Abstract

Background

Light plays a key role in plant growth, development and response to adversity. Plants perceive different wavelengths of light in the environment through various photoreceptors and regulate plant growth and development through light signaling. Nevertheless, it remains unknown how high-altitude plants adapt to different light conditions. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of high-altitude plants responding to light quality, this research compared the transcriptome of P. schneideri cuttings under blue and green film treatments.

Results

Blue film treatment significantly promoted the height growth of P. schneideri, while green film treatment inhibited it, and both treatments significantly suppressed stem thickness growth. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that blue film treatment induced a significantly higher number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) compared to green film treatment, with multiple transcription factor families (such as WRKY, NAC, bHLH, MIKC, and MYB) down-regulated across various treatments. DEGs were primarily enriched in the hormone signaling pathway, where blue film treatment significantly up-regulated the expression of CRY1, HY5 and ARF8 genes, while down-regulating GH3.1, Aux/IAA14 and Aux/IAA16. In contrast, green film treatment exhibited the opposite regulatory pattern.

Conclusion

These results imply that P. schneideri may benefit from blue film treatment in terms of growth and development, which may be helpful for further research into the introduction and cultivation of P. schneideri and other popular species in high-altitude regions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11951-w.

Keywords: Populus Schneideri, Light quality, Growth and development, Auxin response gene

Background

One of the most crucial environmental elements influencing plant growth and development is light [1, 2]. Light environment, encompassing light intensity, quality, and photoperiod [3, 4]. The best and most energy-efficient way to regulate the light environment is to use light quality to govern plant growth and development [5]. Red light stimulates the growth of more leaves, longer stems, and the accumulation of dry matter, whereas blue light inhibits these processes, making plants shorter and denser [6, 7]. While blue light increased stem thickness and lowered seedling height in Anoectochilus roxburghii, red and white light supplementation dramatically boosted seedling height and ground diameter in plants compared to the blank control [8].

Green light was formerly believed to be unnecessary for plant growth and biologically useless light. Although plants absorb less green light, research has proven that this does not indicate that they do not need it [9, 10]. Chloroplasts are directly impacted by green light, which can change a plant’s ability to grow, develop, and adapt to various light conditions [11]. Green light has been reported to be involved in regulating the growth and development of germination, root growth, stem elongation and flowering [12–14]. The photosynthetic rate of lettuce leaves decreased when green light was added, yet plant growth remained unaffected [15].

The intricate network of signal transduction pathways found in plant cells is essential for regulating plant development and metabolism. It has been found that auxins are involved in the regulation of light signaling in plant growth and development, in addition to responding to intrinsic developmental signals [16, 17]. Light signaling influences hormone levels and signal transduction processes in plant cells, which in turn regulate the process of plant growth and development [18]. Transporter inhibitory factor response 1 and growth hormone signaling F-box (TIR1/AFB) proteins are plant-specific receptors that mediate multiple responses to the auxin [19, 20]. When the TIR1/AFB protein binds to indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) or other auxin-like hormones, TIR1/AFB binds to the Aux/IAA protein to form a co-receptor complex. The formation of this complex drives the degradation of the Aux/IAA protein, which activates downstream signaling [21]. Under blue light, CRY1 interacts with IAA proteins to directly inhibit TIR1-IAA production, increase IAA proteins’ stability and hence regulate growth hormone signaling, and prevent plant hypocotyl elongation [22, 23]. Far Infrared Insensitive 219 (FIN219)/Jasmonic Acid Resistant 1 (JAR1) is a JA-binding enzyme primarily responsible for the synthesis of physiologically active JA-isoleucine (JA-Ile) [24, 25]. CRY1 and FIN219/JAR1 inhibit hypocotyl elongation under blue light in Arabidopsis. The function of FIN219/JAR1 is regulated by CRY1, whereas CRY1 function requires optimal levels of FIN219/JAR1 for optimization, which together result in optimal development of photomorphogenic and stress response in plants [26]. Moreover, green light promotes the DNA binding activity of BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1), a master transcription factor of the BR pathway, thus regulating gene transcription to enhance hypocotyl elongation [27]. Thus, light quality regulates photomorphogenesis in plants by interacting with phytohormones and other signaling pathways through specific photoreceptors, which in turn affect developmental processes and environmental adaptation.

Different color films have the ability to transmit light within a specific wavelength range selectively, modifying the quality of the light. In production practice, various colored films are constructed to control the optimum light conditions for plant growth, maximizing photosynthetic efficiency, reducing plant growth cycle length, boosting plant yield, and cultivating higher-value plant species. Covering the colored film to regulate the light environment of the technical means in vegetable and fruit agriculture has achieved numerous results and is widely utilized [28, 29].

Populus schneideri, belonging to the family Salicaceae, is a native tree of the high-altitude regions of southwest China [30]. It is primarily distributed in areas above 4000 m and has good resistance, rapid development, and excellent adaptability to the complex and diverse geographic environments and climatic types of the southwest region [30, 31]. As the altitude increases, the proportion of short-wavelength light in visible light increases, such as blue and ultraviolet light, which have a certain inhibitory or damaging effect on plant growth [32]. It is inevitable for plants to acquire distinct physiological and ecological adaptation mechanisms when they live in harsh conditions like high-altitude regions [33, 34]. In the current study, the effects of blue and green light on plant growth and physiological features were assessed by treating P. schneideri culture cuttings with colorless transparent film, blue film, and green film for 60 days. Furthermore, using RNA-seq technology, the transcriptional level of the plants’ reaction to various light wavebands was studied to determine the molecular basis of that response. The findings provide fresh perspectives on how plants react to light bands at high altitudes, which could help genetically modify plant growth under diverse lighting conditions.

Results

Ratio analysis of transmission spectra in the shed

The light quality components transmitted by various color films differ significantly or extremely significantly, according to an analysis of the ratio of transmission spectra (Table 1). The ratio of blue light and far-red light transmitted by the BF is very significantly higher than that of the GF and the WF; only the ratio of green light under the GF is significantly higher than that of the BF and the WF, while the ratio of BF transmitting red light is very significantly lower than that of the GF and WF. It can be seen that the light transmitted by the BF and GF has the same wavelength as its color light. The BF is better at transmitting far-red light, whereas the WF is better at transmitting red light.

Table 1.

Transmission spectral ratios of different color films

| UV-light | Blue light | Green light | Red light | Far-red light | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF | 0.021 ± 0.003a | 0.156 ± 0.008B | 0.242 ± 0.001B | 0.281 ± 0.007 A | 0.297 ± 0.006B |

| GF | 0.017 ± 0.002b | 0.179 ± 0.012B | 0.288 ± 0.007 A | 0.218 ± 0.012B | 0.296 ± 0.010B |

| BF | 0.016 ± 0.001b | 0.337 ± 0.016 A | 0.196 ± 0.003 C | 0.105 ± 0.006 C | 0.344 ± 0.017 A |

Note: Values are represented as Mean ± SE. Different uppercase letters indicate extremely significant differences among different treatments (P < 0.01), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different treatments (P < 0.05). The same below. BF: Blue film; GF: Green film; WF: The material numbered WF is treated with a colorless transparent film

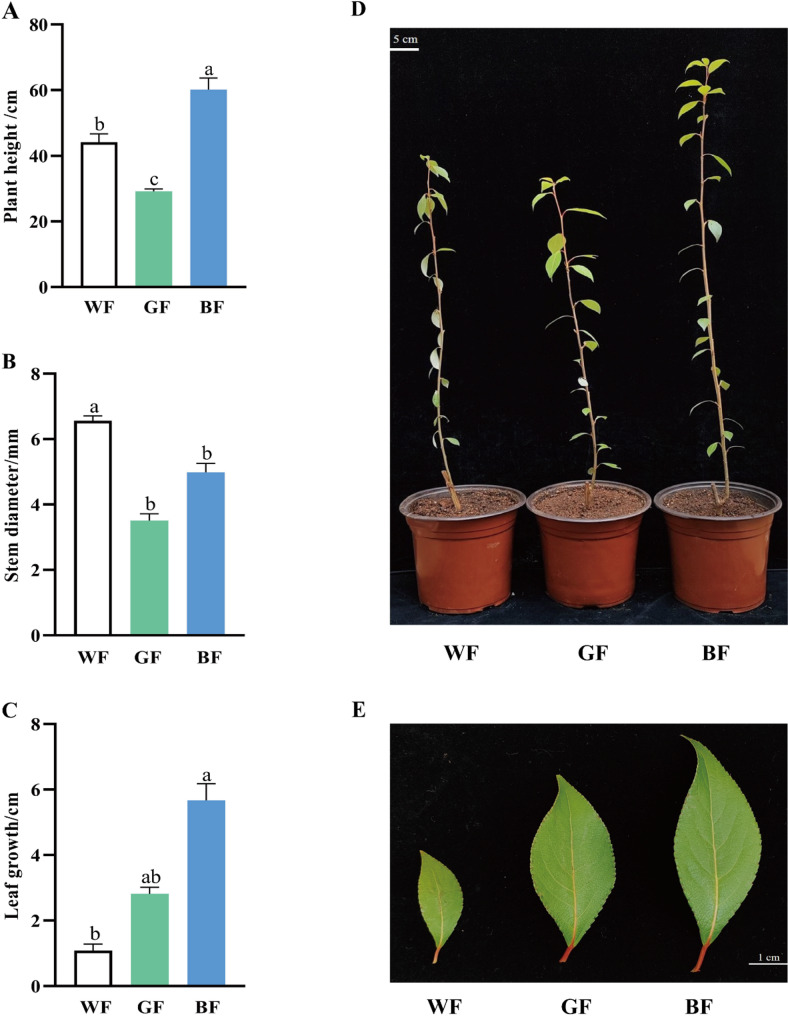

Effects of blue and green film treatments on P. schneideri growth

P. schneideri cuttings grew distinctly different in response to blue, green and white films (Fig. 1). P. schneideri seedlings in the BF treatment were noticeably taller than those in the GF and WF treatments (Fig. 1A, D). The diameter of the ground was considerably less than that of the WF treatment, but it did not differ significantly from that under GF treatment (Fig. 1B, D). While there was no discernible difference in leaf length between the GF and WF treatments, there was a considerable increase in the latter (Fig. 1C, E). It demonstrates that whereas GF has a slight inhibitory influence on plant height, BF has a greater impact on the growth of P. schneideri, which can enhance the rise of leaf elongation and leaf breadth.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the growth of P. schneideri under different treatments. (A) Plant height in different film treatments. (B) Stem diameter in different film treatments. (C) Leaf growth in different film treatments. (D) The whole plant morphology in different film treatments. (E) The leaf morphology in different film treatments

Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in P. schneideri cuttings under different color film treatments

To further investigate the genes involved in the growth regulation of P. schneideri cuttings under different light treatments, we conducted transcriptome analysis on leaves that had been exposed to different colored film treatments for 60 days. Each sample had an effective base number of 5.77 Gb, a GC content of 44.35–45.92%, and a proportion of Q30 bases of 93.04% and above, all of which were indicative of high-quality sequencing (Table S1). The correlation analysis was performed after quantifying the gene expression of 9 samples using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) as an index for assessing the correlation of biological replicates among samples, and the results showed that the R2 values of the three biological replicates within each sample were all greater than 0.95 (Fig. S1), with high correlation, which indicated that the biological replicates of each sample in the present study were good. The principal component analysis (PCA) of all samples showed that the three replicates of the same sample were clustered together with good reproducibility, and different samples were well separated for effective differentiation, further indicating significant differences between groups (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of DEGs of P. schneideri in different comparison groups. (A) PCA analysis; (B) The statistical results of DEGs; (C) Venn diagram; (D) COG analysis of DEGs in BF vs. GF; (E) COG analysis of DEGs in WF vs. BF; (F) COG analysis of DEGs in WF vs. GF

The DEGs were examined and filtered by the criteria of|log 2 (Fold Change)|≥1.5 and P value < 0.05 (Fig. S2, Fig. S3). A total of 1274 DEGs were identified in P. schneideri, of which 799 (WF vs. BF) were up-regulated and 750 genes were down-regulated in BF, and 402 genes were up-regulated and 370 genes were down-regulated in GF, when compared with WF (Fig. 2B). Among them, P. schneideri showed 23 DEGs co-expressed in three comparison groups (Table S2), 938 genes unique to WF vs. BF, and 253 genes unique to WF vs. GF (Fig. 2C). Further mapping of DEGs to the COG database for functional enrichment analysis and revealed that genes in the BF, GF, and WF enriched in the carbonydrate transport and metabolism (G), cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (M), posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones (O), secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism (Q), signal transduction mechanisms (T), and defense mechanisms (V) (Fig. 2D-F). Besides that, general function prediction only (R) was also enriched in the WF vs. BF and WF vs. GF.

Transcription factor (TF) enrichment analysis of DEGs under different treatment conditions

TF play a crucial role in regulating plant responses to various abiotic stresses. A total of 27 TF families were identified in this study (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, there were some differences in the TF families identified in the comparison groups. The BF vs. WF comparison group identified the highest number of differentially expressed TFs and families, with 129 differentially expressed TFs, categorized into 27 TF families. The GF vs. WF comparison group had a higher number of differentially expressed TFs and families, totaling 65 TFs classified into 20 families. The BF vs. WF comparison group identified the fewest genes and families, with 36 DEGs divided into 12 families. These results indicate that the BF vs. WF and GF vs. WF comparisons had more similar results, and the differences between BF and GF were smaller than those in the control group (Table S3). Under different treatments, most genes in the WRKY, NAC, bHLH, MIKC, and MYB families were down-regulated. These gene families contained a high number of DEGs in each of the comparison groups, suggesting that they may play an important role in the response of P. schneideri cuttings to different treatments.

Fig. 3.

TF analysis of DEGs in the three comparison groups

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs based on gene ontology (GO) analysis

To further explore the functions of DEGs, GO enrichment analysis was performed on the DEGs identified in each comparison group (Fig. 4). The enriched genes in three comparisons were annotated in three main GO categories, including “biological process (BP)”, “cellular component (CC)”, and “molecular function (MF)”. The number of DEGs classified to GO in the WF vs. BF group was higher in P. schneideri than in the WF vs. GF group. The highest number of genes was enriched for CC, with 705, 2492 and 1112 genes enriched for BF vs. GF, WF vs. BF and WF vs. GF, respectively. The MF category was characterized by “catalytic activity” (191 for BF vs. GF, 621 for WF vs. BF and 324 for WF vs. GF) and “binding” (172 for BF vs. GF, 692 for WF vs. BF and 353 for WF vs. GF) were significantly enhanced. In the category of BP, “cellular processes” and “metabolic processes” were significantly enriched. The top GO terms enriched by the two light quality treatments were roughly similar, but the number of DEGs enriched in BF increased significantly (Table S4). The GO terms related to plant growth and development were “photosynthesis”, “hormone”, and “signaling”. DEGs involved in these terms were worthy of follow-up attention.

Fig. 4.

GO categorization of DEGs in the three comparison groups of P. schneideri

KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs

The KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted on the DEGs obtained from each comparison group. The top 20 results of KEGG enrichment for each comparison group are presented in Fig. 5 and Table S5. Among them, the pathways of “plant-pathogen interaction,” “plant hormone signal transduction,” “MAPK signaling pathway - plant,” and “starch and sucrose metabolism” exhibited the largest number of DEGs. WF vs. BF was most significantly enriched in the metabolic pathways of “flavonoid biosynthesis,” “carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms,” and “ABC transporters,” while WF vs. GF was most significantly enriched in the metabolic pathways of “carotenoid biosynthesis,” “flavonoid biosynthesis,” and “plant circadian rhythm.” This indicates that these metabolic pathways play crucial roles in regulating the growth and metabolism of P. schneideri treated with BF and GF.

Fig. 5.

KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in different comparison groups. (A) BF vs. GF; (B) WF vs. BF; (C) WF vs. GF

Analysis of plant hormone signal transduction pathway

The plant hormone signal transduction pathway was significantly enriched in all three comparison groups and was also annotated in the KEGG classification. A total of 94 DEGs encoding 26 enzymes were identified across eight hormone signal transduction pathways (Fig. 6). Among the auxin pathways, TIR1, ARF, and GH3 were all down-regulated by the BF and GF treatments, while AUX1, IAA, and SAUR were both up- and down-regulated. Within the zeatin pathway, there were a total of 13 DEGs encoding 4 enzymes, of which CRE1 was down-regulated and A-ARR was up-regulated, whereas AHP and B-ARR were both up- and down-regulated. For the gibberellin signaling pathway, 10 DEGs encoding 3 enzymes were identified, among which DELLA was down-regulated and TF was up-regulated, while the gene encoding GID1 was both up- and down-regulated. A total of 6 DEGs encoding 2 enzymes were identified in the abscisic acid signaling pathway, of which ABF was down-regulated and expressed, whereas PP2C was both up- and down-regulated, 7 genes were identified in the ethylene signaling pathway, all of which were down-regulated, and 25 DEGs encoding 4 enzymes were identified for brassinosteroid, of which BKI1 was down-regulated, BZR1/2 was up-regulated, BAK1 and BRI1 were both up- and down-regulated. 8 differential genes encoding 2 enzymes were identified in the jasmonate signaling pathway, including genes related to JAZ and MYC2, JAZ gene was up-regulated, and MYC2 gene was both up- and down-regulated, and 3 differential genes encoding 2 enzymes were identified in the salicylate signaling pathway, of which TGA was both up- and down-regulated.

Fig. 6.

Plant hormone signal transduction pathway. The rows of the heatmap represent different DEGs, the columns represent gene expression levels under different treatment conditions, and the color scale denotes the expression levels, which are in the order of WF, GF, and BF from left to right

qRT-PCR validation

To validate the accuracy of the RNA-Seq data, 4 genes selected in the growth hormone signaling pathway, ARF8 (Pyun06G00712), Aux/IAA 14 (Pyun08G014880), Aux/IAA 16 (Pyun05G004520), and GH3.1 (Pyun09G009710), as well as the blue light receptor cryptochrome gene (CRY1, Pyun02G008950) and the HY5 transcription factor (HY5, Pyun10G000570). The expression trends of the selected were consistent with the RNA-Seq data, confirming the reliability of the RNA-Seq data (Fig. 7). In addition, comparing the expression profiles under different color film treatments by qRT-PCR, it was found that CRY1, HY5 and ARF8 showed highly significant up-regulation under BF and highly significant down-regulation under GF, whereas the expression trends of AUX/IAA 14, AUX/IAA 16 and GH3.1 were the opposite of them.

Fig. 7.

qRT-PCR validation of the selected genes. (A) Relative expression level of CRY1. (B) Relative expression level of HY5. (C) Relative expression level of ARF8. (D) Relative expression level of AUX/IAA 14. (E) Relative expression level of AUX/IAA 16. (F) Relative expression level of GH3. The data are presented as the mean ± SE. Error bars indicate SD, and different capital letters (A-C) represent significant differences between samples with P < 0.01

Discussion

Plants adapt to their surroundings through changes in growth, and one significant environmental component that affects plant shape is light signaling [35, 36]. Particular light wavelengths can boost plants’ photosynthetic efficiency, which in turn encourages photomorphogenesis [37, 38]. Plant differentiation, biomass growth, and seedling height were all considerably enhanced by blue light cultivation [39, 40]. It was discovered that the green light treatment produced plants that were taller and less branching, similar to the red light treatment, using LEDs to imitate three monochromatic light treatments of Capsicum annuum L [41]. In this study, it was discovered that the BF treatment significantly increased the tall growth and leaf length of P. schneideri, while the GF treatment significantly inhibited the tall growth of P. schneideri, and both the BF and GF treatments significantly inhibited the stout growth of P. schneideri. Contrary to the findings that BF treatment was found to inhibit hypocotyl elongation during photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis [42]. The contrasting effects of blue light on stem/cotyledon growth may be attributed to differences in photoreceptor signaling pathways, hormone regulation networks, and growth development patterns among different plant species.

In this study, the fewest DEGs were found in the BF vs. GF comparison group, indicating that the differences between the BF and GF treatments were smaller than those between the WF and the BF/GF treatments. In both the WF vs. BF and WF vs. GF comparison groups, there were more up-regulated genes than down-regulated genes, suggesting that light treatments induced a greater increase in gene expression. Additionally, a large number of TFs were identified, and the differentially expressed TF families in the WF vs. BF and WF vs. GF comparison groups were relatively similar. This finding implies that BF and GF treatments may regulate plant growth through similar TF family networks, but the differential regulation of downstream genes leads to different phenotypic effects. Among them, WRKY, NAC, bHLH, MIKC, and MYB were the genes with a higher number of DEGs in the comparison groups, indicating that these TF families play central roles in the gene expression regulatory network of P. schneideri in response to BF and GF treatments, and are jointly involved in light signal transduction and growth/developmental responses. Further GO enrichment analysis showed that the three comparison groups exhibited the highest enrichment in the cellular component category, indicating that light quality treatment had the most significant effect on plant cellular components. The results of KEGG analysis showed that the plant hormone signal transduction pathway was significantly enriched in the three comparison groups, and a large number of DEGs were identified in this signal transduction pathway.

Plant growth and development are coordinately regulated by multiple hormones, with light signal changes modulating the levels of various hormones in plants [43–45]. In this study, all eight pathways within the plant hormone signaling network were activated. Notably, the IAA, CTK (cytokinin), GA (gibberellin), and ZT (zeatin) signaling pathways primarily govern processes such as cell expansion, cell division, and stem elongation intimately linked to plant growth dynamics [46–51]. The auxin pathway exhibited the highest number of identified DEGs, suggesting that the auxin signaling cascade regulates a broader gene repertoire under different film treatments to mediate responses to light signal fluctuations. Under BF treatment, the genes GH3.1, Aux/IAA14, and Aux/IAA16 were down-regulated. As negative regulators of auxin signaling, the reduced expression of these genes indicates an increase in endogenous auxin levels. This finding underscores that BF treatment elevates auxin content in P. schneideri, thereby promoting a growth phenomenon consistent with the observed enhancement in height growth of poplars following BF exposure.

Previous studies have established that under visible light, HY5 promotes downstream gene expression by activating transcription of its encoding gene, while concurrently inhibiting hypocotyl elongation through suppression of the auxin signaling cascade [52, 53]. In dark conditions, CRY1 remains inactive, enabling TIR1/AFB to interact with Aux/IAA proteins, facilitate their proteasomal degradation, and release ARFs to activate target gene transcription. By contrast, blue light irradiation triggers direct binding of CRY1 to ARFs, leading to ARF inactivation and subsequent repression of auxin-responsive gene expression [54]. In this study, the up-regulation of CRY1, HY5, and ARF8 under BF treatment implies that blue light-activated CRY1 inhibits ARF8 transcriptional activity via direct protein-protein interaction, thereby down-regulating downstream auxin signaling. CRY1 and HY5 up-regulation coincided with ARF8 down-regulation and marked activation of auxin-responsive genes under GF treatment of P. schneideri. This suggests that GF treatment may disrupt ARF8-mediated auxin signaling, reducing auxin accumulation and eliciting growth inhibition phenotypes. However, further functional validation and molecular confirmation are required to clarify the molecular mechanism by which CRY1 and HY5 affect plant growth through regulating the expression of related genes.

Conclusion

This study systematically explores the molecular mechanisms by which light quality regulates the growth of P. schneideri. Plants regulate gene expression through photoreceptor-mediated signaling pathways to respond to changes in the light environment, while genetic characteristics of different species lead to diversity in light quality response mechanisms. The study found that BF treatment significantly promoted the height growth of P. schneideri, whereas GF treatment showed an inhibitory trend, and both light qualities significantly inhibited stem thickness growth. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that BF treatment induced a significantly higher number of DEGs than GF treatment when compared with the WF. Under different treatment conditions, most differentially expressed TFs belonged to the WRKY, NAC, bHLH, MIKC, and MYB families, all of which were down-regulated across treatments. Moreover, many DEGs were enriched in plant hormone signaling pathways. Expression analysis by qRT-PCR showed that BF treatment significantly up-regulated the expression of CRY1, HY5, and ARF8 genes while down-regulating GH3.1, Aux/IAA14, and Aux/IAA16; GF treatment exhibited the opposite regulatory pattern. These results indicate that BF and GF treatment influence seedling growth by modulating the expression of auxin-responsive gene networks. The study provides important theoretical foundations for genetic breeding, cultivation management, and high-altitude introduction of poplars.

Methods

Plant material and treatment

P. schneideri were selected in the natural forest on Litang (E 100°22’35’’, N 29°45’28’’), Litang County, Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China. P. schneideri cuttings were grown in an intelligent greenhouse at Southwest Forestry University after being acquired from the asexual line breeding nursery. The cuttings were planted in 20 cm diameter seedling pots with a substrate of field red soil: grass charcoal: humus = 1: 2: 1.

The arches covered with various colored films were situated in the arboretum of Southwest Forestry University. The films were blue, green, and colorless transparent film, respectively, with a film thickness of 0.1 mm, purchased from Jinan Yongfa Plastic Factory, and were oriented east-west. To maintain the consistency of light brightness and quality, new films were substituted for the blue and green ones every 20 days. One arbor was constructed for each color film as one treatment, 3 pots of cuttings of the same asexual line were placed under each treatment, and three replications were set up for each treatment, for a total of 9 pots. Three asexual lines were used as three biological replications. The material numbered BF is treated with a blue film, GF with a green film, and WF with a colorless transparent film.

In-shed transmission spectrometry

The transmission spectrum ratio components were measured in three arbors at 2 h intervals between 8:00 and 18:00 using the HR-550 Plant Wisdom Spectrometer (bought from Taiwan HiPoint corporation). At each time point, three measurements were made, and the daily average value for every shed was taken to determine the transmission spectral ratio.

Measurement of phenotypic indicators

The growth indexes of P. schneideri were measured after 60 d of growth under different film treatments. The main branch length (seedling height) and ground diameter (thickness) of P. schneideri under various treatments were measured with a tape measure and vernier caliper. The leaf length of the fifth leaf, measured from the top down at the tip of the main stem of selected seedlings, was also measured.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and RNA-Seq analysis

The leaves of P. schneideri under different treatments were used as materials, with three replicates for each treatment, totaling nine samples. It was then ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen, and the total amount of RNA was extracted using the RNAprep pure plant kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). A spectrophotometer at A260/280 (K5800C; KAIAO, Beijing, China) was utilized for measuring the RNA concentration, and the integrity was assessed with an Agilent 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The construction of complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries was carried out using the qualified RNA samples. On the Illumina platform, each library generated about 6 gigabases (Gb) of raw data. Clean Data was obtained by removing reads containing splices and low quality and performing sequencing quality control, and the percentage of Q30 bases was not less than 93.04% for all samples. The filtered reads were compared to the P. yunnanensis reference genome (PRJNA886471) using HISAT2 software [55]. The reads in the results were assembled and quantitatively analyzed using StringTie comparison [56]. Based on the length of the genes, the FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) value of each gene was calculated and differential expression analysis between samples was performed using edgeR [57]. The screening criteria were Fold Change ≥ 1.5 and P value < 0.01. The screened differential genes were compared with the homologous gene populations in the COG database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/) to achieve functional classification and annotation of the genes. Further GO and KEGG analyses were performed on the differential genes, GO enrichment analysis using the GOseq R package [58] and KEGG enrichment analysis using KOBAS 2.0 [59], respectively, and the calculated P values were corrected such that q value ≤ 0.5 was regarded as significantly enriched, in addition to the identification of transcription factors in the differential genes using PlantTFDB.

qRT-PCR verification

To validate the results of the expression profiling obtained by RNA-seq, qRT-PCR was performed to verify the chosen DEGs. The total RNA isolation RNAprep pure plant kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China, DP441) was employed to extract RNA from leaves of P. schneideri. The RNA was checked using K5800C (KAIAO, Beijing, China) and the qualified RNA was used for 1 st strand cDNA synthesis using Hifair® III Reverse Transcriptase (YEASEN, Shanghai, China). The primer pairs for real-time PCR based on the CDS sequences using NCBI primer BLAST (Table S6) and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The internal reference gene was PED1 (histone) [60]. qRT-PCR was executed with the Hieff UNICON® Universal Blue qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (YEASEN, Shanghai, China) using a LightCycler® 96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Roche, Hercules, Switzerland). A total volume of 20 µL contained 10 µL of Blue qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix, 2 µL of cDNA samples, 0.4 µL of each primer (1 µM), and 7.2 µL of ddH2O. The PCR thermal cycle conditions were: 95℃ for 2 min, 35 cycles at 95℃ for 10 s and at 60℃ for 30 s. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method [61]. The experiments were performed using triplicate technological repeats.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 26.0 software (IBM, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the means of the various treatments at the 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels. Where P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 are denoted by lowercase letters and uppercase letters, respectively. GraphPad Prism 8.0 and Excel were used for graphs and tables, respectively.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- BF

Blue film

- GF

Green film

- WF

The material numbered WF is treated with a colorless transparent film

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- COG

Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins

- GO

Gene ontology

- KEGG

The Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped transcripts

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

Author contributions

XZ and RX conceived the experiments and organized the manuscript; CW performed the experiments; SM analyzed the data; YX revised the manuscript; DZ original edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Talents Special Project of Yunnan Province “Xingdian Talents Support Program” (XDYC-QNRC-2022-0232) and the Joint Agricultural Project of Yunnan Province (202101BD070001-127).

Data availability

Raw sequencing data files are available in the NCBI GEO database with project accession GSE269248.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We collected P. schneideri species with permission from Southwest Forestry University. The IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Endangered Species and the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) both approved the acquisition and use of plant specimens for this study. The study did not receive ethical approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rong Xu and Xiaolin Zhang contributed equally.

References

- 1.Landi M, Zivcak M, Sytar O, Brestic M, Allakhverdiev S. (2020). Plasticity of photosynthetic processes and the accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants in response to monochromatic light environments: A review. Biochimica et biophysica acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 1861(2): 148131. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2019.148131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lazzarin M, Meisenburg M, Meijer D, Leperen W, Marcelis LF, Kappers IK, Krol AR, Loon JJ, Dicke M. LEDs make it resilient: effects on plant growth and defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2021;26(5):496–508. 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franklin KA. Light and temperature signal crosstalk in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biology. 2009;12(1):63–8. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsend AJ, Retkute R, Chinnathambi K, Randall J, Foulkes J, Carmo SE, Murchie EH. Suboptimal acclimation of photosynthesis to light in wheat canopies. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(2):1233–46. 10.1104/pp.17.01213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang LY, Wang LT, Ma JH, Ma ED, Li JY, Gong M. Effects of light quality on growth and development photosynthetic characteristics and content of carbohydrates in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) plants. Photosynthetica. 2017;55:467–77. 10.1007/s11099-016-0668-x. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CY, Chang CH, Wu CH, Tu YT, Wu KQ. Arabidopsis cyclin-dependent kinase C2 interacts with HDA15 and is involved in far-red light-mediated hypocotyl cell elongation. Plant J. 2022;112(6):1462–72. 10.1111/tpj.16027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuo ZC, Meng YY, Yu XH, Zhang ZL, Feng DS, Sun SF, Liu B, Lin CT. A study of the blue-light-dependent phosphorylation, degradation, and photobody formation of Arabidopsis CRY2. Mol Plant. 2012;5(3):726–33. 10.1093/mp/sss007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye SY, Shao QS, Xu MJ, Li SL, Wu M, Tan X. Effects of light quality on morphology, enzyme activities, and bioactive compound contents in Anoectochilus Roxburghii. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:857. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Goldthwaite JJ, Bristol JC, Gentile AC, Klein RM. Ligh-suppressed germination of California poppy seed. Can J Bot. 1971;49(9):1655–9. 10.1139/b71-233. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouly JP, Schleicher E, Dionisio-Sese M, Vandenbussche F, Straeten DVD, Bakrim N, Meier S, Batschauer A, Galland P, Bittl R, Ahmad M. Cryptochrome blue light photoreceptors are activated through interconversion of flavin redox States. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9383–91. 10.1074/jbc.M609842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith HL, McAusland L, Murchie EH. Don’t ignore the green light: exploring diverse roles in plant processes. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(9):2099–110. 10.1093/jxb/erx098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folta KM. Green light stimulates early stem elongation, antagonizing light-mediated growth Inhibition. Plant Physiol. 2004;135(3):1407–16. 10.1104/pp.104.038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhen SY, Haidekker M, Iersel MW. Far-red light enhances photochemical efficiency in a wavelength-dependent manner. Physiol Plant. 2019;167(1):21–33. 10.1111/ppl.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battle MW, Vegliani F, Jones MA. Shades of green: untying the knots of green photoperception. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(19):5764–70. 10.1093/jxb/eraa312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang WH, Park JS, Park KS, Son JE. (2016). Leaf photosynthesis rate, growth, and morphology of lettuce under different fractions of red, blue, and green light from light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Horticulture, environment, and biotechnology. 57: 573–9. 10.1007/s13580-016-0093-x

- 16.Gelderen K, Kang C, Paalman R, Keuskamp D, Hayes S, Pieril R. Far-red light detection in the shoot regulates lateral root development through the HY5 transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2018;30(1):101–16. 10.1105/tpc.17.00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Zhang LB, Chen P, Liang T, Li X, Liu HT. UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 interacts with MYB73/MYB77 to regulate auxin responses and lateral root development. EMBO J. 2020;39(2):e101928. 10.15252/embj.2019101928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sassi M, Wang J, Ruberti I, Vernoux T, Xu J. Shedding light on auxin movement: light-regulation of Polar auxin transport in the photocontrol of plant development. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8(3):e23355. 10.4161/psb.23355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dharmasiri N, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005;435(7041):441–5. 10.1038/nature03543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu ZP, Zhang F, Friml J, Ding ZJ. Auxin signaling: research advances over the past 30 years. J Integr Plant Biol. 2022;64(2):371–92. 10.1111/jipb.13225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi LL, Kwiatkowski M, Chen HH, Hoermayer L, Sinclair S, Zou MX, Genio CD, Kubeš M, Napier R, Jaworski K, Friml F. Adenylate cyclase activity of TIR1/AFB auxin receptors in plants. Nature. 2022;611(7934):133–8. 10.1038/s41586-022-05369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu F, He SB, Zhang JY, Mao ZL, Wang WX, Li T, Hua J, Du SS, Xu PB, Li L, Lian HL, Yang HQ. Photoactivated CRY1 and PhyB interact directly with AUX/IAA proteins to inhibit auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2018;11(4):523–41. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang CW, Xie FM, Jiang YP, Li Z, Huang X, Li L. Phytochrome A negatively regulates the shade avoidance response by increasing auxin/indole acidic acid protein stability. Dev Cell. 2018;44(1):29–41. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staswick PE, Tiryaki I, Rowe ML. Jasmonate response locus JAR1 and several related Arabidopsis genes encode enzymes of the firefly luciferase superfamily that show activity on jasmonic, salicylic, and indole-3-acetic acids in an assay for adenylation. Plant Cell. 2002;14(6):1405–15. 10.1105/tpc.000885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JG, Chen CH, Chien CT, Hsieh HL. FAR-RED INSENSITIVE219 modulates CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 activity via physical interaction to regulate hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(2):631–46. 10.1104/pp.111.177667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HJ, Fu TY, Yang SL, Hsieh HL. FIN219/JAR1 and cryptochrome1 antagonize each other to modulate photomorphogenesis under blue light in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(8):e1007606. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao YH, Zeng ZX, Zhang XL, Xie DX, Li X, Liu MLB M. Q., and, Liu HT. Green means go: green light promotes hypocotyl elongation via brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Cell. 2023;35(5):1304–17. 10.1093/plcell/koad022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian FM, Mi QH, Tayirjan A, Wei M, Wang XF, Yang FJ, Li Y. Effects of different color films on facility environment and growth, development, yield and quality of Sweer pepper. Shandong Agricultural Sci. 2013;45(12):35–9. 10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2013.12.034. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu ZL, Wu GX, Zhu S, Yu N, Mi QH, Ai XZ. Effect of colour plastic film on yield and quality of summer-autumn cucumbers in plastic greenhouse. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-occidentalis Sinica. 2015;24(1):109–14. 10.7606/j.issn.1004-1389.2015.01.019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia C, Gu YJ, He CZ, Zhou AP, and Luo J. X. Growth characteristics of five native poplars in Western Sichuan plateau. J Northwest F Univ. 2017;45(2):79–87. 10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2017.02.012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zong D, Gan PH, Zhou AP, Zhang Y, Zou XL, Duan AA, Song Y, He CZ. Plastome sequences help to resolve deep-level relationships of Populus in the family salicaceae. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:5. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao QZ, Dong MY, Li MF, Jin L, Pare PW. Light-induced flavonoid biosynthesis in Sinopodophyllum hexandrum with high-altitude adaptation. Plants. 2023;12(3):575. 10.3390/plants12030575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaborowska J, Labiszak B, Perry A, Cavers S, Wachowiak W. Candidate genes for the high-altitude adaptations of two mountain pine taxa. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3477. 10.3390/ijms22073477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramírez JV, Venn SE. Seeds and seedlings in a changing world: a systematic review and meta-analysis from high altitude and high latitude ecosystems. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(4):768. 10.3390/plants10040768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan JA, Shirasu K, Deng XW. The diverse roles of ubiquitin and the 26S proteasome in the life of plants. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4(12):948–58. 10.1038/nrg1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li W, Liu SW, Ma JJ, Liu HM, Han FX, Li Y, Niu SH. Gibberellin signaling is required for far-red light-induced shoot elongation in Pinus tabuliformis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2020;182(1):658–68. 10.1104/pp.19.00954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muneer S, Kim EJ, Park JS, Lee JH. Influence of green, red and blue light emitting diodes on multiprotein complex proteins and photosynthetic activity under different light intensities in lettuce leaves (Lactuca sativa L). Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(3):4657–70. 10.3390/ijms15034657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei XX, Wang WT, Xu P, Wang WX, Guo TT, Kou S, Liu MQ, Niu YK, Yang HQ, Mao ZK. Phytochrome B interacts with SSWC6 and ARP6 to regulate H2A.Z deposition and photomorphogensis in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2021;63(6):1133–46. 10.1111/jipb.13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li HM, Tang CM, Xu ZG. The effects of different light qualities on rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) plantlet growth and morphogenesis in vitro. Sci Hort. 2013;150:117–24. 10.1016/j.scienta.2012.10.009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen SZ, Fan XC, Song MF, Yao ST, Liu T, Ding WS, Liu L, Zhang ML, Zhan WM, Yan L, Sun GH, Li HD, Wang L, Zhang J, Jia K, Yang XL Q. H., and, Yang JP. Cryptochrome 1b represses Gibberellin signaling to enhance lodging resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2024;194(2):902–17. 10.1093/plphys/kiad546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nie WF, Li Y, Chen Y, Zhou Y, Yu T, Zhou YH, Yang YX. Spectral light quality regulates the morphogenesis, architecture, and flowering in pepper (Capsicum annuum L). J Photochem Photobiol B. 2023;241:112673. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2023.112673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong M, Zeng BJ, Tang DY, Yang JX, Qu LN, Yan JD, Wang XC, Li X, Liu XM, Zhao XY. The blue light receptor CRY1 interacts with GID1 and DELLA proteins to repress GA signaling during photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2021;14:1328–42. 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen PJ, Hangarter RP, Estelle M. Auxin transport is required for hypocotyl elongation in light-grown but not dark-grown Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(2):455–62. 10.1104/pp.116.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wit MD, Galvao VC, Fankhauser C. Light-mediated hormonal regulation of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2016;67:513–37. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang JY, Wang HY, Deng T, Liu Z, Wang XW. Time-coursed transcriptome analysis identifies key expressional regulation in growth cessation and dormancy induced by short days in Paulownia. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16602. 10.1038/s41598-019-53283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang F, Zhang LY, Chen XX, Wu XD, Xiang X, Zhou J, Xia XJ, Shi K, Yu JQ, Foyer CH, Zhou YH. SlHY5 integrates temperature, light, and hormone signaling to balance plant growth and cold tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2019;179(2):749–60. 10.1104/pp.18.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Zhang SH, Fu YP, He TT, Wang XW. Analysis of dynamic global transcriptional atlas reveals common regulatory networks of hormones and photosynthesis across Nicotiana varieties in response to long-term drought. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:672. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurepin L, Emery RN, Pharis RP, Reid DM. Uncoupling light quality from light irradiance effects in Helianthus annuus shoots: putative roles for plant hormones in leaf and internode growth. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(8):2145–57. 10.1093/jxb/erm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Wu GX, Zhao BB, Wang BB, Lang ZH, Zhang CYM, Wang HY. Regulatory modules controlling early shade avoidance response in maize seedlings. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:269. 10.1186/s12864-016-2593-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma L, Li G. Auxin-dependent cell elongation during the shade avoidance response. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:914. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi S. Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:225–51. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abbas N, Maurya JP, Senapati D, Gangappa SN, Chattopadhyay S. Arabidopsis CAM7 and HY5 physically interact and directly bind to the HY5 promoter to regulate its expression and thereby promote photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1036–52. 10.1105/tpc.113.122515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibout R, Sukumar P, Hettiarachchi C, Holm M, Muday GK, Hardtke CS. Opposite root growth phenotypes of hy5 versus hy5 hyh mutants correlate with increased constitutive auxin signaling. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(11):e202. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao ZL, He SB, Xu F, Wei XX, Jiang L, Liu Y, Wang WX, Li T, Xu PB, Du SS, Li L, Lian HL, Guo TT, Yang HQ. Photoexcited CRY1 and PhyB interact directly with ARF6 and ARF8 to regulate their DNA-binding activity and auxin-induced hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2020;225(2):848–65. 10.1111/nph.16194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. Stringtie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):290–5. 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26, 139–140. doi: 0.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R14. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mao XZ, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, and Wei L. P. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(19):3787–93. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yun T, Li J, Zu Y, Zhou AP, Zong D, Wang S, Li D, He CZ. Selection of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in the bark of Populus yunnanensis cuttings. J Environ Biol. 2019;40(3SI):584–91. 10.22438/jeb/40/3(SI)/Sp-24. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shuai P, Liang D, Tang S, Zhang ZJ, Ye CY, Su YY, Xia XL, Yin WL. Genome-wide identification and functional prediction of novel and drought-responsive LincRNAs in Populus trichocarpa. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:4975–83. 10.1093/jxb/eru256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing data files are available in the NCBI GEO database with project accession GSE269248.