Abstract

The increased metabolic activity in cancer cells often leads to higher levels of reactive oxygen species compared to normal cells, which can cause damage to cellular components, including DNA. Cancer cells rely on MTH1 to maintain their DNA integrity and cellular function to counteract this damage. MTH1 is critical in sanitizing oxidized nucleotide pools by removing damaged nucleotides. Inhibition of MTH1 disrupts this repair process, leading to increased DNA damage and cell death in cancer cells. In this study, we present resveratrol (RV) as a potential MTH1 inhibitor. Docking and MD Simulations illustrated the effective binding of RV to the active site of the MTH1 protein, forming a notably stable complex. The fluorescence binding studies estimated a high binding affinity of RV with MTH1 (Ka 6.2 × 105M-1, inhibiting MTH1 activity with IC50 18.13 ± 1.08 µM. The inhibitory effects of RV on the proliferation of breast cancer cells (MCF-7) revealed significant inhibition in cell growth, leading to apoptosis. RV significantly increases ROS production, inducing considerable oxidative stress and ultimately resulting in cell death. Our study offers a rationale for evaluating RV as an MTH1 inhibitor for potential anti-cancer therapy, particularly in breast cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-18855-5.

Keywords: Natural products, MTH1 protein, Resveratrol, Cancer therapy, Drug discovery, MD simulations

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Chemical biology, Diseases, Molecular medicine, Oncology

Introduction

Cancer cells often exhibits a general phenotype of altered redox regulation and elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS)1–4. These heightened concentrations of ROS not only cause direct oxidative damage to DNA but also pose a significant threat to the free pool of nucleotides2. Since the nucleotide pool is more prone to ROS than DNA strands, oxidative damage leads to the production of diverse oxidized nucleotides like 8-oxo-dGTP, 8-oxo-dATP, 2-OH-dATP, and 2-OH-ATP, etc2,5. This oxidative damage is supposed to play a significant role in inducing spontaneous mutagenesis, where these oxidized nucleotides, when integrated into the DNA structure, give rise to errors in base-pairing during processes like replication and repair. These errors, known as base-pair mistranslation, can potentially contribute to genomic instability and ultimately lead to cell death6,7. In particular, 8-oxo-dGTP, being highly mutagenic, not only pairs with dCTP in a Watson–Crick manner but also engages in Hoogsteen base pairing with dATP, with almost similar efficacy. This event is introduced during the DNA replication process8,9.

Various repair enzymes have evolved to prevent the harmful consequences of mis-incorporating oxidized nucleotides and ensure the integrity of the genome. One such enzyme is human MutT homolog 1 (MTH1)7,10,11. MTH1 is an 18-kDa NUDIX phosphohydrolase that efficiently facilitates the hydrolysis of oxidized purine nucleoside triphosphates, including 8-oxo-dGTP, 2-OH-dATP, 8-oxo-GTP, and 2-OH-ATP along with their ribonucleotide analog, converting them into their respective monophosphates9. The MTH1 protein plays a crucial role in sanitizing the oxidized dNTP pool to avoid the integration of these damaged nucleotides within the DNA strands, allowing a protective mechanism for cancer cells to counter mispairing, mutations, and potential cell death2. The MTH1 protein functions to eliminate these mutagenic substrates from the precursor DNA pool, permitting the proliferation of cancer cells. Multiple studies have highlighted the sustenance of elevated MTH1 levels in various cancers, including lung cancer11–13, brain tumour14–17, breast18–21, gastric11,22,23, colorectal cancers10,24, psoriasis25,26, pancreatic ductal11,27,28, oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas29,30and multiple myeloma31–33.

Recently, MTH1 has gained much attention as a non-oncogene addiction target in anticancer treatments, where non-essential MTH1 enzymes become indispensable for the survival of cancer cells34. Several studies35,36 have shown that MTH1 is non-essential in normal cells, as oxidative stress levels are lower and the demand for sanitizing oxidized nucleotides is minimal, however, its expression is frequently upregulated in cancer cells, where it plays a critical role in preventing the incorporation of oxidized nucleotides into DNA and thereby supports tumor cell survival under high ROS conditions. Thus, targeting MTH1 gives the most obvious benefit of reducing the acute side effects of many contemporary cancer treatments6,37. Inhibition of MTH1 falls under the cancer phenotypic lethality category, providing broader applicability as it can be used irrespective of the cancer genotype38. Natural compounds have gained popularity as anticancer agents as they minimize the side effects of chemotherapy39. The emerging resistance towards chemotherapeutic drugs enhances the use of natural compounds as anticancer agents, reducing synthetic drug doses when given as a complement to traditional therapy39,40. For the first time, we present the binding mechanism and inhibitory effectiveness of Resveratrol (RV) as a natural inhibitor of the MTH1 enzyme.

RV, chemically known as 3,4’,5-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene is a non-flavonoid polyphenol that acts as a phytoestrogen with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and anticancer properties41. RV is often referred to as a ‘miracle’ nutraceutical in advancing cancer therapy by mitigating cancer, along with possessing various bioactivities, including antidiabetic and antiaging activities42,43. RV effectively suppresses cancer cells44 via inhibiting STAT3/SOCS-145, NAF-146, SIRT1/p38MAPK, and NO/DLC1 [43] signaling pathways. It was a chemo-preventive agent across all four critical stages of carcinogenesis: initiation, promotion, progression, and metastasis47. Several studies have concluded that RV has the potential to reverse multidrug resistance in tumor cells and intensify their sensitivity to contemporary synthetic drugs when combined43. RV has shown promising anticancer efficacy against several cancers, including hepatic cancer, pancreatic cancer, postmenopausal breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, etc., along with skin and hematological malignancies48,49.

In the current study, we have validated RV as a potent natural inhibitor of MTH1 by carrying out molecular docking-based virtual screening. This was followed by fluorescence and in vitro studies with cell-free and cell-based enzyme assays with the purified recombinant MTH1 enzyme. RV exhibits notable anti-cancer activity in breast cancer by modulating multiple signaling pathways, inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, making MCF-7 cells a well-established model for its evaluation50,51. MD simulations (200ns) also suggested a high binding affinity of RV to MTH1, highlighting RV as a prominent chemo-preventive and anticarcinogenic phytochemical.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Plasmid pET28b + with His tagged MTH1 gene was commercially obtained from Biomatik®. The RV compound (Cat. No. R5010) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HisPur™ Ni-NTA resin (Cat. No. 88221) and plasmid purification kits (Cat. No. 12123) were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). BIOMOL® Green reagent (Cat. No. BML-AK111-0250) was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). The cell lines MCF7 were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (Pune, Maharashtra, India). All other reagents used in buffer preparation and other analyses were procured from HiMedia Laboratories (Mumbai, India) and Merck (USA)) as mentioned in our previous paper52 with catalogue no. ICN15002905 (Kanamycin Monosulfate), 02103133 (Tris (Ultrapure, > 99.9%), M575 (Luria Broth), M557 (Luria Agar), 88221 (HisPur™ Ni-NTA Resin), 108603 (Triton X-100), 1.06404 (NaCl), 1.06667(SDS), 1.08418(EDTA), 1.07827(Imidazole).

Drug likeness prediction

RV was selected in this study because of its efficient anti-oncogenic potential53–55. The ligand RV was subjected to PASS analysis to evaluate its biological attributes about the “likelihood of being active (Pa)” and “likelihood of being inactive (Pi).” The same compound underwent additional assessment for its ADMET properties, encompassing absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. These factors collectively constitute crucial criteria for a drug to progress through clinical trials successfully.

Molecular docking

The human MTH1 crystal structure, resolution 1.73 Å, was downloaded from the Protein Databank (PDB code: 6JVF). The molecular docking study via InstaDock 47 was conducted to evaluate binding affinity and ligand efficiency of RV to MTH1, in a similar fashion to the one we already reported52. The grid boxes defined in the blind search were generated with sizes − 9.053, − 14.418, and 13.326, and the size parameters of X, Y, and Z coordinates were 50 Å, 50 Å, and 53 Å, respectively56. All the possible docked conformations of RV with MTH1 were analysed on PyMOL and Discovery Studio Visualizer. The Ligands showing polar contacts within 3.5 Å with MTH1 residues and interacting with the binding pockets of MTH1 were considered good leads and were further evaluated. A detailed interaction analysis further supported the docking results.

MD simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is used to understand structural dynamics and interactions between a ligand and a protein molecule57. We assessed the stability and structural dynamics of our MTH1-RV complex through a 200 ns simulation by employing the CHARMM36 force field. The simulation of both the MTH1-RV complex and the native form of the MTH1 protein was conducted using GROMACS v5.5.1. Details of the MD simulation method are described in our previous communications52.

Expression and purification of MTH1 protein

We have employed our established published protocol to express and purify recombinant MTH1 protein52. The purity of the MTH1 protein was further assessed via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and activity was checked by enzymatic assay as previously reported52. The expression and purification of MTH1 involve several key steps. First, the MTH1 gene is cloned into an expression vector and introduced into E. coli for protein production, typically induced with IPTG. After cell lysis and clarification to remove debris, the protein is purified using affinity chromatography (His-tag) for higher purity. The purified protein is concentrated, and its purity and activity are confirmed using techniques like SDS-PAGE and enzyme assays.

Fluorescence binding studies

The binding studies of RV, the natural compound, with MTH1 protein (4µM), were performed on a Jasco Spectrofluorometer at 25 °C52. The emission spectra were recorded within the 300–400 nm range, with excitation at 280 nm58. We plotted the resulting quenching spectra of RV using SigmaPlot. We employed the inverse correlation, where fluorescence intensity decreased gradually with increasing compound concentration, to calculate the kinetic parameters (Ka and n) via a modified Stern-Volmer equation as described53. Within this equation, Fo indicates the fluorescence intensity of MTH1 when compound RV is absent, while F represents the fluorescence intensity of MTH1 at a particular concentration of RV at λmax.

Enzyme inhibition assay

To validate the inhibitory potential of RV on MTH1 protein, an enzymatic assay was employed as per previously published protocols38 in an increasing dose-dependent manner wherein 5µM of purified human recombinant MTH1 was incubated with 0-100µM range of RV. We utilized a standard phosphate curve to measure the reduction in MTH1 activity in terms of the quantity of phosphate released upon treatment with increasing concentrations of the RV compound. The inhibition of MTH1 activity was depicted as a percentage on the graph.

Cell proliferation assay

The cell lines used for all cell-based assays are MCF-7 (passage numbers 37–40) and MDA-MB-231, maintained in conditions of 5% CO2 humidification at 37 °C incubation. The control HEK293 cell Line was maintained under similar conditions to ensure consistency across experiments. Five thousand cells were seeded per well in a 96-well plate, and RV was added after 20 h of post-seeding, followed by 72 h incubation. Following our previously published protocols, the MTT was added in a conc. Of 10 µL of 5 mg/mL in each well and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 2–4 h. After removing the media, 100 µL of DMSO was introduced to each well, ensuring thorough mixing to dissolve any sediments. The absorbance was taken at 595 nm wavelength via a microplate reader59,60.

Experimental parameters and statistical considerations

HEK293, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, Maharashtra, India. HEK293 cells were used as a control. The authenticity of the cell lines was confirmed through Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling, and they were routinely tested for Mycoplasma contamination using a PCR-based assay. All experiments were conducted with a minimum of three independent biological replicates (n = 3), each performed in technical triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was assessed using t-test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. The two-tailed P value equals 0.0002 (for MTT). By conventional criteria, this difference is considered to be extremely statistically significant.

Cell viability and apoptosis assay

Cell seeding and adherence were done in a similar method as mentioned above, to which IC50 dose of RV was given for 72 h followed by the addition of 1µM Calcein-AM (HiMedia, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) and one µg/ml Propidium Iodide (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) for 30 min. Similarly, the cells were stained with Annexin V CF® 555 Conjugate (Biotium, 29004R) and NucBlueTM Live Cell stain ReadyProbesTM (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) for 30 min for the apoptosis assay. Imaging at 20X and 40X magnification, respectively, was taken by Leica DMEL LED Fluo (Wetzlar, Germany) microscope.

Assessment of DNA damage

The cells were grown in poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 20 min, and permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100 prepared in 1X PBS for 10 min. Cells were blocked with 10% FBS prepared in 1X PBS for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies (1:500 dilution, anti-γ-H2AX and anti-53BP1, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C for overnight. Cells were washed three times with 1X PBS for 10 min each, incubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (BioLegend Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for one h, washed three times on ice with 1X PBS for 10 min each, and counterstained with 1 µg/mL DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using antifade (n-propyl gallate, Sigma-Aldrich) prepared in DMF and glycerol. Images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-2 confocal microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 100× magnification. Image quantification was performed with ImageJ (NIH, Maryland, USA).

Detection of cellular and mitochondrial ROS

Likewise, 8,000 seeded cells/well were given RV treatment (IC50 dose) for about 20 h, to which 2µM MitoSOXTM Red (Invitrogen) stain and NucBlueTM Live Cell stain ReadyProbesTM (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) were added. After 30 min, Imaging at 40X magnification was done under a Leica DMEL LED Fluo (Wetzlar, Germany) microscope, followed by intensity quantification via ImajeJ software. The cells were grown on poly L-lysine-coated glass coverslips. Following the treatment, the cells were incubated with 10 µM of H2-DCFDA (10 µM, MCE, Cat. No. HY-D0940) or MitoSOXTM Red (Invitrogen) for 30 min and were counter-stained with 500 ng/ml Hoechst (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-2 confocal microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 100× magnification. Image quantification was performed with ImageJ (NIH, Maryland, USA).

Results

Drug-likeness predictions of resveratrol

The compound RV was selected based on its high therapeutic values, as mentioned42–49,61. The biological properties of RV were assessed via the PASS server, i.e., prediction of activity spectra for the substance’s server. The resulting biological activity spectrum of RV is shown in Table 1, representing the intrinsic properties of RV based on its structure and physical-chemical characteristics. The resultant predicted biological activity was scored as either active or inactive. The probability of attaining a compound’s respective predicted biological activity is high when Pa > 0.7. The Pa and Pi values in Table 1 are represented without decimal points for formatting consistency. For interpretation, these should be read as decimals (e.g., 0941 as 0.941). All reported Pa values were above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7, indicating a high probability of relevant biological activity.

Table 1.

PASS analysis: biological activity prediction of Resveratrol against MTH1.

| S. No. | Compound | Pa* | Pi* | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Resveratrol (RV) | 0941 | 0004 | Membrane Integrity agonist |

| 0912 | 0003 | JAK2 expression inhibitor | ||

| 0839 | 0009 | HIF1A expression inhibitor | ||

| 0744 | 0011 | Apoptosis agonist | ||

| 0901 | 0005 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase inhibitor | ||

| 0796 | 0004 | Preneoplastic conditions treatment |

These properties were further supported by ADME screening of the compound, highlighting its pharmacokinetics properties, lipophilicity properties, water solubility properties, drug likeliness properties, medicinal chemistry properties, and physiochemical properties (Table 2). This shows that RV is a water-soluble drug that is well absorbed when compared to lipid-soluble medications.

Table 2.

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity (ADMET) properties of Resveratrol.

| ADME study of Phytochemical | Resveratrol (RV) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physiochemical properties | Molecular weight | 228.24 g/mol |

| Number of heavy atoms | 17 | |

|

Number of aromatics heavy atoms |

12 | |

| Fraction Csp3 | 0.00 | |

|

Number of rotatable Bonds |

2 | |

|

Number of H-bond acceptors |

3 | |

| Number of H-bond donors | 3 | |

| Molar refractivity | 67.88 | |

| Topological polar surface area (TPSA) | 60.69 A° | |

| Lipophilicity | Log Po/w (iLOGP) | 1.75 |

| Log Po/w (XLOGP3) | 3.13 | |

| Log Po/w (WLOGP) | 2.76 | |

| Log Po/w (MLOGP) | 2.26 | |

| Log Po/w (SILICOS-IT) | 2.57 | |

| Consensus Log Po/w | 2.48 | |

| Water solubility | Log S (ESOL) | 3.62, soluble |

| Log S (Ali) | 4.07, Moderately soluble | |

| Log S (SILICOS-IT) | 3.29, soluble | |

| Pharmacokinetics | GI absorption | High |

| BBB permeant | Yes | |

| P-gp substrate | No | |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | Yes | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | |

| CYP2D6 substrate | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | |

| Log Kp (skin permeation) | —5.47 cm/s | |

| Drug likeliness | Lipinski | Yes |

| Ghose | Yes | |

| Veber | Yes | |

| Egan | Yes | |

| Muegge | Yes | |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | |

| Medicinal chemistry | PAINS | 0 alert |

| Brenk | 1 alert: stilbene | |

| Leadlikeness | No; 1 violation: MW < 250 | |

| Synthetic accessibility | 2.02 | |

*The Pa and Pi values are represented without decimal points for formatting consistency. For interpretation, these should be read as decimals (e.g., 0941 as 0.941).

Moreover, its GI absorption is high, making it suitable as an orally administered solution as it is easily absorbed by the human intestine, which is usually where drugs are absorbed more quickly. RV can overcome the biological barrier of excretion from the cells as it is not a P-glycoprotein substrate. RV is a blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeant that minimizes the side effects and toxicities and efficiently enhances the potency of pharmacologically active brain-restricted drugs. Further, RV became an inhibitor to CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4, allowing RV to metabolize and not excrete. Additionally, RV was found to respect all the drug-likeness rules, including Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge. Besides, RV was additionally evaluated for its synthetic accessibility, ranging from 1 (easy to synthesize) to 10 (hard to synthesize). The synthetic accessibility was nearly two, indicating that RV can be synthesized easily.

Molecular docking and interaction analysis

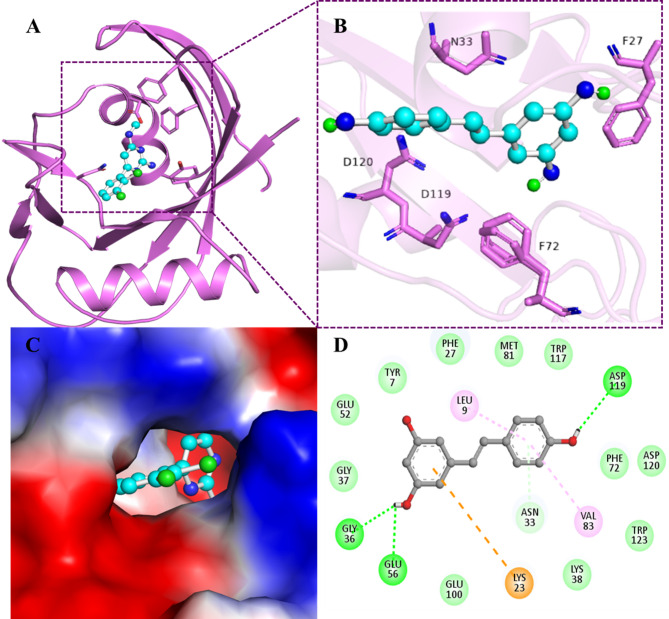

The molecular docking performed via InstaDock62 revealed that the compound RV binds to MTH1 protein with significantly high binding affinity, −8.2 kcal/mol, and appreciable Ligand efficiency, 0.47. We also thoroughly examined the docking results to investigate the molecular interactions of RV with the functionally significant residues of the MTH1 protein. Molecular docking gives us insight into receptor and protein binding aspects, including the favorable positioning and configuration of compound binding to the active site of MTH1. The interaction analysis shown in Table 3 illustrates that RV favored the substrate binding pocket of MTH1 by forming various significant interactions (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Different types of interactions of Resveratrol (RV) with MTH1 interacting residues.

| Compound | Types of interactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen bonds | van der Waals | Pi-Cation | Pi-Alkyl | |

| Resveratrol |

Gly36 Glu56 Asp119 Asn33 |

Gly37 Glu52 Tyr7 Phe27 Met81 Trp117 Phe72 Asp120 Trp123 Lys38 Glu100 |

Lys23 |

Leu9 Val83 |

Fig. 1.

Structural representation of MTH1. (A) A cartoon representation showing a docked RV in the active site cavity of MTH1. (B) Shows the interaction between RV and MTH1. (C) Surface view showing RV in the active site cavity of MTH1. (D) 2D illustration showing different interactions between RV and MTH1.

RV forms strong hydrogen bonds with Gly36, Glu56, Asp119, Asn33 along with strong van der Waal bond association via Gly37, Glu52, Tyr7, Phe27, Met81, Trp117, Phe72, Asp120, Trp123, Lys38 and Glu100. Several other important interactions were also observed, like Pi- cation with Lys23 and Pi-alkyl with Leu9 and Val83. RV forms hydrogen bonds with critical residues such as Gly36, Glu56, Asp119, and Asn33, stabilizing its binding within the active site and disrupting the catalytic activity of enzyme. Additionally, strong van der Waals interactions with residues like Gly37, Glu52, Tyr7, Phe27, Met81, Trp117, Phe72, Asp120, Trp123, Lys38, and Glu100 contribute to the overall binding stability and specificity. These interactions collectively interfere with MTH1 ability to hydrolyse oxidized nucleotides, thus impairing its protective role in cancer cells under oxidative stress.

MTH1 was docked with the synthetic inhibitor TH287 to compare its binding site residues with those of RV. The binding affinity of TH287 was determined to be −8.1 kcal/mol, which is lower than that of RV, with a Ligand efficiency of 0.4765. Both compounds shared a significant number of common binding site residues, including Asn33, Trp117, Asp119, Phe72, Val83, Leu9, Met81, Tyr7, Phe27, Gly37, Glu56, Lys23, and Gly36 (Figure S2 & Table S2). The aminopyrimidine group in TH287 forms hydrogen bonds with Asn33 at the MTH1 active site, prompting MTH1 to adopt a closed conformation, thereby enhancing its inhibitory potency63.

Similarly, RV interacts with MTH1 through hydrogen bonds with Asn33, Glu56, Asp119, and Gly36, resulting in a strong binding affinity. Trp117 engages in a pi-cation interaction with TH287, while it forms van der Waals interactions with RV. Additionally, the methyl group of TH287, with minimal steric hindrance, occupies a hydrophobic cavity comprising Phe72, Phe74, and Phe137. Studies indicate that Phe72 plays a critical role in ligand recognition by MTH164. Furthermore, TH287 establishes van der Waals forces and a pi-cation interaction with Phe74 and Phe72, respectively. Another compound, BAY-707, was employed as a positive control in one of our previous publications65 exhibiting a binding affinity of − 6.6 kcal/mol demonstrated a much lower binding affinity compared to RV (−8.2 kcal/mol). RV advantage lies in its natural origin, established safety profile, and multi-targeting potential, making it a promising candidate for drug repurposing.

It is well known that the residue Asn33, which forms a hydrogen bond with RV, is essential for substrate specificity66. The Trp117 residue that bonds via van der Waals with RV is an important residue for binding since the two rings present are known to be involved in ring stacking67. Asp119 and Asp120 are crucial residues in binding and are involved in substrate selectivity68. The interaction analyses revealed that the compound RV binds to the binding pocket of MTH1.

To further validate the binding specificity of RV toward the MTH1 active site, we performed molecular docking with key mutants including Asn33Ala, Asp119Ala, Asp119Asn, Asp120Ala, Phe72Ala, and Trp117Ala. The Asn33Ala mutant abolished hydrogen bonding with Asn33 and weakened π-alkyl interaction with Val83, while Asp119Ala caused a complete loss of hydrogen bonding, confirming the importance of both residues in RV stabilization. Although Asp119Asn is a conservative mutation, it still altered the binding orientation of RV, highlighting the critical role of Asp119 side chain. Asp120Ala showed minimal effect, indicating a lesser role in RV binding. Phe72Ala disrupted hydrophobic interactions, and Trp117Ala abolished aromatic stacking, both impairing ligand stabilization. These findings support that RV binds selectively to the enzymatic cleft of MTH1 and that perturbation of these residues’ compromises RV interaction, thus reinforcing the role of these amino acids in the molecular recognition and inhibitory mechanism of RV against MTH1. The two-dimensional interaction diagrams for the mutant-RV complexes are given in Supplementary Figure S3.

MD simulations

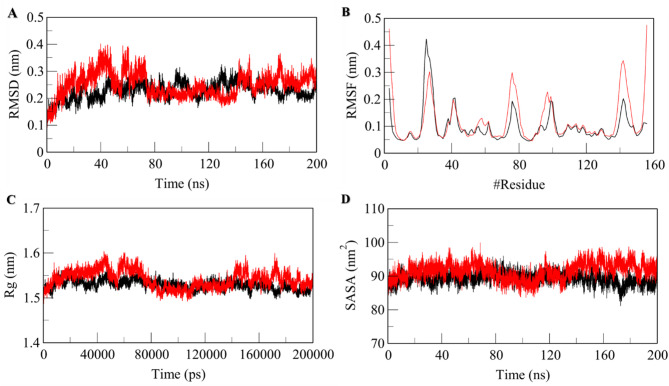

MD Simulations give us insight into protein-ligand interactions, including the structural dynamics and functional mechanisms in an explicit solvent. environment69. This powerful computational technique is utilized to assess the conformational dynamics, stability, and interaction mechanism of MTH1 in a free-state and MTH1in complex with RV for a 200ns time scale. This shows the binding effects of RV in modulating the structural and dynamic behavior of native MTH1. Some important MD parameters, such as RMSD (nm), RMSF (nm), Rg (nm), SASA (nm2), and the number of Hydrogen bonds of free MTH1 and MTH1-RV, were calculated, and the values of these parameters are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean values for the important MD parameters were calculated for MTH1 before and after Resveratrol binding.

| System | RMSD (nm) | RMSF (nm) | Rg(nm) | SASA (nm2) | #H-bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTH1 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 89.3 | 102 |

| MTH1-Resveratol | 0.25 | 0.12 | 1.5 | 91.5 | 98 |

Structural deviations

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) helps us to understand the conformational changes induced upon the binding of a molecule to a protein. The compound RV can trigger certain structural deviations when binding to MTH1. The dynamic behavior and stability of MTH1 upon binding to RV can be accessed via RMSD. The resultant RMSD value obtained for native MTH1 is 0.23 nm, and MTH1 upon binding to RV is 0.25 nm, as mentioned in Table 4, which indicates that RV upon binding to MTH1 doesn’t induce any significant conformational changes and the resultant complex, MTH1-RV complex is highly stabilized. The RMSD plot initially shows a small increment from 10 to 60 ns upon RV binding, which could be attributed to the initial adjustment orientation of RV in the binding pocket of MTH1 (Fig. 2A). The minimal RMSD fluctuations observed during the 200-ns MD simulations indicate the stability of the MTH1-RV complex, suggesting that RV maintains a consistent binding conformation within the active site over time. This stability is further supported by the strong hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions with key residues, as discussed. The stable interaction profile enhances confidence in ability of RV to effectively inhibit MTH1 enzymatic activity under physiological conditions, which is crucial for its therapeutic potential.

Fig. 2.

Structural deviations of MTH1 before and after binding of RV to MTH1 as a function of time. (A) RMSD Plot and (B) RMSF plot. Structural compactness of native MTH1 and RV bound MTH1 as a function of time. (C) Time evolution of Rg plot and (D) SASA plot. The values represent MD simulation carried for a 200ns time scale. The black line represents MTH1 in its apo form, while the red lines represent the MTH1-RV complex.

Additionally, the structural deviations and stability of the MTH1-RV complex were validated via Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), which measures the impact of the average fluctuation of each interacting residue. The RMSF values calculated for residual movements and structural flexibility were found to be 0.10 nm and 0.12 nm for apo MTH1 and MTH1-RV complex, respectively (Table 4). The slight increase in RMSF values can be due to conformational changes in RV to adjust within the binding pocket of MTH1. The random residual fluctuations plotted for each residue present in MTH1 backbone before and after binding to RV displayed the minimal changes that indicate the stabilization of the MTH1-RV complex (Fig. 2B).

Analysis of RMSD and RMSF plots reveals that RV binding induces conformational changes, particularly in the active site region, including key loops and residues such as Gly36, Glu56, and Asp119. The RMSD analysis shows that the MTH1-RV complex stabilizes after an initial fluctuation, indicating a stable binding conformation. RMSF plots highlight increased flexibility in regions surrounding the active site, such as the phosphate-binding loop, which could hinder substrate binding and enzyme activity. These changes support the hypothesis that RV disrupts MTH1 functional dynamics, impairing its ability to hydrolyse oxidized nucleotides. This provides a comprehensive understanding impact of RV on MTH1 structure and function.

Structural compactness

The structural compactness was measured regarding the radius of gyration (Rg) and Solvent accessible surface area (SASA). The Rg is used to analyze a protein’s compactness, folding behavior, and overall conformation by studying its tertiary structure. The average Rg calculated for MTH1 before binding to RV was 1.5 nm (Table 4). The Rg plot displays the maintained Rg equilibrium throughout the simulation trajectory, indicating the maintained structural stability upon binding of RV to MTH1 (Fig. 2C). Also, no structural switching was observed during RV binding. The SASA characterizes the interface between a protein and its surrounding solvent, considering its surface and electrostatic properties. By looking at how solvent molecules behave on the surface of a system under different conditions, one can analyze the conformational dynamics of a protein in different solvent environments. The SASA values calculated were 89.3 nm2 and 91.5 nm2 for native MTH1 and MTH1 upon binding to RV, respectively (Table 4). The slight increase in SASA can be attributed to the expanded surface area of MTH1 in the presence of RV due to the exposure of some internal residues to the solvent-accessible surface.

The SASA plot displayed a stable trajectory and no significant changes throughout the simulation, indicating that MTH1 maintained its structural stability when interacting with compound RV (Fig. 2D). The slight increase in SASA upon RV binding does suggest subtle conformational changes in MTH1. These changes are primarily localized around the active site and regions involved in substrate binding, which may lead to altered accessibility and dynamics of the enzyme. Such shifts could impact the ability of MTH1 to accommodate its natural substrate, thereby inhibiting its catalytic function. While the observed changes in SASA are modest, they are significant enough to indicate potential disruption of MTH1 enzymatic activity, contributing to the therapeutic effect of RV.

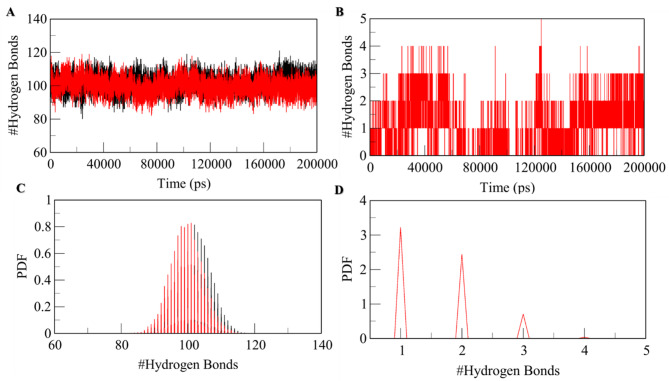

Dynamics of hydrogen bonds

The dynamics of the MTH1 Hydrogen bond is an essential parameter for assessing the molecular recognition, directionality, and specificity of protein-ligand interactions, which examines the stability of the protein-ligand complex. The 3D structural stability is recognized and maintained by hydrogen bonds formed within the protein called intramolecular hydrogen bonds. On the same Line, we have computed the dynamics of intramolecular hydrogen bonds paired within 0.35 nm for both the native MTH1 and MTH1-RV complex systems. The resultant no. of hydrogen bonds was 102 before the binding of RV and 98 after the binding of RV (Table 4). This reduction in hydrogen bonds after RV binding can be due to occupied specific intramolecular spaces in the binding pocket of MTH1. The hydrogen bond analysis and the PDF (Probability Distribution Factor) show the stability of the MTH1-RV complex throughout the simulation with nominal change (Fig. 3A&B). The intramolecular hydrogen bond analysis illustrates the forming of a maximum of 5 intramolecular hydrogen bonds within the MTH1 binding pocket and RV, out of which, on average, 1–2 hydrogen bonds formed exhibit higher stability and 3–5 hydrogen bonds have some degree of fluctuations (Fig. 3C&D).

Fig. 3.

Time evolution and stability of hydrogen bonds formed. (A) Intramolecular hydrogen bonds in MTH1. (B) Hydrogen bonds formed within the MTH1-RV complex and (C & D) hydrogen bond distribution probability between RV and MTH1. All bond pairs are within 0.35 nm.

Secondary structure dynamics of MTH1

The overall alterations in a protein structure depend on the dynamic conformational changes of residues in the secondary structure. By examining the content of a protein’s secondary structure, one can apprehend its polypeptide chain’s conformational behaviour and folding mechanism. To assess the stability of the MTH1-RV complex, we disassembled the secondary structure elements of MTH1, including α-helix, β-sheet, and β-bridge coil, and bent. We turned into individual residues at each timed lap before and after the binding of RV. The average count of each element was calculated and plotted over time (Supplementary Table S1). The resultant analysis revealed that the secondary structural elements remain relatively stable in MTH1 before and after the binding of RV, and the equilibrium is maintained throughout the simulation (Figure S1). However, slight alterations were observed in the secondary structure contents of MTH1 when it was bound to RV. Still, no significant changes were observed, indicating that the resultant complex, MTH1-RV complex, is highly stable. As observed during our analysis, the slight alterations in MTH1 secondary structure upon RV binding are primarily localized near the active site and substrate-binding regions. These changes likely destabilize the enzyme catalytic conformation, reducing its ability to hydrolyse oxidized nucleotides effectively. Such structural disruptions can impair MTH1’s protective role in cancer cells under oxidative stress, contributing to its inhibition. Similar secondary structure changes have been reported with other MTH1 inhibitors52suggesting this is a common mechanism of action.

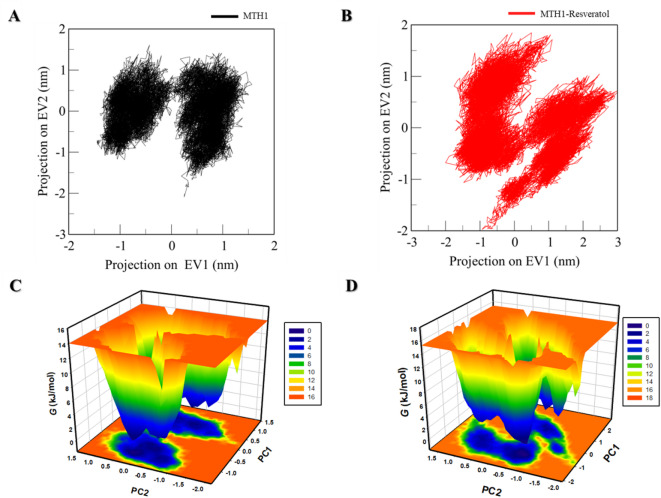

Principal component and free energy landscape analyses

The principal component analysis (PCA) is an important parameter to assess the cumulative movement of atoms, specifically projections of Cα atoms. These are pivotal in defining conformational dynamics of native MTH1 and MTH1-RV complex, characterized by eigenvectors. The same plots are depicted in Fig. 4A & B, which explain the 2D representation of the tertiary conformations of apo MTH1 and MTH1-RV complex along the eigenvectors 1 and 2. The native MTH1 and the MTH1 with RV occupy two subspaces, but some variability was observed in the MTH1-RV system compared to the free state of MTH1. Still, overall switching was not seen in the motion of the protein upon ligand binding.

Fig. 4.

PC analysis. The 2D projections of MTH1 trajectories on eigenvectors exhibited varying orientations over time of (A) native MTH1 and (B) MTH1-RV complex. The Gibbs energy landscape obtained for (C) free MTH1 and (D) MTH1-RV complex. Black and red represent the values extracted for native MTH1 and MTH1-RV complex, respectively.

The folding mechanism of a protein can be assessed through the analysis of its free energy landscape (FEL), which helps comprehend both the global and local minima points in the energy landscape of a protein. The FEL of both systems is depicted in Fig. 4C&D. In the plots, the deep blue color represents states with deficient energy, indicating their proximity to the native states. The free state of the MTH1 and bound state of MTH1 both showed two large, almost coinciding basins, suggesting the stability of the MTH1-RV complex forming over 200ns.

Expression and purification of the MTH1 protein

The expression of full-length MTH1 was carried out in E. coli strain codon + cells and successfully induced by 1mM IPTG. The MTH1 protein was purified via a one-step Ni-NTA affinity chromatography method, followed by purity confirmation by visualizing a prominent 18-kDa band on SDS-PAGE52. The functional activity of the MTH1 protein was determined by a malachite-based assay, which utilizes the conversion of dGTP to dGMP and pyrophosphate by MTH1. The released pyrophosphate gets further hydrolyzed to inorganic phosphate by inorganic pyrophosphatase enzyme. This hydrolyzed phosphate, reacting with malachite green and ammonium molybdate, develops a green-colored complex measurable at 630 nm on an ELISA Plate reader, indicative of MTH1 functional activity. The resultant linear relationship between the amount of inorganic phosphate released and the dGTP substrate hydrolyzed confirms that the purified recombinant MTH1 is functionally active. The maximum activity of MTH1 protein was observed at 5µM MTH1 and 50µM concentration of dGTP substrate, following which the saturation was attained. The same concentrations of MTH1 and dGTP substrate were used in further experiments to investigate the inhibitory potential of RV.

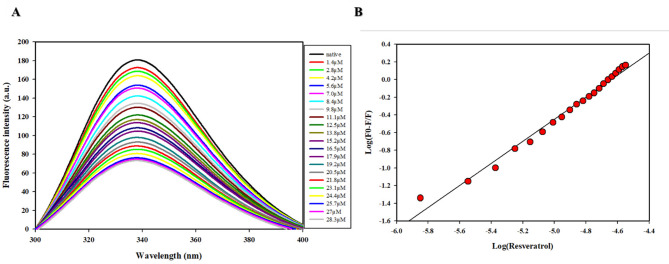

Fluorescence binding studies

The above-mentioned in-silico results were further validated by in vitro studies. The fluorescence binding studies were used to examine the alterations in the local microenvironment of aromatic amino acid residues of a polypeptide in a protein-ligand interaction. The MTH1-RV interaction was studied via fluorescence quenching, and various parameters such as binding constant (Ka) and number of binding sites (n) were calculated based on a modified Stern-Volmer plot.

This study is a fluorescence quenching study, where RV interacts with the MTH1 protein and reduces its fluorescence intensity. As the concentration of RV increases, the quenching effect becomes more pronounced, which indicates a stronger binding interaction between RV and MTH1. This occurs when the fluorophore and the quencher (in this case, RV) form a non-fluorescent complex. The interaction prevents the fluorophore from emitting light, leading to a decrease in fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence signal was measured to determine the binding kinetics and affinity of the interaction between MTH1 and the RV. As observed in Fig. 5, there was a significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity of MTH1 with the addition of compound RV. This shows that the compound RV is binding to the active site of MTH1. The deduced modified Stern-Volmer plot for quenching data analysis revealed that RV binds to MTH1 with a binding constant (Ka) 6.2 × 105M-1. The number of binding sites per MTH1 molecule (n) 1.2 indicates a solid protein-ligand binding. The compound RV displayed high affinity towards MTH1 and was further investigated with inhibition analysis to justify its inhibitory potential against MTH1.

Fig. 5.

Showing binding studies of RV with MTH1. (A) The fluorescence emission spectra show quenching of MTH1 upon titration with RV. MTH1 (4µM) was excited at 280 nm, and emission spectra were recorded between 300–400 nm. (B) The Modified Stern-Volmer plot was employed to analyse the quenching data and estimate RV’s binding constant (Ka).

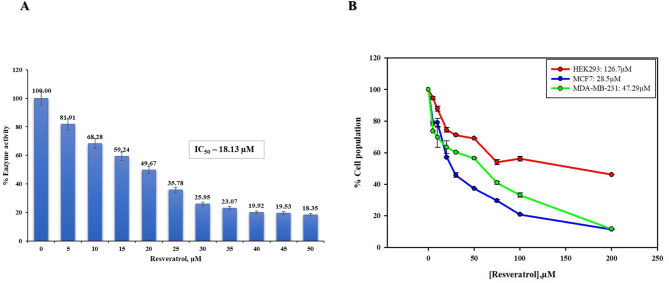

Enzyme inhibition

The inherent dGTPase activity of MTH1, which was utilized to study the enzymatic activity of MTH1 protein, was further incorporated to evaluate the inhibitory potential of a natural compound, RV, towards MTH1. The potency of RV to inhibit MTH1 activity was assessed using a malachite green-based absorbance assay in a coupled enzymatic reaction. As observed, RV inhibited the activity of MTH1 in a concentration-dependent manner, where a gradual reduction in MTH1 activity was seen in increasing concentration of the compound. The same was graphed as a percentage inhibition versus increasing compound doses, based on which the IC50 value was calculated. The IC50 value calculated was 18.13 ± 1.08 µM (AAT bequest was used for calculating the IC50 value). This shows the effectiveness of RV in suppressing the enzymatic activity of MTH1 at the micromolar range. The effective inhibition of MTH1 activity by RV is shown in Fig. 6A.

Fig. 6.

(A) The plot illustrates the inhibition of MTH1 dGTPase activity with increasing concentrations of RV. (B) The antiproliferative effects of RV on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells were assessed using the MTT assay. These cells were subjected to increasing concentrations of RV within the range of 0–200µM over 72 h. The percentages of viable cells were determined in comparison to untreated control cells. The results show a highly significant reduction in cell viability (two-tailed p < 0.0001).

Experiments were performed with other flavonoids, such as baicalin and harmaline, as reported in our previous publications70. These compounds demonstrated IC50 values of 38.9µM and 56.3µM, respectively, compared to the RV IC50 of 18.13 ± 1.08 µM. This indicates that baicalin and harmaline, while capable of interacting with MTH1, exhibit lower inhibitory potency compared to RV. The more potent inhibitory effect of RV can be attributed to its specific interactions with critical residues in the MTH1 active site and its ability to form a more stable complex, as reflected in binding scores and MD simulations. These findings suggest that RV has a more pronounced and effective inhibitory profile against MTH1, highlighting its potential as a more favourable therapeutic candidate compared to these flavonoids.

Cell proliferation assay

Those mentioned above in the in-silico study, followed by the fluorescence binding study and inhibition study, clearly established the efficient binding and significant inhibition of MTH1 by compound RV. Given the reported overexpression of MTH1 in various cancers10–17,22–33, the inhibitory potential of RV on cancer cell progression was studied. All the cell-based studies were conducted on the MCF 7 cell line, as the overexpression of MTH1 is widely reported in breast cancer18–20,71. To evaluate the cytotoxic effects of compound RV, an MTT assay was used where MCF 7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with compound RV in a concentration-dependent manner, i.e., increasing dose from 0 to 200 µM of RV for about 72 h. Compared to the HEK control and MDA-MB-231, the MTT assay revealed significant inhibition in the proliferation rate of MCF7 cells. The IC50 value of RV was calculated using the cell growth curve to be 28.5 ± 1.07 µM for MCF-7 cell Lines, whereas it was 47.29 ± 0.36 µM for MDA-MB-231 cell lines (Fig. 6B). However, these results indicate the cytotoxic effectiveness of compound RV in suppressing the growth of breast cancer cells at micromolar range.

RV treatment resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, however, the effect was more pronounced in MCF-7 cells, as indicated by a significantly lower IC₅₀ value compared to MDA-MB-231, suggesting greater sensitivity of MCF-7 cells to RV-induced cytotoxicity. Since the IC50 value for MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly higher than that observed with MCF7 cells, we decided to focus on MCF7 for the subsequent cell-based assays. This decision was made to ensure more meaningful and consistent results in evaluating the effects of MTH1 inhibition. However, other breast cancer cell lines like MDA-MB-231, being more aggressive and potentially exhibiting higher MTH1 expression, could provide valuable insights into the role of MTH1 in more invasive forms of breast cancer. We suggest that this cell line can be utilized in future studies to expand our understanding of MTH1 inhibition in aggressive cancer types. Our findings indicate that the compound RV has the potential to inhibit the proliferation of cancerous cells and resonate with the previous reports of cytotoxicity of RV on similar or other cancer cells50,51,72,73. The IC50 data for RV as an MTH1 inhibitor, determined to be 18.13 µM, plays a crucial role in its potential repurposing for therapeutic applications. This data establishes a benchmark for inhibitory potency of RV against MTH1, providing a foundation for optimizing its efficacy through structural modifications.

The moderate IC50 value indicates that while RV demonstrates significant inhibitory activity, further refinement could enhance its specificity and potency. Additionally, the IC50 value positions RV as a promising candidate for combination therapies, where its natural origin and ability to induce oxidative stress could complement existing treatments. This approach might reduce the side effects associated with synthetic inhibitors while maintaining or enhancing therapeutic outcomes. The IC50 data also highlights RV’s potential utility in mitigating non-genetic drug resistance mechanisms in cancers, as inhibiting MTH1 disrupts cancer cell survival pathways reliant on this enzyme. Consequently, the inhibitory capacity of RV opens avenues for repurposing it as part of precision medicine approaches targeting MTH1-dependent cancer phenotypes.

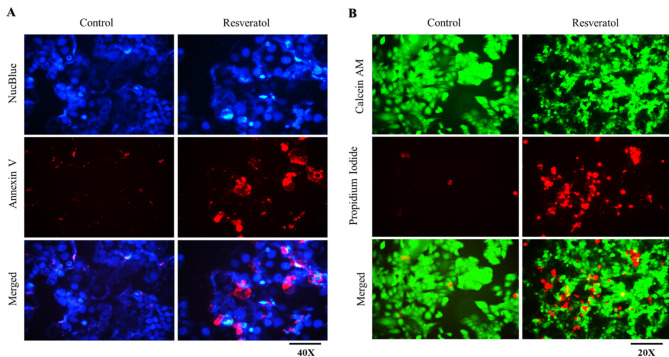

Cell viability and apoptosis assay

Apoptosis serves as a crucial mechanism for regulating and controlling abnormal cell growth. Nonetheless, cancer cells can elude the apoptotic process. Prior research has documented that inhibition of MTH1 leads to apoptosis in various cancer cells23,35,74. On the same line, we investigate apoptotic potential of RV on MCF7 cells. MCF7 cells were treated with an IC50 dose of RV for 72 h and analysed using annexin-V staining. The results showed that RV induces apoptosis in MCF7 cells, which can be visualized from increased red signals of Annexin V-positive apoptotic cells compared to its DMSO control (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

MTH1 inhibition by RV induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were given the IC50 dose of RV for 72 h. (A) Apoptosis was assessed using Annexin V staining. (B) Calcein-AM/PI double staining was carried out to visualize live and dead cells directly.

Similarly, Calcein-AM/PI double staining was used to validate the apoptotic potential of RV, where live cells were stained green by calcein, and red PI-stained dead cells. The compound RV significantly inhibited the cell growth and cell division of MCF7 cells, as observed by a notable increase in PI-positive dead cells compared to its DMSO control (Fig. 7B). Hence, the results from cell viability and apoptosis investigations suggest that RV effectively inhibits the proliferation of MCF7 cancer cells and triggers apoptosis.

Assessment of DNA damage

To evaluate DNA damage induced upon RV treatment, we performed immunofluorescence staining for two well-established markers of double-strand breaks, namely γH2AX and 53BP1, after 48 h of treatment. Compared to the untreated control, RV-treated cells exhibited a marked increase in punctate nuclear foci of both γH2AX and 53BP1, indicating accumulation of DNA damage (Fig. 8). In particular, the signal intensity and number of 53BP1 foci were significantly elevated in treated cells, as quantified by fluorescence intensity analysis. These observations confirm that RV induces DNA damage, potentially contributing to its cytotoxic effects. The co-localization and upregulation of γH2AX and 53BP1 further suggest activation of the DNA damage response pathway.

Fig. 8.

Effect of RV on DNA damage. Immunofluorescence of (A) γ-H2AX and (B) 53BP1 following RV treatment for 48 h shows that DNA damage has significantly increased following the treatment. The right panel shows the quantification of (C) γ-H2AX and (D) 53BP1 signal intensity, represented as mean fluorescence intensity ± SEM. A significant increase in γ-H2AX and 53BP1 intensity was observed upon RV treatment, confirming activation of the DNA damage response (two-tailed p < 0.0001), scale bars: 10 μm.

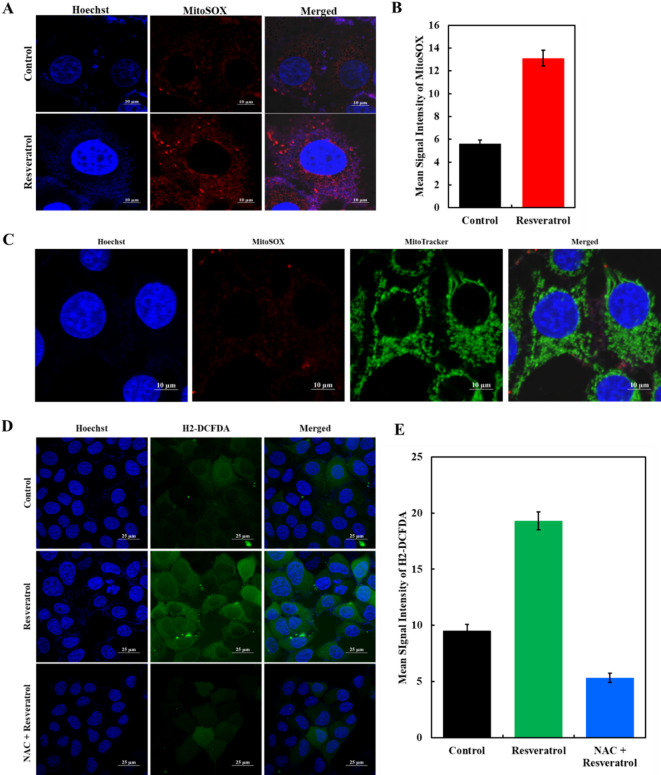

Detection of cellular and mitochondrial ROS

In multiple cancer types, the proposed mechanism of toxicity for drugs involves inducing oxidative stress, which aims to hinder the growth of malignant cells.

The primary source of ROS is the mitochondrial respiratory cycle, which can initiate cell apoptosis. Hence, RV-induced mitochondrial ROS production was studied via MitoSOXTM Red (Invitrogen) staining. The MCF7 cells underwent RV treatment (IC50 dose) for about 3 h and were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope. The results showed a notable enhancement of red fluorescence intensity, which indicates an elevation in ROS levels in RV-treated MCF7 cells compared to DMSO control (Fig. 9A).

Fig. 9.

Effect of RV on ROS production. (A) Representative images of MCF-7 cells stained with MitoSOXTM dye were captured using a fluorescence microscope. The images evaluated ROS levels after RV treatment with red color intensity reflecting the extent of ROS presence. (B) Histogram showing the mean signal intensity of MitoSOX measured by ImageJ shows a significant increase upon RV treatment compared to control (two-tailed p < 0.0001). (C) MitoSOX/Mitotracker experiment where MitoSOX signal is coinciding with the mitoTracker signal, suggesting that the ROS is primarily generated through the mitochondria. (D) H2-DCFDA staining showing elevated levels of general intracellular ROS upon RV treatment. Co-treatment with the ROS scavenger NAC reduced the signal intensity. (E) Quantitative analysis of H2-DCFDA fluorescence is shown. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed t-test (p < 0.0001 for RV vs. NAC + RV). Scale bars are indicated in each image.

To support the fluorescence study, the levels of ROS were quantified by measuring the mean signal intensity during mitosis using ImageJ. The histogram representation of ROS quantification is given in Fig. 9B. The figure depicts a rightward shift in the histogram, which shows a significant increase in ROS production in RV-treated MCF7 cells (24.75) compared to normal HEK cells (13.21). To confirm the mitochondrial source of ROS following RV treatment, cells were stained with MitoSOX Red and MitoTracker Green. High-resolution imaging showed strong colocalization of MitoSOX with MitoTracker, indicating that superoxide generation was localized within mitochondria (Fig. 9C). This validates the mitochondrial origin of ROS and suggests that RV induces oxidative stress through mitochondrial dysfunction. Therefore, the findings from ROS measurements strongly recommend that the RV treatment results in a significant rise in ROS levels in MCF7 cancer cells, which may contribute to cancer cell death. The proposed mechanism by which RV modulates oxidative stress in breast cancer cells is primarily through the inhibition of MTH1. This key enzyme protects cancer cells from oxidative damage by hydrolyzing oxidized dNTPs. By inhibiting MTH1, RV increases the incorporation of oxidized nucleotides into DNA, leading to DNA damage, impaired replication, and apoptosis in cancer cells.

We have also evaluated the effect of RV on intracellular ROS levels by performing H2-DCFDA staining. Cells treated with RV showed a marked increase in green fluorescence intensity, indicating elevated ROS production compared to the untreated control (Fig. 9D). Quantitative analysis further confirmed a significant rise in mean fluorescence intensity upon RV treatment (Fig. 9E). Significantly, co-treatment with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) attenuated this increase, restoring ROS levels close to baseline. These findings suggest that RV induces oxidative stress, which can be effectively reversed by ROS scavenging, implicating ROS as a mediator of the cellular effects of RV. Additionally, RV is known to exhibit antioxidant properties, which may contribute to modulating oxidative stress indirectly through pathways such as ROS generation and modulation of redox-sensitive signaling cascades (e.g., Nrf2/Keap1). However, in the context of our study, the observed effects on oxidative stress and cell viability are strongly linked to the direct inhibition of MTH1 by RV, as confirmed by enzymatic assays and molecular docking studies.

Discussion

Cancer involves widespread disruptions in redox regulation, which is crucial for its development and spread. ROS cause oxidative DNA damage, particularly to the nucleotide pool, resulting in various oxidized nucleotides. The MTH1 protein is vital for maintaining the integrity of the oxidized dNTP pool, preventing their incorporation into DNA and averting genome instability and cell death. Several studies conducted on different types of cancers, such as lung cancer11–13,75brain tumour14,16kidney cancer76,77breast cancer18colorectal cancer10,24,78pancreatic cancer11,27,79gastric cancer22,23multiple myeloma33,80oesophageal cancer81psoriasis25 etc., have reported the elevated levels of MTH1 expression. High MTH1 levels are linked to advanced cancer stages and poorer outcomes, suggesting its involvement in cancer aggressiveness. Normal cells operate effectively without elevated MTH1 levels, which implies a potential target for cancer treatment37. Targeting MTH1 selectively in cancer cells could be a promising therapeutic approach, minimizing harm to normal cells.

Breast cancer is a global health concern, with millions of new cases yearly. Despite advances in detection and treatment, it continues to be a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide82. Conventionally, oncogenic genes are targeted in cancer, but recent challenges like tumor heterogeneity and complexities in signaling crosstalk limit its effectiveness. Hence, targeting non-oncogenic proteins essential for cancer progression but not essential in normal cells is emerging as a more promising therapeutic target. The human MTH1 protein is a well-established target for this approach18.

Also, chemotherapy, while being effective, often causes severe side effects and drug resistance. Addressing this concern, natural substances and phytochemicals are being explored as alternatives to synthetic drugs, which reduce side effects and increase the efficiency of treatment outcomes. This encouraged us to investigate RV, a non-flavonoid polyphenol, as a potential and effective inhibitor of MTH1. RV is widely known nutraceutical for its multifaceted benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, anticancer, antidiabetic, and antiaging activities43,48 via inhibiting STAT3/SOCS-145, NAF-146, SIRT1/p38MAPK, and NO/DLC1[48] signaling pathways.

A detailed analysis of RV biological and physicochemical properties was done via PASS (Table 1) and Swiss ADME (Table 2). Although RV is widely recognized for its antioxidant and cytoprotective roles, especially in normal cells, emerging evidence suggests its paradoxical, pro-oxidant behavior in cancer cells83,8485. This selective cytotoxicity is linked to the disrupted redox balance in tumors, making RV a promising candidate for targeting redox-dependent vulnerabilities such as MTH1. Our findings further support this context-specific pro-oxidant effect, reinforcing its therapeutic potential in cancer.

In the present study, we have expressed and purified the MTH1 protein to explore the inhibitory potential of RV. The initial screening was conducted with in silico evaluation, where docking studies revealed a good binding affinity and significant ligand efficiency of RV with MTH1, followed by detailed interaction analysis (Table 3). The interaction analysis revealed that RV formed a substantial number of covalent bonds with the crucial residues of the MTH1 binding pocket, including the active site, indicating that RV binds to the active site, which is responsible for its catalytic activity. Hence, RV could be addressed as a competitive inhibitor of MTH1, inhibiting the enzyme’s functional activity. The MTH1-RV docked complex (Fig. 1) illustrated that RV occupied the deep substrate binding pocket of MTH1. The binding of RV can induce notable alterations in the protein structure of MTH1. Hence, to understand the mechanical aspects of MTH1 stability, conformational changes, and interactions upon RV binding, an MD simulation was conducted for 200ns.

The conducted MD simulations showed that MTH1 alters only minimally in its interaction with RV, which is evident by the concordant trajectories of RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA, thus suggesting that MTH1 bound to RV is much more stable than the unbound MTH1 (Table 4). Even though a few fluctuations were occasionally seen, no important conformational alterations were perceived during the entire simulation (Fig. 2). This analysis highlights the robust stability of MTH1 following binding with RV (Fig. 3). Furthermore, even PCA analysis supported the same, whose findings reveal that despite the MTH1 bound to RV showing some variability in the flexibility of structure as opposed to the free MTH1, it does not surpass the number of eigenvectors (EVs) engaged by the unbound protein (Fig. 4A). Likewise, FEL analysis suggests that the binding of MTH1 does not lead to protein unfolding in the 200ns simulation period (Fig. 4B). All these results imply that RV stably interacts with MTH1 and causes little alterations in its configuration. Hence, it might prove to be a possible anticancer drug.

To validate the in-silico evaluation, fluorescence binding studies and in vitro studies with cell-free and cell-based enzyme assays were conducted. The fluorescence measurement exhibited a strong binding affinity of RV to MTH1 in the range of 6.2 × 105 M-1 (Fig. 5). The binding of RV to MTH1 was responsible for inhibiting its functional activity, which was assessed via enzyme inhibition in a malachite-based assay. The IC50 value obtained was 18.13 ± 1.08 µM, which clearly manifests the effectiveness of RV in suppressing the enzymatic activity of MTH1 at the micromolar range (Fig. 6A). Given the reported overexpression of MTH1 in various cancers10–17,22–33, the inhibitory potential of RV on cancer cell progression was studied. The MCF7 cell line was used for all the cell-based biological assays due to the well-established expression of MTH1 in breast cancer18–20,71.

The inhibitory effects of RV on the proliferation of breast cancer cells were analyzed via MTT assay. The breast cancer cell lines, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, were considered while performing calorimetric MTT assay and HEK as a control. The findings of the cell proliferation assay suggested that the compound RV significantly inhibited the growth of MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines with IC50 values of 28.5 ± 1.07 µM and 47.29 ± 0.36 µM, respectively (Fig. 6B). Considering the preliminary findings from enzyme activity, binding, and cell proliferation experiments, we propose that the investigated phytochemical RV shows potential as a promising candidate for anti-cancer compounds.

Since the hallmark of cancer cells lies in their uncontrolled proliferation, migration, invasiveness, and ability to evade apoptotic signals, we sought to investigate the impact of RV on apoptotic cell death by conducting annexin-V staining. The result shows a notable increase in the number of cells undergoing apoptosis in MCF7 cell lines, which are visible in red (Fig. 7A). This indicates that RV was inhibiting the proliferation of MCF7 cancer cells. The calcein AM/PI staining assay further supported the apoptosis findings, which revealed RV-induced cell death in MCF7 cells compared to the vehicle control (Fig. 7B). There was a significant enhancement in the number of dead cells compared to the control. Both studies elucidate that RV can potentially exert a considerable influence on curbing the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells. The interpretation of our results, indicating that MTH1 inhibition leads to apoptosis, aligns with previous studies conducted on gastric cancer cells and breast cancer cells52.

The MTT assay showed a significant reduction in cell viability following treatment, which initially suggested potential inhibition of cell proliferation and/or cytotoxicity. However, based on our apoptosis assays demonstrating increased Annexin V-positive cells and calcein AM/PI-stained cells, the observed decrease in MTT signal is more likely attributable to apoptosis-mediated cytotoxicity rather than solely an anti-proliferative effect. While apoptosis induction was qualitatively observed, quantitative evaluation of apoptotic markers was not performed in the current study, which we recognize as a limitation to be addressed in future investigations.

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a significant increase in γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci following 48 h of RV treatment, indicating enhanced DNA damage. Quantification of fluorescence intensity further confirmed activation of the DNA damage response (Fig. 8). These results suggest that RV induces genotoxic stress, contributing to its antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cells. The study also dealt with evaluating and rationalizing ROS levels under the impact of RV. Cancer cells are notably affected by ROS, whose increased levels result in oxidative stress. The accumulation of ROS stimulates critical pro-apoptotic pathways, including endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial malfunction. This leads to derangement of cellular functions and ultimately results in apoptosis. Considering that mitochondria are the chief producers of ROS, we assessed the ROS production by the mitochondria using MitoSOXTM Red staining (Fig. 9A, B & C). We found that RV substantially increased ROS production in MCF7 cells, which positions the cancer cells under significant oxidative stress.

Additionally, H2-DCFDA staining shows elevated levels of general intracellular ROS upon RV treatment and Co-treatment with the ROS scavenger NAC reduced the signal intensity (Fig. 9D & E). This finally results in the death of the cancer cells. From the perspective of its chemical structure, RV is an ideal MTH1 inhibitor due to its polyphenolic cores comprising three hydroxyl groups and a stilbene backbone, which allows for multiple hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions with active site residues of MTH1, stabilizing the inhibitor-enzyme complex. Also, its molecular weight (228.24 g/mol) and lipophilicity (LogP = 2.48) align well with drug-likeness criteria, ensuring adequate bioavailability and efficient enzyme binding. Its specificity to the active site is demonstrated by its effective binding within the substrate pocket of MTH1, where it interacts with key residues such as Asp120 and Asn33. These residues are critical for the enzyme catalytic activity and substrate specificity, establishing RV as a competitive inhibitor.

MTH1 plays a dual role in cancer progression by preventing oxidative damage to DNA and supporting cancer cell survival under high oxidative stress conditions, a characteristic common to many cancers. While our study focuses explicitly on breast cancer, the overexpression of MTH1 has been reported in various other cancers, such as lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers. The molecular interactions and inhibitory effects of RV observed in our study suggest that it could be a potential therapeutic agent not only for breast cancer but also for other cancers where MTH1 plays a critical role. However, cancer-specific differences in MTH1 expression levels and oxidative stress mechanisms must be considered when extrapolating the findings to different cancer types.

RV, renowned for its natural origins, presents immediate practical prospects in cancer therapy by targeting MTH1, an essential contributor to cancer advancement. RV demonstrates a strong binding affinity to MTH1, with a binding constant of 6.2 × 105, as evident from fluorescence binding studies. Its ability to form multiple interactions with the active site residues of MTH1 such as Gly36, Asp119, and Trp117, ensures effective inhibition of its enzymatic activity. RV possesses multifunctionality properties as its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties are well-documented. It acts on multiple pathways such as STAT3/SOCS-1 and SIRT1/p38MAPK, providing broader therapeutic effects while minimizing side effects. RV was also found to have pharmacokinetic advantages as it exhibits high gastrointestinal absorption, is BBB permeant, and is not a substrate for P-glycoprotein, making it suitable for systemic delivery and targeting Tumours effectively. With a synthetic accessibility score of 2.02, RV is relatively easy to produce compared to other complex natural compounds.

However, the solubility of RV (log S: ESOL = 3.62; Ali = 4.07) may limit its bioavailability at higher doses. Its low molecular weight (228.24 g/mol) and a “lead-likeness” violation suggest limited structural complexity for optimization. Its inhibition of CYP enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4) raises concerns about drug-drug interactions, off-target effects, and rapid metabolism, potentially reducing its plasma half-life. The Brenk alert for its stilbene structure also indicates possible toxicological liabilities. Also, since RV belong to naturally occurring dietary phytochemicals, they lack specificity in their targeting mechanisms. This study provides a novel scaffold of RV that could be utilized further with appropriate structural modifications for the design and development of synthetic derivatives. We believe that the scaffold of RV strongly interacts with the substrate binding pocket of MTH1 and hence, further modifications in the scaffold can generate more efficacious and specific derivatives as MTH1 inhibitors. RV holds promise for targeted therapy, combination treatments, and chemoprevention in breast cancer.

While this study primarily focuses on in-silico, biophysical, and in-vitro assays to establish the potential of RV as an MTH1 inhibitor, we acknowledge the need for further validation in in-vivo models. Our study provides mechanistic insights into how RV interacts with MTH1 at a molecular level, inhibiting its enzymatic activity, which is essential for cancer cell survival under oxidative stress. Additionally, the observed efficacy of RV in breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF7 and MDAMB231) confirms its anti-cancer potential in vitro, laying the groundwork for in vivo studies. The future studies will validate the efficacy of RV in breast cancer models, focusing on tumour growth inhibition, pharmacokinetics, and its ability to target MTH1 while minimizing toxicity in normal tissues. Additionally, comprehensive toxicity assessments are required to evaluate the safety profile of RV for long-term use in breast cancer treatment.

Also, a more comprehensive profiling of RV binding targets and off-target effects, particularly in in-vivo models, is needed in future studies to ensure its specificity and safety for therapeutic use. Additional research, encompassing in vivo experiments and clinical trials, is necessary to fully leverage the therapeutic potential of RV. The future entails thorough clinical validation, refining therapeutic approaches via precision medicine, elucidating molecular mechanisms, investigating synergies with other compounds, and evaluating long-term patient outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we effectively purified the human MTH1 protein and then evaluated the phytochemical compound RV as a potent inhibitor of MTH1. The in-silico evaluation established strong binding of RV to MTH1 in the substrate binding pocket, where RV formed several strong interactions with active site residues of MTH1. Molecular dynamics simulations showed that the MTH1-RV complex remained highly stable, with minute structural variations observed in the RMSD and RMSF plots. The in-silico study was further validated by fluorescence measurement, where RV exhibited high binding affinity to MTH1. This binding of RV leads to the inhibition of the functional activity of MTH1, as evident by inhibition analysis. The inhibitory potential of RV was studied via various biological assays, affirming the anti-proliferative and cytotoxic nature of breast cancer cells. In summary, our results strongly suggest that RV holds great potential as an inhibitor of MTH1. These findings could serve as crucial scaffold derivatives for developing highly effective and selective molecules targeting MTH1, offering promising avenues for combating cancer progression. Employing this natural compound targeting MTH1 with minimal side effects represents a strategic therapeutic approach for effectively addressing the clinical symptoms of cancer and other human pathologies associated with MTH1.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

MIH thanks the Indian Council of Medical Research for financial support (Grant No. ECD/adoc/2/2021-22). The authors extend their appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-122), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this research. AT thanks PMRF for awarding a Prime Minister Research fellow (F.No.4 L-1l2018-TS-1). A.S. is grateful to Ajman University, UAE, for supporting the publication.

Abbreviations

- MTH1

MutT Homolog 1

- RV

Resveratrol

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- FEL

Free Energy Landscape

- MD

Molecular Dynamics

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- Rg

Radius of Gyration

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- RMSF

Root mean square fluctuation

- SASA

Solvent Accessible Surface Area

Author contributions

Aaliya Taiyab: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation; Arunabh Chaudhary: Data curation, Graphics, Data validation; Shaista Haider: Methodology, Data validation, Writing-review, and editing; Aanchal Rathi: Graphics, Data validation, Writing-review, and editing; Afzal Hussain: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition; Mohamed F. Alajmi: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing; Anindita Chakrabarty: Data curation, Graphics, Data validation; Faez Iqbal Khan: Methodology, Data validation, Writing-review, and editing; Anas Shamsi: Data curation, Graphics, Data validation, Supervision; Md. Imtaiyaz Hassan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Review and editing, and project administration.

Funding

The Indian Council of Medical Research funded this work (Grant No. ECD/adoc/2/2021-22). This research has been funded by the Department of Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Prime Minister Research Fellowship (PMRF) (F.No.4 L-1l2018-TS-1). Ongoing Research Funding program Project Number (ORF-2025-122), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anas Shamsi, Email: anas.shamsi18@gmail.com.

Md. Imtaiyaz Hassan, Email: mihassan@jmi.ac.in.

References

- 1.Cheung, E. C. & Vousden, K. H. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 22, 280–297 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gad, H. et al. MTH1 Inhibition eradicates cancer by preventing sanitation of the dNTP pool. Nature508, 215–221 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes, J. D., Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. & Tew, K. D. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell.38, 167–197 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perillo, B. et al. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the Moon. Exp. Mol. Med.52, 192–203 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samaranayake, G. J., Huynh, M. & Rai, P. MTH1 as a chemotherapeutic target: the elephant in the room. Cancers9, 47 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin, Y. & Chen, F. Targeting human mutt homolog 1 (MTH1) for cancer eradication: current progress and perspectives. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. 10, 2259–2271. 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.012 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kettle, J. G. et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of MTH1 probe its role in cancer cell survival. J. Med. Chem.59, 2346–2361. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01760 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, Y. et al. Enhancing repair of oxidative DNA damage with small-molecule activators of MTH1. ACS Chem. Biol.17, 2074–2087 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakabeppu, Y. Molecular genetics and structural biology of human mutt homolog, MTH1. Mutat. Research/Fundamental Mol. Mech. Mutagen.477, 59–70. 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00096-3 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bialkowski, K. & Szpila, A. Specific 8-oxo-dGTPase activity of MTH1 (NUDT1) protein as a quantitative marker and prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med.176, 257–264 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson, L. A. et al. Increased MTH1-specific 8-oxodGTPase activity is a hallmark of cancer in colon, lung and pancreatic tissue. DNA Repair.83, 102644 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, D. N. et al. The high expression of MTH1 and NUDT5 promotes tumor metastasis and indicates a poor prognosis in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell. Res.1868, 118895 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel, A. et al. MutT homolog 1 (MTH1) maintains multiple KRAS-driven pro-malignant pathways. Oncogene34, 2586–2596 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tu, Y. et al. Birth of MTH1 as a therapeutic target for glioblastoma: MTH1 is indispensable for gliomatumorigenesis. Am. J. Translational Res.8, 2803 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pudelko, L. et al. Glioblastoma and glioblastoma stem cells are dependent on functional MTH1. Oncotarget8, 84671 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmer, M., Kuhl, S. & Goldbrunner, R. BIOM-01: MTH1 Expression is upregulated in brain metastases of malignant melanoma. Neuro-Oncology23, vi9–vi10 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karsten, S. et al. MTH1 as a target to alleviate T cell driven diseases by selective suppression of activated T cells. Cell. Death Differ.29, 246–261 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang, X. et al. Expression and function of mutt homolog 1 in distinct subtypes of breast cancer. Oncol. Lett.13, 2161–2168 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, X. et al. LncRNA AFAP1-AS1 promotes triple negative breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion via targeting miR-145 to regulate MTH1 expression. Sci. Rep.10, 7662 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, J. et al. MTH1 suppression enhances the stemness of MCF7 through upregulation of STAT3. Free Radic. Biol. Med.188, 447–458 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, N. et al. Targeting mutt homolog 1 (MTH1) for breast cancer suppression by a novel MTH1 inhibitor MA-24 with tumor-selective toxicity (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhou, W. et al. Potent and specific MTH1 inhibitors targeting gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis.10, 434 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhan, D. et al. MTH1 inhibitor TH287 suppresses gastric cancer development through the regulation of PI3K/AKT signaling. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm.35, 223–232 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumagae, Y. et al. Overexpression of MTH1 and OGG1 proteins in ulcerative colitis–associated carcinogenesis. Oncol. Lett.16, 1765–1776 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eding, C. B. et al. MTH1 inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis. J. Invest. Dermatology. 141, 2037–2048 (2021). e2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karsten, S. Targeting the DNA repair enzymes MTH1 and OGG1 as a novel approach to treat inflammatory diseases. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol.131, 95–103 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikejiri, F., Honma, Y., Kasukabe, T., Urano, T. & Suzumiya, J. TH588, an MTH1 inhibitor, enhances phenethyl isothiocyanate–induced growth Inhibition in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Lett.15, 3240–3244 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateo-Victoriano, B. et al. Abstract B091: the mammalian 8-oxodGTPase, MTH1, as a novel targetable vulnerability in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res.84, B091–B091 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, X. et al. Synergistic therapy of chemotherapeutic drugs and MTH1 inhibitors using a pH-sensitive polymeric delivery system for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biomaterials Sci.5, 2068–2078 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi, X. L., Li, Y., Zhao, L. M., Su, L. W. & Ding, G. Delivery of MTH1 inhibitor (TH287) and MDR1 SiRNA via hyaluronic acid-based mesoporous silica nanoparticles for oral cancers treatment. Colloids Surf., B. 173, 599–606 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding, Y. et al. MTH1 protects platelet mitochondria from oxidative damage and regulates platelet function and thrombosis. Nat. Commun.14, 4829 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]