Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate efficacy and safety of telitacicept in IgA nephropathy (IgAN) in a real-world setting.

Methods

This study is a retrospective, single-center study that included 33 IgAN patients from Xin Hua Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Eleven patients received telitacicept treatment for at least 3 months. A control group was matched using propensity score matching. Clinical assessments and laboratory tests were performed at baseline and subsequently every one to three months during the treatment period. Clinical outcomes were assessed at 3 and 6 months.

Results

At 3 months, 24-hour urinary protein in the telitacicept group decreased by 893.29 mg/day (63.90%). The telitacicept group achieved a complete remission rate of 36.36% and a partial remission rate of 36.36%. Similarly, the control group exhibited a complete remission rate of 31.82% and a partial remission rate of 36.36%. At 6 months, although the telitacicept group showed lower 24-hour urinary protein than the control group, the difference was not statistically significant [381.68 (182.52–990.00) mg/day vs. 480.15 (185.28–905.15) mg/day, P = 0.567]. Complete remission rates for the telitacicept and control groups increased to 54.55% and 36.36%, with overall remission rates of 72.73% and 77.27%, respectively. Serum creatinine and eGFR remained stable throughout the study. The most common adverse reactions were pain, redness, or itching at injection site, without signs of local infection.

Conclusion

Preliminary clinical trials have provided supportive evidence for the efficacy and safety of telitacicept as a viable treatment option for IgAN.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12882-025-04468-7.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, Immunoglobulin A, Propensity score matching, Proteinuria, Telitacicept

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is one of the most common primary glomerulonephritis in East Asia, characterized by an autoimmune response to abnormally glycosylated IgA antibodies. IgAN was initially considered a benign disease. However, current epidemiological evidence indicates that approximately 20–35% of patients with overt proteinuria and/or elevated serum creatinine levels will gradually progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 20 to 30 years of diagnosis [1, 2]. With advancing understanding of the pathogenesis of IgAN, commonly framed by the widely accepted “four-hit hypothesis”, the disease is now firmly recognized as an autoimmune disorder.

Current treatments for IgAN include renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi) and relatively newer options such as sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and endothelin receptor antagonists, none of which target the early steps of IgAN pathogenesis. Although supportive therapy is beneficial, it cannot prevent the formation and deposition of immune complexes in the glomerular mesangium, leading to inflammation and progressive kidney damage. Studies suggest that corticosteroid therapy likely prevents progression to ESKD compared with placebo or standard care [3, 4]. However, some patients may experience intolerable adverse effects, including severe or even fetal pulmonary infections. Recent studies on immunotherapy for IgAN have been increasing, and Nefecon, a novel oral targeted-release capsule formulation of budesonide, has been approval for the treatment of IgAN [5]. It is designed to act on the distal ileum, which is rich in gut-associated lymphoid tissue, to reduce the production of excess circulating galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1), a key process in the four-hit hypothesis.

Telitacicept, a fusion protein combining a recombinant transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor receptor with an immunoglobulin framework, represents a novel therapeutic approach by concurrently targeting B-Lymphocyte Stimulator (BlyS)/B-cell-activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) [6]. BAFF and APRIL are both involved in mucosal B cell survival, maturation, proliferation, and IgA class switching in B cells, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of disorders with aberrant immunoglobulin production [7, 8]. Levels of serum BAFF and APRIL were increased in patients with IgAN and were associated with clinical and pathological features of the disease [9, 10]. These results suggest that BAFF and APRIL have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets in the treatment of IgAN. In a phase II clinical trial, 44 IgAN patients were randomized to receive either placebo, 160 mg, or 240 mg of telitacicept through weekly subcutaneous injections. Following a period of 6 months, it was observed that the administration of 240 mg telitacicept led to a substantial reduction of proteinuria by 49% and the administration of 160 mg telitacicept led to a reduction of proteinuria by 25% [11]. Telitacicept also reduced levels of circulating Gd-IgA1 and IgA-containing immune complexes, which are critical components in the pathophysiology of IgAN [12]. Telitacicept is undergoing phase III clinical development in China (NCT05799287). However, studies on the real-world application of telitacicept in IgAN are still limited. This study aims to retrospectively assess the clinical outcomes associated with telitacicept in IgAN patients.

Methods

Study design and patients

This retrospective analysis reviewed data from IgAN patients treated at the Department of Nephrology, Xin Hua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, between July 2020 and June 2024. Patients included in the study had a confirmed diagnosis of primary IgAN based on renal biopsy. They were divided into the telitacicept or control group according to their treatment regimen. Patients in the telitacicept group received telitacicept for at least 3 months, whereas those in the control group received conventional therapy, including corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants, and enhanced supportive care. Patients with a follow-up period of less than 6 months or missing clinical data were excluded from the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Xin Hua Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. XHEC-C-2023-086-1). Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the identifiable information of the patients was anonymized.

Treatment, follow-up, and assessment

Patients received subcutaneous telitacicept at an initial dose of 160 mg, administered weekly, with adjustments based on disease severity and individual economic considerations. All patients received supportive care, including rigorous blood pressure control, optimal RASi, and lifestyle modifications. Clinicians determined the type and dosage of additional immunotherapies based on disease severity and treatment response. Immunotherapies included glucocorticoids, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide and tripterygium wilfordi. In the control group, corticosteroids were typically initiated at a moderate dose, such as prednisone 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day or an equivalent regimen, followed by gradual tapering according to clinical response and proteinuria levels. Maintenance doses were adjusted based on disease activity, and the total treatment duration generally ranged from 6 to 12 months, depending on individual patient response. In the telitacicept group, corticosteroids were usually initiated at the start of therapy and tapered more rapidly thereafter.

Clinical assessments and laboratory tests were performed at baseline (defined as the last assessment before treatment) and subsequently every one to three months. Comprehensive data encompassing demographic details, disease characteristics, coexisting conditions, current therapies, and laboratory parameters were collected and recorded. Laboratory parameters included serum albumin, serum creatinine, 24-hour urinary protein, serum immunoglobulins and routine urinalysis. The estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) was calculated using the formula from the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) [13]. Disease duration was defined as the interval from the earliest occurrence of either laboratory abnormalities, including proteinuria, hematuria, or elevated serum creatinine, or symptom onset, such as edema or foamy urine, to the initiation of the current treatment. All adverse events encountered during the treatment phase were systematically documented, including infectious, non-infectious, and hypersensitivity reactions.

Clinical outcomes were assessed at 3 and 6 months after treatment. Complete remission (CR) was defined as 24-hour urinary protein levels < 0.3 g/day, with stable creatinine (changes in creatinine ≤ 15% of baseline values) and serum albumin ≥ 35 g/L. Partial remission (PR) was defined as a 50% reduction in 24-hour urinary protein from the baseline value, with stable creatinine and serum albumin ≥ 30 g/L. No response (NR) was defined as 24-hour urinary protein levels > 3.5 g/day, or a reduction of less than 50% from the baseline value, or a doubling of creatinine. Relapse was defined as the reappearance of overt proteinuria, with 24-hour urinary protein levels > 1.0 g/day or an increase of > 50% from the lowest level after remission [14, 15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and graphical representations were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0) and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.1). The normality of continuous variables was performed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as the median (interquartile range). Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used depending on the data distribution. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%), and comparisons were made using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. To minimize potential biases between the telitacicept and control groups, propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted in R software (version 4.3.2) using a 1:2 nearest-neighbor algorithm without replacement. Propensity scores were estimated with a logistic regression model based on variables that showed baseline differences between groups as well as clinically relevant factors potentially influencing treatment efficacy. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using multivariable logistic regression models, adjusting for covariates with residual imbalance after PSM. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess the association between telitacicept treatment and remission outcomes. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

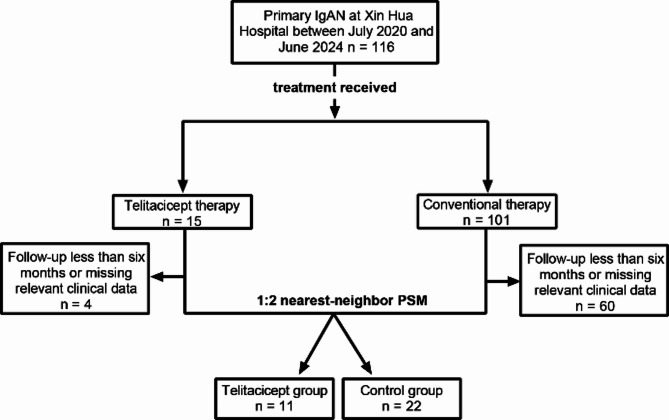

A total of 116 patients with primary IgAN were treated at Xin Hua Hospital between July 2023 and June 2024. After excluding 64 patients due to incomplete data or loss to follow-up, 52 patients were remained, comprising 11 patients in the telitacicept group and 41 in the control group. Baseline demographic and laboratory characteristics before PSM are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Before PSM, patients in the telitacicept group were significantly younger than those in the control group [33.00 (25.00–46.00) vs. 42.00 (37.50–60.00) years, P = 0.030]. To minimize potential confounding effects, PSM was performed using variables including sex, age, BMI, disease duration, 24-hour urinary protein, and serum creatinine. After PSM, the telitacicept group comprised 11 patients, and the control group comprised 22 patients. The patient inclusion process is depicted in Fig. 1. In the telitacicept group, a total of seven females (63.63%) were included. The mean age at disease onset was 35.91 years, with a broad range from 16 to 61 years and the mean duration of disease prior to treatment was 30 months. The median 24-hour urinary protein level was 1244.70 mg. All patients in both groups underwent renal biopsy and were scored according to the Oxford Classification, except for one in the control group, which could not be scored due to an insufficient number of glomeruli obtained during the biopsy, and one in the control group whose detailed biopsy report was missing [16]. Baseline comparisons between telitacicept and control groups are shown in Table 1. No significant statistical differences were observed in demographic and basic clinical characteristics.

Fig. 1.

The patient inclusion process. PSM, propensity score matching

Table 1.

Detailed demographic and baseline clinical characteristics after PSM

| Characteristics | Total (n = 33) |

Telitacicept group (n = 11) |

Control group (n = 22) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.64 ± 11.65 | 35.91 ± 13.48 | 38.50 ± 10.86 | 0.555 |

| Female, n (%) | 22 (66.7) | 7 (63.63) | 15 (68.18) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.20 ± 3.52 | 25.32 ± 3.12 | 25.14 ± 3.77 | 0.896 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 91.67 (87.33–97.33) | 91.33 (89.67–99.33) | 91.83 (86.92–97.00) | 0.939 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 16 (48.48) | 5 (45.45) | 11 (50.00) | 0.805 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (9.09) | 2 (18.18) | 1 (4.55) | 0.252 |

| Disease duration (months) | 21.00 (2.50–43.50) | 30.00 (2.00–51.00) | 16.50 (2.75–52.75) | 0.646 |

| Oxford classification, n | ||||

| M 0/1 | 0/31 | 0/11 | 0/20 | 1.000 |

| E 0/1 | 20/11 | 6/5 | 14/6 | 0.401 |

| S 0/1 | 3/28 | 2/9 | 1/19 | 0.284 |

| T 0/1/2 | 18/8/5 | 7/3/1 | 11/5/4 | 0.634 |

| C 0/1/2 | 19/12 | 7/4 | 12/8 | 0.575 |

| Serum creatinine (umol/L) | 102.60 (74.00–152.00) | 91.00 (76.00–185.00) | 106.50 (63.25–150.50) | 0.849 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 73.31 ± 37.11 | 73.57 ± 40.39 | 73.18 ± 36.36 | 0.978 |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2, n (%) | 14 (42.42) | 4 (36.36) | 10 (45.45) | 0.719 |

| Urinary protein (mg/day) | 1397.85 (916.31–2182.38) | 1244.70 (728.97–2343.25) | 1409.25 (1047.27–1972.45) | 0.620 |

| Urine RBC (/HP) | 7.00 (4.00–15.00) | 7.00 (4.00–22.00) | 6.50 (3.75-15.00) | 0.954 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.33 ± 4.18 | 39.91 ± 5.13 | 37.54 ± 3.47 | 0.126 |

| IgA (g/L) | 3.37 (2.69–3.90) | 3.42 (2.63–5.62) | 3.36 (2.95–3.78) | 0.792 |

Normally distributed data presented as mean ± SD; non-normally distributed data presented as median (interquartile range); the categorical variables were presented as n (%). PSM, propensity score matching, BMI, body mass index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; eGFR, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; RBC, red blood cell; HP, high power field; IgA, immunoglobulin A; SD, standard deviation

Treatment pattern

Six patients in the telitacicept group and five in the control group had previously received immunosuppressive therapy, and underwent retreatment, while the remaining patients were treatment-naïve. By the end of the observation, patients in the telitacicept group had received an average of 36 weeks of telitacicept treatment. The patterns of combination medication in the two groups are shown in Table 2. At the initiation of telitacicept therapy, three (27.27%) patients were concurrently using moderate or low doses of corticosteroids, while two (18.18%) patients were receiving MMF. Unlike the phase II trial, the initial dose of telitacicept in our cohort was 160 mg per week [9]. Following disease remission, eight (72.73%) patients had their dosage reduced to 80 mg per week under the guidance of physician. In the control group, 20 patients (90.91%) received corticosteroids with a mean initial prednisone-equivalent dose of 31.25 mg and a mean treatment duration of 8.05 months. In the telitacicept group, 3 patients (27.27%) received corticosteroids with a mean initial prednisone-equivalent dose of 23.33 mg and a mean treatment duration of 3.33 months. All patients adhered to standard treatment protocols for blood pressure management.

Table 2.

Combination medication

| Treatment | Telitacicept group (n = 11) | Control group (n = 22) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RASi, n (%) | 7 (63.64) | 16 (72.73) | 0.696 |

| SGLT2i, n (%) | 6 (54.55) | 9 (40.91) | 0.458 |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 2 (18.18) | 7 (31.82) | 0.681 |

| immunosuppressants, n (%) | 1 (4.55) | 3 (27.27) | 0.097 |

| Corticosteroids plus immunosuppressants, n (%) | 1 (9.09) | 13 (59.09) | 0.009* |

The categorical variables were presented as n (%). RASi, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil. *P < 0.05

Effectiveness analysis

All participants underwent a 6-month clinical follow-up period. Continuous observation was conducted (Fig. 2). Both the telitacicept and control groups showed significant reductions in 24-hour proteinuria from baseline at 3 and 6 months. In the telitacicept group, mean reductions were 779.25 mg/day at 3 months (P = 0.013) and 831.06 mg/day at 6 months (P = 0.006). In the control group, mean reductions were 794.55 mg/day at 3 months (P = 0.004) and 877.06 mg/day at 6 months (P < 0.001). At 6 months, there was no statistically significant difference in 24-hour urinary protein between the telitacicept and control groups [381.68 (182.52–990.00) mg/day vs. 480.15 (185.28–905.15) mg/day, P = 0.567]. No significant differences were observed in creatinine [91.00 (75.00–130.00) umol/L vs. 106.00 (65.00–121.50) umol/L, P = 0.879] or eGFR (78.34 ± 34.52 ml/min/1.73m2 vs. 76.79 ± 33.88 ml/min/1.73m2, P = 0.903) between two groups.

Fig. 2.

Continuous observation. (A) 24-hour urinary protein; (B) Serum creatinine; (C) eGFR. Error bars indicate standard errors. eGFR, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

At 3 months, the telitacicept group achieved a complete remission rate of 36.36% and a partial remission rate of 36.36%. Similarly, the control group exhibited a complete remission rate of 31.82% and a partial remission rate of 36.36%. By 6 months, the complete remission rates increased to 54.55% in the telitacicept group and 36.36% in the control group (P = 0.459), with overall remission rates of 72.73% and 77.27% (P = 1.000), respectively. At the final follow-up, only one patient in the telitacicept group experienced a relapse after 8-month treatment. The patient continued telitacicept therapy, which led to subsequent disease remission.

Discontinuation and safety

Of the 11 IgAN patients treated with telitacicept, four (36.36%) continued treatment until the end of the follow-up period, while seven (63.64%) discontinued telitacicept after a median treatment duration of 34.26 weeks. Five patients discontinued due to complete remission and two due to insufficient efficacy, and all seven were included in the 6-month evaluation. The most commonly reported adverse reactions were injection site pain, redness, or itching, without signs of local infection. These symptoms were reported by five patients and generally resolved spontaneously within two to three days. Two patients had upper respiratory infections during treatment. One patient paused telitacicept due to an upper respiratory tract infection, but resumed treatment successfully after recovery, while the other did not discontinue treatment.

Sensitivity analysis

The standardized mean differences (SMD) for all covariates before and after matching were presented in Supplementary Table 2. After matching, most variables achieved good balance (absolute SMD < 0.2), but a few variables, including age, diabetes proportion, albumin, and IgA, remained imbalanced. To assess the robustness, a sensitivity analysis was performed. Covariates that remained imbalanced after PSM (absolute SMD > 0.2) were included as additional adjustment factors in multivariable regression models. Using this adjusted model, we re-analyzed the overall and complete remission rates at 6 months in patients with IgAN. The results showed that telitacicept treatment was not significantly associated with either overall remission (OR = 3.88, 95% CI: 0.39–38.55, P = 0.247) or complete remission (OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 0.19–8.55, P = 0.796) at 6 months, indicating that the conclusions of the original matched analysis were robust.

Discussion

In this real-world retrospective study, we found that compared to traditional treatment, telitacicept combined with standard supportive therapy may have a comparable effect in reducing proteinuria in patients with IgAN. Telitacicept significantly reduced proteinuria in IgAN patients while maintaining stable serum creatinine and eGFR throughout the follow-up period, with no severe adverse events observed. PSM analysis revealed no significant differences in mid- to short-term outcomes, although complete remission rates were higher with telitacicept (54.55% vs. 36.36% at 6 months) without reaching statistical significance. While not demonstrating superior efficacy, the study provides meaningful non-inferiority evidence and suggests telitacicept may be a viable option for patients who are intolerant, resistant, or refractory to corticosteroids, or who have contraindications.

The primary goal in the treatment of IgAN is to prevent progression to ESKD. Previous studies had demonstrated that a reduction in proteinuria was associated with a lower risk of progression to ESKD in IgAN patients [17]. Proteinuria reduction can serve as a potential surrogate endpoint for slowing kidney disease progression in IgAN treatment. Current therapeutic strategies mainly focus on optimizing supportive care. While immunosuppressive therapy can improve outcomes, its significant toxicity limits its use to high-risk patients who remain at risk of progression to ESKD despite receiving optimal supportive care. Recent studies showed that telitacicept effectively reduced proteinuria and serum IgA levels. These findings support the early initiation of therapies targeting IgA and IgA immune complexes, aiming to control disease activity at the underlying pathogenesis rather than emphasizing a 3-month period of optimized supportive observation. PSM enabled us to construct a control group in the absence of conditions for randomized controlled trials, thereby mitigating the impact of confounding variables on study outcomes and optimizing the use of experimental group samples. However, it is important to acknowledge that the inclusion of all potential confounding variables cannot be guaranteed.

There is no consensus on the optimal dose of telitacicept for the treatment of IgAN. The recommended dose for systemic lupus erythematosus is 160 mg per week. In a phase II clinical trial, telitacicept exhibited a dose-dependent anti-proteinuria effect, with administration of 240 mg resulting in a significant decrease in proteinuria. The pharmacokinetic study of telitacicept suggested that it exhibited dosing and accumulation effects [18]. However, in our study, patients initially received a starting dose of 160 mg per week, with 72.73% subsequently tapering to a lower dose of 80 mg per week, yet they still achieved significant reductions in proteinuria. Considering the balance between cost-effectiveness and the potential risks associated with excessive immunosuppression, we propose that reducing the dosage of telitacicept, combined with close monitoring, may be a feasible therapeutic strategy. This result is consistent with findings from a multicenter retrospective study [19]. However, well-designed clinical trials are still needed to evaluate the efficacy of the 80 mg weekly dose telitacicept. Unlike the previous phase II clinical trial, this study is a real-world investigation that included patients treated with either immunosuppressants or systemic corticosteroids. This multi-targeted therapeutic approach may increasingly gain favor among clinicians.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small, follow-up was short, and post-treatment IgA and Gd-IgA data were incomplete. Second, racial differences may have influenced the results, as Asian patients have a higher risk of acute injury and poorer renal outcomes compared with Caucasians [20]. Third, cost-effectiveness was not evaluated. Additionally, treatment regimens in this real-world study may not have been fully standardized, potentially introducing residual confounding despite PSM and sensitivity analyses. Large-scale, multicenter randomized trials with standardized protocols are needed to validate these findings and to comprehensively assess the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of telitacicept in patients with IgAN.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that telitacicept significantly reduced proteinuria in IgAN patients with an acceptable safety profile, comparable to traditional therapy, and provides an alternative therapeutic strategy. However, considering the inherent heterogeneity, further large-scale studies are necessary to identify patient subgroups that may benefit most from this treatment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge their colleagues at the Department of Nephrology, Xin Hua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for their support and assistance during the study period.

Abbreviations

- IgAN

Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy

- ESKD

End-stage Kidney Disease

- RASi

Renin-angiotensin System Inhibitors

- SGLT2i

Sodium-glucose Co-transporter-2 Inhibitors

- Gd-IgA1

Galactose-deficient IgA1

- BlyS

B-Lymphocyte Stimulator

- BAFF

B-cell-activating Factor

- PSM

Propensity Score Matching

- OR

Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- MMF

Mycophenolate Mofetil

- eGFR

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- CR

Complete Remission

- PR

Partial Remission

- NR

No Response

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SMD

Standardized Mean Differences

Author contributions

Hui Li and Chong Zhang conceptualized the study concept and design. Hui Li and Ya Zhang conducted research and analyzed the data. Hui Li drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470705), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (24ZR1450200) and Sailing Special Project of Shanghai Rising-Star Program (23YF1425400).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Xin Hua Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. XHEC-C-2023-086-1). Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the identifiable information of the patients was anonymized.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berthoux FC, Mohey H, Afiani A. Natural history of primary IgA nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28(1):4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moriyama T, Tanaka K, Iwasaki C, Oshima Y, Ochi A, Kataoka H, et al. Prognosis in IgA nephropathy: 30-year analysis of 1,012 patients at a single center in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Natale P, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Saglimbene VM, Craig JC, Vecchio M, et al. Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3):CD003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manno C, Torres DD, Rossini M, Pesce F, Schena FP. Randomized controlled clinical trial of corticosteroids plus ACE-inhibitors with long-term follow-up in proteinuric IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2009;24(12):3694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathur M, Sahay M, Pereira BJG, Rizk DV. State-of-art therapeutics in IgA nephropathy. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34(5):417–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhillon S. Telitacicept: first approval. Drugs. 2021;81(14):1671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He B, Raab-Traub N, Casali P, Cerutti A. EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 cooperates with baff/blys and APRIL to induce T cell-independent Ig heavy chain class switching. J Immunol. 2003;171(10):5215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belnoue E, Pihlgren M, McGaha TL, Tougne C, Rochat AF, Bossen C, et al. APRIL is critical for plasmablast survival in the bone marrow and poorly expressed by early-life bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2008;111(5):2755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xin G, Shi W, Xu LX, Su Y, Yan LJ, Li KS. Serum BAFF is elevated in patients with IgA nephropathy and associated with clinical and histopathological features. J Nephrol. 2013;26(4):683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhai YL, Zhu L, Shi SF, Liu LJ, Lv JC, Zhang H. Increased APRIL expression induces IgA1 aberrant glycosylation in IgA nephropathy. Med (Baltim). 2016;95(11):e3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv J, Liu L, Hao C, Li G, Fu P, Xing G, et al. Randomized phase 2 trial of telitacicept in patients with IgA nephropathy with persistent proteinuria. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8(3):499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zan J, Liu L, Li G, Zheng H, Chen N, Wang C, et al. Effect of telitacicept on Circulating Gd-IgA1 and IgA-containing immune complexes in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2024;9(4):1067–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JK, Kim JH, Lee SC, Kang EW, Chang TI, Moon SJ, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of IgA nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):427–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon SJ, Park HS, Kwok SK, Ju JH, Choi BS, Park KS, et al. Predictors of renal relapse in Korean patients with lupus nephritis who achieved remission six months following induction therapy. Lupus. 2013;22(5):527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trimarchi H, Barratt J, Cattran DC, Cook HT, Coppo R, Haas M, et al. Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA nephropathy classification working group. Kidney Int. 2017;91(5):1014–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC. Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(12):3177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng L, Yang K, Wu Y, Yu G, Yan Y, Hao M, et al. Telitacicept: A novel horizon in targeting autoimmunity and rheumatic diseases. J Autoimmun. 2024;148:103291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Liu Y, Li J, Tang C, Wang H, Chen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of telitacicept in IgA nephropathy: a retrospective, multicenter study. Nephron. 2025;149(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M, Suzuki H, Nihei Y, Matsuzaki K, Suzuki Y. Ethnicity and IgA nephropathy: worldwide differences in epidemiology, timing of diagnosis, clinical manifestations, management and prognosis. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16(Suppl 2):ii1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.