were co-incubated for 24 h at the specified effector-to-target ratio (1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8), and the lysis of target cells was measured. Then, new target cells were added to the effector cells at the same effector-to-target ratio, and four rounds of co-incubation and target cell lysis detection were repeated.

Real-time killing: Tumor cells were spread on a 96-well electrode plate coated with L-cysteine. After the tumor cells were fully covered, effector cells were added successively at the specified effector target ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:4). Continuously collect data.

Western blot analysis

HCC1806 cells before and after 125FU NKase treatment were homogenized in cold RIPA lysis buffer containing PMSF, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation. Protein quantification was performed using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit. Thirty micrograms of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE gel separation and transferred onto a 0.22-µm PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with blocking solution (5% skim milk in TBST: 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, followed by incubation with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1–2 h (anti-fibronectin antibody was purchased from Abcam; anti-alpha smooth muscle actin antibody was purchased from Abcam.). Finally, the membrane was developed using an ECL Western blotting detection kit. The detailed information of the antibodies is listed in Table S1

Immunofluorescence staining

HCC1806 cell lines and mouse tumor tissues before and after 125FU NKase treatment were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight, embedded in paraffin, and sliced. After deparaffinization and hydration, tissues were pretreated with sodium citrate solution for antigen retrieval. Next, the tissue sections were blocked with 5% goat serum for 30 min at room temperature and incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody for 1 h at 37 °C in the dark (anti-fibronectin antibody was purchased from Abcam, catalog number ab2413). After counterstaining with DAPI to reveal the cell nucleus, tissue sections were photographed using a Nikon 80I 10–1500 × microscope. Quantification of colocalization was analyzed by the Image J colocalization finder plugin.

3D microsphere infiltration experiment

3D tumor microsphere models were constructed using Corning® 96-well transparent round-bottomed spherical microplates for HCC1806 cells with green fluorescent protein (GFP). After each well of 2E4 tumor cells formed into spheres and were cultured for 48 h, after 48 h, add the prepared 125FU NKase solution, after 24 h, add MSLN CAR-T cells at a 1:1 effector-to-target ratio to the corresponding wells. After 24 h, immunofluorescence photography showed the killing of 3D microspheres.

Mouse tumor model

Female B-NKG mice (6 weeks, Biocytogen, Beijing) were subcutaneously implanted with 2 × 106 HCC1806 cells. On day 10, the mice were randomly assigned to three experimental groups (n = 6 per group). The experimental group received intratumoral injections of 125 FU NKase into tumor tissues. Twenty four hours later, either PBS or 1 × 106 MSLN CAR-T cells were administered via tail vein injection. The size of the tumor and the body weight of the mice was measured every two days, tumor volumes calculated as volume = (length × width2) × 0.5.

Cytokine measurement

Cell supernatant: After co-incubating HCC1806 cells with MockT, MSLN CAR-T, and NKase-added MSLN CAR-T cells at a 1:2 effector-to-target ratio for 24 h, collect the cell culture supernatant and centrifuge (1000 × g, 10 min) to remove cell debris. Plasma supernatant: Collect 200 ul of peripheral blood from each group of mice, centrifuge at 3000g for 10 min, and aspirate the supernatant for testing. The BD™ Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Mouse/Rat Soluble Protein Master Buffer Kit (Cat: 558266) is used to detect the release of cytokines. Mix the fluorescently encoded microspheres coated with specific antibodies with the test supernatant, add PE-labeled detection antibodies, incubate at room temperature in the dark for 3 h to form a "capture microsphere—cytokine—PE antibody" sandwich complex. After the antibody incubation is completed, add washing buffer for centrifugation to remove unbound antibodies, resuspend the precipitate with flow cytometry PBS. Use a flow cytometer (such as BD FACSCalibur) to analyze the fluorescence signals of the microspheres to quantitatively determine the concentrations of IL-10, TNF-a, and IFN-γ cytokines. Process and output the results through software FCAP.GUI.

Histopathological examination

On the tenth day after CAR-T cell reinfusion, one mouse in each group was randomly sacrificed to obtain tumor tissue samples. All mice were sacrificed on the 28th day after CAR-T reinfusion, and the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain tissues were collected. The tissue specimens were fixed with 4% buffer solution formaldehyde. Paraffin sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical analysis. Both the primary antibody and the secondary antibody were rabbit antihuman antibody CD3 antibody and enzyme-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L separate (Abcam). Then, the cell nucleus was stained with DAPI (Abcam). Tumor staining of mice treated with PBS was used as the control. The infiltration quantity of IHC CD3+T cells was analyzed using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.0 software and presented as SD ± . Student’s t test was used for two-group comparisons, and one-way or two-way ANOVA was used for multiple-group analysis. Statistical significance was defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Results

Effects of NKase concentration on tumor cells and MSLN CAR-T

To investigate whether NKase could enhance the antitumor efficacy of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells by modulating the tumor microenvironment, we first evaluated its potential cytotoxic effects on tumor and immune cells, as well as its impact on CAR-T functionality.

We began by confirming the successful construction and surface expression of the chimeric antigen receptor in MSLN CAR-T cells. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated robust expression of the CAR construct in transduced T cells, confirming the generation of functional MSLN CAR-T cells (Fig. 1A–B). Next, HCC1806 and OVCAR3 tumor cells, as well as MSLN CAR-T cells, were treated with a gradient of NKase concentrations ranging from 0 to 2000 FU, and cell viability was assessed. The data indicated that NKase exerted no significant effect on the viability of either HCC1806 or OVCAR3 tumor cells within the concentration range of 0 to 500 FU, nor did it influence the viability of MSLN CAR-T cells within the range of 0 to 2000 FU (Fig. 1C–E). To identify the minimum effective concentration of NKase for tumor treatment, we further examined the cytotoxic activity of MSLN CAR-T cells against HCC1806 cells after treatment with different concentrations of NKase, employing luciferase reporter assays at various effector-to-target (E/T) ratios. Notably, after 8 h of treatment with NKase concentrations ranging from 62.5 to 2000 FU, a significant increase in the lysis rate of HCC1806 cells was observed across all tested E/T ratios (Fig. 1F–H). Similarly, a significant enhancement in the lysis rate of OVCAR3 cells by MSLN CAR-T cells was noted with NKase concentrations ranging from 125 to 2000 FU at different E/T ratios (Fig. 1I–K). These findings suggest that NKase significantly enhances the antitumor activity of MSLN CAR-T cells, thereby improving their cytotoxic potential against target tumor cells. Based on these results, a concentration of 125 FU was selected as the optimal concentration for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Effects of NKase Concentration on Tumor Cells. A Schematic representation of the CAR structure in MSLN CAR-T cells. The CAR construct includes a signal peptide, anti-MSLN scFv, IgG4 hinge region, CD28 transmembrane domain, CD28 co-stimulatory domain, and CD3ζ intracellular signaling domain. B Flow cytometric analysis of CAR-positive expression in MSLN CAR-T cells. C–E Cell viability of HCC1806, OVCAR3, and MSLN CAR-T cells following treatment with NKase at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2000 FU was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. F–K Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated the cytotoxic activity of MSLN CAR-T cells against HCC1806 F–H and OVCAR3 I–K tumor cells at effector-to-target ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 after 8 h of exposure to NKase at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2000 FU. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent in vitro experiments; ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA

NKase potentiates MSLN CAR-T cell activation and antitumor response

Since NKase was always present in the environment of MSLN CAR-T during the in vitro killing experiments, therefore, to evaluate the influence of NKase on the functional state of MSLN CAR-T cells, we assessed the expression of activation, exhaustion, and apoptosis-related markers using flow cytometry. CBA was used to measure the release of cytokines. MSLN CAR-T cells were stimulated either with untreated HCC1806 tumor cells or HCC1806 cells pretreated with NKase, and changes in marker expression were analyzed before and after stimulation. Flow cytometry analysis showed that compared with MSLN CAR-T cells stimulated with HCC1806, the expression of activation markers CD25 and CD69 in MSLN CAR-T cells stimulated with HCC1806 cells treated with NKase was significantly increased (Fig. 2A, B), indicating that the presence of the NKase environment promoted T cell activation. In addition, the expression of the exhaustion markers PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 was markedly decreased in CAR-T cells in the NKase-treated condition (Fig. 2C–E), suggesting that NKase attenuates T cell exhaustion within the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, the apoptotic biomarkers Annexin V and 7-AAD were significantly downregulated in MSLN CAR-T cells following stimulation with NKase-treated tumor cells, relative to those stimulated with untreated tumors (Fig. 2F, G). CBA results showed that the cytokine release of MSLN CAR-T cells co-incubated with NKase-treated HCC1806 cells was higher, indicating an enhanced killing effect (Fig. 2H–J). These results indicate a decrease in apoptotic signaling in the presence of NKase. Taken together, these findings suggest that NKase regulates the functional phenotype of MSLN CAR-T cells by promoting activation, reducing exhaustion, and decreasing apoptosis. This modulation of CAR-T cell behavior by NKase may contribute to enhanced persistence and improved antitumor efficacy in the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 2.

NKase Potentiates MSLN CAR-T Cell Activation and Antitumor Response. A–E The expression levels of activation markers (CD25, CD69) and exhaustion markers (TIM-3, LAG-3, and PD-1) in MSLN CAR-T cells were analyzed before and after stimulation with HCC1806 tumor cells and NKase-treated HCC1806 tumor cells. F–G Flow cytometric analysis was conducted to assess the expression of early apoptosis marker (Annexin V) and late apoptosis marker (7-AAD) in MSLN CAR-T cells. H–J Following the co-incubation of HCC1806 tumor cells and NKase-treated HCC1806 tumor cells with MSLN CAR-T at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2 for 24 h, the concentrations of IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in the cell culture supernatants were quantified. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent in vitro experiments; ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01;***, p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA

NKase promotes long-term cytotoxicity and memory phenotype in MSLN CAR-T cells

To further evaluate the cytotoxic effect of MSLN CAR-T cells on tumor cells treated with NKase, we conducted real-time cell killing experiments using HCC1806 and OVCAR3 tumor cell lines. The tumor cells were first pretreated with 125 FU NKase, and then the lysis of these cells by MSLN CAR-T cells was evaluated. The lysis rate varied with the ratio of effector cells to target cells (E/T) (1:1, 1:2, 1:4) (Fig. 3A–F). In all tested E/T ratios, the lysis rate of tumor cells in the NKase pretreatment group was significantly higher than that of the untreated control group (NC group), indicating that NKase pretreatment of tumors significantly enhanced the tumor-killing ability of MSLN CAR-T cells. To investigate whether NKase would affect the differentiation state of CAR-T cells, we analyzed the expression of CD45RO and CD62L by flow cytometry to distinguish the initial/memory T cell subsets, including stem cell memory T cells (TSCM), central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), and terminal effector T cells (TTE) (Fig. 3G). Notably, NKase led to an increase in the proportion of TSCM and TCM subgroups, while the population of effector memory T cells (TEM) and terminal effector T cells (TTE) decreased. These results indicate that NKase promotes the memory-like phenotype of MSLN CAR-T cells, which may help prolong cell lifespan and maintain the persistence of antitumor function. To assess the persistence of the cytotoxicity of MSLN CAR-T cells, we conducted repeated in vitro tumor-killing experiments with different E/T ratios (1:1, 1:4, 1:8) over multiple rounds (Fig. 3H–O). Compared to the control group, MSLN CAR-T cells co-cultured with NKase-treated tumor cells exhibited superior killing ability in all stimulation rounds. These findings suggest that NKase pretreatment of tumors enhances the persistence and long-term cytotoxic function of MSLN CAR-T cells, thereby improving their potential efficacy in the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 3.

NKase Promotes Long-Term Cytotoxicity and Memory Phenotype in MSLN CAR-T Cells. A–F Real-time cytotoxicity assays revealed the lysis of HCC1806 and OVCAR3 target cells by MSLN CAR-T cells in both the negative control (NC) group and the 125 FU NKase treatment group at effector-to-target ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4. G Flow cytometric analysis was performed to assess the expression levels of CD45RO and CD62L on MSLN CAR-T cells in the NC and 125 FU NKase treatment groups. The proportions of stem cell memory T cells (TSCM), central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), and terminally differentiated effector T cells (TTE) were determined based on distinct cell populations. H–O In vitro multi-round cytotoxicity assays were carried out to evaluate the persistence of MSLN CAR-T cell cytotoxicity in the NC and 125 FU NKase treatment groups. Effector and target cells were co-incubated at defined effector-to-target ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) for four consecutive rounds (R1–R4), each lasting 24 h, with target cell lysis assessed in each round. The experiments were repeated three times, and p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA. ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001

NKase enhances the infiltration of MSLN CAR-T cells and the antitumor effect in vivo

To evaluate the impact of nattokinase (NKase) on the infiltration and antitumor activity of mesothelin-targeted CAR-T (MSLN CAR-T) cells in vivo, A total of 2 × 106 HCC1806 cells were subcutaneously injected into six-week-old female NSG mice. The animals were randomly assigned to three groups: the PBS control group, the MSLN CAR-T group, and the NKase + MSLN CAR-T group. Ten days after tumor cell implantation, the experimental group received intratumoral injection of 125 FU NKase for tumor tissue pretreatment. Twenty four hours later, each group was intravenously administered with either PBS or 1 × 106 MSLN CAR-T cells per mouse (n = 6). Thereafter, tumor size and body weight were monitored every two days, and peripheral blood samples were collected every four days for flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 4A). Like the in vitro experiments, CD69 expression was significantly upregulated in the NKase-treated group compared to controls, indicating enhanced T cell activation (Fig. 4B), while PD-1 expression was markedly reduced, suggesting alleviation of T cell exhaustion (Fig. 4C). Analysis of memory T cell subsets demonstrated a shift toward a memory phenotype, with increased proportions of TSCM and TCM and decreased frequencies of TEM and TTE in the NKase group (Fig. 4D), indicative of improved persistence potential. No significant difference in body weight was observed between groups, confirming good tolerability (Fig. 4E), whereas tumor volume and tumor size were significantly lower in the NKase-treated group (Fig. 4F–G). Immunohistochemical staining further showed increased infiltration of CD3 + T cells into tumor tissues following NKase treatment (Fig. 4H, I). The CBA results also showed that the MSLN CAR-T + NKase group had a higher level of IFN-γ release (Fig. 4J). Importantly, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of major organs revealed no pathological abnormalities or tissue damage in either group (Fig. 4K), indicating that NKase does not induce off-target toxicity. Collectively, these results demonstrate that NKase enhances the in vivo activation, infiltration, and antitumor function of MSLN CAR-T cells while maintaining a favorable safety profile.

Fig. 4.

NKase enhances the infiltration of MSLN CAR-T cells and the antitumor effect in vivo. A Schematic representation of the in vivo experimental design. B Flow cytometric analysis of CAR-T cell activation in mouse peripheral blood. C Flow cytometric analysis of CAR-T cell exhaustion in mouse peripheral blood. D Assessment of memory marker expression (CD45RO and CD62L) on CAR-T cells in mouse peripheral blood. The proportions of stem cell memory T cells (TSCM), central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), and terminally differentiated effector T cells (TTE) were determined based on distinct cell populations. E–F Graphical representation of body weight and tumor volume measurements in mice at various time points. G Tumor growth curves depicting changes in tumor size across experimental groups. H–I Immunohistochemical staining results showing infiltration of CD3 + cells in tumor tissues on day 10 post-MSLN CAR-T cell infusion. J The expression level of IFN-γ in the plasma supernatant of mice. K At the conclusion of the experiment, major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain, were harvested from mice and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining to evaluate the safety profile of MSLN CAR-T cells in nontarget tissues. The experiment was repeated three times, and p values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001

Analysis of gene expression differences in tumor cells treated with NKase

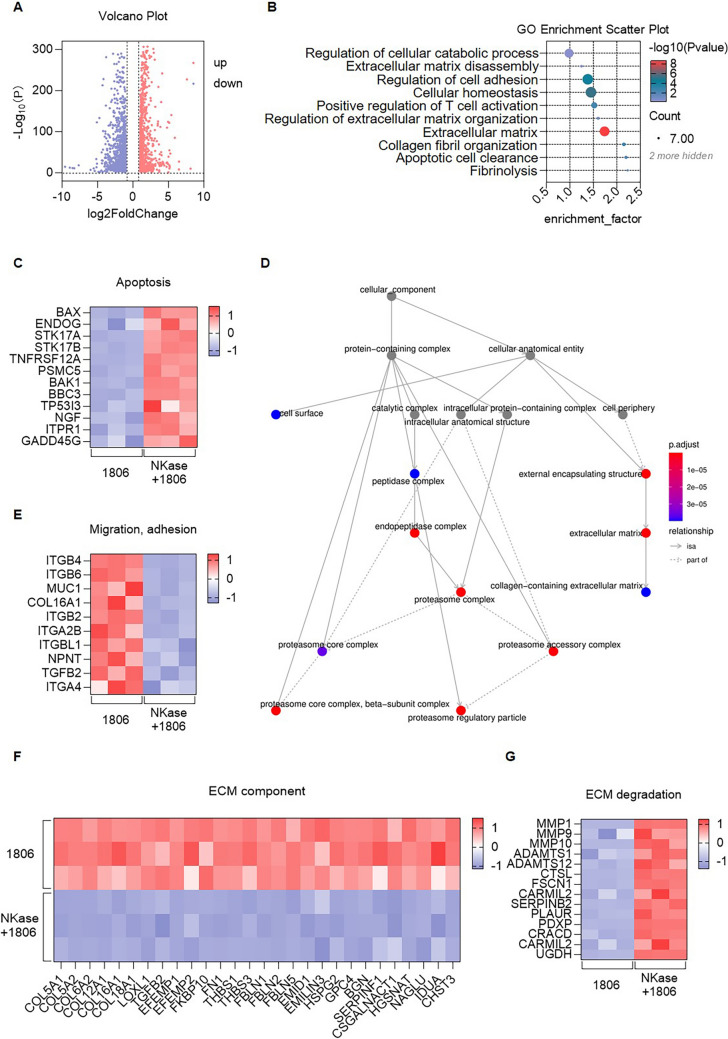

To investigate the impact of nattokinase (NKase) on tumor cell gene expression, we first performed transcriptomic analysis on HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment. A volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) revealed substantial transcriptomic changes following NKase exposure, with numerous genes showing significant upregulation or downregulation (Fig. 5A), indicating that NKase broadly influences tumor gene expression through diverse molecular mechanisms. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was subsequently conducted to explore functional implications of these changes, and the results, visualized through a bubble chart, revealed that NKase treatment significantly affected multiple biological processes, including cell adhesion, extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, fibrinolysis, and apoptosis (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that NKase may exert antitumor effects by modulating key cellular functions and microenvironmental interactions. We analyzed the expression of apoptosis-related genes using a heatmap. Multiple pro-apoptotic genes were significantly upregulated following NKase treatment (Fig. 5C), indicating that NKase may promote tumor cell apoptosis and thus potentiate the cytotoxic activity of MSLN CAR-T cells. GO interaction network analysis of DEGs (Fig. 5D) further demonstrated significant downregulation of genes associated with tumor cell migration and adhesion (Fig. 5E), as well as genes involved in ECM structure and organization (Fig. 5F), suggesting that NKase may impair tumor invasiveness by disrupting cell-ECM interactions. Additionally, analysis of genes related to ECM degradation revealed that NKase significantly upregulated several matrix-degrading enzymes (Fig. 5G), indicating enhanced ECM remodeling. These transcriptomic changes collectively suggest that NKase contributes to tumor microenvironment reprogramming by promoting apoptosis, inhibiting invasion, and facilitating ECM degradation, which may synergize with MSLN CAR-T therapy to improve antitumor efficacy.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of Gene Expression Differences in Tumor Cells Treated with NKase. A Volcano plot illustrating the 1,806 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in tumor cell lines before and after NKase treatment. B GO enrichment bubble chart depicting the functional annotation of differentially expressed genes in tumor cell lines before and after NKase treatment. C Heatmap displaying the expression profiles of apoptosis-related differentially expressed genes in HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment. D Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of differentially expressed genes in HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment. E Heatmap showing the expression patterns of migration- and adhesion-related differentially expressed genes in HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment. F Heatmap presenting the expression levels of extracellular matrix (ECM) component-related differentially expressed genes in HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment. G Heatmap summarizing the expression changes of ECM degradation-associated differentially expressed genes in HCC1806 tumor cells before and after NKase treatment

NKase disrupts tumor-associated fibronectin to enhance MSLN CAR-T cell infiltration

By analyzing the gene expression of tumor cells treated with NKase, we found that the gene FN1 was decreased, which indicated a reduction in the ECM component fibronectin protein [44, 45]. In order to further investigate whether NKase affects the expression of fibronectin in tumor cells and thereby regulates the tumor microenvironment, we first evaluated the remodeling of the ECM by detecting the expression of fibronectin in HCC1806 tumor cells treated with 125 FU NKase. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a marked reduction in fibronectin levels after NKase treatment (Fig. 6A–B), and quantitative fluorescence intensity analysis using ImageJ confirmed the significant decrease, suggesting that NKase effectively promotes ECM degradation. To validate this observation, we performed Western blot analysis to evaluate the expression of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a marker of fibrotic response. The results demonstrated significantly lower expression of both fibronectin and α-SMA in the NKase-treated group compared to controls (Fig. 6C–E), and densitometric analysis using ImageJ further supported these findings, indicating that NKase suppresses the fibrotic activity of tumor cells. To assess whether NKase-mediated ECM modulation enhances CAR-T cell infiltration, we conducted a 3D tumor microsphere infiltration assay using HCC1806 spheroids. MSLN CAR-T cells exhibited significantly greater infiltration in the NKase-treated group than in the control group (Fig. 6D–G), and quantitative analysis revealed a substantial increase in green fluorescence intensity, confirming enhanced CAR-T cell penetration. Finally, to validate these findings in vivo, we performed immunofluorescence analysis of tumor tissues harvested 10 days after MSLN CAR-T cell infusion. Tumors from NKase-treated mice exhibited significantly reduced fibronectin expression compared to controls (Fig. 6H–I), consistent with enhanced ECM degradation. ImageJ-based quantification further confirmed these results. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that NKase improves the tumor microenvironment by promoting fibronectin degradation, reducing fibrosis, and facilitating the infiltration of MSLN CAR-T cells, thereby contributing to enhanced antitumor efficacy.

Fig. 6.

NKase Disrupts Tumor-Associated Fibronectin to Enhance MSLN CAR-T Cell Infiltration. A–B Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated fibronectin degradation in the HCC1806 cell line following treatment with 125 FU NKase. The expression level of fibronectin was quantified using ImageJ software. C–E Western blot analysis confirmed the expression levels of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in the HCC1806 cell line after exposure to 125 FU NKase. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. F–G Three-dimensional microsphere infiltration assays evaluated the in vitro infiltration capacity of MSLN CAR-T cells in both the negative control (NC) group and the 125 FU NKase treatment group. Green fluorescence intensity derived from HCC1806 cells was quantified using ImageJ software. H–I Immunofluorescence staining revealed reduced fibronectin expression in tumor tissues from mice on day 10 post-infusion of MSLN CAR-T cells. Fibronectin levels were quantified using ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent in vitro experiments; ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA

Conclusion

In summary, NKase remodels the tumor microenvironment by degrading fibronectin, reducing fibrosis, and promoting the infiltration of MSLN CAR-T cells. Moreover, it enhances the antitumor activity of MSLN CAR-T cells by improving their activation, reducing exhaustion and apoptosis, and promoting a memory-like phenotype. These effects result in stronger and more durable tumor killing in vitro and in vivo without causing off-target toxicity. NKase is a promising adjuvant that can improve CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors.

Discussion

Despite the remarkable progress achieved by CAR-T cell therapy in hematological malignancies [46, 47], its clinical efficacy in treating solid tumors remains significantly constrained by various factors [48, 49]. Among these, the extracellular matrix (ECM) of tumor cells is widely recognized as a critical barrier limiting the effectiveness of CAR-T cells [50, 51]. The ECM not only provides structural support as an essential component of solid tumors [52], but also forms a dense physical barrier that restricts the infiltration of immune cells, including CAR-T cells, into the tumor mass [53, 54]. Moreover, components such as fibronectin, collagen, and laminin within the ECM can activate immune-suppressive pathways by interacting with integrin receptors [55, 56], thereby further impeding CAR-T cell functionality and inducing cellular exhaustion and inactivation [57]. Consequently, overcoming the ECM barrier and reshaping the tumor microenvironment have emerged as pivotal strategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of CAR-T cells in solid tumors [58, 59].

NKase, a serine protease derived from Bacillus subtilis natto during the fermentation process of natto, exhibits natural fibrinolytic and thrombolytic properties [60]. Several studies have demonstrated that NKase can degrade fibrin and other ECM components, facilitating matrix remodeling and thereby reducing interstitial adhesiveness and mechanical barriers [60]. Furthermore, NKase has been shown to have an excellent safety profile [61], with no significant toxicity reported in both nutritional and clinical studies [62], which supports its potential for use in cancer therapy.

The present study represents the first comprehensive investigation into the synergistic effects of NKase in enhancing the efficacy of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cell therapy in MSLN-positive solid tumors. Our findings indicate that NKase significantly augments the cytotoxic activity of CAR-T cells against tumor cells and improves their functional status at noncytotoxic concentrations. In vitro analyses confirmed that NKase-treated tumor cells exhibited higher lysis rates across multiple effector-to-target (E/T) ratios. Mechanistic studies revealed that NKase mitigates excessive activation of CAR-T cells, as evidenced by decreased expression of activation markers such as CD25 and CD69. Moreover, NKase was found to inhibit the exhaustion phenotype by reducing PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 expression, while also preventing apoptosis, thus prolonging CAR-T cell functional persistence. Additionally, NKase facilitated the differentiation of CAR-T cells into T stem cell memory (TSCM) and central memory (TCM) phenotypes, indicating its potential to support the maintenance of CAR-T cell memory. Transcriptomic analysis further corroborated these observations, showing that NKase treatment significantly upregulated the expression of genes involved in ECM degradation, inhibition of cell adhesion, and promotion of apoptosis, suggesting its multifaceted role in improving CAR-T cell therapeutic outcomes. In vivo experiments additionally confirmed that NKase markedly enhanced CAR-T cell tumor infiltration and antitumor activity, with no apparent systemic toxicity.

Although the present study demonstrates the promising potential of combining NKase with MSLN CAR-T cells for the treatment of solid tumors, several limitations exist. First, the study was conducted primarily using two MSLN-positive tumor models, HCC1806 and OVCAR3. Whether similar outcomes can be achieved in other solid tumor models requires further investigation. Second, the pharmacokinetics, metabolic stability, and long-term immunogenicity of NKase have not been thoroughly explored, and further studies focusing on these aspects are essential for assessing the clinical applicability of NKase in tumor therapy. Additionally, the present study did not extensively examine the direct effects of NKase on ECM-producing cells, such as tumor-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), an area that warrants further exploration.

In conclusion, this study provides compelling evidence that the combination of NKase with MSLN CAR-T cells enhances CAR-T cell infiltration, functional persistence, and antitumor efficacy in solid tumors. The results suggest a promising new approach for improving CAR-T cell therapy, offering novel insights into ECM modulation for cancer immunotherapy. These findings not only broaden the therapeutic potential of ECM-targeting strategies but also provide a solid theoretical foundation for enhancing CAR-T cell effectiveness in solid tumors. Future investigations will be required to further validate the clinical relevance of NKase as an adjunctive treatment in CAR-T cell therapy, with the goal of expanding its application to a wider range of solid tumor indications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the National Natural Science Foundation of China for its generous support of this research (No. 82373183).

Author contributions

Lf. Z.: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, statistical analysis, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. Y. Z.: Data curation, methodology, and writing—review & editing. Xh. Y.: Data curation, methodology and statistical analysis. Ty. C.: methodology and statistical analysis. Jq. L.: Data curation, investigation and statistical analysis. Zg. G.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82373183).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments were conducted at the animal laboratory of Nanjing Normal University in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the university (Approval number: IACUC-20230311).

Consent for publication

All authors hereby unanimously agree to publish this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lianfeng Zhao and Yan Zhang have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Yu WL, Hua ZC (2019) Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy for hematologic and solid malignancies: efficacy and safety-a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 10.3390/cancers11010047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP et al (2019) Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 380(1):45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruella M, Korell F, Porazzi P, Maus MV (2023) Mechanisms of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor-T cells in haematological malignancies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 22(12):976–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu J, Jiang G (2022) The journey of CAR-T therapy in hematological malignancies. Mol Cancer 21(1):194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayed AO, Chang LJ, Moreb JS (2015) Immunotherapy for multiple myeloma: current status and future directions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 96(3):399–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britten CM, Shalabi A, Hoos A (2021) Industrializing engineered autologous T cells as medicines for solid tumours. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20(6):476–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Date V, Nair S (2021) Emerging vistas in CAR T-cell therapy: challenges and opportunities in solid tumors. Expert Opin Biol Ther 21(2):145–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du B, Qin J, Lin B, Zhang J, Li D, Liu M (2025) CAR-T therapy in solid tumors. Cancer Cell 43(4):665–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrea AE, Chiron A, Mallah S, Bessoles S, Sarrabayrouse G, Hacein-Bey-Abina S (2022) Advances in CAR-T Cell Genetic Engineering Strategies to Overcome Hurdles in Solid Tumors Treatment. Front Immunol 13:830292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo S, Xi X (2025) Nanobody-enhanced chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: overcoming barriers in solid tumors with VHH and VNAR-based constructs. Biomark Res 13(1):41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong M, Clubb JD, Chen YY (2020) Engineering CAR-T cells for next-generation cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 38(4):473–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian Y, Li Y, Shao Y, Zhang Y (2020) Gene modification strategies for next-generation CAR T cells against solid cancers. J Hematol Oncol 13(1):54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng S, Che X, Zhang K, Bai Y, Deng H (2025) Potentiating CAR-T cell function in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by inverting the TGF-β signal. Mol Ther 33(2):688–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turley SJ, Cremasco V, Astarita JL (2015) Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 15(11):669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira G, Wu CJ (2023) Dynamics and specificities of T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 23(5):295–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridman WH, Zitvogel L, Sautès-Fridman C, Kroemer G (2017) The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14(12):717–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaillon S, Ponzetta A, Di Mitri D, Santoni A, Bonecchi R, Mantovani A (2020) Neutrophil diversity and plasticity in tumour progression and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 20(9):485–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce JA, Fearon DT (2015) T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 348(6230):74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Liu C, Tu J, Tang M, Ashrafizadeh M, Nabavi N et al (2025) Advances in cancer immunotherapy: historical perspectives, current developments, and future directions. Mol Cancer 24(1):136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng R, Shen K, Liang S, Lyu Y, Zhang S, Dong H et al (2024) Specific ECM degradation potentiates the antitumor activity of CAR-T cells in solid tumors. Cell Mol Immunol 21(12):1491–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao YT, Lv M, Huang XJ, Zhao XY (2025) The mechanisms and countermeasures for CAR-T cell expansion and persistence deficiency. Cancer Lett 626:217771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou X, Zhou J, Xie HY, Nie W (2025) Fusogenic lipid nanovesicles as multifunctional immunomodulatory platforms for precision solid tumor therapy. Small 21(27):e2503134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DePeaux K, Delgoffe GM (2021) Metabolic barriers to cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 21(12):785–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang B, Liu J, Mo Y, Zhang K, Huang B, Shang D (2024) CD8(+) T cell exhaustion and its regulatory mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment: key to the success of immunotherapy. Front Immunol 15:1476904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Zhang L, Wan D, Zhou L, Zheng S, Lin S et al (2021) Extracellular matrix and its therapeutic potential for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6(1):153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedl P, Gilmour D (2009) Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10(7):445–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemm F, Joyce JA (2015) Microenvironmental regulation of therapeutic response in cancer. Trends Cell Biol 25(4):198–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang M, Li J, Gu P, Fan X (2021) The application of nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy: targeting tumor microenvironment. Bioact Mater 6(7):1973–1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Zhou Z, Dang Q, Xu H, Lv J, Li H et al (2022) Immunosuppression in tumor immune microenvironment and its optimization from CAR-T cell therapy. Theranostics 12(14):6273–6290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144(5):646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naba A, Clauser KR, Ding H, Whittaker CA, Carr SA, Hynes RO (2016) The extracellular matrix: Tools and insights for the “omics” era. Matrix Biol 49:10–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ (2006) Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med 4(1):38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miner JH, Yurchenco PD (2004) Laminin functions in tissue morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20:255–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toole BP (2004) Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer 4(7):528–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vihinen P, Kähäri VM (2002) Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Int J Cancer 99(2):157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batlle E, Massagué J (2019) Transforming growth factor-β signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 50(4):924–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmeliet P (2005) VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology 69(Suppl 3):4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE (1993) Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 260(5111):1124–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139(5):871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain RK (2001) Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat Med 7(9):987–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeNardo DG, Brennan DJ, Rexhepaj E, Ruffell B, Shiao SL, Madden SF et al (2011) Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov 1(1):54–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Pei P, Zhou H, Xie Y, Yang S, Shen W et al (2023) Nattokinase-mediated regulation of tumor physical microenvironment to enhance chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and CAR-T therapy of solid tumor. ACS Nano 17(8):7475–7486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen J, Hu J, Gu L, Ji F, Zhang F, Zhang M et al (2023) Anti-mesothelin CAR-T immunotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 72(2):409–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JJ, Ng KY, Bakhtiar A (2025) Extracellular matrix: unlocking new avenues in cancer treatment. Biomark Res 13(1):78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guerrero-Barberà G, Burday N, Costell M (2024) Shaping oncogenic microenvironments: contribution of fibronectin. Front Cell Dev Biol 12:1363004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan AN, Asija S, Pendhari J, Purwar R (2024) CAR-T cell therapy in hematological malignancies: where are we now and where are we heading for? Eur J Haematol 112(1):6–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD et al (2021) Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 398(10297):314–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dabas P, Danda A (2023) Revolutionizing cancer treatment: a comprehensive review of CAR-T cell therapy. Med Oncol 40(9):275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM (2020) Clinical investigation of CAR T cells for solid tumors: lessons learned and future directions. Pharmacol Ther 205:107419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Z, Li Q, Qu C, Jiang Z, Jia G, Lan G et al (2025) A collagenase nanogel backpack improves CAR-T cell therapy outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Nat Nanotechnol. 10.1038/s41565-025-01924-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan T, Zhu L, Chen J (2023) Current advances and challenges in CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors: tumor-associated antigens and the tumor microenvironment. Exp Hematol Oncol 12(1):14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henke E, Nandigama R, Ergün S (2019) Extracellular matrix in the tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer therapy. Front Mol Biosci 6:160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Dou H, Yu X et al (2023) Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: from mechanisms to treatments. Mol Cancer 22(1):48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao Z, Todd L, Huang L, Noguera-Ortega E, Lu Z, Huang L et al (2023) Desmoplastic stroma restricts T cell extravasation and mediates immune exclusion and immunosuppression in solid tumors. Nat Commun 14(1):5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Logie C, van Schaik T, Pompe T, Pietsch K (2021) Fibronectin-functionalization of 3D collagen networks supports immune tolerance and inflammation suppression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Biomaterials 268:120498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flies DB, Langermann S, Jensen C, Karsdal MA, Willumsen N (2023) Regulation of tumor immunity and immunotherapy by the tumor collagen extracellular matrix. Front Immunol 14:1199513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu X, Li Q, Zhu X (2022) Mechanisms of CAR T cell exhaustion and current counteraction strategies. Front Cell Dev Biol 10:1034257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niu C, Wei H, Pan X, Wang Y, Song H, Li C et al (2025) Foxp3 confers long-term efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor-T cells via metabolic reprogramming. Cell Metab 37(6):1426–41.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang N, Liu X, Qin J, Sun Y, Xiong H, Lin B et al (2023) LIGHT/TNFSF14 promotes CAR-T cell trafficking and cytotoxicity through reversing immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Mol Ther 31(9):2575–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weng Y, Yao J, Sparks S, Wang KY (2017) Nattokinase: an oral antithrombotic agent for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms18030523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu X, Zeng X, Mahe J, Guo K, He P, Yang Q et al (2023) The effect of Nattokinase-Monascus supplements on dyslipidemia: a four-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu15194239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen H, Chen J, Zhang F, Li Y, Wang R, Zheng Q et al (2022) Effective management of atherosclerosis progress and hyperlipidemia with nattokinase: a clinical study with 1,062 participants. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:964977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.