Abstract

Background

Background Technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) has emerged as a significant form of violence against adolescents and young adults (AYA). However, evidence is limited regarding the prevalence of forms of TFA among AYA and how TFA from partners influences other outcomes related to AYA sexual health and wellbeing. The aim of this study was to examine the prevalence of TFA exposure among AYA in an agricultural region in the United States, to identify associated risk factors, and assess its relationship to later sexual, mental, and violence-related health outcomes.

Methods

We analyzed data from a prospective cohort study of eighth graders from Salinas, California followed over eight years. Pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing were conducted in emerging adulthood (~age 20). TFA was measured using a 6-item scale of Cyber Dating. Log-binomial models were used to estimate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between any TFA in early and middle adolescence (~ages 13-15) with sexual health, mental health and violence outcomes in emerging adulthood.

Results

Among 373 participants with follow-up data, the median age of participants at baseline was 13.7 years (interquartile range (IQR) 13.4, 14) and the majority were female (56.0%, n=216), Latine (95.9%, n=370) and had at least one parent or grandparent from Mexico (88.9%, n=343). Over the entire study period in early adolescence, 41.7% (n=161) of participants reported ever having TFA experiences but the percentage was roughly 20% at any one visit. The most reported TFA type was a partner repeatedly contacting the participant via some form of technology to see where they were/who they were with. Exposure to TFA in early or middle adolescence was associated with a higher likelihood of pregnancy before age 20 (RR 1.71; 95% CI 1.02, 2. 84) and an STI diagnosis in emerging adulthood (RR 2.22; 95% CI 1.19, 4.16) in adjusted models.

Conclusions

TFA was relatively common among AYA throughout adolescence and into emerging adulthood. TFA was associated with teen pregnancy and STI acquisition. Further work is needed to understand mechanisms for this relationship and to integrate TFA into existing intimate partner violence prevention programming and reduce the negative effects of TFA on sexual and reproductive health.

Plain English summary [250 words max]:

Technology is increasingly being used as a tool for abuse in relationships, especially among teenagers and young adults. This study looked at how common technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) is among adolescents and young adults in an agricultural region of California. We also explored how experiencing this type of abuse in early and middle adolescence (around ages 13-15) might affect reproductive health outcomes later in early adulthood.We followed a group of young people from their early teenage years into adulthood, checking in with them over eight years. At around age 20, we also tested for pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). TFA was measured by asking whether a romantic partner had used technology, such as texting or social media, to control or monitor them.We found that about 1 in 5 participants had experienced TFA during early adolescence, and this pattern remained consistent over time. The most common form of TFA was a partner repeatedly messaging or calling to check their location and who they were with. Our findings suggest that experiencing TFA as a teenager was linked to a higher chance of pregnancy before age 20 and a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with an STI in young adulthood.These results highlight that TFA is a serious and common issue that may have long-term impacts on young people’s health. More research is needed to understand why this link exists and to develop ways to prevent TFA and support young people in safe and healthy relationships.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12978-025-02128-5.

Keywords: Technology-facilitated abuse, Adolescents and young adults, Sexual and reproductive health

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is common in the United States (U.S.) and prevention constitutes an important public health priority due to adverse consequences across multiple health and wellbeing outcomes over the life course [1]. IPV starts early with 1 in 4 women and 1 in 5 men first experiencing it before age 18 [2]. The rapid expansion of digital technology has introduced new forms and modes to perpetuate IPV, which disproportionately affects young people. Technology-facilitated abuse (TFA), defined as the use of digital tools to harass, control, or threaten individuals, is an example of this, and includes a range of behaviors, from cyberbullying to intimate partner surveillance [3–5]. While evidence of the effects of TFA are still limited, emerging data suggests that like other forms of IPV, it impacts mental health, self-efficacy to enact preventative health behaviors, and health service utilization, and may ultimately extend to sexual and reproductive health outcomes (SRH) [6, 7].

Given high proportions of Latine adolescents report constantly being online [8] and face disproportionately high rates of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), examining their TFA exposure and its potential role in SRH outcomes constitutes a research priority. The concern for TFA’s impact on SRH is particularly pertinent for Latine youth in California, who account for 77% of all teen births in the state with higher rates among rural youth compared to urban peers [9, 10]. Among Latine youth, especially those in rural areas, additional barriers to care such as limited accessibility of culturally sensitive health services, other intersecting structural vulnerabilities, and experience of stigma and discrimination, may compound challenges to adopting health-promoting behaviors, leading to disproportionately adverse reproductive health effects [11, 12]. , [13] Yet, evidence is limited on the prevalence and characteristics associated with TFA among Latine youth and very few studies have used longitudinal data to examine how TFA may influence SRH outcomes among youth over time. Rigorous longitudinal evidence is needed to better identify those most at risk for TFA, inform the development of interventions to better prevent TFA, and address the consequences of TFA among youth.

The aim of this study was therefore to examine the prevalence of TFA exposure over time among Latine youth between early adolescence and young adulthood, to identify associated risk factors, and assess its relationship to SRH outcomes. By focusing on this understudied area, we aim to inform SRH research and interventions that address the unique needs of Latine youth exposed to TFA.

Methods

Study design

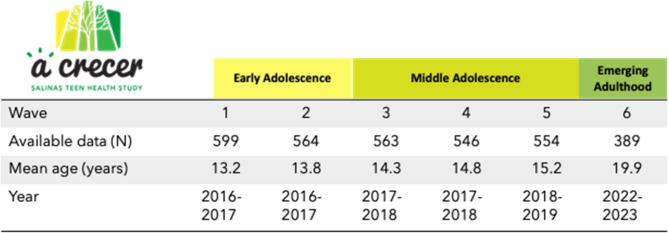

We used data from the prospective cohort study A Crecer, which aims to explore social factors influencing sexual health outcomes throughout adolescence and into emerging adulthood. The study followed a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach and was thus developed in partnership with the Monterey County Health Department and with input from youth and community advisory boards, who informed our research questions [14]. CBPR has been demonstrated to be of particular importance when conducting research with vulnerable populations, including youth and migrants, and when conducting research on sensitive topics such as violence and SRH [13]. It follows eighth graders from four public middle schools in Salinas, California. Here we present data collected from 2015 to 2023. Participants had a total of six study visits, referred to as waves 1–6, between the ages of 13 to 20 (Fig. 1). A description of the cohort and more detail about the CBPR approach are available elsewhere [14, 15].

Fig. 1.

Study Design

Setting

Salinas is an agricultural hub which produces much of the nation’s lettuce and other crops. While it benefits from a rich cultural diversity and strong community ties, it also faces challenges such as high poverty rates and community violence, which may negatively impact adolescent health. The area’s proximity to fresh produce and outdoor spaces provides opportunities for healthy living, but socioeconomic disparities prevent access to these opportunities and limited access to healthcare also present ongoing health concerns for youth.

Participants

Eligible participants were aged 12 to 15 years old, able to complete the study procedures in English or Spanish, intended to live in Salinas for the next year, and were willing to provide contact information for a parent. Of the 599 participants who were enrolled in the original cohort (Wave 1–5), 389 (65%) participants re-enrolled at Wave 6 approximately 6 years after initial enrollment (wave 6 mean age: 20 years). Our analysis includes all participants who reenrolled at Wave 6 to examine TFA exposures in early and middle adolescence (Waves 1–5, ages 13–15) with health outcomes in emerging adulthood (Wave 6).

Data collection

Surveys were interviewer-administered approximately every 6-months during Waves 1–5 and again at Wave 6 using computer-based questionnaires in English and Spanish (Fig. 1). Sensitive questions were completed independently by participants using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) in early and middle adolescence (Waves 1–5), and CASI without audio in emerging adulthood (Wave 6). Surveys captured data on structural (e.g. community-level protective and risk factors), interpersonal (e.g. family, peer, and partner relationship factors), and individual level (e.g. substance use, relationship qualities, mental health) factors theorized to influence SRH outcomes (e.g. self-reported sexual behaviors, partner violence, and health care service access). All Wave 1–5 study visits in early and middle adolescence were conducted in-person. In emerging adulthood, Wave 6 interviews were done in person or with a study interviewer over the phone or via videoconference. To facilitate accessibility of study participation, asynchronous visits could also occur with participants completing study interviews independently on a computer or smartphone. Data collection in emerging adulthood also included biological testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea (via vaginal swab or urine) and pregnancy (via urine sample). Participants who completed their visit remotely were offered a self-sample collection kit for STIs and pregnancy, including instructions for sample collection, which they returned by prepaid mail for laboratory analysis. Participants also had the option to upload STI results if they recently tested with an external medical provider within the same month of their visit or if they planned to test with an external medical provider after their visit.

Measures

The outcomes that were examined at Wave 6 in emerging adulthood were related to SRH, mental health (i.e. symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression) and violence (IPV victimization, IPV perpetration, TFA). Symptoms of depression (yes/no) were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) for adolescents using a cutoff of ≥ 10. The measure has been validated as correlated with the diagnosis of depression in national samples and Latine populations and used in prior publications from the A Crecer study [16, 17]. Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which is widely used to screen for GAD, assessing frequency of experiences over the past 2 weeks with scores ranging from 0 to 21 (0–9 no to mild anxiety; 10–14 moderate; 15–21 severe) [18]. In-person IPV victimization (yes/no) and IPV perpetration (yes/no) were asked in relation to the past six months, and measured using a five-item version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale [19–21]. Items included experiencing from a partner (victimization) or doing any of the following to a partner (perpetration): calling them names, insulting them, or treating them disrespectfully in front of others; swearing at them; threatening with violence or to hurt them; pushing or shoving them; or throwing something at them that could hurt them. The latter two items were considered physical abuse and the remaining items, psychological abuse.

SRH outcomes included teen pregnancy, any STI diagnosis, visited a clinic for sexual health services in the last 12 months (yes/no), participant or their partner used any birth control method other than condoms to avoid pregnancy in the last 12 months (always, sometimes, never), condom use at last sex (yes/no), and use of emergency contraception in the last 12 months (yes/no). Teen pregnancy was defined as becoming pregnant or getting someone pregnant before age 20. Participants assigned female sex at birth were asked if they had ever been pregnant and how old they were when their first pregnancy began. The self-reported teen pregnancy measure was complemented by urine-based pregnancy testing at the visit in emerging adulthood. Participants assigned male at birth were asked if they had ever gotten someone pregnant and how old they were when they first got someone pregnant.

Diagnosis of any STI was measured using a combined measure of self-report and biologically-detected chlamydia and/or gonorrhea. Via self-report, all participants were asked “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health care provider that you had a sexually transmitted infection?” If they answered yes, they were asked to select which STI had been diagnosed. Additionally, chlamydia and gonorrhea testing was conducted using a nucleic acid amplification test from a first catch urine sample or self-obtained vaginal swab (for participants with a vagina). Those testing positive were notified of their results by a study physician and referred for treatment to a provider or clinic of their choice at no cost to participants.

The exposure of TFA was self-reported using a 6-item scale of Cyber Dating Abuse that has been previously validated and used in AYA [22]. Responses were on a five-point Likert scale of frequency ranging from never to every day. Participants were asked “In the past 6 months, how many times has a partner done any of the following things using mobile apps, social networks, texts or other digital communication?” At wave 6, they were asked in relation to the past 12 months. Example items included “made mean or hurtful comments to you,” “repeatedly contacted you to see where you were/who you were with,” and “spread rumors about you.” Participants were defined as having experienced any TFA if responded that they were repeatedly contacted by a partner to see where they were/who they were with every day or almost every day or if they had ever experienced any of the other items. Participants who did not have a partner were coded as not having experienced TFA.

Drawing from approaches used in other violence exposure scales [23, 24], which incorporate frequency and severity into their assessment, an intensity score was also created from the TFA items. This was done by multiplying the number of abusive behaviors experienced by the frequency that they were experienced and by a measure of severity for each item. Severity scores ranged from 1 to 3 where 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. Items were scored by a group of staff (MH and MS and reviewed by the team) and were based on their prevalence, and assessments of the psychological or physical harm they are likely to cause. For example, posting nude pictures or image-based abuse, which was less common and has been associated with severe mental health concerns including PTSD and suicidality [25], was ranked higher than mean comments. The TFA intensity score was further categorized into low [1–3], medium [4–10], and high (10 and up) scores based on the distribution of scores within the sample.

Covariates

Potential confounders were measured at baseline and included age (years), sex at birth, neighborhood disorder (high vs. low), mother’s educational level (less than high school, high school/GED, more than high school), food insecurity (yes/no), and symptoms of depression (yes/no). Neighborhood safety was measured by the number of disorder events exposed to, out of 11 types, during the past year (e.g., “I saw people dealing drugs near my home”). A sum of the total number of events occurring at least once during the past year was calculated and was dichotomized as high (≥ 5 events) versus low (< 5 events) based on prior analyses [15]. Any substance use was defined as self-reporting use of alcohol, marijuana, prescription drugs or illicit drugs in the past 6 months. Food insecurity, was measured with two questions that assess limited or uncertain access to adequate food aligned with USDA assessments (e.g., “In the last 6 months, were you ever hungry but didn’t eat because there wasn’t enough money for food?” and “In the last 6 months did you ever eat less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money to buy food?”) [26].

Data analysis

First, we examined baseline (Wave 1) demographic characteristics among those who did and did not experience TFA at the Wave 2 study visit when it was first asked (median age 13.8 years). We reported frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. We then described individual TFA items over time at all visits and bivariate relationships between experiences of any TFA in early and middle adolescence (~ ages 13–15; wave 2–5) with outcomes in emerging adulthood (~ age 20; wave 6). Again, we reported frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Next, we used log-binomial models to estimate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between any TFA experienced from partners in early and middle adolescence (wave 2–5) with sexual health, mental health and violence outcomes in emerging adulthood (wave 6). Log-binomial models were selected because the outcome was dichotomous and because odds ratios are inflated if the outcome is common. In the case that log-binomial models did not converge, we used log-Poisson models with robust standard errors. We also explored interactions between TFA and sex at birth in all models and examined associations with TFA intensity and outcomes using log-binomial models similar to those described above.

Ethics

At study enrollment in 8th grade (Wave 1), all adolescents provided informed assent to participate following verbal parent permission. At the visit in emerging adulthood (Wave 6), all participants provided written informed consent as they were aged 18 years or older. Incentives were provided at each study visit and all youth received a referral guide to relevant community resources. At Waves 1–5, participants who screened positive for depression or had other mental health needs were offered a fast-track referral to behavioral health services through a mechanism established by the study with the local health department. At Wave 6, participants testing positive for STIs were contacted by a study physician to ensure treatment was accessed and available free of cost. Participants who reported experience of violence or screened positive for depression or had other mental health needs were offered referrals to behavioral health services. The RTI International Institutional Review board reviewed and approved all study procedures.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 386 participants had TFA data available on any TFA from wave 2–5 and were included in this analysis. The median age at enrollment was 13.7 years (interquartile range (IQR) 13.4, 14; Table 1). The majority of participants were female (56.0%, n = 216), Latine (95.9%, n = 370), of Mexican heritage (88.9%, n = 343), and were US-born to immigrant parent(s) (72.0%, n = 278). Around half (50.0%, n = 193) of participants had at least one parent who works in agriculture. At baseline (Wave 1), approximately 14% of the population reported symptoms of depression (13.7%, n = 53) and had used any alcohol, marijuana, prescription drugs, or illicit drugs in the past 6 months (17.4%, n = 67). Most (73.8%, n = 285) participants lived with both parents, 99.7% (n = 385) had contact with their mother, 90.2% (n = 348) had contact with their father, and 8.3% experienced food insecurity in the past 6 months (n = 32).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics in early adolescence (wave 1) by experience of any technology facilitated abuse (TFA) from Wave 2[AM1] [MS2] to 5 in early and middle adolescence [AM1]Perhaps a discussion point among us: the outcome in later tables is TFA experienced at all over time in Phase 1 - do you think it should be the same here (as in T2)? [MS2]Redid this for TFA from Wave 2-5 at any visit

| Any TFA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=225, 58.3%) | Yes (n=161, 41.7%) | Total (n=386) | p-value | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 13.7 | 13.4, 14 | 13.7 | 13.4, 14 | 13.7 | 13.4, 14 | 0.701 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 100 | 44.4 | 70 | 43.5 | 170 | 44.0 | 0.850 |

| Female | 125 | 55.6 | 91 | 56.5 | 216 | 56.0 | |

| Latine/-x ethnicity (at least one parent/grandparent) | 211 | 93.8 | 159 | 98.8 | 370 | 95.9 | 0.016 |

| Immigrant Generation | |||||||

| 1st: born outside the US | 26 | 11.6 | 18 | 11.2 | 44 | 11.4 | 0.826 |

| 2nd: US born/immigrant parent(s) | 161 | 71.6 | 117 | 72.7 | 278 | 72.0 | |

| 3rd+: US born and parents US born | 36 | 16.0 | 23 | 14.3 | 59 | 15. | |

| US born, generation unknown | 2 | 0.9 | 3 | 1.9 | 5 | 1.3 | |

| At least one parent/grandparent from Mexico | 197 | 87.6 | 146 | 90.7 | 343 | 88.9 | 0.336 |

| At least one parent works in agriculture | 108 | 48.0 | 85 | 52.8 | 193 | 50.0 | 0.353 |

| Crowded housing conditions | |||||||

| No | 101 | 44.9 | 85 | 52.8 | 186 | 48.2 | 0.068 |

| Crowding | 100 | 44.4 | 53 | 32.9 | 153 | 39.6 | |

| Severe Crowding | 24 | 10.7 | 23 | 14.3 | 47 | 12.2 | |

| Food insecurity/hunger, past 6 months | 11 | 4.9 | 21 | 13.0 | 32 | 8.3 | 0.004 |

| Frequent lifetime moves (5 or more)a | 33 | 14.7 | 35 | 21.7 | 68 | 17.6 | 0.187 |

| Neighborhood environment safety: Neighborhood disorder events experienced past 12 months, 8th grade | |||||||

| <5 types of events | 90 | 40.0 | 44 | 27.3 | 134 | 34.7 | 0.010 |

| 5+ types of events | 135 | 60.0 | 117 | 72.7 | 252 | 65.3 | |

| Living situation | |||||||

| Both parents (at least part time) | 173 | 76.9 | 112 | 69.6 | 285 | 73.8 | 0.212 |

| Mother only | 46 | 20.4 | 41 | 25.5 | 87 | 22.5 | |

| Other | 6 | 2.7 | 8 | 5.0 | 14 | 3.6 | |

| Has contact with mother | 225 | 100.0 | 160 | 99.4 | 385 | 99.7 | 0.237 |

| Has contact with father | 204 | 90.7 | 144 | 89.4 | 348 | 90.2 | 0.690 |

| Mother's education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 105 | 46.7 | 66 | 41.0 | 171 | 44.3 | 0.325 |

| High school/GED | 55 | 24.4 | 53 | 32.9 | 108 | 28.0 | |

| More than high school | 60 | 26.7 | 38 | 23.6 | 98 | 25.4 | |

| (Unknown) | 5 | 2.2 | 4 | 2.5 | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Symptoms of depression (PHQ-8-A) | 23 | 10.2 | 30 | 18.6 | 53 | 13.7 | 0.018 |

| Substance use in the past 6 months (alcohol, weed, illicit, prescription) | 21 | 9.3 | 46 | 28.7 | 67 | 17.4 | <0.001 |

7 participants were missing responses to number of moves

IQR Interquartile range, TFA Technology-facilitated abuse and included 7 items measuring exposure to abusive behaviors from a partner occurring online or over the phone, PHQ-8-A Patient Health Questionnaire-8 tailored for adolescents

a lifetime moves reported at visit 2

Exposure to TFA

A total of 161 (41.7%) reported TFA at any visit between wave 2–5. Most (21.2% n = 82) experienced TFA at 1 visit only, 10.4% (n = 40) at 2 visits, 7.8% (n = 30) at 3 visits, and 2.3% (n = 9) at 4 visits. At the first visit that these questions were asked (Wave 2), 20.9% (n = 80) of participants reported TFA experience in the past 6 months (Table 2), The most reported behavior experienced was a partner repeatedly contacting the participant to see where they were/who they were with. More than a quarter of participants reported this occurring at least a few times (26.2%, n = 79) with approximately 8% reporting the occurrence of this behavior every day or almost every day (7.6%, n = 23). The next most common behavior to experience was a partner making mean or hurtful comments over technology with 15.5% (n = 47) of participants reporting that this occurred at least a few times in the last 6 months. The remaining items were reported by a range of approximately 1–10% saying they had occurred a few times or more frequently. Reporting of individual TFA items were also similar by sex at birth (Supplementary Table 1) and remained similar throughout adolescence into emerging adulthood with approximately 20% of participants having experienced any TFA at each visit (Table 2). TFA was similar for those who did and did not re-enroll in wave 6 of the study (41.7% vs. 47.5% p = 0.198).

Table 2.

Experiences of TFA over time during the study

| Wave | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early and middle adolescence (~ages 13-15) | Emerging Adulthood (~age 20) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wave 2 (n=558) | Wave 3 (n=561) | Wave 4 (n=543) | Wave 5 (n=551) | Wave 6 (n=389) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||||||||||||||||

| Partner repeatedly contacted you to see where you were/who you were with | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 85 | 28.9 | 75 | 25.6 | 105 | 34.8 | 105 | 33.4 | 171 | 56.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 105 | 35.7 | 110 | 37.5 | 101 | 33.4 | 126 | 40.1 | 79 | 26.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 25 | 8.5 | 29 | 9.9 | 26 | 8.6 | 30 | 9.6 | 14 | 4.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 27 | 9.2 | 29 | 9.9 | 24 | 7.9 | 22 | 7.0 | 15 | 5.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 52 | 17.7 | 50 | 17.1 | 46 | 15.2 | 31 | 9.9 | 23 | 7.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner made mean or hurtful comments to you | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 244 | 82.7 | 254 | 86.7 | 270 | 89.4 | 266 | 84.7 | 256 | 84.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 44 | 14.9 | 32 | 10.9 | 26 | 8.6 | 36 | 11.5 | 36 | 11.9 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 3 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 9 | 2.9 | 4 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 3 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner spread rumors about you | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 259 | 87.8 | 268 | 91.5 | 280 | 92.7 | 290 | 92.4 | 283 | 94.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 30 | 10.2 | 19 | 6.5 | 19 | 6.3 | 21 | 6.7 | 11 | 3.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 2 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner made a threatening or aggressive comment to you | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 279 | 94.9 | 277 | 94.5 | 292 | 96.7 | 295 | 93.9 | 287 | 95.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 12 | 4.1 | 11 | 3.8 | 8 | 2.6 | 12 | 3.8 | 8 | 2.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner tried to get you to talk about sex when you did not want to | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 257 | 87.1 | 254 | 86.7 | 272 | 90.1 | 275 | 87.6 | 270 | 89.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 27 | 9.2 | 25 | 8.5 | 25 | 8.3 | 30 | 9.6 | 18 | 6.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 4 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 5 | 1.6 | 5 | 1.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 3 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 4 | 1.4 | 8 | 2.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner asked you to do something sexual that you did not want to do | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 257 | 87.4 | 254 | 86.7 | 271 | 89.7 | 280 | 89.2 | 273 | 90.4 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 28 | 9.5 | 27 | 9.2 | 22 | 7.3 | 27 | 8.6 | 13 | 4.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 7 | 2.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 2 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 5 | 1.7 | 7 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Partner posted or publicly shared a nude or seminude picture of you | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 283 | 96.3 | 286 | 97.6 | 291 | 96.4 | 303 | 96.5 | 299 | 98.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| A few times | 9 | 3.1 | 5 | 1.7 | 7 | 2.3 | 10 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a month | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Once or twice a week | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Every day or almost every day | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Any TFAa | 124 | 22.2 | 113 | 20.1 | 102 | 18.8 | 99 | 18.0 | 80 | 21.0 | ||||||||||||||||

TFA=technology facilitated abuse

aParticipants were defined as having experienced any TFA if responded that they were repeatedly contacted by a partner to see where they were/who they were with every day or almost every day or if they had ever experienced any of the other items

Participants who had reported any TFA from waves 2–5 were more likely at enrollment (Wave 1) to be Latine (98.8% vs. 93.8%, p = 0.016), food insecure (13.0% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.004), report lower neighborhood safety (72.7% vs. 60.0%, p = 0.010), experience symptoms of depression (18.6 vs. 10.2%, p = 0.018) and have ever used substances (28.7% vs. 9.3% p < 0.001; Table 1). Experiences of any TFA from Wave 2–5 were similar by sex at birth (43.5% among males vs. 56.5% among females; p = 0.850).

Associations between TFA and SRH outcomes

Table 3 shows bivariate relationships between any experience of TFA in early and middle adolescence (Wave 2–5) with outcomes in emerging adulthood (Wave 6). Participants who had experienced any TFA were more likely to have a teen pregnancy (< 20 years; 20.5% vs. 10.5%, p = 0.007), have any STI diagnosis through self-report or testing (17.3% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.001), to have visited a clinic for sexual health services in the last 12 months (39.2% vs. 26.5%, p = 0.008), and to have been a victim of IPV (19.0% vs. 11.6%, p = 0.045). Any experience of TFA in early or middle adolescence (wave 2–5) did not have a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) with condom use at last sex, depression, anxiety, IPV perpetration or TFA in emerging adulthood (wave 6).

Table 3.

Outcomes in emerging adulthood (wave 6) by any TFA experienced from partners during early and middle adolescence (wave 1–5)

| Any TFA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 225, 58.3%) | Yes (n = 161, 41.7%) | Total (n = 386) | p-value | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Teen pregnancy (pregnancy < age 20) | 23 | 10.5 | 32 | 20.5 | 55 | 14.6 | 0.007 |

| Visited clinic for sexual health services in last 12 months | 59 | 26.5 | 62 | 39.2 | 121 | 31.8 | 0.008 |

| Any STI diagnosis | 15 | 6.7 | 27 | 17.3 | 42 | 11.1 | 0.001 |

| Frequency of use of birth control | |||||||

| Always | 39 | 30.0 | 29 | 23.4 | 68 | 26.8 | 0.327 |

| Sometimes | 39 | 30.0 | 47 | 37.9 | 86 | 33.9 | |

| Never | 52 | 40.0 | 48 | 38.7 | 100 | 39.4 | |

| Emergency contraception use in last 12 months | 78 | 60.0 | 78 | 62.4 | 156 | 61.2 | 0.694 |

| Condom use at last sex | 49 | 38.3 | 57 | 45.6 | 106 | 41.9 | 0.238 |

| Symptoms of depression | 41 | 18.6 | 34 | 22.8 | 75 | 20.3 | 0.317 |

| Symptoms of anxiety | 135 | 60.0 | 111 | 68.9 | 246 | 63.7 | 0.072 |

| IPV Victimization yes/no | 26 | 11.6 | 30 | 19.0 | 56 | 14.7 | 0.045 |

| IPV Perpetration yes/no | 27 | 12.1 | 26 | 16.5 | 53 | 13.9 | 0.220 |

| Digital IPV Victimization yes/no | 41 | 18.3 | 39 | 24.8 | 80 | 21.0 | 0.123 |

IPV Intimate partner violence, TFA Technology facilitated abuse

Experiencing any TFA in early and middle adolescence was associated with accessing sexual health services in the last 12 months in unadjusted analyses (RR 1.48; 95% CI 1.11, 1.99) and with IPV victimization (RR 1.63; 95% CI 1.01, 2.65), but these ass

ociations were not statistically significant after adjusting for covariates. In multivariable analysis, participants who had experienced any TFA in early and middle adolescence were more likely to have a teen pregnancy (risk ratio (RR) 1.71; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02, 2.84) and any STI diagnosis in emerging adulthood (RR 2.22; 95% CI 1.19, 4.16), adjusting for covariates (Table 4). Any experience of TFA in early or middle adolescence (wave 2–5) was not associated with condom use at last sex, depression, anxiety, IPV perpetration or TFA in emerging adulthood (wave 6). Stratified estimates were similar by sex at birth but confidence intervals were wide because outcome events were small by sex at birth, limiting power (Appendix Table 2). When examining intensity of TFA exposure, those who had medium (RR 2.75; 95% CI 1.08–6.98) and high levels (RR 4.71; 95% CI 1.50–14.8) of TFA exposure at Waves 2–5 had a higher risk of IPV victimization, compared to those with no TFA exposure, adjusting for covariates (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 4.

Risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (Cis) for the association between TFA in early and middle adolescence (wave 2–5) on outcomes in emerging adulthood (wave 6)

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RRa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Teen pregnancy (pregnancy < age 20) | 1.96 (1.20, 3.22) | 1.71 (1.02, 2.84) |

| Accessed sexual health services in last 12 months | 1.48 (1.11, 1.99) | 1.27 (0.95, 1.70) |

| Any STI diagnosis | 2.57 (1.42, 4.67) | 2.22 (1.19, 4.16) |

| Condom use at last sex | 0.88 (0.71, 1.09) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.07) |

| Symptoms of depression | 1.22 (0.82, 1.84) | 1.16 (0.76, 1.76) |

| Symptoms of anxiety | 1.15 (0.99, 1.33) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.23) |

| IPV victimization | 1.63 (1.01, 2.65) | 1.45 (0.88, 2.41) |

| IPV perpetration | 1.36 (0.83, 2.25) | 1.20 (0.71, 2.02) |

| TFA in phase 2 | 1.36 (0.92, 2.00) | 1.09 (0.72, 1.64) |

aadjusted for sex, neighborhood disorder, food insecurity, mother’s education level, depression at baseline, substance use at baseline

RR Risk ratio, CI Confidence interval, STI Sexually transmitted infection, IPV Intimate partner violence, TFA Technology facilitated abuse

Bold p < 0.05

Discussion

This study, which represents one of the few longitudinal studies exploring an association between TFA and SRH [6, 22, 27], found that about one-fifth of youth in this predominantly Latine community were experiencing TFA at each study wave (within a 6-month period) and 40% had experienced TFA at any visit during early and middle adolescence. While there was a slight difference in the proportion of female and male youth who experienced TFA at any visit this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Critical risk factors for TFA in adolescence included facing food insecurity, experiencing higher neighborhood disorder, substance use, and experiencing depression. We also found a relationship between TFA exposure and several SRH outcomes, including teen pregnancy, access to SRH services, and self-reported STI diagnosis, as well as IPV victimization. These findings remained significant in adjusted models for teen pregnancy and self-reported STI diagnosis.

Results add to growing literature on TFA, particularly its association with SRH outcomes. Despite a theorized relationship, prior research has predominately looked only at SRH behaviors for associations with TFA, such as self-reported sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol or drugs [27, 28]. When health outcomes, as opposed to behaviors, have been examined, they typically focus on mental health [29–32]. Established relationships, however, between in-person IPV and SRH, such as susceptibility to HIV acquisition, serve as a model for understanding TFA exposure on SRH [33–35]. These suggest that violence exposure, even of a psychological nature, may erode physiological, psychological, and behavioral pathways to SRH [34–36].

It is important to further integrate TFA in SRH research, healthcare provision, and education. Our results, which indicated that those exposed to TFA visited a health clinic at higher rates than those not exposed, suggest that healthcare providers have an important opportunity to identify this form of partner violence and potentially mitigate health-related outcomes. IPV screening in healthcare settings, already a critical tool for detecting violence and linking individuals to care [37], may be adapted to include questions on digital abuse. In addition to health serves, school settings can offer an effective avenue for addressing TFA and promoting healthy relationships [38]. In states like California, where comprehensive sexual education is mandated by the California Healthy Youth Act [39], integrating content on TFA—including digital consent, online harassment, and boundary-setting—into existing curricula can equip adolescents with the knowledge and skills to recognize abusive behaviors and seek support. Schools can also incorporate this content into broader health or life skills programs, ensuring that education on digital and relational safety reaches all students, regardless of their sexual health curriculum exposure. Finally, these findings also underscore the potential utility of advocacy or empowerment-based responses in both sectors, which center survivors’ needs and offer holistic support through safety planning, legal and digital literacy, and access to care [40]. While most advocacy-based interventions have addressed in-person IPV, these approaches should be expanded to address TFA, especially among youth from marginalized communities such as rural Latine adolescents. Together, these intersecting strategies represent critical entry points to reduce the harm associated with TFA and improve adolescent health outcomes.

Violence research often focuses on victimization among women and girls, given globally higher proportions of violence exposure and more severe impacts for this population [41]. Our study, however, showed that a large proportion of males also experience TFA behaviors. This is in line with research with this study population in early adolescence that showed that approximately 20% of participants experienced in-person dating violence at each visit, with levels similar regardless of sex [19]. Other research on TFA has indicated similar findings, although sometimes pointing towards more detrimental impacts among girls [29]. This points to a need for further research to understand differences by sex, as well as a need for comprehensive healthy relationship education to be incorporated as part of sexual education for all youth.

Few studies have yet examined whether youth of different sexual or gender identities are at higher risk [27]. In this study, we were unable to assess differences by sexual identity or gender identity given measurement issues and because our sample was not large enough. Sexual identity (e.g. gay, bisexual etc.) was only assessed at Wave 6. Sexual attraction was assessed in early and middle adolescence with response options of same-sex, opposite-sex or both/either, or neither, but does not always correlate with identity. We also did not have self-reported sexual identity which would influence TFA risk, and sexual attraction changed widely across the study period. In terms of gender identity, gender was not asked at enrollment and few participants at later waves identified as genders other than cisgender men and cisgender woman. Given the limited sample, we could not examine differences for AYA who identified as transgender, nonbinary, or other genders. We will further assess differences in TFA by sexual and gender identity in our ongoing, supplementary work to enroll additional participants who identify as LGBTQ + where we will be able to examine these questions with more power.

Finally, our findings on associated risk and protective factors, particularly those related to food insecurity, neighborhood safety, and substance use suggest further avenues for prevention. There is an established body of evidence pointing towards the effectiveness of economic empowerment interventions (which could reduce food insecurity and housing insecurity, which are often associated with violence exposure), the use of bystander interventions to enhance environmental safety, treatment for substance use, and parenting programs for the prevention of violence [42]. Given the broader structural inequities affecting Latine youth, a health equity framework underscores the need for multi-level interventions that address these social determinants of health and reduce disparities in SRH outcomes [13, 43].

There are some limitations to this work. For one, our sample was relatively small (n = 386). While this is sufficient for our primary analysis, it makes our stratified analysis by sex, and our analysis by intensity level, less robust. A larger sample may be necessary to make stronger conclusions around the relative impact among youth of different sexes, gender identities, and sexual orientation, and of varying intensities of TFA, which would be important for future programming. Our results also do not provide a causal link between TFA and SRH outcomes. However, the longitudinal nature of our data strengthens the findings, particularly in relation to limited longitudinal data on TFA [27]. Another limitation was our reliance on retrospective self-reported STI measures. Although STI testing data were available, testing was declined by more than one-third of participants. Self-reported data are subject to potential inaccuracies, influenced by social desirability bias, and may not account for asymptomatic or undiagnosed infections. Our use of Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (CASI), however, should have minimized reporting biases related to STI diagnosis. Lastly, there were slight differences in sex and coital debut (< age 15) among participants who did and did not re-enroll in wave 6 of the study, but we did not find any differences in TFA. Models adjusted for sex but is possible that estimates may be biased towards the null.

Two further unmeasured concepts, which may influence our understanding of Latine youth vulnerability to TFA are cultural norms and onset of puberty. While we examined immigrant generational status and found no significant differences in TFA exposure across groups, we did not directly assess family customs or cultural traditions. Generation status may not fully reflect important cultural dimensions—such as traditional gender norms, family communication, or acculturation stress—that could shape how youth experience or report TFA [44]. Although these factors have had inconsistent associations with IPV [45], they may be important to explore in future research. Similarly, we did not assess pubertal timing, such as early menarche (before age 11), which is associated with elevated risk for IPV and other SRH concerns (e.g., early sexual activity, depressive symptoms, STIs) [46, 47].

Conclusions

Notwithstanding limitations, this longitudinal study on the association between TFA exposure and SRH outcomes adds important evidence to our understanding of the impact of TFA on SRH for Latine youth. Its identification of critical risk factors such as food insecurity, neighborhood safety, and depression point towards important avenues of intervention, as does the finding that males and females may face similar levels of TFA. While the relationship between TFA and teen pregnancy and self-reported STI diagnosis are concerning, increased healthcare visits among TFA-exposed youth offer further opportunities for the healthcare system to detect and respond to violence using screening and advocacy-based interventions. Future research should explore the pathways between TFA and SRH outcomes, as well as conduct participatory work with youth to design youth-friendly and culturally relevant prevention strategies that can be integrated into existing sex education or life skills school curricula.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study team members, community advisory board and participants who made this study possible.

We would like to acknowledge the study team members, community advisory board and participants who made this study possible.

Abbreviations

- ACASI

Audio-computer assisted self-interview

- AYA

Adolescents and young adults

- Cis

Confidence intervals

- GAD

Generalized anxiety disorder

- IPV

Intimate partner violence

- IQR

Interquartile range

- RR

Risk ratio

- SRH

Sexual and reproductive health

- STIs

Sexually transmitted infections

- TFA

Technology-facilitated abuse

- US

United States

- USDA

United States Food Administration

Authors’ contributions

AMM is the Principal Investigators of this study. MH and MS are joint first and lead authors. MS and MH conducted analyses for the study and wrote the paper together. MS, and EB are statistical and quantitative experts on the overall study and data management. AJA, CR, DR conducted interviews for the study and did data collection. MRF, NLB, MKSQ provided technical input on study design and study implementation. MKSQ managed study implementation. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01HD075787 and K23HD093839. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Data availability

Data are not publicly available but can be requested from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The RTI Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved study procedures. All participants provided informed consent or assent. All research was carried out in accordance with international guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Miriam Hartmann and Marie Stoner are joint first-authors.

References

- 1.CDC. About Intimate Partner Violence Atlanta, Georgia CDC. 2024 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/index.html..

- 2.Leemis RW, Friar N, Khatiwada S, Chen MS, Kresnow M-j, Smith SG et al. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2016/2017 report on intimate partner violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nisvs/documentation/nisvsReportonSexualViolence.pdf.

- 3.Bailey J, Burkell J. Tech-facilitated violence: thinking structurally and intersectionally. J Gender-Based Violence. 2021;5(3):531–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn S. Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based violence: an overview. Centre for International Governance Innovation; 2020. Available from: https://www.cigionline.org/publications/technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence-overview/.

- 5.Mitchell M, Wood J, O’Neill T, Wood M, Pervan F, Anderson B, Arpke-Wales W. Technology-facilitated violence: A conceptual review. Criminology & Criminal Justice. 2022;25(2):649-69. 10.1177/17488958221140549. (Original work published 2025).

- 6.Read-Hamilton S, Bovell A, Clark E, Cunningham J, Alvarez F. Exploring the Links Between Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health: IGWG Gender-Based Violence Task Force; 2023 [Available from: https://www.igwg.org/2023/09/exploring-the-links-between-technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence-and-sexual-and-reproductive-health/.

- 7.Huber A. A shadow of me old self’: the impact of image-based sexual abuse in a digital society. Int Rev Victimology. 2023;29(2):199–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022. Pew Res Cent. 2022;10. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/08/PI_2022.08.10_Teens-and-Tech_FINAL.pdf.

- 9.MCAH. Adolescent births in california. california.Department of public health. Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DMCAH/surveillance/Pages/adolescent-births.aspx.

- 10.Hamilton BE, Rossen LM, Branum AM. Teen Birth Rates for Urban and Rural Areas in the United States, 2007-2015. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(264):1-8. PMID: 27849147. [PubMed]

- 11.Gonzalez FR, Benuto LT, Casas JB. Prevalence of interpersonal violence among latinas: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020;21(5):977–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santacrose DE, Kia-Keating M, Lucio D. A systematic review of socioecological factors, community violence exposure, and disparities for Latinx youth. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(5):1027–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schminkey DL, Liu X, Annan S, Sawin EM. Contributors to health inequities in rural Latinas of childbearing age: an integrative review using an ecological framework. Sage Open. 2019;9(1):2158244018823077. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comfort M, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald C, McGlone L, Chavez M, Minnis A. Community-engaged research with rural Latino adolescents: design and implementation strategies to study the social determinants of health. Gateways. 2018;11(1):90–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minnis AM, Browne EN, Chavez M, McGlone L, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald C. Early Sexual Debut and Neighborhood Social Environment in Latinx Youth. Pediatrics. 2022;149(3):e2021050861. 10.1542/peds.2021-050861. PMID: 35137189; PMCID: PMC9150543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Raymond-Flesch M, Browne EN, Auerswald C, Minnis AM. Family and school connectedness associated with lower depression among Latinx early adolescents in an agricultural County. Am J Community Psychol. 2021;68(1–2):114–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyce SC, Deardorff J, Minnis AM. Relationship factors associated with early adolescent dating violence victimization and perpetration among Latinx youth in an agricultural community. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(11–12):NP9214–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dick RN, McCauley HL, Jones KA, Tancredi DJ, Goldstein S, Blackburn S, et al. Cyber dating abuse among teens using School-Based health centers. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson MP. Measuring intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A compendium of assessment tools: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury. 2006. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11402.

- 24.Bettio F, Ticci E, Betti G. A fuzzy index and severity scale to measure violence against women. Soc Indic Res. 2020;148(1):225–49. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paradiso MN, Rollè L, Trombetta T. Image-Based sexual abuse associated factors: A systematic review. J Family Violence. 2024;39(5):931–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ERS U. Definitions of Food Security Washington, DC [Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/.

- 27.Kim C, Ferraresso R. Examining Technology-Facilitated intimate partner violence: A systematic review of journal articles. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(3):1325–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Ouytsel J, Torres E, Choi HJ, Ponnet K, Walrave M, Temple JR. The associations between substance use, sexual behaviors, bullying, deviant behaviors, health, and cyber dating abuse perpetration. J School Nurs. 2017;33(2):116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed LA, Tolman RM, Ward LM. Gender matters: experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. J Adolesc. 2017;59:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champion A, Oswald F, Pedersen CL. Technology-facilitated sexual violence and suicide risk: A serial mediation model investigating bullying, depression, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness. Can J Hum Sexuality. 2021;30(1):125–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantu JI, Charak R, Unique. Additive, and interactive effects of types of intimate partner cybervictimization on depression in Hispanic emerging adults. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(1–2):NP375–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champion AR, Oswald F, Khera D, Pedersen CL. Examining the gendered impacts of technology-facilitated sexual violence: A mixed methods approach. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51(3):1607–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell J, Wight M, Van Heerden A, Rochat TJ. Intimate partner violence, HIV, and mental health: a triple epidemic of global proportions. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(5):452–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts ST, Flaherty BP, Deya R, Masese L, Ngina J, McClelland RS, et al. Patterns of gender-based violence and associations with mental health and HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in mombasa, kenya: a latent class analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3273–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuyuki K, Cimino AN, Holliday CN, Campbell JC, Al-Alusi NA, Stockman JK. Physiological changes from violence-induced stress and trauma enhance HIV susceptibility among women. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(1):57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern cape, South Africa. Aids. 2006;20(16):2107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller CJ, Adjognon OL, Brady JE, Dichter ME, Iverson KM. Screening for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: an implementation-oriented systematic review. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2:26334895211039894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melendez-Torres GJ, Bonell C, Shaw N, Orr N, Chollet A, Rizzo A, et al. Are school-based interventions to prevent dating and relationship violence and gender-based violence equally effective for all students? Systematic review and equity analysis of moderation analyses in randomised trials. Prev Med Rep. 2023;34:102277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.California Education, Code. Sections 51930–51939: California Healthy Youth Act [Internet], (2023).

- 40.Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L, Davidson LL, Dunne D, Eldridge S, et al. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):Cd005043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO. Violence against women prevalence estimates. 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. 2021.

- 42.Chelsea U, Avni A, Angela B, Shikha C, Flávia D, Mary E. Interventions to prevent violence against women and girls globally: a global systematic review of reviews to update the RESPECT women framework. BMJ Public Health. 2025;3(1):e001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson A, Charles V, Yeung D, Coyle K. The health equity framework: A Science- and Justice-Based model for public health researchers and practitioners. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(6):741–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez MJ, Ramirez SO, Frietze G, Field C, Zárate MA. A Meta-Analysis of Latinx acculturation and intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020;21(4):844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cummings AM, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Sandoval MF. Intimate partner violence among hispanics: A review of the literature. J Family Violence. 2013;28(2):153–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibitoye M, Choi C, Tai H, Lee G, Sommer M. Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0178884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graber JA, Nichols TR, Brooks-Gunn J. Putting pubertal timing in developmental context: implications for prevention. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(3):254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available but can be requested from the corresponding author.