Abstract

Objective:

Neurocritically ill patients are at high risk for developing delirium, which can worsen the long-term outcomes of this vulnerable population. However, existing delirium assessment tools do not account for neurological deficits that often interfere with conventional testing and are therefore unreliable in neurocritically ill patients. We aimed to determine the accuracy and predictive validity of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE), a novel delirium screening tool developed specifically for neurocritically ill patients.

Design:

Prospective validation study.

Setting:

Neurocritical care unit at an academic medical center.

Patients:

139 neurocritically ill stroke patients (mean age 63.9 [SD 15.9], median NIHSS score 11 [IQR 2–17]).

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Expert raters performed daily DSM-5-based delirium assessments, while paired FMSE assessments were performed by trained clinicians. We analyzed 717 total non-comatose days of paired assessments, of which 52% (n=373) were rated by experts as days with delirium; 53% of subjects were delirious during one or more days. Compared with expert ratings, the overall accuracy of the FMSE was high (AUC 0.85, 95% CI 0.82–0.87). FMSE scores ≥1 had 86% sensitivity and 74% specificity on a per-assessment basis, while scores ≥2 had 70% sensitivity and 88% specificity. Accuracy remained high in patients with aphasia (FMSE ≥1: 82% sensitivity, 64% specificity; FMSE ≥2: 64% sensitivity, 84% specificity) and those with decreased arousal (FMSE ≥1: 87% sensitivity, 77% specificity; FMSE ≥2: 71% sensitivity, 90% specificity). Positive FMSE assessments also had excellent accuracy when predicting functional outcomes at discharge (AUC 0.86 [95% CI 0.79–0.93]) and 3-months (AUC 0.85 [95% CI 0.78–0.92]).

Conclusions:

In this validation study, we found that the FMSE was an accurate delirium screening tool in neurocritically ill stroke patients. FMSE scores ≥1 indicate “possible” delirium and should be used when prioritizing sensitivity, whereas scores ≥2 indicate “probable” delirium and should be used when prioritizing specificity.

Keywords: Delirium, neurocritical care, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage

Introduction

Delirium is an acute cognitive disorder associated with poor outcomes across diverse patient populations and settings(1–4). Despite having some of the highest incidence rates of delirium, neurocritically ill patients pose a challenge to existing delirium assessment methods(5, 6). While some tools address ICU patients’ inability to verbally communicate due to intubation, existing tools do not address other barriers to delirium assessment in neurocritically ill patients, with complex symptoms such as aphasia, apraxia, or other focal neurological deficits that can confound their effectiveness(6–9).

Though neurocritical care perspectives on delirium are not yet fully harmonized, mounting evidence indicates that the neuropsychiatric syndrome widely recognized as delirium in other patient populations occurs frequently in neurocritically ill patients and is separate from the direct effects of a focal injury. First, brain lesions cause deficits that tend to persist or evolve over prolonged time-periods, whereas delirium symptoms typically fluctuate in the acute setting and eventually resolve in most patients, even those with neurological injury(10). Second, focal brain lesions are more likely to cause relatively well-defined neurological deficits in the acute setting, whereas acute delirium symptoms are more likely to represent the manifestation of diffuse neurological dysfunction(11). Third, among patients with identical brain lesions, some may develop delirium whereas others will not(12).

Given the clinical implications of delirium in neurocritically ill patients(10, 13), there is an urgent need for more reliable assessment methods to identify delirium superimposed on focal neurological deficits. Fortunately, neurocritical care settings are designed to detect subtle exam changes and monitor for secondary complications via frequent neurological assessments. Leveraging these unique clinical opportunities, we created the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE), a novel delirium screening tool designed specifically with neurocritical care patients and providers in mind. The FMSE emphasizes fluctuations from a new cognitive baseline, especially with respect to observable delirium features that do not rely on verbal testing. It also uses an innovative systematic approach to identify fluctuating inattention in the context of focal neurological deficits. In our earlier pilot study, the FMSE had high accuracy when used by bedside clinical nurses to detect delirium among patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)(14). In this follow-up validation study, we sought to test the validity and accuracy of the FMSE in a larger, more representative cohort of neurocritically ill stroke patients.

Methods

Study Population

We screened consecutive adults admitted to an academic Comprehensive Stroke Center’s Neurocritical Care Unit within 72-hours of an acute ischemic stroke, ICH, or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Because we sought to determine predictive validity, we excluded patients with significant pre-morbid functional disability (defined as modified Rankin Scale [mRS] ≥2) and those with early withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WLST). We also excluded non-English-speaking patients. This study was approved by Lifespan IRB 3 (ID #1585181, July 2020), and we obtained informed consent from all participants and/or designated surrogates in accordance with institutional ethical standards and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

FMSE Ratings

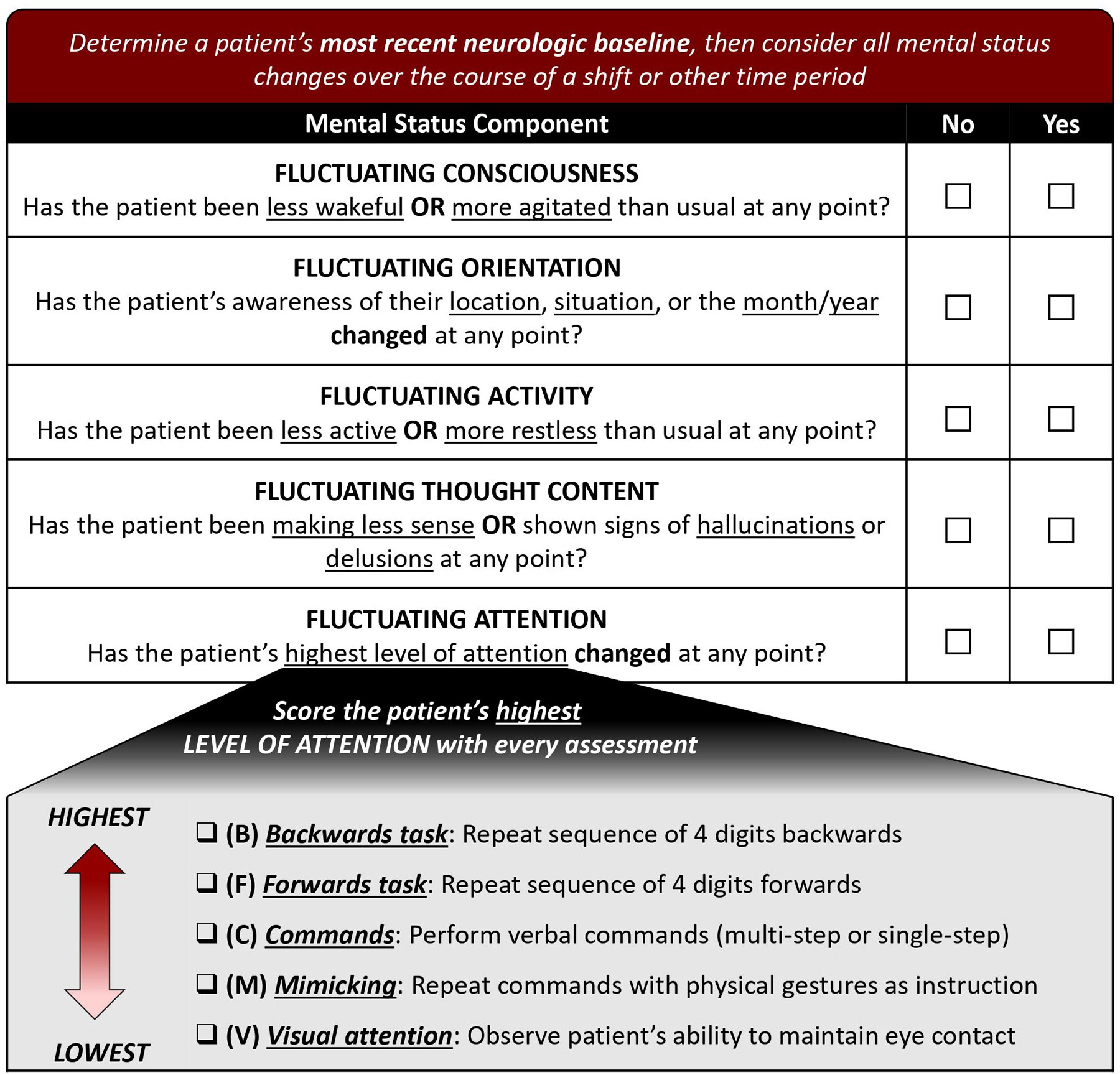

The FMSE is a 5-point screening tool that assesses for changes over time in five cognitive domains (scored “yes” or “no”): level of consciousness, orientation, activity, thought content, and attention, with the latter assessed systematically based on a patient’s baseline level of function (Figure 1). These domains were chosen because they are often affected during delirium(15), with our preliminary studies supporting their high prevalence in neurologically-injured patients (albeit with varying levels of assessability using conventional methods)(6). Our finding that a new change or fluctuation in mental status had the highest prevalence among delirium features ultimately formed the basis of the FMSE. Overall FMSE scores can range from 0–5 points, with higher scores reflecting more impairment.

Figure 1.

Scoring sheet for the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE).

Raters must first determine a patient’s new established baseline, defined as a consistent or expected level of cognitive function in the context of their acute neurological illness. This baseline should be established using medical records, family, caregivers, and other clinicians, and should consider whether a patient would be expected to be able to follow commands and answer orientation questions appropriately based on the specifics of their neurological injury. Relevant information on cognitive status can be obtained from documented neurological exams, which are regularly performed by neurologists, neurosurgeons, neuroscience nurses, and physical, occupational, and speech therapists, as well as clinical scores such as the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS), Glasgow Coma Scale, and Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). Several reassessments may be needed to differentiate relatively fixed stroke-related deficits from fluctuating deficits more characteristic of delirium; if a patient’s symptoms have continuously fluctuated between reassessments, then a new baseline has not yet been established. Thereafter, raters consider all changes to mental status (e.g., assessed during hourly neurochecks) over the course of a designated time-period and compared with previous assessments, irrespective of potential causes of these changes. Clinicians are encouraged to consider the effects of sedatives on a patient’s mental status, especially if recent medication doses or adjustments arose from or led to a change in mental status. Raters score “yes” for any components for which a change occurred during the applicable time-period (even if it subsequently returned to baseline or improved) and “no” for components that remained unchanged since their new baseline was established. Raters score “no” for all domains in patients who are consistently comatose.

FMSE Training

The FMSE was performed by four advanced practice providers (APPs) who received in-depth training from the principal investigator (MR). APPs were chosen given their role as frontline neurocritical care providers and to extend generalizability of the FMSE, which was performed by bedside nurses in the pilot study.

Training included a dedicated educational session using teaching slides as well as a case-based quiz administered before and after the educational session (Supplementary Materials). Feedback from APP raters suggested that scoring generally required approximately 1-minute to complete.

Because FMSE raters participated on a rotating basis when performing study assessments (i.e., only one rater performed assessments on a given day), we calculated inter-rater reliability using data obtained from the training quizzes, which included a total of 20 questions spanning 5 representative sample cases.

Delirium Assessments

Study participants were assessed for delirium once daily from enrollment to ICU discharge, except for weekends and holidays. Daily assessments were augmented with focused chart review of clinical events from the previous 24 hours and interviews with bedside nurses and family members to identify other events that may not have been documented. Delirium was diagnosed by expert raters—an attending neurointensivist (MR) or neuropsychologist (SM)—according to reference-standard DSM-5 criteria (16), with specific consideration given to factors known to distinguish delirium symptoms from expected stroke-related cognitive deficits(6, 13, 17). Other delirium screening tools were not used given previous concerns about their reliability in neurologically-injured patients. All cases were discussed and adjudicated by the two expert raters until consensus was achieved.

Both expert assessments and those performed by FMSE raters occurred independently each afternoon at approximately 3 PM and integrated clinical events spanning the previous 24 hours (3 PM–3 PM). Expert raters were blinded to FMSE scores (and vice-versa), with scoring sheets collected by a research assistant in a sealed envelope.

Clinical Data and Outcomes

We collected data related to delirium assessments and clinical stroke care in a REDCap(18) database. A certified assessor evaluated each participant on the day of enrollment using the NIHSS, and two board-certified neurointensivists adjudicated stroke-related clinical variables.

A certified assessor determined mRS(19) scores, a measurement of post-stroke functional disability, at discharge and at 3-months via standardized telephone calls. We considered mRS scores between 0 (no symptoms) and 2 (slight disability) to be a favorable outcome.

Sample Size

In the pilot study, the FMSE’s sensitivity was 86% with a cut-point of ≥1 and 68% with a cut-point of ≥2, while specificity was 73% with a cut-point of ≥1 and 82% with a cut-point of ≥2. Because the FMSE’s primary purpose is screening for delirium, we prioritized high sensitivity. Thus, we considered 85% an appropriate and feasible lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) of test sensitivity. Assuming a delirium incidence of 50% and no dropout, we determined that a study sample of 138 patients would ensure that the lower range of the CI for sensitivity in the study cohort was 85%.

Statistical Analysis

We reported means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed data and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normal data. We calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for each FMSE cut-point, having previously established scores ≥1 and ≥2 corresponding to “possible” and “probable” delirium, respectively. All analyses excluded comatose assessments, which we defined as no purposeful response to voice or physical stimulation (typically corresponding to RASS −5). We used area under the curve (AUC) analysis to quantify the FMSE’s overall accuracy.

We analyzed FMSE cut-points on both a per-assessment and per-participant basis and used the latter to determine the FMSE’s ability to detect delirium at any point during hospitalization. This latter approach can be used to identify “ever delirious” patients in clinical care and research studies. We performed pre-planned subgroup analyses in participants with (1) aphasia, (2) decreased arousal (RASS ≤−2), and (3) mechanical ventilation (including additional analyses in patients receiving anesthetic infusions). We also assessed construct validity using multivariable logistic regression to determine the association between positive FMSE scores and known predictors of delirium in stroke patients, including age, stroke severity, and stroke subtype(20).

Finally, we assessed the FMSE’s predictive validity by calculating the accuracy of positive scores in predicting favorable vs. unfavorable outcomes at discharge and 3-months via AUC analysis adjusted for stroke subtype. We fit logistic regression models that included stroke subtype as a covariate, number of FMSE-positive days (using a scoring threshold of ≥1) as the primary predictor variable, and discharge or 3-month functional outcome as the dependent variable. Then, we determined the AUC of the model-predicted probability of unfavorable outcome, considering a predicted probability ≥0.5 as a positive outcome. We performed all statistical analyses using Stata/SE 16 (College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

We enrolled 140 patients but excluded one due to persistent coma. Of the remaining 139 participants, 27% (n=38) had ischemic stroke, 44% (n=61) had ICH, and 29% (n=40) had SAH (Table 1). Aphasia was present in 38% (n=53) and moderately-to-severely decreased arousal was present in 34% (n=47), while 31% (n=43) were mechanically ventilated during their hospitalization.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the study cohort (n=139).

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 63.9 (15.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 71 (51%) |

| White, n (%) | 121 (87%) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Known history of dementia | 3 (2%) |

| Prior stroke | 12 (9%) |

| Hypertension | 88 (63%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 26 (19%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 8 (6%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (19%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (7%) |

| Stroke characteristics | |

| NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 11 (2–17) |

| Initial GCS score <13, n (%) | 40 (29%) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, n (%) | 61 (44%) |

| Stroke subtype | |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 38 (27%) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage, n (%) | 61 (44%) |

| ICH score, median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage, n (%) | 40 (29%) |

| Hunt-Hess score, median (IQR) | (1–3) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; IQR, interquartile range; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage

According to expert ratings, delirium occurred in 53% of patients (n=74), including 45% of those with ischemic stroke, 62% with ICH, and 48% with SAH. Among patients with delirium, mean delirium duration was 5.5 (SD 5.6) days.

Interrater Reliability

In the pre-test prior to receiving training, percent agreement of positive FMSE assessments between the four FMSE raters was 81%, with moderate interrater reliability (κ=0.45, 95% CI 0.17–0.73). After FMSE training, percent agreement in the post-test increased to 94%, with excellent interrater reliability (κ=0.86, 95% CI 0.67–1.00).

FMSE Ratings & Accuracy

There were 717 total non-comatose days of paired assessments, of which 373 (52%) were rated by experts as days with delirium. Across all study days, the median (IQR) FMSE score was 1 (0–3), with 57% of assessments (411/717) having a score ≥1 (including 126 corresponding to clinically significant neurologic or other complications; Supplementary Table). Among individual FMSE components, fluctuating consciousness was most frequently scored, followed by fluctuating attention (Figure 2). In multivariable logistic regression, age (OR 1.03 per year [95% CI 1.02–1.04]), NIHSS (OR 1.04 per point [95% CI 1.02–1.06]), and stroke subtype (ICH: OR 4.3 [95% CI 2.6–7.0]; SAH: OR 3.5 [95% CI 2.1–5.8]) were all strongly associated with positive FMSE assessments.

Figure 2.

Frequency of individual components of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE) corresponding to patients with and without delirium as determined by expert raters.

Compared with expert ratings, the FMSE’s overall accuracy was high (AUC 0.85, 95% CI 0.82–0.87; Figure 3A). FMSE scores ≥1 had 86% sensitivity (95% CI 82%−89%) and 74% specificity (95% CI 69%−78%) on a per-assessment basis, while scores ≥2 had 70% sensitivity (95% CI 65%−74%) and 88% specificity (95% CI 84%−91%). Positive predictive value ranged from 78% (95% CI 74%−82%) using a cut-score ≥1 to 86% (95% CI 82%−90%) at a cut-score ≥2; negative predictive value was greatest (83% [95% CI 78%−87%]) at a cut-score of ≥1. On a per- participant basis, FMSE scores ≥1 offered high sensitivity while scores ≥2 had higher specificity (Table 2).

Figure 3.

(A) Accuracy of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE) compared to expert delirium assessments. (B) Accuracy of the FMSE and expert delirium assessments in predicting unfavorable 3-month outcomes, defined as modified Rankin Scale 3–6. Models included the number of positive FMSE or expert assessments per patient and were adjusted for stroke subtype.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE) by cut-point, with 95% confidence intervals.

| Total FMSE Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 | ≥2 | ≥3 | |

| Per assessment (n=717) | |||

| Sensitivity | 86% (82–89%) | 70% (65–74%) | 45% (40–51%) |

| Specificity | 74% (69–78%) | 88% (84–91%) | 95% (92–97%) |

| PPV | 78% (74–82%) | 86% (82–90%) | 91% (86–95%) |

| NPV | 83% (78–87%) | 73% (68–77%) | 62% (57–66%) |

| Per patient, ever delirious (n=139) | |||

| Sensitivity | 95% (87–99%) | 89% (80–95%) | 76% (64–85%) |

| Specificity | 63% (50–75%) | 83% (72–91%) | 92% (83–98%) |

| PPV | 75% (64–83%) | 86% (76–93%) | 92% (82–97%) |

| NPV | 91% (79–98%) | 87% (76–94%) | 77% (66–86%) |

In participants with aphasia (n=295 assessments), FMSE scores ≥1 had 82% sensitivity (95% CI 76–88%) and 64% specificity (95% CI 55–73%) on a per-assessment basis, while scores ≥2 had 64% sensitivity (95% CI 57–71%) and 84% specificity (95% CI 76–91%). Meanwhile, in participants with decreased arousal (n=324 assessments), FMSE scores ≥1 had 87% sensitivity (95% CI 76–95%) and 77% specificity (95% CI 72–82%) on a per-assessment basis, while scores ≥2 had 71% sensitivity (95% CI 57–82%) and 90% specificity (95% CI 86–93%). Finally, in patients who were mechanically ventilated (n=114 assessments), FMSE scores ≥1 had 83% sensitivity (95% CI 74–90%) and 72% specificity (95% CI 47–90%) on a per-assessment basis (with 82% sensitivity [95% CI 70–90%] and 80% specificity [95% CI 56–94%] in patients receiving anesthetics), while scores ≥2 had 60% sensitivity (95% CI 49–69%) and 83% specificity (95% CI 59–96%) (with 60% sensitivity [47–72%] and 90% specificity [68–99%] in patients receiving anesthetics).

Predictive Validity

Discharge outcomes were available for all participants, while 3-month outcomes were available for 96% (134/139). Median (IQR) mRS at hospital discharge was 4 (3–5), with 53% (34/64) of never delirious patients and 14% (10/74) of ever delirious patients classified as having a favorable outcome at the time of hospital discharge. At 3 months, median (IQR) mRS was 3 (1–5), with 62% (38/61) of never delirious patients and 22% (16/72) of ever delirious patients classified as having a favorable outcome.

Total number of positive FMSE scores ≥1 had excellent accuracy in predicting favorable vs. unfavorable post-acute outcomes (discharge: AUC 0.86 [95% CI 0.79–0.93]; 3-months: AUC 0.85 [95% CI 0.78–0.92]). This was comparable to the accuracy of the total number of positive expert assessments for each patient (discharge: AUC 0.87 [95% CI 0.80–0.93]; 3-months: AUC 0.83 [95% CI 0.75–0.90]) (Figure 3B).

Discussion

Neurocritical care settings are ideally equipped to detect neurological changes since they depend on frequent neurological examinations performed by dedicated neuroscience nurses and providers. By extension, the diagnosis and management of delirium should be a core component of neurocritical care. In this study, we found that the FMSE is a valid delirium screening tool in neurocritically ill stroke patients, with good sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy. Our findings therefore support use of the FMSE in critically ill patients with neurological deficits, and we recommend performing an FMSE assessment at least once per shift (or 2–3 times per day) to adequately capture clinically relevant mental status changes in a timely manner.

The FMSE is the first delirium screening tool designed specifically for the challenging neurocritical care population. Its advantages over existing tools include its focus on fluctuations in individual domains over time and its graded approach to assessing attention in the context of a patient’s neurological baseline, both of which facilitate delirium assessment in patients with complex neurological deficits such as aphasia. Despite these potentially confounding impairments, the FMSE had high overall accuracy compared with expert assessments, with sufficiently high sensitivity at scores ≥1 and high specificity with scores ≥2 to justify labels of “possible” and “probable” delirium, respectively. (Note, however, that in some cases the FMSE may initially identify the first day of delirium but then miss succeeding days in which a patient’s delirium has not shown substantial evolution or clinically apparent intra-day fluctuation.) Although a rating of “possible” delirium warrants a more extensive confirmatory assessment, FMSE scores ≥1 also demonstrated excellent predictive validity, with comparable accuracy in predicting post-acute outcomes to expert assessments. Different FMSE applications may warrant use of one cutoff over the other. When screening for delirium, for example, sensitivity should be prioritized, and FMSE scores ≥1 should be used. Alternatively, specificity should be prioritized when determining eligibility for an interventional trial, for which FMSE scores ≥2 may be preferred.

Timely delirium recognition has an important and clinically relevant role in neurocritical care, especially considering the emphasis on early detection and prevention of neurological deterioration. Importantly, many causes of neurological deterioration in patients with acute brain injury can manifest as delirium(21); because these causes are often treatable, an underlying precipitant of delirium should be investigated as in any other population. Indeed, we have found that the constellation of delirium symptoms may correspond to a wide range of etiologies in neurocritically ill patients, including new or worsening neurological injury, secondary neurological sequelae, non-neurological hospital complications, medication effects, or other causes that may not be immediately apparent, and their presenting phenomenology may otherwise be indistinguishable(6, 21). Even when an immediately treatable cause is not found, increased awareness of delirium can help identify other potential contributing factors that can be modified in certain scenarios, such as overly frequent awakening for neurological examinations(22). Better recognition of delirium as a transient disorder may also impact survival and long-term recovery in neurocritically ill patients, who have higher rates of WLST and lower rates of post-acute rehabilitation compared to patients without delirium(10, 13).

Therefore, a pragmatic, valid delirium assessment tool must be adaptable to the nuances of concurrent neurologic deficits while also being easily implemented by a range of providers. In our pilot study(14), we found the FMSE to be readily usable and accurate when performed by bedside clinical nurses. The current validation study extends its use to APPs, suggesting that the FMSE is effective and generalizable when used by a variety of neurocritical care clinicians. Despite its intuitive design, however, users still benefit from standardized training, as interrater reliability improved substantially after training in FMSE administration and scoring. Eventually, the FMSE may facilitate future delirium research trials in neurocritical care patients, a population historically excluded from large-scale trials of ICU delirium interventions.

Our study has several limitations. Although the FMSE was designed for use across all neurocritical care patients, our validation cohort consisted of a representative sample of neurocritically ill stroke patients. It is therefore possible that our results may have differed in other patients, like those with traumatic brain injury or brain tumors. Although neurological deficits associated with such lesions are similar to those that affect stroke patients and are also compatible with FMSE assessments, future studies should test the FMSE in other populations. Furthermore, we excluded non-English-speaking patients, those with significant pre-morbid functional disability, and those with anticipated early WLST, which may limit generalizability of our results to these patients. Our study also did not distinguish between delirium subtypes, which represents a persistent gap in knowledge across both neurological and non-neurological patients. Additionally, although we previously examined the accuracy of the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU and Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist in a similar population(6), the current study lacked comparators aside from DSM-5-based assessments. As a result, we could not compare the accuracy of the FMSE with these existing delirium screening tools. Because we did not perform delirium assessments on nights, weekends, or holidays, we also may have missed some episodes of delirium, although it is unlikely that this would have substantively affected the observed accuracy of the FMSE given the overlapping timelines of reference assessments with individual FMSE assessments. Finally, although we collected data on pre-existing dementia diagnoses, we did not have detailed information on patients’ pre-morbid cognitive function, and the number of patients with dementia in our cohort was small. Given the unique challenges associated with diagnosing delirium superimposed on dementia(23), future studies should consider testing the utility of the FMSE in patients with pre-existing cognitive dysfunction, as well as those with other potentially confounding conditions.

Conclusion

In this validation study, we found the FMSE to be an accurate delirium screening tool in neurocritically ill stroke patients. FMSE scores ≥1 indicate “possible” delirium and should be used when prioritizing sensitivity, whereas scores ≥2 indicate “probable” delirium and should be used when prioritizing specificity.

Supplementary Material

KEYPOINTS.

Question:

Is the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation (FMSE) a valid and reliable delirium screening tool for neurocritically ill patients?

Findings:

In this prospective validation study, we found that the FMSE had high sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy in a representative cohort of neurocritically ill stroke patients.

Meaning:

Our study supports the use of the FMSE as an accurate delirium screening tool in neurocritically ill stroke patients. FMSE scores ≥1 indicate “possible” delirium and should be used when prioritizing sensitivity, whereas scores ≥2 indicate “probable” delirium and should be used when prioritizing specificity.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

MER is supported by the NIDUS Junior Investigator Award (NIA R24AG054259 subaward) and the Rhode Island Foundation. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to this study.

References

- 1.Salluh JIF, Wang H, Schneider EB, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. The BMJ 2015;350:h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, de Jonghe JFM, et al. Delirium in Elderly Patients and the Risk of Postdischarge Mortality, Institutionalization, and Dementia: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304(4):443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carin-Levy G, Mead GE, Nicol K, et al. Delirium in acute stroke: screening tools, incidence rates and predictors: a systematic review. J Neurol 2012;259(8):1590–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson LD, Maiga AW, Lombardo S, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Delirium After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurocrit Care 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel MB, Bednarik J, Lee P, et al. Delirium Monitoring in Neurocritically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review*. Critical Care Medicine 2018;46(11):1832–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reznik ME, Drake J, Margolis SA, et al. Deconstructing Poststroke Delirium in a Prospective Cohort of Patients With Intracerebral Hemorrhage*. Read Online: Critical Care Medicine | Society of Critical Care Medicine 2020;48(1):111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eijk MMv, Boogaard Mvd, Marum RJv, et al. Routine Use of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2011;184(3):340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenette AJ, Bebawi ER, Deslauriers LC, et al. Validation and comparison of CAM-ICU and ICDSC in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury patients. Intensive Care Medicine 2016;42(1):122–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Hofen-Hohloch J, Awissus C, Fischer MM, et al. Delirium Screening in Neurocritical Care and Stroke Unit Patients: A Pilot Study on the Influence of Neurological Deficits on CAM-ICU and ICDSC Outcome. Neurocritical Care 2020;33(3):708–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reznik ME, Margolis SA, Mahta A, et al. Impact of Delirium on Outcomes After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2022;53(2):505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintz NB, Andrews N, Pan K, et al. Prevalence of clinical electroencephalography findings in stroke patients with delirium. Clin Neurophysiol 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee JY, Colman MA, Mendu M, et al. Associations Between Stroke Localization and Delirium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2022;31(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reznik ME, Moody S, Murray K, et al. The impact of delirium on withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2020: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reznik ME, Margolis SA, Moody S, et al. A Pilot Study of the Fluctuating Mental Status Evaluation: A Novel Delirium Screening Tool for Neurocritical Care Patients. Neurocritical Care 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meagher DJ, Moran M, Raju B, et al. Phenomenology of delirium: Assessment of 100 adult cases using standardised measures. British Journal of Psychiatry 2007;190(2):135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5: Fifth edition. Arlington, VA: : American Psychiatric Association, [2013]; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reznik ME, Drake J, Margolis SA, et al. The authors reply. Critical Care Medicine 2020;48(7):e636–e637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swieten JCv, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19(5):604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldenbeuving AW, de Kort PLM, van Eck van der Sluijs JF, et al. An early prediction of delirium in the acute phase after stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2014;85(4):431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reznik ME, Schmidt JM, Mahta A, et al. Agitation After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Frequent Omen of Hospital Complications Associated with Worse Outcomes. Neurocritical Care 2016:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaBuzetta JN, Kazer MR, Kamdar BB, et al. Neurocheck Frequency: Determining Perceptions and Barriers to Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice. The Neurologist 9900: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morandi A, Davis D, Bellelli G, et al. The Diagnosis of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia: An Emerging Challenge. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2017;18(1):12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.