Abstract

Background

Adipose tissue plays a central role in systemically metabolic regulation. Polymerase I and transcript release factor (PTRF) is responsible for caveolae structure formation and plays a crucial role in lipid metabolism.

Results

We investigated the possibility of modifying adipose mass by targeting the enhancers of Ptrf. Single-nucleus transcriptomic analysis revealed that the reduction in fat mass caused by Ptrf knockout is associated with impaired adipogenesis and differentiation, adipocyte metabolism, nutrient transportation, and altered regulatory network. We demonstrated a closely positive association between Ptrf transcription and adipose mass in mice. Then, circular chromosome conformation capture sequencing and ChIP-seq data of mature adipocytes identified six candidate enhancers (E1–E6) of Ptrf, and the dual-luciferase reporting system revealed the transcriptional activity of three active candidate enhancers (E1, E3, E5) in Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) and mouse embryo fibroblast (3T3-L1) cells. During the adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1, the epigenetic perturbation of these enhancers with the dCas9-KRAB system demonstrated their important roles during adipogenesis, with inhibited Ptrf expression and decreased lipid droplets and triglyceride contents. Injecting lentivirus carrying the dCas9–KRAB system into the inguinal fat of mice downregulated Ptrf expression and decreased body weight, body adipose percentage, and adipocyte diameter in vivo. Additionally, we observed the close binding of Pparg and Cebpa to Ptrf-E1.

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings identify the mechanism by which Ptrf deletion leads to reduced fat mass in mice, and indicate that adipose mass may be reduced by targeting cis-regulatory elements of key adipogenesis-related genes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12915-025-02405-6.

Keywords: Ptrf, SnRNA-seq, Chromatin interaction, 4C-seq, Enhancer

Background

Adipose tissue (AT) is a morphologically unique tissue; it accumulates lipids in the form of cytoplasmic lipid droplets, to buffer energy availability in response to changes in the body’s environment. Numerous studies have also revealed that AT is an endocrine organ that regulates systemic energy homeostasis [1, 2]. An excessively increased adipose mass is the primary phenotypic characteristic of obesity [3] and is associated with metabolic diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver [4], metabolic syndrome, arteriosclerosis, coronary artery disease, and type 2 diabetes [5]. A primary therapeutic strategy against obesity and obesity-induced metabolic syndrome involves the modification of adipose mass. However, recent studies have highlighted the modification of abnormal gene expression as a new strategy to combat obesity [6, 7]. Compared with editing coding sequences to alter protein structure, the modification of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) has fewer pleiotropic effects and causes more precise alterations by changing gene expression patterns, thus allowing the improved regulation of genes. Alterations in CREs cause subtle changes in quantitative traits. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg), a critical proadipogenic transcription factor, plays a maintenance role for differentiated adipocytes. The 10-kb enhancer upstream of the Pparg locus forms a chromatin loop with the Pparg promoter, binding the CEBPA and PRMT5 proteins to regulate Pparg expression during adipogenic differentiation [8]. Additionally, other study has shown that the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (Cebpa) is important in the terminal differentiation of adipocytes [9]. CRISPR-mediated transcription inhibition of an enhancer of Cebpa significantly decreased Cebpa expression and adipocyte size, altered iWAT transcriptome, and affected iWAT development [10]. These studies suggest that adipogenesis-related enhancers could regulate the precise spatiotemporal expression of target genes in adipogenesis [11, 12]. Relative to traditional CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-mediated gene disruption technology, CRISPR-interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR-activation are efficient tools for simply and flexibly regulating specific gene expression in various organisms [13–15]. It is therefore essential to identify suitable candidate genes and corresponding enhancers for modifying adipose mass.

Polymerase I and transcript release factor (PTRF) is a crucial component of caveolae structure, with a key role in the formation of lipid microdomains on the plasma membrane surface [16, 17]. Moreover, PTRF has multiple copies in each caveolae structure and generates caveolae invagination, which is considered the primary organizer of caveolae [18, 19]. In adipocytes, caveolae can represent up to 50% of the plasma membrane surface [20]. They are involved in regulating fatty acid transfer and triglyceride biosynthesis, and serve as reservoirs for excess free fatty acids. Mutations in the human PTRF gene have been Linked to congenital generalized Lipodystrophy type 4, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a near-complete loss of body fat [21–23]. Mice lacking Ptrf also exhibit significantly reduced body fat, leading to insulin resistance [24], while Ptrf overexpression results in increased body weight and fat mass [25]. Overall, although the mechanisms underlying the decreased adipose mass in Ptrf−/− mice remain to be fully determined, Ptrf may be a candidate target gene for modifying adipose mass.

In this study, we evaluated the feasibility of modifying adipose mass by targeting the enhancers of Ptrf. First, we investigated the molecular mechanisms of Ptrf that affect fat deposition at single-nucleus resolution. Next, we examined the relationship between Ptrf transcription and fat mass. Thereafter, we identified the functional enhancers of Ptrf by combining ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq) and circular chromosome conformation capture sequencing (4C-seq) data. We demonstrated the potential function of these enhancers in coordinating Ptrf transcriptional activity using the endonuclease-deficient CRISPR-associated protein 9 (dCas9)–Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) system, both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, we assessed the potential role of transcription factors (TFs) in enhancer activity.

Results

Adipogenic differentiation impairment and adipocyte metabolism dysregulation in Ptrf−/−mice

The potential mechanisms underlying the decreased adipose mass of Ptrf knockout (Ptrf−/−) mice may involve a deficiency of pre-adipocytes (pre-AD), impaired adipocyte differentiation, lipid uptake, and triglyceride synthesis, accelerated lipolysis, and/or death/destruction of existing adipocytes [26, 27]. However, these possible mechanisms require further exploration. As expected, we observed a global loss of caveolae, reduced AT mass, and raised circulating triglycerides using previously constructed Ptrf−/− mice [28] (Additional file 1: Fig. S1), consistent with previous studies [29]. We therefore performed single-nucleus RNA-seq (SnRNA-seq) on inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT). After rigorous quality control and filtering, 11,963 nuclei from normal mice and 9497 nuclei from Ptrf−/− mice were retained for subsequent analysis. All nuclei were divided into 12 clusters and annotated to nine cell types based on typical cell markers (Fig. 1A, B; Additional file 2: Fig. S2A and Additional file 9: Table S1); these findings were supported by functional enrichment analysis (Additional file 2: Fig. S2C). We identified between 13 and 693 differentially expressed genes in each cell type in the Ptrf−/− mice (Additional file 2: Fig. S2D); adipocytes were ranked second, with 598 differentially expressed genes (186 upregulated and 412 downregulated). Among the top 20 upregulated terms in Ptrf−/− adipocytes, three were related to lipid metabolism (including fat cell differentiation and phosphoric diester hydrolase activity), and six were related to growth and development (including regulation of angiogenesis, regulation of developmental growth, and regulation of vasculature development). By contrast, eight of the top 20 downregulated terms in Ptrf−/− adipocytes were related to lipid metabolism (including the regulation of lipid biosynthetic process and triglyceride biosynthetic process), five were related to cellular structure (including caveola and membrane raft), and three were related to energy metabolism and transport (Additional file 2: Fig. S2E). Overall, these results indicate the marked and complex effects of Ptrf− knockout on adipocytes.

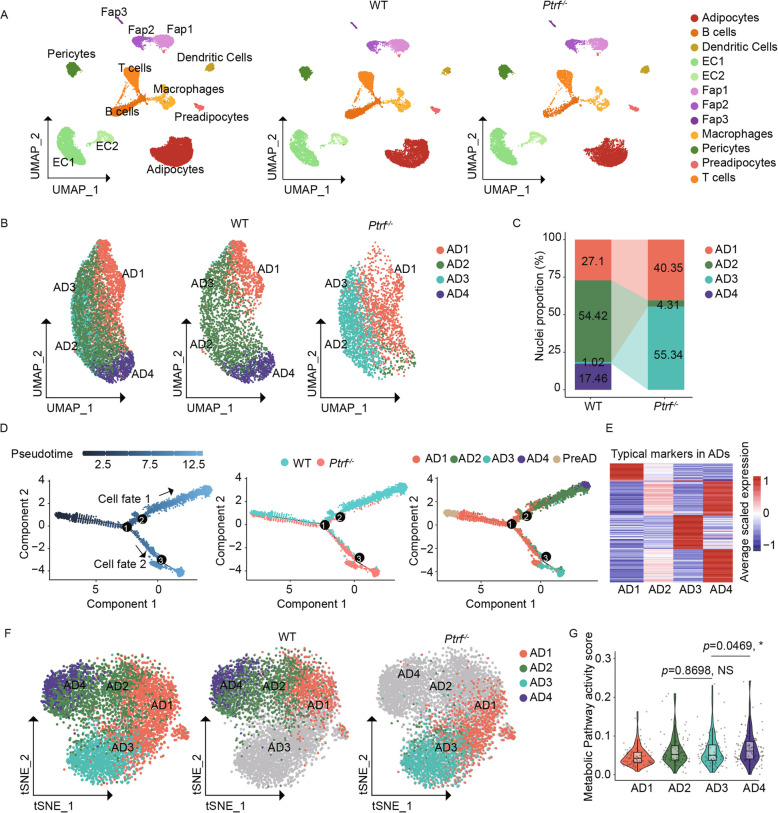

Fig. 1.

SnRNA-seq revealed a fate shift of adipocytes in Ptrf−/− mice. A UMAP visualization of the major cell types of iWAT in Ptrf−/− and WT mice. Each dot represents a nucleus, and was color-coded for each cell type. B UMAP visualization of adipocyte subtypes. Each dot was color-coded based on the cluster identity. C The proportion of adipocyte subtypes in Ptrf−/− and WT mice. D The pseudotime trajectory displayed the differentiation path of Pre-AD and adipocyte subtypes. The trajectory branch points were marked by numbered circles. E Average scaled gene module scores of the top 50 marker genes in each subtype. F Clustering on metabolic gene expression profiles of adipocyte subtypes. The dots were colored according to different adipocyte subtypes. G Violinplot showing the metabolic activities of different adipocyte subtypes. Each dot represented the activity score of an individual metabolic pathway. *p < 0.05 and “NS” means no significance

Next, we conducted a re-clustering analysis of 6033 adipocyte nuclei. We identified four distinct subpopulations (AD1–4) with elevated expression levels of adipogenesis-related marker genes (Fig. 1B; Additional file 2: Fig. S2F, and Additional file 10: Table S2), thus eliminating the possibility of mixing of other cell types. A comparison of the subcellular compositions of Ptrf−/− mice revealed a higher proportion of AD1 and AD3 cells, a lower percentage of AD2 cells, and a nearly complete absence of AD4 cells (Fig. 1C) compared with WT mice, indicating that marked changes in adipocyte states occur upon Ptrf deletion. To elucidate the developmental relationships of these adipocyte subpopulations, we constructed a developmental trajectory by combining the four subpopulations and pre-AD and conducting a Monecle2 analysis (Fig. 1D). The trajectory path extended from pre-AD to AD1 adipocytes in both WT and Ptrf−/− mice. Subsequently, AD1 gave rise to two branches in the following pseudo-time trajectory: a sequential conversion from AD1 to AD2 and AD4 in WT mice, and a direct conversion from AD1 to AD3 in Ptrf−/− mice. These findings highlight the modified differentiation process of adipocytes in Ptrf−/− mice.

Compared with the other three subtypes, AD3 exhibited distinct expression profiles (Additional file 2: Fig. S2G) and typical marker genes (Fig. 1E). Specifically, dysregulation of some mature adipocyte-specific genes was observed in AD3 (Additional file 2: Fig. S2H). For example, Cebpa, a typical adipogenic master regulator with increased expression in the later stages of differentiation [30, 31], displayed relatively lower expression levels in AD3. In addition, two key adipokines—leptin (LEP) and adiponectin (ADIPOQ), which are produced in the late stages of adipogenic differentiation [32–34]—showed significantly decreased expression levels in AD3 from Ptrf−/− mice compared with those from WT mice. These results suggest that adipocyte differentiation is impaired in Ptrf−/− mice.

LEP and ADIPOQ levels are directly proportional to body fat mass [35–37]. Moreover, the decreased serum LEP and ADIPOQ concentrations in congenital generalized Lipodystrophy type 4 may be associated with the decreased production of LEP and ADIPOQ in single adipocytes or decreased adipocyte number. These results highlight the potential contribution of decreased LEP and ADIPOQ production in single adipocytes to the decreased serum LEP and ADIPOQ concentrations in congenital generalized Lipodystrophy type 4. Of note, observable increases in dedicator of cytokinesis protein 9 (DOCK9) and RAN-binding protein 9 (RANBP9) expression were also observed in AD3 from Ptrf−/− mice compared with those from WT mice. RANBP9 serves as a platform for the interaction of various signaling proteins such as “cell surface receptors,” “nuclear receptors,” “nuclear TFs,” and “cytosolic kinases” [38, 39]. Dock9 and Ranbp9 positively regulate GTPase activity and are predicted to be located in the plasma membrane. The expression of LEP, ADIPOQ, DOCK9, and RANBP9 was further confirmed through immunofluorescence staining of iWAT (Additional file 2: Fig. S2I).

Next, we compared the metabolic activity of each adipocyte subpopulation using the single-cell metabolic landscape pipeline [40]. Visualization with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding based on 1445 metabolic genes revealed two distinct branches of metabolic activity, one leading from AD1 to AD2 and AD4, and the other from AD1 to AD3 (Fig. 1F), indicating the important role of Ptrf deletion-induced metabolism dysregulation. We identified 84 metabolic pathways that showed a gradual increase in metabolic activity from AD1 to AD2 and AD4 (Fig. 1G), suggesting a progressive rise during adipogenic differentiation. Interestingly, AD3 (the ultimate differentiated adipocyte in Ptrf−/− mice) exhibited a significant decrease in metabolic activity compared with AD4 (the ultimate differentiated adipocyte in WT mice) but had comparable metabolic activity to AD2 (the intermediate differentiated adipocyte in WT mice). A hierarchical clustering analysis of metabolic pathway activity grouped AD2 and AD4, and separated AD1 and AD3 into another group (Additional file 3: Fig. S3A), suggesting a potential stagnant metabolic state of adipocytes following Ptrf deletion. Further examination of each metabolic pathway revealed the downregulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in AD3, with exceptions in certain pathways such as “steroid biosynthesis,” “fatty acid biosynthesis,” and “primary bile acid biosynthesis” (Additional file 3: Fig. S3B and C). However, no significant difference in metabolic activity was observed between AD1 from WT and Ptrf−/− mice (Additional file 3: Fig. S3D and E). Together, our findings indicate that Ptrf deletion disrupts metabolic activity in adipocytes, and particularly results in the stagnation of metabolic processes in AD3.

Ptrf deletion induces a unique transcriptional regulatory network of adipogenesis

To identify genes that influence adipogenesis, we identified 333 branch-dependent genes at branch point 1 using branch expression analysis modeling; these were categorized into four groups: G1–4 (Additional file 11: Table S3). Genes in G1 and G2, which exhibited decreased expression levels in AD3, were associated with membrane structure and substrate transport-related terms such as “caveola,” “plasma membrane raft,” “positive regulation of endocytosis,” “long-chain fatty acid transporter activity,” “glucose transmembrane transport,” “monosaccharide transmembrane transport,” and “carbohydrate transmembrane transport.” The altered expression levels of genes responsible for the transportation of multiple nutrients, including long-chain fatty acids, glucose, and carbohydrates (Fig. 2A), are consistent with previous reports that caveolae provide perfect “docking sites” for membrane transport and participate in receptor signaling and endocytosis [41–43]. Specifically, some nutrient transportation-related genes were detected in these two modules, such as Cd36 and Cav1. Cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) is the predominant transporter responsible for the transportation of fatty acids across the adipocyte plasma membrane; it can bind long-chain fatty acids and is required for lipid utilization and energy storage [44].

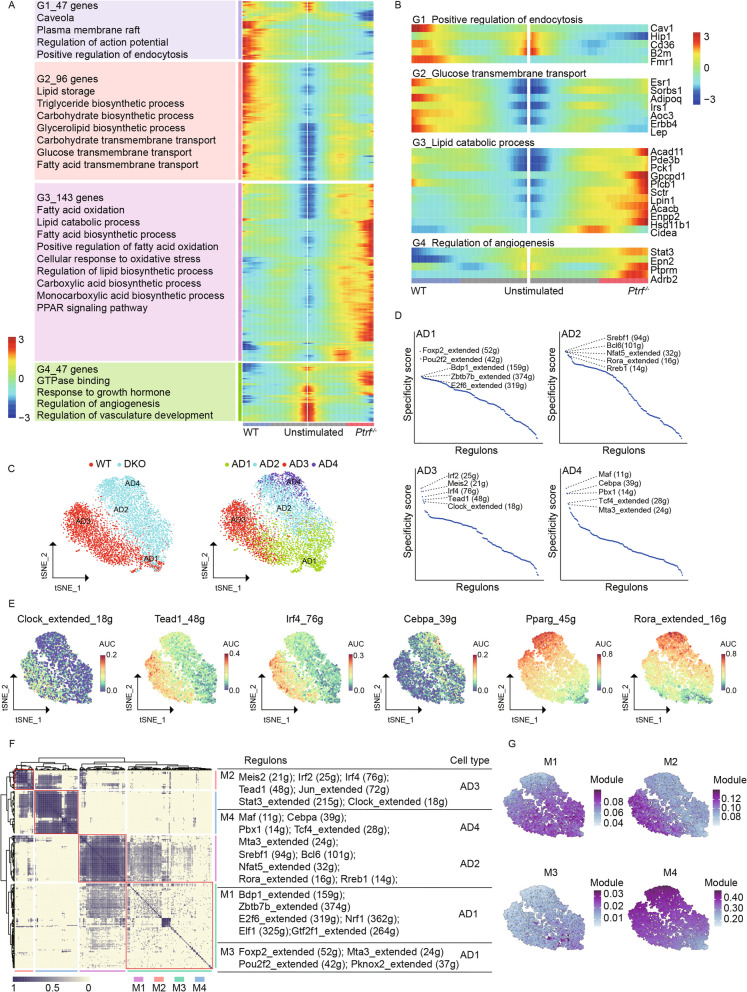

Fig. 2.

Role of transcriptional regulatory network in determining adipogenic differentiation. A Branch trajectory Heatmap depicting the expression of the branch-dependent genes at the branch nodes 1 toward along pseudotime. The differentially expressed genes were clustered into four groups according to K-means (right). Main functional annotations of branch-dependent genes in each group were displayed (left). B Expression heatmap of genes in the representative pathway term across pseudotime. C t-SNE plot on regulon activity matrix of four adipocyte subtypes from WT (blue) and Ptrf−/− (red) mice. Each nucleus was colored according to genotype or subtype. D The dot plot showing the cell-type specific regulons with Regulon specificity score (RSS), the top 5 ranking regulons of 4 adipocyte subtypes were listed. E t-SNE on the regulon activity matrix showing the changed regulons activity across four adipocyte subtypes. F Identification of regulon modules based on the regulon connection specificity index (CSI) matrix, along with associated cell types, and representative transcription factors. G Average module activity scores were calculated and mapped on t-SNE plot. Different modules were associated with distinct adipocyte subtypes and regulon activities

By contrast, G3 exhibited an elevated expression level in AD3 and was associated with terms related to lipogenesis and lipolysis, such as “lipid catabolic process,” “fatty acid oxidation,” “positive regulation of fatty acid oxidation,” “regulation of lipid biosynthetic process,” and “fatty acid biosynthetic process” (Fig. 2B and Additional file 3: Fig. S3F), thus indicating the intricate functional roles of lipogenesis and lipolysis in Ptrf−-induced lipodystrophy. G4 also showed increased expression levels in AD3, and was linked to terms such as “regulation of angiogenesis,” “regulation of vasculature development,” and “GTPase binding.” Adipocytes can express angiogenic factors at various differentiation stages, and conditions such as those of nutrient overload (e.g., a high-fat diet) can elevate pre-adipocyte mRNA expression of angiogenic factors [45]. Moreover, because blood vessels supply vital nutrients and oxygen to adipocytes and act as a reservoir for pre-AD [46], we speculate that the upregulation of angiogenesis-related genes in AD3 may be a compensatory response to the impaired transportation capacity and adipogenic differentiation of adipocytes in Ptrf−/− mice.

To identify the key regulatory network in each subtype, single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering analysis was conducted. Cells were scored and re-clustered based on the activity of 267 gene regulatory networks, and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding analysis revealed differences in regulon activity among adipocyte subsets (Fig. 2C). Subsequently, regulon specificity scores were used to identify cell-type-specific regulons (Fig. 2D). AD2 and AD4 expressed regulons that are crucial for cell growth and differentiation and glucose and lipid metabolism, including Cebpa (39g), Foxo1 (extended 42 g), and Rora (extended 16 g) [47–50]. Interestingly, these regulons were not present in AD3 (Fig. 2E). By contrast, AD3 exhibited high activity of regulons such as Irf2 (25g), Meis2 (21g), Irf4 (76g), Tead1 (48g), and Clock (extended 18 g). Previous studies have shown that Clock plays a key role in inhibiting pre-adipocyte differentiation both in vivo and in vitro [51]. The elevated activity of Clock (extended 18 g) in AD3 therefore suggests a potential involvement of Clock in Ptrf-induced adipogenic differentiation arrest.

The overall similarities of AUCell scores for each regulon pair were assessed using the Connection Specificity Index. A total of 267 regulons were categorized into four major modules (Fig. 2F). Each module was enriched with subtype-specific regulons and exhibited distinct regulon activities that were differentially expressed across subtypes (Fig. 2G), indicating variations in gene regulatory networks among the subtypes. For example, modules M1 and M3 were enriched with AD1-specific regulons, such as Bdp1 (extended 159 g), Zbtb7 (extended 374 g), Foxp2 (extended 52 g), and Mta3 (extended 24 g). Correspondingly, M1 and M3 showed high activity in AD1. Overall, these findings highlight the marked alterations that occur in the regulatory network following Ptrf deletion.

Ptrf mRNA expression levels positively affect adipose mass and adipocyte size in a dose-dependent manner

Previous studies have indicated a strong correlation between Ptrf expression levels and adipocyte surface area [52]. Additionally, Ptrf−/− impeded adipogenic differentiation, lipid transport, and lipid synthesis, which might result in a linear effect on adipose mass. On the basis of these findings, we hypothesized that a potential dose-dependent relationship between Ptrf expression and fat mass may exist. Thus, we used four different genotypic mice—homozygous knock-in mice (DKI), heterozygous knock-in mice (SKI), homozygous knock-out mice (DKO), and heterozygous knock-out mice (SKO)—and WT mice. The preparation strategy for the gene-edited mice is outlined in Fig. 3A. The DKO and SKO mice were prepared as reported previously [28]. All pups were genotyped using PCR followed by sanger sequencing (Additional file 4: Fig. S4A and B).

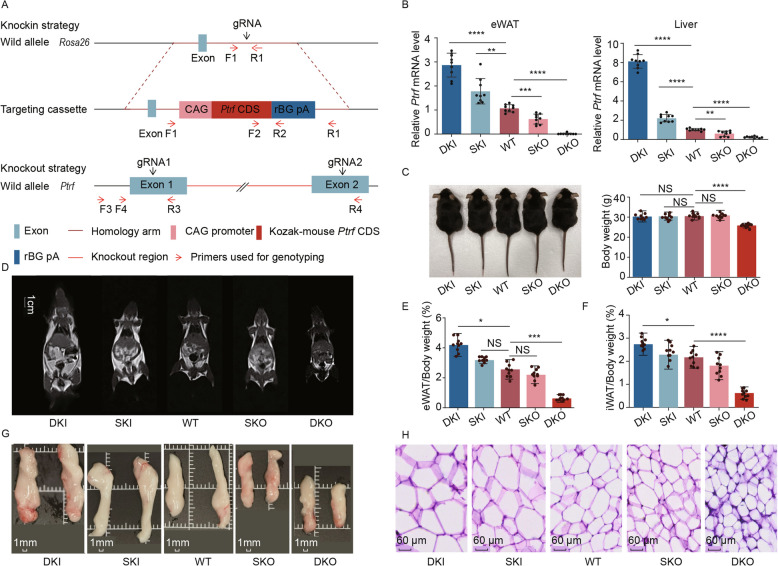

Fig. 3.

Ptrf mRNA expression was positively correlated with fat deposition. A Schematic representation of the strategy of the targeting vector. B Ptrf mRNA relative expression level of eWAT and liver in each genotypic group (n = 3). C Body characteristics (left) and the body weight (right) of each genotypic mouse at the age of 3 months (n = 10). D MRI further depicted the body fat content of each genotypic mouse, scale bar = 1 cm. E The percentage of body fat was expressed as a ratio of eWAT versus body weight (n = 10). F The percentage of body fat was expressed as a ratio of iWAT versus body weight (n = 10). G Representative pictures of eWAT from 9-month-old mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. H Representative H&E staining images of the eWAT of each genotypic mouse, the scale bar was 60 mm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Compared to the WT group. “NS” means no significance

Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) revealed differential gene expression levels upon Ptrf knockout or overexpression in eWAT (Fig. 3B and Additional file 4: Fig. S4C). For example, compared with WT mice, Ptrf mRNA was upregulated 2.67-fold and 1.66-fold in DKI mice and SKI mice, respectively, in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT). By contrast, Ptrf mRNA was downregulated 0.58-fold in SKO mice, and was not expressed at all in DKO mice. A slight but non-significant increase in the body weight of 12-week-old male DKI mice was noted compared with their WT littermates, and a significant decrease was observed in DKO mice (Fig. 3C; Additional file 12: Table S4), consistent with a previous study [24]. To further investigate the relationship between Ptrf mRNA expression levels and fat deposition, we determined the AT content of the five mouse genotypes using MRI analysis (Fig. 3D). The fat distribution varied widely; DKI mice had a relatively high total body fat content, with clear fat deposition in interscapular subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT), iWAT, and eWAT. By contrast, DKO mice had little fat content and almost no subcutaneous fat, with only a few AT observed around the epididymis. We consistently observed increased body fat with increased Ptrf mRNA expression levels (Fig. 3E and F). For example, the ratio of eWAT weight to body weight was 2.6% in WT mice, 4.2% in DKI mice, and 0.6% in DKO mice. However, body weights showed larger differences among the five genotypes at 9 months of age (Additional file 4: Fig. S4D). We measured the diameters and areas of adipocytes obtained from sWAT, eWAT, iWAT, and perirenal white adipose tissue (pWAT) at 9 months of age using Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. Almost all adipocytes were of the smallest size in DKO mice, followed by SKO, WT, SKI, and DKI mice (Fig. 3G and H; Additional file 4: Fig. S4E). Taken together, these results indicate a clear dose-dependent relationship between Ptrf mRNA expression and fat mass.

Identification and functional examination of enhancers of Ptrf during adipogenic differentiation in vitro

Given the clear association between Ptrf expression and adipose deposition, and enhancers could play important roles in regulating distantly located genes [53], we evaluated the feasibility of modifying adipose deposition by targeting the enhancers of Ptrf. The 4C-seq was performed with 3T3-AD (day 4 after adipogenic induction) cells using Ptrf promoter as the bait (Additional file 5: Fig. S5A and B). Two replicated libraries with high Pearson correlations were generated to obtain a confident chromatin interaction map (Additional file 5: Fig. S5C and D). Previous investigations have used H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K4me3 to identify enhancers [54, 55]. Next, we manually annotated candidate enhancers of Ptrf, approximately 250-Mb upstream and downstream of the transcription start site, by combining 4C-seq and ChIP-seq data. Six enhancers were co-marked by H3K27ac and H3K4me1 and further confirmed through a publicly available DNase I hypersensitive site and RNA PolⅡ sequencing dataset (Fig. 4A). In addition, we visualized our previously published Hi-C data [56] and revealed that these candidate enhancers and promoter of Ptrf were located within an interaction domain of mouse embryo fibroblast (3T3-L1) mature adipocytes. Furthermore, a close examination of public ChIP-seq data revealed the strong enrichment of CTCF and SMC1 (a subunit of the cohesin complex) in the Ptrf promoter region (Additional file 5: Fig. S5F), suggesting that the Ptrf promoter may act as a docking site for chromatin loops. Taken together, these results indicate the potential regulatory relationship between these enhancers and promoter of Ptrf.

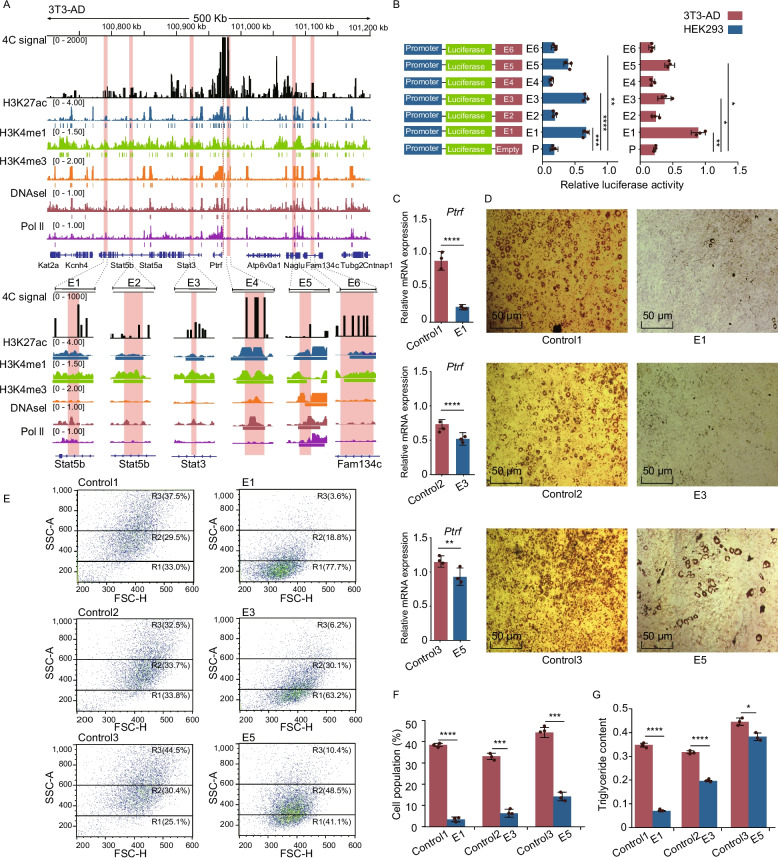

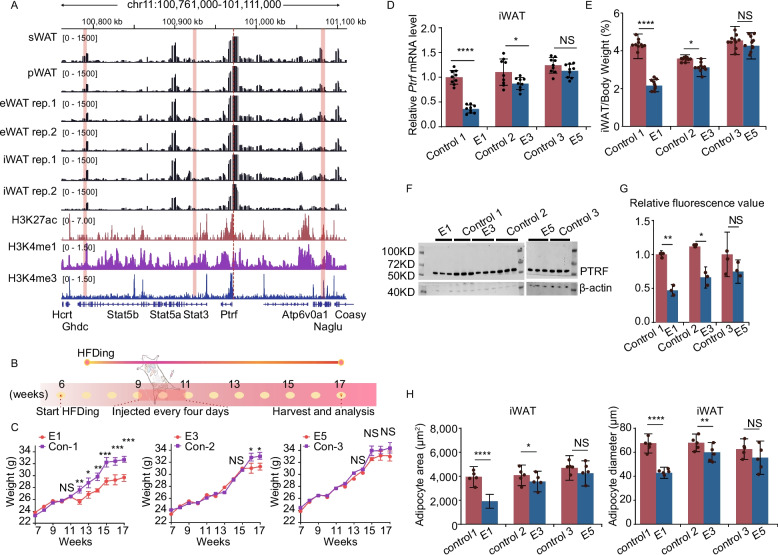

Fig. 4.

The epigenetic repression of Ptrf candidate enhancers inhibited lipogenesis in vitro. A Adjacent to the Ptrf gene region showing enhancer-associated characteristics in mature adipocytes. Upper panel: Integrative genomics viewer (IGV) was used to visualize the 4 C interaction profile (black), H3K27ac (blue), H3K4me1 (green), H3K4me3 (orange), DNasel (red), and Pol II (purple) marks of 3T3-AD (day 4 after adipogenic induction). The red dotted line represented the viewpoint of Ptrf. The pink column represents the putative active enhancers. Lower panel: zoom in view of the putative active enhancer signals. Schematic diagram of six candidate enhancers interacting with Ptrf promoter. The vertical lines below the ChIP-seq profiles indicate the peak. B Luciferase assay was performed in HEK293 and 3T3-L1 cells after 4 days of differentiation to test the activity of candidate enhancers. Bar graph depicting luciferase activity of reporter constructs containing cloned fragments of Ptrf promoters and each enhancer. C Relative expression of Ptrf mRNA following CRISPR-mediated inhibition (n = 3). D Lipid accumulation upon CRISPR-mediated enhancer inhibition was monitored by Oil Red O staining. Scale bar, 50 μm. E The R1–R3 regions were gated for cell populations based on their granularity distribution. CRISPR-mediated inhibition appeared different granularity and heterogeneity. The X-axis, FSC, represents the cell size, whereas the Y-axis, SSC, represents cytoplasmic granular intensity. F The histograms showed the percentages of lipid-rich cell populations detected in the R3 region upon CRISPR-mediated inhibition (n = 3). G The content of triglycerides was measured upon CRISPR-mediated inhibition (n = 5). All experiments were performed in triplicate (mean ± SD), and p values were calculated using a two-tailed t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

To estimate enhancer transcriptional activity, the promoter of Ptrf and each enhancer were simultaneously cloned into a pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector. After transfection of the luciferase reporter vector into Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) and 3T3-AD cells, luciferase activities of E1, E3, and E5 were strong in both cell types compared with the control. The strongest regulatory activity was observed in E1, with a 4.25-fold increase of luciferase activity in 3T3-AD, and a 2.97-fold increase of luciferase activity in HEK293 cells (Fig. 4B). To further examine the potential roles of E1, E2, and E3 in adipogenesis in vitro, we designed two single guide RNAs for each enhancer and cloned them into the lentiviral expression vectors. The same experiment was performed simultaneously in three similarly sized controls (approximately 1 kb) located in intronic or untranslated regions that lacked enhancer-associated characteristics (Additional file 6: Fig. S6A). Compared with those controls, all three experimental groups showed significant inhibition of Ptrf gene expression, with the strongest changes observed in the E1-dCas9 and E3-dCas9 groups on days 6 and 8 of differentiation (Fig. 4C; Additional file 5: Fig. S5 E; Additional file 12: Table S4). Importantly, the mRNA expression levels of adipogenic markers differ in 3T3-AD. The decrease of Ptrf expression caused by dCas9-E1 was accompanied by huge changes in the expression of all the five adipogenic markers. dCas9-E3 was accompanied by a decrease in Fabp4, Lep, Cebpa and Adipoq expression, and dCas9-E5 was only accompanied by a decrease in Fabp4 and Adipoq expression (Additional file 6: Fig. S6B; Additional file 12: Table S4). We then detected lipid droplet morphology and triglyceride content in adipocytes. Oil Red O staining showed decreased lipids upon E1 and E3 inhibition on day 6 (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, a dot plot of cytometric forward scatter (reflecting cell diameter) and side scatter (reflecting granular structures within the cell) revealed the increased heterogeneity of cellular granularity after adipogenic induction[57, 58]. Consistent with previous findings that a higher fat content was associated with the increased granularity of fat cells (Fig. 4E). 3T3-L1 cells were used to define negative gate region1 (R1), whereas the region2 (R2) and region3 (R3) were defined empirically to represent varying intracellular granularity. Overall, the inhibition of all three enhancers significantly altered the lipid content. Compared with the corresponding control, the ratio of mature adipocyte (R3) cells was decreased in the E1-dCas9, E2-dCas9, and E3-dCas9 groups (Fig. 4E and F; Additional file 13: Table S6). The inhibition of E1 and E3 also reduced the triglyceride content on day 8 of adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 4G; Additional file 13: Table S7). Collectively, these findings suggest that E1, E2, and E3 play crucial roles in regulating adipocyte differentiation via their regulation of Ptrf.

dCas9-KRAB-mediated repression of Ptrf enhancers result in reduced adipose mass in vivo

To further test whether a relationship exists between the Ptrf enhancers and promoter in vivo, we performed 4C-seq of iWAT, eWAT, sWAT, and pWAT in mice. There was a highly similar interaction map between 3T3-AD and the four ATs (Fig. 5A). Particularly, the three candidate enhancers showed clear 4 C peaks in at least two ATs, with an overall presence of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 marks, suggesting the potential function of the three enhancers in vivo. Next, we injected CRISPRi lentiviral vector into mice in a high-fat diet condition, who showed high Ptrf expression levels (Additional file 7: Fig. S7A). Each single guide RNA sequence targeting the corresponding candidate enhancers was cloned into the dCas9–KRAB–GFP (Additional file 6: Fig. S6A). Again, intronic or 5′-untranslated region controls were used to rule out the possibility of CRISPRi-induced passive perturbation of the corresponding host genes.

Fig. 5.

CRISPR-mediated inhibition of E1 and E3 decreased fat deposition in vivo. A The schematic diagram shows the chromatin interactome and histone marks of the promoter of Ptrf. Local 4C-seq signal (black) for the Ptrf promoter viewpoint, either in four adipose tissues (iWAT, eWAT, sWAT, and pWAT). Below, the H3K27ac (red), H3K4me1 (purple), and H3K4me3 (blue) ChIP-seq signals were aligned. The red dotted line represents the viewpoint of Ptrf. The pink column represented the putative active enhancers. B Schematic representation of injection of lentiviral vectors in iWAT. Mice were fed high-fat diet starting at 6 weeks of age until 17 weeks of age. C Body weight of control and CRISPR-inhibited mice were measured weekly (n = 10). D Decreased Ptrf mRNA expression upon injection of CRISPRi lentivirus into iWAT (n = 3). E The percentage of iWAT weight was decreased upon injection of CRISPRi lentiviral vector into iWAT (n = 10). F Western blotting was used to assess the protein levels of PTRF in the inguinal adipose tissue from the lentivirus injection mice. G Quantitative data of protein band intensity (gray value) after normalization to β-actin. H Histogram of iWAT area (μm2) and diameter (μm) from 17-week-old mice (n = 5). Results were represented as mean ± SD. Two-tailed t test was used for comparison among them. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. “NS” means no significance

In the first week after ending the injections (12 weeks), the E1-dCas9 group started to show body weight differences. In addition, the E3-dCas9 group started to show body weight differences at 16 weeks. However, although body weight appeared slightly lower in the E5-dCas9 group than in the control group, the difference was not significant (Fig. 5C). At the end of 17 weeks, Ptrf expression levels in iWAT were reduced 2.77-fold than control1 in the E1-dCas9 groups, and reduced 1.26-fold to control2 in the E3-dCas9 groups (Fig. 5D; Additional file 12: Table S4). Stat5b and Stat3 expression was not altered at the same time (Additional file 7: Fig. S7F). RT-PCR conducted on iWAT from lentivirus-injected mice revealed significantly downregulated (p < 0.01) expression levels of Adipoq, Lep, and Cebpa in the Ptrf-En1 group, significantly downregulated (p < 0.01) expression levels of Adipoq and Lep in the Ptrf-En3 group, with no differences observed within Ptrf-En5 groups (Additional file 7: Fig. S7G; Additional file 12: Table S4). In addition, the weight of iWAT was significantly reduced in the E1-dCas9 and E3-dCas9 groups but not in the E5-dCas9 groups (Additional file 7: Fig. S7H and I). Furthermore, the E1-dCas9 group had a reduced percentage of iWAT by 2.1%, and E3-dCas9 treatment reduced iWAT fat content by 0.4% (Fig. 5E). The quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity and WB gray values demonstrated a similar trend; specifically, the expression of PTRF protein in E1-dCas9 was markedly lower than in control 1, Concurrently, the E3-dCas9 exhibited a significantly lower expression compared to control 2. No significant difference was observed between E5-dCas9 and control 3 (Fig. 5F and G). Consistent with these results, histological analysis revealed that the targeting of E1-dCas9 and E3-dCas9 reduced the cross-sectional area, with a 1.58-fold decrease in the E1-dCas9 group and a 1.13-fold decrease in the E3-dCas9 group, whereas there was no significant difference in the E5-dCas9 group (Fig. 5H). The expression level of Ptrf could be regulated by the three enhancers, but different enhancers exerts different regulatory effects on fat deposition.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha closely bind to E1 to coordinate transcriptional activity of Ptrf

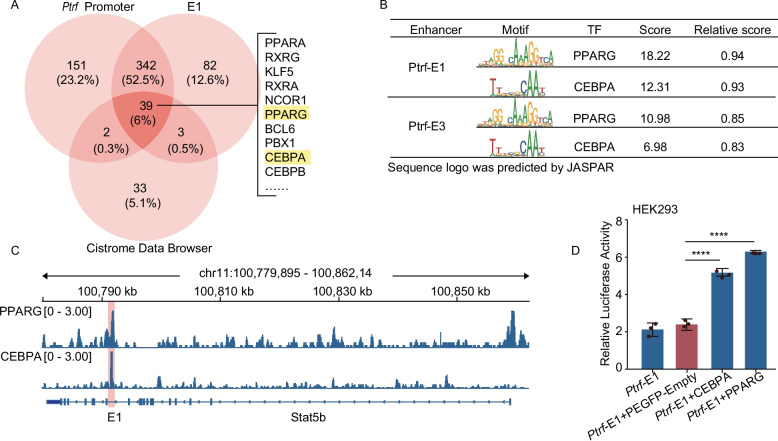

Adipogenesis is a complex cellular process that is tightly regulated by several TFs [59–61] that bind to specific sequences in promoter-proximal and -distal DNA elements to modulate transcriptional activity [62, 63]. Next, we examined the potential involvement of TFs in the activity of E1. Then, 381 TFs that may bind simultaneously to the promoter of Ptrf and E1 were predicted based on the JASPAR and hTFtarget databases. After tracking and downloading ChIP-seq data from TFs in adipocytes using AnimalTFDB3, only 39 TFs were present in all three databases (Fig. 6A and Additional file 16: Table S8). As expected, we found an overlap across the three databases of the adipogenic TF peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (Cebpa) motifs in E1 (Fig. 6B). We further used publicly available ChIP-seq data to visualize the binding of different TFs to the E1-enhancer region in mouse adipose cells (Fig. 6C). Pparg and Cebpa enrichment were observed in the E1 region. Furthermore, to determine whether Pparg and Cebpa induce Ptrf expression, we examined the effects of these TFs on enhancer region activity using dual-luciferase reporter assays. Pparg overexpression induced a 2.64-fold increase in luciferase activity, and Cebpa overexpression induced a 2.17-fold increase, indicating that both Pparg and Cebpa participate in enhancer activity (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Identification of transcription factors binding to enhancers of Ptrf in adipocytes. A Venn diagram comparing the TFs that were common and unique between Ptrf and Ptrf-E1 in 3T3-AD. TFs were predicted by JASPAR, hTFtarget, and AnimalTFDB. Cistrome Date Browser provides ChIP-seq data sources of TFs that have been studied so far. B PPARG and CEBPA TFs motif enrichment analysis of putative active enhancer regions of Ptrf. C Profiles of PPARG and CEBPA transcription factors in the Ptrf-E1 region were shown according to previously published ChIP-seq data, the pink column indicated Ptrf-E1 regions. D The constructed pGL3-Ptrf-promoter-E1 (Ptrf-E1), PEGFP-Empty, and CEBPA/PPARG overexpression vector transfected into HEK293 cells with the renillaluciferase control reporter vector as an internal control. Results were represented as mean ± SD. Two-tailed t test was used for comparison among each group, ****p < 0.0001

Discussion

Adipose tissue (AT) is a unique endocrine organ that plays a crucial role in various physiological processes, including thermogenesis and the regulation of metabolic homeostasis [64, 65]. Excessive fat mass is an important risk factor for a range of health issues in humans [66, 67]. The targeted modification of gene expression related to adipogenesis has been considered as a potential strategy for managing fat mass [6, 7]. Although an integrative analysis of genomic data has identified promising causal genes related to adipogenesis [68, 69], it remains to be elucidated which genes exhibit a dose-dependent relationship between gene transcription and phenotype.

Adipocyte differentiation determines the expandability of AT, which is significantly affected by Ptrf gene expression [19, 25]. However, the precise relationship between Ptrf mRNA expression and fat deposition phenotypes is not fully understood. In recent years, extensive research has been conducted using high-resolution single-cell and single-nucleus transcriptomic assays to study cellular heterogeneity and functionally relevant gene expression profiles within adipocytes [70–72]. SnRNA-seq was utilized to delve deeper into the mechanisms driving reduced fat mass in Ptrf−/− mice. We identified four functionally distinct adipocyte subtypes, one of which, AD3, as a unique cell subtypes exclusively emerging in Ptrf-knockout models. The resultant metabolic crisis is manifested as fatty acid oxidation abnormalities, lipid synthesis obstruction, systemic insulin resistance, and dysregulation of adipokines (leptin, adiponectin) (Additional file 3: Fig. S3). SnRNA-seq reconstruction of AD3 gene regulatory networks (GRNs) has identified profound rewiring of lipogenic regulators (Cebpa↓, Pparg↑) coupled with activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathways (Jun↑, Atf1↑). This transcriptional shift creates a self-reinforcing loop driving pathological lipid redistribution.

Our study provides the first single-cell resolution atlas of adipocyte development in Ptrf-knockout mice, revealing critical cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying adipogenesis. Ptrf orchestrates multiple facets of adipocyte biology, including differentiation competence, lipid uptake efficiency, and triglyceride biosynthesis. Mechanistically, the Ptrf knockout induced profound membrane ultrastructural defects (Fig. S1D), including complete caveolae loss. This architectural collapse fundamentally impairs lipid trafficking capacity, as evidenced by reduced plasma triglyceride levels (Δ = 0.25 mmol/L, p = 0.0016). Beyond its canonical role in caveolae biogenesis [73, 74], Ptrf has characteristics of pleiotropic functions spanning ribosomal RNA transcription [75, 76], mechanical stress adaptation [77], oxidative stress response [78], and exosome-mediated intercellular communication [16, 79–81]. These diverse roles position Ptrf as both a structural scaffold within the plasma membrane lipid bilayer and a signaling hub integrating metabolic responses. However, these preliminary findings primarily derive from bioinformatics analyses and limited by a small sample size, and require more rigorous experimental validation.

Ptrf could serve as a promising target for modulating fat mass. To further explore the relationship between Ptrf mRNA expression levels and adipose mass as well as adipocyte size, we generated five genotypic mice with varying levels of Ptrf mRNA expression using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Our results demonstrated a positive correlation between higher relative Ptrf mRNA expression and increased body fat, fat pad size, and body weight in mice. The complete knockout of protein-coding genes often has deleterious pleiotropic effects, with long-term consequences at every stage of the life cycle and widespread effects in each tissue type [82–84]. By contrast, CRE modification has promising potential for fine-tuning gene expression. More precisely, it has clear advantages over conventional methods, and can use CREs to orchestrate gene-specific expression in different tissues. Furthermore, CREs are likely to be easily accessible for the CRISPR/dCas9 system because of their open chromatin [85, 86]. dCas9–KRAB is currently a widely used tool for blocking transcription around a window of transcriptional regulatory elements [87–89]. Using 4C- and ChIP-seq data, we identified six candidate enhancers of Ptrf with H3K27ac and H3K4me1 enrichment, thus suggesting the importance of these regions as putative enhancers. In the present study, Ptrf mRNA expression was markedly inhibited by dCas9–KRAB suppression of E1, E3, and E5 in mature adipocytes. Furthermore, the inhibition of E1, E3, and E5 induced a reduction in triglyceride accumulation and in the ratio of differentiated adipocytes. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated the key roles of enhancers in the regulation of gene expression [90].

On the basis of these results, we performed a direct injection of CRISPR-activation lentivirus into AD. Although the disturbance of all three enhancers inhibited gene expression, adipose deposition, and body weight, only the results from E1 and E3 were significant in vivo. Ptrf-E1 (in the intronic region of Stat5b, located − 178 kb downstream of Ptrf) had the strongest influence on Ptrf mRNA expression. Interestingly, all three experimental groups received equivalent volumes of lentiviral particles at identical time points during the intervention. However, significant body weight disparities emerged between the E1 and Con1 groups after 5 weeks of high-fat diet (HFD) exposure, whereas the E3 and Con2 groups showed differences at 9 weeks post-HFD initiation (Fig. 5C). Ptrf expression in iWAT showed a 2.77-fold reduction in the E1 group compared to Con1, with enhancer repression in E1 demonstrating the most pronounced transcriptional suppression effect. The sustained suppression of E1 mediated by dCAS9-KRAB epigenetic editing induced Ptrf downregulation, E1 and Con1 groups showed the earliest significant expression. This differential Ptrf expression reached a critical threshold sufficient to drive phenotypic divergence in body weight by week 5, but E3 and Con2 groups reached phenotypic divergence in body weight by week 9. As body weight regulation constitutes a polygenic quantitative trait [14]. Our findings demonstrate that the gene transcription level of Ptrf was found to significantly contribute to body weight variations.

Enhancers function as integrated platforms for the binding of cell-type-specific TFs, co-regulators, and chromatin modifiers to modulate target gene transcription [91, 92]. In the present study, we also demonstrated the close binding of Pparg and Cebpa to the E1 enhancer, and revealed that the overexpression of each of these two TFs increased luciferase activity in the luciferase reporter assay.

Conclusions

Taken together, we have revealed mechanism underlying Ptrf deletion-induced fat mass decreases in mice, and identified a novel enhancer governing the expression of Ptrf. Our findings indicate that decreasing Ptrf expression, rather than completely removing Ptrf, maybe a candidate strategy for reducing fat accumulation.

Methods

Generation of gene-edited mice

C57BL/6 mice were grown and kept in a clean-grade animal room with ad Libitum access to rodent chow diet and water, at 22℃ and humidity (60%) under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Four different genotypic mice were constructed via CRISPR/Cas9 system. The Ptrf gene (NCBI Gene ID 19285) is located on chromosome 11, which contains 2 exons and 1 introns. The Ptrf−/− mouse model was generated in our previous study [28]. For the KI model, murine Ptrf CDS driven by the CAG promoter (“CAG promoter-Kozak-mouse Ptrf CDS-rBG pA” cassette) was constructed and inserted into the ROSA26 locus. A schematic diagram of the targeting gRNAs and the editing strategy was shown in Fig. 1A. Target sequences of single guide RNAs (sgRNA) pairs for Ptrf−/− mice were Listed in Additional file 14: Table S6. The pups were genotyped by PCR followed by sequencing analysis (Additional file 5: Fig. S5; Additional file 8: Fig. S8; Additional file 15: Table S7). All procedures were performed according to the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (Ministry of Science and Technology, China, revised in March 2017) and approved by the animal ethical and welfare committee (AEWC) of Sichuan Agricultural University under permit No. DKY-B2019102012.

Histology staining of adipose tissues

Following anaesthetization of 1.5% isoflurane and euthanasia, the fresh WAT were rapidly removed from adult mice, and fixed with fatty tissue fixative solution (Phygene, China) for 48 h at 20 ℃. Sucrose dehydration was conducted, and sucrose gradients were 20%, 30%, and 45% for every gradient for 24 h at 20 ℃. Then, adipose tissue was embedded into OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical, Japan) which was pre-cooled to − 30 ℃. Samples were sectioned into 10-μm slides, and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). The adipocyte cross-sectional area (μm2) and diameter (μm) were quantified by manually delineating adipocytes using ImageJ software. A total of over 1000 adipocytes per genotype (n = 5200 morphologically intact adipocytes per mouse) were randomly selected.

Blood biochemistry testing

In order to obtain accurate blood biochemical values, mice were housed individually, and measured after overnight fasting for more than 12 h. Blood sample (100 µL) was drawn from the retro-orbital sinus and collected into Heparin-anticoagulated sterile tubes. After Centrifugation at 1200rpm for 5 min at 4 ℃, the supernatant was stored at 4 ℃ until analysis. The separated serum was analyzed for triglyceride, blood glucose, and cholesterol levels using an automatic biochemistry analyzer (Noahcali-100 clinical veterinary auto chemistry analyzer, Tianjin, China) and the corresponding small animal-specific test discs. The dCas9-KRAB mice in each group exhibited no differences in blood glucose and triglyceride levels at 17 weeks (Additional file 13: Table S5).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Mice were subjected to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening. A conventional whole-body 0.3 T MRI scanner (VET-0.3T, NingBo ChuanShanJia Electrical and Mechanical, China) was used to measure body composition, with following the parameter: TR/TE, 3000/90 ms, slice thickness 3 mm, interval 0.1–0.2 mm.

Transmission electronic microscope examination

The iWAT was cut into small pieces of approximately 2 mm3 and fixed in a pre-cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative solution. Then, subjected to gradient sucrose dehydration. Ultrathin Sects. (50 nm) were cut with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut E, Leica) and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Microscopy was performed with a JEOL JEM-1400 Plus transmission electron microscope.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen, USA), and reversely transcribed to cDNA using HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR kit (Vazym, China) just like we mentioned in the previous report [93]. qRT-PCR was performed with specific primers (Additional file 15: Table S7) and qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme, China) on an ABI 7500 system (ABI, USA). Each sample was run in triplicates. Gene expression was analyzed using the 2−∆∆CT method [94].

Western blotting

The inguinal adipose tissue from the lentivirus injection mice was washed with cold PBS and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Millipore, USA). Protein concentration was determined by the BCA kit (Suolaibao, China). Equivalent amounts of protein were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were incubated with PBS (0.05% Tween 20, 5% BSA) to block nonspecific binding and were incubated with primary antibodies, then treated with appropriate secondary antibodies. After this, the bands were visualized using ECL. The primary antibodies were PTRF polyclonal antibody (PA5-68,780, ThermoFisher, USA), and Goat Anti-Rabbit (ab6721, Abcam, UK). In addition, the quantitative gray value of the WB strip was by using the software ImageJ. The results were expressed as the gray value of the target band divided by the gray value of the reference protein (Anti-beta Actin (ab-8226, Abcam, UK); Goat Anti-Mouse (ab6789, Abcam, UK)). The antibody dilution was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The gel image had high-contrast and the original gel image included in the Additional file 8:Fig. S8.

Tissue preparation and snRNA-seq library construction

SnRNA-seq samples were extracted from iWAT of 6-month-old mice (n = 2). Tissues were isolated immediately and stored in the sCelLiveTM Tissue Preservation Solution (Singleron Biotechnologies, China) on ice after the surgery within 30 min. The samples were washed in pre-cooled PBSE three times, minced into small pieces, and then dissociated into nuclear suspensions using GEXSCOPE® Nucleus Separation Solution (Singleron Biotechnologies, China) refer to the manufacturer’s product manual. The mixture was then Centrifuged at 300g, 4 ℃ for 5 min to remove supernatant and resuspended in PBSE to 106 nuclei per 400 μL. The isolated nuclei suspension was collected and filtered through a 40-µm sterile strainer. Finally, cell number and cell viability were measured by Trypan blue staining microscopically. Nuclei were counted in Luna Cell Counter and a nuclear density of 3–4 × 105 nuclei/mL were loaded onto a microfluidic chip (GEXSCOPE® Single NucleusRNA-seq Kit, Singleron Biotechnologies) and snRNA-seq libraries were constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Singleron Biotechnologies, China).

Barcoding beads were subsequently collected from the microwell chip, followed by reverse transcription of the mRNA captured by the barcoding beads to obtain cDNA, and PCR amplification. The amplified cDNA was then fragmented and Ligated with sequencing adapters. Individual Libraries were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with 150-bp paired-end reads.

Ambient RNA and doublet removal

Raw reads from snRNA-seq were processed to generate generating count matrixes using CeleScope (v1.14.1) pipeline with default parameter. Briefly, gene expression data were corrected using SoupX (v1.16.2) to remove of ambient RNA signatures. Filtering of low-quality cells. For each sample, we performed doublet removal using DoubletFinder (v2.0.3). DoubletFinder was run for each sample using principal components 1–20. nExp was set to 0.08 × nCells2/10,000, pN to 0.25 and pK to 0.09. Cells classified as doublets were then removed before additional analysis.

Cell clustering and integration in snRNA-seq data

After filtering ambient mRNA and doublet cells for each sample, all samples were merged into a Seurat (v4.3.0) object. Select feature RNA > 300 &percent. mt < 20 &percent. HB < 1 & nCount RNA > 1000 cells. A total of 21,460 nuclei (Ptrf−/−: 9,497, WT: 11,963) were retained for the downstream analyses. Then, the standard process of Seurat was used for processing. Data from different samples were normalized using the NormalizeData function with default options, and the top 2000 most variable genes of each sample were calculated by the VariableFeatures method. Principal component analysis was performed with 2000 variable genes using the “RunPCA” function. The R package harmony (v1.0.3) was performed to batch effect removal (RunHarmony function).

Seurat FindNeighbors (reduction = “harmony”) FindClusters (resolution = 0.15) to cluster cell. Clusters were identified with the Seurat functions FindNeighbors and FindClusters. Cluster-specific marker genes were unbiasedly analyzed using the “FindAllMarkers” function in Seurat. The detailed parameter test. Use = Wilcox, min. pct = 0.1, logfc.threshold = 0.25 to find all markers for each cluster. Next, cluster identities were annotated based on top-ranked marker genes, as well as the expression of canonical marker genes as described in the manuscript. The cell clusters were visualized using the UMAP plots.

SnRNA-Seq differentially expressed genes analysis

Differential gene expression testing was performed using the FindMarkers function to identify specific marker genes for each adipocyte subtype in Seurat based on the Wilcoxon rank sum test, |Log2(FoldChange)|≥ 0.25 and adjusted p values ≤ 0.05 considered as the criterion to evaluate the statistical significance. The functional parameters we used in Seurat (v4.3.0) were default values.

Functional enrichment analysis

Differentially expressed terms were obtained via over-representation enrichment analysis (ORA, https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/) from the R-package clusterProfiler, based on the Gene Ontology (GO, https://www.geneontology.org) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, https://www.genome.jp/kegg) pathway databases.

Pseudotime analysis

The Monocle2 R package (v2.24.1)[95] was used to analyze the single-nucleus trajectories of the differentiation process of pre-AD and 4 adipocyte subtypes. The differentialGene Test function was implemented to identify differentially expressed genes (q value < 0.001) across cluster transitions along pseudotime. The expression dynamic expression heatmap was generated by using the plot_pseudotime_heatmap function with default settings. The DDRTree method was used to reduce the dimension of the dataset, and the plot_cell_trajectory function was used to visualize the pseudotime trajectory. Genes that were differentially expressed along the cell-to-cell distance trajectory were mapped on the pseudotime path. Next, the Branch expression analysis modeling (BEAM, v2.12.0) method was applied to find genes with branch-specific expression patterns. Only genes with an adjusted p values < 0.05 were further considered. Clustering was performed using the k-means clustering algorithm implemented in R.

Evaluation of metabolic pathway activity

ScMetabolism (v0.2.1) (https://github.com/wu-yc/scMetabolism) was used to integrate dropout gene imputation, metabolism quantification, and data visualization, and yielded significant insights into metabolic pathway activity [96]. The single-cell metabolic landscape pipeline [40] assessed the metabolic pathway activity score based on the relative gene expression averaged across all genes within each pathway. The metabolic genes identified in adipocyte subtypes were utilized in a t-SNE analysis to visualize the impact of metabolic genes on cell states. The single-nuclei metabolic activity score was defined as the average of the relative gene expression values across all genes in a given metabolic pathway. The KEGG metabolism gene sets encompass 84 metabolic pathways and 1667 metabolic genes. Higher scores indicate higher activity of the corresponding metabolic processes.

Prediction of gene regulatory networks using SCENIC

Regulon analysis was performed using the SCENIC (v1.3.1), a computational method to map gene regulatory networks and identify stable cell states from single-nucleus RNA-seq data [97]. Briefly, we first inferred the potential regulatory relationship between transcription factors and potential targets using the R package GENIE3. Then, the enrichment of TF binding motifs was performed using the R package RcisTarget. Only the target genes enriched with the motifs of the corresponding TFs were selected as candidate target genes, removing those target genes without motif support. The genomic regions for TF-motif search were Limited to 10 kb centered around the transcription start site. We next scored regulon activity (RAS) for each cell in the data using AUCell. The RAS for each regulon was converted to regulon specificity scores (RSS) using the “calcRSS” function in the SCENIC. Regulons were then ranked by their RSS to identify highly specific regulons for each subtype. Hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance was performed based on the CSI matrix to identify different regulon modules. The threshold of CSI = 0.3 to build the regulon association network to investigate the relationship of different regulons.

Immunofluorescence analysis

IWAT was collected and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, then processed and embedded in a paraffin block. Sections (5 μm) were obtained using a Leica microtome and placed on Superfrost Ultra Plus slides (Menzel-Gläser, Menzel GmbH, Germany). Tissue sections were deparaffinized and blocked in 10% Rabbit serum (G1209, servicebio, China) for 30 min. The immune markers evaluated included Leptin (GB11309, servicebio, China), Adiponectin (GB115581, servicebio, China), Dock9 (GB114224, servicebio, China), and Ranbp9 (GB113228, servicebio, China). One antigen required one round of labeling, including primary antibody incubation, secondary antibody incubation, and tyramide signal amplification, followed by labeling with the next antibody. The slides were microwave Heat-treated and blocked in 10% rabbit serum after each tyramide signal amplification operation. Nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, G1012, servicebio, China) after all the antigens above had been labeled. After staining, the images were collected using a 3DHISTECH scanner (Pannoramic MIDI). Software CaseViewer (v2.2.1) was used to view the image data (https://www.3dhistech.com/caseviewer).

Cell culture and 3T3-L1 adipogenic differentiation

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293, CRL-1573, American Type Culture Collection, USA) and 3T3-L1 (SCSP-5038, national collection of authenticated cell cultures, China) cells were cultured with basic growth media (DMEM, 10% FBS, and 1% Pen/Strep) at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2.

3T3-L1 cells were seeded and allowed to grow to confluence, and incubated for 48 h with adipogenic induction medium (2 μg/mL of dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, and 10 μg/mL of insulin). Subsequently, 2 days post-induction, the medium was changed to adipogenic maintenance medium (basic growth media with containing 10 μg/mL insulin and 10% FBS), with a change every 2 days. 3T3-L1 cells were maintained in a differentiation medium for 4–6 days for complete differentiation into mature adipocytes.

Oil red o staining and flow cytometry analysis

Oil red o staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s manual (Solarbio, China). Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS, and thereafter 4% paraformaldehyde was added to the fixed for 10 min and stained with freshly prepared 0.6% Oil red o for 15 min, washed twice again. The visualized red oil droplets were observed using a microscope (DMI 4000B, Leica, Germany). The stained Lipid droplets were reconstituted in isopropanol; the contents were analyzed by measuring the optical density at 490nm (OD 490).

At least 10,000 3T3-AD were identified by size (FSC) and granularity (SSC) using a BD FACSVerse™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). The procedure for direct measurement of adipose cell size was according to a previous study [57]. Differentiated cells were collected by enzymatic digestion and washed twice with PBS, and re-suspended gently in ice-cold PBS. Next, flow cytometry analysis of the adipocyte was performed, and single viable cells were gated from FSC-H/SSC-A to exclude debris, and forward and side scatter values were recorded for each cell. 3T3-L1 were used to define negative gate region1 (R1), R1 means the region with the type of cells with the least relative lipid droplet content. Whereas the region2 (R2) and region3 (R3) were defined to represent varying cell diameter and intracellular granularity [58, 98], R3 means the region with the type of cells with the highest lipid droplet content.

Construction of circularized chromosome conformation capture libraries and sequencing

Circularized chromosome conformation capture (4C) libraries preparation was carried out according to Krijger P [99] with some modifications. For mature adipocytes on day 4 after 3T3-L1 differentiation, cells were digested with trypsin and then washed twice, resuspended with PBS, and then stored frozen at 1 × 107 cells/mL in liquid Nitrogen. For the Flash frozen iWAT, eWAT, pWAT, and sWAT of 6-week-old mice, tissues were crushed in liquid Nitrogen, and subjected to the 4C-seq procedure immediately. The outline of the 4C-seq procedure was performed in two replicates as shown in Fig. S5A. The above five types of adipocytes were fixed with 2% formaldehyde. Next, 1 M glycine was added for 10 min to quench the cross-linking reaction. Cells were washed twice with PBS. Cold lysis buffer (protease inhibitors, Tris, NaCl, EDTA, NP-40, TritonX-100) was added to lysed, incubated, and washed to obtain nuclear DNA. The DNA was further digested by DpnII/Csp6I (NEB) overnight. After two digestions, Ligation, and purification. In brief, the 4C library was generated by a two-step PCR strategy. PCR was performed using PhusionDNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific), and after the reaction, the 4 C samples were purified using VAHTS DNA cleaning beads (Vazyme, China). 4 C Libraries were sequenced using single-end 150 bp reads on an Illumina novaseq6000 system (Illumina, CA). Primer sequences were shown in Additional file 17: Table S9.

4C-seq data analysis

Sequencing reads were demultiplexed, trimmed, and aligned using the pipe4C pipeline. The 4C-seq analysis used the pipe4C pipeline [100] and the R-package r3Cseq [101]. Bowtie2 (v2.4.2) maps reads from each replicate to the mouse genome (mm10). For both pipe4C pipeline and r3Cseq, reads corresponding to self-ligated or non-digested fragments were removed. A 2-kb non-overlapping window interval was selected to determine the interaction region. Mapped reads for each window were counted and then normalized to obtain RPM (reads per million per window) values for statistical analysis. Significant interaction regions (q value < 0.05, FDR) were identified using r3Cseq.

Download and analysis of public ChIP-seq data

Publicly ChIP-seq data of adipocytes were downloaded from the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) [102–106]. The detailed information was Listed in Additional file 18: Table S10. ChIP-seq reads were mapped to the reference genome using BWA (v0.7.17). Next, PCR duplicates were removed using Samtools. Peak calling were performed with MACS2 (v2.2.7.1), and q ≤ 0.05 was used as the threshold for significant enrichment. Bigwig files were generated by bedGraphToBigWig (v4) and visualized in IGV (v2.12.3).

Identification of active enhancers of the Ptrf gene

Genomic DNA of 3T3-AD using commercial genomic DNA extraction kits (Tiangen, China). The Primer of Ptrf promoters and candidate active enhancers were designed and confirmed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information primer-blast website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Promoter fragments with a length of around 2 kb were cloned upstream of the luciferase reporter gene in the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega, E1751) at the KpnⅠ site. Candidate active enhancers were likewise amplified and cloned into the SalⅠ sites as shown in Fig. 4B (left), respectively. Final plasmid DNA was prepared with Endo-Free Plasmid Kit (Omega, Madison, WI, USA) and stored at − 80 ℃.

Dual-luciferase reporter assays were used to detect putative enhancer activity in vitro. Then, 100 ng pGL3-promoter-enhancer and 2 ng TK-15 (Promega, E2241) were transfected into HEK293 and 3T3-AD in 96-well plates using Lipofectamine 3000 reagents (ThermoFisher, Germany). TK-15 vector was co-transfected as a control for normalization. Measurement of the luciferase activity was carried out 36 h after transfection by the Dual-Glo luciferase assay kit (Promega, #E2920) on a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase activity of the firefly was normalized by renilla, and relative luciferase activity was obtained as compared with empty pGL3-promoter. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least once. Data were presented as mean ± SD. p values were calculated by the two-tailed t test.

SgRNA design and plasmid preparation

The top three enhancers displaying the highest fluorescence activity (E1, E3, E5) are required to establish long-term repression facilitated by the KRAB-dCas9 system. E1 is located in the intronic regions of Stat5b, E3 is located in the intronic regions of Stat3, and E5 is located in an intergenic region. To rule out the possibility of CRISPRi-induced passive modifications of chromatin states (as suggested by Qi et al.[107], and Tuvikene et al.[108]), we utilized the intronic region of Stat5b/Stat3 and an intergenic region as controls. The position of the enhancers and controls are shown in Additional file 6: Fig. S6A. Additionally, control1, − 2, and − 3 exhibited the absence of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac histone modifications.

SgRNAs were predicted and designed using the ChopChop website (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/). Sequences of all the sgRNAs primers were Listed in Additional file 19: Table S11. The complementary DNA strand was annealed to develop double-stranded and cloned into dCas9-KRAB (pLV-hU6-sgRNA-hUbC-dCas9-KRAB-T2a-Puro, Addgene, No. 71236) vector. Off-target binding sites were checked via CRISPOR online software (http://crispor.tefor.net/), and Sanger sequencing of these sites detected no off-target effects. Final plasmid DNA was prepared with Endo-Free Plasmid Kit (Omega, Madison, WI, USA)and stored at − 80 ℃.

Lentivirus production, cell transduction and CRISPR-mediated enhancer inhibition

Briefly, lentiviral backbone expressing dCas9-KRAB with pAX (packaging) and pCMV-VSVG (envelope) plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293 packaging cells using the calcium phosphate methods. The supernatant containing virus particles was collected every 24 h for 72 h, filtered through a 0.45 μm (Thermo Fisher Scientific) filter to remove cellular debris, and then concentrated with centrifugal filter tubes (Millipore, 100KD). Lentiviral preparations were kept at − 80 ℃ until use.

Moreover, 1 × 105 cells were seeded on each twelve-well plate and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Reaching about 60% fusion, the 3T3-L1 cells were transduced with lentiviral sgRNAs in a 1:1 mix of fresh medium and lentiviral supernatant (4 × 106 transduction units/mL). One day later, 2 μg/mL of puromycin (Sigma, USA) was added to the 3T3-L1 culture medium to select for constitutive expression for 48 h. Then, the cell culture medium was replaced with basic growth media containing 1 μg/mL of puromycin for 1 week. Infected cells were seeded in a 12-well plate, and adipocyte differentiation was induced for 6–8 days.

Male mice were fed a high-fat diet (HFD, 60% fat, D12492, Research Diets, Inc.) at 6 weeks old, and allocated randomly divided into six groups, ensuring the mean body weight in each group was similar. Mice were injected with lentivirus expressing dCas9-KRAB-GFP-sgRNA or a negative control virus every 4 days at the age of 9 weeks (Fig. 5B), with a total of four times injections. Each mouse was injected with lentivirus (200 μL, 1 × 106 TU/mL) at 3 points of the groin subcutaneous white adipose tissue per side. Successful transduction was confirmed by the detection of GFP and dCas9-KRAB signals (Additional file 7: Fig. S7B, C, and D). No significant difference was observed in the average food intake among the three groups of mice (Additional file 7: Fig. S7E). The mice in each group exhibited no differences in blood glucose and triglyceride levels at 17 weeks. Additionally, the glucose tolerance test (GTT) conducted at that time revealed no significant differences compared to the control group (Additional file 7: Fig. S7J and K). Five weeks later, sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and tissues were rapidly isolated and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 ℃ until further biochemical analysis.

Quantitative assessment of transcription factor activity

The coding sequence (CDS) of 3T3-AD was synthesized by reverse transcription using HiScript ® II Q Select RT SuperMix from the qRT-PCR kit (Novozymes, China). CDS of Pparg and Cebpa were amplified and ligated into pEGFP-N1 vector at KPNⅠ restriction sites using a Trelief™ SoSoo Cloning Kit (Tsingke, China), respectively. Candidate active enhancers were amplified and cloned into the pGL3-promoter vector. Constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Fifty nanograms of pGL3-promoter-enhancer, pEGFP-N1-PPARG/CEBPA or pEGFPN1 control, and 2 ng TK-15 (Promega, E2241) were transfected into HEK293 in 96-well plates using Lipofectamine 3000 reagents (ThermoFisher, Germany). After 48 h of transfection, Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was measured by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The chromosome coordinates, primer sequences, and Linker sequences were provided in Additional file 20: Table S12.

TF motif enrichment analysis

TF motif enrichment analysis was performed using hTFtarget (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/hTFtarget/) [109], the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) [110], and AnimalTFDB 3.0 (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/AnimalTFDB/tfbs_predict) [111] with default parameters by input FASTA format of the enhancers. TF motifs with p < 0.05 were identified as enriched motifs (Additional file 16: Table S8). Cistrome Data Browser [112] provided the ChIP-seq sources.

Statistical analysis

All of the data obtained in this study were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (v6.00). Statistically significant p values were indicated in *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1 Characterization of iWAT in Ptrf−/− mouse model.Mouse body weight measurementsand morphologyfor WT and Ptrf−/− mice..The relative ratio of sWAT, eWAT, and iWAT to body weight in WT and Ptrf−/− mice.Adipocyte diameter distribution of iWAT in WT and Ptrf−/− mice. Representative sections of iWAT were displayed in the upper.Electron micrographs of fat in WT and Ptrf−/− mice. An abundance of caveolaewas observed close to the adipocyte membrane in WT fat, while, adipocyte membrane from Ptrf−/− mice was nearly flat, and the caveolae density was greatly reduced.Triglyceride, blood glucose, and cholesterol levels of WT and Ptrf−/− mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and 'NS' means no significance.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. The cellular heterogeneity of iWAT.Bubble plot showing the expression of cell type-specific marker genes for each cluster of nuclei. Adipocyteshighly express Adipoq, Plin1, Lipe; Pre-adipocyteshighly expressing Pparg, Fabp4, Adipoq; Fibro-adipogenic progenitorshighly expressing Pdgfra, Dcn; Epithelial cellshighly expressing Epcam, Cdh1, Esrp1; Macrophages highly expressing Mrc1, F13a1, Adgre1; B cells highly expressing Bank1, Ms4a1, Ighm; T cells highly expressing Skap1, Lef1, Cd247; Pericytes highly expressing Acta2, Tagln; Dendritic cellshighly expressing Fscn1, Flt3, Ccr7. The color indicated the scaled mean expression of marker genes, and the size indicated the proportion of nucleus expressing marker genes.UMAP plot displaying the marker gene expression of cell clusters from snRNA-seq libraries.Functional annotation of each annotated cell types. Left: Heat map showing the expression levels of cell type-specific maker genes. Right: representative enriched terms for each cell type were listed.Number of DEGs in each cell type. |Log2|≥ 0.25 and adjusted p-values ≤ 0.05 were used to identify DEGs.The top 20 enriched GO and KEGG terms of up-regulatedand down-regulatedDEGs of ADs.Heat map showing scaled average expression of four typical adipocyte markers across adipocyte subtypes.Dendrogram was generated by performing hierarchical clustering on the average gene-expression profiles for adipocyte subtype.Heatmap showing average scaled expression of adipocyte subpopulation markers.Representative image of immunofluorescence staining of ADIPOQ, LEPTIN, DOCK9, RANBP9, and DAPI staining, Original magnification, × 20.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Metabolic pathway analysis of adipocyte subtypes.The hierarchical clustering of four adipocyte subtypes using metabolic pathway activity.UMAP representation of subtypes visualized an adipocyte metabolic activity. Colors illustrate the metabolite intensity. AUC means the activity score of metabolic pathways.The comparison of metabolic pathway activity among adipocyte subtypes. The color scale represents the activities of metabolic pathways.Violinplot showing the metabolic pathway activities of WT and Ptrf in AD1. The average value was shown on the up of the violin.The comparison of metabolic pathway activity between WT and Ptrf−/− in AD1. The color scale represents the activities of metabolic pathways.Expression heatmap of genes in therepresentative pathway term across pseudotime.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4. Phenotypic assessment of Ptrf homozygous knock-in mice, heterozygous knock-in mice, homozygous knock-out mice, heterozygous knock-out mice, and wild-type micemice.Genotyping strategy for Ptrf gene-edited mice. F1/R1 primers were located on both sides of sgRNA1. F2/R2 primers were located on Ptrf CDS and rBG pA. F1/R1 and F2/R2 primers were performed to determine the Ptrf CDS insertion site. F3/R3 primers were located on both sides of sgRNA3. F4/R4 primers were flanking these exon 1 and exon 2. F3/R3 and F4/R4 primers were used to confirm the complete knockout of Ptrf. The light blue area represents exon, the dark blue area represents rBG pA, the light pink area represents CAG promoter, and the red area represents Kozak-mouse Ptrf CDS.Representative images of agarose gel electrophoresis for DKI mice, SKI mice, DKO mice, SKO mice, and WT mice. DKI mice have a 228 bp band; SKI mice have 2 bands: 228 bp and 607 bp; WT-1 mice have a 607 bp band, and indicates no DNA insertion; DKO mice have a 579 bp band; SKO mice have two bands: 579 bp and 692 bp bands, WT-1 mice have a 692 bp band, and indicates no DNA deletion.Ptrf mRNA relative expression level of lung and kidney in each genotypic mice.The body weight of each genotypic mouse at the age of 9 months.Histogram of the iWAT, eWAT, sWAT, and pWAT areaand diameterat the age of 9 months. Results were represented as mean ± SD. Two-tailed t-test was used for comparison among each genotypic mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Additional file 5: Fig. S5. Identification of enhancer-promoter interaction networks.Procedures for 4C-seq library preparation involved fixation and chromatin extraction from adipocyte nuclei. Dpn II, and Csp6 I were utilied in the first and second restriction enzyme steps, respectively. Inverse PCR and index PCR were carried out on small DNA circles to capture Ligated DNA sequences and construct a 4 C sequencing library. Orange arrows in the DpnⅡ and Csp6Ⅰ fragments indicate the positions of reading/non-reading primers used for 4C-seq library amplification.The genomic region, Chr. 11: 100,970,117–100,972,817, containing the transcription start site of Ptrf was schematically shown. The viewpoint area was highlighted in red.Scatter plot showing interactions of Ptrf in two replicates.Circos plots displayed genome-wide interaction sites of Ptrf-promoteron chromosome 11 in 3T3-AD.Relative mRNA expression level of Ptrf following CRISPR-mediated inhibition after 8 days of adipogenic differentiation in 3T3-AD. ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.The schematic diagram illustrated the interaction profile adjacent to three candidate enhancers and Ptrf promoter. Integrative Genomics Viewerwas used to visualize ChIP-seq data of MED1, CTCF, and SMC1of 3T3-AD, the red dotted line represented the viewpoint of Ptrf. The pink column represent the putative active enhancers.

Additional file 6: Fig. S6. Schematic representation of the sgRNAs target and qRT-PCR results of 3 groups.Diagram of the E1, E3, and E5 region positions and the corresponding control showing the location of the sgRNA target. Control1 located in the intronic regions of Stat5b, consistent with E1. Control2 located in intronic regions of Stat3, consistent with E3. Control3 located in an intergenic region, consistent with E5.qRT-PCR analysis of adipogenic markers genes in vitro.

Additional file 7: Fig. S7. The delivery efficiency and phenotypic measurement of CRISPR-mediated mice after lentivirus injection.Relative expression of Ptrf transcripts measured by qRT-PCR in high-fat diet fed mice.The relative expression level of dCas9 transcript in CRISPR-mediated mice after lentivirus injection, n = 3.Mice were 16 weeks old, and photographed under UV light irradiation. Upper panel: saline saline injected, lower panel: GFP lentivirus injected.Amplification plot and melt curve of dCas9 and GAPDH.Average food intake was calculated per mouse, from total consumed per cage per day.Relative expression of Stat5b and Stat3 mRNA following CRISPR-mediated inhibition in 3T3-AD, n = 3.qRT-PCR analysis of adipogenic markers genes in vivo.Isolated iWAT and eWAT from control and CRISPR-inhibited mice at 17 weeks of age.Changes in eWAT and iWAT weight were obvious at the age of 17 weeks.Triglyceride and blood glucose levels.Glucose tolerance testof lentivirus injected mice, n = 10. Results were represented as mean ± SD. Two-tailed t-test was used for comparison among them. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Additional file 8: Fig. S8. Images of the original, uncropped gels/blots.

Additional file 9: Table S1. Identified marker genes in each cell type.