Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus isolates which produce type A staphylococcal β-lactamase have been associated with wound infections complicating the use of cefazolin prophylaxis in surgery. To further evaluate this finding, 215 wound isolates from 14 cities in the United States were characterized by antimicrobial susceptibility and β-lactamase type and correlated with the preoperative prophylactic regimen. Borderline-susceptible S. aureus isolates of phage group 5 (BSSA-5), which produce large amounts of type A β-lactamase and exhibit borderline susceptibility to oxacillin, comprised a greater percentage of the 120 wound isolates associated with cefazolin prophylaxis than they did of the 95 isolates associated with other prophylactic regimens (25% versus 12.6%, respectively; P < 0.05). In contrast, methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were distributed evenly between the two groups (8.3% versus 11.6%, respectively). In vitro assays demonstrated that cefazolin was hydrolyzed faster by BSSA-5 strains than by other β-lactamase-producing, methicillin-susceptible strains (1.54 versus 0.50 μg/min/108 CFU, respectively; P < 0.0001). These data demonstrate that BSSA-5 strains are a distinct subpopulation of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus which frequently cause deep surgical wound infections. Cefazolin use in prophylaxis is a risk factor for BSSA-5 infection.

Despite the almost universal administration of antimicrobial agents with good antistaphylococcal activity for perioperative prophylaxis in patients undergoing clean surgery, Staphylococcus aureus remains the most common cause of surgical wound infection (22). While methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) accounts for some wound infections, the majority are caused by methicillin-susceptible strains. Although the reasons for breakthrough infections due to apparently susceptible strains are not fully understood, isolates which produce type A staphylococcal β-lactamase have been associated with wound infections complicating the use of cefazolin prophylaxis in surgical patients (9). Type A S. aureus β-lactamase inactivates cefazolin relatively efficiently, conferring a partial resistance to cefazolin that is not easily identified by standard tests for determining antibiotic susceptibility (8–10, 29).

In an effort to correlate patterns of S. aureus resistance with different regimens of perioperative prophylaxis, wound isolates were obtained from 15 hospitals in 14 cities across the United States. These isolates were evaluated by phage typing, MIC determinations, and β-lactamase typing and quantification assays. A subpopulation of methicillin-susceptible staphylococci identified as borderline-susceptible S. aureus typeable with group 5 staphylococcal phages (BSSA-5) and characterized by the production of large amounts of type A staphylococcal β-lactamase and borderline susceptibility to oxacillin were found to be widely disseminated among U.S. hospitals and disproportionately isolated from wound infections of patients who had been given cefazolin prophylaxis. These data suggest that in the perioperative setting, in vivo degradation of cefazolin may enable BSSA-5 strains to survive beyond the time of initial lodgement in wound tissues and, ultimately, to cause infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Between late 1985 and early 1991, a total of 273 isolates of S. aureus associated with deep surgical wound infections that developed after clean surgical procedures were collected by, referred to, or solicited by the authors. A deep wound infection was defined as a postoperative infection requiring surgical incision and drainage for treatment. Of the β-lactamase-producing strains, specific information on the patient’s perioperative antibiotic regimen was available for isolates recovered from 215 deep wound infections. The sources and corresponding numbers of these isolates are shown in Table 1. All isolates were confirmed to be S. aureus by established methods, including colony morphology, Gram stain characteristics, the presence of catalase activity, and the ability to coagulate rabbit serum (11).

TABLE 1.

Sources of S. aureus wound isolates

| City | Total no. of isolates | No. of MRSA isolates (%) | No. of BSSA-5 isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nashville | 64 | 2 (3.1) | 14 (21.9) |

| Bostona | 34 | 3 (8.8) | 4 (11.8) |

| Salt Lake City | 33 | 3 (9.1) | 10 (30.3) |

| Portland, Maine | 16 | 0 (0) | 6 (37.5) |

| Houston | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Omaha | 13 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) |

| Buffalo | 7 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) |

| Columbia, Mo. | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) |

| Portland, Ore. | 7 | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Chattanooga | 6 | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Montgomery, Ala. | 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) |

| New York City | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0) |

| Seattle | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Memphis | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 215 | 21 (9.8) | 42 (19.5) |

Isolates from two Boston hospitals were evaluated.

Reference strains that produce different variants of staphylococcal β-lactamase were used as controls for β-lactamase typing, as well as in cefazolin degradation assays and time-kill survival studies. These included PC1(pI524) and NCTC 9789, which produce type A β-lactamase; 22260 and ST79/741, which produce type B β-lactamase; 3804 and RN9(pII147), which produce type C β-lactamase; and FAR10 and NCTC 9754, which produce type D β-lactamase (8–10, 12, 17, 19, 20, 29). NCTC 10972, the propagating strain for phage 96, was used as a representative BSSA-5 strain (1, 15), and ATCC 6538P was employed as a non-β-lactamase-producing control.

Antibiotic preparations and media.

Standard powders of nitrocefin (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), cephaloridine (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.), methicillin, oxacillin (both from Bristol Laboratories, Syracuse, N.Y.), penicillin G, cefazolin (both from Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Ind.), and clavulanic acid (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pa.) were used to prepare antimicrobial solutions for susceptibility testing, β-lactamase typing, and antibiotic degradation assays. Tryptic soy agar and broth and Mueller-Hinton agar and broth were purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). Modified 1% CY-Tris agar with and without 0.5 μg of methicillin per ml was prepared as previously described (10, 17).

Susceptibility determinations.

Microdilution MICs were determined in accordance with methods described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (16). Cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth with and without 2% sodium chloride was used for determinations with standard (5 × 105 CFU/ml) and large (5 × 107 CFU/ml) inocula, respectively. Trays were incubated at 35°C, and the results were recorded at 24 h.

β-Lactamase typing and quantitation.

The type and amount of β-lactamase produced by each strain following β-lactamase induction by growth on agar containing 0.5 μg of methicillin per ml were determined using whole-cell suspensions of bacteria, as previously described (10). Hydrolysis assays were performed with 100 μM solutions of nitrocefin, cefazolin, and cephaloridine and a 500 μM solution of penicillin G at 37°C in 1-cm-light path cuvettes in a DU-70 recording spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.). Quantitative rates were corrected for small variations in the absorbance at 272 nm (A272) of different whole-cell preparations and reported as micromoles (or micrograms) of substrate degraded per minute per standard cell mass (A272 = 1.0, or approximately 108 CFU).

Phage typing.

Bacteriophage typing was performed with the international set of phages at the standard test dilution and 100-fold routine test dilution concentrations (25). The following phages were used: lytic group 1 phages 29, 52, 52A, 79, and 80; lytic group 2 phages 3A, 3C, 55, and 71; lytic group 3 phages 6, 42E, 47, 53, 54, 75, 77, 83A, 84, and 85; lytic group 5 phages 94 and 96; and nonallocated phages 81 and 95.

Antibiotic degradation assays.

After growth on tryptic soy agar for 18 h at 37°C, colonies of S. aureus were suspended in 15 ml of 2% salt-supplemented, cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth and adjusted spectrophotometrically to a density of 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml. Cefazolin was added immediately to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Mixtures were incubated at 37°C, and 2-ml aliquots were withdrawn at 6, 12, and 24 h for determination of residual cefazolin levels. Each sample was immediately filter sterilized (0.2-μm-pore-size filter), and 20-μl portions were added to 6-mm-diameter paper discs (BBL) previously impregnated with 0.08 μg of clavulanic acid, a manipulation which was shown to be necessary and adequate to prevent further β-lactamase-mediated degradation of cefazolin. Cefazolin levels were determined by bioassay methods using antibiotic medium 1 (Difco) and S. aureus ATCC 6538P as the indicator organism (3).

Definitions.

S. aureus isolates were classified as either susceptible to penicillin G (MIC, ≤0.12 μg/ml), penicillin resistant and methicillin susceptible (penicillin G MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml; methicillin MIC, ≤8 μg/ml), or methicillin resistant (MIC, ≥16 μg/ml) by using recommended criteria (16). Strains susceptible to penicillin G were not evaluated further. The penicillin-resistant, methicillin-susceptible isolates were grouped on the basis of whether they exhibited the borderline-susceptible phenotype. Isolates were designated BSSA if they exhibited penicillin G MICs of ≥64 μg/ml, oxacillin MICs of 0.5 to 4.0 μg/ml, and methicillin MICs of 2 to 4 μg/ml and had nitrocefin degradation rates of >0.060 μmol per min per standard cell mass (with A272 = 1.0) (1, 14, 15). BSSA isolates typeable with phage 94 and/or phage 96 were designated BSSA-5.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons of the rates of cephalosporin hydrolysis and MICs were performed with the two-sample t test and the Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. Comparisons of differences in the proportions of BSSA-5 strains from various sources were determined by performing chi-square analyses with Yate’s correction. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Distribution of MRSA and BSSA-5 isolates among wound infections.

Of the 215 S. aureus wound isolates from 15 hospitals in 14 cities, 21 (9.8%) were identified as MRSA (Table 1). Fifty-one of the isolates were typeable with phage 94 and/or phage 96 at either the routine dilution (45 isolates) or a 100-fold phage concentration (6 isolates). Strains typeable at the routine dilution were more likely than strains typeable only at a 100-fold phage concentration to exhibit the borderline-susceptible phenotype (41 of 45 versus 1 of 6, respectively; P < 0.0005, two-tailed Fisher’s test). Compared to phage group 5 strains, the borderline-susceptible phenotype was observed infrequently among other S. aureus strains; only 4 (2.6%) of the 152 penicillin-resistant, methicillin-susceptible non-phage group 5 isolates met the criteria for borderline susceptibility to the antistaphylococcal penicillins. Overall, 42 (19.5%) of the 215 isolates were typeable with group 5 phages and exhibited borderline susceptibility (i.e., were BSSA-5). At least one MRSA strain was identified among isolates from 10 of the 15 hospitals. Isolates from 10 hospitals, including all 8 of the hospitals from which at least six cefazolin-associated wound isolates were available for evaluation, were identified as being BSSA-5.

Association with prophylactic regimens.

One hundred and twenty isolates were recovered from wound infections complicating perioperative prophylaxis with cefazolin (Table 2). Ninety-five wound isolates were recovered from patients on other prophylactic regimens, including cefamandole (53 isolates), cefuroxime (20 isolates), vancomycin (6 isolates), cefoperazone (4 isolates), cefonicid (2 isolates), cefotetan (2 isolates), cefoxitin (1 isolate), ceftizoxime (1 isolate), and no prophylaxis (6 isolates). BSSA-5 isolates were recovered more often from cefazolin-associated wound infections than from infections complicating other prophylactic regimens (25.0% versus 12.6%, respectively; P < 0.05, chi-square with Yate’s correction). In contrast, MRSA isolates were distributed evenly between the two groups (8.3% versus 11.6%, respectively). If the MRSA isolates are excluded from this analysis, cefazolin prophylaxis and the isolation of BSSA-5 isolates from the wound infection remain significantly associated (P < 0.05, chi-square with Yate’s correction). Because of the large number of isolates from Nashville, the association of BSSA-5 isolates with cefazolin prophylaxis was analyzed for hospitals outside of Nashville. Twenty-four percent of isolates associated with cefazolin prophylaxis were BSSA-5, versus 10.9% of isolates associated with other prophylactic regimens (P = 0.068, chi-square with Yate’s correction).

TABLE 2.

MRSA and BSSA-5 isolates recovered from surgical wounds

| Isolate source | Total no. of isolatesa | No. of BSSA-5 isolates (%) | No. of MRSA isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound infection of patient on: | |||

| Cefazolin prophylaxis | 120 | 30 (25.0)b | 10 (8.3) |

| Other prophylaxis | 95 | 12 (12.6)b | 11 (11.6) |

| Any wound infections | 215 | 42 (19.5) | 21 (9.8) |

Penicillin-susceptible isolates were excluded from analysis.

P = 0.036, chi-square, Yate’s corrected.

Correlation between MICs, rates of cefazolin degradation, and kill-kinetic assays.

The MICs and cefazolin hydrolysis rates of the 21 MRSA, 42 BSSA-5, and 152 penicillin-resistant, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strains were compared (Table 3). BSSA-5 isolates were significantly more resistant to cefazolin than the other methicillin-susceptible strains. The rate of cefazolin hydrolysis was significantly higher for BSSA-5 than for either MRSA or methicillin-susceptible strains.

TABLE 3.

Cefazolin MICs and degradation of cefazolin by S. aureus

| Subgroup | No. of isolates | MICs of cefazolin with inoculum sizea:

|

Mean hydrolysis rate (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Large | |||

| MRSA | 21 | ≥256c | ≥256d | 0.26 (0.17–0.35)e |

| BSSA-5 | 42 | 4c | 64d | 1.54 (1.36–1.72)e |

| Otherf | 152 | 1c | 4d | 0.50 (0.45–0.55)e |

MIC determinations were performed with standard (5 × 105 CFU/ml) and large (5 × 107 CFU/ml) inocula.

Rates are expressed as micrograms of cefazolin degraded per minute per standard cell mass (A272 = 1.0) with an initial 100 μM (about 45 μg/ml) concentration of cefazolin. CI, confidence interval.

MRSA MIC > BSSA-5 MIC, P < 0.0001; BSSA-5 MIC > “Other” MIC, P < 0.0001.

MRSA MIC > BSSA-5 MIC, P < 0.01; BSSA MIC > “Other” MIC, P < 0.0001.

BSSA-5 rate > MRSA rate, P < 0.0001; BSSA-5 rate > “Other” rate, P < 0.0001.

The “other” subgroup consisted of 152 β-lactamase-producing, penicillin-resistant, methicillin-susceptible isolates that did not meet the criteria for MRSA or BSSA-5. It included 6 phage group 5 strains and 146 non-phage group 5 isolates.

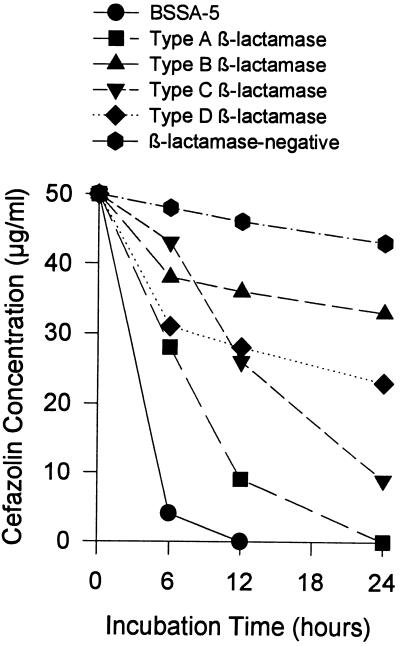

The capacities of BSSA-5 and representative methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strains to inactivate 50-μg/ml cefazolin were compared (Fig. 1). Evaluation of cefazolin inactivation by four additional BSSA-5 isolates and eight non-borderline-susceptible, type A or C β-lactamase-producing strains recovered from wound infections produced similar results, with mean residual cefazolin concentrations of 3.7 and 26.9 μg/ml, respectively, at 6 h (P < 0.005).

FIG. 1.

Time-related inactivation of cefazolin by a BSSA-5 strain and five other methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The strains tested were as follows: NCTC 10972 (BSSA-5), NCTC 9789 (type A β-lactamase), ST79/741 (type B β-lactamase), SA 3095 (type C β-lactamase), NCTC 9754 (type D β-lactamase), and ATCC 6538P (β-lactamase negative). An inoculum of 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml of each strain was added to broth containing 50 μg of cefazolin per ml, and the residual cefazolin concentration was determined at 6, 12, and 24 h.

DISCUSSION

The term borderline-susceptible (or borderline-resistant) S. aureus became popular after the 1986 report by McDougal and Thornsberry on S. aureus strains with a distinctive phenotype which included all of the following properties: (i) borderline oxacillin MICs, (ii) lowering of oxacillin MICs into the clearly susceptible range by β-lactamase inhibitors, (iii) rapid hydrolysis of the chromogenic cephalosporin nitrocefin, and (iv) high penicillin G MICs (14). These strains produced large amounts of β-lactamase. Subsequently, we have shown that isolates with all of these phenotypic characteristics belong almost exclusively to phage group 5 (i.e., phage 94 and/or phage 96), possess a 17.2-kb plasmid, and produce large quantities of type A staphylococcal β-lactamase (1, 7, 15). Portions of this relationship among phage group, borderline susceptibility, presence of a unique plasmid, and hyperproduction of β-lactamase have been noted by others (5, 13, 21, 23, 28), and these isolates appear to represent a distinct subpopulation of S. aureus that is distributed widely among clinical specimens (4, 28). About 85% of phage group 5 strains are borderline susceptible (15). Genetic analyses, including determination of SmaI macrorestriction patterns following pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as well as studies on the size and restriction polymorphism of the internal spacer between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes, indicate that there is a high degree of relatedness among phage group 5 isolates (4).

Terms like borderline resistant, low-level resistant, and borderline susceptible have also been applied to other isolates of S. aureus that do not exhibit high-level β-lactamase production (24, 27). Most of such strains either have alterations in their normal penicillin-binding proteins, such that they have reduced binding affinity for β-lactams (26), or contain mecA, the gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 2a, but exhibit MICs around the breakpoint between the methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant designations (2, 6) rather than the high MICs exhibited by most MRSA strains. Accordingly, to better distinguish isolates with borderline susceptibility due to different mechanisms, in this study we have used the term BSSA-5 to identify S. aureus strains that are typeable with group 5 phages and exhibit all the phenotypic characteristics identified with the high-level β-lactamase-producing isolates of S. aureus described by McDougal and Thornsberry (14).

This study documents the prevalence of MRSA and BSSA-5 in wound infections and compares the prevalence associated with cefazolin prophylaxis to that associated with other prophylactic regimens. MRSA was found to comprise 11.6% of all S. aureaus wound isolates, a value comparable to the 11% prevalence of MRSA among nosocomial S. aureus isolates from U.S. hospitals during this period of time (18). MRSA isolates comprised a similar proportion of the S. aureus wound isolates from patients receiving cefazolin as they did from patients receiving other prophylactic regimens.

BSSA-5 isolates comprised an even larger proportion than MRSA, being recovered from 19.5% of S. aureus deep wound infections. We considered several explanations for this finding. BSSA-5 isolates might possess a special tropism for skin and soft tissues or have some other virulence attributes enabling them to cause wound infection. We do not have any evidence to confirm or refute this possibility. However, we found it remarkable that unlike MRSA, the BSSA-5 isolates accounted for twice the proportion of the wound isolates associated with cefazolin prophylaxis compared to the other prophylactic regimens. Furthermore, BSSA-5 isolates are unique among S. aureus in their ability to degrade cefazolin. Although cause and effect cannot be determined from these data, the strong association between BSSA-5 wound infection and cefazolin prophylaxis suggests that in vivo hydrolysis of cefazolin may enable BSSA-5 to survive the perioperative period, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of these infections. We previously have shown that type A β-lactamase-producing strains of S. aureus are associated with cefazolin-associated wound infections (10). This earlier observation was due, in part, to the common recovery of BSSA-5 isolates from wound infections in Nashville and Salt Lake City without evidence of a common epidemiological link among the infected patients.

There is an alternative hypothesis to explain the observed association between BSSA-5 and cefazolin prophylaxis that needs to be considered. The isolates evaluated in this study came from multiple hospitals which differed in the type of antibiotic prophylaxis used in surgery. It is possible that cefazolin prophylaxis was used more in hospitals where relatively resistant S. aureus strains were clustered. Although a randomized means of prophylactic regimen assignment would be required to completely rule out this possibility, the observation that the proportion of MRSA was virtually identical in S. aureus wound isolates from patients on cefazolin prophylaxis and in those from patients on other prophylactic regimens suggests that the likelihood of the wound being inoculated with resistant staphylococci was comparable for the two groups. Furthermore, surveillance cultures of specimens from the nares of cardiac surgery patients at the Nashville and Salt Lake City sites yielded 137 S. aureus isolates during this same period of time, only 12 (8.8%) of which were BSSA-5 (10a), suggesting that BSSA-5 was not especially common among patients undergoing surgery at these sites despite the strong association between BSSA-5 and wound infections failing cefazolin prophylaxis.

The observation that staphylococcal resistance may contribute to the pathogenesis of some wound infections has important clinical implications. Resistant subpopulations of staphylococci may account for a significant proportion of apparent prophylaxis failures; one-fourth of the S. aureus isolates recovered from infected wounds associated with cefazolin prophylaxis in this study were BSSA-5. Because of elimination half-life and cost considerations, it would appear reasonable that surgeons continue to employ cefazolin as the mainstay for perioperative prophylaxis in patients undergoing clean surgical procedures. However, based on our observations, the isolation of S. aureus from wound infections should be carefully monitored. A high or rising prevalence of BSSA-5 in association with cefazolin prophylaxis should prompt a reevaluation of strategies of perioperative prophylaxis with the consideration of using a more β-lactamase-stable agent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by PHS grant AI 32126 and a grant from Eli Lilly & Company, Indianapolis, Ind.

We thank Gary A. Hancock and J. Michael Miller of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for performing the phage typing assays. We thank Pat McGraw and Lyndell Weeks for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barg N, Chambers H, Kernodle D. Borderline susceptibility to antistaphylococcal penicillins is not conferred exclusively by the hyperproduction of β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1975–1979. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.10.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bignardi G E, Woodford N, Chapman A, Johnson A P, Speller D C. Detection of the mecA gene and phenotypic detection of resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates with borderline or low-level methicillin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:53–63. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapin-Robertson K, Edberg S E. Measurement of antibiotics in human body fluids: techniques and significance. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1991. pp. 295–366. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuny C, Claus H, Witte W. Discrimination of S. aureus strains by PCR for r-RNA gene spacer size polymorphism and comparison to SmaI macrorestriction patterns. Zentralbl Bakteriol Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1996;283:466–476. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frimodt-Møller N, Hartzen S H, Espersen F. In vitro activity of methicillin against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15:173–180. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerberding J L, Miick C, Liu H H, Chambers H F. Comparison of conventional susceptibility tests with direct detection of penicillin-binding protein 2a in borderline oxacillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2574–2579. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.12.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kernodle D S, Barg N L, Kaiser A B. Intrinsic methicillin resistance and phage complex 94/96 of Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:396–397. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kernodle D S, Stratton C W, McMurray L W, Chipley J R, McGraw P A. Differentiation of β-lactamase variants of Staphylococcus aureus by substrate hydrolysis profiles. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:103–108. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kernodle D S, Classen D C, Burke J P, Kaiser A B. Failure of cephalosporins to prevent Staphylococcus aureus surgical wound infections. JAMA. 1990;263:961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kernodle D S, McGraw P A, Stratton C W, Kaiser A B. Use of extracts versus whole-cell bacterial suspensions in the identification of Staphylococcus aureus β-lactamase variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:420–425. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Kernodle, D. S., D. C. Classen, C. W. Stratton, and A. B. Kaiser. Unpublished data.

- 11.Kloos W E, Jorgensen J H. Staphylococci. In: Lennette E H, Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 4th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1985. pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacey R W, Rosdahl V T. An unusual “penicillinase plasmid” of Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for its transfer under natural conditions. J Med Microbiol. 1974;7:1–9. doi: 10.1099/00222615-7-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massidda O, Montanari M P, Mingoia M, Varaldo P E. Cloning and expression of the penicillinase from a borderline methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strain in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDougal C K, Thornsberry C. The role of β-lactamase in staphylococcal resistance to penicillinase-resistant penicillins and cephalosporins. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:832–839. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.5.832-839.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMurray L W, Kernodle D S, Barg N L. Characterization of a widespread strain of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus associated with nosocomial infection. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:759–762. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standard M7A2. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novick R P. Analysis by transduction of mutations affecting penicillinase formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J Gen Microbiol. 1963;33:121–136. doi: 10.1099/00221287-33-1-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panlilio A L, Culver D H, Gaynes R P, Banerjee S, Henderson T S, Tolson J S, Martone W J. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in U.S. hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:582–586. doi: 10.1086/646432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richmond M H. Wild type variants of exopenicillinase from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J. 1965;94:584–593. doi: 10.1042/bj0940584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosdahl V T. Naturally occurring constitutive beta-lactamase of novel serotype in Staphylococcus aureus. J Gen Microbiol. 1973;77:229–231. doi: 10.1099/00221287-77-1-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosdahl V T, Rosendal K. Correlation of penicillinase production with phage type and susceptibility to antibiotics and heavy metals in Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 1983;16:391–399. doi: 10.1099/00222615-16-4-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaberg, D. R., D. H. Culver, and R. P. Gaynes. 1991. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infection. Am. J. Med. 91(Suppl. 3B):72S–75S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Siboni A H, Jensen K T, Rosdahl V T, Gaub J. Is methicillin better than cloxacillin in serious infections caused by strong penicillinase-producing staphylococci (phage-type 94/96)? Ugeskr Laeg. 1995;157:1862–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sierra-Madero J G, Knapp C, Karaffa C, Washington J A. Role of β-lactamase and different testing conditions in oxacillin-borderline-susceptible staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1754–1757. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith P B. Bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. In: Cohn J O, editor. The staphylococci. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1972. pp. 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomasz A, Drugeon H B, de Lencastre H M, Jabes D, McDougall L, Bille J. New mechanism for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: clinical isolates that lack the PBP 2a gene and contain normal penicillin-binding proteins with modified penicillin-binding capacity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1869–1874. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varaldo P E, Montanari M P, Biavasco F, Manso E, Ripa S, Santacroce F. Survey of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus for borderline susceptibility to antistaphylococcal penicillins. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:677–682. doi: 10.1007/BF02009379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zierdt C H, Hosein I K, Shively R, MacLowry J D. Phage pattern-specific oxacillin-resistant and borderline oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in U.S. hospitals: epidemiological significance. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:252–254. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.252-254.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zygmunt D J, Stratton C W, Kernodle D S. Characterization of four β-lactamases produced by Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:440–445. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]