Abstract

Background

Evidence based practices such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are often underutilized in community mental health settings. Implementation efforts can be effective in increasing CBT use among clinicians, but not all therapists successfully reach CBT competence at the end of training. Past studies have focused on how clinicians overall acquire CBT skills, rather than examining different learning trajectories that clinicians may follow and predictors of those trajectories; however, understanding of learning trajectories may suggest targets for implementation strategies.

Methods

We used growth mixture models to identity trajectories in CBT skill acquisition among clinicians (n = 812) participating in a large scale CBT training and implementation program, and examined predictors (attitudes towards EBPs, clinician burnout, professional field, educational degree level) of trajectory membership. We assessed model fit using BIC, Vuong likelihood tests, and entropy. We hypothesized that there would be at least two trajectories- one where clinicians increased in skills over time and reach CBT competence, and one with minimal increases in CBT skills that did not result in competence. We hypothesized that presence of a graduate degree, more positive attitudes towards EBPs, and lower burnout would predict more positive trajectories in CBT skill acquisition. We did not have a specific prediction for field of study and CBT skill acquisition.

Results

Clinicians followed either a progressive trajectory with steady increases in CBT skills over time, or a stagnant trajectory with minimal increases in CBT skills. Clinicians with more positive attitudes towards EBPs were 3.51 times more likely to follow a progressive trajectory, while clinicians who were in an ‘Other’ professional field were 0.46 times less likely to follow a progressive trajectory. Contrary to our hypotheses, educational degree and clinician burnout did not predict CBT trajectories.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that attitudes towards EBPs can be an important intervention point to improve CBT skill acquisition for therapists in training and implementation efforts. More structured support for clinicians who did not receive training in mental health focused fields may also help improve CBT learning.

Keywords: Implementation science, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Evidence-based practice

Contributions to the literature.

Evaluation of CBT skill acquisition in implementation efforts typically focuses on overall CBT fidelity at the end of training. There is limited focus on different learning trajectories that therapists may follow, making it difficult to tailor trainings to therapists.

This study is one of the first to examine different trajectories in how therapists in a large-scale implementation effort acquire CBT skills over time, and provides insights into indicators of skill acquisition over the course of training.

Trajectories in CBT skill acquisition over time

While evidence-based practices (EBPs) such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective in treating a wide range of mental health disorders [1], they continue to be underutilized in community settings. Implementation efforts to disseminate EBPs in community settings have broadly focused on didactic trainings and/or intensive consultation [2, 3], with very substantial investments of financial and organizational resources dedicated to achievement of strong implementation outcomes [3]. However, not all clinicians successfully learn EBPs in implementation efforts, even after participation in such resource-intensive programming. For example, while the majority of individuals participating in a large scale CBT implementation initiative reached CBT competence by the end of intensive consultation and by the final competence assessment point, about 20% of individuals never demonstrate CBT competence benchmarks [4, 5]. Clinicians may have difficulties learning CBT due to the multi-component nature of CBT that relies not only on specific interventions, but also structural and relational aspects to be effective [6, 7]. The complex nature of CBT may not only make it less likely for some individuals to want to participate in implementation efforts, but may also make it more difficult for some individuals to learn the theories and interventions taught in didactics, and use them in sessions with clients.

Despite evidence suggesting that clinicians do not equally improve in CBT skill use during implementation efforts, there is limited research examining different trajectories of clinicians’ CBT skill acquisition over time. Focus on clinician variability in EBP interventions has typically examined clinician self-reported engagement in interventions and intentions for using EBPs [6, 8], and these studies suggest that there can be high variability in which specific interventions clinicians use, and in their intentions to use CBT. For example, community clinicians follow different patterns in cognitive, behavioral, family, and psychodynamic intervention use, and intentions to use specific CBT techniques such as exposure and behavioral activation can vary based on client population (e.g. clients receiving CBT, clients with anxiety, clients with depression) [8]. Differences in self-reported intervention usage and intention of using CBT suggest that clinicians may also differ in how they learn CBT, as there may be variability in what CBT interventions they are incorporating new skills from their trainings, and subsequent opportunities to refine their CBT skills [6]. Understanding general trajectories of CBT skill acquisition over time can tailor implementation and consultation efforts to provide targeted support to clinicians in developing CBT skills if they have not developed skills at key time points, which may be particularly useful given complexities associated with CBT. Fidelity is widely recognized as a crucial implementation outcome. However, much of the empirical literature has centered fidelity at the end of training, not over the course of training. Relatively few studies have examined clinician specific fidelity trajectories or their predictors, instead looking at overall sample aggregate trends due to the large sample sizes required of estimating specific trajectories.

Elucidating patterns in CBT skill acquisition may also begin to inform the development of strategies to increase the efficiency of implementation efforts. Research on EBP implementation efforts indicate that various clinician factors inform CBT skill acquisition and intervention use. More positive attitudes towards EBPs prior to participating in CBT implementation efforts are associated with increased CBT competence at the end of training [4]. Positive attitudes towards EBPs may facilitate greater uptake of skills through increased engagement in didactics, and receptiveness to practice and hone CBT skills. Early knowledge of negative beliefs surrounding EBPs could allow for targeted focus on addressing attitudes that could hinder engagement in CBT. Professional field and receiving graduate training also inform variability in intervention use, where doctoral-level clinicians are less likely to use a variety of eclectic interventions (e.g. a combination of psychodynamic, cognitive, behavioral, and family systems), and social workers are more likely to use eclectic interventions (e.g. high use of the above interventions) [8]. Differences in professional field and graduate training could inform exposure to different EBPs. Foundational skills in CBT and other EBPs could facilitate acquisition of knowledge in CBT skills from didactics, which could contribute to increased comfort in using CBT skills with clients. This may be particularly important for CBT given its multicomponent nature. Understanding how professional field and having a graduate degree inform how individuals learn CBT can also inform efforts to better tailor consultation and didactics to make them more effective. Additionally, clinician burnout has been associated with difficulties engaging with clients [9] and negative impacts on clinical outcomes [10]. Knowledge of how burnout informs skill acquisition could also help consultation efforts in supporting clinicians, particularly in community mental health settings that are consistently under-resourced. Overall, early predictors of more or less successful trajectories may ultimately inform the development of strategies to increase efficiency of implementation efforts by prioritizing clinicians who are most likely to benefit from training, providing additional supports for those who are less likely to otherwise succeed, or other innovative improvements.

The purpose of the current study was to identify different clinician trajectories in CBT skill acquisition over time. We also examined how clinician factors (i.e.. professional field, terminal degree, attitudes towards EBPs, burnout) predict different trajectories. We hypothesized that there would be at least two trajectories in overall CBT skill acquisition- one trajectory where clinicians increased in skills over time and reached CBT competence, and one with minimal increases in CBT skills that did not result in competence. We also hypothesized that presence of a graduate degree, more positive attitudes towards EBPs, and higher professional quality of life would predict trajectories with more successful acquisition of CBT skills over time. We did not have a specific prediction for field of study and CBT skill acquisition.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were community mental health clinicians (n = 812) who participated in an intensive seven-month CBT training and implementation program as part of an EBP-focused policy initiative in an urban public mental health system (the Beck Community Initiative; BCI) [4, 11] between 2008 and 2023. Before starting the training, clinicians completed measures assessing burnout, attitudes toward evidence-based practices, and demographics (including terminal degree and field of study). Clinicians underwent 22 h of CBT didactics focused on a case-conceptualization driven approach, treatment planning, session structure, selection and delivery of interventions for specific presenting problems, and recovery management. Clinicians then attended six months of weekly, 2-h CBT consultation groups led by group facilitators (either BCI Instructors, or clinicians within their agency who were previously certified in CBT through the BCI). During consultation groups, clinicians reviewed skill presentations focused on content delivered in the workshops, developed case conceptualizations for clients on their caseloads, and received feedback on CBT skills from group facilitators and other consultation group members by playing session recordings of their delivery of CBT with clients on their caseloads.

Over the course of the BCI program, clinicians were required to record at least 15 sessions in which they practiced CBT with clients on their regular caseloads. Those recordings were shared for feedback during group consultation, and in addition, 4 sessions were rated for competence by doctoral-level BCI instructors. Rated sessions were recorded at baseline (prior to beginning the workshop), post-workshop (immediately after finishing workshops), mid-consultation (3 months after workshops ended) and at the end of consultation (6 months after workshops ended). To better estimate trajectories in skill acquisition, we only included clinicians who submitted at least two audio recordings at key timepoints (e.g. pre-workshop, post-workshop, mid-consultation, end of consultation). Of 966 clinicians who participated in the training, 154 were excluded from analyses.

Sessions were rated using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS [12, 13]; described in the measures section). Clinicians who fulfilled all training requirements (e.g. attend all workshops, attend 85% consultation groups, submit 15 total recordings including recordings at key timepoints, complete program evaluation measures) received a training completion certificate. Clinicians who completed the training and also earned a score of 40 or above on the CTRS for their 6-month recording earned a certification of competence in CBT. Clinicians who did not earn a 40 by the end of the training program were permitted to retry with additional audio after several months to encourage further skill acquisition and retention in the training program; however, only the initial 6-month recordings were used in the current analyses to best reflect variability in trajectories while holding timepoints for measurement consistent.

Regarding gender identity, 76.4% of clinicians identified as women, 23.4% as men, and 0.2% as nonbinary. Regarding racial identity, 0.2% identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native, 3% as Asian, 27.3% as Black, 1.7% as multi-racial, 35.6% as White, 3.8% as Other, and 28.3% did not indicate their racial identity or preferred not to answer. Regarding ethnic identity, 9.1% of clinicians identified as Hispanic or Latinx, 65.1% did not identify as Hispanic or Latinx, and 25.7% did not indicate their ethnic identity. Average age of clinicians in our sample was 38.5 years (SD = 12.28). Regarding field of training, 20.3% were in psychology, 30% in social work, 2.7% in psychiatry/medicine, 3.1% in education, 27.5% in counseling, 4.6% in couples/family therapy, 0.1% in nursing, 0.4% in faith/spirituality, 2.4% in creative arts, and 9.0% specified other; 3.7% of clinicians had missing data for field of training. For the purposes of our analyses, we combined individuals who specified psychology, psychiatry/medicine, and nursing into the “Psychology/Medicine” category, counseling and couples/family therapy into the”Counseling, Couples, and Family” category, and education, faith/spirituality, creative arts, and other as their fields into a general “Other” category. The majority of clinicians (92.9%) had graduate degrees- 3.4% had a doctorate degree, 2.8% a MD, 3.1% some doctoral coursework, 81.2% a terminal masters degree, 5.9% a bachelor’s degree, 0.7% an associates degree, 0.2% some college coursework, and 2.5% did not indicate their highest degree. 2.5% of clinicians had missing data for graduate degrees. For the purposes of our analyses, we combined individuals who had a doctorate or MD into the “Doctorate/MD” category, and individuals who had some doctoral coursework, bachelor’s degrees, associate’s degrees, and some college coursework into the “No graduate degree” category.

Measures

Demographics

We assessed for clinician cultural identities and other clinician characteristics (e.g. racial identity, ethnic identity, gender, age, highest educational degree, professional field of study) using a demographics questionnaire that was administered prior to starting the training.

CBT Skill

We assessed CBT skill using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS) [12, 13]. The CTRS is often considered the gold standard for behaviorally assessing CBT fidelity, and has been validated in general psychiatric outpatient [14] and community mental health samples [11, 13]. The CTRS is comprised of 11 items, and is rated on a zero to six Likert scale. Zero indicates absence of a specific skill, and six indicates excellent application of the skill. A score of 40 or higher is the benchmark indicator that a clinician is competent in CBT skills [15]. The CTRS assesses CBT fidelity according to three factors: session structure (agenda setting, feedback, pacing and efficient use of time, homework), common factors (collaboration, interpersonal effectiveness, understanding), and CBT specific skills and techniques (guided discovery, strategy for change, key cognitions and behaviors, CBT technique). We used the overall CTRS score for each time point to assess CBT skill. Mean CTRS scores at each time point (e.g. pre-workshop, post-workshop, three-month, six-month) were 20.5 (SD = 6.5), 26.7 (SD = 7.9), 33.3 (SD = 7.0), and 39.7 (SD = 7.7). CTRS scores were rated by a team of CBT experts who underwent training and calibration procedures prior to rating to ensure that their ratings were reliable. Reliability meetings were held quarterly each year to monitor or prevent any rater drift. Interrater reliability was high within the group [ICC = 0.84; 4].

Burnout

We assessed burnout using the Burnout subscale of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) [16], and started collecting this data in 2015. The ProQOL is a 30-item self-report measure that utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Never, 4 = Very Often) to assess overall quality of life that one experiences as a professional helper. The Burnout subscale specifically measures feelings of hopelessness and fatigue that are associated with difficulties managing work related concerns and duties. Sample items include “I feel trapped by my job as a helper” and “I feel worn out because of my work as a helper.” Internal consistency of the Burnout subscale of the ProQOL was 0.77, and 0.7% of clinicians had missing data on the Burnout subscale.

Attitudes towards EBPs

We assessed attitudes towards EBPs using the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) [17], and started collecting this data in 2011. The EBPAS is a 15-item self-report measure that utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Not at All, 4 = To a Very Great Extent) to assess clinician beliefs about the utility of EBPs, perceived barriers, and institutional requirements associated with implementing EBPs. It is often used in EBP implementation studies to understand clinician attitudes towards EBP implementation and adoption of EBPs. More specifically, the EBPAS assesses willingness to adopt new practices and interventions based on their appeal and if required, openness towards new practices and interventions, and perceived divergence between current practices and interventions and research-informed practices and interventions. Sample items include “I would try a new treatment/intervention even if it was very different from what I am used to doing” and “Research based treatment/interventions are not clinically useful.” Higher scores indicate more positive perception of adoption of EBPs. Internal consistency of the EBPAS for the current study was 0.78, and 2.0% of clinicians had missing data on the EBPAS. We used overall EBPAS scores to assess attitudes towards EBPs.

Statistical analyses

We ran a series of growth mixture models (GMMs) to identify different trajectory classes in how clinicians in our sample acquired CBT skills over the course of the training program [18–20]. GMMs are commonly used to identify latent classes of individuals based on growth trajectories of a given variable. Given that we did not have pre-existing hypotheses of whether clinicians with similar trajectories varied on initial CBT skills, and CBT skill acquisition rates, we tested three separate GMMs. Model A did not allow clinicians in the same trajectory class to vary in initial CTRS scores and rates at which their CTRS scores changed over time (e.g. fixed intercepts and slopes), Model B allowed clinicians in the same trajectory class to vary in initial CTRS scores but not in rates of change in CTRS scores (e.g. random intercepts, fixed slopes), and Model C allowed clinicians in the same trajectory class to vary in initial CTRS scores and rates of change in CTRS scores (e.g. random intercepts and slopes). We also tested the fit of one to six class models, and linear and quadratic terms based on plots of CTRS scores over time. To account for potential shared variance from clinicians at the same agency, we allowed models to be clustered at the agency level. We assessed model fit based on BIC, Vuong likelihood tests, and entropy values.

We estimated the unique contribution of professional field, educational degree, attitudes towards EBPs, and burnout in predicting trajectory membership by individually entering attitudes towards EBPs, burnout, educational degree, and field into our final model as predictors of class membership, and the intercepts and slope growth factors. We held the relationship between covariates and growth factors equal across all classes. Social work and master’s degree were set as reference groups for field and graduate degree, as proportionately most clinicians were part of these groups. Given that data collection of attitudes towards EBPs started in 2011, and burnout started in 2015, analyses for these variables focused on clinicians undergoing training during those respective time periods (n = 638 for 2011 onwards; n = 538 for 2015 onwards). Missing data was addressed using full information maximum likelihood. All analyses were conducted in MPlus. In line with available guidance, we did not give preference to any single fit measure; rather, we considered them as a whole along with the substantive interpretation of each solution [19, 21]. In cases where fit indices did not clearly indicate a best-fitting model, we selected the more parsimonious model.

Results

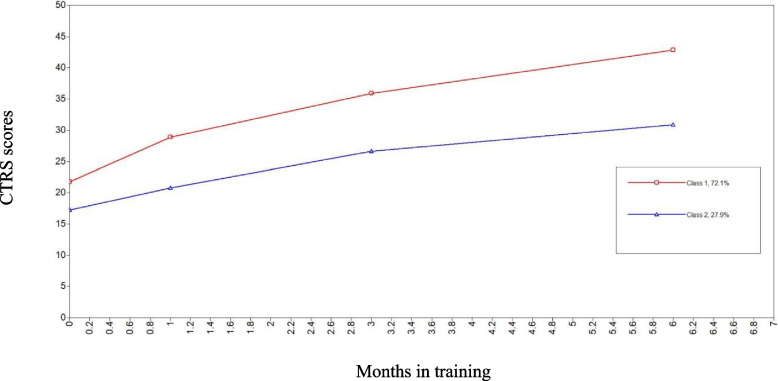

The two class linear GMM with random intercepts and fixed slopes (BIC = 17,770.22, AIC = 17,753.44, entropy = 0.67, p < 0.05), and the two class quadratic GMM with fixed intercepts and slopes (BIC = 17,704.90, AIC = 17,688.13, entropy = 0.67, VLRT = p < 0.01), were the two best-fitting models. For the linear models, a non-significant VLRT indicated that model fit did not improve for the 3-class solution relative to the 2-class solution. Although other fit indices were superior for the 3-class solution, we judged these differences to be small in magnitude and therefore selected the 2-class linear solution. The four, five and six class linear models did not converge. For the quadratic models, both entropy and the VLRT favored the 2-class solution over the 3-class solution. Although AIC and BIC favored the 3-class solution, we prioritized parsimony and selected the 2-class quadratic solution. The five and six class quadrative models did not converge. Based on overall fit indices, we selected the two-class quadratic GMM as our final model. See Table 1 for AIC, BIC, entropy, and Vuong Likelihood Ratio test values for model comparisons of linear GMMs with random intercepts and fixed slopes, and quadratic GMMs with fixed intercepts and slopes. Class One, which we labeled as the “progressive” trajectory, had higher initial CTRS scores, and higher increases in CTRS scores over the entire course of training, particularly at the end of didactics, leveling off near CBT competence at the end of training. Conversely Class Two, which we labeled as the “stagnant” trajectory, had minimal increases in CTRS scores at the end of didactics, smaller increases in CTRS scores over the rest of the training, and did not reach CBT competence at the end of training. See Fig. 1 for graphs of CTRS scores over time, and Table 2 for means and standard deviations of CTRS scores at each time point, for the progressive and stagnant trajectories. Most (72.1%) clinicians evidenced the progressive trajectory, while 27.9% evidenced the stagnant trajectory.

Table 1.

Model fit of growth mixture models

| Model | AIC | BIC | Entropy | VLRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two class linear GMM, RI and FS | 17,753.44 | 17,770.22 | 0.67 | p < .05 |

| Three class linear GMM, RI and FS | 17,743.97 | 17,766.85 | 0.73 | n.s |

| Two class quadratic GMM, FI and FS | 17,688.13 | 17,704.90 | 0.67 | p < .001 |

| Three class quadratic GMM, FI and FS | 17,617.36 | 17,640.23 | 0.60 | n.s |

| Four class quadratic GMM, FI and FS | 17,620.133 | 17,591.155 | 0.63 | n.s |

GMM Growth mixture model, FI Fixed intercept, FS Fixed slope, RI Random intercept, VLRT Vuong Likelihood Ratio Test, n.s. Not significant

Fig. 1.

Growth mixture model trajectories of CBT skills over time

Table 2.

CTRS means and standard deviations of two class quadratic growth mixture model with fixed intercept and slope

| Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Pre-didactics | Post-didactic | Three-month | Six-month |

| Progressive trajectory | 21.8 (6.4) | 28.9 (7.0) | 35.9 (5.4) | 42.8 (4.8) |

| Stagnant trajectory | 16.4 (5.2) | 19.7 (6.2) | 25.8 (5.6) | 30.0 (6.6) |

Educational degree and burnout did not predict class of CBT learning trajectory. However, more positive initial attitudes towards EBPs were significantly associated with higher likelihood of membership in the progressive trajectory (odds ratio = 3.51). Furthermore, selection of “Other” as the specified field was significantly associated with lower likelihood of membership in the progressive trajectory (odds ratio = 0.46). See Table 3 for odds ratio values for all predictors.

Table 3.

Predictors of class membership for progressive trajectory in two class quadratic growth mixture model with fixed intercept and slope

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBPAS | 3.51 | 1.79–6.89 | p < .01 |

| PROQOL | −0.29 | −0.93–0.35 | n.s |

| Graduate degree1 | 1.38 | 0.39–5.00 | n.s |

| Doctorate/MD | 2.63 | n.s | |

| No graduate degree | 0.82 | n.s | |

| Field2 | |||

| Counseling, Couples, Family | 0.69 | 0.38–1.25 | n.s |

| Psychology/Medicine | 0.83 | 0.39–1.75 | n.s |

| Other | 0.46 | 0.26–0.82 | p < .01 |

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, EBPAS Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale, n.s. Not significant

1Reference group = Masters’ degree

2Reference group = Social work

Discussion

Our study is one of the first to date to examine different trajectories in how clinicians acquire CBT skills over time, and the factors that inform these trajectories. Clinicians in our sample overall followed two quadratic trajectories in learning CBT skills. Clinicians in the progressive trajectory started trainings with higher CBT skill use, and had higher increases in CBT skill use at the conclusion of didactics. Clinicians in both trajectories had similar rates of improvement in CBT skill use over the course of consultation groups. Clinicians on average in the progressive trajectory reached CBT competence at the end of training, while clinicians in the stagnant trajectory did not. Clinicians following the same trajectory started training with similar CBT skills, and learned CBT skills at similar rates. Our results suggest that initial CBT skills could be early indicators for how successfully clinicians will learn CBT over the course of training, and may inform how knowledge from didactics is integrated into clinical practice. Clinicians with stronger foundations in CBT skills may be better able to immediately practice CBT skills taught in didactics, be less frustrated surrounding the learning process, and be better able to integrate feedback from consultation groups. Alternatively, clinicians with stronger foundations in CBT may be more receptive to further training in CBT, with fewer biases and preconceptions surrounding CBT principles.

Additionally, differences in CBT competence between both trajectories were more pronounced at the conclusion of intensive didactics, suggesting that how clinicians integrate knowledge from didactics into sessions could be an indicator of successful acquisition of CBT skills. Didactics may provide important foundations for clinicians to build CBT skills over the course of consultation groups, and clinicians who have stronger foundational skills may be better able to translate this knowledge into clinical practice. Conversely, clinicians who have less foundational CBT skills may have greater difficulties integrating didactics knowledge into their clinical work, and need more support.

Consistent with both our hypotheses and past studies on attitudes towards EBPs and CBT skill use [4], clinicians with more positive attitudes towards EBPs were 3.74 times more likely to be in the progressive trajectory. Clinicians with more positive attitudes towards EBPs may have been more engaged throughout the training, and more motivated to practice CBT skills and incorporate feedback from consultation groups into sessions with clients. More negative attitudes towards EBPs may have hindered engagement in the overall training process, making it difficult for clinicians to process skills learned in didactics, implement CBT skills in sessions, and incorporate feedback from consultation groups. More negative attitudes towards CBT may have also resulted in clinicians being less receptive to use CBT interventions during sessions, creating less opportunities to practice skills. Furthermore, clinicians not in mental healthcare-focused fields (e.g., social work, counseling, and psychology) were 0.46 times less likely to be in the progressive trajectory. However, presence of a graduate degree did not predict trajectories in CBT skill acquisition. Our results suggest that the area in which clinicians completed their formal training, rather than the presence or absence of graduate-level training, informs how successfully clinicians learn CBT. On one hand, clinicians who were not trained in mental healthcare-focused fields may have less exposure to CBT principles, which may have made it more difficult to integrate knowledge from didactics, and feedback from consultation groups, into clinical work. However, clinical training is atypical prior to graduate-level training, so it was noteworthy that clinicians without graduate-level training were as able to reach competence in CBT as those with graduate degrees. Clinicians in our sample who did not have graduate degrees included trainees in the process of completing their degrees, and consequently may have been receiving more proximal feedback on skills. Conversely, clinicians with graduate degrees may have relatively less opportunities to receive feedback, resulting in similar learning trajectories as those without graduate degrees. Given past research detailing similar clinical outcomes between trainees and licensed clinicians [22, 23], future research could examine other factors such as feedback that account for these similarities. Finally, burnout did not predict trajectories in CBT skill acquisition. Structural aspects of implementation efforts, such as protected time to participate in consultation groups and didactics, and having clinicians practice CBT skills with clients within their caseload, may have minimized additional burdens placed on clinicians.

Finally, some clinicians in our training following progressive trajectories in CBT skill acquisition did not reach baseline CBT competency at the end of training. While the ultimate outcome of not earning certification was the same between these clinicians and those following stagnant trajectories, quantitative differences in what these clinicians demonstrated in their sessions can still provide useful information in tailoring implementation and training efforts. Individuals in the progressive trajectory who were not certified on average still demonstrated many core CBT skills, and may just require additional support to fine-tune specific CBT skills. Conversely, there is a much wider variability in individuals in the stagnant trajectory at the end of training, with many who struggled to implement core components of CBT, or had general difficulties with all CBT skills across domains. Individuals in the stagnant trajectory who did not reach baseline CBT competency levels may have required more intensive support and feedback in different CBT domains to reach baseline competence. Understanding the trajectories of individuals who did not reach certification can help pre-empt training efforts by allowing more targeted, specific skill domain feedback for individuals in progressive trajectory, and broader more intensive feedback for individuals in the stagnant trajectory.

Limitation and future direction

There were several limitations in the current study. First, we only evaluated CBT skills at four time points. Future studies could evaluate more incremental changes in CBT skill acquisition over time, particularly with the advent of artificial intelligence-based tools that will allow fidelity measurement at large scale. Second, we only evaluated CBT skill acquisition through one largescale implementation effort. CBT skill acquisition could vary across different implementation efforts based on factors such as the dosage of feedback, consultation and length of didactics. Future studies could examine CBT skill acquisition across implementation efforts, and examine common factors underlying different implementation efforts that contribute to increased CBT skill acquisition. Third, we did not evaluate agency level factors, such as agency climate and leadership perceptions surrounding implementation of CBT, which inform how clinicians may invest in learning CBT and develop skills [24, 25]. Future studies could examine the impact of agency factors on CBT skill development. Fourth, we did not examine how clinician skills in specific domains changed over time. Future studies could examine how skills in domains such as session structure and application of CBT techniques shift over the course of training among different groups of clinicians. Fifth, our study focused on clinicians in community mental health settings. Clinicians in other settings (e.g. hospitals/medical centers, counseling centers, private practice) may follow different trajectories in skill acquisition in implementation efforts, and future studies could examine how clinicians in different settings learn CBT. Finally, we did not examine the association of client factors with the CBT skills displayed by clinicians in their sessions. The BCI training is designed to take a case conceptualization driven, transdiagnostic approach to training which provides flexibility to support clinicians across diverse levels of care and client presentations; however, research suggests that even when clinicians have strong intentions to use specific CBT strategies, those intentions may be waylaid by contextual factors including client attributes [6, 26].

Implications

Our results have several implications for research and implementation efforts. Foundational skills in CBT may be an early indicator of how clinicians learn CBT. Future research could examine what foundational skillsets inform successful acquisition of CBT skills, and similarly what skillsets clinicians build upon after didactics to better support clinicians who need more focused support. Early attitudes towards EBPs also appear to be important factors in implementation efforts for trajectories in how clinicians acquire CBT skills. Future research could examine how specific beliefs surrounding EBPs inform how clinicians learn CBT. Factors such as willingness to adopt new practices based on intrinsic motivation versus institutional requirements, and divergence between current practices and research-informed interventions, could differentially inform how clinicians engage with the learning process, and incorporate CBT skills with their clients. Additionally, future research could examine how organizational factors inform attitudes toward EBPs. Leadership attitude and support for clinicians learning CBT may inform how clinicians perceive implementation efforts, and studies examining the impact of clinician, supervisor, and agency leader perceptions of organizational climate surrounding EBPs could elucidate future areas of intervention prior to, and throughout trainings. Additionally, given the decreased likelihood of individuals not in mental healthcare focused fields to acquire CBT skills over the course of training, future research could focus on examining what specific factors associated with field of practice impact learning. This type of knowledge might elucidate areas of intervention to support individuals who do not come from mental healthcare fields in implementation efforts.

Like the current study, implementation efforts of EBPs typically involve intensive didactics, followed by consultation from EBP experts where clinicians receive feedback on EBP fidelity for multiple months [2, 3, 27]. An important aspect of these implementation efforts is tailoring strategies to the contexts of the clinicians attending trainings to facilitate increased uptake of EBPs, as clinicians and settings may vary in different factors that impact how they learn EBPs, such as perceptions of EBPs, and agency readiness and compatibility [28]. Our results suggest multiple avenues where implementation efforts may tailor trainings and consultations to clinicians. First, given the importance of attitudes towards EBPs [4], implementation efforts may benefit from addressing clinician concerns surrounding the uptake of CBT prior to starting training by engaging clinicians themselves, as stakeholders. Interviews and surveys could be used to elicit perspectives towards EBPs so that clinicians may voice concerns that could impact engagement in training [28], which can in turn be used to tailor training and consultation to address those needs. This could involve addressing common assumptions about CBT, processing potential resistance to trainings due to agency requirements, and talking through how CBT may be similar and different from current therapeutic practices before engagement in the training (e.g. orientation), and over the course of didactics and consultation groups to address when these attitudes may be affecting engagement in the learning process.

Furthermore, our results suggest that clinicians who do not come from mental healthcare-focused fields are more likely to have lower CBT skills at the beginning of training, and have smaller increases in CBT skill use following didactics. Clinicians not from mental healthcare-focused fields may need additional support in learning CBT skills. In line with tailoring implementation efforts to unique contexts of clinicians [28], implementation efforts could similarly try to engage clinicians that come from less mental healthcare-focused fields earlier in the process as stakeholders to identify factors that impact uptake of EBPs. Alternatively, clinicians with less mental health training in their backgrounds may benefit from pre-training support to ensure that they have the same building blocks as those from mental healthcare-focused fields. Implementation efforts could also tailor didactics by including more information on how CBT can build on more general therapy skills, provide more examples of CBT interventions being implemented through audio or video recordings, and providing opportunities to practice skills through role plays. Implementation efforts may also benefit from providing additional support to these clinicians in the form of centralized supplemental resources and supports, such as those employed in system-wide implementation efforts [27], and more frequent, individualized feedback on CBT skills throughout the consultation process using role plays, playback of audio recordings, and modeling by expert clinicians may be helpful [3]. Artificial-intelligence-based support tools can also provide immediate feedback on specific CBT skills from session recordings, which may be particularly beneficial for these clinicians so that they can receive frequent, immediate feedback to improve their skill more rapidly [28].

Altogether, early predictors of more or less successful trajectories may ultimately inform the development of strategies to increase efficiency of implementation efforts by facilitating greater tailoring to clinician specific needs. Assessing attitudes towards EBPs, gathering information on training backgrounds, and having clinicians submit baseline audio of CBT sessions can allow for intentional partnership with agency leaders and clinicians participating in trainings to tailor didactics and consultation groups to the unique needs of the training cohort, and to provide additional structural support to clinicians who have difficulties acquiring CBT skills. For example, clinicians with early markers that they may be less likely to acquire CBT skills could undergo a preparatory process that addresses concerns surrounding EBPs, and provides feedback surrounding foundational therapy skills before they formally enroll in implementation efforts. Additional opportunities to engage in structured role plays could also be offered to clinicians at risk of not acquiring CBT skills throughout didactics to cement learning. Clinicians who are more likely to follow progressive trajectory of CBT skill acquisition could be offered more targeted emphasis on growth areas identified from pre-training audio during both didactics and consultation groups so that they are set up for success.

Conclusion

In a large-scale CBT implementation effort among community mental health agencies, we found that clinicians overall followed two trajectories in CBT skill acquisition. Clinicians following a progressive trajectory had slightly higher initial CBT competence and steady increases in CBT skills, and generally reached CBT competence at the end of training. Clinicians following a stagnant trajectory with slightly lower initial CBT competence and minimal increase in CBT skills, and generally did not reach CBT competence at the end of training. Clinicians with more positive attitudes towards EBPs were 3.74 times more likely to follow progressive trajectories, while clinicians who selected ‘Other’ as their professional field were 0.46 less likely to follow progressive trajectories. Clinician burnout and presence of a graduate degree did not significantly predict trajectories in CBT skill acquisition. Our results provide important information surrounding key indicators of clinicians successfully learning CBT skills during implementation efforts with regards to key training timepoints, and clinician specific factors that could be addressed prior to, and throughout training. Future research could examine effectiveness of tailoring implementation efforts based on factors such as prior training background and attitudes towards EBPs, and the impact of agency level factors in implementation efforts.

Abbreviations

- BCI

Beck Community Initiative

- CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- CTRS

Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale

- EBPs

Evidence based practices

- EBPAS

Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale

- ProQOL

Professional Quality of Life

Authors' contributions

PK was a major contributor in conception/design of the study, data analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. AC was a major contributor in conception of the study and manuscript writing. MH was a major contributor in data analysis and interpretation of the data, TAC was a major contributor in conception of the study and manuscript writing.

Funding

There is no funding to report for the current study.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to being associated with therapy recordings and protected by HIPAA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board approval from the University of Pennsylvania was obtained for the study (IRB Protocol # 852818). Informed consent was not sought for this study since the data was collected within the context of ongoing program evaluation, and no responses could be traced back to individual participants.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data was used in any form in the paper.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fordham B, Sugavanam T, Edwards K, Stallard P, Howard R, das Nair R, et al. The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: a meta-review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:448–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valenstein-Mah H, Greer N, McKenzie L, Hansen L, Strom TQ, Wiltsey Stirman S, et al. Effectiveness of training methods for delivery of evidence-based psychotherapies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creed TA, Crane ME, Calloway A, Olino TM, Kendall PC, Stirman SW. Changes in community clinicians’ attitudes and competence following a transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral therapy training. Implement Res Pract. 2021. 10.1177/26334895211030220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creed TA, Stirman SW, Evans AC. A model for implementation of cognitive therapy in community mental health: The Beck Initiative. The Behavior Therapist. 2014;37:3.

- 6.Wolk CB, Becker-Haimes EM, Fishman J, Affrunti NW, Mandell DS, Creed TA. Variability in clinician intentions to implement specific cognitive-behavioral therapy components. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Valderrama A, Mena C, Undurraga J, Gallardo C, Mondaca P. Implementing psychosocial evidence-based practices in mental health: are we moving in the right direction? Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker-Haimes EM, Lushin V, Creed TA, Beidas RS. Characterizing the heterogeneity of clinician practice use in community mental health using latent profile analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau AS, Gonzalez JC, Barnett ML, Kim JJ, Saifan D, Brookman-Frazee L. Community therapist reports of client engagement challenges during the implementation of multiple EBPs in children’s mental health. Evid Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;3:197–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayer NA, Kaplan A, Nelson DB, Stirman SW, Rosen CS. Clinician burnout and effectiveness of guideline-recommended psychotherapies. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e246858–e246858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creed TA, Frankel SA, German RE, Green KL, Jager-Hyman S, Taylor KP, et al. Implementation of transdiagnostic cognitive therapy in community behavioral health: the Beck Community Initiative. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:1116–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackburn I-M, James IA, Milne DL, Baker C, Standart S, Garland A, et al. The revised cognitive therapy scale (cts-r): psychometric properties. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:431–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg SB, Baldwin SA, Merced K, Caperton DD, Imel ZE, Atkins DC, et al. The structure of competence: evaluating the factor structure of the cognitive therapy rating scale. Behav Ther. 2020;51:113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Collins JF, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:971–82 discussion 983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallis TM, Shaw BF, Dobson KS. The cognitive therapy scale: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stamm B. The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale. 2010. Available: https://www.academia.edu/download/62440629/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-201020200322-88687-17klwvb.pdf

- 17.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6:61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2017.

- 19.Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth mixture modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;33:565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2:302–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peel D, MacLahlan G. Finite mixture models. New York: Wiley; 2000;452.

- 22.Germer S, Weyrich V, Bräscher A-K, Mütze K, Witthöft M. Does practice really make perfect? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between therapist experience and therapy outcome: a replication of Goldberg, Rousmaniere, et al. (2016). J Couns Psychol. 2022. 10.1037/cou0000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg SB, Rousmaniere T, Miller SD, Whipple J, Nielsen SL, Hoyt WT, et al. Do psychotherapists improve with time and experience? A longitudinal analysis of outcomes in a clinical setting. J Couns Psychol. 2016;63(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams NJ, Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Marcus SC, Beidas RS. Linking molar organizational climate and strategic implementation climate to clinicians’ use of evidence-based psychotherapy techniques: cross-sectional and lagged analyses from a 2-year observational study. Implement Sci. 2018;13: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker-Haimes EM, Mandell DS, Fishman J, Williams NJ, Wolk CB, Wislocki K, et al. Assessing causal pathways and targets of implementation variability for EBP use (Project ACTIVE): a study protocol. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldsmith ES, Koffel E, Ackland PE, Hill J, Landsteiner A, Miller W, Stroebel B, Ullman K, Wilt TJ, Duan-Porter W. Evaluation of implementation strategies for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(12):2782–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creed TA, Salama L, Slevin R, Tanana M, Imel Z, Narayanan S, Atkins DC. Enhancing the quality of cognitive behavioral therapy in community mental health through artificial intelligence generated fidelity feedback (Project AFFECT): a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1): 1177. 10.1186/s12913-022-08519-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to being associated with therapy recordings and protected by HIPAA.