Abstract

Pulmonary cryptococcosis is an opportunistic infection of the lungs caused by cryptococcus, usually occurring in immunosuppressed patients. Pulmonary embolism is a type of venous thromboembolism. Pregnancy and postpartum are risk factors for pulmonary embolism. To date, no cases of pulmonary cryptococcosis co-occurring with pulmonary embolism in the postpartum period have been documented. This case report describes a 39-year-old female who was diagnosed with HIV-negative pulmonary cryptococcosis with pulmonary embolism 42 days postpartum and experienced improvement in her condition after active antifungal and anticoagulant therapy. Given the physiologic immunosuppression and hypercoagulable state associated with pregnancy, the possibility of pulmonary cryptococcosis combined with pulmonary embolism should be considered in postpartum women with chest pain and newly discovered lung shadow.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12890-025-03902-8.

Keywords: Pulmonary cryptococcosis, Pulmonary embolism, Postpartum, Case report

Background

Cryptococcosis is a global fungal disease caused by cryptococcal infection, usually involving the central nervous system and lungs, mainly through respiratory inhalation of cryptococcal spores [1]. Pulmonary cryptococcosis usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients, with non-specific clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Pregnancy-related immune changes may lead to the occurrence of pulmonary cryptococcosis.Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major factor in maternal death [2]. The maternal mortality rate associated with pulmonary embolism in the United States increased from 0.93 in 2003 to 1.96 in 2020 [3], and the risk of pulmonary embolism is significantly increased from the beginning of pregnancy to 60 days after hospitalization during delivery [4]. PE is characterized by dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, and hemoptysis, but may also manifest with non-specific symptoms [5]. The peripartum period constitutes a major risk factor for pulmonary vascular embolism due to hormonally mediated hypercoagulability, cardiovascular adaptations, anatomic changes, and behavioral modifications [6].

Peripartum women are are at increased risk for pulmonary cryptococcosis and pulmonary thromboembolism secondary to physiologic immunosuppression and a hypercoagulable state, but there is no related case report.This case report describes a 39-year-old woman diagnosed with HIV-seronegative pulmonary cryptococcosis coexisting with PE embolism 42 days postpartum. The patient achieved clinical improvement following combined antifungal and anticoagulant therapy. This case provides critical insights for the diagnosis and management of postpartum women presenting with chest pain and newly identified pulmonary nodules or consolidations.

Case introduction

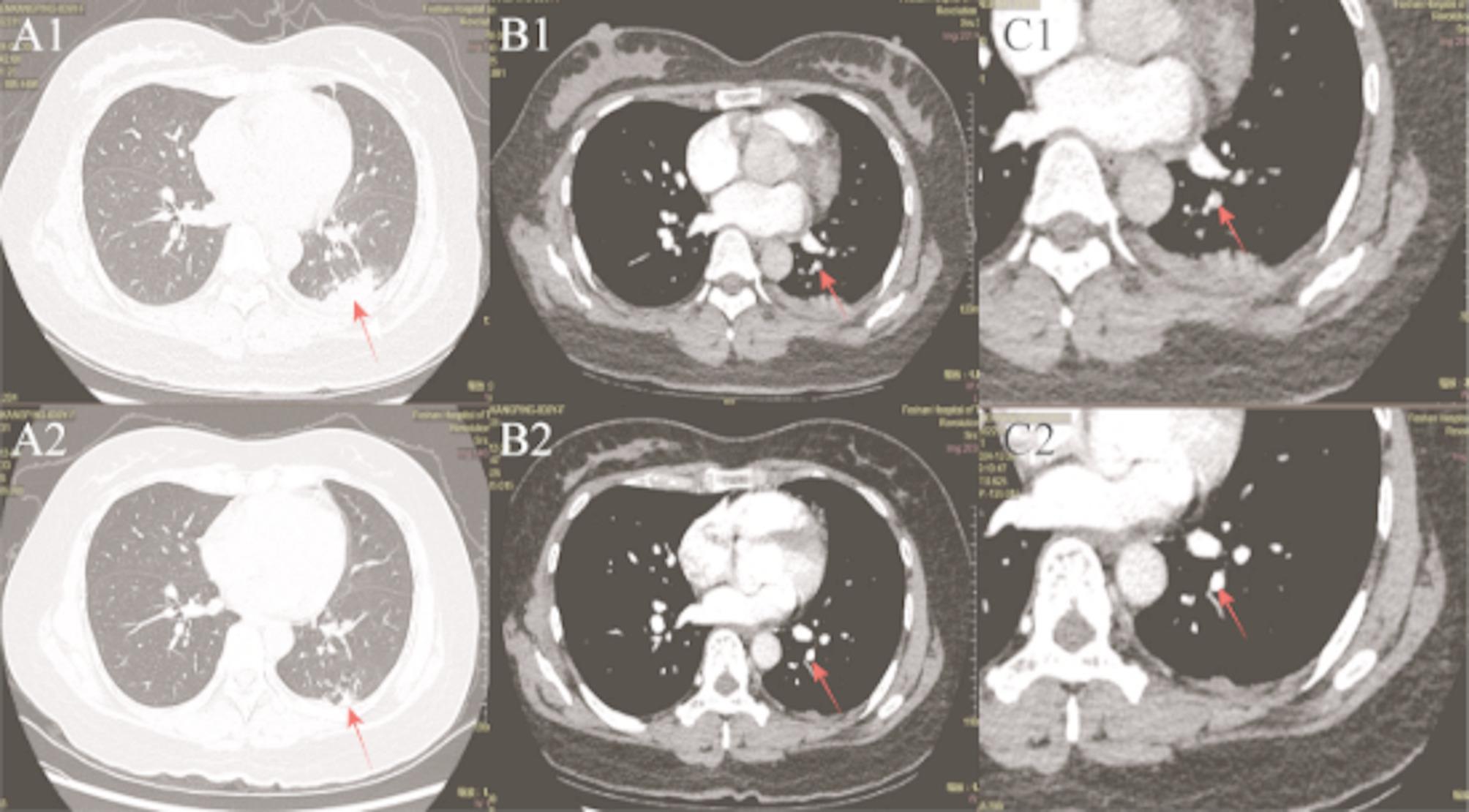

A 39-year-old woman presented to our respiratory department with shadow in her lower left lung for 3 weeks. Three weeks ago, she had been diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia presenting with left lower chest and back pain in a foreign hospital, and the symptoms improved after anti-infection with levofloxacin. However, reexamination of non-contrast chest computed tomography (CT) indicated that the left lower lung shadow was not absorbed. The patient had no symptoms such as chest pain, cough, and fever on admission. The patient delivered a baby vaginally one month ago, and had chronic hepatitis Bmanaged with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg daily. She denied any history of contact with animals, dust, or long-distance travel. Laboratory test: Cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) positive (titer 1:80); D-dimer: 0.47 µg/mL (reference: 0–0.5 µg/mL); Protein S: 59.9% (reference: 60–130%); Lupus anticoagulant screen: 1:30.2 s (reference: 31–44 s); Antithrombin III, protein C and other inherited risk factors for venous thrombosis, as well as antiphospholipid syndrome antibodies, homocysteine and other acquired risk factors for venous thrombosis, sputum culture and so on all normal.enhanced CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) shows pulmonary artery embolism in the left lower lobe, left pneumonia and a small amount of pleural effusion (Fig. 1:A1-C1).Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild mitral regurgitation and no evidence of vegetations. Color Doppler ultrasonography of the lower extremity veins and brain MRI with/without contrast were unremarkable. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) for microbiological studies was recommended but declined by the patient. At this point, the diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis combined with pulmonary embolism was clear, and the patient was discharged after 5 days of treatment with enoxaparin injection combined with fluconazole sodium chloride injection without special discomfort. Post-discharge therapy included oral rivaroxaban and fluconazole, with cessation of breastfeeding advised.

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT of pulmonary arteries(CTPA) at baseline versus follow-up after therapy. A1/A2: Lung window at baseline versus follow-up after therapy, demonstrating parenchymal lesions (arrows). B1/B2: CTPA window at baseline versus follow-up, showing vascular lesions (arrows). C1/C2: Magnified views of B1/B2, respectively, for detailed lesion assessment (arrows). Red arrows indicate lesions

Follow-up of CTPA at 4 months post-treatment demonstrated complete resolution of the pulmonary embolism and partial resolution of the left lower lobe infiltrates compared with initial imaging (Fig. 1:A2-C2).CrAg positive (titer 1:80).At present, The patient continued maintenance therapy with oral fluconazole and reported no adverse events during surveillance.

Discussion

The clinical spectrum of pulmonary cryptococcosis ranges from asymptomatic infection to pulmonary nodules and even respiratory failure [7]. The chest imaging manifestations include patchy opacities, ground-glass opacities (GGO), and consolidations, typically demonstrating peribronchovascular distribution with halo signs, cavitations, or pleural effusions [8]. Cryptococcosis is most commonly seen in HIV-infected and solid organ transplant recipients, but other immunocompromised hosts and immunocompetent populations can develop the disease [1].

During pregnancy, physiological immune adaptation involves a Th1-to-Th2 shift mediated by hormonal changes, Th2 cells stimulate B lymphocytes to increase antibody production, inhibit cytotoxic T lymphocyte response, ultimately compromising cell-mediated immunity The decline in the number and function of CD4, CD8, and natural killer cells may affect the antifungal response and delay the clearance of pathogenic microorganisms [9].Postpartum cryptococcosis in non-HIV patients typically manifests between 1 week and 6 months after delivery (median: 2 months) [10].In this case, patient’s initial pleuritic chest pain resolved after empirical antimicrobial therapy, but the left lower lung flaky shadow still existed, and the pain was considered to be caused by pleurisy. Asymptomatic postpartum pulmonary cryptococcosis has also been reported in the past [10], so it is considered that the pulmonary cryptococcosis is asymptomatic infection.

Although definitive diagnosis of cryptococcosis requires positive cultures from sterile sites, direct microscopic identification of encapsulated yeasts, or histopathological confirmation, these methods necessitate invasive procedures and may delay clinical management. CrAg is a low-cost, immediate detection test whose positive results have been identified as one of the diagnostic criteria by the European Guidelines for the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis [11].The expert consensus on cryptococcal pneumonia in China points out that positive serum CrAg detection, combined with medical history and imaging manifestations can clinically diagnose cryptococcal pneumonia [12]. The overall sensitivity and specificity of CrAg for the diagnosis of cryptococcal infection were 97.6% and 98.1% [13], and false positives were only present when the titer was 1:2 to 1:5 [14, 15]. Therefore, despite the absence of histopathological or culture confirmation, the diagnosis could be made based on the patient’s medical history, chest CT findings of lung shadow, high cryptococcus capsular antigen titer, and imaging reexamination after antifungal treatment.Our patient’s follow-up cryptococcal antigen test remains positive, but the titer has not increased. Combined with improved CT findings and absence of clinical symptoms, we consider this likely due to delayed antigen clearance.

Pregnant and postpartum women have a 6-fold higher risk of VTE compared to non-pregnant women, and the incidence peaks in the first 6 weeks after delivery [16]. This elevated thromboembolic risk is mechanistically explained by the classic Virchow triad. Changes in sex hormone levels during pregnancy lead to an increase in coagulation factors (factors I, II, VII, VIII, IX, and X) and a decrease in antithrombotic factors (such as protein C and protein S), leaving pregnant women in a hypercoagulable state [17]. Hemodynamic changes are related to iliac vein compression, while endothelial injury is due to injury during childbirth [18].

This case demonstrated moderately reduced protein S levels, while other thrombophilia tests were negative. This reduction in protein S was attributed to a physiological adaptation aimed at mitigating potential hemorrhagic risk during delivery [19]. Additionally, infection is the most common cause of hospitalization for VTE [20]. Studies investigating the immune status of patients with PE have revealed a reduction in Th1 activity and an enhancement in Th2 activity [21]. Considering these findings alongside the established link between infection and VTE hospitalization, it is plausible that cryptococcal infection may contribute to the development of PE.D-dimer is elevated during acute thrombosis, due to physiological changes in female D-dimer during pregnancy and false negative in some PE patients.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines advise against the use of D-dimer testing for VTE evaluation during pregnancy and the puerperium [22]. Consequently, although the D-dimer in this patient was within the normal range, the presence of significant risk factors necessitates that pulmonary embolism remain a critical diagnostic consideration. CTPA represents the diagnostic gold standard for pulmonary embolism. In this patient, CTPA revealed evidence of pulmonary embolism in the posterior basal segment of the left lower lobe, alongside patchy opacities in the same lobeCombined with a positive CrAgtest result, these findings confirmed a final diagnosis of concurrent cryptococcal infection and pulmonary embolism.

Pulmonary infarction is a condition in which pulmonary blood vessel obstruction leads to ischemia and alveolar hemorrhage. If the latter cannot be absorbed, it will eventually lead to lung tissue necrosis [23], and fibrous scars will be formed in the infarct area, lasting for weeks or even months [24]. The clinical manifestations of patients with pulmonary infarction are not specific, but pleurisy chest pain often occurs [24], which may be related to the pleural inflammation, irritation and necrosis caused by alveolar hemorrhage. At present, the diagnosis of pulmonary infarction is still mainly based on imaging, which is usually wedge-shaped in the subpleura, and its imaging manifestations include consolidation, pulmonary edema, pleural effusion and ground glass changes [25]. In our case, the shadow in the patient’s lung was considered to be caused by cryptococcal infection and pulmonary embolism leading to infar.It was speculated that the patient’s chest pain may be related to the secondary infection caused by ischemia, hemorrhage, and swelling caused by the infarction lesion, and Gocho et al. [26]. also reported the elimination of chest pain in patients with secondary infection of pulmonary infarction by anti-infection treatment, thus we inferred that the symptoms of chest pain in this case were improved before admission by levofloxacin through the treatment of secondary infection of pulmonary infarction.

The treatment of pulmonary cryptococcosis is determined by disease severity. This case was treated with fluconazole orally after discharge with mild clinical symptoms. In the treatment of pulmonary thromboembolism, anticoagulation, thrombolysis and interventional therapy can be selected according to the risk stratification. Common oral anticoagulation drugs include warfarin and rivaroxaban. Warfarin is predominantly metabolized (> 80%) by Cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9), As fluconazole acts as a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9, their concomitant use elevates therisk of bleeding [27]. However, rivaroxaban exhibits rapid absorption following oral administration, and has a reduced potential for drug-drug interactions, eliminating the need for International Normalized Ratio (INR) monitoring. Therefore, the patient was prescribed long-term oral rivaroxaban combined with fluconazole treatment following discharge. Given that both fluconazole and rivaroxaban are excreted in breast milk, this patient was advised to discontinue breastfeeding.

There are still the following deficiencies in this case: First, the postpartum transition of the maternal immune system from a Th2- to a Th1-dominant state may trigger immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome inflammatory syndrome [28]. Due to the absence of available pre-pregnancy chest imaging, so it cannot be ruled out that the patient had a pulmonary cryptococcal infection before pregnancy and may have worsened during pregnancy. Second, while the genus Cryptococcus encompasses 37 recognized species, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii represent the primary pathogens responsible for human cryptococcosis [29]. As the patient declined invasive procedures, direct pathogen identification and histopathological examination of the lesion tissue were not performed in this case, Consequently, the specific Cryptococcus species causing the infection could not be definitively identified.

Conclusion

We report a case of postpartum pulmonary cryptococcosis complicated by pulmonary embolism. This suggests that in women presenting with postpartum chest pain and newly identified pulmonary shadows, concurrent pulmonary embolism and cryptococcal infection should be considered, particularly given the hypercoagulable state and immune alterations during pregnancy/postpartum. The combined regimen of fluconazole and rivaroxaban appears safe and effective in this clinical scenario. We acknowledge as a limitation that microbiological confirmation of cryptococcosis was not obtained due to patient refusal of invasive procedures.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to Ms. Chen for granting explicit authorization for manuscript preparation, and to Ms. Xingchen Zhou for providing professional guidance on linguistic adaptation of this document.

Abbreviations

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTPA

Enhanced CT pulmonary angiography

- CrAg

Cryptococcal antigen

Authors’ contributions

Z. Q., P. Z. designed the study. Y. C., W. L. collected data. Z. Q., P. Z.,Y. C. analyzed data and wrote the case report. P. Z., Y. C., W. L., Z. H., H. M., H. G. contributed to the discussion of results and to the review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was obtained from institutional, corporate, or philanthropic sources to support this research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Z. Q. will make the data available to readers.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Foshan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine approved the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chang CC, Harrison TS, Bicanic TA, Chayakulkeeree M, Sorrell TC, Warris A, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: an initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in Cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(8):e495–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalaitzopoulos DR, Panagopoulos A, Samant S, Ghalib N, Kadillari J, Daniilidis A, et al. Management of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Thromb Res. 2022;211:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmakis IT, Barco S, Hobohm L, Braekkan SK, Connors JM, Giannakoulas G, et al. Maternal mortality related to pulmonary embolism in the united states, 2003–2020. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(1):100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kola O, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, Wright JD, Friedman AM. Trends in Antepartum, Delivery, and Postpartum Venous Thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2025;145(3):e98–e106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wrenn JO, Kabrhel C. Emergency department diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Br J Haematol. 2024;205(5):1714–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuelson Bannow B, Federspiel JJ, Abel DE, Mauney L, Rosovsky RP, Bates SM. Multidisciplinary care of the pregnant patient with or at risk for venous thromboembolism: a recommended toolkit from the foundation for women and girls with blood disorders thrombosis subcommittee. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(6):1432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jani A, Reigler AN, Leal SM Jr, McCarty TP. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2025 ;39(1):199–219. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dai C, Bai D, Lin C, Li KY, Zhu W, Lin J, et al. The relationship between lung CT features and serum Cryptococcal antigen titers in localized pulmonary cryptococcosis patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama T, Kadowaki M, Yoshida M, Suzuki K, Komori M, Iwanaga T. Disseminated cryptococcosis with marked eosinophilia in a postpartum woman. Intern Med. 2018;57(1):135–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European organization for research and treatment of cancer/invasive fungal infections cooperative group and the National Institute of allergy and infectious diseases mycoses study group (EORTC/MSG) consensus group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1813–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association RSoZM. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary cryptococcosis. Chin J Clin Infect Dis. 2017;10(5):321–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang HR, Fan LC, Rajbanshi B, Xu JF. Evaluation of a new Cryptococcal antigen lateral flow immunoassay in serum, cerebrospinal fluid and urine for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Kang M, Wu SY, Wu LJ, He L, Xiao YL et al. Evaluation of a Cryptococcus capsular polysaccharide detection fungixpert LFA (lateral flow assay) for the rapid diagnosis of cryptococcosis. Med Mycol. 2022;60(4):myac020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Dubbels M, Granger D, Theel ES. Low Cryptococcus antigen titers as determined by lateral flow assay should be interpreted cautiously in patients without prior diagnosis of Cryptococcal infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(8):2472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moroi ȘI, Weiss E, Stanciu S, Bădilă E, Ilieșiu AM, Balahura AM. Pregnancy-Related Thromboembolism-Current challenges at the emergency department. J Pers Med. 2024;14(9):926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Makowska A, Treumann T, Venturini S, Christ M. Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy: A review for clinical practitioners. J Clin Med. 2024;13(10):2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Blondon M, Skeith L. Preventing postpartum venous thromboembolism in 2022: A narrative review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:886416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgescu T. The role of maternal hormones in regulating autonomic functions during pregnancy. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35(12):e13348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers MA, Levine DA, Blumberg N, Flanders SA, Chopra V, Langa KM. Triggers of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2012;125(17):2092–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan Q, Lv W, Wang L, Gong Z, Wang Q, Song H, et al. mRNA expression of interleukins and Th1/Th2 imbalance in patients with pulmonary embolism. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7(1):332–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: Thromboembolism in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 ;132(1):e1-e17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kaptein FHJ, Kroft LJM, van Dam LF, Stöger JL, Ninaber MK, Huisman MV, et al. Impact of pulmonary infarction in pulmonary embolism on presentation and outcomes. Thromb Res. 2023;226:51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagno G, Padoan L, D'Errico S, Baratella E, Radaelli D, Fluca AL, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with pulmonary infarction: Update and practical review of literature data. J Clin Med. 2022;11(16):4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Lio KU, O’Corragain O, Bashir R, Brosnahan S, Cohen G, Lakhter V, et al. Clinical outcomes and factors associated with pulmonary infarction following acute pulmonary embolism: a retrospective observational study at a US academic centre. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12):e067579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gocho K, Kitazawa S, Matsushita S, Hamanaka N. Low-dose oestrogen-progestin associated pulmonary infarction mimicking pneumonia and pleurisy. Respirol Case Rep. 2021;9(9):e0833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng K, Shen C, Wang X, Wang X, Shao W, Wang W, et al. A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling approach for drug-drug-gene interaction evaluation of S-warfarin with fluconazole. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2024;13(5):853–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh N, Perfect JR. Immune reconstitution syndrome and exacerbation of infections after pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C, Huang Y, Zhou Y, Zang X, Deng H, Liu Y, et al. Cryptococcus escapes host immunity: what do we know? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1041036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Z. Q. will make the data available to readers.