Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide, yet improvements in survival have been modest despite advances in conventional therapies. The gut microbiota has emerged as a critical player in CRC pathogenesis and a promising therapeutic target to enhance clinical outcomes. Mounting evidence implicates specific microorganisms, notably Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Bacteroides fragilis, in tumor initiation and progression through DNA damage, inflammatory modulation, and immunosuppressive mechanisms. Clinical trials investigating microbiome modulators—including faecal microbiota transplantation, probiotics, prebiotics, and engineered biotherapeutics—highlight their potential to augment chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgical recovery, with encouraging preliminary efficacy in treatment-resistant CRC subtypes. Nonetheless, translating microbiome interventions into standardized clinical practice requires rigorous mechanistic validation, robust biomarker development, and careful management of safety concerns. Future research must focus on integrating high-resolution multi-omics, spatial microbiome mapping, artificial intelligence analytics, and innovative microbiome-targeted nanotechnologies to precisely reshape gut microbial communities, thereby ushering in a new era of precision oncology in colorectal cancer management.

Subject terms: Cellular microbiology, Clinical microbiology

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with over 1.9 million new cases and 900,000 deaths reported in 20221. The USA and China exhibit the highest incidence rates, followed by Japan, Russia, India, Germany, Brazil, the UK, Italy, and France2. Although CRC rates are higher in Western nations, they are rapidly increasing in developing countries. Early-onset CRC, diagnosed at age 50 or younger, has also emerged as a significant global concern3.

CRC is classified based on its spread: stage I or II when limited to the primary tumor, stage III when it involves regional lymph nodes, and stage IV when it metastasizes to distant sites. Treatment for stages I–III typically involves surgical resection, with stage III often requiring adjuvant chemotherapy. In metastatic CRC (stage IV), systemic therapies, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or their combinations, are commonly employed4. Despite advances like laparoscopic surgery, overall cure rates and long-term survival have improved only modestly over recent decades5.

Since 2004, adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer has generally included oxaliplatin and a fluoropyrimidine6. However, only 20% of patients benefit from this regimen, leaving 80% exposed to unnecessary toxicity7. Fluoropyrimidines are metabolized by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD); variants in the DPYD gene can lead to truncated proteins, prolonged drug exposure, and increased toxicity. Treatment-related mortality occurs in 0.1% of patients without DPYD variants but rises to 2.3% in those with such variants8. Additional side effects include oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy and chemotherapy-associated diarrhea6. Targeted therapies, which address specific molecular characteristics, have become vital, although drug resistance remains a significant challenge9.

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has transformed cancer therapy, with pembrolizumab approved as first-line treatment for the subset of CRC patients whose tumors exhibit microsatellite-instability-high (MSI-H) owing to their elevated mutational burden and neoantigen load10,11. However, approximately 85% of CRCs are proficient in mismatch repair (pMMR) and display microsatellite-instability-low (MSI-L) or microsatellite-stable (MSS) status. These pMMR-MSI-L/MSS “cold” tumors—characterized by low tumor mutation burden, scarce neoantigen presentation, minimal CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration, and activation of immunosuppressive pathways (e.g., WNT/β-catenin and TGF-β)—are largely resistant to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade12. Despite advances in surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, long-term survival gains have been modest, underscoring a pressing need for effective adjunctive therapies to improve CRC outcomes—especially in MSS CRC.

Given the limitations of current CRC therapies—including chemoresistance, immunotherapy resistance, radiotoxicity, and post-surgical complications—there is growing interest in the gut microbiota as a complementary therapeutic target. Rather than acting independently, microbial interventions may enhance the efficacy and reduce the toxicity of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. For instance, specific gut commensals like Roseburia intestinalis have been shown to sensitize CRC cells to radiotherapy by promoting radiation-induced autophagy13, while perioperative microbiota composition has been linked to postoperative recovery and long-term complications following CRC resection14. As mechanistic understanding deepens, integrating microbiota-based strategies into established treatment regimens offers a promising path to improved outcomes. This Review first explores the role of gut microbiota in CRC pathogenesis, followed by an examination of their therapeutic relevance across immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical management.

Role of gut microbial communities in CRC

Extending from the foundational roles of the gut microbiome in maintaining host metabolic, immune, and epithelial homeostasis, accumulating evidence implicates its disruption—termed gut dysbiosis—as a contributing factor in CRC15–17. Over the past decade, advances in metagenomic sequencing have enabled large-scale comparisons between CRC patients and healthy individuals, aimed at identifying microbial patterns that distinguish cancer-associated from normative gut communities. However, this endeavor is challenged by the intrinsic variability of the microbiota among healthy individuals, as well as by population-level heterogeneity driven by diet, lifestyle, geography, and antibiotic exposure18,19. Moreover, technical inconsistencies in sample collection, preservation, and DNA extraction further complicate cross-study comparisons20.

Despite these limitations, meta-analyses integrating data across diverse cohorts and methodologies have revealed consistent microbial alterations in CRC4. These include enrichment of oral-origin taxa—such as Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Parvimonas, and Peptostreptococcus—and depletion of beneficial butyrate-producing genera including Faecalibacterium and Roseburia21,22. Microbial profiles also appear to vary with tumor location and molecular subtype23, although reports of stage-specific taxa enrichment have shown poor reproducibility across studies24. Early evidence established associations between tumor microbiota and CRC molecular subtypes. CMS1 tumors—typically right-sided, MSI-H, and immunologically active—were shown to be enriched for oral pathogens including Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas micra, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, alongside upregulation of interferon-γ and TNF signaling25. Building on this, a recent large-scale analysis identified three oncomicrobial community subtypes (OCS1–3) with distinct taxonomic and clinicomolecular profiles. OCS1, dominated by Fusobacterium, corresponded to CMS1 tumors and was associated with CIMP-positivity, BRAF^V600E mutations, and MSI-related mutational signatures. OCS2 and OCS3 aligned with left-sided, CIN-type tumors and distinct microbial ecologies. Among patients with MSS disease, OCS1 and OCS3 subtypes were associated with worse prognosis. These data underscore the alignment between microbial composition and tumor phenotype, reflecting the biological heterogeneity of CRC23. Functionally, CRC-associated microbiota exhibit increased abundance of amino acid fermentation and polyamine biosynthesis pathways (e.g., arginine and ornithine metabolism), alongside reduced carbohydrate degradation capacity21. These shifts have been linked to altered production of microbial metabolites such as secondary bile acids and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have been implicated in modulating tumor-promoting inflammation, DNA damage, and epithelial proliferation. However, whether such dysbiotic shifts actively drive tumorigenesis or merely reflect adaptive responses to the neoplastic microenvironment remains unclear, underscoring the need for mechanistic studies in well-controlled experimental models to delineate causal microbial contributors from bystander taxa4.

In addition, the gut virome, mycobiome, and archaeome remain underexplored, though emerging evidence suggests roles in tumor immunity and microbial synergy26,27. To advance the field, it will be essential to move beyond descriptive and correlative studies toward mechanistic investigations that delineate the functional contributions of intratumoural microorganisms to tumor progression, metastasis, and immune regulation.

Role of specific microorganisms in CRC pathogenesis

The connection between specific microorganisms and CRC was first identified over 50 years ago with the discovery that Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus (Sgg) frequently colonizes patients with colorectal neoplasia28. Dysbiosis, increasingly defined as a weakening of host functions that regulate microbial growth by controlling resource availability, is frequently observed in CRC29,30. This dysbiotic state is often characterized by the overgrowth of specific bacterial taxa31. However, the influence of any individual microorganism must be understood within the broader ecological framework of the gut microbiome, where immunometabolic cues, circadian rhythms, epithelial integrity, and interbacterial interactions collectively shape microbial behavior and host response32. The evidence is particularly strong for three microorganisms—pks⁺ Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Bacteroides fragilis—which have been consistently linked to CRC through both mechanistic studies and correlative human data (Fig. 1)4. Although these bacteria are the most well-characterized, data implicating other taxa as potential CRC drivers are accumulating rapidly (Table 1)33. Nevertheless, despite extensive preclinical evidence, no microorganism or group of microorganisms has been definitively established as causative of human CRC, due to the absence of longitudinal studies demonstrating microbial presence preceding tumor onset or showing that microbial eradication reduces cancer risk34.

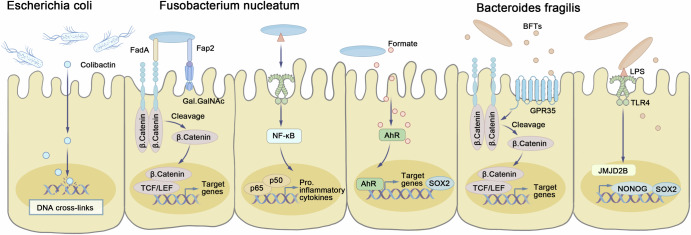

Fig. 1. Microbiota-associated mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer.

Escherichia coli produces colibactin, causing DNA interstrand cross-links and double-strand breaks with a unique mutational signature. Fusobacterium nucleatum’s Fap2 binds Gal-GalNAc, while FadA engages E-cadherin to activate Wnt–β-catenin and MYC, and its LPS triggers NF-κB–driven proliferation. Formate from F. nucleatum activates AhR, boosting invasiveness and SOX2-dependent stemness. Bacteroides fragilis secretes BFT to cleave E-cadherin and disrupt tight junctions, inducing MYC and proliferation; its LPS via TLR4 upregulates JMJD2B, SOX2, and NANOG to promote stemness. AhR aryl hydrocarbon receptor, BFT B. fragilis toxin, E-cadherin epithelial cadherin, FadA Fusobacterium adhesin A, Fap2 Fusobacterium autotransporter protein 2, Gal-GalNAc galactose-α1,3-N-acetylgalactosamine, JMJD2B jumonji domain-containing protein 2B, LPS lipopolysaccharide, MYC v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog, NF-κB nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, SOX2 SRY-box transcription factor 2, TLR4 Toll-like receptor 4.

Table 1.

Evidence for microorganisms as drivers of CRC: key bacteria, other bacteria, virome, and fungi

| Microorganism | Epidemiological evidence | Mouse model evidence | Type of mouse model | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Bacterial | Escherichia coli | Yes36,37,39,43 | Yes |

APCmin/+38 Zeb2IEC-Tg/+41 |

The oncogenic potential of pks+ E. coli critically depends on bacterial adhesion to host epithelial cells |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Yes44,46 | Yes |

APCmin/+45 AOM/DSS51 |

Fn generates abundant butyric acid, which inhibits histone deacetylase 3/8 in CD8+ T cells, inducing Tbx21 promoter H3K27 acetylation and expression. Furthermore, Fn-induced PD-L1 expression by activating STING signaling. | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Yes64 | Yes |

AOM60 BRAF V600E Lgr5 CreMin66 |

ETBF promoted CRC cell proliferation by downregulating miR-149-3p both in vitro and in vivo. | |

| Other Bacterial | Campylobacter Species | Yes67,69 | Limited | Germ-free ApcMin/+68 | Potentially relevant human species are C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli; evidence for the involvement of these species in human CRC is not available. |

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | Yes71 | Limited | APCmin/+74,75,77 | Its tryptophan metabolite IDA activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to induce ALDH1A3 expression and FSP1-mediated CoQ10 reduction, inhibiting ferroptosis via the AHR–ALDH1A3–FSP1–CoQ10 axis. | |

| Clostridioides difficile | Yes78,79 | Limited | APCmin/+80 | C. difficile promotes tumorigenesis by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, inducing ROS production, and eliciting a procarcinogenic mucosal immune response marked by IL-17 secretion and myeloid infiltration. | |

| Morganella morganii | Limited83 | Limited | AOM83 | Small molecules such as indolimines, produced by M. morganii, induce DNA damage and promote tumorigenesis in preclinical models. | |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus | Yes84 | Limited | AOM85 | Sgg may support CRC progression through niche adaptation mechanisms | |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Yes92 | Limited | APCmin/+87,89,90 | A. muciniphila facilitated enrichment of M1-like macrophages in an NLRP3-dependent manner in vivo and in vitro. | |

| virome | Yes25,26 | Limited | Apc+/1638N98 | Their direct involvement in tumorigenesis remains inconclusive. | |

| Fungi | Yes102–104 | Limited | Limited | Despite their lower abundance and high variability among individuals, they also exhibit distinct profiles in CRC patients. | |

“Limited” in the Mouse model evidence column indicates that the microorganism has been investigated in vivo, but the evidence remains preliminary, with limited mechanistic clarity, a lack of consistent tumorigenic outcomes, or insufficient validation across multiple CRC models.

AOM azoxymethane, DSS dextran sodium sulfate, APC^Min/+Apc^Min heterozygous mouse model, Zeb2^IEC-Tg/+ intestinal epithelial cell-specific Zeb2 transgenic mouse, BRAF^V600E Lgr5^CreMinBraf^V600E mutant mouse under Lgr5 promoter, Germ-free Apc^Min/+ germ-free Apc^Min mouse, ETBF enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, pks+E. coliEscherichia coli strains harboring the pks genomic island encoding colibactin, FnFusobacterium nucleatum, IDA indoleacrylic acid, AHR aryl hydrocarbon receptor, ALDH1A3 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3, FSP1 ferroptosis suppressor protein 1, CoQ10 coenzyme Q10, ROS reactive oxygen species, IL-17 interleukin-17, SggStreptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, Apc^+/1638NApc^+/1638N colorectal cancer mouse model.

Key bacterial players in CRC pathogenesis

Escherichia coli

E. coli strains harboring the pks genomic island—denoted pks⁺ E. coli—encode the biosynthetic machinery responsible for colibactin production35. Colibactin inflicts DNA double-strand breaks, engendering a spectrum of mutagenic lesions36,37. Accumulating evidence indicates that pks⁺ E. coli is overrepresented in CRC and that its colibactin contributes to intestinal tumorigenesis in murine models38. In particular, experiments in CRC-prone mice have shown that colonization with pks⁺ E. coli fosters an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) by diminishing CD3⁺ and CD8⁺ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, thereby impairing responses to anti-PD-1 therapy39. Furthermore, a European cohort study linked seropositivity to both pks⁺ E. coli and enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) with heightened CRC incidence, suggesting a cooperative role in neoplastic initiation40. Recent studies also highlight that the pathogenicity of enteropathogenic E. coli is influenced by its microbial context. In particular, mucin-degrading bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila facilitate E. coli encroachment into the epithelial niche by disrupting the mucus barrier, enabling access to host-derived nutrients and enhancing colonization under dietary restriction conditions41.

Building on this, pks⁺ E. coli has been shown to employ two lectin-like adhesins—FimH on type I pili and FmlH on F9 pili—to bind distinct glycan ligands (terminal D-mannose and T/Tn antigens, respectively), thereby orchestrating spatially resolved colonization of the tumor epithelium; deletion of either adhesin markedly attenuates CRC progression in murine models42. Concomitantly, colibactin-induced DNA damage triggers a senescence-associated secretory phenotype that selects for chemotherapy-resistant cancer stem cells, activates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, upregulates NANOG and OCT-3/4, and drives metabolic reprogramming with lipid droplet accumulation—further impeding CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration and fostering both chemoresistance and immune evasion43,44.

Fusobacterium nucleatum

Comprehensive metagenomic profiling of 1375 fecal samples from six cohorts confirmed enrichment of Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) across all colorectal tumor sites45. Neonatal inoculation of ApcMin/+ mice with the Fn strain Fn7-1 overcomes colonization resistance, triggers colonic Il17a upregulation prior to tumor onset, and accelerates intestinal tumorigenesis46. Within the colon, Fn invades deep gut crypts and, by single-cell transcriptomics, is shown to reprogram epithelial cells and activate LY6A⁺ revival stem cells that hyperproliferate into tumor-initiating cells47. At the molecular level, its FadA adhesin binds E-cadherin to trigger IκBα degradation and NF-κB signaling, while secreted ADP-heptose engages ALPK1 to induce CXCL8 release from epithelial cells48,49. In vivo, Fn or its metabolite formate increases tumor incidence and Th17 expansion, and recruits CX3CR1⁺PD-L1⁺ phagocytes to reshape the microenvironment50,51.

Recent studies have reported conflicting effects of Fn on immune checkpoint therapy outcomes in CRC. In preclinical models of PD-L1 blockade, Fn activated cGAS–STING signaling and increased IFN-γ⁺ CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration, thereby sensitizing tumors to immunotherapy52. Similarly, in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer (MSS CRC), intratumoral Fn enhanced anti-PD-1 efficacy via butyrate-mediated inhibition of HDAC3/8 in CD8⁺ T cells, leading to TBX21 upregulation and reduced T-cell exhaustion; strains lacking butyrate synthesis lost this benefit, and high intratumoral Fn predicted favorable responses10. Conversely, Fn colonization in the intestinal lumen has been linked to immunotherapy resistance: in metastatic CRC, elevated Fn abundance correlated with succinate production, which suppressed the cGAS–interferon-β axis and impeded CD8⁺ T-cell trafficking; antibiotic depletion using metronidazole reversed these effects and restored PD-1 sensitivity53.

In addition, in KRAS p.G12D-mutant CRC, tumor-colonizing Fn drives tumorigenesis via DHX15-dependent ERK/STAT3 signaling, whereas targeted enrichment of Parabacteroides distasonis can displace Fn and attenuate tumor progression, highlighting the therapeutic promise of microbiota modulation54. Fn also promotes chemoresistance by inhibiting pyroptosis and ferroptosis through BCL2–GSDME and β-catenin–GPX4 pathways55,56. Metformin reverses Fn-induced stemness and drug resistance via MYC/miR-361-5p suppression57. Moreover, the antimicrobial peptide Br-J-I disrupts FadA-mediated adhesion and enhances 5-FU efficacy58. These findings underscore the multifaceted roles of Fn in CRC progression, immune escape, and therapy resistance, and highlight its potential as a microbiota-targeted therapeutic axis.

Bacteroides fragilis

Bacteroides fragilis constitutes approximately 0.1–0.5% of the colonic microbiota, and a subset of strains harbors a pathogenicity island encoding the zinc-dependent metalloproteinase toxin B. fragilis toxin (BFT or fragilysin)59. ETBF is enriched in CRC and drives tumorigenesis by BFT-mediated cleavage of E-cadherin, which activates β-catenin and either NF-κB or Wnt signaling, increases epithelial permeability, and provokes mucosal immune responses, while also promoting cancer-stem-cell traits via TLR4 activation60,61. In vitro and in vivo, ETBF treatment of CRC cell lines (SW480, HCT-116) enhances proliferation, invasion, and migration by downregulating miR-139-3p—an effect reversed by miR-139-3p overexpression—and mechanistically ETBF upregulates HDAC3, which represses miR-139-3p to facilitate malignancy; HDAC3 knockdown or miR-139-3p restoration attenuates ETBF-driven CRC progression and reduces tumor growth in xenografts62. ETBF and BFT disrupt the intestinal barrier—impairing tight junction proteins (MUC2, Occludin, ZO-1), increasing permeability, reducing TEER and villus integrity—and activate the STAT3/ZEB2 axis to drive EMT and SW480 malignancy; these effects, as well as ETBF-exacerbated tumor load and barrier injury in AOM/DSS models, are mitigated by the STAT3 inhibitor Brevilin A or ZEB2 knockdown63. KRAS-mutant CRCs exhibit increased Bacteroides abundance, and mutant KRAS downregulates miR-3655—thereby upregulating SURF6, which inhibits IRF7 nuclear translocation and IFNβ transcription—to promote intratumoral ETBF colonization; targeting the miR-3655/SURF6/IRF7/IFNβ axis restores IFNβ-mediated ETBF clearance and offers a novel therapeutic avenue64. Human studies report higher ETBF prevalence in patients with colorectal neoplasia versus healthy individuals, though the specific stages of neoplasia associated with enrichment vary across cohorts65. Exosomes from ETBF-treated cells augment Th17 differentiation and CRC cell proliferation by downregulating miR-149-3p, indicating that the ETBF/miR-149-3p pathway could be a promising target for treating ETBF-associated intestinal inflammation and CRC66. Preliminary evidence suggests that ETBF may enhance anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by recruiting IFNγ-producing CD8⁺ T cells into tumors, but further investigation is required to define this mechanism and its therapeutic potential67.

Other bacterial taxa implicated in CRC

Beyond well-documented bacteria like E. coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Bacteroides fragilis, recent studies suggest that less-studied bacterial species may also influence CRC development. These findings highlight the intricate and dynamic role of the gut microbiota in CRC, paving the way for further exploration.

Campylobacter species

While primarily associated with gastroenteritis, Campylobacter jejuni has emerged as a potential contributor to intestinal tumorigenesis through the production of cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), a genotoxin capable of causing DNA double-strand breaks68. Experimental evidence in the ApcMin/+ mouse model demonstrates that CDT activity amplifies carcinogenesis69. Interestingly, Campylobacter concisus, an oral pathogen linked to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), has also been associated with CRC, suggesting broader involvement of the Campylobacter genus in gastrointestinal malignancies70.

Moreover, mechanistic studies reveal that C. jejuni–derived CDT promotes CRC metastasis by activating the JAK2–STAT3–MMP9 axis, enhancing matrix degradation and tumor cell invasiveness in liver and lung models, human colonic explants, and patient-derived tumoroids71. Ablation of cdtB or inhibition with purified CdtB protein abolishes this effect, underscoring intratumoural CDT’s central role in driving metastatic dissemination and its promise as a therapeutic target71.

Peptostreptococcus anaerobius

Peptostreptococcus anaerobius is enriched in CRC and has been implicated in tumorigenesis via diverse72, experimentally supported mechanisms: it engages TLR2 and TLR4 on colonic epithelial cells to increase ROS production, thereby stimulating cholesterol synthesis and cellular proliferation73; its tryptophan metabolite IDA activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to induce ALDH1A3 expression and FSP1-mediated CoQ10 reduction, inhibiting ferroptosis via the AHR–ALDH1A3–FSP1–CoQ10 axis74,75. Additionally, Pa remodels the TME by recruiting CXCR2⁺ MDSCs through integrin α2β1–NF-κB–CXCL1 signaling and by secreting lytC_22 to engage Slamf4 on intratumoral MDSCs, which upregulates ARG1 and iNOS, activates STAT3-dependent EMT, and contributes to chemoresistance in CRC76–78.

Clostridioides difficile

Traditionally known for its role in antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Clostridioides difficile has been identified as a potential contributor to CRC79. While one epidemiological analysis paradoxically found an inverse association between CDI and CRC incidence80, Sears et al. confirmed in mouse models that chronic colonization by toxigenic C. difficile drives colorectal tumorigenesis via TcdB-dependent activation of Wnt signaling, ROS generation, and pro-tumor mucosal immune responses—marked by myeloid cell activation and infiltration of IL-17–secreting innate lymphocyte81.

Beyond these pathways, recent findings indicate that TcdB can also activate Pyrin inflammasomes in intestinal epithelial cells, triggering ASC oligomer formation and robust inflammatory responses82. This activation disrupts tight junction proteins such as claudins and occludins, thereby impairing epithelial barrier integrity and promoting colitis83. These insights reveal that TcdB not only reprograms epithelial and immune signaling but also structurally compromises the mucosal barrier, collectively contributing to a tumor-favoring microenvironment.

Morganella morganii

Emerging evidence points to Morganella morganii, a gram-negative bacterium enriched in IBD and CRC patients, as a source of genotoxic compounds. Small molecules such as indolimines, produced by M. morganii, induce DNA damage and promote tumorigenesis in preclinical models84. These findings link microbial metabolite production to cancer progression, adding another layer of complexity to the gut microbiota–CRC axis.

Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus

Sgg is frequently enriched in CRC tissue and strongly associated with colorectal neoplasia in epidemiological studies85. Despite its correlation with CRC, the question remains whether Sgg is a driver or merely a passenger in the TME. Experimental models suggest that Sgg may support CRC progression through niche adaptation mechanisms, such as gallocin production, which inhibits competing enterococci86,87. However, more robust evidence is needed to establish its role in tumor initiation.

Akkermansia muciniphila

Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucin-degrading commensal, exerts multifaceted effects on CRC. Its abundance is typically reduced in CRC patients, and supplementation suppresses tumorigenesis by enriching M1-like macrophages through the TLR2–NF-κB–NLRP3 axis, a mechanism essential for its antitumour efficacy88. It also promotes CD8⁺ T-cell-mediated immunity via outer membrane vesicles containing Amuc_1434, which downregulate PD-L1, and through the acetyltransferase Amuc_2172, which induces H3K14 acetylation and upregulation of HSP70 in cancer cells89,90. Additionally, A. muciniphila impairs tryptophan–AhR–β-catenin signaling, contributing to tumor suppression in both chemical and genetic CRC models91. However, overcolonization can disrupt the mucosal barrier by degrading mucin and reducing tight junction proteins, thereby exacerbating CRC progression92. Furthermore, by thinning the mucus layer, A. muciniphila facilitates nutrient scavenging by pathogenic E. coli, highlighting a cooperative metabolic adaptation under dietary restriction41. Clinically, its depletion is associated with gut dysbiosis and reduced survival in CRC patients, underscoring its potential as both a therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker93.

Klebsiella species

Klebsiella species have been implicated in CRC through multifactorial mechanisms. Oral Klebsiella, enriched during periodontitis, can translocate to the gut and promote CRC via inflammasome activation and Th17 cell recruitment94. In murine models, Klebsiella aerogenes exacerbates colitis-associated tumorigenesis by disrupting the mucosal barrier and inducing inflammatory responses and microbial dysbiosis95. Clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from CRC patients often harbor polyketide synthase and siderophore genes, and enhance tumor cell proliferation in vitro96. Mendelian randomization further links Klebsiella abundance to CRC risk via immune modulation, particularly CD4⁺ T-cell pathways97. These findings highlight Klebsiella as a key oral–gut pathobiont in CRC development.

Fungal and viral contributions to CRC

While bacteria dominate the gut microbiota, non-bacterial components such as viruses and fungi also play a role in CRC pathogenesis98. Advances in sequencing technologies and metagenomic analyses have shed light on these understudied microbial kingdoms, revealing their potential contributions through trans-kingdom interactions and dysbiosis.

Virome alterations in CRC patients are marked by shifts in Siphoviridae and Myoviridae populations and an enrichment of Microviridae27. Virome dynamics—predominantly driven by bacteriophages—regulate gut bacterial communities and underpin microbiome stability. In H. pylori–infected Apc^+/1638N mice, an early-stage virome expansion of temperate phages—including those predicted to infect CRC-associated bacteria such as Enterococcus faecalis—was observed. Co-occurrence network analysis revealed strong viral–bacterial associations preceding tumor development, indicating that H. pylori–induced prophage activation and subsequent phage proliferation may promote colorectal carcinogenesis by reshaping the bacterial ecosystem99. Apart from their influence on bacterial ecosystems, Caudovirales-derived phages can breach the epithelial barrier, enter colonic cells, and trigger proinflammatory signaling that enhances tumor growth and invasiveness in CRC models100,101. Functionally, CRC patients’ viromes also display increased fatty acid biosynthesis pathways alongside depletion of viral metabolites such as L-methionine and acetate—compounds known to inhibit CRC cell proliferation and maintain mucosal homeostasis—indicating that virome shifts may directly impact tumor risk26,102.

Fungi, despite their lower abundance and high inter-individual variability, exhibit distinct alterations in CRC, including an increased Basidiomycota-to-Ascomycota ratio and enrichment of highly variable fungi103–105. They contribute to tumourigenesis through biofilm formation, secretion of mycotoxins (e.g., aflatoxins, candidalysin), induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-17, and disruption of epithelial barrier integrity—collectively fostering a pro-tumor, inflammation-prone microenvironment106. For example, Candida tropicalis activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid-derived suppressor cells to drive excessive IL-1β release, which in turn amplifies MDSC-mediated immunosuppression and promotes CRC progression107. Preliminary evidence also suggests that a compound ethanol extract of Ganoderma lucidum spores and Sanghuangporus vaninii may exert anti-CRC effects via the CYP24A1–VDR and TERT–Wnt signaling pathways108. Moreover, commensal bacteria limit fungal overgrowth by producing antifungal toxins and metabolites and by engaging host immune pathways, while fungal–bacterial interactions can themselves elicit unique immune responses109.

Role of microbiome modulators in CRC clinical trials

Current targeted therapies and immunotherapies exhibit limited efficacy due to the immunosuppressive TME and gut dysbiosis-driven drug resistance. Microbiome modulators (MMs), encompassing fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), probiotics/prebiotics/synbiotics therapy, live biotherapeutic product (LBP), have emerged as paradigm-shifting adjuvants110. These agents restore gut eubiosis, enhance antitumor immunity via multiple mechanisms of action, demonstrating unprecedented therapeutic potentials in pan-cancers111. Herein, to unravel critical gaps in CRC treatment, this study delineates the evolving MM clinical trial landscape while bridging emerging preclinical insights to optimize therapeutic research and development.

We conducted a comprehensive search of the Trialtrove database (https://clinicalintelligence.citeline.com), an authoritative platform that integrates clinical trial data from dozens of countries and regions worldwide, including ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and national registries across North America, Europe, and Asia. As of June 30, 2025, we applied the retrieval strategy: (Disease is Oncology: Colorectal) AND (Mechanism of Action is Microbiome modulator) to identify relevant studies. Analytical parameters included trial phase and status distribution, MM types, sponsor classifications, disease stage and line of therapy, primary/secondary endpoints, and combination strategies. Two independent investigators systematically reviewed and verified all retrieved records and analytical results (Fig. 2), including the extraction of unstructured information, the resolution of data gaps, and the minimization of classification bias, to ensure methodological rigor and strict quality control. Any residual limitations following these procedures do not affect the overall interpretation or observed trends of this study.

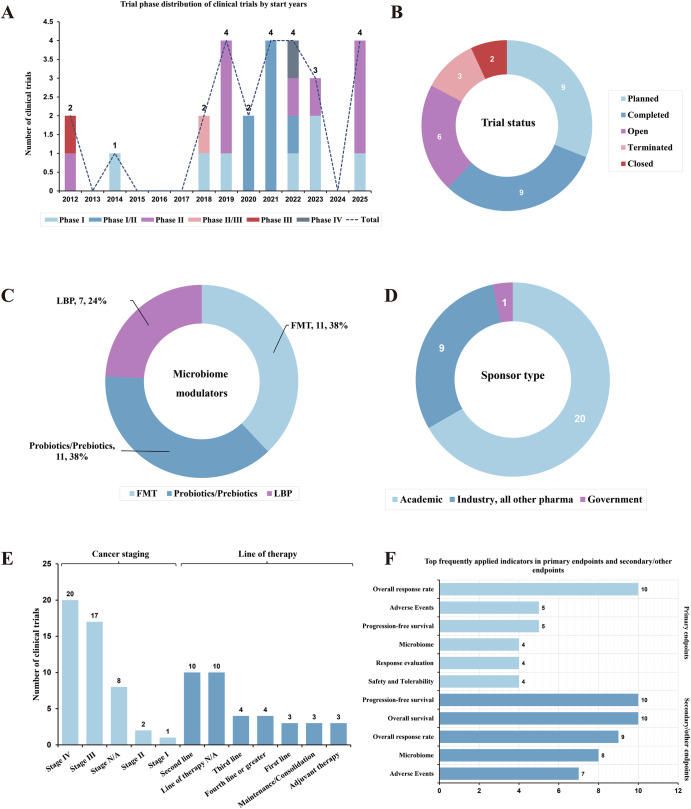

Fig. 2. The clinical investigation panorama of microbiome modulators in CRC treatment.

A Trial phase distribution of clinical trials by start years. B Trial status distribution of clinical trials. C Microbiome modulator type distribution of clinical trials. D Sponsor type distribution of clinical trials. E Cancer staging and line of therapy distribution of clinical trials. F Endpoint distribution of clinical trials.

To date, 29 trials were conducted to evaluate MMs in CRC, spanning FMT (n = 11), probiotics/prebiotics therapy (n = 11), and LBP (n = 7) (Table S1/Fig. 2C). Phase II trials dominated in pipelines (n = 9), followed by Phase I (n = 7) and Phase I/II (n = 7) (Fig. 2A). Most of the trials are being planned, concurrently with a considerable proportion of completed trials (Fig. 2B). Academic sponsors dominated in this field with industry-initiated trials followed (Fig. 2D). Later-line therapies of advanced CRC patients are the predominant indication selections for this fresh therapeutic (Fig. 2E). And the primary endpoints focused mainly on the overall response rate (ORR) of this therapeutic strategy in CRC patients currently, with some novel microbiome indicators innovatively applied (Fig. 2F). In addition, combination with CRC standard of care (SOC) regimens represent the mainstream clinical trend (Table S1). More importantly, some trials disclosed the positive outcomes, implying the promising therapeutic potentials of diverse microbiome modulation strategies in CRC treatment.

While the clinical pipeline for MMs in CRC remains predominantly early-phase, selected studies have begun to demonstrate biologically meaningful signals that extend beyond descriptive endpoints. In the RENMIN-215 trial, FMT from healthy donors was combined with the anti-PD-1 antibody tislelizumab and the VEGFR inhibitor fruquintinib in patients with refractory, MSS metastatic CRC. The study reported an objective response rate of 20% and a disease control rate (DCR) of 95%, with a median progression-free survival (mPFS) of 9.6 months and a median overall survival (mOS) of 13.7 months—figures rarely observed in this resistant population112. Notably, responders exhibited increased microbial diversity and sustained microbiota engraftment, implying that gut ecosystem restoration may overcome immunotherapy resistance through modulation of the TME113.

More broadly, meta-analyses across solid tumors indicate that combining FMT with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) improves objective response rates compared to immunotherapy alone, with pooled ORRs of 43.1% versus 36.9% in early-phase trials114. Mechanistic studies have implicated key commensals—such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Bacteroides uniformis—in enhancing antitumour immune activation, through increased antigen presentation, interferon-γ production, and modulation of regulatory T cells115.

Despite these promising findings, most MM trials to date have enrolled patients with advanced, heavily pre-treated disease, a context in which microbial dysbiosis and chronic antigenic stimulation may drive CD8⁺ T-cell exhaustion, thereby attenuating the efficacy of microbiome-based interventions116. Furthermore, the absence of integrated microbial, metabolic, or immunologic biomarkers in many protocols restricts mechanistic interpretation and patient stratification. Addressing these gaps will require trial designs that incorporate microbiome profiling, functional readouts (e.g., SCFA production), and immune correlatives to identify predictive signatures and optimize rational combinations.

Collectively, this analysis delineates the burgeoning clinical investigation landscape of MMs in CRC, with 29 trials evaluating FMT, probiotics/prebiotics, and LBPs. These findings underscore the translational promise of microbiome modulation as a paradigm-shifting adjuvant in CRC. Future efforts should prioritize optimizing optimal MM combination regimens, validating microbiome-based biomarkers, and expanding trials to broader patient cohorts to accelerate clinical translation.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. The Trialtrove database, curated by a team of therapeutically focused expert analysts, is widely recognized as a comprehensive and authoritative source of global clinical trial intelligence and has contributed to numerous peer-reviewed publications117–119. Nevertheless, delays in data updates and occasional classification inconsistencies may affect the completeness of trial capture. To address this, two additional investigators were assigned to manually verify key records through timely tracking of multiple data sources, including official clinical trial registries across different countries and regions, conference abstracts, and published literature. These measures were intended to improve data coverage within the constraints of available resources.

Role of gut microbiota in CRC treatment

Therapeutic implications for chemotherapy

Increasing research suggests that gut microbiota can influence the anticancer effects of certain chemotherapeutic agents, such as 5-fluorouracil120, cyclophosphamide121, and oxaliplatin122, through various mechanisms, including microbial translocation, immunomodulation, metabolism, enzymatic degradation, and reduced ecological diversity123. Also, Gut microbial metabolites, particularly butyrate, may enhance the effectiveness of oxaliplatin by regulating the function of CD8+ T cells within the TME124. In vitro studies indicate that Lactobacillus species can either boost the activity of or counteract resistance to 5-FU and irinotecan in CRC by secreting metabolites like butyrate125, gamma-aminobutyric acid126, and extracellular vesicles127. The DM#1 mixture, which includes Bifidobacterium breve DM8310, L. acidophilus DM8302, Lactobacillus casei DM8121, and S. thermophilus DM8309, has been shown to restore intestinal integrity and reduce the activation of proinflammatory cytokines following 5-FU treatment128. Similar beneficial effects have been observed when Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus paracasei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Bifidobacterium lactis are used as probiotics in conjunction with 5-FU129. Furthermore, L. rhamnosus GG was associated with a reduction in the severity of diarrhea in a cohort of 150 crc patients undergoing 5-FU treatment130. A study also suggested that Bifidobacterium infantis might mitigate chemotherapy-induced toxicity (from 5-FU and oxaliplatin) by suppressing Th1 and Th17 activation while boosting the activity of cytotoxic regulatory T cells (CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+) in Sprague-Dawley rats131. Recent evidence indicates that tumor-colonizing Bacteroides fragilis mediates resistance to 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin via SusD/RagB-dependent activation of Notch1 signaling, culminating in EMT and stemness acquisition132. Lang et al. developed a Capecitabine-loaded nanoparticle using a prebiotic xylan-stearic acid conjugate (SCXN). This SCXN nanoparticle significantly enhances antitumor immunity and increases the tumor inhibition rate from 5.29% to 71.78% compared to free Capecitabine133.

In addition to boosting antitumor effects, the gut microbiota also impacts the toxicity associated with chemotherapy. A frequent complication for cancer patients undergoing treatment is intestinal mucositis and diarrhea134,135. The active metabolite of irinotecan, SN-38, is detoxified in the liver through glucuronidation and then excreted into the gut via bile136. However, gut bacteria can reactivate SN-38 by producing β-glucuronidase, leading to intestinal damage and severe diarrhea137. Using a selective inhibitor to block this reactivation could prevent the associated toxicity in mice, offering a strategy to alter microbial activity and mitigate the adverse side effects of chemotherapy138.

Therapeutic implications for immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has emerged as a cornerstone in cancer treatment, demonstrating effectiveness across various types of cancer139. ICIs function by lifting the inhibitory signals on T-cell activation, enabling tumor-reactive T cells to generate a robust antitumor response140. Despite this, ICIs are generally ineffective in CRC, with the exception of a small percentage (~5%) of patients who have MMR-deficient or MSI-H tumors141,142. The gut microbiota is essential for a successful immune response during immunotherapy and can influence the efficacy of ICIs targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways143–145. Certain bacteria, including Akkermansia muciniphila143, B. fragilis145, Bifidobacterium spp.146, Eubacterium limosum147, Faecalibacterium spp.148, and Alistipes shahii122, have been linked to improved outcomes with immunotherapy. However, as CTLA-4 and PD-1 are also highly expressed on tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells (Tregs), their blockade may paradoxically disrupt immune regulation, potentially exacerbating autoimmunity or undermining therapeutic efficacy149. Considering the gut microbiota’s role in modulating responses to ICIs, this area offers promising translational opportunities for advancing CRC treatment (Fig. 3).

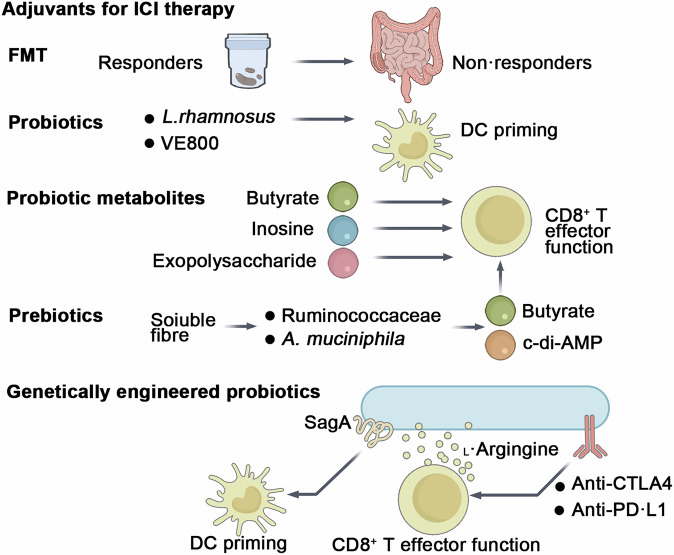

Fig. 3. Current strategies leveraging the gut microbiota to enhance responsiveness to ICIs in CRC.

These strategies include FMT and emerging approaches such as probiotics, prebiotics, probiotic metabolites, and genetically engineered probiotics, all of which hold great potential in improving patient outcomes.

Interestingly, pathobionts that promote CRC may have mixed effects on ICIs. For instance, while F. nucleatum is known to drive tumor growth and chemoresistance, it can also boost the effectiveness of anti-PD-L1 antibodies and extend survival in mouse models150. It activates STING–NF-κB signaling and enhances PD-L1 expression, yet paradoxically increases CD8+ T-cell activation when PD-L1 is blocked150. Similarly, ETBF in multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mice induces serrated-like tumors and increases sensitivity to anti-PD-L1 antibodies151. Thus, pathogenic bacteria can have conflicting effects on ICI therapy.

Prebiotics

Higher dietary fiber intake is linked to better responses to ICIs and fewer immune-related adverse events in cancer patients from diverse global cohorts152. Additionally, prebiotics and soluble fibers like inulin153, pectin154, polyphenols155, and polysaccharides156 have been found to boost the effectiveness of anti-PD-1 antibodies in several mouse models. Mechanistically, these substances promote the enrichment of specific bacterial genera, such as those in the Ruminococcaceae family, individual bacteria like Akkermansia muciniphila, and their metabolites, including SCFAs and cyclic diadenosine monophosphate (cyclic di-AMP)157. SCFAs enhance the function of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells153, while cyclic di-AMP triggers STING-dependent type I interferon production, leading to the activation of innate immune responses (including monocytes, NK cells, and dendritic cells) and improved ICI efficacy158. However, under fiber deprivation, mucin-degrading bacteria (Akkermansia muciniphila) may degrade host-derived mucins, compromising the mucus barrier and increasing colitis susceptibility. Thus, maintaining adequate dietary fiber intake is crucial to leverage beneficial microbial activities while avoiding potential detrimental effects associated with excessive mucin degradation159,160. In a transgenic mouse model of CRC, a combination of inulin gel and α-PD-1 therapy inhibited the growth of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-accelerated colon tumors in CDX2-Cre NLS-APCfl/fl mice153. Since prebiotics depend on the presence of beneficial taxa already existing in the host’s microbiota, synbiotics—which involve the combined administration of both prebiotics and probiotics—may offer greater effectiveness than using either alone161.

Probiotics and their products

Certain gut bacteria, such as A. muciniphila143, B. fragilis145, Bifidobacterium146, L. rhamnosus GG162, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei163, and various probiotic mixtures164, have been shown to enhance the efficacy of ICIs in mouse models. Recent studies have explored the effects of CBM588, which contains C. butyricum, on metastatic renal cell carcinoma treatments. One Phase I trial found that adding CBM588 to nivolumab and ipilimumab improved response rates (58% vs. 20%, P = 0.06), though not significantly165. Another trial showed a significant increase in response rates when CBM588 was combined with cabozantinib and nivolumab (74% vs. 20%, P = 0.01)166.

The optimal dose of probiotics is crucial for treatment efficacy, as an excessive presence of a beneficial bacterial species could disrupt the gut microbiota’s balance and diversity, potentially leading to worse outcomes. A study on NSCLC patients receiving ICB therapy found that while the presence of Akkermansia muciniphila correlated with improved responses, patients with a relative abundance of A. muciniphila over 5% had worse outcomes than those without it167. Also, selected reports have described context-specific interventions that failed to confer benefit or even exacerbated disease. In a cohort of 158 melanoma patients receiving ICB, self-reported use of commercially available probiotics was associated with a trend toward reduced response rates and shorter progression-free survival, although differences did not reach statistical significance. Preclinical validation in mice supported these findings, showing that probiotic supplementation impaired anti-PD-1 efficacy by reducing intratumoral interferon-γ⁺ cytotoxic T-cell accumulation168. Separately, in a murine model of colitis-associated CRC (AOM/Il10⁻/⁻), interventional treatment with the VSL#3 probiotic cocktail significantly increased tumor incidence, multiplicity, and histologic dysplasia, accompanied by loss of protective Clostridial taxa in the mucosa-associated microbiota169. These findings underscore the need for cautious, evidence-based selection of probiotic regimens in oncological settings, particularly when inflammation or dysbiosis is present. Current research is exploring the use of well-balanced microbial consortia, such as VE800, a probiotic cocktail of 11 strains, in combination with nivolumab in a Phase I/II trial for MSS CRC164. Additionally, a 30-bacteria consortium (MET4) was found to be safe and capable of modifying the gut microbiota and serum metabolome in ICB-naive patients, reinforcing the potential benefits of microbial consortia170. However, a study demonstrated that a mix of four Clostridiales strains (CC4) could prevent and treat CRC in mice, with the effect reliant on CD8+ T-cell activation. Interestingly, single applications of Roseburia intestinalis or Anaerostipes caccae were even more effective than the CC4 mix171. These findings suggest that while consortia may be beneficial, certain individual strains could provide superior therapeutic effects.

Several probiotic-derived therapeutics, informed by an understanding of their active components, are currently being evaluated as adjuvants to ICIs. These include bacterial lysates172, extracellular vesicles173, and more defined components such as exopolysaccharides174, muropeptides175, and metabolites124,176,177. These components have the potential to either fully or partially mimic the effects of live probiotics in enhancing the efficacy of ICIs.

Genetically engineered probiotics

Probiotics engineered with improved functionality could serve as a safe and efficient method for delivering adjuvant therapy. Investigators engineered a Lactobacillus lactis strain expressing either wild-type, catalytically inactive (C443A), or secretion-deficient (ΔSS) SagA, with the wild-type and C443A mutants showing higher signals in the secreted fraction; animals supplemented with L. lactis expressing wild-type SagA demonstrated tumor growth inhibition comparable to that of E. faecium-treated animals, effectively augmenting the activity of anti-PD-L1 antibodies to a similar extent as natural SagA-expressing Enterococcus strains in MC38 CRC allograft mice175. Genetically engineered bacteria could be employed as vehicles to support the metabolism of intratumoral T cells. In an immunocompetent mouse model of CRC (MC38), researchers developed a probiotic strain of E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) that converts tumor-derived ammonia into L-arginine178,179. This L-arginine plays a critical role in enhancing the metabolic fitness and survival of T cells, which are vital for effective antitumor responses180 (Fig. 4).

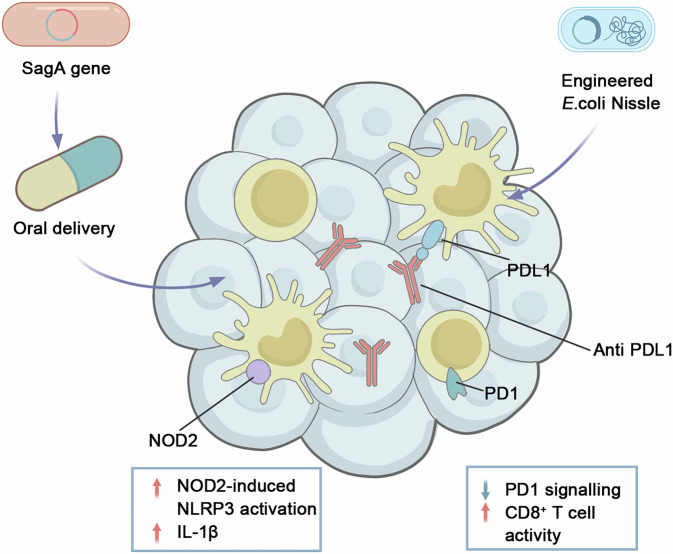

Fig. 4. Genetically engineered probiotics for tumor-targeted immunotherapy.

Orally delivered Lactobacillus plantarum expressing SagA generates muropeptides that engage macrophage NOD2, activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β release. Concurrently, tumor-colonizing Escherichia coli Nissle secretes anti-PD-L1 nanobodies in situ, blocking PD-1/PD-L1 interactions and restoring CD8⁺ T-cell activity. NOD2 nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2, SagA secreted antigen A.

To evaluate the versatility of probiotic systems in treating immunologically “cold” cancers, researchers have developed engineered probiotics designed for targeted therapy delivery. This approach involves engineering probiotic bacteria to produce and release nanobodies targeting PD-L1 and CTLA-4 directly within tumors, utilizing a controlled lysing release mechanism. In a mouse model of MSS CRC, combining this system with a probiotic-produced cytokine, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, led to improved antitumor effects and increased survival181. These studies demonstrate the potential of genetically engineered probiotics as adaptable tools to enhance the effectiveness of ICIs.

Fecal microbiota transplantation

FMT is a clinical approach to modulating the microbiome, which has received FDA approval for treating recurrent C. difficile infections182. FMT has also been explored in combination with ICIs in clinical trials, based on evidence that administering FMT to germ-free animals can replicate the ICI responses observed in human donors183,184. However, one study found that mice receiving FMT from patients with IBD experienced a significant reduction in colonic TH1 cells compared to those receiving FMT from healthy donors, and exhibited resistance to treatment185, suggesting that a healthy microbiome is crucial for ICI efficacy.

Initial clinical studies have shown promising results, such as overcoming resistance to anti-PD-1 antibodies in some patients with ICI-refractory metastatic melanoma through FMT from anti-PD-1-responsive donors186,187. Moreover, a multicenter phase I trial evaluated the combination of FMT from cancer-free donors with nivolumab or pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated advanced-stage melanoma188.

In a study by Huang, the combination of FMT and PD-1 inhibitors led to better survival outcomes and tumor control compared to either treatment alone in CRC tumor-bearing mice. The study highlighted that FMT-increased Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Bacteroides fragilis, along with FMT-decreased Bacteroides ovatus, contributed to the enhanced efficacy of ICIs in CRC184. In a phase II trial, MSS mCRC patients received FMT plus tislelizumab and fruquintinib as a third-line or beyond treatment, resulting in a mPFS of 9.6 months and a median overall survival (mOS) of 13.7 months, with an ORR of 20% and a DCR of 95%, and no treatment-related deaths112. Another clinical trial suggests that FMT with beneficial microbiota can help overcome resistance to anti-PD-1 inhibitors in advanced solid cancers, particularly gastrointestinal cancers113. Additional trials using similar approaches in CRC patients are ongoing (NCT04729322 and NCT04130763).

However, FMT has notable limitations, including safety concerns and challenges related to the generalizability and standardization of microbiota profiles needed for efficacy, both in donors and recipients, which makes it less suitable for widespread use. Since FMT involves transplanting the entire viable gut microbiota from a donor, it carries inherent risks of transmitting known and unknown pathogens. Reported complications include norovirus enteritis, cytomegalovirus reactivation, fungal and parasitic infections, and even the potential horizontal transfer of disease-associated traits such as obesity or metabolic dysfunctions189,190. In 2019, it was reported that two patients developed bacteremia with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli after receiving FMT from the same donor, resulting in one fatality191. This incident prompted the US Food and Drug Administration to issue a safety warning about the infection risks associated with FMT. Furthermore, a recent retrospective cohort study found that 9% of tested donor feces contained multidrug-resistant organisms at some point, highlighting another significant safety concern192.

Therapeutic implications for radiotherapy

Radiotherapy (RT) is a widely used antitumor treatment, with over 50% of newly diagnosed cancer patients with solid tumors undergoing RT at some stage of their treatment193. The intestine, however, is highly sensitive to radiation due to its rapid epithelial turnover194. Studies in mouse models, including those focused on segmental small bowel radiation195 and graft-versus-host disease196,197, have demonstrated significant shifts in gut microbiota following RT. There is a bidirectional interaction between intestinal microbiota and radiotherapy. On one side, ionizing radiation alters the composition and function of the gut microbiome, reducing microbial diversity and richness, increasing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria such as Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, and decreasing beneficial species like Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium198. Prophylactic administration of B. infantis with its specific antibody has been shown to enhance radiosensitization and suppress tumor growth in a murine lung cancer model199, while absolute quantification via 16S rRNA qPCR demonstrates an approximately 90% reduction in total bacterial load after (chemo)radiotherapy, indicating that relative increases in pathobionts often reflect loss of dominant commensals rather than their true overgrowth200. On the other side, the microbiota influences the clinical efficacy of RT by enhancing treatment outcomes and mitigating radiotoxicity.

Improving the efficacy of radiotherapy

Research has shown that oral vancomycin enhances both the direct and abscopal antitumor effects of hypofractionated RT in preclinical models of melanoma and lung/cervical tumors201. Other studies have revealed that commensal bacteria are essential for effective antitumor immune responses, while commensal fungi regulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment after RT. Targeting these fungi has been shown to improve RT outcomes202. FMT has been found to increase levels of Roseburia intestinalis in the gastrointestinal tract, with this gut commensal bacterium promoting radiation-induced autophagy and enhancing CRC cell death via the butyrate/OR51E1/RALB axis. This mechanism offers a promising radiosensitizer for CRC in preclinical settings203. Additionally, ETBF, a bacterial strain enriched in CRC patients, produces Bacteroides fragilis toxin (BFT) and IL-17, which synergistically activate the STAT3 signaling pathway in immune cells, potentially promoting cancer growth204. Studies suggest that ETBF may also enhance radioresistance in CRC by generating BFT, potentially activating the JAK2/STAT3/CCND2 axis, a known mediator of radioresistance205.

Reducing radiotoxicity

Several strategies have been identified to reduce the harmful side effects of RT. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that the probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 (SsK12) significantly reduced the incidence, onset, and duration of severe oral mucositis in RT patients, with a favorable safety profile206. Additionally, experimental studies have shown that FMT mitigates acute radiation syndrome (ARS), improving peripheral white blood cell counts and preserving gastrointestinal function and intestinal epithelial integrity in irradiated mice207. Further research found that FMT increases levels of indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) in irradiated mice, a compound that alleviates gastrointestinal toxicity after total abdominal irradiation without accelerating tumor growth208.

Therapeutic implications for surgical resection

Compelling experimental data from rodent studies highlight the vital role of gut microbes in intestinal mucosal vascularization and wound healing209. Specific components of the microbiota, especially butyrate-producing bacteria, are instrumental in epithelial repair210. Additionally, research has shown that Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron promotes angiogenesis by effectively doubling the capillary network in the small intestine through the activation of Paneth cells211.

The dynamics of bacterial competition and cooperation within microbial communities can either facilitate or hinder wound healing. For instance, Lactobacillus fermentum RC-14 has been found to inhibit infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus in a rat model of surgical implants212. Conversely, the collaboration among siderophore-producing bacteria, like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can increase virulence by enabling the sharing of iron-scavenging compounds with other bacteria213.

In a landmark study in 1997, Schardey et al. suggested a potential link between P. aeruginosa and anastomotic leaks, leading to the first randomized double-blind trial that confirmed the involvement of microbes in human anastomotic complications214. Subsequent research found that a novel virulence-suppressing compound, PEG/Pi (high-molecular-weight PEG), prevented P. aeruginosa from adopting a tissue-destructive phenotype, thus mitigating anastomotic leaks in rat models215. Research by Shogan et al. examined the shifts in microbiota at anastomotic sites in a rodent model using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Notably, their study avoided the use of antibiotics and bowel preparation, revealing significant changes in tissue-associated microbiota at these sites, while the luminal microbiota (stool) remained relatively stable216.

Comparative analyses of gut microbiota revealed that post-surgery CRC patients (A1) exhibit significant differences in microbial diversity compared to pre-surgery patients (A0) and healthy individuals (H). Specifically, both Shannon and Simpson diversity indices were notably lower in A1 (P < 0.05), underscoring the gut microbiota’s role in post-surgical outcomes217. Additionally, a recent study identified that an increased abundance of specific microbiota clusters, including pathobiont genera such as Fusobacterium, Granulicatella, and Gemella, correlates with better outcomes following primary resection, challenging conventional views on the gut microbiota’s role in CRC prognosis218.

In a clinical investigation, Komen et al. developed a rapid screening method for early detection of colorectal anastomotic leaks based on the detection of E. coli and Enterococcus faecalis in drained fluid using RT-PCR. Their results indicate that higher levels of E. faecalis may serve as a reliable indicator for early detection, while negative results strongly suggest the absence of anastomotic leaks219. Reviews on the use of probiotics in the perioperative care of CRC patients indicate that probiotics can reduce bacterial translocation, enhance intestinal mucosal integrity, and promote a favorable balance between beneficial and harmful microorganisms220. Furthermore, both probiotics and synbiotics are emerging as effective strategies to prevent postoperative complications in CRC surgery221.

Conclusion and outlooks

Unlike the relatively static human genome, the microbiome demonstrates remarkable plasticity, continually evolving in response to environmental, dietary, and lifestyle factors222. While the host genome is largely inherited from parental DNA, the microbiome is highly personalized, characterized by significant variability across individuals and over time223,224. Understanding the drivers of this complexity offers a unique opportunity to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies, paving the way for more precise and personalized healthcare solutions225.

In CRC, metagenomic sequencing is increasingly employed to characterize tumor-associated microbial communities45,226; However, notable discrepancies across studies limit their clinical application, often arising from technical differences (such as sample processing and sequencing methods) and confounding factors like geography, diet, gender, and sampling time227,228. To address these issues, the Strengthening the Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies guideline was introduced, providing a 17-item checklist designed to promote consistency and transparency in microbiome research229. Moreover, rigorous a priori power and sample-size calculations—accounting for microbiome data’s compositionality, sparsity, and high dimensionality—are essential to ensure valid hypothesis testing and robust, generalizable conclusions230. Complementing these efforts, integrative multi-omics frameworks—combining metagenomics with metabolomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics at bulk and single-cell resolution in patient-derived tissues and experimental models—are being deployed to unravel the complexity of host–microbe crosstalk231–233. Recent developments in spatial meta-omics profiling—employing targeted nucleic-acid hybridization probes to resolve microbial taxa distributions within TMEs—have begun to delineate the architecture of the intratumoural microbiome and its modulatory effects on adjacent cellular phenotypes234,235. However, these approaches remain unable to integrate microbial spatial mapping with concurrent in situ functional assays (eg, microbial toxin or cytokine expression). Addressing the constraints imposed by low microbial biomass and rapid RNA degradation will be pivotal for true interactome reconstruction and high-resolution spatial community profiling222.

Moreover, to address limitations in low-biomass clinical specimens, a tailored metatranscriptomics workflow has been developed that integrates optimized taxonomic profiling (Kraken 2/Bracken) with functional annotation (HUMAnN 3), enabling accurate detection of microbial species and their expressed pathways even in gastric tissues with a high host RNA background236. Complementing this, the advent of long-read sequencing platforms has significantly enhanced metagenome-assembled genome completeness, strain-level discrimination, and variant calling, overcoming the assembly and profiling biases inherent to short-read approaches237.

The increasing depth and scale of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic datasets can inadvertently amplify artefacts—as exemplified by Parida et al.’s report of extremophilic taxa in breast tumors—prompting rigorous revisions to contamination controls, batch-effect corrections, and validation pipelines238,239. In response, machine-learning and artificial-intelligence pipelines have been refined with stricter cross-validation, larger hold-out cohorts, and tailored feature-engineering to extract true signals from complex microbiome data240. Integrating explainable AI—such as Random Forests coupled with SHAP—yielded ~0.73 precision and a ~0.67 precision-recall AUC in CRC classification, while highlighting Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Parvimonas as the most predictive taxa241.

However, many AI models—despite reported superiority—often show only moderate or unstable predictive power in cancer studies, largely due to overfitting on small cohorts, poor-quality or limited microbiome datasets, and inadequate validation242,243. To enhance generalizability and accuracy in microbiome-based CRC applications, strategies such as multimodal data integration (clinical, microbial, and longitudinal)244, leveraging microbiome signatures for immunotherapy response prediction, and incorporating high-resolution single-cell and spatial multi-omics have been proposed245,246, underscoring AI’s critical role in deciphering complex gut microbial ecosystems for precision oncology.

Nanotechnology has revolutionized CRC therapy by enabling nanoscale drug delivery systems that overcome poor solubility and stability in the gastrointestinal tract, while enhancing tumor accumulation and minimizing systemic exposure247,248. These platforms also offer precise modulation of the gut microbiota: bacteria-targeting ligands guide drug-loaded carriers to tumors, and self-thermophoretic nanoparticles cloaked in bacterial membranes achieve deeper mucus penetration and reduced microbial interception, yielding near-complete tumor regression in orthotopic CRC models247,249.

Building on these advances, bioengineered probiotics and prebiotic–nanoparticle composites have been developed to selectively colonize CRC lesions and reshape the microbial ecosystem133. Tumor-targeted E. coli Nissle and Pediococcus pentosaceus expressing therapeutic proteins inhibit CRC cell growth and regress adenomas250,251, while prebiotic-encapsulated spores and xylan-stearic acid nanoparticles promote SCFA production, augment CD8⁺ T-cell activity, and boost antitumour efficacy from 5% to over 70% in vivo133,252. Despite these promising strategies, key challenges—intestinal infiltration, probiotic engraftment, intratumoural targeting, and immune regulation—must be addressed to realize precision microbiota editing in CRC management.

In the future, rigorous study designs, standardized multi-omics frameworks, and the innovative integration of spatial omics, artificial intelligence, and microbiome-targeted nanotechnologies will be essential to unravel microbial mechanisms underpinning CRC, thereby accelerating the translation of microbiome insights into precision oncology.

Supplementary information

Table S1: The clinical trials of microbiome modulators in CRC

Author contributions

C.C. performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. Q.S. and Z.M. conducted the literature search and data collection. C.C. and Q.S. contributed to data interpretation and provided critical revisions. Y.D. assisted with methodology and analysis. Z.Z. and X.H. designed the study, conceptualized the research framework, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaokun Hua, Email: 43256647@qq.com.

Zhiyun Zhang, Email: jianchidaodi_2010@163.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41522-025-00818-3.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eng, C. et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet404, 294–310 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinicrope, F. A. Increasing incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.386, 1547–1558 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White, M. T. & Sears, C. L. The microbial landscape of colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.22, 240–254 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuipers, E. J. et al. Colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.1, 15065 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grothey, A. et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.378, 1177–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auclin, E. et al. Subgroups and prognostication in stage III colon cancer: future perspectives for adjuvant therapy. Ann. Oncol.28, 958–968 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson, A. B. et al. Colon Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw.22, e240029 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Zheng, H. et al. Targeted activation of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer via LGR4 targeting overcomes acquired drug resistance. Nat. Cancer5, 572–589 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, X. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum facilitates anti-PD-1 therapy in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell42, 1729–1746.e1728 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casak, S. J. et al. FDA Approval Summary: pembrolizumab for the first-line treatment of patients with MSI-H/dMMR advanced unresectable or metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.27, 4680–4684 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, E. & Zhou, W. Immunotherapy in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer: Strategies to overcome resistance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.212, 104775 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong, J. et al. Roseburia intestinalis sensitizes colorectal cancer to radiotherapy through the butyrate/OR51E1/RALB axis. Cell Rep.43, 113846 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng, Z. et al. The implication of gut microbiota in recovery from gastrointestinal surgery. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.13, 1110787 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes, M. R., Aggarwal, P., Costa, R. G. F., Cole, A. M. & Trinchieri, G. Targeting the gut microbiota for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer22, 703–722 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 55–71 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, M. et al. Gut microbiota metabolite indole-3-acetic acid maintains intestinal epithelial homeostasis through mucin sulfation. Gut Microbes16, 2377576 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keohane, D. M. et al. Microbiome and health implications for ethnic minorities after enforced lifestyle changes. Nat. Med.26, 1089–1095 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, J. & Sears, C. L. Antibiotic use impacts colorectal cancer: a double-edged sword by tumor location?. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.114, 1–2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartolomaeus, T. U. P. et al. Quantifying technical confounders in microbiome studies. Cardiovasc. Res.117, 863–875 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, N. N. et al. Multi-kingdom microbiota analyses identify bacterial-fungal interactions and biomarkers of colorectal cancer across cohorts. Nat. Microbiol.7, 238–250 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Rozadilla, C. et al. Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and East Asian ancestries. Nat. Genet.5‘5, 89–99 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouradov, D. et al. Oncomicrobial community profiling identifies clinicomolecular and prognostic subtypes of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology165, 104–120 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao, R. et al. Integrated analysis of colorectal cancer reveals cross-cohort gut microbial signatures and associated serum metabolites. Gastroenterology163, 1024–1037.e1029 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell, R. V., Visnovska, M., Biggs, P. J., Schmeier, S. & Frizelle, F. A. Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep.7, 11590 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuo, W., Michail, S. & Sun, F. Metagenomic analyses of multiple gut datasets revealed the association of phage signatures in colorectal cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12, 918010 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, F. et al. Meta-analysis of fecal viromes demonstrates high diagnostic potential of the gut viral signatures for colorectal cancer and adenoma risk assessment. J. Adv. Res.49, 103–114 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein, R. S. et al. Association of Streptococcus bovis with carcinoma of the colon. N. Engl. J. Med.297, 800–802 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Hul, M. et al. What defines a healthy gut microbiome?. Gut73, 1893–1908 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winter, S. E. & Bäumler, A. J. Gut dysbiosis: ecological causes and causative effects on human disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA120, e2316579120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilg, H., Adolph, T. E., Gerner, R. R. & Moschen, A. R. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell33, 954–964 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-García, J. J. et al. Diurnal interplay between epithelium physiology and gut microbiota as a metronome for orchestrating immune and metabolic homeostasis. Metabolites12, 390 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wong, C. C. & Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.20, 429–452 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knippel, R. J., Drewes, J. L. & Sears, C. L. The cancer microbiome: recent highlights and knowledge gaps. Cancer Discov.11, 2378–2395 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chagneau, C. V. et al. The pks island: a bacterial Swiss army knife? Colibactin: beyond DNA damage and cancer. Trends Microbiol.30, 1146–1159 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dziubańska-Kusibab, P. J. et al. Colibactin DNA-damage signature indicates mutational impact in colorectal cancer. Nat. Med.26, 1063–1069 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosendahl Huber, A., Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C. & Puschhof, J. A bacterial mutational footprint in colorectal cancer genomes. Br. J. Cancer124, 1751–1753 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosendahl Huber, A. et al. Improved detection of colibactin-induced mutations by genotoxic E. coli in organoids and colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell42, 487–496.e486 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopès, A. et al. Colibactin-positive Escherichia coli induce a procarcinogenic immune environment leading to immunotherapy resistance in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer146, 3147–3159 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butt, J. et al. Association of pre-diagnostic antibody responses to Escherichia coli and bacteroides fragilis toxin proteins with colorectal cancer in a European cohort. Gut Microbes13, 1–14 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugihara, K. et al. Mucolytic bacteria license pathobionts to acquire host-derived nutrients during dietary nutrient restriction. Cell Rep.40, 111093 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jans, M. et al. Colibactin-driven colon cancer requires adhesin-mediated epithelial binding. Nature635, 472–480 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalmasso, G. et al. Colibactin-producing Escherichia coli enhance resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs by promoting epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell emergence. Gut Microbes16, 2310215 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Oliveira Alves, N. et al. The colibactin-producing Escherichia coli alters the tumor microenvironment to immunosuppressive lipid overload facilitating colorectal cancer progression and chemoresistance. Gut Microbes16, 2320291 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin, Y. et al. Multi-cohort analysis reveals colorectal cancer tumor location-associated fecal microbiota and their clinical impact. Cell Host Microbe33, 589–601.e583 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brennan, C. A. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum drives a pro-inflammatory intestinal microenvironment through metabolite receptor-dependent modulation of IL-17 expression. Gut Microbes13, 1987780 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, Q. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer through neogenesis of tumor stem cells. J. Clin. Investig.135, e181595 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Li, D., Li, Z., Wang, L., Zhang, Y. & Ning, S. Oral inoculation of Fusobacterium nucleatum exacerbates ulcerative colitis via the secretion of virulence adhesin FadA. Virulence15, 2399217 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duizer, C. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum upregulates the immune inhibitory receptor PD-L1 in colorectal cancer cells via the activation of ALPK1. Gut Microbes17, 2458203 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ternes, D. et al. The gut microbial metabolite formate exacerbates colorectal cancer progression. Nat. Metab.4, 458–475 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]