Abstract

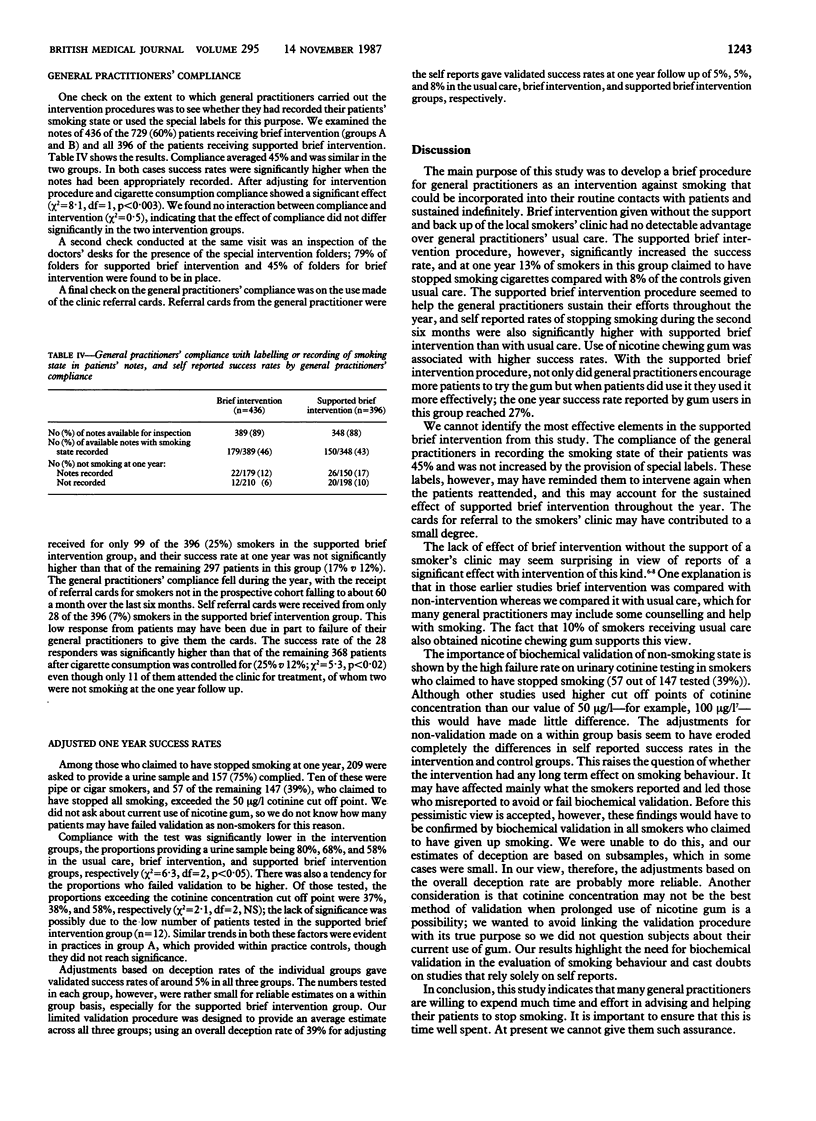

By encouraging and supporting general practitioners to undertake brief intervention on a routine basis smokers' clinics could reach many more smokers than are willing to attend for intensive treatment. In a study with 101 general practitioners from 27 practices 4445 cigarette smokers received brief intervention with the support of a smokers' clinic, brief intervention without such support, or the general practitioners' usual care. At one year follow up the numbers of smokers who reported that they were no longer smoking cigarettes were 51 (13%), 63 (9%), and 263 (8%), respectively (p less than 0.005). After an adjustment was made for those cases not validated by urine cotinine concentrations the respective success rates were 8%, 5%, and 5%. Use of nicotine chewing gum was associated with higher self reported success rates. General practitioners providing supported brief intervention encouraged not only more smokers to use the gum but also more effective use; gum users in this group reported a success rate of 27% at one year. Compliance by the general practitioners in recording smoking state averaged 45%, and significantly higher success rates were reported by patients whose smoking state had been recorded. Brief intervention by general practitioners with the support of a smokers' clinic thus significantly enhanced success rates based on self reports. Better results might be obtained if general practitioners' compliance with the procedure could be improved and if they encouraged more of their patients to try nicotine gum. Collaboration of this kind between a smokers' clinic and local general practitioners could deliver effective help to many more smokers than are likely to be affected if the two continue to work separately.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chapman S. Stop-smoking clinics: a case for their abandonment. Lancet. 1985 Apr 20;1(8434):918–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamrozik K., Vessey M., Fowler G., Wald N., Parker G., Van Vunakis H. Controlled trial of three different antismoking interventions in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 May 19;288(6429):1499–1503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6429.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. Gender and smoking: do women really find it harder to give up? Br J Addict. 1984 Dec;79(4):383–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Merriman R., Stapleton J., Taylor W. Effect of nicotine chewing gum as an adjunct to general practitioner's advice against smoking. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983 Dec 10;287(6407):1782–1785. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6407.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Taylor C., Baker C. D. Effect of general practitioners' advice against smoking. Br Med J. 1979 Jul 28;2(6184):231–235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6184.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]