Abstract

Background

Depression significantly impacts health systems worldwide, particularly in Latin America, where cultural stigmatization and misconceptions about mental health deter individuals from seeking help. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward depression may affect its prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

Objective

To categorize Latin American healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards diagnosis and management of depression in subgroups using the Spanish-validated Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (SR-DAQ).

Methods

A cross-sectional study surveyed 2,409 professionals using SR-DAQ from 2019 to 2022. Latent class analysis and multinomial logistic regression were used to identify attitude classes and explore demographic influences.

Results

Among our sample, four attitude classes were identified: Depression Skeptics (21%), Depression Cautious (33%), Depression Neutrals (18%), and Depression Advocates (28%). Gender and medical subspecialty significantly influenced class membership, with females and mental health specialists more likely to be part of the Advocates.

Conclusion

The study reveals varied attitudes towards depression among Latin American healthcare professionals, suggesting the need for tailored public health strategies to enhance effective depression care and management.

Keywords: Depression, Latent class analysis, Healthcare, Attitudes, SR-DAQ

Introduction

Depression significantly impacts global public health, with profound effects in Latin America, where cultural, socioeconomic, and political factors heighten stress and trauma risks, exacerbating depression’s prevalence and severity [1, 2]. Cultural stigmatization and misconceptions about mental health deter individuals from seeking help, worsening outcomes [3, 4]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that over one-third of adults in Latin America show depressive symptoms, predominantly among women and urban dwellers, with depression ranking as a leading disability cause in the region [5, 6].

Despite its heavy toll, depression remains under-diagnosed and under-treated, partly due to healthcare professionals’ dismissive attitudes towards mental health issues, often perceived as personal failings rather than medical conditions [7]. According to surveys conducted in Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela, 70% of healthcare professionals express a preference for managing somatic illnesses over mental illnesses, and a significant number of them are skeptical of the effectiveness of medical or psychosocial treatments for depression [8].

The Spanish-validated Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (SR-DAQ) serves as a critical tool for assessing attitudes towards depression within this demographic [8–10]. However, attitudes are complex, influenced by various factors at multiple levels, making their analysis particularly challenging in large, diverse groups [11, 12].

To address these complexities, latent class analysis (LCA) offers a robust statistical method that identifies homogenous subgroups within heterogeneous data, revealing distinct behavioral and response patterns among individuals [13, 14]. This approach enables the identification of specific attitude profiles among medical professionals, facilitating the development of targeted educational interventions and training programs tailored to improve mental health knowledge and attitudes within medical education, such as previous effective interventions applied in family physicians in the US that could be extrapolated to Latin America and other regions [15].

This study aims to identify distinct subgroups of attitudes towards depression among physicians across multiple Latin American countries. By analyzing the unique challenges these professionals face, we can develop tailored interventions that enhance the effectiveness of depression diagnosis and treatment. Understanding these attitudes will help to improve mental health training programs, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and a reduction in the stigma associated with depression.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted among healthcare professionals in Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela using the Spanish version of the Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ). The R-DAQ is a validated tool designed to assess healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards depression, including their comfort in dealing with depressed patients, beliefs about the causes and treatments of depression, and perceptions of their professional role in managing depression [16].

The data were collected at two different time points: the first quarter of 2019 and from August to November 2022. This temporal difference was due to the fact that the data used to create this latent class analysis originated from two separate studies that had already been published [8, 10]. While the potential influence of temporal differences on the outcomes cannot be entirely ruled out, the study design accounted for this by evaluating the consistency of class distributions and response patterns across both time points before pooling the data. Moreover, the consistency of findings across both time periods suggests that the results are robust despite the different collection times.

Data collection

We distributed the questionnaire to healthcare professionals via electronic listings, email, and social networking sites. The participants had to be active healthcare professionals (physicians or psychologists) residing in Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela to meet the inclusion criteria. The research team preserved anonymity and protected the data by keeping participants’ names confidential. Primary researchers and statisticians had access to the data, but they only used it to examine distinct classes of attitudes toward depression.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic data included sex, country of residence, medical specialty, location of practice (rural, urban, or both), and prior participation in depression training. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the healthcare professionals

| Variable | Percent |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 62.24%) |

| Male | 37.76%) |

| Specialty | |

| Health | 16.18% |

| Surgical | 13.24% |

| Non-surgical | 70.58% |

| Location of practice | |

| Both | 11.70% |

| Rural | 13.60% |

| Urban | 74.70% |

| Depression training | |

| No | 64.55% |

| Yes | 35.45% |

| Country | |

| Argentina | 21.59% |

| Chile | 21.54% |

| Ecuador | 24.58% |

| Peru | 11.80% |

| Venezuela | 20.51% |

Attitudes

A five-point Likert Scale was initially employed to gauge agreement with the twenty-one statements related to attitudes toward depression from the SR-DAQ. For simplicity, this scale was condensed into a two-point format. “Agree” and “Totally agree” responses were combined to indicate agreement with the respective statement. Table 2 presents the percentage of agreement for each statement.

Table 2.

Agreement on attitudes towards depression

| Agreement with statement | Percent |

|---|---|

| 1. I feel comfortable in dealing with depressed patients’ needs. | 43.28% |

| 2. Depression is a disease like any other (e.g., asthma, diabetes). | 70.53% |

| 3. Psychological therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. | 14.84% |

| 4. Antidepressant therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. | 4.48% |

| 5. One of the main causes of depression is a lack of self-discipline and will-power. | 20.81% |

| 6. Depression treatments medicalize unhappiness. | 27.10% |

| 7. I feel confident in assessing depression in patients. | 46.32% |

| 8. I am more comfortable working with physical illness than with mental. | 63.52% |

| 9. Becoming depressed is a natural part of being old. | 6.60% |

| 10. All health professionals should have skills in recognizing and managing. | 87.74% |

| 11. My profession is well placed to assist patients with depression. | 45.54% |

| 12. Becoming depressed is a way that people with poor stamina deal with life. | 23.08% |

| 13. Once a person has made up their mind about taking their own life no one can stop them. | 8.50% |

| 14. People with depression have care needs similar to other medical conditions. | 69.60% |

| 15. My profession is well trained to assist patients with depression. | 33.85% |

| 16. Recognizing and managing depression is often an important part of managing other health problems. | 82.07% |

| 17. I feel confident in assessing suicide risk in patients presenting with depression. | 36.12% |

| 18. It is rewarding to spend time looking after depressed patients. | 39.62% |

| 19. Becoming depressed is a natural part of adolescence. | 5.77% |

| 20. There is little to be offered to depressed patients who do not respond to initial treatments. | 11.90% |

| 21. Anyone can suffer from depression. | 88.98% |

Data analyses

For this research, we employ a three-step Latent Class Analysis (LCA) approach, which begins with model specification, where the number of latent classes is determined and the initial model is set up based on theoretical and empirical insights [17]. Subsequently, the model parameters are estimated, leading to the creation of distinct groups based on the patterns in the data. The final step involves the interpretation of these groups and, importantly, the use of multinomial logistic regression to examine the relationship between class membership and external variables, allowing for a deeper understanding of the factors that influence group distinctions.

First, a Latent Class Analysis was conducted to determine the optimal number of classes using Akaike Information Criterion values, Bayesian Information Criteria, and entropy statistics, as detailed in Table 3. The analysis favored a four-class model, as evidenced by the entropy statistic’s decline at this class number, followed by an increase for higher class counts and lesser reductions in other metrics. Subsequently, a multinomial logistic regression was performed on these four classes, with “Depression Neutrals” as the reference category. This regression analyzed the odds of class membership influenced by variables such as sex (“female” as the reference), country of residence (“Argentina” as the reference), medical specialty (“mental health” as the reference), location of practice (“both” as the reference), and prior depression training (“No” as the reference). For clarity, the regression’s relative risk ratios are detailed in the appendix, while the main text simplifies the presentation by focusing on the predicted probabilities or margins of each variable’s association with class membership. All analyses were executed using Stata 17.0 and Microsoft Excel (for the graphs).

Table 3.

Model fit

| Classes | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40622.58 | 40739.57 | 0 |

| 2 | 34193.14 | 34432.69 | 0.929 |

| 3 | 32952.59 | 33314.70 | 0.865 |

| 4 | 31859.69 | 32344.36 | 0.859 |

| 5 | 31374.84 | 31976.50 | 0.867 |

| 6 | 30997.35 | 31727.14 | 0.862 |

| 7 | 30742.52 | 31594.88 | 0.855 |

| 8 | 30551.96 | 31526.87 | 0.858 |

| 9 | 30285.11 | 31371.45 | 0.864 |

| 10 | 30160.09 | 31368.99 | 0.862 |

| 11 | 30134.64 | 31477.24 | 0.849 |

Ethics statement

The study complied with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the ethics committee: Comité de ética e Investigación en Seres Humanos (CEISH), Guayaquil-Ecuador (#HCK-CEISH-18-0060). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to their voluntary participation in the survey.

Results

Latent class analysis

Based on the attitudes towards depression included in the Latent Class Analysis, four different subgroups were identified (Table 4): Class 1: “Depression Skeptics” (PR = 0.21), Class 2: “Depression Cautious” (PR = 0.33), Class 3: “Depression Neutrals” (PR = 0.18), and Class 4: “Depression Advocates” (PR = 0.28).

Table 4.

Probability of each class

| Delta-method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margin | Std. Error | [95% conf. interval] | ||

| Class | ||||

| 1: “Depression Skeptics” | 0.21297 | 0.01510 | 0.18488 | 0.24406 |

| 2: “Depression Cautious” | 0.32590 | 0.01731 | 0.29293 | 0.36069 |

| 3: “Depression Neutrals” | 0.17902 | 0.01344 | 0.15417 | 0.20690 |

| 4: “Depression Advocates” | 0.28211 | 0.01285 | 0.25762 | 0.30796 |

In this way, the agreement with each statement from the questionnaire varied depending on which class responded to that statement, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Agreement with statements according to four classes

| Agreement with statement | Depression skeptics | Depression cautious | Depression neutrals | Depression advocates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel comfortable in dealing with depressed patients’ needs. | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.53 | 0.94 |

| 2. Depression is a disease like any other (e.g., asthma, diabetes). | 0.34 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.92 |

| 3. Psychological therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| 4. Antidepressant therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| 5. One of the main causes of depression is a lack of self-discipline and will-power. | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.02 |

| 6. Depression treatments medicalize unhappiness. | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.04 |

| 7. I feel confident in assessing depression in patients. | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.97 |

| 8. I am more comfortable working with physical illness than with mental. | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.22 |

| 9. Becoming depressed is a natural part of being old. | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| 10. All health professionals should have skills in recognizing and managing. | 0.58 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| 11. My profession is well placed to assist patients with depression. | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.98 |

| 12. Becoming depressed is a way that people with poor stamina deal with life. | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| 13. Once a person has made up their mind about taking their own life no one can stop them. | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| 14. People with depression have care needs similar to other medical conditions. | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.93 |

| 15. My profession is well trained to assist patients with depression. | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.87 |

| 16. Recognizing and managing depression is often an important part of managing other health problems. | 0.34 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.99 |

| 17. I feel confident in assessing suicide risk in patients presenting with depression. | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.52 | 0.90 |

| 18. It is rewarding to spend time looking after depressed patients. | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.83 |

| 19. Becoming depressed is a natural part of adolescence. | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| 20. There is little to be offered to depressed patients who do not respond to initial treatments. | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| 21. Anyone can suffer from depression. | 0.71 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.98 |

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for each of the four latent classes—Depression Skeptics, Depression Cautious, Depression Neutrals, and Depression Advocates—based on their levels of agreement with 21 statements about depression. These statements capture attitudes toward the nature of depression, its causes, treatment effectiveness, professional responsibility, and personal confidence in managing depressive patients. Each cell shows the probability of agreement within each class, offering insight into the defining beliefs and clinical orientations of each group.

The Depression Skeptics class stands out for its consistently low agreement with medical and psychosocial understandings of depression. Only 34% believe depression is a disease like asthma or diabetes, and just 12% agree that patients with depression have similar care needs as those with other conditions. This class exhibits very low self-confidence in clinical tasks such as assessing depression (13%) or suicide risk (1%) and minimal endorsement of professional responsibility (1% believe their profession is well placed to help). Skeptics are also the most likely to endorse stigmatizing views, with 54% attributing depression to poor stamina and 58% viewing treatment as medicalizing unhappiness. They show a clear preference for working with physical illness (89%) and rarely find caring for depressed patients rewarding (11%).

The Depression Cautious group exhibits partial endorsement of biomedical and professional roles in depression care but low personal confidence. While 79% recognize depression as a disease and 97% believe all professionals should have relevant skills, only 19% feel confident assessing depression, and just 4% feel capable of evaluating suicide risk. This group strongly prefers physical illness (91%) and exhibits moderate skepticism toward causes and treatments—for example, 16% attribute depression to weak will-power and 13% believe treatments medicalize unhappiness. Their low sense of readiness is underscored by just 3% agreeing their profession is well trained. These respondents may conceptually accept mental health care responsibilities but lack the tools or training to act effectively.

The Depression Neutrals display a mix of supportive and stigmatizing beliefs. They moderately agree that depression is a disease (65%) and that all professionals should manage it (89%), and they report mid-range confidence in assessment (56%) and suicide risk evaluation (52%). However, this class also shows the highest agreement with individualistic attributions: 61% believe depression stems from lack of will-power, 52% see treatments as medicalizing unhappiness, and 42% feel there is little to offer non-responders. Their preference for physical illness is less pronounced (48%) compared to Skeptics and Cautious respondents. This group appears ideologically and clinically ambivalent, straddling between outdated beliefs and professional engagement.

The Depression Advocates class is marked by strong agreement with medical, psychosocial, and professional perspectives on depression. Nearly all respondents in this class agree that depression is a disease (92%) and that it affects anyone (98%). They report very high confidence in assessing both depression (97%) and suicide risk (90%) and are overwhelmingly positive about their profession’s preparedness (87% believe it is well trained). Advocates strongly reject stigma, with just 2% attributing depression to lack of self-discipline or stamina and only 4% believing treatments medicalize unhappiness. They are the least likely to prefer physical illness (22%) and find caring for depressed patients highly rewarding (83%). This group reflects a fully engaged, confident, and destigmatized approach to depression care.

Multinomial logistic regression results

A Multinomial Logistic Regression model was estimated for the four detected classes, with the relative risk ratios presented in the appendix. Following this, we display the adjusted margins at the means for each level within each variable by the latent class. For simplicity, these were interpreted as the percentage likelihood of belonging to each latent class, considering that they were already adjusted for the other confounders in the multinomial regression.

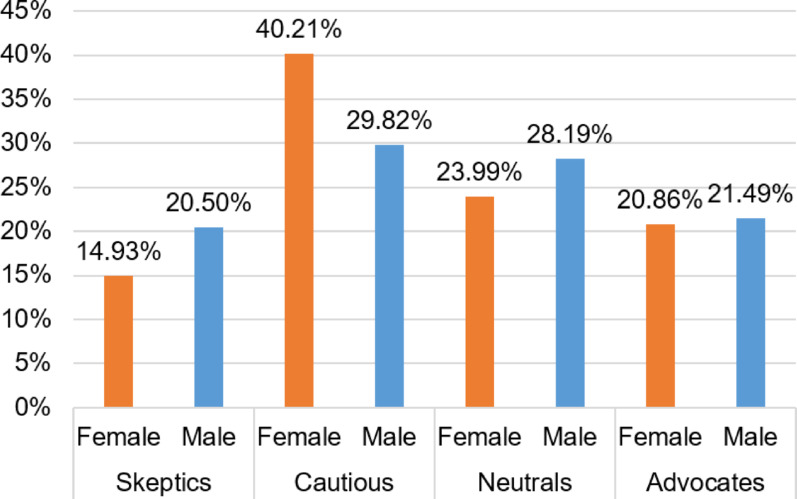

Among the female respondents, 40.21% belonged to Cautious, 23.99% were Neutrals, 20.86% were Advocates, and 14.93% belonged to Skeptics (Fig. 1). Similarly, among male participants, 29.82% were Cautious, 28.19% were Neutrals, 21.49% were Advocates, and 20.50% were Skeptics.

Fig. 1.

Adjusted predictions for sex by latent class

Among mental health specialists, 80.93% were Advocates, 14.69% Neutrals, 2.54% Skeptics, and 1.83% Cautious (Fig. 2). In contrast, surgical specialists were predominantly Cautious (44.24%), followed by Skeptics (32.28%), Neutrals (22.24%), and Advocates (1.25%). Non-surgical specialists were mostly Cautious (46.38%), with Neutrals (20.14%), Advocates (17.89%), and Skeptics (15.59%) making up the rest.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted predictions for specialty by latent class

Distribution of specialists’ attitudes by category. Mental Health includes specialties such as psychiatry, psychology, and related fields. Non-Surgical refers to specialties including internal medicine, pediatrics, and other non-surgical disciplines.

Among workers in rural and urban areas, 37.20% belonged to Cautious, 26.88% were Neutrals, 22.33% were Advocates, and 13.59% were Skeptics (Fig. 3). Similarly, 37.43% of workers in urban areas belonged to Cautious, 24.54% were Neutrals, 21.10% were Advocates, and 16.93% were Skeptics. However, among workers in rural areas, 30.86% belonged to neutrals, 28.48% were cautious, 20.61% were advocates, and 20.05% belonged to skeptics.

Fig. 3.

Adjusted predictions for area by latent class

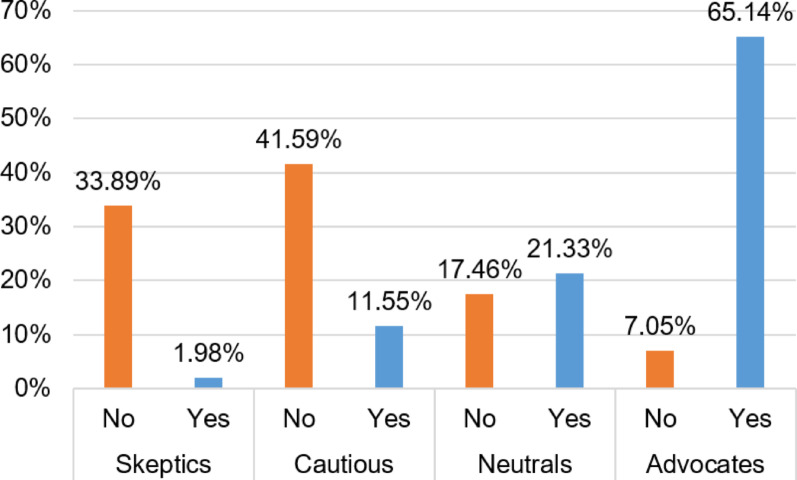

Among participants in pre-training on depression, 65.14% belonged to advocates, 21.33% belonged to neutrals, 11.55% were cautious, and 1.98% were skeptics (Fig. 4). On the contrary, among non-participants in pre-training on depression, 41.59% belonged to Cautious; 33.89%, Skeptics; 17.46%, Neutrals; and 7.05%, Advocates.

Fig. 4.

Adjusted predictions for depression training by latent class

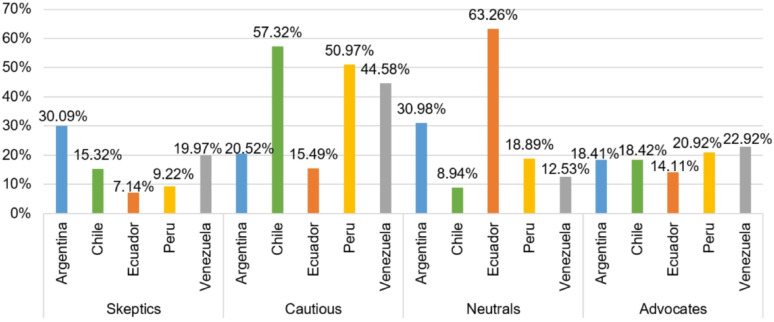

Among Argentinian respondents, 30.98% belonged to Neutrals; 30.09%, Skeptics; 20.52%, Cautious; and 18.41%, Advocates (Fig. 5). In contrast, among Chilean respondents, 57.32% were Cautious, 18.42% were Advocates, 15.32% were Skeptics, and 8.94% were Neutrals. Similarly, among Venezuelan respondents, 44.58% were Cautious, 22.92% were Advocates, 19.97% were Skeptics, and 12.53% were Neutrals. On the other hand, Among Ecuadorian respondents, 63.26% belonged to Neutrals; 15.49%, Cautious; 14.11%, Advocates; and, 7.14%, Skeptics. Finally, among Peruvian respondents, 50.97% were Cautious, 20.92% were Advocates, 18.89% were Neutrals, and 9.22% were Skeptics.

Fig. 5.

Adjusted predictions for country by latent class.

Discussion

Despite extensive research on depression, there is still a lack of effective public health strategies to foster positive attitudes toward it. Recent studies highlight a global deficiency in understanding diverse physician perspectives on depression [18–21]. Our analysis of 2,409 health professionals from five Latin American countries identified four main attitude profiles toward depression.

Skeptical Healthcare Workers doubt the legitimacy of depression as a medical condition, often reflecting stigmatized views previously documented in global studies [22, 23]. In Japan, non-psychiatric doctors’ reluctance to treat depression underscores widespread skepticism about its manageability [24]. Such skepticism is more prevalent among rural and less-educated healthcare workers.

Cautious Healthcare Workers exhibit mixed beliefs, recognizing depression’s seriousness yet doubting the effectiveness of psychological therapies. This caution is distinct from the skepticism observed in some healthcare professionals who more strongly doubt the efficacy of these treatments. Distinguishing between ‘skeptical’ and ‘cautious’ attitudes is important for tailoring educational interventions. While skeptics may require robust evidence to overcome their doubts, cautious individuals might benefit from reassurance and confidence-building measures. Addressing these differences can enhance the effectiveness of education by directly targeting the specific concerns and needs of each group. This skepticism is echoed in studies suggesting that the broader medical and non-medical communities are skeptical about the efficacy of pharmacological treatments [16, 25].

Neutral Healthcare Workers balance acceptance and skepticism about depression. They recognize its importance but are uncertain about treatment effectiveness, reflecting a need for better training in mental health 10,25. These attitudes align with a broader discomfort in dealing with mental illnesses compared to physical ones, especially in regions like Chile, Argentina, and Venezuela [8].

Advocate Healthcare Workers fully recognize depression as a medical condition, emphasizing the necessity of proper diagnosis and management. Their views are supported by international studies, showing varied but generally positive attitudes towards managing depression effectively [26, 27].

The emerging classes reflects an interpretative synthesis of the distinctive characteristics observed in each group after the data analysis, and, although previous studies have used categories focused on specific dimensions, such as, “professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, or a generalist perspective” on depression [28], our approach is intuitively determined by the overall attitudes and practical positioning observed in participants of our study.

Multinomial logistic regression shows that gender and specialty significantly impact healthcare workers’ attitudes towards depression. Female providers and mental health specialists are more likely to be advocates for recognizing depression as a medical condition, suggesting that specialized training enhances empathy and knowledge. In contrast, male providers and those in non-mental health specialties often display skepticism or caution, reflecting a need for broader mental health education in all medical training. Our findings also reveal that healthcare professionals in Latin America exhibit varied attitudes towards depression, significantly impacting clinical practice. Similar to previous research [29], primary care physicians in our study often display stigmatizing attitudes, preferring to refer patients to specialists rather than manage mental health issues themselves. This reluctance, especially among male healthcare workers and those in non-mental health specialties, underscores the need for broader mental health education [29].

We considered the possibility that differences in class membership across countries could be driven by the proportion of mental health professionals in each national sample. To discard any sample compositional bias, we ran additional bivariate analysis examining the relationship between country and class distribution alongside the proportion of mental health specialists. Although there are notable differences in class membership across countries, our analysis suggests that these are not explained by the distribution of mental health professionals. Countries with similar proportions of mental health specialists exhibit distinct class patterns—for instance, Argentina and Ecuador both have relatively low shares of mental health professionals but differ significantly in the prevalence of Skeptics and Neutrals. Similarly, Peru and Venezuela have comparable mental health representation but differ in their proportions of Cautious and Advocate respondents. These findings indicate that factors beyond professional specialty—such as national context, institutional norms, or training quality—likely play a more central role in shaping attitudes toward depression.

Although our survey did not collect participants’ age or years of practice, generational differences likely influence attitudes toward depression. A systematic review of primary care providers found that older, more experienced doctors often hold more stigmatizing views of mental illness compared to their younger colleagues [30]. This gap likely reflects differences in training and socialization, as many physicians – especially those from earlier cohorts – report needing better preparation to handle mental health issues [30]. In the absence of direct age data, we would expect that younger, recently trained practitioners might be disproportionately represented in the “Depression Advocates” class, while older, long-tenured providers may be more prone to “Skeptical” or “Cautious” attitudes.

Again, our Latent Class Analysis identified four distinct profiles: “Depression Skeptics,” “Depression Cautious,” “Depression Neutrals,” and “Depression Advocates,” mirroring findings that lower mental health literacy and inadequate training lead to poorer outcomes [30]. “Skeptical Healthcare Workers” showed the lowest agreement with recognizing depression, consistent with reports of stigmatizing views linked to less training [30]. Conversely, “Advocate Healthcare Workers” displayed high agreement with depression management, highlighting the positive impact of specialized training. Geographical and socioeconomic factors also influence these attitudes, with rural workers exhibiting more skepticism due to limited resources and cultural stigmas.

The identified subgroups and their correlates represent a crucial starting point for guiding targeted interventions to effectively address stigma-related barriers and improve depression care in Latin America. Generalized interventions might unlikely succeed, so target specific measures should be applied to be able to develop public health strategies that promote educational programs among skeptical and neutral individuals, which can play a pivotal role in reducing barriers arising from differing attitudes toward depression. Notably, several high-income countries have cultivated healthcare provider attitudes akin to our “Depression Advocates” profile through deliberate national strategies. For example, in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, sustained anti-stigma initiatives (e.g. the “Time to Change” campaign in England, Canada’s Opening Minds program, and Australia’s beyondblue) combined with enhanced mental health training have fostered medicalized, non-judgmental views of depression among clinicians [31]. Providers in these settings widely recognize depression as a treatable medical condition (rather than a personal failing) and report high confidence in managing it within primary care [32]. Likewise, countries such as the Netherlands and Australia have implemented collaborative care models and continuing education that embed mental health expertise into primary care teams, further reinforcing clinicians’ comfort in treating depression (by 2015, 88% of Dutch general practices had an on-site mental health nurse supporting depression carebmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com). Adapting these approaches to Latin American contexts is feasible but requires cultural and resource-specific modifications [33]. For instance, anti-stigma campaigns and trainings must be tailored to local beliefs (addressing the notion in some Latin cultures that depression stems from personal weakness) and scaled to available resources – leveraging task-sharing, brief training modules, and community health workers to offset specialist shortagespmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. This integrative paragraph would fit well near the end of the Discussion section, following the description of our latent classes, to contextualize how lessons from high-income countries could inform strategies for shifting Latin American providers toward being “Depression Advocate” stance [31].

To effectively address the different attitudes and structural barriers identified in our analysis, we propose a series of targeted educational and training interventions. First, mandatory mental health training modules should be implemented for all healthcare professionals, with particular focus on non-mental health specialists, to strengthen their capacity to recognize and manage depression. This would directly address the widespread lack of knowledge and confidence observed among skeptical and cautious providers. In addition, incorporating cultural competency training is essential to confront local stigmas and traditional gender roles that influence mental health attitudes, especially in rural areas where such norms are often more deeply rooted. Integrating collaborative care models—where mental health specialists support primary care physicians—can further aid cautious providers by improving their ability and confidence to manage depression in routine practice. Establishing peer support networks would also enable healthcare workers to share challenges and best practices, fostering collegial reinforcement for more empathetic and informed care. Moreover, ongoing professional development initiatives focused on up-to-date mental health treatments can help those in the neutral and cautious profiles gradually shift toward an advocate-like stance. Finally, the implementation of routine assessments to track providers’ attitudes over time would support the adaptive refinement of educational strategies and contribute to overall improvements in the quality of mental health care.

Study limitations

The nature of the study may have influenced the development of the latent class analysis, generating several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents us from inferring how attitudes may change over time, which could lead individuals to shift between latent classes. The online distribution of the survey could have introduced selection bias, potentially overrepresenting certain groups. Additionally, temporal differences in data collection across the two study periods may have affected outcomes, although we applied statistical controls to assess the consistency of class distributions. As with most survey-based research, the use of self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall and social desirability biases. The uneven distribution of medical specialties and gender in the sample may also limit the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, latent class analysis depends on model assumptions and results may vary with different specifications determined by the researcher. Finally, a technical error during data collection prevented the consistent recording of participants’ age, limiting our ability to assess generational effects. Nonetheless, we expect that age may influence attitudes through differences in mental health literacy, exposure to training, and evolving cultural norms around the medicalization of psychological distress, which could shape how depression is perceived and managed in clinical practice.

Further research

While this study offers a novel classification of healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward depression in Latin America, it also opens important avenues for future research. First, incorporating age and years of professional experience in future surveys would allow for a more precise analysis of how generational factors shape attitudes—a limitation noted in our current dataset. Second, qualitative studies could deepen understanding of the contextual reasons behind class membership, especially in countries with contrasting patterns. Finally, intervention studies are needed to evaluate whether targeted training programs, anti-stigma campaigns, or collaborative care models can effectively shift providers from skeptical or neutral profiles toward a more advocate-oriented stance. Longitudinal designs would be particularly valuable to assess whether attitudinal changes among healthcare workers translate into improved depression care and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

This study identified four distinct attitude profiles toward depression among healthcare professionals in five Latin American countries, revealing substantial variation in how depression is perceived and managed across demographic and professional subgroups. Notably, gender, specialty, training, and country of residence significantly influenced class membership, with mental health training emerging as a key factor in fostering more favorable attitudes. These findings underscore the urgent need for tailored educational strategies and policy interventions to improve mental health literacy, reduce stigma, and enhance depression care across the region. By addressing the specific concerns of each subgroup, particularly Skeptical and Cautious professionals, health systems can better equip providers to recognize and manage depression, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Evana Pina and Dr. Rey Varela for their assistance during data collection. We also thank Dr. Jesus Guarecuco and Dr. Freddy Pachano Arenas for their ongoing assistance with our research.

Author contributions

Marco Faytong-Haro: Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision Genesis Camacho-Leon: Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision Robert Araujo-Contreras: Writing – Original Draft Stephanie Gallegos: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation Hans Mautong: Writing – Original Draft Karla Robles-Velasco: Writing – Original Draft Romina Dominguez: Writing – Review & Editing Andrea Mendez Colmenares: Writing – Original Draft Ricardo Noriega: Writing – Original Draft Keila Carrera Mejias: Writing – Review & Editing Fernando Peña: Writing – Review & Editing Guillermo Leon-Samaniego: Writing – Review & Editing Claudia Reytor-González: Writing – Review & Editing Cristina Núñez-Vásquez: Writing – Review & Editing Ivan Cherrez-Ojeda: Writing – Review & Editing Daniel Alejandro Simancas-Racines: Writing – Review & Editing.

Funding

This work was funded by the authors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethicals and approved by the ethics committee of Comité de ética e Investigación en Seres Humanos (CEISH), Guayaquil-Ecuador (#HCK-CEISH-18-0060).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marco Faytong-Haro, Email: mfaytongh@unemi.edu.ec.

Daniel Alejandro Simancas-Racines, Email: dsimancas@ute.edu.ec.

References

- 1.Drinot P, Knight A. The Great Depression in Latin America [Internet]. Duke University Press; 2014 [cited 2024 Apr 11]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=es&lr=&id=xDwiBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT5&dq=the+great+depression+in+latin+america&ots=QpLj-jrdv_&sig=2NnMnS8E-MLuS3Co-uI0uOe1W9E

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Depressive disorder (depression). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- 3.Hirai M, Dolma S, Vernon LL, Clum GA. Beliefs about mental illness in a Spanish-speaking Latin American sample. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of the Surgeon General (US), Center for Mental Health Services (US), National Institute of Mental Health (US). Chapter 2 Culture Counts: The Influence of Culture and Society on Mental Health. In: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2001 [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44249/ [PubMed]

- 5.Pan American Health Organization. The Burden of Mental Disorders in the Region of the Americas, 2018 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2018 [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/49578/9789275120286_eng.pdf?sequence=10&isAllowed=y

- 6.Zhang SX, Batra K, Xu W, Liu T, Dong RK, Yin A, et al. Mental disorder symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2022;31:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascayano F, Tapia T, Schilling S, Alvarado R, Tapia E, Lips W, et al. Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the caribbean: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2016;38(1):73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho-Leon G, Faytong-Haro M, Carrera K, De la Hoz I, Araujo-Contreras R, Roa K et al. Attitudes towards depression of Argentinian, Chilean, and Venezuelan healthcare professionals using the Spanish validated version of the revised depression attitude questionnaire (SR-DAQ). SSM Popul Health [Internet]. 2022 Aug 6 [cited 2024 Mar 22];19:101180. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9365952/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Cherrez-Ojeda I, Haddad M, Vera Paz C, Valdevila Figueira JA, Fabelo Roche J, Orellana Román C et al. Spanish Validation Of The Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ). Psychol Res Behav Manag [Internet]. 2019 Nov 13 [cited 2024 Mar 22];12:1051–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6859125/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Valdevilla Figueira JA, Mautong H, Camacho LG, Cherrez M, Orellana Román C, Alvarado-Villa GE, et al. Attitudes toward depression among Ecuadorian physicians using the Spanish-validated version of the revised depression attitude questionnaire (R-DAQ). BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kernan JB, Trebbi GG Jr. Attitude dynamics as a hierarchical structure. J Soc Psychol. 1973;89(2):193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petty RE, Wegener DT. Attitude change: multiple roles for persuasion variables. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology, vols 1–2. 4th ed. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 323–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kongsted A, Nielsen AM. Latent class analysis in health research. J Physiother. 2017;63(1):55–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang WC, Worsley A, Hodgson V. Classification of main meal patterns–a latent class approach. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(12):2285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzanera R, Lahera G, Álvarez-Mon MÁ, Alvarez-Mon M. Maintained effect of a training program on attitudes towards depression in family physicians. Family Practice [Internet]. 2018 Jan 16 [cited 2025 Jul 13];35(1):61–6. 10.1093/fampra/cmx071 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Haddad M, Menchetti M, Walters P, Norton J, Tylee A, Mann A. Clinicians’ attitudes to depression in Europe: a pooled analysis of Depression Attitude Questionnaire findings. Fam Pract [Internet]. 2012 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Mar 22];29(2):121–30. 10.1093/fampra/cmr070 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Choi HJ, Weston R, Temple JR. A three-step latent class analysis to identify how different patterns of teen dating violence and psychosocial factors influence mental health. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:854–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldahmashi T, Almanea A, Alsaad A, Mohamud M, Anjum I. Attitudes towards depression among non-psychiatric physicians in four tertiary centres in Riyadh. Health Psychol Open. 2019;6(1):2055102918820640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppens E, Van Audenhove C, Scheerder G, Arensman E, Coffey C, Costa S et al. Public attitudes toward depression and help-seeking in four European countries baseline survey prior to the OSPI-Europe intervention. Journal of Affective Disorders [Internet]. 2013 Sep 5 [cited 2024 Mar 22];150(2):320–9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032713002826 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kobau R, Zack M, Luncheon C, Barile J, Marshall C, Bornemann T et al. Attitudes toward mental illness: results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22179

- 21.Stubbe DE. Doctor-Patient communication: A global perspective. Focus. 2015;13(4):453–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbatia J, Shah A, Jenkins R. Knowledge, attitudes and practice pertaining to depression among primary health care workers in Tanzania. Int J Ment Health Syst [Internet]. 2009 Feb 25 [cited 2024 Mar 22];3:5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2652424/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mulango ID, Atashili J, Gaynes BN, Njim T. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding depression among primary health care providers in Fako division, Cameroon. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 Mar 13 [cited 2024 Mar 22];18(1):66. 10.1186/s12888-018-1653-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Ohtsuki T, Kodaka M, Sakai R, Ishikura F, Watanabe Y, Mann A et al. Attitudes toward depression among Japanese non-psychiatric medical doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes [Internet]. 2012 Aug 16 [cited 2024 Mar 22];5(1):441. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). HMP Global Learning Network. 2012 [cited 2024 Mar 22]. CDC, SAMHSA study: Most Americans believe mental health treatment leads to “normal life”. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/behavioral/article/cdc-samhsa-study-most-americans-believe-mental-health-treatment-leads-normal-life

- 26.Duric P, Harhaji S, O’May F, Boderscova L, Chihai J, Como A, GENERAL PRACTITIONERS’ VIEWS TOWARDS DIAGNOSING AND TREATING DEPRESSION IN FIVE SOUTH-EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES. Early Interv Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2024 Mar 22];13(5):1155–64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6445789/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Liu Z, Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Liang L, Wang Y et al. Latent class analysis of depression and anxiety among medical students during COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Oct 12 [cited 2024 Mar 22];21(1):498. 10.1186/s12888-021-03459-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Haddad M, Menchetti M, McKeown E, Tylee A, Mann A. The development and psychometric properties of a measure of clinicians’ attitudes to depression: the revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ). BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2015 Feb 5 [cited 2022 Jun 21];15(1):7. 10.1186/s12888-014-0381-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Vistorte AOR, Ribeiro W, Ziebold C, Asevedo E, Evans-Lacko S, Keeley JW et al. Clinical decisions and stigmatizing attitudes towards mental health problems in primary care physicians from Latin American countries. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018 Nov 15 [cited 2023 Feb 16];13(11):e0206440. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6237310/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Vistorte AOR, Ribeiro WS, Jaen D, Jorge MR, Evans-Lacko S, de Mari J. Stigmatizing attitudes of primary care professionals towards people with mental disorders: A systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2018;53(4):317–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajizadeh A, Amini H, Heydari M, Rajabi F. How to combat stigma surrounding mental health disorders: a scoping review of the experiences of different stakeholders. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 Nov 8 [cited 2025 Jul 13];24:782. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11549754/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Lam TP, Sun KS, Piterman L, Lam KF, Poon MK, See C, et al. Impact of training for general practitioners on their mental health services. Australian J Gen Pract. 2018;47(8):550–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paniagua-Avila A, Branas C, Susser E, Fort MP, Shelton R, Trigueros L et al. Integrated programs for common mental illnesses within primary care and community settings in Latin America: a scoping review of components and implementation strategies. Lancet Reg Health Am [Internet]. 2024 Dec 7 [cited 2025 Jul 13];41:100931. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11665371/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.