Abstract

Background and objectives

Anxiety is closely associated with sleep hygiene among college students; however, its underlying mechanisms require further investigation. This study aimed to construct a moderated mediation model, in which subjective well-being serves as the mediator and physical activity as the moderator, to examine how subjective well-being mediates the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene under different levels of physical activity. This model seeks to deepen the understanding of this psychological mechanism and provide a theoretical basis for improving sleep hygiene in college populations.

Methods

Using convenience sampling, a self-reported questionnaire Survey was conducted in 2024 with 3,007 college students (1,267 males and 1,740 females; mean age = 19.03 ± 1.18 years). The study adopted a cross-sectional design and measured four core variables: anxiety, subjective well-being, sleep hygiene, and physical activity. Pearson correlation coefficients were first calculated to assess the relationships among the variables. Mediation and moderated mediation effects were then tested using the PROCESS macro in SPSS.

Results

The results indicated that anxiety significantly and negatively predicted sleep hygiene (β = -0.241, p < 0.001), and this effect remained significant after including the mediating variable. Specifically, anxiety significantly and negatively predicted subjective well-being (β = -0.368, p < 0.001), while subjective well-being significantly and positively predicted sleep hygiene (β = 0.262, p < 0.001), suggesting that higher levels of subjective well-being contribute to better sleep hygiene. Furthermore, physical activity significantly moderated the effects of both anxiety on subjective well-being and subjective well-being on sleep hygiene, exhibiting a positive regulatory role.

Conclusion

This study further elucidates the potential mechanisms through which anxiety affects sleep hygiene among college students. Physical activity serves a buffering role in the relationship among anxiety, subjective well-being, and sleep hygiene. These findings offer a novel perspective for intervention strategies aimed at improving sleep hygiene and provide theoretical support for the integrated management of mental health and health-related behaviors in university populations.

Keywords: College students, Anxiety, Subjective well-being, Physical activity, Sleep hygiene

Background

Sleep hygiene is generally defined as a collection of behavioral practices and environmental conditions that support efficient and sustained sleep. Core components include maintaining a regular sleep-wake schedule (such as setting fixed times for going to bed and waking up), aligning time spent in bed with individual sleep needs, and avoiding the consumption of substances that stimulate the central nervous system before bedtime. Additionally, moderate physical activity, a balanced diet, and a sleep environment that is dark, quiet, and cool all contribute to improved sleep quality by minimizing factors that interfere with the sleep process [1]. According to the National Sleep Foundation, adults aged 18 to 64 are recommended to obtain 7 to 9 h of sleep per night [2]. However, studies have shown that the prevalence of sleep disorders among college students can be as high as 55.64%, and 33.32% exhibit signs of excessive daytime sleepiness, indicating a widespread problem of poor sleep hygiene in this population [3]. A meta-analysis conducted in China further reported that 8.4% and 43.9% of college students sleep less than 6 and 7 h per night, respectively, and 19.5% are habitual night owls [4, 5]. In addition to irregular routines, the frequent use of electronic devices before bedtime is common. Surveys show that 72.9% of students use mobile phones for more than one hour before sleeping. Such inappropriate smartphone use weakens the psychological association between bed and sleep, and the emitted blue light suppresses melatonin secretion, thereby delaying sleep onset and reducing the proportion of deep sleep [6]. Moreover, unhealthy behaviors among college students should not be overlooked. The prevalence of behaviors Such as smoking and physical inactivity ranges from 5.0 to 88.5% [7]. The weighted prevalence of current or past nicotine use is 47%, and approximately 35% of these individuals report insufficient sleep [8]. Stimulants like caffeine and nicotine are frequently used by college students, particularly during nighttime hours, and are more likely to induce neural excitation, prolong sleep latency, and disrupt sleep maintenance [9]. At the same time, psychological factors play a significant role. Research indicates that the global prevalence of anxiety symptoms among college students is approximately 39%. Emotional instability and excessive rumination before bedtime frequently activate the physiological arousal system, which interferes with sleep initiation [10]. Notably, studies from the United States reveal that nearly half of college students report engaging in binge drinking, and such problematic alcohol use is common in this group. Although alcohol may induce short-term drowsiness, its disruptive effects on sleep architecture are associated with increased sleep disturbances and lower sleep quality [11]. Inadequate or suboptimal sleep hygiene encompasses all factors that lead to arousal or disturb the normal regulation of the sleep–wake cycle [12]. These practices may result in poor sleep quality or unhealthy sleep patterns, which have been significantly associated with a range of health problems, including depression, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and an increased risk of obesity and other chronic conditions. Taken together, current evidence suggests that healthy sleep hygiene practices play a crucial role in maintaining the physical well-being of college students and serve as an essential foundation for early interventions and behavioral correction.

In the context of a rapidly changing social environment and increasing academic competition, college students are exposed to multiple sources of psychological stress, making anxiety one of the most prevalent mental health concerns in this population. When confronted with external stressors or internal conflicts, individuals often experience varying degrees of emotional fluctuations, among which anxiety is a common form of negative emotional response [13]. Anxiety may occur at any age, and occasional episodes are relatively common in daily life. However, when it presents as intense, persistent, and difficult-to-control fear and worry, it may develop into an anxiety disorder of clinical significance [14]. Anxiety is typically characterized by non-specificity, persistence, and negativity. It involves an excessive anticipation of unpredictable or unavoidable threats, and is often accompanied by physiological and psychological symptoms such as muscle tension, heightened vigilance, and physiological arousal [15]. A meta-analysis incorporating 83 studies and approximately 130,090 students worldwide reported a prevalence rate of anxiety among college students as high as 39.65% [16]. In China, Survey data show that the detection rate of anxiety among college students is also high, reaching 18.2%, reflecting a substantial mental health burden [17]. This emotional response is frequently observed in the daily lives of students and is typically marked by excessive worry about uncontrollable future events, accompanied by physical symptoms such as muscle tension, rapid heartbeat, sweating, and heightened alertness [18, 19]. When such responses become intense, sustained, and difficult to regulate both mentally and physically, they may evolve into clinically significant anxiety disorders [20]. Anxiety not only disrupts emotional well-being but also triggers a series of adverse effects across cognitive, behavioral, and physiological domains [21–26]. Cognitively, anxiety can impair attention, reduce memory capacity, and hinder information processing efficiency, thereby affecting academic performance and decision-making [27, 28]. Behaviorally, it may lead to social avoidance and academic withdrawal [29]. Physiologically, anxiety has been linked to gastrointestinal dysfunction, heightened cardiovascular responses, and suppression of the immune system, which collectively undermine overall health [30]. More importantly, anxiety and sleep disorders often co-occur at high rates [31]. Studies have shown that anxious individuals commonly experience severe rumination and nightmares, and these persistent states of mental arousal and excessive thinking interfere with both sleep initiation and maintenance, leading to difficulties falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, and reduced sleep quality [32, 33]. Furthermore, anxiety can lead to various unhealthy sleep hygiene behaviors, such as sleep procrastination, prolonged use of electronic devices before bedtime, reliance on alcohol or medication to fall asleep, excessive daytime napping, binge eating before bed, engaging in non-sleep-related activities in bed, cannabis use, and irregular sleep–wake patterns [34–37]. On a physiological level, anxiety may further disrupt sleep architecture by suppressing melatonin secretion and activating the sympathetic nervous system [38]. Of particular concern, the Arousal Regulation Model of Affective Disorders suggests that chronic hyperarousal induced by anxiety not only impairs sleep initiation but may also lower the threshold for impulse control, thereby increasing the likelihood of self-injurious behaviors [39, 40]. When anxiety coexists with feelings of helplessness and loneliness, the risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts may also increase [41]. Based on this review, the present study hypothesizes that anxiety is significantly negatively associated with sleep hygiene among college students (H1).

In the context of college students’ mental health and life satisfaction, Subjective Well-Being is commonly regarded as a core psychological indicator and a central focus of research. Subjective well-being refers to individuals’ experiences and evaluations of their overall life, as well as specific life domains or daily activities [42]. It comprises multiple interrelated dimensions that are not entirely independent but rather overlap in function and content. From a measurement perspective, subjective well-being is conceptualized as a continuum: at one end, it emphasizes momentary assessments of emotional states, feelings, or experiences—often reflecting short-term affective responses—while at the other, it involves more integrative judgments of life satisfaction, goal fulfillment, or subjective distress, typically over extended periods or without specific temporal boundaries [43]. Recent survey research indicates a global downward trend in subjective well-being among college students. Poor health conditions not only disrupt academic and daily functioning but also significantly diminish students’ levels of subjective well-being and life satisfaction [44]. Concurrently, the incidence of mental disorders in this group continues to rise. Global data show that the comorbid prevalence of depression and anxiety among college students has reached 33.6% and 39.0%, respectively, reflecting widespread psychological challenges [10, 45]. A study conducted among Chinese college students assessed overall Health from physical, psychological, and social perspectives, revealing average scores of only 65.03, 66.25, and 66.53 out of 100 across these dimensions—suggesting below-average well-being [46]. In the United States, over half of undergraduate students reported experiencing at least one health problem in the past year, and self-rated health status was generally poor, further underscoring the global prevalence and severity of health issues in this population [47]. Previous studies have shown that subjective well-being is not only closely associated with general health status but also significantly linked to specific physiological indicators and health-related behaviors [48, 49]. Low levels of subjective well-being are often accompanied by frequent negative emotions, which may lead to various adverse health outcomes, including weakened immune function, cardiovascular dysregulation, and endocrine imbalances [50]. Research also suggests that subjective well-being is associated with fluctuations in hormonal levels such as cortisol, norepinephrine, and insulin. Emotional instability can influence next-day glucose levels, endocrine responses, and the coordination of neuroimmune systems [51]. On a behavioral level, individuals with lower subjective well-being are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as physical inactivity, poor dietary habits, smoking, and disordered sleep, which may further burden the body and increase the risk of chronic diseases [52, 53]. Among these influencing factors, anxiety is considered one of the most significant predictors of diminished subjective well-being. On one hand, anxiety may weaken positive affect, intensify negative emotions, and impair cognitive function and behavioral regulation, thereby reducing life satisfaction and subjective happiness [54]. On the other hand, anxiety may contribute to failed stress coping and social withdrawal, indirectly undermining social support and daily functioning, which in turn diminishes subjective well-being and triggers unhealthy sleep hygiene behaviors [55]. Moreover, negative emotional states such as anxiety, depression, and chronic stress have been shown to upregulate inflammatory markers, delay wound healing, disrupt the regulation of telomeres and telomerase, accelerate cellular aging, and alter metabolic function [56]. It is particularly important to note that prolonged anxiety, if left unaddressed, may exacerbate psychological crises and increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation or self-harming behavior [57]. Taken together, this study proposes that subjective well-being mediates the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene (H2).

To more fully capture the dynamic, complex, and emotional dimensions of physical activity, it has been conceptualized as a process of movement, action, and performance that occurs within specific cultural and spatial contexts. Its manifestations are influenced by a range of individual factors, including interests, emotions, cognition, motivation, and interpersonal relationships [58]. In recent years, physical activity has been increasingly recognized not only as a vital means of promoting physical health, but also as a key contributor to mental well-being and enhanced subjective well-being [59]. Many national governments have implemented policies aimed at increasing public awareness and participation in physical activity. For example, in 2023, the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) released a new strategy aimed at engaging 2.5 million adults and 1 million Children in regular physical activity by 2030 [60]. In China, the “Healthy China 2030” Planning Outline was issued as early as 2016, highlighting nationwide fitness as a strategic pathway to improving public Health. Further, in 2021, the National Fitness Program (2021–2025) was launched to address regional disparities and insufficient public service capacity in fitness infrastructure [61, 62]. In the United States, the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans promote evidence-based exercise recommendations for various populations and encourage the integration of physical activity into daily life [63]. Empirical studies have demonstrated the significant impact of physical activity on subjective well-being. On the physiological level, regular exercise helps improve physical fitness, enhance immune function, and prevent obesity and chronic disease, thereby promoting bodily health and vitality [64]. On the psychological level, exercise reduces symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, stimulates positive emotions, and improves self-efficacy and psychological resilience, contributing to enhanced emotional well-being [65–69]. On the behavioral level, physical activity is often associated with healthy dietary habits, regular routines, and stable circadian rhythms, thereby increasing life satisfaction and the sense of personal control [70]. On the social level, group-based physical activities promote interpersonal interaction, a sense of social belonging, and improved social support and adaptability [71]. It is worth noting that college students—being in a key stage of psychological and physical development—are particularly sensitive to emotional resonance during physical activity and are more likely to experience a heightened sense of happiness and emotional fulfillment through such participation [72]. Beyond its role in enhancing subjective well-being physical activity also serves as a regulatory mechanism for sleep hygiene. Empirical evidence suggests that regular moderate-intensity aerobic exercise shortens sleep latency, increases the proportion of deep sleep, reduces nighttime awakenings, and improves overall sleep architecture, thereby enhancing sleep quality [27, 73]. From a physiological perspective, physical activity regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, lowers cortisol levels, and reduces sympathetic nervous system activity, thereby alleviating hyperarousal and improving sleep initiation [74, 75]. Among college students, engagement in physical activity has also been associated with decreased pre-sleep electronic device use, reduced bedtime procrastination, and a reestablishment of healthier sleep–wake rhythms [76, 77]. As such, physical activity is both a feasible and effective non-pharmacological intervention for promoting sleep health and managing psychological well-being in college populations. Based on the above evidence, the present study hypothesizes that physical activity moderates the relationships among anxiety, subjective well-being, and sleep hygiene (H3).

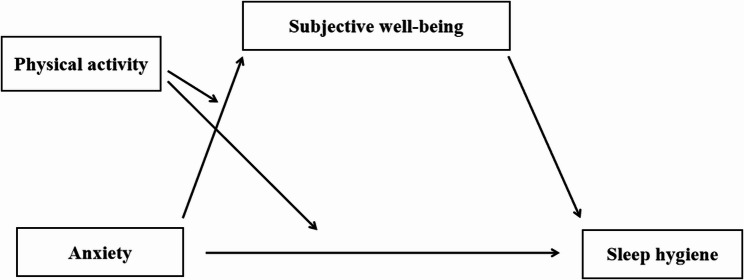

The present study aims to explore the relational pathways among physical activity, anxiety, subjective well-being, and sleep hygiene, and to construct a moderated mediation model based on existing literature. It is hypothesized that anxiety, as a form of negative emotional response, not only directly impairs sleep hygiene but also indirectly influences it by reducing levels of subjective well-being. Physical activity is further conceptualized as a moderating variable that may buffer the effects of anxiety on both subjective well-being and sleep hygiene. Specifically, by enhancing individuals’ psychological resilience and biopsychosocial functioning, physical activity may attenuate the negative impact of anxiety across both pathways. Through the construction of this moderated mediation model, the study seeks to uncover the protective role of physical activity within the pathway from anxiety to sleep hygiene via subjective well-being, thereby offering theoretical insight into strategies for improving mental health and sleep practices among college students. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that physical activity moderates the relationships among anxiety, subjective well-being, and sleep hygiene, and proposes a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Moderated mediation model

Methods

Participants

In January 2025, convenience sampling was used to recruit 3,217 college students from six provinces in China: Southwest China, Northwest China, Central China, North China. During the data screening process, invalid responses were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) extensive missing data or duplicated responses; (2) highly mechanical or patterned answers suggestive of inattentive responding; and (3) abnormally short completion times, indicating poor data quality. After filtering, 3,007 valid questionnaires were retained, Yielding an effective response rate of 93.97%. Among the participants, 1,267 were male and 1,740 were female, with a mean age of 19.03 years (M = 19.03, SD = 1.18). The grade-level distribution was as follows: freshmen (n = 1,371), sophomores (n = 1,431), juniors (n = 194), and seniors (n = 11). Prior to the formal survey, the research team provided all participants with detailed information about the study’s purpose, questionnaire content, and intended use of the data. It was clearly stated that there were no potential risks involved, and participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. All students participated voluntarily and signed informed consent forms. The questionnaires were distributed online through class channels, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the researcher’s affiliated institution.

Measures

Given that most constructs in the present study were operationalized with single-item indicators, a separate validation study was conducted prior to the main investigation. An independent sample of 2,033 adolescents (M_age = 15.4 ± 1.7 years, 51.3% female) who did not participate in the primary survey completed both the single-item measures and the psychological abuse and neglect subscales of the Short Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (SCTQ) [78]. The SCTQ subscales demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this calibration sample Cronbach’s α = 0.878, Convergent validity was then evaluated by computing Pearson correlations between the SCTQ subscale scores and the corresponding single-item instruments. All associations were moderate to strong, supporting the criterion-related validity of the brief measures used in the main study.

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) scale. This scale consists of two items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never; 4 = always), with total scores ranging from 2 to 8. Higher scores indicate greater severity of anxiety symptoms [79, 80]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.850.

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being was measured using a single-item question [81]: “Taking all things together, to what extent would you say you are happy or unhappy with your life at present?” Responses were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = very unhappy; 7 = very happy), with higher scores indicating greater levels of subjective well-being. This item has been widely used in previous research and shown to be a valid and reliable measure [82]. In the present sample, the measure correlated negatively with childhood emotional abuse (r =–0.324, p < 0.001), an effect size comparable to those reported in prior work (r =–0.29 to − 0.38) [83]. This pattern supports the criterion-related validity of the single-item subjective well-being indicator for use in the current study.

Sleep hygiene

Sleep hygiene was evaluated using a single-item self-report measure [84]: “Reflect on the overall quality of your sleep over the past 7 days, including factors such as total hours slept, ease of falling asleep, frequency of nighttime awakenings (excluding trips to the bathroom), early morning awakenings, and the overall feeling of refreshment upon waking. On a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means ‘very poor’ and 10 means ‘very good,’ how would you rate your sleep quality over the past week?” Higher scores represent better perceived sleep quality. This method has been widely adopted in prior studies and demonstrated good reliability and applicability in evaluating sleep quality in research populations [85, 86]. SIn the present study, the measure correlated negatively with childhood emotional abuse (r =–0.317, p < 0.001), an effect magnitude comparable to that reported in similar populations (r − 0.28 to–0.35) [87]. These findings corroborate the criterion-related validity of the single-item indicator for assessing sleep hygiene under the current research conditions.

Physical activity

Physical activity was assessed using a single-item measure: “In the past 7 days, how many times did you engage in physical exercise or activity for at least 20 minutes that made you sweat or breathe hard?” Response options ranged from 0 to 7 days [88]. This measure has been validated in prior studies and is considered to have good reliability and validity for college student samples [89–92].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0. Prior to any inferential procedures, the assumption of univariate normality for each continuous variable was examined with the Shapiro–Wilk test, supplemented by descriptive indices of central tendency (M), dispersion (SD), skewness, and kurtosis. In accordance with Kim’s guidelines [93], absolute skewness < 2.0 and absolute kurtosis < 7.0 were taken as evidence that the data were sufficiently close to a normal distribution for parametric testing (Table 1). Bivariate associations were then assessed with Pearson correlations. To evaluate common-method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted; the first unrotated factor accounted for 29.6% of the total variance—well below the 40% threshold—indicating that common-method variance was not a serious threat to the validity of the findings. Subsequently, the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Models 4 and 8) [94] was employed to test the mediation model with Subjective well-being as the mediator and the moderating effects of physical activity on the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene. To enhance the robustness of model estimates, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was used to construct 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for evaluating the significance of the effects. All statistical tests were conducted using a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and normality tests for key study variables

| variable | Mean ± SD | Minimum value | Maximum value | Absolute skewness | Absolute kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 3.37 ± 1.213 | 2 | 8 | 0.787 | 1.136 |

| Subjective well-being | 5.03 ± 1.377 | 1 | 7 | −0.794 | 0.026 |

| Sleep hygiene | 7.08 ± 1.887 | 1 | 10 | −0.457 | 0.183 |

| Physical activity | 3.43 ± 2.064 | 0 | 7 | 0.353 | −0.781 |

Results

Common method bias test

To assess the potential influence of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. An unrotated principal component analysis extracted four factors with eigenvalues greater than one. The first factor accounted for 19.583% of the total variance, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 40%. This result indicates that common method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

Correlation analysis

As shown in Table 2, anxiety was significantly negatively correlated with subjective well-being (r = −0.369, p < 0.001), sleep hygiene (r = −0.340, p < 0.001), and physical activity (r = −0.079, p < 0.001). Subjective well-being was significantly positively correlated with sleep hygiene (r = 0.353, p < 0.001). Additionally, physical activity was positively correlated with both subjective well-being (r = 0.062, p < 0.001) and sleep hygiene (r = 0.118, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Anxiety | - | ||

| 2 Subjective well-being | −0.369*** | - | |

| 3 Sleep hygiene | −0.340*** | 0.353*** | - |

| 4 Physical activity | −0.079*** | 0.062*** | 0.118*** |

***: p<0.001

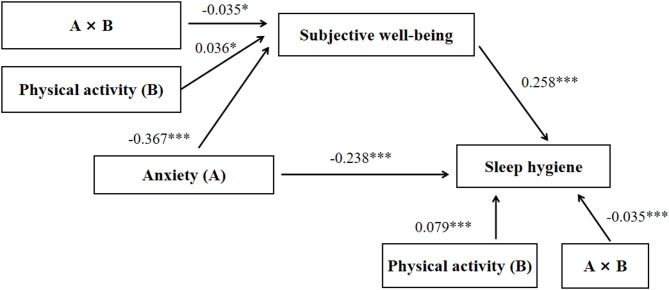

Mediation model test

After controlling for demographic variables, the path model presented in Tables 3 and 4; Fig. 2 revealed that anxiety significantly negatively predicted sleep hygiene (β = −0.241, p < 0.001). When subjective well-being was introduced as a mediating variable, the predictive effect of anxiety on sleep hygiene remained significant, indicating a partial mediation effect. Further analysis showed that anxiety significantly negatively predicted subjective well-being (β = −0.368, p < 0.001), and subjective well-being positively predicted sleep hygiene (β = 0.262, p < 0.001), suggesting that subjective well-being played a significant mediating role in the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene.

Table 3.

Mediation model test

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | β | SE | t | R² | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being | Anxiety | −0.368 | 0.017 | −21.624*** | 0.138 | 68.410*** |

| Sleep hygiene | Anxiety | −0.241 | 0.017 | −13.471 *** | 0.179 | 81.30 2*** |

| Subjective well-being | 0.263 | 0.017 | 14.690*** |

***: p<0.001

Table 4.

Mediation model path analysis

| Intermediate path | Effect size | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | Proportion of mediating effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.338 | 0.017 | −0.371, −0.304 | |

| Direct effect | −0.243 | 0.018 | −0.276, −0.206 | 71.47% |

| Total indirect effect | −0.097 | 0.009 | −0.116, −0.079 | 28.53% |

Fig. 2.

Mediation model diagram

Moderated mediation model test

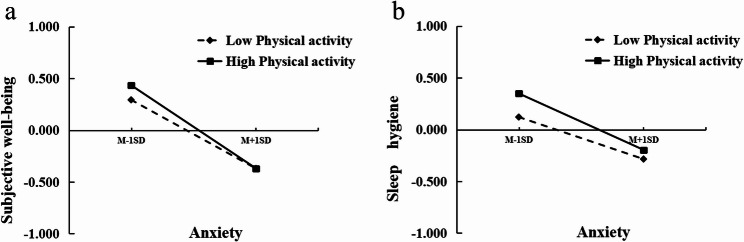

After controlling for demographic variables, the results presented in Tables 5 and 6; Figs. 3 and 4 showed that, even after incorporating physical activity as a moderator, subjective well-being continued to significantly and positively predict sleep hygiene. Additionally, physical activity itself positively predicted sleep hygiene. Moreover, the interaction term between physical activity and anxiety significantly predicted sleep hygiene, indicating a clear moderating effect. Further analysis of the moderating effect at different levels of physical activity revealed that the relationship between subjective well-being and sleep hygiene remained significant across low, medium, and high levels of physical activity (see Table 5), suggesting that the moderating role of physical activity is robust across varying intensity levels.

Table 5.

Testing the moderated mediation model

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | β | SE | t | R² | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being | Anxiety (A) | −0.367 | 0.017 | −21.497*** | 0.141 | 54.313 *** |

| Physical activity (B) | 0.036 | 0.017 | 2. 037* | |||

| A*B | −0.035 | 0.017 | −2.118* | |||

| Sleep hygiene | Anxiety (A) | −0.238 | 0.018 | −13.339*** | 0.187 | 68.291*** |

| Subjective well-being | 0.258 | 0.018 | 14.466*** | |||

| Physical activity (B) | 0.079 | 0.017 | 4.673*** | |||

| A*B | −0.035 | 0.016 | −2.161*** |

*: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001

Table 6.

The moderated effect of different levels of physical activity between subjective well-being and sleep hygiene in anxiety

| Physical activity levels | Effect size | SE | t | Lower Limit 95%CI | Upper Limit 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | −0.203 | 0.024 | −8.613*** | −0.249 | −0.157 |

| Medium | −0.238 | 0.018 | −13.339 *** | −0.273 | −0.203 |

| High | −0.273 | 0.025 | −11.089*** | −0.321 | −0.225 |

***: p<0.001

Fig. 3.

Moderated mediation model (*: p < 0.05; ***: p < 0.001)

Fig. 4.

Simple Slope Chart (a) The moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between anxiety and subjective well-being; (b) The moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene)

After controlling for demographic variables, the results presented in Table 5 and Fig. 3 indicate that physical activity significantly moderates the paths from anxiety to both subjective well-being and sleep hygiene. Specifically, physical activity positively predicted subjective well-being (β = 0.036) and sleep hygiene (β = 0.079 , p < 0.001). In addition, interaction effects between anxiety and physical activity were observed for both outcomes: the interaction term significantly moderated the path from anxiety to subjective well-being (β = −0.035) and the path from anxiety to sleep hygiene (β = −0.035). Although not all paths reached conventional levels of statistical significance, the results suggest that physical activity exerts a generally positive moderating effect across the model. Detailed proportions of the contribution of each path are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

In the context of increasing academic pressure and rapid societal transformation, the high prevalence of anxiety symptoms among college students has become a central concern in mental health research [95]. The present study further confirmed that anxiety exerts a significant influence on sleep hygiene in this population. Existing literature suggests that anxiety not only impairs emotional well-being but also affects sleep hygiene through a complex interplay of physiological arousal, behavioral dysregulation, and emotional maladjustment [96]. From a neurophysiological perspective, anxiety activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis over prolonged periods, leading to sustained sympathetic nervous system excitation and elevated stress hormone levels, while simultaneously suppressing the secretion of hormones essential for sleep onset [97]. This chronic stress response disrupts the normal sleep–wake rhythm, reduces light sleep duration, fragments deep restorative sleep, and results in an abnormal advance and increase in the proportion of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, ultimately destabilizing the structure of nighttime sleep [98]. Additionally, hyperactivity in the locus coeruleus increases nighttime alertness, and hypothalamic orexin neurons—which regulate arousal and appetite—may become excessively active due to anxiety-induced central excitation, contributing to nighttime eating impulses and further disturbing energy metabolism and arousal balance [99]. Anxiety is also closely linked to cognitive dysfunction. Studies have shown that it impairs sustained attention, reduces information processing efficiency, and disrupts decision-making capacity [100]. These cognitive impairments affect daytime learning and adaptability, while also increasing susceptibility to repetitive worry and hyperactive thinking before sleep. At the behavioral level, anxiety often leads to social withdrawal and decreased academic motivation [101]. Lacking appropriate outlets for emotional expression, individuals may engage in compensatory behaviors before bedtime, such as prolonged electronic device use, alcohol or medication dependence, binge eating, frequent napping, or engaging in non-sleep-related activities in bed [102, 103]. These behaviors gradually erode healthy sleep habits and severely disrupt the foundational behavioral structure of sleep hygiene [104]. Moreover, the wide-ranging influence of anxiety on the autonomic nervous system may induce physiological chain reactions including gastrointestinal discomfort, cardiovascular irregularities, and immune suppression—symptoms that often intensify before sleep, making it even more difficult to fall asleep [105, 106]. From a psychological mechanism perspective, emotion regulation models suggest that individuals with anxiety are more likely to adopt maladaptive strategies such as suppression, avoidance, or rumination. During nighttime—when emotional fluctuations are more pronounced—these ineffective strategies often result in dual activation of emotional and cognitive systems [107]. Over time, the accumulation of psychological burdens depletes one’s self-regulatory resources, making it harder to resist impulses for immediate gratification and to maintain a stable, healthy pre-sleep routine [108]. For college students, who are at a critical stage of identity formation, role exploration, and adaptive stress confrontation, the negative effects of anxiety are often more pronounced. In sum, anxiety impairs sleep hygiene not only through direct physiological mechanisms but also by undermining cognitive functions, disrupting behavioral patterns, and weakening emotional regulation, thus exerting a multifaceted and comprehensive influence (H1).

From the findings of this study, it is evident that anxiety not only directly reduces levels of subjective well-being among college students, but also indirectly influences their sleep hygiene behaviors by weakening life satisfaction, reducing positive emotional experiences, and impairing social adaptability. When faced with academic stress and uncertainty about the future, college students are prone to experiencing anxiety, and this persistent tension and worry often lead to emotional exhaustion, social withdrawal, and diminished motivation. Over time, such patterns may contribute to negative emotional experiences and cognitive overload, diminishing positive perceptions of life and manifesting as a decline in subjective well-being [109, 110]. Neuroscientific studies have shown that chronic anxiety disrupts prefrontal cortex regulation of the amygdala, heightening sensitivity to negative stimuli while blunting responses to positive emotional cues. This disruption impairs the brain’s reward system, making it more difficult for individuals to derive satisfaction from academic achievement, social interaction, or daily life, thereby intensifying existential doubts and weakening intrinsic motivation to sustain happiness [111, 112]. Physiologically, chronic anxiety has also been linked to elevated pro-inflammatory markers and neurotransmitter imbalances, both of which further compromise emotional stability and the sense of well-being [113]. From a psychological perspective, the process model of emotion regulation suggests that individuals experiencing anxiety tend to rely on maladaptive strategies such as suppression and rumination, rather than proactive regulation before emotional arousal occurs [114]. For college students, whose cognitive coping mechanisms are still developing, this may result in a downward spiral of self-blame and repetitive thinking, impairing the generation of positive emotions and the maintenance of subjective well-being [115]. As anxiety accumulates, individuals may begin to question the meaning of their academic, social, or personal lives, leading to a gradual erosion of subjective well-being and increased psychological isolation [116]. Although anxiety itself substantially disrupts sleep hygiene, subjective well-being—as a positive psychological resource—may serve a protective function across emotional regulation, behavioral choices, and physiological pathways [117]. Studies have found that college students with higher levels of subjective well-being are more likely to maintain regular sleep routines and avoid maladaptive pre-sleep behaviors such as binge eating, excessive use of electronic devices, or reliance on caffeine or alcohol, thereby reducing circadian rhythm disruption [104, 118]. From an emotional perspective, the broaden-and-build theory posits that positive emotions expand cognitive repertoires and enhance flexibility, facilitating a relaxed mental state before sleep, which shortens sleep latency and reduces nighttime awakenings [119, 120]. Physiologically, subjective well-being is closely associated with the circadian rhythms of sleep-related hormones such as cortisol and melatonin [121]. Individuals with higher subjective well-being tend to have lower pre-sleep cortisol levels, which promotes neural stability and supports normal hormonal secretion, thus improving sleep quality [122]. Moreover, subjective well-being has been linked to greater self-efficacy and self-control, making individuals more inclined to adopt healthy pre-sleep behaviors such as exercise, mindfulness, or reading, rather than resorting to medication or other stimulants [123, 124].Taken together, subjective well-being exerts its influence on sleep hygiene across multiple levels-emotion regulation, behavioral optimization, and neurophysiological modulation—positioning it as a key mediating variable and vital psychological resource in the relationship between anxiety and sleep hygiene (H2).

The present study found a significant positive correlation between physical activity and subjective well-being. Moderate and regular physical exercise not only promotes physical health but also effectively alleviates negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and tension [125–129], thereby enhancing individuals’ overall psychological experience and quality of life, ultimately leading to elevated levels of subjective well-being [72]. Neuroscientific evidence supports this association, indicating that physical activity stimulates the secretion of neurotransmitters such as endorphins, dopamine, and serotonin, which activate the brain’s reward circuitry. This neurochemical response fosters emotional satisfaction and pleasure, providing an essential physiological foundation for subjective well-being [130]. Furthermore, the effort-recovery theory suggests that academic stress may deplete self-regulatory resources in college students, and physical activity serves as both a restorative behavior and an effective stress-buffering mechanism. It helps release accumulated stress, replenish cognitive resources, and restore emotional resilience [131]. Notably, social connections formed through physical activity can reduce feelings of loneliness, increase perceived social support, and promote a stronger sense of emotional belonging and life satisfaction [132]. Research also indicates a positive dose-response relationship, with subjective well-being steadily increasing alongside higher frequency and duration of physical activity [133]. In addition, physical activity contributes to improved cardiovascular function, enhanced immune responses, lower obesity risk, and slower aging processes, all of which are strongly associated with better physical and mental health. These objective health improvements, in turn, reinforce individuals’ positive evaluations of life [106, 134]. Participation in sports not only strengthens the body but also supports future adaptability, social engagement, and even employment competitiveness for college students [134]. Under increasing academic pressure and disrupted life rhythms, college students often exhibit unhealthy sleep hygiene behaviors, such as bedtime procrastination, excessive electronic device use, nighttime eating impulses, and reliance on substances like caffeine or alcohol for sleep aid [135]. The present study found that physical activity was significantly positively associated with sleep hygiene. Prior research suggests that physical activity plays a moderating role in this relationship. Regular exercise strengthens circadian signals, making individuals more likely to feel naturally sleepy at consistent times and reducing pre-sleep stimulating behaviors like screen exposure or delayed sleep onset [136]. The emotional relaxation effect of exercise helps discharge the anxiety and stress accumulated during the day, attenuating their rebound impact at night. This, in turn, reduces compensatory behaviors such as binge eating or substance reliance [137]. On a physiological level, physical activity influences the neuroendocrine system: the gradual drop in body temperature post-exercise mimics natural sleep onset cues, while exercise-induced endorphin and serotonin release improves mood and promotes psychological relaxation [138, 139]. Moreover, moderate exercise regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, lowers cortisol levels, and reduces nocturnal hyperarousal, thereby alleviating sleep initiation and maintenance problems [140]. Individuals who consistently engage in physical activity demonstrate greater self-control, which helps them resist anxiety-driven behaviors such as binge-watching in bed or late-night overeating [141].Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that physical activity serves a moderating role in the relationship between anxiety and subjective well-being, as well as between subjective well-being and sleep hygiene, thus validating the moderated mediation model proposed in this study (H3).

Limitations

Although this study established a preliminary moderated mediation model in which physical activity influences college students’ sleep hygiene by moderating the relationship between anxiety and subjective well-being, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. It is possible that dynamic and bidirectional relationships exist among physical activity, subjective well-being, and anxiety. Future research could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to verify the causal pathways among these variables more precisely. Second, data collection was based primarily on self-report questionnaires. Although validated and reliable instruments were used, the results may still be influenced by social desirability bias and subjective judgment errors. Future studies are encouraged to incorporate multi-source data collection methods-such as wearable fitness trackers to monitor physical activity, objective sleep monitoring tools, and physiological indicators (e.g., cortisol levels or heart rate variability)—to improve ecological validity. Third, the study did not differentiate the type, frequency, or timing of physical activity. Different forms and intensities of exercise may exert heterogeneous effects on psychological states and sleep outcomes. Further refinement in variable categorization is warranted. Additionally, the current study conceptualized sleep hygiene primarily from a behavioral perspective, without incorporating physiological components such as circadian rhythms or the structure of REM and NREM sleep. Given the complex neuroregulatory mechanisms underlying anxiety and subjective well-being, future studies may utilize functional neuroimaging techniques (e.g., resting-state fMRI or EEG) to examine brain network activity and provide more direct evidence for the biological mechanisms linking psychological states and sleep behaviors. Moreover, the sample was drawn from universities in specific regions of China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Cultural variations in the structure and expression of subjective well-being should be taken into account. Future research could expand the sample to include more diverse geographic areas and conduct cross-cultural or multi-site studies to enhance external validity. Finally, this study did not examine potential moderating variables such as gender, academic year, or residential type. Future work could construct multilevel models to explore how the pathways may vary across subpopulations, thereby offering empirical foundations for more tailored mental health interventions and exercise-based prescriptions for college students. Although single-item measures of subjective well-being, sleep hygiene, and physical activity were employed in the present study, and each of these items has been frequently used in large-scale surveys, their psychometric limitations warrant careful consideration. Single-item scales capture only a narrow slice of a complex construct, thereby omitting critical facets that multi-item inventories are designed to assess. Subjective well-being, for instance, comprises both an affective component (positive and negative affect) and a cognitive component (life satisfaction); a global item such as “Overall, how happy do you feel?” cannot disentangle these dimensions. Similarly, sleep hygiene encompasses behavioral regularity (e.g., consistent bed- and wake-times), pre-sleep routines (e.g., avoidance of caffeine and electronic devices), and environmental factors (e.g., darkness, temperature); a single question asking whether one “maintains good sleep habits” obscures these nuances. Physical activity must likewise be parsed into intensity (light, moderate, vigorous), frequency (sessions per week), and modality (aerobic, resistance, flexibility); a solitary item recording “days of exercise per week” fails to provide the granularity required for accurate quantification. Because no additional items are available to triangulate responses, internal consistency reliability is inherently low and measurement error is likely inflated. This imprecision can introduce temporal instability and reduce the reproducibility of observed associations. Although the reliability coefficients reported herein appear acceptable, the validity of these single-item indicators remains questionable, and any substantive interpretation should be tempered accordingly.

Future directions

This investigation delineates, for the first time, the mechanistic pathways through which anxiety compromises sleep hygiene in university students by demonstrating that subjective well-being serves as a key intermediary process, while physical activity operates as a contextual moderator that attenuates the anxiety–sleep dysregulation link. These findings refine and extend transactional theories of emotion–behavior interaction by embedding them within the unique developmental demands of emerging adulthood, a period characterized by heightened psychosocial stress and evolving self-regulatory capacities. From a research standpoint, our cross-sectional model should now be subjected to longitudinal and experimental tests that can disentangle temporal precedence and rule out alternative causal orders. Multi-site and cross-cultural replications are needed to determine whether the observed mediation and moderation effects generalize across educational systems and sociocultural contexts that differ in academic pressure, collectivism, or sleep norms. Future studies could also broaden the nomological network by testing additional mediators—such as specific emotion-regulation strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, rumination) and sleep-related cognitions (e.g., dysfunctional beliefs about sleep)—as well as moderators like gender, chronotype, or cumulative academic stress. For practitioners—including university administrators, mental-health counselors, and physical-education professionals—the evidence supports a multi-tiered intervention blueprint. First, evidence-based mindfulness programs (e.g., Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, brief guided breathing, or 5-minute body-scan meditations) should be systematically integrated into existing mental-health services to provide students with real-time tools for anxiety regulation. Second, cognitive-behavioral modules that train cognitive reappraisal can be disseminated through interactive workshops or mobile health applications, thereby enhancing adaptive coping repertoires. Third, PA must be reconceptualized not merely as a generic health behavior but as a potent, targeted emotion-regulation strategy. Universities can operationalize this shift via scalable, low-threshold initiatives such as peer-led fitness challenges, campus-wide walking clubs, restorative yoga sessions, or gamified group-exercise classes that confer co-curricular credit. These PA offerings should be synchronized with sleep-hygiene psychoeducation delivered through first-year seminars, residence-hall programming, or digital microlearning modules that emphasize consistent sleep–wake schedules, stimulus control, and pre-sleep routines. An integrated intervention that simultaneously targets emotion regulation, subjective well-being enhancement, and sleep-habit management—co-designed and implemented through coordinated efforts among psychology, kinesiology, and student-affairs divisions—holds the greatest promise for producing sustainable improvements in student mental health and sleep quality.

Conclusion

This study systematically explored the mechanism by which anxiety affects sleep hygiene among college students, confirming the mediating role of subjective well-being and the moderating effect of physical activity in the pathways from anxiety to subjective well-being and from subjective well-being to sleep hygiene. The findings extend the theoretical perspective on the interplay between emotional health and sleep behaviors. They underscore the importance of fostering positive psychological resources and guiding healthy behavioral patterns in the context of mental health support for college students. At a mechanistic level, the study reveals the internal linkage between anxiety reduction, well-being enhancement, and improved sleep hygiene. Universities should integrate the enhancement of emotional regulation and subjective well-being into their psychological support systems. On one hand, strategies such as mindfulness training and cognitive reappraisal can help students learn to regulate anxiety. On the other, physical activity should be encouraged as a natural regulatory resource for stabilizing emotions and boosting happiness, thereby promoting better sleep hygiene even in the face of anxiety. Future intervention programs may consider combining physical education, psychological counseling, and sleep routine management to develop integrated pathways for psychological adjustment and behavioral intervention among college students.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peng-jinyin’s revision. Hard Work Brings Good Luck.

Author contributions

Peng JY 1245, Liu MF 1235, Wang Z 235, Xiang L 12356, Liu Y 123456.1 Conceptualization; 2 Methodology; 3 Data curation; 4 Writing - Original Draft; 5 Writing - Review & Editing; 6 Funding acquisition.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [our experimental team’s policy] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Biomedicine Ethics Committee of Jishou University before the initiation of the project (Grant number: JSDX-2024-0086). Informed consent was obtained from the participants before the start of the program. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lei Xiang, Email: 819459543@qq.com.

Yang Liu, Email: ldyedu@foxmail.com, Email: 2022800006@stu.jsu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bruni O, Galli F, Guidetti V. Sleep hygiene and migraine in children and adolescents. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(Suppl 25):57–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L, et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binjabr MA, Alalawi IS, Alzahrani RA, Albalawi OS, Hamzah RH, Ibrahim YS, Buali F, Husni M, BaHammam AS, Vitiello MV, et al. The worldwide prevalence of sleep problems among medical students by problem, country, and COVID-19 status: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 109 studies involving 59427 participants. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2023;9(3):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Li L, Wang YY, Wang SB, Li L, Lu L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Chiu H, Hou CL, Jia FJ, et al. Sleep duration and sleep patterns in Chinese university students: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(10):1153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Q, Zhang Q, Wang T, You Q, Liu C, Cao S. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among college freshmen in China. Sci Rep-UK. 2021;11(1):23075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pham HT, Chuang HL, Kuo CP, Yeh TP, Liao WC. Electronic device use before bedtime and sleep quality among university students. Healthcare-Basel. 2021;9(9):1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.de Winter AF, Visser L, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Reijneveld SA. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of multiple health risk behaviors among adolescents: the TRAILS study. Prev Med. 2016;84:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kianersi S, Zhang Y, Rosenberg M, Macy JT. Association between e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation in U.S. Young adults: results from the 2017 and 2018 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh N, Wanjari A, Sinha AH. Effects of nicotine on the central nervous system and sleep quality in relation to other stimulants: a narrative review. Cureus J Med Sci. 2023;15(11):e49162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Zhao Z, Chen D, Peng Y, Lu Z. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2022;63(11):1222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fucito LM, DeMartini KS, Hanrahan TH, Whittemore R, Yaggi HK, Redeker NS. Perceptions of heavy-drinking college students about a sleep and alcohol health intervention. Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13(5):395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington, DC, US: National Academies; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Evolution of concepts of stress. Stress. 2007;10(2):109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamad NE, Sidik SM, Akhtari-Zavare M, Gani NA. The prevalence risk of anxiety and its associated factors among university students in Malaysia: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd ed. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press; 2002. p. 704. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed I, Hazell CM, Edwards B, Glazebrook C, Davies EB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies exploring prevalence of non-specific anxiety in undergraduate university students. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han W, Xu L, Niu A, Jing Y, Qin W, Zhang J, Jing X, Wang Y. Online-based survey on college students’ anxiety during COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2021;14:385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chand SP, Marwaha R. Anxiety. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed]

- 19.Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94(12):1816–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao C, Bihn D. Excess anxiety’s effect on the occurrence of insomnia in adolescents in late adolescence. J Asian Multicult Res Med Health Sci Study. 2021;2:52–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borkovec TD, Ray WJ, Stober J. Worry: a cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioral processes. Cogn Ther Res. 1998;22(6):561–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Jin C, Zhou X, Chen Y, Ma Y, Chen Z, Zhang T, Ren Y. The mediating role of inhibitory control and the moderating role of family support between anxiety and Internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Tan X, Li Z, Peng H, Tian M, Zhou J, Tian P, Wen J, Luo S, Li Y, Li P et al. Anxiety and inhibitory control play a chain mediating role between compassion fatigue and Internet addiction disorder among nursing staff. Sci Rep-UK. 2025;15(1):12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wang J, Wang N, Qi T, Liu Y, Guo Z. The central mediating effect of inhibitory control and negative emotion on the relationship between bullying victimization and social network site addiction in adolescents. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1520404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wang J, Peng J, Dong J, Peng H, Yi Z, Liu Y, Tang W. The Relationship Between Physical and Psychological Maltreatment and Internet Addiction among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. J Fam Violence. 2025.

- 26.Yi Z, Wang W, Wang N, Liu Y. The Relationship Between Empirical Avoidance, Anxiety, Difficulty Describing Feelings and Internet Addiction Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. J Genet Psychol. 2025;186(4):288–304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.LeBlanc VR, McConnell MM, Monteiro SD. Predictable chaos: a review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;20(1):265–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Çiçek İ, Yıldırım M. Exploring the impact of family conflict on depression, anxiety and sleep problems in Turkish adolescents: the mediating effect of social connectedness. J Psychol Counsellors Schools. 2025:20556365251331108.

- 29.The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Edited by Vasey MW, Dadds MR. Oxford University Press; 2001.

- 30.Sun Y, Li L, Xie R, Wang B, Jiang K, Cao H. Stress triggers flare of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adults. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Liu Y, Xiao T, Pan M. The Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Adolescent Sleep Quality: The Mediating Role of Anxiety and the Moderating Role of Difficulty Identifying Feelings. Psychiatry. 2025:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Chance NW, Pfeiffer K. Sleep disorders and mood, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders: overview of clinical treatments in the context of sleep disturbances. Nurs Clin N Am. 2021;56(2):229–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Çiçek İ, Yıldırım M. Exploring the impact of family conflict on depression, anxiety and sleep problems in Turkish adolescents: the mediating effect of social connectedness. J Psychol Couns Sch. 2025;35(2):130–46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnstad PG. Unhealthy behaviors associated with mental health disorders: a systematic comparative review of diet quality, sedentary behavior, and cannabis and tobacco use. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1268339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geng Y, Gu J, Wang J, Zhang R. Smartphone addiction and depression, anxiety: the role of bedtime procrastination and self-control. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angarita GA, Emadi N, Hodges S, Morgan PT. Sleep abnormalities associated with alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and opiate use: a comprehensive review. Addict Sci Clin Prac. 2016;11(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fusco S, Amancio S, Pancieri AP, Alves M, Spiri WC, Braga EM. Anxiety, sleep quality, and binge eating in overweight or obese adults. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2020;54:e3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Guo HL, Zhang HQ, Xu TQ, He B, Wang ZH, Yang YP, Tang XD, Zhang P, Liu FE. Melatonin prevents sleep deprivation-associated anxiety-like behavior in rats: role of oxidative stress and balance between GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(5):2231–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews S, Hanna P. Investigating the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between nightmares, suicide and self-harm. Sleep med rev. 2020;54:101352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Associate Editors. In: Cash T, editor. Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance. Oxford: Academic Press; 2012. p. vii-ix.

- 41.Stickley A, Koyanagi A. Loneliness, common mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from a general population survey. J Affect Disorders. 2016;197:81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diener E. Subjective well-being. In: Diener E, editor. The science of well-being: the collected works of ed Diener. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2009:11–58.

- 43.Framework POMS, Statistics CON, Education DOBA, Council NR. Subjective Well-Being: measuring happiness, suffering, and other dimensions of experience. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Zhang Y, Luo Y. Does subjective well-being improve self-rated health from undergraduate studies to three years after graduation in China? Healthcare-Basel. 2023;11(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hasking P, et al. Student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(7):623–38. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lolokote S, Hidru TH, Li X. Do socio-cultural factors influence college students’ self-rated health status and health-promoting lifestyles? A cross-sectional multicenter study in dalian, China. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner JC, Keller A. College health surveillance network: epidemiology and health care utilization of college students at US 4-Year universities. J Am Coll Health. 2015;63(8):530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngamaba KH, Panagioti M, Armitage CJ. How strongly related are health status and subjective well-being? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(5):879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ÇİÇEK İ. Mediating role of self-esteem in the association between loneliness and psychological and subjective well-being in university students. Int J Contemp Educational Res. 2022;8(2):83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monden C. Subjective health and subjective well-being. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014. p. 6423–6426.

- 51.Shirom A, Toker S, Jacobson O, Balicer RD. Feeling vigorous and the risks of all-cause mortality, ischemic heart disease, and diabetes: a 20-year follow-up of healthy employees. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, Tugade MM. The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motiv Emot. 2000;24(4):237–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. P Natl Acad SCI USA. 2004;101(49):17312–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson OJ, Vytal K, Cornwell BR, Grillon C. The impact of anxiety upon cognition: perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dou F, Li Q, Li X, Li Q, Wang M. Impact of perceived social support on fear of missing out (FoMO): A moderated mediation model. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(1):63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diener E, Pressman SD, Hunter J, Delgadillo-Chase D. If, why, and when subjective Well-Being influences health, and future needed research. APPL PSYCHOL-HLTH WE. 2017;9(2):133–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harmer B, Lee S, Rizvi A, Saadabadi A. Suicidal ideation. 2025. [PubMed]

- 58.Piggin J. What is physical activity?? A holistic definition for teachers, researchers and policy makers. Front Sports Act Liv. 2020;2:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mahindru A, Patil P, Agrawal V. Role of physical activity on mental health and Well-Being: a review. Cureus J MED Sci. 2023;15(1):e33475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faghy MA, Carr J, Broom D, Mortimore G, Sorice V, Owen R, Arena R, Ashton R. The inclusion and consideration of cultural differences and health inequalities in physical activity behaviour in the UK - the impact of guidelines and initiatives. Prog Cardiovasc Dis; 2025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Zhang J, Zhang Z, Huang M. The China programme: policy supply characteristics for the sustainable promotion of adolescent physical health. Sustainability|.*17*17. 2025.

- 62.Li J, Wan B, Yao Y, Bu T, Li P, Zhang Y. Chinese path to sports modernization: fitness-for-all (Chinese) and a development model for developing countries. Sustainability|.*15*15. 2023.

- 63.Olscamp K, Polster M, Barnett EY, Momot MA, Oziel RN, Bevington F. Local implementation of move your Way-A federal communications campaign to promote the physical activity guidelines for Americans. Health Promot Pract. 2025;26(1):158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Licinio J, Licinio AW, Busnello JV, Ribeiro L, Gold PW, Bornstein SR, Wong ML. The emergence of chronic diseases of adulthood and middle age in the young: the COIDS (chronic inflammation, obesity, insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes, and depressive syndromes) noxious quartet of pro-inflammatory stress outcomes. Mol Psychiatr. 2025;30(7):3348–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Sharma A, Madaan V, Petty FD. Exercise for mental health. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(2):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yin J, Cheng X, Yi Z, Deng L, Liu Y. To explore the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality of college students based on the mediating effect of stress and subjective well-being. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Liu Y, Yin J, Xu L, Luo X, Liu H, Zhang T. The Chain Mediating Effect of Anxiety and Inhibitory Control and the Moderating Effect of Physical Activity Between Bullying Victimization and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2025;186(5):397–412. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Peng J, Wang J, Chen J, Li G, Xiao H, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Wu X, Zhang Y. Mobile phone addiction was the mediator and physical activity was the moderator between bullying victimization and sleep quality. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Gan Y, He Z, Liu M, Ran J, Liu P, Liu Y, Deng L. A chain mediation model of physical exercise and BrainRot behavior among adolescents. Sci Rep-UK. 2025;15(1):17830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.An HY, Chen W, Wang CW, Yang HF, Huang WT, Fan SY. The relationships between physical activity and life satisfaction and happiness among young, middle-aged, and older adults. Int J Env Res Pub He .2020;17(13):4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Eather N, Wade L, Pankowiak A, Eime R. The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: a systematic review and the ‘mental health through sport’ conceptual model. Syst Rev-London. 2023;12(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iwon K, Skibinska J, Jasielska D, Kalwarczyk S. Elevating subjective Well-Being through physical exercises: an intervention study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:702678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou J, Chen Y, Ji S, Qu J, Bu Y, Li W, Zhou Z, Wang X, Fu X, Liu Y. Sleep quality and emotional eating in college students: a moderated mediation model of depression and physical activity levels. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hinds JA, Sanchez ER. The role of the Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis in test-induced anxiety: assessments, physiological responses, and molecular details. Stresses|.*2*2. 2022:146–155.

- 75.Arvidson E, Dahlman AS, Börjesson M, Gullstrand L, Jonsdottir IH. The effects of exercise training on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity and autonomic response to acute stress-a randomized controlled study. Trials. 2020;21(1):888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li X, Buxton OM, Kim Y, Haneuse S, Kawachi I. Do procrastinators get worse sleep? Cross-sectional study of US adolescents and young adults. SSM-Popul Hlth. 2020;10:100518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Su Y, Li H, Jiang S, Li Y, Li Y, Zhang G. The relationship between nighttime exercise and problematic smartphone use before sleep and associated health issues: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao XF, Zhang YL, Li LF, Zhou YF, Li HZ, Yang SC. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin J Clin Rehabilitation. 2005;9:105–7. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Eck K, Quick V. GAD-7, GAD-2, and GAD-mini: psychometric properties and norms of university students in the united States. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2021;69:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang L, Liu Y, Yan C, Chen Y, Zhou Z, Shen Q, Zhang F, Zhang T, Liu Z. The Relationship Between Early Warm and Secure Memories and Healthy Eating Among College Students: Anxiety as Mediator and Physical Activity as Moderator. Psychiatry. 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Huppert FA, Marks N, Clark A, Siegrist J, Stutzer A, Vittersø J, Wahrendorf M. Measuring Well-being across europe: description of the ESS Well-being module and preliminary findings. Soc Indic Res. 2009;91(3):301–15. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raudenská P. Single-item measures of happiness and life satisfaction: the issue of cross-country invariance of popular general well-being measures. Humanit Social Sci Commun. 2023;10(1):861. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu Y, Xiao T, Zhang W, Xu L, Zhang T. The relationship between physical activity and internet addiction among adolescents in Western china: a chain mediating model of anxiety and inhibitory control. Psychol Health Med. 2024;29(9):1602–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Snyder E, Cai B, DeMuro C, Morrison MF, Ball W. A new Single-Item sleep quality scale: results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(11):1849–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De Los SJ, Labrague LJ, Falguera CC. Fear of COVID-19, poor quality of sleep, irritability, and intention to quit school among nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr C. 2022;58(1):71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Labrague LJ. Pandemic fatigue and clinical nurses’ mental health, sleep quality and job contentment during the covid-19 pandemic: the mediating role of resilience. J Nurs Manage. 2021;29(7):1992–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Javakhishvili M, Spatz Widom C. Childhood maltreatment, sleep disturbances, and anxiety and depression: a prospective longitudinal investigation. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2021;77:101351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Health A. California healthy kids survey. Physical health & nutirtion module; 2016.

- 89.Waasdorp TE, Mehari KR, Milam AJ, Bradshaw CP. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among middle and high school youth. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(9):2606–17. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang J, Tang L, Liu Y, Wu X, Zhou Z, Zhu S. Physical activity moderates the mediating role of depression between experiential avoidance and Internet addiction. Sci Rep-UK. 2025;15(1):20704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Jia W, Zhang X, Ma Y, Yan G, Chen Y, Liu Y. Physical exercise moderates the mediating effect of depression between physical and psychological abuse in childhood and social network addiction in college students. Sci Rep-UK. 2025;15(1):17869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Wang J, Xiao T, Liu Y, Guo Z, Yi Z. The relationship between physical activity and social network site addiction among adolescents: the chain mediating role of anxiety and ego-depletion. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Kim H. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38(1):52–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(1):4–40. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Anderson TL, Valiauga R, Tallo C, Hong CB, Manoranjithan S, Domingo C, Paudel M, Untaroiu A, Barr S, Goldhaber K. Contributing factors to the rise in adolescent anxiety and associated mental health disorders: a narrative review of current literature. J Child Adol Ps Nurs. 2025;38(1):e70009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Palagini L, Miniati M, Caruso V, Alfi G, Geoffroy PA, Domschke K, Riemann D, Gemignani A, Pini S. Insomnia, anxiety and related disorders: a systematic review on clinical and therapeutic perspective with potential mechanisms underlying their complex link. Neurosci Appl. 2024;3:103936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Godoy LD, Rossignoli MT, Delfino-Pereira P, Garcia-Cairasco N, de Lima UE. A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: basic concepts and clinical implications. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Han KS, Kim L, Shim I. Stress and sleep disorder. Exp Neurobiol. 2012;21(4):141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen L, McKenna JT, Bolortuya Y, Winston S, Thakkar MM, Basheer R, Brown RE, McCarley RW. Knockdown of orexin type 1 receptor in rat locus coeruleus increases REM sleep during the dark period. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32(9):1528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vytal KE, Cornwell BR, Letkiewicz AM, Arkin NE, Grillon C. The complex interaction between anxiety and cognition: insight from Spatial and verbal working memory. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Şanli ME, Çiçek İ, Yıldırım M, Çeri V. Positive childhood experiences as predictors of anxiety and depression in a large sample from Turkey. Acta Psychol. 2024;243:104170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ducarme G, Pizzoferrato AC, de Tayrac R, Schantz C, Thubert T, Le Ray C, Riethmuller D, Verspyck E, Gachon B, Pierre F, et al. Perineal prevention and protection in obstetrics: CNGOF clinical practice guidelines. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(7):455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sejbuk M, Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska AM. Sleep quality: a narrative review on nutrition, stimulants, and physical activity as important factors. Nutrients. 2022;14(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Dresp-Langley B, Hutt A. Digital addiction and sleep. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2022;19(11):6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Ziegler MG. Chap. 61 - Psychological stress and the autonomic nervous system. In: Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Burnstock G, Low PA, Paton JFR, editors. Primer on the autonomic nervous system. 3rd edi. San Diego: Academic Press; 2012. p. 291–293.

- 106.Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey AG, Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiat. 2020;7(7):628–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. Emotion. 2020;20(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]