Abstract

Background

As a member of Rutaceae family, Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. represents a prominent medicinal plant and economically valuable crop in traditional Chinese medicine, and is renowned for its therapeutic efficacy in treating dermatological conditions. The pharmacological activity of this species primarily stems from quinoline alkaloids and limonoids, which predominantly accumulate in the taproots. These bioactive compounds serve as critical determinants of both medicinal quality and crop yield. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms governing their dynamic accumulation patterns in D. dasycarpus taproots remain uncertain, and the fundamental biochemical basis underlying this process has yet to be elucidated.

Results

Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses were carried out to investigate metabolites and gene expression during the development of D. dasycarpus taproots. The differentially accumulated secondary metabolites (DAMs) mainly included quinoline alkaloids and limonoids, and the accumulation of total alkaloids and total limonoids primarily occurred during 2- and 4-year-old. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are related to Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis, Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis, Tryptophan metabolism, Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis, which had a close relationship with the accumulation of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids. Furthermore, we identified that some CYP450s, acetyltransferase, isomerase, 2-ODDs and others may play an important role in the process of producing quinoline alkaloids and limonoids.

Conclusion

These results elucidated the molecular mechanisms and metabolic changes underlying the dynamic accumulation process occurring in the taproots of D. dasycarpus. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the planting and harvesting of D. dasycarpus.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07378-w.

Keywords: Taproot development, Metabolites accumulation, Gene regulatory, Quinoline alkaloids, Limonoids

Background

During the growth process, plants convert carbon dioxide and water into organic compounds, primarily sugars such as glucose, through photosynthesis [1]. Some of these sugars are utilized by plants in the process of respiration to provide energy for growth, development, and metabolism [2]. The remaining sugars are transformed into polysaccharides like starch and stored in plant organs such as roots, stems, and leaves for future use. Secondary metabolites are a class of non-essential metabolic substances produced by plants during their long-term evolutionary process, mainly including terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and alkaloids [3]. These substances play significant roles in plant defense, attracting pollinators, and adapting to the environment. For example, some terpenoids have insect-repelling and antibacterial effects, helping plants resist diseases and pests [4]. Anthocyanins, a type of phenolic compound, give flowers, fruits, and others with various colors, which assists in attracting insects for pollination and seed dissemination [5]. Alkaloids exhibit certain toxicity, preventing plants from being overgrazed by animals [6]. These secondary metabolites also exhibit tissue-specific accumulation. For example, roots are major sites for the biosynthesis of alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds, which serve as chemical defenses against soil-borne pathogens and herbivores. Nicotine in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) is synthesized in roots and transported to aerial tissues [7]; Ginsenosides in Panax ginseng accumulate predominantly in root tissues [8]. Leaves are primary sites for flavonoid and terpenoid biosynthesis, which protect against UV radiation and herbivory. Flavonol glycosides in Arabidopsis accumulate in leaf trichomes and epidermal cells [9]; Monoterpenes in mint (Mentha spp.) are synthesized in glandular trichomes [10]. Fruits and seeds often accumulate specialized metabolites that deter pests or attract seed dispersers. In tomato: carotenoids (lycopene and β-carotene) are synthesized in chromoplasts during fruit ripening [11]; Glycoalkaloids (α-tomatine) are concentrated in green fruits but degrade upon ripening [12]. Furthermore, modern pharmacological research has shown that most secondary metabolites of plants possess anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and other bioactivities [13].

The root bark is the medicinal part of D. dasycarpus, which is recorded as “Dictamni Cortex” in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China 2020 Edition [14]. Dictamni Cortex has curative effects on clearing heat and dampness, dispelling wind and detoxification, which have various effects including antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, insecticidal, anti-tumor, hepatoprotective, cardiovascular function-improving, and neuroprotective [15]. D. dasycarpus is mainly distributed in Northeast China, North China, East China, as well as in Henan, Shanxi, Gansu, Sichuan, Guizhou and other regions, with Liaoning province being one of the major producing areas [16]. The main cultivation bases for D. dasycarpus in Liaoning Province are located in Benxi City, Dandong City, Fushun City, and Chaoyang City. The locally suitable growth environment ensures the high quality of dictamni cortex.

The accumulation level of active components in medicinal plants determines their quality in traditional Chinese medicine. Most of these active components are secondary metabolites, which are closely related to the developmental stages and growing seasons of medicinal plants [17]. In the commercial production of these plant products, the time when the total biomass and the main medicinal components reach their peak is often selected as the optimal harvesting time (the best harvesting period) [18]. D. dasycarpus mainly contains alkaloids, limonoids, flavonoids, sesquiterpenoids and their glycosides, steroids, etc. Currently, more than 300 components have been isolated from its root bark [19]. Among them, quinoline alkaloids and limonoids account for the largest proportion. Previous studies have shown that among the different parts of D. dasycarpus (taproot, fibrous root, leaf, flower, kernel), the bark of the taproot has the highest content of dictamnine, obacunone, and fraxinellone, and this content changes with the planting years [20]. Therefore, the taproot is the primary commercial part of D. dasycarpus.

Currently, the molecular mechanisms and material basis underlying the dynamic accumulation process of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids in the taproots of D. dasycarpus have not been elucidated. Therefore, this study integrates metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses to identify key genes and enzymes influencing the accumulation of components in the taproots of D. dasycarpus, laying the foundation for future quality control and genetic improvement of this plant.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Our previous investigation showed that D. dasycarpus can generally be harvested in 3 to 4 years after artificial cultivation. Therefore, in this study, we collected our plant samples in June 2024. 2-, 4- and 6-year-old. D. dasycarpus plants were selected from Qingyuan Manchu Autonomous County, Fushun city, Liaoning province at an individual base (124°20′06-125°28′58″E, 41°47′52″ −42°28′25″N, Altitude:1100.1 m). Official permits were not required for the collection of D. dasycarpus, because the species is not a national key protected plant, and the specimens were not taken from wild populations. The formal identification of morphological characters was performed by professor Haibo Yin of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The D. dasycarpus voucher specimen (specimen serial number 210422LY0134) was deposited in the herbarium of the National Resource Center for Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences. After washing with clean water, the taproots were removed and cut into 0.3 cm pieces, then stored in liquid nitrogen in 50 mL centrifuge tubes.

Paraffin section

For examination of anatomical structure, 3 mm slices were cut from the fresh taproots, and were immediately submersed in 20 mL of a solution of formalin-glacial acetic acid-alcohol (FAA, Solarbio, Beijing, China) and left for 48 h. Preparation of paraffin sections followed the method described in CaneneAdams [21]. Then, paraffin sections were stained by following the manual from Saffron O- solid green Plant Tissue stain kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and observed through panoramic scanning (white light) via Pannoramic Desk, Pannoramic MIDI, and Pannoramic 250 Flash (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary). The images were handled by using SlideViewer software.

Secondary metabolites analysis and determination of total quinoline alkaloids and limonoids

A vacuum freeze-drying machine (5424R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) was used to dry the samples, and they were then ground to powder using a tissue grinder (Bead Ruptor 12, Omni International, Bedford, USA). Samples were then subjected to methanol extraction.1000 mg powder was dissolved in 25 mL methanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Then, the solution was centrifuged for 10 min after 1 h of heat reflux circulating extraction (80℃), and the supernatant was extracted and filtered in preparation for UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS analysis.

The UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MSE system consisted of a Waters ACQUITY I-class UPLC and Xevo G2-XS Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Chromatographic separation was achieved using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, Manchester, United Kingdom). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (H2O containing 0.1% formic acid, v/v, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and solvent B (acetonitrile, v/v, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The gradient program included 5–30% B from 0 to 10 min, 30–50% B from 10 to 20 min, 50–55% B from 20 to 28 min, 55–65% B from 28 to 35 min, 65–95% B from 35 to 38 min,95−5% B from 38 to 43 min, and with a postrun of 3 min for column equilibration. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, and the temperature was 40℃.

The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 50 to 1000 and a scan time of 0.2 s. The low collision energy was 6 eV, and the high collision energy was ramped from 12 to 25 eV. MSE analysis was employed for simultaneous acquisition of the exact mass of small molecules at high and low collision energies. All data processing was performed using Masslynss 4.1 software.

By consulting MassBank, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry mass spectrometry database, NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), Chemspider and other databases, the molecular formula, accurate molecular weight, primary mass spectrometry, secondary mass spectrometry and pyrolysis methods of the compounds contained in the plants of Dictamnus L. were obtained. The accurate molecular weight of the collected compounds was compared with the theoretical molecular weight. The isotope abundance and primary and secondary mass spectra of the chromatographic peaks were obtained by UPLC-Q-TOF-MSE, and compared with the retention time and secondary mass spectra of some reference substances to confirm the inferred components.

Transcriptome sequencing analysis

The transcriptome analysis was conducted by the Metware Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Total RNA was extracted by ethanol precipitation and CTAB-PBIOZOL. After successful extraction, RNA was dissolved by adding 50 µL of DEPC treated water (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Subsequently, total RNA was identified and quantified using a Qubit fluorescence quantifier (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and a Qsep400 high-throughput biofragment analyzer (BiOptic, Taipei, China). The reads were filtered for quality and were trimmed, and then assembled [22]. TransDecoder (https://github.com/TransDecoder/) was used to perform CDS prediction of Trinity assembled transcripts to obtain the corresponding amino acid sequences. Unigene sequences were aligned with KEGG, NR, Swiss-Prot, GO, COG/KOG, and Trembl databases using DIAMOND 2.0.9 software, and amino acid sequences were aligned with the Pfam database using the HMMER 3.3.2 software to obtain the annotation information of transcripts from these seven major databases. The expression level of transcripts was calculated using RSEM 1.3.1 software, and then the FPKM (Reads Per Kbper Million reads) of each transcript was calculated according to the transcript length [23]. FPKM is currently the most commonly used method to estimate gene expression levels. Those with biological replicates were analyzed for differential expression between the two groups using DESeq2 1.22.3 software, and those without biological replicates were analyzed for differences using edgeR 3.24.3 software, with P values corrected using the Benjamini & Hochberg method [24]. The corrected P-value as well as log2|Fold Change| were used as thresholds for significant differential expression. Enrichment analysis was performed based on the hypergeometric test. For KEGG, the hypergeometric distribution test was performed on the basis of pathway; for GO, it was performed on the basis of GO term. Transcription factor prediction was performed using iTAK 1.7a software. SSR analysis was performed using MISA, and SSR primer design was performed using Primer3 web version 4.1.0. Raw data generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database, under the accession number PRJNA1191163.

RT-qPCR analysis

The RNA-seq results were then validated. Total RNA from D. dasycarpus taproots from 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old plants was extracted using a Plant RNA Midi kit (Omega Bio-tech, lnc., USA). BlastTaq™ 2X qPCR MasterMix (Applied Biological Materials Biotech lnc., Canada) was used to reverse transcribe the RNA to cDNA. An Archimed™-X4 Quantitative PCR Detection System (Applied Archimed Analyzer) was used to perform the RT-qPCR reactions. The primers used in the reactions were designed using Primer 3 web version 4.1.0, and are given in Table S1. The actin and GAS6 genes were used as an endogenous control, and relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The GraphPad prism10 was used for visualization.

Statistical and data analysis

GraphPad Prism 10.0 software was employed in analyzing all data, and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). T-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed for comparisons between two and more groups accordingly. A P value of < 0.05 was deemed statistically different.

Results

Growth of D. dasycarpus taproots at different developmental stages

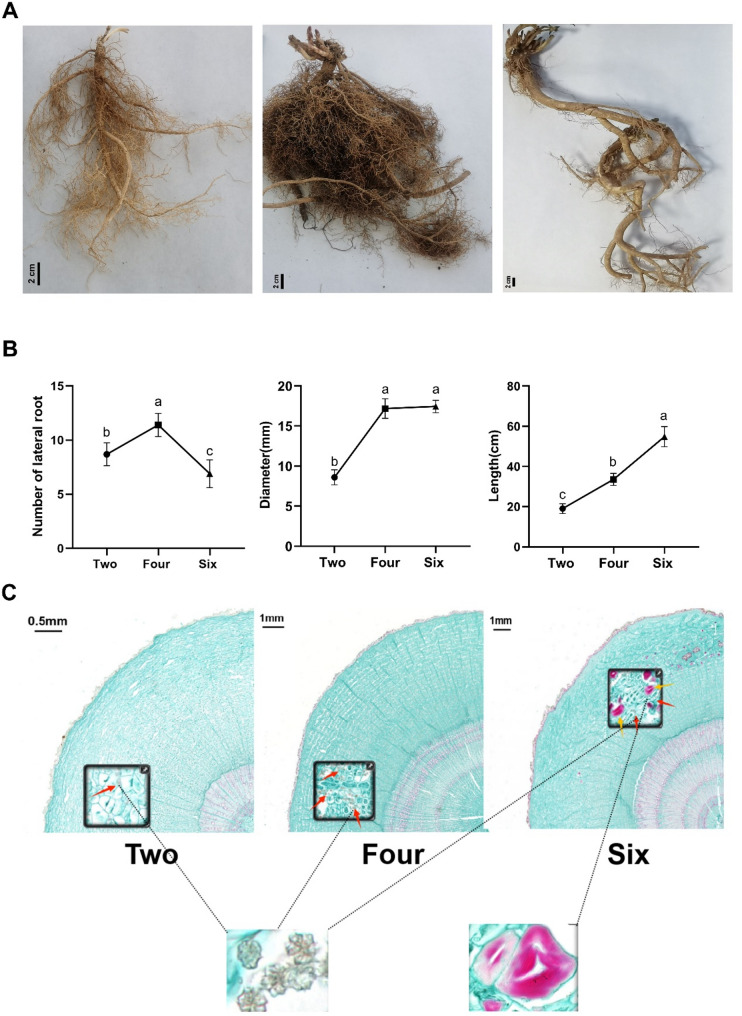

To revel the changes of growth trend during the development of D. dasycarpus taproots, we measured the growth index, and morphological structure over three growth years. The largest number of lateral roots was found in plants 4-year-old. The length was significantly increased from 2-year-old to 6-year-old, and the diameter was significantly increased from 2-year-old to 4-year-old but then turned to be unchanged from 4-year-old to 6-year-old (Fig. 1B), which indicated that the most important period of active ingredient accumulation was from 2-year-old to 4-year-old and it was positively correlated with the year of growth years in D. dasycarpus. From the panoramic scan of D. dasycarpus taproots cross sections, we found that calcium oxalate clusters were distributed in phloem parenchyma cells at three developmental stages. The number of calcium oxalate clusters in 4-year-old was greater than that in 6-year-old and it was hardly to be observed in 2-year-old (Fig. 1C). Moreover, some parenchyma cells near the vascular bundle were full of starch granules in 4-year-old. Both the calcium oxalate clusters and starch granules were closely related to metabolic activity, which also indicated that the active ingredient accumulation was occurred in the fourth year.

Fig. 1.

Morphology of D. dasycarpus taproots at different growth stages. A Growth performance, B Growth index, C Morphological structure of taproots in 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old plants. Arrows indicate the different metabolites. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). Columns with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

Changes of secondary metabolites in D. dasycarpus taproots between different growth stages

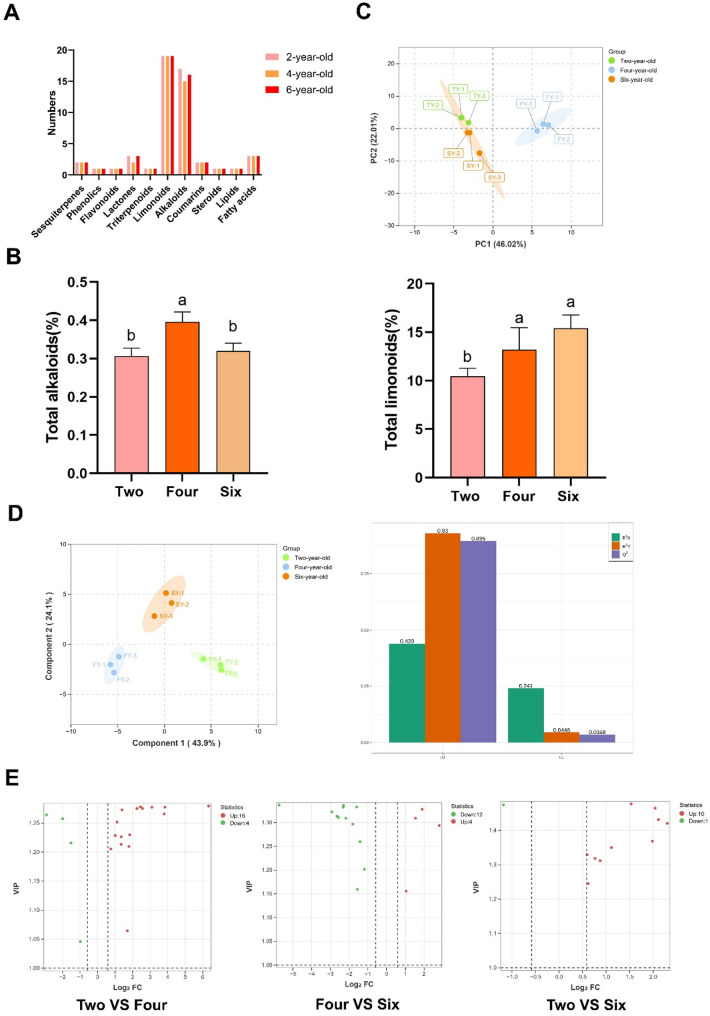

On the basis of the secondary metabolites database (Table S2) of D. dasycarpus, we identified the different chemical compositions, calculated the total alkaloids and total limonoids in taproots in 2-, 4- and 6-year-old plants using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS-based method. A total of 51 secondary metabolites in 2-year-old plants, 48 secondary metabolites in 4-year-old plants and 50 secondary metabolites in 6-year-old plants including alkaloids, limonoids, sesquiterpenes, lactones, coumarins, flavonoids, lipids, triterpenoids, phenolics, fatty acids and steroids (Table S3 and Fig. 2A). Based on the semi-quantitative method, the total alkaloids and total Limonoids significantly increased between 2- and 4-year-old plants but did not significantly differ between 4- and 6-year-old plants (Fig. 2B), which indicated that the accumulation of alkaloids and Limonoids primarily occurred during 2- and 4-year-old. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the three biological replicates from each group clustered tightly together, indicating that the secondary metabolic data were highly repeatable and reliable (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Multivariate statistical analysis of metabolome data in taproot samples of three different ages. A Compound classification and statistics. B Total alkaloids and total limonoids. C PCA score plot. D OPLS-DA and Validation. E Volcano of secondary metabolites with differences in relative abundance in different comparison groups. Red and blue dots represent the numbers of genes with increases or decreases in relative abundance respectively. Columns with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

To investigate the dynamic changes in the accumulation of the identified secondary metabolites, orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis(OPLS-DA) and Volcano Plot (log2|Fold Change|>1.5 and VIP>1) were performed (Table S4; Fig. 2D and E), which produced 20 DAMs mainly including 6 alkaloids and 8 Limonoids in the 2-year-old to 4-year-old taproots, and 16 DAMs including 6 alkaloids and 5 Limonoids in the 4-year-old to 6-year-old taproots. Given the three sample groups in this study, we performed one-way ANOVA to assess inter-group variations and identified 19 significantly altered secondary metabolites with VIP >1, FDR (False Discovery Rates) < 0.1, P < 0.05 (Table S5).

Transcriptomics analysis in D. dasycarpus taproots at different growth stages

To elucidate the potential molecular basis of taproot development in D. dasycarpus, we conducted global transcriptomic analyses via RNA-seq. Nine samples were subjected to transcriptome sequencing based on the Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) technology of Illumina novaseqXplus (Illumina, USA) high-throughput sequencing. This approach yielded a total of 69.72 Gb clean data, with each sample having approximately 7 Gb of clean data and a base percentage of 96% as Q30 or more. A summary of the clean reads data used in the subsequent analyses is given in Table S6. Several 98,788 unigenes’sequences were assembled with N50 of 2248 bp and an average length of 1575 bp (Table S7).

A total of 98,788 unigenes were annotated by matching to the NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (NR), SWISS-PROT, Translated EMBL nucleotide sequence data library (TrEMBL), The protein families database (Pfam), eukaryotic ortholog groups (KOG), Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and gene ontology (GO) databases (Table S8).The PCA and Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis revealed that the samples were alike in replicates, but sufficient variation existed among the three groups of samples. Almost 56% cumulative variation was covered by both PC1 (contributing 30.58% variation) and PC2 (contributing 25.42% variation), with three groups of samples lying distinctly apart from each other (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the replicates of three groups of samples showed high correlations among them but lower correlations among three groups (Fig. 3B). To obtain reliable DEGs, DESeq2/edgeR was utilized. A total of 20,262 up-regulated DEGs and 23,158 down-regulated DEGs were derived from the pairwise comparisons with Log2|Fold Change| >1 and P < 0.05 (Table S9; Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Multivariate statistical analysis of transcriptome data in taproot samples of three different stages. A PCA score plot. B Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient between 9 samples. C Volcano of genes with differences in relative abundance in different comparison groups. Red and green dots represent the numbers of genes with increases or decreases in relative abundance, respectively. D KEGG pathways enrichment of the top 20

The DEGs were further categorized and characterized according to their functional category as defined by the GO and KEGG databases. GO classification analysis revealed that the DEGs were mainly involved in “cellular process” and “metabolic process” in the “biological process” category (BP). In the “cellular component” category (CC), the DEGs were mostly involved in “cellular anatomical entity”. In the “molecular function” category (MF), “binding” and “catalytic activity” were predominant (Table S10 and Table S11). The enrichment analysis of KEGG indicated that the two metabolic pathways involved in “metabolic pathway” and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” were predominantly enriched (Fig. 3D).

As per the crucial role of transcription factors (TFs) in every biosynthetic, metabolic, cellular, and molecular function, we discovered 986 TFs between the 2- and 4-year-old groups (521 that were up-regulated and 465 that were down-regulated), 916 TFs between the 4- and 6-year-old groups (400 that were up-regulated and 516 that were down-regulated). It mainly included AP2/ERF-ERF, WRKY, bHLH, NAC, MYB-related, bZIP, C2H2, AUX/IAA, MYB (Table S12 and Table S13).

Differential expression of genes related to quinoline alkaloids biosynthesis pathway

Following differential genes expression analysis between 2- to 4-year-old samples, a total of 41 acetyltransferases were identified. By constructing phylogenetic trees of these 41 acetyltransferases and acridone synthase 2 (ACS2) [RUTGR], we further identified three critical enzymes capable of catalyzing the synthesis of 4-methoxy-2(1 H)-quinolinone (Fig. S1), including HAC1, NAGS1, NAGS2 (regulated by 4 genes). Furthermore, anthranilate as one of the key compounds that produced 4-methoxy-2(1 H)-quinolinone, three KEGG pathways were found involved in the biosynthesis of it by integrating current KEGG analysis. “Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis (ko00010)” started with α-D-gluecose-1-P, which was called central metabolic pathways as it was the one of key pathways to generate energy and intermediates for the synthesis of biomolecules. D-erythrose 4-P and phosphoenolpyruvate were generated through this pathway with 33 key enzymes (regulated by 219 genes from 2- to 4-year-old and 151 genes from 4- to 6-year-old) involved, including phosphoglucomutase, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and others. Then, followed by “Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis”, which initiated from D-Erythrose 4-P and Phosphoenolpyruvate and generated anthranilate through a series of catalysis by 23 key enzymes, including 3-deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase, 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase I and others (regulated by 87 genes from 2- to 4-year-old and 58 genes from 4- to 6-year-old). Furthermore, “Tryptophan metabolism (ko00380)” can also generate anthranilate by 16 key enzymes, including aromatic-L-amino-acid/L-tryptophan decarboxylase, aldehyde dehydrogenase and others (regulated by 77 genes from 2- to 4-year-old and 54 genes from 4- to 6-year-old). Subsequently, 4-methoxy-2(1 H)-quinolinone combined with dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) can generate 3-dimethyl allyl-2,4-dihydroxyquinolinone, then after a series of methylation, cyclization and oxidation, platydesmine was formed and followed by dictamnine. Based on dictamnine, many quinoline alkaloids like γ-fagarine, skimmianine, and others were generated. It was hypothesized that multiple key enzymes like methyltransferases, isomerases, CYP450s involved in the subsequent biosynthetic process of quinoline alkaloids, but none have been reported to date. In summary, a total of 459 genes involved in the regulation of quinoline alkaloids biosynthesis in D. dasycarpus. We performed SSR (simple sequence repeats) detection on genes using MISA (microsatellite identification tool) for the subsequent experimental validation. A total of 133 genes related to the quinoline alkaloids biosynthesis were kept (Table S14). Subsequent experiments will systematically screen for the key genes. Based on the partial KEGG pathways and identified enzymes that involved in the formation of quinoline alkaloids, the putative biosynthetic pathways were constructed and predicted when associated with its relevant metabolites (Fig. S2). For quinoline alkaloids, 4-methoxy-2 (1 H)-quinolinone was an important precursor that supported the biosynthesis of skimmianine, dictamnine and etc. It was predicted to undergo a series of cyclization, methylation and subsequent modifications mediated by some CYP450s, Cyclase and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs).

Differential expression of genes related to limonoids biosynthesis pathway

As a universal precursor of triterpenes, the biosynthesis of 2,3-oxidosqualene was related to two pathways within current KEGG analysis. The first was “Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (ko00900)”, including MVA(mevalonate) pathway and MEP (methylerythritol 4-phosphate) pathway. Catalyzed by a series of enzymes, isopentenyl-PP (IPP) and DMAPP were produced, then followed by geranyl-PP (GPP) and farnesyl-PP (FPP). Based on FPP, 2,3-oxidosqualene was formed in “Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis (ko00909)”. A total of 25 key enzymes (regulated by 62 genes from 2- to 4-year-old and 56 genes from 4- to 6-year-old) including mevalonate kinase, squalene monooxygenase and others were found in these two pathways. The key enzymes that complete the pathway to azadirone and kihadalactone were classified into CYPs, 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-ODDs), acetyltransferases and melianol oxide isomerases (MOIs). A total of 59 CYPs, 32 2-ODDs, 75 isomerases and 41 acetyltransferases were found in D. dasycarpus. In order to screen out the enzymes with the same function that complete the pathway from melian to kihadalactone A or azadirone, we chose the sequences of CYPs, 2-ODDs, acetyltransferases and MOIs from Citrus specific to construct phylogenetic trees (Fig. S3). It turned out that abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase 1 [Citrus sinensis], abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase 4 [Citrus clementina], abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase 4 [Citrus sinensis], abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase 3 [Citrus sinensis], 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone 23-monooxygenase CYP90D1 [Citrus sinensis] and CISIN_1g010899mg [Citrus sinensis] exhibited high homology with CsCYP716AC1 and CsCYP716AD2. CUMW_277890 [Citrus unshiu], beta-amyrin 11-oxidase[Citrus clementina], beta-amyrin 11-oxidase[Citrus clementina], Ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase 2 [Citrus sinensis], and CISIN_1g012524mg [Citrus sinensis] exhibited high homology with CsCYP88A37 and CsCYP88A51. CYP450 71A26 [Citrus sinensis], CYP450 71B35 [Citrus clementina], CYP450 71B35 [Citrus sinensis], CYP450 71A22 [Citrus clementina] and CYP450 71A1-like [Citrus sinensis] exhibited high homology with CsCYP71BE38, CsCYP71BQ4, CsCYP71D416 and CsCYP71CD1. Fe2OG dioxygenase domain-containing protein [Citrus sinensis], 2-oxoglutarate-Fe (II) type oxidoreductase hxnY-like isoform X2 [Citrus sinensis], gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase [Citrus clementina], gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase 1 [Citrus clementina] and gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase 2 [Citrus clementina] shared significant sequence identity with CsLFS. HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein [Citrus sinensis], BAHD acyltransferase At5g47980 [Citrus clementina] and vinorine synthase [Citrus clementina] exhibited high homology with CsL7AT, CsL1AT and CsL21AT. Cycloeucalenol cycloisomerase isoform X2 [Populus alba], 15-cis-zeta-carotene isomerase, partial [Citrus clementina], triosephosphate isomerase, chloroplastic [Citrus clementina], Triosephosphate isomerase, cytosolic [Cucurbita argyrosperma subsp. argyrosperma], Triosephosphate isomerase, cytosolic [Vitis vinifera], triosephosphate isomerase, cytosolic-like [Triticum aestivum] exhibited high homology with CsMOI1, CsMOI2 and CsMOI3.

All the key enzymes found in D. dasycarpus may play an important role in the completion of limonoids biosynthesis and regulated by a total of 95 genes. Kihadalactone A and azadirone were basic limonoid but the biosynthesis pathway to obacunone, dictamnusine, fraxinellonone and others was not clear. Based on the partial KEGG pathways and identified enzymes that involved in the formation of limonoids, the putative biosynthetic pathways were constructed and predicted when associated with its relevant metabolites (Fig. S4). Limonoids biosynthesis originated from the MVA pathway and MEP pathway, which was followed by the formation of melianone (Protolimonoid), azadirone or kihadalactone A (Basic limonoid) and nomilin (Intermediate). Subsequent oxidation, decarboxylation and degradation by CYP450s and UTGs were predicted to generate diverse limonoids, including obacunone, fraxinellone and etc.

In summary, a total of 200 genes involved in the regulation of limonoids biosynthesis in D. dasycarpus. We performed SSR detection on genes using MISA for the subsequent experimental validation. A total of 56 genes related to the limonoids biosynthesis in D. dasycarpus were kept (Table S15). Subsequent experiments will systematically screen for the key genes.

Integrated analysis of DAMs and DEGs

To identify the most important genes involved in the quinoline alkaloids and limonoids biosynthesis in D. dasycarpus taproots in three growth years, we integrated the metabolome and transcriptome data via correlation analysis. Correlation heatmaps were used to co-analyze 133 alkaloid-related genes and 56 limonoid-related genes with their corresponding differential secondary metabolites (Fig. 4A and B). Key genes were filtered under the thresholds of P < 0.05 and Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.8 (Table S16). It turned out that 79 key genes were highly correlated with quinoline alkaloids and 25 genes were highly correlated with limonoids.

Fig. 4.

Heatmap of Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient between DAMs and DEGs. A Limonoids and DEGs. B Quinoline alkaloids and DEGs. Red color indicates higher positive correlation coefficients, and green color indicates stronger negative correlation coefficients

Validation of key genes through RT-qPCR

To validate the reliability of the key genes, we randomly selected 10 alkaloid-related genes and 10 limonoid-related genes for quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. There was a good correlation between the transcriptomic data and the RT-qPCR results (Fig. 5), suggesting that the transcriptomic data was able to accurately reflect the transcriptional changes during the development of D. dasycarpus taproots and illustrated that the key genes related to quinoline alkaloids biosynthesis and limonoids biosynthesis were reliable.

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of candidate DEGs were assessed using RT-qPCR. Columns represent RT-qPCR results and lines represent RNA-Seq results. Left Y-axes indicate the relative mRNA expression levels of genes calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, while right Y-axes indicate the FPKM values. Data are means ± SD (n = 3)

Discussion

Primary metabolites, including carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids and proteins, are essential for life processes, and mainly provide material and energy for cell morphogenesis and physiological processes. In contrast, secondary metabolites are synthesized on the basis of primary metabolites and play an important role in the interaction between plants and their environments [25]. By correlating the growth performance, growth index, and morphological structure of taproots in 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old with total alkaloids and limonoids, it can be known that the increase in the diameter of the taproots and the thickening of the taproots of D. dasycarpus mainly occurs between the 2- and 4-year-old growth period. Moreover, the density of calcium oxalate clusters in the phloem parenchyma cells of the taproots is the highest in the 4-year-old D. dasycarpus, and the total alkaloids and limonoids increase significantly. Subsequent studies have found that the number of differential genes between the 4-year-old growth period and the 2-year-old growth period is the largest, and most of them are up-regulated genes related to the increase of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids. Therefore, it is speculated that the diameter of the taproots of D. dasycarpus and the density of calcium oxalate clusters in the phloem parenchyma cells are positively correlated with the accumulation of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids. The formation of starch granules is related to the growth length of the main root of D. dasycarpus and is possibly regulated by certain up-regulated genes. So, the 4-year-old growth period is the optimal harvesting period.

Quinoline alkaloids represent the predominant alkaloid type in D. dasycarpus. These compounds played a crucial role in the alkaloid accumulation process during 2- to 4-year-old samples, including dictamnine, preskimmianine, 4-methoxy-2 (1 H)-quinolinone, γ-fagarine, skimmianine, and others. 4-methoxy-2 (1 H)-quinolinone (Basic quinoline alkaloids) was recognized as a pivotal intermediate in the biosynthesis of quinoline alkaloids [26]. Biosynthesis of 4-methoxy-2 (1 H)-quinolinone was catalyzed by a type III polyketide synthase (PKS) from two key compounds including malonyl thioester and anthranilate [27]. In fact, the acridone synthase in Rutaceae plants was a plant-specific type III polyketide synthase [28]. ACS belonged to the transferase family, specifically the acyltransferase that transferred groups other than aminoacyl moieties. The currently identified ACS in Rutaceae plants was acridone synthase 2 (ACS2 [EC 2.3.1.159]) [29]. Limonoids, representing the second most abundant constituent class in D. dasycarpus, were highly oxidized tetracyclic triterpenoid secondary metabolites predominantly found in Rutaceae and Meliaceae species [30]. Numerous limonoids have been documented to possess diverse pharmacological activities, including antifeedant (insecticidal), anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, analgesic, anti-bacterial, and anti-viral responses [31,32]. To date, the complete biosynthetic pathway of limonoids from melian (Protolimonoid) to azadirone (Melia specific) and kihadalactone A (Citrus specific) has been systematically elucidated by De La Peña et al. [33]. According to the report by De La Peña et al., the most important enzymes from 2,3-oxidosqualene to melian was oxidosqualene cyclase (CsOSC1 from C. sinensis, AiOSC1 from A. indica, and MaOSC1 from M. azedarach) and two CYPs (CsCYP71CD1/MaCYP71CD2 and CsCYP71BQ4/MaCYP71BQ5).

The metabolome analysis revealed significant accumulation of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids in 2- and 4-year-old D. dasycarpus taproots. Some scholars [34] have systematically studied the variation patterns of the contents of dictamnine, obacunone, and fraxinellone in the root bark of D. dasycarpus aged 2 to 6 growth years by using the High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method. It turned out that 3 and 4 growth years are the periods of rapid growth for D. dasycarpus, but become relatively stable in the 5 and 6 growth years and the changes in contents of dictamnine, obacunone, and fraxinellone has no prominent correlation with growth years. In this study, we found that the main components that cause differential changes in biomass amony these were not obacunone but dictamnine, fraxinellone with high content. The accumulation of fraxinellone was probably caused by its potent insecticidal activity [35].

Among the transcriptome analysis, DEGs involved in the metabolic pathway and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites significantly enriched in 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old D. dasycarpus. At present, the quinoline alkaloid biosynthesis has not been fully reported. So, we sorted out and constructed the pathway to 4-methoxy-2(1 H)-quinolinone. We found that Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis; Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis; Tryptophan metabolism can finally generate anthranilate, and then catalyzed by HAC1, NAGS1, NAGS2 identified in D. dasycarpus to form 4-methoxy-2(1 H)-quinolinone. HAC1 was originally identified by reverse genetic approach in a population of Tnt1 retrotransposon-tagged mutants of the model legume Medicago truncatula [36]. Histone acetylation, a well-characterized posttranslational modification which is linked to transcriptional activation, has been proved to be involved in many cellular and physiological processes and is reversible and dynamically controlled by HAC1[37]. It was reported that HAC1 gene plays an essential role in root growth, cell differentiation in both legumes [38]. The role of NAGS1 and NAGS2 in plants remains unclear. CYPs, 2-ODDs, and acetyltransferases were key rate-limiting enzyme in the limonoids biosynthesis [39]. Some similar CYPs enzymes like abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase 1 [Citrus sinensis], 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone 23-monooxygenase CYP90D1 [Citrus sinensis], beta-amyrin 11-oxidase [Citrus clementina], CYP450 71A26 [Citrus sinensis] and others identified in D. dasycarpus functions as catalyzing the reversible redox reaction between aldehydes/ketones and alcohols, hydroxylation, decarboxylation, epoxidation and others [40], which play an important in the formation of secondary metabolites. limonoid furan synthase (LFS) is one of 2-ODDs which is implicated in furan ring formation. The partial 2-ODDs identified in D. dasycarpus were Fe2OG dioxygenase domain-containing protein [Citrus sinensis] and 2-oxoglutarate-Fe (II) type oxidoreductase hxnY-like isoform X2 [Citrus sinensis], which participate in various important metabolic pathways and directly affect the growth, development, and stress responses of plants [41]. HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein [Citrus sinensis], BAHD acyltransferase At5g47980 [Citrus clementina] were screen out in D. dasycarpus and function as CsL7AT, CsL1AT, CsL21AT. It was reported that they could catalyze acyl transfer reactions between CoA-activated hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives and hydroxylated aliphatics [42].

Conclusions

This study analyzed the significant differentially accumulated metabolites in D. dasycarpus taproots over the three growth years, and identified several genes encoding CYP450s, 2-ODDs, isomerases and acetyltransferases genes closely related to the accumulation of quinoline alkaloids and limonoids. These results provide a theoretical basis for the planting and harvesting of D. dasycarpus.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the Metware Biotechnology Inc (Wuhan, China) company for the transcriptomics analysis.

Abbreviations

- ACS

Acridone synthase

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- DAMs

Differentially accumulated secondary metabolites

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DMAPP

Dimethylallyl diphosphate

- FAA

Formalin-glacial acetic acid-alcohol

- FC

Fold change

- FDR

False discovery rates

- FPKM

Reads per kbper million reads

- FPP

Farnesyl-PP

- GO

Gene ontology

- GPP

Geranyl-PP

- HAC1

Histone acetyltransferase HAC1-like

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- IPP

Isopentenyl-PP

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- LFS

Limonoid furan synthase

- MISA

Microsatellite identification tool

- MOIs

Melianol oxide isomerases

- NAGS1

Amino-acid acetyltransferase NAGS1, chloroplastic isoform X2

- NAGS2

Amino-acid acetyltransferase NAGS2, chloroplastic isoform X4

- 2-ODDs

2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PKS

Polyketide synthase

- RT-qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- SBS

Sequencing by synthesis

- SD

Standard deviation

- UGTs

UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases

- VIP

Variable importance in projection

Authors’ contributions

Jiawei Mao designed the all research and contributed to writing the original draft preparation. Jianhan Liu and Yuying Hou contributed to handling the plants and performing morphological trait statistics. Xue Fang and Xueqi Cheng were responsible for the data analysis. Lei Tian was contributed to performing literature collection. Yue Ma was responsible for the LC-MS/MS. Haibo Yin collected the plants and identified. Xiaoxia Chen performed writing-review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central public welfare research institutes (NO. ZZ17-ND-10-03).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. The data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession number: PRJNA1191163.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: the authors identified an error in Affiliation 1.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/13/2025

The original online version of this article was revised: the authors identified an error in Affiliation 1.

Contributor Information

Haibo Yin, Email: yhb0528@sina.com.

Xiaoxia Chen, Email: 329768380@qq.com.

References

- 1.1. Iwamoto A, Asaoka M. Mechanical forces in plant growth and development. J Plant Res. 2024 Sep;137(5):695–696.

- 2.2. Jeandet P, Formela-Luboińska M, Labudda M, Morkunas I. The Role of Sugars in Plant Responses to Stress and Their Regulatory Function during Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 5;23(9):5161.

- 3.3. Liu S, Zhang Q, Kollie L, Dong J, Liang Z. Molecular networks of secondary metabolism accumulation in plants: current understanding and future challenges. Ind Crops Prod. 2023; 201:116901.

- 4.4. Abbas F, Ke Y, Yu R, Yue Y, Amanullah S, Jahangir MM, Fan Y. Volatile terpenoids: multiple functions, biosynthesis, modulation and manipulation by genetic engineering. Planta. 2017 Nov;246(5):803–816.

- 5.5. Khan RA, Abbas N. Role of epigenetic and post-translational modifications in anthocyanin biosynthesis: A review. Gene. 2023 Dec 15; 887:147694.

- 6.6. Azzeme AM, Azzreena, Kamarul Zaman M. Plant toxins: alkaloids and their toxicities. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2019;6(2):21 − 9.

- 7.7. Machado RA, Robert CA, Arce CC, Ferrieri AP, Xu S, Jimenez-Aleman GH, Baldwin IT, Erb M. Auxin Is Rapidly Induced by Herbivore Attack and Regulates a Subset of Systemic, Jasmonate-Dependent Defenses. Plant Physiol. 2016 Sep;172(1):521 − 32.

- 8.8. Liu J, Liu Y, Wang Y, Abozeid A, Zu YG, Tang ZH. The integration of GC-MS and LC-MS to assay the metabolomics profiling in Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius reveals a tissue- and species-specific connectivity of primary metabolites and ginsenosides accumulation. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017 Feb 20; 135:176–185.

- 9.9. Yamagishi M, Shimoyamada Y, Nakatsuka T, Masuda K. Two R2R3-MYB genes, homologs of Petunia AN2, regulate anthocyanin biosyntheses in flower Tepals, tepal spots and leaves of asiatic hybrid lily. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010 Mar;51(3):463 − 74.

- 10.10. Daloso DM, Morais EG, Oliveira E Silva KF, Williams TCR. Cell-type-specific metabolism in plants. Plant J. 2023 Jun;114(5):1093–1114.

- 11.11. Moco S, Capanoglu E, Tikunov Y, Bino RJ, Boyacioglu D, Hall RD, Vervoort J, De Vos RC. Tissue specialization at the metabolite level is perceived during the development of tomato fruit. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(15–16):4131-46.

- 12.12. Sharma D, Koul A, Kaul S, Dhar MK. Tissue-specific transcriptional regulation and metabolite accumulation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Protoplasma. 2020 Jul;257(4):1093–1108.

- 13.13. Shang XF, Morris-Natschke SL, Liu YQ, Li XH, Zhang JY, Lee KH. Biology of quinoline and quinazoline alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem Biol. 2022; 88:1–47.

- 14.14. Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China 2020 Edition [M] 2020 edition. One volume. Beijing: China Medical Science Press.2020:114–115.

- 15.15. Liu XY, Cheng LL, Sun.P. Research progress in chemical composition, pharmacological effects, toxicology of Dictamni Cortex and predictive analysis of its quality markers (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of New Drugs.2023, 32 (08): 799–805.

- 16.16. Qin Y, Quan HF, Zhou XR, Chen SJ, Xia WX, Li H, Huang HL, Fu XY, Dong L. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Dictamnus dasycarpus: a review. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2021 Dec 7;73(12):1571–1591.

- 17.17. Zheng H, Fu X, Shao J, Tang Y, Yu M, Li L, et al. Transcriptional regulatory network of high-value active ingredients in medicinal plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2023 Apr;28(4):429 − 46.

- 18.18. Li P, Shen T, Li L, et al. Optimization of the selection of suitable harvesting periods for medicinal plants: taking Dendrobium officinale as an example. Plant Methods. 2024; 20:43.

- 19.19. Liu Y, Li G, Sun Y, Wu J, Xu S, Pan J, et al. Chemical constituents from Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. and their chemotaxonomy value. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2025; 121:105014.

- 20.20. Liu Y, Cao D, Liang Y, Zhou H, Wang Y. Infrared spectral analysis and antioxidant activity of Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz with different growth years. J Mol Struct. 2021; 1229:129780.

- 21.21. Canene-Adams K. Preparation of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue for immunohistochemistry. Methods Enzymol. 2013; 533:225–33.

- 22.22. Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011; 29(7):644–52.

- 23.23. Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008; 5(7):621–28.

- 24.24. Liu S, Wang Z, Zhu R, Wang F, Cheng Y, Liu Y. Three Differential Expression Analysis Methods for RNA Sequencing: limma, EdgeR, DESeq2. J Vis Exp. 2021 Sep 18; (175).

- 25.25. Obata T. Metabolons in plant primary and secondary metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2019; 18(6):1483–1507.

- 26.26. Diaz G. Quinolines, isoquinolines, angustureine, and congeneric alkaloids—occurrence, chemistry, and biological activity. In: Rahman A, ed. Alkaloids. IntechOpen; 2015.10.5772/59819.

- 27.27. Abe I, Abe T, Wanibuchi K, Noguchi H. Enzymatic formation of quinolone alkaloids by a plant type III polyketide synthase. Org Lett. 2006 Dec 21;8(26):6063-5.

- 28.28. Junghanns KT, Kneusel RE, Baumert A, Maier W, Gröger D, Matern U. Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of acridone synthase from elicited Ruta graveolens L. cell suspension cultures. Plant Mol Biol. 1995 Feb;27(4):681 − 92.

- 29.29. Lukacin R, Schreiner S, Silber K, Matern U. Starter substrate specificities of wild-type and mutant polyketide synthases from Rutaceae. Phytochemistry. 2005 Feb;66(3):277 − 84.

- 30.30. Roy A, Saraf S. Limonoids: overview of significant bioactive triterpenes distributed in plants kingdom. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006 Feb;29(2):191–201.

- 31.31. Gualdani R, Cavalluzzi MM, Lentini G, Habtemariam S. The Chemistry and Pharmacology of Citrus Limonoids. Molecules. 2016 Nov 13;21(11):1530.

- 32.32. Roy A, Saraf S. Limonoids: overview of significant bioactive triterpenes distributed in plants kingdom. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006 Feb;29(2):191–201.

- 33.33. De La Peña R, Hodgson H, Liu JC, Stephenson MJ, Martin AC, Owen C, Harkess A, Leebens-Mack J, Jimenez LE, Osbourn A, Sattely ES. Complex scaffold remodeling in plant triterpene biosynthesis. Science. 2023 Jan 27;379(6630):361–368.

- 34.34. Shao C, Sun H, Zhang SN, Ma L, Li MJ, Zhang YY. Study on Dynamic Changes of Biomass and Effective Component Accumulation of Dictamnus dasycarpus in Different Growth Years. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 2023;34(5):1226–1228.

- 35.35. Bailly C, Vergoten G. Fraxinellone: from pesticidal control to cancer treatment. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2020; 168:104624.

- 36.36. Revaska M, Vassileva V, Goormachtig S, Van Hautegem T, Ratet P, Iantcheva A. Recent progress in development of a Tnt1 functional genomics platform for the model legumes Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus in Bulgaria. Curr Genet. 2011; 12:147 − 52.

- 37.37. Liang Z, Huang Y, Hao Y, Song X, Zhu T, Liu C, et al. The HISTONE ACETYLTRANSFERASE 1 interacts with CONSTANS to promote flowering in Arabidopsis. J Genet Genomics. 2025.

- 38.38. Boycheva I, Vassileva V, Revalska M, Zehirov G, Iantcheva A. Different functions of the histone acetyltransferase HAC1 gene traced in the model species Medicago truncatula, Lotus japonicus and Arabidopsis thaliana. Protoplasma. 2017 Mar;254(2):697–711.

- 39.39. Hodgson H, De La Peña R, Stephenson MJ, Thimmappa R, Vincent JL, Sattely ES, Osbourn A. Identification of key enzymes responsible for protolimonoid biosynthesis in plants: Opening the door to azadirachtin production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019 Aug 20;116(34):17096–17104.

- 40.40. Cheng Y, Liu H, Tong X, Liu Z, Zhang X, Li D, Jiang X, Yu X. Identification and analysis of CYP450 and UGT supergene family members from the transcriptome of Aralia elata (Miq.) seem reveal candidate genes for triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020 May 13;20(1):214.

- 41.41. Wei S, Zhang W, Fu R, Li J, Wang X, Zhao Y, et al. Genome-wide characterization of 2-oxoglutarate and Fe (II)-dependent dioxygenase family genes in tomato during growth cycle and their roles in metabolism. BMC Genomics. 2021; 22:126.

- 42.42. Molina I, Kosma D. Role of HXXXD-motif/BAHD acyltransferases in the biosynthesis of extracellular lipids. Plant Cell Rep. 2015 Apr;34(4):587–601

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. The data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession number: PRJNA1191163.