Abstract

A gastric juice-based PCR assay was compared with culture, microscopy, and a rapid urease test with specimens from 114 subjects. The PCR and conventional tests were positive for 76 and 62% of the subjects, respectively. The prevalence of gastroduodenal disease and seropositivity for anti-Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G were similarly high among conventional-test-positive and PCR-only-positive subjects compared to all-negative ones. The PCR assay is recommended to confirm the H. pylori status of culture-negative peptic-ulcer patients.

Helicobacter pylori, discovered by Warren and Marshall in 1983 (20, 21), is now known to be strongly associated with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer (1, 5, 8, 14). Treatment with antimicrobial agents was recommended for peptic ulcer patients with H. pylori infection by a National Institutes of Health consensus panel in 1994 (14) and has gained general acceptance by gastroenterologists worldwide. However, diagnosing H. pylori infection is sometimes difficult.

Traditionally, culturing the pathogen is considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. However, diagnosing H. pylori infection by culture alone may have certain limitations. Most importantly, there are possible false negatives due to sampling error because the culture, using biopsy specimens, can assess infection only at the biopsy sites (14). Microscopic examination and the rapid urease test can be highly specific if strictly performed, but they are based on biopsy specimens and thus are theoretically prone to sampling error, as in the case of culture.

The urea breath test, now recognized as a sensitive diagnostic procedure, measures urease activity in the entire stomach and is presumably except from sampling error (7, 13). However, the urea breath test sometimes becomes apparently positive in culture-negative patients (4, 18). Since the presence of urease activity is not direct proof of the presence of H. pylori, these cases may be determined to be false positives as long as the culture is used as the gold standard.

Sensitive PCR assays using biopsy specimens have been reported (2, 6, 17, 19), but the sensitivities of previous PCR assays on gastric juice were at most comparable to culture (12, 17, 19, 22). However, we have established a seminested PCR assay, designated as URA-PCR, targeting the well-conserved regions in the ureA gene of H. pylori (11). The URA-PCR surpassed previous PCR assays in sensitivity (2, 9, 11), and gastric juice samples were applicable for the URA-PCR assay, thereby avoiding sampling error.

Like the urea breath test, the URA-PCR assay sometimes yields positive results for culture-negative patients. Unlike the urea breath test, however, positive PCR amplification of H. pylori-specific DNA may be considered as direct evidence of the presence of the pathogen. In the present study, we compared the PCR assay with conventional biopsy-based tests for 114 consecutive patients, putting emphasis on the analysis of cases with discrepancies. In addition, we used disposable capsuled strings (15) to collect gastric juice. The primary purpose of using this device was to avoid contamination, but this simple and less invasive procedure may be clinically valuable for obtaining gastric juice samples without repeating endoscopy.

Subjects.

One hundred and fourteen consecutive Mito Saiseikai Hospital patients (71 male, 43 female; mean age, 49 years; range, 23 to 73 years) for which gastroduodenal endoscopy was indicated were enrolled in this study. None had received antimicrobial therapy against H. pylori before, nor had any of them been subjected to long-term administration of any antibiotic in the previous year. Patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were excluded. The ethical committee of the hospital approved the protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Gastric juice samples.

Gastric juice samples were obtained by use of capsuled nylon strings [Entero-Test; HDC Corp., San Jose, Calif.] after the patients had fasted overnight. For this device, a highly absorbent nylon string (140 cm) was packed inside a gelatin capsule (8 by 23 mm). Subjects were instructed to swallow a capsule with water, with the free end of the string secured outside the mouth. Once inside the stomach, the capsule dissolves and the string avidly absorbs gastric juice. The string is left in place for 30 min and then withdrawn through the mouth. About 0.5 ml of gastric juice is absorbed by 10 cm of the string, an amount which is sufficient for the PCR assay described below.

PCR amplification of H. pylori DNA.

We designed novel primers for the URA-PCR assay by targeting the ureA gene of H. pylori because this gene is unique to this pathogen. Since diversity of the nucleotide sequence of the ureA gene exists, we analyzed nucleotide conservation among clinical isolates by full-length sequencing of the gene and by using selected PCR primers that targeted well-conserved regions.

Three primers, A-2F2 (nucleotides 2783 to 2804; 5′ATATTATGGAAGAAGCGAGAGC3′), A-2F3 (nucleotides 2893 to 2912; 5′CATGAAGTGGGTATTGAAGC3′), and A-2R (nucleotides 3096 to 3076; 5′ATGGAAGTGTGAGCCGATTTG3′), were selected for use in the URA-PCR; the initial amplification was performed with primers A-2F2 and A-2R, and the internal amplification was performed with primers A-2F3 and A-2R. Details of the procedure were described previously (11). DNA samples extracted from 38 bacterial species other than H. pylori (including H. cinaedi, H. fennelliae, and H. pametensis) were not amplified by the PCR assay.

Endoscopic examination.

After the gastric juice sampling described above was completed, gastroduodenal endoscopies were performed with endoscopes which had been thoroughly washed in an automatic endoscope cleaner (16). Endoscopic diagnoses were made by one of the authors (K.H.), without information on the results of H. pylori assays (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic data and endoscopic findings on 114 subjects

| Endoscopic diagnosis | n | Male/female ratio | Age (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric ulcer | 22 | 16/6 | 52 ± 11 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 35 | 25/10 | 48 ± 11 |

| Chronic gastritis | 26 | 16/10 | 53 ± 11 |

| Normal mucosa | 31 | 14/17 | 46 ± 12 |

| Total | 114 | 71/43 | 49 ± 12 |

Biopsy-based tests.

Two gastric biopsy specimens each were obtained from the gastric antrum and corpus on the greater curvature. One specimen was immediately placed in transfer medium and then cultured on blood agar medium in a microaerophilic environment (Campy Pouch; Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.). Positive cultures were confirmed by determination of urease, catalase, and oxidase activities. The other specimen was smeared on a glass, gram stained, microscopically examined for the presence of gram-negative bacilli, and then used for the rapid urease test (CLO test; Delta West, Bentley, Western Australia) with a 2-h incubation at 37°C. These biopsy-based tests were considered positive if at least one specimen, obtained from either the antrum or corpus, had a positive result.

Serum anti-H. pylori IgG.

At the time he or she entered the study, each subject was tested for serum anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) by use of the Pilicaplate G Helicobacter enzyme immunoassay kit (Biomerica, Newport Beach, Calif.). The assay was determined positive if the increase in the optical density at 405 nm exceeded that of a 1:16 dilution of the serum standard contained in the kit.

Antimicrobial therapy.

Five randomly selected subjects who were negative for H. pylori by any biopsy-based test (culture, microscopy, or the rapid urease test) but positive by the PCR assay were treated with amoxicillin (500 mg three times a day orally [p.o.]) and lansoprazole (30 mg once daily p.o.) for 14 days. Another four subjects who were positive by both the biopsy-based tests and the PCR assay were similarly treated. Gastric juice samples were collected with the capsuled string, as described above, at the cessation of therapy and 2 and 4 weeks later, and H. pylori DNA was assessed by the PCR assay.

Statistical analyses.

Student’s t test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact probability test were used when applicable, and a difference with a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The gastric juice-based URA-PCR assay (Fig. 1) was positive for 87 (76%) subjects, whereas the biopsy-based tests, i.e., culture, microscopy, and the rapid urease test, were positive for only 65 (57%), 66 (58%), and 70 (61%) subjects, respectively (Table 2). At least one of the three biopsy-based tests was positive for 71 (62%) subjects, and these subjects were designated as biopsy positives in the following text.

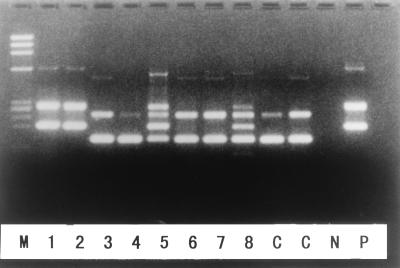

FIG. 1.

PCR amplification of the H. pylori ureA gene. Samples 1, 2, 5, and 8 were positive for ureA, and samples 3, 4, 6, and 7 were negative for ureA. P, positive control showing the first and second PCR products; N, negative control; C, controls with artificial templates yielding amplicons with different lengths; M, molecular size markers.

TABLE 2.

Detection of H. pylori infection in 114 subjects by PCR and conventional biopsy-based tests

| Method of detection | No. (%) positive with endoscopic diagnosis of:

|

Total (n = 114) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcers (n = 57) | Chronic gastritis (n = 26) | Normal mucosa (n = 31) | ||

| Gastric juice-based URA-PCR | 54 (95) | 24 (92) | 9 (29) | 87 (76) |

| Conventional biopsy based | ||||

| Culture | 43 (75)a | 15 (58)a | 7 (23) | 65 (57) |

| Microscopy | 44 (77)a | 16 (62)a | 6 (19) | 66 (58) |

| Rapid urease test | 45 (79)a | 18 (69) | 7 (23) | 70 (61) |

| Combinedb | 46 (81)a | 18 (69) | 7 (23) | 71 (62) |

Detection rate significantly differed from that of URA-PCR by chi-square test.

At least one of the biopsy-based tests (culture, microscopy, or the rapid urease test) was positive.

The detection rate of H. pylori infection, as determined by each assay, was higher in subjects with peptic ulcers or chronic gastritis than in subjects with normal gastric mucosae (Table 2). However, for subjects with peptic ulcers and chronic gastritis, the detection rate by the PCR assay was significantly higher than that by biopsy-based tests. These data indicated that a significant portion of subjects with positive endoscopic findings were biopsy negative but PCR positive. It was crucial to determine whether they had actual H. pylori infections because antimicrobial therapy might be indicated if they did harbor infection.

Results were further analyzed by dividing subjects into four categories: PCR positive and biopsy positive (n = 69; 61%), PCR positive and biopsy negative (n = 18; 16%), PCR negative and biopsy positive (n = 2; 2%), and all negative (n = 25; 22%) (Table 3). The biopsy-negative but PCR-positive group constituted the major concern in the current study.

TABLE 3.

Correlation between PCR and biopsy-based test results, endoscopic findings, and presence of anti-H. pylori antibodies in serum for 114 subjectsa

| Subject groupb | No. of subjects with endoscopic diagnosis of:

|

No. of subjects with serological test result of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcers | Chronic gastritis | Normal mucosa | Positive | Negative | |

| PCR+, BBT+ (n = 69) | 45 | 17 | 7 | 69 | 0 |

| PCR+, BBT− (n = 18) | 9 | 7 | 2 | 17 | 1 |

| PCR−, BBT+ (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| PCR−, BBT− (n = 25) | 2 | 1 | 22 | 7 | 18 |

Subjects were divided into four groups on the basis of assay results, and endoscopic findings and seropositivity for anti-H. pylori IgG were compared among them. The biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects were similar to the biopsy-positive subjects and distinct from all-negative ones in these respects.

BBT, biopsy-based test; +, positive; −, negative.

We first analyzed the distribution of endoscopic findings among the four categories. The majority of PCR-positive subjects had peptic ulcers or chronic gastritis irrespective of the results of biopsy-based tests: 62 (90%) of 69 biopsy-positive, PCR-positive subjects and 16 (89%) of 18 biopsy-negative, PCR-positive subjects had either peptic ulcers or chronic gastritis. In contrast, only 3 (12%) of 25 all-negative subjects had peptic ulcers or chronic gastritis. The rate of positive endoscopic findings was significantly lower in the all-negative group than in the biopsy-negative but PCR-positive group (P < 0.0001).

We then analyzed the rates of serum anti-H. pylori IgG positivity among the categories (Table 3). The seropositivity was similarly high in the biopsy-positive, PCR-positive group (69 of 69 [100%]) and in the biopsy-negative, PCR-positive group (17 of 18 [94%]) but was significantly lower in the all-negative group (7 of 25 [28%]). Thus, the biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects were similar to biopsy-positive subjects and different from all-negative subjects serologically as well as endoscopically. It should be mentioned, however, that 7 (25%) of the 25 subjects who were negative by both the PCR and biopsy-based tests were seropositive. We do not know whether these cases represent past (cured) infection, ongoing infection undetected by any other test, or falsely detected antibodies.

To further prove that the biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects harbored ongoing H. pylori infections, we randomly selected five of them and treated them after obtaining informed consent. The URA-PCR assay was performed on sequentially sampled gastric juice. The PCR assay was negative for all subjects at the completion of antibiotic administration, and it remained negative for four of them but became positive afterward for one (Table 4). These data strongly suggest that the PCR assay reflected the clearance and the eradication (or its failure) of H. pylori in the biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects, as it did in the biopsy-positive ones (Table 4). The data also indicated that H. pylori that had been rendered nonviable by antibiotics had been washed away from the stomach and did not affect the PCR assay by day 14 of the treatment.

TABLE 4.

Results of sequential PCR assay performed after antimicrobial therapy on randomly selected subjects positive only by PCR and in subjects positive also by biopsy-based testsa

| Subject’s age | Subject’s sex | Endoscopic diagnosisb | Result of culture performed before therapyc | Result of URA-PCR on gastric juice performedc:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before therapy | After therapy at week:

|

||||||

| 0 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| 48 | Male | DU | − | + | − | − | − |

| 67 | Male | DU | − | + | − | + | + |

| 43 | Male | GU | − | + | − | − | − |

| 71 | Male | GU | − | + | − | − | − |

| 57 | Male | CG | − | + | − | − | − |

| 57 | Male | DU | + | + | − | + | + |

| 59 | Male | DU | + | + | − | − | − |

| 42 | Male | GU | + | + | − | − | − |

| 59 | Male | GU | + | + | − | + | + |

Five biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects and four culture-positive subjects were randomly selected and treated with amoxicillin 500 mg three times per day and lansoprazole 30 mg once daily for 14 days. The URA-PCR assay performed at the cessation of treatment was negative in all cases, similarly reflecting the response to therapy in both groups.

DU, duodenal ulcers; GU, gastric ulcers; CG, chronic gastritis.

−, negative for H. pylori; +, positive for H. pylori.

Instead of selecting one modality as the gold standard, we analyzed characteristics of subjects in relation to the results of assays and demonstrated that the biopsy-negative but PCR-positive subjects were similar to the biopsy-positive subjects in terms of endoscopic findings and the seropositivity of anti-H. pylori IgG and were significantly different from the biopsy- and PCR-negative ones. Although the presence of gastroduodenal disease or serum antibodies is not direct evidence of ongoing H. pylori infection, the most probable explanation is that the PCR assay detected H. pylori infections that were not detected by culture or biopsy-based tests.

The results of three biopsy-based tests (culture, microscopy, and the rapid urease test) agreed in most cases: all were negative in 43 (38%) cases (the PCR was positive in 18 of them), and all were positive in 62 (54%) cases. Thus, sampling error caused by obtaining biopsies only at uninfected sites seems to be responsible for false negatives in biopsy-based tests. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia associated with H. pylori infection progress with age (10), reducing the habitable gastric surface for H. pylori (3). Thus, older patients may be more liable to have false-negative results due to sampling error. In fact, the biopsy-negative, PCR-positive subjects in the current study were significantly older than the biopsy-positive ones (54 ± 11 years versus 49 ± 11 years; P < 0.05). This line of reasoning would suggest that the sensitivity of biopsy-based tests might be improved by obtaining more specimens from various sites in the stomach. However, an increase in the number of biopsy sites would be accompanied by higher costs and a longer duration of endoscopic examination, and the number of available biopsy specimens is practically limited.

Perez-Trallero and colleagues obtained gastric juice with the capsuled string and used it for culture (15). However, we have found that cultures using gastric juice obtained in this manner are sometimes affected by contaminating bacteria (unpublished observation). At present, the susceptibility of H. pylori to individual antibiotics can be assessed only by culturing biopsy specimens. In addition, diseases such as gastric cancer are sometimes revealed unexpectedly by gastroduodenal endoscopy. We thus recommend that gastroduodenal endoscopy be performed initially in the screening of patients. However, we also recommend the additional use of the URA-PCR assay for the confirmation of H. pylori status, especially for culture-negative patients with peptic ulcers or chronic gastritis. Gastric juice samples aspirated through the endoscope and stored frozen can be used afterward for the PCR assay (data not shown). Alternatively, gastric juice samples can be obtained with the capsuled string without repeating the endoscopy procedure. The assessment of the outcome of antimicrobial therapy may be another clinical application of the PCR assay. With the use of the string, endoscopy need not be repeated. This possibility is now under investigation, and preliminary data indicate that the PCR assay is at least as sensitive as the urea breath test for monitoring relapses after therapy. A commercially available kit for H. pylori detection based on the URA-PCR assay is now being prepared (SRL Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

In conclusion, 18 (16%) of 114 subjects were negative for H. pylori by culture, microscopy, and the rapid urease test but positive by the URA-PCR assay. These subjects were similar to culture-positive subjects and distinct from all-negative subjects both endoscopically and serologically, and they should be regarded as having ongoing infections. Nine (16%) of 57 ulcer patients belonged in this category and would have benefited from antimicrobial therapy. The use of the URA-PCR assay is also recommended to confirm the H. pylori status of patients who are negative for H. pylori by conventional biopsy-based tests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for General Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaser M J, Chyou P H, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55:562–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton C L, Kleanthous H, Coates P J, Morgan D D, Tabaqchali S. Sensitive detection of Helicobacter pylori by using polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:192–200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.192-200.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craanen M E, Blok P, Dekker W, Tytgat G N J. Subtypes of intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1992;33:597–600. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler A F, Havstad S, Ma C K, Blaser M J, Perez-Perez G I, Schubert T T. Accuracy of invasive and noninvasive tests to diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EUROGAST Study Group. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:1359–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabre R, Sobhani I, Laurent-Puig P, Hedef N, Yazigi N, Vissuzaine C, Rodde I, Potet F, Mignon M, Etienne J P, Braquet M. Polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsy specimens: comparison with culture, rapid urease test, and histopathological tests. Gut. 1994;35:905–908. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.7.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham D Y, Klein P D, Evans D J, Jr, Evans D G, Alpert L C, Opekun A R, Boutton T W. Campylobacter pylori detected noninvasively by the 13C-urea breath test. Lancet. 1987;i:1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson L E, Engstrand L, Nyren O, Evans D J, Jr, Lindgren A, Bergstrom R, Andersson B, Athlin L, Bendtsen O, Tracz P. Helicobacter pylori infection: independent risk indicator of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1098–1103. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90954-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho S-A, Hoyle J A, Lewis F A, Secker A D, Cross D, Mapstone N P, Dixon M F, Wyatt J I, Tompkins D S, Taylor G R, Quirke P. Direct polymerase chain reaction test for detection of Helicobacter pylori in humans and animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2543–2549. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2543-2549.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katelaris P H, Seow F, Lin B P C, Napoli J, Ngu M C, Jones D B. Effects of age, Helicobacter pylori infection, and gastritis with atrophy on serum gastrin and gastric acid secretion in healthy men. Gut. 1993;34:1032–1037. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawamata O, Yoshida H, Hirota K, Yoshida A, Kawaguchi R, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Nested-polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection with novel primers designed by sequence analysis of urease A gene in clinically isolated bacterial strains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:266–272. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mapstone N P, Lynch D A, Lewis F A, Axon A T, Tompkins D S, Dixon M F, Quirke P. Identification of Helicobacter pylori DNA in the mouths and stomachs of patients with gastritis using PCR. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:540–543. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.6.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall B J, Surveyor I. Carbon-14-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Campylobacter pylori-associated gastritis. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Helicobacter pylori in peptic diseases. JAMA. 1994;272:65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Trallero E, Montes M, Alcorta M, Zubillaga P, Telleria E. Non-endoscopic method to obtain Helicobacter pylori for culture. Lancet. 1995;345:622–623. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roosendaal R, Kuipers E J, van den Brule A J C, Peña A S, Uyterlinde A M, Walboomers J M M, Meuwissen S G M, de Graaff J. Importance of the fiberoptic endoscopic cleaning procedure for detection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsy specimens by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1123–1126. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1123-1126.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada T, Ogura K, Ota S, Terano A, Takahashi M, Hamada E, Omata M, Sumino S, Sasa R. Identification of Helicobacter pylori in gastric specimens, gastric juice, saliva, and faeces of Japanese patients. Lancet. 1994;343:1636–1637. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thijs J C, van Zwet A A, Thijs W J, Oey H B, Karrenbeld A, Stellaard F, Luijt D S, Meyer B C, Kleibeuker J H. Diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori: a prospective evaluation of their accuracy, without selecting a single test as the gold standard. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2125–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valentine J L, Arthur R R, Mobley H L T, Dick J D. Detection of Helicobacter pylori by using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:689–695. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.4.689-695.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren J R, Marshall B J. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;i:1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren J R, Marshall B J. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;i:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westblom T U, Phadnis S, Yang P, Czinn S J. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection by means of a polymerase chain reaction assay for gastric juice aspirates. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:367–371. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]