Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been extensively studied for its associations with autoimmune disorders, various cancers, and neurological diseases. Emerging evidence also links EBV to behavioral and neurophysiological disruptions, potentially mediated through interactions with host’s immune and circadian systems. In this study, we investigated the effects of EBV and its DNA on the behavior of Drosophila melanogaster by examining its lifespan, activity, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Both EBV viral particles and EBV DNA showed distinct effects in terms of behavior and survival. Circadian function analysis showed disruptions in several circadian parameters in EBV-injected flies, whereas EBV DNA-injected flies displayed defects in sleep behavior. Our findings suggest that EBV may impact circadian mechanisms, thereby enhancing our understanding of the effects of viral infections on circadian and behavioral systems and establishing Drosophila as a valuable model for future studies on EBV and host physiology.

Keywords: Circadian rhythms, Drosophila melanogaster, EBV DNA, EBV viral particles, Behavioral disruptions

Introduction

Human Herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), is a Gammaherpesvirus belonging to the Herpesviridae family [1]. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric symptoms have been associated with EBV infection. For instance, a 2012 study published in Psychosomatic Medicine reported that individuals with elevated levels of EBV antibodies were more likely to experience depressive symptoms [2, 3]. However, this does not confirm a causal relationship, and further research is necessary to fully understand this link. More recent studies suggest that EBV may be a risk factor for multiple sclerosis (MS), a neurological condition that can result in various behavioral and cognitive impairments [4]. EBV infection is more prevalent among individuals with multiple sclerosis [5]. One study found EBV viral load in all MS patients, and a cohort analysis of nearly 10 million young adults in active service, 955 of whom were diagnosed with MS, revealed that EBV infection increased the risk of MS by 32-fold [5, 6]. In contrast, other viruses like cytomegalovirus did not show a similar effect. The severity of the initial EBV infection also appears to correlate with MS onset [7], and longitudinal studies indicate that MS progression increases thirtyfold following EBV infection [8]. Moreover, MS has been linked to a broader repertoire of EBV-specific T-cell receptors (TCRs), suggesting ongoing immune responses [9]. Additionally, myalgic encephalomyelitis, another name for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) has been linked to EBV. Although evidence remains limited, EBV is considered a potential trigger for CFS, with studies showing elevated levels of the EGR gene and EBV-induced gene 2 (EBVI2) in CFS patients, both key to EBV transcription, reactivation, and B cell transformation [10]. Furthermore, the mechanisms of EBV evasion in CFS patients were linked to altered cellular immunity and an elevated Th2 response [11]. After infectious mononucleosis (IM), a clinical entity characterized by sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and fever [12], individuals developed CFS after an acute EBV infection, the CEBA research revealed evidence of T cell activation and low-grade chronic inflammation [13]. The processes behind any possible associations between EBV and behavioral changes remain unclear. Drosophila Melanogaster serves as a reliable model for behavioral research due to the similarities between its brain structures and neurotransmitter systems and those of mammals. Research has shed light on basic mechanisms that affect human behavior and neurological problems, including circadian rhythms, sleep control, learning, memory, aggressiveness, and social interaction. The fly’s distinct 24-hour circadian clock and sleep architecture make it ideal for investigating sleep disorders and chronobiological disruptions [14]. Previously, we demonstrated that injecting flies with 70 copies of EBV DNA increased the expression of the antimicrobial peptide Diptericin through activation of the IMD pathway. EBV DNA-injected flies also showed elevated hemocyte counts [15]. Additionally, we have demonstrated that the generation of gastrointestinal inflammation in fruit flies also triggers the IMD pathway, pointing to a potential immunostimulatory function of EBV DNA in aggravating, the related inflammatory phenotypes [16]. There is growing recognition that circadian rhythms and sleep behaviors in Drosophila are modulated by both environmental cues such as light-dark (LD) cycles and intrinsic factors like aging. Studies have shown that LD cycles can entrain circadian rhythms, while continuous darkness (DD) challenges the endogenous circadian machinery, often revealing subtle deficits in clock function [14, 17]. Moreover, aging alters circadian patterns in flies, including changes in activity rhythms, sleep fragmentation, and reduced clock gene expression [18, 19]. In addition, several studies have documented that immune challenges can significantly influence sleep in Drosophila. For example, injection of bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or peptidoglycan (PGN) can induce sleep-like behavior, interpreted as part of an adaptive response to infection [20, 21]. These findings suggest a tight integration between immune status and sleep-regulating circuits. In this study, we opted to assess any behavioral alterations in fruit flies upon EBV viral particle or EBV DNA injection. We particularly assessed sleep, activity, and motor function to evaluate alterations in fruit flies’ circadian rhythms upon EBV-induced challenge.

Materials and methods

Cell passage and EBV induction

The P3HR-1 cell line infected with the latent EBV type 2 strain (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, Maryland) is a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line. These cells are maintained in RPMI, Rosewell Park Memorial Institute, with 20% FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS) from Lonza. Incubation was done at 37 °C in a humidified Thermo Scientific incubator with 5% CO2. Regular passaging was performed to keep the cells at 70% confluency (every 5 days) by withdrawing 1 mL of the previous plate to a new one containing 9 mL of fresh RPMI complete media. The phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stock provided by Sigma-Aldrich had to be dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to add to the cultured cells 65 ng/mL of PMA. Five days following induction, the cells were centrifuged for 8 min at 800 rpm at room temperature in a 50 mL conical. Following that, the supernatant containing the virus was collected and centrifuged for 1 h 30 min at 16,000 xg at 4 °C in a fixed angle rotor in a Thermo Scientific centrifuge. The viral pellet was suspended in 2 mL RPMI complete media and stored at -80 °C.

DNA extraction

To extract the viral DNA, 2 mL of phenol were added (equal volume as RPMI media) followed by a few seconds vortex. The whole volume was distributed in Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper aqueous phase containing the viral DNA was transferred to another Eppendorf tube with a maximum volume of 200 µL. Then, 3 M sodium acetate was added (1/10th of the collected aqueous phase volume) followed by the addition of 100% ethanol, 3 times the supernatants volume. Samples were stored overnight at -80 °C to precipitate the DNA. Afterward, samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The DNA pellet obtained is washed twice by the addition of 1 mL of 70% ethanol, centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and discarding the supernatant each time. Finally, the DNA pellet was left to air-dry for a maximum of 5 min and resuspended in 30 µL of nuclease-free water. DNA samples were placed overnight at 4 °C. DNA concentration was quantified using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR)

The quantification of EBV DNA copies was conducted using the Bio-Rad CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System and Taq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA). Primers targeting the EBV-encoded small RNA 2 (EBER-2) gene were obtained from Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea), with the following sequences:

Forward primer: 5’-CCCTAGTGGTTTCGGACACA-3’.

Reverse Primer: 5’-ACTTGCAAATGCTCTAGGCG-3’.

Each 10 µL qPCR reaction contained 4 µL SYBR Green mix, 3 µL nuclease-free water, 1 µL sample DNA, and 1 µL each of the forward and reverse primers (7.5 pmol/µL, prepared from a 100 pmol/µL stock). The thermal cycling program included an initial activation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation and annealing at 58 °C for 15 and 30 s, respectively. A standard curve was created using known concentrations of EBV DNA control (1000, 2000, 5000, 10,000, and 54,000 copies/reaction; Amplirun Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Control, Vircell S.L., Granada, Spain). A valid standard curve had a slope between − 3.0 and − 3.6 and a correlation coefficient of at least 0.98. Cq values were used to determine EBV copy numbers in the samples.

Fly stocks

Wild type W1118 flies were raised at 25 °C (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center #3605) and used for the experiments. One-day-old adult flies were injected with various treatments of EBV DNA and EBV viral particles.

Fly injection

To assess behavioral changes, one-day-old flies were injected with 70 copies of EBV DNA or 70 copies of EBV viral particles using a Nanoliter 2020 injector equipped with a glass capillary (1.14 mm, 3.5) needle. The glass capillary needle used for injections was softened with a flame and pulled to a fine, sharp tip under a microscope to ensure precision and minimize damage to the flies during the procedure. Injections were performed into the thorax of CO₂-anesthetized flies. Each fly received 55.2 nL of solution. Negative controls included flies injected with either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or sterile water.

Activity, sleep, and survival analysis of EBV virus/DNA injected flies using the drosophila activity monitor system DAM

Daily activity and sleep patterns of both control and injected flies were recorded using the Drosophila Activity Monitor (DAM) system. Individual male flies were placed into glass activity tubes containing 5% sucrose and 2% agarose, with a black lid at one end and a cotton plug at the other. Although the 5% sucrose diet is commonly used in short-term behavioral and circadian studies, it has also been applied in longer-term experiments, including lifespan and stress assays [22, 23]; nevertheless, its nutritional limitations may influence longevity outcomes, we acknowledge that it is a nutritionally imbalanced diet, lacking proteins, lipids, and micronutrients, which can impact overall vitality and longevity. Because female flies are prone to laying eggs, which might interfere with the infrared beam detection and result in erroneous activity and sleep data, previous research has shown that the Drosophila Activity Monitor (DAM) system is predominantly used with male flies [24]. One male fly from each batch (injected or not) was placed into each activity tube. The tubes were inserted into monitors, each representing a batch. The experiment was conducted for 30 days, during which time the activity monitors were linked to a data-gathering system. The DAM system was maintained on a cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of dark, with a temperature of 25 °C and humidity levels above 60%. Every tube was inserted into a channel where a beam of infrared light senses the fly’s movement. The data is saved as the activity of each fly every five minutes using Trikinetics data collection software (DAMSystem308, Trikinetics Inc.). The flies’ activity, sleep duration, and survival were examined, with 5 min of inactivity regarded as sleep and over 24 h as death. Over 30 days, data analysis was done on the live flies. All flies were included in the analysis unless they exhibited no activity within the first 4–5 days, following standard Drosophila Activity Monitoring (DAM) system protocols [25, 26]. This step is necessary to ensure data accuracy, as inactive flies could result from early mortality, injury, or technical issues, rather than biological effects of the treatment. GraphPad Prism (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel were used for data calculation and statistical analysis.

Circadian and rhythmicity analysis of EBV virus/DNA injected flies

Following previously published research (Chiu et al., 2010), the LD/DD experiment was conducted. Adult male flies were first entrained for 5 days in a regular light: dark cycle. On the final day (LD5), the light parameters were turned off, and the flies were then conditioned in a completely dark environment for 9 days. A Microsoft Excel macro was used to analyze the raw data, where 5 min of inactivity were accounted for as sleep and more than 24 h of immobility as a death event. Using data from all animals, the activity and sleep characteristics were averaged for each day of the experiment and are shown throughout. According to previously published work [27], the anticipated activity was calculated by quantifying the activity in the 6 h before lights-on or light-off. ActogramJ 1.0 (https://bene51.github.io/ActogramJ/index.html) and ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) were used to create Actogram activity profile charts and to produce the Chi-square periodogram for each fly, allowing for the computation of the rhythmicity power value and the proportion of rhythmic flies. For all statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism 8.4.2 was used. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for data with no normal distribution.

Results

EBV DNA and viral particles reduce lifespan and activity and alter sleep patterns in flies

Flies injected with EBV DNA exhibited a significant decrease in lifespan, with a median survival of 19 days compared to 22 days for sterile water-injected flies (p = 0.0235) and 24 days for EBV viral particle-injected flies (p = 0.0242). Although flies injected with EBV viral particles also showed a reduced lifespan (median survival = 24 days), the difference was not statistically significant when compared to PBS-injected controls (median survival = 27 days, p = 0.0618) (Fig. 1a). These findings suggest that EBV DNA has a more pronounced effect on reducing lifespan than EBV viral particles.

Fig. 1.

Lifespan, activity, and sleep plots of male W1118 injected either with EBV DNA or with 70 EBV particles. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of male W1118 injected either with Sterile Water (n = 28), EBV DNA (n = 31), PBS (n = 32) or 70 EBV viral particles (n = 22). Outliers from each group were determined, and statistical significance was analyzed by the Mantel- Haenszel test. ns: p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. (b) Representative plotted average fly activity profiles of males over 30 days. For each group, the locomotor activity levels of male flies were measured in 5-minute bins and then averaged to obtain a representative 24-hour activity profile. (c) Activity profile graph representing the average activity over 30 days, measured every 5 min. Drosophila melanogaster generally exhibits two activity bouts: one centered on ZT0 (morning peak) and the second around ZT12 (evening peak). (d) Average activity of the male flies over 24 h intervals using Kruskal-Wallis. (e) Sleep profile graph representing the percentage of flies engaged in sleep measured every 5 min over a 24 h period. ZT0 indicates the morning peak and ZT12 the evening peak. (f) Average sleep (minutes) of the flies over 24 h intervals. (g) Number of sleep bouts calculated during 24 h of spontaneous sleep. Kruskal-Wallis was used to determine the significance between groups. (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 31, control PBS injected W1118: ♂n = 32; EBV 70 viral particles injected W1118: ♂n = 22.). Error bars represent standard deviation

Under light/dark conditions, Drosophila typically display a bimodal activity pattern, with peaks at the morning transition (ZT0) and the evening transition (ZT12), separated by a midday rest period or “siesta.” Circadian analysis revealed that both EBV DNA and EBV viral particle injections resulted in diminished locomotor activity, particularly during the anticipation phases before light-to-dark and dark-to-light transitions. Flies injected with EBV viral particles showed the lowest activity levels at ZT0, while those injected with EBV DNA exhibited a noticeable decline in activity before ZT12 (Fig. 1b, c). Overall, the mean daily activity was significantly reduced in both experimental groups compared to controls, with the most pronounced decrease observed in EBV viral particle-injected flies compared to PBS-injected controls (mean = 217.477 vs. 408.555, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1d).

Alongside locomotor disruptions, sleep behaviors were also disrupted. Flies injected with EBV viral particles exhibited a significant increase in total daily sleep duration compared to PBS-injected flies (mean = 1236.59 min vs. 1087.16 min, p < 0.0001), whereas no significant differences were observed between EBV DNA-injected and sterile water-injected flies (Fig. 1e,f). The increased sleep observed in EBV viral particle-injected flies was accompanied by a decrease in sleep fragmentation, indicating by a reduced number of sleep bouts per 24-hour period (mean = 12.22 bouts) compared to PBS-injected flies (mean = 25.45 bouts, p < 0.0001). In contrast, EBV DNA-injected flies did not show significant differences in sleep fragmentation compared to sterile water-injected controls (Fig. 1g).

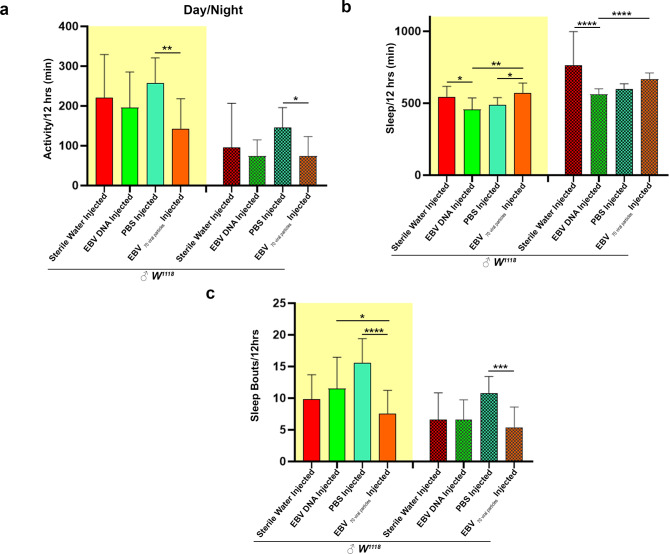

Day-night behavioral disruptions in EBV DNA and EBV viral injected flies

Engaging in day-night analysis provides a comprehensive examination of the behavioral variations exhibited by these fruit flies, offering invaluable insights into their sleep-wake cycles and responses to environmental cues throughout the day [28]. EBV viral particle injections resulted in a significant reduction in mean daily activity, with the effects being more pronounced in the EBV viral particle group during the day. While no significant differences were observed between EBV DNA and sterile water-injected flies (mean = 195 vs. 221 min during the day; mean = 73 vs. 96 min during the night), EBV viral particle-injected flies showed a sharp decrease in activity compared to PBS-injected flies (mean = 143.177 vs. 257.031 min, p = 0.0016 during the day; mean = 145 vs. 74.3 min, p = 0.0398 during the night) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Day-night dynamics of EBV DNA and EBV particles injected in Drosophila melanogaster. Average locomotor activity of the male flies over 12-hour intervals (day: light on, night: light off). (b) Average of daily sleep minutes for all flies over 12 h intervals over 30 days. (c) Number of sleep bouts was calculated during the day (lights on) and night-time (lights off). Statistical analysis performed using Kruskal-Wallis * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. (Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 31; control PBS injected W1118: ♂n = 32; EBV 70 viral particles injected W1118: ♂n = 22)

Sleep patterns differed between the two groups with an increase in sleep counts per min for EBV viral particles compared to EBV DNA (p value = 0.049 and p value < 0.0001 during day and night, respectively). EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited a significant reduction in sleep during both the day and night compared to sterile water-injected flies (p value = 0.0428 and p value < 0.0001 during day and night, respectively), whereas EBV viral particle-injected flies showed a significant increase in sleep duration in comparison with PBS control (p = 0.027) (Fig. 2b). Rather than inadequate sampling, the observed variability is most likely the result of biological variation among individual flies. This threshold is exceeded by the roughly 30 flies per condition in our study, which offers a trustworthy dataset for examining patterns of activity and sleep. The number of sleep bouts was also higher in EBV DNA-injected flies compared to EBV viral particle-injected flies during the day (p = 0.00493). However, no significant differences were observed between EBV DNA and sterile water-injected flies in terms of sleep fragmentation. In contrast, EBV viral particle-injected flies exhibited significantly fewer sleep bouts compared to PBS-injected flies during both day (mean = 7.58485 vs. 15.5729, p < 0.0001) and night (mean = 5.41212 vs. 10.8167, p = 0.0002), suggesting a more consolidated sleep pattern (Fig. 2c). EBV DNA and EBV viral particles induce distinct yet overlapping disruptions in lifespan, locomotor activity, and sleep patterns in Drosophila. While EBV DNA significantly shortens lifespan and reduces activity, its effects on sleep are minimal. In contrast, EBV viral particles lead to pronounced locomotor suppression and a substantial increase in total sleep duration and are accompanied by improved sleep consolidation. These findings highlight the differential impacts of EBV DNA and viral particles on behavioral and physiological functions, warranting further investigation into their underlying mechanisms.

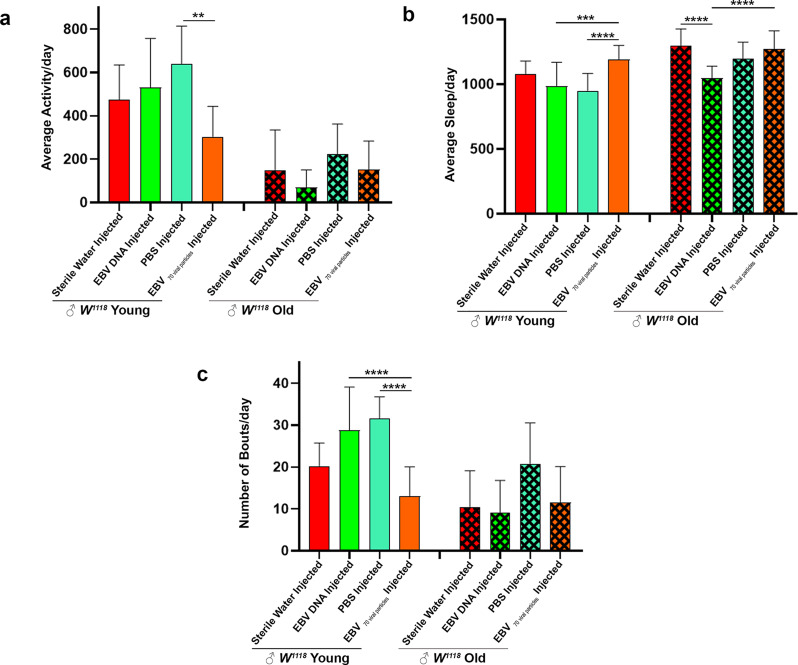

Age-dependent behavioral changes in EBV DNA and EBV viral particle-injected flies

Analyzing both young and old flies using the DAM is pivotal in uncovering age-related behavioral changes and patterns, shedding light on the dynamic interplay between aging and biological clock mechanisms; ‘young’ refers to 1–13 days old, and ‘old’ refers to 14–30 days old flies. The daily locomotor activity conducted in young versus old flies revealed remarkably different paradigms. EBV viral particle-injected young flies were notably less active than PBS-injected controls (mean = 303.126 min vs. 637.5 min, p = 0.0019) (Fig. 3a). These results suggest that EBV viral particles lead to a marked suppression of movement in young flies.

Fig. 3.

Comparative behavioral analysis between young and old EBV DNA or EBV particles injected Drosophila melanogaster. (a) Average activity of the male flies over 24 h intervals. (b) Average sleep (minutes) of the male flies over 24 h intervals. (c) Number of sleep bouts was calculated during 24 h of spontaneous sleep. The flies are subdivided into two groups in an age-dependent manner since locomotion is age-dependent: ‘young’ refers to 1–13 days old, and ‘old’ refers to 14–30 days old. Kruskal-Wallis was used * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 31, control PBS injected W1118: ♂n = 32; EBV 70 viral particles injected W1118: ♂n = 22)

Sleep patterns varied significantly between young and old flies across injected groups. EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited a substantially reduced sleep duration compared to EBV viral particle-injected flies in both young and old generations (p = 0.0002 and p < 0.0001 respectively). Specifically, in old EBV DNA-injected flies, sleep duration was significantly lower than in sterile water-injected controls (mean = 1045.57 min vs. 1297.09 min, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b). Further differences emerged in sleep fragmentation. Young EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited a significantly higher number of sleep bouts compared to EBV viral particle-injected flies (p < 0.0001). In contrast, EBV viral particle-injected flies showed fewer sleep bouts compared to PBS-injected controls in both young (p < 0.0001) and old (p = 0.0013) generations (Fig. 3c). Age plays a crucial role in how EBV DNA and EBV viral particles affect locomotor activity and sleep in Drosophila. While young EBV DNA-injected flies exhibit hyperactivity and fragmented sleep, older flies experience reduced sleep compared to controls. Conversely, EBV viral particles suppress locomotor activity in young flies while promoting longer and more consolidated sleep.

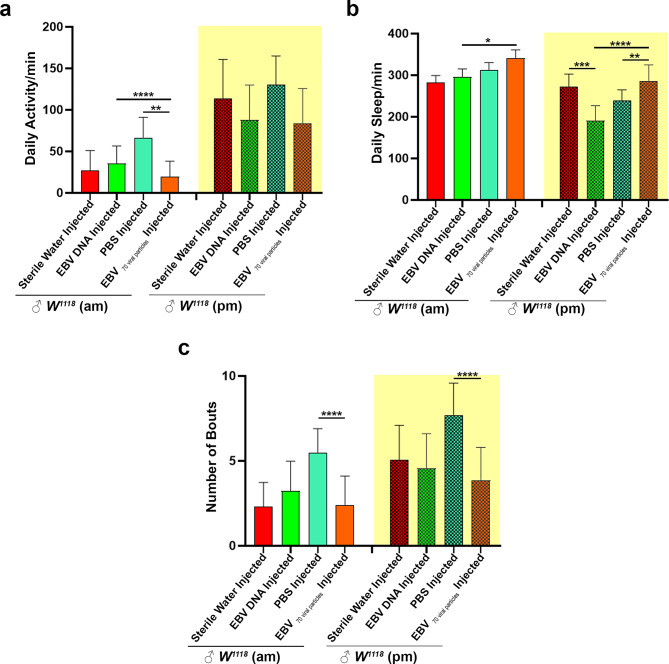

Reduced activity and increased sleep were detected in EBV DNA or EBV viral particle injected flies during anticipation

In this study, we explored the impact of EBV DNA and EBV viral particles on the anticipatory behaviors of Drosophila melanogaster, specifically during the anticipation phase, which refers to the heightened readiness or activity observed in response to environmental cues such as the scheduled turning on and off of lights. Our primary focus was to assess how these viral injections affected both activity and sleep profiles during the anticipation period, with an emphasis on the underlying regulatory or compensatory mechanisms that may be influenced by EBV exposure.

To evaluate the effects, we analyzed the behavior of the flies during the 6-hour anticipation phase, immediately before the scheduled light changes. Our results indicate that there were no significant differences between the EBV DNA and EBV viral particles groups, nor between EBV DNA and sterile water controls. However, when comparing the EBV viral particle group to its PBS-injected control group during the AM anticipation phase, a significant decrease in activity was observed in the EBV viral particle group (mean = 19.71 min) compared to the PBS group (mean = 66.67 min, p = 0.0012). In the PM phase, we observed lower activity in both the EBV DNA and EBV viral particles injected groups compared to the control groups. Specifically, EBV DNA injected flies exhibited reduced activity (mean = 87.87 min) compared to the sterile water group (mean = 113.75 min), and similarly, EBV viral particle injected flies had lower activity (mean = 84.12 min) compared to their PBS-injected control group (mean = 130.38 min) but not significant (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, the relationship between activity and sleep in Drosophila is not straightforward, as increased sleep does not necessarily correlate with decreased activity. The balance between activity and sleep is influenced by various factors, including circadian rhythms, environmental conditions, and the physiological state of the flies. During both the AM and PM phases, we noted a significantly higher sleep rate in the EBV viral particle group compared to the EBV DNA group (p = 0.0106 and p < 0.0001 respectively). Specifically, in the AM phase, EBV DNA-injected flies had a higher sleep rate (mean = 296.53 min) compared to their control group (mean = 282.97 min, p = 0.025). However, during the PM phase, EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited a significantly lower sleep rate (mean = 190.65 min) compared to the sterile water control group (mean = 296.53 min, p = 0.0001). The EBV viral particle injected flies demonstrated an increased sleep rate during both the AM and PM anticipation periods. In the AM phase, the sleep duration was higher in the EBV viral particles group (mean = 341.23 min) compared to the PBS control group (mean = 282.97 min). In the PM phase, EBV viral particle injected flies also had significantly higher sleep rates (mean = 286.51 min) compared to the PBS group (mean = 239.18 min, p = 0.0048) (Fig. 4b). Finally, when analyzing the number of sleep bouts, the EBV-injected groups exhibited fewer sleep bouts compared to the PBS control group. Specifically, EBV DNA and EBV viral particles injected flies had significantly fewer sleep bouts (mean = 2.38 and 3.86, respectively) compared to the PBS-injected W1118 control flies (mean = 5.48 and 7.71, respectively) during both the AM and PM phases (Fig. 4c). Our results suggest that EBV viral particles have a significant impact on the anticipatory behaviors of fruit flies, influencing both activity and sleep patterns, with notable differences observed between the AM and PM anticipation periods. These findings highlight the complex interactions between viral infection and circadian behavior, warranting further investigation into the underlying regulatory mechanisms at play.

Fig. 4.

EBV DNA or Viral Particles Disrupt Anticipation in Drosophila Melanogaster: Reduced Activity and Increased Sleep. (a) Mean average activity of the male flies during the anticipation phase: 6 h before the lights turn on (am) and 6 h before the lights turn off (pm). (b) Average sleep (min) of the flies. (c) Number of sleep bouts was calculated. Kruskal-Wallis was performed; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 31, control PBS injected W1118:♂n = 32; EBV 70 viral particles injected W1118: ♂n = 22

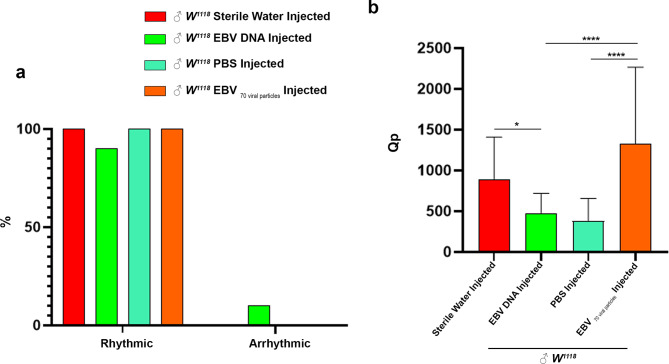

Arrhythmic behavioral patterns in EBV DNA-injected flies

Fruit flies that display regular peaks and troughs over 24 h and consistent, predictable patterns of activity and rest that correspond with their circadian rhythm are said to be rhythmic. Arrhythmic flies, on the other hand, don’t follow this regular pattern; instead, they exhibit erratic or sporadic periods of activity and rest, which suggests that their circadian clock mechanisms aren’t working properly.

Analysis over 30 days revealed that 10% of EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited arrhythmic behavioral patterns characterized by erratic, non-cyclic activity and rest periods (Fig. 5a). Rhythmicity strength, quantified as the power of rhythmicity (Qp), was significantly weaker in EBV DNA-injected flies compared to sterile water-injected controls (mean = 478.926 vs. 887.979, p = 0.0288). In contrast, EBV viral particle-injected flies displayed a significantly stronger rhythmic behavioral pattern than both PBS and EBV DNA-injected flies (mean = 1327.29 vs. 382.443 and 478.926, respectively, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5b). These findings suggest that EBV DNA disrupts circadian regulation, leading to erratic behavioral patterns, whereas EBV viral particles enhance rhythmicity strength, potentially reinforcing biological clock mechanisms. EBV DNA disrupts circadian rhythmicity in a subset of flies, leading to arrhythmic behavior, whereas EBV viral particles strengthen rhythmic patterns. These findings highlight the differential effects of EBV DNA and viral particles on age-dependent behavioral regulation.

Fig. 5.

Rhythmicity patterns in Drosophila melanogaster. (a) Representative graph of percentage of rhythmicity and arrhythmicity of male W1118 injected either with Sterile Water (n = 28), EBV DNA (n = 31), PBS (n = 32) or 70 EBV viral particles (n = 22). (b) Graph illustrating the Qp statistical value (rhythmicity power) of male flies. Kruskal-Wallis was performed * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 31, control PBS injected W1118:♂n = 32; EBV 70 viral particles injected W1118: ♂n = 22)

Activity and sleep disturbances in W1118 flies injected with EBV DNA or EBV viral particles under LD-DD conditions

Given the distinct behavioral phenotypes observed in W1118 flies injected with EBV DNA or EBV viral particles, we sought to investigate their role in regulating the endogenous circadian clock by analyzing activity and sleep patterns during the transition from light-dark (LD) to constant dark (DD) conditions (Fig. 6a,c). EBV DNA injected flies exhibited significant activity disruptions under LD conditions, with EBV DNA-injected flies displaying a lower mean activity compared to EBV viral particle-injected flies (mean = 294.655 min vs. 465.407 min, p = 0.028) (Fig. 6b). Upon shifting from LD to DD, EBV DNA-injected flies showed significantly reduced anticipation peaks before ZT0 (morning transition) and ZT12 (evening transition) compared to sterile water-injected controls, with a significant decrease in mean activity during LD (p = 0.0080). In contrast, EBV viral particle-injected flies lacked distinct anticipation peaks but did not show significant variations in activity levels compared to PBS-injected controls during the LD-DD transition (Fig. 6b,d). Sleep profiles differed significantly between EBV DNA and EBV viral particle-injected flies (Fig. 6e,h). EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited significantly higher mean sleep duration compared to both EBV viral particles (p = 0.0103 in LD and p = 0.0454 in DD) and sterile water-injected controls (mean = 1274.74 min vs. 982.536 min, p < 0.0001 in LD; p < 0.0001 in DD). EBV viral particle-injected flies exhibited a distinct sleep pattern, showing a significant reduction in sleep duration compared to PBS-injected controls (p = 0.0328) during LD conditions only (Fig. 6f,i). Sleep fragmentation, measured by sleep bout count, also varied significantly. During LD, a clear distinction was observed between EBV DNA and EBV viral particle-injected flies (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6g). EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited fewer sleep bouts compared to sterile water-injected controls (mean = 2.85172 vs. 28.2857, p < 0.0001 in LD; mean = 19.931 vs. 32.9643, p = 0.0005 in DD). In contrast, EBV viral particle-injected flies exhibited an increased number of sleep bouts compared to PBS-injected controls during LD (mean = 23.5379 vs. 13.0174, p = 0.0491) (Fig. 6j). These results suggest that EBV DNA disrupts sleep stability while EBV viral particles increase sleep fragmentation under LD conditions.

Fig. 6.

EBV DNA and EBV viral particles W1118 injected flies exhibit circadian activity and sleep disruptions. (a-c) Graph showing the average activity profile of all injected groups, with activity counts measured every 5 min over 24 h. By an average of 5 days under light/dark conditions (LD1-LD5) and 5 days under dark/dark conditions (DD1-DD5), respectively. Two activity bouts are centered: ZT0 (morning peak) and ZT12 (evening peak). (b-d) Mean locomotor activity per day of all injected groups obtained by averaging 5 days in light/dark conditions (LD1-LD5) and 5 days in dark/dark conditions (DD1-DD5).(e-h) Graph displaying the average sleep profile of all injected groups, with activity counts measured every 5 min over a 24-hour period by averaging over 5 days under light/dark conditions (LD1-LD5) and 5 days under dark/dark conditions (DD1-DD5).(f-i) Average sleep (minutes) of the flies over 24 h intervals during LD and DD periods. (g-j) Number of sleep bouts calculated during 24 h of spontaneous sleep during LD and DD periods. Kruskal-Wallis was performed as a statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005; **** p < 0.0001. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 29; control PBS injected W1118:♂n = 23; EBV 70 particles injected W1118: ♂n = 29). Error bars represent standard deviation

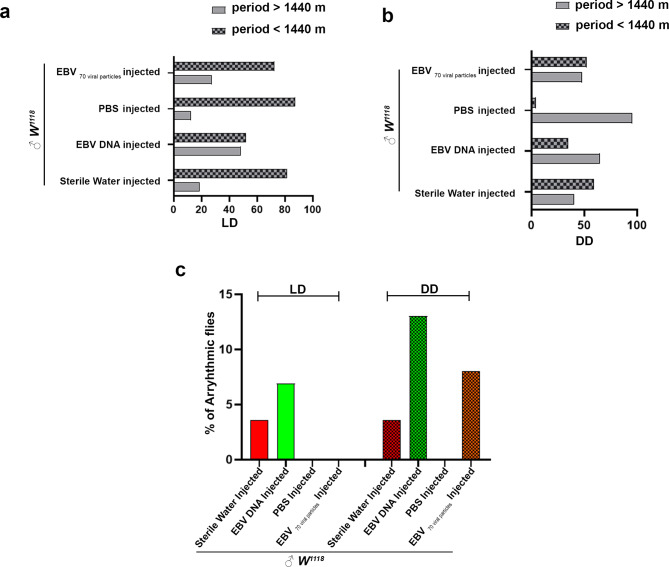

EBV DNA and EBV viral particles affect circadian function in flies

Under constant environmental conditions, organisms rely on their endogenous circadian rhythm, which follows a free-running cycle. In Drosophila melanogaster, this cycle is approximately 1440 min, and deviations from this period indicate potential circadian clock dysfunction. During the LD phase, both EBV DNA and EBV viral particle-injected flies exhibited a reduced free-running period compared to controls. A total of 51.19% of EBV DNA-injected flies had a free-running period exceeding 1440 min, compared to 81.48% of sterile water-injected controls. Similarly, 72.41% of EBV viral particle-injected flies had a prolonged free-running period, compared to 87.5% of PBS-injected controls (Fig. 7a). However, in the DD phase, these effects varied between the two groups. Only 35% of EBV DNA-injected flies maintained a free-running period above 1440 min, compared to 59.26% of sterile water-injected controls. In contrast, 52.17% of EBV viral particle-injected flies exhibited a prolonged free-running period, while only 4.35% of PBS-injected controls did (Fig. 7b). These findings indicate that while both EBV DNA and viral particles alter circadian timing, the effects are more pronounced under constant dark conditions. The transition from LD to DD also revealed increased arrhythmicity in EBV-injected flies. During LD, 6.90% of sterile water-injected flies and 3.57% of EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited arrhythmic behavior. However, in DD conditions, the arrhythmicity rate remained unchanged in sterile water-injected flies but increased to 13.04% in EBV DNA-injected flies. Similarly, EBV viral particle-injected flies, which exhibited 0% arrhythmicity in LD, showed an 8% arrhythmicity rate in DD (Fig. 7c). These results confirm that both EBV DNA and EBV viral particles impair circadian stability, with effects becoming more pronounced in constant darkness.

Fig. 7.

Both EBV DNA and EBV viral particle injections affect the circadian function of flies. (a) Decreased free-running period during LD period both in EBV DNA and EBV particles injected flies. Percentage of flies with a period greater or equal to/ lower than 1440 min during light-dark. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂= 29; control PBS injected W1118:♂n = 23; EBV 70 particles injected W1118: ♂n = 29. (b) Free-running period variability during DD period in both EBV DNA and EBV viral particle injected flies. Percentage of flies with a period greater or equal to/ lower than 1440 min during dark-dark. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 29; control PBS injected W1118: ♂n = 23; EBV 70 particles injected W1118: ♂n = 29. (c) Percentage of arrhythmic flies under LD/DD conditions. Control Sterile water injected W1118: ♂n = 28; EBV DNA injected W1118: ♂n = 29; control PBS injected W1118: ♂n = 23; EBV 70 particles injected W1118: ♂n = 29

Discussion

The results of this study shed light on the behavioral effects of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and its derived DNA in Drosophila melanogaster, focusing on lifespan, activity, sleep, and circadian rhythm. This study provides a unique perspective on how viral and viral DNA challenges can influence fundamental biological processes, such as lifespan, aging-related behavioral changes, and circadian function. As with all DAM-based sleep analysis, sleep is inferred behaviorally from inactivity, which may lead to the misclassification of weak or dying flies; we accounted for this limitation by excluding outliers with persistently low activity. Injections are known to induce substantial variability in activity and sleep bouts, even in genetically homogeneous fly strains such as the W1118 males used in this study [29, 30]. This variability is a commonly observed phenomenon in Drosophila circadian and sleep research, and supports the parametric nature of the data presented here. The lifespan of EBV DNA-injected flies was notably shorter compared to controls, with the median survival time reduced significantly. This decrease is consistent with findings from other models where chronic viral challenges accelerate senescence and reduce lifespan due to systemic inflammation or metabolic stress [31]. The average lifespan observed in our study (~ 30 days) was shorter than the typical lifespan of W1118 flies maintained on standard or holidic diets, which often ranges from 50 to 70 days [32]. Furthermore, the microinjection procedure itself, irrespective of whether sterile water or PBS is used, may induce physiological stress, mechanical damage, or immune activation—all of which can reduce survival [33, 34]. The modest difference in survival between PBS- and water-injected flies may reflect the buffering capacity of PBS mitigating local tissue stress. These factors likely contributed to the reduced lifespan observed. While the Drosophila Activity Monitoring (DAM) system remains a well-established and reproducible tool for long-term behavioral analysis [17, 25, 28], future studies incorporating nutritionally complete diets and non-injected control groups will help further disentangle dietary and procedural effects from treatment-specific outcomes. Activity analysis showed reduced locomotor activity and altered anticipation phases in EBV-injected flies. The decline in activity, particularly during critical periods like the transitions between light and dark, suggests impaired behavioral responsiveness. Sleep analysis further revealed significant variability, with EBV DNA-injected flies showing longer sleep bouts and fewer sleep fragments compared to controls. These observations are consistent with earlier reports indicating that viral infections can alter sleep patterns as part of an immune response or due to direct effects on neural circuits [35]. The impact of the viral particles is not negated by the behavioral changes observed in flies that were treated with PBS. Instead, it emphasizes how crucial it is to use PBS as a control since it makes it possible to differentiate between the effects of the solvent and viral particles. The viral particles likely have effects beyond those of PBS alone since behavioral alterations in virus-injected flies are different from those in PBS-injected controls. Our observations are consistent with previous reports that immune activation or microbial challenge increases total sleep and alters activity patterns in flies. For example, peptidoglycan and bacterial infections induce sleep via the NF-κB signaling pathway, presumably to promote energy conservation and recovery during illness [20, 21]. These studies support our interpretation that EBV DNA-induced behavioral changes may reflect a systemic immune response or stress adaptation. Additionally, age-specific analyses showed distinct behavioral changes in young and old flies. For instance, younger EBV DNA-injected flies exhibited lower activity but higher sleep rates, suggesting a possible age-dependent modulation of energy allocation and repair mechanisms. Older flies showed reduced sleep rates and bouts, possibly due to cumulative damage or dysregulation of circadian control mechanisms. Furthermore, the age-dependent variation in activity and sleep aligns with previous findings that aged flies exhibit disrupted sleep architecture, including shorter sleep bouts and increased fragmentation [18, 19].

Arrhythmicity, which evaluates disruptions in regular rhythmic patterns, was also analyzed to understand the destabilization of circadian rhythms under viral challenge. Interestingly, the rhythmic power (Qp) was significantly weaker in EBV DNA-injected flies compared to controls, indicating a diminished strength and regularity of circadian oscillations. However, flies injected with EBV viral particles exhibited stronger rhythmicity, suggesting a differential impact of viral components on circadian control. These findings raise questions about how different viral elements interact with the host’s circadian machinery. The primary data (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) were obtained from a single experimental run. While the DAM system allows for robust multi-parametric behavioral monitoring, unexpected environmental factors including the potential for tube-specific contamination over time may introduce variability. In this study, any tubes showing visible fungal contamination or dry food were excluded from the analysis and treated as outliers. Despite these controls, we acknowledge that subtle or undetected environmental influences could have affected the results, and future replication studies will be important to confirm the reproducibility of these findings. The analysis of circadian rhythm under light-dark (LD) and dark-dark (DD) conditions revealed significant disruptions in the free-running period and rhythmicity of flies injected with EBV DNA and viral particles. Specifically, flies injected with EBV DNA exhibited a shorter free-running period during the LD phase compared to controls. This finding aligns with prior studies that have shown that viral infections can interfere with circadian clocks through modulation of clock genes and signaling pathways (e.g., infection-induced alterations in PER and TIM gene expression) [36]. During the DD phase, arrhythmic behavior increased in EBV-injected flies, highlighting a more profound disruption of endogenous circadian control mechanisms in the absence of external cues. The increased arrhythmicity in flies, particularly under DD conditions, further suggests a decline in circadian output, as reported in other chronobiological studies [37, 38]. The findings in Fig. 5 show that rhythmicity occurs under typical light-dark (LD) conditions, with EBV DNA disrupting rhythm intensity and EBV viral particles seemingly enhancing it. But a distinct result was seen in Fig. 7, where flies were subjected to both LD and continual darkness (DD) settings. This implies that although EBV DNA and particles affect circadian rhythmicity, their effects are amplified in DD settings, most likely as a result of the lack of external light cues. The divergent findings highlight how crucial environmental context is for evaluating circadian stability. Similar disruptions have been observed in models challenged with other pathogens, suggesting a conserved mechanism where viral interactions perturb clock machinery. As reviewed in “The Circadian Clock and Viral Infections”, the innate and adaptive immune responses follow daily rhythms, affecting immune cell numbers, cytokine secretion, and viral susceptibility [39]. Key circadian clock components, including CLOCK, BMAL1, and REV-ERB, regulate immune functions such as pattern recognition receptor (PRR) expression, which is crucial for viral detection. BMAL1 deficiency increases susceptibility to respiratory viruses (e.g., RSV, PIV3) and regulates Ly6Chi monocyte oscillations [40, 41]. REV-ERB, on the other hand, suppresses inflammation, and its loss enhances pro-inflammatory responses (e.g., IL-6 secretion) [42]. In another research pertaining to influenza, loss of clock genes disrupts adaptive immunity, impairing influenza A defense by impacting lymphocyte numbers, which oscillate daily, with glucocorticoids driving T-cell accumulation [43, 44]. Therefore, the circadian clock regulates immune responses critical for controlling viral replication and inflammation, highlighting the importance of maintaining circadian stability for effective immunity. We hypothesize that the observed disruptions in circadian rhythm, activity, and sleep patterns are likely mediated by the interaction of EBV components with core clock genes or their downstream signaling pathways. This study is the first study in which EBV and its viral DNA have been assessed for possible circadian rhythm dysfunction and associated changes in behaviors. Understanding the mechanisms by which viruses like EBV influence these processes can inform strategies to mitigate their impact, such as chronotherapy or targeted antiviral interventions. While we attempted to compare subsets of data from the early days of the 30-day experiment to those from the shorter LD-DD experiment to evaluate reproducibility, we observed significant behavioral variability likely due to the limited duration of the comparison, individual variability in post-injection adaptation, and differing experimental conditions (e.g., lighting regimes). These factors highlight the importance of long-term monitoring when assessing sleep and circadian behavior. Although the DAM system is a well-established and reproducible method in Drosophila behavioral research [17, 25], full reproducibility should ideally be assessed by repeating the 30-day experimental paradigm under identical conditions across independent biological replicates. In summary, this study highlights the importance of interdisciplinary research in understanding the complex relationship between EBV infections, circadian biology, and host behavior. Future investigations should explore how host genetic variability influences these interactions and assess potential therapeutic strategies to restore circadian function during EBV infections.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Core Facilities at the American University of Beirut.

Author contributions

M.S. and E.S. contributed to the study conception and design. G.N. and S.Z. contributes to most of the experimental work. N.S. assisted in the experimental work, G.N. performed the data analysis and data interpretation. G.N. drafted the manuscript. S.Z. M.S., E.S. edited the manuscript. All authors approved the last submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

MS and ES are funded by the American University Medical Practice Plan (MPP).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Georges Naim and Sabah Znait contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Elias A. Rahal, Email: er00@aub.edu.lb

Margret Shirinian, Email: ms241@aub.edu.lb.

References

- 1.Mackie PL. The classification of viruses infecting the respiratory tract. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2003;4(2):84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esterling BA, Antoni MH, Kumar M, Schneiderman N. Emotional repression, stress disclosure responses, and Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen titers. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(4):397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daruna JH. Chapter 8 - Infection, Allergy, and Psychosocial Stress. In: Daruna JH, editor. Introduction to Psychoneuroimmunology (Second Edition). San Diego: Academic Press; 2012. pp. 153– 78.

- 4.Hedström AK. Risk factors for multiple sclerosis in the context of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1212676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, Leng Y, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghol AH, Bitar ER, Hanna A, Naim G, Rahal EA. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2024:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Soldan SS, Lieberman PM. Epstein–Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(1):51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjornevik K, Münz C, Cohen JI, Ascherio A. Epstein–Barr virus as a leading cause of multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and implications. Nat Reviews Neurol. 2023;19(3):160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider-Hohendorf T, Gerdes LA, Pignolet B, Gittelman R, Ostkamp P, Rubelt F et al. Broader Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell receptor repertoire in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2022;219(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kerr J. Early growth response gene upregulation in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-Associated myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Biomolecules. 2020;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ruiz-Pablos M, Paiva B, Montero-Mateo R, Garcia N, Zabaleta A. Epstein-Barr virus and the origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Immunol. 2021;12:656797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunmire SK, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH. Infectious mononucleosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390(Pt 1):211–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fevang B, Wyller VBB, Mollnes TE, Pedersen M, Asprusten TT, Michelsen A et al. Lasting immunological imprint of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection with associations to chronic Low-Grade inflammation and fatigue. Front Immunol. 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Dubowy C, Sehgal A. Circadian rhythms and sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2017;205(4):1373–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherri N, Salloum N, Mouawad C, Haidar-Ahmad N, Shirinian M, Rahal EA. Epstein-Barr virus DNA enhances diptericin expression and increases hemocyte numbers in Drosophila melanogaster via the immune deficiency pathway. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madi JR, Outa AA, Ghannam M, Hussein HM, Shehab M, Hasan Z, et al. Drosophila melanogaster as a model system to assess the effect of Epstein-Barr virus DNA on inflammatory gut diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:586930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosato E, Kyriacou CP. Analysis of locomotor activity rhythms in Drosophila. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh K, Evans JM, Hendricks JC, Sehgal A. A Drosophila model for age-associated changes in sleep:wake cycles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(37):13843–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a National longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):907–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo T-H, Pike DH, Beizaeipour Z, Williams JA. Sleep triggered by an immune response in Drosophila is regulated by the circadian clock and requires the NFκB relish. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams J, Sathyanarayanan S, Hendricks J, Sehgal A. Interaction between sleep and the immune response in drosophila: A role for the NFκB relish. Sleep. 2007;30:389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velingkaar N, Mezhnina V, Poe A, Makwana K, Tulsian R, Kondratov RV. Reduced caloric intake and periodic fasting independently contribute to metabolic effects of caloric restriction. Aging Cell. 2020;19(4):e13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Shi J, Cui H, Wang C-Z, Zhao Z. Effects of NPF on larval taste responses and feeding behaviors in Ostrinia furnacalis. J Insect Physiol. 2021;133:104276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isaac RE, Li C, Leedale AE, Shirras AD. Drosophila male sex peptide inhibits siesta sleep and promotes locomotor activity in the post-mated female. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1678):65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfeiffenberger C, Lear BC, Keegan KP, Allada R. Locomotor activity level monitoring using the Drosophila activity monitoring (DAM) system. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;2010(11):pdb.prot5518. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bushey D, Hughes KA, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep, aging, and lifespan in Drosophila. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrisingh MC, Wu Y, Lnenicka GA, Nitabach MN. Intracellular Ca2+Regulates Free-Running Circadian Clock Oscillation In Vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.eNeuro. 2022;9(2):ENEURO.0418-21.2022. 10.1523/ENEURO.0418-21.2022. Print 2022 Mar-Apr.

- 29.Whalley K. Keeping a lid on alternative fates. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(6):323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287(5459):1834–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagedorn E, Bunnell D, Henschel B, Smith DL, Dickinson S, Brown AW, et al. RNA virus-mediated changes in organismal oxygen consumption rate in young and old Drosophila melanogaster males. Aging. 2023;15(6):1748–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piper MD, Blanc E, Leitão-Gonçalves R, Yang M, He X, Linford NJ, et al. A holidic medium for Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2014;11(1):100–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzou P, Reichhart JM, Lemaitre B. Constitutive expression of a single antimicrobial peptide can restore wild-type resistance to infection in immunodeficient Drosophila mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(4):2152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kounatidis I, Chtarbanova S, Cao Y, Hayne M, Jayanth D, Ganetzky B, et al. NF-κB immunity in the brain determines fly lifespan in healthy aging and Age-Related neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2017;19(4):836–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibarra-Coronado EG, Pantaleón-Martínez AM, Velazquéz-Moctezuma J, Prospéro-García O, Méndez-Díaz M, Pérez-Tapia M, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity against infections. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:678164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Leone MJ, Hernando CE, Romanowski A, Careno DA, Soverna AF, Sun H, et al. Bacterial infection disrupts clock gene expression to attenuate immune responses. Curr Biol. 2020;30(9):1740–e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakshit K, Giebultowicz JM. Cryptochrome restores dampened circadian rhythms and promotes healthspan in aging rosophila. Aging Cell. 2013;12(5):752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vienne J, Spann R, Guo F, Rosbash M. Age-Related reduction of recovery sleep and arousal threshold in Drosophila. Sleep. 2016;39(8):1613–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borrmann H, McKeating JA, Zhuang X. The circadian clock and viral infections. J Biol Rhythms. 2021;36(1):9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang SL, Yu C, Jiang JX, Liu LP, Fang X, Wu C. Hepatitis B virus X protein disrupts the balance of the expression of circadian rhythm genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(6):2715–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuang X, Magri A, Hill M, Lai AG, Kumar A, Rambhatla SB, et al. The circadian clock components BMAL1 and REV-ERBα regulate flavivirus replication. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbs JE, Blaikley J, Beesley S, Matthews L, Simpson KD, Boyce SH, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα mediates circadian regulation of innate immunity through selective regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(2):582–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimba A, Cui G, Tani-Ichi S, Ogawa M, Abe S, Okazaki F, et al. Glucocorticoids drive diurnal oscillations in T cell distribution and responses by inducing Interleukin-7 receptor and CXCR4. Immunity. 2018;48(2):286–.– 98.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Druzd D, Matveeva O, Ince L, Harrison U, He W, Schmal C, et al. Lymphocyte circadian clocks control lymph node trafficking and adaptive immune responses. Immunity. 2017;46(1):120–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.