Abstract

Relationship satisfaction not only contributes to overall life satisfaction and well-being but also has a positive impact on both physical and mental health. The benefits of online interventions for couples include the circumvention of key barriers to traditional therapy. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to evaluate randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of digital technology-based interventions in improving romantic relationship satisfaction. The aim of the meta-analysis is to quantify the effectiveness of these interventions on relationship satisfaction. Most of the 15 eligible studies reviewed obtained significant results in improving relationship satisfaction, and these effects were often sustained at follow-up. A meta-analysis of six studies revealed a significant, moderate effect size. However, the detected heterogeneity points to variability in intervention effectiveness, which may be attributable to differences in program design, participant population, and delivery method. Digital-based interventions are particularly promising for enhancing relationship satisfaction in couples.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-025-03444-y.

Keywords: Digital interventions, Effectiveness, Meta-analysis, Relationship satisfaction, Systematic review

Introduction

Forming romantic relationships and seeking happiness and satisfaction within them is a natural part of human life. Romantic partnerships play a vital role in individuals’ mental health, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life [1–3]. However, nowadays couples must face several challenges and maintaining a healthy functioning relationship becomes a difficult task.

One such challenge was the Covid-19 pandemic, when couples were exposed to various stressors [4, 5]. In the United States, 34% of couples reported an increase in relationship conflict since the onset of the pandemic [6]. Similarly, studies from European countries revealed a decline in relationship satisfaction during lockdown periods [7, 8] with some regions also reporting an increase in incidents of intimate partner violence [9]. During this period, many psychological services were provided to people predominantly online, which sparked interest in deeper exploration of the effectiveness of online mental health interventions [10, 11].

Particularly for economically disadvantaged couples who are at higher risk of relationship distress and divorce online interventions offer a scalable and accessible form of support [12, 13]. Compared to traditional couple therapies, which have historically been delivered in person such as Behavioral Marital Therapy [14] Cognitive-Behavioral Couple Therapy [15] Emotion-focused Couple Therapy [16] Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy [17] or the Gottman Method Couples Therapy [18] digital interventions are less financially burdensome. They eliminate costs associated with transportation, parking, childcare, and office space, making them more affordable for both clients and providers [19]. Moreover, digital interventions offer increased flexibility, anonymity, and convenience, which can be particularly valuable for individuals who face stigma or logistical difficulties in seeking help [20]. In addition, technology helps overcome geographical limitations, allowing individuals to access support regardless of their location. This is particularly relevant in rural or underserved areas where specialized mental health professionals are often lacking [21, 22].

Defining digital interventions

With the advent of the Internet and digital technologies, these tools have increasingly been integrated into the field of psychology, enabling professionals to deliver services and implement interventions through digital means. However, the terminology for these interventions is inconsistent across the literature. Many authors use various terms including online, web-based, internet-based, eHealth etc. In addition, mobile applications and other digital devices are often used as platforms for delivering these interventions. Given this conceptual ambiguity, we consider it essential to clarify the terminology and provide a clear definition of digital interventions.

In a comprehensive review focused on defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions [23] digital interventions are divided into four main following categories: (1) web-based interventions; (2) online counseling and therapy; (3) internet-operated therapeutic software; and (4) other online activities. Given that our systematic review does not focus on online counseling or other online activities, such as blogs, podcasts, or support groups, we consider it most relevant to elaborate primarily on the first and third categories.

Web-based interventions are defined as primarily self-guided, structured programs delivered through websites, designed to promote psychological or health-related change using evidence-based content and interactive features. At the same time the authors divide web-based intervention into three subtypes such as: (1) web-based education interventions; (2) self-guided web-based therapeutic interventions; and (3) human-supported web-based therapeutic interventions. These interventions are typically characterized by four core components: (1) the nature of the content, which may be educational or focused on facilitating therapeutic change; (2) the use of various multimedia formats such as text, images, audio, video, or animations to deliver the content; (3) the level of interactivity, including features like self-assessment tools; and finally, (4) the presence of guidance and feedback provided to users throughout the intervention. The category of internet-operated therapeutic software is described as involving interventions that utilize advanced computer capabilities, including artificial intelligence, to deliver therapy through means such as dialogue-based virtual therapists, rule-based expert systems, or interactive environments like therapeutic games and 3D virtual spaces [23].

Other authors offer a slightly different classification and conceptualization of digital interventions, distinguishing between telemental health interventions and behavioral intervention technologies [24]. Telemental health interventions use real-time videoconferencing and may include asynchronous communications, eHealth, mHealth, or sensor-based components [25]. Behavioral Intervention Technologies (BITs), which either supplement in-person therapy or provide standalone self-help, are divided into three types: Automated BITs, Guided BITs, and Augmented BITs. Automated BITs operate independently, offering personalized feedback via apps, websites, or phone. Guided BITs combine technology with some human support, improving outcomes by enhancing accountability and motivation [26]. Augmented BITs are used by therapists to complement in-person therapy through the use of digital tools like apps or wearable technology [27].

For the purposes of this paper, we use the term digital interventions as an umbrella term to refer to these approaches in general, both for clarity and to ensure consistency for the reader. However, when describing individual studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis, we retain the original terminology used by the authors.

Tailoring digital interventions for couples

In response to couples seeking support for relationship difficulties, various digital interventions have been developed [13, 28]. Depending on the goals of a couple-based intervention and the specific characteristics of the target sample, researchers have several theoretical and practical approaches at their disposal. Some of the most commonly used frameworks are outlined below.

These approaches are often grounded in the principles of couple relationship education, which can be understood as teaching partners a range of skills that enhance different aspects of relationship functioning. However, it tends to be broader and more general in scope compared to couples therapy, which typically focuses on more specific issues within the relationship [29]. When working within a broader context, such as with couples who have children, interventions may also incorporate other approaches, including: (1) family life education, which fosters relationship skills and parenting competencies; (2) family therapy, which involves diagnostic psychotherapy with a clinical focus, or (3) family case management, which is more closely linked to social services and broader systemic support [30]. Many programs are also grounded in behavioral or cognitive theories, or are derived from specific therapeutic models for couples, as mentioned earlier.

Additionally, based on the severity or stage of relationship distress, interventions can be categorized into three levels: (1) universal prevention programs for young couples who show no signs of distress; (2) indicated programs targeting couples in the early stages of relational difficulties; and (3) selected intervention programs designed for couples experiencing visible and severe distress, where there is a high risk of relationship breakdown [29].

Previous reviews on digital interventions for couples

Previous reviews have explored areas relevant to this research topic, such as a systematic meta-content review that examined the effectiveness of online couple relationship education [31]. This review identified four distinct online programs, of which the OurRelationship program [32] and ePREP [33] were most evidence-based. These programs primarily targeted improvements in relationship satisfaction, communication skills, and emotional well-being, demonstrating medium effect sizes. Additionally, a meta-narrative review [34] supported the long-standing use of digital technologies in family and couple psychotherapy. Their findings showed that online intervention for couples delivered synchronously are feasible, were effective across diverse populations, and produced clinical outcomes comparable to in-person therapy, with high levels of user satisfaction. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to focus specifically on the effectiveness of digital interventions in enhancing relationship satisfaction.

Relationship satisfaction as an important factor of relationship functioning

Relationship satisfaction is defined as an affective response arising from the subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions of the person’s romantic relationship [35]. Relationship satisfaction not only contributes to overall life satisfaction and well-being [3, 36, 37] but also has a positive impact on both physical health [38] and mental health [39]. Other factors closely related to relationship satisfaction are, for example, sexual satisfaction [40, 41] coping with stress [42, 43] and empathy [44, 45].

In a comprehensive study based on several longitudinal investigations into couples, predictors of relationship satisfaction were categorized at both the individual and relationship level. At the individual level, major predictors include factors such as life satisfaction, depression, and insecure attachment style. At the relationship level, key predictors encompass perceived partner commitment, sexual satisfaction, appreciation, conflict frequency, and other relational dynamics [46]. Similarly, a review underscored the importance of both self-reported perceptions and implicit evaluations (automatic, unconscious reactions toward a romantic partner) as predictors of relationship satisfaction. The authors further highlighted the influence of objective factors, including demographic characteristics, stress-inducing life events, and biological markers, in shaping relationship satisfaction [47].

While prior systematic reviews have explored the effectiveness of digital interventions for couples e.g. [31, 34], they have not concentrated specifically on relationship satisfaction as the primary outcome. To our knowledge, this is the first review to focus exclusively on this construct and to complement it with a meta-analytic synthesis, which enhances the robustness of the findings. Focusing a systematic review and meta-analysis on relationship satisfaction is important because it represents a key outcome of couple-based interventions [48, 49]. It not only reflects essential aspects of relationship functioning—such as intimacy and communication—but also predicts mental and physical health, as well as relationship stability [38, 50]. This makes it a valuable indicator for informing both clinical practice and public health efforts [51].

The research aim

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of digital technology-based interventions on improving romantic relationship satisfaction. The aim of the meta-analysis is to quantify the effectiveness of these interventions on relationship satisfaction. The research question guiding this systematic review is: How effective are digital interventions in improving relationship satisfaction among couples based on randomized control trials?

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the 2020 updated guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [52] and the revised Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [53]. To frame our research question, we employed the PICO approach [54] which is commonly used to structure systematic reviews.

Information sources

This systematic review encompasses all the English-language literature available through the Scopus and Web of Science databases, published up to August 7, 2024. Searches were conducted in both databases, examining records (titles and abstracts), and keywords were included in the search where available. The primary focus was on digital interventions for couples or individuals in romantic relationships and relationship satisfaction.

Search strategy

The search strategy was executed in three distinct segments. The first segment focused on the types of studies targeted, utilizing terms related to randomized controlled trials (RTCs), such as (“random*” OR “randomized control trial” OR “RCT” OR “pre-test” OR “post-test” OR “follow-up”). The second segment targeted different types of digital devices used for interventions, including terms such as (“mobile application” OR “tablet app” OR “digital app” OR “web application” OR “digital intervention” OR “internet-based” OR “web-based” OR “computer-based” OR “online intervention”). The final segment focused on the construct “relationship satisfaction”. The complete search syntax used for each database can be found in Appendix Table A1.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review was randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving digital interventions aimed at enhancing relationship satisfaction among couples or individuals in a relationship, aged 18 and above, and written in English. We excluded duplicate studies and those that did not meet our inclusion criteria, such as studies lacking a control or comparator group, those without a randomization process, interventions conducted solely face-to-face, and studies that did not report the key measurement variable – relationship satisfaction.

Selection process

The eligibility criteria were determined by the first author (LK) and the second author (JH). The first author (LK) conducted the database search. The screening process was carried out by the first author (LK) with the help of the third author (DD) under the full supervision of the second author (JH). The first author (LK) and the third author (DD) provided justification for the inclusion or exclusion of studies, which were then reviewed and challenged by the second author (JH). Final inclusion and exclusion decisions were made unanimously by all the authors.

Data collection

All the authors agreed on the variables to be included in the review. The first author (LK) collected the data, which were then checked by the third author (DD) and subsequently verified by the second author (JH). Any uncertainties or inconsistencies encountered during data collection were discussed among the authors. Only variables pertinent to this systematic review were included. A total of nine variables were selected for reporting:

Location where the study was conducted;

Type of study which was RCT (studies with more than two intervention groups were labeled as multi-arm studies);

Type of intervention (as labeled in the selected studies) and title of the intervention (if reported);

Duration of the intervention from pre-test to post-test (in weeks), and follow-up if conducted (in months);

Brief sample characteristics regarding of the couples;

Sample size at baseline for each intervention or control group (in couples or individuals in relationships);

Person with whom the participants had the most contact during the intervention (e.g., researcher, psychotherapist, coach);

Scale used to measure relationship satisfaction;

Study outcomes, focusing primarily on relationship satisfaction and its effectiveness.

Risk of bias and certainty assessment

All the studies in this systematic review underwent a rigorous and independent evaluation process. The first author (LK) performed the initial assessment with the help of the third author (DD), while the second author (JH) conducted a concurrent assessment, ensuring a thorough examination of the literature. The risk of bias in the studies was initially assessed by the first author (LK) and subsequently verified by the third author (DD), with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and agreement. The revised Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [53] were followed to evaluate potential biases, considering domains such as the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. Additionally, the certainty of outcomes was assessed by the primary author and reviewed by the second author, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and agreement.

Data synthesis for meta-analysis

To conduct the meta-analysis, we followed the guidelines outlined in Meta-Essentials [55] specifically Workbook 3: Differences Between Independent Groups – Continuous Data, as our analysis focused on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The meta-analysis comprised of studies from this systematic review, excluding those using the same sample or subsamples, as recommended in the meta-analytic protocols [55]. Another criterion for exclusion was lack of reported data; only studies that provided means and standard deviations at post-test were included to ensure consistency and comparability [55]. Consistent with the systematic review, the meta-analysis focused on scales measuring relationship satisfaction. While various scales were employed across the studies, they all measured the same construct, allowing for their inclusion in a single meta-analysis [55]. The meta-analysis was conducted by the first author (LK), with the process of inclusion and exclusion of studies supervised by the second author (JH). The results of the meta-analysis were independently reviewed and verified by both the second author (JH) and the third author (DD).

Results

Results of the systematic review

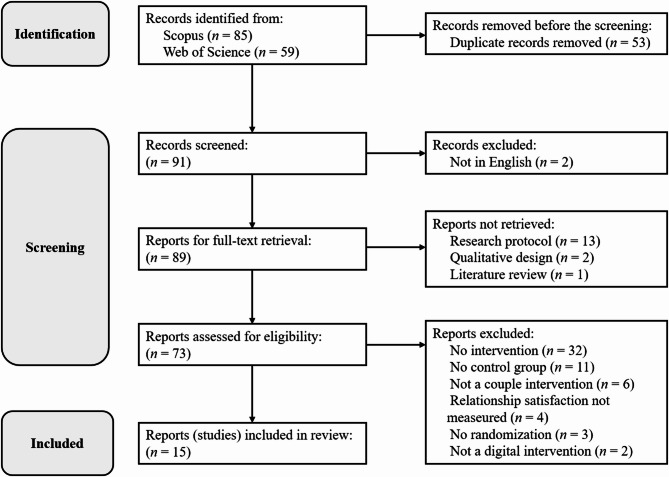

Of the 144 articles initially identified (85 from the Scopus database and 59 from Web of Science) we excluded 53 duplicate records in the preliminary screening. Additionally, two studies written in languages other than English were excluded. We also excluded research protocols, two qualitative studies, and one literature review. The primary reason for excluding studies from this systematic review was that several of them did not employ an intervention design with pre- and post-measurements. Others were excluded due to the absence of a control group or other comparator group. Additionally, some studies were excluded because they did not focus specifically on couples or did not involve digital interventions. Lastly, studies were excluded if they did not measure the construct of relationship satisfaction, or if they lacked a randomization process. This screening process resulted in the identification of 15 eligible studies. For further details, refer to the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of selected reports

Study characteristics

We present a final summary of the selected studies in Table 1, organized alphabetically. Most studies were conducted in the United States [32, 56–62] followed by Australia [63–66] Germany [67, 68] and one study in Japan [69]. Considering the countries of origin of the RCTs included in this systematic review, a degree of geographical diversity across continents is evident. However, all studies were conducted in high-income countries. It is important to acknowledge that even within these countries, many individuals may face barriers to accessing traditional in-person couple therapy due to financial constraints or other limitations. This issue was explicitly addressed in two studies evaluating the OurRelationship program from the United States, which specifically targeted low-income couples [56, 59]. Despite these efforts, we recognize the ongoing need for a broader global expansion of digital interventions aimed at improving relationship satisfaction. However, it is also possible that we did not capture such studies in our systematic review, as we focused only on those published in English. Studies on other digital interventions may have been published in their countries’ native languages and therefore were not included.

Table 1.

Final summary of selected studies

| Reference | State | Study type | Intervention type (name of the intervention) |

Intervention duration (follow-up) | Sample characteristic | n baseline (intervention group/ control group) | Participant’s contact with researcher | Scale measuring relationship satisfaction | Results for outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coulter & Malouff 2013 | Australia | RCT |

Online intervention (Excitement Intervention) |

4 weeks (4 months follow-up) |

Australian couples |

50 couples (Intervention group) 51 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With researcher | Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) | The intervention significantly improved relationship satisfaction (F(1, 101) = 22.14, p < .001, partial η² = .18). Changes in excitement partially mediated this effect (Sobel test: Z = 2.77, p = .006). The effect size for mediation was moderate, with the correlation reducing from r = .33 to partial r = .11. Improvements were maintained at 4-month follow-up. |

| Doss et al. 2016 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship) |

6 weeks | Married, engaged or cohabiting couples |

151 couples (Intervention group) 149 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4) |

Intervention couples significantly improved in relationship satisfaction (d = 0.69) compared to the waitlist group. |

| Doss, Knopp et al. 2020 | USA |

RCT (multi-arm) |

Online intervention (OurRelationship and ePREP - online adaptation of the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program) |

6 weeks (4 and 6 months follow-up) |

Low-income couples |

248 couples (Intervention group - OR) 247 couples (Intervention group - ePREP) 247 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4) |

The main treatment effects show that couples in the OR and ePREP programs experienced significantly greater improvements in relationship satisfaction compared to the waitlist control group. The effect sizes for relationship satisfaction were moderate, with Cohen’s d of 0.53 for OR and 0.42 for ePREP. |

| Doss, Roddy et al. 2020 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship) |

6 weeks (3 and 12 months follow-up) |

Couples with at least one child currently living with them |

112 couples (Intervention group) 101 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4) |

The intervention led to a significant increase in relationship satisfaction (b = 0.581, p < .001) with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.53) compared to the control group. This improvement was also associated with a decrease in coparenting conflict (b = − 2.727, p = .004), with a small to medium effect size (Cohen’s d = − 0.274). |

| Gawlytta et al. 2022 | Germany | RCT |

Internet-based intervention (REPAIR) |

5 weeks (3-, 6- and 12-months follow-up) |

Couples in which at least one member was being treated for PTSD following a sepsis-related ICU stay |

16 couples (Intervention group) 18 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With therapist | Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) | The intervention did not improve relationship satisfaction; the wait group obtained better results. The negative effect size (− 1.67; 95% CI − 2.45 to − 0.89) indicates greater improvement in relationship satisfaction for the wait group than for those who received the intervention. |

| Georgia Salivar et al. 2020 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship and ePREP - online adaptation of the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program) |

6 weeks (4 months follow-up) |

Active-duty and veteran couples |

102 couples (Intervention group) 78 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4) |

The intervention significantly improved relationship satisfaction for military couples compared to the waitlist, with a small effect size (Cohen's d = 0.31 to 0.46). These gains were maintained over four months (within-group d = 0.02 to 0.08). |

| Halford et al. 2012 | Australia | RCT |

Internet-based assessment (RELATE) |

5 weeks (6 months follow-up) |

Married or cohabiting couples |

19 couples (Intervention group 1 - RELATE+) 19 couples (Intervention 2 - RELATE) |

With therapist | Dyadic Adjustment Scale-7 (DAS-7) | Multilevel analysis showed no overall change in relationship satisfaction over time for either men (M = 24.1) or women (M = 23.8), with minimal changes in both genders. There were no significant differences between the RELATE and RELATE + conditions in satisfaction trajectory. |

| Cheok 2020 | Japan | RCT |

Smartphone machine (Kissenger) |

1 week | Couples in long distance relationship |

25 couples (Intervention group) 25 couples (Active control group) |

With researcher | Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) | The experimental group showed a steady increase in relationship satisfaction, while the control group had no change. A significant effect was found for relationship satisfaction (F = 5.24, p < 0.05, partial η² = 0.12), with the experimental group experiencing a notable increase (t = -3.28, p < 0.05). |

| Kavanagh et al. 2021 | Australia | RCT |

Web-based program (Baby Steps Wellbeing) |

3 months (3 months follow-up) |

Co-parenting male-female couples who were expecting a single first child at 26–38 weeks’ gestation |

124 couples (Intervention group - Baby Care) 124 couples (Intervention group - Baby Steps Wellbeing) |

With researcher |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-16) |

Relationship satisfaction declined overall (Cohen's d = − 0.36), with mothers experiencing a greater decrease (–0.46) than fathers (–0.26). The Baby Steps Wellbeing group had less decline in relationship satisfaction compared to Baby Care (Cohen's d = 0.20), indicating a protective effect. |

| Keller et al. 2021 | Germany | RCT |

Online program (PaarBalance program) |

12 weeks (3 months follow-up) |

Couples and individuals in partnership |

56 individuals (Intervention group) 61 individuals (Waitlist control group) |

With researcher |

Partnership Questionnaire (PFB-K) |

The intervention group significantly improved in relationship satisfaction (Cohen's d = 0.77) compared to the control group. |

| Le et al. 2023 | USA | RCT (multi-arm) |

Online intervention (OurRelationship and ePREP - online adaptation of the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program) |

6 weeks (2 and 4 months follow-up) |

Low-income couples |

226 couples (Intervention group – OR full coach) 145 couples (Intervention group – OR contingent coach) 145 couples (Intervention group – OR automated-coach) 224 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4) |

All intervention couples showed significant gains in relationship satisfaction (d full = 0.46, d contingent = 0.47, d automated = 0.40) with no significant differences between them. Over four months, full- and contingent-coach couples maintained gains, while automated-coach couples improved further. |

| McCabe et al. 2008 | Australia | RCT |

Internet-based intervention (Rekindle) |

10 weeks (3 months follow-up) |

Men in stable relationship with erectile dysfunction |

24 individuals (Intervention group) 20 individuals (Waitlist control group) |

With therapist | The Kansas marital satisfaction scale (KMSS) | The treatment group showed significant improvements in erectile function compared to the control group, with a large effect size (η² = 0.21). In terms of sexual relationship satisfaction and quality, the treatment group had significant gains (η² = 0.20 and η² = 0.18, respectively), though overall relationship satisfaction did not differ between groups. |

| Roddy, Georgia et al. 2018 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship) |

6 weeks | Married, engaged or cohabiting couples |

151 couples (Intervention group) 149 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4, 16) |

Lower relationship satisfaction was linked to both LI-IPV (OR = 0.542, p = .002) and CS-IPV (OR = 0.206, p < .001). LI-IPV did not significantly impact the OR intervention's effect on satisfaction (b = -0.057, p = .611). Effect sizes were medium for LI-IPV (Cohen’s d = 0.65) and slightly larger for non-LI-IPV (Cohen’s d = 0.78). |

| Roddy, Rothman et al. 2018 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship) |

6 weeks | Married, engaged or cohabiting couples |

177 couples (Intervention group – high coaches’ support) 179 couples (Intervention group – low coaches’ support) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-16) |

Both low-support and high-support groups showed significant improvements in relationship satisfaction (low-support Cohen's d = 0.52, high-support Cohen's d = 0.61) with no significant difference between them (Cohen's d = 0.09). |

| Roddy et al. 2020 | USA | RCT |

Online intervention (OurRelationship) |

8 weeks (12 months follow-up) |

Married, engaged or cohabiting couples |

151 couples (Intervention group) 149 couples (Waitlist control group) |

With coaches |

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-16) |

Couples in the treatment group experienced greater increases in satisfaction over time (b = .304, p < .001). This was linked to increased problem-solving confidence (b = .506, p < .001), reduced negative communication (b = .222, p = .024), and enhanced emotional intimacy (b = .335, p = .003). Positive communication during treatment predicted sustained satisfaction at follow-up, despite no significant changes during the follow-up period |

Regarding study design, all the selected studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with two studies classified as multi-arm due to their inclusion of more than two intervention groups [56, 59]. Among the selected studies, eleven included a waitlist control group alongside intervention groups [32, 56–61, 63, 66–68] three were RCTs with two intervention groups but no passive control group [62, 64, 65] and one study had an active control group [69]. Intervention duration ranged from one to twelve weeks, with most studies including follow-up assessments spanning two to twelve months.

Although we explored digital interventions within a broader conceptual framework, most of the identified studies can be classified, based on existing literature, as web-based interventions. In most cases, the interventions represented a combination of all three subcategories. That is, they were primarily web-based educational interventions, most commonly grounded in cognitive-behavioral approaches. Some trials offered self-guided interventions with automated feedback for participants. However, the majority were human-supported interventions, particularly in the case of the OurRelationship program, where couples were supported by coaches. We also identified some interventions that included support from therapists. Thus, nearly all the included studies can be categorized as using behavioral intervention technologies (BITs). Only one included study featured a unique form of intervention that would be more appropriately classified as a telemental health intervention due to the use of sensor-based components, or as an internet-operated therapeutic approach. While no direct therapist interaction was present in this case, the intervention incorporated an artificial intelligence-driven system connected to a haptic device compatible with smartphones.

In terms of theoretical orientation and psychoeducational foundation, integrative behavioral couple therapy was frequently applied, especially in the OurRelationship programs, but other approaches were also used, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and cognitive-behavioral writing therapy. Some studies, however, did not clearly specify their theoretical background.

In most cases, the interventions were designed with relationship satisfaction as the primary outcome, while in more specific or clinically targeted studies, this construct was addressed only as a secondary goal. Regarding prevention focus, the studies included couples at different levels of relational distress, which was often assessed alongside relationship satisfaction. In addition, some interventions addressed broader aspects of relationship functioning or individual well-being, such as depression, anxiety, quality of life, or sexual satisfaction etc. However, these variables were not the main focus of this systematic review, since our eligible criteria only defined the condition that the given RCT measured the construct of relationship satisfaction.

The total sample comprised over 7,000 participants, calculated as individual cases. It is important to note that this total includes participants from all studies, even though some studies had overlapping samples or subsamples derived from larger studies that had already been included [57, 58, 60, 61]. Participants included both couples and individuals in relationships, such as married, engaged, or cohabiting couples, as well as low-income, parenting, and long-distance couples and other couple types. Regarding gender composition, the majority of studies focused on exclusively on heterosexual couples, with several also included same-sex couples [56, 59, 63]. Two studies specifically targeted couples who were either expecting a child [65] or already raising at least one child in the household [57]. In addition, several studies examined specific populations, such as military couples [58] or addressed issues related to intimate partner violence [61]. While most of the included studies targeted non-clinical samples, one study examined couples in which one partner was experiencing posttraumatic stress symptoms after severe sepsis [67] and another focused on men in partnership who had been diagnosed with erectile dysfunction [66].

During the interventions, participants interacted most frequently with coaches [32, 56–62] with the level of support varying across studies. Interaction with researches were reported in several studies [63, 65, 68, 69] a category that also includes studies in which no other form of participant support or interaction was specified. Therapist involvement was noted less frequently [64, 66, 67] with two of these studies including the clinical samples described above [66, 67].

The most frequently used scale for measuring relationship satisfaction was the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI) [70] available in different item formats [32, 56, 58–62, 65]. The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) [71] was the second most commonly used measure [63, 67, 69]. Three other scales were used in a single study: the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-7) [72] in a study [64] the Partnership Questionnaire (PFB-K) [73], which is in German [68] and the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (KMSS) [74] in research [66].

Effectiveness of intervention on relationship satisfaction

A systematic review and meta-analysis focused specifically on relationship satisfaction is essential, as it targets the primary and most meaningful outcome of couple-based interventions [48, 49]. Relationship satisfaction is a widely used indicator of treatment success and reflects core dimensions of relational functioning, such as emotional intimacy, communication, and commitment. Moreover, relationship satisfaction is a robust predictor of individual mental and physical health outcomes, and reduced risk of separation or divorce [38, 50]. As such, it provides a foundational metric for evaluating and improving both clinical practice and public health initiatives aimed at enhancing intimate relationship quality [51]. In the following section, we provide a brief overview of the interventions used in the included studies, with a primary focus on their outcomes related to relationship satisfaction. The studies are synthesized based on shared characteristics, such as the type of contact participants had during the trials, the typical profiles of participating couples, or the structure of comparison groups, whether between intervention and control groups or between two or more intervention groups. The overview begins with interventions that demonstrated strong effectiveness and moves on to those with more modest or limited effects.

Japanese study examined the effectiveness of a novel haptic device for smartphones, named the Kissenger machine, on enhancing relationship satisfaction in long-distance couples. The Kissenger machine is a haptic device designed to simulate realistic kissing sensations through a mobile phone. It uses sensors to measure the pressure applied by the user’s lips and transmits this data in real time to another device, which recreates the sensation using localized normal force stimulation. The device attaches to a smartphone, allowing users to see their partner’s face via a mobile app while exchanging real-time virtual kisses through a lip-like interface. During a one-week trial, couples in the experimental group were instructed to use the Kissenger device during their daily communication, while couples in the control group interacted without it. The results showed that those in the intervention group who used the Kissenger experienced significant improvements in relationship satisfaction compared to the control group, who communicated solely through social media without any physical touch simulation. At the same time, this study was the only one in our systematic review to incorporate a specialized digital device beyond standard platforms such as computers, tablets, or smartphones [69].

While the Kissenger intervention [69] focused on enhancing relationship satisfaction through the physical simulation of kissing, another study targeted an overall relationship excitement. Conducted among Australian couples, this study was based on the premise that relationship excitement tends to fade over the course of a relationship, leading to boredom, routine, and ultimately, decreased relationship satisfaction. Results showed that couples who completed the intervention reported significantly higher levels of both relationship excitement and satisfaction at post-intervention compared to those in the waitlist control group. These positive effects were also sustained at follow-up. During the trial, researchers sent participants three weekly emails to check in on their progress and motivate them to continue with the activities, however, no additional support or contact was provided beyond these emails [63]. A similar approach was adopted in a trial conducted with distressed couples in Germany, where participants received standardized emails throughout the intervention to help maintain motivation and engagement. This intervention, titled PaarBalance, aimed to evaluate its effectiveness in improving relationship satisfactiondrawing on principles of Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy. The results showed that couples in the intervention group experienced significant improvements in relationship satisfaction and these results were maintained during follow-up. The waitlist control group demonstrated no change in relationship satisfaction [68].

In contrast to the previously described RCTs, several subsequent studies focused on a single online intervention known as OurRelationship developed to help couples address a specific relationship issue of their choice and grounded in the principles of Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy. These trials typically included structured support from trained coaches, delivered via telephone or video calls, with the level of contact varying across studies. All studies evaluating this program were conducted in the United States. The earliest OurRelationship online intervention included in this systematic review primarily focused on evaluating the program’s initial efficacy. This research compared outcomes between an intervention group and a waitlist control group in a nationally representative sample of married, engaged, or cohabiting couples. Couples were provided with four conversations with coaches either by phone or video call during the intervention. The authors reported a significant increase with medium effect in relationship satisfaction among participants in the intervention group compared to the control group [32]. The original RCT was later extended with a follow-up study that examined the mechanisms underlying changes in relationship satisfaction during and after participation in the OurRelationship program. The findings revealed significant improvements in relationship satisfaction throughout the intervention period compared to the waitlist control group. Relationship satisfaction remained stable and did not significantly change during the follow-up period [60].

Other OurRelationship trials targeted specific subgroups of couples, while the setting and coach support remained largely consistent. Couples in the intervention groups typically participated in four 15-minute videoconference calls with their coaches. Among these, the first study focused on couples experiencing intimate partner violence. The findings revealed that the couples in the intervention group reported significant improvements in relationship satisfaction [61]. In the other study, the research focused on the impact of an online intervention on coparenting conflict and child adjustment in couples with at least one child. The findings showed an increase in relationship satisfaction compared to the control group. However, these improvements were not sustained at the one-year follow-up [57]. Lastly, authors investigated the effectiveness of the OurRelationship and other ePREP programs among military couples, comparing them to a waitlist control group. The ePREP program is an online preventive relationship education intervention designed to improve relationship functioning [33]. The findings indicated that relationship satisfaction significantly improved in both intervention groups and that these improvements were sustained at follow-up. Only minor differences were reported between the two online interventions [58].

Similar to the study involving army couples, another trial, categorized in our review as a multi-arm RCT, evaluated the effectiveness of the OurRelationship and ePREP programs among low-income couples. Participants in the intervention groups had scheduled weekly calls with coaches throughout the program, and additional support was available via email. Minimal differences were observed between the two intervention groups, with participants in both programs demonstrating significant increases in relationship satisfactioncompared to the control group. These positive changes were maintained at follow-up [56]. Another, even more extensive, multi-arm RCT examined the effectiveness of the OurRelationship program among low-income couples by comparing different levels of coach support provided to participants across three intervention conditions. These included: (1) a full coach group, which received comprehensive support similar to other previously described studies, including four scheduled phone calls with a coach; (2) an automated coach group, which received only one initial phone call followed by email communication; and (3) a contingent coach group, which also received an initial phone call, with subsequent support depending on the participants’ level of engagement. Participants in all three intervention groups experienced significant improvements in relationship satisfaction compared to the waitlist control group, and these effects were sustained at follow-up, with no consistent differences observed across the intervention conditions [59].

The final OurRelationship study included in this review also examined whether coach contact moderated the gains achieved during the intervention. Participants were assigned to one of two intervention groups, without the inclusion of a waitlist control group. Couples in both conditions experienced significant improvements in relationship satisfaction. In the low-support condition, participants received only one phone or video call from a coach during the intervention, whereas the high-support group received the full set of four scheduled calls. In both groups, coaches were available for technical assistance if needed. Despite the differing levels of support, no significant differences were found between the groups in terms of improvements in relationship satisfaction [62]. An Australian study similarly addressed the question of effectiveness, this time focusing on the therapist guidance. The intervention was based on an internet-delivered assessment program RELATE, designed to enhance relationship satisfaction, grounded in couple relationship education. In this RCT, married couples were assigned to one of two intervention groups, with no waitlist control group. The first group received a single phone call from a therapist who provided feedback on the couples’ scores during the intervention, while the second group received no feedback. Although couples in both groups maintained high levels of relationship satisfaction, the authors reported no significant differences between the groups over time. However, participants in the condition that included therapist guidance reported higher levels of satisfaction with the intervention [64].

While all of the previously described RCTs either explicitly reported relationship satisfaction as the primary outcome or did not specify it, the following three studies identified relationship satisfaction as a secondary outcome alongside other targeted variables.

The first of these studies focused on a specific sample of men experiencing erectile dysfunction. It was an Australian internet-based intervention Rekindle, primarily designed to enhance sexual satisfaction within couples. The program was grounded in cognitive behavioral therapy and participants were in touch with a therapist at least once per week throughout the duration of the intervention. Although men in the intervention group reported improvements in sexual satisfaction within their relationship compared to those in control group, there were no significant gains in overall relationship satisfaction, and this finding remained consistent at follow-up [66]. The second RCT, which also included an intervention and a waitlist control group, targeted a clinical population as well, specifically German couples in which at least one partner was receiving treatment for post-traumatic stress following a sepsis episode. The intervention, titled REPAIR, primarily aimed to reduce PTSD symptoms and was based on a cognitive-behavioral writing therapy approach. Participants in the intervention group were instructed to write a series of essays, and after each submission, a therapist provided personalized feedback and further instructions within one working day. Interestingly, the study reported a greater decline in relationship satisfaction within the intervention group compared to the control group [67].

Finally, the last study included in this systematic review was conducted in Australia and focused on a specific sample of couples expecting their first child. This web-based intervention aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an educational program centered around childcare-related information. The primary outcomes were self-reported depression and psychosocial quality of life, while relationship satisfaction was assessed as a secondary outcome. RCT included two intervention groups: one received a comprehensive interactive program called Baby Steps Wellbeing, while the other was assigned to a less extensive version named Baby Care. Throughout the intervention, couples received automated emails from the research team, but these did not constitute ongoing personalized support. Results indicated an overall decline in relationship satisfaction during the intervention period. Notably, this decline was less pronounced in the Baby Steps Wellbeing group, which offered more integrative content and additional participant resources. However, the drop in relationship satisfaction persisted even during the follow-up period after the birth of the child [65].

A closer look at the included trials reveals several factors that seem to influence whether an intervention successfully improves relationship satisfaction. In most cases, the included interventions demonstrated effectiveness in improving relationship satisfaction, particularly those that: (1) targeted this construct as the primary outcome, (2) were conducted with non-clinical samples, and (3) involved direct support from a coach during the intervention. This subset was largely composed of OurRelationship studies. Notably, none of the other identified trials incorporated coaching as part of the intervention. In contrast, interventions in which couples received feedback and support from therapists did not prove effective in increasing relationship satisfaction.

In terms of relationship satisfaction as a primary versus secondary outcome, we assume that studies targeting this construct as a primary goal likely devoted more attention to it during the intervention itself, which may have increased the likelihood of effectiveness. In contrast, the potential for improving relationship satisfaction among participants with specific clinical issues remains more debatable. Specifically, this included a digital intervention Rekindle for men experiencing erectile dysfunction [66] and couples affected by PTSD following sepsis in REPAIR intervention [67].

As previously mentioned, the studies that provided participants with support from coaches during the intervention proved to be effective in enhancing relationship satisfaction. However, studies that specifically aimed to compare varying levels of support did not show significant differences based on the degree of support provided [59, 62]. This was also the case in the RELATE intervention, where one group received feedback from therapists and the other did not [64]. Based on the findings from the studies included in our systematic review, we can conclude that involving coaches or therapists during the intervention contributed to participants’ satisfaction with the program.

The results suggest that digital interventions for couples demonstrate a generally positive impact on relationship satisfaction, with varying levels of effectiveness depending on the program design, population, and intervention features. Collectively, these findings underscore the promise of digital interventions for improving relationship satisfaction.

Quality assessment of studies

Regarding the risk of bias [53] (see Table 2), Most concerns were identified in assessing the randomization process and deviation from intended interventions. However, all the studies were deemed to have a low risk of bias in missing outcome data. Variability in bias assessment was most evident in addressing the measurement of outcomes, where the risk of bias ranged from low to high. Notably, a high risk of bias was predominantly associated with the selection of reported resultsTwo studies [51, 53] were assessed as having a low risk of bias across all domains. Eight studies were categorized as having some concerns regarding potential bias [59, 61–64, 66, 68, 69]while five studies were classified as high risk [32, 56–58, 60]. All of these five studies were evaluations of the OurRelationship online intervention. However, it is important to note that the RoB 2 tool applies stringent methodological criteria, which tend to favor clinical RCTs. The design and target population of these studies focused on non-clinical samples, yet the authors consistently reported improvements in relationship satisfaction, with many of these effects persisting at follow-up. In contrast, two studies involving clinical populations, one assessed as having some concerns in men with erectile dysfunction, and another rated as low risk of bias in participants with PTSD, did not show significant improvements in relationship satisfaction. Furthermore, an additional study with a low risk of bias, conducted among couples expecting their first child, even reported a decline in relationship satisfaction during the course of the intervention. In all three cases, the studies targeted highly specific populations undergoing significant life events, where relationship satisfaction was treated as a secondary outcome.

Table 2.

Risk of bias summary for the selected studies

| Reference | Randomization process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coulter & Malouff 2013 | SC | L | L | SC | L | SC |

| Doss et al., 2016 | SC | SC | L | H | H | H |

| Doss, Knopp et al. 2020 | SC | SC | L | H | H | H |

| Doss, Roddy et al. 2020 | SC | SC | L | SC | H | H |

| Gawlytta et al. 2022 | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Georgia Salivar et al. 2020 | SC | SC | L | H | H | H |

| Halford et al. 2012 | SC | SC | L | L | L | SC |

| Cheok 2020 | SC | L | L | L | L | SC |

| Kavanagh et al. 2021 | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Keller et al. 2021 | L | SC | L | SC | L | SC |

| Le et al. 2023 | SC | SC | L | SC | L | SC |

| McCabe et al. 2008 | SC | SC | L | SC | L | SC |

| Roddy, Georgia et al. 2018 | SC | SC | L | SC | L | SC |

| Roddy, Rothman et al. 2018 | SC | L | L | L | L | SC |

| Roddy et al. 2020 | SC | SC | L | SC | H | H |

Note: If all domains were assessed as having a low risk of bias, the overall bias was classified as low risk (L). If even one domain was rated as high risk, the overall bias was classified as high risk (H). If no domain was rated as high risk, but there were a combination of low risk and some concerns across domains, the overall bias was classified as having some concerns (SC)

Results of the meta-analysis

A total of six studies from the systematic review were included in the meta-analysis [32, 56, 59, 62, 63, 66] as we attempted to contact the all other original study authors to obtain the necessary means and standard deviations. However, since we did not receive the required data, we proceeded with the analyses based on the available information. Studies were excluded if they involved duplicate samples [58, 60, 61] or subsets of the same sample [57] as recommended in the meta-analytic procedures [55]. Additionally, studies that lacked sufficient data (means and standard deviations) for the meta-analytic calculations were excluded [64, 65, 67–69].

An additional three studies were included in the meta-analysis following calculations to account for multiple groups within them. Specifically, one study [32] reported post-test means and standard deviations separately for men and women so these groups had to be combined. Additionally, two other studies [56, 59] were conducted as multi-arm RCTs, meaning they contained two or more intervention groups. In line with the recommended guidelines [53] we combined the groups in each study to calculate the overall means and standard deviations for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis included studies that utilized standardized scales to measure relationship satisfaction. The Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI) [70] was used in four studies [32, 56, 59, 62] while the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) [71] was utilized in one study [63] and the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (KMSS) [74] in another [66].

We employed a random-effects model to estimate effect sizes using Hedges’ g [75]. Heterogeneity was assessed using Q-statistics and the I2 index. To evaluate potential publication bias, we analyzed funnel plots following the methodology outlined previously [55]. For clarity, we provide brief definitions of key meta-analytic terms used in this study.Hedges’ g is a standardized mean difference effect size that adjusts for small sample bias and allows for comparison across studies with different measurement scales. The Q-statistic assesses heterogeneity among the included effect sizes; a significant Q indicates more variability than expected by chance. The I² index quantifies the proportion of variance across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% typically interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [76]. The prediction interval provides a range in which the true effect size of a future study is expected to fall, accounting for between-study variability.

Table 3 summarizes the effect sizes for each study included in the meta-analysis. The largest effect size was observed in [63], with Hedges’ g = 0.61, indicating a strong positive impact of the intervention. This was closely followed by [32] (g = 0.56) and [59] (g = 0.48). Studies by [56] and [62] reported moderate effect sizes of 0.42 and 0.16, respectively [66]. showed the smallest effect size (g = 0.02), suggesting limited efficacy in its specific context.

Table 3.

Effect sizes of digital interventions for enhancing relationship satisfaction

| Study | Hedges’ g | CI Lower limit | CI Upper limit | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coulter & Malouff, 2013 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.89 | 12.08% |

| Doss et al. 2016 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.73 | 18.90% |

| Doss, Knopp et al. 2020 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 23.74% |

| Le et al. 2023 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 23.46% |

| McCabe et al. 2008 | 0.02 | -0.72 | 0.75 | 2.95% |

| Roddy, Rothman et al. 2018 | 0.16 | -0.01 | 0.34 | 18.87% |

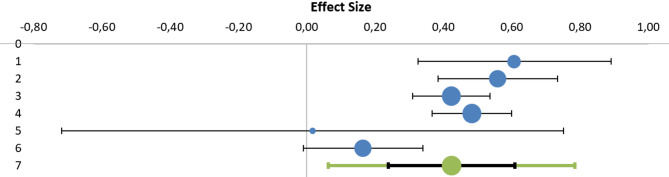

Figure 2 provides a forest plot summarizing the effect sizes and confidence intervals for each study. Combined effect size for including studies on relationship satisfaction was significant (p < .001), Hedges’ g = 0.42. Heterogeneity was detected among the included studies (Q = 14.60, pQ 0.012), which was confirmed by I2 = 65.75%.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analytical results of effect sizes for relationship satisfaction. Note: Effect sizes are given in Hedges’ g (95% CI). The size of the blue bullets indicates the weight of each study in the meta-analysis. The green bullet represents the weighted average effect (combined effect size), while the black lines show the confidence interval, and the green lines depict the prediction interval

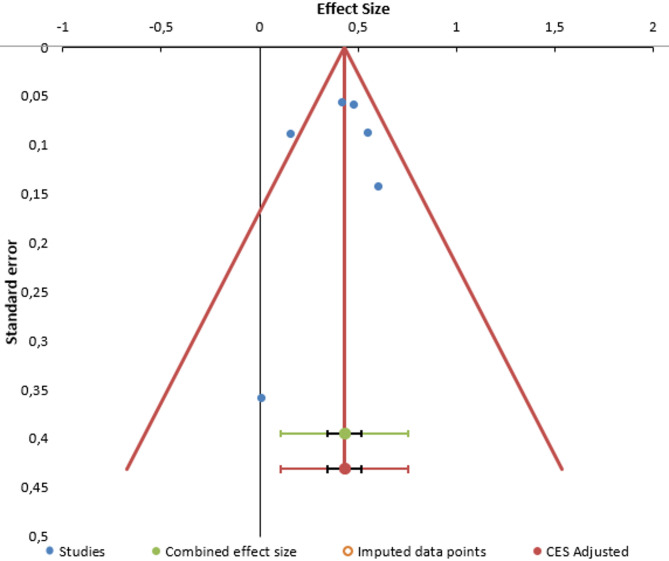

The funnel plot shown in Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of effect sizes relative to their standard errors. The relatively symmetrical shape of the plot suggests minimal publication bias, strengthening the credibility of the meta-analytic findings.

Fig. 3.

Publication bias funnel plot. Note: Each dot represents a single RCT. The Y-axis shows the standard error, with lower-power studies appearing lower in the funnel and higher-power studies at the top. The X-axis represents the SMD, where asymmetrical distribution of dots indicates potential bias

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to evaluate digital interventions for couples or individuals in romantic relationships aimed at enhancing relationship satisfaction, based on randomized controlled trials. Although previous systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of digital interventions for couples [31, 34] they did not focus exclusively on relationship satisfaction as the primary outcome. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review specifically targeting this construct, which is additionally strengthened by the inclusion of a meta-analysis.

Discussion on systematic review

All 15 studies identified in this systematic review were conducted as RCTs. Most of them included an intervention group compared to a waitlist control group. A smaller number employed two active intervention arms, and some were multi-armed trials, meaning they included more than two study groups. The majority of studies also incorporated follow-up assessments to examine the lasting effects of the interventions over time.

The findings of this systematic review indicate that digital interventions demonstrate overall effectiveness in improving relationship satisfaction among couples, although their impact is not uniform across all contexts. Interventions that explicitly targeted relationship satisfaction as a primary outcome, were conducted with non-clinical samples, and incorporated structured support from coaches—most prominently the OurRelationship program—showed the most consistent and sustained improvements. In contrast, interventions in which relationship satisfaction was treated as a secondary outcome, particularly those addressing clinical populations such as men with erectile dysfunction or couples coping with posttraumatic stress, yielded limited or no improvements. Similarly, therapist feedback alone did not appear to enhance relationship satisfaction. Taken together, the evidence suggests that digital interventions, especially coach-supported, prevention-focused programs, are a promising and scalable approach for enhancing relationship satisfaction among couples, though their effectiveness in clinical and more diverse populations remains less certain.

It is important to note that the term “intervention” in this review encompasses a variety of approaches aimed at enhancing couple well-being. These include therapeutic or clinical treatments, psychoeducational programming, and support services, as differentiated in the literature [30]. Our review’s findings therefore inform not only couples therapy but also a broader spectrum of digital efforts designed to support relationship satisfaction and relational health.

Studies offering participants coaching support during the intervention were effective in enhancing relationship satisfaction. However, trials comparing different levels of support found no significant differences in outcomes [59, 62]. Similarly, in the RELATE intervention, receiving therapist feedback did not lead to better results [64]. Overall, the evidence from our review suggests that the presence of coaches or therapists contributed to participants’ satisfaction with the program. This finding indicates that while the presence of support matters, the intensity or source of that support might not be as critical as previously assumed. It may suggest a threshold effect where minimal support suffices to foster participant satisfaction and progress, or that other factors such as intervention content and participant characteristics play a larger role in determining effectiveness. Based on these findings, we can tentatively conclude that involving coaches or therapists during digital interventions adds value by enhancing participant satisfaction with the program. This involvement may contribute more to participants’ perception of support and engagement rather than directly amplifying treatment effects. Future research should further explore the nuances of support, including the quality, timing, and nature of coach or therapist interactions, to better understand how to optimize these roles. Additionally, investigating participant preferences and individual differences could illuminate for whom and under what conditions various levels of support are most beneficial [77].

Discussion on meta-analysis

Our results align with prior reviews [31, 34] which highlighted the efficacy of online interventions in improving various aspects of relationship functioning, including satisfaction, communication, and emotional well-being. However, while previous studies examined a broader scope of relational outcomes, this review specifically focused on relationship satisfaction as the primary construct, making our contribution unique. Notably, the moderate overall effect size observed in this meta-analysis (Hedges’ g = 0.42) is consistent with medium effect sizes reported in a similar systematic review [31].

Across the 15 studies included, the majority reported statistically significant improvements in relationship satisfaction, with sustained effects at follow-up in several cases. Variations in program design, population demographics, and delivery methods were evident, contributing to the heterogeneity (I² = 65.75%) observed in the meta-analysis. For instance, interventions such as the OurRelationship program demonstrated medium to large effects across diverse couple groups. Additionally, two studies focused on specific subpopulations, such as men with erectile dysfunction [66] and long-distance couples [69] providing tailored insights into the contextual applicability of digital interventions. While self-guided interventions, such as PaarBalance [68] effectively improved relationship satisfaction, guided interventions with coach or therapist involvement, such as the OurRelationship program, consistently demonstrated better outcomes, potentially due to increased accountability and personalized feedback. Conversely, some interventions, such as REPAIR [67] yielded negative effects, underscoring the importance of considering unintended consequences when designing interventions for complex relational contexts like PTSD.

The meta-analysis of six studies revealed a significant, moderate effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.42, p < .001), supporting the overall efficacy of digital interventions in enhancing relationship satisfaction. However, the detected heterogeneity (I² = 65.75%) underscores variability in intervention effectiveness, which may be attributable to differences in program designs, participant populations, and delivery methods.

The diversity of the programs examined highlights the adaptability of digital tools to various demographic and clinical needs. From a clinical perspective, the significant improvements observed suggest that digital interventions could effectively complement or provide alternatives to in-person therapy, particularly in underserved populations. However, the variability in outcomes indicates the need to tailor interventions to the couple’s dynamics and life circumstances in order to maximize effectiveness.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the exclusion of studies not published in English may have introduced a language bias, potentially leading to the overlooking of relevant findings from non-English research. Second, while the meta-analysis provided a quantitative synthesis of effect sizes, its scope was constrained by the availability of standardized measures and complete data. Many eligible studies could not be included due to insufficient reporting of means and standard deviations.

Additionally, the heterogeneity of the studies reflects the diversity of digital interventions, participant demographics, and outcome measures, complicating direct comparison and generalization. For example, variations in follow-up durations and intervention designs (e.g., coach involvement versus self-guided programs) likely contributed to differing levels of effectiveness. Moreover, some interventions targeted specific subgroups (e.g., military couples, new parents), limiting the generalizability of findings to broader populations.

Many studies, particularly evaluations of the OurRelationship program, were rated as having “some concerns” or “high risk” of bias due to methodological limitations, even though they reported positive outcomes. Additionally, in several clinical trials, relationship satisfaction was measured only as a secondary outcome, which limits the strength and precision of conclusions regarding the effectiveness of digital interventions in these populations.

Implications for the future and for practice

The findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis will contribute to a deeper understanding of how digital interventions can be effectively applied in psychological research and therapeutic practice to improve relationship satisfaction.

The observed heterogeneity highlights the need for future research to explore factors influencing intervention efficacy, such as cultural differences, program length, and levels of human support. Expanding the scope to include diverse populations and examining long-term outcomes would further contribute to the existing research. Moreover, integrating advanced technologies like artificial intelligence could enhance engagement and personalization in future interventions.

While this review demonstrates that digital interventions can enhance relationship satisfaction, the underlying mechanisms driving these effects remain unclear. Future studies should examine which components such as communication training, emotional intelligence exercises, or personalized coaching—contribute most to positive outcomes [49]. Identifying these mechanisms is crucial for optimizing program design and tailoring interventions to the needs of diverse couples. Research should also investigate user engagement factors and barriers to access to support the effective implementation of digital tools in both clinical and community settings [78].

Most existing research has focused on non-clinical, community samples, leaving a gap in understanding how clinically distressed couples or those with comorbid mental health difficulties respond to digital interventions. Targeted studies in these populations are needed to ensure clinical applicability. Until more evidence is available, practitioners should consider digital interventions as complementary to traditional therapy, providing flexible options for underserved or hard-to-reach groups [79].

Methodologically, incorporating waitlist or passive control groups can strengthen causal inferences. For example, the OurRelationship program’s RCT with a two-month waitlist group reported significant improvements in relationship satisfaction (Cohen’s d = 0.69) compared to controls [32]. In addition, long-term follow-up assessments are essential to evaluate the sustainability of outcomes and determine the need for booster sessions or blended care models.

Current trials also predominantly involve heterosexual couples, highlighting the need to assess effectiveness in LGBTQ + populations. Early evidence, such as a pilot adaptation of the Relationship Checkup for LGBTQ + couples, suggests these interventions can be feasible, acceptable, and beneficial for well-being [80] but more rigorous studies are needed. Furthermore, evaluating digital interventions in low- and middle-income countries, as well as across diverse cultural contexts, would help determine their adaptability and global relevance. Finally, direct comparisons of digital, in-person, and hybrid delivery models are warranted to clarify their relative effectiveness and guide practitioners in making evidence-based decisions that consider context, resources, and client preferences.

Conclusion

Digital interventions hold significant promise for enhancing relationship satisfaction among couples. While the findings of this review and meta-analysis are encouraging, continued research is necessary to address current limitations, refine intervention strategies, and expand their applicability to diverse populations within different cultures. By building on the existing evidence base, future studies could further optimize digital interventions to support healthy and satisfying relationships.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- BITs

Behavioral intervention technologies

- CSI

Couples Satisfaction Index

- DAS-7

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale

- KMSS

The Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale

- PFB-K

The Partnership Questionnaire

- PICO

Patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RAS

The Relationship Assessment Scale

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

Author contributions

LK and JH designed the research. LK, JH, and DD analyzed data. LK wrote the first draft of the article, all authors interpreted the results, revised the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V04-00258. Writing this work was supported by the Vedecká grantová agentúra VEGA under Grant 1/0054/24 and Comenius University in Bratislava under Grant UK/1117/2024.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study’s protocol was approved by the Ethical committee of Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences at Comenius University Bratislava FSEV 1647/-4/2022/SD-CIII/1. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study in the original research papers as this article is the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Consent for publication

We agree that the article will be published in BMC Psychology and we will pay the article processing charge.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Evans T, Whittingham K, Boyd R. What helps the mother of a preterm infant become securely attached, responsive and well-adjusted? INFANT Behav Dev. 2012;35(1):1–11. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gustavson K, Røysamb E, Borren I, Torvik FA, Karevold E. Life satisfaction in close relationships: findings from a longitudinal study. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(3):1293–311. 10.1007/s10902-015-9643-7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahnke B, Cooley M. A systematic review of the association between partnership and life satisfaction. Fam J. 2021;29(2):182–9. 10.1177/1066480720977517 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietromonaco PR, Overall NC. Implications of social isolation, separation, and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic for couples’ relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:189–94. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):57. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luetke M, Hensel D, Herbenick D, Rosenberg M. Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(8):747–62. 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1810185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid L, Wörn J, Hank K, Sawatzki B, Walper S. Changes in employment and relationship satisfaction in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the German family panel. Eur Soc. 2021;23(sup1):S743–58. 10.1080/14616696.2020.1836385 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schokkenbroek JM, Hardyns W, Anrijs S, Ponnet K. Partners in lockdown: relationship stress in men and women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Couple Fam Psychol Res Pract. 2021;10(3):149–57. 10.1037/cfp0000172 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brink J, Cullen P, Beek K, Peters SAE. Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Western and Southern European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2021;31(5):1058–63. 10.1093/eurpub/ckab093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigues NG, Han CQY, Su Y, Klainin-Yobas P, Wu XV. Psychological impacts and online interventions of social isolation amongst older adults during COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(3):609–44. 10.1111/jan.15063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye Z, Li W, Zhu R. Online psychosocial interventions for improving mental health in people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;316:120–31. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doss BD, Hatch SG. Harnessing technology to provide online couple interventions. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:114–8. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knopp K, Schnitzer JS, Khalifian C, Grubbs K, Morland LA, Depp C. Digital interventions for couples: state of the field and future directions. Couple Fam Psychol Res Pract. Published online 2021. 10.1037/cfp0000213

- 14.Behrens BC, Halford WK, Sanders MR. Behavioural marital therapy: an overview. Behav Change. 1989;6(3–4):112–23. 10.1017/S081348390000749X [Google Scholar]